Abstract

Control of organ size is of fundamental importance and is controlled by genetic, environmental and mechanical factors. Studies in many species have pointed to the existence of both organ-extrinsic and organ-intrinsic size control mechanisms, which ultimately must coordinate to regulate organ size. Here we discuss organ size control by organ patterning and by the Hippo pathway, which both act in an organ-intrinsic fashion. The influence of morphogens and other patterning molecules couples growth and patterning, whilst emerging evidence suggests that the Hippo pathway controls growth in response to mechanical stimuli and signals emanating from cell-cell interactions. Several points of crosstalk have been reported between signalling pathways that control organ patterning and the Hippo pathway, both at the level of membrane receptors and transcriptional regulators. However, despite substantial progress in the past decade, key questions in the growth control field remain, including precisely how and when organ patterning and the Hippo pathway communicate to control size and whether these communication mechanisms are organ-specific or general. In addition, elucidating mechanisms by which organ-intrinsic cues such as patterning factors and the Hippo pathway interface with extrinsic cues such as hormones to control organ size remains unresolved.

Introduction

Control of organ size is a fundamental aspect of biology and crucial for organism fitness. During development, organs must grow to the appropriate size, whilst many organs of adult organisms also display homeostatic size control mechanisms. Decades of experimentation have identified multiple regulators of organ size. Broadly, these can be grouped into organ extrinsic and organ intrinsic regulators of size. Organ extrinsic regulators act in a humoral fashion to scale the size of multiple organs within an organism. They provide systemic information about organism status, such as nutrition and developmental stage, and include hormones such as insulin and steroids. Organ intrinsic regulators act in a local fashion to modulate the size and shape of individual organs. They provide information about the local cellular environment, including position within an organ and local cell-cell contacts. They were first recognized through transplantation and regeneration experiments and later identified and characterized through genetic studies.

In this review we discuss control of size by organ intrinsic regulators, focussing on organ patterning and the Hippo pathway, which provide key information to cells regarding their local position and cellular environment. As much of our understanding of patterning and Hippo signalling pathways and how they control size has come from analysis of growth of the imaginal discs of Drosophila, we focus on this model system, but also include insights obtained from other organisms.

An understanding of how organ size is determined requires that we be able to explain characteristic parameters of organ growth. The Drosophila wing is perhaps the most intensively studied model for organ growth in all of biology. It originates from a cluster of approximately 30-50 cells set aside in the Drosophila embryo, which form the wing imaginal disc (Worley et al. 2013). The discs grow during the larval stages, in the case of the wing disc to a cluster of approximately 30,000-50,000 cells at the end of larval development (Martín et al. 2009). Perhaps the most basic questions: “What sets the final size of the wing disc?” and “Why do cells stop proliferating when the correct organ size has been reached?” have not yet been definitively answered, but insights have been obtained. Wing size is clearly modulated by both extrinsic and intrinsic mechanisms. For example, starvation, or mutation of components of pathways that control growth in response to nutrient availability, can lead to small but well-proportioned flies, indicating that wing size can be altered based on organ-extrinsic information (Stocker and Hafen 2000). Yet, transplantation and genetic experiments revealed decades ago that an individual wing disc “knows” its size. For example, if a disc is transplanted to a female abdomen, it can be cultured there for an extended period without receiving pulses of the steroid hormone ecdysone that it would normally be exposed to in the larva, triggering metamorphosis. In this environment, it can be observed that an immature wing disc, or a disc in which a fraction of cells have been surgically excised, will grow to its appropriate size and then arrest (Bryant and Levinson 1985). Moreover, genetic experiments imply that the disc-intrinsic unit of size control is actually a fraction of a disc. The wing disc is separated into distinct populations of cells that do not intermix, called compartments, along both anterior-posterior and dorsal-ventral axes. Even if cells of one compartment grow at a substantially different rate from cells in other compartments, a wing of normal size and shape invariably forms (Neufeld et al. 1998; Martín and Morata 2006). Thus, each compartment achieves its correct final size, irrespective of growth rates in neighbouring compartments.

The relationship between organ patterning and growth

When a portion of a developing insect wing or leg is excised, the organ regenerates to replace the missing tissue. Regeneration experiments played a crucial role in establishing the concept that growth of insect appendages is influenced by their patterning, with the extent of regenerative growth dependent upon the disparity between cells newly juxtaposed by surgical manipulations. For example, the growth induced in grafting experiments between cockroach legs cut at different locations revealed that cells proliferate to replace what would normally be intervening cell fates, even when this results in a longer than normal leg (Bohn 1970). These and other studies of regeneration in insects implied that: 1) There is a gradient of positional values within developing organs that enables cells to know their location, 2) Cells are able to recognize when they are next to cells that are not their normal neighbours, 3) Juxtaposition of cells with significantly different positional values stimulates their proliferation (French et al. 1976; Day and Lawrence 2000). The assumption that these observations on regenerative growth could also apply during developmental growth led to models for the control of organ growth by gradients of positional values well before molecular mechanisms controlling organ patterning were identified.

Patterning of the Drosophila wing is established progressively (Fig. 1). The wing imaginal disc is subdivided into anterior and posterior compartments from the origin of the disc during embryogenesis, and into dorsal and ventral compartments at the second larval instar. Short range signalling between cells in neighbouring compartments then establishes specialized cells along the compartment boundaries, which then secrete long range signaling molecules (Lawrence and Struhl 1996). Signaling from posterior to anterior cells is mediated by the Hedgehog pathway, and establishes a stripe of expression of Decapentaplegic (Dpp) in cells along the anterior side of the compartment boundary. Signaling between dorsal and ventral cells is mediated by the Notch pathway, and establishes a stripe of Wingless expression in cells along both sides of the dorsal-ventral (D-V) compartment boundary. Both Dpp and Wingless (Wg) spread from these compartment boundaries, and have been inferred to act as morphogens (Tabata 2001): molecules that are distributed in a concentration gradient across a tissue and specify distinct fates as a function of their concentration. However, while the importance of Dpp as a morphogen has received continued support, experiments establishing that relatively normal wings can form in the presence of uniform Wg (Baena-Lopez et al. 2009), and that Wg that cannot diffuse from cells can still support nearly normal wing development (Alexandre et al. 2014), imply that a spatial gradient of Wg is not required for wing development. Instead, it could be that temporal information is equally or more important, e.g. cells remember that they were exposed to Wg previously, even if they become separated from Wg expressing cells by subsequent growth.

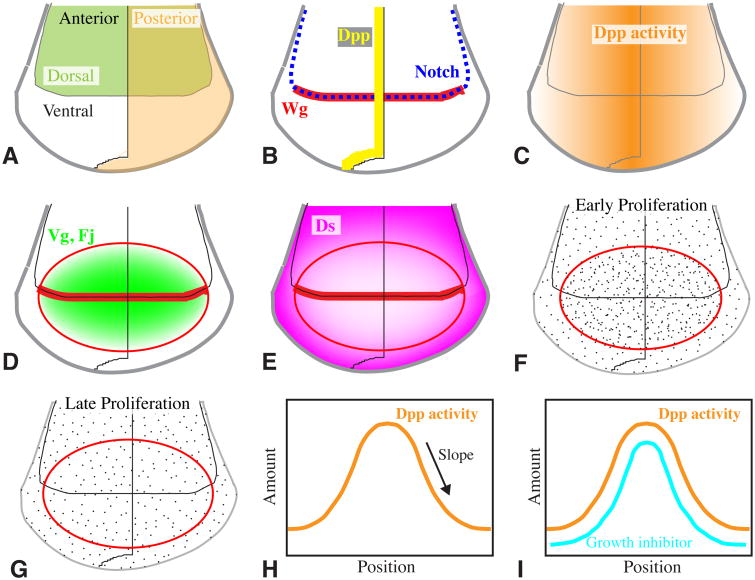

Figure 1. Patterning and Growth in the Wing Imaginal Disc.

A-G Show schematics of the wing region of the Drosophila wing imaginal disc. A) The wing disc is subdivided into distinct lineage-restricted compartments along two orthogonal axes, anterior-posterior and dorsal-ventral. B) Signaling between cells in different compartments establishes specialized cells along the compartment boundaries that organize further wing patterning and growth; Dpp (yellow line) is expressed along the A-P compartment boundary, Notch (dashed blue line) is activated along the D-V compartment boundary, and in the wing pouch (future wing blade) activates expression of Wg (red). C) Dpp spreads from its localized site of synthesis, forming a morphogen gradient (orange) that activates and represses the expression of downstream genes to direct wing patterning and growth. D) The combined action of Dpp, Wg, and Notch activates expression of Vg and Fj (green) in the wing pouch (outlined by a ring of Wg expression, red). Their expression is graded from center (future distal tip of the wing) toward the edges, these gradients are more obvious during early wing development. E) The combined action of Dpp, Wg, and Notch represses expression of Ds (magenta) in the wing pouch, at least in part via Vg. Ds expression is graded from outer (future proximal wing) toward the center. F, G) Distribution of cell proliferation (dots). During early wing disc development cells proliferate more rapidly in the center (F), possibly due to higher levels of growth promoters like Dpp, Wg, and Vg. Later on cell proliferation is roughly uniform throughout the disc (G). H,I) Schematic models for explaining how evenly distributed cell proliferation is achieved despite non-uniform distribution growth promoters like Dpp. H) Growth could be influenced by the absolute amount of Dpp, the slope of the Dpp gradient, or some combination of the two. I) Growth promoted by the amount of Dpp could be uniform if there is a parallel gradient of a growth inhibitor.

The same pathways that pattern the wing along its anterior-posterior (A-P) and D-V axes also promote wing growth. Dpp derives its name from the reduced growth of imaginal discs in mutants (Spencer et al. 1982). Dpp can also be sufficient to increase growth when ectopically expressed, and this growth can be organized into partial wing duplications (Zecca et al. 1995). However, despite extensive examination, the mechanisms by which Dpp actually controls wing growth remain controversial. Dpp pathway activity is graded (Fig. 1), from high in the medial wing disc (near the A-P boundary) to low at the lateral edges, and Dpp is a crucial factor regulating wing growth, yet for most of wing development, growth is relatively evenly distributed throughout the wing disc. How does a growth factor distributed in a gradient promote uniform growth?

One class of models, suggested by the inferred relationship between patterning and growth in regeneration experiments, posits that proliferation is promoted by a read-out of the gradient of pathway activity, rather than the absolute amount of Dpp signalling (Fig. 1H) (Day and Lawrence 2000). In support of such models, when patches of cells express an activated form of the Dpp receptor Thickveins (Tkv), creating a local difference between high and low pathway activity, then cell proliferation can be stimulated in cells along the borders of these patches (Rogulja and Irvine 2005). Moreover, growth can also be stimulated by differences created by lowering rather than raising effective pathway activity, whereas uniformly activating the pathway inhibits rather than stimulates growth in the centre of the wing (Rogulja and Irvine 2005). However, complicating factors include observations that in lateral regions of the wing, cell proliferation can be promoted autonomously by activation of the Dpp pathway, the stimulatory effect of borders between cells with different levels of pathway activity is transient, the differentials in pathway activity used to detect effects on cell proliferation exceed the slope of the endogenous Dpp gradient, and the steepness of the slope of the Dpp gradient normally varies across the disc (Teleman and Cohen 2000; Martin-Castellanos and Edgar 2002; Rogulja and Irvine 2005; Wartlick et al. 2011). Nonetheless, the discovery of the connection between Fat and Hippo signalling (see below), and the ability of Dpp signalling to influence the Fat pathway, implies that there is at least some contribution of a gradient slope to wing growth regulation.

Another class of models, first suggested by Serrano and O'Farrell (1997), posit that uniform growth promotion by a Dpp signalling gradient is achieved through a parallel gradient of a growth inhibitor (Fig. 1I), which as a practical matter would seem to require that the hypothesized inhibitor be regulated by Dpp. Recent years have seen two classes of observations that could fit this hypothesis. When Wartlick et al (2011) quantified Dpp pathway activity and growth rates throughout wing development, they observed that cells divide on average after Dpp pathway activity has increased by 50%. They proposed that this correlation reflects a process in which the amount of Dpp signal needed to promote growth depends upon the amount of Dpp previously received by cells. Although in principle this type of process could generate uniform growth in response to the Dpp gradient, thus far a specific molecular mechanism that would account for the proposed requirement for temporal increases of 50% in Dpp signaling has not yet been uncovered. It is also not clear how well this model can account for the results of experiments in which temporal control over Dpp pathway activity was exerted, or in which Dpp responsiveness was abrogated using Mad mutations (Rogulja and Irvine 2005; Schwank et al. 2012).

A possible growth inhibitory mechanism that is receiving increased attention stems from the idea that mechanical forces play an important role in controlling growth. If tissue compression inhibits growth, and as a tissue grows cells become more compressed, then there is a natural negative feedback mechanism limiting tissue growth (Shraiman 2005; Aegerter-Wilmsen et al. 2007; Hufnagel et al. 2007; Aegerter-Wilmsen et al. 2012). Indeed, rates of cell proliferation do gradually decline as the disc grows (Martín et al. 2009; Wartlick et al. 2011). Thus, to the extent that Dpp promotes growth, it could, with some temporal lag, be proportionally inhibiting growth by increasing tissue compression, especially in central regions of the disc. How tissue compression might inhibit growth is not known for certain, but as discussed below, there is increasing evidence that one possible mechanism is through effects on Hippo signaling (Halder et al. 2012; Rauskolb et al. 2014).

Growth of the wing also depends upon Notch activation along the D-V compartment boundary: Notch signalling is required for wing formation, and creation of ectopic sites of Notch activation can induce non-autonomous wing overgrowth, which remarkably depend upon the location of Notch activation, with activation far from the normal compartment boundary inducing more growth than activation near the normal compartment boundary (Irvine and Vogt 1997). While Notch activation leads to expression of Wg, increased Wg cannot account for the effects of Notch on wing growth. Another key target of Notch signalling in promoting wing growth is the transcription factor Vestigial (Couso et al. 1995; Kim et al. 1996), which, as discussed below, appears to play a key role in linking pathways that control wing patterning to a major growth regulatory pathway, the Hippo pathway.

The Hippo pathway

The most recently defined signalling pathway implicated in organ size control is the Hippo pathway, which is an ancient signalling network that appears to predate the evolution of metazoans (Sebe'-Pedro's et al. 2012) (Fig. 2). It was first discovered in Drosophila in mosaic genetic screens that identified alleles in many genes that exhibited gross overgrowths of epithelial-derived tissues such as the eye, wing, legs and thorax (Justice et al. 1995; Xu et al. 1995; Kango-Singh et al. 2002; Tapon et al. 2002; Harvey et al. 2003; Jia et al. 2003; Pantalacci et al. 2003; Udan et al. 2003). Subsequently, Hippo pathway deregulation was shown to affect the size of many tissues in both flies and mice; these tissues include the Drosophila brain (Reddy et al. 2010; Reddy and Irvine 2011) and the mouse liver, heart, skin, gastro-intestinal tract and brain (Halder and Johnson 2011). Unlike many signalling networks, which are regulated by ligand-receptor interactions, the Hippo pathway appears to be predominantly controlled by a network of proteins that regulate cell adhesion, polarity and the actin cytoskeleton.

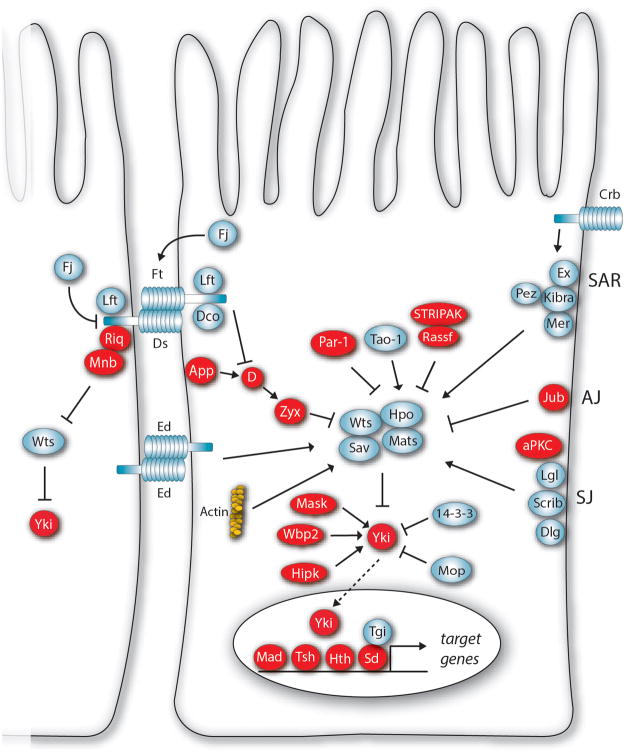

Figure 2. The Drosophila Hippo pathway.

More than 40 proteins have been identified in the Drosophila Hippo pathway. Growth promoting proteins are depicted in red and growth repressors in blue. Many upstream regulatory proteins control activity of core kinase cassette proteins such as the Hippo kinase (Hpo), Salvador (Sav), Mob as tumour suppressor (Mats) and Warts (Wts). The Wts kinase represses tissue growth through phosphorylation-dependent inhibition of Yorkie (Yki). Some Hippo pathway proteins bypass the core kinase cassette and regulate Yki directly. When nuclear, Yki can activate different transcription factors to promote tissue growth. Other abbreviations: aPKC, atypical protein kinase C; App, approximated; Crb, Crumbs; D, Dachs; Dco, Discs overgrown; Dlg, Discs large; Ds, Dachsous; Ed, Echinoid; Ex, Expanded; Fj, Four-jointed; Ft, Fat; Hipk, Homeodomain-interacting protein kinase; Hth, Homothorax; Jub, Ajuba LIM protein; Lft, Lowfat; Lgl, Lethal giant larvae; Mad, Mothers against Decapentaplegic; Mask, Multiple Ankyrin repeats Single KH domain; Mer, Merlin; Mnb, Minibrain; Mop, Myopic; RASSF, Ras-association family; Riq, Riquiqui; Scrib, Scribble; Sd, Scalloped; STRIPAK, Striatin-interacting phosphatase and kinase; Tao-1, Thousand and one amino acid protein; Tgi, Tondu domain-containing Growth Inhibitor; Tsh, Teashirt; Wbp2, WW domain binding protein 2; Zyx, Zyxin. This figure was modified from an earlier publication (Harvey and Hariharan 2012).

The Hippo pathway controls organ size by promoting cell growth and cell proliferation, and inhibiting apoptosis. Later studies also defined important roles for Hippo pathway components in both differentiation and morphogenesis. More than 40 proteins have been identified in both the Drosophila and human Hippo pathways (Fig. 2). For detailed reviews, see (Pan 2010; Halder and Johnson 2011; Zhao et al. 2011; Staley and Irvine 2012; Enderle and McNeill 2013; Harvey et al. 2013; Yu and Guan 2013). The pathway can be classified into three main parts: a central core kinase cassette, downstream transcriptional regulatory proteins and multiple upstream regulatory proteins. Core kinase cassette proteins are the kinases, Warts (Wts) and Hippo (Hpo), and the adaptor proteins, Salvador (Sav) and Mob as tumor suppressor (Mats). They act together to repress tissue growth by phosphorylating and repressing the key transcriptional co-activator Yorkie (Yki). Yki promotes tissue growth and survival in conjunction with several DNA-binding transcription factors, including Scalloped (Sd) Homothorax, and Mad. When not activated by Yki, Sd can act as a transcriptional repressor in conjunction with the Tondu-domain protein Tgi (Koontz et al. 2013).

Regulation of Hippo Signaling by cytoskeletal and junctional proteins

Upstream branches of the Hippo pathway control tissue growth by regulating activity of the core kinase cassette, or by directly impinging on Yki (Grusche et al. 2010; Staley and Irvine 2012; Enderle and McNeill 2013). These upstream branches are complex, and their mode of action is not yet fully understood. Yet it seems clear that many of these upstream regulatory proteins concentrate at cell junctions, and they enable the Hippo pathway to be regulated by cell-cell contact, cell polarity, and the actin cytoskeleton, and thereby enable pathway activity to respond to tissue organization and integrity.

Kibra, Expanded and Merlin

Three proteins, Kibra, Expanded (Ex) and Merlin (Mer), have been reported as having redundant and potentially overlapping roles in activating the Hippo pathway. As well as having similar loss-of-function overgrowth phenotypes, these proteins can physically interact with each other (McCartney et al. 2000; Baumgartner et al. 2010; Genevet et al. 2010; Yu et al. 2010). Kibra, Ex and Mer are also apparently important components of negative feedback signaling within the Hippo pathway, as their transcription is up-regulated by Yki. How they influence activity of the Hippo pathway core kinase cassette is not entirely clear. Initially, overexpression of Kibra, Ex and Mer was shown to stimulate activity of Hpo and Wts, whilst knockdown reduced apical membrane localization of Hpo (Baumgartner et al. 2010; Genevet et al. 2010; Yu et al. 2010). Ex was also found to directly bind to Yki, and postulated to bypass the core kinase cassette to repress Yki (Badouel et al. 2009; Oh et al. 2009). More recently, Mer was shown to recruit Wts to the apical membrane to facilitate activation by the Hpo kinase (Yin et al. 2013). Ex and/or Mer might also regulate Hpo activity via the Tao-1 kinase (Boggiano et al. 2011; Poon et al. 2011), although this warrants investigation in vivo. How Kibra, Ex and Mer proteins are regulated is also unclear, although both Crumbs (Crb) and Fat regulate Ex abundance, and as membrane localization of Crb depends on its interaction with Crb in neighbouring cells, Crb could provide a form of contact-dependent regulation of Ex (Chen et al. 2010; Hafezi et al. 2012). Given links between Mer and the broader Hippo pathway to both contact inhibition and actin (discussed below) Mer has been postulated to provide a link between mechanical information, the actin cytoskeleton and the Hippo pathway. Indeed, actin was recently shown to influence the ability of Mer to bind to Wts and recruit it to the cell membrane (Yin et al. 2013).

Apicobasal polarity proteins

Many proteins that have well defined roles in regulating apicobasal polarity of epithelial cells have been linked to the Hippo pathway. Initially, studies in Drosophila ovaries and larval imaginal discs found that mutations in Discs large (Dlg), Lethal giant larvae (Lgl), Scribble (Scrib) and Crb all caused alterations in Hippo pathway activity (Zhao et al. 2008; Chen et al. 2010; Grzeschik et al. 2010; Ling et al. 2010; Robinson et al. 2010). The mechanism by which these proteins control Hippo pathway activity is not entirely clear. Lgl was proposed to regulate the subcellular distribution of Hpo and Rassf (Grzeschik et al. 2010), and it was also observed that loss of Lgl activates Yki at least in part through Jnk activation (Sun and Irvine 2011). Crb was found to physically interact with Ex and regulate its localization and abundance (Chen et al. 2010; Grzeschik et al. 2010; Ling et al. 2010; Robinson et al. 2010). In mammals, Scrib was found to form physical complexes with the orthologues of both Hpo (MST1 and MST2) and Wts (LATS1 and LATS2) and postulated to serve as a scaffold for the core kinase cassette (Cordenonsi et al. 2011). These different studies provided a conceptual link between epithelial cell polarity and proliferation but the context in which this occurs and its roles in normal development are not entirely clear.

Cell-cell adhesion and junctional proteins

Many of the proteins discussed above localize predominantly to cell junctions where proteins that regulate cell-cell adhesion reside. Several additional such proteins have also been identified as regulators of the Hippo pathway, particularly in mammalian cells. The tight junctions proteins CRB1-3, Angiomotin family proteins AMOT, AMOTL1 and AMOTL2, Zonula occludens (ZO)1 and ZO2 as well as the PATJ/PALS proteins were all defined as regulators of the mammalian Hippo pathway (Yu and Guan 2013). In addition, several adherens junction proteins also control Hippo pathway activity, including β-catenin and E-cadherin in mammalian cells, and Ajuba and Echinoid in Drosophila (Das Thakur et al. 2010; Kim et al. 2011; Schlegelmilch et al. 2011; Yue et al. 2012). In addition to providing a means for Hippo pathway activity to be sensitive to cell-cell contact, junctional proteins also provide a point of crosstalk between Hippo and other pathways. For example, Ajuba family proteins can be phosphorylated by MAPKs of the JNK and ERK family, which influences their ability to bind and inhibit Warts/LATS proteins (Reddy and Irvine 2013; Sun and Irvine 2013).

Hippo pathway control by actin

Studies in both Drosophila tissues and human cultured cells have shown that Hippo pathway activity is sensitive to changes in the nature of the actin cytoskeleton, and that the Hippo pathway can also influence actin (Dupont et al. 2011; Fernandez et al. 2011; Sansores-Garcia et al. 2011; Wada et al. 2011). Mutation or altered expression of actin regulators such as Capping proteins and Diaphanous can influence tissue growth and Yki activity, whilst Hippo pathway mutations cause increased apical actin in wing imaginal disc cells (Fernandez et al. 2011; Sansores-Garcia et al. 2011). In addition, Wts can influence border cell migration in the ovary by repressing activity of the actin regulator Enabled (Lucas et al. 2013). The Hippo pathway is also sensitive to the physical properties of cultured cells. Cells plated at different densities or on substrates that dictate distinct cell shapes, display different activities for the downstream transcriptional regulators of the mammalian Hippo pathway, YAP and TAZ (orthologues of Yki). Stretched cells, with visible actin stress fibres, proliferate and have high YAP/TAZ activity, whereas small compressed cells don't proliferate and have low YAP/TAZ activity (Dupont et al. 2011; Wada et al. 2011). There have been contrasting reports on the mechanism by which actin regulates YAP/TAZ activity. Some studies have implicated Wts and its mammalian orthologues LATS1 and LATS2 (Fernandez et al. 2011; Sansores-Garcia et al. 2011; Wada et al. 2011; Zhao et al. 2012), whereas other studies point to the existence of regulatory mechanisms that act in parallel to the core kinase cassette of the Hippo pathway (Dupont et al. 2011; Aragona et al. 2013). In wing imaginal discs, cytoskeletal tension can modulate Wts activity through recruitment of the Wts inhibitor Jub (Rauskolb et al 2014). Given its potential to link mechanical forces experienced by cells to organ growth, the mechanisms by which the state of the actin cytoskeleton regulates Yki/YAP/TAZ are clearly of great importance. As these mechanisms become better understood it should be possible to assess their contribution to developmental and physiological processes, such as the hypothesized role of mechanical compression in counteracting the influence of growth factors like Dpp to limit organ growth (Aegerter-Wilmsen et al. 2007; Hufnagel et al. 2007).

F-actin may also function as points of crosstalk between Hippo and other pathways. In mammals, G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) have also been found to control Hippo pathway activity (Yu et al. 2012). It is not entirely clear how these receptors signal to the Hippo pathway but it involves the LATS kinases and the actin-regulator Rho, so may occur through effects on the actin cytoskeleton related to those described above. Given the vast number of GPCRs, the potential situation in which these receptors could control pathway activity is large, although this awaits further evaluation in vivo.

The Hippo pathway, organ growth and regeneration

Given the Hippo pathway's ability to link control of proliferation to changes in the actin cytoskeleton and mechanical forces, it has been proposed to regulate proliferation in response to local changes in cell compression and stretching through the tensile state of the actin cytoskeleton. For example, the central (distal) regions of growing wing imaginal discs, where concentrations of growth factors such as Dpp are higher, initially proliferate faster than outer (proximal) cells (Mao et al. 2013) (Fig. 1F). This appears to cause distal cells to be compressed, and proximal cells to become circumferentially stretched (Aegerter-Wilmsen et al. 2012; Legoff et al. 2013; Mao et al. 2013). Mechanical compression has also been proposed as a mechanism that could cause organs to cease growing upon reaching their final size (Shraiman 2005; Aegerter-Wilmsen et al. 2007; Hufnagel et al. 2007; Aegerter-Wilmsen et al. 2012). The contribution of mechanical forces to modulating Hippo pathway activity during organ grow in vivo remains an important area for future studies.

As well as potentially conveying mechanical information to growing organs the Hippo pathway is important for maintaining the integrity of growing organs. The discoveries that the Hippo pathway is responsive to perturbations in fundamental cell biology properties such as cell polarity and cell-cell adhesion, have led to the hypothesis that it promotes epithelial integrity by increasing proliferation in response to death and removal of unfit cells. Indeed, the Hippo pathway activity is de-repressed at the edges of damaged tissues (Grusche et al. 2011; Sun and Irvine 2011), whilst full activity of the key growth promoting transcriptional co-activator proteins of the Hippo pathway (Drosophila Yki and mammalian YAP) are required for tissue regeneration to occur properly (Cai et al. 2010; Grusche et al. 2011; Sun and Irvine 2011). Given the dramatic changes that occur to the actin cytoskeleton, cell polarity, shape and adhesion during tissue damage and regeneration, the Hippo pathway is ideally suited to regulate regenerative tissue growth. In addition, Jnk signaling, which is activated by tissue damage and plays an important role in regeneration, can activate Yki in damaged tissues (Shaw et al. 2010; Staley and Irvine 2010; Grusche et al. 2011; Sun and Irvine 2011).

Crosstalk between the Hippo pathway and patterning factors

Given the profound influence that both the Hippo pathway and patterning molecules like Dpp have on organ growth, cells must have mechanisms for integrating the information they provide. Indeed, crosstalk both at the level of upstream branches of Hippo signaling and at the level of downstream transcription factors has been identified. This crosstalk appears to play important roles in integrating distinct influences on organ growth.

Fat-Dachsous cadherins and Hippo signaling

The first defined transmembrane protein in the Hippo pathway was the atypical cadherin Fat (Bennett and Harvey 2006; Cho et al. 2006; Silva et al. 2006; Willecke et al. 2006; Tyler and Baker 2007), which together with the related cadherin Dachsous (Ds) serve as a ligand-receptor pair (Matakatsu and Blair 2004; Cho et al. 2006; Rogulja et al. 2008; Willecke et al. 2008). Signalling downstream of Fat limits Yki activity by influencing the cellular distribution of the atypical myosin Dachs and the abundance of Wts and Ex (Bennett and Harvey 2006; Cho et al. 2006; Silva et al. 2006; Willecke et al. 2006; Tyler and Baker 2007; Bosch et al. 2014; Rodrigues-Campos and Thompson 2014). Ds-Fat signalling can be bidirectional, with signalling downstream of Ds mediated via the WD40 repeat protein Riquiqui and the Minibrain kinase, which stimulate Yki activity (Degoutin et al. 2013). The net genetic effect of loss of fat or ds is increased Yki activity, but the fact that Fat and Ds binding can potentially both promote and repress Yki activity raises as yet unanswered questions as to the relative roles of these opposing processes in controlling organ growth.

Regulation of Fat-Dachsous signaling by gradients

One remarkable feature of the Ds-Fat pathway is its regulation by proteins expressed in gradients. Fat activity is regulated both by its binding partner, Ds, and by Four-jointed (Fj), which encodes a kinase that modulates Ds-Fat binding (Ishikawa et al. 2008; Brittle et al. 2010; Simon et al. 2010). In the developing wing, Ds expression is graded from proximal (high) to distal (low), and Fat and Fj are graded from distal (high) to proximal (low) (Fig. 1D,E). The gradients of Ds and Fj expression have well established roles in regulating planar cell polarity (PCP) in multiple organs (Matis and Axelrod 2013). Sharp differences in Fj or Ds expression between neighbouring cells created by loss- or gain-of-function clones can also stimulate strong Yki activation and consequent cell proliferation, whereas uniform expression of Ds or Fj can decrease cell proliferation and organ size (Rogulja et al. 2008; Willecke et al. 2008). These observations suggest that Fat-Hippo signaling is sensitive to the slope of the gradient of Ds-Fat pathway regulators.

The membrane localization of pathway components, including the Ds and Fat proteins themselves, and the downstream effector Dachs, becomes polarized along these gradients (Mao et al. 2006; Rogulja et al. 2008; Ambegaonkar et al. 2012; Bosveld et al. 2012; Brittle et al. 2012). Experiments and mathematical modelling indicate that the membrane accumulation of Dachs can be sensitive to both the amounts of Fat and Ds, and their expression gradients (Mao et al. 2006; Mani et al. 2013). Because accumulation of Dachs on membranes downregulates Warts, this provides a mechanism for growth to be influenced by molecules expressed in gradients (Cho et al. 2006; Rogulja et al. 2008; Pan et al. 2013).

Vestigial links wing patterning to Hippo signaling

The influence that Dpp and other wing patterning molecules have on wing growth has been linked to Hippo signaling through the Ds-Fat pathway because activation of Yki along the borders between high and low Dpp pathway activity requires the Ds-Fat pathway effector dachs (Rogulja et al. 2008). Moreover, key wing patterning molecules, including Dpp, Notch, and Wg, can influence Ds and Fj expression (Rogulja et al. 2008; Zecca and Struhl 2010). In the wing, this regulation of Ds and Fj expression appears to be mediated largely through the wing transcription factor Vestigial (Vg). Vg is expressed in a proximal-distal gradient in the developing wing under the control of the Dpp, Notch, and Wg pathways (Couso et al. 1995; Kim et al. 1996; Kim et al. 1997; Zecca and Struhl 2007) (Fig. 1D), and Vg in turn promotes Four-jointed (Fj) expression whilst inhibiting Ds expression (Cho and Irvine 2004; Zecca and Struhl 2010). In addition to its role in setting up Fj and Ds gradients within the developing wing, a “feed-forward” mechanism that operates along the border of Vg expression has been proposed to contribute to wing growth by recruiting cells into the developing wing (Zecca and Struhl 2010). This mechanism relies on the relatively steep border of Fj and Ds expression at the edge of the developing wing, which leads to elevated Yki activity, and in conjunction with Wg, can promote Vg expression in neighbouring cells.

The Ds-Fat pathway is required for normal growth of other insect organs as well, most noticeably the legs. However, the molecular relationship between organ patterning and the regulation of Ds-Fat signaling is less well understood outside of the wing, where Vg is not expressed. The two key regulators of Fat, Ds and Fj, are expressed in gradients within each leg segment (Clark et al. 1995; Villano and Katz 1995; Bando et al. 2009). Wg and Dpp are not candidate regulators of Fj and Ds in legs because their expression patterns are distinct. Instead, the Fj and Ds gradients parallel stripes of Notch activity within each leg segment, and Fj at least has been shown to be affected by Notch signaling, although this regulation may be indirect (Rauskolb and Irvine 1999).

Interactions between transcription factors

A further point of cross-talk between patterning factors and Hippo signalling was revealed with the discovery that Yki and Mad can physically interact with each other, and function together to regulate certain downstream genes involved in promoting organ growth, such as the microRNA gene bantam (Alarcon et al. 2009; Oh and Irvine 2011). In mammalian cells Hippo signalling has also been linked to both BMP and Wnt signalling at multiple levels, including interactions between transcription factors (Varelas et al. 2010a; Varelas et al. 2010b). Intriguingly, this cross-talk can vary depending upon the status of pathway activity. In the nucleus, YAP and TAZ can co-activate transcription together with SMADs or β-catenin (transcription factors of BMP and Wnt pathways). Conversely, when the Hippo pathway is active and YAP and TAZ are cytoplasmic, they can inhibit BMP or Wnt signaling by interacting with SMADs or Dvl in the cytoplasm (Varelas and Wrana 2011; Attisano and Wrana 2013).

Concluding Remarks

One of the challenges in understanding growth control is elucidating how the many factors that influence growth are integrated. Regulatory pathways must act in concert to achieve the right size for specific organs, whilst providing flexibility to adapt to varying physiological conditions e.g. wounding, infection and diet. The past decade has witnessed important advances in the growth control field. Most notably, the Hippo pathway has been recognized as an evolutionarily conserved regulator of tissue growth that responds to fundamental cell biological properties. These include regulation by apicobasal polarity, cell-cell adhesion, F-actin accumulation, and the PCP transmembrane proteins Fat and Ds. It has also been identified as a mechanotransduction pathway that controls tissue growth in response to mechanical stimuli such as stretch or compression, and been shown to be a target of regulation by other signalling mechanisms including G protein and MAPK pathways. The Hippo pathway has thus emerged as an important integrator of multiple growth regulatory signals.

As organ growth is influenced by organ patterning, developmental control of growth requires coordination of information provided by morphogens and other patterning molecules together with the cell biological information that modulates Hippo signaling. Patterning molecules like Wg and Dpp promote growth independently of Hippo signaling, but also cross-talk with the Hippo pathway, both through regulation of Ds-Fat signalling, and through direct interactions between the transcription factors of each pathway. Despite our increased understanding of molecular mechanisms by which Dpp and Wg can promote growth and intersect with other pathways, fundamental questions of how uniform growth is achieved, or why organs stop growing after having reached their correct size, have not yet been clearly answered. However, one intriguing possibility that has emerged is the possibility that mechanical forces experienced by cells are affected by growth, and then feedback and modulate growth through the Hippo pathway.

Much of our knowledge on organ size control has emanated from studies of the Drosophila wing imaginal disc. Future studies will need to address how generally applicable information derived from this tissue is in other Drosophila organs, as well as organs from other species altogether. For example, the transcription factor Vg has been identified as a nexus between the Hippo pathway and patterning factors in control of wing growth, but Vg is not required for the growth of other Drosophila organs. Is there a Vg equivalent in other organs such as the legs and eye, or do the Hippo pathway and patterning factors crosstalk in other organs via different mechanisms altogether?

More broadly, we also lack a clear understanding of how organ patterning and the Hippo pathway integrate with organ extrinsic size control factors such as hormones and nutrition. For example, do they play a role in organ scaling under conditions of dietary stress? Some examples of pathways regulated by organ extrinsic factors, such as G-protein coupled receptors, and the insulin pathway, that can modulate Hippo signalling have been identified (Straβburger et al. 2012; Yu et al. 2012), but further studies are needed to provide a comprehensive understanding of how extrinsic and intrinsic factors are integrated for size regulation. Insights into these outstanding questions will require multi-disciplinary approaches and technical advances such as real-time readouts of activity of different growth control pathways.

Acknowledgments

K.F.H is a Sylvia and Charles Viertel Senior Medical Research Fellow. Research in K.D.I.'s laboratory is supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and NIH grant R01 GM078620.

References

- Aegerter-Wilmsen T, Aegerter CM, Hafen E, Basler K. Model for the regulation of size in the wing imaginal disc of Drosophila. Mech Dev. 2007;124:318–326. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aegerter-Wilmsen T, Heimlicher MB, Smith AC, de Reuille PB, Smith RS, Aegerter CM, Basler K. Integrating force-sensing and signaling pathways in a model for the regulation of wing imaginal disc size. Development (Cambridge, England) 2012;139:3221–3231. doi: 10.1242/dev.082800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alarcon C, Zaromytidou AI, Xi Q, Gao S, Yu J, Fujisawa S, Barlas A, Miller AN, Manova-Todorova K, Macias MJ, et al. Nuclear CDKs drive Smad transcriptional activation and turnover in BMP and TGF-beta pathways. Cell. 2009;139:757–769. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandre C, Baena-Lopez A, Vincent JP. Patterning and growth control by membrane-tethered Wingless. Nature. 2014;505:180–185. doi: 10.1038/nature12879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambegaonkar AA, Pan G, Mani M, Feng Y, Irvine KD. Propagation of Dachsous-Fat Planar Cell Polarity. Curr Biol. 2012;22:1302–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aragona M, Panciera T, Manfrin A, Giulitti S, Michielin F, Elvassore N, Dupont S, Piccolo S. A Mechanical Checkpoint Controls Multicellular Growth through YAP/TAZ Regulation by Actin-Processing Factors. Cell. 2013;154:1047–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attisano L, Wrana JL. Signal integration in TGF-β, WNT, and Hippo pathways. F1000prime reports. 2013;5:17. doi: 10.12703/P5-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badouel C, Gardano L, Amin N, Garg A, Rosenfeld R, Le Bihan T, McNeill H. The FERM-domain protein Expanded regulates Hippo pathway activity via direct interactions with the transcriptional activator Yorkie. Dev Cell. 2009;16:411–420. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baena-Lopez LA, Franch-Marro X, Vincent JP. Wingless promotes proliferative growth in a gradient-independent manner. Science signaling. 2009;2:ra60. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bando T, Mito T, Maeda Y, Nakamura T, Ito F, Watanabe T, Ohuchi H, Noji S. Regulation of leg size and shape by the Dachsous/Fat signalling pathway during regeneration. Development. 2009;136:2235–2245. doi: 10.1242/dev.035204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner R, Poernbacher I, Buser N, Hafen E, Stocker H. The WW Domain Protein Kibra Acts Upstream of Hippo in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2010;18:309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett FC, Harvey KF. Fat cadherin modulates organ size in Drosophila via the Salvador/Warts/Hippo signaling pathway. Curr Biol. 2006;16:2101–2110. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boggiano JC, Vanderzalm PJ, Fehon RG. Tao-1 Phosphorylates Hippo/MST Kinases to Regulate the Hippo-Salvador-Warts Tumor Suppressor Pathway. Dev Cell. 2011;21:888–895. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohn H. Intercalary regeneration and segmental gradients in the extremities ofLeucophaea-larvae (Blattaria) Wilhelm Roux' Archiv. 1970;165:303–341. doi: 10.1007/BF00573677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch JA, Sumabat TM, Hafezi Y, Pellock BJ, Gandhi KD, Hariharan IK. The Drosophila F-box protein Fbxl7 binds to the protocadherin fat and regulates Dachs localization and Hippo signaling. eLife. 2014;3:e03383. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosveld F, Bonnet I, Guirao B, Tlili S, Wang Z, Petitalot A, Marchand R, Bardet PL, Marcq P, Graner F, et al. Mechanical Control of Morphogenesis by Fat/Dachsous/Four-Jointed Planar Cell Polarity Pathway. Science. 2012;336:724–727. doi: 10.1126/science.1221071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brittle A, Thomas C, Strutt D. Planar Polarity Specification through Asymmetric Subcellular Localization of Fat and Dachsous. Curr Biol. 2012;22:907–914. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brittle AL, Repiso A, Casal J, Lawrence PA, Strutt D. Four-jointed modulates growth and planar polarity by reducing the affinity of dachsous for fat. Curr Biol. 2010;20:803–810. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.03.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant PJ, Levinson P. Intrinsic growth control in the imaginal primordia of Drosophila, and the autonomous action of a lethal mutation causing overgrowth. Developmental biology. 1985;107:355–363. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(85)90317-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai J, Zhang N, Zheng Y, de Wilde RF, Maitra A, Pan D. The Hippo signaling pathway restricts the oncogenic potential of an intestinal regeneration program. Genes Dev. 2010;24:2383–2388. doi: 10.1101/gad.1978810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CL, Gajewski KM, Hamaratoglu F, Bossuyt W, Sansores-Garcia L, Tao C, Halder G. The apical-basal cell polarity determinant Crumbs regulates Hippo signaling in Drosophila. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:15810–15815. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004060107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho E, Feng Y, Rauskolb C, Maitra S, Fehon R, Irvine KD. Delineation of a Fat tumor suppressor pathway. Nature genetics. 2006;38:1142–1150. doi: 10.1038/ng1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho E, Irvine KD. Action of fat, four-jointed, dachsous and dachs in distal-to-proximal wing signaling. Development (Cambridge, England) 2004;131:4489–4500. doi: 10.1242/dev.01315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark HF, Brentrup D, Schneitz K, Bieber A, Goodman C, Noll M. Dachsous encodes a member of the cadherin superfamily that controls imaginal disc morphogenesis in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1530–1542. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.12.1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordenonsi M, Zanconato F, Azzolin L, Forcato M, Rosato A, Frasson C, Inui M, Montagner M, Parenti AR, Poletti A, et al. The Hippo transducer TAZ confers cancer stem cell-related traits on breast cancer cells. Cell. 2011;147:759–772. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couso JP, Knust E, Martinez Arias A. Serrate and wingless cooperate to induce vestigial gene expression and wing formation in Drosophila. Current biology: CB. 1995;5:1437–1448. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00281-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das Thakur M, Feng Y, Jagannathan R, Seppa MJ, Skeath JB, Longmore GD. Ajuba LIM proteins are negative regulators of the Hippo signaling pathway. Curr Biol. 2010;20:657–662. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day SJ, Lawrence PA. Measuring dimensions: the regulation of size and shape. Development (Cambridge, England) 2000;127:2977–2987. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.14.2977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degoutin JL, Milton CC, Yu E, Tipping M, Bosveld F, Yang L, Bellaiche Y, Veraksa A, Harvey KF. Riquiqui and minibrain are regulators of the hippo pathway downstream of Dachsous. Nature cell biology. 2013;15:1176–1185. doi: 10.1038/ncb2829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont S, Morsut L, Aragona M, Enzo E, Giulitti S, Cordenonsi M, Zanconato F, Le Digabel J, Forcato M, Bicciato S, et al. Role of YAP/TAZ in mechanotransduction. Nature. 2011;474:179–183. doi: 10.1038/nature10137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enderle L, McNeill H. Hippo gains weight: added insights and complexity to pathway control. Science signaling. 2013;6:re7. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez BG, Gaspar P, Bras-Pereira C, Jezowska B, Rebelo SR, Janody F. Actin-Capping Protein and the Hippo pathway regulate F-actin and tissue growth in Drosophila. Development. 2011;138:2337–2346. doi: 10.1242/dev.063545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French V, Bryant PJ, Bryant SV. Pattern regulation in epimorphic fields. Science (New York, NY) 1976;193:969–981. doi: 10.1126/science.948762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genevet A, Wehr MC, Brain R, Thompson BJ, Tapon N. Kibra Is a Regulator of the Salvador/Warts/Hippo Signaling Network. Dev Cell. 2010;18:300–308. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grusche FA, Degoutin JL, Richardson HE, Harvey KF. The Salvador/Warts/Hippo pathway controls regenerative tissue growth in Drosophila melanogaster. Developmental biology. 2011;350:255–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grusche FA, Richardson HE, Harvey KF. Upstream regulation of the hippo size control pathway. Curr Biol. 2010;20:R574–582. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzeschik NA, Parsons LM, Allott ML, Harvey KF, Richardson HE. Lgl, aPKC, and Crumbs regulate the Salvador/Warts/Hippo pathway through two distinct mechanisms. Curr Biol. 2010;20:573–581. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafezi Y, Bosch JA, Hariharan IK. Differences in levels of the transmembrane protein Crumbs can influence cell survival at clonal boundaries. Developmental biology. 2012;368:358–369. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halder G, Dupont S, Piccolo S. Transduction of mechanical and cytoskeletal cues by YAP and TAZ. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2012;13:591–600. doi: 10.1038/nrm3416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halder G, Johnson RL. Hippo signaling: growth control and beyond. Development. 2011;138:9–22. doi: 10.1242/dev.045500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey KF, Hariharan IK. The hippo pathway. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology. 2012;4:a011288. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a011288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey KF, Pfleger CM, Hariharan IK. The Drosophila Mst ortholog, hippo, restricts growth and cell proliferation and promotes apoptosis. Cell. 2003;114:457–467. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00557-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey KF, Zhang X, Thomas DM. The Hippo pathway and human cancer. Nature reviews Cancer. 2013;13:246–257. doi: 10.1038/nrc3458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hufnagel L, Teleman AA, Rouault H, Cohen SM, Shraiman BI. On the mechanism of wing size determination in fly development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:3835–3840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607134104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine KD, Vogt TF. Dorsal-ventral signaling in limb development. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 1997;9:867–876. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80090-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa HO, Takeuchi H, Haltiwanger RS, Irvine KD. Four-jointed is a Golgi kinase that phosphorylates a subset of cadherin domains. Science. 2008;321:401–404. doi: 10.1126/science.1158159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia J, Zhang W, Wang B, Trinko R, Jiang J. The Drosophila Ste20 family kinase dMST functions as a tumor suppressor by restricting cell proliferation and promoting apoptosis. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2514–2519. doi: 10.1101/gad.1134003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justice RW, Zilian O, Woods DF, Noll M, Bryant PJ. The Drosophila tumor suppressor gene warts encodes a homolog of human myotonic dystrophy kinase and is required for the control of cell shape and proliferation. Genes Dev. 1995;9:534–546. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.5.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kango-Singh M, Nolo R, Tao C, Verstreken P, Hiesinger PR, Bellen HJ, Halder G. Shar-pei mediates cell proliferation arrest during imaginal disc growth in Drosophila. Development. 2002;129:5719–5730. doi: 10.1242/dev.00168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Johnson K, Chen HJ, Carroll S, Laughon A. Drosophila Mad binds to DNA and directly mediates activation of vestigial by Decapentaplegic. Nature. 1997;388:304–308. doi: 10.1038/40906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Sebring A, Esch JJ, Kraus ME, Vorwerk K, Magee J, Carroll SB. Integration of positional signals and regulation of wing formation and identity by Drosophila vestigial gene. Nature. 1996;382:133–138. doi: 10.1038/382133a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim NG, Koh E, Chen X, Gumbiner BM. E-cadherin mediates contact inhibition of proliferation through Hippo signaling-pathway components. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:11930–11935. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103345108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koontz LM, Liu-Chittenden Y, Yin F, Zheng Y, Yu J, Huang B, Chen Q, Wu S, Pan D. The Hippo effector Yorkie controls normal tissue growth by antagonizing scalloped-mediated default repression. Dev Cell. 2013;25:388–401. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence PA, Struhl G. Morphogens, compartments, and pattern: lessons from drosophila? Cell. 1996;85:951–961. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81297-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legoff L, Rouault H, Lecuit T. A global pattern of mechanical stress polarizes cell divisions and cell shape in the growing Drosophila wing disc. Development. 2013;140:4051–4059. doi: 10.1242/dev.090878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling C, Zheng Y, Yin F, Yu J, Huang J, Hong Y, Wu S, Pan D. The apical transmembrane protein Crumbs functions as a tumor suppressor that regulates Hippo signaling by binding to Expanded. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:10532–10537. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004279107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas EP, Khanal I, Gaspar P, Fletcher GC, Polesello C, Tapon N, Thompson BJ. The Hippo pathway polarizes the actin cytoskeleton during collective migration of Drosophila border cells. The Journal of cell biology. 2013;201:875–885. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201210073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mani M, Goyal S, Irvine KD, Shraiman BI. Collective polarization model for gradient sensing via Dachsous-Fat intercellular signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307459110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao Y, Rauskolb C, Cho E, Hu WL, Hayter H, Minihan G, Katz FN, Irvine KD. Dachs: an unconventional myosin that functions downstream of Fat to regulate growth, affinity and gene expression in Drosophila. Development. 2006;133:2539–2551. doi: 10.1242/dev.02427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao Y, Tournier AL, Hoppe A, Kester L, Thompson BJ, Tapon N. Differential proliferation rates generate patterns of mechanical tension that orient tissue growth. The EMBO journal. 2013;32:2790–2803. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín FA, Herrera SC, Morata G. Cell competition, growth and size control in the Drosophila wing imaginal disc. Development (Cambridge, England) 2009;136:3747–3756. doi: 10.1242/dev.038406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín FA, Morata G. Compartments and the control of growth in the Drosophila wing imaginal disc. Development (Cambridge, England) 2006;133:4421–4426. doi: 10.1242/dev.02618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Castellanos C, Edgar BA. A characterization of the effects of Dpp signaling on cell growth and proliferation in the Drosophila wing. Development. 2002;129:1003–1013. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.4.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matakatsu H, Blair SS. Interactions between Fat and Dachsous and the regulation of planar cell polarity in the Drosophila wing. Development. 2004;131:3785–3794. doi: 10.1242/dev.01254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matis M, Axelrod JD. Regulation of PCP by the Fat signaling pathway. Genes & Development. 2013;27:2207–2220. doi: 10.1101/gad.228098.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCartney BM, Kulikauskas RM, LaJeunesse DR, Fehon RG. The neurofibromatosis-2 homologue, Merlin, and the tumor suppressor expanded function together in Drosophila to regulate cell proliferation and differentiation. Development. 2000;127:1315–1324. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.6.1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld TP, de la Cruz AF, Johnston LA, Edgar BA. Coordination of growth and cell division in the Drosophila wing. Cell. 1998;93:1183–1193. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81462-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh H, Irvine KD. Cooperative regulation of growth by Yorkie and Mad through bantam. Dev Cell. 2011;20:109–122. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh H, Reddy BV, Irvine KD. Phosphorylation-independent repression of Yorkie in Fat-Hippo signaling. Dev Biol. 2009;335:188–197. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan D. The hippo signaling pathway in development and cancer. Dev Cell. 2010;19:491–505. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan G, Feng Y, Ambegaonkar AA, Sun G, Huff M, Rauskolb C, Irvine KD. Signal transduction by the Fat cytoplasmic domain. Development (Cambridge, England) 2013;140:831–842. doi: 10.1242/dev.088534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantalacci S, Tapon N, Leopold P. The Salvador partner Hippo promotes apoptosis and cell-cycle exit in Drosophila. Nature cell biology. 2003;5:921–927. doi: 10.1038/ncb1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon CL, Lin JI, Zhang X, Harvey KF. The Sterile 20-like Kinase Tao-1 Controls Tissue Growth by Regulating the Salvador-Warts-Hippo Pathway. Dev Cell. 2011;21:896–906. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauskolb C, Irvine KD. Notch-mediated segmentation and growth control of the Drosophila leg. Developmental Biology. 1999;210:339–350. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauskolb C, Sun S, Sun G, Pan Y, Irvine KD. Cytoskeletal tension inhibits Hippo signaling through an Ajuba-Warts complex. Cell. 2014;158:143–156. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy BV, Irvine KD. Regulation of Drosophila glial cell proliferation by Merlin-Hippo signaling. Development. 2011;138:5201–5212. doi: 10.1242/dev.069385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy BV, Rauskolb C, Irvine KD. Influence of fat-hippo and notch signaling on the proliferation and differentiation of Drosophila optic neuroepithelia. Development. 2010;137:2397–2408. doi: 10.1242/dev.050013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy BVVG, Irvine KD. Regulation of Hippo Signaling by EGFR-MAPK Signaling through Ajuba Family Proteins. Developmental Cell. 2013;24:459–471. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson BS, Huang J, Hong Y, Moberg KH. Crumbs regulates Salvador/Warts/Hippo signaling in Drosophila via the FERM-domain protein expanded. Curr Biol. 2010;20:582–590. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues-Campos M, Thompson BJ. The ubiquitin ligase FbxL7 regulates the Dachsous-Fat-Dachs system in Drosophila. Development. 2014 doi: 10.1242/dev.113498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogulja D, Irvine KD. Regulation of cell proliferation by a morphogen gradient. Cell. 2005;123:449–461. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogulja D, Rauskolb C, Irvine KD. Morphogen control of wing growth through the Fat signaling pathway. Dev Cell. 2008;15:309–321. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansores-Garcia L, Bossuyt W, Wada K, Yonemura S, Tao C, Sasaki H, Halder G. Modulating F-actin organization induces organ growth by affecting the Hippo pathway. The EMBO journal. 2011;30:2325–2335. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlegelmilch K, Mohseni M, Kirak O, Pruszak J, Rodriguez JR, Zhou D, Kreger BT, Vasioukhin V, Avruch J, Brummelkamp TR, et al. Yap1 Acts Downstream of alpha-Catenin to Control Epidermal Proliferation. Cell. 2011;144:782–795. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwank G, Yang SF, Restrepo S, Basler K. Comment on ‘Dynamics of Dpp Signaling and Proliferation Control’. Science (New York, NY) 2012;335:401–401. doi: 10.1126/science.1210997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebe'-Pedro's A, Zheng Y, Ruiz-Trillo I, Pan D. Premetazoan Origin of the Hippo Signaling Pathway. Cell Reports. 2012;1:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano N, O'Farrell PH. Limb morphogenesis: connections between patterning and growth. Current biology: CB. 1997;7:R186–195. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(97)70085-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw RL, Kohlmaier A, Polesello C, Veelken C, Edgar BA, Tapon N. The Hippo pathway regulates intestinal stem cell proliferation during Drosophila adult midgut regeneration. Development. 2010;137:4147–4158. doi: 10.1242/dev.052506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shraiman BI. Mechanical feedback as a possible regulator of tissue growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:3318–3323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404782102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva E, Tsatskis Y, Gardano L, Tapon N, McNeill H. The tumor-suppressor gene fat controls tissue growth upstream of expanded in the hippo signaling pathway. Curr Biol. 2006;16:2081–2089. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon MA, Xu A, Ishikawa HO, Irvine KD. Modulation of Fat:Dachsous binding by the cadherin domain kinase four-jointed. Curr Biol. 2010;20:811–817. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer FA, Hoffmann FM, Gelbart WM. Decapentaplegic: a gene complex affecting morphogenesis in Drosophila melanogaster. Cell. 1982;28:451–461. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90199-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staley BK, Irvine KD. Warts and Yorkie mediate intestinal regeneration by influencing stem cell proliferation. Current biology: CB. 2010;20:1580–1587. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staley BK, Irvine KD. Hippo signaling in Drosophila: recent advances and insights. Developmental dynamics: an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 2012;241:3–15. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker H, Hafen E. Genetic control of cell size. Current opinion in genetics & development. 2000;10:529–535. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00123-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straβburger K, Tiebe M, Pinna F, Breuhahn K, Teleman AA. Insulin/IGF signaling drives cell proliferation in part via Yorkie/YAP. Dev Biol. 2012;367:187–196. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun G, Irvine KD. Regulation of Hippo signaling by Jun kinase signaling during compensatory cell proliferation and regeneration, and in neoplastic tumors. Developmental biology. 2011;350:139–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun G, Irvine KD. Ajuba Family Proteins Link JNK to Hippo Signaling. Science signaling. 2013;6:ra81. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabata T. Genetics of morphogen gradients. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2001;2:620–630. doi: 10.1038/35084577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapon N, Harvey KF, Bell DW, Wahrer DC, Schiripo TA, Haber DA, Hariharan IK. salvador Promotes both cell cycle exit and apoptosis in Drosophila and is mutated in human cancer cell lines. Cell. 2002;110:467–478. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00824-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teleman AA, Cohen SM. Dpp gradient formation in the Drosophila wing imaginal disc. Cell. 2000;103:971–980. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00199-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler DM, Baker NE. Expanded and fat regulate growth and differentiation in the Drosophila eye through multiple signaling pathways. Developmental biology. 2007;305:187–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udan RS, Kango-Singh M, Nolo R, Tao C, Halder G. Hippo promotes proliferation arrest and apoptosis in the Salvador/Warts pathway. Nature cell biology. 2003;5:914–920. doi: 10.1038/ncb1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varelas X, Miller BW, Sopko R, Song S, Gregorieff A, Fellouse FA, Sakuma R, Pawson T, Hunziker W, McNeill H, et al. The Hippo pathway regulates Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Dev Cell. 2010a;18:579–591. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varelas X, Samavarchi-Tehrani P, Narimatsu M, Weiss A, Cockburn K, Larsen BG, Rossant J, Wrana JL. The Crumbs complex couples cell density sensing to Hippo-dependent control of the TGF-beta-SMAD pathway. Dev Cell. 2010b;19:831–844. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varelas X, Wrana JL. Coordinating developmental signaling: novel roles for the Hippo pathway. Trends in Cell Biology. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villano JL, Katz FN. four-jointed is required for intermediate growth in the proximal-distal axis in Drosophila. Development. 1995;121:2767–2777. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.9.2767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada K, Itoga K, Okano T, Yonemura S, Sasaki H. Hippo pathway regulation by cell morphology and stress fibers. Development. 2011;138:3907–3914. doi: 10.1242/dev.070987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wartlick O, Mumcu P, Kicheva A, Bittig T, Seum C, Jülicher F, González-Gaitán M. Dynamics of Dpp signaling and proliferation control. Science (New York, NY) 2011;331:1154–1159. doi: 10.1126/science.1200037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willecke M, Hamaratoglu F, Kango-Singh M, Udan R, Chen CL, Tao C, Zhang X, Halder G. The fat cadherin acts through the hippo tumor-suppressor pathway to regulate tissue size. Curr Biol. 2006;16:2090–2100. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willecke M, Hamaratoglu F, Sansores-Garcia L, Tao C, Halder G. Boundaries of Dachsous Cadherin activity modulate the Hippo signaling pathway to induce cell proliferation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:14897–14902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805201105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worley MI, Setiawan L, Hariharan IK. TIE-DYE: a combinatorial marking system to visualize and genetically manipulate clones during development in Drosophila melanogaster. Development. 2013;140:3275–3284. doi: 10.1242/dev.096057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu T, Wang W, Zhang S, Stewart RA, Yu W. Identifying tumor suppressors in genetic mosaics: the Drosophila lats gene encodes a putative protein kinase. Development. 1995;121:1053–1063. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.4.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin F, Yu J, Zheng Y, Chen Q, Zhang N, Pan D. Spatial organization of Hippo signaling at the plasma membrane mediated by the tumor suppressor Merlin/NF2. Cell. 2013;154:1342–1355. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu FX, Guan KL. The Hippo pathway: regulators and regulations. Genes Dev. 2013;27:355–371. doi: 10.1101/gad.210773.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu FX, Zhao B, Panupinthu N, Jewell JL, Lian I, Wang LH, Zhao J, Yuan H, Tumaneng K, Li H, et al. Regulation of the Hippo-YAP pathway by G-protein-coupled receptor signaling. Cell. 2012;150:780–791. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Zheng Y, Dong J, Klusza S, Deng WM, Pan D. Kibra Functions as a Tumor Suppressor Protein that Regulates Hippo Signaling in Conjunction with Merlin and Expanded. Dev Cell. 2010;18:288–299. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue T, Tian A, Jiang J. The Cell Adhesion Molecule Echinoid Functions as a Tumor Suppressor and Upstream Regulator of the Hippo Signaling Pathway. Developmental cell. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zecca M, Basler K, Struhl G. Sequential organizing activities of engrailed, hedgehog and decapentaplegic in the Drosophila wing. Development (Cambridge, England) 1995;121:2265–2278. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.8.2265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zecca M, Struhl G. Control of Drosophila wing growth by the vestigial quadrant enhancer. Development (Cambridge, England) 2007;134:3011–3020. doi: 10.1242/dev.006445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zecca M, Struhl G. A feed-forward circuit linking wingless, fat-dachsous signaling, and the warts-hippo pathway to Drosophila wing growth. PLoS biology. 2010;8:e1000386. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao B, Li L, Wang L, Wang CY, Yu J, Guan KL. Cell detachment activates the Hippo pathway via cytoskeleton reorganization to induce anoikis. Genes & Development. 2012;26:54–68. doi: 10.1101/gad.173435.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao B, Tumaneng K, Guan KL. The Hippo pathway in organ size control, tissue regeneration and stem cell self-renewal. Nature cell biology. 2011;13:877–883. doi: 10.1038/ncb2303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M, Szafranski P, Hall CA, Goode S. Basolateral junctions utilize warts signaling to control epithelial-mesenchymal transition and proliferation crucial for migration and invasion of Drosophila ovarian epithelial cells. Genetics. 2008;178:1947–1971. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.086983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]