Summary

The recent discovery of human-induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) has revolutionized the field of stem cells. iPSCs have demonstrated that biological development is not an irreversible process and that mature adult somatic cells can be induced to become pluripotent. This breakthrough is projected to advance our current understanding of many disease processes and revolutionize the approach to effective therapeutics. Despite the great promise of iPSCs, many translational challenges still remain. In this article, we review the basic concept of induction of pluripotency as a novel approach to understand cardiac regeneration, cardiovascular disease modeling and drug discovery. We critically reflect on the current results of preclinical and clinical studies using iPSCs for these applications with appropriate emphasis on the challenges facing clinical translation.

Keywords: Induced pluripotent stem cells, Cardiac regeneration, Disease modeling, Drug discovery

Origin of the Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs)

The totipotency of a fertilized egg confers a unique ability to divide and differentiate into all tissue types to form an entire organism. To identify the exact role of a mammalian cell nucleus undergoing embryonic development, somatic cell nuclear transfer experiments were conducted in frogs in the 1950s (1). These experiments offered a proof of principle that pluripotency can be conferred to somatic cells by transferring their nuclear contents into oocytes (2). In fact, the nuclei of differentiated mammalian cells possess the ability to become pluripotent upon transfer of the nucleus into an oocyte or fusion with embryonic stem cells (ESCs) (3,4). For many years, the major challenge was to reprogram the somatic cell nucleus without transferring its content or using an oocyte (5). In 2006, Takahashi and Yamanaka studied the effects of 24 transcription factors, which were known to confer pluripotency to early embryos and ESCs (6). They succeeded in transforming the adult mouse fibroblasts into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) using four select transcription factors: Oct4, Sox2, c-Myc, and Klf4 (6,7). These iPSCs exhibited characteristics very similar to ESCs. One year later, the same group generated human iPSCs from human dermal fibroblasts using retroviral transduction with the same four transcription factors (8). These iPSCs have morphology, cell surface markers, and genes characteristics similar to human ESCs, exhibiting unlimited replication potential without telomere shortening or karyotype changes. The multi-lineage differentiation potential of iPSCs has been confirmed both in vitro in embryoid bodies and in vivo based upon teratoma formation upon injection into SCID mice. Other groups reproduced the “stemness” or induced pluripotency of somatic cells using the same or slightly different transcription factors, demonstrating the robustness of this technique and revolutionizing the field of stem cell biology (9–11).

Since the ability to generate iPSCs in culture from adult human skin fibroblasts has been established (8,9), this pluripotent state has been induced in a variety of human cells including keratinocytes (12), T-lymphocytes (13), peripheral mononuclear blood cells (14), cord blood (15), placenta (16), neural stem cells (17), adipose tissue (18), and renal epithelial cells present in urine samples (19). Ectopic expression of different combinations of reprogramming factors has been used, with Oct4 being the most consistent across protocols. Furthermore, several protocols have been developed for directed in vitro differentiation of iPSCs into spontaneously contractile cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, and vascular endothelial cells (20,21). The differentiation of iPSCs into cardiomyocytes was confirmed by microscopic examination of beating colonies, immunostaining for cardiac proteins, electrophysiological testing, and real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis of cardiac markers (20,21). The iPSCs overcame the ethical concerns and immunogenicity of human ESCs (hESCs), thus becoming an attractive alternative for autologous tissue repair and regeneration as well as a source for allogeneic transplantation. The therapeutic potential of iPSC-derived cells has been tested in many preclinical studies with some encouraging results in murine and porcine models of myocardial infarction (MI) (16,22–25). Currently, the first human trials of iPSC-derived cells, aimed at establishing the safety of these cells, are enrolling patients with age-related macular degeneration (AMD) in Japan (26).

Beyond the potential for regenerative or transplantation therapies, iPSCs offer an unprecedented opportunity to recapitulate both normal and pathologic human tissue formation in vitro, thereby providing novel cell-based biological models that enable better understanding of disease pathogenesis and drug discovery (27). From 2008 to 2015, more than 70 human iPSC-based disease models have been published in an exponential fashion (28). The ability to examine the direct effects and toxicity of new drugs on the patients’ own cells could also represent an invaluable tool for drug development and discovery. For these reasons both Sir John Gurdon, who performed nuclear transfer experiments, and Shinya Yamanaka were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2012. This article discusses the current status of the cardiovascular applications of iPSCs for cardiac and vascular regeneration, disease modeling, and drug discoveries with a special emphasis on the current challenges for clinical translation.

iPSCs for Cardiovascular Regeneration

With the growing epidemic of heart failure, cardiac regeneration represents one of the major priorities of regenerative medicine. The ability of iPSCs to differentiate into autologous tissue-specific cells, similar to ESCs but without the need to destroy a human embryo, is an important breakthrough in human stem cell biology. A number of preclinical studies have explored the effects of intramyocardial injection of iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes (iCMs) into murine and porcine models of MI (a complete recent list of preclinical studies is provided in Lalit et al) (29). Nelson et al were the first to perform intramyocardial injection of iPSC-derived cells into a murine model of acute MI (30). They found improved left-ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), fractional shortening, and regional wall motion on echocardiography 4 weeks after permanent coronary artery ligation when compared to the fibroblast-injected animals. Interestingly, they reported teratoma formation upon subcutaneous and intramyocardial injections of iPSCs in immunodeficient animals but none in immunocompetent mice (30).

Other studies have reported formation of intramural teratomas in both immunocompetent and severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice after intramyocardial injection of undifferentiated iPSCs (31,32). Kim et al. tracked the engraftment of iPSCs at 4 weeks in SCID murine model of MI. They demonstrated teratoma formation with no myocardial or endothelial cell differentiation despite the reported improvement in myocardial function and myocardial viability (32). This demonstrates a potential mechanistic role of cytokines released from the iPSCs, which may restore cardiac function despite teratoma formation. Similar results were obtained with undifferentiated iPSCs in a rat model of MI (33), consistent with the initial studies of undifferentiated murine ESCs that resulted in teratoma formation (34,35).

Repeat experiment using differentiated skeletal myoblast derived-iCMs obtained from day 10 embryoid body (EB)-beating aggregates, reported improved cardiac function with decreased infarct size and no evidence of tumorigenesis (36). Similar improvement in LV function without teratoma formation was reported by the same group using cardiac progenitors harvested from EB-beating aggregates of mesenchymal stem cells derived-iPSCs (37). Currently, it is widely thought that the pluripotent stem cell derivatives from either ESCs or iPSCs are still premature for clinical therapy because of the tumorigenic potential. Active research is ongoing using highly purified monolayer populations of differentiated iCMs and methods to remove the undifferentiated iPSCs (38). Through these efforts, generation of >90% pure populations of iCMs is increasingly routine in laboratories worldwide (39).

Using a single transcription factor (Oct3/4), Pasha et al were able to generate iPSCs from mouse skeletal myoblasts that endogenously express 3 of the Yamanaka factors (40). They were also able to isolate cardiac progenitors from 5-day beating embryoid bodies (EBs). In this experiment, iPSCs-derived cardiac progenitor cells showed sustained engraftment and gap junction formation upon transplantation into the infarcted murine heart (40). Another group reported significantly restored cardiac function in post-MI ventricular remodeling after intramyocardial injection of fetal-liver kinase 1 (FLK-1) positive iPSC-derived cardiac progenitor cells into SCID mice (41). Based on the advantage conferred by epigenetic memory, cardiac progenitor cells (CPCs) expressing the surface marker Sca1 were used for induction of pluripotency to leverage their preferential cardiac differentiation potential. Compared with skin fibroblast-derived iPSCs, CPC-derived iPSCs were more efficient in producing cardiomyocytes, smooth muscles cells, and endothelial cells (25). However, in vivo echocardiography and post-mortem infarct size analysis showed no significant difference between the two types of cells that were only marginally better than placebo at 8 weeks (25).

To improve the engraftment of iCMs into the infarcted myocardium, Dai et al developed a homologous peritoneal patch seeded with iCMs, CD31-selected iPSC-derived endothelial cells, and mouse embryonic fibroblasts (tri-cell patch, “Tri-P”) (42). The Tri-P was used to cover the infarcted area instead of an intramyocardial injection into an infarcted myocardium (42,43). Kawamura et al used a cell-sheet technique to ensure delivery of a large number of cells (22). Immunosuppressed mini-pigs (n=6) were transplanted with human iCMs in cell sheets, containing approximately 25 million cells, 4 weeks after MI. Significantly improved LVEF and reduced end-systolic volume were noted in the iCM group. Despite these positive results over sham pigs, poor engraftment was noted by 8 weeks. The authors proposed that the poor engraftment was due to insufficient immune suppression with a single agent (tacrolimus) in a xenogeneic transplantation model (22).

Beyond myocardial regeneration, many investigators have employed iPSC technology for inducing vascular regeneration in patients with coronary and peripheral artery disease (CAD, PAD) where new vascular structures might overcome impaired perfusion caused by occlusive atherosclerotic disease. Most work in vascular regeneration has been done with adult stem cells (44). For PAD, smaller clinical trials of adult stem cell therapy have shown promise in populations with different levels of disease severity (45,46). Currently, a large NIH/NHLBI-sponsored Cardiovascular Cell Therapy Research Network trial using aldehyde dehydrogenase bright cells for intermittent claudication is ongoing (47). Stem cells obtained from adult tissues can be problematic, however. In elderly patients and those with comorbidities like diabetes – patients most likely to benefit from stem cell therapy – the quantity and function of stem cells can be impaired (48,49). In contrast, iPSCs can theoretically be derived from many tissue sources, thereby obviating the issue of cell quantity and quality. Furthermore, due to their pluripotency, iPSCs can differentiate into the multiple cell types needed in ischemic tissue such as smooth muscle, pericyte, and cardiac cells in addition to the endothelial cells for regenerative purpose (30).

Although there are currently no clinical trials using iPSCs for neovascularization, preclinical studies show great promise (50). Choi, Taura and colleagues were among the first researchers to describe differentiation of iPSCs into endothelial cells (51,52). Both groups found that the iPSC-derived endothelial cells (iECs) were very similar to endothelial cells derived from hESCs. Since then, the iECs have been used in murine hindlimb ischemia models and have been found to improve limb perfusion at least in part through neovascularization. Compared to the hECs, iECs appear to have similar therapeutic efficacy (53). Another potential use of the iECs in the setting of vascular insufficiency is for engineering better vascular conduits. Wang and colleagues have demonstrated that functional smooth muscle cells can be derived from human iPSCs and used on a scaffold to regenerate vascular tissue in vivo (54). Additional pre-clinical studies will demonstrate the potential efficacy of these novel therapeutic approaches.

Current Challenges for the iPSCs in Cardiovascular Regeneration

Despite the promise of iPSCs for regenerative medicine, there are still many roadblocks remaining that may hinder their clinical use:

1. Cell engraftment

Poor cell engraftment remains a major challenge for all stem cell therapies for cardiovascular applications. The inability of the transplanted cells to exhibit long-term survival and engraftment into the host myocardium with successful electromechanical integration into the complex cardiac syncytium has been a consistent finding throughout many studies (55–58). Despite the fast pace of progress in the field of stem cell biology, there has been no improvement in engraftment over the past decade regardless of the types of stem cells used (25,57,59,60). In many preclinical studies with positive functional results, the assessment of long-term, stable engraftment and electromechanical integration of the stem cells by the use of molecular reporter genes has yielded variable results (32,59). In most of these studies, the mechanism underlying the positive results was postulated to be a “paracrine effect” (22,32,58). The shortcoming of the paracrine effect hypothesis is that it is difficult to measure this process in isolation. It is also challenging to pinpoint the specific biochemical factor(s) responsible for the salubrious actions of stem cells. Nevertheless, investigations are in order because if such a paracrine factor(s) is identified, this finding may obviate the need for cell therapy.

To address questions regarding the magnitude and mechanism of cardiac repair after injury in a practical way, multiple animal and clinical studies have tested the efficacy of different stem cell types for cardiac regeneration (58). Nevertheless, the limited engraftment of the stem cells and the inability to track the cells delivered in vivo have left many unanswered questions regarding the mechanism and description of the postulated benefit.

Although no direct correlative data exist, the poor cell engraftment may be associated with the low regenerative capacity of the heart. Earlier studies in late 1990s and early 2000s using evidence from small-animal experiments (61), clinical sex-mismatched heart and bone marrow transplantation studies (62) and the observation of dividing myocytes within the infarcted myocardium (63) and failing hearts (64), showed that the heart may possess significant regenerative capacity, contradicting the old dogma of the heart as a terminally differentiated organ. These studies, together with the concomitant isolation of different types of adult human stem cells (65,66) and hESCs (67), established the foundation of the emerging field of regenerative cardiology. Despite the optimism that accompanied these studies, the rate and magnitude of ongoing turnover and cardiac regeneration have been controversial, with more recent studies showing that adult cardiomyocytes may possess very limited mitotic capability (68,69). Bergmann et al calculated the post-natal human cardiomyocyte renewal at ~1% annually at age 20, declining to 0.4% annually by age 70 (68). More recently, van Berlo et al found that endogenous c-kit+ cells mainly regenerate endothelial cells with only minor contribution towards cardiomyocyte renewal, estimated at a rate of 0.03% – 0.008% (69).

Another reason for the low engraftment could be the study design and route of administration of stem cells. Most stem cell studies attempted to deliver stem cells into an area of infarction, either directly through intramyocardial injection or indirectly through intracoronary infusion, to regenerate the myocardium. Such a design worked well with bone marrow transplantation but may not be suitable for a complex organ like the heart, particularly in the setting of ischemic cardiomyopathy with impaired perfusion, increased oxidative stress, and inflammation. Even in the skin, which is a regenerative organ, skin burns are not cured by injecting stem cells into the skin but rather by using skin grafts. It may be necessary to modify current delivery techniques to address the complexity of the heart. Efforts are underway by several groups using different tissue engineering techniques and cell derivatives (22,42,43).

Cell engraftment in studies of vascular regeneration poses a different challenge. In contrast to the low regenerative capacity of cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells show greater capacity for regeneration and repair in response to vascular injury via endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) mostly derived from the bone marrow (70,71). However, age and cardiovascular diseases such as coronary artery disease, cerebral vascular disease, congestive heart failure, and diabetes can significantly reduce both the quality and quantity of circulating EPCs. Though studies evaluating the nature of iPSC incorporation into native vascular endothelium are lacking, using embryonic derived endothelial cells (ESC-ECs), Huang and colleagues provided evidence of stem cell engraftment and neovascularization in a mouse ischemic limb model (72).

2. Technical issues with the induction of pluripotency, cardiac differentiation and maturation

Reprograming somatic cells to a pluripotent state involves introducing transgenes, their derivative RNA, or protein products with multiple passages in tissue culture. Several studies suggest that the reprogramming process induces genomic instability and down-regulates tumor suppressor genes, which can affect cellular integrity (73–76). Comparing 12 human iPSC lines generated from the same primary fibroblast cell, Laurent el al found genetic aberrations in iPSCs lines that were not present in the original fibroblast line (76). Also, Li et al calculated the degree of genetic heterogeneity among 24 iPSC clones obtained from skin fibroblasts of the same 8-week old mouse, and found 383 iPSC variants from the original 24 clones with a mean of 16.0 variants/clone and a range of 0–45, indicating a wide range of heterogeneity (75). For these reasons, iPSCs are not approved for clinical use in the US, and many have suggested that the study in the Japanese patients with AMD may be premature (77).

As the field of iPSCs is only few years old, protocols for induction of pluripotency and cardiac differentiation are still evolving and there is a lack of consensus. Current iPSC lines have been generated using different cells of origin, different transcription factor combinations, different vectors (viral and non-viral), different time in culture, different number of passages and different selection methods. Such inconsistency adds further layers of complexity to the endogenous heterogeneity created by the reprogramming process and expansion in culture, resulting in absence of the uniformity needed for clinical therapeutic applications.

Pluripotency can be induced from a variety of human cells (12–19), and the best cell of origin for induction of pluripotency for cardiac application is not known yet. Several studies have suggested that after induction of pluripotency, somatic cells retain some characteristics of their past identity, the so-called epigenetic memory (78). Although this epigenetic memory can be seen as a sign of incomplete programming, it can be used to facilitate differentiation towards the desired cell type more efficiently (27).

Another technical issue is the low efficiency of the reprogramming process, which ranges from as much as 4.4% with modified mRNA and 1% with integrating viruses to as little as 0.001% with the non-integrating Sendai virus, adenovirus, plasmids, and direct protein delivery (79). Efficiency decreases further if one does not use the oncogene c-myc (80). Currently, integrating viruses are falling out of favor because of the oncogenic potential resulting from incomplete proviral silencing. A recent comprehensive analysis of non-integrating reprogramming methods for human iPSCs was published to compare the quality of cells, reliability, efficiency, speed of colony emergence, aneuploidy rate, and hands-on time for each method (81).

Optimized protocols for cardiac differentiation have been developed which replicate the key commitment stages found during embryonic development (82). While removal of the undifferentiated cells and purification of the iCMs are becoming more standardized, it is becoming evident that the iCMs may represent immature and heterogeneous groups of cardiomyocytes (38,83). A recent study calculated ventricular cardiomyocytes to be 50% of differentiated cardiomyoctes, with atrial cardiomyocytes being 37.5% and nodal cells 12.5% (84). The clinical use of this mixture of different iCMs again may generate inconsistent results. A similar phenomenon is seen in the production of human iPSC-ECs (iECs), which have been found to express multiple cell markers associated with lymphatic, venous and arterial ECs (85). In this study, higher levels of VEGF were associated with more iECs with an arterial phenotype and it was this arterial phenotype of cells that demonstrated the best in vivo performance in the development of mature and stable capillaries.

Cardiomyocyte maturation is another important step for cell therapy. In vitro tissue culture conditions are obviously different from the environment of developing embryonic hearts. The tensile stretch exerted on the developing cardiomyocytes as well as the micro-environmental milieu of molecules and growth factors play a key role in cardiomyocytes growth and maturation. The current cell culture techniques on the flat surface of a Petri dish or in suspension deprive the developing cardiomyocytes of important maturation signals. Newer culture techniques that offer optimal tensile structure for the developing cardiomyocytes, pulsed treatment with novel molecules and growth factors, and electrophysiological cues may enable selection of the iCMs at a developmentally appropriate stage for therapeutic purposes (86).

3. Immunogenicity

One advantage of iPSCs over other types of stem cells is their autologous source, with no expected immune rejection. This assumption is also supported by the lack of immune rejection upon administration of iPSCs in many preclinical studies. However, a few studies have reported T-cell immune rejection of undifferentiated iPSCs upon transplantation into syngeneic mice (87,88). These studies raise the possibility that cell reprogramming, genetic instability, culture conditions, and frequent passages could alter iPSCs in a way that renders them immunogenic. However, further studies using differentiated iPSCs have shown negligible immunogenicity (89,90). Taken together, the available evidence indicates that although immune rejection may be possible, it does not seem to be a consistent finding. The ongoing clinical trial in AMD in Japan will also address this question. However, we believe that further preclinical studies using differentiated cells are required to resolve the issue of immunogenicity.

4. Autologous versus allogeneic source

One great advantage of iPSCs is the autologous source, which makes iPSCs an inexhaustible source for cell therapies without immune rejection or ethical issues. However, there are several logistic issues with an autologous source. Induction of pluripotency followed by lineage-specific differentiation is a time-consuming process that requires multiple passages of iPSCs followed by differentiation and purification, which may make autologous iPSCs suitable only for chronic illnesses but not for acute conditions such as acute MI. Also, custom-made autologous cells would make clinical good manufacturing practice, quality assurance, regulatory compliance, and elimination of technical errors very expensive, limiting the reproducibility of the technique and its potential wide-scale clinical application (91). This paradigm, however, applies to almost all autologous cell therapies requiring in vitro expansion.

While iPSCs are traditionally considered a potential autologous therapy, the ability to identify iPSC genotypes and preselect matching donors provides a potential opportunity for allogeneic therapy. Several investigators have proposed the creation of large allogeneic libraries of clinical-grade quality iPSCs and iPSC-derivatives (91–93). However, such cell/tissue libraries would require several thousand random donors to cover the Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) genotype variability within a specific population (93,94). Despite logistic and financial difficulties, establishment of a blood-derived iPSCs library has been initiated in Japan (91). This approach would provide safe off-the-shelf allografts of HLA-homozygous iPSC-derivatives ready for clinical use after excluding tumorigenic clones (95). Another advantage of the iPSC library is that the donors will be subjected to only minor procedures (e.g., blood sampling, skin biopsy) while the iPSCs can be used in an unlimited number of matched recipients (92), addressing the tissue availability issue and potentially improving graft survival (96), but not completely eliminating the need for immunosuppressive medications.

5. Tumorigenicity

Tumorigenicity represents another potential obstacle to the clinical application of iPSCs. In fact, the current functional “gold standard” test for pluripotency of human iPSCs is teratoma formation upon injection into immunodeficient mice (7). Pluripotent origin, incomplete differentiation, and difficulty in eliminating all undifferentiated cells may lead to potential teratoma formation (7). However, advances in differentiation techniques and tissue culture conditions have mitigated this challenge, resulting in highly pure (>90%) iCM populations (38,39).

In addition to the potential for teratoma formation by the undifferentiated cells, differentiated iPSCs still carry an intrinsic risk of malignant transformation (97). The original use of retroviruses for induction of pluripotency with integration into the host DNA is one contributing factor. The overexpression of oncogenes, like c-Myc, used in the original iPSCs reprogramming protocol, carries another uncertainty. This has led to modifications of the original technique to induce pluripotency without using retroviral vectors (81). The current use of the RNA non-integrating modified Sendai virus eliminates the potential risk of genomic integration and maintains good transduction efficacy (98).

Future directions for cardiovascular regeneration

Despite the limited innate ability of the injured myocardium and vasculature to regenerate, the implementation of iCMs and iECs holds promise for regenerative medicine. Simpson et al succeeded in constructing a biologically active human pulmonary valve from a decellularized valve that was seeded with iPSC-derived mesenchymal stem cells (99). Also, combining bioengineering technology with iPSC-derivatives to construct engineered tissue may be more effective than direct intramyocardial injection to limit infarct expansion and adverse remodeling, leading to heart failure (22,42).

Direct reprogramming or transdifferentiation, whereby terminally differentiated cells such as cardiac fibroblasts are changed into cardiomyocytes without first producing a pluripotent intermediate, may be an alternative strategy. Transdifferentiation has been known for decades. It was defined by Pritchard in 1978 as “the ability of a cell to lose a definitive characteristic and to acquire another feature characteristic of an alternate state” (100). The advent of iPSC technology has revolutionized the field of transdifferentiation by demonstrating that biological development is not an irreversible process. The discovery demonstrated that the individual cell function is largely dictated by changes in gene expression within each individual tissue or cell. Inspired by Yamanaka’s experimental findings (6), Ieda et al. tested 14 key transcription factors for early heart development to reprogram fibroblasts into cardiomyocytes-like cells (101). They were able to convert mouse postnatal cardiac or dermal fibroblasts into functional beating cardiomyocytes in vitro using a combination of three transcription factors, Gata4, Mef2c, and Tbx5 (GMT) (101). In 2012, in vivo delivery of GMT transcription factors using a gene therapy approach converted mouse non-myocytes into induced cardiomyocytes with improved cardiac function and reduced scar size after MI (102,103). Compared to the in vitro induced cardiomyocytes, in vivo induced cells appeared more similar to endogenous cardiomyocytes, suggesting the importance of in-vivo environmental cues like electromechanical stimulation, signaling pathways and extra-cellular matrix (104). This approach appears promising but carries significant limitations, including low efficiency, incomplete reprogramming, lack of robust experimental reproducibility, and the use of retroviral vectors in vivo (105). Greater understanding of the epigenetic changes associated with direct reprogramming is needed to enhance its therapeutic potential.

Similarly, Margariti et al (106) have described partial reprogramming of fibroblasts directly into iECs using Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc, and endothelial cell-specific media and culture conditions. These cells were able to repopulate decellularized vessel scaffolds with appropriate vascular structure and good attachment. However, this model still requires viral transduction. Moving away from this approach entirely, Lee and colleagues have described the role of innate immunity in nuclear reprogramming (107) and have gone on to demonstrate that using a toll-like receptor 3 agonist and exogenous endothelial cell growth factors, fibroblasts can be induced into ECs (108). When transplanted into a murine ischemic hind limb model, these ECs led to neovascularization and improved limb perfusion. Ultimately, safe, effective, and reproducible large-animal models will be necessary for eventual clinical translation.

iPSCs for disease modeling and drug discoveries

iPSCs have an emerging role in modeling human diseases at the cellular level and in facilitating new drug discoveries. Modeling of human diseases contributes to our understanding of the underlying pathophysiology, development of novel therapeutics, and evaluation of therapeutic efficacy and toxicity. Currently available disease models rely mainly on in vitro human cell lines and animal models for human diseases. The inherent limitations of this paradigm have hindered rapid advances in the understanding of many disease processes and their subsequent treatment. Similarly, multicenter clinical trials do not address the inter-individual genetic variations that will necessitate larger number of participants with resultant increased time and cost.

The introduction of human iPSCs as a source of in vitro disease models has added a new dimension to the current biomedical research tools. Shortly after the discovery of human iPSCs, Park et al were able to prepare disease-specific iPSC lines in culture from patients with genetic disease, both with Mendelian and complex inheritance (109). Modeling rare genetic diseases like long QT syndrome (110), Leopard syndrome (111), and familial dilated cardiomyopathy (112) using patient-derived iPSCs provided a deeper insight into the molecular mechanisms and signaling pathways responsible for disease phenotype. Obtaining peripheral blood cells or skin biopsy from patients with rare genetic heart diseases enables researchers to model the disease in vitro. The molecular mechanism of different diseases can be thoroughly studied at an individual cellular and genetic level in an unprecedented manner. Integration of patient-derived iPSCs with the advances in bioengineering such as the disease-on-a-chip technology will take these models from an individual cell to the tissue level (113). With such advances, modeling genetic mitochondrial cardiomyopathy on a chip has become a reality (114).

With the development of successful cardiomyocyte differentiation protocols, Moretti et al modeled type 1 long QTc syndrome (LQTS) in vitro. They were able to describe a dominant negative trafficking defect that causes prolonged action potential in ventricular and atrial cardiomyocytes, which are exacerbated upon exposure to catecholamines and attenuated with beta-adrenergic blockers (110). The response to isoprenaline and metoprolol further validates this in vitro model as it correlates with the known effect of these medications in LQTS patients. iPSC-derived disease models not only include genetic abnormalities but also structural heart diseases such as the hypoplastic left heart syndrome (115). A full list of iPSC-derived cardiovascular disease models is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Disease models and drug testing studies of cardiovascular disease

| Disease | Mutation | Aim | Drug tested | Number | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Supravalvular aortic stenosis |

ELN (elastin) |

Modeling +Therapy |

Elastin

recombinant protein |

2 patients 2 controls |

Ge et al (127) |

|

Hypoplastic

left heart syndrome |

N/A | Modeling | Isoproterenol |

1 patient 1 control |

Jiang et al (115) |

| ARVD | PKP2-2057del2 | Therapy | SB216763 |

2 patient 2 controls |

Asimaki (128) |

| ARVD | PKP2 L614P | Modeling | N/A |

1 patient 1 control |

Ma (129) |

| ARVD |

PKP2

c.2484C>T PKP2 c.2013delC |

Modeling | N/A |

2 patients 2 controls |

Kim et al (130) |

|

Familial

dilated cardiomyopathy |

TNNT2-R173W point mutation |

Therapy | Metoprolol |

4 patients 3 controls* |

Sun et al (112) |

|

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy |

MYH7 Arg663His | Modeling |

Verapamil Diltiazem |

5 patients 5 controls* |

Lan et al (131) |

|

LEOPARD syndrome |

PTPN11 T468M | Modeling | N/A |

2 patients 2 controls |

Carvajal- Vergara et al (111) |

| Fredrick’s ataxia |

FXN GAA

triplet repeat expansion |

Modeling | N/A |

2 patients 2 controls |

Hick et al (132) |

| Pompe syndrome | GAA | Therapy |

rhGAA

enzyme 2- 3-methyladenine 3- L-carnitine |

2 patients 2 controls |

Huang et al (133) |

| Barth syndrome |

TAZ

c.517delG TAZ c.328T>C |

Modeling +Therapy |

TAZ modRNA |

2 patients 3 controls* |

Wang et al (114) |

| CPVT | RyR2 P2328S | Modeling | Adrenaline |

1 patient 2 controls |

Kujala et al (134) |

| CPVT | RyR2 S406L | Therapy | Dantrolene |

1 patient 1 control |

Jung et al (135) |

| CPVT | CASQ2 D307H | Modeling | Isoproterenol |

2 patients* 3 controls |

Novak et al (136) |

| CPVT | RyR2 M4109R | Therapy |

Flecainide Thapsigargin |

1 patient 1 control |

Itzhaki et al (137) |

| LQT1 |

KCNQ1

R190Q missense mutation |

Modeling |

Propranolol Isoproterenol |

2 patients 2 controls |

Moretti et al (110) |

| LQT2 | KCNH2 A614V | Therapy | Nifedipine, Pinacidil, Ranolazine, cisapride, IKr blocker E-4031 |

1 patient 1 control |

Itzhaki et al (138) |

| LQT2 | KCNH2 R176W | Modeling | Sotalol |

1 patients 3 controls |

Lahti et al (139) |

| LQT2 | KCNH2 G1681A | Therapy |

PD118057, Nicorandil, β- blocker |

2 patients* 2 controls |

Matsa et al (140) |

|

Timothy syndrome (LQT8) |

CACNA1C G1216A |

Therapy | Roscovitine |

2 patients 2 controls |

Yazawa et al (141) |

Patients from the same family

For drug testing, iPSC-derived disease models can serve as an additional in vitro arm to augment phase II and phase III clinical trials for dose optimization, efficacy, safety, side effects, and drug-drug interaction (28). The signal is measured in terms of physiologic effects such as shortening of the action potential duration, reduction in protein or gene expression, enzymatic activity, cell proliferation, apoptosis, or other measurable signal related to the disease process (116). Testing a small number of candidate drugs is an efficient way to monitor their therapeutic effects. Also, evaluating the effects of hundreds of medical compounds on patient-specific iPSC-derived cells in a systematic, less biased manner is possible using high-throughput drug screening systems (117). Lee et al tested the effect of 6912 compounds on hiPSC-derived neural crest precursors. They found 8 compounds capable of rescuing the gene responsible for familial dysautonomia (117). Another big advantage of using iPSCs for disease modeling and drug discovery is the very small number of patients needed to achieve valid conclusions about disease mechanisms and drug toxicity (Table 1). This will not preclude the need for eventual clinical trials as the final confirmatory step in drug discovery. However, the insights gained from these models are expected to increase the efficiency of the process by decreasing the need for some of the lengthy animal research. Furthermore, the ability to predict a patient’s response may enhance the trial design by shortening the duration and reducing the cost of randomized clinical trials, which may lead the transition to personalized medicine.

Similarly, high-throughput screening systems for drug discovery may be employed to investigate iPSC-derivatives from different tissue types for toxicity and side effects. Using iCMs, Guo et al tested 88 drugs for in vitro arrythmogenicity potential (118). Navarette et al developed an in vitro system to screen for drug-induced arrhythmia using iCMs from a skin biopsy of a 14 year-old volunteer (119). iCMs are currently commercially available for such use. Pharmacokinetic data are also possible by evaluating hepatic metabolism in iPSC-derived hepatocytes. To validate such notion, Takayma et al were able to assess inter-individual differences in the hepatic metabolism and drug response using iPSC-derived hepatocytes like cells (HLC) derived from primary human hepatocytes (PHH) of 12 donors. The cytochrome P450 metabolism of iPSC-HLC was found to correlate highly with the PHH of origin, with preservation of inter-individual differences (120).

Though it remains difficult to model adult-onset diseases like atherosclerotic vascular disease using iPSCs, Adams et al (121) have found that iECs demonstrate functional features that may make them good candidates for understanding the role of ECs in cardiovascular disease and for testing EC-based therapies. Specifically, the authors demonstrated that in response to pro-inflammatory factors, iECs become activated and promote leukocyte transmigration in vitro. When subjected to flow dynamics in vitro that are known to promote or protect against atherosclerosis formation, iECs exhibit behavior similar to what is seen in human models of disease with different expression of mechano-regulated genes.

Limitations to iPSC-derived disease models

Many of the above-mentioned challenges for cardiovascular regeneration are also applicable to iPSC-derived disease models. Genetic alterations during the reprogramming process, incomplete reprogramming, changes induced during passages in culture, and differentiation-induced heterogeneous states of iCM development, including immature iCMs, are limitations of iPSC-derived disease models (122). In addition, there is another set of challenges that are specific to disease modeling. For instance, not all human diseases can be modeled in vitro using iPSCs. It is difficult to recapitulate diseases that depend on complex interactions of multiple genetic and environmental factors or on a long incubation period, such as atherosclerosis and congenital heart disease. At the drug screening level, it is not always possible to measure all toxicities or side effects at the cellular level. Investigation of medication-induced mood changes or long-term side effects in remote tissues will still need clinical human studies and post-marketing research. However, advances in bioengineering technologies such as microfluidics (123), high-throughput single-molecule opto-fluidic analysis (124), and disease on chip technologies (125,126), are expected to overcome some of these limitations. These novel models and experimental constructs will perfuse drug solutions on iPSCs-derivatives, including hepatic, renal, pulmonary, and cardiac cells in series or parallel, to simulate the multisystem interactions within the body and to assess important toxicities and/or side-effects.

Summary and Conclusions

iPSCs represent a promising tool for cardiovascular regeneration, disease modeling, and drug discovery. Despite some encouraging results in preclinical studies using iCMs for cardiac regeneration, long-term engraftment remains challenging and the long-term results are unclear. It is possible that these issues may be ameliorated with the use of alternative delivery methods such as iPSC-based patches. Given the low engraftment and other limitations of iCMs, some of the initial positive preclinical results with iCMs should be interpreted with some skepticism. These studies will require long-term follow-up in preclinical models and eventually phase I clinical trials. As a new emerging technology, the application of iCMs for the treatment of advanced heart failure is maturing rapidly by addressing the major extant challenges, including engraftment, immunogenicity, tumorigenicity, and genetic alterations from reprogramming (42,43). Innovative molecular and bioengineering techniques to enhance cellular engraftment, reduce immunogenicity, eliminate tumorigenicity, identify paracrine factors, and generate mature and homogeneous iCMs have a great potential to lead to successful salvage or regeneration of the injured myocardium and permanent restoration of cardiac function. Similarly, although no clinical trials of iPSCs for vascular disease have been initiated, preclinical studies support optimism for this potential application. However, a host of issues similar to those that plague the application of iCMs for cardiac regeneration in heart failure arise in the application of iECs to the field of vascular regeneration. There is still a strong need to identify novel methods to improve the yield of iPSCs, to enhance production consistency and quality, and to improve regenerative effects following transplantation into tissues. The ability to model human disease in a Petri dish provides a compelling biomedical rationale to pursue this pioneering research.

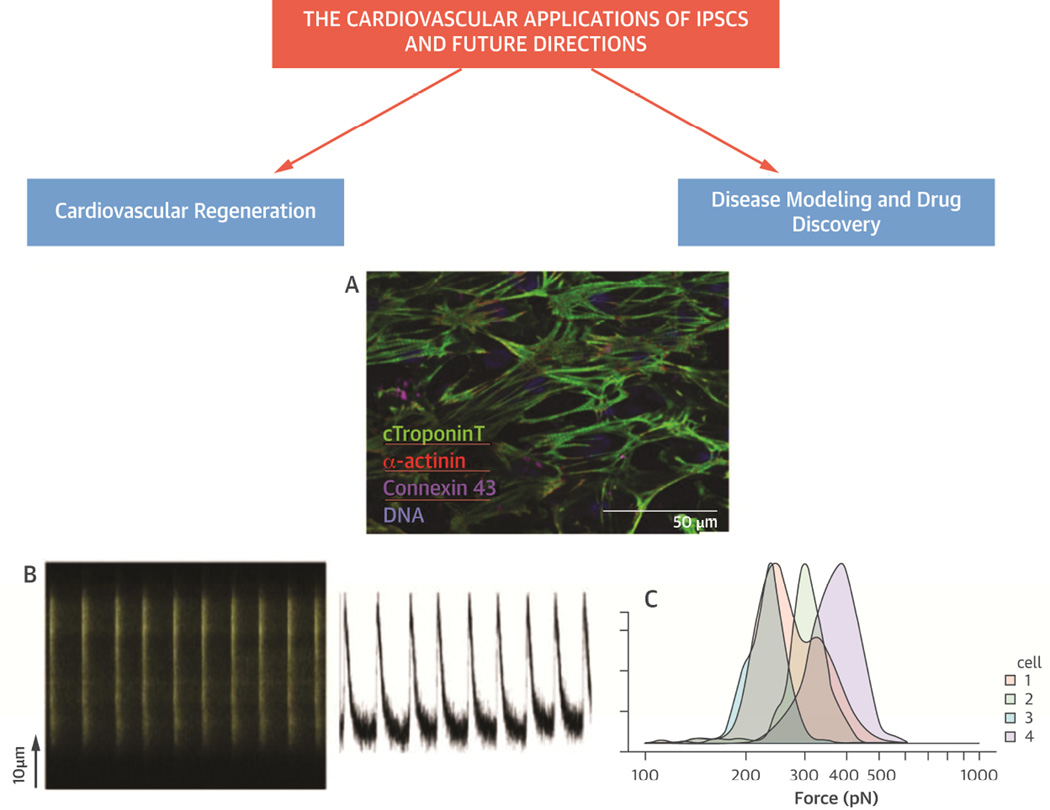

Figure 1.

(A) Immunostain of iPSCs-derived cardiomyocytes in cell culture demonstrate striated pattern of cardiac TNT, α-actinin, connexin 43, and DNA, (B) Calcium metabolism and atomic force microscopy (AFM) demonstrate live-cell calcium imaging of the contractile iCMs, exhibiting regular and synchronous Ca2+ transients (left) with each contractile activity (right), and (C) Histogram of atomic force microscopy to evaluate the force exerted by each contraction of a representative iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes. The maximal contractile force measured for 4 representative beating cells was comparable to that of native cardiomyocytes (150~550 pN).

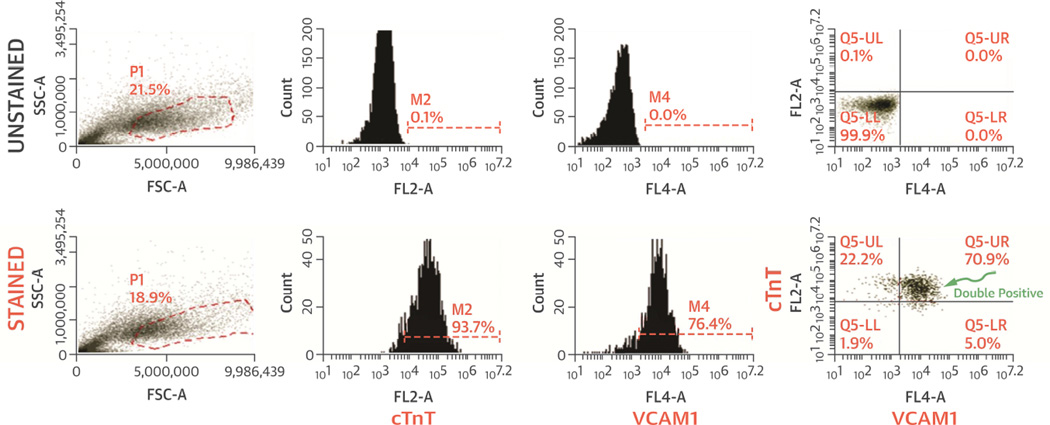

Figure 2.

Flow cytometry analysis of iCM purity. cTnT, VCAM1 and cTnT/VCAM1 double positive cells demonstrate high purity of iCMs. VCAM1 was shown to be a potent cell surface marker for robust, efficient and scalable purification of cardiomyocytes from hESC/hiPSCs (142).

Acknowledgments

Sources of funding: NIH/NHLBI Cardiovascular Cell Therapy (UM1-HL113530, 5UM1-HL087366-07), NHLBI Training Program in Mechanisms and Innovation in Vascular Disease (1T32HL098049-01A1), NIH/NCATS UL1-TR001427, and 1R01 HL125224

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure: None

References

- 1.Briggs R, King TJ. Transplantation of living nuclei from blastula cells into enucleated frogs’ eggs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1952;38:455–463. doi: 10.1073/pnas.38.5.455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gurdon JB, Elsdale TR, Fischberg M. Sexually Mature Individuals of Xenopus laevis from the Transplantation of Single Somatic Nuclei. Nature. 1958;182:64–65. doi: 10.1038/182064a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cowan CA, Atienza J, Melton DA, Eggan K. Nuclear Reprogramming of Somatic Cells After Fusion with Human Embryonic Stem Cells. Science. 2005;309:1369–1373. doi: 10.1126/science.1116447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tada M, Takahama Y, Abe K, Nakatsuji N, Tada T. Nuclear reprogramming of somatic cells by in vitro hybridization with ES cells. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1553–1558. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00459-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hochedlinger K, Jaenisch R. Nuclear reprogramming and pluripotency. Nature. 2006;441:1061–1067. doi: 10.1038/nature04955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okita K, Ichisaka T, Yamanaka S. Generation of germline-competent induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2007;448:313–317. doi: 10.1038/nature05934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, et al. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318:1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wernig M, Meissner A, Foreman R, et al. In vitro reprogramming of fibroblasts into a pluripotent ES-cell-like state. Nature. 2007;448:318–324. doi: 10.1038/nature05944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park IH, Zhao R, West JA, et al. Reprogramming of human somatic cells to pluripotency with defined factors. Nature. 2008;451:141–146. doi: 10.1038/nature06534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aasen T, Raya A, Barrero MJ, et al. Efficient and rapid generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from human keratinocytes. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:1276–1284. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown ME, Rondon E, Rajesh D, et al. Derivation of induced pluripotent stem cells from human peripheral blood T lymphocytes. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11373. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loh YH, Agarwal S, Park IH, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from human blood. Blood. 2009;113:5476–5479. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-204800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giorgetti A, Montserrat N, Aasen T, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from human cord blood using OCT4 and SOX2. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:353–357. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ge X, Wang IN, Toma I, et al. Human amniotic mesenchymal stem cell-derived induced pluripotent stem cells may generate a universal source of cardiac cells. Stem cells and development. 2012;21:2798–2808. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim JB, Greber B, Arauzo-Bravo MJ, et al. Direct reprogramming of human neural stem cells by OCT4. Nature. 2009;461:649–643. doi: 10.1038/nature08436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun N, Panetta NJ, Gupta DM, et al. Feeder-free derivation of induced pluripotent stem cells from adult human adipose stem cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:15720–15725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908450106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou T, Benda C, Dunzinger S, et al. Generation of human induced pluripotent stem cells from urine samples. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:2080–2089. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mauritz C, Schwanke K, Reppel M, et al. Generation of functional murine cardiac myocytes from induced pluripotent stem cells. Circulation. 2008;118:507–517. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.778795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Narazaki G, Uosaki H, Teranishi M, et al. Directed and systematic differentiation of cardiovascular cells from mouse induced pluripotent stem cells. Circulation. 2008;118:498–506. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.769562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawamura M, Miyagawa S, Miki K, et al. Feasibility, safety, and therapeutic efficacy of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocyte sheets in a porcine ischemic cardiomyopathy model. Circulation. 2012;126:S29–S37. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.084343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiong Q, Ye L, Zhang P, et al. Functional consequences of human induced pluripotent stem cell therapy: myocardial ATP turnover rate in the in vivo swine heart with postinfarction remodeling. Circulation. 2013;127:997–1008. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li X, Zhang F, Song G, et al. Intramyocardial Injection of Pig Pluripotent Stem Cells Improves Left Ventricular Function and Perfusion: A Study in a Porcine Model of Acute Myocardial Infarction. PLoS One. 2013;8:e66688. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sanchez-Freire V, Lee AS, Hu S, et al. Effect of human donor cell source on differentiation and function of cardiac induced pluripotent stem cells. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:436–448. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.04.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kamao H, Mandai M, Okamoto S, et al. Characterization of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived retinal pigment epithelium cell sheets aiming for clinical application. Stem Cell Reports. 2014;2:205–218. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanchez Alvarado A, Yamanaka S. Rethinking differentiation: stem cells, regeneration, and plasticity. Cell. 2014;157:110–119. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ko HC, Gelb BD. Concise review: drug discovery in the age of the induced pluripotent stem cell. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2014;3:500–509. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2013-0162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lalit PA, Hei DJ, Raval AN, Kamp TJ. Induced pluripotent stem cells for post-myocardial infarction repair: remarkable opportunities and challenges. Circ Res. 2014;114:1328–1345. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.300556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nelson TJ, Martinez-Fernandez A, Yamada S, Perez-Terzic C, Ikeda Y, Terzic A. Repair of acute myocardial infarction by human stemness factors induced pluripotent stem cells. Circulation. 2009;120:408–416. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.865154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahmed RP, Ashraf M, Buccini S, Shujia J, Haider H. Cardiac tumorigenic potential of induced pluripotent stem cells in an immunocompetent host with myocardial infarction. Regen Med. 2011;6:171–178. doi: 10.2217/rme.10.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim PJ, Mahmoudi M, Ge X, et al. Direct Evaluation of Myocardial Viability and Stem Cell Engraftment Demonstrates Salvage of the Injured Myocardium. Circulation research. 2015 doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.304668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Y, Wang D, Chen M, Yang B, Zhang F, Cao K. Intramyocardial transplantation of undifferentiated rat induced pluripotent stem cells causes tumorigenesis in the heart. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nussbaum J, Minami E, Laflamme MA, et al. Transplantation of undifferentiated murine embryonic stem cells in the heart: teratoma formation and immune response. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2007;21:1345–1357. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6769com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arai T, Kofidis T, Bulte JW, et al. Dual in vivo magnetic resonance evaluation of magnetically labeled mouse embryonic stem cells and cardiac function at 1.5 t. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55:203–209. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahmed RP, Haider HK, Buccini S, Li L, Jiang S, Ashraf M. Reprogramming of skeletal myoblasts for induction of pluripotency for tumor-free cardiomyogenesis in the infarcted heart. Circ Res. 2011;109:60–70. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.240010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buccini S, Haider KH, Ahmed RP, Jiang S, Ashraf M. Cardiac progenitors derived from reprogrammed mesenchymal stem cells contribute to angiomyogenic repair of the infarcted heart. Basic Res Cardiol. 2012;107:301. doi: 10.1007/s00395-012-0301-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burridge PW, Matsa E, Shukla P, et al. Chemically defined generation of human cardiomyocytes. Nat Methods. 2014;11:855–860. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rulifson E, Matsuura Y, Ariyama M, et al. Abstract 19831: In Vivo Molecular Imaging of Human Pluripotent Stem Cell-derived Cardiomyocytes in a Murine Myocardial Injury Model via a Safe Harbor Integration of a Reporter Gene. Circulation. 2014;130:A19831. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pasha Z, Haider H, Ashraf M. Efficient non-viral reprogramming of myoblasts to stemness with a single small molecule to generate cardiac progenitor cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23667. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mauritz C, Martens A, Rojas SV, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived Flk-1 progenitor cells engraft, differentiate, and improve heart function in a mouse model of acute myocardial infarction. European heart journal. 2011;32:2634–2641. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dai B, Huang W, Xu M, et al. Reduced collagen deposition in infarcted myocardium facilitates induced pluripotent stem cell engraftment and angiomyogenesis for improvement of left ventricular function. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:2118–2127. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.06.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang W, Dai B, Wen Z, et al. Molecular strategy to reduce in vivo collagen barrier promotes entry of NCX1 positive inducible pluripotent stem cells (iPSC(NCX(1)(+))) into ischemic (or injured) myocardium. PloS one. 2013;8:e70023. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leeper NJ, Hunter AL, Cooke JP. Stem cell therapy for vascular regeneration: adult, embryonic, and induced pluripotent stem cells. Circulation. 2010;122:517–526. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.881441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Botham CM, Bennett WL, Cooke JP. Clinical trials of adult stem cell therapy for peripheral artery disease. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J. 2013;9:201–205. doi: 10.14797/mdcj-9-4-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cooke JP, Losordo DW. Modulating the vascular response to limb ischemia: angiogenic and cell therapies. Circulation research. 2015;116:1561–1578. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.303565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perin EC, Murphy M, Cooke JP, et al. Rationale and design for PACE: patients with intermittent claudication injected with ALDH bright cells. American heart journal. 2014;168:667–673. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2014.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spinetti G, Kraenkel N, Emanueli C, Madeddu P. Diabetes and vessel wall remodelling: from mechanistic insights to regenerative therapies. Cardiovascular research. 2008;78:265–273. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Asahara T, Kawamoto A. Endothelial progenitor cells for postnatal vasculogenesis. American journal of physiology Cell physiology. 2004;287:C572–C579. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00330.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Clayton ZE, Sadeghipour S, Patel S. Generating induced pluripotent stem cell derived endothelial cells and induced endothelial cells for cardiovascular disease modelling and therapeutic angiogenesis. International journal of cardiology. 2015;197:116–122. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Choi KD, Yu J, Smuga-Otto K, et al. Hematopoietic and endothelial differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem cells (Dayton, Ohio) 2009;27:559–567. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taura D, Sone M, Homma K, et al. Induction and isolation of vascular cells from human induced pluripotent stem cells--brief report. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2009;29:1100–1103. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.182162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lai WH, Ho JC, Chan YC, et al. Attenuation of hind-limb ischemia in mice with endothelial-like cells derived from different sources of human stem cells. PloS one. 2013;8:e57876. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang Y, Hu J, Jiao J, et al. Engineering vascular tissue with functional smooth muscle cells derived from human iPS cells and nanofibrous scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2014;35:8960–8969. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hendry SL, II, van der Bogt KEA, Sheikh AY, et al. Multimodal evaluation of in vivo magnetic resonance imaging of myocardial restoration by mouse embryonic stem cells. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 136:1028.e1–1037.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.12.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hung T-C, Suzuki Y, Urashima T, et al. Multimodality Evaluation of the Viability of Stem Cells Delivered Into Different Zones of Myocardial Infarction. Circulation: Cardiovascular Imaging. 2008;1:6–13. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.108.767343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Terrovitis J, Stuber M, Youssef A, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging overestimates ferumoxide-labeled stem cell survival after transplantation in the heart. Circulation. 2008;117:1555–1562. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.732073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sanganalmath SK, Bolli R. Cell therapy for heart failure: a comprehensive overview of experimental and clinical studies, current challenges, and future directions. Circulation research. 2013;113:810–834. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.300219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li Z, Lee A, Huang M, et al. Imaging Survival and Function of Transplanted Cardiac Resident Stem Cells. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2009;53:1229–1240. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Keith MC, Bolli R. "String theory" of c-kit(pos) cardiac cells: a new paradigm regarding the nature of these cells that may reconcile apparently discrepant results. Circulation research. 2015;116:1216–1230. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.305557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Orlic D, Kajstura J, Chimenti S, et al. Bone marrow cells regenerate infarcted myocardium. Nature. 2001;410:701–705. doi: 10.1038/35070587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Quaini F, Urbanek K, Beltrami AP, et al. Chimerism of the transplanted heart. The New England journal of medicine. 2002;346:5–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Beltrami AP, Urbanek K, Kajstura J, et al. Evidence that human cardiac myocytes divide after myocardial infarction. The New England journal of medicine. 2001;344:1750–1757. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200106073442303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kajstura J, Leri A, Finato N, Di Loreto C, Beltrami CA, Anversa P. Myocyte proliferation in end-stage cardiac failure in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:8801–8805. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, et al. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284:143–147. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Messina E, De Angelis L, Frati G, et al. Isolation and expansion of adult cardiac stem cells from human and murine heart. Circulation research. 2004;95:911–921. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000147315.71699.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro SS, et al. Embryonic Stem Cell Lines Derived from Human Blastocysts. Science. 1998;282:1145–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bergmann O, Bhardwaj RD, Bernard S, et al. Evidence for cardiomyocyte renewal in humans. Science. 2009;324:98–102. doi: 10.1126/science.1164680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.van Berlo JH, Kanisicak O, Maillet M, et al. c-kit+ cells minimally contribute cardiomyocytes to the heart. Nature. 2014;509:337–341. doi: 10.1038/nature13309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Asahara T, Murohara T, Sullivan A, et al. Isolation of putative progenitor endothelial cells for angiogenesis. Science (New York, NY) 1997;275:964–967. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Asahara T, Masuda H, Takahashi T, et al. Bone marrow origin of endothelial progenitor cells responsible for postnatal vasculogenesis in physiological and pathological neovascularization. Circulation research. 1999;85:221–228. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.3.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Huang NF, Niiyama H, Peter C, et al. Embryonic stem cell-derived endothelial cells engraft into the ischemic hindlimb and restore perfusion. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2010;30:984–991. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.202796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hussein SM, Batada NN, Vuoristo S, et al. Copy number variation and selection during reprogramming to pluripotency. Nature. 2011;471:58–62. doi: 10.1038/nature09871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lister R, Pelizzola M, Kida YS, et al. Hotspots of aberrant epigenomic reprogramming in human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;471:68–73. doi: 10.1038/nature09798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li C, Klco JM, Helton NM, et al. Genetic heterogeneity of induced pluripotent stem cells: results from 24 clones derived from a single C57BL/6 mouse. PloS one. 2015;10:e0120585. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Laurent LC, Ulitsky I, Slavin I, et al. Dynamic changes in the copy number of pluripotency and cell proliferation genes in human ESCs and iPSCs during reprogramming and time in culture. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:106–118. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cyranoski D. Stem cells cruise to clinic. Nature. 2013;494:413. doi: 10.1038/494413a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kim K, Doi A, Wen B, et al. Epigenetic memory in induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2010;467:285–290. doi: 10.1038/nature09342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Robinton DA, Daley GQ. The promise of induced pluripotent stem cells in research and therapy. Nature. 2012;481:295–305. doi: 10.1038/nature10761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nakagawa M, Koyanagi M, Tanabe K, et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells without Myc from mouse and human fibroblasts. Nature biotechnology. 2008;26:101–106. doi: 10.1038/nbt1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schlaeger TM, Daheron L, Brickler TR, et al. A comparison of non-integrating reprogramming methods. Nature biotechnology. 2015;33:58–63. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kattman SJ, Witty AD, Gagliardi M, et al. Stage-specific optimization of activin/nodal and BMP signaling promotes cardiac differentiation of mouse and human pluripotent stem cell lines. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:228–240. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lian X, Zhang J, Azarin SM, et al. Directed cardiomyocyte differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells by modulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling under fully defined conditions. Nat Protocols. 2013;8:162–175. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fuerstenau-Sharp M, Zimmermann ME, Stark K, et al. Generation of highly purified human cardiomyocytes from peripheral blood mononuclear cell-derived induced pluripotent stem cells. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0126596. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rufaihah AJ, Huang NF, Kim J, et al. Human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived endothelial cells exhibit functional heterogeneity. American journal of translational research. 2013;5:21–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ribeiro A, Ang Y-S, Fu J, Rivas R, Srivastava D, Pruitt BL. Abstract 13443: Function Follows Form: Shape and Substrate Stiffness Drive Maturity in Human Cardiomyocytes Differentiated From Pluripotent Stem Cells. Circulation. 2014;130:A13443. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhao T, Zhang Z-N, Rong Z, Xu Y. Immunogenicity of induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;474:212–215. doi: 10.1038/nature10135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.de Almeida PE, Meyer EH, Kooreman NG, et al. Transplanted terminally differentiated induced pluripotent stem cells are accepted by immune mechanisms similar to self-tolerance. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3903. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Araki R, Uda M, Hoki Y, et al. Negligible immunogenicity of terminally differentiated cells derived from induced pluripotent or embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2013;494:100–104. doi: 10.1038/nature11807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Guha P, Morgan JW, Mostoslavsky G, Rodrigues NP, Boyd AS. Lack of immune response to differentiated cells derived from syngeneic induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:407–412. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Turner M, Leslie S, Martin Nicholas G, et al. Toward the Development of a Global Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell Library. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13:382–384. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Taylor Craig J, Peacock S, Chaudhry Afzal N, Bradley JA, Bolton Eleanor M. Generating an iPSC Bank for HLA-Matched Tissue Transplantation Based on Known Donor and Recipient HLA Types. Cell Stem Cell. 11:147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Okita K, Matsumura Y, Sato Y, et al. A more efficient method to generate integration-free human iPS cells. Nat Methods. 2011;8:409–412. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gourraud PA, Gilson L, Girard M, Peschanski M. The role of human leukocyte antigen matching in the development of multiethnic "haplobank" of induced pluripotent stem cell lines. Stem Cells. 2012;30:180–186. doi: 10.1002/stem.772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tsuji O, Miura K, Okada Y, et al. Therapeutic potential of appropriately evaluated safe-induced pluripotent stem cells for spinal cord injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:12704–12709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910106107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Takemoto SK, Terasaki PI, Gjertson DW, Cecka JM. Twelve years' experience with national sharing of HLA-matched cadaveric kidneys for transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1078–1084. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200010123431504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lee AS, Tang C, Rao MS, Weissman IL, Wu JC. Tumorigenicity as a clinical hurdle for pluripotent stem cell therapies. Nat Med. 2013;19:998–1004. doi: 10.1038/nm.3267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ban H, Nishishita N, Fusaki N, et al. Efficient generation of transgene-free human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) by temperature-sensitive Sendai virus vectors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:14234–14239. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103509108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Simpson DL, Wehman B, Galat Y, et al. Engineering Patient-Specific Valves Using Stem Cells Generated From Skin Biopsy Specimens. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.04.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Parker KK, Norenberg MD, Vernadakis A. "Transdifferentiation" of C6 glial cells in culture. Science. 1980;208:179–181. doi: 10.1126/science.6102413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ieda M, Fu JD, Delgado-Olguin P, et al. Direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into functional cardiomyocytes by defined factors. Cell. 2010;142:375–386. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Qian L, Huang Y, Spencer CI, et al. In vivo reprogramming of murine cardiac fibroblasts into induced cardiomyocytes. Nature. 2012;485:593–598. doi: 10.1038/nature11044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Song K, Nam Y-J, Luo X, et al. Heart repair by reprogramming non-myocytes with cardiac transcription factors. Nature. 2012;485:599–604. doi: 10.1038/nature11139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Srivastava D, Yu P. Recent advances in direct cardiac reprogramming. Current opinion in genetics & development. 2015;34:77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Yoshida Y, Yamanaka S. Labor Pains of New Technology: Direct Cardiac Reprogramming. Circulation research. 2012;111:3–4. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.271445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Margariti A, Winkler B, Karamariti E, et al. Direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into endothelial cells capable of angiogenesis and reendothelialization in tissue-engineered vessels. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:13793–13798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205526109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lee J, Sayed N, Hunter A, et al. Activation of innate immunity is required for efficient nuclear reprogramming. Cell. 2012;151:547–558. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Sayed N, Wong WT, Ospino F, et al. Transdifferentiation of human fibroblasts to endothelial cells: role of innate immunity. Circulation. 2015;131:300–309. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.007394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Park IH, Arora N, Huo H, et al. Disease-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell. 2008;134:877–886. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Moretti A, Bellin M, Welling A, et al. Patient-specific induced pluripotent stem-cell models for long-QT syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1397–1409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Carvajal-Vergara X, Sevilla A, D'Souza SL, et al. Patient-specific induced pluripotent stem-cell-derived models of LEOPARD syndrome. Nature. 2010;465:808–812. doi: 10.1038/nature09005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sun N, Yazawa M, Liu J, et al. Patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells as a model for familial dilated cardiomyopathy. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:130ra47. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Bhatia SN, Ingber DE. Microfluidic organs-on-chips. Nature biotechnology. 2014;32:760–772. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wang G, McCain ML, Yang L, et al. Modeling the mitochondrial cardiomyopathy of Barth syndrome with induced pluripotent stem cell and heart-on-chip technologies. Nat Med. 2014;20:616–623. doi: 10.1038/nm.3545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Jiang Y, Habibollah S, Tilgner K, et al. An induced pluripotent stem cell model of hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) reveals multiple expression and functional differences in HLHS-derived cardiac myocytes. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2014;3:416–423. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2013-0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Schenone M, Dancik V, Wagner BK, Clemons PA. Target identification and mechanism of action in chemical biology and drug discovery. Nat Chem Biol. 2013;9:232–240. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Lee G, Ramirez CN, Kim H, et al. Large-scale screening using familial dysautonomia induced pluripotent stem cells identifies compounds that rescue IKBKAP expression. Nature biotechnology. 2012;30:1244–1248. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Guo L, Coyle L, Abrams RM, Kemper R, Chiao ET, Kolaja KL. Refining the human iPSC-cardiomyocyte arrhythmic risk assessment model. Toxicological sciences : an official journal of the Society of Toxicology. 2013;136:581–594. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kft205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Navarrete EG, Liang P, Lan F, et al. Screening drug-induced arrhythmia [corrected] using human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes and low-impedance microelectrode arrays. Circulation. 2013;128:S3–S13. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Takayama K, Morisaki Y, Kuno S, et al. Prediction of interindividual differences in hepatic functions and drug sensitivity by using human iPS-derived hepatocytes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111:16772–16777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1413481111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Adams WJ, Zhang Y, Cloutier J, et al. Functional vascular endothelium derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem cell reports. 2013;1:105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Soldner F, Jaenisch R. iPSC Disease Modeling. Science. 2012;338:1155–1156. doi: 10.1126/science.1227682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Psaltis D, Quake SR, Yang C. Developing optofluidic technology through the fusion of microfluidics and optics. Nature. 2006;442:381–386. doi: 10.1038/nature05060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Kim S, Streets AM, Lin RR, Quake SR, Weiss S, Majumdar DS. High-throughput single-molecule optofluidic analysis. Nature methods. 2011;8:242–245. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Agarwal A, Goss JA, Cho A, McCain ML, Parker KK. Microfluidic heart on a chip for higher throughput pharmacological studies. Lab on a chip. 2013;13:3599–3608. doi: 10.1039/c3lc50350j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Grosberg A, Alford PW, McCain ML, Parker KK. Ensembles of engineered cardiac tissues for physiological and pharmacological study: heart on a chip. Lab on a chip. 2011;11:4165–4173. doi: 10.1039/c1lc20557a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Ge X, Ren Y, Bartulos O, et al. Modeling supravalvular aortic stenosis syndrome with human induced pluripotent stem cells. Circulation. 2012;126:1695–1704. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.116996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Asimaki A, Kapoor S, Plovie E, et al. Identification of a new modulator of the intercalated disc in a zebrafish model of arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:240ra74. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Ma D, Wei H, Lu J, et al. Generation of patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes as a cellular model of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:1122–1133. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Kim C, Wong J, Wen J, et al. Studying arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia with patient-specific iPSCs. Nature. 2013;494:105–110. doi: 10.1038/nature11799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Lan F, Lee Andrew S, Liang P, et al. Abnormal Calcium Handling Properties Underlie Familial Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Pathology in Patient-Specific Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:101–113. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Hick A, Wattenhofer-Donze M, Chintawar S, et al. Neurons and cardiomyocytes derived from induced pluripotent stem cells as a model for mitochondrial defects in Friedreich's ataxia. Dis Model Mech. 2013;6:608–621. doi: 10.1242/dmm.010900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Huang HP, Chen PH, Hwu WL, et al. Human Pompe disease-induced pluripotent stem cells for pathogenesis modeling, drug testing and disease marker identification. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:4851–4864. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]