Abstract

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing relies on a guide RNA (gRNA) molecule to generate sequence-specific DNA cleavage, which is a prerequisite for gene editing. Here we establish a method that enables production of gRNAs from any promoters, in any organisms, and in vitro (Gao and Zhao, 2014). This method also makes it feasible to conduct tissue/cell specific gene editing.

Keywords: Ribozyme, CRISPR, RNA polymerase II promoter, Genome editing, RNA transcription

Background

Almost all of the reported cases of CRISPR-mediated gene editing used promoters of small nuclear RNAs such as the U6 and U3 snRNA promoters to drive the production of gRNAs in vivo (Cong et al., 2013; Mali et al., 2013). However, the U6 and U3 promoters have several major limitations: 1) They are constitutively active and not tunable; 2) They lack cell/tissue specificities; 3) They have not been well defined in many organisms; 4) U6 requires a G and U3 requires an A for transcription initiation, thus limiting target selections; 5) They are not suitable for in vitro transcriptions because of the lack of commercial RNA polymerase III. Unfortunately, RNA polymerase II promoters, which constitute the majority of the characterized promoters, cannot be directly used for gRNA production in vivo because of the following reasons: 1) The primary transcripts of RNA polymerase II promoters undergo extensive processing such as 5′-end capping, 3′-end polyadenylation, and splicing out of the introns. Some of the modifications may render the designed gRNA non-functional. 2) The mature RNA molecules are transported into cytosol; thus they are physically separated from the intended targets that are located in the nucleus. That is why production of gRNA in vivo using U6 and U3 snRNA promoters has been the dominant method (Gao and Zhao, 2014; Yoshioka et al., 2015). In this protocol, we use a ribozyme-based strategy to overcome the aforementioned limitations of RNA polymerase III promoters, enabling gRNA production from any promoters and in any organisms. We design an artificial gene named RGR (Ribozyme-gRNA-Ribozyme) that, once transcribed, generates an RNA molecule with ribozyme sequences flanking both ends of the designed gRNA (Gao and Zhao, 2014). We show that the primary transcripts of RGR undergo self-catalyzed cleavage to precisely release the desired gRNA, which can efficiently guide sequence-specific cleavage of DNA targets in vitro and in vivo (Gao and Zhao, 2014). RGR can be transcribed from any promoters and thus allows for cell-and tissue-specific genome editing if appropriate promoters are chosen.

Materials and Reagents

E. coli DH5a and Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101

pRS316-RGR-GFP plasmid (Addgene, catalog number: plasmid 51056)

pHDE-35S-Cas9-mCherry-UBQ plasmid

Primers (Table S1)

-

Gibson assembly reagents

You can either purchase commercial kits from (New England Biolabs, catalog number: E5510S), or prepare your own with the following individual reagents:

5x isothermal (ISO) reaction buffer (25% PEG-8000; 500 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 50 mM MgCl2; 50 mM DTT; 1 mM each of the 4 dNTPs; and 5 mM NAD)

T5 exonuclease (Epicentre, catalog number: T5E4111K)

Phusion DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs, catalog number: M0530L)

Taq DNA ligase (New England Biolabs, catalog number: M0208L)

Phusion High-Fidelity PCR Kit (New England Biolabs, catalog number: E0553L)

LB medium

Appropriate antibiotics

QIAGEN Plasmid Mini Kit

MfeI (New England Biolabs, catalog number: R0589S)

10x CutSmart® buffer

-

T7, SP6 or T3 RNA polymerase with transcription buffer

For SP6/T7 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Invitrogen™, catalog number: AM1320)

For T3 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Invitrogen™, catalog number: AM1316)

5x transcription buffer

1 M DTT (Thermo Fisher Scientific, catalog number: P2325)

20 U/μl RNase inhibitor (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Applied Biosystems™, catalog number: N8080119)

10 mM NTP mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Invitrogen™, catalog number: 18109017)

rNTPs

Inorganic pyrophosphatase

EDTA

12% denaturing urea polyacrylamide gels

Ethidium bromide

Equipment

37 °C water bath (Temperature-controlled water bath) (Bio-Rad Laboratories, catalog number: 1660524)

Thermal cycler (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Applied Biosystems™, model: Applied Biosystems® 2720, catalog number: 4359659)

DNA electrophoresis apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories, model: PowerPac™ Basic Power Supply, catalog number: 1645050EDU)

Microcentrifuges (Eppendorf, model: 5424)

UV transilluminator (Bio-Rad Laboratories, model: UViewTM Mini Transilluminator, catalog number: 1660531)

Procedure

A. Design, assemble, and clone an RGR (ribozyme-gRNA-ribozyme) unit

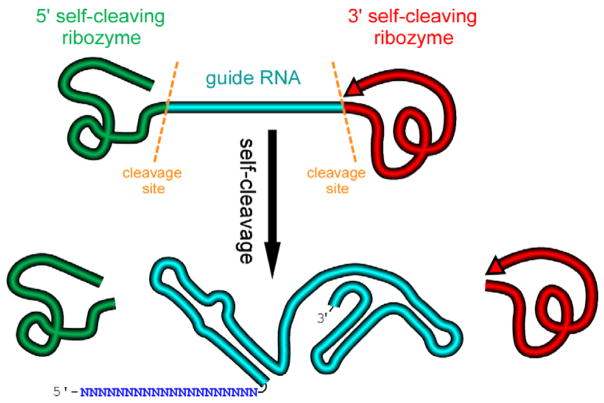

We design an artificial gene named RGR, whose primary transcripts would be flanked by ribozymes at both ends (Figure 1) (Gao and Zhao, 2014).

Figure 1. A schematic presentation of a ribozyme-flanked gRNA (RGR, ribozyme-gRNA-ribozyme) molecule.

Once transcribed, the corresponding RGR DNA will produce an RNA molecule with a ribozyme at both the 5′- and 3′-end. The primary transcripts will undergo self-cleavage to release the mature gRNA. The RGR design allows the production of a functional gRNA molecule from any promoter, enabling production of gRNA molecules in vitro, in vivo, and in tissue/cell specific manner.

-

Select a target sequence for editing the gene of interest

The target should be 23 bp long and should contain the NGG Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) site at the 3′-end. However, the NGG PAM site should not be included in the gRNA sequence itself. N refers to any nucleotide in the target N1N2N3N4N5N6N7N8N9N10N11N12N13N14N15N16N17N18N19N20NGG. Multiple web-based resources are publically available for selecting appropriate gRNA targets (http://cbi.hzau.edu.cn/crispr/; http://www.rgenome.net/cas-offinder/; http://www.genome.arizona.edu/crispr/CRISPRsearch.html).

-

Design an Ribozyme-gRNA-Ribozyme (RGR) unit

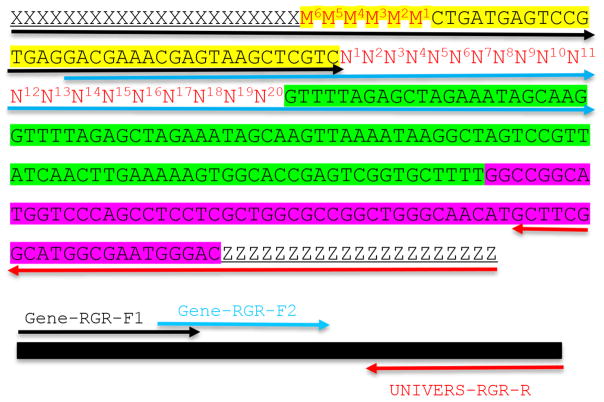

We place a Hammerhead ribozyme at the 5′-end of the gRNA and a HDV ribozyme at the 3′-end of the gRNA (Figure 2). The complete sequences of the ribozymes were described in the plasmid pRS316-RGR-GFP (Gao and Zhao, 2014). Both the plasmid and the complete sequence of pRS316-RGR-GFP are available at Addgene.

The RGR unit can then be placed under the control of a promoter for the production of the designed gRNA molecules. Any promoters including both RNA polymerase II and RNA polymerase III promoters can be used. For in vitro production of gRNAs, the RGR unit can be driven by a SP6 or T7 or T3 promoter, which can be transcribed using commercially available RNA polymerases (Gao and Zhao, 2014).

Linearize the vector of your choice with a restriction enzyme and determine an 18 to 24 bp overlapping region (termed adaptor sequence) based on the Gibson assembly principle (Gibson et al., 2009). Gibson assembly method seamlessly assembles overlapping DNA molecules into one molecule by the concerted action of a 5′ exonuclease, a PHUSION DNA polymerase and a heat-stable Taq DNA ligase (Gibson et al., 2009). Additional information about Gibson assembly can be found at Addgene (http://www.addgene.org/protocols/gibson-assembly/). Assembly kits are commercially available at New England Biolabs (https://www.neb.com/products/e5510-gibson-assembly-cloning-kit).

-

If the adaptor sequences are XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX (upstream adaptor) and YYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYY (downstream adaptor), design two forward primers and one reverse primer as shown below. Adaptor sequences including X and Y provide the necessary overlapping sequences with your linearized vector so that the RGR unit can be assembled into the vector through Gibson assembly principle. The length of adaptor sequences varies depending on the actual sequences, but usually 17 bp to 24 bp is sufficient as long as the Tm value is above 50 °C.

-

Forward primer 1: GENE-RGR-F1

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXM6M5M4M3M2M1CTGATGAGTCCGTGAGGACGAAACG AGTAAGCTCGTC

The sequence X (bold) refers to the upstream adaptor sequence, which is complementary to the vector sequence. M sequence is reverse complementary to the first 6 bp of the target sequence. The italicized sequence is part of the Hammerhead ribozyme.

-

Forward primer 2: GENE-RGR-F2

GACGAAACGAGTAAGCTCGTCN1N2N3N4N5N6N7N8N9N10N11N12N13N14N15N16N17N18N19N20GTTTTAGAGCTAGAAATAGCAAG. N1N2N3N4N5N6 and M6M5M4M3M2M1 are reverse complementary to ensure the correct secondary structure of the Hammerhead ribozyme. We designed the two overlapping PCR primers to avoid the synthesis of expensive long primers. The target sequence is N1N2N3N4N5N6N7N8N9N10N11N12N13N14N15N16N17N18N19N20NGG.

Note: The PAM site NGG is not included in the primer. The italicized sequence is part of the core gRNA sequence.

Design a universal RGR-Reverse primer for the vector of your choice: UNIVERS-RGR-R: ZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZGTCCCATTCGCCATGCCGAAGC. The UNIVERS-RGR-R primer should be reverse complementary to GCTTCGGCATGGCGAATGGGACYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYY, where YYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYY is the downstream adaptor sequence (Y and Z are reverse complementary). The italicized sequence is complementary to the 3′ end of the HDV ribozyme.

-

-

Assemble the Ribozyme-gRNA-Ribozyme (RGR) unit

An RGR unit for targeting a new gene is assembled through two rounds of overlapping PCR reactions (Figure 2). There is a 21-bp overlap between the two forward primers (Figure 2).

First PCR (PCR1): Use primer pair GENE-RGR-F2 + UNIVERS-RGR-R. Template: any existing RGR construct (e.g., pRS316-RGR-GFP, available from Addgene. The expected PCR product is 233 bp).

-

The second-round PCR (PCR2): Use primer pair GENE-RGR-F1 + UNIVERS-RGR-R. Gel-purified PCR product from PCR1 is used as the template. The expected PCR2 product is 277 bp, which is the complete RGR unit (Figure 2).

A routine PCR reaction is set up according to the manufacturer’s recommendation (https://www.neb.com/protocols/1/01/01/pcr-protocol-m0530). Briefly, the PCR components are mixed as described in Table 1.

-

Ligate the final RGR product into a desired vector - clone the RGR (ribozyme-gRNA-ribozyme) unit

The complete RGR unit assembled through two rounds of PCR is cloned into the final CRISPR vector using Gibson assembly protocol (Gibson et al., 2009). Note that the PCR primers GENE-RGR-F1 and UNIVERS-RGR-R contain sequences that match part of the sequences in the vector to facilitate the in vitro assembly of the RGR unit into the vector (Figure 2).

Incubate the DNA assembly mixture (Table 3) for 1 h at 50 °C. DNA assembly was conducted by following the manufacturer’s recommended protocol (Table 3). (https://www.neb.com/products/e2611-gibson-assembly-master-mix#tabselect2)

-

Then transform 3 μl ligated product to E. coli DH5α competent cells.

The ligated plasmid could be transformed into E. coli competent cells following routine cloning procedure (Sambrook and Russell, 2001).

Transform E. coli DH5α competent cells (homemade or commercially available products) using 3 μl of ligation product.

Inoculate 2 to 4 colonies in LB medium with appropriate antibiotics.

Purify plasmids from the transformed DH5α cells using QIAGEN Plasmid Mini Kit.

Verify the positive clones by Sanger sequencing before introducing the final plasmid into your cell/organism of choice (Yoshioka et al., 2015).

Figure 2. Molecular design of an RGR unit and the assembly of a complete RGR unit by PCR.

The top panel shows the complete sequence of an RGR unit that produces a gRNA that targets (N)20NGG sequence. The underlined sequences are adaptor sequences from the vector and are used for cloning the RGR unit into the final CRISPR vector. Note that the adaptor sequences vary accordingly if different vectors are chosen. N1 to N20 (in red) are the target sequence prior to the NGG PAM site. It is essential that the M6M5M4M3M2M1 and N1N2N3N4N5N6 are reverse complementary so that the ribozyme can undergoes self-cleavage as designed. Sequence highlighted in green is the core gRNA sequence. Sequence highlighted in yellow is the Hammerhead ribozyme. The HDV ribozyme is highlighted in purple. The primers are marked by different colors: black (Gene-RGR-F1), light blue (Gene-RGR-F2), and Red (UNIVERS-RGR-R). The Universal primer depends on the vector sequences and needs to be changed if different vectors are used. The complete RGR unit can be easily assembled by two over-lapping PCR reactions.

Table 1.

PCR setup for amplification of the RGR unit

| DNA template | 20 ng |

| dNTPs (2 mM) | 10 μl |

| Forward primer (20 μM) | 2.5 μl |

| Reverse primer (20 μM) | 2.5 μl |

| 5x PCR buffer | 20 μl |

| Phusion DNA polymerase (NEB) | 1 μl |

| Add nuclease free H2O to 100 μl |

Table 3.

In vitro DNA assembly

| Final PCR product and the vector | 0.03–0.2 pmols, X μl |

| Recommended DNA ratio | Vector:Insert = 1:2 |

| NEB HiFi DNA assembly master mix (Gibson Assembly® Cloning Kit) | 10 μl |

| Water | 10-X μl |

| Total Volume | 20 μl |

B. An example of constructing an RGR unit for CRISPR-mediated gene editing

-

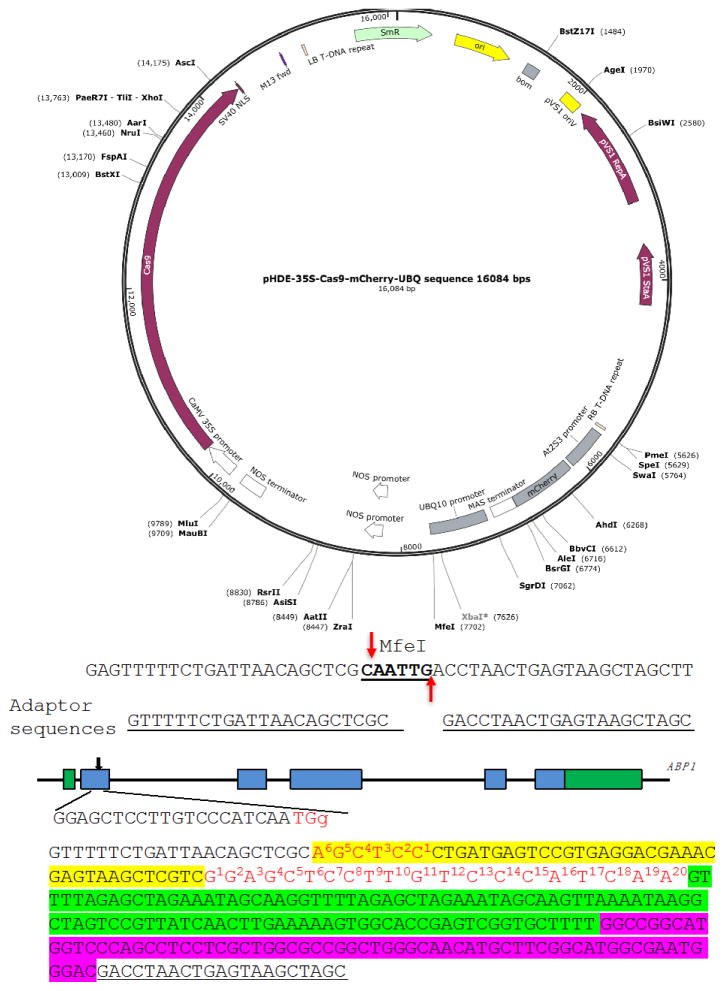

Select a target gene and a vector

We show the construction of an RGR unit to target the Arabidopsis gene Auxin Binding Protein 1 (ABP1) (Figure 3) as an example (Gao et al., 2015). We use pHDE-35S-Cas9-mCherry-UBQ plasmid as our CRISPR vector (Gao et al., 2016), which has been used for editing genes in Arabidopsis (the plasmid can be obtained through Addgene).

-

Linearize the plasmid

We digest pHDE-35S-Cas9-mCherry-UBQ plasmid with MfeI (Figure 3). The MfeI-linearized plasmid is used for assembling the RGR unit into the vector through Gibson assembly. The complete plasmid can express the ABP1-RGR unit from the Arabidopsis UBQ10 promoter in plants (Figure 3).

Mix the components shown in the Table 4 and digest the vector overnight at 37 °C. Then heat inactivation the enzyme at 80 °C for 15 min. The linearized plasmid was16,084 bp.

-

Design the PCR primers

The upstream adaptor sequence is GTTTTTCTGATTAACAGCTCGC. The downstream adaptor we used is GACCTAACTGAGTAAGCTAGC (Figure 3).

-

Forward primer 1: ABP1-RGR-F1:

GTTTTTCTGATTAACAGCTCGCAGCTCCCTGATGAGTCCGTGAGGACGAAACGAGTAAGCTCGTC. The 6 bp sequence in bold is reverse complementary to the first 6 bp of the gRNA target. The underlined sequence is part of the Hammerhead ribozyme.

-

Forward primer 2: ABP1-RGR-F2:

GACGAAACGAGTAAGCTCGTCGGAGCTCCTTGTCCCATCAAGTTTTAGAGCTAGAAATAGCAAG. The underlined sequence is part of the Hammerhead ribozyme. Sequence in bold is the gRNA target sequence, and the italicized sequence is part of the core gRNA sequence.

Note: The bold sequence in ABP1-RGR-F1 is reverse complementary to the first 6 bp of the bold sequence in ABP1-RGR-F2. ABP1-RGR-F1 and ABP1-RGR-F2 share the following overlapping sequences: GACGAAACGAGTAAGCTCGTC, which allows us to conduct two overlapping PCR reactions.

-

-

For cloning the ABP1-RGR unit into the MfeI site in 35S-Cas9-mCherry-UBQ plasmid using Gibson assembly, the UNIVERS-RGR-R primer is:

GCTAGCTTACTCAGTTAGGTCGTCCCATTCGCCATGCCGAAGC

Note: The bold sequence is complementary to the downstream adaptor sequence. The italicized sequence matches the 3′ end of the HDV ribozyme.

The complete RGR unit for producing a gRNA targeting the ABP1 gene is shown in Figure 3. The RGR unit has led to successful isolation of several null alleles of abp1 in Arabidopsis (Gao et al., 2015 and 2016).

Figure 3. A Molecular design of an RGR unit for targeting the ABP1 gene in Arabidopsis.

The RGR unit is cloned into the pHDE-35S-Cas9-mCherry-UBQ plasmid at the MfeI site using Gibson assembly. The adaptor sequences are underlined. Note that the downstream adaptor sequence has to be converted to reverse complementary sequence when design the Universal primer. The target sequence is in red. The Hammerhead ribozyme and the HDV ribozyme are highlighted in yellow and purple, respectively.

Table 4.

Linearize the vector by restriction digestion

| pHDE-35S-Cas9-mCherry-UBQ | 200 ng |

| MfeI (10,000 U/ml) | 1 μl |

| 10x CutSmart® buffer | 2 μl |

| Add sterile distilled H2O | to 20 μl |

C. Guide RNA production by in vitro transcription

Once an RGR unit is assembled and cloned into the final vector as described above, gRNAs can be easily produced by in vitro transcription using T7, SP6, or T3 RNA polymerases, which are commercially available.

-

Prepare a DNA template for in vitro transcription

The templates for in vitro transcription are ampli ed by PCR from the assembled RGR constructs using two universal primers (any RGR units cloned into the same vector can be amplified using the same pair of primers). For example, RGR units cloned into the MfeI site in pHDE-35S-Cas9-mCherry-UBQ can be amplified using the following pair of primers: SP6-P1: GTCACTATTTAGGTGACACTATAGAAGCGGTTTTTCTGATTAACAGCTCGC and Univers-P2: GCTAGCTTACTCAGTTAGGTC.

The Underlined sequence is the SP6 promoter and the bolded G in primer SP6-P1 is the transcription initiation site for SP6 RNA polymerase. If T7 or T3 RNA polymerases are used, the underlined 5′-end of the primer SP6-P1 needs to be changed to GTCACTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGA and GTCACAATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGGAGA respectively.

-

In vitro transcription

-

Add the following reagents at room temperature in the order listed in Table 5:

Note: For higher yield, add 1 U inorganic pyrophosphatase into the reaction and incubate overnight.

Incubate the mixture for 2 to 8 h at 37 °C (T7, T3) or 42 °C (SP6).

-

Add 1 μl 0.5 M EDTA to terminate the reaction.

Note: There is no need to further purify the RNA transcripts for in vitro CRISPR cleavage assays (for in vitro cleavage assay example, follow the link: https://www.neb.com/products/m0386-cas9-nuclease-s-pyogenes. The quality of in vitro transcription and self-processing can be analyzed by electrophoresis in 12% denaturing urea polyacrylamide gels. The RNA bands are stained with ethidium bromide and visualized using a UV transilluminator. To analyze the DNA cleavage products generated by Cas9 and the gRNA from the in vitro transcription, regular 1% agrose gel is adequate.

-

Table 2.

PCR conditions for amplification of the RGR unit

| 98 °C | 30 sec | 1 cycle |

| 98 °C | 10 sec | 30 cycles |

| 58 °C | 10 sec | |

| 72 °C | 15 sec | |

| 72 °C | 2 min | 1 cycle |

Table 5.

In vitro transcription of RGR to produce gRNA molecules

| Total | 20 μl |

| 5x transcription buffer | 4 μl |

| 100 mM DTT | 2 μl |

| ~20 U/μl recombinant RNasin RNase inhibitor | 0.5 μl |

| 2.5 mM each rNTPs | 4 μl |

| Template DNA (PCR fragment) (10–50 ng/μl [final]) | x μl |

| T7, SP6 or T3 RNA polymerase | 1 μl |

| H2O | (8.5 - x) μl |

D. Transformation of the RGR plasmid into Arabidopsis

The final plasmid with the RGR construct was transformed into Arabidopsis through Agrobacterium-mediated floral dipping method (Clough and Bent, 1998). The transgenic T1 plants were identified either as hygromycin-resistant or producing mCherry fluorescence (Gao et al., 2015 and 2016). T1 plants were screened for editing events using PCR and restriction digestion as described in Gao et al., 2015 and 2016.

Data analysis

Our RGR-based production of functional gRNAs has been successful both in vitro and in vivo (Gao and Zhao, 2014; Gao et al., 2015 and 2016). We initially produced a gRNA targeting GFP using the RGR design. The gRNA was produced in vitro from the SP6 promoter using the commercially available SP6 RNA polymerase (Gao and Zhao, 2014). In vitro digestion assays indicated that the gRNA was fully functional (Gao and Zhao, 2014). We used the same RGR design to produce gRNA in yeast using the ADH promoter, an RNA polymerase II promoter (Gao and Zhao, 2014). Such a construct led to successful editing of the GFP gene in yeast. We further introduced an RGR design in Arabidopsis to produce a gRNA targeting the Arabidopsis ABP1 gene. Multiple stable heritable mutations in the ABP1 gene have been obtained (Gao et al., 2015 and 2016). For example, we made a construct that uses RGR for one gRNA production and the U6 promoter to produce another gRNA. The two gRNA molecules target two discrete sites of the ABP1 gene in Arabidopsis and were designed to generate a 771 bp deletion (Gao et al., 2016). We detected the intended deletions in 5 out of 61 T1 plants. Two of the T1 plants produced Cas9-free, stable homozygous mutants at the T2 generation (Gao et al., 2016).

The RGR design has been adapted for editing genes in other organisms (Nissim et al., 2014; Yoshioka et al., 2015).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This protocol was initially developed at University of California San Diego when YG was a graduate student there. The protocol was further improved at Huazhong Agricultural University. Authors would like to thank support from the National Gene Transformation grant #2016ZX08010002-002 to RW and NIH grant R01GM114660to YZ.

References

- 1.Clough S, Bent A. Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998;16(6):735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D, Lin S, Barretto R, Habib N, Hsu PD, Wu X, Jiang W, Marraffini LA, Zhang F. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 2013;339(6121):819–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gao X, Chen J, Dai X, Zhang D, Zhao Y. An effective strategy for reliably isolating heritable and Cas9-free Arabidopsis mutants generated by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing. Plant Physiol. 2016;171(3):1794–1800. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.00663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gao Y, Zhang Y, Zhang D, Dai X, Estelle M, Zhao Y. Auxin binding protein 1 (ABP1) is not required for either auxin signaling or Arabidopsis development. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2015;112(7):2275–2280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1500365112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao Y, Zhao Y. Self-processing of ribozyme-flanked RNAs into guide RNAs in vitro and in vivo for CRISPR-mediated genome editing. J Integr Plant Biol. 2014;56(4):343–349. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gibson DG, Young L, Chuang RY, Venter JC, Hutchison CA, 3rd, Smith HO. Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat Methods. 2009;6(5):343–345. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mali P, Yang L, Esvelt KM, Aach J, Guell M, DiCarlo JE, Norville JE, Church GM. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science. 2013;339(6121):823–826. doi: 10.1126/science.1232033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nissim L, Perli SD, Fridkin P, Lu TK. Multiplexed and programmable regulation of gene networks with an integrated RNA and CRISPR/Cas toolkit in human cells. Mol Cell. 2014;54(4):698–710. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sambrook J, Russell DW. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 3. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2001. pp. 1105–1111. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoshioka S, Fujii W, Ogawa T, Sugiura K, Naito K. Development of a mono-promoter-driven CRISPR/Cas9 system in mammalian cells. Sci Rep. 2015;5:18341. doi: 10.1038/srep18341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.