Abstract

The somatic activating janus kinase 2 mutation (JAK2)V617F is detectable in most patients with polycythemia vera (PV). Here we report that CP-690,550 exerts greater antiproliferative and pro-apoptotic activity against cells harboring JAK2V617F compared with JAK2WT. CP-690,550 treatment of murine factor-dependent cell Patersen–erythropoietin receptor (FDCP-EpoR) cells harboring human wild-type or V617F JAK2 resulted in inhibition of cell proliferation with a 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 2.1 µM and 0.25 µM, respectively. Moreover, CP-690,550 induced a significant pro-apoptotic effect on murine FDCP-EpoR cells carrying JAK2V617F, whereas a lesser effect was observed for cells carrying wild-type JAK2. This activity was coupled with inhibition of phosphorylation of the key JAK2V617F-dependent downstream signaling effectors signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)3, STAT5, and v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog (AKT). Furthermore, CP-690,550 treatment of ex-vivo-expanded erythroid progenitors from JAK2V617F-positive PV patients resulted in specific, antiproliferative (IC50 = 0.2 µM) and pro-apoptotic activity. In contrast, expanded progenitors from healthy controls were less sensitive to CP-690,550 in proliferation (IC50 > 1.0 µM), and apoptosis assays. The antiproliferative effect on expanded patient progenitors was paralleled by a decrease in JAK2V617F mutant allele frequency, particularly in a patient homozygous for JAK2V617F. Flow cytometric analysis of expanded PV progenitor cells treated with CP-690,550 suggests a possible transition towards a pattern of erythroid differentiation resembling expanded cells from normal healthy controls.

The myeloproliferative disorders (MPD) polycythemia vera (PV), essential thrombocythemia (ET), and primary myelofibrosis (PMF), constitute a group of heterogeneous diseases arising from the clonal transformation of a hematopoietic stem cell.(1,2) Clinically, MPD are characterized by proliferation of one or more myeloid cell lineages in bone marrow and peripheral blood, with relatively preserved differentiation. The dominant gain-of-function mutation in the tyrosine kinase janus kinase 2 (JAK2) (1849 G to T) has been detected in greater than 80% of PV patients and in approximately half of ET and PMF patients.(3–7) The mutation results in a non-synonymous amino acid substitution at position 617 (valine to phenylalanine), and is located in the JH2 pseudokinase auto-inhibitory domain. This mutation represents the first acquired somatic mutation in hematopoietic stem cells described in these disorders.

Constitutively active tyrosine kinases are disengaged from normal regulatory mechanisms and result in deregulated activation of downstream signal-transduction pathways. When mutant JAK2V617F enzyme is expressed in patient hematopoietic stem cells, several signaling pathways important for proliferation and survival are activated. Experimental evidence indicates that JAK2V617F causes erythrocytosis in patients with PV. Murine models, in which JAK2V617F is retrovirally overexpressed, display a phenotype that closely resembles PV, including progression to myelofibrosis, when high levels of JAK2V617F are expressed. Furthermore, JAK2V617F allele frequency, or ‘mutational burden’, has been reported to correlate with white blood cell count, hemoglobin levels in PV, and some complications of MPD, such as the degree of marrow fibrosis or thrombotic tendencies.(8)

Following discovery of the JAK2V617F mutation in 2005, an increasing number of novel JAK2 mutations, associated with hematological malignancies, have been reported.(9–16) Analogous to the V617F, many of these mutations are located within the JH2 pseudokinase auto-inhibitory domain, indicating similarity in the mechanisms leading to JAK2 deregulation.(9–12,14,16) Although most mutations described have been in the JH2 domain, the JAK2T875N mutation affects the JH1 kinase domain, also resulting in constitutive enzyme activity.(13) In addition, a recent report by Scott and coworkers described four novel mutations, JAK2F537-K539delinsL, JAK2H538QK53L JAK2K539L, and JAK2N542-E543deL in 10 JAK2V617F-negative MPD patients.(15) To date, no effective inhibitors of the JAK–signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) signaling pathway are currently available for use in the clinic. Hence, the recurrent identification of novel activating mutations in JAK2, and their association with hematological malignancies, point out the urgent need for development of potent JAK2 inhibitors with therapeutic potential.

Mutations in protein tyrosine kinases have a significant role in oncogenic transformation and thus have become an attractive chemotherapeutic target. This is best illustrated by the efficacy in treating chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) with imatinib mesylate (STI571, Gleevec),(17) a potent inhibitor of the fusion protein tyrosine kinase Bcr-Abl (which is associated with Philadelphia chromosome), and a selective inhibitor of platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR), cKit and Arg protein tyrosine kinases.(18) Mutations in the JAK3 gene lead to severe impairement of both cellular and humoral immunity.(19) Hence, inhibitors of the JAK–STAT signal transduction pathway may be used as potent immunosuppressants for transplantation therapy. CP-690,550, a selective inhibitor of the JAK–STAT cascade, was developed based on the hypothesis described above. Experimental evidence for its effectiveness as an immunosuppressant has been reported.(19) Results indicate that CP-690,550, a selective JAK3 inhibitor, allowed significant prolongation of graft survival in allotransplantation models in rodents and non-human primates. Furthermore, enzymatic assays indicate that both JAK1 and JAK2 are 100- and 20-fold less sensitive to inhibition by CP-690,550, respectively, when compared with JAK3. Nevertheless, at a 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 20 nM for JAK2, CP-690,550 still represents a potent JAK inhibitor worth investigating for treatment of oncogenic transformation due to mutations in JAK2 genes.

In the present study, we report that CP-690,550(19) treatment of murine factor-dependent cell Patersen–erythropoietin receptor (FDCP-EpoR) cells, retrovirally transduced with human JAK2WT or JAK2V617F, results in greater antiproliferative and pro-apoptotic effects on cells bearing mutant JAK2. More importantly, similar antiproliferative and pro-apoptotic activity was observed when ex-vivo-expanded erythroid bone marrow progenitors from JAK2V617F-positive PV patients were treated with CP-690,550. These effects coincided with strong inhibition of JAK2-dependent downstream signaling events, and significant reduction in JAK2V617F frequency in ex-vivo-expanded patient samples.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and chemicals

Mouse FDCP-EpoR cells transduced with retroviral vectors carrying human JAK2WT or JAK2V617F were maintained as previously described.(5) Briefly, both cell lines were cultured at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere using Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium (RPMI) 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), and 5% WEHI conditioned media (WEHI-CM), unless otherwise specified. Human erythroleukemic cell line (HEL) was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, USA) and maintained in Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium (IMDM; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), supplemented with 10% horse serum (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). CP-690,550 was a gift from Exelexis Inc. (So. San Francisco, CA, USA), and was stored as a 10 mM stock solution in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at −20°C. Antibodies used for immunoblotting were as follows: rabbit antibody specific for JAK2 (06-255), JAK3 (04-011), mouse antiphospho-STAT3 (05-485) and phospho-STAT5 (05-495), antiphosphotyrosine clone-4G10 (05-321), rabbit anti-STAT3 (06-596) and STAT5 (06-553) were from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY, USA); antiphospho-v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog (AKT) (550747), and anti-AKT (610876), antibodies were purchased from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA, USA); monoclonal mouse anti-poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) antibody (4338-MC-50) was obtained from Trevigen Inc. (Gaitherburg, MD, USA); anti-X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) rabbit monoclonal antibody (2042) was obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA); monoclonal anticaspase-3 (60-6663, active and proactive) antibody was purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA, USA); and mouse anti-β-actin antibody was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (A5441, St. Louis MO, USA). Agarose conjugated protein A/G was from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies (SC-2003, Santa Cruz, CA, USA).

Cell lysates and Western blot analysis

Cellular lysates were prepared according to antigen, being screened as previously described.(20) Protein was estimated using the Bradford reagent (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Standard procedures were used for 10% denaturing sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western blot analysis.

FDCP-EpoR growth inhibition assay

Determination of growth inhibition by CP-690,550 was performed using identical culture conditions for both FDCP-EpoR JAK2WT and JAK2V617F cell lines. Briefly, 1 × 105 cells/mL were cultured in 96-well flat-bottom plates at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere using RPMI 1640 supplemented with 1.25% FCS, and 5% WEHI supernatant. Decreased FCS concentration was necessary to prevent binding between drug and serum proteins as per the manufacturer’s recommendation. Growth inhibition assays were terminated by addition of 20 µL CellTiter96 One Solution Reagent (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Flat-bottom plates were incubated for an additional 3 h for color development. Absorbance was determined at 595 nm on a BioTek Synergy-HT microplate reader (Bio-Tek, Winooski, VT, USA). Results are the average ± standard deviation of three independent determinations.

Immunoprecipitation of JAK2, JAK3 and Western blotting

HEL cells, expanded erythroid progenitor cells from normal donor, two PV patients,(21,22) and FDCP-EpoR reporter cells (2 × 107 cells per sample), which were treated with increasing concentrations of CP-690,550, were harvested at different time points. Cells were pelleted, washed three times with cold phosphate buffer saline, resuspended in 300 µL lysis buffer (10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.2, containing 100 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% deoxycholate, 5 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid [EDTA], 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 × Roche complete Mini protease inhibitor cocktail [Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA], 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF], and 1 mM 4-(2-aminoethyl) benzenesulfonyl fluoride hydrochloride [AEBSF]) and incubated on ice for 1 h. Cell lysates were centrifuged 20 000g for 20 min at 4°C, and the clear supernatant decanted. Fifteen µL of anti-JAK2 (treated cells) or anti-JAK3 rabbit antibody (untreated cells) was added to the supernatants followed by an additional 1 h incubation on ice. Finally, 50 µL of protein A/G agarose slurry was added to the supernatants and incubated overnight at 4°C with constant rotation. The antibody–protein complex was washed three times, once with radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (100 mM NaCl in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.2 containing 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.05% SDS, 5 mM EDTA, and a cocktail of protease inhibitors), once with washing buffer (100 mM NaCl in 10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.2, and 0.1% Triton X-100), and finally, once with 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer pH 7.5. The immunoprecipitated complex was analyzed by Western blotting using first the antiphospho-tyrosine antibody followed by stripping, and reprobing using the anti-JAK2 and anti-JAK3 antibody.

Apoptosis assay

Apoptotic cells were detected by flow cytometry using recombinant human Annexin-V conjugated with allophycocyanin (APC, CALTAG, Burlingame, CA). Briefly, after exposure to CP-690,550 for different periods of time, cells were washed in Ca2+-free PBS and resuspended in 100 µL of binding buffer (10 mM HEPES pH 7.4; 0.15 M NaC1; 5 mM KCl; 1 mM MgCl2; 1.8 mM CaCl2) to which Annexin-V-APC had been previously added. Cells were incubated for 20 min in the dark at room temperature, washed and resuspended in 0.3 mL binding buffer. Cells were analyzed on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer equipped with the Cell Quest Pro software (Becton Dickinson Systems, San Jose, CA, USA).

Cell cycle analysis by flow cytometry

Following treatment with CP-690,550, cells were collected, washed in Ca2+-free PBS and fixed overnight in 70% cold ethanol at −20°C. The cells were subsequently washed twice in cold PBS, and labeled with propidium iodide (PI) overnight at 4°C. Percentage of cells in sub-G1 phase was determined on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer, and analyzed using ModFit LT v3.1 (Becton-Dickinson Systems, San Jose, CA, USA).

Measurement of mitochondrial transmembrane potential

After treatment with CP-690,550, cells were incubated with submicromolar concentrations of the MitoTracker Red probe (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) to evaluate changes in mitochondrial membrane potential. Briefly, harvested cells were washed in Ca2+-free PBS and stained with MitoTracker Red for 1 h at 37°C in the dark. Samples were analyzed on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer using the Cell Quest Pro software (Becton-Dickinson Systems, San Jose, CA, USA).

Erythropoietin induction of CP-690,550 treated cells

FDCP-EpoR cells were prestarved in serum-free medium (RPMI 1640) for 20 h. Starved cells were subsequently treated with CP-690,550 at either 0, 0.1, or 1 µM for 40 min, followed by incubation for another 40 min in the absence, or presence, of 10 U/mL erythropoietin (Epo). Following treatment, cells were harvested by centrifugation. Intracellular localization of STAT3 was performed in paired samples by Western blot analysis of cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts, and by epifluorescent confocal microscopy.

Preparation of cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts

Serum-starved FDCP-EpoR cells, as described above, were harvested and both cytoplasmic and nuclear protein extracts were made using NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagent following manufacturer’s recommendations (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, IL, USA). Extracts were analyzed for phospho (p)-STAT3 and STAT3 by Western blot.

Immunolocalization of STAT3

Starved FDCP-EpoR cells, as described above, were washed twice with PBS and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min. Fixed cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min, washed and preincubated in blocking solution (5% normal goat serum in PBS) for 30 min at room temperature. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation, resuspended in fresh blocking solution containing rabbit anti-STAT3 antibody, and incubated with gentle shaking for 3 h at room temperature. Cells were further incubated in the presence of an AlexaFluor-595-labeled secondary donkey anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody (A21207; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. Three 10-min washes with 5% normal goat serum in PBS were performed between antibody incubations. Cells were mounted onto slides with Pro-Long Gold antifade reagent containing 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (P36935; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) mounting medium. Cells were visualized with a 40×/0.9 objective lens mounted on an Olympus BX60 epifluorescence microscope (Olympus, Melville, NY, USA), and the images were recorded with an Optronics CCD camera and Fluoview software version 4.3 (Olympus, Center Valley, PA, USA).

In vitro expansion of erythroid progenitors

Samples from bone marrow (PV patients) and peripheral blood (PV patients and normal healthy controls) were obtained after signed consent using an Institutional-Review-Board-approved protocol. Mononuclear cells were separated by Histopaque (density 1.077) gradient centrifugation and used for expansion of erythroid progenitor cells based on modifications of a published protocol.(21,22) Briefly, progenitor cells are expanded, and differentiated, in Stem Span Serum-Free Expansion Medium (SFEM; Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada) over a 2-week, two-step period, which makes use of specific cytokine combinations. In the first step (days 0–7), bone marrow mononuclear cells are cultured in the presence of a cytokine cocktail (CC110) consisting of FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3; 50 ng/mL), thrombopoietin (100 ng/mL), and stem cell factor (100 ng/mL) (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada). Cytokines used during the second step (days 8–14) are: stem cell factor (50 ng/mL) (R and D systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), insulin-like growth factor-1 (50 ng/mL) (R and D systems), and Epo (3 U/mL) (Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA, USA). On day 12, expanding progenitor cells were harvested, counted using a hemocytometer, re-plated at a density of 4 × 105/mL using fresh step 2 media in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of CP690,550, and incubated for an additional 2 days (day 14) at 37°C in a 5% CO2 water-saturated atmosphere.

Flow cytometric analysis of expanded progenitor cells

Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-human-CD71 (transferrin receptor) and allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated anti-CD235A (glycophorin-A) monoclonal antibodies were from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA). At the end of week 2, expanded progenitor cells were harvested and stained for flow cytometric analysis with CD71-FITC, CD235A-APC, and PI (added immediately before analysis). Cells were analyzed on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer equipped with the Cell Quest Pro software (Becton-Dickinson Systems, San Jose, CA, USA). PI-negative events (live cells) were gated and further examined for CD71 × CD235A positivity. Frequency of events showing both high CD71 and CD235A surface expression were estimated. Co-expression of CD71 and CD235A is indicative of erythroid progenitor proliferation and differentiation. Further analysis and figures were made using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR, USA).

Quantitation of the JAK2V617F mutant T-allele

Expanded bone marrow or peripheral blood mononuclear cells from three patients with PV treated with varying concentrations of CP-690,550 were harvested and stained with CD71-FITC, CD235A-APC, and PI as described above. Flow-cytometry-assisted cell sorting was performed on a FACSAria (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) equipped with the Cell Quest Pro software (Becton-Dickinson Systems, San Jose, CA, USA). PI-negative events (live cells) were gated, examined for CD71 × CD235A positivity, and live cells sorted for quantitation of JAK2V617F allele. Genomic DNA (gDNA) from each individual sample was extracted using the Puregene DNA purification kit (Gentra, Minneapolis, MN, USA) and 1/10th aliquot was used for PCR amplification with primers: JAK2-Exon14-F (GGACCAAAGCACATTGTATCCTC) and JAK2-Exon14-R (GGGCATTGTAACCTTCTACTT). The resulting 400 bp JAK2 PCR product was purified using the Qiagen PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Quantitative allele-specific suppressive PCR (ASS-PCR) was performed using the purified PCR product on a sequence detection system 7000 platform (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) as previously described.(23)

Results

CP-690,550 preferentially inhibits proliferation of murine cells transduced with JAK2V617F

The effect of CP-690,550 on the viability of FDCP-EpoR cells transduced with wild-type or mutant human JAK2 was investigated using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. Exposure to increasing concentrations of CP-690,550 resulted in a dose-dependent inhibition of cellular proliferation in both cell lines (Fig. 1a). However, JAK2V617F-bearing cells were almost 10-fold more sensitive to CP-690,550 compared with JAK2WT cells, with IC50s of 0.25 µM and 2.11 µM, respectively (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

(a) CP-690,550 selectively inhibits proliferation of factor-dependent cell Patersen–erythropoietin receptor (FDCP-EpoR) cells harboring mutant janus kinase 2 (JAK2)V617F. Both JAK2WT- and JAK2V617F-transduced FDCP-EpoR cells were treated with increasing concentrations of CP-690,550 for 72 h. The 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay was used to evaluate cell proliferation. Data points are the mean ± SD from three independent determinations. (b) A non-linear regression model of the MTT results was used to estimate the CP-690,550 inhibitory concentration (IC) values for both cell lines (inset).

JAK3 is not phosphorylated in FDCP-EpoR cells transduced with JAK2WT or JAK2V617F

CP-690,550 was originally reported to be a JAK3-specific inhibitor(19) and targeted at patients undergoing organ transplantation. Therefore, in the present study, we examined the activation of p-JAK3 in untreated HEL cells, FDCP-EpoR cells, expanded progenitor cells from normal controls and PV patients (Fig. 2a). We observed activation and phosphorylation of JAK3, by Western blot analysis, solely in the HEL cell line. Phosphorylation of JAK3 was not detected in either FDCP-Epo reporter cells or expanded progenitor cells from normal control and PV patients.

Fig. 2.

Janus kinase 3 (JAK3) is not phosphorylated and CP-690,550 inhibits phosphorylation of JAK2, signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)3, STAT5, v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog (AKT), and decreases X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) levels. (a) Untreated human erythroleukemic cell line (HEL) cells, factor-dependent cell Patersen–erythropoietin receptor (FDCP-EpoR) cells, expanded progenitor cells from normal control and two polycythemia vera (PV patients were immunoprecipitated with rabbit anti-JAK3 and Western blotting was performed as described above. (b) FDCP-EpoR cell lines carrying either wild-type or mutant human JAK2 were treated with equipotent inhibitory concentration (IC) doses (20, 40, 50, and 80) of CP-690,550 for 3 h. Following treatment, cell lysis and Western blot analysis were performed as described in materials and methods. Resulting phospho- and total proteins, as well as XIAP were detected as described in materials and methods. β-actin served as loading control. (c) JAK2V617F-transduced FDCP-EpoR cells were exposed to two different doses (50% inhibitory concentration [IC50] and IC80) of CP-690,550 for 24 and 48 h. Whole-cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting for total- and phospho-STAT3, and STAT5. β-actin served as loading control.

CP-690,550 inhibits signaling through the JAK2–STAT3 axis in murine cells transduced with JAK2V617F

The effect of CP-690,550 on JAK2 phosphorylation was investigated by treating FDCP-EpoR cells carrying either wild-type or mutant human JAK2 with increasing equipotent doses of CP-690,550 for 3 h, determined by non-linear regression of the MTT results (Fig. 1b). CP-690,550 dose-dependent inhibition of JAK2 phosphorylation on mutant-bearing mouse cells was observed (Fig. 2b). In contrast, independent of treatment, p-JAK2 was undetectable in murine cells harboring human JAK2WT, further emphasizing the constitutively active status of mutant JAK2V617F (Fig. 2b). However, total JAK2 remained unchanged in both cell lines, indicating that the decrease in JAK2 phosphorylation was not due to protein turnover (Fig. 2b). In vitro expression of JAK2V617F results in constitutive activation of the STAT3/5 and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways, which are important for cellular proliferation and survival.(5,24) As CP-690,550 inhibited JAK2 phosphorylation, we reasoned that JAK2-mediated phosphorylation of the downstream signaling effectors, STAT3 and STAT5 may also be affected. Dose- and time-dependent inhibition of STAT3 and STAT5 phosphorylation by CP-690,550 on mutant-bearing cells was observed (Fig. 2b,c). In contrast, in murine cells harboring human JAK2WT, although p-STAT3 was undetectable independent of treatment, a decrease in STAT5 phosphorylation with increasing doses of the drug was noted (Fig. 2b). These observations led us to conclude that constitutively active human JAK2V617F preferentially targets murine STAT3 for phosphorylation in the FDCP-EpoR cell line. Furthermore, the intensity of the p-STAT5 signal, by Western blot, was similar for both JAK2 wild-type and mutant bearing mouse cell lines, with signal decreases of the same magnitude in response to equipotent doses of CP-690,550 (Fig. 2b). Our results, however, do not exclude a role for human JAK2V617F-mediated phosphorylation of mouse STAT5, though not of same magnitude observed for mouse STAT3. Following the JAK2–STAT3 pathway, we also observed inhibition of AKT phosphorylation by CP-690,550 coupled to decreased levels of the XIAP (Fig. 2b).(25) Comparison of the basal levels of p-AKT between both mouse cell lines indicates decreased levels in JAK2V617F bearing cells. However, reduced levels of total AKT are also noted in FDCP cells harboring mutant JAK2 (Fig. 2b). Hence, this discrepancy in p-AKT levels is balanced, and therefore not considered significant. Finally, as a whole, we hypothesize that the antiproliferative activity of CP-690,550 on the mouse cells harboring human JAK2WT is due to inhibition of a distinct endogenous tyrosine kinase, possibly involving the dependency of these cells on interleukin-3 (IL3) signaling.

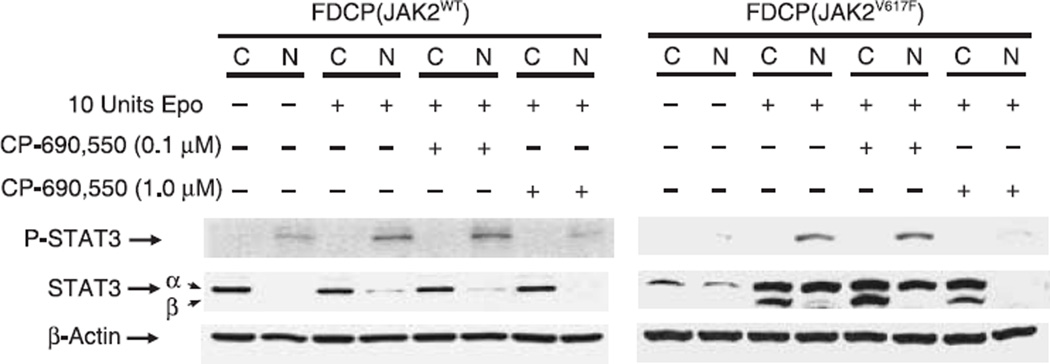

CP-690,550 inhibits nuclear translocation of STAT3

As our results indicate STAT3 is preferentially targeted for phosphorylation by mutant JAK2, we decided to focus our attention on this pathway. Furthermore, given that nuclear translocation is required for p-STAT3 function, we investigated whether CP-690,550 growth inhibition of FDCP-EpoR cells, transduced with JAK2WT or JAK2V617F, hindered this translocation. Nuclear translocation of p-STAT3 was observed in both JAK2WT and JAK2V617F FDCP-EpoR human JAK2-starved cell lines upon Epo stimulation (Fig. 3). However, in the absence of Epo, we only observe STAT3 nuclear localization in FDCP-EpoR JAK2V617F cells (Fig. 3), most likely as a result of the constitutively active mutant JAK2, and in agreement with p-STAT3 results (Fig. 2b). Although p-STAT3 could be easily detected in murine cells harboring mutant JAK2, visualization in cells harboring wild-type human enzyme required prolonged auto-radiographic exposure resulting in increased background (Fig. 3). When serum-starved cells were pretreated with 0.1 µM CP-690,550 almost no change in nuclear p-STAT3, after Epo induction, was observed (Fig. 3). However, if these cells were pretreated with 1 µM CP-690,550 instead, a significant reduction in both p-STAT3 and STAT3 in nuclear extracts after Epo induction was noted (Fig. 3). Taken together, these results indicate abrogation of Epo-stimulated nuclear translocation of p-STAT3 in CP-690,550-pretreated cells.

Fig. 3.

CP-690,550 inhibits signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)3 nuclear localization in both murine cell lines. Twenty hour serum-starved factor-dependent cell Patersen–erythropoietin receptor (FDCP-EpoR) cell lines were treated, or not, with 0.1 µM or 1 µM of CP-690,550 for 40 min. Treatment was followed by an additional 40 min incubation in the absence or presence of erythropoietin (Epo; 10 U/mL). Cytoplasmic and nuclear protein extracts, from treated cells, were analyzed by Western blotting for total- and phospho- STAT3, as described in materials and methods. β-actin served as loading control.

Immunolocalization of STAT3

Further evidence supporting inhibition of STAT3 nuclear translocation by CP-690,550 was obtained by confocal microscopy. FDCP-EpoR cells carrying either human JAK2WT or JAK2V617F were serum starved, treated with CP-690,550 and Epo, and used for STAT3 immunolocalization, as described in Materials and methods. A weak STAT3 fluorescent signal was visible in the nucleus of serum-starved control cells carrying either JAK2WT (Fig. 4a–c) or JAK2V617F (Fig. 4j–l). Epo stimulation produced a significant increase in STAT3 immunofluorescence for both cell lines. Moreover, results indicate increased STAT3 nuclear localization in both JAK2WT (Fig. 4d–f) and JAK2V617F (Fig. 4m–o) cell lines in the presence of Epo. In contrast, STAT3 immunofluorescence preferentially localized to the peri-nuclear region in both JAK2WT (Fig. 4g–i) or JAK2V617F (Fig. 4p–r) cell lines when exposed to 1 µM CP-690,550. Taken together, results obtained using both confocal microscopy and Western blot analysis of cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts support a model in which CP-690,550 inhibits STAT3 nuclear translocation.

Fig. 4.

CP-690,550 modulates immunolocalization of signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)3. Both janus kinase (JAK)2WT and JAK2V617F murine factor-dependent cell Patersen–erythropoietin receptor (FDCP-EpoR) cell lines were treated as described in Fig. 3. Following treatment, cells from both cell lines were harvested, fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde, and stained using rabbit anti-STAT3 antibodies. Rabbit anti-STAT3 antigen/antibody complexes were visualized via a secondary donkey anti-rabbit conjugated with AlexaFluor-595. STAT3 localized mostly to the nucleus or peri-nuclear region in both JAK2WT (a–i) and JAK2V617F (j–r) cell lines. A dim fluorescent signal was visible in starved controls (a–c, j–l); however, a significant increase in signal intensity was observed after erythropoietin (Epo) stimulation (d–f, m–o). In contrast, peri-nuclear localization of STAT3 was observed when cells were treated with CP-690,550 and Epo (g–i, p–r). Each triplet panel represents nuclear staining with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; top left), STAT3 immunofluorescence (top right), and the overlay of both recorded fluorescence images (bottom). Cells were visualized with a 40× objective lens and 10× ocular lenses on an Olympus BX60 epifluorescent microscope. Images were recorded with an Optronics CCD-camera.

CP-690,550 induces apoptosis of JAK2V617F-transduced FDCP-EpoR cells

To clarify whether the CP-690,550-mediated growth inhibition of FCDP-EpoR JAK2V617F cells was due to drug-induced apoptosis, we performed a series of experiments using equipotent doses of this compound. An increase in the fraction of apoptotic cells was observed in the cell line carrying mutant human JAK2 in a time- and dose-dependent manner (Table 1A). In contrast, we observed an increase in the fraction of apoptotic mouse cells harboring wild-type human JAK2 only at the highest concentration of drug tested (Table 1 A). Furthermore, the effect of CP-690,550 on induction of apoptosis (Table 1A) and mitochondrial membrane potential damage (Table 1B) was greater for mouse cells transduced with the mutant human JAK2 compared with wild type. Collectively, these observations indicate that growth inhibition by CP-690,550 may be explained by induction of the apoptotic pathway through inhibition of the JAK2–STAT3 pathway. Further confirmation of these observations was obtained by Western blot analysis. Proteolytic activation of caspase 3 and PARP was observed as early as 24 h after treating FCDP-EpoR JAK2V617F cells with increasing concentrations of CP-690,550 (Fig. 5).

Table 1.

Induction of apoptosis (A) and mitochondrial potential damage (B) by CP-690,550 at equipotent doses (50% inhibitory concentration [IC50] and IC80) in factor-dependent cell Patersen–erythropoietin receptor (FDCP-EpoR) cell lines transduced with either janus kinase 2 (JAK2)WT or JAK2V617F

| FDCP (JAK2WT) | FDCP (JAK2V617F) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2.11 µM | 4.83 µM | 0 | 0.25 µM | 0.85 µM | ||

| A. Apoptosis (% Annexin V positive) | 48 h | 11.21 (± 2.1) | 11.75 (± 2.9) | 35.78 (± 6.8) | 11.75 (± 1.5) | 35.64 (± 13.23) | 51.19 (± 4.7) |

| 72 h | 19.37 (± 1.5) | 18.97 (± 4.9) | 47.36 (± 10.4) | 18.97 (± 6.1) | 41.77 (± 3.3) | 79.51 (± 9.3) | |

| B. Mitochondrial membrane potential (% CMX negative) | 48 h | 8.97 (± 2.1) | 6.11 (± 4.3) | 23.89 (± 5.6) | 6.19 (± 3.7) | 15.32 (± 5.8) | 22.67 (± 4.2) |

| 72 h | 10.42 (± 3.6) | 6.78 (± 3.7) | 37.78 (± 3.9) | 7.68 (± 5.8) | 39.66 (± 8.2) | 56.88 (± 7.2) | |

CMX, mito tracer red.

Fig. 5.

CP-690,550-induced poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) and caspase-3 cleavage. Janus kinase 2 (JAK2)V617F-transduced factor-dependent cell Patersen–erythropoietin receptor (FDCP-EpoR) cells were exposed to two different doses (20% inhibitory concentration [IC20] and IC80) of CP-690,550 for 24 and 48 h. Cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting using mouse monoclonal anti-PARP, and anticaspase-3. β-actin served as loading control.

Effect of CP-690,550 on in-vitro-expanded human erythroid progenitor cells

Mononuclear cells from healthy controls and PV patients, with JAK2V617F mutant allele frequencies ranging from 20 to 80%, were used for in vitro expansion and differentiation, of erythroid progenitors as described in Materials and methods. Growth inhibition of day-12 expanding progenitor cells from healthy controls and PV patients exposed to increasing concentrations of CP-690,550 for 48 h was assessed by MTT assay (Fig. 6a). Significant antiproliferative activity, with an IC50 estimated at 0.2 µM for PV patient progenitor cells, independent of JAK2V617F allele frequency, was observed (Fig. 6a). In contrast, antiproliferative activity of CP-690,550 on cells from healthy controls resulted, at best, in an IC25 of 1 µM (Fig. 6a). This is in agreement with our experimental results obtained using FDCP-EpoR cells transduced with human wild-type or mutant JAK2. In addition, exposure of expanded progenitors from PV patients to 0.1 µM and 1 µM CP-690,550 for 48 h caused an increase in apoptotic cells of 50% and 80%, respectively (Fig. 6b). In contrast, little or no change was observed in samples from healthy controls (Fig. 6b). Erythroid progenitor cell lysates from two healthy controls and two PV patients treated, or not, with 1 µM CP-690,550 were analyzed for changes in P-JAK2 and P-STAT5 levels (Fig. 6c). Western blot analysis indicates increased levels of p-STAT5 in samples from JAK2V617F-positive PV patients compared with those from healthy controls (Fig. 6c). Treatment with CP-690,550 resulted in reduction of p-STAT5 levels in samples from patients, but those from healthy controls remained unchanged. Moreover, total STAT5 protein remained unchanged in drug-treated samples from both healthy controls and PV patients (Fig. 6c), indicating CP-690,550 causes STAT5 dephosphorylation without affecting expression or protein turnover. Therefore, contrary to our previous observations with transduced murine cell lines, our results in PV patient samples indicate CP-690,550 exerts its selective antiproliferative activity by inhibiting the JAK2–STAT5 pathway. Changes in JAK2 mutant allele frequency were investigated after 48 h treatment of ex-vivo-expanded PV erythroid progenitor cells with CP-690,550 (Fig. 6d). A decrease in JAK2 mutant allele frequency in flow-cytometry-sorted, surviving erythroid progenitor cells from three patient samples was noted, albeit a significantly greater effect was observed in the homozygous patient (Fig. 6d).

Fig. 6.

Effect of CP-690,550 on ex vivo expanded erythroid progenitors. (a) In-vitro-expanded erythroid progenitor cells from healthy controls and polycythemia vera (PV) patients were treated with increasing concentrations of CP-690,550 for 48 h. The 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay was used to evaluate cell proliferation. Curves represent data from representative experiments performed in triplicate. (b) Both, healthy controls and PV patient expanded erythroid progenitors were exposed to 0, 0.1 and 1.0 µM CP-690,550 for 48 h. Post-treatment, cells were harvested, stained with Annexin V– allophycocyanin (APC) and the percentage of apoptotic cells determined by flow cytometry. (c) Expanded erythroid progenitors from two healthy controls (HC1, HC2) and two patients with PV (PV4, PV5) were treated with CP-690,550 1 µM for 72 h. Total protein was extracted and subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and immunoblotting. Membranes were stained using phosphor-janus kinase (JAK)2, JAK2, phospho-STAT5, STAT5, and β-actin monoclonal antibodies. (d) In-vitro-expanded erythroid progenitors from two heterozygous (G/T) and one homozygous (T/T) mutant JAK2V617F-positive PV patients were exposed to three different doses of CP-690,550. Treated cells were harvested, after 48 h, and stained with CD71-FITC, CD235A-APC, and propidium iodide (PI). Flow cytometric sorting of live cells (PI negative) was performed, genomic DNA extracted, and JAK2V617F mutant allele frequency determined as described in materials and methods.

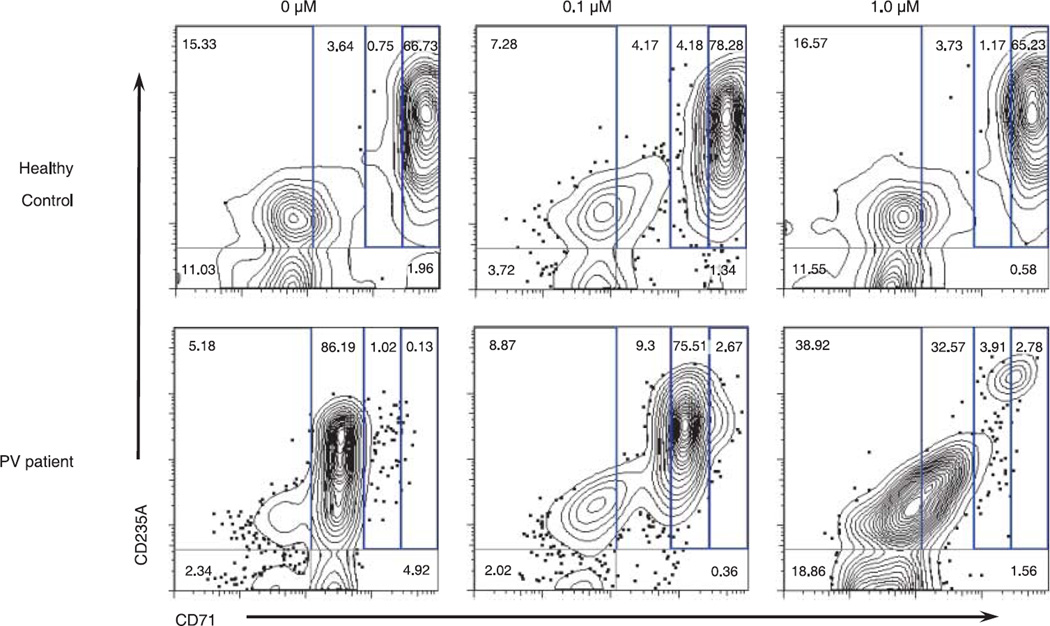

Flow cytometric analysis of differentiating ex-vivo-expanded erythroid progenitors from healthy controls or PV patients cultured with 0, 0.1, and 1.0 µM CP-690-550 was assessed using the erythroid maturation markers CD71 × CD235A (Fig. 7). Results indicate that exposure of patient cells to the drug causes a dose-dependent shift in the pattern of differentiating cells, which resembles the pattern observed for cells from healthy controls (Fig. 7). Moreover, analysis by flow cytometry indicates CP-690,550 has a specific effect on expansion and differentiation of PV-patient erythroid progenitors, whereas modest changes are noted in control samples (Fig. 7). These results are in agreement and strongly support our observations made in the preceding experiments.

Fig. 7.

Flow cytometry of CP-690,550 treated in-vitro-expanded erythroid progenitors from healthy control and polycythemia vera (PV) patient. Ex-vivo-expanded progenitor cells from healthy controls or PV patients were cultured for 48 h in the absence, or presence, of two different doses of CP-690-550 (0.1 and 1.0 µM). Immediately following treatment, cells were stained for flow cytometric analysis with CD71-FITC, CD235A-APC, and PI (immediately before analysis). PI-negative events (live cells) were gated and examined for CD71 × CD235A positivity. Frequency of events showing both high CD71 and CD235A was estimated, and is indicative of erythroid progenitor proliferation and differentiation. Primitive progenitor cells plus mature BFU-Es and CFU-Es are characterized by CD71med, CD235Alow; proerythroblasts and early basophilic erythroblasts are CD71high, CD235Alow; early and late basophilic erythroblasts are CD71high, CD235Ahigh; polychromatophilic and orthochromatophilic erythroblasts are CD71med, CD235Ahigh; and, late orthochromatophilic erythroblasts and reticulocytes are CD71low, CD235Ahigh.

Discussion

JAK2 kinase plays a significant role in hematopoiesis. Knockout of JAK2 in transgenic mice results in embryonic lethality at day 12.5 owing to failure of erythropoiesis. Moreover, constitutively active tyrosine kinases have been found frequently associated with pathogenetic events in hematopoietic malignancies (e.g. TEL-JAK2, FIP1-PDGFR, cKit, BCR-ABL).(26) JAK2 tyrosine kinase, which is normally bound to the cytosolic domain of a type I cytokine receptor, becomes activated by transphosphorylation of a tyrosine residue in the activation loop after cytokine stimulation.(27–29) In contrast, constitutively active JAK2V617F, which remains bound to the cytosolic domain of receptor, no longer requires cytokine stimulation for transphosphorylation and activation.(30) Downstream JAK2 effectors, like STAT5, are now continuously signaling proliferation, survival, and differentiation pathways.(6) Suppression of deregulated signaling pathways as a therapeutic strategy has been investigated, e.g. successful use of imatinib-targeted BCR-ABL inhibition for treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia.(31) Therefore, owing to the recurrent findings of JAK2-associated mutations in hematopoietic malignancies, specific inhibitors are being actively sought for their potential therapeutic application.

In the present study, we show that CP-690,550 exerts potent antiproliferative and pro-apoptotic activity against cells expressing the JAK2V617F mutation. CP-690,550 treatment resulted in inhibition of proliferation of JAK2V617F-transfected FDCP-EpoR cells with an IC50 of 0.25 µM (Fig. 1a and b). More importantly, an approximate 10-fold difference in susceptibility to CP-690,550 growth inhibition (IC50 2.11 µM) was observed for murine cells carrying wild-type human JAK2 (Fig. 1a and b). In contrast, the tyrphostin AG490, a JAK2 kinase inhibitor, was reported to exert in vitro inhibitory activity at an IC50 greater than 50 µM, which prevented further clinical development of this compound.(32–35) Nevertheless, AG490 has been recently reported to inhibit Epo-independent erythroid colony formation in methylcellulose assays using JAK2V617F-positive hematopoietic progenitors from PV patients.(36)

Our results indicate that the antiproliferative activity of CP-690,550 was coupled with inhibition of phosphorylation of key JAK2 downstream effectors STAT3/5, and AKT. Owing to the constitutively active mutant JAK2V617F, CP-690,550 growth inhibition was more pronounced in mutant-bearing cells compared with those harboring JAK2WT. Moreover, CP-690,550-mediated dephosphorylation of the survival pathway effector AKT was coupled with activation of the apoptotic pathway. AKT is known to interact with, and phosphorylate, the intracellular antiapoptotic protein XIAP.(25) Overexpression of antiapoptotic proteins, such as XIAP or baculoviral IAP repeat-containing 5 (survivin), has been reported in cancer cell lines and primary tumors, indicating that it must play a significant role in disease progression. Phosphorylation of XIAP by AKT prevents ubiquitination and targeting to the proteosome.(25) The antiapoptotic function of XIAP is mediated by inhibition of the apoptotic effector proteins caspase-3, -7 and -9. Furthermore, binding of XIAP to the mitochondrial protein Smac prevents its interaction with, and activation of, pro-caspase-9.(37) All in all, we have observed CP-690,550-mediated dose–response increases in the proportion of cells with reduced mitochondrial membrane potential, diminishing XIAP levels, and activation of procaspase-3. In summary, our results indicate that CP-690,550 is inducing apoptosis by inhibiting the survival pathway mediated by signaling through JAK2–STAT3 in the transduced mouse cell lines.

Treatment of ex-vivo-expanded erythroid progenitors from JAK2V617F-positive PV patients, and healthy controls, with CP-690,550 paralleled our observations with the murine reporter cell lines. Similar to FDCP-EpoR JAK2V617F cells, CP-690,550 displayed selectivity in both antiproliferative and pro-apoptotic activity towards JAK2V617F-positive expanded PV progenitor cells. Expanded PV progenitor cells treated with CP-690,550 were sorted by flow cytometry for live cells belonging to the erythroid lineage. A decrease in JAK2 mutant allele frequency was noted in the three sorted PV samples analyzed. Moreover, a pronounced decrease in JAK2V617F allele frequency, owing to drug exposure, was observed on sorted ex-vivo-expanded progenitors from a homozygous JAK2V617F-positive PV patient. Taken together, our results suggest that CP-690,550 may be more selective towards cells expressing the JAK2V617F mutant protein kinase. Based on our results, CP-690,550 might have a discriminative effect between JAK2V617F heterozygous and homozygous PV patients, which could have important clinical and therapeutic implications. Further, these results also imply that JAK2V617F inhibitors may possibly be more efficacious in patients with higher JAK2V617F/JAK2WT ratios.

Collectively, our data indicate that CP-690,550 selectively inhibits JAK2V617F-positive cells in ex-vivo-expanded progenitors from PV patients, and that this activity appears to lead to a decrease in the clonal JAK2V617F-positive progenitor population. Therefore, continuous therapeutic administration of JAK2V617F inhibitors may lead to suppression of malignant clonal progenitors and expansion of normal hematopoiesis. Validation of this hypothesis will come as a result of ongoing clinical trials using novel JAK2 inhibitors. The scenario described above resembles previous observations with chronic myelogenous leukemia patients treated with imatinib. In this setting, the malignant BCR-ABL1-positive clone was suppressed as a consequence of continuous therapy with imatinib, resulting in repopulation of the bone marrow by normal hematopoietic progenitors.(31,38,39)

In summary, we provide compelling evidence that CP-690,550 effectively inhibits proliferation of cells harboring the JAK2V617F mutation. In addition, treatment of ex-vivo-expanded erythroid progenitors from JAK2V617F-positive PV patients was associated with a decrease in mutant allele burden. A recent report by Pardanani and colleagues using the JAK2 inhibitor TG101209 support our observations with CP-690,550, emphasizing the need for development of molecularly targeted therapies, and their rapid translation into clinical trials.(40)

Acknowledgments

T. Manshouri, A. Quintas-Cardama, and R.H. Nussenzveig designed the study, performed research, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. A Gaikwad performed research, analyzed data and reviewed the manuscript. Z. Estrov, J.E. Cortes and H.M. Kantarjian analyzed data and reviewed the manuscript. S. Verstovsek designed the study, analyzed data, wrote the manuscript and funded the studies. Mouse FDCP-EpoR cells transduced with retroviral vectors carrying human JAK2WT or JAK2V617F were a kind gift from Drs William Vainchenker and Josef Prchal. We are grateful to Ying Zhang for technical assistance with PV patient and healthy control samples. Dr Karen Dwyer from the flow cytometry core facility at M. D. Anderson Cancer Center (supported by NCI Cancer Center Core grant CA16672) for assistance in cell sorting and data interpretation. Finally, we are greatly indebted to the patients, who so selflessly consented to our studies in spite of their personal predicament.

Footnotes

None of the authors declare a financial interest in any products described herein.

References

- 1.Adamson JW, Fialkow PJ, Murphy S, Prchal JF, Steinmann L. Polycythemia vera: stem-cell and probable clonal origin of the disease. N Engl J Med. 1976 Oct 21;295(17):913–916. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197610212951702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spivak JL. The chronic myeloproliferative disorders: clonality and clinical heterogeneity. Semin Hematol. 2004 Apr;41(2 Suppl 3):1–5. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2004.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levine RL, Wadleigh M, Cools J, et al. Activating mutation in the tyrosine kinase JAK2 in polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and myeloid metaplasia with myelofibrosis. Cancer Cell. 2005 Apr;7(4):387–397. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baxter EJ, Scott LM, Campbell PJ, et al. Acquired mutation of the tyrosine kinase JAK2 in human myeloproliferative disorders. Lancet. 2005 Mar 19–25;365(9464):1054–1061. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71142-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.James C, Ugo V, Le Couedic JP, et al. A unique clonal JAK2 mutation leading to constitutive signalling causes polycythaemia vera. Nature. 2005 Apr 28;434(7037):1144–1148. doi: 10.1038/nature03546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kralovics R, Passamonti F, Buser AS, et al. A gain-of-function mutation of JAK2 in myeloproliferative disorders. N Engl J Med. 2005 Apr 28;352(17):1779–1790. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao R, Xing S, Li Z, et al. Identification of an acquired JAK2 mutation in polycythemia vera. J Biol Chem. 2005 Jun 17;280(24):22 788–22 792. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500138200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bellanne-Chantelot C, Chaumarel I, et al. Genetic and clinical implications of the Val617Phe JAK2 mutation in 72 families with myeloproliferative disorders. Blood. 2006 Jul 1;108(1):346–352. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-4852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karow A, Waller C, Reimann C, Niemeyer CM, Kratz CP. JAK2 mutations other than V617F: a novel mutation and mini review. Leuk Res. 2007;32:365–366. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2007.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kratz CP, Boll S, Kontny U, Schrappe M, Niemeyer CM, Stanulla M. Mutational screen reveals a novel JAK2 mutation, L611S, in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2006 Feb;20(2):381–383. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee JW, Kim YG, Soung YH, et al. The JAK2 V617F mutation in de novo acute myelogenous leukemias. Oncogene. 2006 Mar 2;25(9):1434–1436. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malinge S, Ben-Abdelali R, Settegrana C, et al. Novel activating JAK2 mutation in a patient with Down syndrome and B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2007 Mar 1;109(5):2202–2204. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-045963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mercher T, Wernig G, Moore SA, et al. JAK2T875N is a novel activating mutation that results in myeloproliferative disease with features of megakaryoblastic leukemia in a murine bone marrow transplantation model. Blood. 2006 Oct 15;108(8):2770–2779. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-014712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schnittger S, Bacher U, Kern W, Schroder M, Haferlach T, Schoch C. Report on two novel nucleotide exchanges in the JAK2 pseudokinase domain. D620e E627E Leukemia. 2006 Dec;20(12):2195–2197. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scott LM, Tong W, Levine RL, Scott MA, Beer PA, Stratton MR, et al. JAK2 exon 12 mutations in polycythemia vera and idiopathic erythrocytosis. N Engl J Med. 2007 Feb 1;356(5):459–468. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang SJ, Li JY, Li WD, Song JH, Xu W, Qiu HX. The investigation of JAK2 mutation in Chinese myeloproliferative diseases-identification of a novel C616Y point mutation in a PV patient. Int J Lab Hematol. 2007 Feb;29(1):71–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2257.2006.00864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Druker BJ, Sawyers CL, Kantarjian H, et al. Activity of a specific inhibitor of the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase in the blast crisis of chronic myeloid leukemia and acute lymphoblastic leukemia with the Philadelphia chromosome. N Engl J Med. 2001 Apr 5;344(14):1038–1042. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104053441402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cortes J, Kantarjian H. Beyond chronic myelogenous leukemia: potential role for imatinib in Philadelphia-negative myeloproliferative disorders. Cancer. 2004 May 15;100(10):2064–2078. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Changelian PS, Flanagan ME, Ball DJ, et al. Prevention of organ allograft rejection by a specific janus kinase 3 inhibitor. Science. 2003 Oct 31;302(5646):875–878. doi: 10.1126/science.1087061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pan J, Quintas-Cardama A, Kantarjian HM, et al. EXEL-0862, a novel tyrosine kinase inhibitor, induces apoptosis in vitro and ex vivo in human mast cells expressing the KIT D816V mutation. Blood. 2007 Jan 1;109(1):315–322. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-013805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaikwad A, Nussenzveig R, Liu E, Gottshalk S, Chang K, Prchal JT. In vitro expansion of erythroid progenitors from polycythemia vera patients leads to decrease in JAK2 V617F allele. Exp Hematol. 2007 Apr;35(4):587–595. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gaikwad A, Verstovsek S, Yoon D, et al. Imatinib effect on growth and signal transduction in polycythemia vera. Exp Hematol. 2007 Jun;35(6):931–938. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nussenzveig RH, Swierczek SI, Jelinek J, et al. Polycythemia vera is not initiated by JAK2V617F mutation. Exp Hematol. 2007 Jan;35(1):32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levine RL, Wernig G. Role of JAK-STAT signaling in the pathogenesis of myeloproliferative disorders. Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2006;233–9:510. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2006.1.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dan HC, Sun M, Kaneko S, et al. Akt phosphorylation and stabilization of X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) J Biol Chem. 2004 Feb 13;279(7):5405–5412. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312044200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tefferi A, Gilliland DG. Oncogenes in myeloproliferative disorders. Cell Cycle. 2007 Mar;6(5):550–566. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.5.3919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saharinen P, Takaluoma K, Silvennoinen O. Regulation of the Jak2 tyrosine kinase by its pseudokinase domain. Mol Cell Biol. 2000 May;20(10):3387–3395. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.10.3387-3395.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seubert N, Royer Y, Staerk J, et al. Active and inactive orientations of the transmembrane and cytosolic domains of the erythropoietin receptor dimer. Mol Cell. 2003 Nov;12(5):1239–1250. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00389-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wojchowski DM, Gregory RC, Miller CP, Pandit AK, Pircher TJ. Signal transduction in the erythropoietin receptor system. Exp Cell Res. 1999 Nov 25;253(1):143–156. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu X, Levine R, Tong W, et al. Expression of a homodimeric type I cytokine receptor is required for JAK2V617F-mediated transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005 Dec 27;102(52):18 962–18 967. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509714102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mauro MJ, Druker BJ. STI571: a gene product-targeted therapy for leukemia. Curr Oncol Report. 2001 May;3(3):223–227. doi: 10.1007/s11912-001-0054-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burdelya L, Catlett-Falcone R, Levitzki A, et al. Combination therapy with AG-490 and interleukin 12 achieves greater antitumor effects than either agent alone. Mol Cancer Ther. 2002 Sep;1(11):893–899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burke WM, Jin X, Lin HJ, et al. Inhibition of constitutively active Stat3 suppresses growth of human ovarian and breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2001 Nov 29;20(55):7925–7934. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lai SY, Childs EE, Xi S, et al. Erythropoietin-mediated activation of JAK-STAT signaling contributes to cellular invasion in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oncogene. 2005 Jun 23;24(27):4442–4449. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meydan N, Grunberger T, Dadi H, et al. Inhibition of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia by a Jak-2 inhibitor. Nature. 1996 Feb 15;379(6566):645–648. doi: 10.1038/379645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jamieson CH, Gotlib J, Durocher JA, et al. The JAK2 V617F mutation occurs in hematopoietic stem cells in polycythemia vera and predisposes toward erythroid differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006 Apr 18;103(16):6224–6229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601462103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deveraux QL, Roy N, Stennicke HR, et al. IAPs block apoptotic events induced by caspase-8 and cytochrome c by direct inhibition of distinct caspases. Embo J. 1998 Apr 15;17(8):2215–2223. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.8.2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gorre ME, Mohammed M, Ellwood K, et al. Clinical resistance to STI-571 cancer therapy caused by BCR-ABL gene mutation or amplification. Science. 2001 Aug 3;293(5531):876–880. doi: 10.1126/science.1062538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hochhaus A, Kreil S, Corbin A, et al. Roots of clinical resistance to STI-571 cancer therapy. Science. 2001 Sep 21;293(5538):2163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pardanani A, Hood J, Lasho T, et al. TG101209, a small molecule JAK2-selective kinase inhibitor potently inhibits myeloproliferative disorder-associated JAK2V617F and MPLW515L/K mutations. Leukemia. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404750. Prepublished on May 31, 2007 May 31: as DOI 10.1038/sj.leu.2404750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]