Abstract

We have recently developed a bivalent strategy to provide novel compounds that potentially target multiple risk factors involved in the development of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Our previous studies employing a bivalent compound with a shorter spacer (17MN) implicated that this compound can localize into mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum (ER), thus interfering with the change of mitochondria membrane potential (ΔΨm) and Ca2+ levels in MC65 cells upon removal of tetracycline (TC). In this report, we examined the effects by a bivalent compound with a longer spacer (21MO) in MC65 cells. Our results demonstrated that 21MO suppressed the change of ΔΨm, possibly via interaction with the mitochondrial complex I in MC65 cells. Interestingly, 21MO did not show any effects on the Ca2+ level upon TC removal in MC65 cells. Our previous studies suggested that the mobilization of Ca2+ in MC65 cells, upon withdraw of TC, is originated from ER, so the results implicated that 21MO may preferentially interact with mitochondria in MC65 cells under the current experimental conditions. Collectively, the results suggest that bivalent compounds with varied spacer length and cell membrane anchor moiety may exhibit neuroprotective activities via different mechanisms of action.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, bivalent compound, calcium, mitochondria, multifunctional, neuroprotection

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a devastating neurodegenerative disorder and the most common cause of dementia.[1] The complexity of this disease makes drug development efforts to provide effective disease modifying agents a challenging and unmet task since multiple pathogenic factors have been implicated in the development of AD, such as amyloid-β (Aβ) aggregates,[2–5] oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and mitochondria dysfunction, among others.[6–8] To address this challenge, the multifunctional strategy of small molecule design by employing molecular conjugation or hybridization has recently attracted extensive attention in surmounting the paucity of effective disease-modifying agents in the pipeline of AD therapeutics.[9–11]

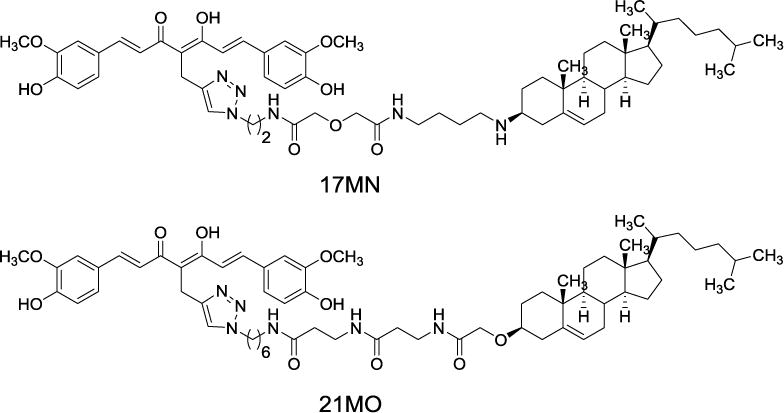

Recently, we developed a novel bivalent ligand strategy to link a multifunctional “war head”, namely curcumin, with a cell membrane/lipid raft (CM/LR) anchor moiety into our molecular design.[12–14] Our results demonstrated that this bivalent strategy provided compounds with significantly improved neuroprotection compared to either curcumin or the CM/LR anchor alone, or the combination of these two.[12–14] The spacer length between the “war head” and the anchorage moiety proved to be critical for their neuroprotections. Further mechanistic studies employing one of these lead bivalent compounds as a probe (17MN, Figure 1) demonstrated that our bivalent compound can reverse the change of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) and cytosolic Ca2+ levels induced by the withdrawal of tetracycline (TC) in our MC65 cell model system, thus protecting MC65 cells from TC-removal induced necroptosis.[15] MC65 is a human neuroblastoma cell line that conditionally expresses a 99-residue carboxyl terminal fragment of Aβ precursor protein (APP) and Aβ after removal of TC. This cell line is widely recognized as one of the cellular models of AD, resulting in intracellular Aβ oligomers (AβOs) formation and oxidative stress. Furthermore, our studies indicated that 17MN interacts with both mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum (ER), thus suggesting a multiple-site mechanism for the observed neuroprotective activities in MC65 cells for our bivalent compounds. Our studies also noticed that bivalent compounds with varied spacer lengths exhibit differential neuroprotection profile in MC65 cells.[12–15] Therefore it would be interesting to examine how these bivalent compounds with varied spacer lengths behave differentially in the cellular model system. Herein, we report the characterization of another lead bivalent compound, 21MO (Figure 1), with a longer spacer, in MC65 cells and compare its effects on MMP and Ca2+ change to our previously reported bivalent compound 17MN.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of 17MN and 21MO.

2. Results and Discussion

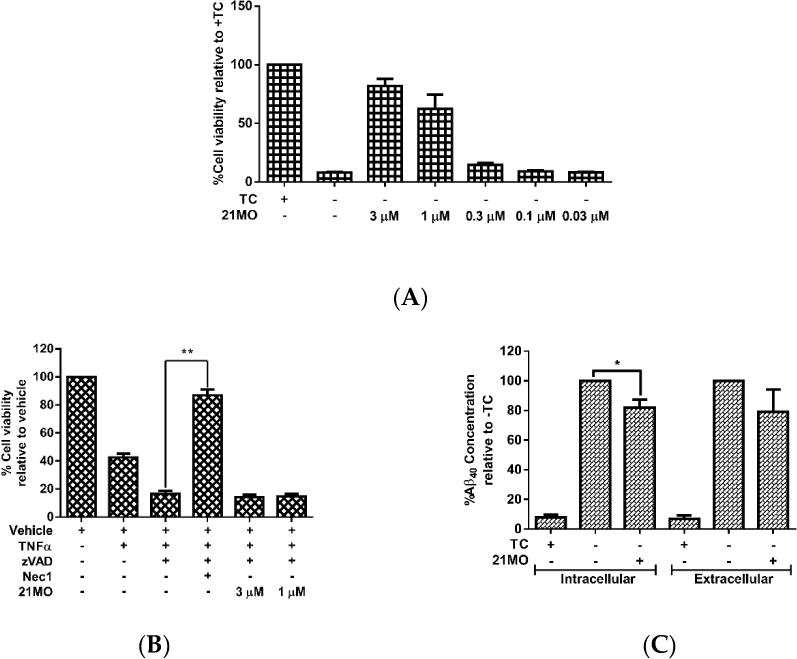

Our previous studies have shown that, upon removal of TC, MC65 cells die through necroptosis and bivalent compounds 17MN protects MC65 cells from TC-removal induced cytotoxicity by engaging target proteins between receptor interacting protein kinase-1 (RIPK1) and Aβ.[15] Therefore, we initially tested 21MO in MC65 cells to compare whether it functions similarly to 17MN. The results demonstrated that 21MO can efficiently rescue MC65 cells from TC-removal induced necroptosis (Figure 2A) and but could not rescue TNF/zVAD induced necroptosis in U937 cells (Figure 2B), thus suggesting that 17MN and 21MO may function similarly in MC65 cells under the current experimental conditions. Further studies also demonstrated that 21MO (1 μM) slightly decreased the intracellular level of Aβ40, but did not interfere with the level of extracellular Aβ40 (Figure 2C). Overall, 21MO did not significantly inhibit the total production of Aβ40, especially when comparing the reduction of intracellular Aβ40 with the neuroprotective activity of 21MO at this concentration. Our previous studies demonstrated that 21MO exhibits inhibitory effects on the aggregation of small AβOs, but with a much weaker potency compared to its inhibition of MC65 cell death,[15] thus suggesting that the inhibition of Aβ aggregation might only contribute partially towards its overall neuroprotective ability. Taken together, the results suggest that other proteins are involved in the observed neuroprotective activities by these bivalent compounds in MC65 cells.

Figure 2.

The influence of 21MO on the necroptosis and total Aβ40. A) MC65 cells were treated with 21MO (1 μM) under -TC conditions for 72 h. Cell viability was assessed by MTT assay. B) U937 cells were pretreated with 21MO (1 or 3 µM) or Necrostatin-1 (10 µM) and caspase pan inhibitor zVAD (10 µM) for 1h, then TNF-α (50 ng/mL) was added and incubated for 72 h. Cell viability was assessed by MTT assay. (**p < 0.01). C) MC65 cells were treated with 21MO (1 µM) under -TC conditions for 48 h. Medium was collected for analysis of extracellular Aβ40. Cells were lysed and analyzed for intracellular Aβ40. Total Aβ40 concentrations were normalized by total protein content of lysed cells. (*p < 0.05).

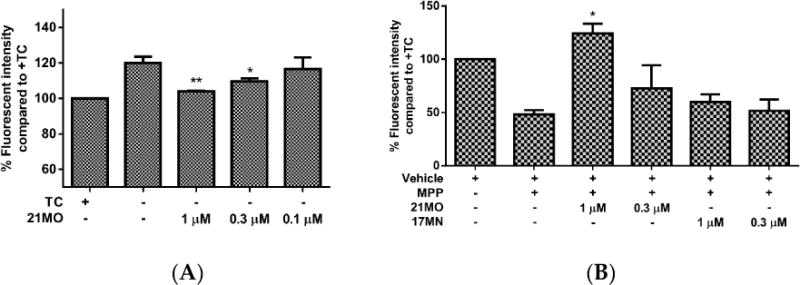

Next, we set to examine the effects of 21MO on the change of MMP upon the removal of TC in MC65 cells in comparison with 17MN. Consistent with our previous results, the MC65 cells are hyperpolarized (increase in MMP) after the removal of TC and this may indicate the interactions of AβOs with mitochondria caused the change of MMP. Notably, 21MO suppressed the increase of ΔΨm at 0.3 and 1 µM concentrations (Figure 3A). This may suggest that our bivalent compounds, regardless of spacer lengths, interact with mitochondria to interfere with the effects of AβOs on the mitochondria. Our recent studies have shown that, reactive oxygen species (ROS), especially mitochondrial ROS (mitoROS), are involved in the cell death of MC65 cells.[13,16] Furthermore, complex I of the electron transport chain is associated with the production of mitoROS,[17] Then, another cellular model employing neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells in the presence of MPP+, a neurotoxin targeting the complex I of mitochondria, was employed to test the effects of 21MO on the MMP change. Upon addition of MPP+ the mitochondria of SH-SY5Y cells were depolarized (decrease of MMP) and notably 21MO reversed the MMP change at 1 μM, but 17MN did not, under the same experimental settings (Figure 3B). Combining the results from MC65 cells, it may indicate that 21MO can reverse the changes induced by either production of AβOs in MC65 cells or MPP+ in SH-SY5Y cells on mitochondria, but 21MO probably does not affect the MMP by itself.

Figure 3.

The influence of 21MO on mitochondrial potential. A) MC65 cells were treated with 21MO at indicated concentrations under -TC condition for 48 h. Cells were then incubated with TMRM (100 nM) for 30 min. Mean fluorescence intensity was measured by flow cytometry. (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 compared to -TC). B) SH-SY5Y cells were treated with either 21MO or 17MN at indicated concentrations and MPP+ (2.5 mM) for 24 h. Cells were then incubated with TMRM (100 nM) for 30 min. Mean fluorescence intensity was measured by flow cytometry. (*p < 0.05 compared to MPP treated group).

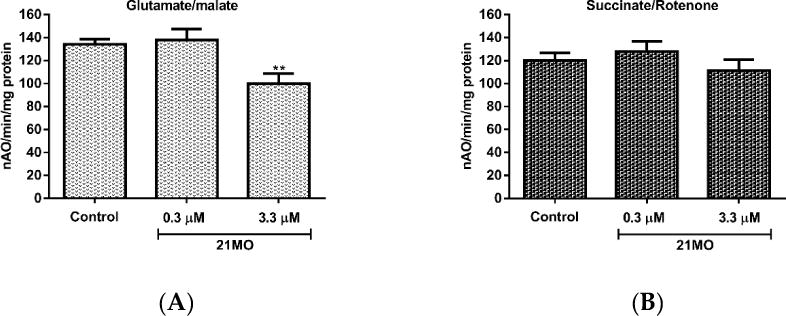

Taken together, the results might suggest that 17MN and 21MO interact differentially with mitochondria with 21MO being more selective to complex I proteins, but these potential mitochondrial proteins all underlie the AβO-induced MMP change. To further confirm this notion and examine whether 17MN and 21MO interact with mitochondria differently, we tested 21MO in the isolated brain mitochondria of mice for its effects on oxy-phosphorylation. Our previous studies have demonstrated that 17MN does not show any significant effects on the oxy-phosphorylation of brain mitochondria.[15] As shown in Figure 4, notably, 21MO significantly decreased the oxidation of glutamate (Figure 4A), the substrate of complex I, but not succinate, the substrate of complex II (Figure 4B), thus suggesting that 21MO may preferentially target the complex I of brain mitochondria, which is consistent with results from the SH-SY5Y model.

Figure 4.

Effects of 21MO on the oxy-phosphorylation of mouse brain mitochondria. A) and B) Oxygen consumption in mitochondria was measured using a Clark-type oxygen electrode at 30 °C using glutamate/malate (A) and using succinate/rotenone (B) in the presence or absence of 21MO (**p < 0.01).

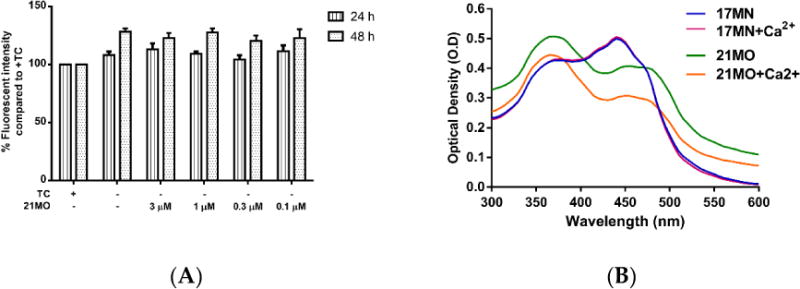

Our previous studies demonstrated that withdrawal of TC resulted in a significant rise of intracellular Ca2+ levels in MC65 cells and the mobilization of Ca2+ originated from ER. Furthermore, 17MN can efficiently suppress the increased Ca2+ level.[15] Therefore, we decided to compare the effects of 21MO on Ca2+ levels upon TC-removal in MC65 cells to that of 17MN. Surprisingly, 21MO did not show any significant effects on the increased Ca2+ level at concentrations up to 3 μM (Figure 5A) after 24 and 48 hours of TC removal. Our previous results have shown that 17MN dose-dependently prevented this increase.[15] The time dependent change of Ca2+ upon TC removal is consistent with the production of AβOs [12], thus suggesting a role of Aβ in the calcium mobilization in this cell model. Further chelating experiments suggested that 21MO does not a form complex with Ca2+ as evident by the unchanged maximum absorption (Figure 5B), similar to the results of 17MN.

Figure 5.

The impact of 21MO on cytosolic Ca2+ levels in MC65 cells under -TC conditions. A) MC65 cells were treated with 21MO at indicated concentrations under -TC conditions for 24 and 48 h. Cells were then incubated with Fluo-4AM (2 μM) for 30 min. Mean fluorescence intensity was measured by flow cytometry. B) Both 17MN and 21MO (50 μM) were incubated with CaCl2 (60 μM) at room temperature for 10 min, then the UV-vis spectrum was recorded from 300 nm to 600 nm.

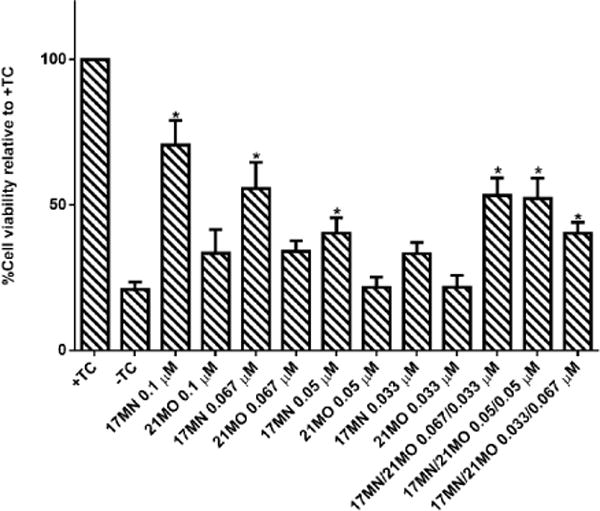

Our previous studies suggested that 17MN can readily pass into MC65 cells and localize into both mitochondria and ER, consistent with the observed effects of 17MN on both MMP and Ca2+ change. The results of 21MO in MC65 cells may suggest that this bivalent compound with a longer spacer may preferentially interact with mitochondria, but not ER, to exert its neuroprotective activities. The results also implicate that upon the production of Aβ, especially AβOs, in MC65 cells, multiple pathways are potentially involved to elicit the observed cell death, consistent with the pathogenic complex nature of AD. Our previous studies observed the potency difference of 17MN and 21MO in protecting MC65 cells with 17MN being more potent. This may echo the fact that 17MN can interfere with both mitochondria and ER while 21MO only preferentially interfere with mitochondria in MC65 cells, thus consistent with our original design rationale of developing compounds with multifunctionality as effective treatments for AD. To further confirm this, we tested 17MN, 21MO, and the combination of these two for the protective activities under TC-removal conditions in MC65 cells. As shown in Figure 6, 17MN rescued MC65 cells up to 71% survival at 0.1 μM while 21MO can only slightly increase the survival rate of MC65 cells to 33% at the same concentration, consistent with our previous results.[12,13] When examining various combinations of 17MN and 21MO with the total concentration being 0.1 μM, the results showed that the observed protections from these combinations are comparable to that of 17MN alone at corresponding concentrations. The results are consistent with the observed mechanistic study results and our hypothesis that the observed optimal protections of MC65 cells by 17MN are probably due to its dual interactions with both mitochondria and ER, compared to 21MO’s preferential interaction with only mitochondria.

Figure 6.

Protective activities of 17MN, 21MO or the combination of 17MN and 21MO on MC65 cells. MC65 cells were treated with indicated compounds at indicated concentration under –TC conditions for 72 hours. Then cell viability was measured by MTT assay. Data were presented as mean (n=4) ± SEM (*p < 0.05 compared to -TC).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1 Cell Lines and Reagents

MC65 cells (kindly provided by Dr. George M. Martin at the University of Washington, Seattle) were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) (Life Technologies, Inc., Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% of heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Hyclone, Logan, UT), 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin (P/S) (Invitrogen), 1 μg/mL Tetracycline (TC) (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and 0.2 mg/mL G418 (Invitrogen). SH-SY5Y cells (ATCC) were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% P/S. All cells were maintained at 37 °C in a fully humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

3.2 MC65 Neuroprotection assay

MC65 cells were washed twice with PBS, resuspended in Opti-MEM, and seeded in 96-well plates (4×104 cells/well). Indicated compounds were then added, and cells were incubated at 37°C under –TC conditions for 72 h. Then, 10 μL of MTT solution (3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide 5 mg/mL in PBS) were added and the cells were incubated for another 4 h. Cell medium was then removed, and the remaining formazan crystals produced by the cellular reduction of MTT were dissolved in 100 μL of DMSO. Absorbance at 570 nm was immediately recorded using a FlexStation 3 plate reader (Molecular Devices, CA). Values were expressed as a percentage relative to those obtained in the +TC controls.

3.3 U937 Necroptosis assay

U937 cells (2×104 cells) were pretreated with compound and caspase pan inhibitor Z-VAD for 1h. TNF-α was then added and cells were incubated for 72 h. Afterward, 10 μL of MTT solution was added and cells were incubated for an additional 4 h. Cell medium was then removed, and the remaining formazan crystals produced by the cellular reduction of MTT were dissolved in 100 µL of DMSO. Absorbance at 570 nm was immediately recorded using a FlexStation 3 plate reader. Values were expressed as a percentage relative to those obtained in untreated controls.

3.4 Aβ40 ELISA

MC65 cells were collected and washed twice with PBS, resuspended in Opti-MEM, seeded in 6 well plates (1.6×106 cells/well), and incubated with compounds at 37 °C under -TC conditions for 48 h. After centrifugation of the plates, 2 mL of medium was carefully collected for analysis of Aβ40 in medium. Cell pellets were lysed by cell extraction buffer (Life Technologies) following the manufacturer’s instructions and the total protein content was quantified by the Bradford method. Samples were analyzed using the Aβ40 Human ELISA Kit (Life Technologies) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The results were normalized by total protein expressed as a percentage relative to those obtained in the -TC control.

3.5 MC65 Mitochondrial membrane potential assay

MC65 cells were collected and washed twice with PBS, resuspended in Opti-MEM, seeded in 6 well plates (1.6×106 cells/well), and incubated with compounds at 37 °C under -TC conditions for 48 h. Cells were then collected, washed twice with PBS, and then incubated with 100 nM of tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester (TMRM) in PBS at room temperature for 30 min. Fluorescence was analyzed by flow cytometry.

3.6 SH-SY5Y Mitochondrial membrane potential assay

SH-SY5Y cells (4×105 cells) were plated in 12 well plates. After incubation for 24 h, growth medium was removed and cells were treated in DMEM with indicated compounds and MPP+ (2.5 mM) for 24 h. TMRM was then added to a final concentration of 100 nM and the cells were further incubated for 30 min. The medium was then collected. The cells were detached by trypsinization, and the medium was then recombined with the cells and centrifuged. After removing the supernatant, the cell pellet was suspended in PBS and the mean fluorescent intensity was recorded by flow cytometry.

3.7 Brain mitochondrial isolation and functional determination

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUC) of the McGuire VA Medical Center and Virginia Commonwealth University approved this protocol. Brain cortex tissue was collected from C57BL/6 mice after the mouse was anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (100 mg/kg i.p.) and the heart was removed. Harvested brain tissue was placed into 5 mL MSM buffer (210 mM Mannitol, 70 mM Sucrose, 5.0 mM MOPS, 1.0 mm EDTA, pH 7.4) at 4 °C, and finely minced and incubated with Subtilisin A (1 mg/g tissue) for 1 min. Another 5 mL MSM buffer including 0.2% BSA was added to incubated tissue that was then homogenized by one stroke using a Teflon pestle. The homogenate was centrifuged at 600 g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was then centrifuged at 5000 g for 10 min at 4 °C to spin down the mitochondria. The mitochondrial pellet was washed once with MSM buffer, then re-suspended in 100–200 μL of MSM buffer. Total protein concentration was measured by the Lowry method using BSA as a standard. Oxygen consumption in mitochondria was measured by a Clark-type oxygen electrode at 30 °C using glutamate + malate (complex I substrates) and succinate + rotenone (complex II substrates) in the presence or absence of compound 17MN.[18]

3.8 MC65 Calcium level measurement

MC65 cells were washed twice with PBS, resuspended in Opti-MEM, and seeded in 6-well plates (1.6×106 cells/well). Indicated compounds were then added, and cells were incubated at 37 °C under -TC conditions for 48 h. Cells were then harvested, suspended in PBS, and incubated with Fluo-4AM (2 μM) in dark for 30 min. Cells were washed once and then resuspended in PBS. Samples were analyzed by flow cytometry. Values were expressed as a percentage relative to those obtained in -TC controls.

3.9 Biometal complex assay

Compound 17MN and 21MO (50 μM) were incubated along with CaCl2 (60 μM) in water (100 μL) were incubated at room temperature for 10 min, then UV absorption was recorded from 300 nm to 600 nm using a FlexStation 3 plate reader.

3.10 Statistical analyses

The Student’s t-test was used for all statistical analysis. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. The level of significance for all analysis testing was set at *P < 0.05.

4. Conclusions

In summary, our studies suggested that bivalent compound 21MO can protect MC65 cells from TC-removal induced necroptosis, probably via interactions with the complex I of mitochondria. But 21MO did not have any impact on the Ca2+ change under the current experimental settings. The results collectively suggest that 17MN and 21MO may have different mechanisms of action for their neuroprotective activities, even though they share the same overall structure with both curcumin and a cell membrane anchor moieties linked by a spacer. This also suggests that the cell membrane anchor and the spacer do play an important role in their biological activities, consistent with our original design rationale and reported results. Further studies are being undertaken to evaluate specifically the impact of spacer or cell membrane anchor on their biological activities by employing newly designed bivalent probes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. George M. Martin at the University of Washington, Seattle for kindly providing the MC65 cells. The work was supported in part by the NIA of the NIH under award number R01AG041161 (S.Z.) and Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation (S.Z.), Scientist Development Grant (11SDG5120011) and a Grant-in-aid (15GRNT24480123) from the American Heart Association (Q.C.), VCU’s CTSA (UL1TR000058 from the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Science) and the CCTR Endowment Fund of the Virginia Commonwealth University (Q.C.), the Office of Research and Development, Medical Research Service Merit Review Award (1IO1BX001355-01A1), Department of Veterans Affairs (E.J.L.), and the Pauley Heart Center, Virginia Commonwealth University (Q.C., E.J.L.)

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Chemical synthesis of 21MO was completed by J.M.S. and K.L.; Cell assays using MC65 and SH-SY5Y cells were performed by J.E.C., K.L., and H.L.; Brain mitochondria work was completed by Q.C. and E.J.L.; Data analysis was completed by J.M.S. and S.Z.; Experiment and project design was done by S.Z.; Writing and editing were completed by J.M.S. and S.Z.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Sample Availability: Samples of the compound 21MO are available from the authors.

Contributor Information

John M. Saathoff, Email: saathoffjm@vcu.edu.

Kai Liu, Email: kliu4@vcu.edu.

Jeremy E. Chojnacki, Email: chojnackij@vcu.edu.

Liu He, Email: lhe3@vcu.edu.

Qun Chen, Email: qchen8@vcu.edu.

Edward J. Lesnefsky, Email: ejlesnefsky@vcu.edu.

References

- 1.2015 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:332–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. Science. Vol. 297. New York, N.Y: 2002. The amyloid hypothesis of alzheimer’s disease: Progress and problems on the road to therapeutics; pp. 353–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirkitadze MD, Bitan G, Teplow DB. Paradigm shifts in alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders: The emerging role of oligomeric assemblies. J Neurosci Res. 2002;69:567–577. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walsh DM, Selkoe DJ. A beta oligomers - a decade of discovery. J Neurochem. 2007;101:1172–1184. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Selkoe DJ. Soluble oligomers of the amyloid beta-protein impair synaptic plasticity and behavior. Behav Brain Res. 2008;192:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bush AI. Drug development based on the metals hypothesis of alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2008;15:223–240. doi: 10.3233/jad-2008-15208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu X, Su B, Wang X, Smith MA, Perry G. Causes of oxidative stress in alzheimer disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:2202–2210. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7218-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eckert GP, Renner K, Eckert SH, Eckmann J, Hagl S, Abdel-Kader RM, Kurz C, Leuner K, Muller WE ; Mitochondrial dysfunction–a pharmacological target in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurobiol. 2012;46:136–150. doi: 10.1007/s12035-012-8271-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Viegas-Junior C, Danuello A, da Silva Bolzani V, Barreiro EJ, Fraga CA. Molecular hybridization: A useful tool in the design of new drug prototypes. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14:1829–1852. doi: 10.2174/092986707781058805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tietze LF, Bell HP, Chandrasekhar S. Natural product hybrids as new leads for drug discovery. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2003;42:3996–4028. doi: 10.1002/anie.200200553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carreiras MC, Mendes E, Perry MJ, Francisco AP, Marco-Contelles J. The multifactorial nature of alzheimer’s disease for developing potential therapeutics. Curr Top Med Chem. 2013;13:1745–1770. doi: 10.2174/15680266113139990135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lenhart JA, Ling X, Gandhi R, Guo TL, Gerk PM, Brunzell DH, Zhang S. “Clicked” bivalent ligands containing curcumin and cholesterol as multifunctional abeta oligomerization inhibitors: Design, synthesis, and biological characterization. J Med Chem. 2010;53:6198–6209. doi: 10.1021/jm100601q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu K, Gandhi R, Chen J, Zhang S. Bivalent ligands targeting multiple pathological factors involved in alzheimer’s disease. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2012;3:942–946. doi: 10.1021/ml300229y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chojnacki JE, Liu K, Saathoff JM, Zhang S. Bivalent ligands incorporating curcumin and disogenin as multifunctional compounds against Alzheimer’s disease. Biorg & Med Chem. 2015;23:7324–7331. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc2015.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu K, Chojnacki JE, Wade EE, Saathoff JM, Lesnefsky EJ, Chen Q, Zhang S. Bivalent compound 17MN exerts neuroprotection through interaction at multiple sites in a cellular model of alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;47:1021–1033. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chojnacki JE, Liu K, Yan X, Toldo S, Selden T, Estrada M, Rodriguez-Franco MI, Halquist MS, Ye D, Zhang S. Discovery of 5-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-3-oxo-pentanoic acid [2-(5-methoxy-1H-indol-3-yl)-ethyl]-amide as a neuroprotectant for Alzheimer’s disease by hybridization of curcumin and melatonin. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2014;5:690–699. doi: 10.1021/cn500081s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koopman WJ, Nijtmans LG, Dieteren CE, Roestenberg P, Valsecchi F, Smeitink JA, Willems PH. Mammalian mitochondrial complex I: biogenesis, regulation, and reactive oxygen species generation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;12:1431–1470. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chinta SJ, Rane A, Yadava N, Andersen JK, Nicholls DG, Polster BM. Reactive oxygen species regulation by AIF- and complex I-depleted brain mitochondria. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46:939–947. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]