Abstract

Before the prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) program was widely implemented in Malawi, HIV-positive women associated exclusive breastfeeding with accelerated disease progression and felt that an HIV-positive woman could more successfully breastfeed if she had a larger body size. The relationship between breastfeeding practices and body image perceptions has not been explored in the context of the Option B+ PMTCT program, which offers lifelong antiretroviral therapy. We conducted in-depth interviews with 64 HIV-positive women in Lilongwe District, Malawi to investigate body size perceptions, how perceptions of HIV and body size influence infant feeding practices, and differences in perceptions among women in PMTCT and those lost to follow-up (LTFU). Women were asked about current, preferred, and healthy body size perceptions using nine body image silhouettes of varying sizes, and vignettes about underweight and overweight HIV-positive characters were used to elicit discussion of breastfeeding practices. More than 80% of women preferred an overweight, obese, or morbidly obese silhouette, and most women (83%) believed that an obese or morbidly obese silhouette was healthy. While nearly all women believed that an HIV-positive overweight woman could exclusively breastfeed, only about half of women thought that an HIV-positive underweight woman could exclusively breastfeed. These results suggest that perceptions of body size may influence beliefs about a woman’s ability to breastfeed. Given the association between obesity and risk of non-communicable disease, we recommend that counseling and health education for HIV-positive Malawian women focus on culturally sensitive healthy weight messaging and its relationship with breastfeeding practices.

Keywords: breastfeeding, HIV, women, body image, overweight, Africa

INTRODUCTION

In high-income countries, systematic reviews have found that women who are overweight or obese prior to becoming pregnant delay breastfeeding initiation and have a shorter breastfeeding duration (Amir & Donath, 2007; Wojcicki, 2011). Despite increases in overweight among women of reproductive age in low- and middle-income countries (Jaacks, Slining, & Popkin, 2015), research on maternal body size perceptions and infant feeding practices in sub-Saharan Africa has focused on undernutrition and women’s belief that they cannot produce enough milk to exclusively breastfeed if they lack adequate food security (Buskens, Jaffe, & Mkhatshwa, 2007; Webb-Girard et al., 2012; Young et al., 2014). In many parts of Africa, a thin body size is stigmatized because it is associated with illness, especially HIV/AIDS, whereas women prefer an overweight body size because it is perceived to be associated with desirable personality traits, beauty, wealth, and health (Devanathan, Esterhuizen, & Govender, 2013; Holdsworth, Gartner, Landais, Maire, & Delpeuch, 2004; Puoane et al., 2005; Matoti-Mvalo & Puoane, 2011; Draper, Davidowitz, & Goedecke, 2016; Pedro et al., 2016).

This study focuses on body size and infant feeding in the context of HIV. A study in Malawi conducted prior to the widespread implementation of the prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) program found that few women believed that an HIV-positive underweight woman could exclusively breastfeed for six months, whereas many believed that an HIV-positive overweight woman could exclusively breastfeed (Bentley et al., 2005). Another study in Malawi reported that HIV-positive women expressed concerns about the negative impacts of exclusive breastfeeding on a mother’s health, such as weakening of the immune system and faster progression to AIDS (Kafulafula, Hutchinson, Gennaro, & Guttmacher, 2014).

To our knowledge, the interplay between infant feeding practices, body image perceptions, and HIV status has not been explored in the context of current Option B+ PMTCT programs, which offer lifelong antiretroviral therapy (ART) to HIV-positive pregnant and breastfeeding women (WHO, 2013). This remains important in light of the updated HIV and infant feeding guidelines (WHO, 2016), which continue to recommend exclusive breastfeeding until six months, and the rise in overweight and obesity in Malawian women, including those who are HIV-positive (World Health Organization & UNICEF, 2016; Flax et al., 2013; Msyamboza, Kathyola, & Dzowela, 2013; Msyamboza et al., 2011; National Statistical Office (NSO) [Malawi] & ORC Macro, 2005; NSO & ICF Macro, 2011). Our study investigated HIV-positive women’s perceptions of current, preferred, and healthy body sizes and how their perceptions of HIV and body size influences infant and young child feeding (IYCF) practices.

PARTICIPANTS AND METHODS

This study was conducted in two urban and two rural government clinics in Lilongwe District, Malawi from July 2014 to January 2015. Within each category, one small clinic and one large clinic was chosen. Three of the clinics had PMTCT services available once per week. One of the urban clinics had PMTCT services offered daily and was located at the district hospital. Lilongwe District was chosen because of its mature Option B+ program. The range of clinics was selected to improve transferability of findings (Golafshani, 2003).

At the time this study was conducted, the World Health Organization recommended that HIV-positive pregnant women participating in Option B+ to initiate lifelong ART, exclusively breastfeed for 6 months, and continue breastfeeding for the first 12 months of life (World Health Organization, 2010). In Malawi, the Ministry of Health recommended that HIV-positive women in PMTCT continue breastfeeding until 24 months (World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa, 2014). Health education materials on infant and young child feeding were not used in the study clinics and no materials or specific messaging about body size and infant feeding practices were available in Malawi.

Study sample

This paper used data from a study that included 64 in-depth interviews with HIV-positive women. The parent study purposively sampled 32 women currently enrolled in Option B+ and 32 women who were lost to follow-up (LTFU), which equated to eight women in each category per clinic. In qualitative research, a minimum of six interviews is necessary to achieve data saturation (Guest, Bunce, & Johnson, 2006). Thus, the sample size was chosen in order to ensure that we achieved data saturation for each category (Patton, 2001).

Research assistants approached women in PMTCT during a clinic visit and asked them to participate in the interview when their visit was over. Health facility staff used their patient lists to identify LTFU women, defined as women enrolled in PMTCT who had not returned to the clinic for at least 60 days since their last appointment date. The health workers contacted the LTFU women by cell phone or home visits and invited them to participate in the study. Women were eligible if they were ≥ 18 years, HIV-positive, and had a child < 24 months of age.

Data collection

Four Malawian research assistants collected anthropometric data and conducted in-depth interviews with the women. Participants’ weight was measured using Seca 803 digital scales (to 0.1 kg) and height was measured using Seca 213 portable stadiometers (to 0.1 cm). Weight and height were used to calculate participants’ BMI (kg/m2). For in-depth interviews, we used question guides comprised of open-ended questions followed by probes to assist interviewers in obtaining more detailed information. Question guides were developed in English and translated into Chichewa. They were pre-tested with four HIV-positive women and translations were adjusted prior to data collection. Interviews were conducted in Chichewa, transcribed verbatim from digital recordings, and translated into English. The duration of each interview was 30 to 45 minutes.

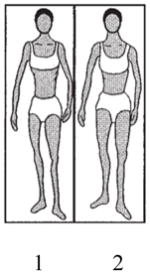

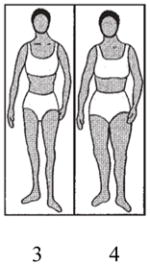

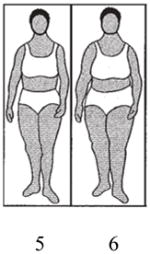

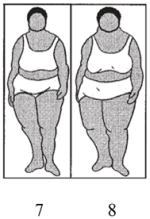

The interviews included questions about body image silhouettes (Bentley et al., 2005; Furnham & Alibhai, 1983; Furnham & Baguma, 1994), vignettes (Bentley et al., 2005; Hughes & Huby, 2002), and the women’s breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices with their child < 24 months of age. We used nine line drawings of body image silhouettes, ranging from very thin to very large shapes, printed on separate laminated cards (Table 1). The silhouettes have been validated in southern Africa (Mciza et al., 2005) and previously used in Malawi by one of the authors (Bentley et al., 2005). The cards were mixed and laid out in random order in a straight line. Questions about the silhouettes included: i) Which figure most closely resembles your figure? ii) Which figure would you want your figure to look like? iii) Which figure do you think shows a healthy woman? Probes were used after questions to investigate the logic behind choices.

Table 1.

Silhouettes by BMI category

| BMI Categories

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Underweight | Normal Weight | Overweight | Obese | Morbidly Obese | |

| BMI Values (kg/m2) | <18.5 | 18.5–24.9 | 25.0–29.9 | 30.0–39.9 | 40.0+ |

| Body Silhouettesa |

|

|

|

|

|

Body silhouettes were pictured on separate laminated cards, shuffled between each question, and laid out in random order in a straight line. Participants were asked: i) Which figure most closely resembles your figure? ii) Which figure would you want your figure to look like? iii) Which figure do you think shows a healthy woman? Body silhouettes reproduced with permission from Bentley et al., 2005.

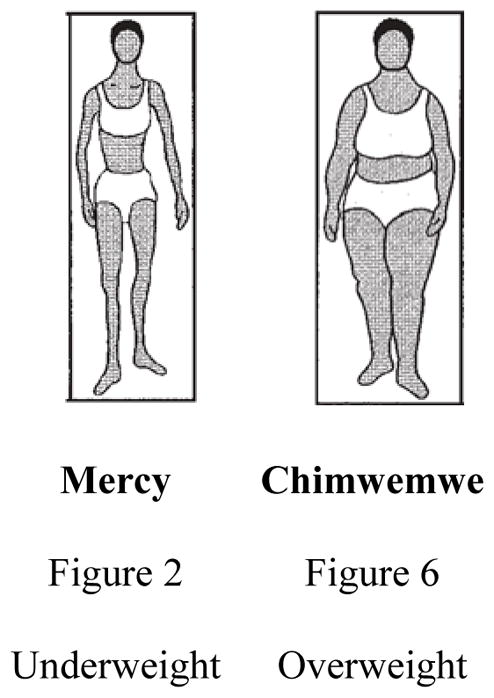

Separate vignettes about two fictional characters, Mercy (body silhouette 2, underweight) and Chimwemwe (body silhouette 6, overweight), were presented to study participants to investigate perceptions of how HIV and body size influence IYCF practices (Figure 1). Participants were asked for their thoughts regarding a nurse’s advice to give only breastmilk until six months and whether they thought that exclusive breastfeeding would affect the characters’ weight and HIV disease progression. In addition, participants were asked if Chimwemwe’s larger size compared to Mercy’s smaller size would make a difference in how she would feed her child.

Figure 1. Body size vignette questions.

Mercy Scenario: Now I would like to tell you a story about Mercy, a 25-year-old mother with HIV who recently had a baby. She is taking ARVs. When her child was born, the nurse advised her to give the baby only breastmilk for the first 6 months. The nurse explained that breastmilk alone provides all the fluids and food the baby needs. This is how Mercy looked (hold up figure #2) before she became pregnant.

Sample Question: Will Mercy, who is thin, be able to give her baby only breastmilk for the first 6 months? Why or why not?

Chimwemwe Scenario: Now there is a second mother, her name is Chimwemwe. She is in the same situation as Mercy. She has HIV, she has recently given birth to a baby, she is taking ARVs, and she has received similar advice about feeding from the nurse. This is how Chimwemwe looked (hold up figure #6) before she became pregnant.

Sample Question: Does the fact that Chimwemwe is fatter/heavier than Mercy make a difference in how Chimwemwe will feed her child? Why/why not?

To assess food insecurity, participants were asked if there are times when they do not have food in their household and do not have money for food. If they responded affirmatively, they were asked how frequently their household is without food and without money for food.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina and from the Malawi Ministry of Health’s National Health Services Research Committee. Research assistants obtained signed or thumb-printed informed consent from each participant immediately prior to the interview.

Data analysis

The interviews were analyzed using thematic content analysis (Patton, 2001). The lead author (SC) and two research assistants used Dedoose (Version 5.0.11, SocioCultural Consultants LLC) to code the English transcripts using deductive codes based on the question guides (e.g., current figure, preferred figure, influence of size on infant feeding practices) (Supplementary Figure 1). Ten percent of interviews were independently coded by two members of the research team and a comparison of the coded transcripts indicated that code application was consistent. Coded data were entered into data matrices (Miles & Huberman, 1994), which were used to investigate patterns in body silhouette choices, thematic responses to vignettes, and differences between PMTCT participants and LTFU women and across clinics.

For quantitative analysis, body image silhouettes were categorized by BMI as underweight (silhouette 1–2), normal weight (silhouette 3–4), overweight (silhouette 5–6), obese (silhouette 7–8), and morbidly obese (silhouette 9) (Bulik et al., 2001; Matoti-Mvalo & Puoane, 2011) (Table 1). Silhouette and anthropometric data (weight, height) were analyzed in Stata (Version 14, College Station, TX; StataCorp LP). Descriptive statistics (mean ± standard deviation) were used to summarize participant responses for body silhouettes. Discrepancies between current and preferred figure and actual figure were analyzed by comparing the BMI categories for body image silhouettes to actual BMI data based on measured weight and height.

RESULTS

We found no differences across clinics or between Option B+ participants and LTFU women. Therefore, the combined data are presented here.

Background Characteristics

On average, participants were 27.0 ± 5.3 years of age, had 6.0 ± 3.2 years of education, and 3.0 ± 1.7 live births. The majority of participants (78%) were married. More than three-quarters of participants experienced household food insecurity; one-half of whom experienced food insecurity at least one day per week.

Actual BMI and Body Size Perceptions

Three-quarters of participants (n=48) had normal BMI values (mean = 22.2 ± 3.0 kg/m2), though BMI ranged from 16.3 kg/m2 (underweight) to 30.4 kg/m2 (obese) (Table 2). The majority of women said that they would prefer their figure to be overweight, obese, or morbidly obese rather than underweight or normal weight (82% vs. 18%). When asked to select a healthy figure, most women chose an obese or morbidly obese silhouette rather than silhouettes of smaller sizes (83% vs. 17%).

Table 2.

Participants’ measured BMI and body silhouette responses

| Underweight | Normal | Overweight | Obese | Morbidly Obese | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Figures 1–2) | (Figures 3–4) | (Figures 5–6) | (Figures 7–8) | (Figure 9) | |

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | |

| Measured BMI (n=64) | 11 (7) | 75 (48) | 13 (8) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Current body silhouette figure (n=62)a | 13 (8) | 48 (30) | 35 (22) | 3 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Preferred body silhouette figure (n=61)b | 0 (0) | 18 (11) | 67 (41) | 11 (7) | 3 (2) |

| Healthy body silhouette Figure (n=63)c | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 17 (11) | 32 (20) | 51 (32) |

Two participants refused to respond to this question.

Two participants refused to respond and one wasn’t asked this question.

One participant refused to respond to this question.

Fewer than half of the women indicated accurate perceptions of their current body sizes (Table 3). About 20% of women perceived their current size to be one BMI category smaller than their actual size based on a comparison of their selected body silhouette and their actual BMI (e.g., overweight women perceived themselves as normal weight), whereas 39% of women perceived themselves to be in a larger BMI category than they were based on their actual BMI (e.g., normal weight women perceived themselves as overweight). Underweight women more often overestimated their current sizes (+1.1 ± 0.7 BMI categories) compared to normal weight women (+0.2 ± 0.7 BMI categories) and overweight women, who underestimated their current sizes by about one-third of a BMI category (−0.4 ± 0.7 BMI categories).

Table 3.

Differences between body silhouette responses and measured BMI

| Number of Categories Away From Measured BMI Categorya,b

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smaller than Actual BMI | No Difference | Larger than Actual BMI | ||||

|

|

||||||

| −1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | |

| Difference in perceived current body silhouette figure and actual BMI (n=62c) | 19 (12) | 42 (26) | 34 (21) | 5 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Difference in preferred body silhouette figure and actual BMI (n=61d) | 5 (3) | 23 (14) | 52 (32) | 13 (8) | 5 (3) | 2 (1) |

Difference between body silhouette responses and actual BMI category based on anthropometric data.

Categories include underweight, normal weight, overweight, obese, and morbidly obese.

Two participants refused to respond to this question.

Two participants refused to respond and one participant was not asked this question.

In comparison to their actual body sizes based on their BMI, more than 70% of women preferred larger sizes (mean +1.0 ± 1.0 BMI categories)based on the silhouette they selected (Table 3). Only three women preferred smaller sizes compared to their actual sizes. On average, underweight women preferred a size that was 2.6 ± 0.8 BMI categories larger compared to normal weight women who preferred a size that was 0.9 ± 0.6 BMI categories larger. Both underweight and normal weight women were more likely to prefer larger sizes than their own sizes compared to overweight women who tended to prefer sizes that were similar to their own sizes (0.1 ± 0.6 BMI categories smaller).

Reasons for Body Size Preferences

Participants said that women with larger body sizes had positive attributes, such as good dietary habits. One woman (normal weight, 20 years) stated, “[Body silhouette 9, morbidly obese] seems that she eats healthy meals.” Other women supported the notion that larger body sizes were related to overall health status. One woman (normal weight, 25 years) said, “[She] looks healthy and a person with a body like [body silhouette 5, overweight] can work properly with no complications or tiring.” Another woman (normal weight, 25 years) concluded, “Out of all the figures here, [body silhouette 9, morbidly obese] is the only healthy woman I see.” Many women also described fatness, chubbiness, and big body size as signs of health. Other positive characteristics attributed to the morbidly obese silhouette included, “She looks as if she doesn’t have any worries” (normal weight, 21 years) and “She is at peace when she is at home” (normal weight, 42 years).

In contrast, a few women stated that it was possible to have too much fat. One woman described her preference for an overweight silhouette as opposed to an obese silhouette, “I heard that when a person is fat there are a lot of fats and oils in the body, which may result in some diseases, like [hypertension] and diabetes” (normal weight, 28 years). Another woman (overweight, 29 years) explained, “I would like to have a medium [overweight] body because sometimes when you are too fat it becomes difficult to walk.”

Influence of Body Size on Infant Feeding Practices

Although both characters were presented in similar vignettes (Figure 1), women perceived the infant feeding practices of Mercy and Chimwemwe quite differently. Ninety-five percent of women believed that Chimwemwe would be able to exclusively breastfeed for six months. In contrast, fewer women (57%) reported that Mercy would be able to exclusively breastfeed, and some specified that she could not manage to exclusively breastfeed because she was thin. However, when asked to directly compare Mercy and Chimwemwe, the majority of women expressed that body size would not affect infant feeding practices.

When asked why Chimwemwe would be able to exclusively breastfeed, women responded, “Her body’s immunity is strong” (overweight, 31 years), “She is energetic” (normal weight, 28 years), and “She has a strong, fresh body” (normal weight, 23 years). One woman (normal weight, 28 years) stated, “She looks healthy so she can never run out of breast milk.” Conversely, women expressed that Mercy’s thin size was indicative of her challenges in feeding her child well. Responses included: “Maybe [Chimwemwe] can easily find food while [Mercy] does not find it easy to find food” (normal weight, 20 years), and similarly, “It’s because [Chimwemwe] can manage to feed her child while [Mercy] cannot afford to buy food for the child. She lacks strength and she would find it difficult to find money to buy other types of food for her child” (normal weight, 33 years). One woman (underweight, 39 years) expressed, “She is too thin and if she [breastfeeds without giving water or thin porridge], she will lose all her energy and die.”

Nonetheless, women provided contrasting responses when asked explicitly whether Chimwemwe’s larger size would make a difference in infant feeding practices. One woman (normal weight, 38 years) explained, “There will be no difference because all women produce breast milk even if the woman is fatter or thinner.” Several women instead emphasized the importance of listening to advice given by health workers, “I don’t think it really depends on who is fat or thin, but [their] interest in following the advice given at the hospital” (underweight, 39 years).

Women’s actual feeding practices in relation to their BMI and their body size preferences aligned with their beliefs that body size did not influence infant feeding practices. The majority of women (81% overall) reported exclusively breastfeeding their infants regardless of their actual body size or perceived current figure (Table 4).

Table 4.

Actual and perceived BMI category by infant feeding method

| Underweight % (n) |

Normal weight % (n) |

Overweight % (n) |

Obese % (n) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual BMI Category | ||||

| Exclusive breastfeedinga | 71 (5) | 81 (39) | 88 (7) | 100 (1) |

| Non-exclusive breastfeeding | 29 (2) | 19 (9) | 12 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Perceived BMI Categoryb | ||||

| Exclusive breastfeedinga | 88 (7) | 87 (26) | 77 (17) | 50 (1) |

| Non-exclusive breastfeeding | 12 (1) | 13 (4) | 23 (5) | 50 (1) |

Exclusive breastfeeding was defined as either current exclusive breastfeeding (for those with children <6 months) or completed exclusive breastfeeding until 6 months (for those with children ≥ 6 months).

Perceived BMI category was determined based on participants’ selection of a body silhouette they believe represented their current body size. Two participants refused to indicate their current figure.

Influence of HIV on Body Size Preferences and Infant Feeding Practices

A few women indicated the context of HIV as an influential factor in determining preferred body size. One woman (overweight, 24 years) described her preference for body silhouette 4 (normal weight): “If I am to choose [body silhouette 9, morbidly obese] people might say she has become too chubby and if I choose [body silhouette 2, underweight] then people would say she has contracted that disease [HIV/AIDS].” Several women also commented that their preference for larger sizes was based on their former sizes (pre-HIV). One woman (underweight, 24 years) stated her preference for a morbidly obese silhouette: “I just want to look nice, as I [used to be heavier]. When I am looking the way I am [now], people just talk about me.”

Others reported the influence of HIV on infant feeding practices. One woman (normal weight, 37 years) reported, “[The decision to breastfeed is] the same so long as the person is taking antiretroviral drugs.” In response to the character vignettes, another woman (normal weight, 23 years) stated, “We do not know whether [Mercy’s] body is thin because she was born like that or because of HIV.”

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study is the first to examine the relationship between body image and infant feeding practices among HIV-positive women in the context of the Option B+ PMTCT program, and the first in sub-Saharan Africa to report a dominant perception of HIV-positive women that morbid obesity is associated with health. In addition, we found that the majority of women preferred figures that were overweight, obese, or morbidly obese. Women were fairly accurate in their self-perceptions of body size, but there was a tendency to perceive current sizes closer to a normal weight range, regardless of actual body sizes. While most women did not believe that body size affected infant feeding practices when asked to directly compare the vignette characters, the majority of women perceived that an overweight woman would be able to exclusively breastfeed. In contrast, several women believed that an underweight woman could not exclusively breastfeed due to a perceived lack of milk, lack of energy, and food insecurity. This matches findings from a previous study by one of the authors (Bentley et al., 2005), suggesting that body size influences HIV-positive women’s beliefs about infant feeding despite widespread access to life-saving and life-prolonging ART for PMTCT. It also suggests that HIV-positive women may have doubts about an HIV-positive underweight woman’s ability to exclusively breastfeed despite global recommendations that all women should exclusively breastfeed until six months (World Health Organization & UNICEF, 2016).

Self-Perceptions of Body Size

When asked to identify their own body sizes using body image silhouettes, fewer than half of women indicated body sizes that matched their actual BMI categories. Although most women chose figures that were within one BMI category of their actual figures (e.g., overweight women indicated normal weight figures), these slightly inaccurate self-perceptions could have important health implications since overweight status is associated with increased risk for non-communicable diseases (World Health Organization, 2011). Similar research studies across sub-Saharan Africa have found that women tend to perceive their figures as smaller than their actual body sizes (Devanathan et al., 2013; Matoti-Mvalo & Puoane, 2011; Muhihi et al., 2012; Njecko, Meyer, Ashu, & Gobte, 2014; Puoane et al., 2005; McCormick et al.. 2014). While our results matched these findings for overweight women, who tended to underestimate their current sizes, we conversely found that underweight women tended to overestimate their current sizes. We are not aware of other studies that have found this relationship; however, these inaccurate self-perceptions could affect a woman’s ability to seek care or assistance for underweight if she falsely perceives herself to have a normal weight when she does not. As an alternative explanation, since the women who participated in our study had children <24 months of age, it is possible that the women who overestimated their sizes had recently lost weight that they had gained during pregnancy, and women who underestimated their sizes had responded in reference to their pre-pregnancy weight.

Idealization of Large Body Sizes

While past research has acknowledged the connection between overweight and obese body sizes and perceived health (Devanathan et al., 2013; Matoti-Mvalo & Puoane, 2011), our study found that a morbidly obese silhouette was seen as healthy. None of the study participants perceived a normal weight silhouette as healthy and one expressly stated that the morbidly obese silhouette alone could be viewed as healthy. Although some women in our study thought that too much body fat could result in poor physical health and chronic disease, our data strongly suggest that the majority of women in this context may idealize large body sizes with excess adiposity. This idealization may relate to the high prevalence of food insecurity found in our study population, since individuals may not feel it is necessary to regulate their food intake when food is not consistently available (Mvo, Dick, & Steyn, 1999). Women in our study indicated their perceptions relating body size to food security when they suggested that Chimwemwe had better access to food compared to Mercy, who they thought might not be able to feed her child well due to a lack of food. In the context of recurrent seasonal food insecurity in Malawi, excess female adiposity may signify to others that a family is wealthy enough to purchase staple foods throughout the year, even during lean times (Puoane et al., 2005).

Several women explained that their preference for larger sizes compared to their actual sizes was based on their pre-HIV weight status, and the fact that they did not want to be thin, which they thought would make them look like they had HIV. This suggests that the preference for overweight, obese, and morbidly obese silhouettes may be due, in part, to avoidance of HIV stigma (Devanathan et al., 2013; Matoti-Mvalo & Puoane, 2011). However, many women also stated that they preferred to be fat for other reasons, including perceived beauty and health. Women also stated that they viewed a morbidly obese silhouette as healthy because she looked at peace and without worries, suggesting a possible psychological benefit. Studies across sub-Saharan Africa have comparably noted the perception that a large female body size is associated with health, beauty, dignity, wealth, respect, happiness, proud parents-in-law, and contented husbands (Holdsworth et al., 2004; Matoti-Mvalo & Puoane, 2011; Mchiza, Goedecke, & Lambert, 2011; Mvo et al., 1999; Puoane et al., 2005; Draper et al., 2015).

Underweight Status and Perceived Ability to Breastfeed

The association between large body sizes and general health status may influence perceptions related to breastfeeding ability. While the clear majority of women expressed that an overweight woman could exclusively breastfeed, nearly half of the women suggested that an underweight woman could not exclusively breastfeed due to inadequate breast milk and depletion of energy stores. This confirms findings reported in Malawi prior to the availability of ART in PMTCT programs (Bentley et al., 2005), and suggests that updated PMTCT guidelines have not changed overall attitudes regarding underweight status and ability to breastfeed. Notably, when women were asked to draw direct comparisons between body size and ability to breastfeed, most of them indicated that body size would not affect infant feeding practices. This perception appears to align with their own practices, which indicate that the women’s actual body sizes did not influence their feeding practices. These findings suggest that women may understand objectively that underweight women who are HIV-positive can successfully breastfeed (Bradley & Vinod, 2008) and they may even apply this in practice, but they may also express underlying, subjective perceptions when asked about underweight women as individuals. It is possible that these subjective perceptions linking underweight and inadequate milk production stem from women’s associations of food insecurity with inadequate milk production (Buskens et al., 2007; Webb-Girard et al., 2012).

Health workers may have a critical role in shaping underlying beliefs about breastfeeding and body size since they play an influential role in guiding infant feeding practices (Flax et al., 2016) and as a primary source of health information (Mvo et al., 1999; Njecko et al., 2014; Pratt, Obeng-Quaidoo, Okigbo, & James, 2000). The context of widespread seasonal food insecurity, common perceptions that larger sizes are most healthy, and stigma of HIV/AIDS should be taken into consideration when developing healthy weight interventions and programs, particularly since no current messaging exists to address how body size might influence infant feeding decisions (Mvo et al., 1999; Puoane et al., 2005). We recommend health workers to clearly state that the recommendations to exclusively breastfeed for six months and continue breastfeed for at least two years hold true regardless of whether women are big or small (World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa, 2014). If women are underweight, health workers should additionally advise on ways to increase caloric density of meals so as to achieve optimal health for the lactating mother and breastfeeding baby. If women are overweight or obese, health workers should confront the associated long-term health implications, such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease, by helping women to reduce their risk (Hu, 2003).

Limitations

Our study had two main limitations. First, because only one study participant was obese and none of the participants were morbidly obese, we were not able to ascertain potential differences between these and other weight categories. We recommend further research to investigate perceptions of body size and infant feeding practices among women in large body size categories and to study the association of body size and feeding practices in a larger sample with adequate power to conduct statistical tests. Second, it is possible that women’s perceptions of their current sizes compared to their actual body sizes might have been confounded by the status of their post-pregnancy weight loss. While we did collect data on age of youngest child, and thus time since delivery, we did not collect data on pre-pregnancy weight. Therefore, we were unable to further investigate this possible relationship.

Conclusions

While many of our themes align well with those documented in previous studies, our study identified several new points for consideration: women regarded a morbidly obese body size as most healthy; women tended to perceive themselves as normal weight regardless of actual weight status; and, women did not believe that body size would affect infant feeding practices, although many expressed the belief that an underweight woman could not exclusively breastfeed when asked in isolation. These findings suggest the importance of culturally sensitive healthy weight messaging in order to successfully promote exclusive breastfeeding for six months and continued breastfeeding for two years, in line with global recommendations (World Health Organization & UNICEF, 2016). In light of the increasing prevalence of overweight and obesity among Malawian women (Flax et al., 2013; Msyamboza et al., 2013; Msyamboza et al., 2011; NSO [Malawi] & ORC Macro, 2005; NSO & ICF Macro, 2011), including those who are HIV-positive, it is critical to convey accurate information to pregnant and lactating women so that the growing obesity epidemic and rise in non-communicable diseases is not compounded by mistaken beliefs surrounding body size and infant feeding practices.

Supplementary Material

KEY MESSAGES.

To our knowledge, this is the first study on HIV-positive women in sub-Saharan Africa to report a predominant perception that morbid obesity is associated with health.

Preference for larger sizes appears to be related to the perception of health and avoidance of HIV stigma.

HIV-positive women may believe that HIV-positive women who are underweight are not able to exclusively breastfeed.

Health encounters with HIV-positive women should reflect culturally-sensitive healthy weight messaging in association with optimal breastfeeding practices.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Francis Chapasuka, John Chapola, Madalo Kamanga, Angela Nyirenda, Odala Sande, and Shadreck Ulaya for their help collecting the data and Ellie Carter and Nainisha Chintalapudi for their assistance coding the interviews.

Source of funding: This study was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development grant 5KHD001441-15 BIRCWH Career Development Program (Flax – Scholar); a development grant from the University of North Carolina Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI50410); a University of North Carolina University Research Council small grant; and the Carolina Population Center (P2C HD050924).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: SE Croffut, G Hamela, I Mofolo, S Maman, MC Hosseinipour, I Hoffman, ME Bentley, VL Flax; no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Statement: VLF, SM, MCH, and IFH designed the study. VLF, GH, IM, and MCH implemented the research in Malawi. MEB contributed to the methodology and the manuscript. SEC analyzed the data and drafted the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Amir LH, Donath S. A systematic review of maternal obesity and breastfeeding intention, initiation and duration. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2007;7(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-7-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley ME, Corneli AL, Piwoz E, Moses A, Nkhoma J, Tohill BC, … Jamieson DJ. Perceptions of the role of maternal nutrition in HIV-positive breast-feeding women in Malawi. The Journal of Nutrition. 2005;135(4):945–949. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.4.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley SEK, Vinod M. HIV and nutrition among women in Sub-Saharan Africa. DHS Analytical Studies. 2008;(16):79. Retrieved from http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/AS16/AS16.pdf.

- Bulik C, Wade T, Heath A, Martin N, Stunkard A, Eaves L. Relating body mass index to figural stimuli: population-based normative data for Caucasians. International Journal of Obesity. 2001;25(10):1517–1524. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buskens I, Jaffe A, Mkhatshwa H. Infant feeding practices: realities and mind sets of mothers in Southern Africa. AIDS Care. 2007;19(9):1101–1109. doi: 10.1080/09540120701336400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devanathan R, Esterhuizen TM, Govender RD. Overweight and obesity amongst Black women in Durban, KwaZulu-Natal: A “disease” of perception in an area of high HIV prevalence. African Journal of Primary Health Care and Family Medicine. 2013;5(1):1–7. doi: 10.4102/phcfm.v5i1.450. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Draper CE, Davidowitz KJ, Goedecke JH. Perceptions relating to body size, weight loss and weight-loss interventions in black South African women: a qualitative study. Public Health Nutrition. 2016;19(03):548–556. doi: 10.1017/S1368980015001688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flax VL, Bentley ME, Chasela CS, Kayira D, Hudgens MG, Kacheche KZ, … Adair LS. Lipid-based nutrient supplements are feasible as a breastmilk replacement for HIV-exposed infants from 24 to 48 weeks of age. The Journal of Nutrition. 2013;143:701–707. doi: 10.3945/jn.112.168245.701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flax VL, Hamela G, Mofolo I, Hosseinipour MC, Hoffman I, Maman S. Infant and Young Child Feeding Counseling, Decision-Making, and Practices Among HIV-Infected Women in Malawi’s Option B+ Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission Program: A Mixed Methods Study. AIDS and Behavior. 2016:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1378-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Furnham A, Alibhai N. Cross-cultural differences in the perception of female body shapes. Psychological Medicine. 1983;13(4):829–837. doi: 10.1017/S0033291700051540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furnham A, Baguma P. Cross-cultural differences in the evaluation of male and female body shapes. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1994;15(1):81–89. doi: 10.1002/1098-108X(199401)15:1<81::AID-EAT2260150110>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golafshani N. Understanding reliability and validity in qualitative research. The Qualitative Report. 2003;8:597–607. [Google Scholar]

- Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field methods. 2006;18(1):59–82. [Google Scholar]

- Holdsworth M, Gartner A, Landais E, Maire B, Delpeuch F. Perceptions of healthy and desirable body size in urban Senegalese women. International Journal of Obesity. 2004;28:1561–1568. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu FB. Overweight and obesity in women: health risks and consequences. Journal of Women’s Health. 2003;12(2):163–172. doi: 10.1089/154099903321576565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes R, Huby M. The application of vignettes in social and nursing research. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2002;37:382–386. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaacks LM, Slining MM, Popkin BM. Recent underweight and overweight trends by rural-urban residence among women in low-and middle-income countries. The Journal of Nutrition. 2015;145(2):352–357. doi: 10.3945/jn.114.203562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kafulafula UK, Hutchinson MK, Gennaro S, Guttmacher S. Maternal and health care workers’ perceptions of the effects of exclusive breastfeeding by HIV positive mothers on maternal and infant health in Blantyre, Malawi. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2014;14(1):247. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matoti-Mvalo T, Puoane T. Perceptions of body size and its association with HIV/AIDS. South African Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2011;24(1):40–45. Retrieved from http://www.ajol.info/index.php/sajcn/article/view/65390. [Google Scholar]

- Mchiza ZJ, Goedecke JH, Lambert EV. Intra-familial and ethnic effects on attitudinal and perceptual body image: a cohort of South African mother-daughter dyads. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):433. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick CL, Francis AM, Iliffe K, Webb H, Douch CJ, Pakianathan M, Macallan DC. Increasing obesity in treated female HIV patients from Sub-Saharan Africa: potential causes and possible targets for intervention. Frontiers in Immunology. 2014;5:507. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Msyamboza KP, Kathyola D, Dzowela T. Anthropometric measurements and prevalence of underweight, overweight and obesity in adult Malawians: nationwide population based NCD STEPS survey. Pan African Medical Journal. 2013;15(1) doi: 10.11604/pamj.2013.15.108.2622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Msyamboza KP, Ngwira B, Dzowela T, Mvula C, Kathyola D, Harries AD, Bowie C. The burden of selected chronic non-communicable diseases and their risk factors in Malawi: nationwide STEPS survey. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e20316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhihi AJ, Njelekela MA, Mpembeni R, Mwiru RS, Mligiliche N, Mtabaji J. Obesity, overweight, and perceptions about body weight among middle-aged adults in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. ISRN Obesity. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70033-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mvo Z, Dick J, Steyn K. Perceptions of overweight African women about acceptable body size of women and children. Curationis. 1999;22(2):27–31. doi: 10.4102/curationis.v22i2.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Statistical Office (NSO) [Malawi] & ORC Macro. Malawi demographic and health survey 2004. Calverton, Maryland: NSO and ORC Macro; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- National Statistical Office (NSO) & ICF Macro. Malawi demographic and health survey 2010. Zomba, Malawi and Calverton, Maryland, USA: NSO and ICF Macro; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Njecko BT, Meyer DJ, Ashu AM, Gobte NJ. An assessment of weight and weight awareness of patients presenting for outpatient care in Cameroon. African Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health. 2014;8(3):134–142. doi: 10.12968/ajmw.2014.8.3.134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, California: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pedro TM, Micklesfield LK, Kahn K, Tollman SM, Pettifor JM, Norris SA. Body image satisfaction, eating attitudes and perceptions of female body silhouettes in rural South African adolescents. PLOS ONE. 2016;11(5):e0154784. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt CB, Obeng-Quaidoo I, Okigbo C, James EL. Health-information sources for Kenyan adolescents : Implications for continuing HIV/AIDS control and prevention in sub-Saharan Africa. The Western Journal of Black Studies. 2000;24(3):131–144. [Google Scholar]

- Puoane T, Fourie J, Shapiro M, Rosling L, Tshaka NC, Oelefse A. “Big is beautiful”-an exploration with urban black community health workers in a South African township. South African Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2005;18(1):6–15. Retrieved from http://www.ajol.info/index.php/sajcn/article/view/34726. [Google Scholar]

- Webb-Girard A, Cherobon A, Mbugua S, Kamau-Mbuthia E, Amin A, Sewuullen DW. Food insecurity is associated with attitudes towards exclusive breastfeeding among women in urban Kenya. Maternal & Child Nutrition. 2012;8(2):199–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2010.00272.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojcicki JM. Maternal prepregnancy body mass index and initiation and duration of breastfeeding: a review of the literature. Journal of Women’s Health. 2011;20(3):341–347. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines on HIV and infant feeding 2010: Principles and recommendations for infant feeding in the context of HIV and a summary of evidence. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight factsheet from the WHO. 2011 Retrieved March 20, 2016, from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa. Implementation of Option B+ for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV: the Malawi experience. Brazzaville, Republic of Congo: WHO Regional Office for Africa; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization & UNICEF. Guideline updates on HIV and infant feeding: the duration of breastfeeding, and support from health services to improve feeding practices among mothers living with HIV. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young SL, Plenty AH, Luwedde FA, Natamba BK, Natureeba P, Achan J, … Clark TD. Household food insecurity, maternal nutritional status, and infant feeding practices among HIV-infected Ugandan women receiving combindation antiretroviral therapy. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2014;18(9):2044–2053. doi: 10.1007/s10995-014-1450-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.