Abstract

Background and significance

The entorhinal cortex (EC), a critical gateway between the neocortex and hippocampus, is one of the earliest regions affected with Alzheimer's disease (AD) associated neurofibrillary tangle pathology. Although our prior work has automatically delineated an MRI-based measure of the EC, it is still unknown whether ante-mortem EC thickness is associated with post-mortem tangle burden within the entorhinal cortex.

Materials and Methods

We evaluated fifty participants from the Rush Memory and Aging Project with ante-mortem structural T1-weighted MRI and post-mortem neuropathological assessments. Here, we focused on thickness within the entorhinal cortex as anatomically defined by our previously developed MRI parcellation system (Desikan-Killiany atlas in FreeSurfer). Using linear regression, we evaluated the association between entorhinal cortex thickness and tangle and amyloid-β load within the entorhinal cortex, medial temporal and neocortical regions.

Results

We found a significant relationship between ante-mortem EC thickness and EC (p-value = 0.006) and medial temporal (MTL) tangles (p-value = 0.002); we found no relationship between EC thickness and EC (p-value = 0.09) and MTL amyloid-β (p-value = 0.09). We also found a significant association between EC thickness and cortical tangles (p-value = 0.003) and amyloid-β (p-value = 0.01). We found no relationship between parahippocampal gyrus thickness and EC (p-value = 0.31) and MTL tangles (p-value = 0.051).

Conclusions

Our findings indicate that EC associated in vivo cortical thinning may represent a marker of post-mortem medial temporal and neocortical AD pathology.

INTRODUCTION

The human entorhinal cortex (EC) plays an integral role in memory formation and serves as the critical gateway between the hippocampus and neocortex1. Located in the medial temporal lobe, the EC constitutes the anterior portion of the parahippocampal gyrus and localized in vivo laterally by the rhinal sulcus, anteriorly by the amygdala and hippocampus and posteriorly by the posterior portion of the parahippocampal gyrus2,3. The EC is one of the earliest affected regions in Alzheimer's disease (AD). Tau associated neurofibrillary tangle (NFT) pathology in AD follows a defined topographic and hierarchical pattern, first affecting the EC and then progressing to anatomically connected limbic and association cortices; in contrast, amyloid-β associated pathology does not involve the EC in the earliest stages of AD but selectively affects the neocortical regions 4,5. Importantly, the association of neuronal volume loss in the EC has been shown to parallel tau-associated tangle pathology (NFTs and neuritic plaques) but not senile plaques (SPs) seen with amyloid-β deposition4.

Structural MRI provides visualization and quantification of volume loss and has been extensively investigated in AD. 6-9, 12-16 Using manually delineated assessments, early studies have shown that volumetric measures of the EC can identify non-demented individuals in the earliest stages of the AD process7–9. Within the last decade, rapid advances in MR post-processing have led to the development of software tools for automatic quantification of human subcortical and neocortical regions10. We have previously developed an MRI-based parcellation atlas for the human cerebral cortex, where have automatically delineated the entorhinal cortex11. The EC region of interest (ROI) from our parcellation atlas correlates with CSF levels of tau and amyloid12, apolipoprotein-E13 and has been used to identify cognitively normal14 and cognitively impaired non-demented individuals who are most likely to progress to clinical AD15,16. However, it is still unknown whether our ante-mortem MRI-based measure of the EC is associated with established post-mortem measures of AD pathology.

In this study, we evaluated the relationship between ante-mortem MRI-based automated measurements of EC thickness and post-mortem measures of neurofibrillary tangle and amyloid-β pathology. To assess the specificity of our EC ROI (anterior portion of the parahippocampal gyrus), we also evaluated the relationship between thickness of the posterior parahippocampal gyrus (referred to as PHG) and EC amyloid-β and tau pathology.

METHODS

Participants

We evaluated participants from the Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP), a community-based longitudinal study of aging, which began in 1997. 17 Details of the clinical and neuropathological evaluations have been reported previously. 17-18 Briefly, all participants underwent a uniform structured clinical evaluation that included a medical history, physical examination with emphasis on neurologic function, and neuropsychological testing (including the Mini-Mental State Examination and 20 other tests). All participants were evaluated in person by a neuropsychologist and a physician with expertise in the evaluation of older persons with cognitive impairment. Based on physician evaluation, and review of the cognitive testing and the neuropsychologist's opinion, participants were classified with respect to AD and other common conditions with the potential to impact cognitive function according to the recommendations of the joint working group of the National Institute of Neurologic and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS/ADRDA). 19 In this manuscript, we focused on 50 participants, clinically defined at baseline (upon study entry) as cognitively normal (n = 25), mild cognitive impairment (MCI, n =18), and probable AD (n = 7) (see Table 1), with concurrent ante-mortem MRI and post-mortem neuropathological assessments. The Rush University Medical Center (RUMC) institutional review board approved the study, and all participants gave written informed consent and signed an Anatomic Gift Act.

Table 1.

Demographic information on participants used in the current study. All values expressed as mean (standard deviation).

| Total subjects (n) | Normals (n = 25) | MCI (n = 18) | AD (n = 7) |

|---|---|---|---|

| % Female | 64% | 55% | 71% |

| Education (years) | 15.6 (3.6) | 14.9 (1.2) | 13.2 (1.2) |

| Age at MRI scan (years) | 87.4 (5.0) | 88.3 (5.4) | 85.2 (4.4) |

| Age at death (years) | 90.3 (4.7) | 91.1 (5.4) | 88.7 (4.9) |

| Years between MRI and death | 2.8 (1.3) | 2.8 (1.2) | 3.6 (1.5) |

| Entorhinal cortex thickness | 1.50 (0.30) | 1.49 (0.27) | 1.40 (0.41) |

| Entorhinal cortex tangle density | 8.9 (6.2) | 12.8 (10.3) | 20.1 (12.9) |

| Entorhinal cortex amyloid-β load | 5.5 (5.1) | 7.1 (5.1) | 7.5 (4.9) |

Imaging Assessments

We assessed previously obtained T1-weighted anatomical data using a 1.5 Tesla MRI scanner (General Electric, Waukesha, WI, USA). For the current study, all ante-mortem MRI data were acquired using a three-dimensional magnetization-prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo (MPRAGE) sequence with parameters echo time (TE) = 2.8 msec, repetition time (TR) = 6.3 msec, preparation time = 1000 msec, flip angle 8°, field of view 24 × 24 cm, 160 slices, 1-mm slice thickness, a 224 × 192 acquisition matrix reconstructed to 256 × 256, and two repetitions. The MRI data were automatically segmented with FreeSurfer 5.0 (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu, for additional details see reference 19). Here, we focused on intracranial volume corrected average thickness of the entire entorhinal cortex and posterior parahippocampal gyrus (average of left and right hemispheres) as delineated using our previously developed automated cortical parcellation atlas11 (Figure 1). In secondary analyses, we also evaluated baseline intracranial volume corrected hippocampal volumes (average of left and right hemispheres). 20

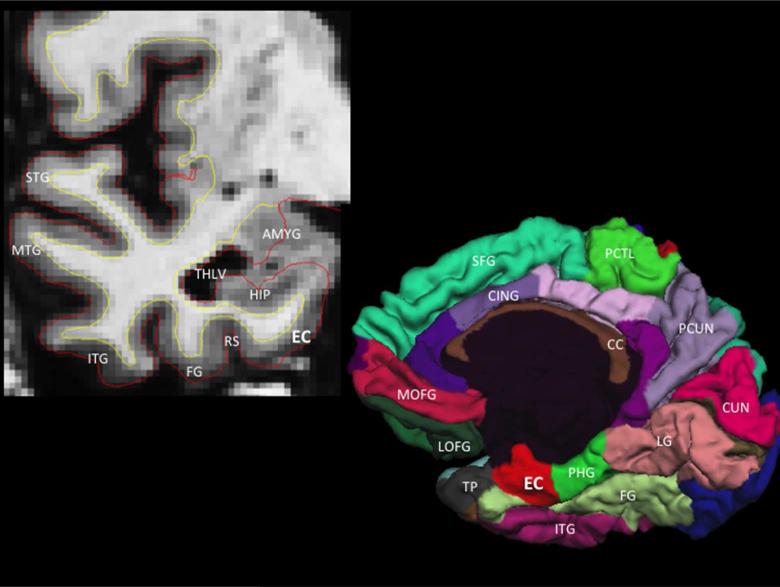

Figure 1.

Coronal T1-weighted MRI illustrating the anatomic location of the entorhinal cortex (EC), which is medial to the rhinal sulcus (RS) and fusiform gyrus (FG) and inferior to the hippocampus (HIP), temporal horn lateral ventricle (THLV) and amygdala (AMYG) (top left panel). Three-dimensional cortical (pial) representation of the right cortical (pial) surface delineating the location of the entorhinal cortex on the medial hemisphere of the cerebral cortex (bottom right panel). STG = superior temporal gyrus, MTG = middle temporal gyrus, ITG = inferior temporal gyrus, TP = temporal pole, PHG = parahippocampal gyrus, LG = lingual gyrus, CUN = cuneus cortex, PCUN = precuneus, FG = fusiform gyrus, PCTL = paracentral lobule, SFG = superior frontal gyrus, MOFG = medial orbitofrontal gyrus, LOFG = lateral orbitofrontal gyrus, CC = corpus callosum, CING = cingulate cortex.

Neuropathological assessments

We used results from previously obtained neuropathological evaluations and focused on amyloid and neurofibrillary tangle pathology within the entorhinal cortex and medial temporal (entorhinal and hippocampus) regions (for additional details on neuropathological measures from the MAP/RUMC please see references 21-22). Briefly, at least two tissue blocks from the entorhinal cortex and hippocampus (CA1/subiculum) were dissected from 1-cm coronal slabs fixed for 48 to 72 hours in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and cut into 20-μm sections. Amyloid-β was labeled with MO0872 (1:100; Dako, Carpinteria, CA) and paired helical filament tau was labeled with AT8 (1:800 in 4% horse serum; Innogenex, San Ramon, CA), an antibody specific for phosphorylated tau. Images of amyloid-β stained sections were captured for quantitative analysis using a systematic random sampling scheme, and calculation of the percent area occupied by amyloid-β immunoreactive pixels was performed. Quantification of tangle density per square millimeter was performed with a stereologic mapping station. We used composite summary measures of the percentage area occupied by amyloid-β and the density of neurofibrillary tangles by averaging the values for each lesion within the entorhinal cortex and medial temporal regions (entorhinal cortex and hippocampus) (for additional details see references 21-22). To evaluate neuropathology within the neocortex and to minimize multiple comparisons, we used a composite measure of tangle density and amyloid-β load within the midfrontal cortex, inferior temporal gyrus, inferior parietal cortex, calcarine cortex, cingulate region, and superior frontal gyrus (cortical tangle density and cortical amyloid-β load).

Statistical analysis

Using linear regression, we evaluated the association between entorhinal cortex thickness and average tangle and amyloid-β load within the entorhinal cortex and medial temporal regions (entorhinal cortex + hippocampus). We also evaluated the relationship between entorhinal cortex thickness and cortical tangle density and amyloid-β load. In secondary analyses, we assessed the association between (posterior) parahippocampal gyrus thickness and tangle and amyloid-β load within the entorhinal cortex and medial temporal regions. In all analyses, we controlled for the effects of age at death, sex and clinical diagnosis.

RESULTS

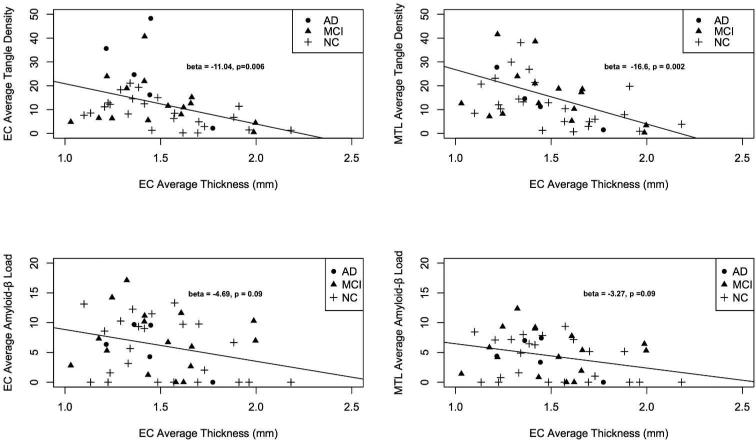

We found a relationship between ante-mortem entorhinal cortex thickness and post-mortem tangle density within the entorhinal cortex (β-coefficient = −11.04, standard error (SE) = 3.78, p-value = 0.006) and medial temporal regions (β-coefficient = −16.67, SE = 5.04, p-value = 0.002); lower EC thickness was associated with increased EC and MTL tangle density (Figure 2). Even after controlling for the effects of hippocampal volume, the relationship between entorhinal cortex thickness and tangle density within the entorhinal cortex (β-coefficient = −9.36, SE = 2.57, p-value = 0.03) and medial temporal regions (β-coefficient = −12.89, SE = 5.64, p-value = 0.02) remained significant. We found no relationship between entorhinal cortex thickness and amyloid-β load within the entorhinal cortex (β-coefficient = −4.69, SE = 2.70, p-value = 0.09) and medial temporal regions (β-coefficient = −3.27, SE = 1.90, p-value = 0.09) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Scatter plots illustrating the relationship between average entorhinal cortex thickness and average tangle density within the entorhinal cortex (EC, top left), medial temporal lobe (MTL, top right), and average amyloid-β load within the EC (bottom left) and MTL (bottom right). Best-fit regression line, beta-coefficients and p-values from the logistic regression model are included (for additional details see manuscript text).

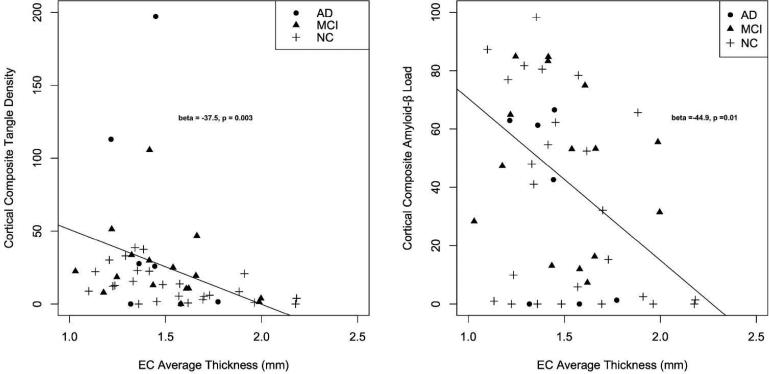

We found a relationship between entorhinal cortex thickness and both cortical tangle density (β-coefficient = −37.5, SE = 12.2, p-value = 0.0003) and amyloid-β load (β-coefficient = −44.9, SE = 17.2, p-value = 0.01) (Figure 3). Even after controlling for the effects of hippocampal volume, the relationship between entorhinal cortex and both cortical tangle density (β-coefficient = −34.4, SE = 7.9, p-value = 0.01) and amyloid-β load (β-coefficient = −44.7, SE = 18.6, p-value = 0.02) remained significant.

Figure 3.

Scatter plots illustrating the relationship between average entorhinal cortex (EC) thickness and composite tangle density (left) and amyloid-β load (right) within the cerebral cortex (see text for details) Best-fit regression line, beta-coefficients and p-values from the logistic regression model are included (for additional details see manuscript text).

In contrast, we found no relationship between ante-mortem parahippocampal gyrus thickness and post-mortem tangle density within the entorhinal cortex (β-coefficient = −4.04, SE = 4.33, p-value = 0.31) and a trend toward significance for medial temporal regions (β-coefficient = −11.52, SE = 5.71, p-value = 0.051). Similarly, we found no relationship between parahippocampal gyrus thickness and amyloid load within the entorhinal cortex (β-coefficient = 1.02, SE = 2.71, p-value = 0.709) and medial temporal regions (β-coefficient = 0.57, SE = 1.91, p-value = 0.766). Similarly, we found no relationship between parahippocampal gyrus thickess and cortical tangle density (β-coefficient = −14.2, SE = 13.5, p-value = 0.30) and amyloid-β load (β-coefficient = −8.7, SE = 18.6, p-value = 0.64).

We performed subgroup analyses within our subset of cognitively normal older participants (n = 25) to evaluate the relationship between MRI measures entorhinal cortex thickness and neuropathology. Similar to our main results, we found a relationship between ante-mortem entorhinal cortex thickness and post-mortem tangle density within the entorhinal cortex (β-coefficient = −10.32, SE = 4.03, p-value = 0.01), medial temporal regions (β-coefficient = −14.48, SE = 6.61, p-value = 0.04) and cortex (β-coefficient = −16.58, SE = 7.03, p-value = 0.02). In contrast, we found no relationship between entorhinal cortex thickness and amyloid load either within the entorhinal cortex (β-coefficient = −5.04, SE = 3.91, p-value = 0.23) or cortex (β-coefficient = −32.26, SE = 22.79, p-value = 0.12).

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate that quantitative in vivo volumetric MRI measurements of the EC are associated with post-mortem measures of entorhinal and neocortical AD pathology. Specifically, these results indicate that lower EC thickness predicts higher post-mortem tangle load. We also found a similar association between EC thickness and post-mortem tangle load within the medial temporal regions (EC + hippocampus). Importantly, this effect remained significant after controlling for hippocampal volume. Finally, we found a robust relationship between EC thickness and cortical tangle and amyloid-β pathology. Rather than representing a specific measure of EC tangle pathology, our combined findings suggest that an ante-mortem MR measure of the entorhinal cortex likely captures Alzheimer's associated pathology within medial temporal and neocortical regions.

Using neuropathological assessments from the same individuals and building on our prior work,12,14 this study suggests that EC associated cortical thinning in AD may represent a marker of tau-associated pathology both within the entorhinal cortex and neocortex. Consistent with the known pattern of amyloid-β deposition in AD, which heavily involves the neocortex with relative sparing of the entorhinal cortex, we found an association between EC thickness and neocortical amyloid-β load but not entorhinal amyloid pathology compatible with the hypothesis that amyloid deposition within the neocortex, rather than the EC, may represent an early component of Alzheimer's pathobiology. 24-25 Our results also suggest that entorhinal cortex thickness may provide independent information about AD pathology even after accounting for hippocampal volume further illustrating the importance of evaluating EC thickness as an early marker of in vivo Alzheimer's neurodegeneration. Interestingly, even among cognitively normal older adults, we found a selective relationship between entorhinal cortex thickness and tangle pathology but not amyloid pathology suggesting the potential usefulness of quantitative MRI measures in preclinical AD.

Accumulating evidence suggests that tau pathology is closely associated with cognitive performance, particularly in the early stages of disease. 26-27 These findings suggest that automated measures of the entorhinal cortex atrophy may reflect regional tau pathology, which will be clinically useful for early AD detection and disease monitoring. Additionally, quantitative measures of EC and medial temporal structures may be combined with genetic, fluid (CSF or plasma) and cognitive parameters for risk stratification, which may become increasingly relevant for AD prevention and therapeutic trials. With the advent and use of novel agents for detecting in vivo tau deposition, 28 volumetric MRI could be integrated with PET imaging to determine whether regional measures of entorhinal atrophy and tau deposition provide independent or complementary information. Finally, beyond AD, automated assessments of the entorhinal cortex can use useful in other disorders of the medial temporal lobe such as medial temporal sclerosis, vascular dementia, and frontotemporal lobar degeneration.

A potential limitation of our study is that our imaging and neuropathology datasets were not co-registered thus limiting the precise correspondence between ante-mortem and post-mortem definition of the EC. Another limitation is the need for validation of our results in independent, community-based samples.

In conclusion, we found a strong association between an automated, ante-mortem MRI-based measure of EC thickness and post-mortem neurofibrillary tangle burden within the entorhinal cortex, medial temporal lobe and neocortex. We additionally detected a relationship between EC thickness and neocortical amyloid-β load. Considered together, our findings serve as a validation of our automated MRI measure of the EC, and suggest that EC associated cortical thinning in AD may represent a marker of medial temporal and neocortical AD neuropathology.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants in the Rush Memory and Aging Project. The work was supported by NIH grants R01AG10161 and R01AG40039. RSD was supported by the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center Junior Investigator Award, ASNR Foundation Alzheimer's Imaging Research Grant Program, RSNA Resident/Scholar Award and NIH/NIDA grant U24DA041123. Support for this research was provided in part by the National Institute for Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (P41EB015896, R01EB006758, R21EB018907, R01EB019956), the National Institute on Aging (5R01AG008122, R01AG016495), the National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01NS0525851, R21NS072652, R01NS070963, R01NS083534, 5U01NS086625), and was made possible by the resources provided by Shared Instrumentation Grants 1S10RR023401, 1S10RR019307, and 1S10RR023043. Additional support was provided by the NIH Blueprint for Neuroscience Research (5U01-MH093765), part of the multi-institutional Human Connectome Project. In addition, BF has a financial interest in CorticoMetrics, a company whose medical pursuits focus on brain imaging and measurement technologies. BF's interests were reviewed and are managed by Massachusetts General Hospital and Partners HealthCare in accordance with their conflict of interest policies. AMD is a founder and holds equity in CorTechs Labs, Inc, and also serves on the Scientific Advisory Board of CorTechs Labs and Human Longevity Inc. The terms of these arrangements have been reviewed and approved by the University of California, San Diego in accordance with its conflict of interest policies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Squire LR, Zola-Morgan S. The medial temporal lobe memory system. Science (80−) 1991;253:1380–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1896849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:239–59. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braak H, Braak E. Staging of alzheimer's disease-related neurofibrillary changes. Neurobiol Aging. 1995;16:271–8. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(95)00021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gómez Isla T, Price JL, McKeel DW, et al. Profound loss of layer II entorhinal cortex neurons occurs in very mild Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 1996;16:4491–500. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-14-04491.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnold SE, Hyman BT, Flory J, et al. The Topographical and Neuroanatomical Distribution of Neurofibrillary Tangles and Neuritic Plaques in the Cerebral Cortex of Patients with Alzheimer's Disease. Cereb Cortex. 1991;1:103–16. doi: 10.1093/cercor/1.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desikan RS, Rafii MS, Brewer JB, et al. An expanded role for neuroimaging in the evaluation of memory impairment. Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34:2075–82. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Killiany RJ, Gomez Isla T, Moss M, et al. Use of structural magnetic resonance imaging to predict who will get Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol. 2000;47:430–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dickerson BC, Goncharova I, Sullivan MP, et al. MRI-derived entorhinal and hippocampal atrophy in incipient and very mild Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2001;22:747–54. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(01)00271-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Killiany RJ, Hyman BT, Gomez-Isla T, et al. MRI measures of entorhinal cortex vs hippocampus in preclinical AD. Neurology. 2002;58:1188–96. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.8.1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fischl B. FreeSurfer. Neuroimage. 2012;62:774–81. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Desikan RS, Ségonne F, Fischl B, et al. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. Neuroimage. 2006;31:968–80. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Desikan RS, Cabral HJ, Hess CP, et al. Automated MRI measures identify individuals with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimers disease. Brain. 2009;132:2048–57. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toledo JB, Da X, Weiner MW. CSF Apo-E levels associate with cognitive decline and MRI changes. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;127:621–32. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1236-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Desikan RS, McEvoy LK, Thompson WK, et al. Amyloid beta associated volume loss occurs only in the presence of phospho-tau. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:657–61. doi: 10.1002/ana.22509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Desikan RS, Fischl B, Cabral HJ, et al. MRI measures of temporoparietal regions show differential rates of atrophy during prodromal AD. Neurology. 2008;71:819–25. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000320055.57329.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Desikan RS, Cabral HJ, Fischl B, et al. Temporoparietal MR imaging measures of atrophy in subjects with mild cognitive impairment that predict subsequent diagnosis of Alzheimer disease. Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30:532–8. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Buchman AS, et al. The Rush Memory and Aging Project: Study design and baseline characteristics of the study cohort. Neuroepidemiology. 2005;25:163–175. doi: 10.1159/000087446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Bang W, Bennett DA. Mixed brain pathologies account for most dementia cases in community-dwelling older persons. Neurology. Dec 11. 2007;69(24):2197–204. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000271090.28148.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKhann G, Drachmann D, Folstein M, et al. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. Report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fischl B, Salat DH, Busa E, et al. Whole brain segmentation: automated labeling of neuroanatomical structures in the human brain. Neuron. Jan 31. 2002;33(3):341–55. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00569-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Wilson RS, et al. Education modifies the association of amyloid but not tangles with cognitive function. Neurology. Sep 27. 2005;65(6):953–5. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000176286.17192.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barnes LL, Schneider JA, Boyle PA, et al. Memory complaints are related to Alzheimer disease pathology in older persons. Neurology. Nov 14. 2006;67(9):1581–5. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000242734.16663.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buckner RL, Snyder AZ, Shannon BJ, et al. Molecular, structural, and functional characterization of Alzheimer's disease: evidence for a relationship between default activity, amyloid, and memory. J Neurosci. Aug 24. 2005;25(34):7709–17. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2177-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jack CR, Jr, Barrio JR, Kepe V. Cerebral amyloid PET imaging in Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol. Nov. 2013;126(5):643–57. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1185-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brier MR, Gordon B, Friedrichsen K, et al. Tau and Aβ imaging, CSF measures, and cognition in Alzheimer's disease. Sci Transl Med. 2016 May 11;8(338):338ra66. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf2362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soldan A, Pettigrew C, Cai Q, et al. Hypothetical Preclinical Alzheimer Disease Groups and Longitudinal Cognitive Change. JAMA Neurol. 2016 Apr 11; doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.0194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holtzman DM, Carrillo MC, Hendrix JA, et al. Tau: From research to clinical development. Alzheimers Dement. Oct. 2016;12(10):1033–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]