Abstract

Th2 immunity and allergic immune surveillance play critical roles in host responses to pathogens, parasites and allergens. Numerous studies have reported significant links between Th2 responses and cancer, including insights into the functions of IgE antibodies and associated effector cells in both anti-tumour immune surveillance and therapy. The interdisciplinary field of AllergoOncology was given Task Force status by the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology in 2014. Affiliated expert groups focus on the interface between allergic responses and cancer, applied to immune surveillance, immunomodulation and the functions of IgE-mediated immune responses against cancer, to derive novel insights into more effective treatments. Co-incident with rapid expansion in clinical application of cancer immunotherapies, here we review the current state-of-the-art and future translational opportunities, as well as challenges in this relatively new field. Recent developments include improved understanding of Th2 antibodies, intra-tumoural innate allergy effector cells and mediators, IgE-mediated tumour antigen cross-presentation by dendritic cells, as well as immunotherapeutic strategies such as vaccines and recombinant antibodies, and finally, the management of allergy in daily clinical oncology. Shedding light on the cross-talk between allergic response and cancer is paving the way for new avenues of treatment.

Introduction

It has been recognized that tumours manipulate immune responses. On the other hand, the overall immune competence of the host could critically determine immune surveillance against cancer and the clinical course. Allergy and atopy are characterized by a systemic bias to Th2 immunity, which may exert a potential influence on cancer development. In fact, allergy and oncology may represent two opposite concepts: whereas immune tolerance is desired in allergy, it is detrimental in cancer. Hence, the establishment of a Task Force on AllergoOncology (AO) within the Immunology Section of EAACI is timely and appropriate. The aim of the Task Force is to connect basic scientists interested in Th2 immunity and cancer with clinical oncologists and to support an interdisciplinary exchange to advance knowledge and understanding of immune responses in both fields. At present, this is the first AO platform worldwide.

Previous AO activities have included a first concerted paper (1), international conferences, the book “IgE and Cancer” (2) and a Symposium-in-Writing on AllergoOncology (3).

A Pre-Task Force Meeting was held at the EAACI annual conference in Copenhagen in 2014, leading to the establishment of the Task Force within the Interest Group of Immunology, with its first business meeting in Barcelona in 2015. The primary objectives of the Task Force were confirmed: to serve as an interface between the disciplines of oncology and allergy, covering: (i) basic, (ii) translational, (iii) epidemiological and (iv) clinical research, including allergy problems in clinical oncology, as well as (v) mechanisms of tumour-induced immune modulation and (vi) novel vaccination and immunotherapy approaches harnessing IgE functions to target cancer.

The goal of this position paper is to provide an update on developments in the AllergoOncology field since 2008 (1). We therefore aimed to review: (i) clinical, mechanistic and epidemiological insights into Th2 immune responses in cancer, (ii) current immunologic markers with a complementary role in allergy and cancer, (iii) correlation of these markers with the progress of malignant diseases, and (vi) an update on how oncologists can manage allergic reactions to cancer therapeutics.

The different topics, were drafted by subgroups of the Task Force, and further discussed, developed and compiled during a meeting in Vienna in 2015. The position paper was thereafter recirculated, critically appraised, and the final version approved by all Task Force members.

Epidemiology

The epidemiologic association between allergy and cancer risk has been summarized in meta-analyses, with inverse associations reported for several cancers including glioma, pancreatic cancer, and childhood leukaemia (4, 5). The majority of previous studies have relied on self-reported ascertainment of allergic status, being typically limited, retrospective, and associated with potential biases. Emerging evidence comes from prospective studies. based on self-reported allergy history which have reported inverse associations in studies of colorectal (6), but not hematopoietic or prostate cancer (7, 8). A large-scale study based on hospital discharge records reported an inverse association between allergy/atopy of at least 10 years in duration and incidence of brain cancer (RR (Relative Risk) = 0.6, 95% CI (Confidence Interval) 0.4–0.9) in a cohort of 4.5 million men (9). Nested case-control studies reported inverse associations between borderline or elevated total IgE (10) or respiratory-specific IgE and glioma risk (10, 11). Serum total and allergen-specific IgE provided evidence of inverse associations with the development of melanoma, female breast cancer, gynaecological malignancies and also glioma (12). Findings at other cancer sites are unclear (13–15). One study reported an inverse trend between increasing blood eosinophil count and subsequent colorectal cancer risk (16). Another study reported that serum concentrations of soluble CD23/FcεRII (sCD23) and soluble CD30 (sCD30) were positively associated with risk of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (17). Several studies have examined associations with SNPs in allergy-related genes with significant associations between SNPs in FCER1A, IL10, ADAM33, NOS1 and IL4R genes and glioma risk reported in one recent study which requires further replication (18).

Further research in large-scale prospective studies using validated measures of self-reported allergy history and/or biomarkers of allergy is needed, including repeated evaluations over time, sufficient latency with respect to the developing tumour, and detailed data on potentially confounding variables (19).

Th2-associated antibodies in cancer

Although studied for decades, our understanding of different immunoglobulin classes in cancer biology is still limited. IgG antibodies are the predominant antibody class for passive immunotherapy. Recent findings elucidated that the tumour microenvironment may specifically promote less potent immunoglobulin isotypes such as IgG4 (20). Furthermore, IgG and IgE free light chains (FLC) engaging mast cells could reduce tumour development in vivo (21). Furthermore, by promoting specific phenotypes of tumour infiltrating leucocytes and through inducing a higher expression of inhibitory Fcγ receptors, malignant cells can evade humoral immune responses and counteract the anti-tumour effector functions of therapeutic IgG antibodies (22).

A preliminary study has reported that both IgE and IgG4 specific towards two of three cancer antigens are elevated in cancer patients compared with healthy volunteers (23). The phenomenon that anti-cancer therapies, such as alkylating agents and hormone-based chemotherapies affect circulating total and specific IgE levels has also been reported (24), however, any implications on clinical course require further investigations. A number of these studies also provide evidence in support of Th2 humoral immunity to derive new tools for malignant disease monitoring and prognosis. Interestingly, IgE antibodies isolated from pancreatic cancer patients mediate antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) against cancer cells (25). Furthermore, higher levels of polyclonal IgE in non-allergic individuals are directly correlated with lower disease incidence and higher survival in multiple myeloma in a clinical study (26). Collectively, these studies point to important roles for Th2-associated antibodies and tumour immune surveillance.

In situ expression of AID and potential insights into antibody isotype expression in cancer

The enzyme cytidine deaminase (AID) which is responsible for converting cytidine to uracil and thereby induces targeted damage to DNA, is a key driver of immunoglobulin (Ig) somatic hypermutation (SHM) events and class switch recombination (CSR) processes that give rise to IgG, IgA or IgE. On the other hand, AID has multifaceted functions linking immunity, inflammation and cancer (27).

AID is thought to be expressed predominantly by germinal centre (GC) B cells within secondary lymphoid organs. However, studies on local autoimmunity, transplant rejection, and tissues exposed to chronic inflammation point to the capacity of B lymphocytes to form GC-like ectopic structures outside of secondary lymphoid tissues (27, 28), which is now also demonstrated within benign and malignant tissues. Class switching of local GC-derived B cells to different isotypes may have a profound influence on local immune responses and on disease pathobiology. However, whether tumour microenvironments support direct class switching to IgE remains unclear, although some evidence from animal models point to IgE production at early stages of carcinogenesis (29). Remarkably, local follicle-driven B cell-attributed immune responses may be either positively- or negatively-associated with clinical outcomes of cancer patients (30, 31).

IgE receptor expression on immune cells and epithelial cells

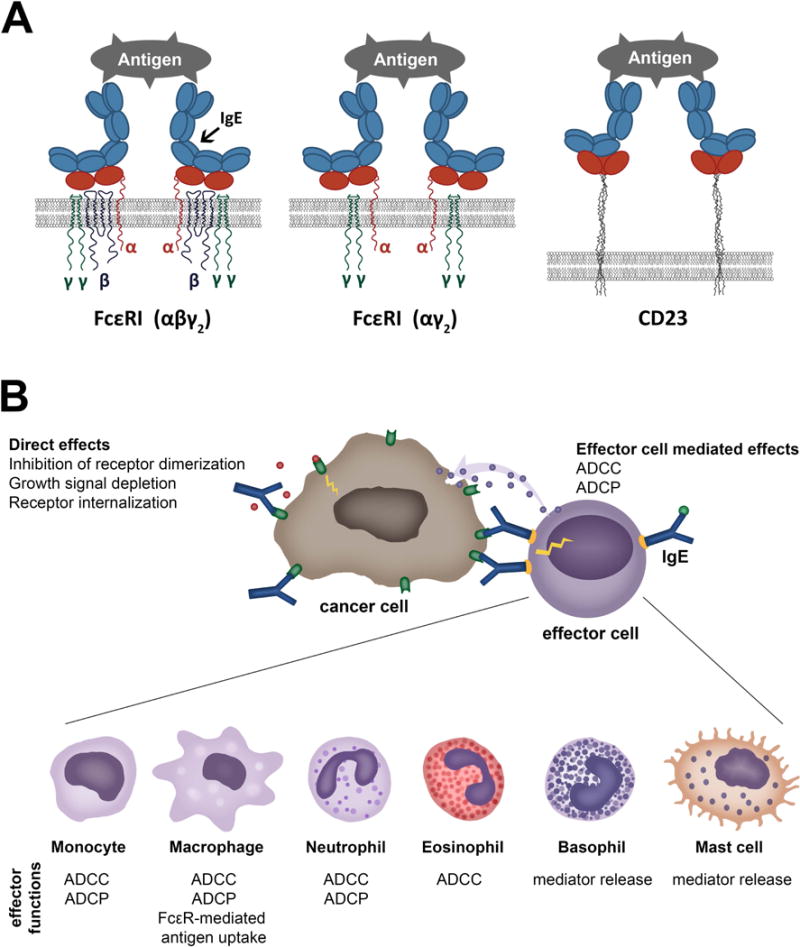

The high affinity receptor FcεRI tetrametic form αβγ2 is expressed on mast cells and basophils. The trimeric form of the high affinity receptor FcεRI (αγ2), and the low affinity receptor CD23/FcεRII (b form) (Figure 1A) on human monocytes and macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs), eosinophils, platelets and neutrophils (32). The `a` form of CD23/FcεRII is also expressed by subsets of B cells (33). IgE cell surface receptors FcεRI, FcεRII/CD23 (Figure 1A) and also the soluble IgE receptors Galectin-3 and -9 are expressed not only by hematopoietic cells, but also by non-hematopoetic cells including epithelia (Table 1).

Figure 1. Cell surface IgE receptors and IgE-mediated direct and indirect effects.

A. Cartoon of IgE binding to its cell surface receptors. IgE binds to tetrameric (αβγ2) (left) and trimeric forms (αγ2) (middle) of FcεRI through the extracellular domain of the alpha (α) chain of the receptor. The low-affinity receptor CD23 trimer binds IgE through recognition of the lectin domain (right).

B. Direct and cell-mediated effects of anti-tumour IgE. Like IgG antibody therapies, IgE targeting tumour antigens can exert direct effects through recognising the target antigen, such as interference with signalling, resulting in growth inhibition. IgE can also bind via IgE receptors (FcεRI or FcεRII/CD23) to a specific repertoire of effector cells (illustrated in the bottom panel). These interactions may lead to effector functions against tumour cells, such as antibody-dependent cell-mediated phagocytosis (ADCP) or cytotoxicity (ADCC), or mediator release. Crosslinking of IgE is required for effector cell activation, whereas soluble tumour antigens expressing only a single epitope do not trigger IgE cross-linking on the surface of effector cells.

Table 1.

Expression of IgE binding structures on hematopoietic or non- hematopoietic cells in humans.

| IgE binding structure | Receptor composition/splice variants | Expression on hematopoietic cells | Expression on non-hematopoietic cells |

|---|---|---|---|

| High affinity IgE receptor/FcεRI | Tetrameric receptor αβγ2 | Mast cells, basophils Kraft S, Kinet JP. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007 May;7(5):365–78. |

- |

| Trimeric receptor αγ2 | Mast cells, basophils Kraft S, Kinet JP. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7(5):365–78. Monocytes, macrophages Boltz-Nitulescu G, et al. Monogr Allergy. 1983;18:160–2. Spiegelberg HL. Int Rev Immunol. 1987;2(1):63–74. Dendritic cells Novak N, et al. J Clin Invest. 2003; 111(7):1047–56. Bieber T, et al. J Exp Med. 1992; 175(5):1285–90. Allam JP, et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003; 112(1):141–8. Bannert C, et al. PLoS One. 2012; 7(7):e42066. Yen EH, et al. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010; 51(5):584–92. Eosinophils Gounni AS et al. Nature. 1994, 367(6459):183–6. Platelets Hasegawa S et al. Blood. 1999; 93(8):2543–51. |

Small intestinal and colonic epithelial

cells Untersmayr et al. PLoS One. 2010 Feb 2;5(2):e9023. |

|

| α chain | Neutrophils Dehlink et al, PLoS One. 2010, 5(8):e12204. Alphonse MP et al. PLOS one 2008; 3(4):e1921 |

Paneth cells Untersmayr E et al. PLoS One. 2010;5(2):e9023. Smooth muscle cells Gounni AS et al. J Immunol. 2005;175(4):2613–21. |

|

| Low affinity IgE receptor/FcεRII/CD23 | CD23a isoform | Antigen-activated B

cells Reviewed in: Gould HJ, Sutton BJ. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(3):205–17. doi: 10.1038/nri2273. |

|

| CD23b isoform | B cells Yukawa K, et al. J Immunol. 1987;138(8):2576–80. Monocytes, macrophages Vercelli D et al. J Exp Med. 1988;167(4):1406–16. Pforte A et al. J Exp Med. 1990;171(4):1163–9. Eosinophils Capron M et al. Chem Immunol. 1989;47:128–78. Platelets Capron M et al. J Exp Med. 1986;164(1):72–89. Dendritic cells Bieber T et al. J Exp Med. 1989;170(1):309–14. |

Small intestinal and colonic epithelial

cells Kaiserlian D et al. Immunology. 1993 Sep;80(1):90–5. |

|

| Galectins | Galectin 3 | Monocytes, macrophages Liu FT et al. Am J Pathol. 1995;147(4):1016–28. Neutrophils Truong MJ, et al. J Exp Med. 1993;177(1):243–8. Eosinophils Truong MJ et al. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23(12):3230–5. Basophils and mast cells Craig SS et al. Anat Rec. 1995;242(2):211–9. Dendritic cells Brustmann H. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2006;25(1):30–7. Smetana K et al. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;66(4):644–9. |

Gastric cells Fowler M et al. Cell Microbiol. 2006;8(1):44–54. Small intestinal, colonic, corneal, conjunctival and olfactory epithelial cells, epithelial cells of kidney, lung, thymus, breast, prostate Dumic J, et al. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1760(4):616–35. Jensen-Jarolim E et al. Eur. J. of Gastroenterology & Hepatol. 2002;14(2):145–52. Uterine epithelial cells von Wolff M et al. Mol Hum Reprod. 2005;11(3):189–94. Fibroblasts Openo KP et al. Exp Cell Res. 2000;255(2):278–90. Chondrocytes and osteoblasts Janelle-Montcalm A et al. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9(1):R20. Osteoclasts Nakajima K et al. Cancer Res. 2016;76(6):1391–402. Keratinocytes Konstantinov KN et al. Exp Dermatol. 1994;3(1):9–16. Neural cells Pesheva P et al. J Neurosci Res. 1998; 54(5):639–54. |

| Galectin 9 | T-cells Chabot S et al. Glycobiology. 2002 Feb;12(2):111–8. Monocytic cells, macrophages Harwood NM et al. J Leukoc Biol. 2016; 99(3):495–503. Mast cells Wiener Z et al. J Invest Dermatol. 2007; 127(4):906–14. |

Intestinal epithelial cells Chen X et

al. Allergy.

2011;66(8):1038–46. M-cells Pielage JF et al. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39(10):1886–901. Nasal polyp fibroblasts Park WS et al. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;411(2):259–64. Endometrial epithelial cells Shimizu Y et al. Endocr J. 2008;55(5):879–87. Endothelial cells Imaizumi T et al. J Leukoc Biol. 2002; 72(3):486–91. |

Depending on the nature and distribution of IgE receptors, different functions might be envisaged. Galectin-3 is well recognized for its contribution to tumour progression and metastasis development (34), while galectin-9 seems to have anti-proliferative effects (35, 36). The trimeric FcεRI(αγ2) showed membranous and cytoplasmic expression in intestinal epithelial cells and a prominent FcεRI α-chain expression was also found in the Paneth cells of patients with cancer of the proximal colon. In the same study, a similar distribution could be observed in tissues from patients with gastrointestinal inflammation, whereas no expression was observed in healthy controls (37).

It is important to note that cell surface-expressed IgE binding structures may have different effector functions compared with their secreted forms such as soluble FcεRIα chain (38) and galectin-3 (39) in cancer, which may be of key functional importance.

Effector cells in allergy and cancer

Mast cells

Mast cells are perhaps the most classical effector cells of IgE (Figure 1B). Their presence at the periphery, but also infiltrating tumours, argues for a role in tumour biology (40). The presence of mast cells in many tumours has been associated with poor prognosis (41), and it has been suggested that they may contribute to an immunosuppressive tumour microenvironment and thereby impede protective anti-tumour immunity. In addition, mast cells may promote tumour growth by inducing angiogenesis and tissue remodelling through the induction of changes in composition of the extracellular matrix (42). In contrast, in colorectal cancers, mesothelioma, breast cancer, large B cell lymphoma, and in non-small cell lung cancer, high mast cell density has been associated with favourable prognoses (43, 44). The observation of degranulating mast cells near dying tumour cells has suggested a cytotoxic effect and their presence in invasive breast carcinomas correlate with better prognosis (45). In prostate cancer, peri-tumoural mast cells were shown to promote, while intra-tumoural mast cells may restrict angiogenesis and tumour growth (46). This apparent dichotomy in mast cell functions in cancer may be explained by: (i) tumour type, (ii) tumour stage, (iii) mast cell phenotypic plasticity and (iv) location of mast cells in relation to tumour cells.

A wealth of evidence from human cancers and mouse models of cancer indicates that mast cells via the action of histamine on H1, H2 and H4 receptors contribute to tumour invasion and angiogenesis (44). Mast cells may also suppress the development of protective anti-tumour immune responses by promoting regulatory T cell (Treg)-mediated suppression in the tumour microenvironment (47).

Mast cells are attracted to the tumour microenvironment by stem cell factor (SCF) secreted by tumour cells, and secrete pro-angiogenic factors as well as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which promote tumour vascularization and invasiveness. SCF is the ligand for CD117 (c-kit receptor), highly expressed by mast cells. SCF is essential in mast cell recruitment, tumour-associated inflammation, remodelling and immunosuppression (48). SCF-stimulated mast cells produce matrix metalloprotease-9 (MMP-9) that facilitates recruitment of mast cells and other cells to the tumour. MMP-9 also augments tumour-derived SCF production in an amplification feedback loop. Using mast cell-deficient (C57BL/6-KitW-sh/W-sh) mice, it was shown that mast cells (and mast cell-derived MMP-9) are necessary and sufficient to promote growth of subcutaneously engrafted prostate adenocarcinoma cells (49). Furthermore, mast cell tumour-promoting potential is augmented through co-stimulation with tumour-derived SCF and Toll-like Receptor4 (TLR4) ligand, inhibiting mast cell degranulation, but triggering their production and secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and interleukin-10 (IL-10). In contrast, mast cell stimulation by TLR4 ligand alone induces IL-12, important regulator of T and NK cell responses (50).

Fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) and VEGF derived from mast cells trigger intense angiogenic responses in vivo (46). Infiltration of mast cells and activation of MMP-9 parallel the angiogenic switch in pre-malignant lesions and, accordingly, accumulation of mast cells is usually found in the proximity of CD31+ cells and microvessels (51). Mast cells are a major source of interleukin-17 (IL-17) which enhances microvessel formation, being negatively prognostic in gastric cancer (52). Mast cells may also contribute to an immunosuppressive tumour microenvironment as they mobilize the infiltration of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) into tumours and induce the production of IL-17 by MDSCs (47), which indirectly attracts Tregs, enhancing their suppressor function and IL-9 production; in turn, IL-9 strengthens the survival and pro-tumour effect of intratumoural mast cells.

There is some evidence, however, that these pro-tumoural activities of mast cells may be subverted by targeting these cells to promote tumour destruction. In a mouse allograft model, triggering of degranulation of mast cells by IgE antibody cross-linking of cell surface FcεRI resulted in Treg cell impairment and acute CD4+ and CD8+ T cell-mediated tissue destruction (53). In addition, human mast cells have been demonstrated to directly induce lymphoma tumour cell death in vitro when incubated with an anti-CD20 IgE antibody (54). These insights suggest the potential to re-activate these cells against cancer through immunotherapies.

Eosinophils

Blood and tissue eosinophilia are prominent features of allergy and also found to be associated with various cancers. Tumour-associated eosinophilia (TATE) has been reported to correlate with good or with bad prognosis. Epidemiological and clinical studies suggest evidence of intra-tumoural eosinophil degranulation and tumouricidal activity (55) (Figure 1B). Human eosinophils have been reported to induce colon cancer cell death in vitro, implying mechanisms involving innate receptors (TCRγδ/CD3 complex, TLR2) and mediators such as alpha defensins, TNFα, granzyme A and IL-18 (56–58). Tumouricidal functions of eosinophils were target antigen- specific and differed among individuals. Additionally, tumour antigen-specific IgE has been shown to trigger eosinophils-mediated tumour cell death by cytotoxic mechanisms (59). Importantly, eosinophils from allergic donors proved more cytotoxic (56), which suggests that the allergic state favours anti-tumour processes.

Macrophages

Tumour associated macrophages (TAMs) differentiate from monocyte precursors circulating in blood (Figure 1B) and are recruited to tumour sites by several pro-inflammatory molecules such as chemokines (C-C motif chemokine ligand) CCL2, CCL3, CCL4, CCL5, and also VEGF, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and colony stimulating factors (GM-CSF and M-CSF) (60). Even if their phenotype is under the control of specific tumour-derived chemokines and cytokines that polarize macrophages to a pro-immune “M1” or immunosuppressive/pro-angiogenic “M2” phenotype, their transcriptional profiles are distinct from regular M1 or M2 macrophages (61). TAMs are characterized by high expression of CCL2, CCL5, and IL-10 and by MGL1, Dectin-1, CD81, VEGF-A, CD163, CD68, CD206, Arginase 1 (Arg-1), nitric oxide synthase 2 (NOS2), MHC-II, and scavenger receptor A (62). TAMs may differ considerably in terms of function and M1/M2 phenotype, depending on the type of tumour, stage of progression and location within the tumour tissue (60, 63); The M1/M2 TAM heterogeneity could explain the poor prognosis in glioma and breast cancers and better prognosis in stomach and colon, prostate and non-small cell lung cancers (60). TAM heterogeneity depends on the localization in the tumour microenvironment: In normoxic areas, TAMs show a CD206lowMHCIIhi M1-like phenotype; in hypoxic areas TAMs show a CD206hiMHCIIlow M2-like phenotype (61, 63). The expression of Arg-1 as well as VEGF-A, Solute Carrier Family 2 members 1 and 3 (SCL2A1 and SCL2A3) and NOS2 are specifically modulated in hypoxic area in CD206hiMHCIIlow TAMs (63). Innovative drugs allow the positive effects of elevating M1/kill and other anti-cancer innate responses but they also increase an undesired, “overzealous M1/kill–Th1 cytotoxic response” contributing to chronic inflammation (64).

New strategies aim to re-educate TAMs to exert anti-tumour functions. In fact, even in a Th2-M2 tumour micro-environment macrophages stimulated by IL-4 and IL-13 were able to inhibit proliferation of B16-F1 melanoma cells (65). Moreover, macrophages may via IgE and IgG binding to diverse receptors on them acquire anti-tumour killing potency. TAMs express these receptors as well, enabling therapeutic monoclonal antibodies to engage in antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity/phagocytosis (ADCC/ADCP) (66). Recent discoveries show IgG4-positive cells in several tumour environments, possibly being attracted by CCL1-CCR8 interactions. The only macrophage subtype producing CCL1 is M2b which support vascularization and promote Th2-biased tumour microenvironments (67). More research on IgG/IgE effector functions by TAMs is necessary to define new therapeutic concepts.

Dendritic cells

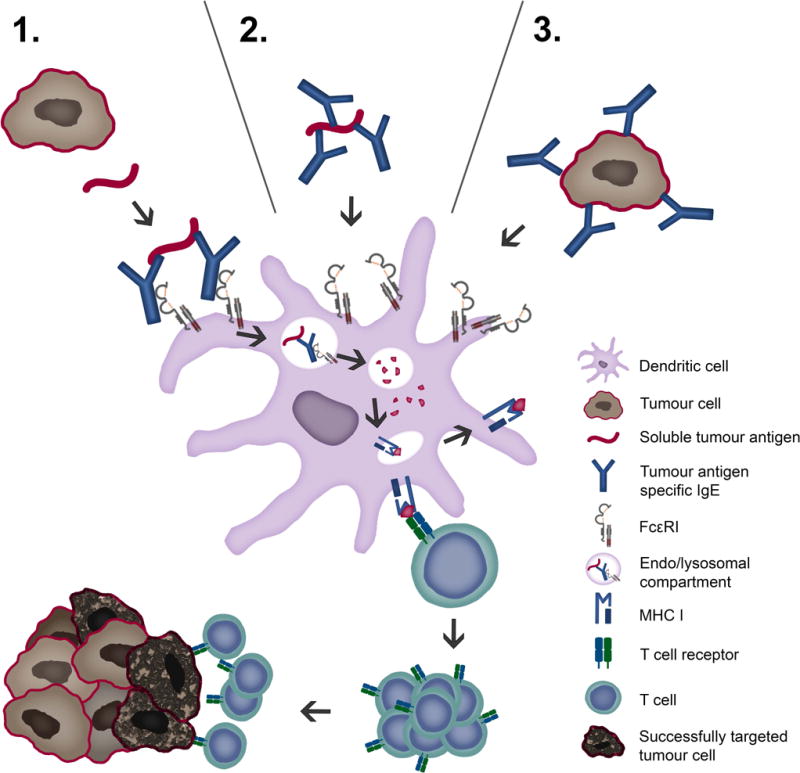

Antigen cross-presentation by DCs is key feature of anti-tumour immunity as it results in the generation of cytotoxic CD8+ T lymphocytes (CTLs) against tumour antigens. Recently, an IgE-mediated cross-presentation pathway has been discovered (68, 69) (Figure 2), resulting in priming of CTLs to soluble antigen at unusually low dose, and independent MyD88 signals or IL-12 production by DCs. Passive immunization experiments and DC-based vaccination strategies confirmed that IgE-mediated cross-presentation significantly improves anti-tumour immunity and even induces memory responses in vivo. However, IL-4, a signature Th2 cytokine, efficiently blunted IgE-mediated cross-presentation indicative for a feedback mechanism that prevents over-shooting CTL responses during allergy (70). Deciphering details of IgE/FcεRI-mediated cross-presentation will further provide new insights into the role of Th2 immune responses in tumour defence and improve DC-based vaccination strategies.

Figure 2. Tumour antigen uptake and presentation by dendritic cells recruits cytotoxic CD8+ T lymphocytes.

Tumour cells display tumour antigens at a high density, facilitating crosslinking of IgE fixed to FcεRI receptors on antigen presenting cells, such as DCs. Tumour antigens may be taken up via three possible routes: 1. soluble tumour antigen binding to receptor-bound IgE; 2. By IgE-opsonized soluble antigen binding to IgE receptors and 3. IgE-opsonized tumour cells binding to IgE receptors. Endocytosis of IgE-antigen complexes leads to digestion in lysosomes and loading of antigenic peptides on MHC I molecules. Cross-presentation via proteasome, loading to MHC I and recognition by CTLs is depicted.

T lymphocytes

CTLs and Th1 cells play the central role in elimination of tumour cells by the immune system (Figure 2). Th1 cells produce interferon-gamma (IFNγ) which mediates anti-tumour activity by several mechanisms, including activation of macrophages, enhancement of antigen processing and presentation, and inhibition of angiogenesis (71). The role of Th2 cells in cancer is more controversial. In some cancers, including breast (72), gastric (73) and pancreatic cancer (74, 75), Th2 cells and associated cytokines (IL-4, IL-13, Thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP)) contribute to tumour progression. In addition, IL-4 plays a crucial role in the survival of colon cancer stem cells (76). Therefore, IL-4- and IL-13 receptors are promising anticancer targets (77). On the other hand, Th2 cells and -cytokines can also play protective roles against cancer. In Hodgkin lymphoma, high numbers of Th2 cells are associated with better survival (78). TSLP has been shown to block early breast carcinogenesis through the induction of Th2 cells (79). TSLP can inhibit colon cancer by inducing apoptosis of cancer cells (80). TSLP and Th2 cells also mediate resistance to carcinogenesis in mice with epidermal barrier defect (81, 82).

Further, DCs pulsed with anti-prostate-specific antigen (PSA) IgE or with anti-HER2/neu IgE antibody, complexed with antigen, induced enhanced CD4 and CD8 T cell activation in vitro compared to antigen-complexed IgG1 (83, 84). Similar observations were made upon OVA-specific IgE/FcεRI-mediated cross-priming in DC and T cell co-cultures, where CD8 T cell proliferation and granzyme B secretion were increased (69). Collectively, these findings support potential roles for Th2 responses in IgE immune surveillance against cancer.

Translational strategies to target cancer

Tumour vaccines and adjuvants

Different approaches to induce IgE-mediated adaptive immunity against cancer have been designed.

A cellular vaccine based on tumour cells infected with Modified Vaccinia virus Ankara (MVA) and loaded with IgE conferred protection in mice upon tumour challenge, slower tumour growth and increased survival (85). This anti-tumour adjuvant effect may depend on the interaction of IgE with FcεRI as it was lost in FcεRIα−/− mice, but not in CD23−/− mice. In parallel, using a humanized hFcεRIα mouse model expressing the human FcεRIα chain, human IgE could exert anti-tumour adjuvant effects (86). When a human truncated mIgE (tmIgE) which retained binding to FcεRI and triggering immune cell activation was inserted into a rMVA, the resulting rMVA-tmIgE showed a protective effect in the above humanized FcεRIα mouse model (86).

Other anti-cancer vaccine approaches are based on specific tumour antigens and tumour antigenic mimotopes which have shown promise in restricting tumour growth (87). When using evolutionarily conserved cancer antigens, such as HER2/neu or EGFR, a vaccine may be used across different species (88). Furthermore, the formulation with adjuvants like aluminium hydroxide, orally sucralfate or proton pump inhibitors, may help to direct induction of protective IgE antibody and merit careful study (89).

Recombinant IgE anti-cancer antibodies

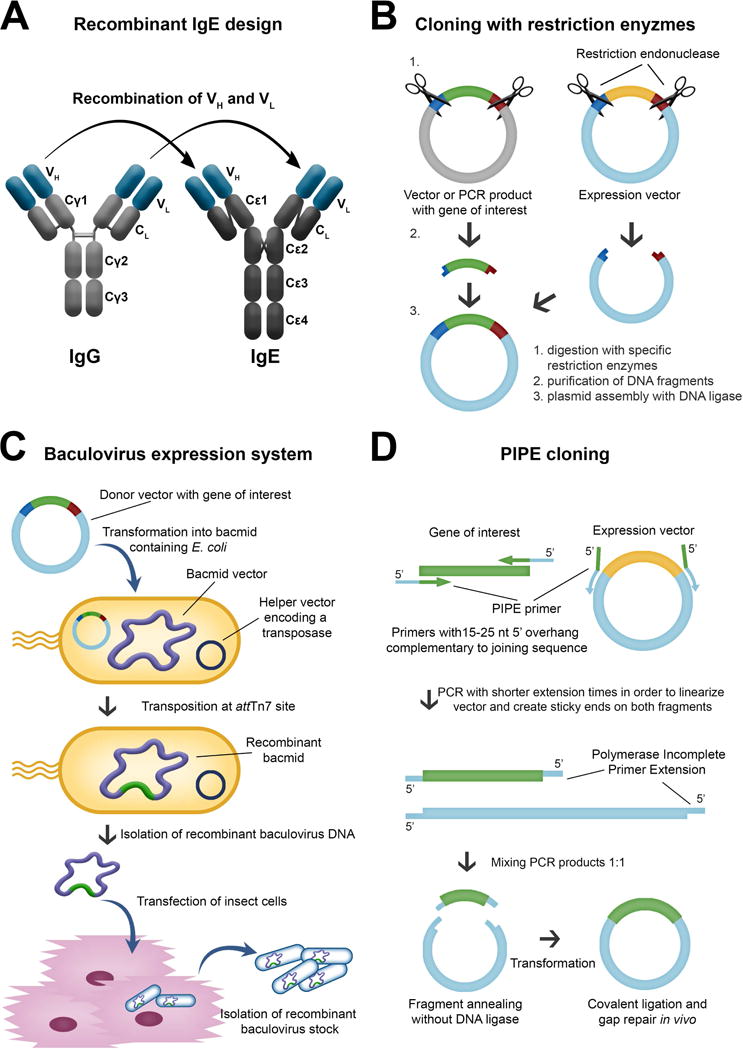

Engineering antibodies with Fc regions of the IgE class specific for cancer antigens is designed to: (i) harness the high affinity of this antibody isotype for its cognate Fcε receptors on tissue-resident and potentially tumour-resident immune effector cells and (ii) utilise the properties of IgE to exert immune surveillance in Th2 conditions such as in tumour microenvironments. Recombinant antibody technologies and approaches to recombinant IgE (rIgE) production have advanced significantly with a number of antibodies already engineered and tested in vitro and in vivo (see Table 2). Recombinant IgE can be generated by different cloning strategies (Figure 3). While classical restriction enzyme-based cloning requires the presence of specific restriction sites flanking the gene of interest, expression of IgE by insect cells requires a recombinant baculovirus stock containing the antibody expression cassette. Novel protocols enable site-specific transposition of the coding sequence using bacmid-containing E.coli as intermediate hosts. Polymerase Incomplete Primer Extension (PIPE) cloning, independent of restriction- or other recombination sites, facilitates rapid cloning with the option of site-specific mutagenesis at the same time. Human/mouse chimaeric IgEs were also generated by hybridoma technology from a knock-in mouse strain (90), and more efficient cloning strategies using mammalian expression vectors are available (91). In future fully human IgE antibodies could be generated from synthetic human antibody repertoire libraries (92), or cloned directly from the B cells of patients (93).

Table 2.

IgE antibodies targeting cancer antigens.

| IgE species | IgE specificity | Nomenclature | Technology used for production | Expression system | In vitro results | Route of IgE in vivo administration | Targeted cancer cells (route of cell inoculation) | Mouse model | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passive immunotherapy studies: | |||||||||

| Mouse | gp36 of MMTV | Clone A8 and H11 | Murine hybridoma | Fusion of spleen cells with P3X20 myeloma cells | NR | i.p. | H2712 mouse mammary carcinoma (s.c. and i.p.) | C3H/HeJ | (Nagy et al., 1991) |

| Rat/human chimeric | Mouse Ly-2 | YTS169.4 | Genetic engineering | Murine hybridoma YTS169.4L | ADCC mediated by murine T cells expressing chimeric FcεRI | s.c. | E3 mouse thymoma (s.c.) | C57BL/6 | (Kershaw et al., 1996) |

| Mouse and mouse/human chimeric | Colorectal cancer antigen | mIgE 30.6 and chIgE 30.6 | Genetic engineering | Murine myeloma (Sp2/0) | Antigen binding affinity | i.v. | Human COLO 205 (s.c.) | SCID | (Kershaw et al., 1998) |

| Rat/human chimeric | Mouse Ly-2 | YTS169.4 | Genetic engineering | Murine hybridoma YTS169.4L | ADCC mediated by human T cells expressing chimeric FcRεI | i.p. | E3 mouse thymoma (i.p.) | NOD-SCID | (Teng et al., 2006) |

| Mouse/human chimeric | FBP | MOv18IgE | Genetic engineering | Murine myeloma (Sp2/0-Ag14) | Degranulation and ADCC cytotoxicity mediated by platelets | i.v. | IGROV1 human ovarian carcinoma cells (s.c.) | C.B-17 scid/scid | (Gould et al., 1999) |

| ADCC and ADCP mediated by human monocytes, ADCC mediated by human eosinophils | i.p. | HUA patient-derived ovarian carcinoma (i.p.) | nu/nu | (Karagiannis et al., 2003; 2007; 2008) | |||||

| Humanized | HER2/neu | Trastuzumab IgE | Genetic engineering | HEK293 | Antigen binding affinity, degranulation, ADCC, interaction with human monocytes, and direct cytotoxicity in human breast cancer cells | NR | NR | NR | (Karagiannis et al, 2009) |

| Human | HER2/neu | C6MH3-B1 IgE | Genetic engineering | Murine myeloma (P3X63Ag8.653) | Degranulation and IgE-facilitated antigen stimulation | i.p. | D2F2/E2 mouse mammary carcinoma cells expressing human HER2/neu (i.p.)2 | Human FcεRIα Tg BALB/c | (Daniels et al., 2012) |

| Mouse/human chimeric | EGFR | 425 IgE and 225IgE | Genetic engineering | HEK293 | Direct cytotoxity induced by 425 IgE, ADCC mediated by 225 IgE and human monocytes | NR | NR | NR | (Spillner et al., 2012) |

| Mouse/human chimeric | MUC1 | 3C6.hIgE | Genetic engineering | CHO-K1 | NR | s.c. | 4T1 tumour cells expressing human MUC1 (s.c.) | Human FcεRIα Tg BALB/c | (Teo et al., 2012) |

| Mouse/human chimeric | CD20 | 1F5.hIgE | Genetic engineering | CHO-K1 | ADCC using human mast cells and eosinophils as effector cells | NR | NR | NR | (Teo et al., 2012) |

| Vaccination studies: | |||||||||

| Mouse | DNP | mAb SP6 | Murine hybridoma (purchased from Sigma Chemical Co.) | Murine hybridoma | NT | i.p. | MC38 mouse colon carcinoma cells expressing human CEA (s.c.) 1 | C57BL/6 | (Reali et al., 2001) |

| Mouse | DNP | SPE7 | Murine hybridoma (purchased from Sigma Aldrich) | Murine hybridoma | Degranulation of haptenized cells | s.c. | TS/A-LACK mouse mammary carcinoma cells coated with DNP (s.c.) | BALB/c | (Nigro et al., 2009) |

| Mouse/human chimeric | NIP | Anti-NIP IgE | Genetic engineering | J558L murine myeoma | Degranulation of haptenized cells | s.c. | TS/A-LACK mouse mammary carcinoma cells coated with NIP (s.c.) | Human FcεRIα Tg BALB/c | (Nigro et al., 2009) |

| Human (truncated) | N/A | tmIgE | Genetic engineering | Chicken embryo fibroblasts | Degranulation | s.c. | TS/A-LACK mouse mammary carcinoma cells coated with truncated IgE (s.c.) | Human FcεRIα Tg BALB/c | (Nigro et al., 2012) |

| Mouse/human chimeric | PSA | Anti-PSA IgE | Genetic engineering | Murine myeloma (Sp2/0-Ag14) | Degranulation and IgE-facilitated antigen stimulation | s.c. | CT26 tumour cells expressing human PSA (s.c.) | Human FcεRIα Tg BALB/c | (Daniels-Wells et al., 2013) |

Tumour targeting occurred via a biotinylated anti-CEA IgG followed by streptavidin and then a biotinylated IgE

A pilot toxicity study also conducted in non-human primates (cymolgus monkeys)

DNP: dinitrophenol (hapten), EGFR: epidermal growth factor receptor, FBP: folate binding protein, HEK: human embryonic kidney, HER2/neu: human EGFR2/neuroblastoma, i.p.: intraperitoneal, i.v.: intravenous, MMTV: mouse mammary tumour virus, MUC1: mucin-1, cell surface associated, NIP: nitrophenylacetyl (hapten), NR: not reported, PSA: prostate-specific antigen, s.c.: subcutaneous, Tg: transgenic

Figure 3. Examples of expression systems used for recombinant expression of anti-tumour IgE.

A. Recombinant IgE by cloning the variable domains of IgG of desired specificity to an IgE constant domain. B. Classical restriction enzyme-based cloning requires the presence of specific restriction sites flanking the gene of interest. C. Expression of IgE by insect cells requires a recombinant baculovirus stock containing the antibody expression cassette. D. Polymerase Incomplete Primer Extension (PIPE) cloning facilitates a rapid cloning of DNA sequences with the option of performing site-specific mutagenesis at the same time.

Also the heavily-glycosylated structure of the IgE antibody class has to be considered. IgE has 7 glycosylation sites, 6 of which are occupied mainly by complex N-glycans including terminal galactose, sialic acid and fucose structures (94). Oligomannosidic structures are only identified at position Asn394 (94), and some evidence suggests that they may be involved in binding to IgE Fc receptors and in some biological activities of IgE (95). On the other hand, complex N-glycosylation of IgE is not thought to have a direct impact on its ability to bind to FcεRI or CD23. The contribution of glycosylation on IgE binding to galectin-3 and -9 (96) remains unclear. There is increasing evidence that the glycosylation of IgEs in healthy and different disease states may vary, prompting the need for further research on the importance of glycans on IgE functions against cancer.

In vitro effector functions of IgE antibodies in the cancer context

Eosinophil, monocyte and macrophage-mediated ADCC/ADCP, antigen-presentation by DCs and degranulation of mast cells and basophils, have been identified as potent mechanisms of IgE-mediated anti-cancer functions in vitro (69, 97, 98) (Figure 1B).

The ADCC/ADCP functions against cancer of the anti-folate receptor alpha (FRα) IgE, MOv18, have been previously-described (59). Recently, the therapeutic anti-HER2/neu and anti-EGFR IgG1 antibodies, trastuzumab (Herceptin®) and cetuximab (Erbitux®), respectively, have been cloned and engineered recombinantly as humanised and chimaeric IgE antibodies (99, 100). Using U937 monocytic effector cells (101), trastuzumab IgG1 mediated killing of HER2-overexpressing CT26 murine as well as of SKBR3 human mammary carcinoma cells mainly by ADCP, whereas trastuzumab IgE mediated killing via ADCC (99). Similarly, cetuximab IgG1 and IgE mediated comparable levels of phagocytosis of EGFR-overexpressing A431 human tumour cells by purified human monocytes, but cetuximab IgE triggered significantly higher levels of ADCC than IgG1 (100). Eosinophil ADCC killing has also been demonstrated in vitro using an anti-human CD20 IgE antibody against OCl-Ly8 lymphoma cells (54). Incubation with this anti-CD20 IgE stimulated cord blood-derived mast cells to release IL-8 and kill CD20+ tumour cells. Similarly, trastuzumab IgE, cetuximab IgE, anti-PSA IgE, and MOv18 IgE activated RBL-SX-38 rat basophilic leukemia cells when cross-linked with anti-IgE antibody engaged with multimeric antigen, or when incubated with target cells overexpressing specific tumour-associated antigen (84, 99, 100, 102). In contrast, monomeric soluble tumor antigen did not trigger degranulation (84, 100, 102). Accordingly, incubation of MOv18 IgE-sensitised RBL SX-38 cells with patient sera containing elevated levels of soluble FRα, did not lead to mast cell degranulation. Furthermore, MOv18 IgE did not trigger the basophil activation in the presence of soluble FRα, which is highly elevated in the sera of subsets of ovarian carcinoma and mesothelioma patients (102). This suggests that in tumours, mast cells may release potent inflammatory mediators in the presence of tumour -specific IgE and overexpressed tumour antigen, while IgE in the absence of multimeric antigen is not expected to trigger anaphylactic responses. Notably, antigenic epitopes also need to be displayed in a rigid spacing to lead to productive triggering (103). Given that the potent anti-cancer functions of IgE antibodies in vitro, it is important to consider these results in the patient context (104). The impact of soluble tumour antigen in the circulation has been considered from a safety perspective (97, 102). However, the possible inhibitory activity of soluble tumour antigen sequestering IgE and preventing tumour cell engagement with effector cells needs to be elucidated.

Furthermore, the ability of patient immune effector cells to eradicate malignant cells must be evaluated to consider: a) the impact of treatments as chemotherapy or steroid intake on effector cell functions, b) the effect of the tumour microenvironment on IgE receptor expression and on killing properties of these effector cells, and c) whether IgE immunotherapy may itself re-educate effector cells to enhance their anti-tumour functions (105).

In vivo models in AllergoOncology

Various animal models have been successfully employed to study the in vivo efficacy of IgE antibodies against cancer (106), with different limitations.

Direct application of human IgE in tumour bearing mice is not applicable as human IgE does not bind rodent Fcε receptors (Table 3). Next, humans express FcεRI on a broad range of cells including monocytes, mast cells, basophils, eosinophils, platelets, Langerhans- and DCs (Table 1), whereas, murine FcεRI expression has only been confirmed on mast cells and basophils (Table 4). Furthermore, also CD23 can be found on numerous human cells, while mice express CD23 on only B cells and certain T cells (106).

Table 3.

Cross-reactivity of IgE and Fcε receptors of different species, with the equilibrium association constant (KA) or equilibrium dissociation constant (KD), where available, described exactly as in the original references.

| Species | Human FcεRI | NHP1) FcεRI | Mouse FcεRI | Rat FcεRI | Dog FcεRI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human IgE | KA⌘=0.5–2.7

×109

M−1 Ishizaka T, Soto CS, Ishizaka K. Mechanisms of passive sensitization. III. J Immunol. 1973; 111(2):500–11. Pruzansky JJ, Patterson R. Immunology. 1986; 58(2):257–62. |

KD⌘=1.876×10−8M Saul L et al. MAbs. 2014; 6(2):509–22. |

No binding Fung-Leung WP et al. J Exp Med. 1996;183:49–56. |

No binding Fung-Leung WP et al. J Exp Med. 1996;183:49–56. |

No binding Lowenthal M, Patterson R, Harris KE. Ann Allergy. 1993; 71(5):481–4. |

| NHP IgE | KD=3×10−10

M Meng YG, Singh N, Wong WL. Mol Immunol. 1996; 33(7–8):635–42. |

N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | No binding Lowenthal M, Patterson R, Harris KE. Ann Allergy. 1993; 71(5):481–4. |

| Mouse IgE | KA⌘=4.4 ×108 M−1 | N.D. | KA⌘=1.75–3.57§

×109

M−1 Sterk AR, Ishizaka T. J Immunol. 1982; 128(2):838–43. |

KA⌘=2.49 –

5.05¶

×109

M−1 Sterk AR, Ishizaka T. J Immunol. 1982; 128(2):838–43. |

N.D. |

| Rat IgE | KD⌘=1.58×10−8

M Mallamaci MA et al. J Biol Chem. 1993; 268(29):22076–83. |

N.D. | KA⌘=1.46 –

2.68§

×109

M−1 Sterk AR, Ishizaka T. J Immunol. 1982; 128(2):838–43. |

KA⌘=7.84 –

8.05¶

×109

M−1 Sterk AR, Ishizaka T. J Immunol. 1982; 128(2):838–43. |

N.D. |

| Dog IgE | KD=9.2

×10−9 M Fung-Leung WP et al. J Exp Med. 1996;183:49–56. Ye H et al. Mol Immunol. 2014; 57(2):151–9. |

Confirmed

binding Fung-Leung WP et al. J Exp Med. 1996;183:49–56. |

N.D. | N.D. | KD=2.1

×10−8 M Ye H et al. Mol Immunol. 2014; 57(2):151–9. |

N.D. not determined.

affinity determination based on cells, not receptor subunits; therefore, also CD23 binding might contribute to the denoted values

depending on mouse strain used as a source of mast cells

depending on mast cell source (rat or RBL cell line)

Table 4.

Tissue distribution of IgE receptors in humans versus animal models in AllergoOncology.

| Human | |||

| basophils, mast cells, eosinophils, monocytes,

dendritic cells, Langerhans-cells Reviewed in: Daniels TR et al. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2012;61(9):1535–1546. |

monocytes, eosinophils, B cells, T cells,

dendritic cells, Langerhans cells, platelets Rev. in: Daniels TR et al. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2012;61(9):1535–1546. |

||

| Mouse (wt) | |||

| Basophils, mast

cells Rev. in: Daniels TR et al. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2012;61(9):1535–1546. |

μ+, δ+ B

cells, some CD8+ T cell

subsets Delespesse G et al. Immunol Rev. 1992 Feb;125:77–97. |

||

| Mouse (transgenic) | |||

|

mFcεRIα−/−,

hFcεRIαTg, C57BL/6

background Dombrowicz D et al. Immunity 1998;8(4):517–529. |

hFcεRIα on bone marrow derived

mast cells Dombrowicz D et al. J Immunol. 1996 Aug 15;157(4):1645–51. |

mFcεRIα is replaced with hFcεRIα, which complexes with murine FcRβ and FcRγ subunits | |

|

hFcεRIαTg,

C57BL/6J

background Fung-Leung WP et al. J Exp Med. 1996 Jan 1; 183(1): 49–56. |

hFcεRIα on bone marrow derived

mast cells Fung-Leung WP et al. J Exp Med. 1996 Jan 1; 183(1): 49–56. PMCID: PMC2192401 |

hFcεRIα complexes with murine FcRβ and FcRγ subunits | |

|

Model 1:

mFcεRIα−/−,

hFcεRIαTg Model 2: mFcεRIα−/−, mFcRβ−/−, hFcεRIαTg, BALB/c background Dombrowicz D et al. Immunity, Volume 8, Issue 4, 1 April 1998, Pages 517–529 |

Mast cells, basophils, monocytes, eosinophils,

Langerhans cells Dombrowicz D et al. Immunity, Volume 8, Issue 4, 1 April 1998, Pages 517–529 |

mFcεRIα is replaced with hFcεRIα, which complexes with murine FcRβ and/or FcRγ subunits | |

| Rat | |||

| Basophils, mast cells, macrophages,

eosinophils Daniels TR et al. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2012;61(9):1535–1546. |

B cells, macrophages Capron A et al. Eur J Immunol. 1977 May;7(5):315–22. Mencia-Huerta JM et al. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1991;94(1–4):295–8. |

||

| Dog | |||

| Basophils, tissue mast cells, monocytes,

Langerhans cells, CD1+ dendritic cells Jackson HA et al. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology, Volume 85, Issues 3–4, March 2002, Pages 225–232 |

Eosinophils Galkowska H et al. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology. Vol 53, Issues 3–4, October 1996, Pages 329–334 |

Data not complete, sometimes not evident if expression relates to FcεRI or CD23 | |

Despite these differences, a xenograft model with severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice, and a patient-derived xenograft model of ovarian carcinoma both reconstituted with human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), were successfully used to demonstrate the superior tumour-killing potential of MOv18 IgE over IgG1 via both CD23 and FcεRI (59, 107). More human-relevant models have been established using transgenic mice strains that express human FcεRIα, which complexes with endogenous murine FcRβ and -γ subunits, forming fully functional tetrameric FcεRI on mast cells and possibly trimeric receptors on macrophages, Langerhans cells and eosinophils, with a tissue distribution like in humans (108–110). A human anti HER2/neu (C6MH3-B1 IgE) IgE tested in this model significantly prolonged the survival of immunocompetent mice bearing HER2/neu expressing tumours (83). A constraint of these transgenic models is the lack of CD23 expression, precluding evaluation of IgE-triggered CD23-mediated phagocytosis (111). A surrogate immunocompetent model system of syngeneic carcinoma in rats aims to better recapitulate the human IgE immune system (105), as FcεRI and CD23 expression and cellular distribution in rat cells, including monocytes and macrophages, mirrors that of humans.

Relevant models to address toxicity of human IgE antibodies are non-human primates (NHP) such as cynomolgus (Macaca fascicularis) and rhesus (Macaca mulatta) monkeys, since they have been shown to mediate anaphylaxis induced by human IgE (112). Cynomolgus monkeys have been routinely used to evaluate the safety of IgG therapeutic antibodies currently used in the clinic. A fully human IgE antibody targeting HER2/neu (C6MH3-B1 IgE), administered systemically, was also well tolerated in cynomolgus monkeys (83). However, whilst recent studies confirmed the cross-reactivity of human IgE with cynomolgus monkey peripheral blood leukocytes (PBLs) with comparable binding kinetics, human IgE dissociates faster from cynomolgus monkey PBLs and triggers a different cytokine release profile (113). This is important in toxicity studies using IgE in this species. Further, also differences in the interaction of FcγRs with the various human IgG isotypes have been found (114). Thus, while NHP are meaningful models for toxicity studies of human antibodies, they must be used with caution.

The dog (Canis lupus familiaris) is another potential model, as dogs suffer from spontaneous cancer and atopic diseases, making them a relevant clinical experimental model (115). For instance, the canine counterparts to HER2/neu and canine EGFR expression are highly homologous to the human molecules, and can be targeted by trastuzumab and cetuximab (88). An additional advantage is the remarkable similarity of the human and dog immune systems in terms of immunoglobulin classes, IgE and FcεRI expression and functional homology (116). Thus, canine anti-EGFR IgG has been generated (117) and IgE is currently being generated for comparative studies in canine cancer patients.

The described animal models are informative for pre-clinical testing, but clinical trials in human patients are required to fully-understand the therapeutic potential and risks associated with IgE anti-cancer antibodies.

Allergy in clinical oncology: a cross-disciplinary field

Allergic reactions to anti-cancer drugs are a common clinical problem, seen especially with platinum drugs, taxanes, anthracyclines (118), and monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) (119). In some cases, it is the excipient rather than the drug itself that is responsible for the hypersensitivity reaction. The administration of some of these drugs is routinely preceded by pre-medication with steroids.

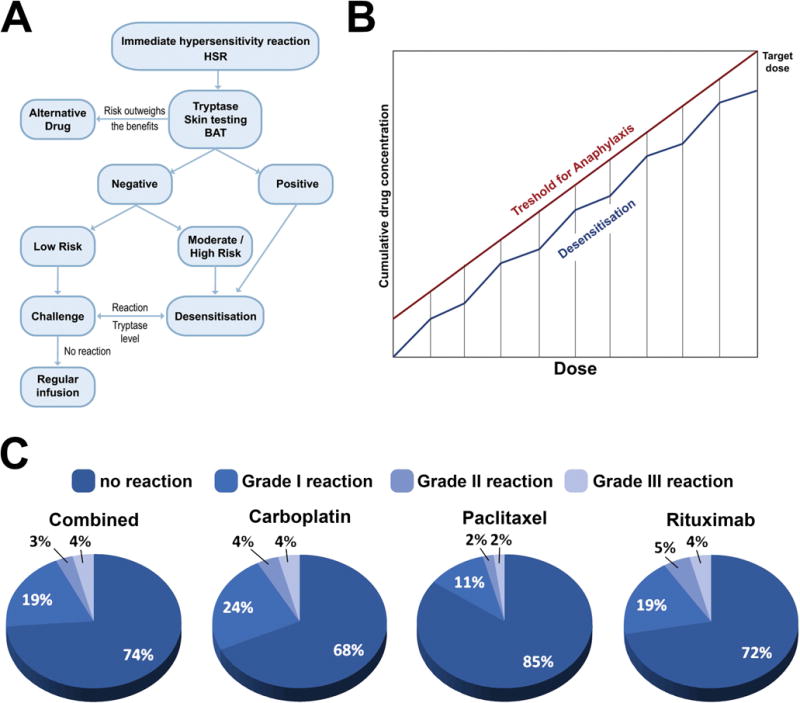

Treatment of allergic anti-cancer drug reactions is, as for other episodes of hypersensitivity, using intravenous fluids, anti-histamines, steroids, and anti-pyretics, depending on the risk evaluation (Figure 4A). Desensitisation algorithms can be used in cases of established drug allergy, in which escalating small doses of the drug are administered in a controlled environment with ready access to critical care facilities (120) (Table 5). Desensitisation has a particular role to play in clinical scenarios where repeated re-challenge with an active drug may be required, as in the management of ovarian cancer, but also in allergy to anti-cancer mAbs (121).

Figure 4. Treating hypersensitivity in clinical oncology.

A. Proposed algorithm for the evaluation of Chemotherapy Drugs Hypersensitivity and indications for Rapid Drug Desensitization (RDD). Legend: BAT - basophil activation test; HSR - immediate hypersensitivity reaction. B. Proposed mechanism for Chemotherapy Rapid Drugs Desensitization (RDD). (adapted from (164)) C. Outcomes of Brigham & Women’s Hospital Desensitization Protocols for Carboplatin, Paclitaxel and Rituximab in 2177 cases for 370 patients (adapted from (164)).

Table 5.

Brigham & Women’s Hospital 3 bags 12 steps Desensitization Protocol for Paclitaxel 300 mg

| Target dose (mg) | 300 | |||||

| Standard volume per bag (ml) | 250 | |||||

| Final rate of infusion (ml/h) | 80 | |||||

| Calculated target concentration (mg/ml) | 1.2 | |||||

| Standard time of infusion (minutes) | 187.5 | |||||

| Volume | Concentration (mg/ml) | Total mg per bag | Amount infused (ml) | |||

| Solution1 | 250 | ml of | 0.012 | mg/ml | 3 | 9.38 |

| Solution2 | 250 | ml of | 0.120 | mg/ml | 30 | 18.75 |

| Solution3 | 250 | ml of | 1.190 | mg/ml | 297.638 | 250 |

| Step | Solution | Rate (ml/h) | Time (min) | Volume infused per step (ml) | Dose administered with this step (mg) | Cumulative dose (mg) |

| 1 | 1 | 2.5 | 15 | 0.63 | 0.0075 | 0.0075 |

| 2 | 1 | 5 | 15 | 1.25 | 0.015 | 0.0225 |

| 3 | 1 | 10 | 15 | 2.5 | 0.03 | 0.0525 |

| 4 | 1 | 20 | 15 | 5 | 0.06 | 0.1125 |

| 5 | 2 | 5 | 15 | 1.25 | 0.15 | 0.2625 |

| 6 | 2 | 10 | 15 | 2.5 | 0.3 | 0.5625 |

| 7 | 2 | 20 | 15 | 5 | 0.6 | 1.1625 |

| 8 | 2 | 40 | 15 | 10 | 1.2 | 2.3625 |

| 9 | 3 | 10 | 15 | 2.5 | 2.9764 | 5.3389 |

| 10 | 3 | 20 | 15 | 5 | 5.9528 | 11.2916 |

| 11 | 3 | 40 | 15 | 10 | 11.9055 | 23.1971 |

| 12 | 3 | 80 | 174.375 | 232.5 | 276.8029 | 300 |

| Total time: 5.66 hrs | ||||||

***PLEASE NOTE***

The total volume and dose dispensed are more than the final dose given to patient because many of the solutions are not completely infused.

Due to the increased utilization of chemotherapies and targeted mAbs hypersensitivity reactions to these medications have increased dramatically worldwide, preventing the use of first-line therapies, with consequent impact in patient’s survival and quality of life (122). These reactions can range from mild cutaneous reactions to life-threatening symptoms including anaphylactic shock with IgE and/or mast cell/basophil involvement, and occur during or within one 1 hour of the drug infusion or hours - days, since these patients have extensive pre-medications, including steroids (123). The symptoms are associated with the release of tryptase and other mediators such as histamine, leukotrienes and prostaglandins, implicated in the cutaneous, respiratory, gastrointestinal and cardiovascular symptoms (124). Other systemic symptoms such as chills and fever are thought to be due to the release of IL-1 and IL-6 among others (125). Atypical symptoms such as pain have been associated with taxanes and some monoclonal antibodies (126). Deaths have been reported when re-exposing patients to chemotherapy drugs to which they have presented immediate hypersensitivity reactions (127). Delayed reactions can present as either mast cell/basophil-mediated symptoms or as delayed cell-mediated type intravenous (i.v.) hypersensitivity (128).

There is increasing evidence that patients with immediate and delayed hypersensitivity to chemotherapy and monoclonal antibodies can be safely re-exposed to these medications through rapid drug desensitization (RDD) (129), in which diluted amounts of drug are reintroduced through a multi-step protocol, achieving the target dose in few hours (Figure 4B). Thereby, inhibitory mast cell mechanisms protect the patients against anaphylaxis (130). Most patients with hypersensitivity reactions are candidates for RDD, except for patients with Steven Johnsons Syndrome (SJS), toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), and acute excematous generalized pustulosis (AGEP). The success of RDD relies on personalized protocols (131). Platins including carboplatin, cisplatin and oxaliplatin, taxanes including paclitaxel and docetaxel and monoclonal antibodies such as rituximab, trastuzumab and cetuximab have been successfully desensitized (132). The largest desensitization study worldwide reported that 370 highly allergic patients received 2177 successful desensitisations to 15 drugs, 3 of which (bevacizumab, tocilizumab, and gemcitabine) were unprecedented and in which 93% of the procedures had no or mild reactions, 7% moderate to severe reactions which did not preclude the completion of the treatment, and there were no deaths (Figure 4C) (133). The study indicates that the overall health costs were not increased over standard treatment. Most importantly, a group of women with ovarian cancer sensitized to carboplatin had a non-statistically significant lifespan advantage over non allergic controls.

Therefore, IgE and non-IgE mediated chemotherapy hypersensitivity reactions can be managed by RDD, enabling sensitized patients to receive the full treatment safely, thus representing an important advance in the patient’s treatment and prognosis.

Conclusions

This position paper summarises current knowledge and developments in the field of AllergoOncology since (1). Novel insights gained highlight the merits of studying the nature of Th2 immune responses in cancer, much of which remains insufficiently understood. Epidemiologic analyses support associations between allergies, allergen-specific and total IgE levels with lower risk of cancer development, to date only shown with regards to specific malignancies. Whether these associations relate to antigen- or allergen-specific responses or whether they represent protective effects of IgE through recognition of specific tumour antigens remains unclear. Understanding these associations and the contributions of IgE and Th2 immunity in protection from cancer growth would also contribute to understanding whether patients with allergic asthma who receive anti-IgE treatment may be at risk of developing cancer. Short-term follow-up findings have not revealed any enhanced risk of cancer development to date (134), however, further longer follow up studies and novel functional insights will be informative.

Emerging studies further support the study of the prototypic Th2 isotype, IgE as a means to combat tumours when directed against cancer antigens through promoting the interaction between effector and cancer cells, and stimulating CTLs via antigen cross-presentation. Collectively, these findings support the unique properties of IgE to activate anticancer immune responses in passive and active immunotherapy of cancer and provide evidence of safety. Whereas cell-fixed tumour antigen can trigger cross-linking of IgE on its Fc receptors expressed on effector cells, monovalent soluble antigen does not. Some in vivo models relevant to IgE biology, have been designed with careful consideration of species-specific IgE receptor expression profile. Mouse models have been used most often, whereas rats, dogs and NHP may offer new alternatives to address specific questions of potency, safety and function. A couple of recombinant anti-cancer IgE antibodies are in the pipeline, and parallel interrogation of the same antibody immunotherapies in clinical oncology will determine the predictive value of in vivo models.

Recent findings shed light into the alternative Th2 antibody isotype IgG4 and its expression and functions in melanoma and other cancers (135). The mechanisms of this humoral immune bias in oncology merit further in-depth study. Finally, it has to be emphasized that allergic reactions to anti-cancer agents, chemotherapy and biologics, represent important challenges in daily clinical oncology practice, which can be dealt with by desensitization protocols analogous to those used in allergen immunotherapy.

In summary, the AllergoOncology field represents an open interdisciplinary science forum where different aspects of the interface between allergy and cancer are systematically addressed and discussed, gaining thereby previously-unappreciated insights for cancer immunotherapy.

Acknowledgments

The AllergoOncology Task Force was financed by the European Academy for Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI). The authors would like to thank EAACI for their financial support in the development of this Task Force report.

The authors acknowledge support by the Austrian Science Fund FWF grants P23398-B11, F4606-B28 (EJJ), KLI284 (EU), P23228-B19, P22441-B13 (DM); Israel cancer Association #20161131 and Israel Science Foundation #472/15) (FLS); by Cancer Research UK (C30122/A11527; C30122/A15774); The Academy of Medical Sciences (DHJ, SNK, JFS); the Medical Research Council (MR/L023091/1); Breast Cancer Now – the UK’s largest breast cancer charity – created by the merger of Breast Cancer Campaign and Breakthrough Breast Cancer (147) (SNK); CR UK/NIHR in England/DoH for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland Experimental Cancer Medicine Centre (C10355/A15587); NIH/NCI grants R01CA181115 (MLP) and R21CA179680 (TRD); MCT was funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Fellowship. The research was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre based at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Footnotes

Statement

All authors have read and approved the position paper. None of the authors has any conflict of interest.

- Epidemiology: Turner MC

- Th2-associated antibodies in cancer: Singer J, Redegeld F, Spillner E, Karagiannis P

- In situ expression of AID and potential insights into antibody isotype expression in cancer: Meshcheryakova A, Mechtcheriakova D, Mungenast F

- IgE receptor expression on immune cells and epithelial cells: Untersmayr E

- Effector cells in allergy and cancer

-

◦Mast cells: Levi-Schaffer F, Mekori Y, Bax HJ, Josephs DH

-

◦Eosinophils: Capron M, Gatault S

-

◦Macrophages: Bianchini R, Jensen-Jarolim E

-

◦Dendritic cells: Fiebiger E

-

◦T lymphocytes: Janda J

-

◦

- Translational strategies to target cancer

-

◦Tumour vaccines and adjuvants: Nigro EA, Vangelista L, Siccardi AG, Jensen-Jarolim E

-

◦Recombinant IgE anti-cancer antibodies: Daniels-Wells TR, Penichet ML, Spillner E, Gould HJ

-

◦In vitro effector functions of IgE antibodies in the cancer context: Josephs DH,, Bax HJ, Karagiannis P, Saul L, Karagiannis SN

-

◦In vivo models in AllergoOncology: Dombrowicz D, Fazekas J, Bax HJ, Daniels-Wells TR, Penichet ML, Jensen_jarolim E, Karagiannis SN

-

◦Allergy in clinical oncology: Castells M, Corrigan C, Spicer J

-

◦

-

▪Manuscript assembly: Jensen-Jarolim E and Karagiannis SN wrote abstract, introduction, conclusion, and contributed to several sections, and Fazekas J designed all figures.

References

- 1.Jensen-Jarolim E, Achatz G, Turner MC, Karagiannis S, Legrand F, Capron M, et al. AllergoOncology: the role of IgE-mediated allergy in cancer. Allergy. 2008;63(10):1255–1266. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01768.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Penichet ML, Jensen-Jarolim E, editors. Cancer and IgE: Introducing the concept of AllergoOncology. Springer; New York, USA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jensen-Jarolim E, Pawelec G. The nascent field of AllergoOncology. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2012;61(9):1355–1357. doi: 10.1007/s00262-012-1315-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turner MC. Epidemiology: allergy history, IgE, and cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2012;61(9):1493–1510. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1180-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Hemelrijck M, Garmo H, Binda E, Hayday A, Karagiannis SN, Hammar N, et al. Immunoglobulin E and cancer: a meta-analysis and a large Swedish cohort study. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21(10):1657–1667. doi: 10.1007/s10552-010-9594-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacobs EJ, Gapstur SM, Newton CC, Turner MC, Campbell PT. Hay Fever and asthma as markers of atopic immune response and risk of colorectal cancer in three large cohort studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22(4):661–669. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Linabery AM, Prizment AE, Anderson KE, Cerhan JR, Poynter JN, Ross JA. Allergic diseases and risk of hematopoietic malignancies in a cohort of postmenopausal women: a report from the Iowa Women’s Health Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23(9):1903–1912. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Platz EA, Drake CG, Wilson KM, Sutcliffe S, Kenfield SA, Mucci LA, et al. Asthma and risk of lethal prostate cancer in the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study. Int J Cancer. 2015;137(4):949–958. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cahoon EK, Inskip PD, Gridley G, Brenner AV. Immune-related conditions and subsequent risk of brain cancer in a cohort of 4.5 million male US veterans. Br J Cancer. 2014;110(7):1825–1833. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwartzbaum J, Ding B, Johannesen TB, Osnes LT, Karavodin L, Ahlbom A, et al. Association between prediagnostic IgE levels and risk of glioma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104(16):1251–1259. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schlehofer B, Siegmund B, Linseisen J, Schuz J, Rohrmann S, Becker S, et al. Primary brain tumours and specific serum immunoglobulin E: a case-control study nested in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition cohort. Allergy. 2011;66(11):1434–1441. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wulaningsih W, Holmberg L, Garmo H, Karagiannis S, Ahlstedt S, Malmstrom H, et al. Investigating the association between allergen-specific immunoglobulin E, cancer risk and survival. OncoImmunology. 2016;5(6):e1154250. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1154250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nieters A, Luczynska A, Becker S, Becker N, Vermeulen R, Overvad K, et al. Prediagnostic immunoglobulin E levels and risk of chronic lymphocytic leukemia, other lymphomas and multiple myeloma-results of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Carcinogenesis. 2014;35(12):2716–2722. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgu188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olson SH, Hsu M, Wiemels JL, Bracci PM, Zhou M, Patoka J, et al. Serum immunoglobulin e and risk of pancreatic cancer in the prostate, lung, colorectal, and ovarian cancer screening trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23(7):1414–1420. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skaaby T, Nystrup Husemoen LL, Roswall N, Thuesen BH, Linneberg A. Atopy and development of cancer: a population-based prospective study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2(6):779–785. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prizment AE, Anderson KE, Visvanathan K, Folsom AR. Inverse association of eosinophil count with colorectal cancer incidence: atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(9):1861–1864. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Purdue MP, Lan Q, Kemp TJ, Hildesheim A, Weinstein SJ, Hofmann JN, et al. Elevated serum sCD23 and sCD30 up to two decades prior to diagnosis associated with increased risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Leukemia. 2015;29(6):1429–1431. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Backes DM, Siddiq A, Cox DG, Calboli FC, Gaziano JM, Ma J, et al. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms of allergy-related genes and risk of adult glioma. J Neurooncol. 2013;113(2):229–238. doi: 10.1007/s11060-013-1122-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Josephs DH, Spicer JF, Corrigan CJ, Gould HJ, Karagiannis SN. Epidemiological associations of allergy, IgE and cancer. Clin Exp Allergy. 2013;43(10):1110–1123. doi: 10.1111/cea.12178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karagiannis P, Gilbert AE, Josephs DH, Ali N, Dodev T, Saul L, et al. IgG4 subclass antibodies impair antitumor immunity in melanoma. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(4):1457–1474. doi: 10.1172/JCI65579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Groot Kormelink T, Powe DG, Kuijpers SA, Abudukelimu A, Fens MH, Pieters EH, et al. Immunoglobulin free light chains are biomarkers of poor prognosis in basal-like breast cancer and are potential targets in tumor-associated inflammation. Oncotarget. 2014;5(10):3159–3167. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andreu P, Johansson M, Affara NI, Pucci F, Tan T, Junankar S, et al. FcRgamma activation regulates inflammation-associated squamous carcinogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2010;17(2):121–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zennaro D, Capalbo C, Scala E, Liso M, Spillner E, Braren I, et al. IgE, IgG4 and IgG response to tissue-specific and environmental antigens in patients affected by cancer. European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI); Istanbul, Turkey: 2011. p. Abstract 209. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bluth MH. IgE and chemotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2012;61(9):1585–1590. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1170-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fu SL, Pierre J, Smith-Norowitz TA, Hagler M, Bowne W, Pincus MR, et al. Immunoglobulin E antibodies from pancreatic cancer patients mediate antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity against pancreatic cancer cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008;153(3):401–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03726.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matta GM, Battaglio S, Dibello C, Napoli P, Baldi C, Ciccone G, et al. Polyclonal immunoglobulin E levels are correlated with hemoglobin values and overall survival in patients with multiple myeloma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(18 Pt 1):5348–5354. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mechtcheriakova D, Svoboda M, Meshcheryakova A, Jensen-Jarolim E. Activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) linking immunity, chronic inflammation, and cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2012;61(9):1591–1598. doi: 10.1007/s00262-012-1255-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gould HJ, Takhar P, Harries HE, Durham SR, Corrigan CJ. Germinal-centre reactions in allergic inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2006;27(10):446–452. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strid J, Sobolev O, Zafirova B, Polic B, Hayday A. The intraepithelial T cell response to NKG2D-ligands links lymphoid stress surveillance to atopy. Science. 2011;334(6060):1293–1297. doi: 10.1126/science.1211250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Finkin S, Yuan D, Stein I, Taniguchi K, Weber A, Unger K, et al. Ectopic lymphoid structures function as microniches for tumor progenitor cells in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Immunol. 2015;16(12):1235–1244. doi: 10.1038/ni.3290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meshcheryakova A, Tamandl D, Bajna E, Stift J, Mittlboeck M, Svoboda M, et al. B cells and ectopic follicular structures: novel players in anti-tumor programming with prognostic power for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e99008. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alphonse MP, Saffar AS, Shan L, HayGlass KT, Simons FE, Gounni AS. Regulation of the high affinity IgE receptor (Fc epsilonRI) in human neutrophils: role of seasonal allergen exposure and Th-2 cytokines. PLoS One. 2008;3(4):e1921. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dehlink E, Baker AH, Yen E, Nurko S, Fiebiger E. Relationships between levels of serum IgE, cell-bound IgE, and IgE-receptors on peripheral blood cells in a pediatric population. PLoS One. 2010;5(8):e12204. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakajima K, Kho DH, Yanagawa T, Harazono Y, Hogan V, Chen W, et al. Galectin-3 Cleavage Alters Bone Remodeling: Different Outcomes in Breast and Prostate Cancer Skeletal Metastasis. Cancer Res. 2016;76(6):1391–1402. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tadokoro T, Morishita A, Fujihara S, Iwama H, Niki T, Fujita K, et al. Galectin-9: An anticancer molecule for gallbladder carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2016;48(3):1165–1174. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2016.3347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takano J, Morishita A, Fujihara S, Iwama H, Kokado F, Fujikawa K, et al. Galectin-9 suppresses the proliferation of gastric cancer cells in vitro. Oncol Rep. 2016;35(2):851–860. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.4452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Untersmayr E, Bises G, Starkl P, Bevins CL, Scheiner O, Boltz-Nitulescu G, et al. The high affinity IgE receptor Fc epsilonRI is expressed by human intestinal epithelial cells. PLoS One. 2010;5(2):e9023. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dehlink E, Platzer B, Baker AH, Larosa J, Pardo M, Dwyer P, et al. A soluble form of the high affinity IgE receptor, Fc-epsilon-RI, circulates in human serum. PLoS One. 2011;6(4):e19098. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakajima K, Kho DH, Yanagawa T, Zimel M, Heath E, Hogan V, et al. Galectin-3 in bone tumor microenvironment: a beacon for individual skeletal metastasis management. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s10555-016-9622-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marichal T, Tsai M, Galli SJ. Mast cells: potential positive and negative roles in tumor biology. Cancer Immunol Res. 2013;1(5):269–279. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maciel TT, Moura IC, Hermine O. The role of mast cells in cancers. F1000Prime Rep. 2015;7:09. doi: 10.12703/P7-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dalton DK, Noelle RJ. The roles of mast cells in anticancer immunity. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2012;61(9):1511–1520. doi: 10.1007/s00262-012-1246-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khazaie K, Blatner NR, Khan MW, Gounari F, Gounaris E, Dennis K, et al. The significant role of mast cells in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2011;30(1):45–60. doi: 10.1007/s10555-011-9286-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stoyanov E, Uddin M, Mankuta D, Dubinett SM, Levi-Schaffer F. Mast cells and histamine enhance the proliferation of non-small cell lung cancer cells. Lung Cancer. 2012;75(1):38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rajput AB, Turbin DA, Cheang MC, Voduc DK, Leung S, Gelmon KA, et al. Stromal mast cells in invasive breast cancer are a marker of favourable prognosis: a study of 4,444 cases. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;107(2):249–257. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9546-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johansson A, Rudolfsson S, Hammarsten P, Halin S, Pietras K, Jones J, et al. Mast cells are novel independent prognostic markers in prostate cancer and represent a target for therapy. Am J Pathol. 2010;177(2):1031–1041. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang Z, Zhang B, Li D, Lv M, Huang C, Shen GX, et al. Mast cells mobilize myeloid-derived suppressor cells and Treg cells in tumor microenvironment via IL-17 pathway in murine hepatocarcinoma model. PLoS One. 2010;5(1):e8922. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang B, Lei Z, Zhang GM, Li D, Song C, Li B, et al. SCF-mediated mast cell infiltration and activation exacerbate the inflammation and immunosuppression in tumor microenvironment. Blood. 2008;112(4):1269–1279. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-147033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pittoni P, Tripodo C, Piconese S, Mauri G, Parenza M, Rigoni A, et al. Mast cell targeting hampers prostate adenocarcinoma development but promotes the occurrence of highly malignant neuroendocrine cancers. Cancer Res. 2011;71(18):5987–5997. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wei JJ, Song CW, Sun LC, Yuan Y, Li D, Yan B, et al. SCF and TLR4 ligand cooperate to augment the tumor-promoting potential of mast cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2012;61(3):303–312. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1098-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Strouch MJ, Cheon EC, Salabat MR, Krantz SB, Gounaris E, Melstrom LG, et al. Crosstalk between mast cells and pancreatic cancer cells contributes to pancreatic tumor progression. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(8):2257–2265. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu X, Jin H, Zhang G, Lin X, Chen C, Sun J, et al. Intratumor IL-17-positive mast cells are the major source of the IL-17 that is predictive of survival in gastric cancer patients. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e106834. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.de Vries VC, Wasiuk A, Bennett KA, Benson MJ, Elgueta R, Waldschmidt TJ, et al. Mast cell degranulation breaks peripheral tolerance. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(10):2270–2280. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02755.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Teo PZ, Utz PJ, Mollick JA. Using the allergic immune system to target cancer: activity of IgE antibodies specific for human CD20 and MUC1. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2012;61(12):2295–2309. doi: 10.1007/s00262-012-1299-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gatault S, Legrand F, Delbeke M, Loiseau S, Capron M. Involvement of eosinophils in the anti-tumor response. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2012;61(9):1527–1534. doi: 10.1007/s00262-012-1288-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gatault S, Delbeke M, Driss V, Sarazin A, Dendooven A, Kahn JE, et al. IL-18 Is Involved in Eosinophil-Mediated Tumoricidal Activity against a Colon Carcinoma Cell Line by Upregulating LFA-1 and ICAM-1. J Immunol. 2015;195(5):2483–2492. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Legrand F, Driss V, Delbeke M, Loiseau S, Hermann E, Dombrowicz D, et al. Human eosinophils exert TNF-alpha and granzyme A-mediated tumoricidal activity toward colon carcinoma cells. J Immunol. 2010;185(12):7443–7451. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Legrand F, Driss V, Woerly G, Loiseau S, Hermann E, Fournie JJ, et al. A functional gammadeltaTCR/CD3 complex distinct from gammadeltaT cells is expressed by human eosinophils. PLoS One. 2009;4(6):e5926. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Karagiannis SN, Bracher MG, Hunt J, McCloskey N, Beavil RL, Beavil AJ, et al. IgE-antibody-dependent immunotherapy of solid tumors: cytotoxic and phagocytic mechanisms of eradication of ovarian cancer cells. J Immunol. 2007;179(5):2832–2843. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.2832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Erreni M, Mantovani A, Allavena P. Tumor-associated Macrophages (TAM) and Inflammation in Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Microenviron. 2011;4(2):141–154. doi: 10.1007/s12307-010-0052-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Beyer M, Mallmann MR, Xue J, Staratschek-Jox A, Vorholt D, Krebs W, et al. High-resolution transcriptome of human macrophages. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e45466. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Roszer T. Understanding the Mysterious M2 Macrophage through Activation Markers and Effector Mechanisms. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:816460. doi: 10.1155/2015/816460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]