Abstract

Purpose

Whole exome and genome sequencing have transformed the discovery of genetic variants that cause human Mendelian disease, but discriminating pathogenic from benign variants remains a daunting challenge. Rarity is recognised as a necessary, although not sufficient, criterion for pathogenicity, but frequency cutoffs used in Mendelian analysis are often arbitrary and overly lenient. Recent very large reference datasets, such as the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC), provide an unprecedented opportunity to obtain robust frequency estimates even for very rare variants.

Methods

We present a statistical framework for the frequency-based filtering of candidate disease-causing variants, accounting for disease prevalence, genetic and allelic heterogeneity, inheritance mode, penetrance, and sampling variance in reference datasets.

Results

Using the example of cardiomyopathy, we show that our approach reduces by two-thirds the number of candidate variants under consideration in the average exome, without removing true pathogenic variants (false positive rate<0.001).

Conclusion

We outline a statistically robust framework for assessing whether a variant is ‘too common’ to be causative for a Mendelian disorder of interest. We present precomputed allele frequency cutoffs for all variants in the ExAC dataset.

Keywords: Variant interpretation, Clinical Genomics, Allele frequency, Cardiomyopathy, Inherited Cardiovascular Conditions, ExAC

INTRODUCTION

Whole exome and whole genome sequencing have been instrumental in identifying causal variants in Mendelian disease patients1. As every individual harbors ~12,000–14,000 predicted protein-altering variants2, distinguishing disease-causing variants from benign bystanders is perhaps the principal challenge in contemporary clinical genetics. A variant’s low frequency in, or absence from, reference databases is recognised as a necessary, but not sufficient, criterion for variant pathogenicity3,4. The recent availability of very large reference databases, such as the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC)2 dataset, which has characterised the population allele frequencies of 10 million genomic variants through analysis of exome sequencing data from over 60,000 humans, provides an opportunity to obtain robust frequency estimates even for rare variants, improving the theoretical power for allele frequency (AF) filtering in Mendelian variant discovery efforts.

In practice, there exists considerable ambiguity around what AF should be considered “too common”, with the lenient values of 1% and 0.1% often invoked as conservative frequency cutoffs for recessive and dominant diseases respectively5. Population genetics, however, dictates that severe disease-causing variants must be much rarer than these cutoffs, except in cases of bottlenecked populations, balancing selection, or other special circumstances6,7.

It is intuitive that when assessing a variant for a causative role in a dominant Mendelian disease, the frequency of a variant in a reference sample, not selected for the condition, should not exceed the prevalence of the condition8,9. This rule must, however, be refined to account for different inheritance modes, genetic and allelic heterogeneity, and reduced penetrance. In addition, for rare variants, estimation of true population AF is clouded by considerable sampling variance, even in the largest samples currently available. These limitations have encouraged the adoption of very lenient AF filtering approaches10,11, and recognition that more stringent approaches that account for disease-specific genetic architecture are urgently needed8.

Here we present a statistical framework for assessing whether variants are sufficiently rare to cause penetrant Mendelian disease, while accounting for both architecture and sampling variance in observed allele counts. We demonstrate that AF cutoffs well below 0.1% are justified for a variety of human disease phenotypes and that such filters can remove an additional two-thirds of variants from consideration compared to traditionally lenient frequency cutoffs, without discarding true pathogenic variants. We present pre-computed AF filtering values for all variants in the ExAC database, for comparison with user-defined disease-specific thresholds, which are available through the ExAC data browser and for download, to assist others in applying this framework.

METHODS

Defining the statistical framework

We define a two-stage approach to determine whether a variant observed in a reference sample is too common to cause a given disease. First, we define a maximum population AF that we believe is credible for a pathogenic variant, given the genetic architecture of the disease in question. Second, we determine whether the observed allele count in our reference sample is consistent with a variant having this frequency in the population from which the sample was drawn.

For a penetrant dominant Mendelian allele to be disease causing, it cannot be present in the general population more frequently that the disease it causes. Furthermore, if the disease is genetically heterogeneous, it must not be more frequent than the proportion of cases attributable to that gene, or indeed to any single variant. We can therefore define the maximum credible population AF (for a pathogenic allele) as:

where maximum allelic contribution is the maximum proportion of cases potentially attributable to a single allele, a measure of heterogeneity.

For recessive conditions, the maximum AF is defined as:

where maximum genetic contribution represents the proportion of all cases that are attributable to the gene under evaluation, and maximum allelic contribution represents the proportion of cases attributable to that gene that are attributable to an individual variant (see Supplementary Methods for full derivation).

Disease prevalence estimates were obtained from the literature and taken as the highest value reported. Cardiovascular disease variants were modeled with a penetrance of 0.5, corresponding to the reported penetrance of the HCM variant used to illustrate our approach12 and the minimum found across a range of variants/disorders.

We do not know the true population AF of any variant, having only an observed AF in a finite population sample. Moreover, confidence intervals around this observed frequency are problematic to estimate given our incomplete knowledge of the frequency spectrum of rare variants, which is skewed towards very rare variants. For instance, a variant observed only once in a sample of 10,000 chromosomes is much more likely to have a frequency < 1:10,000 than a frequency >1:10,000.2

To address this, we begin by specifying a maximum true AF value we are willing to consider in the population (using the equation above), from which we can estimate the probability distribution for allele counts in a given sample size (see Supplementary Methods). This allows us to set an upper limit on the number of alleles in a sample that is consistent with a given underlying population frequency. For example, a variant with a true population AF of 0.0001 would be expected to occur in a sample of 100,000 alleles ≤15 times with a probability of 0.95.

We therefore computed a maximum tolerated allele count (AC) as the AC at the upper bound of the one-tailed 95% confidence interval (95%CI AC) of a Poisson distribution, for the specified maximum credible AF, given the sample size (observed allele number, AN).

Pre-computing filtering allele frequency values for ExAC

We can reverse this process to determine the maximum true population AF that is consistent with a particular observed sample AC, and we applied this to the ExAC dataset (version 0.3.1). In order to pre-compute af_filter values for all variants in ExAC, we apply a two-step approach to the AC and AN values for each of the five major continental populations, and take the highest result from any population (more explanation in Supplementary Methods).

We use R’s uniroot function to find an AF value (though not necessarily the highest AF value) for which the 95%CI AC is one less than the observed AC.

We loop, incrementing by units of millionths, and return the highest AF value that still gives a 95%CI AC less than the observed AC.

We used adjusted AC and AN, meaning variant calls with GQ≥20 and DP≥10.

Simulated Mendelian variant discovery analysis

To simulate Mendelian variant discovery, we randomly selected 100 individuals from each of five major continental populations and filtered their exomes against filtering AFs derived from the remaining 60,206 ExAC individuals. The subset of individuals was the same as that previously reported2. Predicted protein-altering variants are defined as missense and equivalent (including in-frame indels, start lost, stop lost, and mature miRNA-altering), and protein-truncating variants (nonsense, essential splice site, and frameshift).

Variant curation

Pathogenic and non-conflicted variants were extracted from ClinVar (July 9, 2015 release) as described previously2. ExAC counts were determined by matching on chromosome, position, reference, and alternate alleles. For all variants above the proposed maximum tolerated allele count for HCM, literature from both HGMD and PubMed was reviewed and the level of evidence supporting pathogenicity was curated according to ACMG criteria3.

Calculating odds ratios for HCM variant burden

322 HCM patients and 852 healthy volunteers (both confirmed by cardiac MRI) recruited to the NIHR Royal Brompton cardiovascular BRU were sequenced using the IlluminaTruSight Cardio Sequencing Kit13 on Illumina MiSeq and NextSeq platforms. This study had ethical approval (REC: 09/H0504/104+5) and informed consent was obtained for all subjects. The number of rare variants in the eight sarcomeric genes associated with HCM (MYBPC3, MYH7, TNNT2, TNNI3, MYL2, MYL3, TPM1 and ACTC1) were calculated for all protein altering variants (frameshift, nonsense, splice donor/acceptor, missense and in-frame insertions/deletions), with case/control odds ratios calculated separately for non-overlapping ExAC AF bins with the following breakpoints: 4x10−5, 1x10−4, 5x10−4 and 1x10−3. Odds Ratios were calculated as OR=(cases with variant/cases without variant)/(controls with variant/controls without variant).

RESULTS

Application and validation in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

Defining maximum credible population AF

We illustrate our generalisable approach using the dominant cardiac disorder hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), which has an estimated prevalence of 1 in 500 in the general population14. As there have been previous large-scale genetic studies of HCM, with series of up to 6,179 individuals14,15, we can assume that no newly identified variant will be more frequent in cases that those identified to date (at least for well-studied ancestries), allowing us to define the maximum contribution of any single variant to the disorder. In these series, the largest proportion of cases is attributable to the missense variant MYBPC3 c.1504C>T (p.Arg502Trp), found in 104/6179 HCM cases (1.7%; 95%CI 1.4–2.0%)14,15. We therefore take the upper bound of this proportion (0.02) as an estimate of the maximum allelic contribution in HCM (Table 1). Our maximum expected population AF for this allele, assuming penetrance 0.5 as previously reported12, is 1/500 x 1/2 (dividing prevalence per individual by the number of chromosomes per individual) x 0.02 x 1/0.5 = 4.0x10−5, which we take as the maximum credible population AF for any causative variant for HCM (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Details of the most prevalent pathogenic variants in case cohorts for five cardiac conditions. Shown along with the frequency in cases is the estimated population allele frequency (calculated as: case frequency x disease prevalence x 1/2 x 1/variant penetrance) and the observed frequency in the ExAC dataset.

| Disease | Prevalence | Commonest causative variant | Case count | Case frequency (95% CI) | Penetrance* | Expected population frequency | Model predicted maximum ExAC AC | Observed ExAC AC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCM | 1/500 | MYBPC3:c.1504C>T | 104/6179 | 1.7% (1.4–2.0%) | 0.5 | 3.4x10-5 (2.7–4.0x10-5) | 9 | 3 |

| DCM | 1/250 | TNNT2:c.629_631delAGA | 18/1254 | 1.4% (0.78–2.1%) | 0.5 | 5.6x10-5 (3.1–8.4x10-5) | 16 | 0 |

| ARVC | 1/1000 | PKP2:c.2146-1G>C | 24/361 | 6.7% (4.1–9.2%) | 0.5 | 6.7x10-5 (4.1–9.2x10-5) | 17 | 6 |

| LQTS | 1/2000 | KCNQ1:c.797T>C | 30/2500 | 1.2% (0.77–1.6%) | 0.5 | 6.0x10-6 (3.9–8.2x10-6) | 3 | 0 |

| Brugada | 1/1000 | SCN5A:c.5350G>A | 14/2111 | 0.66% (0.32–1.0%) | 0.5 | 6.6x10-6 (0.32–1.0x10-5) | 3 | 0 |

As penetrance estimates for individual variants are not widely available, we have applied an estimate of 0.5 across these cardiac disorders (see Supplementary Information).

HCM - hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; DCM - dilated cardiomyopathy; ARVC - arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy; LQTS - long QT syndrome. Case cohorts and prevalence estimates (taken as the highest value reported) were obtained from: HCM14,15, DCM14,15,26, ARVC15,27, LQTS28,29 and Brugada30,31.

Controlling for sample variation

To apply this threshold while remaining robust to chance variation in observed allele counts, we ask how many times a variant with population AF of 4.0x10−5 can be observed in a random population sample (Methods). At a 5% error rate, this yields a maximum tolerated allele count of 9, assuming 50% penetrance (5 for fully penetrant alleles) for variants genotyped in the full ExAC cohort (sample size=121,412 chromosomes). The MYBPC3:c.1504C>T variant is observed 3 times in ExAC (freq=2.49x10−5;Table 1).

To facilitate these calculations, we have produced an online calculator (http://cardiodb.org/alleleFrequencyApp) that will compute maximum credible population AF and maximum sample allele count for a user-specified genetic architecture, and conversely allow users to dynamically explore what genetic architecture(s) might be most compatible with an observed variant having a causal role in disease.

Assessing the accuracy of our approach

For all diseases with case series that permitted us to define the genetic architecture, the commonest variant in the case series was well within the calculated maximum allele count in ExAC (Table 1).

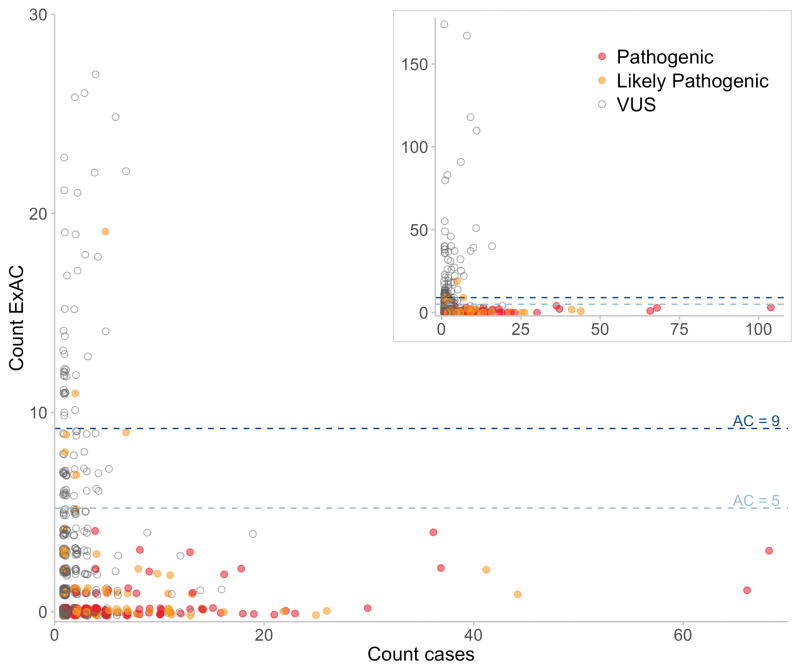

To assess the HCM thresholds empirically, we explored the ExAC AF spectrum of 1132 distinct autosomal variants, identified in 6179 published HCM cases referred for diagnostic sequencing, and individually assessed and clinically reported according to international guidelines14,15. 477/479 (99.6%) variants reported as ‘Pathogenic’ or ‘Likely Pathogenic’ fell below our threshold (Figure 1), including all variants with a clear excess in cases. The 2 variants historically classified as ‘Likely Pathogenic’, but prevalent in ExAC in this analysis, were reassessed using contemporary ACMG criteria: there was no strong evidence in support of pathogenicity, and they were reclassified in light of these findings (Table S1). This analysis identifies 66/653 (10.1%) VUS that are very unlikely to be causative for HCM.

Figure 1.

Plot of ExAC allele count (all populations) against case allele count for variants classified as VUS, Likely Pathogenic or Pathogenic in 6179 HCM cases. The dotted lines represent the maximum tolerated ExAC allele counts in HCM for 50% (dark blue) and 100% penetrance (light blue). Variants are colour coded according to reported pathogenicity. Where classifications from contributing laboratories were discordant the more conservative classification is plotted. The inset panel shows the full dataset, while the main panel expands the region of primary interest.

The above analysis applied a single global allele count limit of 9 for HCM, however, as AFs differ between populations, filtering based on frequencies in individual populations may provide greater power2. For example, a variant relatively common in any one population is unlikely pathogenic, even if rare in other populations, provided the disease prevalence and architecture is consistent across populations. We therefore compute a maximum tolerated AC for each distinct sub-population of our reference sample, and filter based on the highest AF observed in any major continental population (see Methods).The tightness of the Poisson distribution used to compute maximum tolerated allele count is a function of sample size, and thus our approach is more conservative when allele number is lower, thus avoiding inappropriately filtering variants due to chance observation of a few alleles in a smaller sub-population or at a poorly genotyped site (see Supplementary Note 3).

To further validate this approach, we examined all 601 variants identified in ClinVar16 as “Pathogenic” or “Likely Pathogenic” and non-conflicted for HCM. 558 (93%) were sufficiently rare when assessed as described. 43 variants were insufficiently rare in at least one ExAC population, and were therefore re-curated. 42 of these had no segregation or functional data sufficient to demonstrate pathogenicity in the heterozygous state, and would be classified by the contemporary ACMG framework as VUS at most. The remaining variant (MYBPC3:c.3330+5G>C) had convincing evidence of pathogenicity, though with uncertain penetrance (see Supplementary Methods), and was observed twice in the African/African American ExAC population. This fell outside the 95% confidence interval for an underlying population frequency <4x10−5, but within the 99% confidence threshold: a single outlier due to stochastic variation is unsurprising given that these nominal probabilities are not corrected for multiple testing across 601 variants. In light of our updated assessment, 20 variants were reclassified as Benign/Likely Benign and 22 as VUS according to the American College for Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) guidelines for variant interpretation3 (Table S1).

After curating variants above our calculated HCM threshold, the false positive rate was 0/477 (0.000; 95%CI 0.000–0.008) and 1/559 (0.002; 95%CI 0.000–0.010) for the published HCM cohort and ClinVar data respectively.

Extending this approach to other disorders

This framework relies on estimation of the genetic architecture of a condition, which may not be well described. For diseases where large case series are absent, we can estimate the genetic architecture parameters by extrapolating from similar disorders and/or variant databases.

Where disease-specific variant databases exist, we can use these to estimate the maximum allelic contribution. For example, Marfan syndrome is a rare connective tissue disorder caused by variants in the FBN1 gene. The UMD-FBN1 database17 contains 3077 variants in FBN1 from 280 references (last updated 28/08/14). The most common variant is in 30/3006 records (1.00%; 95CI 0.53–1.46%), which likely overestimates its contribution to disease if related individuals are not systematically excluded. Taking the upper bound of this frequency as our maximum allelic contribution, we derive a maximum tolerated allele count of 2 (Table 2). None of the five most common variants in the database are present in ExAC.

TABLE 2.

Maximum credible population frequencies and maximum tolerated ExAC allele counts for variants causative of exemplar inherited cardiac conditions, assuming a penetrance of 0.5 throughout.

| Disease | Maximum allelic contribution | Prevalence | Penetrance* | Maximum population frequency | Maximum tolerated ExAC allele count |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marfan | 0.015 | 1/3000 | 0.5 | 5.0x10-6 | 2 |

| Noonan | 0.10 | 1/1000 | 0.5 | 1.0x10-4 | 18 |

| CPVT | 0.10 | 1/10,000 | 0.5 | 1.0x10-5 | 3 |

| Classic Ehlers-Danlos | 0.40 | 1/20,000 | 0.5 | 2.0x10-5 | 5 |

Where no mutation database exists, we can use what is known about similar disorders to estimate the maximum allelic contribution. For the better-characterised cardiac conditions in Table 1, the maximum proportion of cases attributable to any one variant is 6.7% (95CI 4.1–9.2%; PKP2:c.2146–1G>C found in 24/361 ARVC cases15). We therefore propose the upper bound of this confidence interval (rounded up to 0.1) as a reasonable estimate of the maximum allelic contribution for other genetically heterogeneous cardiac conditions, unless there is disease-specific evidence to alter it. For Noonan syndrome and Catecholaminergic Polymorphic Ventricular Tachycardia (CPVT - an inherited cardiac arrhythmia syndrome) with prevalences of 1 in 100018 and 1 in 10,00019 respectively, this translates to maximum population frequencies of 5x10−5 and 5x10−6 and maximum tolerated ExAC allele counts of 10 and 2 (Table 2).

Finally, if the allelic heterogeneity of a disorder is not well characterised, it is conservative to assume minimal heterogeneity, so that the contribution of each gene is modeled as attributable to one allele, and the maximum allelic contribution is substituted by the maximum genetic contribution (i.e the maximum proportion of the disease attributable to single gene). For classic Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, up to 40% of the disease is caused by variation in the COL5A1 gene20. Taking 0.4 as our maximum allelic contribution, and a population prevalence of 1/20,00020 we derive a maximum tolerated ExAC AC of 5 (Table 2).

Here we have illustrated frequencies analysed at the level of the disease. In some cases this may be further refined by calculating distinct thresholds for individual genes, or even variants. For example, if there is one common founder mutation but no other variants that are recurrent across cases, then it would make sense to have the founder mutation as an exception to the calculated threshold.

Application to recessive diseases

So far we have considered diseases with a dominant inheritance model. Our framework is readily modified for application in recessive disease, and to illustrate this we consider the example of Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD), which has a prevalence of up to 1 in 10,000 individuals in the general population21.

Intuitively, if one penetrant recessive variant were to be responsible for all PCD cases, it could have a maximum population frequency of . We can refine our evaluation of PCD by estimating the maximum genetic and allelic contribution (see Methods). Across previously published cohorts of PCD cases22–24, DNAI1 IVS1+2_3insT was the most common variant with a total of 17/358 alleles (4.7% 95CI 2.5–7.0%). Given that ~9% of all patients with PCD have disease-causing variants in DNAI1 and the IVS1+2_3insT variant is estimated to account for ~57% of variant alleles in DNAI122, we can take these values as estimates of the maximum genetic and allelic contribution for PCD, yielding a maximum expected population AF of This translates to a maximum tolerated ExAC AC of 322. DNAI1 IVS1+2_3insT is itself present at 56/121108 ExAC alleles (45/66636 non-Finnish European alleles). A single variant reported to cause PCD in ClinVar occurs in ExAC with AC > 332 (NME8 NM_016616.4:c.271–27C>T; AC=2306/120984): our model therefore indicates that this variant frequency is too common to be disease-causing, and consistent with this we note that it meets none of the current ACMG criteria for assertions of pathogenicity, and would reclassify it as VUS (see Supplementary Methods).

Pre-computing threshold values for the ExAC populations

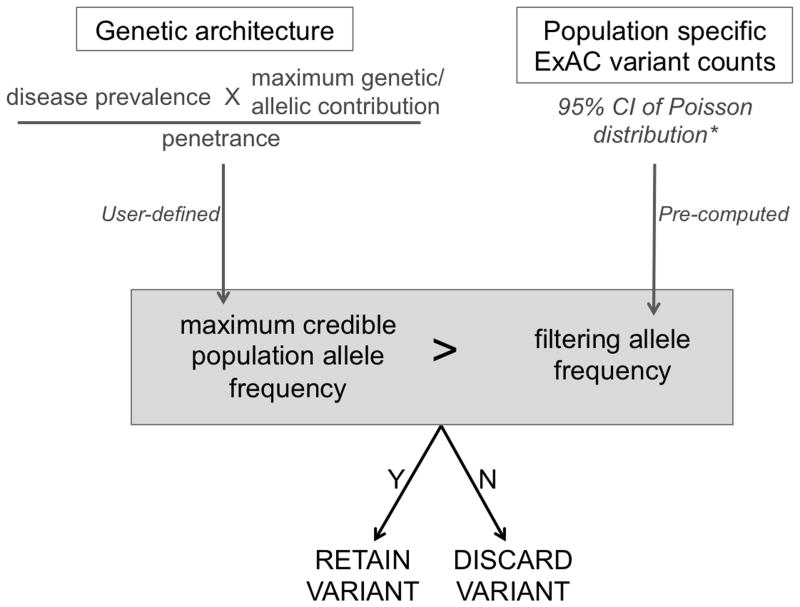

For each ExAC variant, we defined a “filtering AF” that represents the threshold disease-specific “maximum credible AF” at or below which the disease could not plausibly be caused by that variant. A variant with a filtering AF ≥ the maximum credible AF for the disease under consideration should be filtered, while a variant with a filtering AF below the maximum credible remains a candidate. This filtering AF is not disease specific: it can be applied to any disease of interest by comparing with a user-defined disease-specific maximum credible AF (Figure 2). This value has been pre-computed for all variants in ExAC (see Methods and Supplementary Methods), and is available via the ExAC VCF and browser (http://exac.broadinstitute.org).

Figure 2.

A flow diagram of our approach, applied to a dominant condition, and using ExAC as our reference sample. First, a disease-level maximum credible population allele frequency is calculated, based on disease prevalence, heterogeneity and penetrance. To evaluate a specific variant, we determine whether the observed variant allele count is compatible with disease by comparing this maximum credible population AF against the (pre-calculated) filtering allele frequency for the variant. *while filtering allele frequency has been pre-computed for ExAC variants, the same framework can be readily applied using another reference sample.

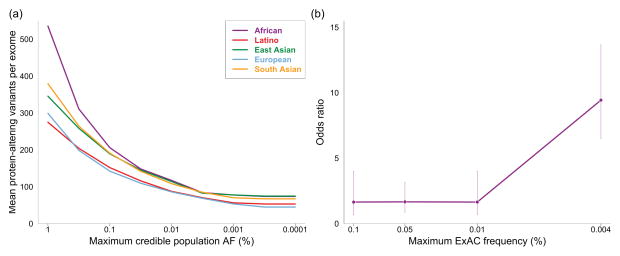

To assess the efficiency of our approach, we calculated the filtering AF on 60,206 exomes from ExAC and applied these filters to a simulated dominant Mendelian variant discovery analysis on the remaining 500 exomes (see Methods). Filtering at AFs lower than 0.1% substantially reduces the number of predicted protein-altering variants in consideration, with the mean number of variants per exome falling from 176 to 63 at cutoffs of 0.1% and 0.0001% respectively (Figure 3a). Additionally, we compared the prevalence of variants in HCM genes in cases and controls across the AF spectrum, and computed disease odds ratios for different frequency bins. The odds ratio for disease-association increases markedly at very low AFs (Figure 3b) demonstrating that increasing the stringency of a frequency filter improves the information content of a genetic result.

Figure 3.

The clinical utility of stringent allele frequency thresholds. (a) The number of predicted protein-altering variants (definition in Methods) per exome as a function of the allele frequency filter applied. A one-tailed 95% confidence interval is used, meaning that variants were removed from consideration if their AC would fall within the top 5% of the Poisson probability distribution for the user’s maximum credible AF (x axis). (b) The odds ratio for HCM disease-association against allele frequency. The prevalence of variants in sarcomeric HCM-associated genes (MYH7, MYBPC3, TNNT2, TNNI3, MYL2, MYL3, TPM1 and ACTC1, analysed collectively) in 322 HCM cases and 852 healthy controls were compared for a range of allele frequency bins, and an odds ratio computed (see Methods). Data for each bin is plotted at the upper allele frequency cutoff. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. The probability that a variant is pathogenic is much greater at very low allele frequencies.

DISCUSSION

We have outlined a statistically robust framework for assessing whether a variant is ‘too common’ to be causative for a Mendelian disorder of interest. To our knowledge, there is currently no equivalent guidance on the use of variant frequency information, resulting in inconsistent thresholds across both clinical and research settings. Furthermore, though disease-specific thresholds are recommended8, in practice the same thresholds may be used across all diseases, even where they have widely differing genetic architectures and prevalences. We have shown the importance of applying stringent AF thresholds, in that many more variants can be removed from consideration, and the remaining variants have a much higher likelihood of being relevant. We also show, using HCM as an example, how lowering this threshold does not remove true dominant pathogenic variants.

To assist others in applying our framework, we have precomputed a ‘filtering AF’ for all variants across the ExAC dataset. This is defined such that if the filtering AF of a variant is at or above the user-defined “maximum credible population AF” for the disease in question, then that variant is not a credible candidate (in other words, for any population AF below the threshold value, the probability of the observed allele count in the ExAC sample is <0.05). Once a user has determined their “maximum credible population AF”, they may remove from consideration ExAC variants for which the filtering AF is greater than or equal to than the chosen value.

Our method is designed to be complementary to and used along side other gene and variant level methods to filter and prioritise candiate variants (e.g. gene level constraint25, amino acid conservation26,27 and missense prediction algorithms28,29) along with segregation and functional data.

We recognise several limitations of our approach. First, we are limited by our understanding of the prevalence and genetic architecture of the disease in question: this characterisation will vary for different diseases and in different populations, though we illustrate approaches for estimation and extrapolation of parameters. In particular, we must be wary of extrapolating to or from less-well characterised populations that could harbour population-specific founder mutations. While incomplete knowledge of the genetic architecture of a disease of interest will limit this or any approach to evaluate a specific variant that has been observed at low frequency in a reference population, our framework and accompanying web tool do at least transparently define the range of disease architectures that are compatible with the observed data. For example, many neurological disorders have Mendelian forms as well as idiopathic forms with genetic risk factors of modest effect sizes, high allelic and genetic heterogeneity, and/or dramatic variability in the penetrance of different variants9,30–32. Reference population allele frequency information alone can never definitively show that a variant possesses no association to disease, but it can still provide sensible constraints. The calculations described here can be used to show that a variant could could only be causal if the prevalence of the disease is higher than published estimates, or its penetrance is below a specified value33.

Secondly, it is often difficult to obtain accurate penetrance information for reported variants, and it is also difficult to know what degree of penetrance to expect or assume for newly discovered pathogenic variants. Although we would argue that variants with low penetrance have questionable diagnostic utility, our calculator app allows a user to define a range of compatible penetrance for a given AF (see Supplementary Methods), and implements methods to estimate variant penetrance from prevalence data in case and control cohorts as previously described9.

Thirdly, while we believe that ExAC is depleted of severe childhood inherited conditions, and not enriched for cardiomyopathies, it could be enriched relative to the general population for some conditions, including Mendelian forms of common diseases such as diabetes or coronary disease that have been studied in contributing cohorts. Where this is possible, the maximum credible population AF should be derived based on the estimated disease prevalence in the ExAC cohort, rather than the population prevalence.

Finally, although the resulting AF thresholds are more stringent than those previously used, they are likely to still be very lenient for many applications. For instance, we base our calculation on the most prevalent known pathogenic variant from a disease cohort. For HCM, for which more than 6,000 people have been sequenced, it is unlikely that any single newly identified variant, not previously catalogued in this large cohort, will explain a similarly large proportion of the disease as the most common causal variant, at least in well-studied populations. Future work may therefore involve modeling the frequency distribution of all known variants for a disorder, to further refine these thresholds.

The power of our approach is limited by currently available datasets. Increases in both the ancestral diversity and size of reference datasets will bring additional power to our method over time. We have avoided filtering on variants observed only once, because a single observation provides little information about true AF (see Supplementary Methods). A ten-fold increase in sample size, resulting from projects such as the US Precision Medicine Initiative, will separate vanishingly rare variants from those whose frequency really is ~1 in 100,000. Increased phenotypic information linked to reference datasets will also reduce limitations due to uncertain disease status, and improve prevalence estimates, adding further power to our approach.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust (107469/Z/15/Z), the Medical Research Council (UK), the NIHR Biomedical Research Unit in Cardiovascular Disease at Royal Brompton & Harefield NHS Foundation Trust and Imperial College London, the Fondation Leducq (11 CVD-01), a Health Innovation Challenge Fund award from the Wellcome Trust and Department of Health, UK (HICF-R6-373), and by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the NIH (awards U54DK105566 and R01GM104371). EVM is supported by the National Institutes of Health under a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (NRSA) NIH Individual Predoctoral Fellowship (F31) (award AI122592-01A1). AHO-L is supported by National Institutes of Health under Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award 4T32GM007748.

This publication includes independent research commissioned by the Health Innovation Challenge Fund (HICF), a parallel funding partnership between the Department of Health and Wellcome Trust. The views expressed in this work are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Health or Wellcome Trust.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST NOTIFICATION

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

DATA AND CODE AVAILABILITY

All data and code required to reproduce the analysis, figures and manuscript (compiled in R) are available at https://github.com/ImperialCardioGenetics/frequencyFilter. Curated variant interpretations are deposited in ClinVar under the submission name “HCM_ExAC_frequency_review_2016”. ExAC annotations are available at https://exac.broadinstitute.org. Our AF calculator app is located at http://cardiodb.org/alleleFrequencyApp, with source code available at http://github.com/jamesware/alleleFrequencyApp.

Supplementary Methods: - Curation of a high frequency PCD variant - Dealing with penetrance - Treatment of singletons and other populations - Description of the filtering AF

References

- 1.Chong JX, Buckingham KJ, Jhangiani SN, et al. The genetic basis of mendelian phenotypes: Discoveries, challenges, and opportunities. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2015;97(2):199–215. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV, et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature. 2016;536(7616):285–291. doi: 10.1038/nature19057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the american college of medical genetics and genomics and the association for molecular pathology. Genetics in Medicine. 2015;17(5):405–423. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacArthur DG, Manolio TA, Dimmock DP, et al. Guidelines for investigating causality of sequence variants in human disease. Nature. 2014;508(7497):469–476. doi: 10.1038/nature13127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bamshad MJ, Ng SB, Bigham AW, et al. Exome sequencing as a tool for mendelian disease gene discovery. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2011;12(11):745–755. doi: 10.1038/nrg3031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andres AM, Hubisz MJ, Indap A, et al. Targets of balancing selection in the human genome. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2009;26(12):2755–2764. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zuk O, Schaffner SF, Samocha K, et al. Searching for missing heritability: Designing rare variant association studies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2014;111(4):E455–E464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322563111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amendola LM, Jarvik GP, Leo MC, et al. Performance of ACMG-AMP variant-interpretation guidelines among nine laboratories in the clinical sequencing exploratory research consortium. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2016;98(6):1067–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minikel EV, Vallabh SM, Lek M, et al. Quantifying prion disease penetrance using large population control cohorts. Science Translational Medicine. 2016;8(322):322ra9–322ra9. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad5169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wright CF, Fitzgerald TW, Jones WD, et al. Genetic diagnosis of developmental disorders in the DDD study: A scalable analysis of genome-wide research data. The Lancet. 2015;385(9975):1305–1314. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61705-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor JC, Martin HC, Lise S, et al. Factors influencing success of clinical genome sequencing across a broad spectrum of disorders. Nature Genetics. 2015;47(7):717–726. doi: 10.1038/ng.3304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saltzman AJ, Mancini-DiNardo D, Li C, et al. Short communication: The cardiac myosin binding protein c arg502Trp mutation: A common cause of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation Research. 2010;106(9):1549–1552. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.109.216291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pua CJ, Bhalshankar J, Miao K, et al. Development of a comprehensive sequencing assay for inherited cardiac condition genes. Journal of Cardiovascular Translational Research. 2016;9(1):3–11. doi: 10.1007/s12265-016-9673-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alfares AA, Kelly MA, McDermott G, et al. Results of clinical genetic testing of 2,912 probands with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Expanded panels offer limited additional sensitivity. Genetics in Medicine. 2015;17(11):880–888. doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walsh R, Thomson KL, Ware JS, et al. Reassessment of mendelian gene pathogenicity using 7,855 cardiomyopathy cases and 60,706 reference samples. Genetics in Medicine. 2016 Aug; doi: 10.1038/gim.2016.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Landrum MJ, Lee JM, Riley GR, et al. ClinVar: Public archive of relationships among sequence variation and human phenotype. Nucleic Acids Research. 2013;42(D1):D980–D985. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collod-B’eroud G, Bourdelles SL, Ades L, et al. Update of the UMD-FBN1mutation database and creation of anFBN1polymorphism database. Human Mutation. 2003;22(3):199–208. doi: 10.1002/humu.10249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roberts AE, Allanson JE, Tartaglia M, Gelb BD. Noonan syndrome. The Lancet. 2013;381(9863):333–342. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)61023-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Napolitano C, Bloise R, Memmi M, Priori SG. Clinical utility gene card for: Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT) European Journal of Human Genetics. 2013;22(1) doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2013.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malfait F, Wenstrup RJ, Paepe AD. Clinical and genetic aspects of ehlers-danlos syndrome, classic type. Genetics in Medicine. 2010;12(10):597–605. doi: 10.1097/gim.0b013e3181eed412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lucas JS, Burgess A, Mitchison HM, Moya E, Williamson M, CH Diagnosis and management of primary ciliary dyskinesia. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2014;99(9):850–856. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2013-304831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zariwala MA, Leigh MW, Ceppa F, et al. Mutations of DNAI1 in primary ciliary dyskinesia. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2006;174(8):858–866. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200603-370oc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hornef N, Olbrich H, Horvath J, et al. DNAH5 mutations are a common cause of primary ciliary dyskinesia with outer dynein arm defects. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2006;174(2):120–126. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200601-084oc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Panizzi JR, Becker-Heck A, Castleman VH, et al. CCDC103 mutations cause primary ciliary dyskinesia by disrupting assembly of ciliary dynein arms. Nature Genetics. 2012;44(6):714–719. doi: 10.1038/ng.2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Samocha KE, Robinson EB, Sanders SJ, et al. A framework for the interpretation of de novo mutation in human disease. Nature Genetics. 2014;46(9):944–950. doi: 10.1038/ng.3050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siepel A. Evolutionarily conserved elements in vertebrate, insect, worm, and yeast genomes. Genome Research. 2005;15(8):1034–1050. doi: 10.1101/gr.3715005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cooper GM. Distribution and intensity of constraint in mammalian genomic sequence. Genome Research. 2005;15(7):901–913. doi: 10.1101/gr.3577405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nature Methods. 2010;7(4):248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sim N-L, Kumar P, Hu J, Henikoff S, Schneider G, Ng PC. SIFT web server: Predicting effects of amino acid substitutions on proteins. Nucleic Acids Research. 2012;40(W1):W452–W457. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guerreiro R, Br’as J, Hardy J. SnapShot: Genetics of alzheimer’s disease. Cell. 2013;155(4):968–968e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guerreiro R, Br’as J, Hardy J. SnapShot: Genetics of ALS and FTD. Cell. 2015;160(4):798–798e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lill CM, Roehr JT, McQueen MB, et al. Comprehensive research synopsis and systematic meta-analyses in parkinsons disease genetics: The PDGene database. In: Myers AJ, editor. PLoS Genetics. 3. Vol. 8. 2012. p. e1002548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Minikel EV, MacArthur DG. Publicly available data provide evidence against NR1H3 r415Q causing multiple sclerosis. Neuron. 2016;92(2):336–338. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.09.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hershberger RE, Hedges DJ, Morales A. Dilated cardiomyopathy: The complexity of a diverse genetic architecture. Nature Reviews Cardiology. 2013;10(9):531–547. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2013.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peters S. Advances in the diagnostic management of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasiacardiomyopathy. International Journal of Cardiology. 2006;113(1):4–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kapplinger JD, Tester DJ, Salisbury BA, et al. Spectrum and prevalence of mutations from the first 2,500 consecutive unrelated patients referred for the FAMILION long QT syndrome genetic test. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6(9):1297–1303. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perrin MJ, Gollob MH. Genetics of cardiac electrical disease. Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 2013;29(1):89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2012.07.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kapplinger JD, Tester DJ, Alders M, et al. An international compendium of mutations in the SCN5A-encoded cardiac sodium channel in patients referred for brugada syndrome genetic testing. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7(1):33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.09.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vohra J, Rajagopalan S. Update on the diagnosis and management of brugada syndrome. Heart, Lung and Circulation. 2015;24(12):1141–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2015.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Judge DP, Dietz HC. Marfans syndrome. The Lancet. 2005;366(9501):1965–1976. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)67789-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.