Abstract

A diagnosis of childhood cancer is a life-changing event for the entire family. Parents must not only deal with the cancer diagnosis but also acquire new knowledge and skills to safely care for their child at home. Best practices for delivery of patient/family education after a new diagnosis of childhood cancer are currently unknown. The purpose of this systematic review was to evaluate the existing body of evidence to determine the current state of knowledge regarding the delivery of education to newly diagnosed pediatric oncology patients and families. Eighty-three articles regarding educational methods, content, influencing factors, and interventions for newly diagnosed pediatric patients with cancer or other chronic illnesses were systematically identified, summarized, and appraised according to the GRADE criteria. Based on the evidence, ten recommendations for practice were identified. These recommendations address delivery methods, content, influencing factors, and educational interventions for parents and siblings. Transferring these recommendations into practice may enhance the quality of education delivered by healthcare providers, and received by patients and families following a new diagnosis of childhood cancer.

Keywords: education, pediatric oncology, family, new diagnosis, systematic review

A diagnosis of childhood cancer is a life-changing event for the entire family. The cancer diagnosis makes a significant impact on the patient and family, resulting in disruptions of roles and responsibilities, routines, relationships, and day-to-day functioning. These changes as well as financial and employment difficulties, marital stress, generalized uncertainty, life-long side effects, and restrictions in daily life are some of the stressors that may impact affected families (Long & Marsland, 2011; Woodgate, 2006). Not only must families adjust to having a child with cancer, they must also acquire new knowledge and skills in order to safely care for their child with cancer at home. Additionally, families face an enormous learning curve, particularly within the first month of diagnosis.

Currently, there are no evidence-based recommendations available to guide the provision of patient/family education for newly diagnosed pediatric oncology patients and their families. Providers use their own discretion regarding educational content, delivery methods, and timing of education; and educational practices that are most effective, appropriate, and useful for newly diagnosed patients and families are currently unknown. The purpose of this systematic review was to evaluate the existing body of evidence to determine the current state of knowledge regarding the delivery of education in newly diagnosed pediatric oncology patients and families. Evidence related to method, content, timing, influencing factors (e.g., demographic), and current educational interventions was systematically identified, summarized, synthesized, and appraised, and final recommendations have been proposed.

Systematic Review Methods

The Children's Oncology Group (COG) Nursing Discipline leadership identified a systematic review leader and mentor for the project. The team leader and senior mentor are doctorally-prepared nurses with experience in teaching and mentoring systematic review groups. Through a competitive process within the COG Nursing Discipline membership, selection of team members was based on academic preparation, clinical nursing experience, and leadership qualities. All team members are based at or affiliated with COG institutions across the United States and Canada. Team members received training on the evidence-based review process through a two-day workshop.

The team developed six clinical questions to focus the systematic review. These clinical questions were created in the form of PICOT questions to ensure clear, concise, searchable questions (Table 1). PICOT represents Patient, Intervention or Issue of Interest, Comparison, Outcome, and Time (Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2015). The COG Nursing Discipline leadership team vetted the PICOT questions.

Table 1. PICOT Questions.

| 1. | Among newly diagnosed pediatric oncology patients and their family members, what educational method(s) (i.e. oral, written, interactive) are most effective and preferred by patients and family members to address informational needs? |

| 2. | What time after an initial pediatric oncology diagnosis is most effective and preferred by patients and family members for delivery of education? |

| 3. | What location is most effective and preferred by patients and family members to deliver and receive education after the initial pediatric oncology diagnosis? |

| 4. | From a patient, family member and healthcare provider perspective, what educational content is important and preferred for newly diagnosed pediatric oncology patients and their family members? |

| 5. | Among newly diagnosed pediatric oncology patients and their family members, what demographic factors (i.e. educational background, culture, language, literacy, gender), and/or clinical factors (i.e. anxiety, self-blame, misconceptions, family support) influence the initial educational information delivered and received (I.e. comprehend) after the oncology diagnosis? |

| 6. | Among newly diagnosed pediatric oncology patients and their family members, what interventions have been developed to improve the comprehension of information related to the diagnosis, treatment and care of the pediatric oncology patient? |

An experienced medical librarian (Leonardelli) helped to develop a search strategy for each PICOT question. The following online databases were searched using a combination of controlled vocabulary terms and keywords: MEDLINE (Ovid), CINAHL (EBSCO), and The Cochrane Library (Wiley). Table 2 contains the MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) terms used in the MEDLINE searches. Complete search strategies are available upon request from the first author.

Table 2. MeSH Terms used in Search Strategies.

| Topic | MeSH Terms* | |

|---|---|---|

| Condition / Disease | Neoplasms Diabetes Mellitus, Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus Anemia, Sickle Cell HIV Infections HIV Epilepsy Hemophilia A Hemophilia B Tracheostomy Tracheotomy Chronic Disease Premature Birth Infant, Premature Infant, Low Birth Weight |

Infant, Newborn Brain Injuries Head injuries, Closed Multiple Trauma Spinal Cord Injuries Spinal Injuries Craniocerebral Trauma Coma, Post-Head Injury Cranial Nerve Injuries Head Injuries, Penetrating Intracranial Hemorrhage, Traumatic Skull Fractures Injury Severity Score Abbreviated Injury Scale |

| Child | Adolescent Child Infant |

|

| Discharge | Patient Discharge | |

| Education | Patient Education as Topic Counseling Teaching Materials Education (MeSH subheading) |

|

Does not include keywords used in search strategy, only subject headings (MeSH)

All database searches were limited to English language. Publication dates had no restrictions; however, conference abstracts, editorials, comments, and letters were excluded. Due to the limited results within pediatric oncology, the search was expanded to include other pediatric diseases or conditions that required the parent or patient to learn new information and/or skills. These diseases or conditions included diabetes, sickle cell disease, human immunodeficiency virus, epilepsy, hemophilia, newly placed tracheostomy or central line, chronic diseases requiring hospitalization, traumatic brain injury, traumatic injury, and premature or newborn infants.

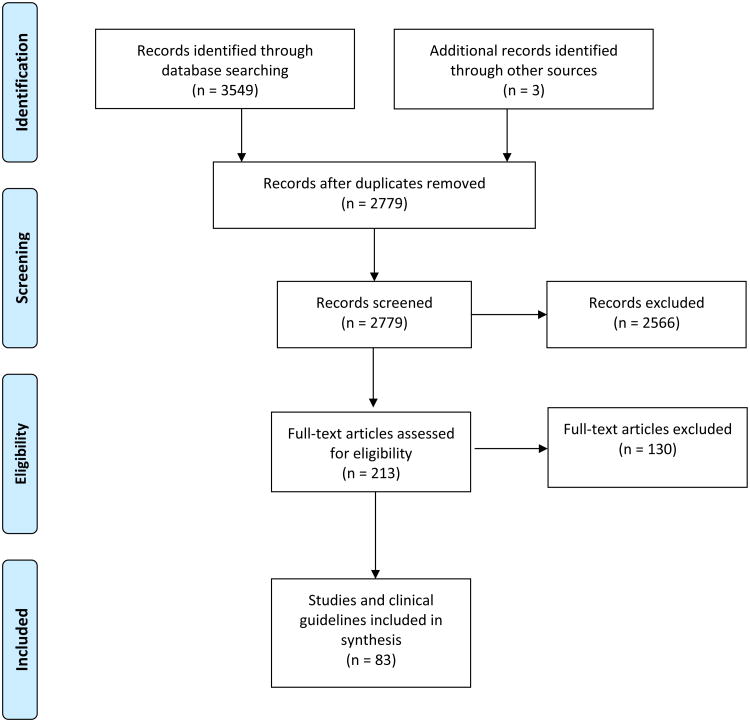

The search was last updated in August 2015. See Figure 1 for the PRISMA diagram (Liberati et al., 2009). Overall, database searches yielded 3,549 results, with three additional articles found after review of the reference lists of relevant articles. Removing duplicate articles revealed 2,779 unique records. The primary author reviewed the title and abstract of the unique records for empirical evidence specific to any of the PICOT questions. Unique records were excluded if they focused on education about cancer prevention or cancer risk, empirical evidence regarding adult cancers (e.g., breast, ovarian, prostate), expert opinion, and education when the outcome was focused on the setting of care (i.e., inpatient versus outpatient). Abstracts were also excluded. These criteria excluded 2,566 records, leaving 213 articles for the team to review. A full text review resulted in the exclusion of an additional 130 articles due to the previously described criteria. Articles on informed consent were included in the initial review; however, full text reviews resulted in the exclusion of these articles. In total, 83 articles are included in this review.

Figure 1. PRISMA Diagram.

Using matrix tables (Garrard, 2014), individual team members summarized components of each article including purpose, design, variables, subjects, measurement tools, and findings. Team members also summarized issues related to the quality of the article according to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) tool (Guyatt et al., 2011). These issues included methodological flaws, inconsistency, indirectness, effect size, and publication bias. Each member presented their matrix table to the team via monthly conference calls. Group consensus was obtained regarding the relevancy of each article and accuracy of the matrix table. Once the summary of articles was complete, the team synthesized the evidence and developed recommendation statements for practice. Using the GRADE criteria, an overall rating for the quality of the body of evidence was determined, and recommendation statements (strong or weak) were identified (Andrews et al., 2013).

In addition to the database search, the team leader searched for clinical guidelines through the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) clinical guideline website and websites of relevant professional organizations. Two team members independently evaluated five clinical guidelines related to the topic, using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II (AGREE II) tool (Cluzeau et al., 2003). During a group conference call, team members discussed the AGREE II scores and any concerns, then voted to determine if each clinical guideline was acceptable for use. By unanimous vote, all five clinical guidelines were included in the review.

Review of the Evidence

PICOT Question 1: Among newly diagnosed pediatric oncology patients and their family members, what educational method(s) are most effective and preferred by patients and family members to address informational needs?

Educational delivery methods among patients newly diagnosed with cancer and their parents and siblings included written materials, verbal discussions, audio recordings, and the Internet (Table 3). Parents and siblings of children newly diagnosed with cancer reported written information as very helpful at the initial diagnosis and during discharge teaching (Aburn & Gott, 2014; Eden, Black, MacKinlay, & Emery, 1994; Flury, Caflisch, Ullmann-Bremi, & Spichiger, 2011; Matutina, 2010) because it provided information they were afraid to ask (Burklow et al., 1988). Parents of premature newborns and parents of children with diabetes, epilepsy, and other chronic illnesses supported these findings (Brett, Staniszewska, Newburn, Jones, & Taylor, 2011; Broedsgaard & Wagner, 2005; Hall-Patch et al., 2010; Mahat, Scoloveno, & Barnette Donnelly, 2007; Sawyer & Gazner, 2004; Woodward, Dawes, Dolan, & Wallymahmed, 2006). In general, parents of children with several different diagnoses (e.g., cancer, diabetes, or newly placed tracheostomy) reported written information as helpful when it was simple, in plain language, brief, well organized, in large font, and included visuals such as pictures and graphics (Aburn & Gott, 2014; Kingston, Brodsky, Volk, & Stanievich, 1995; Nichol, McIntosh, Woo, & Ahmed, 2012).

Table 3. Educational Methods among Pediatric Patients Newly Diagnosed with Cancer and Their Family Members.

| Method | Examples | Reference (First Author, Year) |

|---|---|---|

| Written | Educational binder Information sheets Booklets Literature from external agencies |

Aburn, 2014; Burklow, 1988; Eden, 1994; Flury, 2011; Giacalone, 2005; Matutina, 2010 |

| Verbal | Discussion with healthcare providers Informal discussion with other parents Patient-to-patient discussion |

Aburn, 2014; Flury, 2011; Giacalone, 2005; Levenson, 1982 |

| Internet | Search engines, such as Yahoo and Google American Cancer Society |

Lewis, 2005; Aburn, 2014,Giacalone, 2005 |

| Video | Taped diagnostic discussions | Eden, 1994 |

Two studies reported that adolescents/young adults (AYAs) with cancer prefer a discussion with a HCP as their first choice for the delivery of education, while discussion with others and written materials were preferred as additional methods (Giacalone, Glandino, Spazzan, & Tirelli, 2005; Levenson, Pfefferbaum, Copeland, & Silberberg, 1982). Parents of children newly diagnosed with cancer also reported verbal discussions with HCPs as supportive, but these discussions were also described as overwhelming and exhausting (Flury et al., 2011). Parents of children with cancer or cystic fibrosis (CF) expressed a desire for an informal meeting with other parents, but did not want this to occur until they had overcome the initial shock of the diagnosis (Aburn & Gott, 2014; Sawyer & Gazner, 2004).

An audio recording of the diagnostic talk was helpful to parents of children diagnosed with cancer and parents of premature newborns; this allowed them to replay and recall information that they initially could not absorb or understand (Brett et al., 2011; Eden et al., 1994). In addition, simple videos were an effective way to provide initial education to parents of children newly diagnosed with CF (Sawyer & Gazner, 2004).

Limited information is available on the use of the Internet for education, with mixed findings. One study reported 98% of family caregivers used the Internet for cancer related information when their child was initially diagnosed (Lewis, Gundwardena, & Saadawi, 2005), while another study found only 17% of parents of children newly diagnosed with cancer used the Internet (Aburn & Gott, 2014). Among adolescents and young adults with cancer, 23% used the Internet as a source of information (Giacalone et al., 2005). Parents of children with cancer and parents of premature newborns identified easy navigation, search capabilities, and individualized information for complex issues as important features in a web site or web-based program (Brett et al., 2011; Lewis et al., 2005). Patients reported limited use of the Internet as an educational tool, with only 23% of AYAs newly diagnosed with cancer reporting Internet usage in one study (Giacalone et al., 2005). Another study of AYAs recently diagnosed with HIV confirmed limited use, with only 28% using the Internet (Mayben & Giordano, 2007).

In addition to the method of delivery, the process of learning should be considered (Coates & Ryan, 1996). Teaching strategies for children newly diagnosed with cancer and their family members are listed in Table 4. Additional ways to enhance knowledge and reduce stress for parents of children with diabetes (Broedsgaard & Wagner, 2005; Sullivan-Bolyai, 2009; Sullivan-Bolyai, Bova, Lee, & Johnson, 2012) and parents of premature infants (Burnham, Feeley, & Sherrard, 2013) include experiential learning, such as acquiring specific skills and managing day-to-day care before hospital discharge. An additional recommendation among these parents included individualizing information (Brett, Staniszewska, Newburn, Jones, & Taylor, 2011; Raffray, Semenic, Galeano, & Ochoa Marin, 2014; Sullivan-Bolyai, 2009; Burnham, Feeley, & Sherrard, 2013).

Table 4. Teaching Strategies.

| Strategy | Reference (First Author, Year) |

|---|---|

| Start with informal instruction, then move to more formal methods as the parents adjust to the cancer diagnosis | Aburn, 2011 |

| Repeat information until the parents are able to comprehend the information | Eden, 1994 |

| Encourage parents to watch as nurses ask other healthcare providers questions, to provide role-modeling of effective communication | Brett, 2011 |

| Check that parents understand the information delivered by healthcare providers | Brett, 2011; Garwick, 1995 |

| Establish a partnership and instill a feeling of being on a team | Aburn, 2011; Brett, 2011 |

| Use the same nurse to provide information | Broedsgaard, 2005; Aburn, 2014 |

There is a strong recommendation that written material, short verbal discussions, and audio recordings of the diagnostic discussion be used to provide education to pediatric patients newly diagnosed with cancer, and their parents and siblings.

PICOT Question 2: What time frame after an initial pediatric oncology diagnosis is most effective and preferred by patients and family members for delivery of education?

It is important to recognize that when coping with stressful situations, some patients have a high internal locus of control and are information seekers, while other patients have a low internal locus of control and are information avoiders (Derdiarian, 1987). Most AYAs with cancer sought out maximum disease information at diagnosis as a way to gain control of the situation (Derdiarian, 1987); however, a survey of 563 professionals reported educating AYA patients later in treatment was more important than providing information at diagnosis (Bradlyn, Kato, Beale, & Cole, 2004).

Parents of children with cancer described an emotional strain immediately following the diagnosis that affected their ability to absorb information (Aburn & Gott, 2014). Parents of children with epilepsy and chronic diseases also expressed a sense of being overwhelmed immediately after the diagnosis and needed time to process the diagnosis (Hummelinck & Pollack 2006; McNelis, Buelow, Myers, & Johnson, 2007). Parents of children with insulin-dependent diabetes recounted learning as mechanical at first in order to obtain survival skills, then eventually moved to learning more about caring for their child (Jönsson, Hallstrom, & Lundqvist, 2012; Sullivan-Bolyai, et al.,, 2012; Sullivan-Bolyai, Rosenberg, & Bayard, 2006). This learning process allowed parents of children with diabetes to transition from a feeling of powerlessness to confidence (Wennick & Hallstrom, 2006).

While no article provided a specific time for the delivery of education to parents and children newly diagnosed with cancer, parents expected and preferred to receive information about their child's cancer diagnosis during the initial meeting with the oncologist. However, parents often became overwhelmed and needed time to process the information about their child's diagnosis before learning about essential care (Auburn & Gott, 2014).

There is a strong recommendation that parents of children with cancer need time to process the diagnosis before teaching about essential care can begin. No specific period is provided.

PICOT Question 3: What location is most effective and preferred by patients and family members to deliver and receive education after the initial pediatric oncology diagnosis?

No evidence was identified to answer the question regarding the most effective and preferred location to deliver and receive education.

PICOT Question 4: From a patient, family member and HCP perspective, what educational content is important and preferred for newly diagnosed pediatric oncology patients and their family members?

Educational content considered important among patients with cancer ranged from cancer-specific to psychosocial topics (Table 5). Newly diagnosed children reported the most important information about their cancer diagnosis was knowing what was going to happen to them and understanding the etiology and prognosis (Freeman, O'Dell, & Meola, 2003). This is similar to information requested by children newly diagnosed with diabetes, who want information to understand their disease and treatment (Alderson, Sutcliffe, & Curtis, 2007; Schmidt, Bernaix, Chiappetta, Carroll, & Beland, 2012). Adolescents newly diagnosed with cancer ranked dealing with procedures as the most important topic followed by relationships with friends and getting back to school as the second and third important topics (Decker, Phillips, & Haase, 2004). Adolescents newly diagnosed with diabetes (Woodward et al, 2006) or epilepsy (Risdale, Morgan, & O'Connor, 1999) also reported the importance of knowing about social aspects of the disease and treatment. Several studies described that children and adolescents with cancer wanted to receive more information (Cavusoglu, 2000; Coates & Ryan, 1996; Freeman et al., 2003; Giacalone et al., 2005; Zebrack et al., 2013) but they were often unaware of what questions to ask (Palmer, Mitchell, Thompson, & Sexton, 2007; Sparapani, Jacob, & Nascimento, 2015).

Table 5. Educational Content for Newly Diagnosed Pediatric Oncology Patients and Their Parents.

| PATIENTS | |

|---|---|

| Cancer-Specific Topics | Psychosocial Topics |

| Knowing what will happen Procedures Prognosis Etiology Treatment plan Side effects Everything (even the “hard stuff) For adolescents and young adults: sexuality and fertility information |

How to interact and communicate with friends and family Getting back to school and making job/career plans Learning how to adjust Relationships with and impact on family members |

| References (First Author, Year): Cavusoglu, 2000; Giacalone, 2005; Zebrack, 2013; Palmer, 2007 |

References (First Author, Year): Decker, 2004; Burklow, 1988; Derdiarian, 1987; Giacalone, 2005; Zebrack, 2013 |

| PARENTS | |

| Cancer-Specific Topics | Psychosocial Topics |

| Diagnosis Prognosis Further testing Treatment plan Understanding the disease Side effects Recognizing problems Medical dictionary Where to get answers for questions |

Emotional impact on the child Day-to-day management Making informed decisions Basic self-care Coping with painful procedures Impact of cancer diagnosis on the family |

| References (First Author, Year): Greenberg, 1984; Pyke-Grimm, 1999; Jackson, 2007; Flury, 2011; Sigurdardottir, 2014; Aburn, 2011; Hummelinck, 2006 |

References (First Author, Year): Pyke-Grimm, 1999; Flury, 2011; Sigurdardottir, 2014; Derdiarian, 1987; Flury, 2011; Aburn, 2011; Hummelinck, 2006 |

While parents of children newly diagnosed with cancer likewise desired disease-specific as well as psychosocial information, several studies reported parents also want content related to practical or day-to-day management of their child's cancer (Aburn & Gott, 2011; Derdiarian, 1987; Flury et al., 2011; Hummelinck & Pollack, 2006; Sigurdardottir, Svavarsdottir, Rayens, & Gokun, 2014). A summary of content requested by parents is listed in Table 5. High priority or essential information identified by parents at the time of their child's cancer diagnosis include diagnosis, prognosis, further testing, and treatment plan (Greenberg et al., 1984; Jackson et al., 2007; Pyke-Grimm, Degner, Small, & Mueller, 1999), while medium informational needs included understanding the disease, side effects, and the emotional impact on the child, and low informational needs included coping with painful procedures, and impact of the cancer diagnosis on the family (Pyke-Grimm et al., 1999). Information regarding the child's disease pathology, prognosis, treatments, medication side effects, and what to do in an emergency were requested by parents of children newly diagnosed with diabetes (Schreiner, 2013), epilepsy (McNelis et al., 2007; Reed, 2013), CF (Sawyer & Gazner, 2004), and premature infants (Burnham et al., 2013).

Siblings of children newly diagnosed with cancer wanted to be at the hospital, talk to hospital staff and other patients, and be involved in the patient's care (Prchal & Landolt, 2012). Siblings worried about developing cancer like the ill child and want information on the diagnosis, etiology, and prognosis (Martinson, Gillis, Coughlin Colazzo, Freeman, & Bossert, 1990). When siblings were questioned about a new educational booklet, they described the book as useful, especially the content regarding curing cancer, learning about cancer, feelings related to cancer, and the glossary of terms (Burklow et al., 1988).

A Delphi survey of 199 pediatric oncology nurses reported treatment and disease information as important topics at time of diagnosis, and coping, symptom management, and treatment as important topics after the first week (Kelly & Porock, 2005). A survey of 563 multidisciplinary HCPs reported medical topics as more important than psychological topics to communicate to adolescent patients (Bradlyn et al., 2004). HCPs focused on survival outcomes and functional well-being while AYA patients wanted the focus on school, work, relationships, and fertility/sexual well-being (Thompson, Dyson, Holland, & Joubert, 2013). Pediatric oncologists' perceptions of educational content needs were similar to the parents' desired content, including diagnosis, disease process, prognosis, testing, treatment plan, and availability of physician (Greenberg et al., 1984). However, oncologists thought additional content should include dispelling the risk of contagion of the disease, parents not being responsible for diagnosis, normal parent reactions to diagnosis, what to tell the sick child, and who is the attending physician, while parents did not think those topics were important (Greenberg et al., 1984).

There is a weak recommendation that patients newly diagnosed with cancer and their family members receive medical information including information related to prognosis, etiology, procedures, treatment and side effects, and for adolescents and young adults, sexuality and fertility information.

There is a weak recommendation that patients newly diagnosed with cancer and their family members receive psychosocial information including information related to learning how to adjust, how to interact and communicate with friends and family, relationships, impact on family members, getting back to school, and making job or career plans.

There is a strong recommendation that healthcare providers utilize anticipatory educative content, as both the patient and family members are often unaware of what to ask.

PICOT Question 5: Among newly diagnosed pediatric oncology patients and their family members, what demographic factors and/or clinical factors influence the initial educational information delivered and received after the oncology diagnosis?

Only two demographic factors (age and educational level) were identified as influencing the initial education among pediatric oncology patients. Derdiarian (1987) reported that patients with higher education wanted additional written material about their cancer; however, the specific level of education was not stated. Age also influenced the amount of desired information at the initial diagnosis with AYAs, aged 18 to 39 years, wanting more information than was received (Derdiarian, 1987; Zebrack et al., 2013). However, a study of 20 hemophilia patients found that developmental level, not age, should be factored into the education (Spitzer, 1992). Studies focused on pediatric patients with epilepsy (McNelis, 2007; Risdale, 1999) and diabetes (Schmidt et al., 2012) identified the following factors that influenced the children's ability to comprehend information: using words they could understand, receiving non-contradictory information, and feeling that HCPs had time to answer questions.

Factors influencing education delivered and received among parents of children with cancer or other diseases included delivery of information, emotions, language barriers, relationship with HCPs, the child's condition, and social issues. Table 6 lists the factors that negatively influenced education among parents. Issues with the delivery of information, such as the amount of content presented, use of medical terminology, and inclusion of conflicting information, greatly influenced comprehension of educational material (Aburn & Gott, 2014; Farrell & Christopher, 2013; Flury et al., 2011; Hummelinck & Pollack, 2006; Jackson et al., 2007; McKeller, Pincombe, & Henderson, 2002). Emotional reactions and previous negative experiences with cancer made it difficult for parents to hear and comprehend information. Emotional reactions also influenced the ability to absorb information among parents of children with diabetes (Schmidt et al., 2012; Sullivan-Bolyai, Knafl, Deatrick, & Grey, 2003), hemophilia (Furmedge, Lima, Monagle, Barnes, & Newall, 2013), and premature infants (Sneath, 2009). Language barriers affected parents' ability to comprehend information. A descriptive study of 36 mothers found that interpreters for Latino parents of premature infants were needed 75% of the time but only used 67% of the time (Miquel-Verges, Donohue, & Boss, 2011). Despite the use of interpreters, language barriers may still be an issue due to the interpreters' inability to accurately translate complex medical information related to the care of pediatric patients with cancer (Abbe, Simon, Angiolillo, Ruccione, & Kodish, 2006) or failure to incorporate cultural issues for pediatric patients with cancer (Abbe et al., 2006) and diabetes (Sullivan-Bolyai, 2009).

Table 6. Factors Negatively Influencing Education among Parents.

| Factor | References (First Author, Year) |

|---|---|

| DELIVERY OF INFORMATION | |

| Large amount of written and verbal information Use of medical terms and jargon Conflicting information from healthcare providers Child presence in educational session |

Aburn, 2014; Flury 2011; Jackson, 2007; Hummelinck, 2006; Farrell, 2013; McKeller, 2002; Young 2011 |

| EMOTIONS | |

| Fear, shock, grief, anxiety Negative experiences with cancer |

Aburn, 2014; Levi, 2000; Aburn, 2011; Hatton, 1996; Eden, 1994; Garwick, 1995 |

| LANGUAGE BARRIERS | |

| Lack of use of interpreters Inability of the interpreter to accurately translate complex medical information Lack of understanding of cultural issues |

Miquel-Verges, 2011; Abbe, 2006; Sullivan-Bolyai, 2009 |

| RELATIONSHIP WITH HEALTHCARE PROVIDERS (HCPs) | |

| Negative history with the child's doctor Overwhelmed with multiple HCPs teaching simultaneously HCP too busy to answer questions Inconsistent HCPs Not feeling like a partner in the team |

Garwick, 1995; Levi, 2000; McKeller, 2002; Ridsdale, 1999; Reed, 2013; Risdale, 1999; Reed, 2013 |

| CHILD'S CONDITION AND SOCIAL ISSUES | |

| Child's worsening medical condition Lack of daycare or babysitting for siblings Lack of transportation to the hospital Information provided without child present, along with assurance that the child was comfortable and cared for |

Graf, 2008; Young, 2011; Aburn, 2011 |

The relationship with HCPs affected parents' ability to comprehend information, including past experiences with the child's doctor (Garwick, Patterson, Bennett, & Blum, 1995). Parents also felt overwhelmed when multiple HCPs simultaneously entered their child's room (Levi, Marsick, Drotar, & Kodish, 2000) or when the HCP was too busy to answer questions (McKeller, Pincombe, & Henderson, 2002; Ridsdale et al., 1999). Parents of children newly diagnosed with epilepsy found it beneficial when they had consistent HCPs and felt they were a partner in the team (Reed, 2013; Risdale et al., 1999). Parents missed planned educational sessions due to the child's medical condition, lack of daycare or babysitting for siblings, and lack of transportation to the hospital (Graf, Montagnino, Hueckel, & McPherson, 2008). Parents of children with cancer wanted information about their child's diagnosis without the child being present (Young et al., 2011) but wanted assurance that the child was comfortable and cared for during educational sessions (Aburn & Gott, 2011).

Only one study evaluated factors affecting information received among siblings of patients with cancer. Thirty-two siblings related a lack of information about their sibling's diagnosis with cancer due to limited time with their parents or HCPs and a sense that little information was shared as a protective mechanism (Freeman et al., 2003).

There is a strong recommendation that educational and developmental level should be considered when delivering educational information to the pediatric oncology patient.

There is a strong recommendation that educational information should be provided to parents by consistent healthcare providers, using vocabulary that the recipient understands, in a consistent manner, allowing time to answer questions.

There is a strong recommendation that parents' emotional state, language barriers, cultural issues, and social issues (including transportation, sibling care, and the condition of the hospitalized child) be considered when providing education to parents.

PICOT Question 6: Among newly diagnosed pediatric oncology patients and their family members, what interventions have been developed to improve the comprehension of information related to the diagnosis, treatment and care of the pediatric oncology patient?

Limited intervention studies were identified related to the education of patients newly diagnosed with cancer, their parents, and/or siblings (Table 7). However, several intervention studies for patients and families of children with other diagnoses, including diabetes, premature or high-risk newborns, and recently placed tracheostomies, reported positive results. These interventions include web-based programs, structured teaching tools, videos, and interactive education.

Table 7.

Interventions for Pediatric Patients with Cancer and/or Their Caregivers

| Intervention | Design/Variables | Sample | Findings | Reference (First Author, Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Web-based programs | Mixed method study of Web-based resource, including information regarding emotions, issues related to childhood cancer, and electronic communication with research team | 21 families including patients with newly diagnosed cancer, their caregivers, and siblings | 43% (n=9) of families accessed the site, primarily on peer discussion groups Barriers to accessing the site included being too tired and too overwhelmed |

Ewing, 2009 |

| Pretest/post-test design regarding educational website and online support | 10 mothers and 9 fathers of children newly diagnosed with cancer | Well-being significantly improved after intervention No significant change in coping, hardiness, or adaptation 76% found website helpful |

Svavarsdottir 2006 | |

| Standardized teaching | Quasi-experimental design of discharge program (education, home visit, phone call) vs. routine care | 49 caregivers of children with cancer in Turkey | Control group had significantly more symptoms (fever, nausea, vomiting, mucositis, catheter problems), unplanned clinic visits, and unplanned admissions | Yilmaz 2010 |

| Post-test design of teaching support materials (refrigerator magnet and wallet card) | 3 parents of children newly diagnosed with cancer | Materials provided effective method for having phone numbers readily available and teaching parents when to call | Matutina, 2010 |

Two studies evaluated web-based programs, including online education and support for patients newly diagnosed with cancer and their families. These patients and families primarily accessed the online discussion groups for support and found the support helpful (Ewing et al., 2009; Svavarsdottir & Sigurdardottir, 2006). Reasons for not accessing the site included being too overwhelmed with information and feeling too tired (Ewing et al., 2009).

Two studies evaluated structured teaching tools among parents or caregivers of children newly diagnosed with cancer (Matutina, 2010; Yilmaz & Ozsoy, 2010). Children recently diagnosed with cancer whose caregivers participated in a structured discharge program had fewer symptoms (e.g., fever, nausea, vomiting, mucositis), central venous catheter problems, unplanned clinic visits, and unplanned admissions when compared to a routine care group (Yilmaz & Ozsoy, 2010). In addition, use of a novel teaching support (refrigerator magnet and wallet card) enhanced retention of important information among parents of children newly diagnosed with cancer (Matutina, 2010). Standardized teaching plans or checklists significantly improved knowledge among caregivers of hospitalized newborns (Blagojevic & Stephens, 2008) and children with recently placed tracheostomies (Hotaling, Zablocki, & Madgy, 1995). A discharge booklet and planning program was associated with increased knowledge and perception of readiness at discharge among parents of newborns (Cagan & Meier, 1983; McKeller et al., 2002; Shieh et al., 2010).

The use of videos as an educational strategy has not been evaluated among children with cancer and their families, however, studies among other pediatric populations found positive results. A virtual dialogue with a clinical neuropsychologist and a brain injury survivor was associated with a significant increase in family caregivers' knowledge and ability to communicate with HCPs when compared from before the virtual dialogue to after (Knapp, Gillespie, Malec, Zier, & Harless, 2013). Viewing informational videos was associated with a significant increase in knowledge and information application among parents of premature infants (Suk & Jiyoung, 2012), patients being screened for HIV (Bloch & Bloch, 2013; Calderon et al., 2009), or caregivers of children seen in the emergency department (Keane, Hammond, Keane, & Hewitt, 2005). A team of neonatal providers documented the process of developing an educational discharge brochure and DVD for parents of premature infants (Ronan et al., 2015). The providers identified important characteristics of an effective brochure, which included optimal organization, specificity of instructions, suitability for clients with a low reading level, and use of high-quality paper, while important qualities of the DVD include content parallel to the brochure and use of real-life video with parent involvement in a home setting (Ronan et al., 2015).

No studies assessed interactive education among children newly diagnosed with cancer; however, studies with other pediatric populations evaluated the use of skill demonstrations, parent mentors, and actively caring for the hospitalized child. Parents of children with a new tracheostomy (Tearl & Hertzog, 2007) or newly diagnosed with diabetes (Sullivan-Bolyai et al., 2012) who practiced skills on a manikin or simulator demonstrated more knowledge, problem-solving skills, and self-efficacy when compared to parents without the experiential opportunity. Survival skill training increased the comfort level of parents of newly diagnosed diabetic children (Schmidt, 2012). Parents who had the opportunity to care for their newborn or premature infant (Costello & Chapman, 1998) or for their infant with a congenital heart defect (Yang, Chen, Mao, Gau, & Wang, 2004) prior to discharge had more knowledge and confidence in caring for their baby after discharge. Parents of newly diagnosed children with diabetes favored the use of a parent mentor program upon discharge (Sullivan-Bolyai, 2009; Sullivan-Bolyai et al., 2004).

Siblings of children with cancer benefitted from age-appropriate interactive education. Siblings who participated in the interactive sessions with a clinical psychologist or reflective journaling and personal diaries reported increased knowledge about their sibling's treatment and side effects, and decreased stress and anxiety (Nolbris & Ahlström, 2014; Prchal & Landolt, 2012). In addition, siblings of hospitalized children who participated in a program to explore medical equipment and receive information regarding illness, treatment, and daily routine of the hospitalized sibling had significantly less anxiety than siblings who did not participate in the program (Gursky, 2007).

There is a strong recommendation that structured teaching tool(s) be used to guide the provision of general education and discharge instructions to parents of children newly diagnosed with cancer.

There is a strong recommendation that siblings of children newly diagnosed with cancer should receive age appropriate, interactive education.

Recommendations

From the body of evidence, 10 recommendation statements for children newly diagnosed with cancer and their family members were developed (see text and Table 8). Current pediatric clinical guidelines include several of these practice recommendations, specifically the need for multiple methods for educational delivery (Cincinnati Children's Hospital, 2009, 2011, and 2012), allowing time after the new diagnosis to process the information (Cincinnati Children's Hospital, 2013), and providing consistent information in understandable vocabulary with time for questions (Cincinnati Children's Hospital, 2011; Sheets et al., 2011). Finally, a clinical guideline focused on communication highlights the recommendation for a structured teaching tool for discharge information (Cincinnati Children's Hospital, 2011).

Table 8. Recommendation Statements.

| PICOT Question | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| 1 | There is a strong recommendation that written material, short verbal discussions, and audio recordings of the diagnostic discussion be used to provide education to pediatric patients newly diagnosed with cancer, and their parents and siblings. |

| 2 | There is a strong recommendation that parents of children with cancer need time to process the diagnosis before teaching about essential care can begin. No specific period is provided. |

| 4 | There is a weak recommendation that patients newly diagnosed with cancer and their family members receive medical information including information related to prognosis, etiology, procedures, treatment and side effects, and for adolescents and young adults, sexuality and fertility information. |

| 4 | There is a weak recommendation that patients newly diagnosed with cancer and their family members receive psychosocial information including information related to learning how to adjust, how to interact and communicate with friends and family, relationships, impact on family members, getting back to school, and making job or career plans. |

| 4 | There is a strong recommendation that healthcare providers utilize anticipatory educative content, as both the patient and family members are often unaware of what to ask. |

| 5 | There is a strong recommendation that educational and developmental level should be considered when delivering educational information to the pediatric oncology patient. |

| 5 | There is a strong recommendation that educational information should be provided to parents by consistent healthcare providers, using vocabulary that the recipient understands, in a consistent manner, allowing time to answer questions. |

| 5 | There is a strong recommendation that parents' emotional state, language barriers, cultural issues, and social issues (including transportation, sibling care, and the condition of the hospitalized child) be considered when providing education to parents. |

| 6 | There is a strong recommendation that structured teaching tool(s) be used to guide the provision of general education and discharge instructions to parents of children newly diagnosed with cancer. |

| 6 | There is a strong recommendation that siblings of children newly diagnosed with cancer should receive age appropriate, interactive education. |

Overall Quality of Evidence

Eighty-three articles were used as evidence to answer the PICOT questions. Evidence consisted of systematic reviews (n=2), research studies (n=80), and one unpublished dissertation. Research study designs included randomized control trials (RCTs), cross-sectional studies, pilot studies, pre/post-test studies, post intervention studies, descriptive studies, retrospective chart reviews, case studies, qualitative studies, and mixed-methods studies.

Methodological flaws of the quantitative evidence included studies with small sample sizes and use of non-validated tools to measure outcomes. Several RCTs did not report their randomization method, and research assistants were not blinded to the treatment in three RCTs. Methodological flaws of several of the qualitative studies included lack of disclosure of rigor or interview questions. Two systematic reviews lacked details of methodology, including who performed the search, the search strategy, and the appraisal of evidence.

Two issues of indirectness were found in the evidence. The primary issue of indirectness was that most of the evidence was derived from samples of from parents consisting of mothers and an underrepresentation of fathers. The other issue of indirectness included one descriptive study that evaluated usage of the Internet only in a large metropolitan area, which may be inconsistent with other areas of the nation. No concerns were identified with inconsistency, imprecision, or publication bias. Overall rating of the quality of the body of evidence is low.

Conclusion/Discussion

Currently, no evidence-based recommendations exist in pediatric oncology to direct the consistent, effective delivery of cancer education to newly diagnosed patients and families. Identification of evidence-based practice recommendations can guide HCPs in providing consistent care to patients and families, increase awareness of best practices, and improve the quality of care and health outcomes (Woolf, Grol, Hutchinson, Eccles, & Grimshaw, 1999). This systematic review focused on identifying best practices for delivery of education to newly diagnosed pediatric oncology patients and their families. Ten recommendations were developed from the evidence, addressing five of the six PICOT questions. These recommendations focus on methods, timing, content, influencing factors, and effective interventions when educating children newly diagnosed with cancer and/or their family members. Transferring these recommendations into practice may enhance the quality of education delivered by HCPs, and received by patients and families.

Impeding development of further recommendations is the limited number and quality of published studies designed to evaluate education delivery methods for newly diagnosed children with cancer and their family members. Our team identified 83 research-based articles focused on the topic of education; however, only 33 of those articles related to a cancer diagnosis and the remaining 50 articles represented non-cancer diseases and conditions. Only PICOT question four, focusing on educational content, contained more cancer-specific evidence than non-cancer diseases and conditions. Furthermore, the majority of available evidence is from the parent's perspective, primarily the mother, with limited information from the fathers, patients (especially younger than adolescent age), siblings, and healthcare providers. Finally, the majority of evidence (53 articles) used in this literature review was more than 5 years old. The age of evidence should be considered when interpreting results such as method of delivery, which may not accurately reflect current options for educational delivery.

Additional studies are needed, including qualitative studies to further identify essential qualities of effective education among patients newly diagnosed with cancer and their family members, and quasi-experimental studies or RCTs to develop and evaluate educational interventions and identify factors that could influence comprehension of information (e.g., age, literacy level, and language barriers). Dissemination of this evidence will allow for a better understanding and provide the knowledge needed to develop evidence-based guidelines for best practices in patient/family education of newly diagnosed pediatric oncology patients. Effective and consistent patient/family education can potentially improve understanding of the child's diagnosis, increase satisfaction and confidence with care, and improve the quality of life for children newly diagnosed with cancer and their family members.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Supported by a Children's Oncology Group Nursing Fellowship in Patient/Family Education awarded to Cheryl Rodgers and funded through the National Cancer Institute/National Clinical Trials Network Group Operations Center Grant (U10CA180886; PI-Adamson), and by Alex's Lemonade Stand Foundation. Presented, in part, at the Children's Oncology Group's “State of the Science Symposium: Patient/Family Education in Pediatric Oncology,” on October 6, 2015, in Dallas, TX; Symposium supported by the National Cancer Institute (R13CA196165 PIs-Landier & Hockenberry).

Contributor Information

Cheryl C. Rodgers, Duke University School of Nursing, 307 Trent Drive, Durham, NC 27710.

Catherine M. Laing, University of Calgary Faculty of Nursing, 2500 University Drive NW, Calgary, AB T2N 1N4.

Ruth Anne Herring, Cook Children's Medical Center, 801 Seventh Avenue, Ft. Worth, TX 76104-2796.

Nancy Tena, C.S. Mott Children's Hospital, University of Michigan Health System, 1540 E. Hospital Drive, Ann Arbor, MI 48103.

Adrianne Leonardelli, University of Virginia School of Nursing, 225 Jeanette Lancaster Way, Charlottesville, VA 22903.

Marilyn Hockenberry, Duke University School of Nursing, 307 Trent Drive, Durham, NC 27710.

Verna Hendricks-Ferguson, Saint Louis University, School of Nursing, 3525 Caroline Mall, St. Louis, MO 631104.

References

- Abbe M, Simon C, Angiolillo A, Ruccione K, Kodish ED. A survey of language barriers from the perspective of pediatric oncologists, interpreters, and parents. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2006;47(6):819–824. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aburn G, Gott M. Education given to parents of children newly diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A narrative review. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 2011;28(5):300–305. doi: 10.1177/1043454211409585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aburn G, Gott M. Education given to parents of children newly diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: The parents' perspective. Pediatric Nursing. 2014;40(5):243–256. Retrieved from http://www.pediatricnursing.net. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alderson P, Sutcliffe K, Curtis K. Children as young as 4 years of age with type 1 diabetes showed understanding and competence managing their education. Evidence Based Nursing. 2007;10(1):28. doi: 10.1136/ebn.10.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews J, Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Alderson P, Dahm P, Falck-Ytter Y, et al. Schunemann HJ. GRADE guidelines: 14. Going from evidence to recommendations: The significance and presentation of recommendations. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2013;66:719–725. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.03.0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blagojevic J, Stephens S. Evaluation of standardized teaching plans for hospitalized pediatric patients: A performance improvement project. Journal for Healthcare Quality. 2008;30(3):16–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1945-1474.2008.tb01138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloch SA, Bloch AJ. Using video discharge instructions as an adjunct to standard written instructions improved caregivers' understanding of their child's emergency department visit, plan, and follow-up: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatric Emergency Care. 2013;29(6):699–704. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3182955480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradlyn AS, Kato PM, Beale IL, Cole S. Pediatric oncology professionals' perceptions of information needs of adolescent patients with cancer. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 2004;21(6):335–342. doi: 10.1177/1043454204270250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brett J, Staniszewska S, Newburn M, Jones N, Taylor L. A systematic mapping review of effective interventions for communicating with, supporting and providing information to parents of preterm infants. BMJ Open. 2011;1:1–11. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2010-000023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broedsgaard A, Wagner L. How to facilitate parents and their premature infant for the transition home. International Nursing Review. 2005;52:196–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2005.00414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burklow JT, Blumberg BD, Laufer JK, Cosgrove M, Adams-Greenly M, Kranstuber SM. The use of formative evaluation methods in the development of patient/family education materials. Journal of the Association of Pediatric Oncology Nurses. 1988;5(1&2):12–15. doi: 10.1177/104345428800500103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnham N, Feeley N, Sherrard K. Parents' perceptions regarding readiness for their infant's discharge from the NICU. Neonatal Network. 2013;32(5):324–334. doi: 10.1891/0730-0832.32.5.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cagan J, Meier P. Evaluation of a discharge planning tool for use with families of high-risk infants. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing. 1983;12(4):275–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1983.tb01076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderon Y, Leider J, Hailpern S, Haughey M, Ghosh R, Lombardi P, et al. Bauman L. A randomized control trial evaluating the educational effectiveness of a rapid HIV posttest counseling video. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2009;36(4):207–210. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318191ba3f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavusoglu H. Problems related to the diagnosis and treatment of adolescents with leukemia. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing. 2000;23:15–26. doi: 10.1080/014608600265183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cincinnati Children's Hospital. Formal education plan for pediatric inpatient discharge. 2009 Retrieved from http://www.guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=15123&search=formal+education+plan.

- Cincinnati Children's Hospital. Communication of health care information to patients and caregivers using multiple means. 2011 Retrived from http://www.guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=34160&search=communication+multiple+means.

- Cincinnati Children's Hospital. Timing of patient/family preoperative education and its relationship to retention of information. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=38437&search=preoperative+education.

- Cincinnati Children's Hospital. Support from bedside nurses for caregivers of children newly diagnosed with type 1 diabetes mellitus. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=46459&search=type+1+diabetes+mellitus.

- Cluzeau FA, Burgers JS, Brouwers M, Grol R, Mäkelä M, Littlejohns P, et al. Hunt C. Development and validation of an international appraisal instrument for assessing the quality of clinical practice guidelines: The AGREE project. Quality and Safety in Health Care. 2003;12(1):18–23. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates VE, Ryan SC. Patient education and quality assurance in nursing. Nursing Times Research. 1996;1(4):307–317. doi: 10.1177/174498719600100411. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Costello A, Chapman J. Mothers' perceptions of the care-by-parent program prior to hospital discharge of their preterm infants. Neonatal Network. 1998;17(7):37–42. Retrieved from http://www.springerpub.com/neonatal-network.html. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker C, Phillips CR, Haase JE. Information needs of children with cancer. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 2004;21(6):327–334. doi: 10.1177/1043454204269606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derdiarian A. Informational needs of recently diagnosed cancer patients: A theoretical framework, Part I. Cancer Nursing. 1987;10(2):107–115. Retrieved from http://journals.lww.com/cancernursingonline/pages/default.aspx. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eden OB, Black I, MacKinlay GA, Emery AE. Communication with parents of children with cancer. Palliative Medicine. 1994;8:105–114. doi: 10.1177/026921639400800203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing LJ, Long K, Rotondi A, Howe C, Bill L, Marsland AL. Brief report: A pilot study of a web-based resource for families of children with cancer. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2009;34(5):523–529. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell MH, Christopher SA. Frequency of high-quality communication behaviors used by primary care providers of heterozygous infants after newborn screening. Patient Education and Counseling. 2013;90(2):226–232. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell M, Deuster L, Donovan J, Christopher S. Pediatric residents' use of jargon during counseling about newborn genetic screening results. Pediatrics. 2008;122(2):243–249. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flury M, Caflisch U, Ullmann-Bremi A, Spichiger E. Experiences of parents caring for their child after a cancer diagnosis. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 2011;28(3):143–153. doi: 10.1177/1043454210378015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman K, O'Dell C, Meola C. Childhood brain tumors: Children's and Sibling's Concerns Regarding the Diagnosis and Phase of Illness. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 2003;20(3):133–140. doi: 10.1053/jpon.2003.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furmedge J, Lima S, Monagle P, Barnes C, Newall F. “I don't want to hurt him.” Parents' experiences of learning to administer clotting factor to their child. Haemophilia. 2013;19:206–211. doi: 10.1111/hae.12030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrard J. Health Sciences Literature Review Made Easy: The Matrix Method. 4th. Boston: Jones & Bartlett; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Garwick AW, Patterson J, Bennett FC, Blum RW. Breaking the news: How families first learn about their child's chronic condition. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1995;149:991–997. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1995.02170220057008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacalone A, Blandino M, Spazzan S, Tirelli U. Cancer and aging: Are there any differences in the information needs of elderly and young patients? Results from an Italian observational study. Annals of Oncology. 2005;16(12):1982–1983. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf JM, Montagnino BA, Hueckel R, McPherson ML. Children with new tracheostomies: Planning for family education and common impediments to discharge. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2008;43:788–794. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg LW, Jewett LS, Gluck RS, Champion LAA, Leikin SL, Altieri MF, Lipnick RN. Giving information for a life-threatening diagnosis. American Journal of Diseases of Children. 1984;138:649–653. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1984.02140450031010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gursky B. The effect of educational interventions with siblings of hospitalized children. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 2007;28:392–398. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e318113203e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, Kunz R, Vist G, Brozek J, et al. Schunemann HJ. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction – GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2011;64:383–394. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall-Patch L, Brown R, House A, Howlett S, Kemp S, Lawton G, et al. NEST collaborators. Acceptability and effectiveness of a strategy for the communication of the diagnosis of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsia. 2010;51(1):70–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatton DL. Case study: Timothy's story: Managing an infant with insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. Canadian Journal of Diabetes Care. 1996;20(3):28–33. Retrieved from http://www.canadianjournalofdiabetes.com. [Google Scholar]

- Hotaling AJ, Zablocki H, Madgy DN. Pediatric tracheotomy discharge teaching: A comprehensive checklist format. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolargyngology. 1995;33:113–126. doi: 10.1016/0165-5876(95)01195-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummelinck A, Pollock K. Parents' information needs about the treatment of their chronically ill child: A qualitative study. Patient Education and Counseling. 2006;62:228–234. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson AC, Stewart H, O-Toole M, Tokatlian N, Enderby K, Miller J, Ashley D. Pediatric brain tumor patients: Their parent's perceptions of the hospital experience. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 2007;24:95–105. doi: 10.1177/1043454206206030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jönsson L, Hallström I, Lundqvist A. The logic of care: Parents' perceptions of the educational process when a child is newly diagnosed with type 1 diabetes. Pediatrics. 2012;12:165, 1–11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-12-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keane V, Hammond G, Keane H, Hewitt J. Quantitative evaluation of counseling associated with HIV testing. Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health. 2005;36(1):228–232. Retrieved from http://www.tm.mahidol.ac.th/seameo/publication.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly KP, Porock D. A survey of pediatric oncology nurses' perceptions of parent educational needs. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 2005;22:58–66. doi: 10.1177/1043454204272537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingston L, Brodsky L, Volk MS, Stanievich J. Development and assessment of a home care tracheotomy manual. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolarngology. 1995;32:213–222. doi: 10.1016/0165-5876(95)01167-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp M, Gillespie E, Malec JF, Zier M, Harless W. Evaluation of a virtual dialogue method for acquired brain injury education: A pilot study. Brain Injury. 2013;27(4):388–393. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2013.765596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenson PM, Pfefferbaum BJ, Copeland DR, Silberberg Y. Information preferences of cancer patients ages 11-20 years. Journal of Adolescent Health Care. 1982;3:9–13. doi: 10.1016/S0197-0070(82)80021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi R, Marsick R, Drotar D, Kodish E. Diagnosis, disclosure, and informed consent: Learning from parents of children with cancer. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology. 2000;22(1):3–12. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200001000-00002. Retrieved from http://journals.lww.com/jpho-online/Pages/default.aspx. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis D, Gundwardena S, Saadawi GE. Caring connections: Developing an Internet resource for family caregivers of children with cancer. CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing. 2005;23(5):265–274. doi: 10.1097/00024665-200509000-00011. Retrieved from http://journals.lww.com/cinjournal/pages/default.aspx. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long KA, Marsland AL. Family adjustment to childhood cancer: A systematic review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2011;14(1):57–88. doi: 10.1007/s10567-010-0082-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahat G, Scoloveno MA, Barnette Donnelly C. Written educational materials for families of chronically ill children. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 2007;19(9):471–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2007.00254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinson IM, Gillis C, Coughlin Colazzo D, Freeman M, Bossert E. Impact of childhood cancer on healthy school-age siblings. Cancer Nursing. 1990;13(3):183–190. doi: 10.1097/00002820-199006000-00008. Retrieved from http://journals.lww.com/cancernursingonline/pages/default.aspx. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matutina R. Educating families of children newly diagnosed with cancer. Cancer Nursing Practice. 2010;9(1):28–30. Retrieved from http://journals.rcni.com/journal/cnp. [Google Scholar]

- Mayben JK, Giordano TP. Internet use among low-income persons recently diagnosed with HIV infection. AIDS Care. 2007;19(9):1182–1187. doi: 10.1080/09540120701402806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeller LV, Pincombe J, Henderson AM. Congratulations you're a mother: A strategy for enhancing post-natal education for first-time mothers investigated through an action research cycle. Australian College of Midwives Incorporated. 2002;15(3):24–31. doi: 10.1016/S1031-170X(02)80005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNelis AM, Buelow J, Myers J, Johnson EA. Concerns and needs of children with epilepsy and their parents. Clinical Nurse Specialist. 2007;21(4):195–202. doi: 10.1097/01.NUR.0000280488.33884.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E. Evidence-based practice in nursing & healthcare. 3rd. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Miquel-Verges F, Donohue PK, Boss RD. Discharge of infants from NICU to Latino families with limited English proficiency. Journal of Immigrant Minority Health. 2011;13:309–314. doi: 10.1007/s10903-010-9355-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichol H, McIntosh B, Woo S, Ahmed S. Evaluation of the usefulness and accessibility of a provincial educational resource for pediatric type 1 diabetes: A guide for families: Diabetes care for children and teens. Canadian Journal of Diabetes. 2012;36(5):263–268. doi:0.1016/j.jcjd.2012.08.005. [Google Scholar]

- Nolbris MJ, Ahlström BH. Siblings of children with cancer: Their experiences of participating in a person-centered support intervention combining education, learning and reflection: Pre- and post-intervention interviews. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2014;18:254–260. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2014.01.002. doi:org/10.1016/j.ejon.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer S, Mitchell A, Thompson K, Sexton M. Unmet needs among adolescent cancer patients: A pilot study. Palliative and Supportive Care. 2007;5:127–134. doi: 10.1017/s1478951507070198. doi:10.10170S1478951507070198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prchal A, Landolt MA. How siblings of pediatric cancer patients experience the first time after diagnosis. Cancer Nursing. 2012;35(2):133–140. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31821e0c59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyke-Grimm KA, Degner L, Small A, Mueller B. Preferences for participation in treatment decision making and information needs of parents of children with cancer: A pilot study. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 1999;16(1):13–24. doi: 10.1177/104345429901600103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffray M, Semenic S, Galeano SO, Ochoa Marin SC. Barriers and facilitators to preparing families with premature infants for discharge home from the neonatal unit. Perceptions of health care providers. Investigacion y Educacion en Enfermeria. 2014;32(3):379–392. doi: 10.17533/udea.iee.v32n3a03. Retrieved from https://aprendeenlinea.udea.edu.co/revistas/index.php/iee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed MP. Parental caregivers' description of caring for children with intractable epilepsy. William F. Connell School of Nursing; Boston, MA: 2013. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Ridsdale L, Morgan M, O'Connor C. Promoting self-care in epilepsy: The views of patients on the advice they had received from specialists, family doctors and an epilepsy nurse. Patient Education and Counseling. 1999;37:43–47. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(98)00094-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronan S, Liberatos P, Weingarten S, Wells P, Garry J, O'Brien K, et al. Nevid T. Development of home educational materials for families of preterm infants. Neonatal Network. 2015;34(2):102–112. doi: 10.1891/0730-0832.34.2.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer SM, Gazner JA. What follows newborn screening? An evaluation of a residential education program for parents of infants with newly diagnosed cystic fibrosis. Pediatrics. 2004;114(2):411–416. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.2.411. Retrieved from http://pediatrics.aappublications.org. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt CA, Bernaix LW, Chiappetta M, Carroll E, Beland A. In-hospital survival skills training for type 1 diabetes: perceptions of children and parents. The American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing. 2012;37(2):88–94. doi: 10.1097/NMC.0b013e318244febc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiner B. Diabetes education in hospitalized children developmental and situational concerns. Critical Care Nursing Clinics of North America. 2013;25:101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheets KB, Crissman BG, Feist CD, Sell SL, Johnson LR, Donahue KC, et al. Brasington CK. Practice guidelines for communicating a prenatal or postnatal diagnosis of Down syndrome: Recommendations of the National Society of Genetic Counselors. Journal of Genetic Counseling. 2011;20(5):432–441. doi: 10.1007/s10897-011-9375-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shieh SJ, Chen HL, Liu FC, Liou CC, Lin YH, Tseng HI, Wang RH. The effectiveness of structured discharge education on maternal confidence, caring knowledge and growth of premature newborns. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2010;19:3307–3313. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigurdardottir AO, Svavarsdottir EK, Rayens MK, Gokun Y. The impact of a web-based educational and support intervention on parents' perception of their children's cancer quality of life: An exploratory study. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 2014;31(3):154–165. doi: 10.1177/1043454213515334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sneath N. Discharge teaching in the NICU: Are parents prepared? An integrative review of parents' perceptions. Neonatal Network. 2009;28(4):237–246. doi: 10.1891/0730-0832.28.4.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparapani V, Jacob E, Nascimento L. What is it like to be a child with type 1 diabetes mellitus? Pediatric Nursing. 2015;41(1):17–22. Retrieved from http://www.pediatricnursing.net. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer A. Children's knowledge of illness and treatment experiences in hemophilia. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 1992;7(1):43–51. Retrieved from http://www.pediatricnursing.org. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suk RJ, Jiyoung L. Development and evaluation of a video discharge education program focusing on mother-infant interaction for mothers of premature infants. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2012;42(7):936–946. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2012.42.7.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan-Bolyai S. Familia Apoyadas: Latino families supporting each other for diabetes care. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2009;24(6):495–505. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan-Bolyai S, Bova C, Lee M, Johnson K. Development and pilot testing of a parent education intervention for type I diabetes. The Diabetes Educator. 2012;38(1):50–57. doi: 10.1177/0145721711432457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan-Bolyai S, Grey M, Deatrick J, Gruppuso P, Giraitis P, Tamborlane W. Helping other mothers effectively work at raising young children with type 1 diabetes. The Diabetes Educator. 2004;30(3):476–484. doi: 10.1177/014572170403000319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan-Bolyai S, Knafl K, Deatrick J, Grey M. Maternal management behaviors for young children with type 1 diabetes. The American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing. 2003;28(3):160–166. doi: 10.1097/00005721-200305000-00005. Retrieved from http://journals.lww.com/mcnjournal/pages/default.aspx. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan-Bolyai S, Rosenberg R, Bayard M. Fathers' reflections on parenting young children with type I diabetes. Maternal Child Nursing. 2006;31(1):24–31. doi: 10.1097/00005721-200601000-00007. Retrieved from http://journals.lww.com/mcnjournal/pages/default.aspx. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svavarsdottir EK, Sigurdardottir AO. Developing a family-level intervention for families of children with cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2006;33(5):983–990. doi: 10.1188/06.ONF.983-990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tearl DK, Hertzog JH. Home discharge of technology-dependent children: Evaluation of a respiratory-therapist driven family education program. Respiratory Care. 2007;52(2):171–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson K, Dyson G, Holland L, Joubert L. An exploratory study of oncology specialists' understanding of the preferences of young people living with cancer. Social Work in Health Care. 2013;52:166–190. doi: 10.1080/00981389.2012.737898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wennick A, Hallstrom I. Swedish families' lived experience when a child is first diagnosed as having insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Journal of Family Nursing. 2006;12(4):368–389. doi: 10.1177/1074840706296724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodgate RL. Siblings' experiences with childhood cancer. Cancer Nursing. 2006;29(5):406–414. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200609000-00010. Retrieved from http://journals.lww.com/cancernursingonline/pages/default.aspx. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward A, Dawes S, Dolan D, Wallymahmed M. What education do people with type 1 diabetes want and how should we provide it? Results of a survey of patients with type 1 diabetes. Practical Diabetes International. 2006;23(7):295–298. doi: 10.1002/pdi989. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf SH, Grol R, Hutchinson A, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Potential benefits, limitations, and harms of clinical guidelines. BMJ. 1999;318:527–530. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7182.527. Retrieved from http://www.bmj.com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang HL, Chen YC, Mao HC, Gau BS, Wang JK. Effect of a systematic discharge nursing plan on mothers' knowledge and confidence in caring for infants with congenital heart disease at home. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association. 2004;103(1):47–52. Retrieved from http://www.jfma-online.com. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz MC, Ozsoy SA. Effectiveness of a discharge-planning program and home visits for meeting the physical care needs of children with cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:243–253. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0650-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young B, Ward J, Salmon P, Gravenhorst K, Hill J, Eden T. Parents' experiences of their children's presence in discussions with physicians about leukemia. Pediatrics. 2011;127(5):1230–1238. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zebrack BJ, Block R, Hayes-Litton B, Embry L, Aguilar C, Meeske KA, et al. Cole S. Psychosocial service use and unmet need among recently diagnosed adolescent and young adult cancer patients. Cancer. 2013;119:201–214. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]