Abstract

Objectives

Our study aimed to determine whether differentially methylated CpGs in synovium-derived fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLS) of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients were also differentially methylated in peripheral blood samples.

Methods

We measured 371 genome-wide DNA methylation profiles from 63 RA cases and 31 controls, in CD14+ monocytes, CD19+ B cells, CD4+ memory T cells and CD4+ naïve T cells, using Illumina HumanMethylation450 (450k) BeadChips.

Results

We found that of 5,532 hypermethylated FLS candidate CpGs, 1,056 were hypermethylated in CD4+ naïve T cells of RA cases compared to controls. Using a second set of CpG candidates based on SNPs from a genome-wide association study (GWAS) of RA, we found one significantly hypermethylated CpG in CD4+ memory T cells and 18 significant (6 hypomethylated, 12 hypermethylated) CpGs in CD4+ naïve T cells. A prediction score based on the hypermethylated FLS candidates had an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.73 associated with RA case status, which compared favorably to the association of RA with the HLA-DRB1 shared epitope (SE) risk allele and with a validated RA genetic risk score.

Conclusion

FLS-representative DNA methylation signatures derived from blood may prove to be valuable biomarkers for RA risk or disease status.

RA is a chronic inflammatory disease with the potential to cause substantial disability, primarily due to the erosive and deforming process in joints. It is the most common systemic autoimmune disease, with a worldwide prevalence approaching 1% (1,2). RA etiology is complex, with both genetic and non-genetic contributions. A rigorous assessment of RA heritability using twin studies suggests that 50–60% of the occurrence of RA in twins is explained by genetic effects (3). Approximately 50% of this genetic contribution can be explained by genes in the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) (3). In addition, at least 101 independent non-MHC risk loci have been identified (4). A role for environmental factors is also supported, but currently exposure to tobacco smoke is the only well-established risk factor (5).

DNA methylation is an epigenetic modification resulting from the addition of a methyl group to a cytosine base at positions in the DNA sequence where a cytosine is followed by a guanine (“CpGs”), which can lead to altered expression of DNA. DNA methylation is essential for proper mammalian development and other functions, and methylation patterns are affected by environmental changes. Methylation status is also influenced by the interaction between genetics and environment, and a growing number of human diseases have been associated with aberrant DNA methylation. (6) Maintenance of DNA methylation is critical for the development and function of immune cells (6,7).

Altered patterns of DNA methylation at CpG sites have been observed in individuals with RA. A 1990 study by Richardson et al. found that global methylation of genomic DNA from T cells of RA patients was lower when compared to T cells of healthy controls (8). Altered methylation patterns have also been observed in small studies of specific genes in RA, including the promoter regions of IL6 using peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and DR3 (alternative name TNFRSF25) using synovial fibroblasts (9,10). Liu et al. studied global DNA methylation among 129 Taiwanese individuals and found that RA patients were characterized by significantly lower levels of DNA methylation in PBMCs compared to controls (11). Recently, Glossop et al. identified about 2,000 differentially methylated CpGs in both T- and B-lymphocytes between treatment-naïve patients with early RA and healthy individuals, and in a separate analysis found that DNA methylation profiles from synovial fluid-derived FLS had similarities with the profiles from tissue-derived FLS (12,13).

A recent investigation identified 15,220 differentially methylated CpG sites in synovium-derived fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLS) between RA patients and either osteoarthritis or normal controls that appear to distinguish RA cases from non-RA controls (Whitaker et al. (14) and personal communication). These 15,220 FLS CpGs are the candidate sites for the current investigation. FLS in the synovial intimal lining of joints have key roles in the production of cytokines that perpetuate inflammation, and the production of proteases that contribute to cartilage destruction in RA (15). An overlap in the methylation pattern between FLS and peripheral blood cells could be indicative of disease-associated biological processes detectable in the periphery. Because peripheral blood is easily accessible, such signatures may be useful biomarkers for RA risk or disease status.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

Participants included 63 female RA cases (18 of age or older and met the 1987 American College of Rheumatology criteria for RA (16,17)) and 31 female unaffected controls (locally based), all of European ancestry. Table 1 summarizes characteristics of our study population. All participants provided a peripheral blood sample for genotyping and measurement of methylation.

Table 1. Study Participant Characteristics at Time of Blood Draw.

This table summarizes study participant characteristics at the time of blood draw.

| Characteristic | Mean +/− SD or Count (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cases (mean +/− SD) or count (%) n=63 | Controls (mean +/− SD) or count (%) n=31 | P-value (Wilcoxon or Chi Square) | |

| Seropositive (RFA or CCP positiveB) | 57 (90%) | ----------------- | ----------- |

| Age | 56.4 +/− 14.8 | 57.5 +/− 16.5 | 0.77 |

| Smoking (Ever, Never) | 33 (52%), 30 (48%) | 13 (42%), 18 (58%) | 0.34 |

| Smoking (Current, Not Current) | 4 (6%), 59 (94%) | 1 (3%), 30 (97%) | 0.53 |

| Disease duration, years | 14.0 +/− 10.5 | ----------------- | ----------- |

| Erosive disease (present, absent, missing) | 39 (62%), 22 (35%), 2 (3%) | ----------------- | ----------- |

| Disease activity: CDAIC | 10.1 +/− 9.2NAD=4 | ----------------- | ----------- |

Rheumatoid Factor,

Anti-cyclic Citrullinated Peptide,

Clinical Disease Activity Index,

Not Available

Genotyping

Study participants were genotyped using Illumina HumanOmniExpress, HumanOmniExpressExome, or Human660W-Quad Beadchips, which were read on an Illumina HiScan array scanner. Genotype results were merged using PLINK v1.07 (18), and only SNPs assessed by all three chips were retained for analysis. SNPs with failed genotype calls in 10% or more of individuals, with a minor allele frequency of less than 1%, or found to not be in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (p ≤ 0.000001) in controls were removed from analysis.

Ancestry

EIGENSTRAT (19) was used to visualize ancestral clustering of the study population relative to individuals from 11 HapMap populations (20). Self-identified individuals of European ancestry clustered with Utah residents with ancestry from northern and western Europe/Tuscans in Italy (CEPH/TSI) as expected. We excluded self-reported individuals not of European ancestry because of the potential for confounding. Figure S3 shows the ancestral clustering of our final sample of self-identified European-ancestry participants.

Cell Sorting

Whole blood was collected in four 10ml EDTA collection tubes from each subject. PBMCs were isolated using Ficoll-Paque density gradient and stained with conjugated monoclonal antibodies against CD45 FITC, CD19 PE, CD45RA PE-CY7 (all BD Pharmingen), CD3 Brilliant Violet 421, CD4 CF594 (both BD Horizon), CD14 APC (BD Biosciences) and CD27 APC-eFlour780 (ebioscience). Cells were then stored overnight in buffer at 4°C and sorted the following day, on a BD FACSAria cell sorter (BD Biosciences). The following populations were gated for sorting following exclusion of debris and doublets: monocytes (CD45+CD14+); B cells (CD45+CD14-CD3-CD19+); naïve CD4+ T cells (CD45+CD14-CD19-CD3+CD4+CD27+CD45RA+) and memory CD4+T cells (CD45+CD14-CD19-CD3+CD4+CD45RA-). Cell counts and purity checks were performed after sorting, and then cells were stored frozen as a pellet at −80°C.

Validation of overnight cell storage

To enable DNA methylation profiling of a large number of FACS samples, a protocol for storing blood samples overnight prior to sorting was established and validated. Whole blood was collected in ten 10ml EDTA collection tubes from a single individual. PBMCs were isolated and stained as described above, and then either sorted the same day or stored overnight in buffer at 4°C and sorted the following day. Paired DNA samples from the two time points were collected from all four cell types. All DNA samples were quantified using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer. All samples underwent bisulfite conversion on the same day and were assayed on Illumina 450k BeadChips simultaneously.

Methylation

A total of 371 genome-wide DNA methylation profiles were generated using the Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip kit and read on an Illumina HiScan array scanner. A β value, the ratio of the methylated probe intensity to the overall (methylated plus unmethylated) intensity, was derived for each CpG site. We performed an extensive QC process: Illumina GenomeStudio software was used to examine Jurkat controls, between chip/within chip variation, and replicate samples. All replicate samples had r2 values greater than 0.99 and Jurkat replicates showed r2 greater than 0.98. Background signal was subtracted using the methylumi R package “noob” method (21) and samples were normalized with All Sample Mean Normalization (ASMN) (22) followed by beta-mixture quantile normalization (BMIQ) (23) to correct for type I and type II probe differences. Multidimensional scaling (MDS) plots for each cell type before and after background subtraction and normalization were examined to assess for the presence of batch effects. Batch effects were found to be minimal, and were reduced following data normalization (see Figures S4 and S5 for an example). 286 CpG sites with low detection rates (read p>0.05) in more than 20% of samples were removed from analysis, and one sample with low detection rates (read p>0.05) in more than 20% of sites. The following CpG sites were also removed from analysis: the 65 non-CpG “rs” SNP probes included in the 450k BeadChip, 30,969 sites with probes predicted to hybridize to more than one location in the genome after bisulfite conversion (“cross-reactive probes”) identified by Chen et al., and 28,355 sites with a known polymorphism at the site being measured (“polymorphic CpGs”) identified by Chen et al. that were either present in our European-ancestry population or present in Europeans in the 1,000 Genomes Project (24). The final data set used for analysis consisted of 428,232 CpG sites in 371 samples (94 CD14+ monocyte samples, 91 CD19+ B cell samples, 94 CD4+ memory T cell samples, and 92 CD4+ naïve T cell samples).

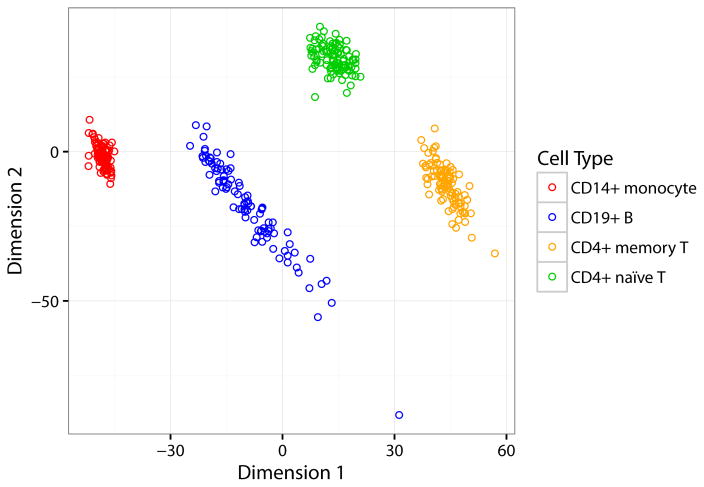

An MDS plot of all 371 samples (Figure 3) shows that each of the four immune cell types cluster together as expected based on their DNA methylation patterns. Differences in methylation among different cell types are much larger than the differences between cases and controls within each cell type, as expected. There is greater scattering for B cells, which is reflective of the diversity of that cell type, versus monocytes and the T cell subpopulations examined in this study.

Figure 3. Multidimensional scaling (MDS) plot of DNA methylation profiles.

This MDS plot of 371 samples (four immune cell types each for RA cases and controls) shows that samples cluster according to cell type, as expected.

Wilcoxon Rank Sum Tests

Four immune cell types were assayed for each individual: CD14+ monocytes, CD19+ B cells, CD4+ memory T cells, and CD4+ naïve T cells. DNA hypermethylation or hypomethylation in RA cases relative to controls consistent with methylation differences seen in FLS was evaluated separately for each immune cell type. For each of the hypermethylated (n=5,532) and hypomethylated (n=8,406) candidate CpGs from the FLS study, we used a one-tailed Wilcoxon rank sum test to assess differences in the median β value between RA cases and controls. P-values were adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg method for controlling the false discovery rate (25). We controlled the error rate for 5,532 or 8,406 tests, depending on the candidate list. Methylation changes at a second set of 1,788 candidate CpG sites in 98 genes deemed likely to be important to RA biology based on a recent genome-wide association study (GWAS) meta-analysis of >100,000 subjects (4) were also evaluated, and an exploratory association analysis was conducted using all CpGs on the 450k BeadChip. For the GWAS candidate CpGs and the chip-wide tests, we used a two-tailed Wilcoxon rank sum test, controlling for 1,676 tests and 428,232 tests, respectively.

ReFACTor Principal Component

In order to determine whether cell subtype proportions in the sorted cells were confounding results, we performed Reference-Free Adjustment for Cell-Type composition (26) (ReFACTor), in which principal component (PC) analysis is performed on a subset of sites that are informative with respect to the cell composition in the data. ReFACTor finds the most informative sites in an unsupervised manner. To measure the potential confounding, we examined quantile-quantile (QQ) plots for each cell type for a standard epigenome-wide association study (EWAS), using only the methylation sites with a mean methylation level in the range of 0.2–0.8, following a suggestion of Liu et al. to remove consistently methylated and consistently unmethylated probes when performing EWAS (27). Deflation was observed in the QQ-plots of all cell types except CD4+ naïve T cells, implying deficient power. To assess the expected QQ-plot under the condition of power deficiency, we permuted the phenotype and repeated the EWAS analysis, and repeated this procedure 100 times for each cell type. To determine whether a correction was required in the cell types, we used the genomic control lambda measurement of inflation (28). We considered the median lambda of the 100 EWAS executions as the expected lambda. The approach was to add ReFACTor PCs to the analysis until the inflation was corrected with respect to the expected lambda (29). Only the CD4+ naïve cells were found to be inflated, and adjusting for the first ReFACTor component removed this inflation, suggesting possible cell substructure in the CD4+ naïve cells. ReFACTor was executed on the CD4+ naïve T cell data with parameter K=2. We added the first PC (PC1) in logistic regression models to evaluate results that are adjusted for confounding by cell substructure.

Logistic Regression Models

To evaluate possible confounding effects, logistic regression models of RA case status were carried out against each FLS CpG that was significant at q<0.05 in the Wilcoxon tests (1,056 models), adjusting for smoking, age, batch (date the plate was run), and PC1 calculated from the ReFACTor analysis described above, which aims to quantify cell substructure (26). Unadjusted models were compared to models adjusted for age only; ever having smoked only; batch only; ReFACTor PC1 only; age, smoking and batch combined; and age, smoking, batch and ReFACTor PC1 combined.

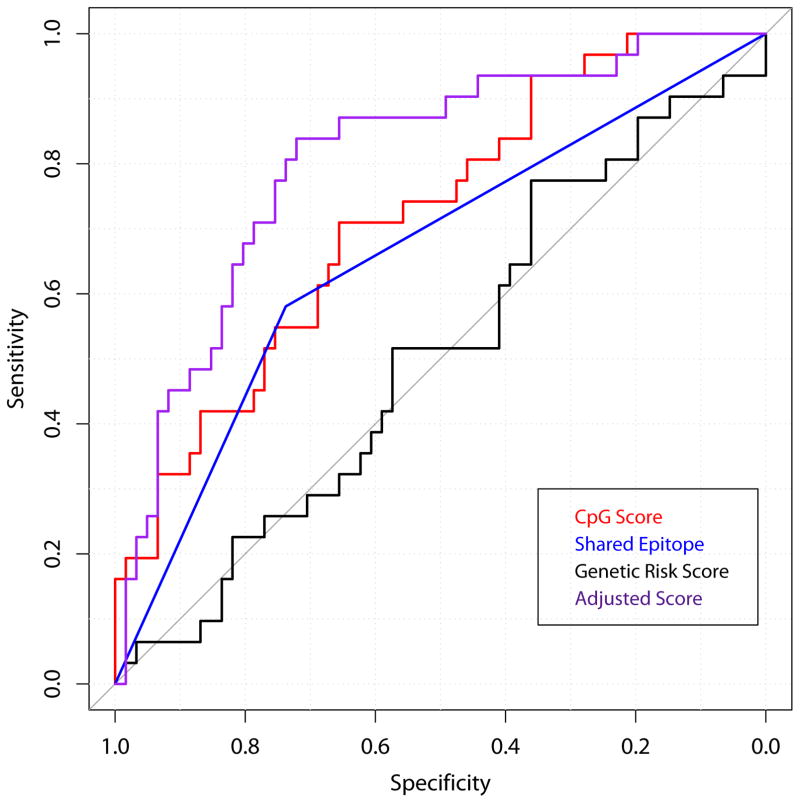

ROC curve analyses

Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was used to explore the potential for the FLS sites to serve as a biomarker for the RA disease process, compared to the potential of a validated genetic risk score for RA (30,31) and the presence or absence of HLA-DRB1 shared epitope alleles (32,33). The hypermethylation score for each person was calculated by summing the beta values across the 1,056 FLS significantly differentially methylated loci. A continuous weighted genetic risk score was also calculated, based on the publications by Yarwood et al. (31) and Eyre et al. (30) The genetic risk score included 43 of the 45 non-HLA SNPs (rs13397 and rs59466457 were missing), and it was calculated by multiplying the number of copies of risk alleles, using probability data from genome-wide imputation, for each SNP by the natural logarithm of the odds ratio as reported in Eyre et al. (30), and summing these values across the 43 SNPs for each person. Presence of the shared epitope was coded as a binary variable. Individuals with one or more copies of the following alleles were assigned a value of one for the shared epitope: HLA-DRB1*0101, *0102, *0401, *0404, *0405, *0408, or *1001 (34). The pROC package in R was used to plot each of these variables as a predictor with RA case-status as the response variable (35).

To determine the influence of adjusting for potential confounders of the hypermethylation score, we created two additional hypermethylation scores: the first based on the 830 FLS sites that remained significant (p<0.05) in the logistic regression models after adjusting for age, smoking, and batch, and the second based on the 79 FLS sites that remained significant (p<0.05) after adjusting for age, smoking, batch and ReFACTor PC1.

Study Approval

Written informed consent was received from all participants prior to inclusion in this study, and research was in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration. Institutional Review Board approval was in place at UC San Francisco where study subjects were recruited.

Results

Validation of overnight cell storage

Methylation profiles for isolated cell populations were not impacted by overnight storage (correlation between profiles derived from all paired samples was very high (r2>0.997)). Details are summarized in Supplementary Text 1.

Candidate FLS CpG results

After adjusting p-values from the Wilcoxon rank sum tests for multiple testing by controlling the false discovery rate (FDR; p-values adjusted for multiple testing hereby referred to as q-values), 1,056 significantly hypermethylated CpG sites in CD4+ naïve T cells had q<0.05 (Table S1). There were no significant sites at this threshold for the hypomethylated candidates in CD4+ naïve T cells, nor in any of the remaining cell types (CD14+ monocytes, CD19+ B cells and CD4+ memory T cells), for either the hyper- or hypomethylated candidates. Results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Candidate FLS CpG Results.

Wilcoxon rank sum tests were carried out for each FLS candidate CpG in each of the four cell types with one-sided p-values, according to whether the CpG was hypermethylated or hypomethylated in the original study.

| Cell Type | Raw p<0.05 | Absolute median diff > 10%A | Absolute median diff between 1% and 10%A | FDR q<0.05 | FDR q<0.05 and median diff > 1% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD14 Hypomethylated | 263 | 4 | 175 | 0 | 0 |

| CD14 Hypermethylated | 100 | 0 | 61 | 0 | 0 |

| CD19 Hypomethylated | 96 | 1 | 59 | 0 | 0 |

| CD19 Hypermethylated | 1408 | 1 | 732 | 0 | 0 |

| CD4 Memory Hypomethylated | 262 | 0 | 204 | 0 | 0 |

| CD4 Memory Hypermethylated | 66 | 1 | 36 | 0 | 0 |

| CD4 Naïve Hypomethylated | 160 | 1 | 62 | 0 | 0 |

| CD4 Naïve Hypermethylated | 2,569 | 0 | 1,105 | 1,056 | 517 |

Absolute median difference numbers are among the CpGs with unadjusted p<0.05

Logistic Regression Results

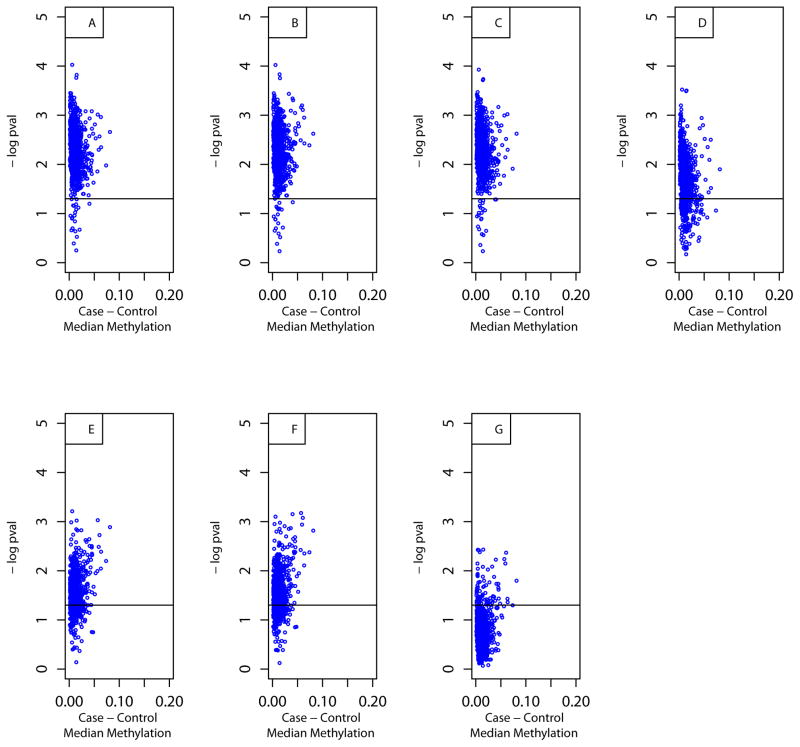

Logistic regression analysis was conducted with RA case status as the outcome and methylation beta value as the predictor variable for each of the 1,056 FLS CpG. 1,035 CpGs were significant (p<0.05, one-sided) in the unadjusted model, 830 remained significant when adjusting for age, smoking and batch together, and 79 remained significant when adjusting for age, smoking, batch, and ReFACTor PC1. Results are summarized in Table S2, and the shifts in p-values with different models are visualized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Figure 2A–G. Plots of one-sided p-values vs. median methylation difference in cases and controls for FLS CpGs in logistic regression models after adjusting for covariates.

CpGs in the models are those significant at q<0.05 in Wilcoxon rank sum tests. Models are adjusted for (A) no covariates, (B) age only, (C) smoking only, (D) batch only, (E) ReFACTor PC1 only, (F) age, smoking and batch together, and (G) age, smoking, batch, and ReFACTor PC1 together, respectively.

Comparison of Methylation Profiles to Shared Epitope and Genetic Risk Score

The association of hypermethylation in CD4+ naive T cells with RA was compared to a weighted genetic risk score for non-HLA risk alleles, and presence or absence of the HLA-DRB1 shared epitope, a major genetic risk factor for RA (36). The hypermethylation score and shared epitope models performed similarly. Figure 1 shows the three ROC curves and Table 3 summarizes the point estimates and 95% confidence intervals for the area under the curve (AUC) for each model. The hypermethylation score had the largest AUC of 72% (61%–83%). The shared epitope had an AUC of 66% (56%–76%), and the genetic risk score had an AUC of 51% (38%–63%). The AUC for the hypermethylation score based on the 830 CpGs significant at p<0.05 after adjusting for age, smoking, and batch in the logistic regression models was 71.8% (61.0%–82.7%), which is similar to the hypermethylation score using unadjusted CpGs significant after the Wilcoxon test. The AUC using only the 79 CpGs significant after adjusting for age, smoking, batch, and ReFACTor PC1 was 80.7% (71.3%–90.1%). Results are summarized in Table 3.

Figure 1. ROC curves of hypermethylation score, HLA-DRB1 shared epitope, and genetic risk score as predictors of RA case status.

The hypermethylation score is the sum of the beta values across the 1,056 significant CD4+ naïve T cell sites and is a measure of hypermethylation. Shared epitope is a binary variable taking on the value of 1 if a person has 1 or 2 copies of the shared epitope. Genetic risk score is a weighted score of 43 SNPs, previously validated (30,31). The adjusted hypermethylation score represents the sum of the 79 CpGs that were significant (p<0.05) after adjusting for age, smoking, batch and ReFACTor PC1.

Table 3. ROC Areas Under the Curve.

ROC analysis was carried out for a hypermethylation score based on the 1,056 CpG sites significant at q<0.05 from the Wilcoxon rank sum tests. This score was compared to shared epitope status (positive/negative) and a genetic risk score. Two other hypermethylation scores were constructed, based on the 1,056 CpGs that remained significant (p<0.05) in logistic regression models after adjusting for various covariates.

| Model | AUC (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Hypermethylation Score (1,056 sites) | 72% (61%–83%) |

| Shared Epitope | 66% (56%–76%) |

| Genetic Risk Score | 51% (38%–63%) |

| Hypermethylation Score (830 sites; Age, Smoking, Batch Adjusted Regression) | 72% (61%–83%) |

| Hypermethylation Score (79 sites; Age, Smoking, Batch, ReFACTor PC1 Adjusted Regression) | 81% (71%–90%) |

Candidate GWAS CpG results

For this set of Wilcoxon rank sum tests (1,676 CpGs), one CpG (hypermethylated) in CD4+ memory cells and 18 CpGs (6 hypomethylated, 12 hypermethylated) in CD4+ naïve T cells were significantly associated (q<0.05) with RA susceptibility. Results are summarized in Table S4. We also carried out logistic regression analysis using RA status as outcome for each of the 18 CpGs that were differentially methylated in CD4+ naïve T cells, adjusting for various covariates. Results are summarized in Table S5.

Genome-wide results

Results of the genome-wide tests of differences in methylation are summarized in Table S6. No CpG sites were significantly differentially methylated after multiple testing correction (adjusting the p-value for 428,232 tests). Differences in global methylation were investigated by comparing mean methylation levels in cases and controls (Table S7). No significant differences were observed for any cell type.

Discussion

In the current study, hypermethylated CpG sites previously identified in FLS of RA cases relative to osteoarthritis or healthy controls were also distinguished in CD4+ naïve T cells from peripheral blood of RA cases relative to healthy controls. Our results show a disease-associated signature can be observed in cells obtained from whole blood, which is more accessible for clinical or epidemiologic studies compared to synovial fluid.

Our work extends recent findings demonstrating DNA methylation profiles in peripheral blood mononuclear cells differ between RA cases and controls (12). While Glossop et al. observed differences in both B-lymphocytes and T-lymphocytes, most results from the current study were confined to CD4+ naïve T cells. However, taken together, the combined findings increase the evidence that peripheral blood cells contain a DNA methylation signature that can distinguish RA cases from controls. Furthermore, the identification of DNA methylation profile differences in T cells detected in treatment naïve patients by Glossop suggests there are methylation changes important in RA that are not a consequence of medication or long disease duration.

The 1,056 differentially methylated candidate FLS CpGs associated with RA in this study were limited to the CD4+ naïve T cell population. Most of the observed differences were small, with a difference in median β value of less than 10% between RA cases and controls. Of the 1,056 sites, 517 had a methylation difference of greater than 1% (Table S1). These 517 sites resided in 357 genes as well as intergenic regions, and across all chromosomes. It is uncertain what effect size is biologically meaningful for DNA methylation. Some researchers impose a threshold of 5% or 10% difference in methylation to consider results relevant (37), while others include modest effect sizes (38). One recent study showed replicable methylation differences associated with smoking ranging from 1.2% to 24% (39). Though differences in this study were small, they were robust, surviving stringent multiple testing correction. A hypermethylation score constructed from the significant 1,056 sites predicted RA case status with an AUC of 73%, and awaits validation in an independent dataset. The hypermethylation score based on the 830 CpG sites with p<0.05 after adjusting for smoking, age, and batch in the logistic regression models had a similar AUC of 71.8%, suggesting the score was not strongly influenced by these covariates. The hypermethylation score calculated using the 79 CpG sites with p<0.05 after adjusting for smoking, age, batch and ReFACTor PC1 in the logistic regression models had a slightly higher AUC of 80.7%, suggesting that adjustment for possible cell substructure may improve the ability of our FLS CpG sites score to serve as a biomarker for RA. Because DNA methylation was measured subsequent to RA diagnosis, we cannot tell with certainty whether the FLS methylation signature in the CD4+ naïve T cells predicts RA diagnosis or is a biomarker of the disease process.

One of the top 10 (most significant p-value) CD4+ naïve T cell replicated sites, cg21480173, was found in the gene TYK2, which has been associated with RA and other autoimmune diseases (40). The remaining 9 top hits were found in the following genes: PRKAR1B, ABCC4, COMT, CAI2, MCF2L, GALNT9, C7orf50, or non-gene regions, which have not been previously associated with RA. Results demonstrate that novel genes related to RA may be discovered through DNA methylation analysis. We also observed differential methylation in CpG sites that reside in genes that have previously been associated with RA (4). For example, two of the CpGs reside in the promoter regions for both GATA3 and GATA3-AS1 (cg17566118 and cg15852223), and both are hypomethylated in RA cases relative to controls. It is important to note our results were not due to genetic variation or genetic ancestry differences between cases and controls.

The lack of significant findings in cell types other than CD4+ naïve T cells suggests that CD4+ naïve T cells are particularly relevant to RA through epigenetic mechanisms involving DNA methylation. There is strong evidence from previous studies that aberrant T-cell activation pathways are involved in the pathogenesis of RA, including in the naïve T cell population, which have not yet participated in immune responses (41). CD4+ naïve T cells from RA patients have been shown to have premature senescence; to be defective in up-regulating telomerase due to deficiencies in telomerase component human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT); to have increased DNA damage load and apoptosis rates; to not metabolize equal amounts of glucose as healthy control cells of the same age; and to generate less ATP (42–45). While our methylation findings need to be replicated, the striking CD4+ naïve T cell results, and the existing literature on abnormalities in this cell population in RA, suggest that the methylation changes we observed may be involved in disease pathogenesis. However, it is also plausible that methylation changes are a response to the disease process itself or a result of exposure to medications. Additional studies involving patients with early or pre-clinical disease will be required to determine when in the course of the disease process such differential methylation patterns occur. Longitudinal studies may also help elucidate why results from the current study support a hypermethylation signature in RA, in contrast with hypomethylation which has been demonstrated in previous studies (8,11). Hypermethylation may occur at a specific point along the course of RA, or may be specific to the FLS-associated sites rather than the global methylome.

Results from logistic regression modeling suggest that although some variables are confounding the relationship between methylation and RA case status, evidence for association persists. Specifically, adjusting for age or smoking did not markedly impact the number of FLS CpGs that were significantly associated with RA at p<0.05. Adjusting for batch or ReFACTor PC1 reduced the number of statistically significant CpGs by ~ 200, but many remained statistically significant (841 adjusting for batch, 837 adjusting for ReFACTor PC1). Even when controlling for all four of these variables, 79 CpGs remained significant. Figure 2 visually represents the shifting of p-values across these regression models. Evidence for association also persisted in analysis of GWA candidates, even in fully adjusted models (Table S5).

Strengths and Limitations

This study has many strengths. DNA methylation profiles were analyzed in four sorted cell types for 94 individuals who are all females of European ancestry, which reduced the genetic heterogeneity of the study population. Examination of individual cell types from FACS-sorted blood allowed us to measure methylation results with more confidence, rather than relying on whole blood and cell type proportions (46). Restriction of the study to females eliminates the possibility of confounding by sex. Also, since RA affects women at a 3:1 ratio relative to men, results are generalizable to the group that experiences the greatest disease burden.

Stringent quality control of the methylation data, as described in the methods, is another strength. In addition to standard QC steps of background subtraction, normalization, and removal of sites with low quality scores, CpG sites with known SNPs in individuals of European ancestry at the cytosine or guanine being measured on the 450k BeadChip were removed, which is important because methylation measurements for CpG sites harboring SNPs are likely to simply reflect genetic polymorphism at that site rather than truly measuring methylation. We also removed from analysis CpG sites with cross-reactive sequencing probes on the 450k BeadChip, i.e., probes that could hybridize to more than one location in the genome and reflect methylation at two different genomic locations rather than only the intended target site. Rigorous quality control measures increase confidence that the observed differential methylation is an accurate reflection of the disease biology and not due to artifacts.

Both whole genome and whole methylome data were utilized in the current study. The whole genome data allowed us to determine genetic ancestry for all participants. The original FLS study by Whitaker et al. involved anonymous samples, and the authors did not have ethnicity or race information (14). Therefore, it is possible that we are underestimating the overlap between FLS and CD4+ naïve sites if we are comparing different ethnicities in the CD4+ naïve T cell and FLS group. Lastly, we were able to demonstrate that even after controlling for age, smoking, batch and possible cell substructure (ReFACTor PC1), a number of FLS and GWA candidate sites remain significantly associated with RA.

This study also has limitations. We could not assess temporality between methylation and case-status. Results may be confounded by case-specific factors such as medication and inflammation. Indeed, other studies have observed associations between methylation and medications (47,48); however, the case-control nature of the current study did not allow us to adjust for effects of RA medications since they were present only among RA cases.

Our findings are restricted to CpG sites that are represented on the 450k BeadChip. The BeadChip prioritized inclusion of features such as RefSeq genes; CpG Islands, shores and shelves; areas of the genome such as the MHC region; and sites known to be in important to cancer (49,50). Therefore, additional CpG sites relevant to RA may be missing. Further, although our ROC analysis demonstrates that differential methylation of about 1,000 CpGs in peripheral blood has the potential to distinguish RA cases from controls, our hypermethylation score needs to be tested as a predictor in an independent data set.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. FLS Candidate Sites Replicated in CD4 Naïve Cells in Peripheral Blood of RA Cases.

Table S3. Candidate CpGs from Genes Previously Associated with RA.

Supplementary Text 1: Results of Overnight Cell Storage

Figure S1. Eigenvector 1 and 2 from EIGENSTRAT in all samples.

Figure S2. Eigenvector 2 and 3 from EIGENSTRAT in all samples.

Figure S3. Eigenvector 1 and 2 from EIGENSTRAT in European ancestry samples.

Figure S4. MDS of CD4+ naïve T cells before normalization.

Figure S5. MDS of CD4+ naïve T cells after normalization.

Table S2. Logistic Regression Results from Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test FLS Sites

Table S4. Candidate GWAS CpG Results

Table S5. Logistic Regression Results Using 18 Significant CpGs from Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test, GWA Sites

Table S6. Genome-wide Results.

Table S7. Mean Methylation in RA Cases and Controls.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Rheumatology Research Foundation “Within Our Reach” grant and Health Professional Research Preceptorship, the Arthritis Foundation, and the Rosalind Russell/Ephraim P. Engleman Rheumatology Research Center at the University of California, San Francisco. The FLS study was funded by the Rheumatology Research Foundation, Arthritis Foundation, and 1R01 AR065466 from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (GSF). We thank Vladimir Chernitskiy for his assistance in data acquisition.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have declared that no conflicts of interest exist.

References

- 1.Cojocaru M, Cojocaru I, Silosi I, Vrabie C, Tanasescu R. Extra-articular manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis. Maedica (Buchar) 2010;5:286–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gabriel SE, Michaud K. Epidemiological studies in incidence, prevalence, mortality, and comorbidity of the rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:229. doi: 10.1186/ar2669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacGregor AJ, Snieder H, Rigby AS, Koskenvuo M, Kaprio J, Aho K, et al. Characterizing the quantitative genetic contribution to rheumatoid arthritis using data from twins. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:30–37. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200001)43:1<30::AID-ANR5>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okada Y, Wu D, Trynka G, Raj T, Terao C, Ikari K, et al. Genetics of rheumatoid arthritis contributes to biology and drug discovery. Nature. 2014;506:376–81. doi: 10.1038/nature12873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Källberg H, Ding B, Padyukov L, Bengtsson C, Rönnelid J, Klareskog L, et al. Smoking is a major preventable risk factor for rheumatoid arthritis: estimations of risks after various exposures to cigarette smoke. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:508–511. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.120899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robertson KD. DNA methylation and human disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:597–610. doi: 10.1038/nrg1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohkura N, Kitagawa Y, Sakaguchi S. Development and Maintenance of Regulatory T cells. Immunity. 2013;38:414–423. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Richardson B, Scheinbart L, Strahler J, Gross L, Hanash S, Johnson M. Evidence for impaired T cell DNA methylation in systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:1665–1673. doi: 10.1002/art.1780331109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takami N, Osawa K, Miura Y, Komai K, Taniguchi M, Shiraishi M, et al. Hypermethylated promoter region of DR3, the death receptor 3 gene, in rheumatoid arthritis synovial cells. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:779–787. doi: 10.1002/art.21637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nile CJ, Read RC, Akil M, Duff GW, Wilson AG. Methylation status of a single CpG site in the IL6 promoter is related to IL6 messenger RNA levels and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2686–2693. doi: 10.1002/art.23758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu C, Fang T, Ou T, Wu C, Li R, Lin Y, et al. Global DNA methylation, DNMT1, and MBD2 in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Immunol Lett. 2011;135:96–99. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glossop JR, Emes RD, Nixon NB, Packham JC, Fryer AA, Mattey DL, et al. Genome-wide profiling in treatment-naive early rheumatoid arthritis reveals DNA methylome changes in T- and B-lymphocytes. Epigenomics. 2015 doi: 10.2217/epi.15.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glossop JR, Haworth KE, Emes RD, Nixon NB, Packham JC, Dawes PT, et al. DNA methylation profiling of synovial fluid FLS in rheumatoid arthritis reveals changes common with tissue-derived FLS. 2015;7:539–551. doi: 10.2217/epi.15.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whitaker JW, Shoemaker R, Boyle DL, Hillman J, Anderson D, Wang W, et al. An imprinted rheumatoid arthritis methylome signature reflects pathogenic phenotype. Genome Med. 2013;5:40. doi: 10.1186/gm444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bartok B, Firestein GS. Fibroblast-like synoviocytes: Key effector cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Immunol Rev. 2010;233:233–255. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00859.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:315–324. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barton JL, Trupin L, Schillinger D, Gansky SA, Tonner C, Margaretten M, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in disease activity and function among persons with rheumatoid arthritis from university-affiliated clinics. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63:1238–1246. doi: 10.1002/acr.20525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MAR, Bender D, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patterson N, Price AL, Reich D. Population structure and eigenanalysis. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:2074–2093. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Consortium TIH. The International HapMap Project. Nature. 2003;426:789–796. doi: 10.1038/nature02168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis S, Du P, Bilke S, Jr, Triche T, Bootwalla M. methylumi: Handle Illumina methylation data. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yousefi P, Huen K, Schall RA, Decker A, Elboudwarej E, Quach H, et al. Considerations for normalization of DNA methylation data by Illumina 450K BeadChip assay in population studies. Epigenetics. 2013;8:1141–1152. doi: 10.4161/epi.26037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teschendorff AE, Marabita F, Lechner M, Bartlett T, Tegner J, Gomez-Cabrero D, et al. A beta-mixture quantile normalization method for correcting probe design bias in Illumina Infinium 450 k DNA methylation data. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:189–196. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen YA, Lemire M, Choufani S, Butcher DT, Grafodatskaya D, Zanke BW, et al. Discovery of cross-reactive probes and polymorphic CpGs in the Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 microarray. Epigenetics. 2013;8:203–209. doi: 10.4161/epi.23470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B. 1995;57:289– 300. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rahmani E, Zaitlen N, Baran Y, Eng C, Hu D, Galanter J, et al. Sparse PCA corrects for cell type heterogeneity in epigenome-wide association studies. Nat Methods. 2016;13:443–445. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu Y, Aryee MJ, Padyukov L, Fallin MD, Hesselberg E, Runarsson A, et al. Epigenome-wide association data implicate DNA methylation as an intermediary of genetic risk in rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:142–7. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Devlin B, Roeder K, Wasserman L. Genomic control, a new approach to genetic-based association studies. Theor Popul Biol. 2001;60:155–66. doi: 10.1006/tpbi.2001.1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zou J, Lippert C, Heckerman D, Aryee M, Listgarten J. Epigenome-wide association studies without the need for cell-type composition. Nat Methods. 2014;11:309–11. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eyre S, Bowes J, Diogo D, Lee A, Barton A, Martin P, et al. High-density genetic mapping identifies new susceptibility loci for rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1336–40. doi: 10.1038/ng.2462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yarwood A, Han B, Raychaudhuri S, Bowes J, Lunt M, Pappas Da, et al. A weighted genetic risk score using all known susceptibility variants to estimate rheumatoid arthritis risk. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013:1–7. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gregersen PK, Silver J, Winchester RJ. The shared epitope hypothesis. An approach to understanding the molecular genetics of susceptibility to rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1987;30:1205–1213. doi: 10.1002/art.1780301102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holoshitz J. The rheumatoid arthritis HLA-DRB1 shared epitope. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2010;22:293–298. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e328336ba63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raychaudhuri S, Sandor C, Stahl EA, Freudenberg J, Lee H-S, Jia X, et al. Five amino acids in three HLA proteins explain most of the association between MHC and seropositive rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Genet. 2012;44:291–296. doi: 10.1038/ng.1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robin X, Turck N, Hainard A, Tiberti N, Lisacek F, Sanchez J-C, et al. pROC: an open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:77. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Helm-Van Mil a, Van Der HM, Verpoort KN, Breedveld FC, Huizinga TWJ, Toes REM, De Vries RRP. The HLA-DRB1 shared epitope alleles are primarily a risk factor for anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies and are not an independent risk factor for development of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:1117–1121. doi: 10.1002/art.21739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stefansson OA, Moran S, Gomez A, Sayols S, Arribas-Jorba C, Sandoval J, et al. A DNA methylation-based definition of biologically distinct breast cancer subtypes. Mol Oncol. 2015;9:555–568. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2014.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsai PC, Bell JT. Power and sample size estimation for epigenome-wide association scans to detect differential DNA methylation. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44:1429–1441. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Georgiadis P, Hebels DG, Valavanis I, Liampa I, Bergdahl IA, Johansson A, et al. Omics for prediction of environmental health effects: Blood leukocyte-based cross-omic profiling reliably predicts diseases associated with tobacco smoking. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20544. doi: 10.1038/srep20544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parkes M, Cortes A, van Heel Da, Brown Ma. Genetic insights into common pathways and complex relationships among immune-mediated diseases. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14:661–73. doi: 10.1038/nrg3502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cope AP, Schulze-Koops H, Aringer M. The central role of T cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007;25:S4–S11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fujii H, Shao L, Colmegna I, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. Telomerase insufficiency in rheumatoid arthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:4360–4365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811332106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. Rheumatoid arthritis. Immunol Rev. 2005;204:55–73. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shao L, Fujii H, Colmegna I, Oishi H, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. Deficiency of the DNA repair enzyme ATM in rheumatoid arthritis. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1435–1449. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang Z, Fujii H, Mohan SV, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM. Phosphofructokinase deficiency impairs ATP generation, autophagy, and redox balance in rheumatoid arthritis T cells. J Exp Med. 2013;210:2119–34. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reinius LE, Acevedo N, Joerink M, Pershagen G, Dahlén SE, Greco D, et al. Differential DNA methylation in purified human blood cells: Implications for cell lineage and studies on disease susceptibility. PLoS One. 2012:7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Plant D, Wilson AG, Barton A. Genetic and epigenetic predictors of responsiveness to treatment in RA. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014;10:329–37. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2014.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim Y, Logan JW, Mason JB, Roubenoff R. DNA hypomethylation in inflammatory arthritis: Reversal with methotrexate. 1996:165–172. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2143(96)90008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bibikova M, Barnes B, Tsan C, Ho V, Klotzle B, Le JM, et al. High density DNA methylation array with single CpG site resolution. Genomics. 2011;98:288–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Illumina. Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip Kit. 2015. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. FLS Candidate Sites Replicated in CD4 Naïve Cells in Peripheral Blood of RA Cases.

Table S3. Candidate CpGs from Genes Previously Associated with RA.

Supplementary Text 1: Results of Overnight Cell Storage

Figure S1. Eigenvector 1 and 2 from EIGENSTRAT in all samples.

Figure S2. Eigenvector 2 and 3 from EIGENSTRAT in all samples.

Figure S3. Eigenvector 1 and 2 from EIGENSTRAT in European ancestry samples.

Figure S4. MDS of CD4+ naïve T cells before normalization.

Figure S5. MDS of CD4+ naïve T cells after normalization.

Table S2. Logistic Regression Results from Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test FLS Sites

Table S4. Candidate GWAS CpG Results

Table S5. Logistic Regression Results Using 18 Significant CpGs from Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test, GWA Sites

Table S6. Genome-wide Results.

Table S7. Mean Methylation in RA Cases and Controls.