Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To examine whether weight history and weight transitions over adult lifespan contribute to physical impairment among postmenopausal women.

DESIGN

Body mass index (BMI; kg/m2) categories were calculated among postmenopausal women who reported their weight and height at age 18. Multiple-variable logistic regression was used to determine the association between BMI at age 18 and BMI transitions over adulthood on severe physical impairment (SPI), defined as scoring < 60 on the Physical Functioning Subscale of the Random 36-Item Healthy Survey.

SETTING

Participants were part of the Women's Health Initiative Observational study (WHI OS), where participants’ health were followed over time via questionnaires and clinical assessments.

SUBJECTS

Postmenopausal women (n=76,016; 63.5 ± 7.3 years)

RESULTS

Women with overweight (BMI=25.0-29.9) or obesity (BMI≥30) at 18 years had greater odds of SPI [odds ratio (OR) = 1.51, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.35-1.69 and 2.14, 95% CI: 1.72-2.65, respectively] than normal weight (BMI=18.5-24.9) counterparts. Transitions from normal weight to overweight/obese or to underweight (BMI <18.5) were associated with greater odds of SPI (1.97 [1.84-2.11] and 1.35 [1.06-1.71], respectively) compared to weight stability. Shifting from underweight to overweight/obese also had increased odds of SPI (1.52 [1.11-2.09]). Overweight/obese to normal BMI transitions resulted in a reduced SPI odds (0.52 [0.39-0.71]).

CONCLUSIONS

Higher weight history and transitions into higher weight classes were associated with higher likelihood of severe physical impairment, while transitioning into lower weight classes for those with overweight/obesity was protective among postmenopausal women.

Keywords: Body weight, weight change, body mass index, physical impairment, physical function, disability

INTRODUCTION

Excess weight is prevalent among older adults in the United States, where over 70% of adults 60 years of age and older are classified as overweight (Body mass index [BMI]=25.0-29.9kg/m2) or obese (BMI≥30kg/m2)1. This is an important public health issue because obesity has been shown to increase the risk of morbidity, mortality, and reduced quality of life in adults2,3. Specifically, older adults with overweight or obesity have higher rates of physical impairments as a result of increased load on weight bearing joints4. Additionally, obesity-related metabolic dysfunction is known to impact the bioenergetic capacity of skeletal muscle that could indirectly contribute to physical impairment5-8. Evidence also links obesity to increases in comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease9, depression10, and diabetes11; all of which potentially limit physical function. The combination of these direct and indirect effects of obesity on increased rates of physical impairment in older adults is a major public health challenge that has a large impact on costs and quality of care on health systems.

Current studies have shown that body weight gradually increases over lifespan and then plateaus around age 60 years12,13. Emerging literature links early history of increased weight and weight changes across the life course with physical impairment later in life. A few studies have shown that individuals with overweight or obesity in middle age have greater difficulty performing activities of daily living (ADLs) later in life than their normal weight counterparts14-16. Another study reported weight gains leading to obesity over 20 years were associated with higher ADL disability17. Moreover, history of obesity in middle adulthood has been noted as a predictive marker of mobility disability18 and low muscle strength19 later in life. Weight history across the lifespan in women is particularly important because women live longer and experience greater rates of physical impairments for prolonged periods compared to men20,21. Additionally, initial evidence suggests that a history of obesity impacts health and physical capacity to a greater extent in women following menopause, suggesting this group is particularly vulnerable to physical impairment22. Lastly, while body weight seems to plateau after the age of 60, the prevalence of obesity among women in this age group has risen from 31.5% to 38.1% between 2003 and 20121. This finding raises the question to whether maintenance of normal weight throughout life is associated with better physical function later in life among postmenopausal women. Weight history and weight transitions over the lifespan, and the effects on later-life physical impairment could inform the development of novel prevention strategies and therapeutic interventions towards preserving functional independence among postmenopausal women.

To address this knowledge gap, the primary aim of the study was to evaluate the association between weight status at age 18 with severe physical impairment (SPI) in a prospective cohort of postmenopausal women. We hypothesized that higher BMI at age 18 years would be associated with higher likelihood of SPI in later life. The secondary aim of the study was to investigate the association between weight transitions during young adulthood and middle age and SPI later in life. We hypothesized that women who gained weight would have a higher likelihood of SPI later in life compared to women who maintained their weight. We also hypothesized that women who lost weight over time would be less likely to have SPI compared with women who remained normal weight.

METHODS

Study population

The Women's Health Initiative (WHI) Observational Study (OS) addresses major causes of morbidity and mortality and their risk factors in postmenopausal women. Details of this study have been reported elsewhere23. Briefly, a total of 161,808 eligible women aged 50 to 79 years old were involved with either a clinical trial or the OS. This analysis focused on OS participants (n=93,676), enrolled between 1994 and 1998. About 19% of the sample did not have self-reported weight/height history (n=5,448) or self-reported physical function (n=12,212) and were excluded from the analysis, resulting in an analytic sample of 76,016 postmenopausal women. Those who were excluded were younger, non-white, less educated, and reported less income. The protocol and consent forms were approved by the institutional review board at each site, and all participants provided written informed consent prior to participation.

Weight history

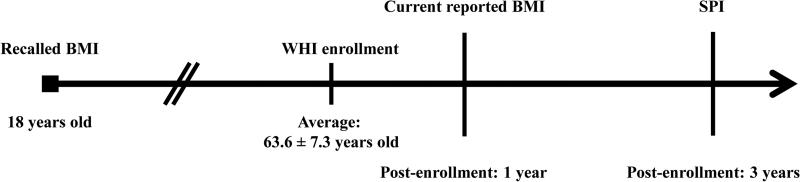

At baseline, participants reported their height and weight at age 18 years old. Weight transitions were calculated using weight measured at the first year of follow-up, which was self-reported by participants to maintain the same mode of measurement with the historical assessments (Figure 1). Body mass index (BMI; kg/m2) was calculated and categorized according to the World Health Organization (WHO) classifications: underweight (BMI<18.50 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5≤BMI<25.0 kg/m2), overweight (25.00≤BMI<30 kg/m2), and obese (BMI≥30 kg/m2). Adult lifespan BMI class change was calculated based on a shift in BMI class starting from age 18 years old to current weight at the first WHI follow-up visit. Overweight and obese BMI classes at age 18 years were collapsed due to a low number of obese women at youth and few women who transitioned to other BMI classes over time.

Figure 1.

Body mass index (BMI) and severe physical impairment (SPI) assessment timeline among Women's Health Initiative (WHI) participants.

Figure 1 depicts when measures used to calculate body mass index (BMI) and severe physical impairment (SPI) were collected.

Severe physical impairment (SPI)

Severe physical impairment was assessed using a physical function subscale of the Rand 36-Item Health survey (SF-36). The SF-36 was initially collected at the third year of follow-up. Participants were asked ten questions about engagement in daily activities. These questions evaluated limitations in vigorous activities (i.e., running, lifting heavy objects, or engaging in strenuous sports), moderate activities (i.e., moving a table, vacuuming, bowling or golfing, lifting or carrying groceries), lifting or carrying groceries, climbing several flights of stairs, climbing one flight of stairs, bending/kneeling/stooping, walking more than a mile, walking several blocks, walking one block, and bathing/dressing. Participants indicated whether they had no, little, or a lot of limitation for each question. Each question was scored 0 to 10, where no, little, or a lot of limitation garnered a score of 10, 5, and 0, respectively. A total summary score of 0 to 100 was calculated from the questions where a higher score indicated better physical function24. As an example, someone who reported a lot of limitation in climbing several flights of stairs, bending/kneeling/stooping, and walking more than a mile, while reporting a little limitation in all other categories would receive a score of 35. Severe physical impairment was calculated as a physical function (PF) score less than 6024,25.

Covariates for analysis

Covariates included demographic factors, lifestyle factors, medical history items, and current medications. Race/ethnicity was self-described as White (non-Hispanic), American Indian/Alaskan native, Asian/Pacific Islander, Black/African American, or Hispanic/Latina. Marital status was defined as never married, divorced/separated/widowed, or presently married/living as married. Education was defined as no education to high school diploma, education after high school, or college degree and higher. Income was stratified into five categories: less than $20,000; $20,000 to $34,999; $35,000 to $49,999; $50,000 to $74,999; or $75,000 and greater. Occupation was stratified into four roles: manager, administrative, service/labor, or homemaker. Living status was defined as currently living alone or not. Lifestyle factors included excessive alcohol consumption (defined as > 7 drinks per week), history of tobacco smoking, and health status (i.e., excellent, very good, good, fair or poor). Self-reported physical activity was derived as two covariates: participation of moderate and strenuous recreational physical activity (minutes/week) at WHI baseline and whether the participant engaged in strenuous physical activity between the ages of 15 to 19. Total energy intake was measured by daily kilocalories from the Food Frequency Questionnaire recalled over the past 3 months26.

Additionally, medical history items included as covariates were: menopause age; number of pregnancies lasting at least 6 months; depressive-like symptoms measured on the shortened Centers for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression (CES-D) scale ranging from 0 to 1 where higher scores indicated higher likelihood of depression; number of falls in the past year; history of coronary heart disease defined as having coronary revascularization, myocardial infarction, and angina; history of congestive heart failure; history of hypertension as never, currently untreated or currently treated; history of diabetes as ever been treated for diabetes with pills or shots; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease defined as either having emphysema, chronic bronchitis or asthma; history of stroke; history of thyroid gland problems; history of any type of cancer; history of arthritis; and history of any type of fracture. Cardiovascular, cancer, and stroke events were adjudicated locally and centrally during the WHI study. Current medications known to influence body weight were also included as they would theoretically influence the lifetime weight difference calculation. These included hormone therapy defined as using estrogen or progesterone from only pills and patches; oral use of glucocorticosteroids; contraceptives; psychotropic drugs (antipsychotics, antidepressants and mood stabilizers); beta-blockers; anticonvulsants; and antimigraine drugs.

Validity of self-reported body weight and height

We examined accuracy of self-reported body weight by comparing self-reported body weight by women aged 50 years old at the time of weight recall (for their weight at age 50) and clinically measured weight using calibrated scales in the clinic by certified staff (n=1,926 women). There was a high correlation (r = 0.91) between self-reported weight and measured weight. However, these women systematically under-reported their weight by an average of 1.89 ± 0.20 kg.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics were stratified by BMI (i.e., underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obese) at 18 years old. Groups were compared using chi-square analysis for categorical variables and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for age at menopause, a continuous variable verified to be normally distributed. Logistic regression models estimated the association of BMI at 18 years old and current SPI (odds ratios [OR] and 95% confidence intervals [CI]). Logistic regression models were also used to examine the likelihood of SPI for becoming underweight, normal weight, or overweight/obese at Year 1 of follow-up compared to maintaining weight from 18 years old. Models were constructed in four successive stages to evaluate the effect of the covariates. The first model adjusted for demographics, the second model adjusted for demographics with lifestyle factors, the third model adjusted for demographics, lifestyle factors and medical history items, and the final model adjusted for demographics, lifestyle factors, medical history items, and current medications. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 13 (STATA Corp., TX, USA).

RESULTS

Characteristics

Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1. Postmenopausal women reporting overweight or obesity at age 18 tended to be younger, African-American, non-Hispanic, not married, obtained less than a high school education, had low income, and lived alone. They were also more likely to report a history of tobacco smoking, poorer health status, being physically inactive, having higher energy intake, and being physically inactive between 15-19 years. Participants with overweight or obesity at age 18 were more likely to have a history of medical conditions such as thyroid disorder, coronary heart disease, congestive heart failure, stroke, diabetes, hypertension, arthritis, depressive-like symptoms, and tended not to have pregnancies lasting 6 months or more. They also tended to take more medications known to affect weight such as psychotropic drugs, beta blockers, and anticonvulsants.

Table 1.

Characteristics of postmenopausal women by body mass index (BMI) class at age 18 years enrolled in the Women's Health Initiative Observational study (n=76,016)

| Underweight at 18 (n=13,966) | Normal weight at 18 (n=58,016) | Overweight at 18 (n=3,338) | Obese at 18 (n=696) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline age | |||||

| - 50-59 yrs, n(%) | 2,835 (20.3) | 11,352 (19.6) | 744 (22.3) | 187 (26.8) | <0.001 |

| - 60-69 yrs, n(%) | 5,729 (41.0) | 24,557 (42.3) | 1,489 (44.6) | 314 (45.1) | |

| - 70-79 yrs, n(%) | 5,402 (38.7) | 22,107 (38.1) | 1,105 (33.1) | 195 (28.0) | |

| White, non-Hispanic, n(%) | 11,747 (84.1) | 51,370 (88.5) | 2,820 (84.5) | 581 (83.5) | <0.001 |

| Married, n(%) | 8,530 (61.1) | 35,534 (61.3) | 1,826 (54.7) | 321 (46.1) | <0.001 |

| Education, < high school, n(%) | 566 (4.1) | 2,159 (3.7) | 190 (5.7) | 56 (8.1) | <0.001 |

| Income, < $20,000, n(%) | 1,947 (13.9) | 7,405 (12.8) | 595 (17.8) | 169 (24.3) | <0.001 |

| Occupation | |||||

| - Manager, n(%) | 5,599 (42.0) | 25,160 (45.3) | 1,483 (46.8) | 275 (44.7) | |

| - Administrative, n(%) | 4,114 (30.8) | 15,764 (28.4) | 837 (26.4) | 181 (27.5) | <0.001 |

| - Service or labor, n(%) | 2,148 (16.1) | 8,937 (16.1) | 588 (18.5) | 151 (22.9) | |

| - Homemaker, n(%) | 1,480 (11.1) | 5,745 (10.3) | 263 (8.3) | 52 (7.9) | |

| Living alone, n(%) | 3,515 (25.3) | 14,816 (25.7) | 934 (28.2) | 225 (32.4) | <0.001 |

| Behavioral factors | |||||

| Alcohol, > 7 drinks/wk, n(%) | 1,913 (13.7) | 8,636 (14.9) | 353 (10.6) | 42 (6.1) | <0.001 |

| Current smoker, n(%) | 720 (5.2) | 3,032 (5.2) | 209 (6.3) | 68 (9.8) | <0.001 |

| No MVPA currently, n(%) | 5,444 (39.0) | 20,392 (35.2) | 1,367 (41.0) | 349 (50.1) | <0.001 |

| No strenuous PA in youth, n(%) | 1,263 (9.0) | 4,963 (8.6) | 350 (10.5) | 101 (14.5) | <0.001 |

| Report of excellent or very good health, n(%) | 7,800 (55.9) | 34,104 (58.9) | 1,608 (48.2) | 271 (39.1) | <0.001 |

| High caloric intake*, n(%) | 4,483 (32.1) | 19,353 (33.4) | 1,205 (36.1) | 297 (42.7) | <0.001 |

| Medical factors | |||||

| Age at menopause, mean (SD) | 47.9 (6.5) | 48.2 (6.5) | 48.2 (6.5) | 47.6 (6.7) | <0.001 |

| No term pregnancies, n(%) | 1,834 (13.1) | 7,055 (12.2) | 559 (16.8) | 191 (27.4) | <0.001 |

| History of | |||||

| - Coronary heart disease, n(%) | 1,189 (8.5) | 4,532 (7.8) | 349 (10.5) | 80 (11.5) | |

| - Coronary heart failure, n(%) | 154 (1.1) | 731 (1.3) | 90 (2.7) | 26 (3.7) | |

| - Stroke, n(%) | 241 (1.7) | 914 (1.6) | 83 (2.5) | 23 (3.3) | |

| - Diabetes, n(%) | 672 (4.8) | 2,791 (4.8) | 383 (11.5) | 11 (16.1) | <0.001 |

| - Hypertension, n(%) | 4,972 (35.6) | 20,059 (34.6) | 1,477 (44.3) | 349 (50.1) | |

| - Arthritis, n(%) | 7,425 (53.2) | 31,098 (53.6) | 2,050 (61.4) | 468 (67.2) | |

| - Cancer, n(%) | 2,138 (15.3) | 8,960 (15.4) | 509 (15.3) | 101 (14.5) | |

| - Lung disease, n(%) | 1,487 (10.7) | 5,638 (9.7) | 397 (11.9) | 84 (12.1) | |

| - Thyroid disorder, n(%) | 2,183 (15.6) | 10,607 (18.3) | 777 (23.3) | 159 (22.8) | |

| Depressive like symptoms (CES-D≥0.06), n(%) | 1,390 (10.2) | 5,363 (9.5) | 1,608 (48.2) | 271 (39.1) | <0.001 |

| Any bone fracture^, n(%) | 107 (0.8) | 306 (0.5) | 10 (0.3) | 5 (0.7) | 0.001 |

| 1+ falls in the past year, n(%) | 3,204 (22.9) | 13,501 (23.3) | 922 (27.6) | 201 (28.9) | <0.001 |

| Medications | |||||

| Hormone therapy, n(%) | 8,252 (59.1) | 33,084 (57.0) | 1,710 (51.2) | 342 (49.1) | <0.001 |

| Glucocorticosteroids, n(%) | 184 (1.4) | 715 (1.3) | 59 (1.9) | 6 (0.9) | 0.032 |

| Psychotropic drugs, n(%) | 1,338 (9.6) | 5,247 (9.0) | 369 (11.1) | 98 (14.1) | <0.001 |

| Beta-blockers, n(%) | 1,703 (12.9) | 6,384 (11.6) | 420 (13.4) | 96 (14.6) | <0.001 |

| Anticonvulsants, n(%) | 290 (2.2) | 981 (1.8) | 73 (2.3) | 25 (3.8) | <0.001 |

| Antimigraine drugs, n(%) | 105 (0.8) | 418 (0.8) | 21 (0.7) | 6 (0.9) | 0.862 |

High caloric intake defined as ≥ 1,727 kcal/day, where this range represents the highest tertile of dietary intake

Fracture defined as any fracture of the hip, upper leg, pelvis, knee, lower leg, ankle, foot, tailbone, spine or back, lower arm or wrist, hand, elbow, upper arm, shoulder or other, hormone replacement therapy

Note: MVPA – Moderate- vigorous physical activity; CES-D - Centers for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale

BMI at age 18 and SPI at older age

After adjusting for demographic factors, the odds ratio of SPI for those with underweight at 18 years old were not significantly different from SPI among participants with normal BMI at 18 years old (Table 2). The odds ratios of SPI for those with overweight or obesity were significantly greater than for normal weight at 18 years. After fully adjusting for lifestyle factors, medical history, and medications, the effects decreased slightly but remained significant in women with overweight and obesity.

Table 2.

Severe physical impairment (PF < 60) in relation to body mass index (BMI) class at 18 years old among postmenopausal women

| Model 1 (N = 69,806) | Model 2 (N = 69,538) | Model 3 (N = 66,110) | Model 4 (N = 60,499) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI class at 18 yrs | Odds ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | |||

| Underweight | 1.04 (0.99-1.10) | 0.99 (0.94-1.05) | 1.01 (0.95-1.07) | 1.01 (0.94-1.08) |

| Normal | (Reference) | (Reference) | (Reference) | (Reference) |

| Overweight | 1.83 (1.68-2.00) | 1.68 (1.52-1.85) | 1.51 (1.36-1.67) | 1.51 (1.35-1.69) |

| Obese | 3.29 (2.78-3.89) | 2.66 (2.21-3.21) | 2.27 (1.85-2.79) | 2.14 (1.72-2.65) |

Model 1. Adjusted for demographics factors including age at baseline, race/ethnicity, marital status, income, education, occupation and living status

Model 2. Adjusted for model 1 covariates and behavioral factors including smoking status, alcohol intake, current physical activity, physical activity during youth, total daily caloric intake, self-reported health

Model 3. Adjusted for model 2 covariates, and medical factors including history of coronary heart disease, congestive heart failure, stroke, diabetes, hypertension, arthritis, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, any fracture, falls in the last 12 months, depression, age at menopause, number of term pregnancies

Model 4. Adjusted for model 3 covariates and medications including contraception, hormone therapy, glucocorticosteroids, psychotropic drugs, beta-blockers, anticonvulsants and antimigraine drugs

Distribution of weight change transitions

Approximately 61% participants who self-reported being underweight at 18 years old transitioned into the normal BMI category at the Year 1 follow-up, while 26% transitioned into the overweight BMI class (Table 3). Most participants who self-reported having normal weight at 18 years old either stayed normal or transitioned to overweight or obese at Year 1. Nearly half of the participants who self-reported being overweight at 18 years old transitioned to the obese BMI class or maintained an overweight BMI. Participants with self-reported obesity at age 18 years generally maintained obesity or transitioned into the overweight class. Only 13% with self-reported obesity at age 18 shifted to the normal BMI class over time. A sensitivity analysis that adjusted for body weight changes occurring between the ascertainment of current weight and SPI (from Year 1 to Year 3) did not alter the results (data not shown).

Table 3.

Cross tabulation of body mass index (BMI) class in late-life according to BMI class at 18 years old among postmenopausal women

| BMI (late-life), n(%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI (18 yrs old) | Underweight (n=1,588) | Normal (n=36,829) | Overweight (n=23,772) | Obese (n=13,827) |

| Underweight (n=13,966) | 624 (4.5) | 8,475 (60.7) | 3,678 (26.3) | 1,189 (8.5) |

| Normal (n=58,016) | 940 (1.6) | 27,603 (47.6) | 18,940 (32.7) | 10,533 (18.2) |

| Overweight (n=3,338) | 19 (0.6) | 664 (19.9) | 1,015 (30.4) | 1,640 (49.1) |

| Obese (n=696) | 5 (0.7) | 87 (12.5) | 139 (20.0) | 465 (66.8) |

Weight change transitions over lifetime and SPI at older age

The odds of SPI at Year 3 follow-up was greater for women who transitioned from early age underweight status to overweight/obese compared to those who maintained the underweight BMI class, with successive adjustment for demographic factors, behavioral factors, medical factors and medications (Table 4). Women who transitioned from normal weight to either underweight or overweight/obese had an excess odds of SPI when compared to those who maintained the normal weight. Women with overweight/obesity who transitioned to a normal weight had reduced odds of SPI when compared to those who remained with overweight/obesity.

Table 4.

Severe physical impairment in relation to change in body mass index (BMI) class from 18 years old to late-life

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | ||||

| Underweight BMI at 18 years old | ||||

| Staying underweight | (Reference) | (Reference) | (Reference) | (Reference) |

| Becoming normal weight | 0.83 (0.65-1.06) | 0.88 (0.67-1.14) | 0.85 (0.64-1.13) | 0.94 (0.69-1.28) |

| Becoming overweight/obese | 1.96 (1.53-2.51) | 1.61 (1.23-2.11) | 1.40 (1.05-1.86) | 1.52 (1.11-2.09) |

| Normal weight BMI at 18 years old | ||||

| Staying normal weight | (Reference) | (Reference) | (Reference) | (Reference) |

| Becoming underweight | 1.69 (1.40-2.04) | 1.38 (1.12-1.69) | 1.29 (1.03-1.62) | 1.35 (1.06-1.71) |

| Becoming overweight/obese | 2.71 (1.68-2.00) | 2.12 (2.00-2.24) | 1.93 (1.81-2.06) | 1.97 (1.84-2.11) |

| Overweight and obese BMI at 18 years old | ||||

| Staying overweight/obese | (Reference) | (Reference) | (Reference) | (Reference) |

| Becoming normal weight | 0.37 (0.29-0.47) | 0.51 (0.39-0.66) | 0.55 (0.42-0.73) | 0.52 (0.39-0.71) |

Covariates for models listed in Table 2.

DISCUSSION

This analysis evaluated the association between weight history and transitions between BMI classes with SPI among postmenopausal women. We observed that women with both overweight and obesity at 18 years of age had a higher likelihood of SPI later in life. Moreover, underweight BMI status at 18 years old was not associated with SPI later in life. Women who transitioned from normal BMI to overweight or obese compared to women who remained normal BMI had greater odds of SPI. We also found women with normal BMI at age 18 years who transitioned into underweight status had a greater likelihood of SPI as compared to women who maintained normal BMI. It is important to note that a gain or loss in body weight is associated with SPI, suggesting that body weight is a powerful predictor of physical impairment.

The weight history findings are consistent with previous work examining the effect of adulthood BMI on late-life physical impairment. For example, one study found the greatest risk of physical impairment occurred in women who reported a history of middle-aged obesity14. Another study found that having higher BMI prior to old age increased the risk for physical impairment among older women18. These effects are supported by previous work demonstrating that longer exposure to excess body weight is associated with a higher likelihood of muscle weakness as measured by grip strength— a strong predictor of physical function19. Other studies which examined early adulthood weight found similar effects across various measures of physical function such as physical performance and mobility limitation15,27,28. Therefore, the present study adds to the existing literature by further supporting the modest to strong effect of excess body weight in early life on late-life physical impairments.

Evaluating the consequences of body weight transitions from early life to later life age on SPI is an important contribution of this study. We found that transitions from normal BMI in early age to either underweight or overweight/obese BMI increased odds of SPI as compared to remaining within a normal BMI class. These results are supported by another study reporting similar effects regarding weight gain over four years and increased odds of physical impairment among older women29. The authors also noted that women with overweight who lost weight improved physical functioning scores on the SF-36, which was similar to our findings showing that participants who transitioned from being overweight/obese had reduced likelihood of SPI. Similarly, another study demonstrated an association between weight gain from early to middle adulthood with functional limitations in late adulthood15. Our results remain congruent with previous work, noting that transitioning into higher BMI classes increases likelihood of SPI among postmenopausal women. We also found that women who self-reported being underweight in early adulthood and transitioned to being either overweight or obese increased their likelihood of late-life physical impairment. Additionally, the literature hasn't fully examined how weight loss in women with normal weight, particularly those who transition to a lower BMI class can impact physical function. This finding might be related to underlying clinical or sub-clinical conditions associated with weight loss and the onset of SPI30. To our knowledge, this is a unique finding in understanding the factors associated with late-life physical impairment in postmenopausal women.

Obesity is known to increase the risk of developing a variety of medical illnesses connected to onset of physical impairment in later life. With regard to mobility, obesity is clearly linked to the pathogenesis of cartilage degeneration in osteoarthritis, specifically in weight bearing joints, a major cause of physical impairment in older adults31. Obesity early in life is also associated with structural changes in the feet, plantar fat pad and plantar pressures which are known to impair gait and mobility function31-33. Additionally, obesity during childhood negatively impacts lower limb strength and power, where additional mass requires more effort to move against gravity, also interfering with normal gait mechanics of carrying excess weight34. Moreover, metabolic dysfunction, another predictor of functional impairment in older adults, is a hallmark condition of young adults with obesity35. Other obesity-linked conditions such as hypertension, cardiovascular disease, pulmonary disease, cancer, and cataracts are also associated with physical impairment in older adults3,36,37. Because obesity is associated with earlier onset of comorbidities, we speculate that lifetime obesity increases this exposure and partly explains the increases in odds of developing SPI in postmenopausal women. Though we adjusted for disease factors, we were unable to adjust for the onset or the duration of these diseases, which would affect physical function later in life. The underlying reasons for these associations are likely a culmination of all these factors.

Main strengths of this study included a large sample size and the availability of many potential confounders utilized to examine the association of weight and physical impairment in postmenopausal women. This allowed us to adjust on many important variables including demographics, lifestyle factors, chronic illnesses, depressed mood, and medications. Another strength of this study was the longitudinal collection of data, which enabled examination of life course weight class transitions that are associated with later life SPI likelihood.

There are limitations from our study that should be acknowledged. Results should be considered in the context of a retrospective cohort design that cannot fully assess the temporality of an association (i.e., cause and effect). Physical impairments were captured in late-life, thus the analysis does not consider pre-existing impairments (i.e., onset before age of 18 or before WHI enrollment). Also, factors causing physical impairments and treatments that could positively impact physical function (e.g., hip replacement) were not ascertained between the assessments for self-report body weight (Year 1) and physical function (Year 3). Similar to most cohort studies, the WHI study suffers from volunteer bias where volunteers tended to have a higher education and income than a representative sample38. Additionally, there was missing data that was more likely to occur in less educated and non-white women, which should be considered when generalizing these results. Information bias is concern of the study considering participants were asked to recall their body weight. For example, we noted that women underreported their weight by 2 kg. However, there are a few considerations that might minimize this bias. First, there is extensive research to support self-reported weight and height as sufficient for BMI categorization39-41 and evidence suggests older women accurately recall their body weight at youth42.43. Second, there was a strong correlation between self-reported weight and actual weight in this sample (r=0.91). Third, the error in self-reported weight is attenuated by examining the differences within participants. Lastly, we expect that under-reporting would occur in women who reported being under or normal weight at 18 years of age. Under-reporting directional bias is most likely to occur in women who reporting being under or normal weight at 18 years of age. The transitions into higher BMI categories among these groups as well as the effect on physical function could impact the statistical estimates in the null direction. Under-reporting bias could also accentuate the estimates if women under-reported their weight at age 18 and subsequently transitioned into a higher body weight class. Finally, weight changes that occurred over adulthood were not known to be intentional or unintentional lending to difficulty in interpreting whether weight transitions were related to clinical and or behavioral changes that would aid in creating a more specific public health recommendation.

Our findings suggest that maintenance of healthy weight during adulthood might reduce likelihood of SPI later in life. Physical impairments and disability are a major public health issue in older adults, and these results demonstrate that higher weight in early life and weight gain throughout life are major contributors of physical impairment in older women. Conversely, weight loss in young women with overweight and obesity was strongly connected to reduced likelihood of physical impairment in later life. These results suggest that intervention strategies to prevent weight gain early in life and maintain a healthy body weight throughout life will help to prevent or delay the onset of SPI in postmenopausal women.

Acknowledgments

M.J.L. (grant number R03DE022654), M.E.W. (grant numbers KL2TR000160 and U01HL105268), M.L.S. (grant numbers P30CA124435 and U01AR045583), M.L. (grant number N01WH42129-24-01) and T.M.M. (grant numbers R01AG042525 and P30AG028740) were supported by the National Institutes of Health during study conduct.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES:

A.A.W., S.S.S., R.N., L.G., J.W.B., J.K.O., R.A.S. and G.E.S. have nothing disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of Childhood and Adult Obesity in the United States, 2011-2012. JAMA. 2014;58(4):206. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aronne LJ. Epidemiology, morbidity, and treatment of overweight and obesity. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(Suppl 23):13–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Villareal DT, Apovian C,M, Kushner RF, Klein S. Obesity in Older Adults: Technical Review and Position Statement of the American Society for Nutrition and NAASO, The Obesity Society. Obes Res. 2005;13(11):1849–1863. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Runhaar J, Koes BW, Clockaerts S, Bierma-Zeinstra SM. A systematic review on changed biomechanics of lower extremities in obese individuals: a possible role in development of osteoarthritis. Obes Rev. 2011;12(12):1071–1082. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Furukawa S, Fujita T, Shimabukuro M, Iwaki M, Yamada Y, Nakajima Y, et al. Increased oxidative stress in obesity and its impact on metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2004;114(12):1752–1761. doi: 10.1172/JCI21625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brinkley TE, Hsu FC, Beavers KM, Church T, Goodpaster B, Stafford R, et al. Total and Abdominal Adiposity Are Associated With Inflammation in Older Adults Using a Factor Analysis Approach. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67(10):1099–1106. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stenholm S, Koster A, Alley DE, Houston D, Kanaya A, Lee J, et al. Joint Association of Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome With Incident Mobility Limitation in Older Men and Women--Results From the Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65A(1):84–92. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beavers KM, Miller ME, Rejeski WJ, Nicklas BJ, Kritchevsky SB. Fat Mass Loss Predicts Gain in Physical Function With Intentional Weight Loss in Older Adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(1):80–86. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hubert HB, Feinleib M, McNamara PM, Castelli WP. Obesity as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease: a 26-year follow-up of participants in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1983;67(5):968–977. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.67.5.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faith MS, Matz PE, Jorge MA. Obesity-depression associations in the population. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2002;53(4):935–942. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00308-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ford Es, Williamson Df, Liu S. Weight Change and Diabetes Incidence: Findings from a National Cohort of US Adults. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146(3):214–222. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and Trends in Obesity Among US Adults, 1999-2008. JAMA. 2010;303(3):235. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of Obesity and Trends in the Distribution of Body Mass Index Among US Adults, 1999-2010. JAMA. 2012;307(5):491. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Backholer K, Pasupathi K, Wong E, Hodge A, Stevenson C, Peeters A. The relationship between body mass index prior to old age and disability in old age. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2012;36(9):1180–1186. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Houston DK, Stevens J, Cai J, Morey MC. Role of Weight History on Functional Limitations and Disability in Late Adulthood: The ARIC Study. Obes Res. 2005;13(10):1793–1802. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peeters A, Bonneux L, Nusselder WJ, De Laet C, Barendregt JJ. Adult Obesity and the Burden of Disability throughout Life. Obes Res. 2004;12(7):1145–1151. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams ED, Eastwood SV, Tillin T, Hughes AD, Chaturvedi N. The effects of weight and physical activity change over 20 years on later-life objective and self-reported disability. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(3):856–865. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Launer L, Harris T, Rumpel C, Madans J. Body mass index, weight change, and risk of mobility disability in middle-aged and older women. The epidemiologic follow-up study of NHANES I. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1994;271(14):1093–1098. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stenholm S, Sallinen J, Koster A, Rantanen T, Sainio P, Heliovaara M, et al. Association between Obesity History and Hand Grip Strength in Older Adults--Exploring the Roles of Inflammation and Insulin Resistance as Mediating Factors. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66A(3):341–348. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hung WW, Ross JS, Boockvar KS, Siu AL. Recent Trends in Chronic Disease, Impairment and Disability Among Older Adults in the United States. BMC Geriatr. 2011;11(1):47. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-11-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murtagh KN, Hubert HB. Gender Differences in Physical Disability Among an Elderly Cohort. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(8):1406–1411. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.8.1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bouchard DR, Senechal M, Slaught J, Jones P. Obesity History Affects Health Profile and Physical Capacity of Postmenopausal Obese Women; A Pilot Study. Journal of Research in Obesity. 2013;2013(2013):e1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Design of the Women's Health Initiative Clinical Trial and Observational Study. Controlled Clinical Trials. Controlled Clin Trials. 1998;19(1):61–109. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(97)00078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-ltem Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36). Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bohannon RW, Depasquale L. Physical Functioning Scale of the Short-Form (SF) 36: Internal Consistency and Validity With Older Adults. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2010;33(1):16–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patterson RE, Kristal AR, Tinker LF, Carter RA, Bolton MP, Agurs-Collins T. Measurement Characteristics of the Women's Health Initiative Food Frequency Questionnaire. Annals of Epidemiology. 1999;9(3):178–187. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(98)00055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Houston Denise K, et al. The association between weight history and physical performance in the Health, Aging and Body Composition study. Int J Obes. 2007;31(11):1680–1687. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strandberg Timo E., et al. Impact of midlife weight change on mortality and quality of life in old age. Prospective cohort study. Int J Obes. 2003;27(8):950–954. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fine JT, Colditz GA, Coakley EH, et al. A Prospective Study of Weight Change and Health-Related Quality of Life in Women. JAMA. 1999;282(22):2136. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.22.2136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marton Keith I., Sox Harold C., Krupp Jan R. Involuntary weight loss: diagnostic and prognostic significance. Ann Intern Med. 1981;95(5):568–574. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-95-5-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hart DJ, Spector TD. The relationship of obesity, fat distribution and osteoarthritis in women in the general population: the Chingford Study. J Rheumatol. 1993;20(2):331–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hills AP, Hennig EM, Byrne NM, Steele JR. The biomechanics of adiposity - structural and functional limitations of obesity and implications for movement. Obes Rev. 2002;3(1):35–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789x.2002.00054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nass D, Henning EM, Van Treek R. The thickness of the heel pad loaded by bodyweight in obese and normal weight adults. Women. 1999;1999(49):6. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hills AP, Hennig EM, McDonald M, Bar-Or O. Plantar pressure differences between obese and non-obese adults: a biomechanical analysis. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25(11):1674–1679. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dowling AM, Steele JR, Baur LA. Does obesity influence foot structure and plantar pressure patterns in prepubescent children?. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25(6):845–852. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Després JP. 7 Dyslipidaemia and obesity. Baillière's Clin Endocrin Metab. 1997;8(3):629–660. doi: 10.1016/s0950-351x(05)80289-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sinclair AJ, Conroy S,P, Bayer AJ. Impact of Diabetes on Physical Function in Older People. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(2):233–235. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boughner R. Volunteer Bias. In: Salkind Neil J., editor. Ency Research Design. SAGE Publications, Inc; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2010. pp. 1609–1611. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stewart AL. The reliability and validity of self-reported weight and height. Journal of Chronic Diseases. 1982;35(4):295–309. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(82)90085-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sutin AR. Optimism, pessimism, and bias in self-reported body weight among older adults. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21(9):E508–11. doi: 10.1002/oby.20447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stunkard AJ, Albaum JM. The accuracy of self-reported weights. Am J Clin Nutr. 1981;34(8):1593–1599. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/34.8.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perry GS, Byers TE, Mokdad AH, Serdula MK, Williamson DF. The validity of self-reports of past body weights by US adults. Epidemiology. 1995;6(1):61–66. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199501000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stevens J, Keil JE, Waid LR, Gazes PC. Accuracy of current, 4-year, and 28-year self-reported body weight in an elderly population. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132(6):1156–63. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]