Abstract

Many cancerous solid tumors metastasize to the bone and induce pain (cancer-induced bone pain, CIBP). CIBP is often severe due to enhanced inflammation, rapid bone degradation, and disease progression. Opioids are prescribed to manage this pain but may enhance bone loss and increase tumor proliferation, further compromising patient quality of life. Angiotensin-(1-7) (Ang-(1-7)) binds and activates the Mas receptor (MasR). Angiotensin-(1-7)/MasR activation modulates inflammatory signaling after acute tissue insult, yet no studies have investigated whether Ang-(1-7)/MasR play a role in CIBP. We hypothesized that Ang-(1-7) inhibits CIBP by targeting MasR in a murine model of breast CIBP. 66.1 breast cancer cells were implanted into the femur of BALB/cAnNHsd mice as a model of CIBP. Spontaneous and evoked pain behaviors were assessed before and after acute and chronic administration of Ang-(1-7). Tissues were collected from animals for ex vivo analyses of MasR expression, tumor burden, and bone integrity. Cancer inoculation increased spontaneous pain behaviors by day 7 that were significantly reduced after a single injection of Ang-(1-7) and after sustained administration. Pre-administration of A-779 a selective MasR antagonist, prevented this reduction, while pre-treatment with the AT2 antagonist had no effect; an AT1 antagonist enhanced the antinociceptive activity of Ang-(1-7) in CIBP. Repeated Ang-(1-7) administration did not significantly change tumor burden or bone remodeling. Data here suggest that Ang-(1-7)/MasR activation significantly attenuates CIBP while lacking many side effects seen with opioids. Thus, Ang-(1-7) may be an alternative therapeutic strategy for the nearly 90% of advanced stage cancer patients who experience excruciating pain.

Keywords: Angiotensin 1-7, MasR, breast, cancer, pain, chronic

Introduction

Bone pain is experienced by 75–90% of late-stage metastatic cancer patients [55]. Metastatic cancer-induced bone pain (CIBP) is frequently reported, but poorly managed [35]. The World Health Organization recommends mild-to-strong opioids for cancer pain [76] yet, opioid therapy is associated with several side effects contributing to their failure [48], while diversion of prescribed opioids have led to an addiction epidemic [4]. Recently, reports in humans [10; 14; 60] and animals [21; 72] suggest that opioids may exacerbate bone loss, which is counterproductive to anti-osteolytic co-therapies and CIBP management [16; 47; 66; 75]. Disturbingly, recent studies demonstrate an increase in the proliferation/migration of cancers with sustained opioids [15; 26; 38; 80], which is the exact condition CIBP patients’ experience. Such side effects impede anticancer therapy and diminish patient and family quality of life.

Preclinical modeling of CIBP has revealed mechanisms driving this complex disease state and lead to the identification of potential therapeutic targets [28; 63]. Although the bone is innervated by both sympathetic and nociceptive nerve fibers, many human tumors of the bone lack detectable nerve fibers within the tumor and adjacent peripheral bone [31; 42]. Contributors to nociceptive signaling associated with CIBP include an acidic tumor environment and the secretion of growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines from the tumor and tumor-associated cells, as well as enhanced nerve sprouting in the local environment [28; 36; 39; 59].

The renin-angiotensin system (RAS), well known for roles in blood pressure regulation and fluid homeostasis, was recently implicated in metastatic bone disease including inflammation, angiogenesis, tumor cell proliferation, and migration [45; 61]. Angiotensin II (Ang II) is the major end product of the RAS and activates two GPCRs: angiotensin II receptor type 1 (AT1) and type 2 (AT2) [17]. Physiological effects such as vasoconstriction, inflammation, fibrosis, cellular growth/migration, and fluid retention are reported for AT1 and AT2 [33]. Ang II is cleaved by ACE2 to yield Angiotensin-(1-7) (Ang-(1-7)), a biologically active heptapeptide. In contrast to Ang II, Ang-(1-7) binds to the GPCR, Mas receptor (MasR; Kd=0.83nM) with 60–100 fold greater selectivity over the AT1 and AT2 receptors [11; 58]. Activation of the MasR elicits effects opposite to those of the Ang II/AT1/AT2 axis including anti-inflammation [45; 57; 58].

MasR is expressed throughout the central and peripheral nervous systems including the dorsal root ganglion and spinal cord [9; 41; 70]. In a model of prostaglandin-induced hyperalgesia, Ang-(1-7) dose-dependently attenuated peripheral nociception independent from opioid receptors [9; 41]. Ang-(1-7) via MasR reportedly reduces pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-6 while increasing the expression of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 resulting in decreases of PI3K, MAPKs, and JNK signaling in multiple pain models [25; 43; 67; 68]. Yet, no reports have investigated the efficacy of Ang-(1-7) in clinically relevant cancer pain models, measured bone integrity or measured tumor burden after sustained administration. Given the efficacy of Ang-(1-7) in inflammatory pain states, we hypothesized Ang-(1-7) decreases CIBP following acute and chronic administration by targeting MasR in the DRGs and femur extrudate.

Materials and Methods

In vitro

Cell culture

A murine (female BALB/cfC3H) mammary adenocarcinoma line, 66.1, was a kind gift from Dr. Amy M Fulton[74]. Cells were cultured in Eagle’s minimum essential medium with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 IU−1 penicillin, and 100 μg mL−1 streptomycin (P/S). The 66.1 cells were plated in T-75 tissue culture flasks, allowed to grow exponentially in an incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2. The viability of cells cultured with treatments described below was measured using the XTT assay (ATCC, Manassas, VA).

In vivo

Animals

All procedures were approved by the University of Arizona Animal Care and Use Committee and conform to the Guidelines by the National Institutes of Health and the International Association for the Study of Pain. Female BALB/cAnNHsd mice (Harlan, IN, USA) between 15 and 20g were used in this study. Mice were housed in a climate control room on a 12-hour light/dark cycle and allowed food and water ad libitum. Animals were monitored on days 0, 7, 10, and 14 of the study for clinical signs of rapid weight loss and signs of distress.

Drug Treatment

Animals received Angiotensin-(1-7) (Tocris, Ellisville, MO), the MasR antagonist A-779 (abcam, Cambridge, MA), the AT1 antagonist Losartan potassium (Tocris Bioscience, Minneapolis, MN), or the AT2 antagonist PD 123319 ditrifluoroacetate (Tocris Bioscience, Minneapolis, MN) dissolved in 0.9% saline. All intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections were made at a volume of 10 mL/kg. Systemic doses as follows: Ang-(1-7) = 0–100 μg/kg, A-779 = 0.19 μg/kg, Losartan potassium = 0.4 mg/kg, PD 123319 ditrifluoroacetate = 0.4 mg/kg. In antagonist studies, A-779, Losartan potassium, or PD 123319 ditrifluoroacetate was administered 30 minutes prior to Ang-(1-7).

Tail Flick

A warm water (52°C) tail flick test was used to determine the effects of Ang-(1-7) on acute nociception. The distal third of the tails of naïve mice were submerged into the water bath. The withdraw latency, defined as the time for the tail to be withdrawn from the water bath, was recorded. A cutoff time of 10 seconds was enforced to prevent tissue damage. Baseline latencies were recorded prior to drug administration. Animals were dosed (i.p.) with Ang-(1-7) (0–100 μg/kg). Tail flick latencies were reassessed 15, 30, 60, 90, 120, 150, and 180 minutes post-treatment.

Rotarod

A rotarod performance test was used to determine the motor and/or sedative effects of Ang-(1-7) (Rotamex 4/8, Columbus Instruments, Columbus, Ohio, USA). Three days prior to testing, naïve mice were subjected to 5 trials in which they were able to acclimate to the rotating rod (10 revolutions/min [71]). On the day of testing, animals were allowed one trial and then baselined. The amount of time the animal remained on the rod was recorded, with a cutoff time of 120 seconds to prevent exhaustion. Animals were dosed (i.p.) as previously described and reevaluated 15, 30, 60, and 120 minutes post-administration.

Arthrotomy: Intramedullary implantation of 66.1 cells

To induce CIBP, an arthrotomy was performed, as previously described [28]. Briefly, animals were anesthetized with 80 mg/kg ketamine - 12mg/kg xylazine (in a 10 mL/kg volume). The surgical area was shaved and cleaned with 70% ethanol and betadine. The condyles of the right femur were exposed and a burr-hole (0.66 mm) was drilled to create a space for the 66.1 cell inoculation. A 5 μl volume of 66.1 cells (8,000 cells per 1 μl) in MEM (or 5 μl MEM without cells in sham animals) was injected into the intramedullary space of the mouse femora. Proper placement of the injector was confirmed by radiograph (Faxitron X-ray imaging). Holes were sealed with bone cement and the patella reset. Muscle and skin were closed in separate layers with 5-0 vicryl suture and wound autoclips, respectively. Animals were given 8mg/kg (10mL/kg volume) gentamicin to prevent infection. Staples were removed 7 days post-surgery.

Acute Behavioral Testing

Fourteen days post-surgery, baseline behaviors of spontaneous flinching/guarding were recorded. Flinching was characterized by the lifting and rapid flexing of the hind paw ipsilateral to femoral inoculation when not associated with walking or other movement. Guarding was characterized by the lifting the inoculated hind limb into a fully retracted position under the torso. Both flinching and guarding of the inoculated limb are accurate measurements of ongoing pain and is similar to what is observed clinically in bone cancer patients who hold or move their cancer-bearing limb away from sensory stimuli[30; 54]. The total number of flinches and the time spent guarding 2 min duration was recorded. Mice were then separated into treatment groups and dosed systemically with Ang-(1-7) (0–10 μg/kg, i.p.), A-779 (0.19 μg/kg, i.p.), Losartan potassium (0.4 mg/kg, i.p.), PD 123319 (0.4 mg/kg, i.p,) [44], vehicle (0.9% saline, i.p.), or a combination of Ang(1-7) and each antagonist. Antagonists were administered 30 minutes prior to Ang-(1-7). Following administration, animals were tested at over a three-hour time course until their pain behaviors returned to baseline.

Chronic Behavioral Testing

Seven days post-surgery, baseline behaviors of spontaneous pain, as described above, were recorded. Mice were treated (i.p.) with Ang-(1-7) (0.058 μg/kg), A-779 (0.19 μg/kg), vehicle (0.9% saline), or a combination. Antagonist was administered 30 minutes prior to Ang-(1-7). Animals were dosed at the same time each day 7 to 14 days post-surgery. On day 10, pain behaviors were assessed 15 minutes following treatment, based on the time of peak effect determined by the acute studies. Fourteen days post-surgery, behaviors were again recorded pre- and post-treatment. Animals were sacrificed following treatment and testing on the fourteenth day post-surgery, and the following tissues were collected for biochemical analyses: serum, femur extrudate, and lumbar dorsal root ganglia.

Mechanical Hypersensitivity

The assessment of mechanical hypersensitivity was determined by measuring the withdrawal threshold of the paw ipsilateral to the site of nerve injury in response to probing with a series of calibrated von Frey filaments (.04–4.0g). Prior to femur innoculation, female mice were tested for pre-injury baseline mechanical sensitivity. Filaments were applied perpendicularly to the plantar surface of the right hindpaw of mice while in individual plexiglass chambers suspended on a wire-mesh. Animal’s mechanical threshold was reassessed 7 days post femur inoculation with either media containing 66.1 cells or media only for a new injury-induced baseline. To determine whether Ang-(1-7) attenuates CIBP, Animal’s mechanical threshold was reassessed on days 7, 10 and 14 (post-femur inoculation) 30 min after Ang-(1-7) or vehicle administration. The withdrawal threshold was determined by sequentially increasing and decreasing the stimulus strength (‘up–down’ method) analyzed using a Dixon non-parametric test [34] and expressed as the mean withdrawal threshold. Animals mechanical threshold were then assessed.

Nesting

Nesting behaviors of naïve, media, and cancer-inoculated mice were assessed using the protocol described by Negus et al. [40]. Animals were acclimated to individual cages, without an existing nest, for 30 minutes prior to drug administration. Cotton fiber nestlets were cut into 6 equal pieces, and each piece was placed in the cage in 6 zones in the manner previously described following drug administration. Throughout the duration of the 100-minute time course, the number of cleared zones was recorded; upon completion the height (mm) of each fluffed nestlet was measured.

Ex Vivo

Western Blot Analysis

Dorsal root ganglia (DRG) and femur extrudates from mice used in behavioral studies were analyzed for expression of MasR. DRGs were homogenized in modified radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer with protease inhibitor cocktail and EDTA (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) via sonication. 10 μg of each sample was resolved on a 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gels (TGX Criterion XT; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (PVDF, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Ipsilateral and contralateral femurs were removed from each animal. For each femur, the proximal and distal ends were clipped and the intramedullary extrudate was flushed six times with 700 μL phosphate-buffered saline containing protease inhibitor cocktail and EDTA (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Femur marrow from five animals was pooled per sample and 15 μg of sample was resolved and transferred in the same manner as DRGs. Protein transfer was verified by staining blots with Ponceau S (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), and PVDF membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% (v/v) Tween-20 (TBST) for one hour at room temperature. Membranes were then incubated with primary antibody: rabbit polyclonal anti-Angiotensin-(1-7) Mas Receptor (Alomone Labs AAR-013; 1:200 dilution for DRGs or 1:800 for femurs) or mouse monoclonal anti-actin AC40 (Cell Signaling 7076S; 1:4,000 dilution) in 1% milk in TBST overnight at 4°C. The membranes were washed in TBST and incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies (Cell Signaling 7074 Anti-rabbit IgG HRP-Linked, 1:10,000 dilution; Cell Signaling 7076 Anti-mouse IgG HRP-Linked, 1:5000 dilution) for 1 hour at room temperature. Membranes were again washed and developed using enhanced chemiluminescence (Clarity ECL Substrate, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), and bands were detected using GeneMate Blue-Ultra Autorad films (BioExpress, Kaysville, UT. Bands were quantitated and corrected for background using ImageJ densitometric software (Wayne Rasband, Research Services Branch, National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, MD). All data were normalized to actin in each lane and reported as fold change over untreated control.

Data Analysis and Statistical Procedures

Behavioral

Statistical significance between treatment groups for the dose response curve in acute behavioral studies was determined by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s t test for unpaired experimental data. Statistical significance between treatment groups for chronic behavioral studies was determined using two-way ANOVA and Tukey’s t test for multiple comparisons. Data are reported as mean ± S.E.M. for n = 8–12 mice/treatment group. Power analyses were performed on cumulated data by using GPower3.1 software to estimate the optimal numbers required. We found that adequate statistical separation requires the group size of 8–12 per behavioral test) to detect differences (80%) between the drugs and control groups at alpha < 0.05. Experimenter was blinded to drug vs. vehicle treatments.

Ex vivo

Western blot data are reported as a mean ± SEM from 3–5 groups of n = 3–5 animals. Statistical significance between treatment groups for the CTX, radiograph, and H&E data were determined by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s t test for unpaired experimental data. CTX data are reported as mean ± S.E.M. for n = 4 mice/treatment group. Radiograph data are reported as mean ± S.E.M. for n = 5–11 mice/treatment group. H&E data are reported as mean ± S.E.M. for n = 3–5 mice/treatment group.

General

Power analyses were conducted based on the pilot data and historical data using G*Power3.1 software in order to efficiently detect significant differences among groups. Effect size was estimated from the data obtained from our historical studies. An a priori computation for one-way ANOVA was used to estimate size given alpha = 0.05 and power set to 1-beta=0.95. A value of p < 0.05 was accepted as statistically significant. Statistical analyses were run and plots generated in GraphPad Prism 5.0 (Graph Pad Inc., San Diego, CA).

Results

Ang-(1-7) administration in established CIBP attenuates spontaneous and evoked pain

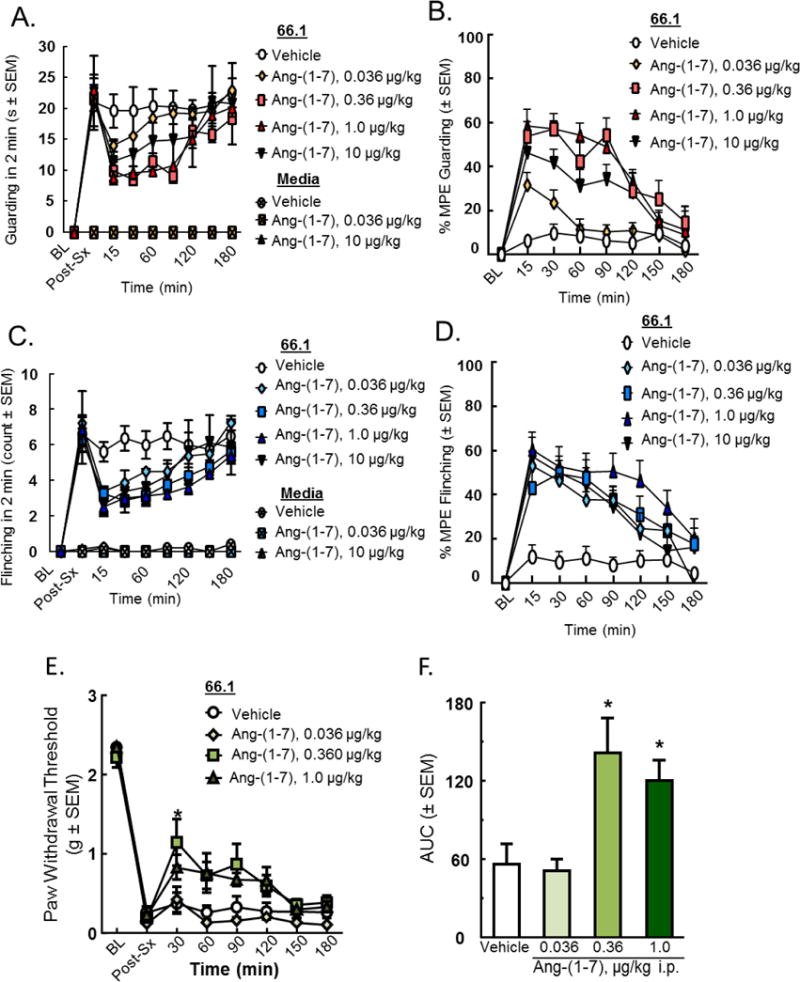

We assessed the antinociceptive efficacy of Ang-(1-7) in a model of established CIBP in which 66.1 tumor cells were injected into the right femurs of syngeneic BALB/cAnNHsd mice. Prior to surgery, mice did not display behavioral signs of pain, yet 14 days post-cancer inoculation surgery, animals present with a significant amount of flinching and guarding compared to media-treated controls (p < 0.0001, n=8) (Fig. 1A, C). A single systemic injection of Ang-(1-7) (0.036, 0.360, 1, and 10 μg/kg) or vehicle was administered, and pain behaviors were assessed. Animals given an acute i.p. administration of Ang-(1-7) showed a significant (p < 0.01, n=8) reduction in spontaneous pain behaviors with an onset 15 min after injection of either 0.36 or 1μg/kg which persisted for nearly 2 hours (Fig. 1A, C). Dose response curves were constructed from data collected at the time of peak effect, 15 min (Fig. 1B, D). At 15 min, the maximum effect of Ang-(1-7) in reducing guarding behavior was 52.75% (p < 0.01, n=8) with a corresponding A90 dose of 0.058 μg/kg (Fig. 1B). Flinching displayed less of a dose-dependency and a more significant inhibition at the lower dose (0.036 μg/kg). Thus, a single injection of Ang-(1-7) is effective in reducing spontaneous pain behavior by more than 50% in animals with established CIBP.

Figure 1. Ang-(1-7) administration in established CIBP attenuates spontaneous pain.

Spontaneous pain behaviors (A) guarding and (C) flinching were recorded in a two-minute period 14 days post-inoculation and at various time points after drug administration. Time of peak effect at 15 minutes post-administration (p < 0.01 for 0.36 and 1 μg/kg, compared to saline) lasting for two hours. (B) Emax= 52.75%, A90= 0.058 μg/kg for the guarding curve, (D) A90= 1 μg/kg for the flinching curve. Tactile allodynia was measured 14 days post-inoculation and at various time points after drug administration; a significant (p < 0.05, n=8) reduction in evoked pain behaviors with an onset 30 min was measured after injection of 0.360 and 1 μg/kg and persisted for nearly 2 hours (E). Area under the curve was calculated (F). Values represent the mean ± standard error of the mean, n=8 per group.

Furthermore, mechanical hypersensitivity was measured via the use of vonFrey filaments. Prior to femur inoculation surgery, animals displayed the highest level of paw withdrawal threshold measurable by the filaments; however, this threshold was significantly reduced 14 days post-femur inoculation (Fig. 1E). For acute testing, a single systemic injection of Ang-(1-7) or vehicle was administered, and pain behaviors were assessed at 30 minute intervals post-injection (Fig. 1E). Animals given an acute i.p. administration of Ang-(1-7) showed a significant (*p < 0.05, n=8) reduction in evoked pain behaviors with an onset 30 min after injection of either 0.360 and 1 μg/kg which persisted for nearly 2 hours (Fig. 1E). Area under the curve was calculated at time of peak effect (30 min post-administration), (*p < 0.05, n=8) (Fig. 1F). Together, these data suggest that one-time administration of Ang-(1-7) reduces both spontaneous and evoked pain responses in established CIBP.

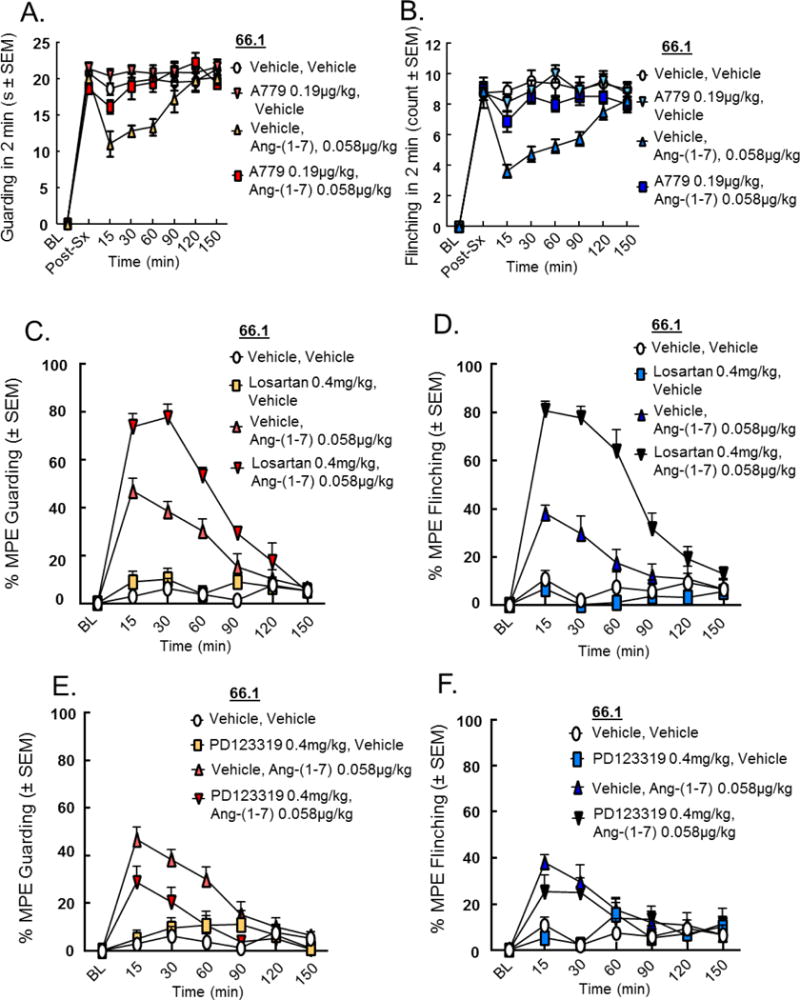

Effects of MasR/AT1/AT2 antagonists on Ang-(1-7) antinociception in established CIBP

To investigate the receptor dependence of Ang-(1-7), A-779 (0.19 μg/kg), the selective MasR antagonist, or vehicle was administered 30 minutes prior to Ang-(1-7) (0.058 μg/kg) 14 days post-femur inoculation. Spontaneous pain behaviors of flinching and guarding were recorded 15, 30, 60, 90, 120, and 150 minutes post-administration until animal’s pain behaviors returned to baseline, after 150 minutes. Inhibition of MasR with A-779 alone did not alter spontaneous or evoked pain thresholds; however, pretreatment with A-779 significantly inhibited Ang-(1-7) attenuation of guarding (Fig. 2A, p < 0.01) and flinching (Fig. 2B, p < 0.001). These data suggest Ang-(1-7) elicits antinociception in established CIBP through actions at MasR.

Figure 2. Effects of MasR/AT1/AT2 antagonists on Ang-(1-7) antinociception in established CIBP.

Spontaneous pain behaviors (A, C, E) guarding and (B, D, F) flinching were recorded as previously described. A-779 (A, B), Losartan (C, D) and PD 123319 (E, F) did not significantly alter spontaneous pain behaviors when administered alone. Administration of A-779 (0.19 μg/kg, i.p.) 30 minutes prior to Ang-(1-7) completely reversed the effects of Ang-(1-7) on (A) guarding and (B) flinching in the CIBP model, suggesting the Ang-(1-7) works at MasR to reduce CIBP. Losartan potassium (0.4 mg/kg, i.p.), administered 30 minutes prior to Ang-(1-7), yielded a 77.527% MPE in reducing guarding (p < 0.0001) 30 minutes post-administration (C) and an 80.563% reduction in flinching (p < 0.0001) 15 minutes post-administration (D). Use of PD 123319 (0.4 mg/kg, i.p.) 30 minutes prior to Ang-(1-7) did not alter guarding or flinching of animals with established CIBP (E, F) as compared to the animal group treated with solely Ang-(1-7). Values represent the mean ± standard error of the mean, n=7-8 per group.

Since Ang II is the precursor molecule to Ang-(1-7), we next investigated whether the effects of Ang-(1-7) in animals with established CIBP were mediated by the Ang II receptors. Pre-treatment with selective antagonists to AT1 and AT2, Losartan potassium (Ki = 10 nM [6]) and PD 123319 (also known as EMA200) (IC50 = 34 nM [5]), respectively was performed before Ang-(1-7) administration. Animals were inoculated with 66.1 cells or media, as previously described, and pain behaviors were assessed 14 days post-femur inoculation. Mice received either the AT1 or AT2 antagonist (0.4 mg/kg, i.p.) 30 minutes prior to Ang-(1-7) (0.058 μg/kg, i.p.), or vehicle (0.9% saline). In accordance with the above study, Ang-(1-7) administration alone reduced pain behaviors (p < 0.01, n=7), while neither Losartan potassium nor PD 123319 significantly altered pain behaviors when administered on their own. Interestingly, administration of the AT1 receptor antagonist, Losartan potassium, prior to Ang-(1-7) yielded a 77.527% maximal possible efficacy (MPE) in reducing guarding (p < 0.0001, n=7) 30 minutes post-administration (Fig. 2C) and an 80.56% MPE in reducing flinching (p < 0.0001, n=7) 15 minutes post-administration (Fig. 2D). However, use of the AT2 antagonist, PD 123319, prior to Ang-(1-7) did not further increase nor decrease guarding or flinching of animals with established CIBP (Fig. 2E, F) as compared to the animal group treated with solely Ang-(1-7). Together, these data suggest the actions of Ang-(1-7) in reducing CIBP are mediated largely through MasR, with some action through the AT1 receptor.

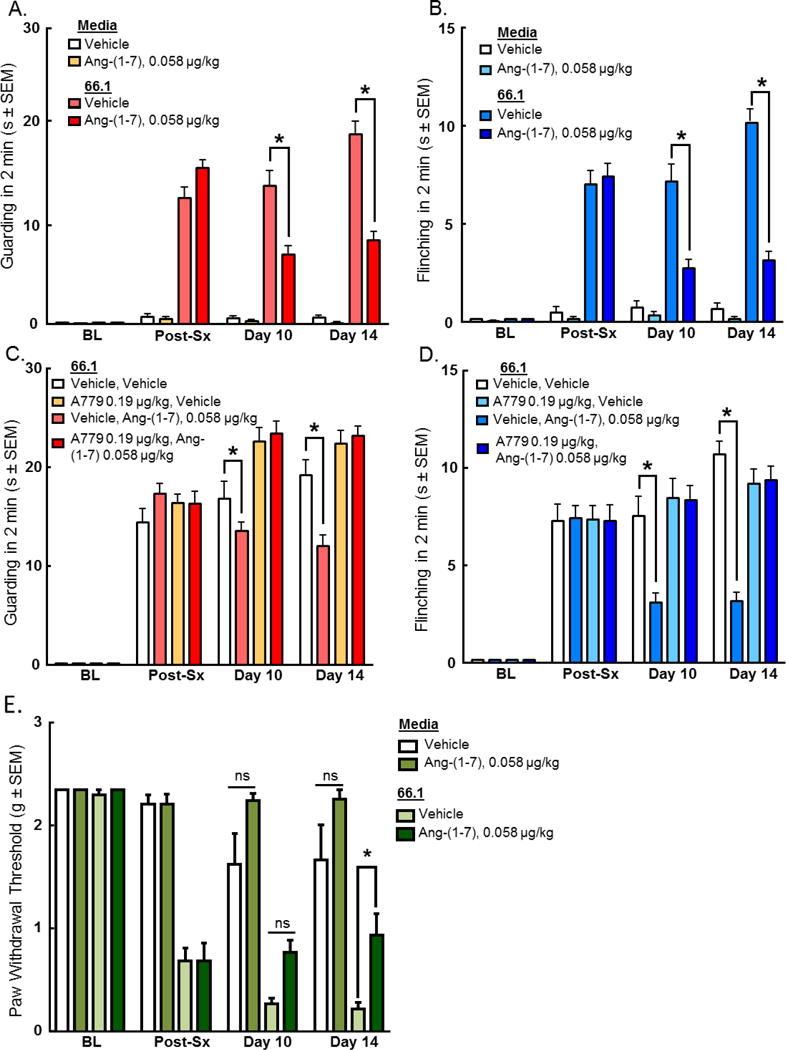

Antinociceptive effects of Ang-(1-7) through MasR are maintained after repeated administration

Because sustained administration of many analgesics can lead to the development of tolerance, we examined whether Ang-(1-7) retained antinociceptive activity against CIBP after repeated administration. Ang-(1-7) (0.058 μg/kg, i.p.) was administered daily, beginning 7 days post implantation of 66.1 cells into the femur. Mice were evaluated for CIBP spontaneous pain behaviors on day 7 prior to drug administration, and on days 10 and 14 post-surgery 15 minutes post-treatment. Cancer inoculation significantly increased the amount of time spent guarding and number of flinches 7 days post-surgery (p < 0.0001, n=12). Animals experienced significant (p < 0.0001, n=12) reduction in guarding (Fig. 3A) and flinching (Fig. 3B) following Ang-(1-7) treatment on days 10 and 14 post-surgery. Vehicle treatment had no significant effect.

Figure 3. Antinociceptive effects of Ang-(1-7) through MasR are maintained after repeated administration.

Spontaneous pain behaviors (A) guarding and (B) flinching were recorded in a two minute period pre-surgery, post-surgery (7 days post inoculation), and after drug administration on days 10 and 14. Daily administration of Ang-(1-7) (0.058 μg/kg, i.p.) significantly reduced spontaneous pain behaviors associated with CIBP (p < 0.0001). Furthermore, tactile allodynia was recorded pre-surgery, post-surgery (7 days post inoculation), and after drug administration on days 10 and 14. Cancer inoculation significantly reduced paw withdrawal thresholds 7 days post-surgery (p < 0.05 n=12). To investigate receptor dependence, animals were dosed days 7-14 post-surgery with A-779 (0.19 μg/kg, i.p.) 30 minutes prior to administration of Ang-(1-7). Spontaneous pain behaviors (C) guarding and (D) flinching were recorded as previously described. Daily administration of A-779 reversed the effects of Ang-(1-7) in the CIBP model. Animals experienced significant (p < 0.05, n=12 increase in paw withdrawal threshold (E) following Ang-(1-7) treatment on day 14 post-surgery. Values represent the mean ± standard error of the mean, n=12 per group.

Additionally, sustained administration of Ang-(1-7) (0.058 μg/kg, i.p.) had a similar effect on evoked pain response. Cancer inoculation significantly reduced paw withdrawal thresholds 7 days post-surgery (p < 0.05, n=12). Animals experienced significant (p < 0.05, n=12) increase in paw withdrawal threshold (Fig. 3E) following Ang-(1-7) treatment on day 14 post-surgery but did not achieve significance on day 10. Vehicle treatment had no significant effect. Together, these data suggest that sustained administration of Ang-(1-7) reduces both spontaneous and evoked pain responses in established CIBP on day 14.

To determine whether MasR continued to underlie actions of Ang-(1-7) after repeated dosing, A-779 (0.19 μg/kg) was administered 30 minutes prior to Ang-(1-7) (0.058 μg/kg) daily 7–14 days post-cancer inoculation (Fig. 3C, D). Administration of A-779 alone had neither a pro- or anti-nociceptive effect on the mice, and similar to our observations after a single injection, the chronic pre-treatment with A779 before Ang-(1-7) prevented attenuation of CIBP by the latter. Together, these data suggest the reduction in pain behaviors associated with CIBP by repeated dosing of Ang-(1-7) is mediated through MasR.

Ang-(1-7) administration in established CIBP does not change nesting behaviors

Nesting, an innate behavior in mice, has been shown to be hindered by various states of pain [40]. Thus, we evaluated the effects of both the arthrotomy and administration of Ang-(1-7) on nesting behavior. Six equally sized pieces of nestlet were placed into 6 zones of the animals’ individual cages. The number of zones that the animals cleared of the nestlet pieces was recorded over the 100-minute time course (Fig. 4A). During the first hour of the study, the 66.1-inoculated animals, day 6 post-surgery, cleared significantly fewer zones than the naïve animals (p < 0.05). After the second hour of the study, the media animals cleared fewer zones than both the naïve and 66.1-inoculated animals (p < 0.05). A second study was conducted in which 66.1-inoculated animals, day 15 post-surgery, were treated with Ang-(1-7) (0.058 μg/kg, i.p.) or vehicle (0.9% saline) (Fig. 4B). The nesting behaviors of both treated cancerous groups did not differ significantly from the naïve group. However, at both the 75 and 90-minute time points, the media animals cleared fewer zones than the other groups (p < 0.05). These data demonstrate that while the nesting of animals with established CIBP alters the nesting behaviors of mice, Ang-(1-7) administration does not further alter these behaviors.

Figure 4. Ang-(1-7) administration in established CIBP does not change nesting behaviors.

Nesting, an innate behavior of mice, was studied. During the first hour of the study, the 66.1-inoculated animals, day 6 post-surgery, cleared significantly (p < 0.05) fewer zones than naïve animals (A). After the second hour of the study, the media animals cleared fewer zones than both the naïve and 66.1-inoculated animals (p < 0.05). A second study was conducted in which 66.1-inoculated animals, day 15 post-surgery, were treated with Ang-(1-7) (0.058 μg/kg, i.p.) or vehicle (0.9% saline) (B). The nesting behaviors of both cancerous groups did not differ significantly from the naïve group. At both 75 and 90-minute time points, media animals cleared fewer zones than the other three groups (p < 0.05). Values represent the mean ± standard error of the mean, n=8 per group.

Ang-(1-7) administration results in antinociception but not motor impairment in naïve mice

Previous studies have indicated that Ang-(1-7) has limited antinociceptive efficacy in non-injured animals after peripheral administration using a mechanical force test to the hindpaw [8]. We administered Ang-(1-7) systemically (0.360, 1, 10 μg/kg, i.p.) in naïve mice and observed a small but significant increase in thermal tail flick latencies. Ang-(1-7) effects peaked between 15 and 30 min post administration with 1 μg/kg Ang-(1-7) (MPE = 27.8%, p<0.001) and 10 μg/kg Ang-(1-7) (MPE = 20.2%, p<0.01) that returned to baseline between 90 to 120 min.

To exclude the possibility that Ang-(1-7) administration reduced mobility in order to increase tail withdraw latency, rotarod testing was performed. Naïve animals were trained to walk on a rotating rod for 2 min. After training, mice were injected with Ang-(1-7) by either spinal (0.3 pmol/5μL) or systemic routes (0.058 and 10 μg/kg). No significant differences in rotarod latencies were observed between vehicle and Ang-(1-7) treated mice (results not shown; p = 0.99 i.t.; p = 0.18 i.p.). Together, these data suggest that systemic Ang-(1-7) is antinociceptive after a single administration without noticeable impact on motility.

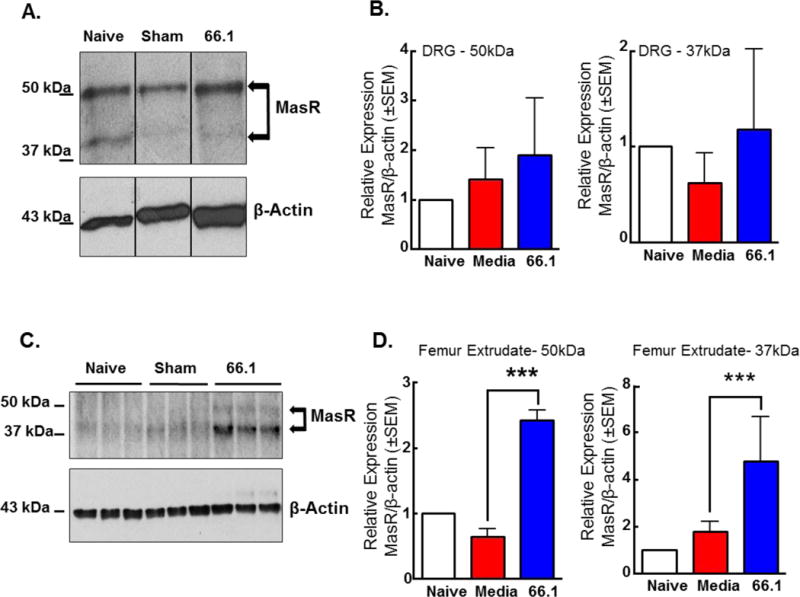

MasR is expressed in the dorsal root ganglion and femur extrudate

Our findings that Ang-(1-7)/MasR alleviates CIBP suggest MasR is expressed within pain pathways and within the bone tumor microenvironment. We collected the ipsilateral lumbar dorsal root ganglion (DRG) and femur extrudate from naive, sham, cancer (66.1), and 66.1 Ang-(1-7) treated mice. In naïve BALB/cAnNHsd mice, MasR is expressed in the dorsal root ganglia (Fig. 5A); MasR bands were observed at ~50 kDa and ~40 kDa. Sham surgery (i.e. media only) did not significantly alter MasR expression levels in the DRGs. Introduction of the murine mammary adenocarcinoma line 66.1 into the femoral intramedullary space did not significantly alter MasR expression in ipsilateral DRGs. MasR was also found to be expressed in the femur extrudates of the same mice (Fig. 5C) and cancer inoculation significantly increased the expression of MasR in the femur extrudate at both ~50 kDa and ~40 kDa (p < 0.001 compared to sham group), while sham surgery did not significantly alter the expression of MasR in the femur extrudate as compared to the naïve animal group (Fig. 5D).

Figure 5. MasR is expressed in the dorsal root ganglion and femur extrudate.

(A) Ipsilateral DRGs were harvested from naïve, sham (media inoculated) or chronically-treated 66.1 inoculated mice, homogenized, and probed for MasR expression via Western blotting. MasR is expressed in the dorsal root ganglia; MasR bands were observed at ~50 kDa and ~40 kDa (B). Sham surgery (i.e. media only) did not alter MasR expression levels in the DRGs. 66.1-inoculation increased the expression of MasR in the ipsilateral DRGs, though not statistically significant. β-actin serves as the loading control. (Pools of DRGs from n=3–5 animals) (C) Ipsilateral bone marrow extrudate was harvested from naïve, sham (media-inoculated), or cancer-inoculated mice and probed for MasR expression via Western blotting. MasR is expressed in the femur extrudates of mice. MasR bands were observed at ~50 kDa and ~40 kDa. (D) Sham surgery (i.e., media only) did not alter MasR expression levels at ~40 kDa or ~50 kDa in the femur extrudate. 66.1-inoculation significantly increased (p < 0.001) the expression of MasR in the ipsilateral femur extrudate. β-actin serves as the loading control. (Pools of femur extrudate from n=3–5 mice)

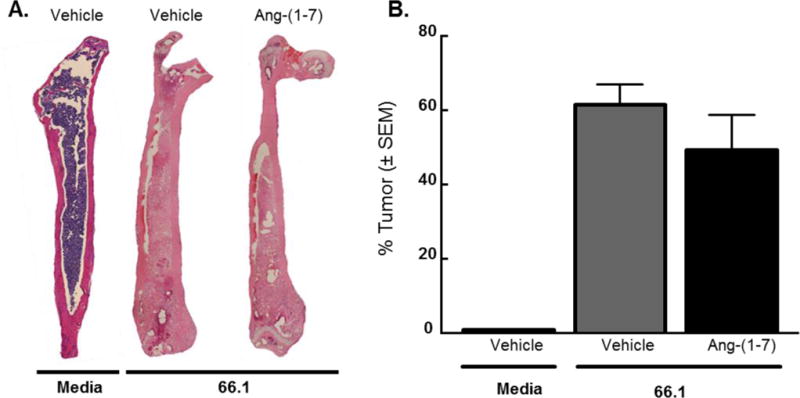

Repeated dosing of Ang-(1-7) does not alter tumor burden of mice with established CIBP or alter cell viability in vitro

To determine if repeated Ang-(1-7) administration altered tumor burden in mice with established CIBP as a means of reducing the pain behaviors associated with the disease. Following chronic administration studies, femurs were harvested from animals, decalcified, and embedded in paraffin blocks prior to sectioning (5 micron) and hemotoxylin/eosin staining (Fig. 6A). The region of the bone containing cancer cells was quantified as a measure of total intramedullary content and represented as a percent of the entire cells within the bone. Repeated Ang-(1-7) administration did not significantly increase nor decrease the percent tumor of the bone (p = 0.3, n=3–5) as compared to the saline-treated group (Fig. 6B). Thus, repeated Ang-(1-7) administration did not significantly impact tumor burden within the femur.

Figure 6. Repeated dosing of Ang-(1-7) does not alter tumor burden of mice with established CIBP.

(A) Femurs were harvested from animals and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Area of the bone containing cancer cells was quantified and presented as a % tumor of the whole bone. (B) Repeated Ang-(1-7) administration did not significantly reduce the percent tumor of the bone (p = 0.3) compared to saline-treated group. Values represent the mean ± standard error of the mean, n=5–11 per group.

To verify in vivo findings, we assessed Ang-(1-7) effects on 66.1 cell viability in vitro. 66.1 cells were treated with vehicle, or increasing concentrations of Ang-(1-7) (1, 10, 100, or 1000 ng) for 24 hr and an XTT cell viability assay was performed. As compared to vehicle treated cells (relative absorbance (RA ± SD) = 1.02± 0.09), each of the four Ang-(1-7) treatments did not significantly change cell viability (1 ng: 0.93 ± 0.11; 10 ng: 0.93 ± 0.07; 100 ng: 0.78 ± 0.11, 1000 ng: 0.93 ± 0.13). Together, these data indicate that Ang-(1-7) at the doses/concentrations tested neither promotes cell proliferation nor causes cell death both in vivo and in vitro.

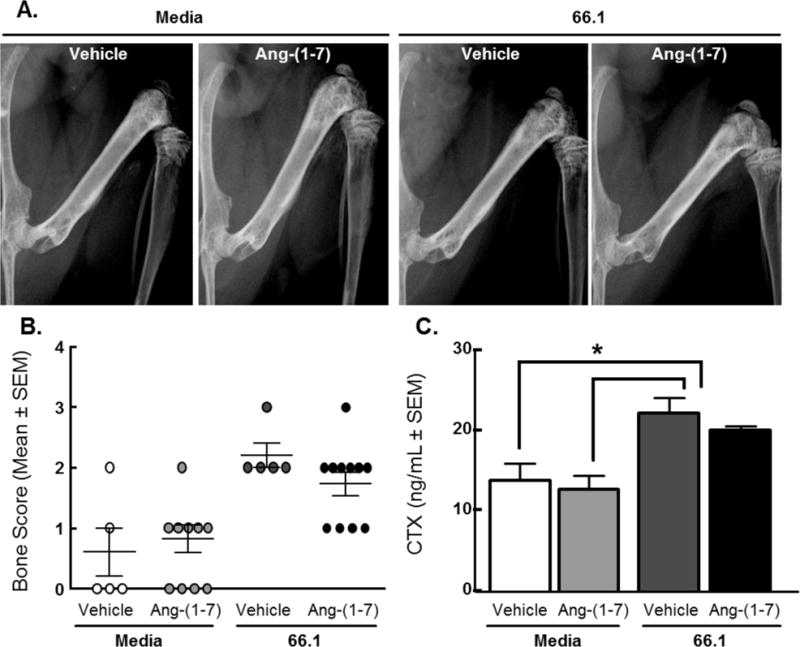

Repeated dosing of Ang-(1-7) does not affect bone remodeling of mice with established CIBP

Radiographic images of all chronically treated animals were taken on day 0, 7, 10, and 14 post-surgery to determine whether repeated Ang-(1-7) administration affected bone remodeling in mice with established CIBP (Fig. 7A). Day 14 images were scored by three blinded observers with the following scale (Fig. 7B): 0 – healthy bone, 1 – 1–3 lesions; 2 – 4–6 lesions; 3 – unicortical fracture; 4 – bicortical fractures. A healthy bone was defined as one without any visible lesions or fractures, and a lesion was defined as a dark hole-like spot below the epiphyseal plate. While no animals experienced bicortical fractures, both saline and Ang-(1-7)-treated cancer-inoculated animals experienced unicortical fractures. Media animals (7 out of 16) received scores of 0. As another marker of bone remodeling, levels of carboxy-terminal collagen crosslinks (CTX) in the serum were quantified (Fig. 7C). While cancer-inoculation significantly increased (p < 0.05, n=3–4) CTX levels in the bone compared to both media controls, Ang-(1-7) repeated administration did not significantly alter CTX levels compared to the 66.1 saline treated group. Overall, daily Ang-(1-7) administration in mice with established CIBP did not significantly influence bone remodeling of the ipsilateral femur.

Figure 7. Repeated dosing of Ang-(1-7) does not affect bone remodeling of mice with established CIBP.

(A) Representative day 14 radiographs of chronically treated animals. (B) Day 14 images were scored by three blinded observers with the following scale: 0 – healthy bone, 1 – 1–3 lesions, 2 – 4–6 lesions, 3 – unicortical fracture, 4 – bicortical fractures. Both saline and Ang-(1-7)-treated cancerous animals experienced unicortical fractures. (C) Levels of carboxy-terminal collagen crosslinks (CTX) in the serum were quantified as another measure of bone remodeling. While cancer-inoculation significantly increased (p < 0.05) CTX levels in the bone compared to both media controls. Ang-(1-7) repeated administration did not significantly alter CTX levels compared to the 66.1, saline treated group.

Discussion

The renin-angiotensin system, widely known for roles in blood pressure and fluid homeostasis, was recently implicated in several facets of metastatic bone disease including inflammation, angiogenesis, tumor cell proliferation and migration [45; 61]. The AT1 and AT2 receptors are reportedly on nociceptive cells of the dorsal root ganglia and are speculated as playing a role in pain [3; 46; 78] yet, the expression of the AT2 receptors on the DRGs of mice TRPV1-lineage neurons using RNA-Seq transcriptome analysis demonstrated minimal expression [13]. RNA-Seq analysis of the Mas1 receptor demonstrated a low amount in the rat and mouse DRG with a high expression in the hindpaw [13] supporting the response seen in these bone cancer studies. More importantly, the AT2 selective and orally active receptor antagonist EMA401, demonstrated clinical efficacy in a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of patients with postherpetic neuralgia [51]. A similar AT2 selective antagonist has demonstrated significant analgesic activity in a rat model of neuropathic pain [64; 65] and a preclinical model of prostate cancer bone pain by an indirect mechanism of inhibiting NGF-TrkA in the DRGs of fibers that innervate the cancer inoculated tibia [37]. In part, the inhibition by EMA401 of endogenous angiotensin II acting at AT2 receptors resulting in the inhibition of pain suggests endogenous angiotensin would further be metabolized to the Ang-(1-7) with increased access to the Mas1 receptor possibly producing its analgesic effects via MasR activation versus AT2 based on our studies.

Despite implication of the RAS in metastatic disease and pain, few studies have investigated the MasR/Ang-(1-7) peptide fragment, in CIBP. There is evidence that the Mas receptor increases mRNA and protein expression in corresponding DRGs after chronic constriction injury (CCI) to the sciatic nerve and that Ang-(1-7) significantly inhibits neuropathic pain in CCI [79]. In a model of prostaglandin-induced hyperalgesia, Ang-(1-7) dose-dependently attenuated behavioral signs of pain [7; 9; 41]. Due to the inflammatory and neuropathic characteristics of bone cancer pain, we chose to investigate the utility of Ang-(1-7) in CIBP. Acute and chronic systemic administration of Ang-(1-7) significantly reduced the spontaneous pain behaviors associated with CIBP. Importantly, repeated administration attenuated CIBP without loss of efficacy after 7 days. However, we did not see any significant change in nesting behaviors with or without treatments suggesting that the nesting is not representative of possible anxiety or depression in mice with CIBP. The inhibition of guarding and flinching by Ang(1-7) were significantly prevented by the Mas receptor antagonist, A-779. Furthermore, we found that the pre-administration of an AT1 receptor antagonist, Losartan, further alleviates cancer-induced bone pain, yet by itself had no significant effect. Although endogenous Ang-(1-7) has 60–100 fold greater selectivity for MasR over the AT1 and AT2 receptors [11; 58], our results suggest that systemic Ang-(1-7) may bind at both MasR and AT1, implicating that strong binding at MasR may cause a significant antinociceptive effect while weak binding at AT1 may cause Ang-(1-7) to mimic Ang II, resulting in pain. AT1 receptor blockers have been shown to increase angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) which is responsible for the production of endogenous Ang-(1-7), in line with acting at Mas receptors to reduce pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-6 and increase of the anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10 [67–69]. This juxtaposition of pain-relieving and pain-causing actions of Ang-(1-7) implicates the full potential of the Ang-(1-7)/MasR axis in reducing CIBP. Additionally, it has been shown that the Mas-protooncogene has known interactions with the AT1 receptors, but not the AT2 receptor, further supporting our results [73]. Use of Losartan might be additive in effect to Ang-(1-7) in CIBP since AT1 antagonism inhibits Ang-(1-7) from acting similarly to Ang II at AT1, thereby allowing Ang-(1-7) to bind primarily to MasR to significantly alleviate pain. Our results demonstrate that the AT2 antagonist, PD 123319, did not attenuate the effects of Ang-(1-7) nor result in enhanced pain relief, suggesting that the AT2 receptor may not play a role in CIBP. Our results further suggest that MasR is fully activated by exogenous Ang-(1-7) and cannot be further activated by residual breakdown of Ang II.

If MasR is a valid therapeutic target for CIBP and the site of action for Ang-(1-7), one may expect changes in MasR expression within the nociceptive circuit and/or the bone-tumor microenvironment. Our data confirms that MasR is expressed in the DRG of naive mice, in accordance with a previous report of inflammatory pain [9], and in the femur extrudate. However, our two bands for MasR emerged at ~50kDa and ~37kDa; others show MasR at: 37kDa in the retina [49], 49kDa in the skeletal muscle [53], and 83kDa in HEK293T cells [22]. Such inconsistency in molecular weight is currently unexplained in the literature. However, there are three different sites of glycosylation on MasR, which may help to explain the differences in molecular weight. Although repeated Ang-(1-7) administration did not significantly alter the expression of MasR in the DRGs or femur extrudate, its presence in the DRGs and femur extrudate in our model supports the role of Ang-(1-7)/MasR as a potential therapeutic target for CIBP. Repeated Ang-(1-7) dosing does not significantly alter MasR expression in the DRGs containing soma of fibers innervating the bone-tumor microenvironment; supporting our lack of analgesic tolerance over the treatment paradigm.

Our data indicate Ang-(1-7) at the Mas receptor is inhibiting pain via the tumor-nociceptor microenvironment and not the tumor-bone environment since Ang-(1-7) did not significantly change the tumor-induced degradation of the bone. Unlike studies using compounds that modulate bone-wasting [27; 29] and the pain that may come from altered osteoclast activity, our chronic studies with Ang-(1-7) did not significantly decrease bone loss. The chronic treatment with Ang-(1-7) did not significantly alter tumor proliferation, further suggesting the analgesic effect is directly towards inhibiting nociceptive activation and not due to changes in tumor burden.

The exact mechanisms by which Ang-(1-7)/MasR exerts its antinociceptive effect are unknown. In addition to modulating pro-inflammatory factors[61] and regulating transcription of IL-16, an anti-inflammatory cytokine in the tumor-bone microenvironment, Ang-(1-7)/MasR activation of the MAPK pathway may decrease transcription of norepinephrine transporters, leading to an increase of norepinephrine in the synaptic cleft [41] and/or stimulating endogenous noradrenaline release that activates peripheral adrenoceptors inducing antinociception[7]. Moreover, Ang-(1-7) binding to MasR may inhibit phosphorylation of p38 MAPK [41]. Phosphorylation of spinal p38 MAPK has been observed in chronic injury [77], and therefore a decrease in phospho-p38 MAPK in chronic injury models such as cancer-induced bone pain may prove to yield antinociceptive effect. MasR activation by Ang-(1-7) can activate nitric oxide synthase, increasing intracellular NO [8] to further increase intracellular levels of cyclic GMP (cGMP). cGMP production leads to the activation of ATP-dependent potassium channels, thereby hyperpolarizing the neuron [1; 2; 50], in addition to blocking voltage-gated calcium channels that will slow or block neurotransmitter release. Together, the actions of Ang-(1-7)/MasR on cGMP levels can suppress nociception through a decrease in neuronal firing of nociceptive fibers. The mechanisms that result in metastatic bone cancer pain have only recently been investigated that include the significant increase in cytokines [31], an increase in extracellular glutamate [62]. nerve growth factor/TrkA induced, neuronal sprouting of sensory and sympathetic fibers[18–20; 32]. Yet there are no studies that have investigated whether Ang1-7/MasR alter neuronal sprouting or spontaneous activity of sensory neurons. Lastly, the Mas receptor can dimerize with the AT1 receptor [22; 56] where it acts as an antagonist to the receptor. In doing so, such dimerization prevents Ang II from binding, resulting in the possible inhibition of its pronociceptive effects. In a similar fashion, we have shown that the AT1 receptor antagonist is useful in inhibiting Ang-(1-7) from binding in place of Ang II to optimize the antinociceptive effects of this peptide. Further research is warranted to elucidate the exact mechanism by which the Ang-(1-7)/MasR axis is acting to reduce CIBP.

Our results support further investigation of the Mas receptor as a target for cancer therapeutics. Recently, it has been discussed that the GPCRs of the renin-angiotensin system play a significant role in breast cancer [52], and most specifically the Ang-(1-7)/MasR axis, as it has been shown to be protective against cancer. Stimulation of MasR via Ang-(1-7) treatment has been shown to have antiproliferative effects against tumor growth [12; 24; 34] without major effects. Ang-(1-7) treatment in a metastatic prostate cancer model has been shown to lead to a reduction of osteoclastogenesis [23], suggesting Ang-(1-7) prevents the formation of osteolytic lesions. Although our sustained studies using a syngeneic murine model of breast cancer did not result in a significant reduction in tumor proliferation or attenuation in tumor-induced bone loss further investigation of doses, pharmacokinetics and receptor selectivity is further needed to identify tumor survival in the bone-tumor microenvironment and the mechanism(s) of pain inhibition. Thus, the use of Ang-(1-7) in treating CIBP is a highly favorable and a safe alternative or adjuvant therapeutic to the current clinical treatments. Together, our data support the use of Ang-(1-7), perhaps in conjunction with Losartan, as an alternative therapeutic strategy for CIBP.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the College of Medicine at the University of Arizona and by NIH-NCI grant number R01 CA142115-01. All authors contributed to the data collection, interpretation, and writing of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest regarding the research in this manuscript.

References

- 1.Alves D, Duarte I. Involvement of ATP-sensitive K(+) channels in the peripheral antinociceptive effect induced by dipyrone. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;444(1–2):47–52. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01412-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alves DP, Tatsuo MA, Leite R, Duarte ID. Diclofenac-induced peripheral antinociception is associated with ATP-sensitive K+ channels activation. Life sciences. 2004;74(20):2577–2591. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anand U, Facer P, Yiangou Y, Sinisi M, Fox M, McCarthy T, Bountra C, Korchev YE, Anand P. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor (AT2 R) localization and antagonist-mediated inhibition of capsaicin responses and neurite outgrowth in human and rat sensory neurons. European journal of pain. 2013;17(7):1012–1026. doi: 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2012.00269.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birnbaum HG, White AG, Schiller M, Waldman T, Cleveland JM, Roland CL. Societal costs of prescription opioid abuse, dependence, and misuse in the United States. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass) 2011;12(4):657–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blankley CJ, Hodges JC, Klutchko SR, Himmelsbach RJ, Chucholowski A, Connolly CJ, Neergaard SJ, Van Nieuwenhze MS, Sebastian A, Quin J, 3rd, et al. Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of a novel series of non-peptide angiotensin II receptor binding inhibitors specific for the AT2 subtype. J Med Chem. 1991;34(11):3248–3260. doi: 10.1021/jm00115a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carini DJ, Duncia JV, Aldrich PE, Chiu AT, Johnson AL, Pierce ME, Price WA, Santella JB, 3rd, Wells GJ, Wexler RR, et al. Nonpeptide angiotensin II receptor antagonists: the discovery of a series of N-(biphenylylmethyl)imidazoles as potent, orally active antihypertensives. J Med Chem. 1991;34(8):2525–2547. doi: 10.1021/jm00112a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castor MG, Santos RA, Duarte ID, Romero TR. Angiotensin-(1-7) through Mas receptor activation induces peripheral antinociception by interaction with adrenoreceptors. Peptides. 2015;69:80–85. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2015.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costa A, Galdino G, Romero T, Silva G, Cortes S, Santos R, Duarte I. Ang-(1-7) activates the NO/cGMP and ATP-sensitive K+ channels pathway to induce peripheral antinociception in rats. Nitric oxide : biology and chemistry/official journal of the Nitric Oxide Society. 2014;37:11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costa AC, Becker LK, Moraes ER, Romero TR, Guzzo L, Santos RA, Duarte ID. Angiotensin-(1-7) induces peripheral antinociception through mas receptor activation in an opioid-independent pathway. Pharmacology. 2012;89(3–4):137–144. doi: 10.1159/000336340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dursteler-MacFarland KM, Kowalewski R, Bloch N, Wiesbeck GA, Kraenzlin ME, Stohler R. Patients on injectable diacetylmorphine maintenance have low bone mass. Drug and alcohol review. 2011;30(6):577–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferreira AJ, Santos RA. Cardiovascular actions of angiotensin-(1-7) Brazilian journal of medical and biological research = Revista brasileira de pesquisas medicas e biologicas/Sociedade Brasileira de Biofisica [et al] 2005;38(4):499–507. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2005000400003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gallagher PE, Tallant EA. Inhibition of human lung cancer cell growth by angiotensin-(1-7) Carcinogenesis. 2004;25(11):2045–2052. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goswami SC, Mishra SK, Maric D, Kaszas K, Gonnella GL, Clokie SJ, Kominsky HD, Gross JR, Keller JM, Mannes AJ, Hoon MA, Iadarola MJ. Molecular signatures of mouse TRPV1-lineage neurons revealed by RNA-Seq transcriptome analysis. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society. 2014;15(12):1338–1359. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2014.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grey A, Rix-Trott K, Horne A, Gamble G, Bolland M, Reid IR. Decreased bone density in men on methadone maintenance therapy. Addiction. 2011;106(2):349–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta K, Kshirsagar S, Chang L, Schwartz R, Law PY, Yee D, Hebbel RP. Morphine stimulates angiogenesis by activating proangiogenic and survival-promoting signaling and promotes breast tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2002;62(15):4491–4498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hutchinson MR, Zhang Y, Shridhar M, Evans JH, Buchanan MM, Zhao TX, Slivka PF, Coats BD, Rezvani N, Wieseler J, Hughes TS, Landgraf KE, Chan S, Fong S, Phipps S, Falke JJ, Leinwand LA, Maier SF, Yin H, Rice KC, Watkins LR. Evidence that opioids may have toll-like receptor 4 and MD-2 effects. Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24(1):83–95. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inagami T. A memorial to Robert Tiegerstedt: the centennial of renin discovery. Hypertension. 1998;32(6):953–957. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.32.6.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jimenez-Andrade JM, Bloom AP, Stake JI, Mantyh WG, Taylor RN, Freeman KT, Ghilardi JR, Kuskowski MA, Mantyh PW. Pathological Sprouting of Adult Nociceptors in Chronic Prostate Cancer-Induced Bone Pain. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30(44):14649–14656. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3300-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jimenez-Andrade JM, Ghilardi JR, Castaneda-Corral G, Kuskowski MA, Mantyh PW. Preventive or late administration of anti-NGF therapy attenuates tumor-induced nerve sprouting, neuroma formation, and cancer pain. Pain. 2011;152(11):2564–2574. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jimenez-Andrade JM, Mantyh P. Cancer Pain: From the Development of Mouse Models to Human Clinical Trials. 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.King T, Vardanyan A, Majuta L, Melemedjian O, Nagle R, Cress AE, Vanderah TW, Lai J, Porreca F. Morphine treatment accelerates sarcoma-induced bone pain, bone loss, and spontaneous fracture in a murine model of bone cancer. Pain. 2007;132(1–2):154–168. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kostenis E, Milligan G, Christopoulos A, Sanchez-Ferrer CF, Heringer-Walther S, Sexton PM, Gembardt F, Kellett E, Martini L, Vanderheyden P, Schultheiss HP, Walther T. G-protein-coupled receptor Mas is a physiological antagonist of the angiotensin II type 1 receptor. Circulation. 2005;111(14):1806–1813. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000160867.23556.7D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krishnan B, Smith TL, Dubey P, Zapadka ME, Torti FM, Willingham MC, Tallant EA, Gallagher PE. Angiotensin-(1-7) attenuates metastatic prostate cancer and reduces osteoclastogenesis. The Prostate. 2013;73(1):71–82. doi: 10.1002/pros.22542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krishnan B, Torti FM, Gallagher PE, Tallant EA. Angiotensin-(1-7) reduces proliferation and angiogenesis of human prostate cancer xenografts with a decrease in angiogenic factors and an increase in sFlt-1. The Prostate. 2013;73(1):60–70. doi: 10.1002/pros.22540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lakshmanan AP, Thandavarayan RA, Watanabe K, Sari FR, Meilei H, Giridharan VV, Sukumaran V, Soetikno V, Arumugam S, Suzuki K, Kodama M. Modulation of AT-1R/MAPK cascade by an olmesartan treatment attenuates diabetic nephropathy in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Molecular and cellular endocrinology. 2012;348(1):104–111. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lennon FE, Mirzapoiazova T, Mambetsariev B, Poroyko VA, Salgia R, Moss J, Singleton PA. The Mu opioid receptor promotes opioid and growth factor-induced proliferation, migration and Epithelial Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) in human lung cancer. PloS one. 2014;9(3):e91577. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lozano-Ondoua AN, Hanlon KE, Symons-Liguori AM, Largent-Milnes TM, Havelin JJ, Ferland HL, 3rd, Chandramouli A, Owusu-Ankomah M, Nikolich-Zugich T, Bloom AP, Jimenez-Andrade JM, King T, Porreca F, Nelson MA, Mantyh PW, Vanderah TW. Disease modification of breast cancer-induced bone remodeling by cannabinoid 2 receptor agonists. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28(1):92–107. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lozano-Ondoua AN, Symons-Liguori AM, Vanderah TW. Cancer-induced bone pain: Mechanisms and models. Neurosci Lett. 2013;557(Pt A):52–59. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lozano-Ondoua AN, Wright C, Vardanyan A, King T, Largent-Milnes TM, Nelson M, Jimenez-Andrade JM, Mantyh PW, Vanderah TW. A cannabinoid 2 receptor agonist attenuates bone cancer-induced pain and bone loss. Life sciences. 2010;86(17–18):646–653. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luger NM, Honore P, Sabino MA, Schwei MJ, Rogers SD, Mach DB, Clohisy DR, Mantyh PW. Osteoprotegerin diminishes advanced bone cancer pain. Cancer Res. 2001;61(10):4038–4047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mach DB, Rogers SD, Sabino MC, Luger NM, Schwei MJ, Pomonis JD, Keyser CP, Clohisy DR, Adams DJ, O’Leary P, Mantyh PW. Origins of skeletal pain: sensory and sympathetic innervation of the mouse femur. Neuroscience. 2002;113(1):155–166. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00165-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mantyh WG, Jimenez-Andrade JM, Stake JI, Bloom AP, Kaczmarska MJ, Taylor RN, Freeman KT, Ghilardi JR, Kuskowski MA, Mantyh PW. Blockade of nerve sprouting and neuroma formation markedly attenuates the development of late stage cancer pain. Neuroscience. 2010;171(2):588–598. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.08.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mehta PK, Griendling KK. Angiotensin II cell signaling: physiological and pathological effects in the cardiovascular system. American journal of physiology Cell physiology. 2007;292(1):C82–97. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00287.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Menon J, Soto-Pantoja DR, Callahan MF, Cline JM, Ferrario CM, Tallant EA, Gallagher PE. Angiotensin-(1-7) inhibits growth of human lung adenocarcinoma xenografts in nude mice through a reduction in cyclooxygenase-2. Cancer Res. 2007;67(6):2809–2815. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mercadante S. Malignant bone pain: pathophysiology and treatment. Pain. 1997;69(1–2):1–18. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(96)03267-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mundy GR. Pathophysiology of cancer-associated hypercalcemia. Seminars in oncology. 1990;17(2 Suppl 5):10–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muralidharan A, Wyse BD, Smith MT. Analgesic efficacy and mode of action of a selective small molecule angiotensin II type 2 receptor antagonist in a rat model of prostate cancer-induced bone pain. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass) 2014;15(1):93–110. doi: 10.1111/pme.12258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Myles PS, Peyton P, Silbert B, Hunt J, Rigg JR, Sessler DI, Investigators ATG. Perioperative epidural analgesia for major abdominal surgery for cancer and recurrence-free survival: randomised trial. Bmj. 2011;342:d1491. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nagae M, Hiraga T, Yoneda T. Acidic microenvironment created by osteoclasts causes bone pain associated with tumor colonization. Journal of bone and mineral metabolism. 2007;25(2):99–104. doi: 10.1007/s00774-006-0734-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Negus SS, Neddenriep B, Altarifi AA, Carroll FI, Leitl MD, Miller LL. Effects of ketoprofen, morphine, and kappa opioids on pain-related depression of nesting in mice. Pain. 2015;156(6):1153–1160. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nemoto W, Ogata Y, Nakagawasai O, Yaoita F, Tadano T, Tan-No K. Angiotensin (1-7) prevents angiotensin II-induced nociceptive behaviour via inhibition of p38 MAPK phosphorylation mediated through spinal Mas receptors in mice. European journal of pain. 2014;18(10):1471–1479. doi: 10.1002/ejp.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O’Connell JX, Nanthakumar SS, Nielsen GP, Rosenberg AE. Osteoid osteoma: the uniquely innervated bone tumor. Modern pathology : an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc. 1998;11(2):175–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ohshima K, Mogi M, Nakaoka H, Iwanami J, Min LJ, Kanno H, Tsukuda K, Chisaka T, Bai HY, Wang XL, Ogimoto A, Higaki J, Horiuchi M. Possible role of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and activation of angiotensin II type 2 receptor by angiotensin-(1-7) in improvement of vascular remodeling by angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockade. Hypertension. 2014;63(3):e53–59. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.02426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Papinska AM, Mordwinkin NM, Meeks CJ, Jadhav SS, Rodgers KE. Angiotensin-(1-7) administration benefits cardiac, renal and progenitor cell function in db/db mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2015 doi: 10.1111/bph.13225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Passos-Silva DG, Verano-Braga T, Santos RA. Angiotensin-(1-7): beyond the cardio-renal actions. Clinical science (London, England : 1979) 2013;124(7):443–456. doi: 10.1042/CS20120461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pavel J, Tang H, Brimijoin S, Moughamian A, Nishioku T, Benicky J, Saavedra JM. Expression and transport of Angiotensin II AT1 receptors in spinal cord, dorsal root ganglia and sciatic nerve of the rat. Brain Res. 2008;1246:111–122. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.09.099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perez-Castrillon JL, Olmos JM, Gomez JJ, Barrallo A, Riancho JA, Perera L, Valero C, Amado JA, Gonzalez-Macias J. Expression of opioid receptors in osteoblast-like MG-63 cells, and effects of different opioid agonists on alkaline phosphatase and osteocalcin secretion by these cells. Neuroendocrinology. 2000;72(3):187–194. doi: 10.1159/000054586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Portenoy RK, Lesage P. Management of cancer pain. Lancet. 1999;353(9165):1695–1700. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01310-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Prasad T, Verma A, Li Q. Expression and cellular localization of the Mas receptor in the adult and developing mouse retina. Molecular vision. 2014;20:1443–1455. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reis GM, Pacheco D, Perez AC, Klein A, Ramos MA, Duarte ID. Opioid receptor and NO/cGMP pathway as a mechanism of peripheral antinociceptive action of the cannabinoid receptor agonist anandamide. Life sciences. 2009;85(9–10):351–356. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2009.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rice AS, D RH, McCarthy TD, Anand P, Bountra C, McCloud PI, Hill J, Cutter G, Kitson G, Desem N, Raff M, EMA401-003 study group EMA401, an orally administered highly selective angiotensin II type 2 receptor antagonist, as a novel treatment for postherpetic neuralgia: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 clinical trial. Lancet. 2014;383:1637–1647. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62337-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rodrigues-Ferreira S, Nahmias C. G-protein coupled receptors of the renin-angiotensin system: new targets against breast cancer? Frontiers in pharmacology. 2015;6:24. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2015.00024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sabharwal R, Cicha MZ, Sinisterra RD, De Sousa FB, Santos RA, Chapleau MW. Chronic oral administration of Ang-(1-7) improves skeletal muscle, autonomic and locomotor phenotypes in muscular dystrophy. Clinical science (London, England : 1979) 2014;127(2):101–109. doi: 10.1042/CS20130602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sabino MA, Luger NM, Mach DB, Rogers SD, Schwei MJ, Mantyh PW. Different tumors in bone each give rise to a distinct pattern of skeletal destruction, bone cancer-related pain behaviors and neurochemical changes in the central nervous system. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2003;104(5):550–558. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sabino MA, Mantyh PW. Pathophysiology of bone cancer pain. J Support Oncol. 2005;3(1):15–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Santos EL, Reis RI, Silva RG, Shimuta SI, Pecher C, Bascands JL, Schanstra JP, Oliveira L, Bader M, Paiva AC, Costa-Neto CM, Pesquero JB. Functional rescue of a defective angiotensin II AT1 receptor mutant by the Mas protooncogene. Regulatory peptides. 2007;141(1–3):159–167. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2006.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Santos RA, Haibara AS, Campagnole-Santos MJ, Simoes e Silva AC, Paula RD, Pinheiro SV, Leite MF, Lemos VS, Silva DM, Guerra MT, Khosla MC. Characterization of a new selective antagonist for angiotensin-(1-7), D-pro7-angiotensin-(1-7) Hypertension. 2003;41(3 Pt 2):737–743. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000052947.60363.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Santos RA, Simoes e Silva AC, Maric C, Silva DM, Machado RP, de Buhr I, Heringer-Walther S, Pinheiro SV, Lopes MT, Bader M, Mendes EP, Lemos VS, Campagnole-Santos MJ, Schultheiss HP, Speth R, Walther T. Angiotensin-(1-7) is an endogenous ligand for the G protein-coupled receptor Mas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(14):8258–8263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1432869100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schwei MJ, Honore P, Rogers SD, Salak-Johnson JL, Finke MP, Ramnaraine ML, Clohisy DR, Mantyh PW. Neurochemical and cellular reorganization of the spinal cord in a murine model of bone cancer pain. J Neurosci. 1999;19(24):10886–10897. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-24-10886.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sharma A, C HW, Freeman R, Santoro N, Schoenbaum EE. Prospective evaluation of bone mineral density among middle-aged HIV-infected and uninfected women: Association between methadone use and bone loss. Maturitas. 2011;70(3):295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Simoes e Silva AC, Silveira KD, Ferreira AJ, Teixeira MM. ACE2, angiotensin-(1-7) and Mas receptor axis in inflammation and fibrosis. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;169(3):477–492. doi: 10.1111/bph.12159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Slosky LM, B N, Symons AM, Thompson M, Doyle T, Forte BL, Staatz WD, Bui L, Neumann WL, Mantyh PW, Salvemini D, Largent-Milnes TM, Vanderah TW. The Cystine/Glutamate Antiporter System xc- Drives Breast Tumor Cell Glutamate Release and Cancer-Induced Bone Pain. Pain. 2016 doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000681. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Slosky LM, Largent-Milnes TM, Vanderah TW. Use of Animal Models in Understanding Cancer-induced Bone Pain. Cancer Growth Metastasis. 2015;8(Suppl 1):47–62. doi: 10.4137/CGM.S21215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Smith MT, Woodruff TM, Wyse BD, Muralidharan A, Walther T. A small molecule angiotensin II type 2 receptor (AT(2)R) antagonist produces analgesia in a rat model of neuropathic pain by inhibition of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and p44/p42 MAPK activation in the dorsal root ganglia. Pain medicine. 2013;14(10):1557–1568. doi: 10.1111/pme.12157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Smith MT, Wyse BD, Edwards SR. Small molecule angiotensin II type 2 receptor (AT(2)R) antagonists as novel analgesics for neuropathic pain: comparative pharmacokinetics, radioligand binding, and efficacy in rats. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass) 2013;14(5):692–705. doi: 10.1111/pme.12063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stevens CW, Aravind S, Das S, Davis RL. Pharmacological characterization of LPS and opioid interactions at the toll-like receptor 4. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;168(6):1421–1429. doi: 10.1111/bph.12028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sukumaran V, Veeraveedu PT, Gurusamy N, Lakshmanan AP, Yamaguchi K, Ma M, Suzuki K, Kodama M, Watanabe K. Telmisartan acts through the modulation of ACE-2/ANG 1-7/mas receptor in rats with dilated cardiomyopathy induced by experimental autoimmune myocarditis. Life sciences. 2012;90(7–8):289–300. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2011.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sukumaran V, Veeraveedu PT, Gurusamy N, Lakshmanan AP, Yamaguchi K, Ma M, Suzuki K, Nagata M, Takagi R, Kodama M, Watanabe K. Olmesartan attenuates the development of heart failure after experimental autoimmune myocarditis in rats through the modulation of ANG 1-7 mas receptor. Molecular and cellular endocrinology. 2012;351(2):208–219. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sukumaran V, Veeraveedu PT, Gurusamy N, Yamaguchi K, Lakshmanan AP, Ma M, Suzuki K, Kodama M, Watanabe K. Cardioprotective effects of telmisartan against heart failure in rats induced by experimental autoimmune myocarditis through the modulation of angiotensin-converting enzyme-2/angiotensin 1-7/mas receptor axis. International journal of biological sciences. 2011;7(8):1077–1092. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.7.1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tronvik E, Stovner LJ. Role of angiotensin modulation in primary headaches. Current pain and headache reports. 2014;18(5):417. doi: 10.1007/s11916-014-0417-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vanderah TW, Largent-Milnes T, Lai J, Porreca F, Houghten RA, Menzaghi F, Wisniewski K, Stalewski J, Sueiras-Diaz J, Galyean R, Schteingart C, Junien JL, Trojnar J, Riviere PJ. Novel D-amino acid tetrapeptides produce potent antinociception by selectively acting at peripheral kappa-opioid receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;583(1):62–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vermeirsch H, Nuydens RM, Salmon PL, Meert TF. Bone cancer pain model in mice: evaluation of pain behavior, bone destruction and morphine sensitivity. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004;79(2):243–251. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.von Bohlen und Halbach O, Walther T, Bader M, Albrecht D. Interaction Between Mas and the Angiotensin AT1 Receptor in the Amygdala. J Neurophysiology. 2000;83(4):2012–2021. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.4.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Walser TC, Rifat S, Ma X, Kundu N, Ward C, Goloubeva O, Johnson MG, Medina JC, Collins TL, Fulton AM. Antagonism of CXCR3 inhibits lung metastasis in a murine model of metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66(15):7701–7707. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang X, Loram LC, Ramos K, de Jesus AJ, Thomas J, Cheng K, Reddy A, Somogyi AA, Hutchinson MR, Watkins LR, Yin H. Morphine activates neuroinflammation in a manner parallel to endotoxin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(16):6325–6330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200130109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.WHO. Cancer Pain Relief. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organziation; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Xu L, Huang Y, Yu X, Yue J, Yang N, Zuo P. The influence of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitor on synthesis of inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor alpha in spinal cord of rats with chronic constriction injury. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2007;105(6):1838–1844. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000287660.29297.7b. table of contents. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yang Y, Wu H, Yan JQ, Song ZB, Guo QL. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibits angiotensin II receptor type 1 expression in dorsal root ganglion neurons via beta-catenin signaling. Neuroscience. 2013;248:383–391. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhao Y, Qin Y, Liu T, Hao D. Chronic nerve injury-induced Mas receptor expression in dorsal root ganglion neurons alleviates neuropathic pain. Experimental and therapeutic medicine. 2015;10(6):2384–2388. doi: 10.3892/etm.2015.2801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zylla D, Gourley BL, Vang D, Jackson S, Boatman S, Lindgren B, Kuskowski MA, Le C, Gupta K, Gupta P. Opioid requirement, opioid receptor expression, and clinical outcomes in patients with advanced prostate cancer. Cancer. 2013;119(23):4103–4110. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]