Abstract

Background

Current guidelines for prevention of neonatal group B Streptococcal (GBS) disease recommend diagnostic evaluations and empiric antibiotic therapy for well-appearing, chorioamnionitis-exposed newborns. Some clinicians question these recommendations, citing the decline in early-onset GBS disease rates since widespread intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP) implementation and potential antibiotic risks. We aimed to determine whether chorioamnionitis-exposed newborns with culture-confirmed early-onset infections can be asymptomatic at birth.

Methods

Multicenter, prospective surveillance for early-onset neonatal infections was conducted 2006–2009. Early-onset infection was defined as isolation of a pathogen from blood or cerebrospinal fluid collected ≤72 hours after birth. Maternal chorioamnionitis was defined by clinical diagnosis in the medical record or histologic diagnosis by placental pathology. Hospital records of newborns with early-onset infections born to mothers with chorioamnionitis were reviewed retrospectively to determine symptom onset.

Results

Early-onset infections were diagnosed in 389 of 396,586 live births, including 232 (60%) chorioamnionitis-exposed newborns. Records for 229 were reviewed; 29 (13%) had no documented symptoms within 6 hours of birth, including 21 (9%) who remained asymptomatic at 72 hours. IAP exposure did not differ significantly between asymptomatic and symptomatic infants (76% vs. 69%, p=0.52). Assuming complete guideline implementation, we estimated 60 to 1400 newborns would receive diagnostic evaluations and antibiotics for each infected, asymptomatic newborn, depending on chorioamnionitis prevalence.

Conclusions

Some infants born to mothers with chorioamnionitis may have no signs of sepsis at birth despite having culture-confirmed infections. Implementation of current clinical guidelines may result in early diagnosis, but large numbers of uninfected asymptomatic infants would be treated.

Introduction

Despite a substantial reduction in the rate of early-onset group B streptococcal (GBS) infection following widespread implementation of maternal intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP) for GBS disease in the 1990s, neonatal sepsis remains an important cause of morbidity and mortality.1,2 Early recognition of signs of neonatal sepsis and prompt antibiotic therapy is thought to improve neonatal outcomes. Thus, empiric newborn antibiotic therapy in the context of known risk factors for neonatal sepsis, including chorioamnionitis, may reduce sepsis-related morbidity.3–5

Because associations between maternal chorioamnionitis and neonatal GBS disease have been documented in several observational studies,6–8 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2010 Guidelines for Prevention of Perinatal Group B Streptococcal Disease, endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Family Physicians, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, recommend that well-appearing infants born to mothers with chorioamnionitis receive a limited diagnostic evaluation (a complete blood count [CBC] with differential and platelets and a blood culture at birth), and empiric antibiotic therapy.5,9–13 However, since the evidence behind these recommendations was limited to observational studies performed before widespread IAP use, some controversy surrounds the current recommendations. Some clinicians question, given widespread IAP use, whether diagnostic evaluations and empiric antibiotics are warranted for well-appearing, term newborns exposed to chorioamnionitis.14 Additionally, clinicians may be reluctant to separate well-appearing infants from their mothers, if necessary to provide empiric antibiotic therapy, given the potential negative impact on early bonding and initiation of breast feeding, particularly if intrapartum antibiotics mitigate some of the risk of sepsis associated with chorioamnionitis. Further, an association between prolonged empiric antibiotic use and mortality and morbidity has been suggested.15–17 In the absence of an elevated risk for sepsis, these concerns may outweigh potential benefits.

The proportion of chorioamnionitis-exposed newborns with invasive early-onset infections who are well-appearing at birth has not been described. Because chorioamnionitis is uncommon, complicating 0.5–10% of deliveries, this question is difficult to explore at single hospitals, even large hospitals.18–20 Using data from a cohort of infants with early-onset infections identified through a multicenter research consortium, we aimed to determine whether newborns with culture-confirmed early-onset infections born to mothers with chorioamnionitis can be asymptomatic at birth.

Patients and Methods

Prospective surveillance for early-onset neonatal infections was conducted by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network among live-born infants of all gestational ages with birth weights greater than 400 grams who were delivered at one of 16 university-based centers February 2006 through December 2009. The results have been reported previously.1 Detailed information was collected for infants with early-onset infections only. Hospital records of the cases born to mothers diagnosed with chorioamnionitis were retrospectively reviewed in 2013 to obtain more detailed information on presence and timing of onset of clinical signs and symptoms of sepsis, timing of blood cultures and antibiotic therapy, and date and timing of CBC evaluation. Cases whose mothers had clinical chorioamnionitis, defined as a diagnosis of chorioamnionitis documented in the medical record, or histologic chorioamnionitis documented by placental pathology were included in the review. The institutional review board at each participating center approved the review of records; CDC provided funding for the retrospective review, but data collection and analyses were performed by the study sites and RTI International.

Early-onset infections were defined by isolation of a pathogen from blood or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) culture of specimens obtained within 72 hours of birth and antibiotic treatment for ≥5 days (or death <5 days while receiving antibiotic therapy). During the prospective surveillance, cases were identified through review of patient, microbiology, and hospital epidemiology records. Coagulase-negative staphylococci, micrococci, propionibacteria, corynebacteria, or diphtheriods isolated from a single culture were considered contaminants, regardless of site determination of contamination status. Cultures that grew Bacillus species or that grew more than one organism were included unless the attending physician judged the culture contaminated and did not treat the infant or discontinued antibiotics before day 5 in a surviving infant.

During the surveillance study, maternal information was abstracted from labor and delivery records, including GBS screening results, risk factors for early-onset GBS, antibiotic use and clinical signs in the 72 hours before delivery, and documentation of clinical and histologic chorioamnionitis. Risk factors for early-onset GBS included a previous infant with GBS infection, GBS bacteriuria, delivery at <37 weeks’ gestation, rupture of membranes ≥18 hours prior to delivery, and intrapartum fever defined as a temperature ≥100.4 F/≥38.0 C between onset of labor and delivery. Maternal clinical signs included uterine or abdominal tenderness, foul smelling vaginal discharge or amniotic fluid, tachycardia, or any temperature ≥100.4 F/≥38.0 C in the 72 hours prior to delivery without regard to onset of labor. Information abstracted from the infant record included laboratory results, antibiotic therapy, severity of illness, and final status (death or survival to discharge, transfer, or 120 days).

For the present study, infants with early-onset infection and maternal chorioamnionitis were classified as symptomatic at birth if they had any signs of sepsis (Table 1) within 6 hours of birth. Infants with none of the reviewed signs or symptoms of sepsis within the first 6 hours were classified as asymptomatic at birth. Infants born prior to 37 weeks’ gestational age were classified as preterm.

Table 1.

Signs and symptoms of sepsis used to define symptomatic newborns (within 6 hours of birth or within 72 hours of birth).

| Signs or symptoms of sepsis |

|---|

|

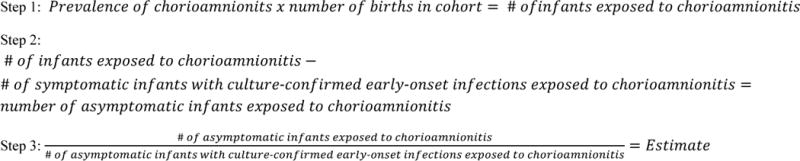

Using the steps in Figure 1, we estimated the number of well-appearing infants, stratified by preterm versus term, born to women with chorioamnionitis potentially treated for each initially asymptomatic infant with culture-confirmed, early-onset infection assuming complete implementation of the Guidelines for Prevention of Perinatal Group B Streptococcal Disease. Since chorioamnionitis prevalence in the birth cohort was unknown, we used a range of prevalence rates from prior reports in our calculation.18–20 We rounded the estimates to 1 significant digit (if under 100) or 2 significant digits to reflect imprecision of the estimates.

Figure 1.

Steps for estimating the number of well-appearing infants born to women with chorioamnionitis potentially treated for each initially asymptomatic infant with culture-confirmed, early-onset infection assuming complete implementation of the Guidelines for Prevention of Perinatal Group B Streptococcal Disease.

Statistical significance for unadjusted comparisons was determined by chi-square or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables or the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, US).

Results

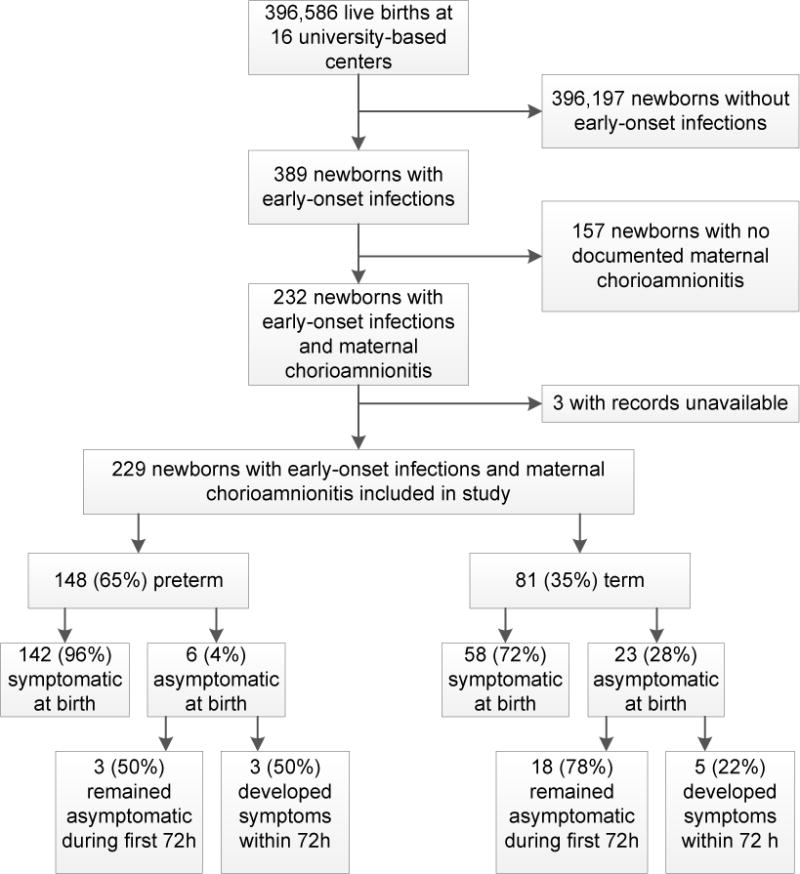

During the surveillance study, 389 cases of culture-confirmed early-onset infection were identified among 396,586 live births at the 16 centers (0.98 cases per 1000 live births). Among infants infected, 232 (60%) were born to women with chorioamnionitis. Because medical records for three infants with maternal chorioamnionitis were unavailable for review, 229 were included in this analysis (Figure 2). Mothers of 110 (48%) infants were diagnosed with both clinical and histologic chorioamnionitis, 77 (34%) with histologic chorioamnionitis only, and 42 (18%) with clinical chorioamnionitis alone (placental pathology was performed but chorioamnionitis not diagnosed for 13/42; placental examination was not performed for 28; information missing for 1) (Table 2). Risk factors for early-onset GBS infection were documented for 202 (89%) deliveries. At least one clinical sign consistent with chorioamnionitis was documented for the mothers of 162 (71%) infants within 72 hours before delivery, including 134/152 (88%) infants whose mothers had a clinical chorioamnionitis diagnosis. A majority of infants were born to mothers who received IAP, including 111 (75%) preterm and 48 (59%) term infants (p=0.02). Penicillin, ampicillin, or cefazolin were included in the maternal regimens of 142 (62% of all infants, 89% of 159 whose mothers received IAP), as recommended by CDC GBS prevention guidelines. However, not all 142 infants were exposed to these drugs ≥4 hours before delivery as recommended (≥4 hours: 79, <4 hours: 13, exact timing could not be determined: 50).

Figure 2.

Flow of subject selection from infants with culture-confirmed early-onset infections identified in the original surveillance study conducted 2006–2009 at 16 university-based centers of the Neonatal Research Network to inclusion in the present retrospective detailed review of infants with early-onset infections and maternal chorioamnionitis.

Table 2.

Maternal characteristics of deliveries producing newborns with culture-confirmed early-onset infections born to women with chorioamnionitis 2006–2009, overall and by gestational age.

| Characteristic1/ | All infants N=229 |

Gestational Age of Newborn | P-value2/ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preterm (22–36 weeks) N=148 |

Term (≥37 weeks) N=81 |

|||

| Age in years, median (range) | 26 (15–41) | 28 (15–41) | 24 (15–39) | 0.002 |

| Chorioamnionitis, n (%) | 0.001 | |||

| Clinical and Histologic | 110 (48) | 76 (51) | 34 (42) | |

| Histologic only | 77 (34) | 55 (37) | 22 (27) | |

| Clinical only | 42 (18) | 17 (11) | 25 (31) | |

| At least 1 GBS risk factor3/ | 202 (89) | 148 (100) | 54 (68) | <0.001 |

| At least 1 GBS risk factor (excluding delivery <37 weeks) | 149 (65) | 95 (64) | 54 (68) | 0.66 |

| Clinical signs of chorioamnionitis in the 72 h prior to delivery | ||||

| Maternal fever4/ | 87 (38) | 38 (26) | 49 (60) | <0.001 |

| Uterine or abdominal tenderness | 52 (23) | 46 (31) | 6 (7) | <0.001 |

| Foul smelling discharge or amniotic fluid | 35 (15) | 27 (18) | 8 (10) | 0.12 |

| Maternal tachycardia (>100 beats per minute | 96 (42) | 62 (42) | 34 (42) | 1.0 |

| At least 1 clinical sign above | 162 (71) | 100 (68) | 62 (77) | 0.17 |

| Maternal fever only | 30 (13) | 6 (4) | 24 (30) | <0.001 |

| IAP exposure, n (%) | 159 (69) | 111 (75) | 48 (59) | 0.02 |

| IAP agent, n (%)5/ | ||||

| Ampicillin | 123 (54) | 85 (57) | 38 (47) | 0.13 |

| Penicillin G | 18 (8) | 17 (11) | 1 (1) | 0.004 |

| Gentamicin | 73 (32) | 39 (26) | 34 (42) | 0.02 |

| Clindamycin | 11 (5) | 7 (5) | 4 (5) | 1.0 |

| Erythromycin | 42 (18) | 42 (28) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Other | 60 (26) | 52 (35) | 8 (10) | <0.001 |

Maternal GBS risk factor information was missing for 1 term infant; timing of IAP exposure was missing for 6 preterm infants.

P-value for a test of whether the characteristic differed by gestational age by Fisher’s exact test (categorical variables) or the Kruskal-Wallis test (maternal age).

GBS risk factors were: previous infant with GBS infection, GBS bacteriuria, rupture of membranes (ROM) ≥18 hours prior to delivery, delivery at <37 weeks’ gestation, and intrapartum fever defined as a temperature ≥100.4 F/38.0 C between onset of labor and delivery.

Maternal fever was defined as any temperature ≥100.4 F/38.0 C in the 72 hours prior to delivery without regard to onset of labor.

Of the 159 women who received antibiotics in the 72 hours prior to and including delivery, 38 (24%) received one drug, 76 (48%) received 2 drugs, 29 (18%) received 3 drugs, and 15 (9%) received 4 or 5 drugs; information was missing for one. For mothers of preterm infants, “other” intrapartum antibiotics included amoxicillin (14 infants), cefazolin (10 infants), ceftriaxone (1 infant), azithromycin (7 infants), metronidazole (2 infants), and other not specified (18 infants). For mothers of term infants, “other” intrapartum antibiotics included cefazolin (4 infants), ceftriaxone (2 infants), azithromycin (1 infant), and vancomycin (1 infant).

The majority of the 229 chorioamnionitis-exposed infants with early-onset infection were born at preterm gestation (preterm: 148 [65%]; term: 81 [35%]) (Figure 2, Table 3). Most preterm infants (135/148 [91%]) were born at 22–33 weeks’ gestation. A lumbar puncture was performed within 7 days after birth for 148/228 (65%) infants; term infants were more frequently assessed by lumbar puncture than preterm infants (66/81 [81%] vs. 82/147 [56%], p<0.001; information missing for 1 infant). Bacterial pathogens were isolated from blood for 219/229 (98%) infants; only 5/229 (2%) were diagnosed by growth from CSF alone. E. coli was the most frequently isolated organism overall (84/222 [38%] single pathogen infections) and the most frequently isolated organism among preterm infants (75/144 [52%] single pathogen infections). GBS was the most commonly isolated bacterial pathogen among term infants (47/78 [60%] single pathogen infections). Consistent with GBS prevention guidelines, a CBC was performed for a majority of infants within 6 hours of birth (191/225 [85%]; information missing for 4) and most infants received antibiotic therapy within 6 hours (191/219 [87%]; information missing for 10). However, a CBC was more commonly performed for preterm than for term infants (141/146 [97%] vs. 50/79 [63%], p<0.001), and a larger proportion of preterm infants received antibiotic therapy within 6 hours of birth (130/140 [93%] vs. 61/79 [77%], p<0.001). While 80/81 [99%] term infants survived to discharge, transfer, or 120 days, only 102/148 [69%] preterm infants survived to status (p<0.001). Median length of hospital stay among survivors was 59 days longer for preterm infants (p<0.001). Cause of death was recorded for 46 of 47 infants who died. Death was infection-related for 34/46 (74%), including a term infant who died less than 9 hours after birth with an invasive E. coli infection.

Table 3.

Characteristics of infants with culture-confirmed early-onset infections born to women with chorioamnionitis 2006–2009, overall and by gestational age.

| Characteristic1/ | All infants N=229 |

Gestational Age | P-value2/ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preterm (22–36 weeks) N=148 |

Term (≥37 weeks) N=81 |

|||

| Newborn | ||||

| Race, n (%) | 0.75 | |||

| Black | 86 (38) | 53 (37) | 33 (41) | |

| White | 127 (57) | 82 (57) | 45 (56) | |

| Other | 11 (5) | 8 (6) | 3 (4) | |

| Hispanic ethnicity, n (%) | 72 (34) | 39 (29) | 33 (42) | 0.07 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.58 | |||

| Male | 119 (52) | 79 (53) | 40 (49) | |

| Female | 110 (48) | 69 (47) | 41 (51) | |

| Mode of delivery, n (%) | 1.0 | |||

| Cesarean | 145 (63) | 94 (64) | 51 (63) | |

| Vaginal | 84 (37) | 54 (36) | 30 (37) | |

| Birth weight (g), n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| 401–1500 | 116 (51) | 116 (78) | 0 (0) | |

| 1501–2500 | 32 (14) | 28 (19) | 4 (5) | |

| >2500 | 81 (35) | 4 (3) | 77 (95) | |

| Site of positive culture, n (%)3/ | 0.40 | |||

| Blood only | 219 (96) | 142 (96) | 77 (95) | |

| CSF only | 5 (2) | 2 (1) | 3 (4) | |

| Blood and CSF | 5 (2) | 4 (3) | 1 (1) | |

| Pathogen isolated, n (%)4/ | <0.001 | |||

| Group B Streptococcus (GBS) | 78 (35) | 31 (22) | 47 (60) | |

| E. coli | 84 (38) | 75 (52) | 9 (12) | |

| Other Gram positive | 34 (15) | 15 (10) | 19 (24) | |

| Other Gram negative | 24 (11) | 21 (15) | 3 (4) | |

| Candida spp. | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Timing of antibiotics, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Received at birth (≤ 6 h) | 191 (87) | 130 (93) | 61 (77) | |

| Received after birth (>6 h) | 23 (11) | 6 (4) | 17 (22) | |

| Died before treatment | 5 (2) | 4 (3) | 1 (1) | |

| CBC performed at birth (≤ 6 h) | 191 (85) | 141 (97) | 50 (63) | <0.001 |

| Outcome, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Survival to discharge/transfer/120 days | 182 (79) | 102 (69) | 80 (99) | |

| Death | 47 (21) | 46 (31) | 1 (1) | |

| Length of stay among survivors, days, median (range) | 22 (2–157) | 69 (7–157) | 10 (2–44) | <0.001 |

Information was missing for: race (n=5), Hispanic (n=17), timing of initial antibiotics (n=10), CBC performed at birth (n=4).

P-value for a test of whether the characteristic differed by gestational age by Fisher’s exact test (categorical variables) or the Kruskal-Wallis test (length of stay).

Organisms isolated from CSF only were: GBS (1), Staphylococcus aureus (1), alpha streptococci (1), viridans group streptococci (1), and Enterococcus spp. (1). The same organism was isolated from blood and CSF in 5 infants: GBS (1), E. coli (4).

Pathogens for infants with the following polymicrobial infections found on blood culture are not shown (n=7): GBS + E. coli (2); Serratia + Enterococcus (1); Neisseria + Haemophilus (1); Neisseria + viridans group streptococci (1); klebsiella + candida albicans (1); Enterococcus + coagulase-negative staphylococci (1).

Timing of Signs and Symptoms of Early-onset Infection

Signs or symptoms of sepsis were documented within 6 hours of birth for 200 (87%) of the 229 chorioamnionitis-exposed infants. No infants were considered symptomatic solely on the basis of CBC findings (i.e., neutropenia or thrombocytopenia). All infants who died were symptomatic within 6 hours of birth. No signs or symptoms of sepsis were documented within 6 hours of birth for 29 (13%) infants, although 8/29 (28%) developed signs or symptoms of sepsis within 72 hours after birth (Figure 2). Selected characteristics of the 29 initially asymptomatic infants are depicted in Table 4. While 23/29 (79%) were born at term, only 58/200 (29%) symptomatic infants were born at term (p<0.001). Placental pathology was performed less often for deliveries of infants who were asymptomatic within 6 hours of birth compared to infants who were initially symptomatic (18/28 [64%] vs. 182/200 [91%], p<0.001; information missing for 1). Correspondingly, clinical diagnoses of chorioamnionitis without histologic confirmation were more common among the initially asymptomatic infants than among the initially symptomatic infants (12/29 [41%] vs. 30/200 [15%], p=0.002). GBS was the most common pathogen among initially asymptomatic infants (18/29 [62%]), while E. coli was the most common pathogen among symptomatic infants (83/193 [43%] single pathogen infections).

Table 4.

Characteristics of initially asymptomatic (≤6 hours of life) infants with early-onset infection born to women with chorioamnionitis.

| Chorioamnionitis diagnostic criteria | Exposure to any IAP? | Gestational age (weeks) | Pathogen isolated from blood (except as noted) | Symptomatic within 72 hours of birth? | Antibiotic therapy initiated within 8 hours of culture? | Blood culture obtained for chorioamnionitis evaluation? | Number of days antibiotic treatment received |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical only | No | 38 | GBS | No | No | Yes | 7 |

| Clinical only | Yes | 40 | GBS | No | Yes | Yes | 6 |

| Clinical only | Yes | 38 | GBS | No | Yes | Yes | 11 |

| Histologic and Clinical | Yes | 40 | GBS | No | Yes | Yes | 8 |

| Clinical only | No | 37 | GBS | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8 |

| Histologic and Clinical | Yes | 42 | GBS | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8 |

| Histologic and Clinical | Yes | 39 | GBS | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| Clinical only | Yes | 40 | GBS | No | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| Histologic and Clinical | Yes | 40 | GBS | No | Yes | Yes | 8 |

| Clinical only | Yes | 38 | GBS | No | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| Clinical only | Yes | 40 | GBS | No | Yes | Yes | 8 |

| Histologic and Clinical | Yes | 41 | GBS | No | Yes | Yes | 8 |

| Histologic and Clinical | Yes | 40 | GBS | No | Yes | No | 15 |

| Clinical only | Yes | 40 | GBS | No | Unknown | Yes | 8 |

| Clinical only | Yes | 40 | GBS | Yes | Yes | Yes | 11 |

| Clinical only | Yes | 40 | Enterococcus faecalis | No | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| Histologic and Clinical | No | 41 | Enterococcus faecalis | No | No | Yes | 15 |

| Clinical only | Yes | 39 | Bacillus sp. | No | No | Yes | 8 |

| Histologic only | No | 39 | Streptococcus mitis | Yes | Yes | No | 8 |

| Histologic and Clinical | Yes | 40 | Haemophilus influenzae | No | No | No | 22 |

| Histologic and Clinical | No | 39 | Group D Streptococcus | No | Yes | Yes | 4 |

| Clinical only | Yes | 40 | Viridans streptococci (CSF) | No | Yes | Yes | 15 |

| Histologic and Clinical | Yes | 40 | Staphylococcus aureus | No | No | Yes | 7 |

| Histologic and Clinical | Yes | 36 | E. coli | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| Histologic and Clinical | Yes | 36 | GBS | No | No | Yes | 12 |

| Histologic only | Yes | 33 | GBS | No | No | No | 11 |

| Histologic only | Yes | 36 | GBS | No | Yes | No | 14 |

| Histologic only | No | 36 | Streptococcus pneumoniae | Yes | No | No | 13 |

| Histologic only | No | 31 | Viridans streptococci | Yes | Yes | Not known | 10 |

The proportion of initially asymptomatic infants whose mothers received intrapartum antibiotics was not significantly different than the proportion for symptomatic infants (22/29 [76%] vs. 137/200 [69%], p=0.52). However, the proportions of asymptomatic and symptomatic term infants whose mothers received intrapartum antibiotics differed (18/23 [78%] vs. 30/58 [52%], p=0.04). A CBC was obtained for a smaller proportion of asymptomatic than symptomatic infants (12/29 [41%] vs. 179/196 [91%], p<0.001) and fewer asymptomatic infants received antibiotics within 6 hours of birth (17/28 [61%] vs. 173/191 [91%], p<0.001). Whether born preterm or at term a smaller proportion of asymptomatic infants had a CBC performed (preterm: 5/6 [83%] vs. 136/140 [97%], p=0.19; term: 7/23 [30%] vs. 43/56 [77%], p<0.001) or received antibiotics within 6 hours of birth (preterm: 3/6 [50%] vs. 127/134 [95%], p=0.005; term: 15/23 [65%] vs. 46/56 [82%], p=0.14). None of the initially asymptomatic infants received mechanical ventilation, compared with 140/200 (70%) symptomatic infants.

Delivery at <37 weeks’ gestation (p<0.001), rupture of membranes ≥18 hours (p=0.04), and uterine or abdominal tenderness (p=0.03) were more commonly documented for mothers of infants who were symptomatic than for mothers whose infants were initially asymptomatic (Table 5). In contrast, intrapartum fever (p=0.01) and fever in the 72 hours prior to delivery (p<0.001) were more common for women with chorioamnionitis whose infants were initially asymptomatic.

Table 5.

Maternal risk factors for early-onset GBS sepsis at the time of delivery and maternal clinical signs within 72 hours prior to delivery for infants with invasive early-onset infection born to women with chorioamnionitis 2006–2009.

| Maternal risk factor at delivery or clinical sign within 72 h prior to delivery1/ | Overall n (%) |

Infant status at birth (≤ 6 h) | P-value2/ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptomatic n (%) |

Asymptomatic n (%) |

|||

| All cases | N=229 | N=200 | N=29 | |

| Previous infant with GBS disease | 0 | 0 | ||

| GBS bacteriuria during current pregnancy | 10 (4) | 10 (5) | 0 (0) | 0.62 |

| Intrapartum fever3/ | 79 (35) | 63 (32) | 16 (57) | 0.01 |

| Delivery < 37 weeks | 148 (65) | 142 (71) | 6 (21) | <0.001 |

| Rupture of membranes ≥ 18 hours | 100 (44) | 93 (47) | 7 (25) | 0.04 |

| At least 1 risk factor above | 202 (89) | 180 (90) | 22 (79) | 0.10 |

| Maternal fever4/ | 87 (38) | 67 (34) | 20 (69) | <0.001 |

| Uterine or abdominal tenderness | 52 (23) | 50 (25) | 2 (7) | 0.03 |

| Foul smelling discharge or amniotic fluid | 35 (15) | 33 (17) | 2 (7) | 0.27 |

| Maternal tachycardia (>100 beats per minute) | 96 (42) | 83 (42) | 13 (45) | 0.84 |

| At least 1 symptom above | 162 (71) | 137 (69) | 25 (86) | 0.05 |

| Maternal fever only | 30 (13) | 21 (11) | 9 (31) | 0.006 |

| Clinical chorioamnionitis5/ | N=152 | N=128 | N=24 | |

| Previous infant with GBS disease | 0 | 0 | ||

| GBS bacteriuria during current pregnancy | 7 (5) | 7 (5) | 0 (0) | 0.60 |

| Intrapartum fever | 74 (49) | 58 (45) | 16 (70) | 0.04 |

| Delivery < 37 weeks | 93 (62) | 91 (71) | 2 (9) | <0.001 |

| Rupture of membranes ≥ 18 hours | 70 (46) | 65 (51) | 5 (22) | 0.01 |

| At least 1 risk factor above | 140 (93) | 123 (96) | 17 (74) | 0.002 |

| Maternal fever | 80 (53) | 60 (47) | 20 (83) | 0.001 |

| Uterine or abdominal tenderness | 49 (32) | 47 (37) | 2 (8) | 0.008 |

| Foul smelling discharge or amniotic fluid | 32 (21) | 30 (23) | 2 (8) | 0.11 |

| Maternal tachycardia (>100 beats per minute) | 75 (49) | 64 (50) | 11 (46) | 0.82 |

| At least 1 symptom above | 134 (88) | 111 (87) | 23 (96) | 0.31 |

| Maternal fever only | 27 (18) | 18 (14) | 9 (38) | 0.02 |

| Histologic chorioamnionitis only6/ | N=77 | N=72 | N=5 | |

| Previous infant with GBS disease | 0 | 0 | ||

| GBS bacteriuria during current pregnancy | 3 (4) | 3 (4) | 0 (0) | 1.0 |

| Intrapartum fever | 5 (6) | 5 (7) | 0 (0) | 1.0 |

| Delivery < 37 weeks | 55 (71) | 51 (71) | 4 (80) | 1.0 |

| Rupture of membranes ≥ 18 hours | 30 (39) | 28 (39) | 2 (40) | 1.0 |

| At least 1 risk factor above | 62 (81) | 57 (79) | 5 (100) | 0.58 |

| Maternal fever | 7 (9) | 7 (10) | 0 (0) | 1.0 |

| Uterine or abdominal tenderness | 3 (4) | 3 (4) | 0 (0) | 1.0 |

| Foul smelling discharge or amniotic fluid | 3 (4) | 3 (4) | 0 (0) | 1.0 |

| Maternal tachycardia (>100 beats per minute) | 21 (27) | 19 (26) | 2 (40) | 0.61 |

| At least 1 symptom above | 28 (36) | 26 (36) | 2 (40) | 1.0 |

| Maternal fever only | 3 (4) | 3 (4) | 0 (0) | 1.0 |

All maternal risk factor information was missing for one infant who was asymptomatic within 6 hours of birth and whose mother had clinical chorioamnionitis. Maternal temperature within 72 hours prior to delivery was missing for one infant who was symptomatic within 6 hours of birth and whose mother had clinical chorioamnionitis.

Statistical significance for a difference between the percent in symptomatic versus asymptomatic infants by Fisher’s exact test.

Maternal intrapartum fever was defined as a temperature≥100.4 F/38.0 C after onset of labor leading to delivery.

Maternal fever was defined as any temperature≥100.4 F/38.0 C in the 72 hours prior to delivery without regard to onset of labor.

Chorioamnionitis documented in the mother’s medical record, with or without histologic findings from placental pathology.

Histologic chorioamnionitis documented from placental pathology without documentation of chorioamnionitis in the mother’s medical record.

Number of Infants Treated for Each Well-Appearing Infant with Early-onset Infection

The total birth cohort may have included between 1,983 and 39,659 infants whose mothers had chorioamnionitis depending on chorioamnionitis prevalence (Table 6). Assuming complete implementation of current guidelines for prevention of GBS, we estimated that 60–1400 well-appearing newborns born to mothers with chorioamnionitis might undergo diagnostic evaluation and receive empiric antibiotics for each initially asymptomatic infant with culture-confirmed early-onset infection. Estimates calculated for term and preterm infants separately were even higher (Table 6).

Table 6.

Estimated number of well-appearing infants born to women with chorioamnionitis potentially treated for each initially asymptomatic infant with culture-confirmed early-onset infection

| Number of live births1/ | Estimated chorioamnionitis prevalence | Estimated number of infants whose mothers had chorioamnionitis | Estimated number of chorioamnionitis-exposed infants without symptoms of early-onset infection at birth2/ | Estimated number of well-appearing chorioamnionitis-exposed infants evaluated and treated for each initially asymptomatic infant with early-onset infection3/ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | ||||

| 396,586 | 0.5% | 1,983 | 1,783 | 60 |

| 1% | 3,966 | 3,766 | 130 | |

| 3% | 11,898 | 11,698 | 400 | |

| 10% | 39,659 | 39,459 | 1,400 | |

| Term | ||||

| 348,996 | 0.5% | 1,745 | 1,687 | 70 |

| 1% | 3,490 | 3,432 | 150 | |

| 3% | 10,470 | 10,412 | 450 | |

| 10% | 34,900 | 34,842 | 1,500 | |

| Preterm | ||||

| 47,590 | 6% | 2,856 | 2,714 | 450 |

| 20% | 9,518 | 9,376 | 1600 | |

| 40% | 19,036 | 18,894 | 3100 | |

| 70% | 33,313 | 33,171 | 5500 |

For these calculations, we assumed 88% of births were term and 12% were preterm.

The number of infants with culture-confirmed early-onset infections in the cohort who were symptomatic within 6 hours of birth were subtracted from the total estimated number of infants born to mothers with chorioamnionitis. Thus overall estimates exclude 200 symptomatic infants with culture-confirmed early-onset infections, estimates for term infants exclude 58 symptomatic term infants, and estimates for preterm infants exclude 142 symptomatic preterm infants. The totals are likely to overestimate the number of asymptomatic chorioamnionitis-exposed infants in the cohort, as we had no data for infants who may have had symptoms but negative cultures.

Estimates were derived as the number of infants without symptoms of early-onset infection within 6 hours of birth (previous column) divided by the number of initially asymptomatic infants with culture-confirmed early-onset infections in the cohort, namely: 29 infants overall, 23 term infants, and 6 preterm infants. Estimates were rounded to 1 significant digit (if under 100) or 2 significant digits.

Discussion

In this cohort, while the majority of infants with culture-confirmed early-onset infection born to women with chorioamnionitis displayed signs and/or symptoms of infection within 6 hours of birth, 29/229 (13%) were initially asymptomatic and 21 (9%) remained asymptomatic during the first 72 hours after birth. The majority of these initially asymptomatic infants were born at term gestation, and GBS was the most common pathogen isolated. Perhaps because most initially asymptomatic infants were born at term, they were less likely than symptomatic infants to receive empiric antibiotics or be evaluated with a CBC, as recommended by CDC guidelines for prevention of GBS disease. Nonetheless, no deaths occurred among initially asymptomatic infants.

E. coli was the most common etiology of early-onset infection among all infants born to mothers with chorioamnionitis. This is likely because infants born to mothers with chorioamnionitis were more often preterm and E. coli infections are strongly associated with birth at <34 weeks gestational age.1,2 Preterm infants often have non-specific signs and symptoms consistent with both sepsis and prematurity.21 Even in the absence of chorioamnionitis, the risk of early-onset infections among preterm infants is much higher than among term infants.1 Therefore, although our estimates of the number of asymptomatic preterm infants treated for each infant with early-onset infection are high, diagnostic evaluations and empiric treatment for these asymptomatic infants may be justified in the context of the higher risk conferred by prematurity alone. While many clinicians perform diagnostic evaluations and initiate empiric antibiotic therapy for preterm infants, the optimal management of term, asymptomatic chorioamnionitis-exposed infants is more controversial.

Despite the tremendous impact of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis to reduce vertical transmission of GBS from colonized at risk mothers, GBS remains the leading infectious cause of neonatal morbidity and mortality.1,2 Although the risk of neonatal GBS disease increases with preterm delivery, the majority of infants with early-onset GBS are delivered at term, because most babies are born at term. Perhaps because the mothers of most infants in the study had risk factors for early-onset GBS, a majority received intrapartum antibiotics. In the context of chorioamnionitis, it is possible that routine IAP masks the presence of infection in neonates born to women who received antibiotics. This may explain our finding that a higher proportion of initially asymptomatic term infants had mothers who received intrapartum antibiotics compared with symptomatic term infants. This may also explain our observation that maternal fever and intrapartum fever (both indications for intrapartum antibiotics) were more common among deliveries of asymptomatic infants. Nonetheless, the findings that 29/229 (13%) infected infants born to women with chorioamnionitis were asymptomatic within 6 hours of birth and 18/29 (62%) of these infants were infected with GBS suggest that current recommendations regarding evaluation and empiric antibiotic therapy for well-appearing infants born to mothers with chorioamnionitis may result in earlier diagnosis and treatment of early-onset infections. However, implementation of these guidelines may result in diagnostic testing and empiric antibiotics for a substantial number of healthy, uninfected chorioamnionitis-exposed infants. The precise ratio of well-appearing chorioamnionitis-exposed infants potentially evaluated and treated for each initially asymptomatic infant with early-onset infection varies widely depending on the prevalence of chorioamnionitis. Further prospective characterization of population-level chorioamnionitis prevalence rates may inform future guideline development.

This study has limitations. We had data only for infants with culture-confirmed early-onset infections. We were therefore unable to determine the prevalence of maternal chorioamnionitis in the cohort and have no information on the number of chorioamnionitis-exposed infants with negative cultures who may have been well-appearing or symptomatic at birth. To make our classification of infants with culture-confirmed early-onset infections as sensitive as possible, we considered infants with any non-specific clinical finding associated with sepsis to be symptomatic. The extent to which these factors contributed to an over or underestimate of the proportion of chorioamnionitis-exposed infants in the cohort who were asymptomatic within 6 hours of birth is unknown. With case data only, we were unable to assess whether empiric therapy given to chorioamnionitis-exposed well-appearing infants reduces the risk of severe disease compared to a “wait and see” approach. By including infants in our review whose mothers had a diagnosis of chorioamnionitis in the medical record without documentation of specific clinical signs (e.g., fever, uterine tenderness), we may have included some infants who were not exposed to chorioamnionitis. Nonetheless, chorioamnionitis is a clinical diagnosis often based on non-specific signs; therefore, obstetric providers’ diagnoses guide neonatal management. Inclusion of these infants was important for estimating the number of asymptomatic infants treated for each infant with early-onset infection. Further, we relied solely on retrospective data abstracted from the medical records during 2013 for information about clinical presentations during 2006–2009. Therefore, our findings should be considered along with changes in neonatal care practices that have occurred during the interim period. Additionally, real-time discussions with providers may have informed verification that infants were asymptomatic and determinations of whether unusual organisms represented contaminants. Nonetheless, pathogens typically associated with neonatal sepsis were isolated from the majority of infants, including those who were initially asymptomatic, giving us confidence in our retrospective assessment.

The majority (60%) of infants with early-onset infections identified in the multicenter parent study were born to women with chorioamnionitis. We found that a significant proportion (13%) of these chorioamnionitis-exposed infants were initially asymptomatic. Even with widespread IAP use and declining early-onset GBS infection rates, efforts to evaluate and provide empiric treatment for initially well-appearing infants whose mothers had chorioamnionitis may result in timely early-onset infection diagnoses and prompt therapy for affected infants. However, substantial numbers of asymptomatic infants born to women with chorioamnionitis would potentially require treatment under the current guidelines. Our findings should prompt further investigation into chorioamnionitis prevalence rates in order to better quantify numbers needed to treat so that the benefit of early diagnosis can be more precisely considered along with hazards of empiric antibiotic use in unaffected, term infants.

What is Known on This Subject

CDC Guidelines for Prevention of Perinatal Group B Streptococcal Disease recommend a diagnostic evaluation and empiric antibiotic therapy for well-appearing infants born to mothers with chorioamnionitis. Some clinicians question this approach for term infants who are asymptomatic at birth.

What This Study Adds

This study documents that some chorioamnionitis-exposed newborns with culture-confirmed early-onset neonatal sepsis may be asymptomatic at birth or throughout the first 72 hours of age. However, current recommendations require treating large numbers of asymptomatic infants for each case identified.

Acknowledgments

The National Institutes of Health, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the National Center for Research Resources provided grant support for the Neonatal Research Network’s Early Onset Sepsis Study through cooperative agreements and an interagency agreement. While NICHD and CDC staff did have input into the study design, conduct, analysis, and manuscript drafting, the content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Participating NRN sites collected data and transmitted it to RTI International, the data coordinating center (DCC) for the network, which stored, managed and analyzed the data for this study. One behalf of the NRN, Dr. Abhik Das (DCC Principal Investigator) and Ms. Nellie I. Hansen (DCC Statistician) had full access to all of the data in the study, and with the NRN Center Principal Investigators, take responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

We are indebted to our medical and nursing colleagues and the infants and their parents who agreed to take part in this study. The following investigators, in addition to those listed as authors, participated in this study:

NRN Steering Committee Chairs: Michael S. Caplan, MD, University of Chicago, Pritzker School of Medicine (2006–2011).

Alpert Medical School of Brown University and Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island (U10 HD27904) – Abbot R. Laptook, MD; Angelita M. Hensman, MS RNC-NIC BSN; William Oh, MD.

Case Western Reserve University, Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital (U10 HD21364, M01 RR80) – Michele C. Walsh, MD MS; Avroy A. Fanaroff, MD; Nancy S. Newman, RN.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (IAA 05FED32885-00)

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, University of Cincinnati Medical Center, and Good Samaritan Hospital (U10 HD27853, M01 RR8084) – Kurt Schibler, MD; Edward F. Donovan, MD; Cathy Grisby, BSN CCRC; Barbara Alexander, RN; Kate Bridges, MD; Jody Hessling, RN; Holly L. Mincey, RN BSN.

Duke University School of Medicine, University Hospital, and Duke Regional Hospital (U10 HD40492, UL1 TR1117, M01 RR30) –C. Michael Cotten, MD MHS; Kimberley A. Fisher, PhD FNP-BC IBCLC; Kathy J. Auten, MSHS; Katherine A. Foy, RN; Sandra Grimes, RN BSN.

Emory University, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, Grady Memorial Hospital, and Emory University Hospital Midtown (U10 HD27851, M01 RR39) – David P. Carlton, MD; Yvonne C. Loggins, RN BSN.

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development – Stephanie Wilson Archer, MA.

Indiana University, University Hospital, Methodist Hospital, Riley Hospital for Children at Indiana University Health, and Eskenazi Health (U10 HD27856, M01 RR750) – Leslie Dawn Wilson, BSN CCRC; Dianne E. Herron, RN; Lucy C. Miller, RN BSN CCRC.

RTI International (U10 HD36790) –W. Kenneth Poole, PhD (deceased); Kristin M. Zaterka-Baxter, RN BSN CCRP; Margaret Crawford, BS CCRP; Jeanette O’Donnell Auman, BS; Carolyn M. Petrie Huitema, MS CCRP.

Stanford University, Dominican Hospital, El Camino Hospital, and Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital (U10 HD27880, M01 RR70) – David K. Stevenson, MD; M. Bethany Ball, BS CCRC; Marian M. Adams, MD; Magdy Ismail, MD MPH; Andrew W. Palmquist, RN BSN; Melinda S. Proud, RCP.

Tufts Medical Center, Floating Hospital for Children (U10 HD53119, M01 RR54) – Brenda L. MacKinnon, RNC; Ellen Nylen, RN BSN.

University of Alabama at Birmingham Health System and Children’s Hospital of Alabama (U10 HD34216, M01 RR32) – Waldemar A. Carlo, MD; Namasivayam Ambalavanan, MD; Monica V. Collins, RN BSN MaEd; Shirley S. Cosby, RN BSN.

University of Iowa (U10 HD53109, M01 RR59) – Edward F. Bell, MD; John A. Widness, MD; Karen J. Johnson, RN BSN.

University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center (U10 HD53089, M01 RR997) – Kristi L. Watterberg, MD; Conra Backstrom Lacy, RN; Rebecca A. Montman, BSN RNC.

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, Parkland Health & Hospital System, and Children’s Medical Center Dallas (U10 HD40689, M01 RR633) – Charles R. Rosenfeld, MD; Luc P. Brion, MD; Walid A. Salhab, MD; Alicia Guzman; Gaynelle Hensley, RN; Melissa H. Leps, RN; Nancy A. Miller, RN; Diane M. Vasil, RNC-NIC.

University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston Medical School and Children’s Memorial Hermann Hospital (U10 HD21373) – Kathleen A. Kennedy, MD MPH; Jon E. Tyson, MD MPH; Julie Arldt-McAlister, RN BSN Georgia E. McDavid, RN; Sharon L. Wright, MT (ASCP).

University of Utah Medical Center, Intermountain Medical Center, LDS Hospital, and Primary Children’s Medical Center (U10 HD53124, M01 RR64) – Bradley A. Yoder, MD; Karen A. Osborne, RN BSN CCRC; Karie Bird, RN BSN; Jennifer J. Jensen, RN BSN; Cynthia Spencer, RNC; Kimberlee Weaver-Lewis, RN BSN.

Wayne State University, University of Michigan, Hutzel Women’s Hospital, and Children’s Hospital of Michigan (U10 HD21385) – Seetha Shankaran, MD; Rebecca Bara, RN BSN; Mary E. Johnson, RN BSN; Elizabeth Billian, RN MBA.

Yale University, Yale-New Haven Children’s Hospital, and Bridgeport Hospital (U10 HD27871, M01 RR125, UL1 TR142) – Richard A. Ehrenkranz, MD; Harris C. Jacobs, MD; Monica Konstantino, RN BSN; Patricia Cervone, RN; JoAnn Poulsen, RN; Janet Taft, RN BSN.

Funding Source: This study was supported by funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Abbreviations

- IAP

intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis

- GBS

group B Streptococcus

- CBC

complete blood count

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid.

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest: The authors have indicated they have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Financial Disclosure: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Contributors Statement Page

Drs. Wortham, Stoll, Schrag, and Ms. Hansen conceptualized and designed the study, drafted the initial manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Drs. Van Meurs, Sánchez, Faix, Poindexter, Goldberg, Bizzarro, Frantz, Das, Higgins, Cantey, and Ms. Hale coordinated and supervised data collection at the sites, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Drs. Benitz and Shane participated in the study design, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final version as submitted.

References

- 1.Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Sanchez PJ, et al. Early onset neonatal sepsis: the burden of group B Streptococcal and E. coli disease continues. Pediatrics. 2011 May;127(5):817–826. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weston EJ, Pondo T, Lewis MM, et al. The burden of invasive early-onset neonatal sepsis in the United States, 2005–2008. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011 Nov;30(11):937–941. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318223bad2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schuchat A, Deaver-Robinson K, Plikaytis BD, Zangwill KM, Mohle-Boetani J, Wenger JD. Multistate case-control study of maternal risk factors for neonatal group B streptococcal disease. The Active Surveillance Study Group. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1994 Jul;13(7):623–629. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199407000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schuchat A. Neonatal group B streptococcal disease–screening and prevention. NEJM. 2000 Jul 20;343(3):209–210. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007203430310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verani JR, McGee L, Schrag SJ. Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease–revised guidelines from CDC, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. Nov 19;59(RR-10):1–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berardi A, Lugli L, Rossi C, et al. Intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis failure and group-B streptococcus early-onset disease. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011 Oct;24(10):1221–1224. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2011.552652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Velaphi S, Siegel JD, Wendel GD, Jr, Cushion N, Eid WM, Sanchez PJ. Early-onset group B streptococcal infection after a combined maternal and neonatal group B streptococcal chemoprophylaxis strategy. Pediatrics. 2003 Mar;111(3):541–547. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.3.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin FY, Brenner RA, Johnson YR, et al. The effectiveness of risk-based intrapartum chemoprophylaxis for the prevention of early-onset neonatal group B streptococcal disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001 May;184(6):1204–1210. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.113875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verani JR, Schrag SJ. Group B streptococcal disease in infants: progress in prevention and continued challenges. Clin Perinatol. Jun;37(2):375–392. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tudela CM, Stewart RD, Roberts SW, et al. Intrapartum evidence of early-onset group B streptococcus. Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Mar;119(3):626–629. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31824532f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Polin RA, Committee on F, Newborn Management of neonates with suspected or proven early-onset bacterial sepsis. Pediatrics. 2012 May;129(5):1006–1015. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schuchat A, Wenger JD. Epidemiology of group B streptococcal disease. Risk factors, prevention strategies, and vaccine development. Epidemiol Rev. 1994;16(2):374–402. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schuchat A, Zywicki SS, Dinsmoor MJ, et al. Risk factors and opportunities for prevention of early-onset neonatal sepsis: a multicenter case-control study. Pediatrics. 2000 Jan;105(1 Pt 1):21–26. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benitz WE, Wynn JL, Polin RA. Reappraisal of Guidelines for Management of neonates with suspected early-onset sepsis. J Pediatr. 2015 Apr;166(4):1070–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.12.023. Epub 2015 Jan 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark RH, Bloom BT, Spitzer AR, Gerstmann DR. Empiric use of ampicillin and cefotaxime, compared with ampicillin and gentamicin, for neonates at risk for sepsis is associated with an increased risk of neonatal death. Pediatrics. 2006 Jan;117(1):67–74. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cotten CM, Taylor S, Stoll B, et al. Prolonged duration of initial empirical antibiotic treatment is associated with increased rates of necrotizing enterocolitis and death for extremely low birth weight infants. Pediatrics. 2009 Jan;123(1):58–66. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cacho N, Neu J. Manipulation of the intestinal microbiome in newborn infants. Adv Nutr. 2014 Jan 1;5(1):114–8. doi: 10.3945/an.113.004820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elimian A, Verma U, Beneck D, Cipriano R, Visintainer P, Tejani N. Histologic chorioamnionitis, antenatal steroids, and perinatal outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2000 Sep;96(3):333–336. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)00928-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koh KS, Chan FH, Monfared AH, Ledger WJ, Paul RH. The changing perinatal and maternal outcome in chorioamnionitis. Obstet Gynecol. 1979 Jun;53(6):730–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Dyke MK, Phares CR, Lynfield R, et al. Evaluation of universal antenatal screening for group B streptococcus. NEJM. 2009 Jun 18;360(25):2626–2636. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0806820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bekhof J, Reitsma JB, Kok JK, et al. Clinical signs to identify late-onset sepsis in preterm infants. Eur J Pediatr. 2013 Apr;172(4):501–8. doi: 10.1007/s00431-012-1910-6. Epub 2012 Dec 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]