Abstract

The interaction between IscU and HscB is critical for successful assembly of iron–sulfur clusters. NMR experiments were performed on HscB to investigate which of its residues might be part of the IscU binding surface. Residual dipolar couplings (1DHN and 1DCαHα) indicated that the crystal structure of HscB [Cupp-Vickery, J. R., and Vickery, L. E. (2000) Crystal structure of Hsc20, a J-type cochaperone from Escherichia coli, J. Mol. Biol. 304, 835–845] faithfully represents its solution state. NMR relaxation rates (15N R1, R2) and 1H–15N heteronuclear NOE values indicated that HscB is rigid along its entire backbone except for three short regions which exhibit flexibility on a fast time scale. Changes in the NMR spectrum of HscB upon addition of IscU mapped to the J-domain/C-domain interface, the interdomain linker, and the C-domain. Sequence conservation is low in the interface and in the linker, and NMR changes observed for these residues likely result from indirect effects of IscU binding. NMR changes observed in the conserved patch of residues in the C-domain (L92, M93, L96, E97, E100, E104, and F153) were suggestive of a direct interaction with IscU. To test this, we replaced several of these residues with alanine and assayed for the ability of HscB to interact with IscU and to stimulate HscA ATPase activity. HscB(L92A,M93A,F153A) and HscB(E97A,E100A,E104A) both showed decreased binding affinity for IscU; the (L92A,M93A,F153A) substitution also strongly perturbed the allosteric interaction within the HscA • IscU • HscB ternary complex. We propose that the conserved patch in the C-domain of HscB is the principal binding site for IscU.

Proteins containing iron–sulfur clusters play essential roles in important biochemical processes, such as electron transfer, catalysis, and regulation of gene expression (1, 2). The iron–sulfur clusters of some proteins can be assembled spontaneously in vitro (3-5), but in vivo assembly is generally mediated by a complex suite of proteins. In eubacteria the Isc gene cluster, iscRSUA-hscBA-fdx,1 encodes several proteins with housekeeping biosynthetic functions (6). The assembly process appears to be evolutionarily conserved, because, with the exception of the regulatory protein IscR, homologues of each of these proteins can also be found in eukaryotes (7). Extensive biochemical and genetic studies (4, 8-12) have shown that iron–sulfur cluster biogenesis proceeds through the assembly of a cluster on the scaffold protein IscU (Isu in yeast) followed by its transfer to a recipient apoprotein. The efficiency of the second step is greatly increased if a molecular chaperone system, composed of HscA and HscB (Ssq1 and Jac1, respectively, in yeast), is present during the process (13-15).

HscB (20 kDa) is a J-type cochaperone protein that regulates the ATPase activity of HscA and helps to target IscU to its substrate binding domain (16). Isothermal titration calorimetry indicated that Escherichia coli HscB and IscU interact directly with a 1:1 stoichiometry and modest affinity (Kd of ∼10 μM for apo form) (16). The crystal structure of E. coli HscB revealed that the protein consists of three domains (17). The fold of the N-terminal J-domain (residues 1–75) is similar to those of other J-domain fragments (18-21). The interdomain linker (residues 76–83) is very flexible and lacks a well-defined secondary structure. The C-domain (residues 84–171) adopts a compact three-helix bundle structure. The J- and C-domains were found to interact over a ∼650 Å2 surface that is, for the most part, inaccessible to solvent. Analysis of conserved residues identified a cluster of acidic residues on one face of the C-domain. The possibility that this region might be important in target protein binding was tested by mutating six of the residues in this region of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Jac1 to alanines (22). The hexa mutant showed reduced affinity for Isu1 in vitro, consistent with this region participating in a binding interaction. However, pairwise mutations of these residues had only modest effect on the affinity; this suggested that Jac1 and Isu1 may interact over a broad surface area. The same study also showed that, under conditions where the in vivo function of Ssq1 is carried out by the more general hsp70-type chaperone Ssc1, efficient interaction between Jac1 and Isu1 remains critical for successful completion of iron–sulfur cluster biosynthesis.

To better understand the requirement for the interaction between HscB and IscU, we used NMR spectroscopy to investigate HscB in its free form and in the presence of apoIscU. In addition, we used ATPase assays to evaluate the ability of select HscB mutants to bind IscU and target it to HscA. Here we report our results on the solution structure of free HscB and on the most likely binding site for IscU.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Chemicals, Bacterial Strains, and Alignment Media

QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kits were purchased from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA). E. coli strain DH5α was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) and strain BL21 from Novagen (San Diego, CA). 15NH4Cl, [U-13C]-d-glucose, and [15N]glycine were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (Andover, MA). Other chemicals, including natural abundance amino acids, Tris • HCl, and DTT, were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). DE-52 resin was purchased from Whatman Inc. (Florham Park, NJ). Precast gels for electrophoresis, Mark12 Unstained Standard, and EnzCheck kits were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Filamentous phage Pf1 was purchased from Asla Biotech (Riga, Latvia). Protein standards for gel filtration were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Site-Directed Mutagenesis

Mutations in vectors for expressing mutants of HscB were generated using the QuikChange technique and were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Expression and Purification of Proteins

IscU, HscA, and unlabeled HscB proteins were produced and purified as described previously (16). To produce [U-15N]HscB and [U-13C,U-15N]HscB, colonies of E. coli strain DH5α, containing the pTrcHsc20 plasmid (18), were selected and grown for 9 h at 37 °C in 9 mL of LB broth containing 100 μg of ampicillin/mL. This starter culture (100 μL) was then used to inoculate 250 mL of LB broth containing 100 μg of ampicillin/mL, and this was grown for 16 h at 37 °C. Cells from the 250 mL culture were used to inoculate 1 L of M9 minimal medium supplemented with 100 μg of ampicillin/mL, 1 mL of vitamin solution (23), 1 mL of trace minerals solution (24), and 2 g of unlabeled glucose and 1 g of 15NH4Cl ([U-15N]HscB) or 4 g of [U-13C]-d-glucose and 2 g of 15NH4Cl ([U-13C,U-15N]HscB). Gene expression was induced at A600 ≈ 1 by adding IPTG to a final concentration of 0.4 mM. Protein production was allowed to proceed for ∼16 h, after which cells were harvested and stored at −80 °C. Cells were thawed and lysed by sonication at 4 °C in TED buffer (50 mM Tris • HCl, pH 7.4, 1 mM DTT, 0.5 mM EDTA) containing 0.4 mM PMSF to inhibit proteolysis. The lysate was centrifuged at 29416g, and the soluble supernatant was applied to a room temperature DE-52 column. HscB was eluted using a linear gradient from 0 to 100 mM NaCl followed by isocratic elution with 100 mM NaCl. Fractions were analyzed by gel electrophoresis, pooled and concentrated by ultrafiltration, and subjected to size exclusion chromatography using a HiPrep Sephacryl 26/60 S100 column (Amersham). Fractions were analyzed by gel electrophoresis, and those appearing homogeneous were pooled, concentrated by ultrafiltration, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C.

Selectively reverse-labeled HscB samples were prepared using the same protocol, with an additional step of adding a single natural abundance amino acid (largely 14N) to the cell culture immediately prior to induction of gene expression: 434 mg of l-arginine • HCl, 400 mg of l-histidine • HCl • H2O, 250 mg of l-threonine, or 520 mg of dl-lysine. A sample incorporating [15N]glycine was produced by adding 550 mg of [15N]glycine to a growth medium in which natural abundance NH4Cl was used in place of 15NH4Cl. Because the host cell strain used for protein production was not auxotrophic for glycine, partial metabolic scrambling of the label occurred, yielding a sample with labeling pattern [15N-glycine,15N-serine,15N-tryptophan]HscB.

NMR Samples

Samples used for NMR resonance assignment typically contained 1 mM ([U-13C,U-15N] or selectively reverse-labeled) HscB in 18-22 mM Tris • HCl, pH 7.3–7.5, 9 mM DTT, 0.2 mM EDTA, and 7% D2O. In addition to these components, certain samples used for RDC data collection also contained 11 mg/mL Pf1 phage. The sample used for 15N relaxation data collection contained 0.9 mM [U-15N]HscB in 22 mM Tris • HCl, pH 7.4, 9 mM DTT, and 7% D2O. Starting samples for chemical shift perturbation studies contained 0.5 mM [U-15N]HscB in 20 mM Tris • HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM DTT, and 9% D2O or 1.6 mM IscU in 18 mM Tris • HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM DTT, and 9% D2O. Samples used for line broadening measurements contained 0.5 mM [U-15N]HscB in 20 mM Tris • HCl, pH 7.3, 10 mM DTT, and 6% D2O and varying concentrations of IscU (0, 0.003, 0.005, 0.03, 0.05, or 0.125 mM). DSS was used as an internal reference for all titration data.

NMR Data Collection and Assignment

Unless otherwise specified, NMR spectra were recorded at 40 °C on Varian 600, 800, and 900 MHz Unity-Inova spectrometers equipped with z-axis gradient cold probes. All spectra were processed with NMRPipe (25) and analyzed with Sparky (26). Samples of [U-13C,U-15N]HscB were used for acquiring data sets used for sequence-specific assignments: 2D 15N-TROSY-HSQC, 3D TROSY-HNCO, 3D HNCACB, 3D CBCA(CO)NH, and 15N-NOESY-TROSY (mixing time 100 ms). To help resolve ambiguous assignments, 2D 15N-TROSY-HSQC spectra were also recorded on 1 mM samples of [15Nglycine,15N-serine,15N-tryptophan]HscB, [U-15N,14N-histidine]HscB, [U-15N,14N-lysine]HscB, [U-15N,14N-arginine]-HscB, and [U-15N,14N-threonine]HscB.

Residual Dipolar Coupling Measurements

1DHN and 1DCαHα residual dipolar couplings were obtained by comparing coupled spectra in the absence and presence of orienting medium. Coupled spectra were acquired at 40 °C on a Bruker 600 MHz DMX-Avance spectrometer and included a 3D HN-coupled HNCO (27) and a 3D Hα-coupled HN(CO)CA experiment (28). Fitting of RDC data to the crystal structure of HscB (PDB file 1FPO) (17) was carried out for each domain of HscB separately as well as for the two domains simultaneously. RDCs of highly flexible residues, i.e., residues with crystallographic B-factors larger than the sum of the average B-factor plus one standard deviation, were not used in any of the calculations. The Q-factor (eq 1) (29) was used to evaluate the quality of each fit.

| (1) |

Data were analyzed and fitted using NMRPipe (25) in combination with in-house written scripts.

15N Relaxation and 1H-15N Heteronuclear NOE Measurements

15N relaxation data were measured using standard pulse sequences (30, 31) on a Varian 600 MHz Unity-Inova spectrometer equipped with a z-axis gradient cold probe at 40 °C. Longitudinal relaxation (R1) data were collected with relaxation delays of 10, 120, 240, 400, 720, 1100, 1500, and 2200 ms; transverse relaxation (R2) data were measured with relaxation delays of 10, 30, 50, 70, 90, 110, and 130 ms. Peak intensities were subsequently determined as a function of the relaxation delay and were fitted to a single exponential using the peak height extension in Sparky (26). 1H-15N heteronuclear NOE data were acquired with interleaved, unenhanced and enhanced (3 s 1H excitation period) spectra. 1H-15N heteronuclear NOE values represent the ratio of peak heights from the enhanced and unenhanced spectra. All data sets were collected in duplicate.

Molecular Mass Determination

The molecular mass of the IscU • HscB complex was estimated by calibrated gel filtration. Chromatography was carried out at 25 °C using a Superdex 200 10/300 GL column connected to an ÄKTA-purifier system (GE Healthcare). The column was first equilibrated in 20 mM Tris • HCl, pH 7.5, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, and 203 mM NaCl; subsequently, a ∼100 μL aliquot of sample was applied and eluted using the same buffer. Total protein concentration for injected samples was 0.2 mM (HscB sample), 0.4 mM (IscU sample), or 0.2–0.8 mM (IscU • HscB mixtures). IscU • HscB samples contained IscU and unlabeled HscB in a molar ratio of 1:4 or 3:1. Standards used included catalase (232 kDa), albumin (69.2 kDa), ovalbumin (43 kDa), rhodanese (33.3 kDa), ribonuclease A (13.7 kDa), and cytochrome c (12.4 kDa). All samples were prepared in equilibration buffer. Kave values were calculated according to eq 2, where Vo is the column void volume as determined with Blue Dextran, Vc is the geometric column volume, and Ve is the elution volume of the molecule under consideration.

| (2) |

Runs for standards and Blue Dextran were carried out in duplicate, whereas runs for HscB, IscU, and IscU • HscB were carried out in triplicate. Selected fractions from these gel filtration experiments were subsequently analyzed for IscU and HscB content using SDS–PAGE.

Chemical Shift Perturbation Measurements

Apo-IscU was titrated into a sample of [U-15N]HscB, and a 2D 15N-TROSYHSQC spectrum was recorded after the addition of each aliquot. Titrations were performed at 40 °C with spectra recorded on a Varian 800 MHz Unity-Inova spectrometer. Unless otherwise noted, the final molar ratio of IscU:HscB was 2.4. IscU-induced changes in amide peak position of HscB, ΔδHN (in ppm), are reported as a combination of the changes in the proton (ΔδH) and nitrogen (ΔδN) dimensions according to eq 3 (32).

| (3) |

Spectra were processed with NMRPipe (25) and analyzed with Sparky (26).

Line Broadening Measurements

A 2D 15N-HSQC spectrum was recorded for each of six [U-15N]HscB • IscU samples, identical in all respects except for the IscU concentration. Peak widths (at half-peak height), in both dimensions, were extracted from each spectrum for well-resolved peaks. IscU-induced changes in amide peak width of HscB, ΔLWHN (in Hz), are reported as a combination of the changes in the proton (ΔLWH) and nitrogen (ΔLWN) dimensions according to eq 4.

| (4) |

HSQC spectra were recorded at 40 °C on a Bruker 600 MHz DMX-Avance spectrometer and were processed and analyzed with NMRPipe (25). For selected residues, data for the calculation of ΔLWHN were obtained from HSQC spectra recorded during the IscU titration as described in the previous section.

Circular Dichroism

Spectra were recorded on a Jasco J-810 spectropolarimeter from 190 to 250 nm (far-UV) or 250 to 320 nm (near-UV). Far-UV measurements used 15 μM protein in 20 mM Tris • HCl, pH 7.9, 1 mM DTT, 0.5 mM EDTA buffer and a 0.5 mm path length cuvette. Four scans were averaged, and the buffer baseline was subtracted. Near-UV measurements used 33 μM protein in 20 mM Tris • HCl, pH 7.9, 1 mM DTT, 0.5 mM EDTA buffer and a 10 mm path length cuvette. Twelve scans were averaged, and the buffer baseline was subtracted. The temperature for all measurements was 22 °C.

ATPase Assays

ATPase rates were determined at 23 °C in HKM buffer (50 mM Hepes, pH 7.3, 150 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2) containing 1 mM ATP by measuring phosphate released using the EnzCheck coupled enzyme phosphate assay kit as described previously (16).

Sequence Alignment

Homologues of E. coli HscB were identified using TBLASTN (BLASTP for γ-proteobacteria) with the E. coli sequence as a query. Four separate searches were performed, with each search limited to a subset of organisms: α-proteobacteria, β-proteobacteria, γ-proteobacteria, and eukaryota. After discarding sequences with E-values greater than 1, 187 sequences remained: 21 α-proteobacteria, 48 β-proteobacteria, 69 γ-proteobacteria, and 49 eukaryotes [eukaryotic sequences were further subdivided into fungi/metazoa (25), vertebrates (11), and other eukaryotes (13)] (Tables S1-S6). Each group of sequences was aligned with ClustalW2 (33) using default parameters. Each result was analyzed separately, and residues were classified as invariant (identical in all sequences within a group), highly conserved (similar in ≥90% of sequences within a group), semiconserved (similar in ≥80% of sequences within a group), or nonconserved. A representative sequence was chosen from each group (six sequences in total), and these were also aligned using ClustalW2. Global sequence conservation among all 187 homologues was evaluated by considering both the individual group alignments and the alignment of representative sequences. Residues were classified as invariant (identical in all sequences), highly conserved (similar in ≥90% of sequences), semiconserved (similar in ≥80% of sequences), or nonconserved.

RESULTS

Backbone Resonance Assignment of Free HscB

We began backbone resonance assignment of free HscB at 25 °C, the temperature at which most of the biochemical studies on this protein were conducted (14, 16, 34, 35). The 15N-HSQC (data not shown) showed a folded protein with many well-dispersed peaks, although also with a large, overlapped region (1H dimension, 7.5–8.5 ppm; 15N dimension, 118–122 ppm). The low signal-to-noise ratio of the 3D HNCACB spectrum (in particular for peaks corresponding to interresidue 1HN–15N–13Cβ correlations) combined with peak overlap made the assignment process arduous. Because previous studies (D. T. Ta and L. E. Vickery, unpublished results) showed that HscB is stable to at least 45 °C, we collected a 3D HNCACB spectrum at 40 °C. The signal-to-noise ratio was visibly higher than that at 25 °C; therefore, all remaining data sets were collected at 40 °C. Final resonance assignments for free HscB were based on information from 2D 15N-TROSY-HSQC, 3D HNCO, 3D CBCA(CO)NH, 3D HNCACB experiments and a 3D 15N-NOESY-TROSY (τm = 100 ms) experiment. Ambiguous assignments were resolved using 2D 15N-TROSY-HSQC data collected from selectively 15N-labeled or 14N-unlabeled HscB samples. Complete or near-to-complete resonance assignments were achieved for 162 out of 168 nonproline residues, namely, D2-L15, T17-S40, A42-H63, A68-V86, and T89-F171.

Use of Residual Dipolar Coupling (RDC) Data to Compare the Structure of HscB in Solution to That in the Crystal

NMR RDCs contain information about the orientation of atomic bond vectors in a protein and thus can be used to test the validity of a particular structural model (36). We measured one-bond RDCs for free HscB to compare its structure in solution with that determined previously by X-ray crystallography (17). The crystallographic asymmetric unit contained three molecules, A, B, and C, but because residues 31–44 are not observed in the electron density of molecule C, we used only molecules A and B for the analysis described in the following section. We measured a total of 253 experimental RDCs (143 1DHN and 110 1DCαHα), and after exclusion of those corresponding to residues in highly flexible regions (residues 16–23, 26–28, 33–42, 78–85, and 165–171 for molecule A; residues 33–38, 76–87, and 167–171 for molecule B), approximately 220 remained for use in the fitting procedure. Individual Q values for the J- and C-domains were below ∼0.250 for both molecules (Table 1), indicating good agreement between their crystal (−170 °C) and solution (40 °C) structures. Fitting the J- and C-domains together increased Q values only modestly with both molecules (A and B) yielding Q values of ∼0.243 (Table 1, Figure 1). This indicates that the relative orientation of the J- and C-domains is similar in the crystalline and solution states. We conclude that the L-shaped topology of the helical HscB structure is maintained in solution and, moreover, that the crystal structure represents faithfully its solution state.

Table 1.

Summary of RDC Fitting Results for HscBa

| molecule A |

molecule B |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| domain | J | C | both | J | C | both |

| no. of residues | 75 | 88 | 171 | 75 | 88 | 171 |

| no. of RDCs | 79 | 136 | 218 | 98 | 139 | 237 |

| Q | 0.224 | 0.205 | 0.244 | 0.196 | 0.172 | 0.242 |

Fitting was performed for the J- (J) and C-domains (C) individually as well as together (both). Molecules A and B refer to two of the three HscB molecules found in the crystallographic asymmetric unit. “no. of residues” refers to the total number of residues in the indicated domain; “no. of RDCs” refers to the total number of RDCs used in the fitting procedure. For each molecule, residues with crystallographic B-factors greater than the average plus one standard deviation were excluded from the fitting procedure. Q measures the quality of the correlation and is calculated according to Q ) rms(Dcalc − Dobs)/rms(Dobs) (29). Lower values of Q indicate greater correlation between the observed and calculated RDCs.

Figure 1.

Correlation between experimentally measured residual dipolar couplings 1DHN and 1DCαHα (1Dobs) and values predicted (1Dpred) from the crystal structure of HscB (17). The coordinates of molecules A and B of the crystallographic asymmetric unit were used in separate calculations. The quality factor for the correlation, Q, was calculated from Q = rms(Dcalc − Dobs)/rms(Dobs)(29). Both molecules proved to be equally good models of the solution structure of HscB as indicated by their low Q values.

Backbone Dynamics of HscB

Crystallographic B-factors can indicate which atoms in a protein have the most freedom of movement and therefore provide some insights into the dynamics of the protein. The B-factors reported for HscB (17) suggest that overall the J-domain is less rigid than the C-domain and that the interdomain linker is the most mobile region of the protein (Figure 2). The degree of mobility in other regions of the protein differed among the molecules in the asymmetric unit. In particular, the largest differences were seen for the N-terminal region of helix A, the loop connecting helices D and E, and the C-terminus (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of internal dynamics of HscB in the solution (this work) and crystal (17) states. Backbone B-factors (17) for molecules A (×) and B (●) of the crystallographic asymmetric unit, 1H–15N heteronuclear NOE values, and 15N R2/R1 relaxation time ratios are plotted against HscB sequence. Diffraction data were collected at −170 °C and NMR data were collected at 40 °C. For each NMR parameter, two separate data sets were collected, analyzed, and incorporated into error calculations.

NMR relaxation studies can also provide detailed information about the internal dynamics occurring in proteins (37). We measured 15N R1 and R2 as well as 1H–15N heteronuclear NOE values at 40 °C for free HscB to compare its dynamics in solution with that in the crystal state (17). The mean R2/R1 and NOE values for the protein were 24.5 ± 5.6 and 0.76 ± 0.19, respectively. Larger than average R2/R1 values were not observed for any part of the protein; this indicates that HscB does not undergo internal motions on a slow (μs to ms) time scale. Lower than average R2/R1 and NOE values were obtained for three regions of the protein: the loops connecting helices A and B as well as helices C and D, residues adjacent to these loops, and residues at the extreme C-terminus of the protein (Figure 2). This result indicates that these regions show appreciable flexibility on a fast (ps to ns) time scale, whereas the rest of the HscB backbone remains quite rigid.

From comparison of the NMR relaxation data and the crystallographic B-factors, we conclude that the internal dynamics of HscB are qualitatively similar in solution and in the crystal state. The agreement is better for molecule B than for molecule A of the crystal.

Molecular Mass of the IscU • HscB Complex

To ensure that we were able to generate the IscU • HscB complex required for NMR studies, we first used analytical gel filtration to study the hydrodynamic properties of samples of IscU, HscB, and mixtures of IscU and HscB. The elution profile of IscU consisted of a single peak at a calibrated value of 24.3 ± 0.6 kDa (Figure 3A). This value is significantly larger than expected for a 14 kDa monomeric protein but is slightly smaller than expected for a dimer. Because both EDTA and DTT were present in our elution buffer, it is unlikely that the observed species corresponds to a metal- or disulfide bond-mediated IscU dimer. The high apparent molecular mass may result from the flexible and partly unstructured nature of IscU (38-40). The elution profile of HscB consisted of a single peak at 32.8 ± 0.5 kDa (Figure 3A). This value is also larger than expected for a 20 kDa monomeric protein but is in good agreement with a previous study (41) and is likely due to the highly asymmetric structure of HscB (17). The elution profile of the IscU • HscB mixture (3:1 molar ratio) contained two overlapped peaks at 24 ± 1 and 40 ± 3 kDa (Figure 3A). SDS–PAGE suggested that the 24 kDa peak corresponds to (excess) IscU and the ≅40 kDa peak to the IscU • HscB complex (Figure 3B). The elution profile of the IscU • HscB mixture (1:4 molar ratio) also contained two overlapped peaks at 34 ± 1 and 39 ± 2 kDa (Figure 3A). SDS–PAGE suggested that the 34 kDa peak corresponds to (excess) HscB and the ≅39 kDa peak to the IscU • HscB complex (Figure 3B). The apparent value of ≅40 kDa is slightly larger than the expected mass of a 1:1 IscU • HscB complex (14 kDa + 20 kDa = 34 kDa). These results suggest that we are able to generate an IscU • HscB complex, that it contains one molecule each of IscU and HscB, and that the shape of the complex is slightly asymmetric.

Figure 3.

Gel filtration analysis of IscU, HscB, and IscU • HscB mixtures on a Superdex 200 column. (A) Representative elution profiles of IscU (500 μg in 100 μL), HscB (400 μg in 100 μL), IscU • HscB (1:4 molar ratio; 69 μg of IscU and 400 μg of HscB in 100 μL), and IscU • HscB (3:1 molar ratio; 825 μg of IscU and 400 μg of HscB in 100 μL). Fractions analyzed by SDS–PAGE are indicated by gray shadowing and fraction labels on the top of the graph. (B) SDS–PAGE analysis of the IscU, HscB, and IscU • HscB fractions indicated in panel A.

Chemical Shift Perturbation and Line Broadening Effects

Chemical shift perturbation studies exploit the differences in chemical shift between the free and substrate-bound forms of a protein to identify regions that undergo changes as a result of the binding event (42). We probed differences in the chemical shift of free and IscU-bound HscB by recording a series of 15N-HSQC spectra of [U-15N]HscB in the presence of varying amounts of IscU. Many peaks, in particular those from the J-domain, did not shift significantly (average ΔδHN value of 0.004 ppm) (Figure 4; Figure 5, solid gray lines); this suggests that IscU has a minimal effect on this region of HscB.

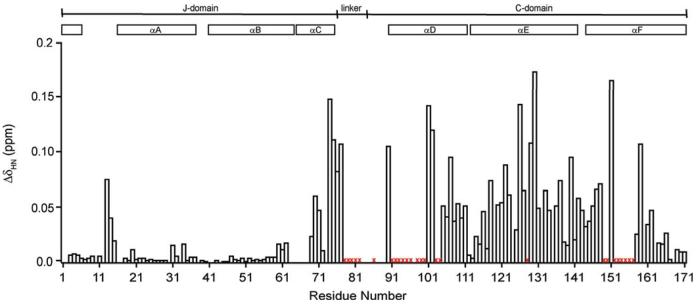

Figure 4.

Combined chemical shift changes (ΔδHN) of HscB upon binding to IscU. ΔδHN was calculated according to ΔδHN = [(ΔδH)2 + (ΔδN/6)2]1/2 (32). Residues whose peaks disappear during the titration are marked with a red ×. Values are not shown for residues that lack an observable 1HN–15N cross-peak in free HscB (M1, D2, D16, T17, S38, Q41, A42, L65–A68, D78, H84, T85, and R87–T89), have an overlapped 1HN–15N cross-peak in free and/or bound HscB (Q44, Q83, M124, and M132), or are prolines (P10, P33, and P64). The diagrams at the top of the figure show the location of the domains and secondary structural elements of HscB.

Figure 5.

Representative NMR changes observed during titration of [U-15N]HscB with IscU. (A) Combined chemical shift changes (ΔδHN = [(ΔδH)2 + (ΔδN/6)2]1/2; ref 32). Many peaks (e.g., A52) exhibited very small shifts during the titration. Other peaks (e.g., T140) exhibited more pronounced shifts that saturated at an IscU:HscB molar ratio of 2.4. A subset of peaks (e.g., S81) showed small initial shifts before disappearing from the HSQC spectrum at an IscU:HscB molar ratio of ≅0.25. A handful of peaks (e.g., X1) appeared at IscU:HscB molar ratios greater than 1 and showed very small shifts. (B) Line broadening changes (ΔLWHN = ΔLWH + ΔLWN). Many peaks (e.g., A52) became slightly broader due to the higher mass of the IscU • HscB complex. Other peaks (e.g., T140) broadened and subsequently resharpened during the titration. This type of behavior generally results from intermediate (μs to ms lifetimes) association–dissociation kinetics of a protein complex (43, 44). A subset of peaks (e.g., S81) showed severe line broadening at substoichiometric levels of IscU, disappearing from the HSQC spectrum at an IscU:HscB molar ratio of ≅0.25. The source of this type of behavior is unknown. A handful of peaks (e.g., X1) appeared at IscU:HscB molar ratios greater than 1, sharpening as the titration progressed. Attempts at assigning these peaks were unsuccessful. Line broadening data for A52, T140, and X1 were recorded at 800 MHz; line broadening data for S81 were recorded at 600 MHz.

Peaks corresponding to residues in other parts of HscB showed pronounced chemical shift changes (Figure 4; Figure 5, solid black lines) indicative of appreciable environmental changes in the presence of IscU (43, 44). These residues were located in the interdomain linker (average ΔδHN values of 0.137 ppm), near the J-domain/C-domain interface (average ΔδHN value of 0.049 ppm), and in the C-domain (average ΔδHN values of 0.058 ppm).

Some peaks showed small initial chemical shift changes and severe line broadening at substoichiometric levels of IscU (Figure 4, red ×; Figure 5, solid red lines). These peaks disappeared from the HSQC spectrum at an IscU:HscB molar ratio of ≅0.25, and therefore, subsequent changes (if any) in their chemical shift positions could not be followed. Residues showing this behavior were localized to the second half of the interdomain linker and the C-domain (Figure 4, red ×). Although the line broadening mechanism remains to be determined, these residues appear to be affected by a major environmental change.

Several new peaks appeared in the HSQC spectrum at IscU:HscB molar ratios greater than 1 (Table S7) and showed small chemical shift changes during the remainder of the titration (Figure 5, broken red lines). These peaks, which have not yet been assigned, appear to correspond to residues of HscB that experience large chemical shift changes upon formation of the complex.

Alanine-Substituted HscBs

The fact that a number of the residues showing extreme NMR line broadening are highly conserved among HscB homologues suggested that they might comprise part of the IscU binding site (see Discussion). To test this possibility, we investigated the effect of alanine substitutions on the ability of HscB to interact with IscU and stimulate the ATPase activity of HscA. Previous studies have shown that IscU and HscB individually enhance HscA ATPase activity modestly (≅4–8-fold) but together can synergistically stimulate activity up to ≅400-fold (16, 41). Furthermore, HscB synergistically reduces the concentration of IscU required for half-maximal stimulation from ≅30 μM to ≅2 μM IscU (16). We reasoned that if the alanine mutations modify the IscU • HscB interaction, the synergism between the two proteins might also be affected. A change in the maximum level of HscA ATPase stimulation would suggest a change in the allosteric coupling between IscU and HscB within the HscA • IscU • HscB ternary complex, whereas a change in the concentration of IscU required for half-maximal stimulation of HscA would suggest a change in the affinity of HscB for IscU.

Alanine substitutions in HscB were made either in a cluster of charged residues, HscB(E97A,E100A,E104A), or in a nearby hydrophobic patch, HscB(L92A,M93A,F153A). The far- and near-UV CD spectra of each mutant were identical to those of wild-type HscB (data not shown), indicating that the alanine substitutions did not alter the secondary or tertiary structure of HscB. Wild-type HscB elicited a ≅4-fold maximal stimulation of HscA ATPase activity, with half-maximal stimulation occurring at ≅6 μM HscB (Figure 6A, solid line and filled circles). HscB(E97A,E100A,E104A) elicited a ≅4-fold maximal stimulation of HscA ATPase activity, with half-maximal stimulation occurring at ≅5 μM HscB (Figure 6A, dashed line and open squares). HscB(L92A, M93A,F153A) elicited a ≅4-fold maximal stimulation of HscA ATPase activity, with half-maximal stimulation occurring at ≅4 μM HscB (Figure 6A, dotted line and open triangles). The close agreement between results obtained for the mutants and wild-type HscB suggests that all three proteins have similar affinities and allosteric interactions with HscA.

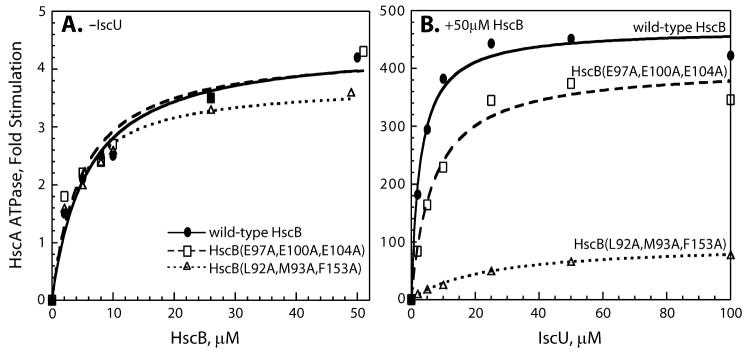

Figure 6.

Effect of HscB mutants on the ATPase activity of HscA. Results are reported as the increase in basal ATPase rates at 23 °C; curves represent best fits to the data using the following values for maximal stimulation and concentration of HscB (panel A) or IscU (panel B) giving half-maximal stimulation. (A) In the absence of IscU: wild-type HscB (●), 4.4-fold, 5.8 μM; HscB(E97A, E100A, E104A) (□), 4.3-fold, 4.9 μM; HscB(L92A, M93A, F153A) (△), 3.8-fold, 3.9 μM. (B) In the presence of IscU: wild-type HscB (●), 468-fold, 2.8 μM; HscB(E97A, E100A, E104A) (□), 404-fold, 6.9 μM; HscB(L92A, M93A, F153A) (△), 97-fold, 24 μM.

Next we examined the effect of the triple alanine substitutions on the synergism between IscU and HscB. IscU and wild-type HscB elicited a ≅470-fold maximal stimulation of HscA ATPase activity, with half-maximal stimulation occurring at ≅3 μM IscU (Figure 6B, solid line and filled circles). The maximal stimulation elicited by IscU and HscB(E97A,E100A,E104A) decreased to ≅400-fold, with the concentration of IscU required for half-maximal stimulation increasing to ≅7 μM (Figure 6B, dashed line and open squares). Given that HscB(E97A,E100A,E104A) interacts normally with HscA, these results suggest that the (E97A,E100A,E104A) triple substitution perturbs the affinity of HscB for IscU and also slightly affects the allosteric communication within the HscA • IscU • HscB ternary complex. The maximal stimulation of HscA ATPase activity elicited by IscU and HscB(L92A,M93A,F153A) decreased to ≅97-fold, with the concentration of IscU required for half-maximal stimulation increasing to ≅24 μM (Figure 6B, dotted line and open triangles). Given that HscB(L92A,M93A,F153A) also interacts normally with HscA, these results suggest that the (L92A,M93A,F153A) triple substitution not only perturbs the affinity of HscB for IscU but also considerably affects allosteric communication within the HscA • IscU • HscB ternary complex.

Taken together, these results confirm that some of the residues showing severe line broadening in the NMR titrations are important for the IscU • HscB interaction. In addition, these results suggest that L92, M93, and/or F153 are more critical for this interaction than residues E97, E100, and/or E104.

DISCUSSION

The crystal structure of HscB (17) revealed an L-shaped protein, consisting of two all-α-helical domains whose relative orientation is fixed through an extensive apolar interdomain interface. Our residual dipolar coupling and 15N relaxation NMR data indicate that HscB retains in solution the fold and associated dynamics observed in the crystal. Moreover, this all-α-helical, L-shaped structure is very stable in solution at 40 °C as indicated by our ability to collect NMR data over periods of weeks.

The interaction between IscU and HscB is critical for successful assembly of iron–sulfur clusters, but our understanding of this interaction has been limited by the lack of structural information. The NMR titration results reported here indicate that three regions of HscB are affected by IscU: the interdomain linker, the J-domain/C-domain interface, and the C-domain. Because sequence conservation in the interdomain linker is low (Figure 7), we suggest that the observed NMR changes in this region are due to indirect effects of IscU binding. The most likely mechanism would be a local induced change in conformation. Sequence conservation in the J-domain/C-domain interface is also low (Figure 7), and in addition, this extensive surface is largely buried in the free form of HscB (17). Therefore, the NMR changes in this region are also likely due to indirect effects of IscU and may reflect a small change in the relative orientation of the two domains.

Figure 7.

Amino acid conservation among HscB proteins. A previous sequence alignment of HscB homologues analyzed nine sequences (17). We generated a new alignment using 187 sequences divided into six groups. The results are projected onto a representative sequence from each group. Invariant residues (identical in all sequences within a group) are highlighted in black, highly conserved residues (similar in ≥90% of sequences within a group) are highlighted in blue, and semiconserved residues (similar in ≥80% of sequences within a group) are highlighted in yellow. Global sequence conservation was evaluated by comparing the individual group alignments. “*” indicates invariant residues (identical in all sequences), “:” indicates highly conserved residues (similar in ≥90% of sequences), and “.” indicates semiconserved residues (similar in ≥80% of sequences). The diagrams at the top of the figure show the location of the secondary structural elements of E. coli HscB.

Overall sequence conservation is higher in the C-domain than in the interdomain linker or the J-domain/C-domain interface (Figure 7). In particular, a prominent conserved patch, consisting of residues L92, M93, L96, E97, E100, E104, and F153, is located on one face of the domain (Figure 8A). NMR signals from all of these residues, as well as from some of their nonconserved neighbors, undergo large changes upon addition of IscU (Figure 4, red ×). Therefore, we propose that this region of HscB contacts IscU in the complex (Figure 8B). Previous work on S. cerevisiae Jac1 identified six residues that, when mutated together to alanine, reduced the affinity of the cochaperone for Isu1 in vitro (22). The six Jac1 residues correspond to HscB residues L96, R99, E100, D103, E104, and Q107. In our NMR titration data, neither Q107 nor nearby residues (I105 and E106) undergo line broadening of the type observed for residues L96, R99, E100, D103, and E104 (Figure 4). For this reason we propose that HscB residues I105–Q107, located at the C-terminal region of helix D, are not part of the IscU binding site.

Figure 8.

Surface properties of HscB. (A) Conserved residues in the C-domain of HscB based on the alignment of 187 sequences (cf. Figure 7 and the text for details). Highly conserved residues are highlighted in blue, and semiconserved residues are highlighted in yellow. (B) The proposed interaction site for IscU. HscB surface residues showing dramatic NMR changes in the presence of IscU are clustered on one side of the protein (red coloring). Residues for which NMR data do not exist, but which might also be part of this binding site, are shaded dark gray. (C) Surface electrostatic potential of HscB. White represents neutral potential, blue represents positive potential, and red represents negative potential. The proposed binding site for IscU shown in panel B is circled with a dashed line. Coordinates for the HscB structure are from PDB file 1FPO (17); images were prepared with PyMol (49).

Although protein–protein interfaces vary to a large extent in their size, shape, and amino acid composition, they exhibit some common properties. Almost all interfaces bury at least 600 Å2 of total surface area (47), and a large part of this buried surface is hydrophobic (48). The energetic contributions of individual residues across the interface vary widely, with a few key residues contributing significantly to the binding free energy of the complex (a hot spot) (48). The proposed contact site on HscB conforms well to these rules. Together, R87, D88, T89, L92, M93, Q95, L96, E97, R99, E100, D103, E104, R149, R152, F153, D155, K156, and L157 form a surface of area ≅430 Å2 that could become buried upon contact with IscU. If the surface buried on IscU is of similar size, the total surface buried by the IscU • HscB interface will be well above the suggested 600 Å2 threshold. Notably, the size of the proposed contact site may also explain why pairwise mutations of S. cerevisiae Jac1 residues had only modest effects on the cochaperone's affinity for Isu1 (22). The chemical character of the proposed contact site on HscB is best described by a hydrophobic patch (L92, M93, L96, and F153) that is bordered by an acidic region on one side (E97, E100, D103, and E104) and a predominantly basic region on the other side (R87, R99, R152, and K156) (Figure 8C). It is possible that whereas the hydrophobic patch provides stability to the complex, the charged areas surrounding it provide specificity and direct the orientation of HscB and IscU. Several of the residues within the proposed contact site correspond to types commonly found in hot spots (48); these include M93, E97, R99, E100, D103, E104, R152, and F153.

The results of the HscA ATPase assays reported here support the binding site identified by NMR spectroscopy. Both of the triple alanine substitutions decreased the affinity of HscB for IscU, but the substitutions in the hydrophobic patch (L92A,M93A,F153A) had a more profound effect than those in the acidic region (E97A,E100A,E104A). This result suggests that hydrophobic interactions provide most of the stability to the IscU • HscB complex. Unexpectedly, the (L92A,M93A,F153A) substitution also strongly perturbed the allosteric interaction within the HscA • IscU • HscB ternary complex. This finding offers clues regarding the allosteric mechanism and suggests that future analysis of the effects of single site HscB mutants could lead to a better understanding of the contributions of individual interface residues to the enzymatic activity of the ternary complex.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We are indebted to Drs. Fariba Assadi-Porter, Hamid Eghbalnia, and Milo Westler for insightful discussions. We thank Jenny Oh for help in generating the triple alanine HscB mutants.

Footnotes

This work was supported by NIH Grants GM58667 (to J.L.M.) and GM54264 (to L.E.V.) and, in part, by fellowships from the Department of Biochemistry and the Graduate Student Collaborative, University of Wisconsins–Madison (to A.K.F.). NMR data were collected at the National Magnetic Resonance Facility at Madison (NMRFAM), which is supported in part by NIH Grants P41 RR02301 and P41 GM66326.

1H, 13C, and 15N resonance assignments, 1DHN and 1DCαHα residual dipolar couplings, and 15N T1, T2, and heteronuclear NOE values have been deposited in the BioMagResBank as entry 15541.

Abbreviations: IscRSUA, iron-sulfur cluster protein R/S/U/A; HscBA, heat shock cognate protein B/A; IscU • HscB complex, a complex of IscU and HscB; [U-15N], uniformly 15N-labeled; NMR, nuclear magnetic resonance; DSS, 2,2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonic acid; CD, circular dichroism.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION AVAILABLE

Six tables containing NCBI version number, source organism, and E-value of sequences used in the ClustalW2 alignment of HscB homologues and one table containing proton and nitrogen chemical shifts of unassigned peaks in the 15N-HSQC spectrum of bound 15N-HscB. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beinert H. Iron-sulfur proteins: ancient structures, still full of surprises. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2000;5:2–15. doi: 10.1007/s007750050002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lill R, Dutkiewicz R, Elsaässer H-P, Hausmann A, Netz DJA, Pierik AJ, Stehling O, Urzica E, Mühlenhoff U. Mechanisms of iron-sulfur protein maturation in mitochondria, cytosol and nucleus of eukaryotes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1763:652–667. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng H, Westler WM, Xia B, Oh B-H, Markley JL. Protein expression, selective isotopic labeling, and analysis of hyperfine-shifted NMR signals of Anabaena 7120 vegetative [2Fe-2S]ferredoxin. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1995;316:619–634. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonomi F, Iametti S, Ta D, Vickery LE. Multiple turnover transfer of [2Fe-2S] clusters by the iron-sulfur cluster assembly scaffold proteins IscU and IscA. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:29513–29518. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504344200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kostic M, Pochapsky SS, Obenauer J, Mo H, Pagani GM, Pejchal R, Pochapsky TC. Comparison of functional domains in vertebrate-type ferredoxins. Biochemistry. 2002;41:5978–5989. doi: 10.1021/bi0200256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson D, Dean DR, Smith AD, Johnson MK. Structure, function, and formation of biological iron-sulfur clusters. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2005;74:247–281. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lill R, Mühlenhoff U. Iron-Sulfur Protein Biogenesis in Eukaryotes: Components and Mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2006;22:457–486. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010305.104538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agar JN, Zheng L, Cash VL, Dean DR, Johnson MK. Role of IscU Protein in Iron-Sulfur Cluster Biosyn-thesis: IscS-mediated Assembly of a [Fe2S2] Cluster in IscU. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:2136–2137. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agar JN, Krebs C, Frazzon J, Huynh BH, Dean DR, Johnson MK. IscU as a Scaffold for Iron-Sulfur Cluster Biosynthesis: Sequential Assembly of [2Fe-2S] and [4Fe-4S] Clusters in IscU. Biochemistry. 2000;39:7856–7862. doi: 10.1021/bi000931n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Urbina HD, Silberg JJ, Hoff KG, Vickery LE. Transfer of Sulfur from IscS to IscU during Fe/S Cluster Assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:44521–44526. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106907200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nuth M, Yoo T, Cowan JA. Iron-Sulfur Cluster Biosynthesis: Characterization of Iron Nucleation Sites for Assembly of the [2Fe-2S]2+ Cluster Core in IscU Proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:8774–8775. doi: 10.1021/ja0264596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu S.-p., Wu G, Surerus KK, Cowan JA. Iron-Sulfur Cluster Biosynthesis. Biochemistry. 2002;41:8876–8885. doi: 10.1021/bi0256781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mühlenhoff U, Gerber J, Richhardt N, Lill R. Components involved in assembly and dislocation of iron-sulfur clusters on the scaffold protein Isu1p. EMBO J. 2003;22:4815–4825. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chandramouli K, Johnson MK. HscA and HscB stimulate [2Fe-2S] cluster transfer from IscU to apoferredoxin in an ATP-dependent reaction. Biochemistry. 2006;45:11087–11095. doi: 10.1021/bi061237w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dutkiewicz R, Marszalek J, Schilke B, Craig EA, Lill R, Mühlenhoff U. The Hsp70 Chaperone Ssq1p is Dispensable for Iron-Sulfur Cluster Formation on the Scaffold Protein Isu1p. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:7801–7808. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513301200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoff KG, Silberg JJ, Vickery LE. Interaction of the iron-sulfur cluster assembly protein IscU with the Hsc66/Hsc20 molecular chaperone system of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:7790–7795. doi: 10.1073/pnas.130201997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cupp-Vickery JR, Vickery LE. Crystal structure of Hsc20, a J-type co-chaperone from Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;304:835–845. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szyperski T, Pellechia M, Wall D, Georgopoulos C, Wüthrich K. NMR structure determination of the Escherichia coli DnaJ molecular chaperone: Secondary structure and backbone fold of the N-terminal region (residues 2–108) containing the highly conserved J domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994;91:11343–11347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hill RB, Flanagan JM, Prestegard JH. 1H and 15N Magnetic Resonance Assignments, Secondary Structure, and Tertiary Fold of Escherichia coli DnaJ(178) Biochemistry. 1995;34:5587–5596. doi: 10.1021/bi00016a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pellecchia M, Szyperski T, Wall D, Georgopoulos C, Wüthrich K. NMR Structure of the J-domain and the Gly/Phe-rich Region of the Escherichia coli DnaJ Chaperone. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;260:236–250. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qian YQ, Patel D, Hartl F-U, McColl DJ. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Solution Structure of the Human Hsp40 (HDJ-1) J-domain. J. Mol. Biol. 1996;260:224–235. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andrew AJ, Dutkiewicz R, Knieszner H, Craig EA, Marszalek J. Characterization of the interaction between J-protein Jac1 and Isu1, the scaffold for Fe-S cluster biogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:14580–14587. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600842200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jansson M, Li YC, Jendeberg L, Anderson S, Montelione BT, Nilsson B. High-level production of uniformly 15N- and 13C-enriched fusion proteins in Escherichia coli. J. Biomol. NMR. 1996;7:131–141. doi: 10.1007/BF00203823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao Q, Frederick R, Seder K, Thao S, Sreenath H, Peterson F, Volkman BF, Markley JL, Fox BG. Production in two-liter beverage bottles of proteins for NMR structure determination labeled with either 15N- or 13C-15N. J. Struct., Funct., Genet. 2004;5:87–93. doi: 10.1023/B:JSFG.0000029205.65813.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goddard TD, Kneller DG. SPARKY 3. University of California; San Francisco: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cornilescu G, Bax A. Measurement of Proton, Nitrogen, and Carbonyl Chemical Shielding Anisotropies in a Protein Dissolved in a Dilute Liquid Crystalline Phase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:10143–10154. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tjandra N, Bax A. Large Variations in 13Cα Chemical Shift Anisotropy in Proteins Correlate with Secondary Structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:9576–9577. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cornilescu G, Marquardt JL, Ottiger M, Bax A. Validation of protein structure from anisotropic carbonyl chemical shifts in a dilute liquid crystalline phase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:6836–6837. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kay LE, Nicholson LK, Delaglio F, Bax A, Torchia DA. Pulse sequences for removal of the effects of cross correlation between dipolar and chemical shift anisotropy relaxation mechanisms on the measurement of heteronuclear T1 and T2 values in proteins. J. Magn. Reson. 1992;97:359–375. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farrow NA, Muhandiram R, Singer AU, Pascal SM, Kay CM, Gish G, Shoelson SE, Pawson T, Forman-Kay JD, Kay LE. Backbone dynamics of a free and a phosphopeptide-complexed Src homology 2 domain studied by 15N NMR relaxation. Biochemistry. 1994;33:5984–6003. doi: 10.1021/bi00185a040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farmer BT, II, Constantine KL, Goldfarb V, Friedrichs MS, Wittekind M, Yanchunas J, Jr, Robertson JG, Mueller L. Localizing the NADP+ binding site on the MurB enzyme by NMR. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1996;3:995–997. doi: 10.1038/nsb1296-995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chenna R, Sugawara H, Koike T, Lopez R, Gibson T, Higgins DG, Thompson JD. Multiple sequence alignment with the Clustal series of programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3497–3500. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silberg JJ, Tapley TL, Hoff KG, Vickery LE. Regulation of the HscA ATPase Reaction Cycle by the Co-chaperone HscB and the Iron-Sulfur Cluster Assembly Protein IscU. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:53924–53931. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410117200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoff KG, Cupp-Vickery JR, Vickery LE. Contributions of the LPPVK Motif of the Iron-Sulfur Template Protein IscU to Interactions with the Hsc66-Hsc20 Chaperone System. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:37582–37589. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305292200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bax A. Weak alignment offers new NMR opportunities to study protein structure and dynamics. Protein Sci. 2003;12:1–16. doi: 10.1110/ps.0233303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kay LE, Torchia DA, Bax A. Backbone Dynamics of Proteins as Studied by 15N Inverse Detected Heteronuclear NMR Spectroscopy: Application to Staphylococcal Nuclease. Biochemistry. 1989;29:8972–8979. doi: 10.1021/bi00449a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mansy SS, Wu G, Surerus KK, Cowan JA. Iron-Sulfur Cluster Biosynthesiss—Thermotoga maritima IscU is a Structured Iron-Sulfur Cluster Assembly Protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:21397–21404. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201439200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ramelot TA, Cort JR, Goldsmith-Fischman S, Kornhaber GJ, Xiao R, Shastry R, Acton TB, Honig B, Montelione GT, Kennedy MA. Solution NMR Structure of the Iron-Sulfur Cluster Assembly Protein U (IscU) with Zinc Bound at the Active Site. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;344:567–583. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bertini I, Cowan JA, Del Bianco C, Luchinat C, Mansy SS. Thermotoga maritima IscU. Structural Characterization and Dynamics of a New Class of Metallochaperone. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;331:907–924. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00768-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vickery LE, Silberg JJ, Ta DT. Hsc66 and Hsc20, a new heat shock cognate molecular chaperone system from Escherichia coli. Protein Sci. 1997;6:1047–1056. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pellecchia M. Solution Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy Techniques for Probing Intermolecular Interactions. Chem. Biol. 2005;12:961–971. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huth JR, Olejniczak ET, Mendoza R, Liang H, Harris EAS, Lupher ML, Jr., Wilson AE, Fesik SW, Staunton DE. NMR and mutagenesis evidence for an I domain allosteric site that regulates lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 ligand binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:5231–5236. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.10.5231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sibille N, Sillen A, Leroy A, Wieruszeski J-M, Mulloy B, Landrieu I, Lippens G. Structural impact of heparin binding to full-length tau as studied by NMR spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 2006;45:12560–12572. doi: 10.1021/bi060964o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guharoy M, Chakrabarti P. Conservation and relative importance of residues across protein-protein interfaces. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:15447–15452. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505425102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Caffrey DR, Somaroo S, Hughes JD, Mintseris J, Huang ES. Are protein-protein interfaces more conserved in sequence than the rest of the protein surface? Protein Sci. 2004;13:190–202. doi: 10.1110/ps.03323604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jones S, Thornton JM. Principles of protein-protein interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:13–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bogan AA, Thorn KS. Anatomy of Hot Spots in Protein Interfaces. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;280:1–9. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.DeLano WL. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. 2002 World Wide Web http://www.pymol.org.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.