Abstract

IL-36γ is a member of novel IL-1-like pro-inflammatory cytokine family that are highly expressed in epithelial tissues and several myeloid-derived cell types. Little is known about the role of the IL-36 family in mucosal immunity, including lung antibacterial responses. We utilized murine models of IL-36γ deficiency to assess the contribution of IL-36γ in the lung during experimental pneumonia. Induction of IL-36γ was observed in the lung in response to Streptococcus pneumoniae (Sp) infection, and mature IL-36γ protein was secreted primarily in microparticles. IL-36γ-deficient mice challenged with Sp demonstrated increased mortality, decreased lung bacterial clearance and increased bacterial dissemination, in association with reduced local expression of type-1 cytokines, and impaired lung macrophage M1 polarization. IL-36γ directly stimulated type-1 cytokine induction from dendritic cells in-vitro in a MyD88-dependent fashion. Similar protective effects of IL-36γ were observed in a Gram-negative pneumonia model (Klebsiella pneumoniae). Intrapulmonary delivery of IL-36γ-containing microparticles reconstituted immunity in IL-36γ−/ − mice. Enhanced expression of IL-36γ was also observed in plasma and BALF of patients with ARDS due to pneumonia. These studies indicate that IL-36γ assumes a vital proximal role in the lung innate mucosal immunity during bacterial pneumonia by driving protective type 1 responses and classical macrophage activation.

Keywords: Innate Immunity, interleukins, pneumonia, IL-36

Introduction

Type-1 cytokines are required for effective clearance of Streptococcus pneumoniae (Sp) (1) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (Kp) (2–4) in the lung. Lung dendritic cells (DC) promote development of type-1 immune responses via elaboration of IL-12 and IL-23 (5,6). IL-12 induces IFNγ, which is important for effective innate immunity against a variety of bacterial pathogens (7,8). IL-23 drives type-1 and IL-17-mediated responses, which are protective in bacterial pneumonia (3, 9). Survival is diminished with deficiencies in either IL-12 or -23 due to impaired bacterial clearance (10). Early IFNγ production by innate cells promotes cytokine and chemokine expression, which synergistically enhance alveolar macrophage (AM) and neutrophil (PMN) effector responses, and stimulate antimicrobial peptide (AMP) expression (11–14).

Interleukin-36 (IL-36) is the collective name for three novel members of the IL-1 superfamily of cytokines: IL-36α, -β, and -γ (15, 16). They share a common receptor, IL-36R, which bears significant homology to the classical IL-1 type I receptor (IL-1R) (17). Binding of IL-36 to IL-36R recruits IL-1RAcP, a shared accessory protein with IL-1R, activating NF-κB and MAPKs. IL-36Ra and IL-38 are IL-36R antagonists, which prevent the association of IL-36R with IL-1RAcP (18, 19). IL-36 family members are expressed by a variety of cell types, with abundant expression in epithelial cells (16) and monocytes (20, 21). IL-36 exerts proinflammatory effects, which is best characterized in models of psoriasis. IL-36 is highly expressed in skin (16, 22–25). In animal models of psoriasis, IL-36 induces Th17 cytokines, AMPs, and other inflammatory cytokines (24–27). IL-36 also has effects on myeloid cells. DC, macrophages, and T cells express IL-36R (28). Recent data suggests that IL-36 activates DC and promotes type-1 and Th17 responses (28). For instance, IL-36α and -β promote Th1 polarization of naïve T cells. Furthermore, incubation of peripheral blood monocytes with Aspergillus fumigatus in-vitro induces IL-36γ expression, and blockade of IL-36Ra enhances IFNγ and IL-17 production (29). In the lung, IL-36 family members are expressed in tracheal and bronchial epithelial cells and fibroblasts in response to various inflammatory stimuli (30–34). However, full delineation of IL-36 cell sources, mechanisms of secretion, or IL-36-responsive cell types has yet to be determined.

In this study, we examined the role of IL-36γ during experimental pneumonia due to the Gram-positive bacteria Streptococcus pneumoniae (Sp) and the Gram-negative pathogen Klebsiella pneumoniae (Kp). We demonstrate that IL-36γ is selectively induced in the lung and secreted into the alveolar space predominantly in membrane-bound vesicles during infection. Moreover, IL-36γ deficiency results in impaired lung bacterial clearance and enhanced dissemination, culminating in increased mortality. Finally, we demonstrate that IL-36γ potently induces type-1 cytokines from DC during the evolution of bacterial pneumonia, promoting classical (M1) macrophage activation.

Results

IL-36γ, but not IL-36α or –β, is induced in the lung during pneumococcal pneumonia

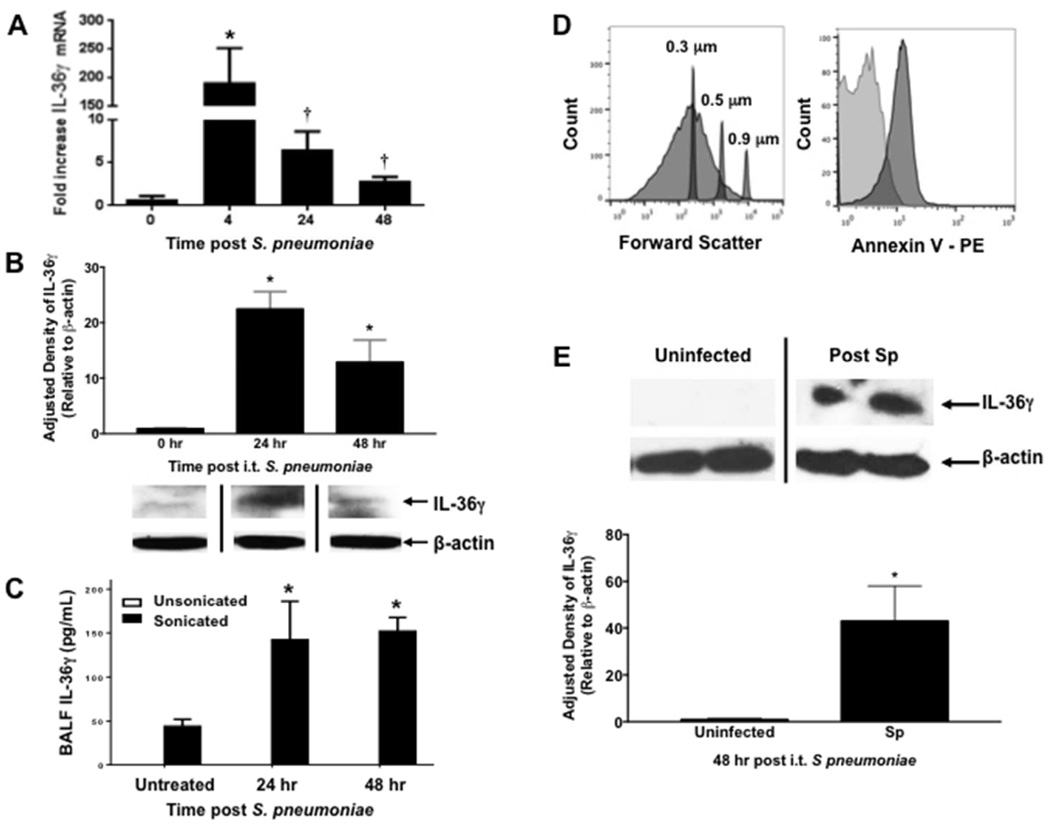

To understand the role of IL-36 family members during Gram-positive pneumonia, we first assessed IL-36 agonist induction after i.t. S. pneumoniae (Sp) inoculation (3–5×104 CFU). IL-36 was measured in whole lungs of Sp-infected mice by qRT-PCR at 4, 24, and 48 hours after bacterial challenge. We observed a striking peak in induction of IL-36γ mRNA (175-fold increase, p < 0.01) 4 hours after infection (Figure 1A). Levels declined over 48 hours, but remained significantly above that observed in uninfected lungs (p < 0.05). Interestingly, we observed no induction of IL-36α or –β mRNA in whole lung post infection.

Fig. 1. Effect of S. pneumoniae on IL-36γ induction and secretion in the lung.

(A) WT mice were infected with an i.t. injection of Sp (5 × 104 CFU), and lungs were harvested at the specified time points. (*p < 0.01 and †p < 0.05 as compared to uninfected mice by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, n = 4 per time point, representative of 3 experiments). (B) Representative Western immunoblot of whole lung homogenates from Sp-infected WT mice were assessed for IL-36γ with β-actin as a housekeeping control. Bands are representative of 2 separate experiments of n = 3 replicates per group. Densitometry represents relative density compared to β-actin from all replicates pooled from both experiments. (*p < 0.01 compared with uninfected mice by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test). (C) BAL fluid from Sp-infected WT mice was assessed by IL-36γ ELISA with or without sonication. (*p < 0.05 as compared to untreated mice by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, n = 6 per group, representative of 2 experiments). (D) MP from infected mice were assessed by flow cytometry for size relative to sub-micron size calibration beads (panel 1). MP were then gated to select DAPI-negative particles, corresponding to viable MP (not shown). MP were stained for either Annexin V-PE or a PE-labeled isotype control IgG (panel 2). Within 95% confidence intervals as compared to isotype controls, 80% of particles were Annexin V-positive (representative of 3 separate experiments). (E) Representative Western immunoblot of isolated MP from Sp-infected WT mice were stained for IL-36γ with β-actin as a housekeeping control (n = 2 per group, representative of 5 experiments). Densitometry represents relative density compared to β-actin from all replicates pooled from all experiments. (*p < 0.05 compared with MP from uninfected mice by two-tailed student’s t test).

We next analyzed whole lung homogenates of Sp-infected mice for IL-36γ protein by Western blotting (Figure 1B). There was no detectable constitutive IL-36γ expression in uninfected animals. Maximal expression was observed at 24 hours after Sp challenge. To quantitate IL-36γ secretion into the alveolar space, mice were administered Sp i.t. followed by BAL at 24 and 48 hours post infection. IL-36α and -γ were measured by ELISA. No IL-36γ was detected at any time points in cell-free BAL fluid (Figure 1C). We previously reported that IL-36γ is secreted from activated pulmonary macrophages (PM) in a non-classical fashion via packaging within microparticles (MP) and, to a lesser extent, exosomes in-vitro (35). Interestingly, upon sonication of cell-free BALF to disrupt membrane-bound vesicles, we observed a significant increase in IL-36γ detection in BALF at 24 and 48 hours after Sp challenge, suggesting that IL-36γ is contained within membrane-bound structures in the airspace in-vivo. No IL-36α was detected at either time point in either unsonicated or sonicated BALF, which is concordant with a lack of mRNA induction.

IL-36γ is released into the alveolar space within MP in response to i.t. S. pneumoniae

To confirm that IL-36γ was secreted in MP in response to Sp infection, BALF was collected from mice 48 hrs after i.t. Sp infection, and centrifuged as described in the methods to isolate MP. The MP pellet was resuspended in buffer, stained with annexin V, and assessed by flow cytometry (Figure 1D). Particles were present in BALF in the size range of MP (100–500 nm) as compared to size-calibrated microspheres. After gating on DAPI-negative particles to exclude those without intact membranes, >85% of particles stained positively for Annexin-V, consistent with MP. To establish the presence of IL-36γ within the MP fraction, ultracentrifuged BALF from uninfected and Sp-infected mice consisting of the MP fraction was analyzed by Western blotting (Figure 1E). We detected IL-36γ protein in the MP fraction of Sp-infected, but not uninfected, mice.

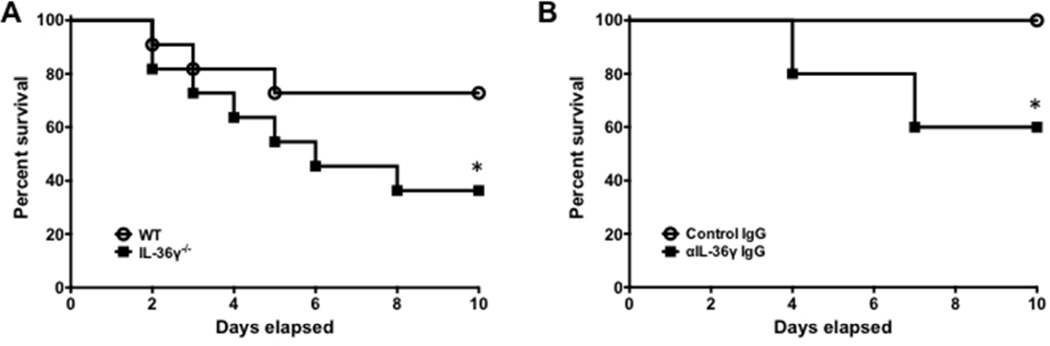

IL-36γ deficiency results in increased mortality during pneumococcal pneumonia

To examine the impact of IL-36γ on survival, animals were infected with Sp and observed until time of death. We employed models of both genetic deletion (Figure 2A) and antibody-mediated neutralization of IL-36γ (Figure 2B). Using an approximate LD0–25 dose of Sp in WT mice (1–5×104 CFU), we observed 27% mortality in WT mice by 10 days. In comparison, mortality was significantly higher (64%) in IL-36γ−/− mice (p < 0.05). In antibody neutralization studies, administration of anti-mouse IL-36γ antibody resulted in 40% mortality in Sp-infected mice, whereas all control IgG treated mice survived (p < 0.05).

Fig. 2. Effect of IL-36γ on mortality during pneumococcal pneumonia.

(A) WT and IL-36γ−/− mice were infected with i.t. Sp and observed. (*p < 0.05, n = 11 mice/group, combined from 2 separate experiments). (B) Animals were passively immunized with either a control IgG or an anti-IL-36γ IgG and then infected with i.t. Sp. (*p < 0.05 by Mantel-Cox test, n = 8 mice/group, combined from 2 separate experiments).

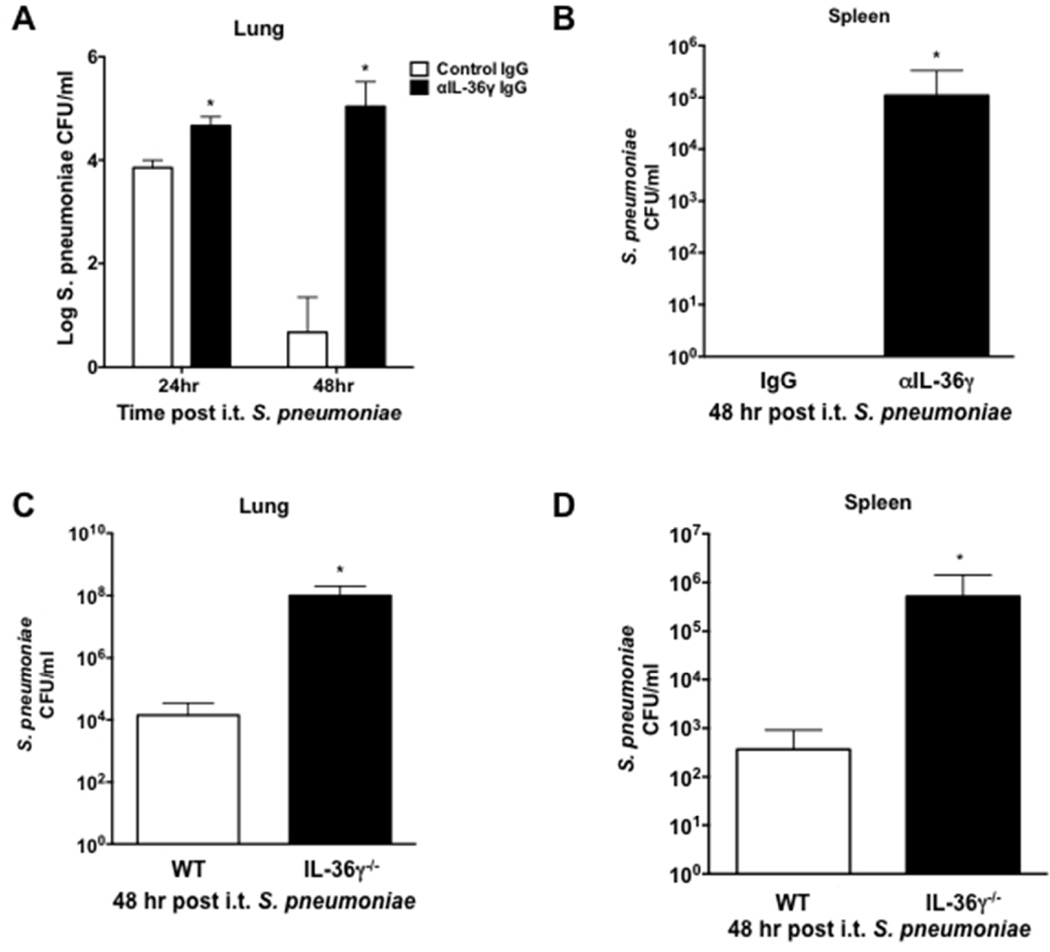

IL-36γ deficiency results in impaired lung bacterial clearance and increased dissemination

We next sought to explore mechanisms behind increased mortality in IL-36γ-deficient mice. Animals, including both genetic deletion and antibody neutralization models, were challenged with i.t. Sp (8×104 CFU) and lungs and spleen were harvested at 24 and 48 hours after infection (Figure 3). At 24 hours post infection, there was an approximately ten-fold increase in bacterial CFU in lungs of anti-IL-36γ-treated mice as compared to control antibody-treated mice (Figure 3A). By 48 hours, Sp CFU were significantly reduced in WT animals but persistently elevated in anti-IL-36γ-treated mice (>4 log difference in CFU, p < 0.001). Antibody neutralization also resulted in marked bacterial dissemination by 48 hrs, whereas no dissemination was observed in control IgG-treated mice (p < 0.05, Figure 3B). IL-36γ−/− mice demonstrated similar defects in lung bacterial clearance at 48 hrs compared to WT, with nearly 7,000-fold greater CFU in IL-36γ−/− mice as compared to WT (p < 0.001, Figure 3C). Moreover, increased dissemination was observed in IL-36γ−/− mice compared to WT mice (1,500-fold difference in spleen CFU, p < 0.05, Figure 3D).

Fig. 3. Effect of IL-36γ on lung bacterial clearance and dissemination.

(A–B) Mice were passively immunized with either a control IgG or an anti-IL-36γ IgG and infected with i.t. Sp. Lungs and spleen were harvested at the specified time points. (A) Lung CFU were assessed by serial dilution (*p < 0.05 and †p < 0.01 as compared to control IgG-treated mice by two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test, n = 4 mice/group, representative of 2 experiments). (B) Spleen CFU were assessed by serial dilution at 48 hours (*p < 0.001 compared to control IgG-treated mice by two-tailed student’s t test, n = 4 mice/group, representative of 2 experiments). (C–D) WT and IL-36γ−/− were infected with i.t. Sp, and lungs and spleen were harvested at 48 hrs post infection. (C) Lung CFU were assessed by serial dilution at 48 hrs (*p < 0.05 compared to WT by two-tailed student’s t test, n = 4 mice/group, representative of 3 experiments). (D) Spleen CFU were assessed by serial dilution at 48 hrs (*p < 0.001 compared to WT by two-tailed student’s t test, n = 4 mice/group, representative of 3 experiments).

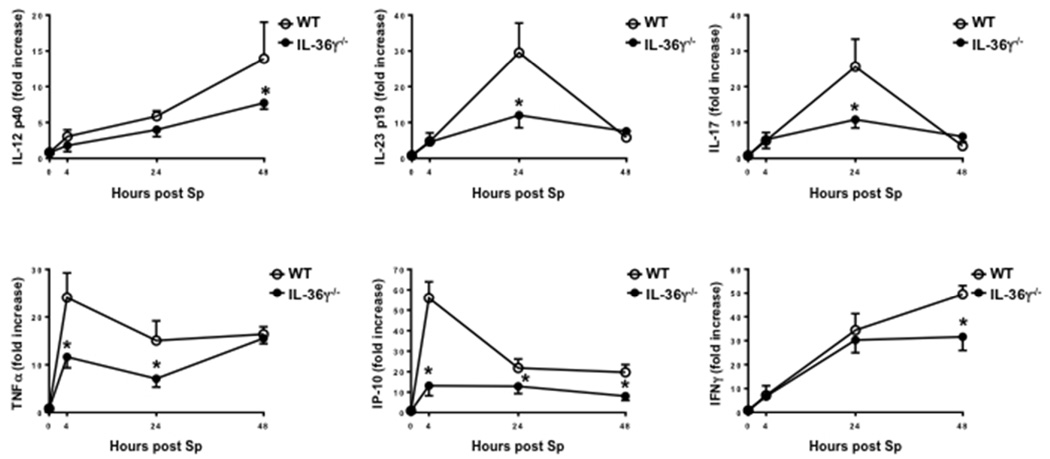

IL-36γ deficiency impairs expression of type-1 and IL-17 cytokines during pneumococcal pneumonia

We next examined the effects of IL-36γ deficiency on induction of type-1 and IL-17 cytokines during Sp infection. WT and IL-36γ−/− mice were challenged with i.t. Sp (5–8×104 CFU), and lungs were harvested at 0, 4, 24 and 48 hours after administration (Figure 4). As compared to WT animals, we observed significant reductions in the early mRNA expression of the type-1 cytokines TNFα and IP-10/CXCL10 at 4 and 24 hours in Sp-infected IL-36γ−/− mice. Decreased expression of IL-23p19 and IL-17 was observed by 24 hours. Reduced IL-12p40 and IFNγ expression was also observed in IL-36γ−/− mice by 48 hrs post infection.

Fig. 4. Effect of IL-36γ on Type I and IL-17-inducing cytokine induction.

WT and IL-36γ−/− mice were infected with i.t. Sp. Cytokines were measured from whole lung homogenates at the specified time points. (* p < 0.05 compared to WT at the same time point by two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test; n= 6 mice/group per time point, representative of 3 separate experiments).

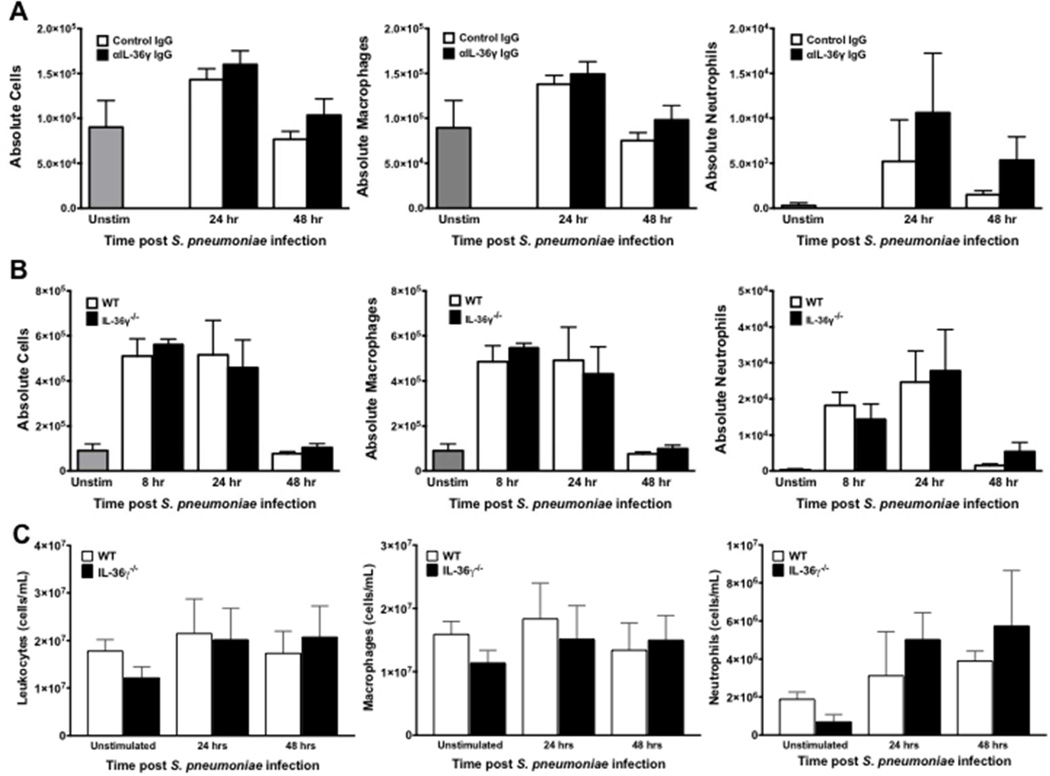

Differences in bacterial clearance and dissemination are not due to impaired alveolar leukocyte influx or antimicrobial peptide expression

Additional experiments were performed to determine whether differences in survival, bacterial clearance, and dissemination were due to impairments in alveolar leukocyte influx during infection. Control and IL-36γ-depleted/deficient mice were infected with i.t. Sp (5–8×104 CFU) and BAL leukocytes were enumerated at 8, 24, and 48 hours after infection (Figure 5A–B). We observed no significant differences in either total leukocyte or AM counts in anti-IL-36γ antibody-treated animals as compared to control antibody-treated mice at 24 or 48 hours. There was a modest but insignificant increase in neutrophils in anti-IL-36γ antibody-treated mice compared to controls at 24 and 48 hours, likely reflecting increased lung bacterial burden in IL-36γ-depleted animals. Similarly, no significant differences were seen in total leukocytes, macrophages, or neutrophils at any time points following Sp administration in IL-36γ−/− mice compared to controls (Figure 5B).

Fig. 5. Effect of IL-36γ on inflammatory cell recruitment.

(A) WT mice were passively immunized with either a control IgG or anti-IL-36γ IgG and infected with i.t. Sp. Total BAL leukocytes were quantified, and macrophage and neutrophil counts were assessed by manual differential (No significant differences between groups at the same time point by one-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test, n = 5 mice/group, representative of 2 experiments). (B) WT and IL-36γ−/− were infected with i.t. Sp. Total leukocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils were assessed as above (No significant differences between groups at the same time point by one-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test, n = 4–6 mice/group, representative of 3 experiments). (C) WT and IL-36γ−/− were infected with i.t. Sp. Lungs were homogenized at the specified time points and otal leukocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils were assessed by manual differential (No significant differences between groups at the same time point by one-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test, n=3 mice per group per time point).

After determining that leukocyte influx into the alveolar space was unaffected by IL-36γ, we next assessed whether IL-36γ influences whole lung cellularity, including interstitial leukocytes. WT and IL-36γ−/− mice were infected with i.t. Sp (5–8×104 CFU). Whole lung tissue was collected and homogenized at 0, 24, and 48 hours after infection, and leukocytes were enumerated (Figure 5C). Unstimulated IL-36γ−/− showed a small but statistically insignificant decrease in both macrophages and neutrophils relative to WT mice. Following infection, there were again no significant differences in total leukocytes or leukocyte subsets between WT and IL-36γ−/− mice. As with BAL neutrophils, we observed a modest but statistically insignificant increase in whole lung neutrophils in IL-36γ−/− mice as compared with WT mice.

IL-36 family members have been reported to induce antimicrobial peptide expression in models of psoriasis (24). To assess whether antimicrobial expression may be induced by IL-36γ in lung cells, we treated isolated alveolar and interstitial pulmonary macrophages (PM), type II alveolar epithelial cells (AEC) and bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDC). Cells were treated in-vitro with 50 ng/mL recombinant IL-36γ and cellular mRNA was analyzed for cathelicidin-related antimicrobial peptide (Cnlp) and β-defensin-3 6 hours after stimulation (Supplemental Figure S1). There were no significant differences in expression of either antimicrobial peptide in any of the cell types tested. Moreover, we did not observe differences in mRNA expression of Cnlp and β-defensin mRNA in whole lung from WT and IL-36γ mice in-vivo during the course of Sp infection (data not shown).

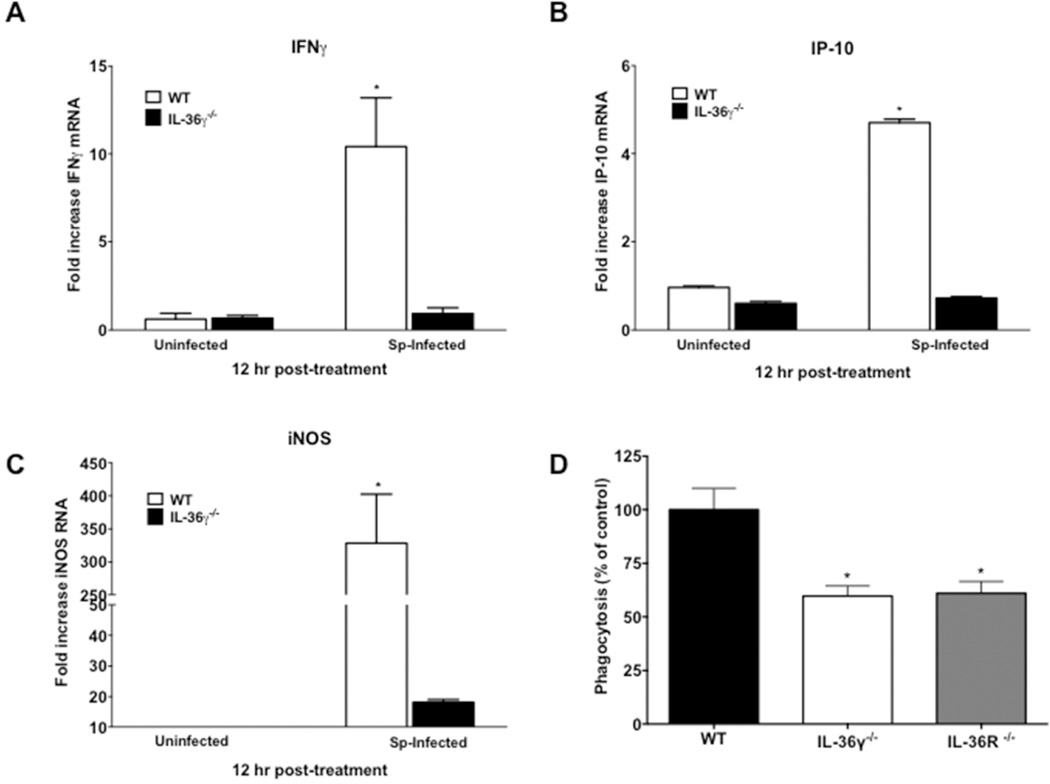

Reduced ex-vivo M1 macrophage activation in infected IL-36 γ−/− mice

Having observed no differences in leukocyte influx or antimicrobial peptide expression, we next determined whether IL-36γ influenced skewing of macrophage activation states. WT and IL-36γ−/− mice were infected with i.t. Sp (8×104 CFU) and PM were isolated 12 hours after infection. This population of cells has been determined to be >95% macrophages based on F4/80hi staining. There were no baseline differences in M1 activation markers in PM from uninfected WT and mutant mice. AT 12 hours, ex-vivo WT PM demonstrated significantly increased induction of the classical M1 markers IFNγ, IP-10/CXCL10, and iNOS (Figure 6A–C). Conversely, there was minimal induction of IFNγ, IP-10, and iNOS in IL-36γ−/− PM ex-vivo. There were no significant differences in the expression of alternative activation (M2) markers, Ym1 or arginase 1 (data not shown).

Fig. 6. Effect of IL-36γ on ex-vivo macrophage expression of activation state markers.

(A–C) WT and IL-36γ−/− mice were treated with i.t. Sp or vehicle. 12 hours after infection, interstitial and alveolar macrophages were isolated. Cytokine induction was measured by RT-PCR. (*p < 0.0001 as compared to uninfected WT by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, n = 3 per group, representative of 2 experiments). (D) Pulmonary macrophages from WT, IL-36γ−/−, and IL-36R−/− mice were isolated and incubated in-vitro with FITC-labeled Sp (MOI 10:1). Intracellular fluorescence was measured at 2 hours after stimulation. Phagocytosis is expressed as a percent of total fluorescence as compared to WT animals. (*p < 0.01 as compared to WT by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, n = 6 per group, representative of 2 experiments).

We next assessed whether IL-36γ influences constitutive phagocytic function of macrophages. Bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDM) were isolated from uninfected WT, IL-36γ−/− and IL-36R−/− mice and incubated with FITC-labeled Sp (Figure 6D). Both IL-36γ−/− and IL-36R−/− macrophages demonstrated significantly reduced phagocytosis as compared with WT BMDM.

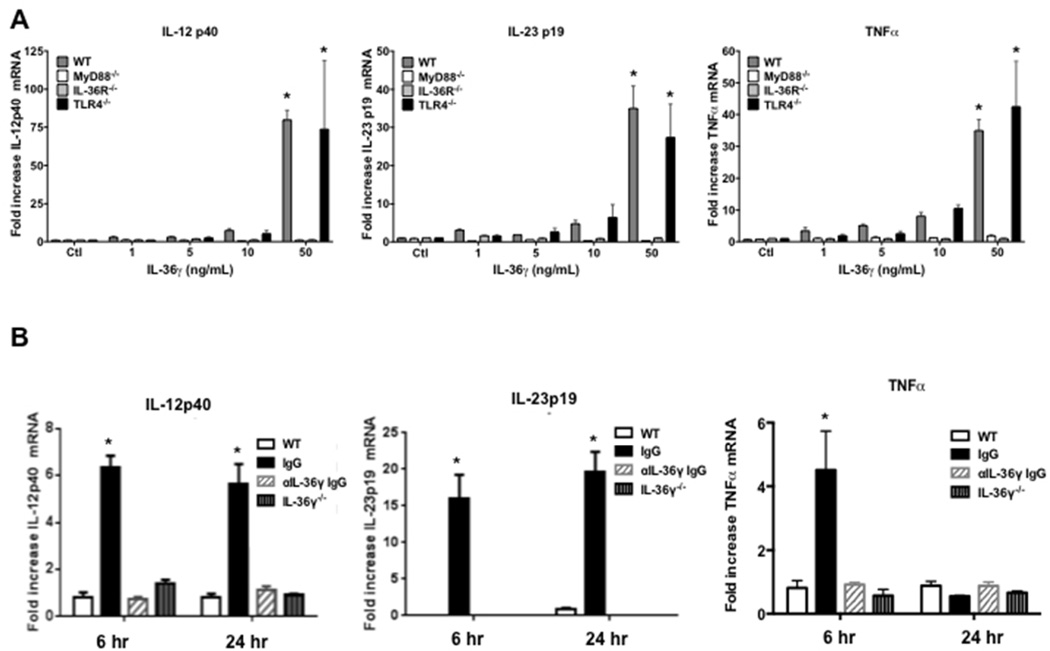

IL-36γ induces type-1 cytokines from dendritic cells in a MyD88-dependent fashion

DC promote the development of protective type-1 and IL-17 immune responses by elaboration of cytokines (5, 6). Additionally, DC highly express IL-36R (28). We therefore examined whether IL-36γ could directly induce type-1 cytokines from BMDC in-vitro. IL-36R contains an intracellular TIR domain similar to IL-1R and most toll-like receptors (TLR). Hence it has been speculated, but not proven, that IL-36R signaling is MyD88-dependent (17). To establish direct stimulatory effects and requirement for MyD88, murine BMDC were isolated from WT and MyD88−/− mice and treated with various doses of recombinant murine IL-36γ (Figure 7A). We observed a dose-dependent increase in IL-12p40, IL-23p19, and TNFα mRNA in response to IL-36γ in WT BMDC, with significant cytokine induction observed at doses as low as 5 ng/mL. Induction of all cytokines was nearly completely mitigated in MyD88−/− BMDC. Cytokine induction in response to IL-36γ was also impaired in IL-36R−/− BMDC, but not TLR4−/− BMDC, confirming that the effect is IL-36R-specific and not due to endotoxin contamination.

Fig. 7. Effect of IL-36γ on dendritic cells expression of type 1 and IL-17 cytokines.

(A) BMDC isolated from WT, MyD88−/−, IL-36R−/−, and TLR4−/− mice were stimulated with increasing concentrations of recombinant IL-36γ. Cytokine secretion was measured by ELISA at 6 hrs. (*p < 0.001 as compared to WT control by two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, n = 4 per group, representative of 2 experiments) (B) BMDC were isolated from WT mice were co-cultured with either no MP (WT), MP isolated from WT PM treated with a control (IgG) or an anti-IL-36γ IgG (αIL-36γ IgG), or MP isolated from IL-36γ−/− PM. Cytokines were measured by ELISA at 6 and 24 hrs. (* p < 0.01 compared to WT at the same time point by two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, n = 4–5 per group, representative of 2 experiments)

We have shown that activated PM secrete IL-36γ within microparticles and exosomes in-vitro (35). Having demonstrated that DC are a cellular target for IL-36γ, we next determined if PM might network with DC via paracrine release of IL-36γ. To explore this, MP were isolated from ATP-treated WT PM (to stimulate maximal MP secretion), then incubated with BMDC (approximately 10:1 MP to cell ratio) in the presence of either control or anti-IL-36γ antibody. MP from IL-36γ−/− PM served as an additional control. The number of microparticles per condition was determined to be 2–3×107 by flow cytometry, and did not differ significantly between WT and IL-36γ−/− groups. BMDC mRNA was isolated at 6 and 24 hours post-incubation (Figure 7B). In resting BMDC, there was minimal expression of cytokines, whereas BMDC incubated with WT macrophage MP in the presence of control IgG expressed significant levels of TNFα mRNA at 6 hrs, and IL-12p40 and IL-23p19 mRNA at 6 and 24 hours. In contrast, cytokine induction was markedly abrogated in BMDC incubated with MP treated with anti-IL-36γ Ab or MP from IL-36γ−/− PM. No significant cytokine induction was observed from MyD88−/− BMDC treated with WT macrophage-derived MP (data not shown).

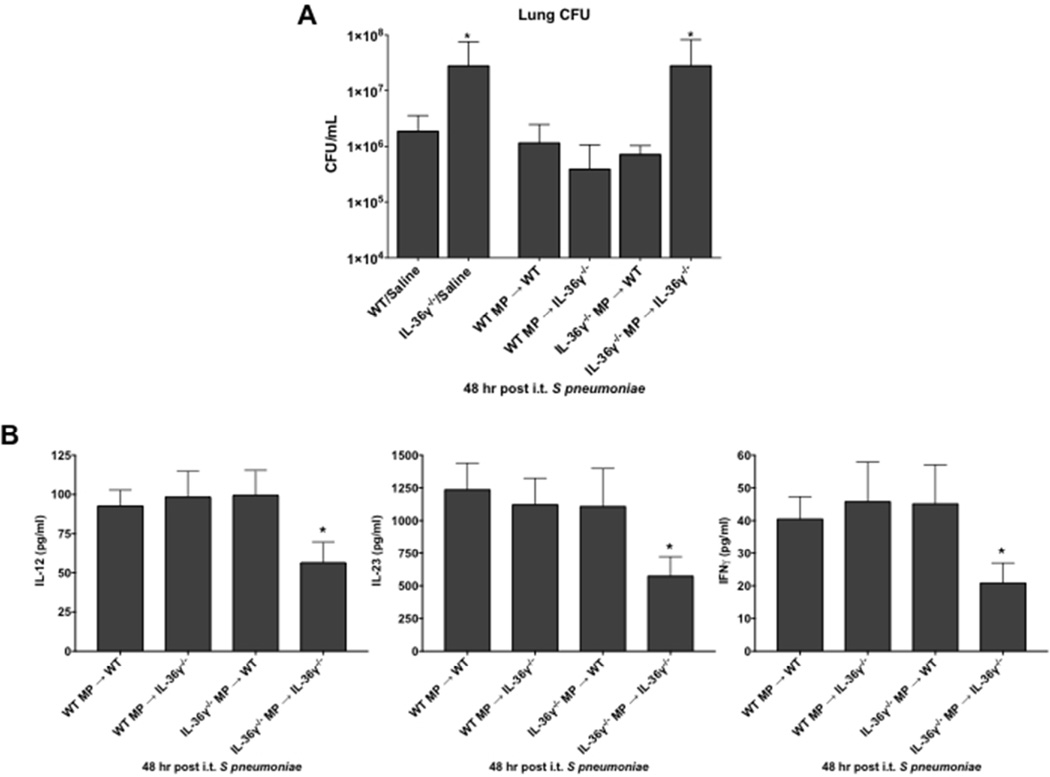

Lung macrophage-derived microparticles restore antibacterial immunity in IL-36γ−/− mice

To determine if macrophage-derived MP could restore antibacterial immunity in IL-36γ-deficient mice, WT and IL-36γ−/− mice were challenged with i.t. Sp concomitant with cell-free MP isolated from either WT or IL-36γ−/− macrophages (2–3×107 MP per condition, Figure 8A). As previously observed, IL-36γ−/− mice administered vehicle control had impaired lung bacterial clearance as compared to WT, vehicle-treated animals (p < 0.001). MP isolated from either WT or IL-36γ−/− PM did not alter lung Sp CFU in WT mice. However, administration of MP from WT PM significantly reduced lung Sp CFU in IL-36γ−/− mice, whereas no improvement in lung bacterial clearance was observed in IL-36γ−/− mice administered MP derived from IL-36γ−/− PM.

Fig. 8. Effect of IL-36γ-containing microparticles on lung bacterial clearance.

(A) WT or IL-36γ−/− were treated with either vehicle or MP derived from PM of either WT or IL-36γ−/− mice as specified, and then infected with i.t. Sp. Lung CFU were assessed by serial dilution at 48 hrs after infection. (*p < 0.001 compared to WT/vehicle by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, n = 5 mice/group, representative of 2 experiments). (B) WT or IL-36γ−/− were treated with MP derived from PM of either WT or IL-36γ−/− mice as specified, and then infected with i.t. Sp. IL-12p40, IL-23p19, and IFNγ were assessed by serial dilution at 48 hrs after infection. (*p < 0.001 compared to WT/vehicle by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, n = 5 mice/group, representative of 2 experiments).

In addition to the improvement in lung bacterial clearance, administration of IL-36γ-containing MP also restored deficits in type-1 cytokine expression in IL-36γ−/− mice in-vivo. WT and IL-36γ−/− mice were injected with either WT or IL-36γ−/− MP and Sp in the manner described above, and lungs were removed 48 hours after infection. Cytokine concentrations were determined from whole lung homogenates by ELISA (Figure 8B). WT mice expressed similar levels of cytokines, regardless of whether they received WT or IL-36γ−/− MP. IL-36γ−/− mice that received IL-36γ−/− MP expressed significantly lower concentrations of IL-12p70, IL-23, and IFNγ protein. However, cytokine expression in IL-36γ−/− mice that received WT MP was restored to similar levels as that observed in WT mice.

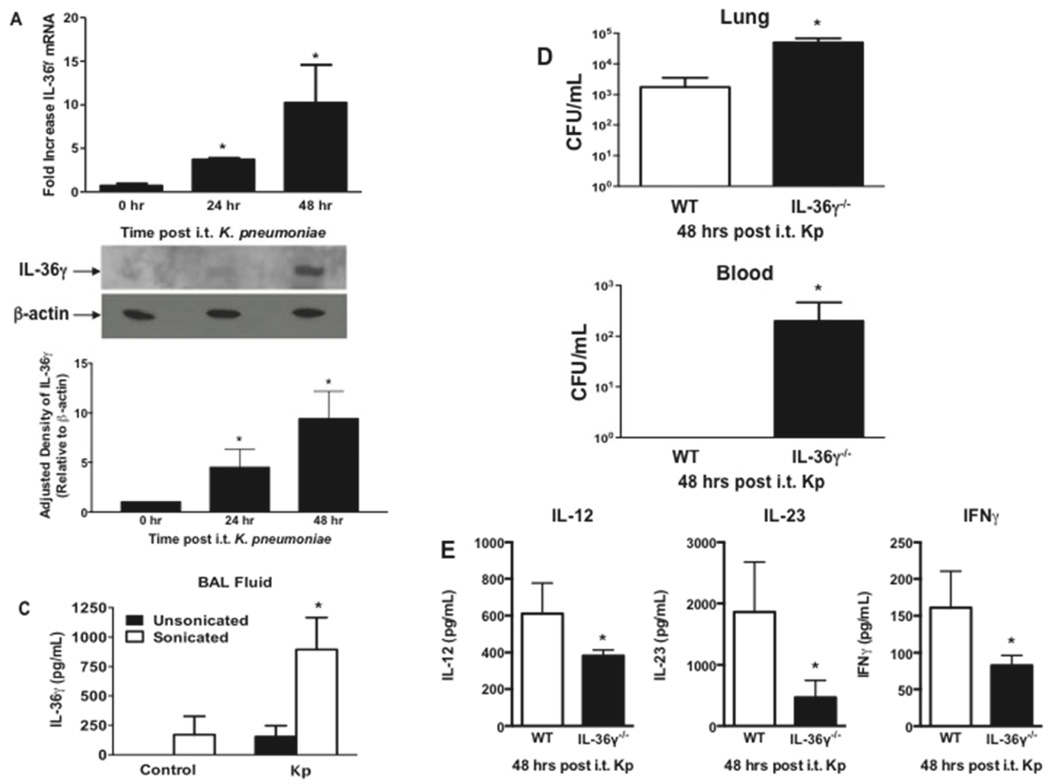

IL-36γ contributes to protective lung immunity against the Gram-negative pathogen Klebsiella pneumoniae

Type-1 cytokines are required for effective innate immunity against certain Gram-negative pathogens, including Klebsiella pneumoniae (Kp) (3,7–9). We therefore examined the induction and biologic effects of IL-36γ during experimental murine Kp pneumonia (Figure 9). As with Sp, i.t. administration of Kp (5–8×103 CFU) induced IL-36γ mRNA (Figure 9A), albeit delayed relative to Sp, with IL-36γ expression peaking at 48 hours post infectious challenge (Figure 9B). Although some IL-36γ protein was detectable in unsonicated BALF 18 hours after Kp infection, detection of IL-36γ protein was substantially enhanced by sonication of cell-free BALF (Figure 9C). Additionally, IL-36γ−/− mice demonstrated impaired lung bacterial clearance and increased dissemination compared to WT (Figure 9D). Similar effects were observed in anti-IL-36γ antibody treated mice (data not shown). Lastly, BALF of IL-36γ−/− mice contained significantly less IL-12, IL-23, and IFNγ 48 hours post Kp administration, as compared to WT mice (Figure 9E).

Fig. 9. Effect of IL-36γ on innate immune response to K. pneumoniae.

WT mice were infected with i.t. Kp and lungs were harvested at the specified time points. (A) mRNA was assessed by RT-PCR (*p < 0.05 compared to uninfected controls by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, n = 4 mice/group, representative of 3 experiments). (B) IL-36γ protein was detected by Western immunoblotting at 48 hrs after infection. Blot is representative of 3 mice/time point, and of 2 separate experiments. Densitometry represents relative density compared to β-actin from all replicates pooled from both experiments. (*p < 0.05 compared with uninfected mice by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test). (C) WT mice infected with Kp underwent BAL at 48 hrs after infection. BAL fluid was analyzed for IL-36γ protein by ELISA either with or without sonication. (*p < 0.05 compared to unsonicated control by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, n = 4–5 mice/group, representative of 2 experiments) (D) Lung and spleen CFU were assessed by serial dilution at 48 hrs after infection. (*p < 0.05 compared to WT by student’s t test, n = 8 mice/group, combined from 2 experiments) (E) BALF of WT and IL-36γ−/− mice was analyzed for cytokine concentration by ELISA 48 hrs after infection (*p < 0.05 compared to WT by student’s t test, n = 4 mice/group, representative of 2 experiments).

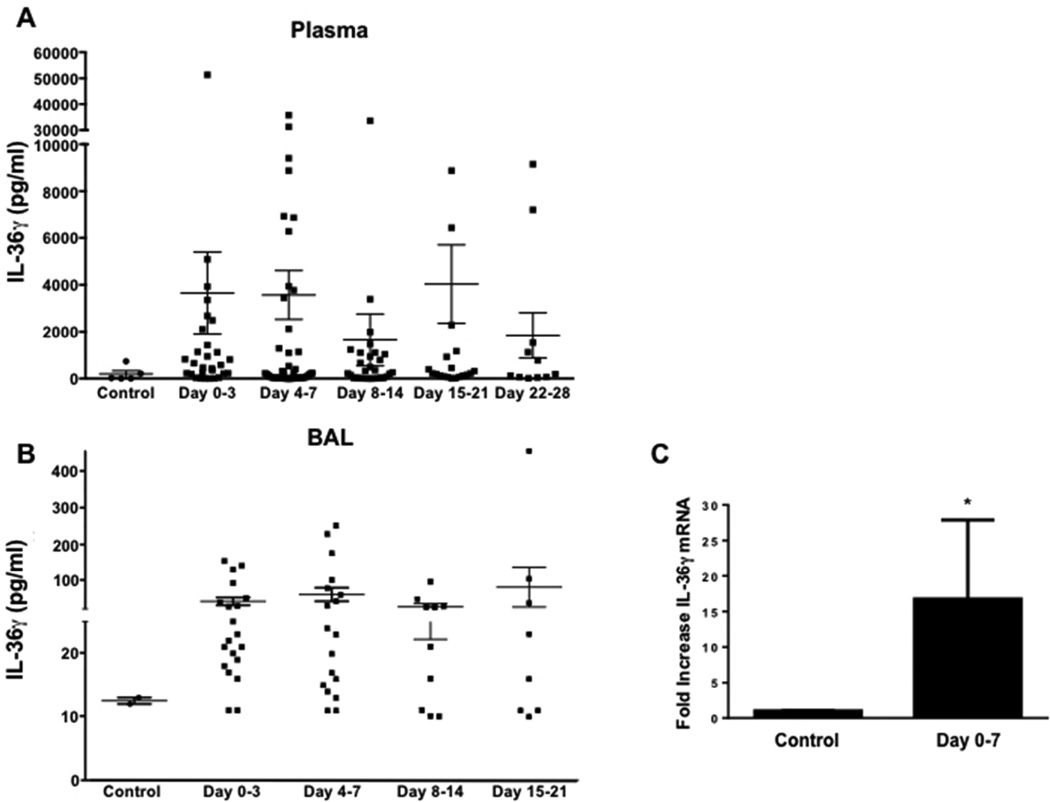

IL-36γ is expressed in lung and systemically during bacterial pneumonia-induced ARDS

To explore the relevance of our findings to human disease, we examined plasma and BALF from patients with ARDS due to bacterial pneumonia for the presence of human IL-36γ protein by ELISA (Figure 10). Plasma and BALF were sonicated to disrupt microparticles and therefore maximize IL-36γ detection. As compared to plasma and BALF from healthy controls, IL-36γ levels were significantly increased in both plasma (Figure 10A) and BALF (Figure 10B) of pneumonia patients as early as day 0–3 after onset of ARDS. Increased plasma levels persisted as long as 28 days after ARDS onset, whereas BALF IL-36γ levels were elevated up to 3 weeks. Additionally, we measured the IL-36γ mRNA expression in adherence-purified alveolar macrophages (AM) collected from a subset of pneumonia-induced ARDS patients (n = 7) within 3 days of ARDS onset (Figure 10C). As compared to AM from healthy control subjects, there was an approximately 15-fold increase of IL-36γ mRNA levels in AM of ARDS patients (p < 0.05).

Fig. 10. Effect of ARDS on IL-36γ induction in humans.

IL-36γ protein was assessed in both plasma (A) and BALF (B) of humans with ARDS due to bacterial pneumonia compared to health control subjects. (p < 0.05 compared to control by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, n = 8–40 patients/time point). (C) Alveolar macrophages were isolated from 7 patients within the first week of onset of ARDS and analyzed for IL-36γ mRNA. (*p < 0.05 compared to control by student’s t test, n = 5 – 7 patients/group).

Discussion

Our understanding of the role of IL-36 family members in innate immune responses is limited. Increasing evidence supports the importance of IL-36 in inflammatory disorders, such as psoriasis, where IL-36 induces Th17 cytokines, chemokines, AMPs, and other inflammatory cytokines (24–27). Considerably less is known about the effects of IL-36 in the lung. The i.t. instillation of recombinant IL-36γ and -α triggered production of inflammatory cytokines and alveolar neutrophilic influx in-vivo, although doses administered were almost certainly supra-physiologic (31,32). Relevant to infection, incubation of PBMC with Aspergillus fumigatus in-vitro induced IL-36γ, and blockade of IL-36Ra enhanced IFNγ and IL-17 production (29). In this study, we demonstrated that IL-36γ is selectively produced in the lung in response to i.t. Sp infection (Figure 1). Induction begins early during infection, with peak mRNA levels observed as early as 4 hours after inoculation, and protein by 24hrs. We have also shown that IL-36γ is induced in response to the Gram-negative bacteria, Kp, although somewhat delayed relative to Sp infection. The reason for this delay is unclear, but may be related to the higher inoculum of Sp (approximately 10-fold greater) as compared to that of Kp.

We previously demonstrated that IL-36γ is induced in PM and secreted in a non-classical fashion packaged within microparticles and exosomes (35). Herein, we have demonstrated that IL-36γ is secreted into BALF of infected mice (Figure 1C) and humans (Figure 10B). Detection of IL-36γ protein was greatly enhanced by sonication, supporting the notion that IL-36γ is released into the alveolar space within membrane-bound vesicles. Flow cytometry confirmed the presence of intact MP (Figure 1D), and Western blotting revealed IL-36γ protein within the MP fraction of cell-free BALF (Figure 1E). Collectively, our in-vivo findings support our novel in-vitro studies, which indicate that IL-36γ is secreted into the alveoli within MP in-vivo in response to bacterial infection. This is in line with previous reports that IL-36 agonists lack a leader sequence and secretion is enhanced by purinergic receptor activation, which stimulates non-classical secretion of proteins by promoting MP formation at the plasma membrane (36–39).

IL-36γ deficiency, either by genetic deletion or by antibody neutralization, resulted in significantly increased mortality during Sp pneumonia (Figure 2). This was almost certainly attributable to marked impairment in lung bacterial clearance and enhanced bacterial dissemination in the absence of IL-36γ (Figure 3). Similarly, IL-36γ deficiency impaired lung bacterial clearance during Kp pneumonia (Figure 9). Mortality in our studies was somewhat delayed relative to the finding of impaired bacterial clearance by 48 hours after Sp challenge. This discrepancy is likely due, in part, to the decreased CFU inoculum used in mortality studies relative to other experiments. However, it is also known that mortality in pneumococcal pneumonia is not merely the result of lung bacterial burden and respiratory compromise, but is also due to complications of bacteremia such as sepsis and multiple organ failure (40–42). Mortality due to these complications would therefore be predicted to occur after the establishment of significant bacteremia. Indeed, our findings are compatible with reports of the natural history of pneumococcal pneumonia in the pre-antibiotic era, which reported the highest mortality occurring between the seventh and ninth days after the onset of infection (43).

Type-1 and IL-17 cytokines are required for effective lung mucosal immunity against Sp (1, 5, 6) and Kp (3, 4, 7–9). These cytokines stimulate alveolar leukocyte recruitment, macrophage and neutrophil effector responses, and induce AMP expression (11–14). DC promote the development of protective type-1 and IL-17 immune responses via elaboration of TNFα, IL-12 and IL-23 (5, 6). Importantly, IL-36γ directly induces these cytokines from BMDC in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 7). Furthermore, MP from WT macrophages induces type-1 and IL-17 cytokines in BMDC in-vitro in an IL-36γ-dependent manner, raising the possibility that PM may network with DC to drive proximal cytokine production via paracrine expression of IL-36γ. Type-1 and IL-17-cytokine induction was diminished in IL-36γ−/− mice, as compared to WT animals in response to either Sp or Kp infection. In Sp-infected IL-36γ−/− mice, there were early impairments in TNFα and IP-10/CXCL10 induction (Figure 4), whereas reduction in the expression of IL-23p19, IL-12p40, IFNγ, and IL-17 were delayed 24 to 48 hours post infection.

IL-17 is associated with various pro-inflammatory immune effects, including leukocyte recruitment (44). However, in this model impairment in bacterial clearance was not attributable to deficits in either monocyte/macrophage or PMN influx into the airspace or interstitium (Figure 5). In fact, there was a modest, but statistically insignificant, increase in BAL and whole lung neutrophils in IL-36γ-deficient mice at 48 hours, likely reflecting increased bacterial burden at that time point. This suggests that IL-36γ-dependent IL-17 induction is less impactful than effects on type-1 cytokines in this model. Effects on bacterial clearance were not attributable to direct antimicrobial properties of IL-36, as IL-36γ at doses as high as 100 ng/ml did not exert direct bactericidal activity against either Sp or Kp, nor did IL-36γ induce AMPs from PM, BMDC, or alveolar epithelial cells in-vitro or in lung in-vivo (Supplemental Fig 1).

We have observed that IL-36γ induces type-1 cytokines during bacterial pneumonia, notably IFNγ. IFNγ is responsible for a variety of immune functions, including M1 polarization of macrophages (45). Classically-activated macrophages participate in key pro-inflammatory responses, enhanced antigen presentation, and pathogen clearance. Our studies indicate that IL-36γ is required for IFNγ and iNOS induction in PM in-vivo during pneumonia (Figure 6), which suggests that IL-36γ promotes effective M1 activation during infection. Moreover, BMDM phagocytic function is significantly reduced in-vitro in IL-36γ−/− or IL-36R−/− macrophages (Figure 6D). This suggests that IL-36γ (and perhaps other IL-36 agonists) tonically regulate macrophage phagocytic function. The mechanism by which this occurs is uncertain, and is a focus of ongoing investigation. Collectively, our data suggests that impairment in bacterial clearance, and ultimately survival, in IL-36γ-deficient mice is due to diminished type-1 cytokine induction and, in turn, lack of effective M1 macrophage polarization, along with inherent defects in phagocytic activity.

As IL-36γ is primarily released from macrophages within MP, we attempted to restore mucosal immunity in Sp-infected IL-36γ−/− mice by administering MP directly into the lung. MP administration to infected WT mice did not significantly enhance lung bacterial clearance over vehicle alone (Figure 8A). However, administration of WT MP, but not IL-36γ−/− MP, substantially improved bacterial clearance in IL-36γ−/− mice. Additionally, WT MP, but not IL-36γ−/− MP, improved type-1 cytokine expression in IL-36γ−/− mice (Figure 8B). Thus, IL-36γ within lung macrophage-derived MP is uniquely responsible for restoring immunity in IL-36γ-deficient mice, to the exclusion of other bioactive proteins contained within the MP. This also suggests that MP delivery may be a viable therapeutic option to modulate pulmonary immune responses, similar to MP delivery being used to promote alveolar epithelial repair in an LPS-induced lung injury model (46). The exact mechanism(s) by which IL-36 signals when contained within MPs (via cell surface receptor mediated signaling, internalization, or transfer of genetic material) remains to be elucidated.

IL-36R, like IL-1R, IL-18R and most TLRs, contains an intracellular TIR domain leading to speculation that IL-36R signaling requires association with MyD88. In this study, we have established that IL-36γ-mediated cytokine induction is in fact MyD88-dependent (Figure 7A). This effect was specific for IL-36R signaling and not due to endotoxin contamination, as we observed loss of cytokine induction in BMDC isolated from IL-36R-deficient mice but unaltered cytokine expression in BMDC isolated from TLR4−/− mice (data not shown).

We also found considerable induction of IL-36γ in humans with pneumonia-induced ARDS (Figure 10). IL-36γ was elevated in both the alveolar space and in circulation, suggesting that IL-36γ not only plays a role in local immune responses to infection, but also the systemic inflammatory changes seen in ARDS. As with murine pneumonia, AM appear to be an important source of IL-36γ in pneumonia-induced ARDS. Of note, there was considerable patient-to-patient heterogeneity in IL-36γ levels, which is not unexpected based on the syndromic nature of ARDS and the fact that the population included a mix of patients with both Gram-positive and –negative infections. We have also observed elevated systemic and BAL levels of IL-36γ in ARDS subjects with sepsis due to infections other than pneumonia (data not shown). Thus it is unclear whether elevated BAL levels in these subjects were due to the systemic or local effects of bacterial infection, or a combination of the two. Moreover, in the context of concurrent acute lung injury, it is difficult to discern the precise contribution of infection to the expression pattern of IL-36 observed in these patients. The patient population was relatively small with a low mortality rate, so we were unable to correlate IL-36γ levels with mortality. We did not specifically assess whether IL-36γ was localized to MP or exosomes in the ARDS patients, as plasma and BAL samples were sonicated prior to ELISA. Interestingly, leukocyte-derived MPs have previously been reported in the BALF of ARDS patients and positively correlated with favorable clinical outcome in these patients (47).

Taken together, our findings demonstrate an essential role for IL-36γ in the lung in response to bacterial infection via induction of type-1 cytokine responses and M1 macrophage polarization. Currently, there is significant interest in the role of IL-36 family members in the pathogenesis of certain autoimmune diseases, especially psoriasis (16, 22, 24–27, 48–50) and therefore potential targets of immunomodulation. The present observations strongly suggest that IL-36γ deletion/inhibition may have adverse effects in the setting of infection, and has obvious implications to host defense mechanisms in other bacterial infections, as well as numerous respiratory pathogens that require vigorous protective type-1 responses, such as fungi and mycobacterium.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Specific pathogen-free (SPF) age-and sex-matched C57BL/6 mice (wild type, WT) and TLR4−/− mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). IL-36γ−/− mice on a C57BL/6 background were developed by the Mutant Mouse Regional Resource Center at University of California Davis (Davis, CA). IL-36R−/− mice on a C57BL/6 background were obtained from Amgen (Thousand Oaks, CA). These mice all displayed normal pulmonary development, were without obvious immune defects in the resting state and reproduced normally. All mice were housed in SPF conditions within the animal care facility (Unit for Laboratory Animal Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI) until the day of sacrifice.

Reagents

Carrier free recombinant mouse IL-36α and -γ was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN) for use with in-vitro stimulation, antibody generation, and as ELISA standards. For human IL-36γ ELISA generation, human recombinant IL-36γ and human anti-IL-36γ polyclonal antibody were also purchased from R&D Systems.

Bacterial Preparation

Klebsiella pneumoniae strain 43816, serotype 2 was grown overnight in trypticase soy broth (BD; Franklin Lakes, NJ) at 37°C. Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 3, 6303 (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) was grown to mid-log phase in Todd-Hewett broth, washed in PBS, and serially diluted in sterile saline. Bacterial concentration was determined by measuring absorbance at 600 nm, and plotting on a standard curve of known CFU values. The culture was then diluted to the desired concentration. Heat-killed bacteria were prepared by incubating cultures in a 65°C water bath for 45 minutes.

Generation of Rabbit Anti–Mouse Polyclonal IL-36-Specific Antibody

Anti-IL-36γ antibody was generated in New Zealand white rabbits immunized with recombinant mouse IL-36α –γ as previously described (51). The antibody was purified and titered by ELISA against IL-36γ coated onto 96-well plates. Purified IgG from non-immunized rabbits was used as a control.

Intratracheal inoculation

Mice were anesthetized with intraperitoneal (i.p.) ketamine and xylazine. Under sterile conditions, the trachea was exposed, and a 30 µl inoculum was administered via sterile 27-gauge needle. The skin incision was closed with surgical staples.

Whole lung, spleen, and blood CFU determination

At designated time points, mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation. The thoracic cavity was opened under sterile conditions. Whole blood was aspirated into heparinized syringes from the right ventricle, serially diluted 1:10 with sterile PBS, and plated on nutrient agar (BD; Franklin Lakes, NJ) to determine CFU. The pulmonary vasculature was perfused with 1 ml sterile PBS containing 5 mM EDTA via the right ventricle. Whole lungs and spleen were removed and homogenized separately in 1 ml PBS with protease inhibitor (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN). Homogenates were serially diluted 1:10 in PBS and plated.

Bronchoalveolar lavage

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed as previously described (12). Briefly, the trachea was exposed and intubated using 1.7-mm outer diameter polyethylene tubing. PBS containing 5mM EDTA was instilled into the trachea in three – 1 ml aliquots and aspirated by syringe suctioning. BALF was centrifuged at 1800 rpm at 4°C for 10 min. Supernatants were reserved for other experiments. Cell pellets were resuspended in 250 µl GIBCO® RPMI medium (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA). Cell counts and viability were determined using Trypan blue exclusion. Cytospin slides were prepared and stained with a modified Wright-Giemsa stain.

Murine Pulmonary Macrophage Isolation

Pulmonary macrophages (PM), including both alveolar and interstitial lung macrophages, were isolated from dispersed lung digest cells by adherence purification as previously described (52). Macrophage purity has been determined to be >95% by forward and side scatter characteristics and F4/80hi and CD11b staining.

In-vitro phagocytosis assay

Bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDM) were harvested from mice (C57BL/6; IL-36γ−/−; IL-36R−/−) and the ability of the BMDM from each mouse to phagocytize via opsonin-independent pathways was examined using a 300:1 ratio [FITC-labeled Sp]. Briefly, 2 × 105 BMDMs were plated on a half-area black 96-well plate and incubated with supplemented medium overnight at 37°C. The next day, the medium was changed to serum-free medium, and 10 µl FITC-labeled Sp was added to each well. After 2 h at 37°C, trypan blue was added to quench extracellular fluorescence, and phagocytosis was quantified by intracellular fluorescence as previously described (53).

Human ARDS Sample Preparation

Patients with ARDS enrolled in the Acute Lung Injury Specialized Center of Clinically Oriented Research (SCCOR) randomized trial of GM-CSF administration in patients with ARDS conducted at the University of Michigan between July 2004 and October 2007 were studied (54). ARDS was defined as acute onset of illness with: 1) PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 300; 2) bilateral infiltrates consistent with pulmonary edema on chest radiograph; 3) requirement for positive pressure ventilation via endotracheal tube; 4) no clinical evidence of left atrial hypertension; 5) if measured, pulmonary arterial wedge pressure ≤ 18 mmHg; and 6) the aforementioned criteria occurring together within a 24-hour interval. For this study, only patients with a clinical diagnosis of pneumonia from the observational or placebo arms of the trial were analyzed (n = 40). Subjects underwent serial bronchoscopy with BAL and peripheral blood collection after onset of ARDS. BAL alveolar macrophages (AM) were collected from seven ARDS patients (54,55). Serial blood and BAL samples were also collected from 5 healthy control subjects. Control subjects were <55-year-old lifelong non-smokers taking no medications. Demographic and clinical data are summarized in Supplemental Table 1.

Peripheral whole blood samples were collected in heparin-containing Vacutainer® tubes (Becton-Dickinson, Franklin, NJ, USA) and centrifuged (1500 rpm for 10 minutes at room temperature). Plasma was stored at −80°C. BALF obtained from control subjects and ARDS patients by bronchoscopy using standard technique (54,55) was centrifuged (1500 rpm at 4°C for 10 minutes). Cell-free supernatant was decanted and stored (−70°C). Cells were resuspended and plated in GIBCO® RPMI medium. After one hour, plates were washed with sterile PBS. Adherent macrophages were resuspended in Trizol® reagent and stored (−20°C). Cell differentials post adherence revealed >90% macrophages by morphology, and highly expressed both CD163 and CD14. mRNA expression of CD163 and CD14 by AM isolated from ARDS patients was not different than that from control patients (data not shown). BALF and plasma were sonicated (2 ×10 s output, 140 Hz) prior to use in ELISAs.

Microparticle Isolation

PM were cultured at a concentration of 5×106 cells per tissue culture plate. Following stimulation, conditioned media was collected and centrifuged at 1500 × g for 30 min at 4°C to remove cell debris and apoptotic bodies. The supernatant was stored at −80°C until further use up to a maximum of 2 weeks. Supernatants were thawed and ultracentrifuged at 25,000 × g for 30 minutes at 10°C (Beckman Coulter Life Sciences, Indianapolis, IN). Microparticle-containing pellets were resuspended in RPMI.

Murine ELISAs for cytokine measurement

Cell-free BALF supernatants were analyzed for indicated cytokines using mouse DuoSet ELISA kits (R&D Systems; Minneapolis, MN) per manufacturer’s protocol.

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR

Gene expression was assessed utilizing the ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystem; Foster City, CA) as previously described (52). Briefly, total cellular RNA from lungs was isolated, reversed transcribed into cDNA, and amplified using specific primers for indicated genes with β-actin serving as a control. Specific thermal cycling parameters used with the TaqMan One-Step RT-PCR Master Mix Reagents kit are as follows: 30 min at 48°C, 10 min at 95°C, and 40 cycles involving denaturation at 95°C for 15 s and annealing/extension at 60°C for 1 min. Relative quantitation of mRNA levels was plotted as fold-change compared with untreated control cells. Experiments were performed in duplicate.

Western immunoblotting

Cells or tissue were homogenized in RIPA buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Protein concentrations were determined by Bio-Rad DC protein assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories; Hercules, CA). Samples were electrophoresed in 4–12% gradient SDS-PAGE gels, transferred to nitrocellulose and blocked with 5% skim milk in PBS. After incubation with primary antibodies, blots were incubated with an HRP-conjugated secondary Ab and bands visualized using ECL (SuperSignal West Pico Substrate, Pierce Biotechnology; Rockford, IL).

Flow Cytometry

Microparticles isolated by ultracentrifugation were resuspended in 100 µL Annexin V Binding Buffer (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA), and stained with Annexin V-PE per the manufacturer’s protocol. Samples were counted on a MoFlo® Astrios (Beckman Coulter), and analyzed using FloJo flow cytometry analysis software (Ashland, OR). Calibrated microbeads were used to determine size of particles present.

Statistics

Statistical significance of all experiments was determined using a value of p ≤ 0.05 considered significant. Specific statistical testing, including post hoc testing where appropriate, is described in the accompanying figure legends. Error bars represent mean ± SEM. All calculations were performed using GraphPad Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Study Approval

Animal studies were reviewed and approved by the University Committee on the Use and Care of Animals (University of Michigan). Human studies employed protocols approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from participants or their legal proxy for medical decision making prior to study inclusion.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank David Adams in the University of Michigan Flow Cytometry Core for his assistance with cytometer set up and calibration.

Funding: This work was supported by NIH grants HL123515 (TJS), T32 HL007749, and K08 HL121089 (MAK).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Author Contributions: MAK conceived of the study with TJS, formulated the study design, performed experiments and data analysis, and wrote the manuscript. BS assisted with data analysis and figure preparation. GMC assisted with the in-vitro phagocytosis experiment. MWN and XZ performed experiments. TAM assisted with design of flow cytometry experiment and assisted with data analysis. PM cultured bacteria and assisted with experiments. SLK generated antibodies and assisted with experiments. MPG assisted with formulating study design. BBM assisted with formulating study design and data analysis. TJS conceived of the study with MAK, assisted with formulating study design and data analysis, and edited the manuscript.

References

- 1.Zhang Z, Clarke TB, Weiser JN. Cellular effectors mediating Th17-dependent clearance of pneumococcal colonization in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1899–1909. doi: 10.1172/JCI36731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhan U, Ballinger MN, Zeng X, Newstead MJ, Cornicelli MD, Standiford TJ. Cooperative interactions between TLR4 and TLR9 regulate interleukin 23 and 17 production in a murine model of gram negative bacterial pneumonia. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9896. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deng JC, Zeng X, Newstead M, Moore TA, Tsai WC, Thannickal VJ, Standiford TJ. STAT4 is a critical mediator of early innate immune responses against pulmonary Klebsiella infection. J Immunol. 2004;173:4075–4083. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.4075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zeng X, Moore TA, Newstead MW, Deng JC, Kunkel SL, Luster AD, Standiford TJ. Interferon-inducible protein 10, but not monokine induced by gamma interferon, promotes protective type 1 immunity in murine Klebsiella pneumoniae pneumonia. Infect Immun. 2005;73:8226–8236. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.12.8226-8236.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim BJ, Lee S, Berg RE, Simecka JW, Jones HP. Interleukin-23 (IL-23) deficiency disrupts Th17 and Th1-related defenses against Streptococcus pneumoniae infection. Cytokine. 2013;64:375–381. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2013.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ivanov S, Fontaine J, Paget C, Macho Fernandez E, Van Maele L, Renneson J, Maillet I, Wolf NM, Rial A, Leger H, et al. Key role for respiratory CD103(+) dendritic cells, IFN-gamma, and IL-17 in protection against Streptococcus pneumoniae infection in response to alpha-galactosylceramide. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:723–734. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore TA, Perry ML, Getsoian AG, Newstead MW, Standiford TJ. Divergent role of gamma interferon in a murine model of pulmonary versus systemic Klebsiella pneumoniae infection. Infect Immun. 2002;70:6310–6318. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.11.6310-6318.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoshida K, Matsumoto T, Tateda K, Uchida K, Tsujimoto S, Iwakurai Y, Yamaguchi K. Protection against pulmonary infection with Klebsiella pneumoniae in mice by interferon-gamma through activation of phagocytic cells and stimulation of production of other cytokines. J Med Microbiol. 2001;50:959–964. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-50-11-959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ye P, Rodriguez FH, Kanaly S, Stocking KL, Schurr J, Schwarzenberger P, Oliver P, Huang W, Zhang P, Zhang J, et al. Requirement of interleukin 17 receptor signaling for lung CXC chemokine and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor expression, neutrophil recruitment, and host defense. J Exp Med. 2001;194:519–527. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.4.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Happel KI, Dubin PJ, Zheng M, Ghilardi N, Lockhart C, Quinton LJ, Odden AR, Shellito JE, Bagby GJ, Nelson S, et al. Divergent roles of IL-23 and IL-12 in host defense against Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Exp Med. 2005;202:761–769. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cua DJ, Tato CM. Innate IL-17-producing cells: the sentinels of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:479–489. doi: 10.1038/nri2800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kovach MA, Ballinger MN, Newstead MW, Zeng X, Bhan U, Yu FS, Moore BB, Gallo RL, Standiford TJ. Cathelicidin-related antimicrobial peptide is required for effective lung mucosal immunity in Gram-negative bacterial pneumonia. J Immunol. 2012;189:304–311. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu FS, Cornicelli MD, Kovach MA, Newstead MW, Zeng X, Kumar A, Gao N, Yoon SG, Gallo RL, Standiford TJ. Flagellin stimulates protective lung mucosal immunity: role of cathelicidin-related antimicrobial peptide. J Immunol. 2010;185:1142–1149. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakamatsu M, Yamamoto N, Hatta M, Nakasone C, Kinjo T, Miyagi K, Uezu K, Nakamura K, Nakayama T, Taniguchi M, et al. Role of interferon-gamma in Valpha14+ natural killer T cell-mediated host defense against Streptococcus pneumoniae infection in murine lungs. Microbes Infect. 2007;9:364–374. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sims JE, Smith DE. The IL-1 family: regulators of immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:89–102. doi: 10.1038/nri2691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Towne JE, Sims JE. IL-36 in psoriasis. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2012;12:486–490. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Towne JE, Garka KE, Renshaw BR, Virca GD, Sims JE. Interleukin (IL) 1F6, IL-1F8, and IL-1F9 signal through IL-1Rrp2 and IL-1RAcP to activate the pathway leading to NF-kappaB and MAPKs. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:13677–13688. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400117200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Debets R, Timans JC, Homey B, Zurawski S, Sana TR, Lo S, Wagner J, Edwards G, Clifford T, Menon S, et al. Two novel IL-1 family members, IL-1 delta and IL-1 epsilon, function as an antagonist and agonist of NF-kappa B activation through the orphan IL-1 receptor-related protein 2. J Immunol. 2001;167:1440–1446. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van de Veerdonk FL, Stoeckman AK, Wu G, Boeckermann AN, Azam T, Netea MG, Joosten LA, van der Meer JW, Hao R, Kalabokis V, et al. IL-38 binds to the IL-36 receptor and has biological effects on immune cells similar to IL-36 receptor antagonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:3001–3005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121534109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunn E, Sims JE, Nicklin MJ, O'Neill LA. Annotating genes with potential roles in the immune system: six new members of the IL-1 family. Trends Immunol. 2001;22:533–536. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)02034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bachmann M, Scheiermann P, Hardle L, Pfeilschifter J, Muhl H. IL-36gamma/IL-1F9, an Innate T-bet Target in Myeloid Cells. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:41684–41696. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.385443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blumberg H, Dinh H, Trueblood ES, Pretorius J, Kugler D, Weng N, Kanaly ST, Towne JE, Willis CR, Kuechle MK, et al. Opposing activities of two novel members of the IL-1 ligand family regulate skin inflammation. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2603–2614. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blumberg H, Dinh H, Dean C, Jr, Trueblood ES, Bailey K, Shows D, Bhagavathula N, Aslam MN, Varani J, Towne JE, et al. IL-1RL2 and its ligands contribute to the cytokine network in psoriasis. J Immunol. 2010;185:4354–4362. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnston A, Xing X, Guzman AM, Riblett M, Loyd CM, Ward NL, Wohn C, Prens EP, Wang F, Maier LE, et al. IL-1F5, -F6, -F8, and -F9: a novel IL-1 family signaling system that is active in psoriasis and promotes keratinocyte antimicrobial peptide expression. J Immunol. 2011;186:2613–2622. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carrier Y, Ma HL, Ramon HE, Napierata L, Small C, O'Toole M, Young DA, Fouser LA, Nickerson-Nutter C, Collins M, et al. Inter-regulation of Th17 cytokines and the IL-36 cytokines in vitro and in vivo: implications in psoriasis pathogenesis. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:2428–2437. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muhr P, Zeitvogel J, Heitland I, Werfel T, Wittmann M. Expression of interleukin (IL)-1 family members upon stimulation with IL-17 differs in keratinocytes derived from patients with psoriasis and healthy donors. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:189–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nguyen TT, Niyonsaba F, Ushio H, Akiyama T, Kiatsurayanon C, Smithrithee R, Ikeda S, Okumura K, Ogawa H. Interleukin-36 cytokines enhance the production of host defense peptides psoriasin and LL-37 by human keratinocytes through activation of MAPKs and NF-kappaB. J Dermatol Sci. 2012;68:63–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vigne S, Palmer G, Lamacchia C, Martin P, Talabot-Ayer D, Rodriguez E, Ronchi F, Sallusto F, Dinh H, Sims JE, et al. IL-36R ligands are potent regulators of dendritic and T cells. Blood. 2011;118:5813–5823. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-05-356873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gresnigt MS, Rosler B, Jacobs CW, Becker KL, Joosten LA, van der Meer JW, Netea MG, Dinarello CA, van de Veerdonk FL. The IL-36 receptor pathway regulates Aspergillus fumigatus-induced Th1 and Th17 responses. Eur J Immunol. 2013;43:416–426. doi: 10.1002/eji.201242711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bochkov YA, Hanson KM, Keles S, Brockman-Schneider RA, Jarjour NN, Gern JE. Rhinovirus-induced modulation of gene expression in bronchial epithelial cells from subjects with asthma. Mucosal Immunol. 2010;3:69–80. doi: 10.1038/mi.2009.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramadas RA, Ewart SL, Medoff BD, LeVine AM. Interleukin-1 family member 9 stimulates chemokine production and neutrophil influx in mouse lungs. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;44:134–145. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0315OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramadas RA, Ewart SL, Iwakura Y, Medoff BD, LeVine AM. IL-36alpha exerts pro-inflammatory effects in the lungs of mice. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45784. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vos JB, van Sterkenburg MA, Rabe KF, Schalkwijk J, Hiemstra PS, Datson NA. Transcriptional response of bronchial epithelial cells to Pseudomonas aeruginosa: identification of early mediators of host defense. Physiol Genomics. 2005;21:324–336. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00289.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chustz RT, Nagarkar DR, Poposki JA, Favoreto S, Jr, Avila PC, Schleimer RP, Kato A. Regulation and function of the IL-1 family cytokine IL-1F9 in human bronchial epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;45:145–153. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0075OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kovach MA, Singer BH, Newstead MW, Zeng X, Moore TA, White ES, Kunkel SL, Peters-Golden M, Standiford TJ. IL-36γ is Secreted in Microparticles and Exosomes By Lung Macrophages in Response to Bacteria and Bacterial Components. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2016 doi: 10.1189/jlb.4A0315-087R. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kumar S, McDonnell PC, Lehr R, Tierney L, Tzimas MN, Griswold DE, Capper EA, Tal-Singer R, Wells GI, Doyle ML, et al. Identification and initial characterization of four novel members of the interleukin-1 family. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:10308–10314. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.14.10308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith DE, Renshaw BR, Ketchem RR, Kubin M, Garka KE, Sims JE. Four new members expand the interleukin-1 superfamily. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:1169–1175. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.2.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perregaux D, Gabel CA. Interleukin-1 beta maturation and release in response to ATP and nigericin. Evidence that potassium depletion mediated by these agents is a necessary and common feature of their activity. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:15195–15203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferrari D, Chiozzi P, Falzoni S, Dal Susino M, Melchiorri L, Baricordi OR, Di Virgilio F. Extracellular ATP triggers IL-1 beta release by activating the purinergic P2Z receptor of human macrophages. J Immunol. 1997;159:1451–1458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cilloniz C, Torres A. Understanding mortality in bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia. J Bras Pneumol. 2012;38:419–421. doi: 10.1590/s1806-37132012000400002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Amaro R, Liapikou A, Cilloniz C, Gabarrus A, Marco F, Sellares J, Polverino E, Garau J, Ferrer M, Musher DM, et al. Predictive and prognostic factors in patients with blood-culture-positive community-acquired pneumococcal pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2016;48:797–807. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00039-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Musher DM, Alexandraki I, Graviss EA, Yanbeiy N, Eid A, Inderias LA, Phan HM, Solomon E. Bacteremic and nonbacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia. A prospective study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2000;79:210–221. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200007000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tilghman R, Finland M. Clinical Significance of Bacteremia in Pneumoccocic Pneumonia. Arch Intern Med (Chic) 1937;59:602–619. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yuan S, Zhang S, Zhuang Y, Zhang H, Bai J, Hou Q. Interleukin-17 Stimulates STAT3-Mediated Endothelial Cell Activation for Neutrophil Recruitment. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;36:2340–2356. doi: 10.1159/000430197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Canton J, Neculai D, Grinstein S. Scavenger receptors in homeostasis and immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:621–634. doi: 10.1038/nri3515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhu YG, Feng XM, Abbott J, Fang XH, Hao Q, Monsel A, Qu JM, Matthay MA, Lee JW. Human mesenchymal stem cell microvesicles for treatment of Escherichia coli endotoxin-induced acute lung injury in mice. Stem Cells. 2014;32:116–125. doi: 10.1002/stem.1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guervilly C, Lacroix R, Forel JM, Roch A, Camoin-Jau L, Papazian L, Dignat-George F. High levels of circulating leukocyte microparticles are associated with better outcome in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care. 2011;15:R31. doi: 10.1186/cc9978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marrakchi S, Guigue P, Renshaw BR, Puel A, Pei XY, Fraitag S, Zribi J, Bal E, Cluzeau C, Chrabieh M, et al. Interleukin-36-receptor antagonist deficiency and generalized pustular psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:620–628. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Onoufriadis A, Simpson MA, Pink AE, Di Meglio P, Smith CH, Pullabhatla V, Knight J, Spain SL, Nestle FO, Burden AD, et al. Mutations in IL36RN/IL1F5 are associated with the severe episodic inflammatory skin disease known as generalized pustular psoriasis. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89:432–437. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tortola L, Rosenwald E, Abel B, Blumberg H, Schafer M, Coyle AJ, Renauld JC, Werner S, Kisielow J, Kopf M. Psoriasiform dermatitis is driven by IL-36-mediated DC-keratinocyte crosstalk. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:3965–3976. doi: 10.1172/JCI63451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Evanoff HL, Burdick MD, Moore SA, Kunkel SL, Strieter RM. A sensitive ELISA for the detection of human monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) Immunol Invest. 1992;21:39–45. doi: 10.3109/08820139209069361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Deng JC, Cheng G, Newstead MW, Zeng X, Kobayashi K, Flavell RA, Standiford TJ. Sepsis-induced suppression of lung innate immunity is mediated by IRAK-M. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2532–2542. doi: 10.1172/JCI28054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aronoff DM, Canetti C, Peters-Golden M. Prostaglandin E2 inhibits alveolar macrophage phagocytosis through an E-prostanoid 2 receptor-mediated increase in intracellular cyclic AMP. J Immunol. 2004;173:559–565. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.1.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Paine R, 3rd, Standiford TJ, Dechert RE, Moss M, Martin GS, Rosenberg AL, Thannickal VJ, Burnham EL, Brown MB, Hyzy RC. A randomized trial of recombinant human granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor for patients with acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:90–97. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31822d7bf0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Evans CR, Karnovsky A, Kovach MA, Standiford TJ, Burant CF, Stringer KA. Untargeted LC-MS metabolomics of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid differentiates acute respiratory distress syndrome from health. J Proteome Res. 2014;13:640–649. doi: 10.1021/pr4007624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.