Abstract

Objectives

Most US studies of national trends in medical and nonmedical use of prescription opioids have focused on adults. Given this gap in understanding these trends among adolescents, we examine national trends in the medical and nonmedical use of prescription opioids among high school seniors between 1976 and 2015.

Methods

The data used for the study comes from the Monitoring the Future study of adolescents. Forty cohorts of nationally representative samples of high school seniors (modal age 18) were used to examine self-reported medical and nonmedical use of prescription opioids.

Results

Lifetime prevalence of medical use of prescription opioids peaked in both 1989 and in 2002, and remained stable until a recent decline from 2013 through 2015. Lifetime nonmedical use of prescription opioids was less prevalent and highly correlated with medical use of prescription opioids over this forty-year period. Adolescents who reported both medical and nonmedical use of prescription opioids tended to be more likely to indicate medical use of prescription opioids prior to initiating nonmedical use.

Conclusions

Prescription opioid exposure is common among US adolescents: long-term trends indicate that one-fourth of high school seniors self-reported medical or nonmedical use of prescription opioids. Medical and nonmedical use of prescription opioids has declined recently and remained highly correlated over the past four decades. Sociodemographic differences and risky patterns involving medical and nonmedical use of prescription opioids should be taken into consideration in clinical practice to improve opioid analgesic prescribing and reduce adverse consequences associated with prescription opioid use among adolescents.

INTRODUCTION

The US consumes the majority of the world’s prescription opioid supply and multiple studies have reported substantial increases in the prescribing of opioid analgesics.1–7 One consequence of an increase in the prescribing of opioids is a concomitant increase in opioid-related consequences such as nonmedical use, prescription opioid use disorders, emergency department admissions, and overdose deaths due to greater availability of these medications.1,3–12 These associations suggest that the trends in nonmedical use of prescription opioids (NUPO) should be considered within the larger context of medical availability of prescription opioids.

To date, studies examining national trends in medical use of prescription opioids and NUPO have focused primarily on adults and relied on separate data sources.1,3–7 Four studies have examined the association between medical use of prescription opioids and NUPO among adolescents and found that the majority of medical users reported no history of NUPO.10,13–15 In contrast, most adolescents who report NUPO have a history of medical use of prescription opioids.10,13–15 Despite the aforementioned studies aimed at determining the associations between medical use of prescription opioids and NUPO, there is a paucity of research using repeated national samples that assesses the long-term trends, correlations, and patterns of medical use of prescription opioids and NUPO among adolescents.16–19 Furthermore, previous studies have examined race and sex differences in medical use of prescription opioids, and generally found that female and white adolescents were more likely to be prescribed opioid analgesics than male and African-American adolescents, respectively.13,14,20,21 Unfortunately, these studies have often been limited by their regional focus at single points in time.

Given these gaps in knowledge, more national studies are needed to determine if there are long-term associations between changes in medical use of prescription opioids and NUPO among adolescents. Empirically demonstrating a long-term relationship between medical use and NUPO will be particularly helpful in refining recommendations for safely prescribing opioid medications among adolescents while reducing NUPO. Due to the lack of available data on the long-term trends among adolescents, the primary aim of this study was to assess the trends and correlations in the prevalence of medical use of prescription opioids and NUPO among US high school seniors from 1976 to 2015.

METHODS

The Monitoring the Future (MTF) study annually surveys a cross-sectional, nationally representative sample of US high school seniors attending approximately 135 public and private schools, using self-administered paper-and-pencil questionnaires in classrooms. This study considered samples of high school seniors from 40 independent cohorts (senior years 1976–2015), each recruited using a multistage random-sampling design. The response rates ranged from 77% to 86% between 1976 and 2015. Because so many questions are included in the MTF study, much of the questionnaire content is divided into six different forms, which are randomly distributed. This approach results in six identical subsamples. The measures most relevant for this study were asked on Form 1, so this study focuses on the cross-sectional subsamples receiving Form 1 within each of the 40 cohorts. Details about the MTF study design and methods are available elsewhere.22,23 The University of Michigan Institutional Review Board provided approval for this study.

Each of the 40 cohorts was an independent, cross-sectional, nationally representative sample of US high school seniors. The demographic characteristics of the population represented by these cohorts varied over time. MTF sampling weights were applied in all analyses to assure each sample was representative of all high school seniors in each cohort in terms of sex and race/ethnicity. The modal age in each cohort was 18 years old. The sample size per cohort ranged from 2,181 to 3,791.

Measures

The MTF study assesses a wide range of behaviors, attitudes, and values.22,23 We selected specific measures for analysis in the present study, including demographic characteristics (i.e., sex and race) and standard measures of substance use behaviors.

Medical use of prescription opioids was assessed by asking whether respondents had ever taken prescription opioids because a doctor told them to use the medication. Respondents were informed that prescription opioids are prescribed by doctors and sold in drugstores, and are not supposed to be sold without a prescription. These included: Vicodin®, OxyContin®, Percodan®, Percocet®, Demerol®, Ultram®, methadone, morphine, opium, and codeine. The response options included: (1) No; (2) Yes, but I had already tried them on my own; and (3) Yes, and it was the first time I took any. The range of missing data was 6.0% to 12.0% for medical use of prescription opioids.

Nonmedical use of prescription opioids (NUPO) was assessed by asking on how many occasions (if any) in their lifetime the adolescent used prescription opioids on their own, that is, “without a doctor telling you to take them.” The response options ranged from (1) no occasions to (7) 40 or more occasions. The range of missing data was 6.0% to 12.4% for NUPO. While the wording of the medical and nonmedical use questions remained identical across all 40 cohorts, the list of examples of prescription opioids was updated over time. In 2002, Talwin®, laudanum, and paregoric had negligible rates of use by 2001 and were replaced with Vicodin®, OxyContin®, and Percocet®, which likely contributed to an increase in medical and nonmedical use in 2002 and subsequent years. Changes in wording in long-term studies represent a challenge to tracking cross-sectional behavioral trends related to prescription opioids over time. It is noteworthy that identical wording changes were made to both medical and nonmedical use questions in the MTF study at the same time; in addition, similar updates were made to prescription opioid questions in other national studies.

Statistical Analysis

For each of the 40 cohorts, we first used the cohort-specific sampling weights to estimate the prevalence of lifetime medical use of prescription opioids and the prevalence of lifetime NUPO, both overall and for males and females separately. We also estimated the prevalence of medical use and NUPO for white and African-American adolescents. We used a methodology outlined previously to compute linearized estimates of standard errors for the weighted estimates reflecting the complex MTF sampling features.24 Next, for each cohort, we estimated the prevalence of the following four mutually exclusive subgroups: (1) lifetime medical use of prescription opioids only; (2) medical use of prescription opioids prior to NUPO; (3) NUPO prior to medical use of prescription opioids; and (4) NUPO only. We estimated the prevalence of these subgroups overall as well as for males and females in each cohort. Estimated prevalence for males and females within a given year was compared using the methodology for comparing descriptive parameters in two subgroups defined in prior work.25

Finally, given the weighted prevalence estimates and linearized standard errors for each of the 40 cohorts, we assessed the correlation of the estimated prevalence for medical use of prescription opioids and NUPO across the 40 cohorts using three different methods. First, we estimated a simple unweighted linear regression coefficient predicting estimated NUPO prevalence as a function of estimated medical use prevalence. Next, we fit the same model using variance-weighted least squares, using the estimated standard error of the nonmedical use prevalence to determine the weights. Finally, we computed a Pearson correlation coefficient describing the strength of the linear association between the two sets of prevalence estimates across the 40 cohorts. These three tests of association, designed to gauge the robustness of the associations, were repeated for subpopulations based on sex and race. All analyses were performed using the Stata software (Version 14.1).

RESULTS

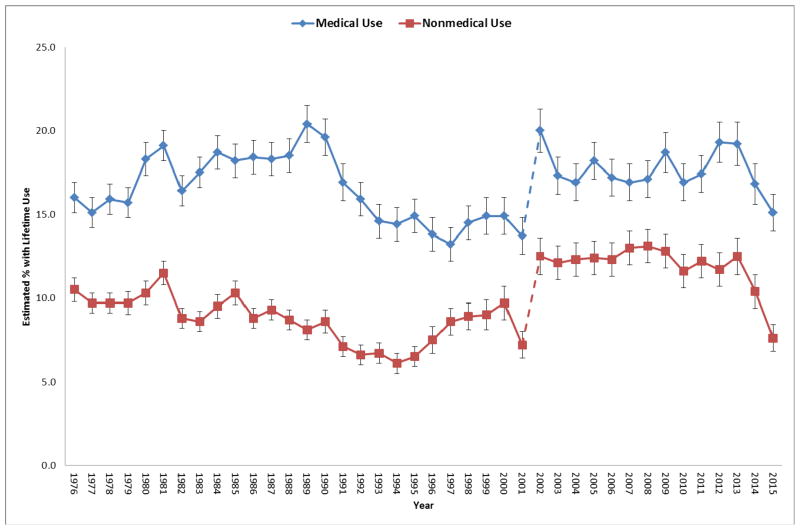

Lifetime medical use of prescription opioids was more prevalent than lifetime NUPO among high school seniors over the 1976 to 2015 time period (Figure 1). The estimated lifetime prevalence of medical use of prescription opioids increased from 16.0% (SE = 0.9) in 1976 to a peak of 20.4% (SE = 1.1) in 1989, gradually declined to a low of 13.2% (SE = 1.0) in 1997, held relatively stable until a rapid increase to 20.0% (SE = 1.3) in 2002 (partially influenced by a change in question wording; see the Measures section), and then remained relatively stable until a recent decline after 2013. The lifetime NUPO was correlated with medical use of prescription opioids over time, regardless of the test of association used; we report the Pearson correlation here (r = 0.50, P < 0.01). The estimated linear regression coefficients for medical use prevalence as a predictor of NUPO prevalence were 0.552 (ordinary least squares, P < 0.01) and 0.450 (variance-weighted least squares, P < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Trends in lifetime medical and nonmedical use of prescription opioids among high school seniors, 1976–2015

Notes: The dotted line reflects the fact that the list of examples of prescription opioids was updated in 2002, which likely contributed to an increase in medical and nonmedical use of prescription opioids in 2002 (see Measures for details of the updates).

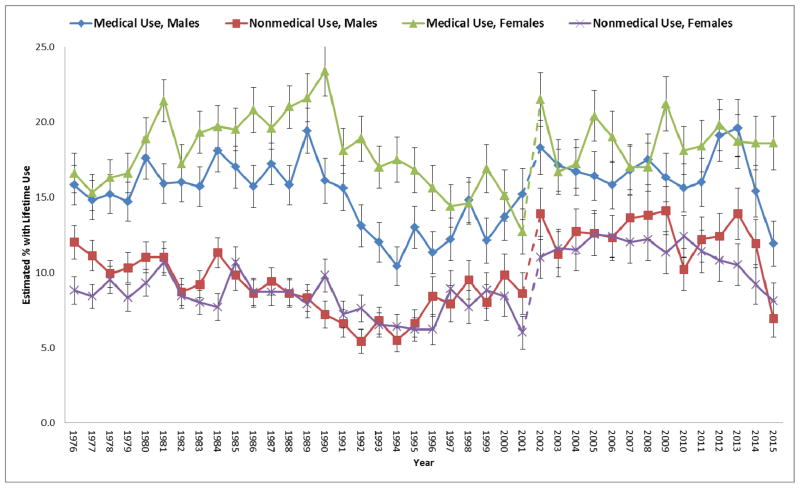

The lifetime medical use of prescription opioids tended to be more prevalent among female adolescents relative to male adolescents (Figure 2). In contrast, the prevalence of NUPO differed less by sex. The Pearson correlation between medical use of prescription opioids and NUPO was much stronger for males (r = 0.67, P < .001) than females (r = 0.34, P < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Trends in lifetime medical and nonmedical use of prescription opioids among high school seniors by sex, 1976–2015

Notes: The dotted line reflects the fact that the list of examples of prescription opioids was updated in 2002, which likely contributed to an increase in medical and nonmedical use of prescription opioids in 2002 (see Measures for details of the updates).

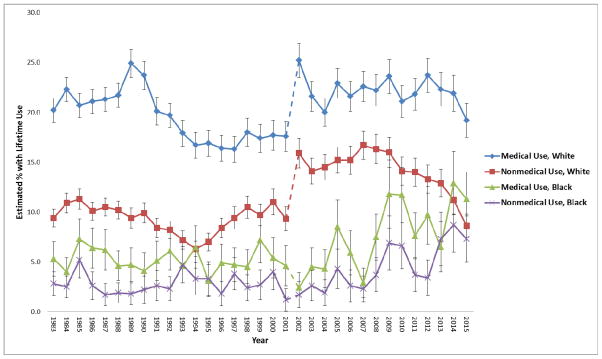

The prevalence of medical use of prescription opioids was consistently higher among White adolescents relative to African-American adolescents (Figure 3). Similarly, NUPO was more prevalent among White adolescents as compared to African-American adolescents. The Pearson correlation between medical use of prescription opioids and NUPO was robust for African-American (r = 0.79, P < 0.001) and White adolescents (r = 0.65, P < 0.001).

Figure 3.

Trends in lifetime medical and nonmedical use of prescription opioids among US high school seniors by race, 1983–2015

Notes: Based on changes in the response options to the race question between early cohort years (1976–1982) and more recent cohort years (1983–2015), we examined race trends starting in 1983 in order to have consistent race categories over time. The dotted line reflects the fact that the list of examples of prescription opioids was updated in 2002, which likely contributed to an increase in medical and nonmedical use of prescription opioids in 2002 (see Measures for details of the updates).

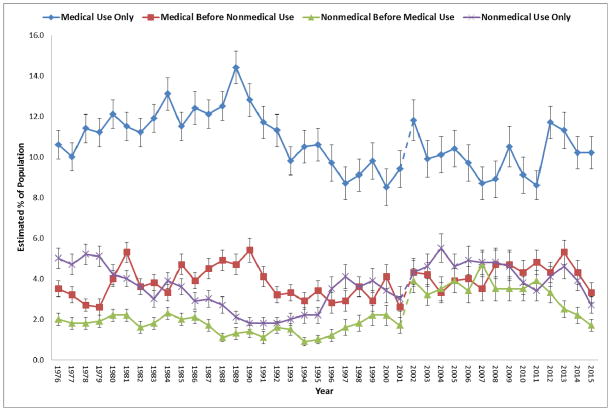

Next, we examined the long-term trends in patterns of lifetime medical and nonmedical use history for prescription opioids among high school seniors (Figure 4). We found that the most prevalent pattern of exposure to prescription opioids was medical use only (without a history of NUPO) over the course of the study period, ranging from a low of 8.5% (SE = 0.9) in 2000 to a high of 14.4% (SE = 0.8) in 1989. Among those who report a history of both medical use of prescription opioids and NUPO, the most prevalent pattern was generally medical use prior to initiating NUPO ranging from a low of 2.6% (SE = 0.2) in 1979 to a high of 5.4% (SE = 0.6) in 1990 while the least prevalent pattern tended to be NUPO prior to initiating medical use of prescription opioids. Finally, the prevalence of NUPO only has remained similar to medical use prior to initiating NUPO over the past decade.

Figure 4.

Trends in patterns of lifetime use history for prescription opioids among US high school seniors, 1976–2015

Notes: The dotted line reflects the fact that the list of examples of prescription opioids was updated in 2002, which likely contributed to an increase in medical and nonmedical use of prescription opioids in 2002 (see Measures for details of the updates).

Additional analyses indicated medical use only was more prevalent among females than males in 19 out of 40 years (P < 0.05), see supplemental Figure A. In contrast, NUPO only was more prevalent (P < 0.05) among males than females in 6 of the 40 years (see supplemental Figure B). There were fewer sex differences in NUPO prior to initiating medical use of prescription opioids, with males reporting higher prevalence rates than females in 4 of the 40 years (P < 0.05), see supplemental Figure A. Finally, there were the fewest sex differences in medical use of prescription opioids prior to engaging in NUPO, with females reporting higher prevalence rates than males in 2 of the 40 years (P < 0.05), see supplemental Figure A.

DISCUSSION

We found that the medical use of prescription opioids was highly correlated with NUPO among high school seniors between 1976 and 2015. The prevalence of lifetime medical use or NUPO ranged from 16.5% to 24.1% over the past four decades. The recent declines in medical use of prescription opioids and NUPO from 2013 through 2015 found in the present study coincide with similar recent declines in US opioid analgesic prescribing.7,26 While medical use of prescription opioids without any history of NUPO was the most prevalent exposure to prescription opioids between 1976 and 2015, we found that the majority of adolescents indicating NUPO also had a history of medical use of prescription opioids. Among adolescents who report both medical use of prescription opioids and NUPO, medical use prior to initiating NUPO tended to be most prevalent, and this pattern may be driven by the one-third of adolescents who report NUPO involving leftover opioid medications from their own previous prescriptions.22,27,28

The medical use of prescription opioids was generally more prevalent among females, while NUPO differed little by sex. While sex differences in medical use of prescription opioids have been documented,13,14,21,29 the present study extended prior research by examining long-term trends. The medical use of prescription opioids was found to be highly correlated with NUPO across the 40 cross-sectional samples among high school seniors, consistent with prior findings among adults.1,3–7 Notably, we found that the correlation was much stronger for males than females.

Based on past research, there are several possible reasons for why medical use of prescription opioids is more highly correlated with NUPO among adolescent males than females. First, NUPO is directly related to the availability of prescription opioids, and several prior studies have shown sex differences in the diversion associated with NUPO among adolescents.30–33 For instance, male nonmedical users are more likely to obtain prescription opioids from their peers while female nonmedical users are more likely to obtain prescription opioids from family members.31,32 The higher rate of peer-to-peer diversion among adolescent males may increase the risk of NUPO when medical availability increases.

Second, male nonmedical users are more likely to use prescription opioids nonmedically to get high whereas female nonmedical users are more likely to use for physical pain relief.20,32,34 The higher rate of non-pain relief motives among males could partially account for the stronger correlation between medical use of prescription opioids and NUPO. The findings of the present study reinforce the need that prevention and intervention efforts to reduce NUPO must take into account the reasons and diversion sources associated with NUPO among adolescents, especially among males.

Medical use of prescription opioids and NUPO were considerably more prevalent among White adolescents than among African-American adolescents. There are likely several reasons for these findings. First, previous work has documented health disparities for receiving prescription opioids among racial minority patients.35–37 For example, in a study that considered a sample of pharmacies in Michigan located in low-income zip codes, pharmacies in white zip codes (defined as ≥70% white residents) had odds of carrying sufficient opioid analgesics that were 54 times higher than the odds for pharmacies in racial minority zip codes (defined as ≥70% racial minority residents).35

Second, past studies have shown racial differences in the motives and diversion sources associated with NUPO.31,33,38 For instance, African-American adolescents were more likely than White adolescents to be motivated solely by pain relief.36 Thus, the lower prevalence of medical use of prescription opioids and NUPO among African-American relative to White adolescents could be due to lack of adequate treatment, insufficient availability, over-prescribing among White populations, and/or under-prescribing among non-White populations.

The present study indicates previous peaks in the medical use of prescription opioids and NUPO that preceded the current opioid crisis. There are several possible explanations for these different trends. Although NUPO for recreational reasons (e.g., to get high) was most prevalent in the late 1970’s and early 2000’s, NUPO to relieve pain was least prevalent during these two time periods while NUPO to reduce negative affect (e.g., relieve tension) rose to its highest level in the early 2000’s.34 The abuse potential of prescription opioids has changed over time, and this may play a role in the current opioid epidemic that deserves more attention.

The implications for clinical practice given this data and the current opioid epidemic are multiple: (1) use prescription drug monitoring programs to assist in identifying misuse as routine practice, (2) clinical decision making with adolescents and parents/guardians about risks and benefits of pain management with and without prescription opioids, including the importance of proper storage, monitoring and disposal of prescription opioids, (3) screening for NUPO, substance use disorders and other mental health disorders, (4) prescribing the lowest effective dose and the minimum quantity with concomitant use of acetaminophen or ibuprofen to decrease opioid requirement when not contraindicated, and (5) avoiding concurrent prescription of sedatives per the CDC best practice recommendations.39

The present study has some limitations that need to be taken into account when considering the implications of the findings. First, the MTF study is a long self-report survey and is subject to recall bias and respondent burden. Second, the MTF study did not assess age of onset, dose, duration, pain condition, or efficacy related to medical use of prescription opioids. Third, the MTF study does not assess some potential confounding variables in 12th grade such as opioid use disorders and family mental health history. Fourth, students who dropped out of school or were absent on the day of data collection did not participate in the study and these individuals are more likely to report substance use.22 Thus, individuals who experienced the most serious consequences associated with NUPO are likely underrepresented in the sample, resulting in underestimates and a need for comparable research among adolescents not enrolled in school. Finally, the results were based on 40 independent cross-sectional surveys which limited the ability to draw conclusions about causation. More prospective research is needed to examine the longitudinal associations between medical use of prescription opioids, NUPO, and opioid use disorders over the lifespan.

CONCLUSION

This study examined long-term trends in the relationships between the medical use of prescription opioids and NUPO using a large multi-cohort national study over the past four decades. The findings provide compelling evidence that medical use of prescription opioids and NUPO are highly correlated, especially among males. The recent declines in medical use of prescription opioids and NUPO from 2013 through 2015 found in the present study provide further evidence for the continuation of previous declines reported in opioid analgesic prescribing and NUPO but must be placed into larger context within the current opioid crisis.2,26,40 At least two studies have found recent increases in prescription opioid-related consequences such as prescription opioid use disorders, mortality and overdoses in the U.S. despite recent declines in NUPO.9,40 Sex and race differences in the medical availability of prescription opioids should be taken into consideration in clinical practice and efforts to provide adequate pain treatment and reduce NUPO.

We found that the majority of NUPO involved a history of medical use, and this finding should provide some concern to health professionals who prescribe opioid medications to adolescents given the serious health consequences associated with NUPO.8–12,37–40 The findings provide some valuable insights into different patterns of NUPO to target and evaluate for preventative interventions among adolescents with the ultimate goal of reducing prescription opioid misuse while improving the safety of pain management. Prescribing practices that enhance vigilance and monitoring of prescription opioids among adolescents, including education regarding proper disposal when medical use has concluded, warrant further investigation.

Supplementary Material

Trends in (1) medical use only and (2) medical use before nonmedical use of prescription opioids by sex, 1976–2015

Footnote to Supplemental Figure A: The dotted line reflects the fact that the list of examples of prescription opioids was updated in 2002, which likely contributed to an increase in medical and nonmedical use of prescription opioids in 2002 (see Measures for details of the updates).

Trends in lifetime (3) nonmedical use before medical use and (4) nonmedical use only of prescription opioids by sex, 1976–2015

Footnote to Supplemental Figure B: The dotted line reflects the fact that the list of examples of prescription opioids was updated in 2002, which likely contributed to an increase in medical and nonmedical use of prescription opioids in 2002 (see Measures for details of the updates).

What’s Known on This Subject

Opioid analgesic prescribing has increased in the US over the past four decades. To date, studies examining national trends in medical and nonmedical use of prescription opioids have focused primarily on adults and relied on separate data sources.

What This Study Adds

Lifetime medical and nonmedical use of prescription opioids was highly correlated among adolescents over the past four decades, especially among males. Adolescents reporting both medical and nonmedical use of prescription opioids were more likely to initiate medical before nonmedical use.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: The development of this article was supported by research grants R01DA031160 and R01DA036541 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- MTF

Monitoring the Future

- US

United States

- NUPO

Nonmedical Use of Prescription Opioids

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Contributors Statement:

Sean Esteban McCabe: Dr. McCabe conceptualized and designed the study, drafted the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Brady T. West: Dr. West carried out the analyses, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Phil Veliz: Dr. Veliz interpreted data, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Sarah Stoddard: Dr. Stoddard interpreted data, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Carol J. Boyd: Dr. Boyd conceptualized the study, critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Vita V. McCabe: Dr. McCabe interpreted data, critically reviewed the manuscript with a focus on the significance of the study for clinical practice, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

References

- 1.Atluri S, Sudarshan G, Manchikanti L. Assessment of the trends in medical use and misuse of opioid analgesics from 2004 to 2011. Pain Physician. 2014;17:119–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dart RC, Surratt HL, Cicero TJ, Parrino MW, Severstson SG, Bucher-Bartelson B, Green JL. Trends in opioid analgesic abuse and mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:241–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1406143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fortuna RJ, Robbins BW, Caiola E, Joynt M, Halterman JS. Prescribing of controlled medications to adolescents and young adults in the United States. Pediatrics. 2010;126:1108–16. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joranson DE, Ryan KM, Gilson AM, Dahl JL. Trends in medical use and abuse of opioid analgesics. JAMA. 2000;283:1710–14. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.13.1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manchikanti L, Fellows B, Ailinani H, Pampati V. Therapeutic use, abuse, and nonmedical use of prescription opioids: a ten-year perspective. Pain Physician. 2010;13:401–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Novack S, Nemeth WC, Lawson KA. Trends in medical use and abuse of sustained-release opioid analgesics: a revisit. Pain Med. 2004;5:59–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2004.04001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zacny J, Bigelow G, Compton P, Foley K, Iguchi M, Sannerud C. College on Problems of Drug Dependence taskforce on prescription opioid non-medical use and abuse: position statement. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;69:215–32. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bohnert AS, Valenstein M, Bair MJ, Ganoczy D, McCarthy JF, Ilgen MA, Blow FC. Association between opioid prescribing patterns and opioid overdose-related deaths. JAMA. 2011;305:1315–21. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han B, Compton WM, Jones CM, Cai R. Nonmedical prescription opioid use and use disorders among adults aged 18 through 64 in the United States, 2003–2013. JAMA. 2015;314:1468–78. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.11859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCabe SE, Veliz P, Schulenberg JE. Adolescent context of exposure to prescription opioids and substance use disorder symptoms at age 35: A national longitudinal study. Pain. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000624. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miech R, Johnston L, O’Malley PM, Keyes KM, Heard K. Prescription opioids in adolescence and future opioid misuse. Pediatrics. 2015;136:e1169–77. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saha TD, Kerridge BT, Goldstein RB, et al. Nonmedical prescription opioid use and DSM-5 nonmedical prescription opioid use disorder in the United States. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77:772–80. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15m10386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyd CJ, McCabe SE, Teter CJ. Medical and nonmedical use of prescription pain medication by youth in a Detroit-area public school district. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;81:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCabe SE, Boyd CJ, Young A. Medical and nonmedical use of prescription drugs among secondary school students. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCabe SE, West BT, Teter CJ, Boyd CJ. Medical and nonmedical use of prescription opioids among high school seniors in the United States. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166:797–802. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Compton WM, Volkow ND. Abuse of prescription drugs and the risk of addiction. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;83(Suppl 1):4–7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Compton WM, Volkow ND. Major increases in opioid analgesic abuse in the United States: concerns and strategies. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;81:103–7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nargiso JE, Ballard EL, Skeer MR. A systematic review of risk and protective factors associated with nonmedical use of prescription drugs among youth in the United States: a social ecological perspective. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2015;76:5–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Young AM, Glover N, Havens JR. Nonmedical use of prescription medications among adolescents in the United States: a systematic review. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51:6–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCabe SE, West BT, Boyd CJ. Medical use, medical misuse, and nonmedical use of prescription opioids: Results from a longitudinal study. Pain. 2013;154(5):708–713. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roe CM, McNamara AM, Motheral BR. Gender- and age-related prescription drug use patterns. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36:30–9. doi: 10.1345/aph.1A113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miech RA, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2015. Volume I: Secondary School Students. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Institute for Social Research; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnston LD, Bachman JG, O’Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Miech RA. Monitoring the Future: A Continuing Study of American Youth (12th-Grade Survey), 2015. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor]; 2016. Oct 25, ICPSR36408-v1. http://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR36408.v1. [Google Scholar]

- 24.West BT, McCabe SE. Incorporating complex sample design effects when only final survey weights are available. Stata. 2012;12:718–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heeringa SG, West BT, Berglund PA. Applied Survey Data Analysis. London: Chapman and Hall; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones CM, Lurie PG, Throckmorton DC. Effect of US Drug Enforcement Administration’s rescheduling of hydrocodone combination analgesic products on opioid analgesic prescribing. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2016;176:399–402. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCabe SE, West BT, Boyd CJ. Leftover prescription opioids and non-medical use among U.S. high school seniors: a multi-cohort national study. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:480–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simoni-Wastila L. The use of abusable prescription drugs: the role of gender. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2000;9:289–97. doi: 10.1089/152460900318470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Daniel KL, Honein MA, Moore CA. Sharing prescription medication among teenage girls: potential danger to unplanned/undiagnosed pregnancies. Pediatrics. 2003;111:1167–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCabe SE, Boyd CJ. Sources of prescription drugs for illicit use. Addict Behav. 2005;30:1342–50. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCabe SE, Cranford JA, Boyd CJ, Teter CJ. Motives, diversion and routes of administration associated with nonmedical use of prescription opioids. Addict Behav. 2007;32:562–75. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schepis TS, Krishnan-Sarin S. Sources of prescriptions for misuse by adolescents: differences in sex, ethnicity, and severity of misuse in a population-based study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:828–36. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181a8130d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Terry-McElrath YM, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. Reasons for drug use among American youth by consumption level, gender, and race/ethnicity: 1976–2005. J Drug Issues. 2009;39:677–714. doi: 10.1177/002204260903900310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Green CR, Ndao-Brumblay SK, West B, Washington T. Differences in prescription opioids analgesic availability: comparing minority and white pharmacies across Michigan. J Pain. 2005;6:689–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pletcher MJ, Kertesz SG, Kohn MA, Gonzales R. Trends in opioid prescribing by race/ethnicity for patients seeking care in US emergency departments. JAMA. 2008;299:70–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2007.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simon LJ, Bizamcer AN, Lidz CW, Stefan S, Pletcher MJ. Disparities in opioid prescribing for patients with psychiatric diagnoses presenting with pain to the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2012;29:201–204. doi: 10.1136/emj.2010.097949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCabe SE, West BT, Boyd Motives for medical misuse of prescription opioids among adolescents. J Pain. 2013;14:1208–1216. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Opioid painkiller prescribing. CDC VitalSigns. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/opioid-prescribing/index.html.

- 40.Compton WM, Jones CM, Baldwin GT. Relationship between nonmedical prescription-opioid use and heroin use. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:154–163. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1508490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trends in (1) medical use only and (2) medical use before nonmedical use of prescription opioids by sex, 1976–2015

Footnote to Supplemental Figure A: The dotted line reflects the fact that the list of examples of prescription opioids was updated in 2002, which likely contributed to an increase in medical and nonmedical use of prescription opioids in 2002 (see Measures for details of the updates).

Trends in lifetime (3) nonmedical use before medical use and (4) nonmedical use only of prescription opioids by sex, 1976–2015

Footnote to Supplemental Figure B: The dotted line reflects the fact that the list of examples of prescription opioids was updated in 2002, which likely contributed to an increase in medical and nonmedical use of prescription opioids in 2002 (see Measures for details of the updates).