Abstract

There is a paucity of data to support evidence-based practices in the provision of patient/family education in the context of a new childhood cancer diagnosis. Since the majority of children with cancer are treated on pediatric oncology clinical trials, lack of effective patient/family education has the potential to negatively affect both patient and clinical trial outcomes. The Children’s Oncology Group Nursing Discipline convened an interprofessional expert panel from within and beyond pediatric oncology to review available and emerging evidence and develop expert consensus recommendations regarding harmonization of patient/family education practices for newly diagnosed pediatric oncology patients across institutions. Five broad principles, with associated recommendations, were identified by the panel, including recognition that (1) in pediatric oncology, patient/family education is family-centered; (2) a diagnosis of childhood cancer is overwhelming and the family needs time to process the diagnosis and develop a plan for managing ongoing life demands before they can successfully learn to care for the child; (3) patient/family education should be an interprofessional endeavor with 3 key areas of focus: (a) diagnosis/treatment, (b) psychosocial coping, and (c) care of the child; (4) patient/family education should occur across the continuum of care; and (5) a supportive environment is necessary to optimize learning. Dissemination and implementation of these recommendations will set the stage for future studies that aim to develop evidence to inform best practices, and ultimately to establish the standard of care for effective patient/family education in pediatric oncology.

Keywords: childhood cancer, new diagnosis, patient/family education, Children’s Oncology Group

Introduction/Background

The Children’s Oncology Group (COG) is the only pediatric clinical trials program operating under the National Cancer Institute’s National Clinical Trials Network (Adamson, 2013). The majority of the more than 15 000 children and adolescents diagnosed with cancer in the United States each year (Ward, DeSantis, Robbins, Kohler, & Jemal, 2014) are treated on COG clinical trials at over 220 member institutions that include leading universities, cancer centers, and children’s hospitals (Shochat et al., 2001). The COG Nursing Discipline consists of nearly 2500 registered nurses representing all COG institutions, and nurses assume a major role in providing patient/family education (Landier, Leonard, & Ruccione, 2013). Since the majority of children with cancer are treated on pediatric oncology clinical trials (Shochat et al., 2001), lack of effective patient/family education has the potential to negatively affect both patient and clinical trial outcomes. Examples include incorrect administration of home medications or inability of the parent/caregiver to recognize and seek emergent treatment for a child who is experiencing potentially life-threatening complications. Therefore, understanding the principles and strategies for successful parent/caregiver learning in the context of a new diagnosis of childhood cancer is essential in promoting the well-being of the patients and their families, facilitating parental/child adjustment to the diagnosis and treatment, and contributing to the successful implementation and completion of clinical trials (Landier et al., 2013).

Patient/family education is “a series of structured or non-structured experiences designed to develop the skills, knowledge, and attitudes needed to maintain or regain health” (Blumberg, Kerns, & Lewis, 1983). Patient/family education has been recognized as a core responsibility of the pediatric oncology nurse since the 1980s (Fochtman & Foley, 1982; Hockenberry & Coody, 1986; Johnson & Flaherty, 1980; Kramer & Perin, 1985; McCalla & Santacroce, 1989) and is a major component of the current scope and standards of practice for pediatric oncology nurses (Nelson & Guelcher, 2014). Although many positive outcomes have been attributed to patient/family education, including increased treatment adherence, fewer hospitalizations, improved self-management capabilities, and shorter hospital stays (Kelo, Martikainen, & Eriksson, 2013; Kramer & Perin, 1985), there is currently a paucity of evidence to support an evidence-based (best practices) approach to patient/family education in pediatric oncology (Aburn & Gott, 2011; Landier et al., 2013; Slone, Self, Friedman, & Heiman, 2014). As a result, evidence-based standards to inform practice across institutions are currently lacking, resulting in considerable variability in the provision of education for newly diagnosed patients (Slone et al., 2014; Withycombe et al., 2016), which may lead to decreased quality of the information provided (Baggott, Beale, Dodd, & Kato, 2004). The COG Nursing Discipline has developed educational materials specifically targeted to parents/caregivers of newly diagnosed patients participating in COG clinical trials (Kotsubo & Murphy, 2011; Murphy, 2011). While these materials address the provision of safe care and foster an understanding of clinical trials and protocol adherence, their development was guided by expert opinion, due to the paucity of available evidence to inform design and content.

The lack of evidence-informed approaches to patient-family education in pediatric oncology represents a significant gap in knowledge. Recognizing this gap, the COG Nursing Discipline identified “understanding the effective delivery of patient/family education” as a high-priority aim within its 5-year blueprint for nursing research (Landier et al., 2013), and set in motion a series of studies to address this aim (Haugen et al., 2016; Rodgers, Laing, et al., 2016; Rodgers, Stegenga, Withycombe, Sachse, & Kelly, in press; Withycombe et al., 2016). A consensus conference was subsequently organized by the Nursing Discipline to bring together experts from multiple disciplines within and outside pediatric oncology to review the findings from the COG studies, as well as related work in other pediatric subspecial-ties, in order to develop expert consensus recommendations regarding best practices for the provision of patient/family education for newly diagnosed patients across the COG.

Methods

In October 2015, the COG Nursing Discipline convened a consensus conference focused on patient/family education for newly diagnosed families, during which findings from studies addressing current literature (Rodgers, Laing, et al., 2016), institutional practices (Withycombe et al., 2016), essential informational content (Haugen et al., 2016), parental perspectives (Rodgers, Stegenga, et al., in press), and the viewpoints of 3 patient/family education experts from subspecialties outside pediatric oncology (Ahern, 2015; Bondurant, 2015; Weiss, 2015) were presented, discussed, and critiqued by conference participants. All experts and participants were provided with copies of these presentations to review prior to the conference.

Following the presentations, a consensus-building session was convened, during which an interprofessional panel of experts from pediatric oncology, nursing, behavioral sciences, and patient advocacy reviewed and critiqued the evidence presented at the conference, with the goal of developing best-practice recommendations. Recognizing that high-level evidence to inform best practices regarding patient/family education in pediatric oncology was not currently available, the panel recommended using available evidence, in combination with expert consensus, to develop principles and recommendations for potentially better practices for patient/family education for newly diagnosed pediatric oncology patients. This article summarizes the expert panel’s consensus-based principles and associated recommendations, in order that they may be used collaboratively across institutions to harmonize patient/family education practices, which will facilitate the development of further evidence to inform best practices.

Findings

Five broad principles, with associated recommendations, were identified by the panel (Box 1), and are summarized below.

Box 1. Key Principles and Recommendations from the Expert Panel.

-

In pediatric oncology, patient/family education is family-centered

Include all individuals who are central to the patient’s care

The family is considered an important part of the child’s health care team

Teach more than one caregiver in each family, whenever possible

-

A diagnosis of cancer in a child is overwhelming for the family

-

Before the family is able to learn to care for the child, they need:

Time to process the diagnosis emotionally and

A plan to manage ongoing life demands in light of the diagnosis

The psychosocial services team plays a key role in supporting the family

The family’s learning priorities may differ from those of health care professionals during the initial timeframe

Address the learners’ fears/concerns prior to proceeding with teaching

-

-

Quality of teaching determines family readiness to care for their child at home

-

Patient/family education for newly diagnosed families should be an interprofessional responsibility, with a focus on 3 key areas:

Diagnosis/treatment

Psychosocial coping

Care of the child

Standardized educational content, but individualize educational methods

Pacing of patient/family education is important; the initial focus should be on the “essentials” (ie, survival skills)

All health care professionals should receive training in the principles and practice of patient/family education in pediatric oncology

Consistent messaging across disciplines (eg, pediatric oncology, nursing, psychosocial) and platforms (eg, written, oral, electronic) is essential

Assess family readiness to care for the child at home from multiple perspectives (parent, nurse, physician, psychosocial services team)

-

-

Patient/family education occurs across the continuum of care

Provide only essential education during the initial period following diagnosis

Provide education across care settings and transitions

-

A supportive environment is required to optimize learning

Focus on listening and avoid distractions while teaching

Provide education that is understandable and culturally sensitive

Provide anticipatory guidance (ie, help the family to ask questions)

Reassure the family that initial learning is typically a gradual process

1. In Pediatric Oncology, Patient/Family Education Is Family-Centered

The expert panel recognized that in pediatric oncology, patient/family education is family-centered. Thus, the panel recommended that (1) all individuals who are central to the patient’s care (ie, “family”—the patient [when developmentally appropriate], parents, siblings, guardians, grandparents, caregivers, and others) should be included in education, which will often involve multiple generations as learners and providers of the child’s care; (2) family should be viewed as an important part of the child’s health care team; and (3) whenever possible, more than 1 caregiver in each family should be prepared to care for the child (although teaching additional care-givers may be sequenced at a later time rather than during the period immediately following the initial diagnosis).

2. A Diagnosis of Cancer in a Child Is Overwhelming for the Family

The expert panel agreed that following a diagnosis of childhood cancer, the family needs time to (1) process the diagnosis and manage emotional responses and (2) determine how they will manage ongoing life demands (eg, issues related to parent/caregiver employment, maintaining insurance, making arrangements for care of siblings, accessing transportation to the medical facility, etc), before they are able to successfully learn the specifics of care for their newly diagnosed child. Although all health care disciplines are involved with the family to some extent during the initial period following diagnosis, the panel recognized that the psychosocial services team (which may include psychosocial professionals, eg, psychologists, social workers, child life specialists, and/or health educators) plays a significant role in supporting the family as they engage in adaptive coping strategies and helping the family identify a workable plan for managing ongoing life demands. The panel also found that it is important for all health care providers to understand that the learning priorities of the family may differ from those of health care professionals during this stressful period, and that fears and concerns of the learners should be addressed prior to initiating teaching regarding the child’s care needs. This concept was expressed as “meeting the family where they are.”

3. Quality of Teaching Determines Family Readiness to Care for Their Child at Home

The expert panel made 6 core recommendations regarding quality of teaching, as follows:

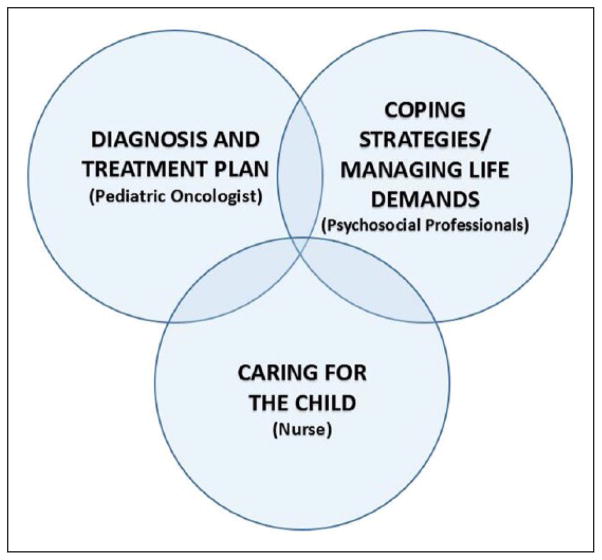

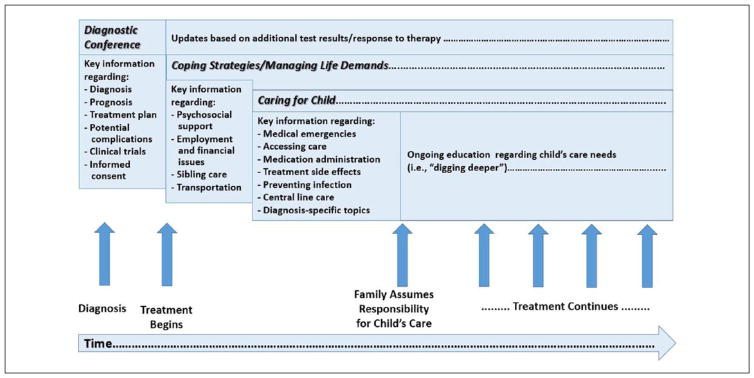

Patient/family education for newly diagnosed families should be an interprofessional responsibility, with a focus on 3 key areas: Diagnosis/treatment, psychosocial coping, and care of the child. The panel recommended an interprofessional approach to patient/family education in order to address the 3 key foci of education for newly diagnosed families (Figure 1). (i) Diagnosis and treatment (generally led by the pediatric oncologist). The panel recognized that there is often urgency for delivery of this component of education, which generally must occur before the child’s treatment can be initiated, and it is most commonly accomplished in the setting of a diagnostic conference. Essential information that must be conveyed includes a description of the disease and its etiology, the planned treatment and potential complications (acute and long term), and the child’s prognosis (Mack & Grier, 2004). Families often feel overwhelmed with the amount of information that they receive during this time; however, the panel recognized that the extent of information presented is often driven by the need to obtain informed consent (permission) prior to treatment initiation (Kodish et al., 1998). Given that not all health care team members can be present at the diagnostic conference, and that the family often has difficulty remembering the details of the information conveyed, the panel recommended that 1 team member be assigned to compile a concise, accurate, and sensitive summary of this conference, using a standardized template (and an audiorecording of the session, when possible). This summary could then be placed in the child’s medical records and reviewed with/given to the family, facilitating consistent messaging across health care disciplines regarding the child’s diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment plan. The panel also recognized that the diagnostic conference summary should be considered a “living document” that should be updated over time as new information emerges, such as additional test results or treatment response evaluations. (ii) Psychosocial coping (generally led by the psychosocial services team). The panel recognized that following diagnosis, the family needs time and support to process the diagnosis and cope with their emotions, as well as guidance in developing a plan for managing the practical implications of the child’s diagnosis within the context of ongoing family life demands (as described in Principle 2, above). (iii) Caring for the child (generally led by the nursing discipline). Once the family has been informed of the diagnosis and treatment plan, and has had time to process their initial emotional reactions and cope with managing the demands of everyday living in the context of the diagnosis, the family must also learn essential information regarding the child’s care needs. The panel recommended that the information conveyed during this initial time frame be limited to crucial concepts necessary to prepare the family to provide safe care for the child, including “survival skills,” such as medication administration, central line care, recognition of health emergencies (eg, fever), and understanding how and when to access emergent care. The panel recognized that there may be variability across institutions regarding the disciplines responsible for teaching the 3 key content areas, and that additional disciplines beyond nursing, oncology, and psychosocial services may be involved at some institutions (eg, pharmacy).

Standardize educational content, but individualize educational methods. The panel recommended development of core essential educational content for newly diagnosed families. This core content should be limited to essential information necessary for initiation of treatment, managing the logistics of everyday living, and initial care of the child (Table 1). Additionally, the panel recommended the use of structured tools (eg, checklists or “handoff tools”) to guide teaching of core content and assessment of successful learning. Recognizing the varied diagnoses, treatment strategies, and age ranges in pediatric oncology, the panel recommended development of algorithms or templates to facilitate the implementation of customized teaching plans that contain the essential content, but that are tailored to each child’s specific diagnosis, treatment plan, and age/developmental stage. Despite the necessity of identifying core educational content, the panel also recognized the importance of individualizing methods for providing education to address differences in learning needs, including language, literacy/health literacy, culture, emotional state, and preferred learning style, with an emphasis on tailored communication and relationship-based learning (Table 2).

Pacing of patient/family education is important; the initial focus should be on the “essentials” (ie, survival skills). The panel recommended presentation of educational content in a tiered and sequenced fashion, with initial education focused only on the essentials, adding more detailed content later (ie, allowing the family to “dig deeper”), if appropriate.

All health care professionals should receive training in the principles and practice of patient/family education in pediatric oncology. The expert panel acknowledged that educational needs are potentially present during each patient encounter, and recommended that all health care professionals receive some training in the provision of patient/family education so that “teachable moments” can be seized whenever they occur (including on nights, weekends, and holidays). The panel also recommended that a clear plan for education be established for each patient, and that key individuals from the patient’s primary treatment team maintain overall responsibility and accountability for this education. Moreover, the panel advised that key individuals on the health care team responsible for patient/family education should receive specialized training and (when/if available in the future) certification for this role.

Consistent messaging across disciplines (eg, pediatric oncology, nursing, and psychosocial) and platforms (eg, written, oral, electronic) is essential. Recognizing that consistency in messaging across disciplines and platforms is essential to avoid confusion and dissatisfaction with education on the part of families, the panel recommended that a responsible individual be assigned to oversee the educational process for each family in order to assure consistency (as discussed in 3d, above). The panel recognized that the individual responsible for education would not necessarily provide all of the education for the family; in fact, the panel acknowledged that more than 1 team member often needs to be involved in the provision of patient/family education (eg, someone knowledgeable about diagnosis/treatment, someone knowledgeable about care of the child at home, etc), and that delineation of roles in the educational process is necessary. Thus, the panel recommended that regardless of who is providing the education, all team members should be aware of the content that other disciplines may be teaching, so that they can reinforce the educational messages of other team members. This will necessitate development of effective systems for communicating information regarding patient/family education among members of the health care team, and it will require integration with existing communication platforms, such as electronic medical records. Importantly, the panel also recommended that all forms of education (eg, verbal, written, electronic) be consistent in messaging, necessitating awareness by team members of the content of educational materials distributed to families, as well as frequent updating of these materials to keep messages clear, consistent, and well-aligned with educational practices.

Assess family readiness to care for the child at home from multiple perspectives. The panel recommended assessment of family readiness to care for the child from the perspectives of the parent/caregiver, nurse, physician, and psychosocial services team while recognizing that readiness is optimized when evident from all perspectives. The panel agreed that the health care team is instrumental in moving the family toward readiness, and it must do so using a plan that includes multiple assessment and intervention techniques, such as “think forward” (ie, helping the parent envision and address scenarios that may occur while caring for the child at home; Weiss, 2015) and “teach-back” (ie, having the caregiver demonstrate their understanding of home care skills to the health care provider; Kornburger, Gibson, Sadowski, Maletta, & Klingbeil, 2013). Additionally, the panel recommended the development of a concise list of important reminders for caregivers (eg, a 1-page document or magnet) that can be kept in a convenient and easily accessible location, such that it is readily available for reference whenever needed.

Figure 1.

Interprofessional collaboration for patient/family education in newly diagnosed families.

Table 1.

Essential Initial Educational Content for Newly Diagnosed Families.

| Key Content Area | Essential Educational Content |

|---|---|

| Diagnosis/treatment | Diagnosis |

| Treatment plan, including clinical trials and informed consent (if applicable) | |

| Prognosis | |

| Potential complications (acute, long term), including fertility preservation options, if applicable | |

| Coping strategies/managing life demands | Anticipatory guidance and normalization of emotional responses/managing emotions |

| Anticipatory guidance regarding accessing psychosocial support services (eg, supportive counseling and peer-to-peer support) | |

| Accessing help with work-related and financial issues (eg, parent/caregiver work absences, insurance issues, and financial resources) | |

| Arranging care for other children/dependent family members | |

| Accessing help with transportation for medical care | |

| Care of the child | Identification of medical emergencies (eg, temperature-taking, fever) |

| Accessing emergent care (ie, who/how/why/when to call the health care team) | |

| Medication administration | |

| Treatment side effects (eg, nausea) | |

| Prevention of infection | |

| Central line care (if applicable) | |

| Diagnosis-specific topics (eg, postoperative/wound care, pain, safety, side effects of specific chemotherapy agents) |

Table 2.

Individualizing Education for Newly Diagnosed Families.

| Learner Characteristics | Suggested Tailoring of Education |

|---|---|

| Learning style | Assess preferred learning style, literacy, and health literacy prior to initiation of education |

| Build a relationship with the learner | |

| Use techniques that enhance the learner’s self-efficacy (eg, involvement in the child’s care during hospitalization, hands-on learning) | |

| Use a “teaching toolbox” that includes multiple modalities, including low- to high-technology options, developmentally appropriate content, and varied learning strategies (eg, active learning-simulation, one-on-one interaction, video modules, web-based tools, hands-on training, written materials, COG Family Handbook) | |

| Language/literacy/culture | Provide content in the learner’s preferred language |

| Use simple (nonmedical) language (ie, at or below a 5th grade level) | |

| Strive for cultural congruency when reviewing key educational content with the learner (eg, dietary instructions) | |

| Emotional state (“feeling overwhelmed”) | Set appointment times for teaching, and create meeting agendas (ie, “action plans”) |

| Keep educational sessions brief | |

| Provide information in small (ie, “bite-sized”) segments | |

| Repeat essential information over time | |

| Avoid giving families excessive amounts of written material (ie, avoid “paper overload”) | |

| For parents of young children, develop a plan to have the child cared for during teaching sessions so that the parent(s) can devote their full attention to learning |

Note. COG = Children’s Oncology Group.

4. Patient/Family Education Occurs Across the Continuum of Care

The expert panel recognized that in pediatric oncology, transitions frequently occur across care settings (ie, inpatient to outpatient, or vice versa), and that planned readmissions or sequenced outpatient encounters are typically expected for most patients (ie, for continuation of therapy). Therefore, the panel recommended teaching only the “essentials” following the child’s initial diagnosis, with education continuing across care settings and transitions (ie, throughout the “service line,” with a focus on “care transitions”) so that families are able to navigate the experience of care through education (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Continuum of education in pediatric oncology for newly diagnosed families.

5. A Supportive Environment Is Required to Optimize Learning

Finally, the expert panel recognized that for patient/family education to be successful, it is important to establish an environment that optimizes learning, by (1) conveying to the family that the educator is there to listen (ie, is not distracted); (2) providing education that is understandable and culturally sensitive; (3) providing the family with anticipatory guidance (ie, helping the family to be informed in order to ask questions); and (4) reassuring the family that learning to care for the child is often a gradual process, all of their questions will be answered, no question is foolish, and it is acceptable to ask the same question multiple times.

Discussion and Conclusions

As a result of this consensus conference, the interprofessional expert panel identified key issues related to the provision of patient/family education for newly diagnosed pediatric oncology patients that have significant implications for practice and research. To our knowledge, this panel formally identified, for the first time, 3 key foci of the educational process for newly diagnosed families in pediatric oncology: (1) Understanding the child’s diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis; (2) Considering how the family can contend with the diagnosis (ie, coping with emotions and management of ongoing life demands); and (3) Recognizing what the family needs to know to provide safe care for the child at home (Figure 1). The experts agreed that these 3 foci must be dealt with sequentially to optimize learning (Figure 2); thus, importantly, the experts recommended that patient/family education in pediatric oncology be done on a continuum—across care transitions—and recognized that not all teaching must be accomplished immediately following diagnosis. Similar to other pediatric chronic illnesses, such as type I diabetes (Ahern, 2015) or premature birth (Bondurant, 2015), a diagnosis of childhood cancer often occurs abruptly, significantly disrupting family equilibrium (Clarke-Steffen, 1993). Childhood cancer treatment typically involves multiple planned readmissions to the hospital or sequenced outpatient encounters; thus, there are substantial opportunities for continuation of education beyond the period surrounding the initial diagnosis (O’Leary, Krailo, Anderson, & Reaman, 2008). The expert panel identified these planned encounters for future therapy as opportunities to continue the process of patient/family education across the continuum of care (including home and community settings), allowing education during the initial period to be focused solely on essential information, and potentially decreasing the “information overload” so commonly experienced by families of children newly diagnosed with cancer (Aburn & Gott, 2011; Rodgers, Stegenga, et al., in press).

The panel also identified the importance of developing core informational content, while individualizing methods of providing education to families. Core educational content important for newly diagnosed families is commonly identified in other pediatric chronic illnesses, such as type 1 diabetes (Silverstein et al., 2005), asthma (National Asthma Education Prevention Program, 2007), and sickle cell disease (Yawn et al., 2014). The necessary educational content associated with each of these diseases is generally similar for all children within a disease group. In contrast, in pediatric oncology the necessary educational content may differ by diagnosis, treatment plan, and age/developmental stage of the patient. Nevertheless, based on available evidence presented at the consensus conference, the expert panel identified essential content across diagnoses, as well as diagnosis-specific content, for newly diagnosed families (Haugen et al., 2016; Rodgers, Laing, et al., 2016; Rodgers, Stegenga, et al., in press; Withycombe et al., 2016). The panel also recommended individualized methods of providing education and tailoring core content based on current evidence, such as consideration of literacy/health literacy and cultural congruence (Kornburger et al., 2013; Lerret & Weiss, 2011; Weiss, 2015; Weiss et al., 2008). In alignment with core principles in pediatrics (Committee on Hospital Care & Institute for Patient Family-Centered Care, 2012), the panel emphasized the importance of family-centered education by recommending inclusion of all individuals in the educational process who are central to the child’s care.

Finally, the panel emphasized the importance of consistency of messaging across disciplines, establishing a supportive environment for learning, and training of health care providers in the provision of patient/family education. These issues have been identified as important in other pediatric chronic illness populations, and some pediatric subspecialties have developed certification programs and standards for health care professionals who provide education to patients and families (Gardner et al., 2015; Schreiner, Kolb, O’Brian, Carroll, & Lipman, 2015). Similarly, the panel recommended development of standards regarding the provision of patient/family education, as well as training for health care professionals involved in caring for newly diagnosed pediatric oncology patients, with a focus on developing the skills required for effective patient/family education. The panel endorsed future development of certification for individuals with overall responsibility for patient/family education in pediatric oncology settings.

Dissemination and implementation of the panel’s recommendations will set the stage for future studies that develop and test core content, teaching and learning strategies, and associated educational tools. The expert panel recognized that collaboration across institutions will be necessary to develop high-quality evidence in order to inform best practices, and ultimately to establish the standard of care for effective patient/family education in pediatric oncology.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Supported by the National Cancer Institute (R13CA196165, PIs—Landier and Hockenberry) and by the National Cancer Institute/National Clinical Trials Network Group Operations Center Grant (U10CA180886, PI—Adamson).

Biographies

Wendy Landier, PhD, RN, CPNP, CPON®, is an Associate Professor in the Schools of Medicine and Nursing, and a member of the Institute for Cancer Outcomes and Survivorship at the University of Alabama at Birmingham in Birmingham, Alabama.

JoAnn Ahern, MSN, APRN, CDE, BC-ADM, is Manager of the Pediatric Diabetes Program for the Western Connecticut Health Network in Danbury, Connecticut.

Lamia P. Barakat, PhD, is Director of Psychosocial Services in Oncology at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and Professor in the Department of Pediatrics, Division of Oncology, at the Perelman School of Medicine of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Smita Bhatia, MD, MPH, is a Professor in the Division of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology and Director of the Institute for Cancer Outcomes and Survivorship in the School of Medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham in Birmingham, Alabama.

Kristin M. Bingen, PhD is an Associate Professor of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology/BMT in the Department of Pediatrics at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Patricia G. Bondurant, DNP, RN, CNS is Chief Quality Officer at Transform Healthcare Consulting in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Susan L. Cohn, MD is a Professor in the Department of Pediatrics, Section of Hematology/Oncology, and Director of Clinical Sciences at the University of Chicago in Chicago, Illinois.

Sarah K. Dobrozsi, MD is an Assistant Professor of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology/BMT in the Department of Pediatrics at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Maureen Haugen, RN, MS, CPNP, CPON®, is a Pediatric Nurse Practitioner on the Hematology Malignancy Team and the APN Manager in Hematology/Oncology/Stem Cell Transplant at Lurie Children’s Hospital in Chicago, Illinois.

Ruth Anne Herring, MSN, RN, CPNP, CPHON®, is the Patient/Family Education Coordinator at Cook Children’s Medical Center in Ft. Worth, Texas.

Mary C. Hooke, PhD, APRN, PCNS, CPON®, is an Assistant Professor at the University of Minnesota School of Nursing in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Melissa Martin, MSN, RN, CPNP, CPON, is a Nurse Practitioner in Pediatric Oncology at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta in Atlanta, Georgia and serves as a Patient Advocate for the Children’s Oncology Group.

Kathryn Murphy, BSN, RN, is a Clinical Research Nurse at the Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Amy R. Newman, MSN, RN, PNP is a Nurse Practitioner in Pediatric Hematology/Oncology/BMT in the Department of Pediatrics at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Cheryl C. Rodgers, PhD, RN, CPNP, CPON®, is an Assistant Professor at Duke University School of Nursing in Durham, North Carolina.

Kathleen S. Ruccione, PhD, MPH, RN, CPON®, FAAN, is an Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Doctoral Programs at Azusa Pacific University School of Nursing in Azusa, California.

Jeneane Sullivan, MSN, RN, CPON®, is an Oncology Patient/Family Education Specialist at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Marianne Weiss, DNSc, RN is the Wheaton Franciscan Healthcare, St. Joseph/Sister Rosalie Klein Professor of Women’s Health at Marquette University College of Nursing in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Janice Withycombe, PhD, RN, MN is an Assistant Professor in the Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia.

Lise Yasui serves as a Patient Advocate for the Children’s Oncology Group, Monrovia, California.

Marilyn Hockenberry, PhD, RN, PPCNP-BC, FAAN, is the Associate Dean for Research Affairs and the Bessie Baker Distinguished Professor of Nursing at Duke University School of Nursing in Durham, North Carolina.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Aburn G, Gott M. Education given to parents of children newly diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia:Anarrativereview. JournalofPediatricOncology Nursing. 2011;28:300–305. doi: 10.1177/1043454211409585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamson PC. The Children’s Oncology Group’s 2013 five year blueprint for research. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2013;60:955–956. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahern JA. Patient/family education in pediatric type I diabetes: Current best practices. Paper presented at the Patient/Family Education in Pediatric Oncology, State of the Science Symposium; Dallas, TX. 2015. Oct 6, [Google Scholar]

- Baggott C, Beale IL, Dodd MJ, Kato PM. A survey of self-care and dependent-care advice given by pediatric oncology nurses. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 2004;21:214–222. doi: 10.1177/1043454203262670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg BD, Kerns PR, Lewis MJ. Adult cancer patient education: An overview. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 1983;1(2):19–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bondurant PG. Parent education for infants in the NICU: Current best practices. Paper presented at the Patient/Family Education in Pediatric Oncology, State of the Science Symposium; Dallas, TX. 2015. Oct 6, [Google Scholar]

- Clarke-Steffen L. Waiting and not knowing: the diagnosis of cancer in a child. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 1993;10:146–153. doi: 10.1177/104345429301000405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Hospital Care & Institute for Patient Family-Centered Care. Patient- and family-centered care and the pediatrician’s role. Pediatrics. 2012;129:394–404. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fochtman D, Foley GV, editors. Nursing care of the child with cancer. Boston, MA: Little, Brown; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner A, Kaplan B, Brown W, Krier-Morrow D, Rappaport S, Marcus L, … Aaronson D. National standards for asthma self-management education. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. 2015;114:178–186. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2014.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haugen MS, Landier W, Mandrell BN, Sullivan J, Schwartz C, Skeens MA, Hockenberry M. Educating families of children newly diagnosed with cancer: Insights of a Delphi panel of expert clinicians from the Children’s Oncology Group. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 2016 Jun 5; doi: 10.1177/1043454216652856. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hockenberry MJ, Coody DK, editors. Pediatric oncology and hematology: Perspectives on care. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J, Flaherty M. The nurse and cancer patient education. Seminars in Oncology. 1980;7:63–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelo M, Martikainen M, Eriksson E. Patient education of children and their families: Nurses’ experiences. Pediatric Nursing. 2013;39:71–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodish ED, Pentz RD, Noll RB, Ruccione K, Buckley J, Lange BJ. Informed consent in the Children’s Cancer Group: Results of preliminary research. Cancer. 1998;82:2467–2481. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980615)82:12<2467::aid-cncr22>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornburger C, Gibson C, Sadowski S, Maletta K, Klingbeil C. Using “teach-back” to promote a safe transition from hospital to home: An evidence-based approach to improving the discharge process. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2013;28:282–291. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotsubo C, Murphy K. Nurturing patient/family education through innovative COG resources. Paper presented at the Association of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology Nurses 35th Annual Conference and Exhibit; Anaheim, CA. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer RF, Perin G. Patient education and pediatric oncology. Nursing Clinics of North America. 1985;20:31–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landier W, Leonard M, Ruccione KS. Children’s Oncology Group’s 2013 blueprint for research: Nursing discipline. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2013;60:1031–1036. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerret SM, Weiss ME. How ready are they? Parents of pediatric solid organ transplant recipients and the transition from hospital to home following transplant. Pediatric Transplantation. 2011;15:606–616. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2011.01536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack JW, Grier HE. The day one talk. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22:563–566. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCalla JL, Santacroce SJ. Nursing support of the child with cancer. In: Pizzo PA, Poplack DG, editors. Principles and practice of pediatric oncology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott; 1989. pp. 939–956. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy K, editor. The Children’s Oncology Group family handbook for children with cancer. Arcadia, CA: Children’s Oncology Group; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- National Asthma Education Prevention Program. Expert panel report 3 (EPR-3): Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma-Summary Report 2007. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2007;120(5 Suppl):S94–S138. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MB, Guelcher C. Scope and standards of pediatric hematology/oncology nursing practice. Chicago, IL: Association of Pediatric Hematology Oncology Nurses; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary M, Krailo M, Anderson JR, Reaman GH. Progress in childhood cancer: 50 years of research collaboration, a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Seminars in Oncology. 2008;35:484–493. doi: 10.1053/j.seminon-col.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers CC, Laing CM, Herring RA, Tena N, Leonardelli A, Hockenberry M, Hendricks-Ferguson V. Understanding effective delivery of patient and family education in pediatric oncology: A systematic review from the Children’s Oncology Group. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 2016 doi: 10.1177/1043454216659449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers CC, Stegenga K, Withycombe J, Sachse K, Kelly KP. Processing information after a child’s cancer diagnosis: How parents learn: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. doi: 10.1177/1043454216668825. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiner B, Kolb LE, O’Brian CA, Carroll S, Lipman RD. National role delineation study of the Board Certification for Advanced Diabetes Management: Evidence-based support of the new test content outline. The Diabetes Educator. 2015;41:609–615. doi: 10.1177/0145721715599269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shochat SJ, Fremgen AM, Murphy SB, Hutchison C, Donaldson SS, Haase GM, … Winchester DP. Childhood cancer: Patterns of protocol participation in a national survey. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2001;51:119–130. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.51.2.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein J, Klingensmith G, Copeland K, Plotnick L, Kaufman F, Laffel L, … Clark N. Care of children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes: A statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:186–212. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.1.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slone JS, Self E, Friedman D, Heiman H. Disparities in pediatric oncology patient education and linguistic resources: Results of a national survey of pediatric oncologists. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2014;61:333–336. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward E, DeSantis C, Robbins A, Kohler B, Jemal A. Childhood and adolescent cancer statistics, 2014. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2014;64:83–103. doi: 10.3322/caac.21219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss M. Readiness for discharge in pediatric acute care. Paper presented at the Patient/Family Education in Pediatric Oncology, State of the Science Symposium; Dallas, TX. 2015. Oct 6, [Google Scholar]

- Weiss M, Johnson NL, Malin S, Jerofke T, Lang C, Sherburne E. Readiness for discharge in parents of hospitalized children. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2008;23:282–295. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Withycombe JS, Andam-Mejia R, Dwyer A, Slaven A, Windt K, Landier W. A comprehensive survey of institutional patient/family educational practices for newly diagnosed pediatric oncology patients: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 2016 Jun 9; doi: 10.1177/1043454216652857. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yawn BP, Buchanan GR, Afenyi-Annan AN, Ballas SK, Hassell KL, James AH, … John-Sowah J. Management of sickle cell disease: Summary of the 2014 evidence-based report by expert panel members. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2014;312:1033–1048. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.10517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]