Abstract

Purpose

Early identification of ischemic stroke plays a significant role in treatment and potential recovery of damaged brain tissue. In non-contrast CT (ncCT), the differences between ischemic changes and healthy tissue are usually very subtle during the hyper-acute phase (<8 hours from the stroke onset). Therefore, visual comparison of both hemispheres is an important step in clinical assessment. A quantitative symmetry-based analysis of texture features of ischemic lesions in non-contrast CT images may provide an important information for differentiation of ischemic and healthy brain tissue in this phase.

Methods

One hundred thirty-nine (139) ncCT scans of hyperacute ischemic stroke with follow-up magnetic resonance diffusion-weighted (MR-DW) images were collected. The regions of stroke were identified in the MR-DW images, which were spatially aligned to corresponding ncCT images. A state-of-the-art symmetric diffeomorphic image registration was utilized for the alignment of CT and MR-DW, for identification of individual brain hemispheres, and for localization of the region representing healthy tissue contralateral to the stroke cores. Texture analysis included extraction and classification of co-occurrence and run length texture-based image features in the regions of ischemic stroke and their contralateral regions.

Results

The classification schemes achieved area under the receiver operating characteristic [Az] ≈ 0.82 for the whole dataset. There was no statistically significant difference in the performance of classifiers for the data sets with time between 2 and 8 hours from symptom onset. The performance of the classifiers did not depend on the size of the stroke regions.

Conclusions

The results provide a set of optimal texture features which are suitable for distinguishing between hyperacute ischemic lesions and their corresponding contralateral brain tissue in non-contrast CT. This work is an initial step towards development of an automated decision support system for detection of hyperacute ischemic stroke lesions on non-contrast CT of the brain.

Keywords: Hyperacute ischemic stroke, noncontrast computed tomography (ncCT) classification, image registration, texture analysis

1. Introduction

Ischemic stroke is a pathological event caused by an interruption of blood supply to brain tissue, resulting in death of the tissue. Implementing effective therapy as soon as stroke is confirmed is critical 1, 2, and at some time around 4.5 to 8 hours, the use of thrombolytic therapy is contraindicated.

While ncCT typically may require hours for signs of stroke to be visually recognized by radiologists, MR-DW providing Diffusion Weighted Image (DWI) and Apparent Diffusion Coefficient Map (ADC) has been reported to be abnormal in some cases as early as 30 minutes after stroke onset 3. Furthermore, compared to the low-density changes in ncCT, the ADC values are more specific for acute ischemic stroke, since chronic stroke is also seen as low density on ncCT. However, because of reduced accessibility of magnetic resonance (MR) at emergency departments, and various challenges of scanning patients suspected of stroke, non-contrast computed tomography (ncCT) is usually the first choice imaging modality. Treatment is thus usually based on clinical impression, with ncCT primarily focused on ruling out hemorrhage (a contraindication to thrombolytic therapy), with detection/confirmation of ischemic stroke being an added benefit.

Although the signs suggesting ischemic stroke on ncCT images have been studied 4-6, they are not always visible within first eight hours from the stroke onset (usually referred as the hyperacute phase)7. Moreover, increased workloads and odd work hours can decrease the sensitivity of trained neuroradiologists to subtle changes of the brain tissue in ncCT.

In the recent literature, several approaches for automated detection of ischemic changes in the human brain can be found. These approaches are based on image filtering aimed at enhancing the visibility of stroke lesions 8, 9, spatial normalization between the examined brain and an average template of healthy controls 10, 11, topographic scoring of middle cerebral artery (MCA) territories 12, 13, supervised classification of image texture features 14, and other imaging biomarkers 7.

Previous studies have reported on stroke detection but have some weaknesses, including: 1) Follow-up MR-DW scans were not always used as an independent gold-standard for stroke, suggesting some visible signs for localization of ischemic stroke lesions were present in the ncCTs. 2) The time between the stroke onset and the analyzed ncCT scan was not clearly stated in most studies. 3) Although the contralateral brain tissue was considered a reference, it was identified in 2D slices, which could lead to false spatial correspondences in some cases due to head rotation / tilt during the scanning. 4) Only one approach for detection of ischemic stroke utilized texture features in the ncCT 14. 5) Only one classifier was tested for discrimination between the healthy and stroke tissue. 6) The number of subjects in many studies was small.

In our study, we collected ncCT scans of 139 patients admitted to the stroke service with follow-up diffusion weighted MR scans acquired within 96 hours from the stroke symptom onset. We localized all hyperacute ischemic stroke regions in the ncCT scans based on these follow-up MR scans transformed into the ncCT space. We identified contralateral brain regions representing corresponding unaffected brain tissue via the state-of-the-art 3D symmetric diffeomorphic image registration (SyN) of the brain hemispheres 15. Subsequently, we extracted 18 texture features (8 Haralick 16 and 10 Run Length 17) from the ischemic stroke regions and their contralateral brain regions. We analyzed these high-dimensional feature datasets 18, 19 by utilizing three supervised classification methods (Support Vector Machine [SVM] 20, AdaBoost [ADA] 21, and Decision Trees [DT] 22).

2. Materials

Our Institutional Review Board waived the requirement for informed consent for this study. Our dataset was built using the following inclusion criteria:

Patients with both ncCT and MR-DWI examination

The time between symptom onset and the first ncCT scan ≤8h

The time between the stroke onset and MRI scans of the brain ≤96h

Patients with no confounding pathology

Acute stroke was clinically confirmed by an experienced stroke neurologist

The time of image acquisition was extracted from the Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) images. The time of stroke onset was based on clinical history provided by an independent observer and was entered into a stroke registry prior to the conduct of this study.

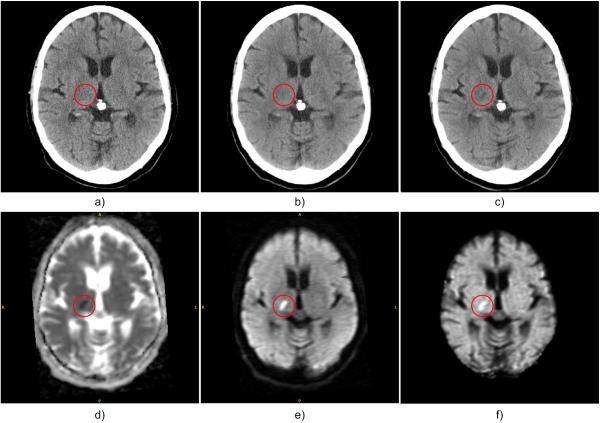

The CT and MR image data (Fig. 1) were acquired for routine clinical care for stroke at our hospital between 2009 and 2012. According to the inclusion criteria, a dataset of 139 patients (75 men and 64 women) was identified as meeting the inclusion criteria. The ncCT images were acquired using a CT Siemens Sensation 64 with the following scanning parameters: 120kV, 570-590mAs (tube current), and 0.4883×0.4883×5mm (x, y - pixel spacing and slice thickness). The MR-DWI images were acquired using a 1.5T whole-body MR scanner. The DWI scan parameters were as follows: TR = 10–11s, TE = 76–92.3ms, b=1000, with spatial resolution 1.6406×1.6406×4 mm (x, y - pixel spacing and slice thickness).

Fig. 1.

Example of hyperacute ischemic stroke region (in red circle): a) first ncCT (1h 51min); b) second co-registered ncCT (4h 19min); c) third co-registered ncCT (24h 3min) shows a stroke lesion that matches the MR-DW abnormality; d) MR-ADC (48h 18min); e) MR-DWI; f) MR-eADC. The times in parentheses denote the time differences between stroke onset and the actual scans.

3. Methods

3.1. Localization of hyperacute stroke lesions in ncCT

The spatial resolution of the follow-up MR-DW images was different from the resolution of the corresponding ncCT images. Therefore, a b-spline interpolation of the MR images was applied to match the resolution of the ncCT images first. The MR images including Apparent Diffusion Coefficient map (ADC), exponential ADC map (eADC) and diffusion weighted image (DWI) were then geometrically transformed to the space of the reference ncCT images based on the optimal transformation parameters found via multimodal rigid image registration between the ncCT and the interpolated MR-DWI. In order to identify ischemic stroke lesions, an initial binary mask roughly representing non-stroke and stroke regions on the ADC was created based on intensity intervals applied to the ADC map (750×10-6 mm2/s < ADChealthy < 1300×10-6 mm2/s for non-stroke region and 100×10-6 mm2/s < ADCstroke < 640×10-6 mm2/s for stroke regions). In the second step, a tissue statistics were calculated for non-stroke region on the DWI (DWIhealthy), and a binary mask representing stroke lesions on DWI was created based on absolute threshold determined as DWIlesion > Mean(DWIhealthy) + 2×STD(DWIhealthy), based on Straka et al.23 In the third step, candidate stroke lesions were determined as the intersection of the binary masks representing stroke lesions in the DWI and the ADC map. Finally, volume filtering was applied to remove small objects (<0.5ml) from the candidate stroke lesions segmented primarily due to noise in the MR-DW images.

Since the intensity profile of ischemic lesions in the MR brain images may slightly vary based on the affected brain tissue properties and their proximity to skull or cerebrospinal fluid (e.g. susceptibility artifacts), the candidate stroke lesions were additionally visually inspected by an experienced neuro-radiologist, and manually corrected if necessary.

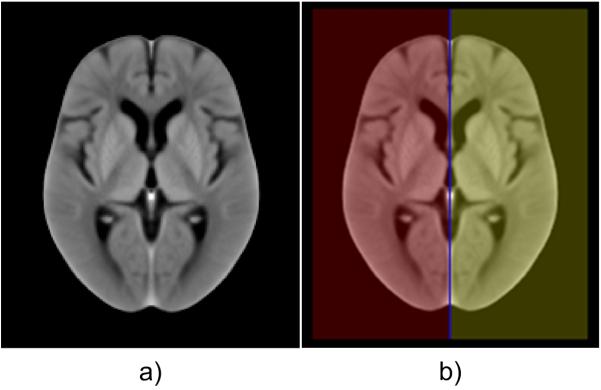

3.2. Identification of reference contralateral regions

In the first step, individual brain hemispheres were identified on ncCT examinations via image registration of a symmetric in-house created ncCT brain template and a subsequent transformation of its binary mask. The ncCT template was based on 40 ncCT examinations co-registered via affine and symmetric diffeomorphic image registration (SyN), and modified according to Rorden et al. 24, resulting in an isotropic symmetric ncCT template (Fig. 2a). This template was complemented with a binary mask (Fig. 2b) overlaying individual hemispheres (red and yellow) and the longitudinal interhemispheric fissure (LIF, blue). The same template was applied for male and female patients. The ncCT examinations of elderly control subjects (77.3 ± 10.1 years, 19M of 75.2 ± 11.0 years, 21W of 79.1 ± 9.0 years) without pathologies were obtained from an internal database at our institution.

Fig. 2.

a) The average symmetric in-house ncCT template representing a healthy elderly population, b) The binary mask of individual hemispheres (red and yellow) and longitudinal interhemispheric fissure (LIF, blue).

In the second step, the reference contralateral regions representing healthy brain tissue (ROIHT) and spatially corresponding to the stroke lesions (ROIS) in the contralateral hemisphere were found via rigid and SyN image registration of the individual hemispheres.

3.3. Texture analysis

Run Length Matrix features

Run length matrix (RLM) 25, 26 statistics capture the coarseness of texture in a specified direction. A run is defined as a string of consecutive voxels that have the same gray level intensity along a planar orientation. For each run length matrix, 10 features were calculated 17. The mean of each feature over the 4 run length matrices (corresponding to 4 directions) was calculated, comprising a total of 10 RLM-based features (Long Run High Grey Level Emphasis, Long Run Low Grey Level Emphasis, Short Run High Grey Level Emphasis, Grey Level Non-uniformity, High Grey Level Run Emphasis, Long Run Emphasis, Low Grey Level Run Emphasis, Run Length Non-uniformity, Short Run Emphasis, Short Run Low Grey Level Emphasis).

Gray level co-occurrence matrix

The Gray level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM) is a well-established tool for characterizing the spatial distribution of gray levels in an image's second order statistics 16. The mean of each feature over the 4 GLCM-derived features (corresponding to 4 directions: 0, 45, 90, 135 degrees) was calculated, comprising a total of 8 GLCM features (Cluster Prominence, Cluster Shade, Correlation, Energy, Entropy, Haralick Correlation, Inertia, and Inverse Difference Moment).

3.4. Classification

Using the above-mentioned textural features as inputs, three different classifiers were used to differentiate between stroke regions and the contralateral regions. We used 3 different types to increase confidence in the robustness of features. The stepwise discriminant analysis (SDA) was employed for feature selection. The features were normalized to zero mean and unit variance.

Support Vector Machine

The support vector machine (SVM) classifier originally proposed by Vapnik 27 aims to compute the hyperplane (boundary) that maximizes the margin between the feature vectors of the two categories considered in this study. For cases where the data are not linearly separable, the original input space can be translated to a higher-dimensional feature space using a basis function. This mapping enables the classifier to deal with nonlinear boundaries. Among several options in the literature for the basis function (radial basis, sigmoid or d-th degree polynomial), we chose the radial basis function 28 for this study. Basis functions like sigmoid will introduce two extra parameters thus making parameter selection difficult while the d-th degree polynomial is unbounded a characteristic that could potentially lead to numerical instabilities. The parameter C, which controls the tradeoff between margin maximization and error minimization, and σ were automatically derived according to the radius-margin bound method 29. Larger C values mean that a higher penalty is assigned to the misclassified cases, and σ defines the impact of a single training example.

Decision Trees

The main idea behind decision trees (DT) 22 is the representation of the problem as a series of decisions (resembling a tree structure) that find a strong relationship between input values and target values in a group of observations that form a data set. The DT consists of leaf nodes and decision nodes. The leaf node indicates the value of the targeted class while the decision node specifies a test to be performed on a single attitude value. An example is set as input to the root of the tree and proceeds through the decision nodes until it arrives in a leaf node. A set of splitting rules is applied one after another resulting in a hierarchy of branches within branches mimicking the appearance of an inverted tree.

AdaBoost

Boosting is based on the idea of creating a highly accurate prediction rule by combining a set of weak rules. The Adaboost classifier 21 is an iterative procedure which starts by applying a classifier to the original dataset to produce class labels. The weighting of misclassified data points is increased (boosting) to try to reduce misclassifications. Subsequently, a second classifier is applied utilizing the new weights. The above process is repeated for all the misclassified points. For each weak classifier a score is assigned, the final classifier is constructed as the linear combination of the classifier from each stage. For the purpose of this study, the decision tree was utilized as the weak classifier.

3.5. Parameter Selection

All the parameters of the classifier involved in this study, the binning of the gray scale levels (GL) and the size of the filtered window (FWS) used to create the texture filtered version of the images, were obtained utilizing a grid search method. The area under ROC curve was used for the selection of the optimal models. In order to avoid overfitting, 10-fold cross validation was implemented for all the classification schemes in this study. The area under ROC curve was estimated for each one of the k-fold cross-validations and the average of the values was used to select the best combination of parameters.

In the case of the SVM classifier, the parameters C and σ were also determined via grid search while the same applies to the Decision Trees classifier for the number of decision leafs. In this study, the grid consisted of four different filtering window sizes FWS ∈ (3, 5, 7, 9) and three different binning gray levels GL ∈ (32, 64, 128). For SVM, the values were σ ∈ (1,0.01) in steps of 0.01 and C ∈ (2−4,2−3,2−3,...,24,25), whereas in the case of decision trees, 16 different decision leafs were considered, L∈ (1,3,... ,31) in steps of 2.

3.6. Analysis Methodology

We evaluated the significance of various texture features found in the hyperacute ischemic stroke lesions and their contralateral regions with respect to two assumptions.

-

a)

Various time windows between stroke onset time and the first ncCT scan (Table 1). We tested whether there was a significant difference regarding our texture-based detection of stroke-affected tissue in the individual time windows. In general, the later the first ncCT scan from the stroke onset was acquired, the more significant hypoattenuation in the affected tissue up to approximately 24 hours after onset of symptoms.

-

b)

Various sizes of stroke lesions.

Table 1.

Evaluation dataset and groups of patients with respect to the time of stroke onset to the first ncCT scan.

| Group | Stroke onset to ncCT | Patients | Men [age] | Women [age] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.0h < t ≤ 1.0h | 17 | 3 [72.3 ± 10.3] | 14 [69.0 ± 16.1] |

| 2 | 1.0h < t ≤ 2.0h | 43 | 29 [68.4 ± 16.7] | 14 [75.4 ± 11.4] |

| 3 | 2.0h < t ≤ 3.0h | 23 | 9 [76.4 ± 18.6] | 14 [70.4 ± 15.9] |

| 4 | 3.0h < t ≤ 4.5h | 30 | 17 [70.6 ± 17.2] | 13 [78.3 ± 10.0] |

| 5 | 4.5h < t ≤ 8.0h | 26 | 17 [67.9 ± 15.1] | 9 [76.2 ± 12.9] |

| 6 | 0.0h < t ≤ 8.0h | 139 | 75 [69.9 ± 16.3] | 64 [73.6 ± 13.6] |

We tested whether there was a significant impact of lesion size on our texture-based detection of the stroke-affected tissue by separating lesions into size ranges (Table 2).

Table 2.

The groups of patients according to the total lesion sizes.

| Group | Lesion volume [ml] | Patients | Men [age] | Women [age] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.5 – 1.5 | 61 | 30 [69.9 ± 14.2] | 31 [72.9 ± 16.2] |

| 2 | 1.5 - 7 | 31 | 15 [71.3 ± 12.2] | 16 [74.6 ± 9.7] |

| 3 | 7 - 164 | 46 | 29 [68.8 ± 20.3] | 17 [74.1 ± 12.2] |

3.7. Statistical Analysis

To compare the classification performance of the different classification schemes and tasks, the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed, and the Az was calculated 30. The pROC ver. 1.7.3 package for R ver. 3.2.1 was used for the ROC curve and Az calculations, with the DeLong method 31 used for statistical comparison of ROC curves.

4. Results

4.1. Atlas-based image registration

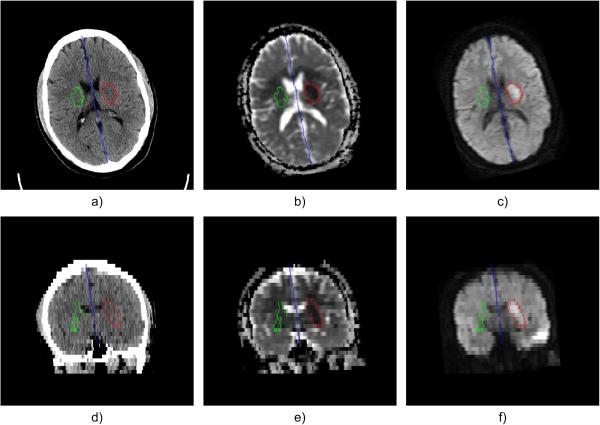

The results of image registration between the in-house ncCT template and individual ncCT examinations and between ncCT and corresponding MR-DW examinations were visually inspected in axial, sagittal and coronal views. The alignment of co-registered anatomical structures was visually inspected using a checkerboard method combining the fixed ncCT image and the transformed images (template, DWI). The longitudinal interhemispheric fissure (Fig. 3, blue color) in axial and the coronal views shows slight head tilt and rotation signaling that there is not exact axial correspondence of contralateral anatomical structures. Therefore, 3D registration seems suitable for delineation of regions contralateral to the stroke lesions.

Fig. 3.

LIF (blue), ischemic stroke lesion (red) and contralateral region (green) in axial direction: a) ncCT, b) co-registered ADC map, c) co-registered DWI; Corresponding coronal views in d), e), f)

An example of delineated hyperacute ischemic stroke lesion (ROIS, red) and contralateral region representing healthy tissue (ROIHT, green) is shown in Fig. 3.

4.2. Analysis of texture features

Taking into account all individual stroke groups in Table 1 and Table 2, the following six texture features were most important for distinguishing stroke lesions based on their corresponding contralateral brain regions for the all the combinations of tested FWS and GL:

- High gray level run emphasis

- Short run high gray level emphasis

- Long run high gray level emphasis

- Haralick correlation

- Entropy

- Cluster prominence

Table 3 and Table 4 summarize the parameters of the best classification schemes when applied using the dataset divided according to the onset selection criteria (Table 1) and size criteria (Table 2) respectively. No statistical difference between the three classifiers was observed, as their performance was almost the same.

Table 3.

Selected parameters of the best classification schemes according to AUC using the subset based on stroke onset criteria

| Group | SVM (GL/FWS) | DT (GL/FWS) | ADA (GL/FWS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.664 (128/5) | 0.674 (128/7) | 0.764 (128/5) |

| 2 | 0.734 (32/7) | 0.736 (128/9) | 0.746 (32/7) |

| 3 | 0.836 (64/5) | 0.837 (128/5) | 0.850 (64/5) |

| 4 | 0.847 (32/9) | 0.846 (32/9) | 0.839 (32/9) |

| 5 | 0.938 (128/9) | 0.956 (128/9) | 0.957 (128/9) |

| 6 | 0.812 (64/7) | 0.827 (32/5) | 0.832 (32/5) |

Table 4.

Selected parameters of the best classification schemes according to AUC using the subset based on size criteria

| Group | SVM (GL/FWS) | DT (GL/FWS) | ADA (GL/FWS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.892 (128/3) | 0.883 (128/3) | 0.912 (128/3) |

| 2 | 0.843 (32/5) | 0.858 (32/5) | 0.849 (32/5) |

| 3 | 0.819 (64/7) | 0.829 (64/7) | 0.831 (32/5) |

Based on our results, the classifiers’ performance did not depend on the size of the stroke regions. All the classification schemes evaluated in this investigation performed poorly for data with onset between 0.0h < t ≤ 2.0h. For onset time between 2 < t ≤ 3 hours and 3 < t ≤ 4.5 hours, the performance of the classifiers was approximately Az=0.85 and no difference was observed. All classifiers considered in this study achieved the highest accuracy when applied to the dataset with onset between 4.5 and 8 hours (0.938 ≤ Az ≤ 0.957).

Discussion

In comparison with the previous studies 7, 11, 14, we localized individual hyperacute ischemic lesions in ncCT images semi-automatically based on the fusion of the follow-up diffusion weighted MR images. In contrast to the approach proposed in 14, we utilized 3D image registration for identification of healthy tissue (ROIHT) corresponding to individual stroke lesions (ROIs) in the contralateral brain hemispheres.

In combination with three common classifiers (SVM, DT, and ADA), we analyzed 18 texture features, and we tested a number of filtering window sizes and gray levels binning. We stratified the database according to the time between the stroke onset and the first ncCT scan, and the size of the stroke lesions to assess the robustness of the selected features.

The classifiers utilized in this study are three of the most commonly utilized classifiers in the literature. Each classifier has different characteristics and behavior when it comes to deal with complex data. For instance, decision trees are non-parametric, easy to interpret, and can deal with both linearly or nonlinearly separable data. SVM is more resistant to overfitting due to the use of regularization (C). Furthermore, the no free lunch theorem 32 suggests that there is no a priori superiority for any classifier or the other.

Currently in the literature a variety of feature selection algorithms exist. Cross validation can lead to over-optimistic results owing to selection bias33. In order to prevent the selection bias in obtaining optimal features, the features for each classifier and parameter combination were selected beforehand utilizing stepwise discriminant analysis (SDA). In this way, each of the three classifiers considered in this study had the same features as input for each parameter combination. We choose SDA since it performs a multivariate test of differences between groups. In addition, it can determine the minimum number of dimensions (in our case features) needed to describe these differences. Since the dataset utilized in this study is not big while on the other hand the number of features calculated is large, a feature selection step was necessary.

Although Haralick 16 proposed 14 texture features, we build on previous work of Tang et. al 14, who linked the selected Haralick features with underlying ischemic stroke signs visible in ncCT brain images. We take into account the proposed set of Haralick features and we extend the study with additional family of texture features at this point. Further extension of the set of texture features is possible and will be investigated in the future.

Apart from the Cluster prominence, Haralick correlation, and Entropy, which were identified previously also by Tang et al. 14, we showed that High gray level run emphasis, Short run high gray level emphasis and Long run high gray level emphasis should be considered for texture-based detection of hyperacute stroke lesion as well.

Pseudonormalization of MR-DW images in stroke is a recognized phenomenon and may introduce a concern about the time-window used as inclusion criteria for this study. However, a study on pseudonormalization time course 34 reports that this typically occurs at two weeks, and maximum ADC abnormality is typically around 45 hours. The authors also showed maximum DWI signal was at 3 days, and pseudonormalization was maximum at 14 days +/− 6.5 days. Therefore our time window was at or near optimum, and we do not believe pseudonormalization is likely to have occurred in our subject group.

One of the limitations in our study is that we compared the textures only between the stroke lesions and considered the contralateral regions as normal. While it would be uncommon for there to be symetrical acute strokes, it is somewhat possible that there could be old ischemic lesions or other pathology in the contraletral region. This would most likely reduce the accuracy of our method. Further investigation is needed with respect to the selected features when the task is the differentiation of the stroke regions versus other non-pathological regions in the brain. Additionally, further investigation is needed to improve the low performance obtained for the group with onset 0.0h < t ≤ 2.0h.

6. Conclusions

We quantitatively analyzed lesions of hyperacute ischemic stroke localized in clinical non-contrast CT examinations of 139 patients via image registration of their corresponding follow-up MR-DWI examination. In contrast to previously published studies, the purpose of this study was to highlight the value of texture features when combined with supervised classification schemes. In addition, we utilized a 3D registration-based technique for identification of individual brain hemispheres and contralateral brain regions in an effort to capture the textural differences. The results provide a set of texture features that are suitable for distinguishing between hyperacute ischemic lesions and their corresponding contralateral brain tissue in non-contrast CT. The findings of this study can be considered a first step of efforts towards development of a computer-aided system for the detection of hyperacute ischemic stroke in ncCT.

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding: Supported by the European Regional Development Fund - Project FNUSA-ICRC (No. CZ.1.05/1.1.00/02.0123) and the NIH Grant U01 CA160045.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Zoppo G.J.d., Saver JL, Jauch EC, Adams HP. Expansion of the Time Window for Treatment of Acute Ischemic Stroke With Intravenous Tissue Plasminogen Activator A Science Advisory From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2009;40:2945–2948. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.192535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E, Brozman M, Dávalos A, Guidetti D, Larrue V, Lees KR, Medeghri Z, Machnig T, Schneider D, von Kummer R, Wahlgren N, Toni D. Thrombolysis with Alteplase 3 to 4.5 Hours after Acute Ischemic Stroke. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;359:1317–1329. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwamm LH, Koroshetz WJ, Sorensen AG, Wang B, Copen WA, Budzik R, Rordorf G, Buonanno FS, Schaefer PW, Gonzalez RG. Time Course of Lesion Development in Patients With Acute Stroke Serial Diffusion- and Hemodynamic-Weighted Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Stroke. 1998;29:2268–2276. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.11.2268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wardlaw JM, von Kummer R, Farrall AJ, Chappell FM, Hill M, Perry D. A large web-based observer reliability study of early ischaemic signs on computed tomography. The Acute Cerebral CT Evaluation of Stroke Study (ACCESS) PloS one. 2010;5:e15757. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Srinivasan A, Goyal M, Azri FA, Lum C. State-of-the-Art Imaging of Acute Stroke. Radiographics. 2006;26:S75–S95. doi: 10.1148/rg.26si065501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khalaf HS, Ahmed SY, Kurman AJ. Caudate body (CB) sign: new early CT sign of hyperacute anterior cerebral circulation infarction. Emergency radiology. 2011;18:533–538. doi: 10.1007/s10140-011-0979-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nowinski WL, Gupta V, Qian G, He J, Poh LE, Ambrosius W, Chrzan RM, Polonara G, Mazzoni C, Mol M, Salvolini L, Walecki J, Salvolini U, Urbanik A, Kazmierski R. Automatic detection, localization, and volume estimation of ischemic infarcts in noncontrast computed tomographic scans: method and preliminary results. Investigative radiology. 2013;48:661–670. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e31828d8403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takahashi N, Lee Y, Tsai D-Y, Ishii K, Kinoshita T, Tamura H, Kimura M. Improvement of detection of hypoattenuation in acute ischemic stroke in unenhanced computed tomography using an adaptive smoothing filter. Acta radiologica (Stockholm, Sweden: 1987) 2008;49:816–826. doi: 10.1080/02841850802126570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Przelaskowski A, Sklinda K, Bargieł P, Walecki J, Biesiadko-Matuszewska M, Kazubek M. Improved early stroke detection: Wavelet-based perception enhancement of computerized tomography exams. Computers in Biology and Medicine. 2007;37:524–533. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takahashi N, Tsai D-Y, Lee Y, Kinoshita T, Ishii K. Z-score Mapping Method for Extracting Hypoattenuation Areas of Hyperacute Stroke in Unenhanced CT. Academic Radiology. 2010;17:84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gillebert CR, Humphreys GW, Mantini D. Automated delineation of stroke lesions using brain CT images. NeuroImage: Clinical. 2014;4:540–548. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takahashi N, Tsai D-Y, Lee Y, Kinoshita T, Ishii K, Tamura H, Takahashi S. Usefulness of z-score mapping for quantification of extent of hypoattenuation regions of hyperacute stroke in unenhanced computed tomography: analysis of radiologists' performance. Journal of computer assisted tomography. 2010;34:751–756. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e3181e66473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takahashi N, Lee Y, Tsai D-Y, Kinoshita T, Ouchi N, Ishii K. Computer-aided detection scheme for identification of hypoattenuation of acute stroke in unenhanced CT. Radiological physics and technology. 2012;5:98–104. doi: 10.1007/s12194-011-0143-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang F.-h., Ng DKS, Chow DHK. An image feature approach for computer-aided detection of ischemic stroke. Computers in Biology and Medicine. 2011;41:529–536. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Avants BB, Tustison NJ, Song G, Cook PA, Klein A, Gee JC. A Reproducible Evaluation of ANTs Similarity Metric Performance in Brain Image Registration. NeuroImage. 2011;54:2033–2044. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haralick RM, Shanmugam K, Dinstein IH. Textural Features for Image Classification. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man and Cybernetics SMC-3. 1973:610–621. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galloway MM. Texture analysis using gray level run lengths. Computer Graphics and Image Processing. 1975;4:172–179. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robert JG, Paul EK, Hedvig H. Radiomics: Images Are More than Pictures, They Are Data. Radiology. 2016;278:563–577. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015151169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parekh V, Jacobs MA. Radiomics: a new application from established techniques. Expert Review of Precision Medicine and Drug Development. 2016;1:207–226. doi: 10.1080/23808993.2016.1164013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cortes C, Vapnik V. Support-Vector Networks. Mach Learn. 1995;20:273–297. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Friedman J, Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Additive logistic regression: a statistical view of boosting (With discussion and a rejoinder by the authors) The Annals of Statistics. 2000;28:337–407. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rokach L, Maimon O. Top-Down Induction of Decision Trees Classifiers - A Survey. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man and Cybernetics, Part C (Applications and Reviews) 2005;35:476–487. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Straka M, Albers GW, Bammer R. Real-time diffusion-perfusion mismatch analysis in acute stroke. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging: JMRI. 2010;32:1024–1037. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rorden C, Bonilha L, Fridriksson J, Bender B, Karnath H-O. Age-specific CT and MRI templates for spatial normalization. NeuroImage. 2012;61:957–965. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xiaoou T. Texture information in run-length matrices. Trans. Img. Proc. 1998;7:1602–1609. doi: 10.1109/83.725367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loh HH, Leu JG, Luo RC. The analysis of natural textures using run length features. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics. 1988;35:323–328. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vapnik, N. V. The nature of statistical learning theory. Springer-Verlag New York, Inc.; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen S, Zhou S, Yin F-F, Marks LB, Das SK. Investigation of the support vector machine algorithm to predict lung radiation-induced pneumonitis. Medical physics. 2007;34:3808–3814. doi: 10.1118/1.2776669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keerthi SS. Efficient tuning of SVM hyperparameters using radius/margin bound and iterative algorithms. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks. 2002;13:1225–1229. doi: 10.1109/TNN.2002.1031955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bradley AP. The use of the area under the ROC curve in the evaluation of machine learning algorithms. Pattern Recognition. 1997;30:1145–1159. [Google Scholar]

- 31.DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the Areas under Two or More Correlated Receiver Operating Characteristic Curves: A Nonparametric Approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:837–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolpert DH, Macready WG. No free lunch theorems for optimization. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation. 1997;1:67–82. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Varma S, Simon R. Bias in error estimation when using cross-validation for model selection. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:91–91. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Axer H, Gräβel D, Brämer D, Fitzek S, Kaiser WA, Witte OW, Fitzek C. Time course of diffusion imaging in acute brainstem infarcts. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2007;26:905–912. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]