Abstract

Context

Whether subclinical hypothyroidism (SCH) is associated with cardiometabolic abnormalities is uncertain.

Objective

To examine diverse cardiometabolic biomarkers across euthyroid, SCH, and overt hypothyroidism (HT) in women free of cardiovascular disease (CVD).

Design

Cross-sectional adjusted associations for lipids, lipoprotein subclasses, lipoprotein insulin resistance score, inflammatory, coagulation, and glycemic biomarkers by ANCOVA for thyroid categories or TSH quintiles on a Women’s Health Study subcohort.

Setting

Outpatient.

Patients or Other Participants

Randomly sampled 3,914 middle-aged and older women for thyroid function analysis (thyroid-stimulating hormone [TSH], free T4), of whom 3,321 were not on lipid lowering therapy.

Intervention

None.

Main Outcome Measure

Associations of SCH and HT with cardiometabolic markers.

Results

Going from euthyroid to HT, the lipoprotein subclasse profiles were indicative of insulin resistance [respective values and p for trend]: larger VLDL size (nm)[51.5 (95%CI51.2, 51.8) to 52.9 (51.8, 54.1) p=0.001]; higher LDL particles concentration (nmol/L)[1283 (95%CI1267, 1299) to 1358 (1298, 1418) p=0.004] and smaller LDL size. There was worsening lipoprotein insulin resistance score from euthyroid 49.2 (95%CI 48.3, 50.2) to SCH 52.1 (95%CI 50.1, 54.0), and HT 52.1 (95%CI 48.6, 55.6), p for trend 0.008. Of the other biomarkers, SCH and HT were associated with higher hs-CRP and HbA1c. For increasing TSH quintiles results were overall similar.

Conclusions

In apparently healthy women, SCH cardiometabolic profiles indicated worsening insulin resistance and higher CVD risk markers compared with euthyroid individuals, despite similar LDL and total cholesterol. These findings suggest that cardiometabolic risk may increase early in the progression towards SCH and OH.

Keywords: Subclinical Hypothyroidism, Metabolomics, Lipoproteins, Inflammation, Coagulation, Insulin Resistance

Introduction

Subclinical hypothyroidism (SCH) and overt hypothyroidism (HT) are common diseases, affecting respectively 9.0% and 0.4% percent of the U.S. population(1), predominantly women. As thyroid function has multi-systemic effects, its derangement could affect a broad range of cardiometabolic pathways potentially related to clinical manifestations. However, the definition of normal thyroid function has been intensely debated, with some experts advocating for lowering the upper limit of normal for thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH)(2) and others for maintaining the current standard(3). In this regard, thyroid-related risk for incident type 2 diabetes (T2D) and cardiovascular disease (CVD) may impact the definition of TSH normality. In the one hand HT has been associated with incident T2D (4), on the other findings are mixed for CVD, especially in the grey zone of SCH (5–8).

The potential relationship of thyroid hypofunction with T2D and CVD may be mediated by abnormalities in lipids, lipoprotein subclasses, endothelial function, coagulation, inflammatory pathways, and insulin resistance (9, 10). To date, there have been inconsistent data regarding thyroid function across the spectrum of euthyroid to HT and its potential cardiometabolic mediators, both in direction and magnitude (11–13). Detailed assessment of thyroid function effects on these mediators/markers may have high population health implications, especially along the milder hypofunction spectrum within euthyroidism and SCH. Understanding the role of thyroid function in cardiometabolic pathways, may guide the clinically relevant definition of thyroid function and unveil potential targets for controlling related morbidity.

Therefore, in this study of apparently healthy middle-aged and older women, we examined thyroid function across the spectrum of euthyroid to HT in relation to cardiometabolic pathways represented by lipids, lipoproteins, inflammation, coagulation, glycemic, and insulin resistance biomarkers.

Methods

Study Design, Sample and Exposure Assessment

The sample comprised apparently healthy middle aged and older women at study entry of an ongoing prospective cohort, the Women’s Health Study (14). At enrollment, women gave written informed consent and completed questionnaires on demographics, anthropometrics, medical history, and lifestyle factors. Race was self-referred and body mass index (BMI) measured as weight in kilograms by squared height in meters. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Boston, Mass).

As our initial inclusion criteria were similar to the original protocol, women without cardiovascular disease or cancer, 28,024 participants with available stored frozen plasma at baseline were eligible to our study. From those, 3,914 women were randomly selected for thyroid function testing, and after excluding those on lipid lowering therapy and ineligible thyroid categories amounted to 3,321 individuals. Eligible categories based on the Roche Cobas assay recommendations by Atherotech Diagnostics Laboratory, Birmingham, AL were defined as follows: Euthyroid (thyroid-stimulating hormone [TSH]: 0.27 to 4.2 mlU/L and free thyroxine [FT4]: 0.93 to 1.7ng/dL), SCH (TSH >4.2 mlU/L and FT4: 0.93 to 1.7ng/dL) and hypothyroid (TSH > 4.2 mlU/L and FT4 <0.93ng/dL). Thyroid categories distribution was euthyrodism, 2,571 (77.4%); SCH, 573 (17.3%); and HT, 177 (5.3%). We performed additional analyses of TSH quintiles within normal FT4 individuals (0.93 to 1.7ng/dL), which includes only euthyroid and SCH, 3144 (94.7%).

Biomarker Assessment

Samples were obtained from stored blood in vapor-phase liquid nitrogen (−170°C) at the time of enrollment into the WHS and thawed for the following laboratory analysis. TSH and FT4 were measured at Atherotech Diagnostics Laboratory using the Roche Cobas e601 Analyzer with coefficients of variation (CVs) equal or lower than 8.7% and 6.6% respectively. In a laboratory certified by the NHLBI/CDC Lipid Standardization program, standard lipids were measured directly with reagents from Roche Diagnostics (Indianapolis, Ind)(15) and apolipoprotein (apo) B and A1 were measured with immunoturbidometric assays (DiaSorin, Stillwater, Minn). All measures had CVs of 5% or less and comprised: total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, apoB, apoA1. Lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] was measured by a commercially available immunoturbidimetric assay with reagents and calibrators from Denka Seiken with CV of 3.6% or lower. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy (LabCorp, previously LipoScience, Raleigh, NC) measured methyl terminal of lipoprotein subclasses and size of LDL, HDL, and very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) particles using a targeted metabolomics platform (NMR LipoProfile analysis by the LP3 algorithm) (16). This platform comprises concentrations of large, medium and small VLDL particles; large and small LDL particles; very large, large, medium, small and very small HDL particles; and average size of VLDL, LDL and HDL particles. As the distribution of small LDL particles is bimodal in this population, we analyzed this parameter separately in those with concentrations higher or lower than 164 nmol/L, which is the nadir between modes. The group with higher small LDL concentration will be referred as pattern B; and the lower as pattern A. Lipoprotein Insulin Resistance Score (LPIR) is part of the same panel, and is a weighted composite score of lipoprotein subclasses independently related to insulin resistance (17). It includes six parameters (respective maximum points and direction for more insulin resistance): VLDL size (32 points, larger size); large VLDL particles (22 points, increasing concentration); LDL size (6 points, smaller size); small LDL particles (8 points, increasing concentration); HDL size (20 points, smaller size); and large HDL particles (12 points, decreasing concentration). The summed score ranges from 0 to 100, and higher values indicate increasing insulin resistance (17).

The inflammation and coagulation biomarkers were: high sensitivity C reactive protein (hs-CRP) measured by a high sensitivity immunoturbidimetric assay on the Hitachi 917 autoanalyzer (Roche Diagnostics), with reagents and calibrators from Denka Seiken (18); fibrinogen measured by an immunoturbidimetric assay (Kamiya Biomedical, Seattle, Wash), homocysteine by an enzymatic assay (Catch Inc, Seattle, Wash); and soluble intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (sICAM-1) by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn). In addition, GlycA is a novel composite inflammatory biomarker of acute phase glycoproteins, mostly α1-acid glycoprotein, haptoglobin, α1-antitrypsin, α1-antichymotrypsin and transferrin (19). Their N-acetyl methyl group protons of the N-acetylglucosamine moieties located on their bi- tri- and tetraantennary branches were measured by magnetic resonance. This signal only arises from the N-acetylglucosamine units with β1→2 and β1→6 linkages on preceding mannose residue centered at 2.00 ± 0.01 ppm. GlycA signal was successfully deconvoluted from neighboring lipoprotein, majorly triglyceride concentration in very-low-density lipoprotein, with a CV of 4.3% (19). Hemoglobin A1c was measured by turbidimetric immunoinhibition on hemolyzed whole blood or packed red cells (Roche Diagnostics). Metabolic syndrome was classified by the presence of at least of three of the following: HbA1c ≥ 5.7 or diabetes history; blood pressure ≥ 130/85, hypertension diagnosis or treatment; BMI > 26.7 kg/m2; triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dL; or HDL-c < 50 mg/dL. As waist circumference was not measured until year 6 of follow up, baseline BMI was used instead. BMI baseline cut point was chosen according to the same percentile for BMI at year 6 as for 88 cm waist circumference at that moment.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive demographics of functional thyroid categories were displayed by percentages for categorical variables, and by mean (standard deviation [SD]) continuous variables. For univariable statistical comparisons, we used Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel for categorical variables and linear regression for trend for continuous variables.

We addressed the relationship of thyroid categories with each biomarker by adjusted linear regression analysis, with tests for linear trend, and pairwise comparisons adjusted by Bonferroni in the thyroid categories and TSH quintiles. For TSH quintiles, we tested linear trend across median TSH values within each quintile. For pairwise comparisons, the respective references were euthyroid or the bottom TSH quintiles. The covariables were age, race, household income, current smoking, systolic blood pressure, anti-hypertensive treatment, menopause status, and hormone replacement therapy. Skewed distributed variables were transformed by the natural logarithm (HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, Lp(a), large and small VLDL particles, small LDL particles (pattern B), hs-CRP, fibrinogen, homocysteine, and hemoglobin A1c) or by the square root (very large, large, medium, and small HDL particles) for better model fit; and then back transformed. We also conducted sensitivity analyses adjusted for BMI in order to address possible mediation of adiposity on thyroid function and metabolic abnormalities.

Finally, to assess the risk of having clinical metabolic syndrome across the thyroid categories or TSH quintiles, we applied logistic regression adjusted for age, race, smoking status, income, menopause status and hormone replacement therapy. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Compared to euthyroid women, those with SCH and HT were older, had higher BMI, greater prevalence of postmenopausal status, lower prevalence of current smoking, higher blood pressure, and greater prevalence of metabolic syndrome (Table 1). Noticeably, metabolic syndrome prevalence (25.4% on euthyroid to 39.6% on HT) and smoking (18.2% on euthyroid to 11.3% on HT) were largely different across thyroid categories.

Table 1.

Baseline Clinical Characteristics by Thyroid Function

| Euthyroid 77.4% (N=2571) | Subclinical Hypothyroid 17.3% (N=573) | Hypothyroid 5.3% (N=177) | p value for trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 56.5 (7.8) | 58.5 (8.3) | 60.4 (8.6) | <0.001 |

| Caucasian N (%) | 2451 (96.2%) | 558 (98.4%) | 174 (99.4%) | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.8 (5.0) | 26.1 (4.9) | 26.8 (4.9) | 0.005 |

| Income (Annual Household > 50K USD) N(%) | 1208 (50.0%) | 235 (43.0%) | 66 (38.6%) | <0.001 |

| Post-menopausal N (%) | 1575 (61.4%) | 402 (70.2%) | 134 (75.7%) | <0.001 |

| Hormone Replacement Treatment N (%) | 1092 (42.5%) | 260 (45.6%) | 66 (37.3%) | 0.843 |

| Diabetes N (%) | 95 (3.7%) | 27 (4.7%) | 10 (5.7%) | 0.105 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.0 (4.8 – 5.2) | 5.0 (4.8 – 5.2) | 5.1 (4.9 – 5.3) | <0.001 |

| Family History of Diabetes N (%) | 672 (26.1%) | 154 (26.9%) | 45 (25.4%) | 0.950 |

| Current Smoking N (%) | 496 (18.2%) | 55 (9.6%) | 20 (11.3%) | <0.001 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mmHg) | 125 (14) | 126 (14) | 128 (14) | <0.001 |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure (mmHg) | 77 (9) | 77 (9) | 79 (9) | 0.017 |

| Hypertension History N (%) | 694 (27.0%) | 167 (29.1%) | 56 (31.6%) | 0.108 |

| Metabolic Syndrome N (%) | 650 (25.4%) | 175 (30.7%) | 70 (39.6%) | <0.001 |

Legend: BMI (body mass index). Mean (standard deviation) and number (percentages).

P values: Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel for categorical variables and linear regression for linear trend for continuous variables.

In analyses that adjusted for age, race, household income, current smoking, systolic blood pressure, anti-hypertensive treatment, menopause status, and hormone replacement therapy; across thyroid categories there were no significant contrasts for total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, ApoA1 or Lp(a) (Table 2). On the other hand, going from euthyroid to SCH and HT, there was a pattern of increasing atherogenic dyslipidemia; namely, lower HDL cholesterol, higher triglycerides, higher ApoB concentrations, triglycerides/HDL-c ratio and apoB/Apoa1 ratios. Additional adjustment for BMI did not change the results.

Table 2.

Adjusted Standard Lipids and Apolipoprotein according to Functional Thyroid Categories

| Variable | Euthyroidism | Subclinical Hypothyroidism | Hypothyroidism | P for linear trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 213 (212, 215) | 212 (208, 215) | 218 (212, 224) | 0.621 |

| LDL Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 126 (124, 127) | 124 (121, 127) | 128 (123, 133) | 0.976 |

| HDL Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 51.6 (51.1, 52.2) | 49.3 (48.2, 50.4) † | 49.4 (47.4, 51.4) | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 122 (120, 125) | 133 (128, 139) † | 141 (131, 153) † | <.0001 |

| Triglycerides/HDL ratio | 2.4 (2.3, 2.4) | 2.7 (2.5, 2.9) † | 2.9 (2.6, 3.2) † | <.0001 |

| Apolipoprotein B (mg/dL) | 105 (104, 106) | 106 (104, 109) | 112 (107, 116) † | 0.011 |

| Apolipoprotein A1 (mg/dL) | 150 (149, 151) | 148 (146, 150) | 147 (143, 151) | 0.074 |

| ApoB/Apo A1 ratio | 0.73 (0.72, 0.74) | 0.74 (0.72, 0.76) | 0.80 (0.76, 0.84) † | 0.001 |

| Lipoprotein(a) (mg/dL) | 11.2 (10.6, 11.8) | 10.9 (9.7, 12.2) | 11.1 (9.1, 13.5) | 0.788 |

VLDL (very low density lipoprotein), IDL (Intermediate density lipoprotein), LDL (low density lipoprotein) and HDL (high density lipoprotein).

Linear regression across categories, adjustment covariates: age, race, household income, current smoking, systolic blood pressure, anti-hypertensive treatment, menopause status, and hormone replacement therapy. Least square means (95% confidence interval).

Pairwise comparison with euthyroid category, Bonferroni adjusted P value <0.050 signaled by †.

Additional adjustment for BMI did not yield change in p for trend across 0.05 thresholds.

On examining the lipoprotein particle distributions, there was a trend towards increasing insulin resistance going from euthyroid to SCH and HT (Table 3). In this order, there were increasing concentrations of large and medium VLDL particles, reflected by increasing VLDL size. Regarding LDL subclasses, from ET to HT there were increasing concentrations of total LDL particles and particularly of the small LDL (pattern B). This resulted in a smaller average LDL particle size. By contrast to differences seen in LDL particles, there were no HDL particle differences across thyroid categories. LPIR score reflected the overall profile of the lipoprotein subclasses, as indicated by greater lipoprotein insulin resistance going from a euthyroid mean LPIR of 49.2 (95%CI: 48.3, 50.2); to 52.1 in SCH (95%CI: 50.1, 54.0); and 52.1 in HT (95%CI: 48.6, 55.6)(p for trend 0.008). Additional adjustment for BMI neutralized differences for LDL particle size and LPIR signaled on table 3.

Table 3.

Adjusted Analysis for Lipoprotein Particle Concentration and Size According to Functional Thyroid Categories

| Variable | Euthyroidism | Subclinical Hypothyroidism | Hypothyroidism | P for linear trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VLDL Particles | ||||

| Total (nmol/L) | 61.8 (60.7, 62.8) | 62.7 (60.6, 64.9) | 65.2 (61.4, 69.1) | 0.084 |

| Large (nmol/L) | 2.5 (2.4, 2.6) | 2.7 (2.5, 3.0) | 3.1 (2.7, 3.6) † | 0.002 |

| Medium (nmol/L) | 16.9 (16.4, 17.3) | 17.8 (16.8, 18.7) | 19 (17.4, 20.7) † | 0.005 |

| Small (nmol/L) | 36.1 (35.2, 36.9) | 36.0 (34.3, 37.8) | 35.6 (32.6, 38.7) | 0.804 |

| Average Size (nm) | 51.5 (51.2, 51.8) | 52.3 (51.7, 53) | 52.9 (51.8, 54.1) † | 0.001 |

|

| ||||

| IDL Partcles | ||||

| Total (nmol/L) | 179 (175, 183) | 176 (167, 184) | 188 (174, 203) | 0.674 |

|

| ||||

| LDL Particles | ||||

| Total (nmol/L) | 1283 (1267, 1299) | 1319 (1285, 1353) | 1358 (1298, 1418) | 0.004 |

| Large (nmol/L) | 575 (564, 586) | 552 (529, 576) | 562 (520, 604) | 0.157 |

| Small pattern B 2225 (67.0%) | 668 (653, 684) | 734 (699, 770) † | 829 (759, 906) † | <.001 |

| Small Pattern A 1096 (33.0%) | 64.8 (63.0, 66.6) | 63.8 (60.0, 67.8) | 62.5 (56.5, 69.1) | 0.456 |

| Average Size (nm) | 21.1 (21.0, 21.1) | 21 (20.9, 21.1) | 21 (20.9, 21.1) | 0.024 * |

|

| ||||

| HDL Particles | ||||

| Total (nmol/L) | 37.4 (37.2, 37.7) | 37.3 (36.8, 37.8) | 37.1 (36.1, 38.0) | 0.431 |

| Large (umol/L) | 6.3 (6.2, 6.4) | 6.1 (5.8, 6.3) | 6.4 (5.9, 6.9) | 0.433 |

| Medium (umol/L) | 12.5 (12.3, 12.7) | 12.6 (12.1, 13) | 12.8 (12, 13.6) | 0.602 |

| Small (umol/L) | 18.7 (18.5, 18.9) | 19.1 (18.6, 19.5) | 18.1 (17.4, 18.9) | 0.904 |

| Average Size (nm) | 9.2 (9.2, 9.2) | 9.2 (9.1, 9.2) | 9.3 (9.2, 9.3) | 0.987 |

|

| ||||

| Lipoprotein Insulin Resistance Score (LP-IR) * | 49.2 (48.3, 50.2) | 52.1 (50.1, 54) † | 52.1 (48.6, 55.6) | 0.008 * |

VLDL (very low density lipoprotein), IDL (Intermediate density lipoprotein), LDL (low density lipoprotein) and HDL (high density lipoprotein).

Linear regression across categories, adjustment covariates: age, race, household income, current smoking, systolic blood pressure, anti-hypertensive treatment, menopause status, and hormone replacement therapy. Least square means (95% confidence interval).

Small LDL pattern A had 1096 individuals and small LDL pattern B group had 2225 individuals, which corresponded to 33.0% and 67.0% of all those with available small LDL particles.

Pairwise comparison with euthyroid category, Bonferroni adjusted P value <0.050 signaled by †.

Additional adjustment for BMI yield change in p for trend across 0.05 threshold when signaled by *.

For inflammatory and coagulation biomarkers, there were mixed results across thyroid categories (Table 4). Mean hs-CRP levels increased from 2.0 mg/L (95%CI: 1.9, 2.1) in euthyroid to 2.1 mg/L (95%CI: 1.9, 2.3) in SCH, and 2.4 mg/L (95%CI: 2.0, 2.8) in HT (p for trend 0.028), however null after BMI adjustment. By contrast, no significant differences were noted for the other inflammatory/coagulation biomarkers. Hemoglobin A1c levels were all below the upper limit of normality across thyroid categories, although a small but statistically significant difference was noted comparing HT with euthyroid.

Table 4.

Inflammatory, Coagulation and Metabolism Markers by Thyroid Function Classification

| Variable | Euthyroidism | Subclinical Hypothyroidism | Hypothyroidism | P for linear trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hs-CRP (mg/L) | 2.0 (1.9, 2.1) | 2.1 (1.9, 2.3) | 2.4 (2.0, 2.8) | 0.028 * |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 361 (358, 364) | 362 (356, 369) | 357 (345, 369) | 0.865 |

| Homocysteine (μmol/L) | 10.8 (10.7, 10.9) | 10.9 (10.6, 11.2) | 10.8 (10.3, 11.4) | 0.712 |

| s - ICAM (ng/ml) | 368 (365, 372) | 368 (360, 375) | 376 (363, 389) | 0.446 |

| GlycA (μmol/L) | 381 (378, 384) | 380 (375, 386) | 381 (371, 391) | 0.924 |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.1 (5.1, 5.1) | 5.1 (5.1, 5.2) | 5.2 (5.1, 5.3) † | 0.011 |

hsCRP (high sensitivity C reactive protein) and s-ICAM (soluble intercellular adhesion molecule).

Linear regression across categories, adjustment covariates: age, race, household income, current smoking, systolic blood pressure, anti-hypertensive treatment, menopause status, and hormone replacement therapy. Least square means (95% confidence interval).

Pairwise comparison with euthyroid category, Bonferroni adjusted P value <0.050 signaled by †.

Additional adjustment for BMI yield change in p for trend across 0.05 threshold when signaled by *.

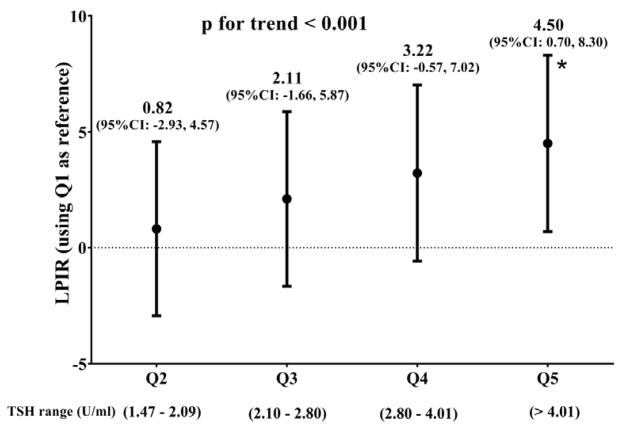

On analysis restricted to euthyroid and SCH women (Supplementary Tables 1, 2 and 3), TSH quintile values were mostly within the normal range (i.e., euthyroid). Only the top TSH quintile had individuals in the SCH range, which comprised 91.0 % (573 women) of the top quintile. Similar to the analyses for thyroid categories, across increasing TSH quintiles the overall profile was consistent with worsening dyslipidemia and dyslipoproteinemia. By contrast to the analysis according to thyroid categories, we noted that there were decreasing concentrations of large HDL particles and increasing concentrations of small HDL particles from the bottom to the top quintile, reflected in smaller HDL particles size. Of note, increasing TSH quintiles presented quite linear LPIR increments (Supplementary Table 2, Figure 1).

Figure 1. Lipoprotein insulin resistance (LPIR) according to TSH quintiles.

LPIR score difference for TSH quintiles (Q) versus the 1st TSH Q along euthyroid and SCH.

Linear regression for median TSH across categories, adjustment covariates: age, income, current smoking, race, household income, systolic blood pressure, high blood pressure treatment, menopause status and hormone replacement therapy.

P for trend for median TSH values within each quintile.

* Bonferroni adjusted p value = 0.010 for 5th quintile versus the 1st quintile.

Regarding metabolic syndrome, there was increasing prevalence from ET to HT (p<0.001). Compared with euthyroid, SCH and HT adjusted odds ratio for metabolic syndrome were respectively 1.37 (95%CI: 1.08, 1.73) and 1.88 (95% CI: 1.30, 2.72) (p for linear trend <0.001). Increasing TSH within euthyroid and SCH range had higher odds ratio for metabolic syndrome in reference to the bottom quintile (p for trend 0.001) (supplementary table 4), in which the top quintile had an odds of 1.49 (95% CI, 1.10, 2.01).

Discussion

In this population of apparently healthy middle-aged and older women, individuals with SCH and HT had differences in the lipid and lipoprotein subclass profile that indicated worsening insulin resistance and higher cardiometabolic risk compared with euthyroid individuals, despite having similar LDL-cholesterol and total cholesterol. Of the other biomarkers, just hs-CRP and HbA1c were associated with SCH and HT. For TSH quintiles mostly within the normal range, lipids and lipoproteins results for TSH quintiles were generally similar but null for other biomarkers. Hence, progressive thyroid hypo-function was associated with insulin resistant and pro-atherogenic lipids and lipoproteins profile in a graded manner, with potential clinical consequences.

This study adds to the literature by describing the graded relationship of progressive thyroid hypofunction, even within the “normal” range of euthyroidism, as manifested by increasing lipoprotein insulin resistance. For inflammatory, coagulation and glucose metabolism biomarkers, just hs-CRP and HbA1c were higher across euthyroid to HT spectrum, but none of those biomarkers along TSH spectrum within euthyroid and SCH. Given that, the current classification of euthyroidism, SCH, and HT may be less sensitive to earlier thyroid disturbances within euthyroidism, in particular in relation to insulin resistance related dyslipidemia/dyslipoproteinemia.

We studied an apparently healthy population woman who were predominantly insulin sensitive (89% with hemoglobin A1c < 5.7%). Should the progressive insulin resistance related dyslipidemia along thyroid hypofunction have any impact on clinical outcomes as incident T2D or CVD, even small relative risk may have a high population impact. This is due to the very broad generalizability of our findings as euthyroid and SCT women comprise 97.3% of middle aged women in the United States (1). Previous studies have found strong associations for LPIR with incident T2D (20, 21), and also in the current WHS study population (22). The robust association between thyroid and LPIR may be a pathophysiological pathway of its hypofunction towards T2D. For CVD, despite neutral risk with increasing TSH levels within the euthyroid range (23), the role of SCH is still open to debate (24). In these contexts, our findings suggest that lipids and lipoproteins are potentially important mediators for therapeutic targeting beyond thyroxine replacement.

The literature regarding euthyroid and hypothyroid relationships with the panel of biomarkers that we examined is rather mixed. For standard lipids, the association of thyroid hypofunction with low HDL cholesterol and high triglycerides have been shown in a population study with more than 30,000 euthyroid people (25). On the other hand, in the Framingham Offspring population, there was no association between TSH and either HDL cholesterol or triglycerides (11). Additionally, in the two studies above mentioned there was higher total and LDL cholesterol for increasing TSH. However, it is not possible to infer to which extent population profile and adjustment models explain the divergent results.

Regarding lipoproteins subclasses, Hernadez-Mijares found, similarly to the current study, increasing proportion of LDL pattern B profile patients from euthyroid to SCH(26). However, they did not address LDL subclasses across the euthyroidism range. By contrast, Pearce et al (11), found lipoprotein subclasses profile totally opposite to the current results, towards insulin sensitivity in analyses adjusted for age, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, anti-hypertensive treatment, diabetes, smoking, HDL cholesterol and triglycerides. Nevertheless, thyroid hypofunction seems to equally affect HDL cholesterol, triglycerides and lipoproteins subclasses towards insulin resistance profile. After further adjusting our current models for HDL and triglycerides, lipoproteins subclasses profile on SCH and HT were null or compatible with insulin sensitiveness (data not shown), similarly to Pearce. Thus, collinear effect of thyroid hypofunction on HDL, triglycerides and lipoproteins subclasses could justify those paradoxical results.

Regarding inflammation, in our study SCH and HT were associated with high hs-CRP, but not after adjustment for BMI. Lee et al also found no association of thyroid function with hs-CRP adjusted for BMI(27), which raises the hypothesis of BMI mediation between thyroid and inflammation. Also, Hueston et al did not find association of SCH with hs-CRP or homocysteine levels in a US adult population (NHANES) (28). However, the authors did not adjust for smoking, which is positively associated with inflammation (29) and inversely with hypothyroidism (30). This is corroborated by the fact that in our study there was no hs-CRP difference for euthyroid, SCH and HT when smoking was not adjusted for (data not shown). Regarding homocysteine, Zhou et al also did not find association with SCH but positive one with HT (13). Nevertheless, in that meta-analysis, there was evidence for study heterogeneity and publication bias. Fibrinogen, a marker of hypercoagulation state, was similarly not associated with hypothyroidism in other studies (31, 32), despite their limited adjustment for confounders. Soluble ICAM-1, associated with initiation and formation of atherosclerosis in animal models (33), and GlycA, a novel composite marker of acute phase glycoproteins signaling chronic inflammation (19), were both not associated with thyroid hypofunction in the current study. To the best of our knowledge, the association of euthyroidism, SCH and HT with s-ICAM-1 and GlycA has not been reported previously. Finally, reverse causation for thyroid function and inflammation should be considered. The most common cause for thyroid hypofunction is Hashimoto’s disease (34) that may confound the association by its inflammatory pathophysiology. We could not address this hypothesis due to unavailable thyroid peroxidase antibodies.

Underlying Mechanisms

Thyroid hormones act as modulators of cholesterol synthesis and degradation through key enzymes. One of the main mechanisms is the stimulus of thyroid hormones over sterol regulatory element-binding proteins 2 (SREBP-2), which in turn induces LDL receptor genes expression (35). However, it was shown that the association of hypothyroidism and higher LDL cholesterol levels is present only in insulin resistant subjects (36). Indeed, the lack of LDL cholesterol differences could be explained by our insulin sensitive study population (low hemoglobin A1c levels). Hypothyroidism has also been associated with lower catabolism of lipid rich lipoproteins by lipoprotein lipase (37), hepatic lipase (38), and decreased activity of cholesterol ester transfer protein(39) that mediates exchanges of cholesteryl esters of HDL particles with triglycerides-rich LDL and VLDL particles. These mechanisms might explain the relationship of thyroid hypofunction with atherogenic and insulin resistant lipids and lipoproteins abnormalities.

Finally, milder differences noted in hemoglobin A1c compared with LPIR across thyroid categories may be explained by the earlier effects of insulin resistance on lipoproteins metabolism than on glucose metabolism(40).

Strengths and Limitations

Our study has a relatively large sample of apparently healthy middle aged and older women free of cardiovascular disease, which may limit generalizability to men or higher risk woman. The study design is cross-sectional, which limits any causal inferences. Additionally, there is no information about duration of thyroid dysfunction as well as thyroid hormone replacement and/or thyroid modulating drugs. In spite of that, these factors may have limited impact given our sample is composed of apparently healthy women on enrollment. We had an unprecedented comprehensive set of biomarkers, which offered a broad perspective on pathways between thyroid hypofunction and cardiometabolic risk. Despite the large number of biomarkers examined, insulin resistance is the common biological mechanism that is likely underlying the overall findings. Therefore, it is improbable that our results were due to chance alone.

Conclusion

In this large population of apparently healthy women, individuals with SCH had differences in their biomarker profile that indicated worsening lipoprotein insulin resistance and higher cardiometabolic risk compared with euthyroid individuals, despite having similar LDL-C and total cholesterol levels. These findings suggest that cardiometabolic risk may increase early in the progression towards SCH and OH.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

P.H.N. Harada was funded by the Lemann Foundation. The Women’s Health Study was funded by grants CA047988, HL043851, HL080467, HL099355, and UM1 CA182913. Additional funding was received from a charitable gift from the Molino Family Trust. Atherotech Diagnostics provided an institutional grant to the Brigham and Women’s Hospital for measuring the thyroid assays.

Dr. Mora received funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institute of Health (HL 117861).

Samia Mora and Paulo H. N. Harada as the guarantors of this manuscript, state that all of the authors approved submission of the manuscript. Both had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the analyses. The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors only. Our detailed financial disclosures are listed in the manuscript.

Footnotes

Women’s Health Study URL http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct/show/NCT00000479, unique identifier NCT00000479

Disclosure Summary: P.H.N.Harada, Julie E. Buring and N.R.Cook have nothing to disclose. M. Cobble was CMO at Atherotech Diagnostics Lab 7/09-2/16, and is Advisory/Research/Speaker for Amarin, Amgen, Astra Zeneca, Janssen, Sanofi, Regeneron. K. Kulkarni was employee of Atherotech Diagnostics. S. Mora received research grant support from Atherotech Diagnostics and NHLBI (HL 117861); is consultant to Lilly, Pfizer, Amgen, Quest Diagnostics, and Cerenis Therapeutics; and is co-inventor on a patent on the use of NMR-measured GlycA for predicting risk of colorectal cancer.

References

- 1.Canaris GJ, Manowitz NR, Mayor G, Ridgway EC. The Colorado thyroid disease prevalence study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:526–534. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.4.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wartofsky L, Dickey RA. The evidence for a narrower thyrotropin reference range is compelling. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:5483–5488. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Surks MI, Goswami G, Daniels GH. The thyrotropin reference range should remain unchanged. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:5489–5496. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gronich N, Deftereos SN, Lavi I, et al. Hypothyroidism is a Risk Factor for New-Onset Diabetes: A Cohort Study. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:1657–1664. doi: 10.2337/dc14-2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walsh JP, Bremner AP, Bulsara MK, et al. Subclinical thyroid dysfunction as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:2467–2472. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.21.2467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Razvi S, Weaver JU, Vanderpump MP, Pearce SH. The incidence of ischemic heart disease and mortality in people with subclinical hypothyroidism: reanalysis of the Whickham Survey cohort. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:1734–1740. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.LeGrys VA, Funk MJ, Lorenz CE, et al. Subclinical hypothyroidism and risk for incident myocardial infarction among postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:2308–2317. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-4065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cappola AR, Fried LP, Arnold AM, et al. Thyroid status, cardiovascular risk, and mortality in older adults. JAMA. 2006;295:1033–1041. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.9.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biondi B, Klein I. Hypothyroidism as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Endocrine. 2004;24:1–13. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:24:1:001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maratou E, Hadjidakis DJ, Kollias A, et al. Studies of insulin resistance in patients with clinical and subclinical hypothyroidism. Eur J Endocrinol. 2009;160:785–790. doi: 10.1530/EJE-08-0797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pearce EN, Wilson PW, Yang Q, Vasan RS, Braverman LE. Thyroid function and lipid subparticle sizes in patients with short-term hypothyroidism and a population-based cohort. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:888–894. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asvold BO, Vatten LJ, Nilsen TI, Bjoro T. The association between TSH within the reference range and serum lipid concentrations in a population-based study. The HUNT Study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2007;156:181–186. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou Y, Chen Y, Cao X, Liu C, Xie Y. Association between plasma homocysteine status and hypothyroidism: a meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7:4544–4553. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee IM, Cook NR, Gaziano JM, et al. Vitamin E in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer: the Women’s Health Study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;294:56–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mora S, Rifai N, Buring JE, Ridker PM. Comparison of LDL cholesterol concentrations by Friedewald calculation and direct measurement in relation to cardiovascular events in 27,331 women. Clin Chem. 2009;55:888–894. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.117929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jeyarajah EJ, Cromwell WC, Otvos JD. Lipoprotein particle analysis by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Clinics in laboratory medicine. 2006;26:847–870. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shalaurova I, Connelly MA, Garvey WT, Otvos JD. Lipoprotein insulin resistance index: a lipoprotein particle-derived measure of insulin resistance. Metabolic syndrome and related disorders. 2014;12:422–429. doi: 10.1089/met.2014.0050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ridker PM, Rifai N, Rose L, Buring JE, Cook NR. Comparison of C-reactive protein and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in the prediction of first cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1557–1565. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Otvos JD, Shalaurova I, Wolak-Dinsmore J, et al. GlycA: A Composite Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Biomarker of Systemic Inflammation. Clin Chem. 2015;61:714–723. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2014.232918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mackey RH, Mora S, Bertoni AG, et al. Lipoprotein particles and incident type 2 diabetes in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:628–636. doi: 10.2337/dc14-0645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dugani SB, Akinkuolie AO, Paynter N, et al. Association of Lipoproteins, Insulin Resistance, and Rosuvastatin With Incident Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1:136–145. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.0096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harada PH, Dugani S, Akinkuolie A, Pradhan A, Mora S. Lipoprotein Insulin Resistance Score and the Risk of Incident Diabetes: The Women’s Health Study. American Heart Association; Orlando, FL: 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Åsvold BO, Vatten LJ, Bjøro T, et al. Thyroid Function Within the Normal Range and Risk of Coronary Heart Disease: An Individual Participant Data Analysis of 14 Cohorts. JAMA Intern Med. 2015 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodondi N, Bauer DC. Subclinical hypothyroidism and cardiovascular risk: how to end the controversy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:2267–2269. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asvold BO, Vatten LJ, Nilsen TI, Bjøro T. The association between TSH within the reference range and serum lipid concentrations in a population-based study. The HUNT Study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2007;156:181–186. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hernández-Mijares A, Jover A, Bellod L, et al. Relation between lipoprotein subfractions and TSH levels in the cardiovascular risk among women with subclinical hypothyroidism. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2013;78:777–782. doi: 10.1111/cen.12064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee WY, Suh JY, Rhee EJ, et al. Plasma CRP, apolipoprotein A-1, apolipoprotein B and Lpa levels according to thyroid function status. Arch Med Res. 2004;35:540–545. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hueston WJ, King DE, Geesey ME. Serum biomarkers for cardiovascular inflammation in subclinical hypothyroidism. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2005;63:582–587. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2005.02388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bermudez EA, Rifai N, Buring JE, Manson JE, Ridker PM. Relation between markers of systemic vascular inflammation and smoking in women. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89:1117–1119. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02284-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Asvold BO, Bjoro T, Nilsen TI, Vatten LJ. Tobacco smoking and thyroid function: a population-based study. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1428–1432. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.13.1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mazur P, Sokołowski G, Hubalewska-Dydejczyk A, Płaczkiewicz-Jankowska E, Undas A. Prothrombotic alterations in plasma fibrin clot properties in thyroid disorders and their post-treatment modifications. Thromb Res. 2014;134:510–517. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2014.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Toruner F, Altinova AE, Karakoc A, et al. Risk factors for cardiovascular disease in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism. Adv Ther. 2008;25:430–437. doi: 10.1007/s12325-008-0053-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakashima Y, Raines EW, Plump AS, Breslow JL, Ross R. Upregulation of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 at atherosclerosis-prone sites on the endothelium in the ApoE-deficient mouse. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:842–851. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.5.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pearce EN, Farwell AP, Braverman LE. Thyroiditis. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2646–2655. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra021194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shin DJ, Osborne TF. Thyroid hormone regulation and cholesterol metabolism are connected through Sterol Regulatory Element-Binding Protein-2 (SREBP-2) J Biol Chem. 2003;278:34114–34118. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305417200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bakker SJ, ter Maaten JC, Popp-Snijders C, et al. The relationship between thyrotropin and low density lipoprotein cholesterol is modified by insulin sensitivity in healthy euthyroid subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:1206–1211. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.3.7324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lithell H, Boberg J, Hellsing K, et al. Serum lipoprotein and apolipoprotein concentrations and tissue lipoprotein-lipase activity in overt and subclinical hypothyroidism: the effect of substitution therapy. Eur J Clin Invest. 1981;11:3–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1981.tb01758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Valdemarsson S, Nilsson-Ehle P. Hepatic lipase and the clearing reaction: studies in euthyroid and hypothyroid subjects. Horm Metab Res. 1987;19:28–30. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1011728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tan KC, Shiu SW, Kung AW. Effect of thyroid dysfunction on high-density lipoprotein subfraction metabolism: roles of hepatic lipase and cholesteryl ester transfer protein. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:2921–2924. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.8.4938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sorensen LP, Sondergaard E, Nellemann B, et al. Increased VLDL-triglyceride secretion precedes impaired control of endogenous glucose production in obese, normoglycemic men. Diabetes. 2011;60:2257–2264. doi: 10.2337/db11-0040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.