Abstract

BACKGROUND

Chronic inflammation and oxidative stress are hallmarks of chagasic cardiomyopathy (CCM). In this study, we determined if microparticles (MPs) generated during Trypanosoma cruzi (Tc) infection carry the host’s signature of inflammatory/oxidative state and provide information regarding the progression of clinical disease.

METHDOS

The MPs were harvested from supernatants of human PBMCs in vitro incubated with T. cruzi (control: LPS-treated), plasma of seropositive humans with clinically asymptomatic (CA) or symptomatic (CS) disease state (normal/healthy (NH) controls) and plasma of mice immunized with a protective vaccine before challenge infection (control: unvaccinated/infected). Macrophages (mφs) were incubated with MPs, and we probed the gene expression profile using the inflammatory signaling cascade and cytokine/chemokine arrays, phenotypic markers of macrophage activation by flow cytometry, cytokine profile by an ELISA and Bioplex assay, and oxidative/nitrosative stress and mitotoxicity by colorimetric and fluorometric assays.

RESULTS

Tc- and LPS-induced MPs stimulated proliferation, inflammatory gene expression profile and •NO release in human THP-1 mφs. LPS-MPs were more immunostimulatory than Tc-MPs. Endothelial cells, T lymphocytes and mφs were the major source of MPs shed in plasma of chagasic humans and experimentally infected mice. The CS-MPs and CA-MPs (vs. NH-MPs) elicited >2-fold increase in •NO and mitochondrial oxidative stress in THP-1 mφs; however, CS-MPs (vs. CA-MPs) elicited a more pronounced and disease-state-specific inflammatory gene expression profile (IKBKB, NR3C1, and TIRAP vs. CCR4, EGR2 and CCL3), cytokine release (IL2+IFNγ>GCSF), and surface markers of mφ activation (CD14 and CD16). The circulatory MPs of non-vaccinated/infected mice induced 7.5-fold and 40% increase in •NO and IFNγ production, respectively, while these responses were abolished when RAW264.7 mφs were incubated with circulatory MPs of vaccinated/infected mice.

CONCLUSION

Circulating MPs reflect in vivo levels of oxidative, nitrosative, and inflammatory state and have potential utility in evaluating disease severity and efficacy of vaccines and drug therapies against CCM.

Keywords: Chagasic cardiomyopathy, microparticles, metabolic and inflammatory gene expression profile, macrophage activation

INTRODUCTION

Trypanosoma cruzi (T. cruzi or Tc) is endemic in Latin America and is an emerging infection in the United States [1]. The prevalence of human Tc infection is at ~20-million, and 120 million are at risk of infection in Latin America [1]. Vectors carrying T. cruzi are wide-spread in the US, and CDC estimates that >300,000 infected individuals are living in the US [2]. Unfortunately, exposure to Tc remain undetected until several years later when patients display cardiac insufficiency due to tissue fibrosis, ventricular dilation, and arrhythmia [3]. Chagasic cardiomyopathy (CCM) results in a loss of 2.74 million disability-adjusted life years, and >15,000 deaths due to heart failure per year [1].

Macrophages (Mφs) are the immune cells that are essential for controlling T. cruzi infection [4, 5]. It is suggested that mφ-derived peroxynitrite, a strong cytotoxic agent that is formed by the reaction of nitric oxide (•NO) with superoxide (O2•−), plays a major role in direct killing of T. cruzi [6]. Infected experimental animals and humans also elicit strong adaptive immunity constituted of anti-parasite lytic antibodies, type 1 cytokines, and antigen specific cytolytic T lymphocytes (reviewed in [7]). These immune responses are capable of keeping the parasite burden in control but lack the ability to achieve pathogen clearance [8], leading to low level parasite persistence.

In recent years, we and others have shown that Tc invasion elicits functional changes in mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes, and this initial insult continues and serves as a major source of increased production of O2•− radicals in the heart [9]. Control of Tc-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) by using chemical antioxidants or by genetically enhancing the expression of superoxide dismutase (SOD2) resulted in an improvement in cardiac mitochondrial respiratory chain function in chagasic mice [10, 11]. Importantly, SOD2 over-expressing mice also exhibited a lower degree of inflammatory infiltrates and mitochondrial damage that otherwise was pronounced in chagasic myocardium [12]. These studies suggested that Tc-induced ROS are not only associated with chronic oxidative stress but may also signal the activation and recruitment of inflammatory infiltrate in the chagasic heart.

The role of ROS in signaling inflammatory immune responses in Chagas disease is not completely understood. Extensive infiltration of gp91phox+ (NOX2 component) mφ clusters associated with oxidative adducts is noted in chagasic heart [13, 14]. Macrophages in vitro incubated with heart homogenates or plasma of infected mice elicited proinflammatory response evidenced by increased production of ROS, •NO and TNF-α [15]. Heart homogenates of chagasic mice or of normal mouse in vitro oxidized with H2O2 or peroxynitrite were recognized by antibodies present in the sera of Tc-infected host [15]. These studies suggest that oxidative stress induced adducts are potentially responsible for chronic activation of inflammatory macrophages and non-Tc-specific antibody response in Chagas disease. The practical and ethical limitations in obtaining cardiac biopsies; however, prohibit using ROS production and ROS-induced antigen generation and mφ activation as early indicators for identifying patients at risk of developing clinically symptomatic CCM.

Microparticles (MPs) are small vesicles harboring ligands, receptors, active lipids or RNA/DNA from the cell of their origin [16]. In pathological conditions, a stimulus that triggers MP formation regulates the selective sorting of constituents and composition of MPs, and, consequently, the biological information that they transfer [17]. Thus, MPs can play roles in intercellular communication and be able to modulate important cellular regulatory functions. There is no literature or information in the public domain on the potential effects of MPs on the molecular mechanisms implicated in the pathophysiology of CCM.

In this study, we aimed to determine whether circulating MPs generated during Tc infection carry the host’s signature of inflammatory/oxidative pathology and provide information regarding the clinical disease severity. We isolated MPs released in the i) supernatants of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells in vitro infected with Tc and ii) plasma of human subjects who were characterized as seropositive with clinically asymptomatic (CA) or symptomatic (CS) Chagas disease; and employed high throughput transcriptomic and physiological approaches to study the mφ response to MPs. We also used MPs from a mouse model of vaccination and chronic disease to determine if mφ response to circulating MPs provides an indication of cure from infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement

All animal experiments were performed according to the National Institutes of Health Guide for Care and Use of Experimental Animals, and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston (protocol number: 0805029).

The collection of human peripheral blood samples was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston (protocol number: IRB13-0367) and the ethics committee at the Universidad Nacional de Salta in Salta, Argentina. A written informed consent was obtained from all individuals visiting the Cardiologic Unit of San Bernardo Hospital in Salta Argentina for clinical service. The leftover blood samples collected for clinical purpose were decoded and de-identified before they were provided for research purposes.

Human samples

The T. cruzi-specific antibodies were analyzed in all sera samples by using the Chagatest ELISA recombinant (v.4.0) and Chagatest HAI kits (Wiener, Rosario, Argentina). Sera samples were considered seropositive if both tests identified the presence of anti-Tc antibodies. Electrocardiography (ECG, 12-lead at rest and 3-lead with exercise) and transthoracic echocardiography were performed for evaluating the heart function in all individuals. Normal healthy (NH, n=10) controls were seronegative and exhibited no history or clinical symptoms of heart disease. Seropositive individuals were grouped as clinically asymptomatic (CA, n=10) when they exhibited none to minor ECG abnormalities, no left ventricular dilatations, and normal ejection fraction (EF) of 55–70%. Seropositive individuals were categorized as clinically symptomatic (CS, n=10) when they displayed varying degree of ECG abnormalities, systolic dysfunction (EF: <55%), left ventricular dilatation (diastolic diameter ≥57 mm), and/or potential signs of HF [18].

Mice, immunization, and challenge infection

All chemicals used in the study were of molecular grade, and purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise specified. C57BL/6 female mice (wildtype) were purchased from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN). T. cruzi (SylvioX10/4) and C2C12 cells (an immortalized, mouse-derived myoblast cell line) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas VA) and T. cruzi trypomastigotes (infective stage) were propagated in C2C12 cells. T. cruzi antigens TcG2 and TcG4 were used as vaccine candidates and have been described in detail previously [19, 20]. Mice (n = five per group per experiment, two experiments) were injected in the quadriceps muscle with TcG2 and TcG4 antigens that were delivered as DNA-prime/protein-boost vaccine [19, 20]. Two weeks after immunization, mice were challenged with T. cruzi trypomastigotes (10,000/mouse), and sacrificed at ~120 days post-infection (pi), corresponding to the chronic disease phase [19, 20]. Plasma samples were subjected to isolation of circulating microparticles as is described below. Protein levels were determined by using the Bradford Protein Assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules CA).

Microparticles (MPs) isolation

Human blood samples were drawn in EDTA-containing Vacutainer CPT Cell Preparation Tubes (BD Biosciences, San Jose CA). The tubes were centrifuged for 20 min each at 270 g and 1000 g to separate plasma. Plasma samples were subjected to three series of centrifugation at 15,000 g for 15 min each and pelleted MPs were washed with RPMI media and stored at −80°C. A similar protocol was followed for isolating the MPs from murine plasma samples.

In some experiments, buffy coat obtained after separation of plasma were subjected to Fi-coll Hypaque™ density gradient (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh PA), and centrifuged at 400 g for 30 minutes. The enriched human PBMC pellets were washed with RPMI media, seeded in 24 well plates (0.5–1×106 cells/well/ml), and incubated in triplicate with T. cruzi (cell to parasite ratio, 1:3) or LPS (100 ng/ml) in RPMI media /10% FBS media at 37°C/5% CO2 for 48 h. MPs from the supernatants were collected as above.

Treatment of macrophages with microparticles

THP-1 human monocytes (ATCC TIB-202) were suspended in complete RPMI media and incubated at 37°C/5% CO2 for 24 h in presence of 50 ng/ml phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA, Sigma-Aldrich), and then for 48 h in complete RPMI media without any stimulus to generate the resting mφs [21]. RAW 264.7 murine macrophages (ATCC TIB-71) were cultured in high glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 2 mmol/l glutamine, 100 IU/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Corning, Corning NY). THP-1 (human) or RAW 264.7 (murine) mφs were seeded in 6-well (1×106 cells/well), 24-well (5×105 cells/well) or 96-well (1×104 cells/well) plates, or in Nunc Lab-Tek II chamber slides (1×104 cells/well, Thermo Scientific, Waltham MA) and incubated for 2 h to allow the cells to adhere. Serum-free media was added, and macrophages were incubated in triplicate with microparticles (MPs) isolated from human or mouse plasma (10% plasma equivalent) or from media of Tc-infected cells (10% media equivalent). Macrophages (± MPs) were incubated for 1, 12, 24 or 48 h and cells and supernatants were stored at −80°C.

Gene expression profiling by real-time reverse transcriptase-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

The quantitative expression profiling of a panel of 91 human genes involved in the inflammatory signaling cascade was performed by using custom-designed arrays printed by Sigma Aldrich. Full details of the arrays were previously described [22]. Gene expression profiling for human cytokines/chemokines was performed by using an in-house PCR array that consisted of 89 genes [23]. All primer sequences are available upon request.

THP-1 mφs were seeded in 12-well plates (1×106 cells/well) and incubated in triplicate with MPs for 12 h. Cells were suspended in TRIzol reagent, and total RNA was extracted and precipitated by chloroform/isopropanol/ethanol method. The DNA that might be contaminating the RNA preparation was removed by deoxyribonuclease I (DNase I) treatment (Ambion, Austin, TX). Total RNA absorbance at 260 nm and 280 nm was read by using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Wilmington, DE) to assess the quality (OD260/280 ratio > 2.0) and quantity (OD260 of 1 = 40 μg/ml RNA). First strand cDNA was synthesized from DNaseI-treated 1 μg of RNA sample using the iScript™ cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad) and diluted 5-fold with nuclease free ddH2O. Quantitative real time PCR was performed in a 20 μl reaction containing 1 μl cDNA, 10 μl SYBR green master mix (Bio-rad), and 500 nM of each gene-specific oligonucleotides. The thermal cycle conditions were 94°C for 30 sec followed by 60°C for 1 min, for 40 cycles. The PCR Base Line Subtracted Curve Fit mode was applied for determining the threshold cycle, Ct, using iCycler iQ Real-Time Detection System Software (Bio-Rad). For each target gene, Ct values were normalized to the Ct values for beta actin (ACTB), and beta glucuronidase (GUSB) reference genes. The relative expression level of each target gene was calculated following 2−ΔΔCt method, where ΔCt represents the Ct (target) - Ct (reference), and ΔΔCt represents ΔCt (sample) – ΔCt (no treatment control or control MP treatment) [21].

Cell viability

THP-1 macrophages were seeded to 96-well plates (1×104 cells/200 μl/well), and incubated in triplicate with serum-free media (± MPs) for 24 h. Cells were loaded with 10% (v/v) alamarBlue (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) during the last 3 h of incubation. Alamar blue metabolism by functional mitochondria, resulting in cleavage of resazurin into fluorescent resorufin (Ex560nm/Em590nm) was recorded by using a SpectraMax M5 spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

ROS and nitric oxide (•NO) levels

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) were monitored by using 2′, 7′ dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) fluorescent probe. Briefly, THP-1 mφs were seeded in 96 well plates (1×104 cells per well), allowed to adhere for 2 h, and then incubated for 1 h in triplicate with MPs. Supernatants were harvested, and cells were washed and loaded with 10 μM of H2DCFDA in 100 μl of serum-free media, and incubated in dark for 30 min at 37°C. Cells were washed three times with phenol red-free media and H2DCFDA oxidation by intracellular ROS resulting in the formation of fluorescent dichlorodihydrofluorescein (DCF, Ex498nm/Em598nm) was recorded by fluorimetry. Cells treated with 0.1–1 μM H2O2 were used as positive control.

The nitric oxide level (an indicator of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) activity) was monitored by Griess reagent assay. Briefly, samples were reduced with 0.01 unit/100 μl of nitrate reductase, and incubated for 10 min with 100 μl of 1% sulfanilamide made in 5% phosphoric acid/0.1% N-(1-napthyl) ethylenediamine dihydrochloride (1:1, v/v). Formation of diazonium salt was monitored at 545 nm by spectrophotometry (standard curve: 2–50 μM sodium nitrite) [24].

Mitochondrial membrane potential and ROS

To examine the changes in mitochondrial membrane potential, mφs were seeded and MPs added in triplicate. Mφs were incubated for 24 h with MPs, washed, and then with 10 μM 5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolyl-carbocyanine iodide (JC-1, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 30 min. Cells were washed twice with cold PBS to remove the excess dye, suspended in serum-free/ phenol red-free RPMI, and fluorescence was measured as above. JC-1 dye in respiring mitochondria is converted from green (Ex485nm/Em530nm) to red (Ex530nm/Em580nm) fluorescent J-aggregates and provides a sensitive indication of the changes in mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm).

To measure mitochondrial ROS production, mφs (± MPs) were incubated in dark for 30 min with 5 μM MitoSOX Red (Invitrogen). MitoSOX Red oxidation by mitochondrial ROS, resulting in red fluorescence (Ex518nm/Em605nm), was detected by fluorimetry.

Cytokine levels

A Bio-Plex Pro Human Cytokine 17-Plex Assay (Bio-Rad M5000031YV) was employed to profile the concentration of human cytokines and chemokines. Briefly, THP-1 mφs were seeded in 48-well plates in 500 μl media and MPs were added in triplicate. After incubation for 24 h, culture supernatants (50 μl) were transferred in duplicate to the plates pre-coated with cytokine-specific antibodies conjugated with different color-coded beads, and plates were incubated for 1 h. Plates were washed and then sequentially incubated with 50-μl of biotinylated cytokine-specific detection antibodies and streptavidin–phycoerythrin conjugate. Fluorescence was recorded using a SpectraMax M5 microplate reader, and cytokine/chemokine concentrations were calculated with a Bio-Plex Manager software (v.5) by using a standard curve derived from recombinant cytokines (2–32,000 pg/ml).

In some experiments, THP-1 mφs seeded in 24 well plates (5×105 cells/well/ml) were incubated in triplicate with human MPs for 48 h. Culture supernatants were utilized for the measurement of cytokine release (IL-1β, IL-4, IL-10, IFN-γ, and TNF-α) using human cytokine optEIA™ ELISA kits (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). Likewise, supernatants from RAW 264.7 mφs incubated for 48 h with MPs isolated from normal, chagasic and vaccinated/chagasic mice were analyzed for IL-1β, IL-4, IL-10, IFN-γ, and TNF-α levels by using murine cytokine optEIA™ ELISA kits (Pharmingen).

Flow cytometry

To evaluate the changes in expression of surface markers in response to MPs, THP-1 mφs were seeded in 6 well plates (1×106 cells/well/ml), and incubated in triplicate with MPs (10% serum equivalent) for 24 h. Cells were harvested, pelleted and suspended in 50 μl of stain buffer (PBS with 2% FBS). Suspended cells were stained for 30 minutes with antibody cocktails containing human peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP)-anti-CD14, allophycocyanin (APC-Cy7)-anti-CD16, APC-anti-CD206, phycoerythrin (PE-Cy7)-anti-CD64, PE-Cy5-anti-CD80, and V-450-anti-CD200 fluorescence-conjugated antibodies (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes NJ). We washed the stained cells, fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde, and then analyzed by six-color flow cytometry on an LSRII Fortessa Cell Analyzer. Cells stained with isotype-matched IgGs were used as controls. Macrophages were gated based on parameters of forward and side light scatter and data acquisition was performed on a minimum of 10,000-gated events. Data were analyzed using Flow Jo software (v.7.6.5, TreeStar, San Carlo, CA). The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was derived from fluorescence histograms, and was adjusted for background with isotype-matched control.

To evaluate the cellular origin of MPs, MPs were isolated from media of human PBMCs in vitro infected with Tc and plasma of clinically characterized human subjects as described above. The MPs were also isolated from plasma of normal and experimentally infected mice. The MP’s were re-suspended in Annexin V binding buffer and labeled for 30 min on ice with APC- or FITC-conjugated anti-Annexin V antibody. Simultaneously, MPs were labeled with mouse or human PerCP-anti-CD14, APC-Cy7-anti-CD61, PE-Cy7-anti-CD62E, V-450-anti-troponin, FITC-anti-CD4 and PE-anti-CD8 fluorescence-conjugated antibodies (5–10μl/sample, e-Biosciences). Stained MPs were washed with cold PBS and flow cytometry was performed on an LSRII Fortessa Cell Analyzer. In order to separate true events from background noise and unspecific binding of antibodies to debris, we defined microparticles as particles that were less than1-μm in diameter and had positive staining for Annexin V.

Statistical analysis

All in vitro and in vivo experiments were repeated at least twice, and conducted with triplicate observations per sample and data are expressed as mean ± SEM. All data were analyzed using InStat version 3 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). Data were analyzed by the Student’s t-test (for comparison of two groups) and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s post hoc test (for comparison of multiple groups). Significance is presented as *p<0.05, **p<0.01, and ***p<0.001.

RESULTS

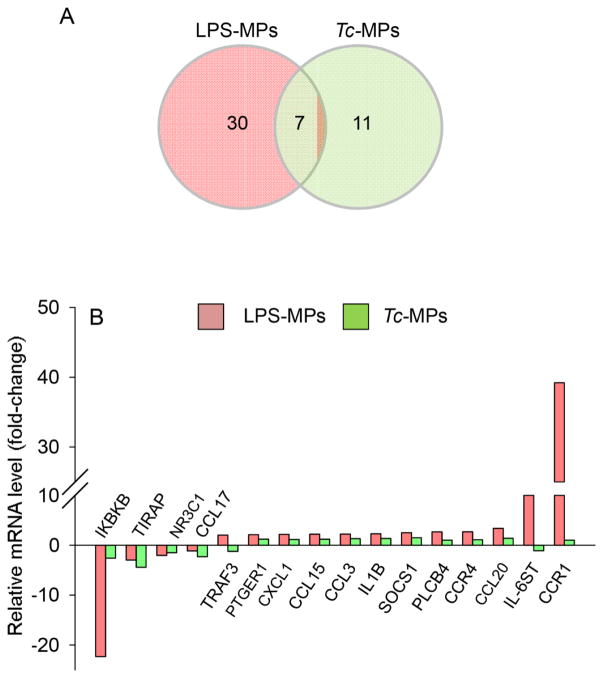

We first utilized an in vitro system to determine if Tc infection produces microparticles capable of activating macrophages. For this, human PBMCs were incubated for 48 h with T. cruzi and supernatants were centrifuged to harvest the Tc-induced MPs (Tc-MPs). PBMCs were also incubated with LPS or media alone for 48 h, and supernatants were centrifuged to harvest the LPS-induced (LPS-MPs) and no-treatment/control (Con-MPs) microparticles, respectively. We incubated THP-1 mφs for 12 h with MPs, and first performed qRT-PCR analysis using the inflammatory signaling cascade and cytokine/chemokine arrays to probe the expression of 180 genes (including the housekeeping genes). The data were normalized to housekeeping genes, and the relative change in gene expression in THP-1 mφs incubated with sample MPs (vs. Con-MPs) calculated. These data showed 37 genes (30 up regulated, 7 down regulated) and 18 genes (5 up regulated, 13 down regulated) were differentially expressed (≥ |1.5| fold change, p<0.05) in THP-1 mφs incubated with LPS-MPs and Tc-MPs, respectively, when compared to that noted in mφs incubated with Con-MPs (Table 1). Of these, 7 genes were differentially expressed (↓TIRAP, ↓IKBKB, ↓C3, ↓NR3C1, ↑SOCS1, ↑CXCL5, ↑IL10) by both LPS- and Tc-induced MPs, and 11 genes (↓CCL17, ↓TP53, ↓IL6, ↓EGR2, ↓NR2C2, ↓EGFR, ↓PTGER2, ↓TNFSF18, ↓INSR, ↑IL4, ↑IL2RA) were differentially expressed in mφs in a Tc-MPs-specific manner (Fig. 1A, Table 1). Top molecules that were differentially expressed by >2-fold in THP-1 mφs by LPS- and Tc-induced MPs in comparison to Con-MPs are shown in Fig. 1B.

Table 1.

Expression profiling of inflammation-related genes by qRT-PCR

| Gene Symbol | Gene name | 1 Fold Change | 2 Fold Change | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| LPS.MP | Tc.MP | CA.MP | CS.MP | ||

| Inflammation signaling cascade arrays | |||||

|

| |||||

| AKT1 | v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene 1 | −1.1 | −1.3 | −1.1 | −1.5 |

| C3 | complement component 3 | −1.5 | −1.9 | −1.2 | −4.7 |

| CCL15 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 15 | 2.2 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.6 |

| CCL16 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 16 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.9 |

| CCL17 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 17 | −1.1 | −2.3 | 2.1 | 1.2 |

| CCL20 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 20 | 3.4 | 1.4 | 3.2 | 3.6 |

| CCL25 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 25 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.9 |

| CCR1 | chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 1 | 39.2 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.8 |

| CCR4 | chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 4 | 2.7 | 1.1 | 8.8 | 1.8 |

| CCR5 | chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 5 | −1.3 | −1.3 | 1.1 | −1.2 |

| CCR6 | chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 6 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.9 |

| CCR8 | chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 8 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.9 |

| CD14 | CD14 molecule | 1.3 | −1.2 | −1.2 | −1.7 |

| CD40 | CD40 molecule | 1.4 | −1.0 | 1.0 | −1.2 |

| CD83 | CD83 molecule | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.9 |

| CLEC7A | C-type lectin domain family 7A | 1.1 | −1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| CREB1 | cAMP responsive element binding 1 | −1.1 | −1.0 | 1.1 | 1.9 |

| CRP | C-reactive protein, pentraxin-related | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.9 |

| CYSLTR1 | cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1 | −1.2 | −1.1 | 1.1 | −1.0 |

| HRH3 | histamine receptor H3 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.9 |

| ICAM1 | intercellular adhesion molecule 1 | 1.3 | −1.3 | 1.0 | −1.4 |

| IFNG | interferon gamma | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.9 |

| IKBKB | inhibitor of kappa light chain enhancer kinase β | −22.3 | −2.6 | 1.1 | 6.7 |

| IL10 | interleukin 10 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.9 |

| IL12B | interleukin 12b | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.9 |

| IL17A | interleukin 17A | 1.5 | −1.2 | −1.5 | 1.9 |

| IL1B | interleukin 1, beta | 2.3 | 1.3 | 1.8 | −1.0 |

| IL1R1 | interleukin 1 receptor, type I | 1.7 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| IL1RN | interleukin 1 receptor antagonist | 1.2 | −1.1 | 2.5 | −1.6 |

| IL2 | interleukin 2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.9 |

| IL23 | interleukin 23 | 1.3 | −1.2 | 1.0 | 1.3 |

| IL2RA | interleukin 2 receptor, alpha | −1.1 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.3 |

| IL4 | interleukin 4 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| IL6 | interleukin 6 | 1.4 | −1.8 | 1.1 | 1.9 |

| IL6R | interleukin 6 receptor | −1.4 | −1.2 | −1.2 | −1.1 |

| IL6ST | interleukin 6 signal transducer | 14.6 | −1.1 | 2.1 | 1.0 |

| IL8 | interleukin 8 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 2.0 | 1.9 |

| INSR | insulin receptor | 1.9 | −1.5 | −1.3 | 1.1 |

| JAK2 | Janus kinase 2 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.3 |

| LTA | lymphotoxin alpha | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.5 |

| LTB4R2 | leukotriene B4 receptor 2 | 1.1 | 1.0 | −1.5 | −2.4 |

| LTC4S | leukotriene C4 synthase | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 3.7 |

| MALT1 | mucosa assoc lymphoid translocation gene 1 | 1.3 | 1.0 | −1.3 | 1.2 |

| MAP3K1 | mitogen-activated protein 3 kinase 1 | 1.1 | 1.0 | −1.0 | −1.2 |

| MAPK1 | mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| MAPK8 | mitogen-activated protein kinase 8 | −1.0 | −1.4 | −1.1 | −1.0 |

| MMP1 | matrix metallopeptidase 1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.2 | 3.2 |

| MMP13 | matrix metallopeptidase 13 | 1.2 | 1.0 | −2.0 | −1.2 |

| MMP9 | matrix metallopeptidase 9 | 1.2 | −1.0 | −1.3 | −1.6 |

| MTHFR | methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.9 |

| MYD88 | myeloid differentiation gene 88 | 1.1 | −1.3 | −1.4 | −1.2 |

| NFKB1 | nuclear factor kappa light chain enhancer 1 | 1.7 | 1.3 | −2.6 | −1.2 |

| NFKB1A | nuclear factor kappa B 1 A | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.0 | −1.2 |

| NFKB2 | nuclear factor kappa light chain enhancer 2 | 1.4 | −1.0 | −1.1 | −1.2 |

| NOS2 | nitric oxide synthase 2, inducible | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.9 |

| NR2C2 | nuclear receptor subfamily 2, group C, 2 | −1.0 | −1.6 | −1.2 | −1.3 |

| NR3C1 | nuclear receptor subfamily 3, group C, 1 | −2.0 | −1.5 | 1.4 | 20.0 |

| NR4A1 | nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, 1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 2.8 | 1.9 |

| NR4A2 | nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, 2 | 1.8 | 1.0 | 1.3 | −1.7 |

| PLA2G2D | phospholipase A2, group IID | 1.2 | −1.2 | 1.0 | 2.3 |

| PPARG | peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ | −1.0 | −1.4 | 2.3 | 2.6 |

| PTGER1 | prostaglandin E receptor 1 | 2.1 | 1.2 | −1.2 | 1.1 |

| PTGER2 | prostaglandin E receptor 2 | −1.1 | −1.5 | −1.4 | −1.5 |

| PTGS2 | prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 | 1.3 | 1.0 | −1.3 | −1.4 |

| REL | v-rel reticuloendotheliosis viral oncogene | 1.1 | −1.4 | −1.1 | −1.0 |

| RELA | v-rel reticuloendotheliosis viral oncogene A | −1.1 | −1.3 | −1.3 | −1.3 |

| RIPK1 | receptor-interacting serine-threonine kinase 1 | 1.1 | −1.2 | 1.1 | −1.2 |

| SELE | selectin E | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.9 |

| SOCS1 | suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.8 |

| SOCS3 | suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 | 1.3 | 1.2 | −1.1 | 1.3 |

| SOX9 | sex determining region Y-box 9 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.9 |

| STAT3 | signal transducer, activator of transcription 3 | 1.2 | −1.2 | 1.1 | −1.2 |

| TGFB1 | transforming growth factor, beta 1 | 1.1 | −1.3 | −1.3 | −1.3 |

| TLR1 | toll-like receptor 1 | −1.0 | −1.1 | 1.2 | 1.1 |

| TLR2 | toll-like receptor 2 | 1.1 | −1.2 | −1.2 | −1.1 |

| TLR3 | toll-like receptor 3 | −1.0 | −1.2 | 1.1 | 1.9 |

| TLR4 | toll-like receptor 4 | −1.1 | −1.3 | −1.5 | −1.8 |

| TLR6 | toll-like receptor 6 | 1.0 | −1.2 | 1.4 | 1.2 |

| TLR7 | toll-like receptor 7 | −1.1 | −1.2 | 1.0 | −1.5 |

| TLR8 | toll-like receptor 8 | 1.1 | −1.1 | 1.1 | −1.2 |

| TNFA | tumor necrosis factor alpha | 1.6 | 1.1 | −1.3 | −1.5 |

| TNFRSF10B | tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily10B | 1.2 | −1.1 | −1.0 | −1.1 |

| TNFRSF1A | tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily 1A | 1.1 | −1.1 | −1.4 | −1.4 |

| TNFSF18 | tumor necrosis factor superfamily, member 18 | −1.1 | −1.5 | 2.7 | 1.9 |

| TP53 | tumor protein p53 | −1.2 | −1.9 | −1.4 | −1.1 |

| TRAF1 | TNF receptor-associated factor 1 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.0 | −1.2 |

| TRAF2 | TNF receptor-associated factor 2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | −1.5 | 1.2 |

| TRAF3 | TNF receptor-associated factor 3 | 2.0 | −1.2 | −1.4 | −1.1 |

| TRAF5 | TNF receptor-associated factor 5 | 1.7 | −1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| TRAF6 | TNF receptor-associated factor 6 | −1.2 | −1.2 | 1.2 | 1.1 |

| VCAM | vascular cell adhesion molecule | 1.4 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.9 |

|

| |||||

| Cytokines and chemokines arrays | |||||

|

| |||||

| ADRB2 | adrenoreceptor beta 2 | −1.5 | −1.1 | 1.5 | 1.0 |

| BCAM | basal cell adhesion molecule | −1.2 | −1.0 | 1.2 | 1.7 |

| BCL3 | B cell lymphoma 3 | 1.7 | −1.0 | −1.3 | −1.5 |

| BCL6 | B cell lymphoma 6 | −1.2 | −1.0 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| BCMA | B cell maturation antigen | −1.2 | −1.0 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| C5 | complement component 5 | −1.1 | −1.4 | −1.2 | −1.5 |

| CASP1 | caspase 1 | −1.2 | −1.0 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| CCL11 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 11 | −1.2 | −1.0 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| CCL13 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 13 | −1.2 | −1.0 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| CCL18 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 18 | 1.1 | −1.4 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| CCL19 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 19 | 1.4 | −1.2 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| CCL2 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 | 1.3 | 1.0 | −1.0 | 1.4 |

| CCL21 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 21 | −1.5 | −1.3 | 1.2 | −1.2 |

| CCL22 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 22 | −1.2 | −1.4 | −1.1 | −1.1 |

| CCL23 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 23 | 1.3 | −1.1 | −1.2 | 1.1 |

| CCL3 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 3 | 2.2 | 1.3 | 11.0 | 3.0 |

| CCL4 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 4 | −1.2 | −1.0 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| CCL5 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5 | 1.1 | −1.1 | 1.1 | −1.2 |

| CCL7 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 7 | −1.1 | −1.0 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| CCL8 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 8 | 1.8 | −1.2 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

| CCR10 | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 11 | −1.2 | −1.0 | 1.0 | 1.3 |

| CCR2 | chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 2 | 1.3 | 1.1 | −1.3 | −1.4 |

| CCR3 | chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 3 | −1.1 | −1.1 | 1.5 | 1.4 |

| CCR7 | chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 7 | 1.3 | −1.1 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| CCR9 | chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 9 | −1.1 | −1.4 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| CD4 | CD4 molecule | 1.0 | −1.3 | −1.4 | −1.6 |

| CD88 | CD88 molecule (C5a receptor) | 1.4 | −1.1 | −1.0 | −1.4 |

| CD8A | CD8A molecule | −1.5 | 1.3 | 3.0 | 2.5 |

| CD8B | CD8B molecule | −1.2 | −1.0 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| CREB1 | cAMP responsive element binding protein 1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| CSF1 | colony stimulating factor 1 | −1.2 | −1.4 | 2.0 | −1.0 |

| CSF1R | colony stimulating factor 1 receptor | −1.1 | −1.2 | 1.2 | −1.3 |

| CSF2 | colony stimulating factor 2 | −1.2 | −1.0 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| CTGF | connective tissue growth factor | −1.2 | −1.0 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| CXCL1 | chemokine (C-X-C Motif) ligand 1 | 2.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.3 |

| CXCL13 | chemokine (C-X-C Motif) ligand 13 | 1.6 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.8 |

| CXCL2 | chemokine (C-X-C Motif) ligand 2 | 1.8 | −1.1 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

| CXCL3 | chemokine (C-X-C Motif) ligand 3 | 1.6 | −1.0 | −1.3 | 2.0 |

| CXCL5 | chemokine (C-X-C Motif) ligand 5 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| EDN1 | endothelin 1 | 1.3 | −1.1 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| EGF | epidermal growth factor | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| EGFR | epidermal growth factor receptor | 1.1 | −1.5 | 1.2 | −1.2 |

| EGR2 | epidermal growth factor receptor 2 | −1.4 | −1.6 | 10.3 | 1.3 |

| F2 | coagulator factor II | −1.2 | −1.0 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| FOS | FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene | 1.2 | −1.0 | 1.1 | −1.2 |

| GSTP1 | glutathione S transferase Pi 1 | 1.1 | −1.0 | 1.1 | −1.1 |

| HIF1A | hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.1 |

| HLAA | histocompatibility complex class I A | −1.2 | −1.2 | 1.1 | 1.3 |

| HLAB | histocompatibility complex class I B | 1.4 | −1.0 | −1.2 | −1.2 |

| IGFBP1 | insulin growth factor binding protein 1 | −1.2 | −1.0 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| IGFBP2 | insulin growth factor binding protein 2 | 1.1 | −1.2 | −1.3 | −1.2 |

| IGFBP3 | insulin growth factor binding protein 3 | 1.4 | −1.0 | 5.5 | −1.2 |

| IL15 | interleukin 15 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| IL24 | interleukin 24 | −1.2 | −1.0 | 2.4 | 1.8 |

| IL5 | interleukin 5 | −1.2 | −1.0 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| IRAK1 | interleukin 1 receptor kinase 1 | 1.3 | 1.0 | −1.0 | −1.2 |

| IRAK2 | interleukin 1 receptor kinase 2 | 1.3 | −1.0 | 1.2 | −1.0 |

| IRF1 | interferon regulatory factor 1 | −1.0 | −1.3 | −1.2 | −1.4 |

| JUN | jun proto-oncogene | −1.1 | −1.2 | 1.3 | 1.2 |

| LCN2 | lipocalin 2 | −1.2 | −1.0 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| MMP2 | matrix metalloproteinase 2 | −1.0 | −1.2 | −1.6 | −1.6 |

| MMP3 | matrix metalloproteinase 3 | −1.2 | −1.0 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| MUC5AC | mucin 5AC | −1.2 | −1.0 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| NOD2 | nucleotide binding oligomerization domain 2 | −1.2 | −1.0 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| NR4A2 | nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, 2 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 1.1 |

| PAI1 | plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 | −1.2 | −1.0 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| PCK1 | phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1 | −1.2 | −1.0 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| PIM1 | proto-oncogene ser/thr protein kinase 1 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.1 | −1.1 |

| PIM2 | proto-oncogene ser/thr protein kinase 2 | 1.4 | −1.2 | −1.2 | −1.4 |

| PIM3 | proto-oncogene ser/thr protein kinase 3 | 1.5 | −1.1 | −1.6 | −1.2 |

| PLAT | plasminogen activator tissue | −1.2 | −1.0 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| PLCB4 | phospholipase C, beta 4 | 2.7 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| PSMD3 | proteosome 26S subunit | 1.2 | −1.2 | 1.0 | −1.0 |

| RARA | retinoic acid receptor alpha | 1.0 | −1.1 | −1.2 | −1.4 |

| RELB | v-rel reticuloendotheliosis viral oncogene B | 1.4 | −1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| RELMB | resistin like beta | −1.2 | −1.0 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| RETN | resistin | −1.2 | −1.0 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| SOD1 | superoxide dismutase 1 | −1.0 | −1.1 | 2.4 | 1.9 |

| SOD2 | superoxide dismutase 2 | 1.6 | −1.1 | 1.3 | 1.1 |

| STAT1 | signal transducer and activator of transcription | 1.1 | −1.2 | 1.4 | −1.0 |

| TBP | TATA box binding protein | −1.3 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| TGFB2 | transforming growth factor, beta 2 | −1.2 | −1.0 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| TGFBR1 | transforming growth factor beta receptor 1 | −1.2 | −1.4 | 1.5 | 1.2 |

| TIRAP | toll interleukin 1 receptor domain containing | −3.0 | −4.4 | −2.0 | 2.9 |

| TNFRSF10A | Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily 10 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.0 |

| UBC | ubiquitin C | 1.1 | −1.2 | −1.1 | −1.6 |

| VCAM1 | vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 | −1.2 | −1.0 | 1.3 | 1.8 |

| VEGF | vascular endothelial growth factor | 1.3 | −1.0 | 1.3 | 1.2 |

| VEGFA | vascular endothelial growth factor A | 1.1 | −1.2 | −1.1 | −1.3 |

| SGK1 | Serum/Glucorticoid-Regulated Kinase 1 | −1.1 | 1.1 | 5.0 | 1.8 |

The quantitative profiling of gene expression was performed using inflammatory signaling cascade array that consisted a panel of 91 human genes and a cytokines and chemokines array that consisted 89 genes, as described in Materials and Methods. Quantitative real time RT-PCR was performed with SYBR green master mix on an iCycler Thermal Cycler. The relative expression level of each target gene was normalized and calculated following 2−ΔΔCt method. Red color: ≥ 1.5-fold increase in expression; Blue color: ≥ 1.5-fold decline in expression with respect to cells incubated with media alone.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells from a donor were incubated in triplicate with media alone, LPS, or T. cruzi for 48 h, and supernatants were utilized to harvest control, LPS-induced and Tc-induced MPs, respectively. THP-1 macrophages were incubated for 12 h with microparticles (in duplicate), and cDNA was submitted for qRT-PCR. The fold change was calculated with respect to THP-1 cells incubated with control MPs.

Microparticles (MPs) were harvested from plasma samples from normal healthy (NH) individuals and seropositive subjects that were clinically asymptomatic (CA) or clinically symptomatic (CS) (n=10 per group). THP-1 macrophages were incubated for 12 h with MPs, and cDNA was submitted for qRT-PCR. The fold change was calculated with respect to THP-1 cells incubated with NH-MPs.

Fig. 1. Macrophage gene expression profile response to microparticles (MPs) released by Tc-infected cells.

Human PBMCs were incubated for 48 h with media alone, LPS or T. cruzi, and supernatants were centrifuged to harvest the control (Con-MPs), LPS-induced (LPS-MPs) and, Tc-induced (Tc-MPs) microparticles. THP-1 macrophages (mφs) were incubated in triplicate with MPs for 12 h. Total RNA from each sample was reverse transcribed, and cDNA was used for quantitative real time RT-PCR with inflammation signaling cascade and cytokine/chemokine arrays. The differential mRNA level was normalized to housekeeping genes and fold change in gene expression was calculated (Table 1). (A) Shown is Venn diagram of comparative analysis of gene expression profile (≥ |1.5| fold change) induced by LPS-MPs and Tc-MPs in comparison to that noted in Con-MP-treated mφs. (B) Bar graph shows the mean differential expression of top molecules (≥ |2.0| fold change) induced by LPS-MPs and Tc-MPs (vs. Con-MPs) in THP-1 mφs.

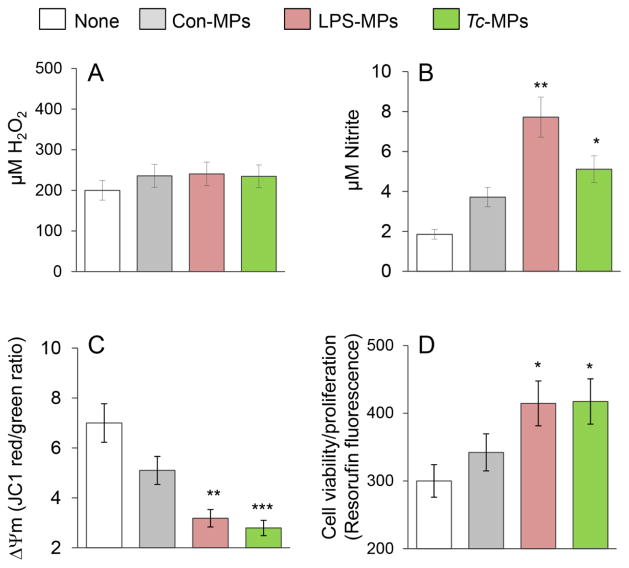

To assess if Tc-induced MPs elicited a functional response in immune cells, we incubated the THP-1 mφs with MPs for 1 h, and examined the oxidative/nitrosative response and mitochondrial stress levels. No increase in H2O2 release (amplex red assay) was induced by LPS-MPs and Tc-MPs when compared to that noted in mφs incubated in media alone or with Con-MPs (Fig. 2A). Macrophages incubated with LPS-MPs and Tc-MPs exhibited a 3.2-fold and 1.7-fold increase in nitrite release, respectively, as compared to THP-1 mφs incubated in media alone (Fig. 2B, p<0.05). JC-1 forms J-aggregates (red) in mitochondria and JC-1 red/green ratio provides a sensitive indicator of cellular stress. The LPS- and Tc-induced MPs elicited a 56% and 60% decline in JC-1 red/green ratio, respectively (Fig. 2C, p<0.01). Macrophage activation is followed by cell proliferation. Resazurin (ala-mar blue) metabolism to fluorescent resorufin by mitochondrial aerobic respiration provides a sensitive measure of cell viability and proliferation. THP-1 mφs incubated with LPS- and Tc-induced MPs for 24 h exhibited 38% increase in resorufin fluorescence as compared to that noted in mφs incubated in media alone (Fig. 2D, p<0.05). Con-MPs elicited 26% decline in JC-1 red/green ratio (p>0.05) and no proliferation in THP-1 mφs. Together, the results presented in Fig. 1 and Fig. 2 suggested that Tc-induced MPs elicited the expression of some of the genes indicative of inflammatory activation in THP-1 mφs, and the immune activation was associated with increase in nitrite release and cell proliferation and a decline in mitochondrial membrane potential in THP-1 mφs. The LPS-induced MPs were more immunostimulatory than the Tc-induced MPs evidenced by the greater induction of pro-inflammatory gene expression and nitrite release by THP-1 mφs.

Fig. 2. Functional response of mφs incubated with Tc-induced MPs.

THP-1 mφs were incubated in triplicate with medium only (none) or with Con-MPs, LPS-MPs and Tc-MPs for 1 h. Supernatants were utilized to measure (A) ROS release by an amplex red assay and (B) nitric oxide production by Griess reagent assay. (C) THP-1 mφs were loaded with JC-1 probe, and change in mitochondrial membrane potential was measured as J aggregates (red)/J monomers (green) ratio by fluorimetry. (D) THP-1 mφs were incubated with MPs or media alone for 21 h, and then loaded with alamarBlue for 3 h. The cell proliferation and viability was determined by resorufin fluorescence. Data are shown as mean value ± SEM, and significance is presented as *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 (no treatment vs. MP-treatment).

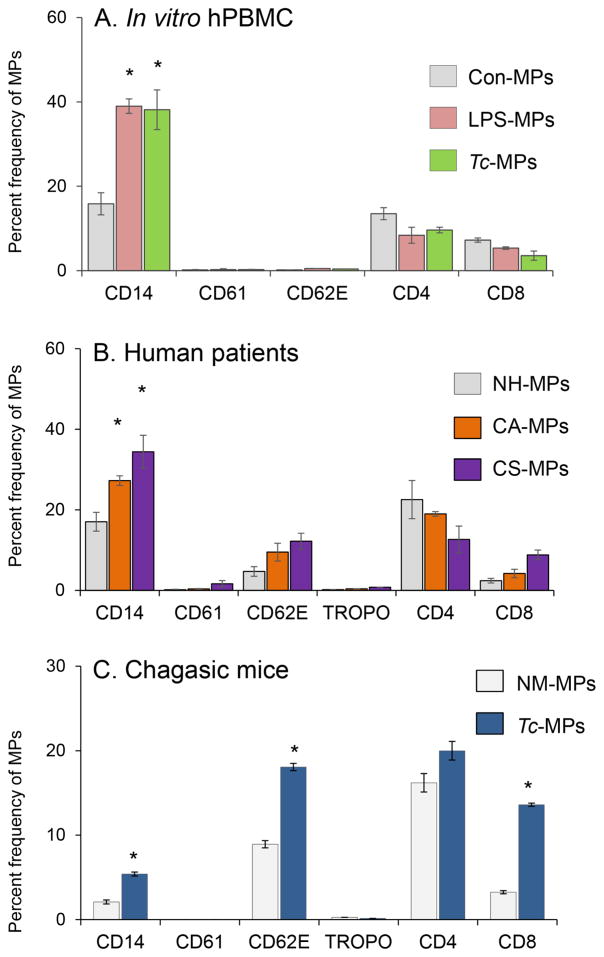

To assess the cellular source of the membranes for MPs released during Tc infection, we took a three-prong approach. One, Tc-induced MPs were isolated from supernatants of human PBMCs incubated for 48 h with T. cruzi, stained with fluorescence-conjugated antibodies against cell-specific markers, and analyzed by flow cytometry. These data showed MPs released by human PBMCs upon Tc infection were primarily of monocyte/macrophage origin (Fig. 3A). Secondly, we examined the phenotype of circulating MPs from chagasic patients. For this, MPs were isolated from plasma of normal healthy (NH) individuals and seropositive subjects characterized as clinically asymptomatic (CA) and clinically symptomatic (CS) for heart disease (n=10 per group), and analyzed, as above (Fig. 3B). These data showed that MPs of platelet (CD61+), or cardiomyocyte (Troponin+) origin constituted <2% of the total circulating MPs in plasma of normal and chagasic individuals (Fig. 3B). A majority of circulating MPs in blood of all human subjects, irrespective of infection and disease status, were of monocyte/macrophage (CD14+), endothelial ( CD62E+), and CD4+/CD8+ T lymphocyte origin (CD14 ≥ CD4 > CD62 = CD8, Fig. 3B). The chagasic subjects exhibited a substantial increase in the frequency of circulatory MPs that were CD14+/CD14hi (up to 2-fold, mφ marker), CD62E+/CD62Ehi (2–3-fold, endothelial marker), or CD8+/CD8hi (4.2 fold, T lymphocytes) (Fig. 3B, p<0.01). Thirdly, MPs were isolated from plasma of mice experimentally infected with T. cruzi, and analyzed by flow cytometry. As noted in human chagasic patients, mice chronically infected with T. cruzi exhibited 2.3-fold, 2-fold and 4.5-fold increase in circulatory MPs of monocytes/macrophage (CD14+), endothelial (CD62E+), and CD8+ T lymphocyte origin, respectively, as compared to that noted in plasma of normal mice (Fig. 3C, p<0.01). Together, these results suggested that circulatory MPs originating from activated endothelial cells, macrophages, and CD8+T cells were enhanced in chagasic patients and chronically infected mice.

Fig. 3. Phenotype of microparticles induced by T. cruzi infection and chronic chagasic disease.

(A&B) MPs were harvested from in vitro infected human PBMCs (as in Fig. 1&2). Plasma samples from seropositive chagasic subjects categorized as clinically asymptomatic (CA) and clinically symptomatic (CS), and normal healthy (NH) controls (n=10 per group) were centrifuged as described in materials and methods and MPs were harvested. Human MPs were labeled with fluorescence-conjugated antibodies against human molecules and analyzed by flow cytometry. Shown are frequency of surface markers of various cellular origin on MPs isolated from control and Tc-infected PBMC’s (A) and chagasic subjects (B). (C) C57BL/6 mice were challenged with T. cruzi (10,000 parasites/mouse, n=5 mice per group per experiment, two experiments), and plasma microparticles were collected at day 120 days post-infection corresponding to chronic disease phase. The MPs were labeled with fluorescence-conjugated antibodies against mouse molecules and analyzed by flow cytometry. Bar graphs (mean ± SEM) show the percent frequency of surface markers of various cellular origin on MPs isolated from media of Tc-infected PBMCs or plasma of chronically infected human patients and experimental mice. Significance (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001) is plotted with respect to normal controls.

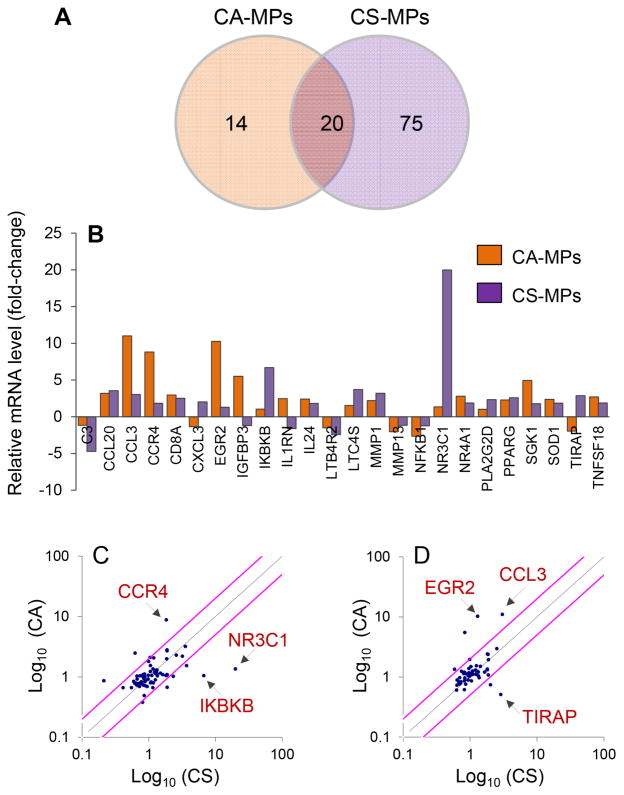

Next, we investigated if circulating MPs present in the plasma of chagasic patients elicited differential THP-1 mφ activation depending upon the clinical disease state. THP-1 mφs were incubated for 12 h with MPs isolated from plasma of NH, CA, and CS subjects (n=10 per group), and total RNA was isolated and reverse transcribed. The cDNA samples from individuals within a group were pooled into two sets, and all samples were analyzed in duplicate by qPCR. The profiling of the gene expression in THP-1mφs using inflammatory signaling cascade and cytokine/chemokine arrays showed 34 genes (9 down-regulated, 25 up-regulated) and 95 genes (16 down-regulated, 79 up-regulated) were differentially expressed (≥|1.5| fold change, p ≤ 0.05) by CA-MPs and CS-MPs, respectively, with respect to MPs of normal healthy (NH) controls (Table 1). Of these, 20 genes were differentially regulated in THP-1 mφs by both CA- and CS-MPs. Further, 14 genes (↑ADRB2, ↑CCR3, TGFBR1, ↑NR4A2, ↑IL1B, ↑CSF1 ↑CCL17, ↑IL6ST, ↑IGFBP3, ↑EGR2, ↓PIM3, ↓TRAF2, ↓MMP13, ↓NFKB1) were differentially expressed in a CA-MP-specific manner, and 7 genes (↑NR3C1, ↑IKBKB, ↑PLA2G2D, ↑CXCL3, ↓C3, ↓NR4A2 and ↓CD14, ≥|2.0| fold) were greatly changed in expression in a CS-MPs-specific manner (Fig. 4A&B). Scatter plots show that CA-MPs elicited maximal up regulation of CCR4, EGR2 and CCL3, while CS-MPs elicited maximal up regulation of IKBKB, NR3C1, and TIRAP in THP-1 mφs (Fig. 4C&D). These results suggested that the circulatory MPs from seropositive, T. cruzi-infected humans elicit a disease stage-specific inflammatory gene expression profile in THP-1 mφs.

Fig. 4. Inflammatory gene expression profile of macrophages in response to microparticles of chagasic patients.

Plasma MPs were isolated from seropositive chagasic subjects categorized as clinically asymptomatic (CA) and clinically symptomatic (CS), and normal healthy (NH) controls (n=10 per group). THP-1 mφ were incubated for 12 h with human microparticles and gene expression profiling was performed by quantitative RT-PCR using inflammation signaling cascade and cytokine/chemokine arrays. The differential mRNA level was normalized to housekeeping genes and fold change in gene expression was calculated in comparison to NH-MP-treated mφs (Table 1). (A) Shown is Venn diagram of differential inflammatory gene expression profile (≥ |1.5| fold change) in mφs incubated with CA-MPs vs. CS-MPs. (B) Bar graph shows the mean differential expression of top molecules (≥ |2.0| fold change) induced by CA-MPs and CS-MPs (vs. NH-MPs) in THP-1 mφs. (C&D) Scatter plots show the CA-MPs versus CS-MPs specific changes in mφ gene expression profile captured by qRT-PCR using the inflammatory signaling cascade (C) and cytokine/chemokine (D) arrays. Pink lines mark the >2-fold difference in expression.

To assess the phenotypic effect of human chagasic patients’ MPs on mφs, we incubated THP-1 mφs for 24 h with NH-, CA- and CS-MPs, and evaluated the surface expression of markers of mφ activation by flow cytometry and cell viability by Alamar blue assay. THP-1 mφs in vitro incubated with recombinant IFNγ, IL4, IL10 cytokines were used as controls. Flow cytometry analysis showed that IFNγ-treated (proinflammatory) mφs were primarily CD80+/CD64+, and IL4- and IL10-treated (immunoregulatory) mφs were CD163+/CD206+. The IL-10-treated THP-1 mφs exhibited CD16hi/CD200hi profile and IL4-treated mφs exhibited CD16lo/CD200lo profile [25]. THP-1 mφs incubated with MPs isolated from the plasma of chagasic patients exhibited no significant change in cell viability and/or cell proliferation (Fig. S1A). Further, incubation of THP-1 mφs with CA-MPs resulted in no change in the expression of any of the surface markers indicative of IFNγ- or IL4/IL10-induced phenotypes when compared to that noted in mφs incubated with NH-MPs (Fig. S1B). The CS-MPs induced CD14+ mφ population consisted of higher number of CD16+ (35%↑)/CD16hi (24%↑), CD64+ (30%↑), CD163hi (10%↑) mφ population when compared to that noted with CA-MPs. We noted no statistically significant change in the population (as well as intensity) of the CD200+ and CD206+ mφ population when incubated with MPs from any of the subject group (Fig. S1B. e&f). These data suggested that CS-MPs may induce greater level of inflammatory activation of macrophages than was induced by CA-MPs, evidenced by increased expression of CD14 and CD16.

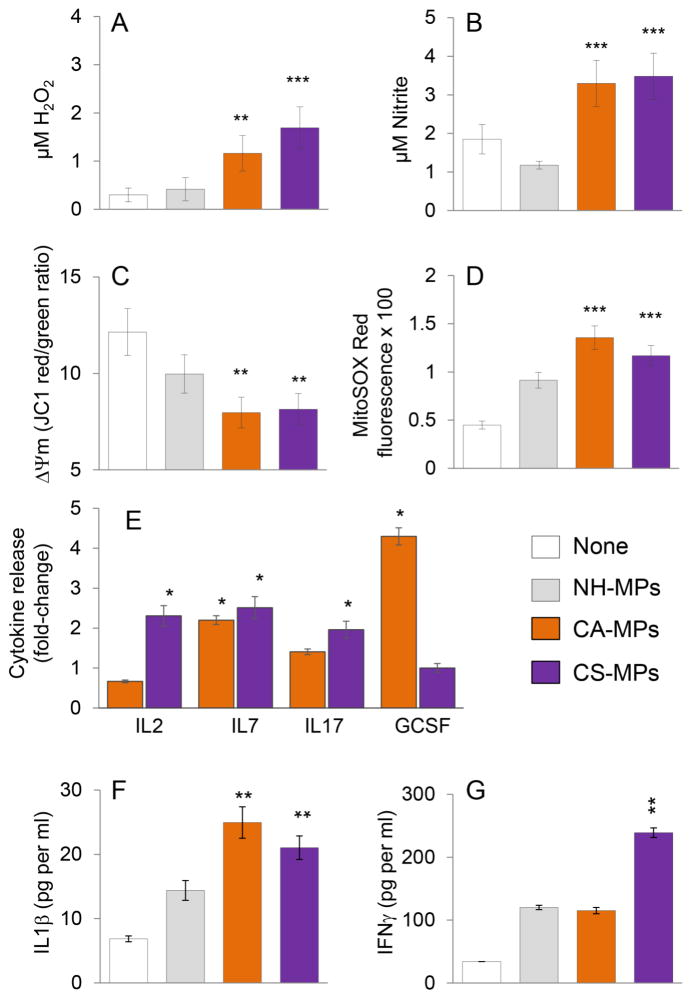

We investigated the functional response of mφs to chagasic patients’ MPs after 1, 24 and 48 hours post stimulation. The ROS and NO generation and mitochondrial stress were examined in THP-1 mφs incubated for 1 h with plasma MPs from NH, CA and CS human subjects (n=10 per group). The THP-1 mφs incubated with CA- or CS-MPs exhibited a 3.8–5.6-fold increase in ROS release (Fig. 5A, p<0.01) and 2.8–3.1-fold increase in NO levels (Fig. 5B, p<0.001), when compared to that noted in mφs incubated with NH-MPs or media only. Further, THP-1 mφs incubated with CA-MPs and CS-MPs, in comparison to mφs incubated with media or NH-MPs, exhibited 33–35% decline in mitochondrial membrane potential (Fig. 5C, p<0.01) and 2.6–3-fold increase in mtROS production (Fig. 5D, p<0.001). A Bio-Plex Multiplex Human Cytokine Assay was employed to evaluate the cytokine release in supernatants of THP-1 mφs incubated for 24 h with MPs from NH, CA and CS subjects (n=10 per group). These data showed up to 2-fold increase in IL7 release by mφs incubated with CA-MPs and CS-MPs (vs. NH-MPs). The CA-MPs also elicited 4-fold increase in GCSF levels, while CS-MPs elicited >2-fold increase in IL2 and IL17 cytokines in THP-1 mφs (Fig. 5E). In another set of experiments, THP-1 mφs were incubated for 48 h with MPs from NH, CA and CS subjects (n=10 per group), and cytokine release in supernatants was evaluated by an ELISA. We noted a ~20% increase in IL4 and no change in IL10 release in mφs incubated with CA- or CS-MPs (vs. NH-MPs, data not shown). Further, THP-1 mφs incubated for 48 h with CA-MPs exhibited 75% increase in IL1β production; and incubation with CS-MPs elicited 50% and 2-fold increase in IL1β and IFNγ release, respectively, when compared to that noted in THP-1 mφs incubated with NH-MPs (Fig. 5F&G, p<0.01). Together, the results presented in Fig. 5 suggested that a) circulatory MPs from CA and CS subjects elicited oxidative and nitrosative stress and cytokine (IL1β and IL7) release in THP-1 mφs compared to when mφs were incubated with media alone or NH-MPs; and b) GCSF and IL2/IFNγ are released by THP-1 mφs in a CA-MPs and CS-MPs-specific manner, respectively.

Fig. 5. Functional activation of mφs by MPs isolated from chagasic patients.

Microparticles were harvested from plasma of seropositive clinically asymptomatic (CA) and clinically symptomatic (CS) subjects. MPs from seronegative normal healthy (NH) individuals were used as controls. (A–D) THP-1 mφs were incubated in triplicate with medium only (none) or with NH, CA, and CS MPs for 1 h. Cell free supernatants were utilized to measure (A) ROS levels by an amplex red assay, and (B) nitrate/nitrite levels by Greiss reagent assay. (C&D) THP-1 mφs were incubated for 1 h with MPs as above. Cells were loaded with JC-1 or MitoSox Red probes, and analyzed by fluorimetry. Shown are changes in mitochondrial membrane potential measured as J aggregates (red)/J monomers (green) ratio (C) and MitosoxRed fluorescence as a measure of mitochondrial ROS production (D). (E) The plasma-derived MPs from NH, CA and CS subjects were added in triplicate to THP-1 mφs. Cells were incubated for 24 h, and supernatants were utilized for Bioplex assay for a panel of 17 human cytokines and chemokines. (F&G) An ELISA was performed to measure the IL1β and IFNγ levels in cell-free supernatants collected at 48 h post-incubation of THP-1 mφs with MPs. In all bar graphs, data are plotted as mean value ± SEM, and significance is presented as *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 (media only or NH MPs (controls) versus CA-MPs or CS-MPs).

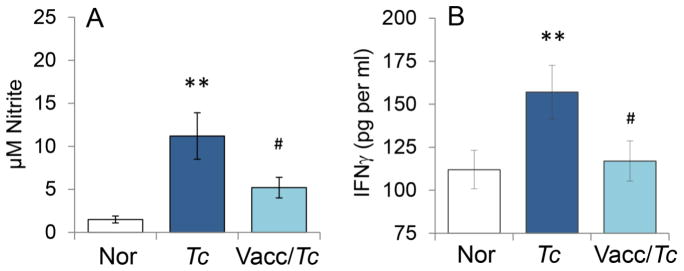

Finally, we determined if the observed differences in macrophage activation by CA- and CS-MPs were reflective of control of parasite and disease. For this, we utilized an experimental model of vaccination against T. cruzi infection. We have previously shown that a subunit vaccine composed of TcG2 and TcG4 antigens of T. cruzi, delivered by DNA-prime/protein-boost approach, was efficacious in controlling parasite burden, myocarditis, and cardiac remodeling in mice [19]. We isolated MPs from plasma of non-vaccinated/infected and vaccinated/infected mice at 120 days pi that corresponds to chronic disease state and incubated the MPs with RAW 264.7 mφs for 48 h. Our data showed that MPs isolated from non-vaccinated/infected (vs. MPs from normal mice) elicited 7.5-fold and 40% increase in •NO and IFNγ production, respectively, in RAW 264.7 mφs (Fig. 6A&B). In comparison, MPs isolated from plasma of TcG2/TcG4-vaccinated/infected mice elicited significantly lower level of •NO release and no IFNγ production (Fig. 6A&B). Together, the results presented in Fig. 6 suggested that vaccine-induced control of infection and disease was associated with a significant decline in MPs’ ability to induce the macrophage activation of •NO and IFNγ response.

Fig. 6. Nitrite and IFN-γ stimulation by microparticles from chagasic mice (± anti-T. cruzi vaccine).

Mice were vaccinated with TcG2/TcG4 candidate antigens, delivered as DNA-prime/protein-boost vaccine as described in Materials and Methods. Two-weeks after last immunization, mice were infected with T. cruzi. MPs were harvested from plasma of non-vaccinated/infected and vaccinated/infected mice at 120 days pi. Microparticles harvested from plasma of non-vaccinated/non-infected (normal) mice were used as controls. RAW 264.7 mφs were incubated in triplicate for 48 h with MPs. Supernatants were utilized for measuring the (A) nitrate/nitrite levels by Greiss reagent assay and (B) IFNγ levels by an ELISA. Data are plotted as mean value ± SEM (n=5 mice per group per experiment, two experiments), and significance is presented as **p<0.01 (non-vaccinated/infected vs. normal controls) and #p<0.05 (non-vaccinated/infected vs. vaccinated/infected).

DISCUSSION

The currently available invasive tools are not practical for routine screening and monitoring the disease status or for predicting the risk of developing full-blown cardiac failure in Tc-infected individuals. The cure in chronic patients is routinely determined based upon the conversion to negative serology, which can take 8 to 10 years post-treatment [26, 27] and occurred in only <15% of treated adult subjects [28, 29]. Further, recently completed BENEFIT clinical trial concluded that trypanocidal therapy with benznidazole in patients with established Chagas cardiomyopathy significantly reduced the serum parasite detection but did not reduce cardiac clinical deterioration during a five year of follow-up. These findings affirmed that conversion to negative serology is not synonymous of cure [30, 31]. Easy-to-use diagnostic tests for determining the patients’ risk of developing clinically symptomatic disease or efficacy of a treatment in controlling infection or arresting disease progression are not available. Therefore, in this study, our goal was to determine whether circulating MPs generated during Tc infection carry the host’s signature of inflammatory/oxidative state and provide information regarding the clinical disease severity. We utilized an in vitro system, samples from chagasic patients exhibiting different stages of disease development, and a murine model of Tc infection and cure by vaccination, and employed high throughput transcriptomic and physiological approaches to study the mφ response to MPs. Our results suggest that MPs released by human PBMCs infected with T. cruzi in vitro or circulatory MPs present in the plasma of chronically infected chagasic patients and experimentally infected mice were primarily of monocytes/macrophage and lymphocyte (CD8>CD4) origin, and exhibited an inflammatory phenotype. This was evidenced by a decline in mitochondrial membrane potential and an increase in proinflammatory gene expression profile, IFNγ and •NO production in macrophages incubated with MPs derived from the three models of T. cruzi infection. The key features of the mφ response to CS-MPs included a pronounced proinflammatory gene expression profile (Fig. 4), an increase in the expression of NR3C1, IKBKB, and TIRAP genes, and substantially higher levels of IFNγ release, while mφ response to CA-MPs was captured by increased expression of CCR4, EGR2 and CCL3, and GCSF production. Further, vaccinated mice, which were previously shown to control parasite persistence and chronic myocarditis [19, 20], produced MPs that elicited no •NO and less of IFNγ in mφs than was noted with MPs of non-vaccinated/infected mice. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating that circulating MPs predict the in vivo levels of oxidative and inflammatory state and have potential utility in evaluating disease severity and efficacy of vaccines and drug therapies against CCM.

Several T. cruzi-derived molecules (e.g. glycosylphosphatidylinositols, mucin-like glycoproteins) act as TLR2 and TLR4 agonists and are described to induce the production of nitric oxide and inflammatory cytokines and chemokines by cells of the monocytic lineage (reviewed in [32]). Others have shown TLR4−/− mφs were deficient in production of trypanocidal •NO and ROS and failed to control parasite replication [33]. TLR3−/−, TLR7−/−, and TLR9−/− mice were also susceptible to T. cruzi infection [34], and it has been suggested that TcDNA-dependent TLRs/MYD88 play an important role in bridging innate to acquired immunity in the context of control of T. cruzi infection. These studies support the role of innate immune cells (e.g. mφs, dendritic cells) in regulating T. cruzi infection. Indeed, host is capable of controlling the acute parasitemia to barely detectable levels. Why then the chronic inflammation pursues in the host is not completely understood. Our results in this study provide some clues to the source of stimulus contributing to persistence of inflammatory infiltrate in Chagas disease. We propose that after control of acute infection, clearance of activated immune cells is necessary to maintain the homeostatic state. During this process, membranes shed by activated immune cells produce circulatory MPs and these MPs may potentially serve as damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) and activate immune cells by engaging Toll-like and Nod-like receptors. This notion is supported by the observation that circulating MPs in chagasic patients and experimentally infected mice were composed of membranes shed by endothelial cells, mφs, and T lymphocytes all of which are known to be activated during infection, and contribute to chronic inflammatory pathology in Chagas disease (reviewed in [35, 36]). Further, MPs present in plasma of chagasic humans and experimentally infected mice were capable of signaling a proinflammatory phenotype in mφs, evidenced by increased proliferation, •NO release, inflammatory gene expression, and cytokine (IL-1β, IFNγ) production. The IL12 and IL18 cytokines are shown to induce IFNγ in mφs [37], and the latter can contribute to the proinflammatory activation of mφs in an autocrine manner [38]. Additional studies evaluating the proteomic and functional profile of circulating MPs will provide insights into the pathological mechanisms that may contribute to generation of MPs; yet, our results provide a strong indication that pro-inflammatory nature of the circulating MPs may at least partially, contribute to persistence of chronic inflammation during Chagas disease.

We have previously shown that incubation of mφs with sera of chagasic mice elicited a proinflammatory phenotype (CD64hi CD80hi) and functional response (increased TNFα/IFNγ production) [25]. In this study, circulatory MPs from chagasic patients and experimentally infected mice produced a similar proinflammatory activation of mφs (Figs. 4–6) as was noted when mφs were incubated with complete sera or plasma of chagasic mice [25]. Incubation with MP-free sera or plasma from chagasic mice or patients elicited no response in mφs (data not shown). These results suggest that MPs, and not the soluble molecules present in systemic circulation, carry the pro-inflammatory signature of Chagas disease.

T. cruzi infection mobilizes innate and adaptive immune responses that induce macrophage activation and keep infection under control [39]. Experimental animals and humans elicit potent adaptive B and T cell immunity to Tc infection, and are capable of controlling the acute circulating and tissue parasite burden [35, 36, 40]. We show that the MPs isolated from clinically symptomatic chagasic patients and experimentally infected mice elicited a substantial increase in cytokines (IL1β, IL7, and IFNγ), ROS, and •NO production in mφs (Fig. 5 & Fig. 6). These results suggest that circulatory MPs constitute a pathomechanism in chronic Chagas disease; and the therapies capable of preventing cellular injury (i.e. inhibiting the generation of MPs) or reprogramming the mφs (i.e. inhibiting pro-inflammatory cytokines, ROS and NO production) will be beneficial in halting the feedback cycle of mφ activation and persistence of pathological inflammatory stress in Chagas disease. This notion is strongly supported by our findings that complete sera or MPs harvested from non-vaccinated/infected (vs. vaccinated/infected) mice elicited pronounced IFNγ and •NO production response in mφs (Fig. 6 and [25]). Likewise, MPs of seropositive individuals that exhibited clinical disease induced a more robust pro-inflammatory gene expression profile, cytokine release (IL1β, IL2, and IFNγ), and mitotoxic phenotype while MPs of seropositive individuals that have yet not developed the clinical disease elicited a mild-to-moderate gene expression profile and no IFNγ in THP-1 mφs (Fig. 4 & Fig. 5).

Nitric oxide release was suppressed in mφs stimulated with MPs from vaccinated/infected mice compared to the MPs from non-vaccinated infected mice; however, we did not observe this trend with the MPs from CA vs CS patients as the MPs from both groups elevated nitric oxide release from THP-1 mφs. We speculate that difference in the RAW 264.7 vs. THP-1 mφs’ ability to respond to mouse vs. human MPs, and the difference in the composition of MPs in mice and humans may contribute to observed outcome with respect to control of nitric oxide release when MPs from infected/vaccinated mice and asymptomatic humans were used. Resistance to T. cruzi infection in humans as well as mice may vary according to the genetic background of the host and the virulence of the parasite strain, and contribute to differential •NO production as well.

In summary, we have used an in vitro system, an experimental model of vaccination, and human chagasic patients, and shown that MPs of monocyte/macrophage and lymphocyte and origin are produced during the course of T. cruzi infection and chronic disease progression, and these MPs elicit a proinflammatory activation of mφs. Our results suggest that MP-induced activation of a differential inflammatory gene expression profile, cytokine release and NO production in mφs reflects the severity of disease state in chagasic host. These results provide us impetus for appraising the MP signature of a large number of individuals exhibiting varying degree of CCM severity. We hope that our MPs and in vitro cell based assays would have the potential utility and power for identifying the risk of clinical disease development and evaluating the efficacy of therapies for control of Chagas disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the consistent and long-standing support of Dr. Ines Vidal (Biochemist of the Central Laboratory of San Bernardo Hospital, Salta, Argentina) and Federico Ramos and Alejandro Uncos (lab technicians) in sample collection and processing and serological testing. In addition, we thank Yolanda Huertas, Rosa Rodas, and Liliana Villagran (Nurses and Office secretary of the cardiology unit at San Bernardo Hospital, Salta, Argentina) for their help in patient recruitment and maintenance of clinical records. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

FUNDING SOURCE

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R01 AI054578 and R21 AI107227) and National Heart Lung Blood Institute (R01 HL094802) to NJG. LS and SG have received a fellowship from the Summer Undergraduate Research Program and Sealy Center for Vaccine Development, respectively, at the UTMB Galveston. SJK is awarded McLaughlin Endowment (UTMB) and American Heart Association pre-doc fellowships. MPZ is supported by Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET), Argentina.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CA

clinically asymptomatic

- CS

clinically symptomatic

- CCM

chagasic cardiomyopathy

- mφs

macrophages

- MPs

microparticles

- NH

normal healthy

- •NO

nitric oxide

- O2•−

superoxide

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- Tc or T. cruzi

Trypanosoma cruzi

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors have no competing interests.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Report of the secretariat. WHO; Geneva: UNDP/World Bank/WHO; 2010. Chagas disease: control and elimination. http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA63/A63_17-en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bern C, Montgomery SP. An estimate of the burden of Chagas disease in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(5):e52–54. doi: 10.1086/605091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanowitz HB, Machado FS, Spray DC, Friedman JM, Weiss OS, Lora J, Nascimento D, Nunes MC, Garg NJ, Ribeiro AL. Developments in the manangement of chagasic cardiomyopathy. Expert Review of Cardiovascular Therapy. 2016;13(12):1393–1409. doi: 10.1586/14779072.2015.1103648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Munoz-Fernandez MA, Fernandez MA, Fresno M. Activation of human macrophages for the killing of intracellular Trypanosoma cruzi by TNF-alpha and IFN-gamma through a nitric oxide-dependent mechanism. Immunol Lett. 1992;33(1):35–40. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(92)90090-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plasman N, Metz G, Vray B. Interferon-gamma-activated immature macrophages exhibit a high Trypanosoma cruzi infection rate associated with a low production of both nitric oxide and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Parasitol Res. 1994;80(7):554–558. doi: 10.1007/BF00933002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alvarez MN, Peluffo G, Piacenza L, Radi R. Intraphagosomal peroxynitrite as a macrophage-derived cytotoxin against internalized Trypanosoma cruzi: consequences for oxidative killing and role of microbial peroxiredoxins in infectivity. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(8):6627–6640. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.167247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cardoso MS, Reis-Cunha JL, Bartholomeu DC. Evasion of the Immune Response by Trypanosoma cruzi during Acute Infection. Front Immunol. 2015;6:659. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang L, Tarleton RL. Parasite persistence correlates with disease severity and localization in chronic Chagas’ disease. J Infect Dis. 1999;180(2):480–486. doi: 10.1086/314889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wen JJ, Dhiman M, Whorton EB, Garg NJ. Tissue-specific oxidative imbalance and mitochondrial dysfunction during Trypanosoma cruzi infection in mice. Microbes Infect. 2008;10(10–11):1201–1209. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wen J-J, Bhatia V, Popov VL, Garg NJ. Phenyl-alpha-tert-butyl nitrone reverses mitochondrial decay in acute Chagas disease. Am J Pathol. 2006;169(6):1953–1964. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wen J-J, Gupta S, Guan Z, Dhiman M, Condon D, Lui CY, Garg NJ. Phenyl-alpha-tert-butyl-nitrone and benzonidazole treatment controlled the mitochondrial oxidative stress and evolution of cardiomyopathy in chronic chagasic rats. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(22):2499–2508. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dhiman M, Wan X-X, PLV, Vargas G, Garg NJ. MnSODtg mice control myocardial inflammatory and oxidative stress and remodeling responses elicited in chronic Chagas disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2(5):e000302. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dhiman M, Garg NJ. NADPH oxidase inhibition ameliorates Trypanosoma cruzi-induced myocarditis during Chagas disease. J Pathol. 2011;225(4):583–596. doi: 10.1002/path.2975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dhiman M, Garg NJ. P47phox−/− mice are compromised in expansion and activation of CD8+ T cells and susceptible to Trypanosoma cruzi infection. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10(12):e1004516. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dhiman M, Zago MP, Nunez S, Nunez-Burgio F, Garg NJ. Cardiac oxidized antigens are targets of immune recognition by antibodies and potential molecular determinants in Chagas disease pathogenesis. Plos One. 2012;7(1):e28449. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burnouf T, Chou ML, Goubran H, Cognasse F, Garraud O, Seghatchian J. An overview of the role of microparticles/microvesicles in blood components: Are they clinically beneficial or harmful? Transfus Apher Sci. 2015;53(2):137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2015.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shantsila E, Kamphuisen PW, Lip GY. Circulating microparticles in cardiovascular disease: implications for atherogenesis and atherothrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8(11):2358–2368. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.04007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wen JJ, Zago MP, Nunez S, Gupta S, Nunez Burgos F, Garg NJ. Serum proteomic signature of human chagasic patients for the identification of novel protein biomarkers of disease. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11(8):435–452. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M112.017640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gupta S, Garg NJ. Prophylactic efficacy of TcVac2R against Trypanosoma cruzi in mice. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4(8):e797. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta S, Garg NJ. A Two-Component DNA-prime/Protein-boost vaccination strategy for eliciting long-term, protective T cell immunity against Trypanosoma cruzi. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11(5):e1004828. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dey N, Sinha M, Gupta S, Gonzalez MN, Fang R, Endsley JJ, Luxon BA, Garg NJ. Caspase-1/ASC inflammasome-mediated activation of IL-1beta-ROS-NF-kappaB pathway for control of Trypanosoma cruzi replication and survival is dispensable in NLRP3−/− macrophages. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e111539. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robertson RC, Guiheneuf F, Bahar B, Schmid M, Stengel DB, Fitzgerald GF, Ross RP, Stanton C. The anti-inflammatory effect of algae-derived lipid extracts on lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated human THP-1 macrophages. Mar Drugs. 2015;13(8):5402–5424. doi: 10.3390/md13085402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crean D, Cummins EP, Bahar B, Mohan H, McMorrow JP, Murphy EP. Adenosine modulates NR4A orphan nuclear receptors to attenuate hyperinflammatory responses in monocytic cells. J Immunol. 2015;195(4):1436–1448. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kleinbongard P, Rassaf T, Dejam A, Kerber S, Kelm M. Griess method for nitrite measurement of aqueous and protein-containing samples. Methods Enzymol. 2002;359:158–168. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)59180-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gupta S, Silva TS, Osizugbo JE, Tucker L, Spratt HM, Garg NJ. Serum mediated activation of macrophages reflects Tcvac2 vaccine efficacy against Chagas disease. Infection & Immunity. 2014;82(4):1382–1389. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01186-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cancado JR. Long term evaluation of etiological treatment of chagas disease with benznidazole. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2002;44(1):29–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cancado JR. Criteria of Chagas disease cure. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1999;94(Suppl 1):331–335. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761999000700064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Viotti R, Vigliano C, Lococo B, Bertocci G, Petti M, Alvarez MG, Postan M, Armenti AH. Long term cardiac outcome of treating chronic Chagas disease with benznidazole versus no treatment: a nonrandomized trial. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2006;144:724–734. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-10-200605160-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fabbro DL, Streiger ML, Arias ED, Bizai ML, del Barco M, Amicone NA. Trypanocide treatment among adults with chronic Chagas disease living in Santa Fe city (Argentina), over a mean follow-up of 21 years: parasitological, serological and clinical evolution. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2007;40(1):1–10. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822007000100001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bautista-Lopez NL, Morillo CA, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Quiroz R, Luengas C, Silva SY, Galipeau J, Lalu MM, Schulz R. Matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 as diagnostic markers in the progression to Chagas cardiomyopathy. Am Heart J. 2013;165(4):558–566. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morillo CA, Marin-Neto JA, Avezum A, Sosa-Estani S, Rassi A, Jr, Rosas F, Villena E, Quiroz R, Bonilla R, Britto C, et al. Randomized Trial of Benznidazole for Chronic Chagas’ Cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(14):1295–1306. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodrigues MM, Oliveira AC, Bellio M. The Immune Response to Trypanosoma cruzi: Role of Toll-Like Receptors and Perspectives for Vaccine Development. J Parasitol Res. 2012;2012:507874. doi: 10.1155/2012/507874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oliveira AC, de Alencar BC, Tzelepis F, Klezewsky W, da Silva RN, Neves FS, Cavalcanti GS, Boscardin S, Nunes MP, Santiago MF, et al. Impaired innate immunity in Tlr4(−/−) mice but preserved CD8+ T cell responses against Trypanosoma cruzi in Tlr4-, Tlr2-, Tlr9- or Myd88-deficient mice. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(4):e1000870. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caetano BC, Carmo BB, Melo MB, Cerny A, dos Santos SL, Bartholomeu DC, Golenbock DT, Gazzinelli RT. Requirement of UNC93B1 reveals a critical role for TLR7 in host resistance to primary infection with Trypanosoma cruzi. J Immunol. 2011;187(4):1903–1911. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Machado FS, Dutra WO, Esper L, Gollob KJ, Teixeira MM, Weiss LM, Nagajyothi F, Tanowitz HB, Garg NJ. Current understanding of immunity to Trypanosoma cruzi infection and pathogenesis of Chagas disease. Seminars in Immunopathology. 2012;34(6):753–770. doi: 10.1007/s00281-012-0351-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tanowitz HB, Wen JJ, Machado FS, Desruisseaux MS, Robello C, Garg NJ. Trypanosoma cruzi and Chagas disease: innate immunity, ROS, and cardiovascular system. Waltham, MA: Academic Press / Elsevier Inc; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Darwich L, Coma G, Pena R, Bellido R, Blanco EJ, Este JA, Borras FE, Clotet B, Ruiz L, Rosell A, et al. Secretion of interferon-gamma by human macrophages demonstrated at the single-cell level after costimulation with interleukin (IL)-12 plus IL-18. Immunology. 2009;126(3):386–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02905.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Munder M, Mallo M, Eichmann K, Modolell M. Murine macrophages secrete interferon gamma upon combined stimulation with interleukin (IL)-12 and IL-18: A novel pathway of autocrine macrophage activation. J Exp Med. 1998;187(12):2103–2108. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.12.2103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ribeiro-Gomes FL, Lopes MF, DosReis GA. NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine NIoH, editor. Madame Curie Bioscience Database. Austin TX: Landes Bioscience; 2000. Negative signaling and modulation of macrophage function in Trypanosoma cruzi infection. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nagajyothi F, Machado FS, Burleigh BA, Jelicks LA, Scherer PE, Mukherjee S, Lisanti MP, Weiss LM, Garg NJ, Tanowitz HB. Mechanisms of Trypanosoma cruzi persistence in Chagas disease. Cell Microbiol. 2012;14(5):634–643. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2012.01764.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.