Abstract

Aim

Transient outward potassium current (Ito) is thought to be central to the activator has not been pathogenesis of the Brugada syndrome (BrS). However, an Ito available with which to validate this hypothesis. Here we provide a direct test of the hypothesis using a novel Ito activator, NS5806.

Methods

Isolated canine ventricular myocytes and coronary-perfused wedge preparations were used.

Results

Whole-cell patch-clamp studies showed that NS5806 (10 μM) increased peak Ito at +40 mV by 79±4% (24.5±2.2 to 43.6±3.4 pA/pF, n=7) and slowed the time-constant increased of inactivation from 12.6±3.2 to 20.3±2.9 ms, n=7. Total charge carried by Ito by 186% (from 363.9 ± 40.0 to 1042.0 ± 103.5 pA ms/pF, n=7). In ventricular wedge preparations, NS5806 increased phase 1 and notch amplitude of the action potential (AP) in epicardium, but not endocardium, and accentuated the ECG J-wave, leading to the development of phase 2 reentry and polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (n=9). While sodium and calcium channel blockers are capable of inducing BrS only in right ventricular wedge preparations, the Ito activator was able to induce the phenotype in wedges from both ventricles. NS5806 induced BrS in 4/6 right and 2/10 left ventricular wedge preparations.

Conclusions

The Ito activator NS5806 recapitulates the electrographic and arrhythmic manifestation of BrS, providing evidence in support of its pivotal role in the genesis of the disease. Our findings also suggest that a genetic defect leading to a gain of function of Ito could explain variants of BrS in which ST-segment elevation or J-waves are evident in both right and left ECG leads.

Introduction

Brugada syndrome (BrS) is an inherited disease associated with phase 2 reentry, polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (PVT) and sudden cardiac death in young adults with a structurally normal heart. The ECG pattern of BrS is often concealed but can be unmasked or modulated by fever, vagal stimulation and a number of pharmacological agents1. BrS has been linked to decreased inward currents or increased outward currents during phase 1 accentuating the spike-and-dome morphology of the AP mainly in the epicardium1. The transmural voltage gradient that develops gives rise to the characteristic ECG changes consisting of a down-sloping ST-segment elevation or accentuated J-wave with a negative T-wave. In most cases, these ECG changes manifest principally in the right precordial leads2, although BrS cases of left precordial and inferior lead ST segment elevation have been reported3–5. ST segment elevation is often accompanied by QT prolongation in the right precordial leads, due to accentuation of the epicardial action potential notch6.

On a molecular level, BrS has been linked to mutations in the SCN5A gene7 encoding the Nav1.5 channel α-subunit, in SCN1B8 encoding the sodium channel β1-subunit, in the glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase 1 like gene (GPD1-L)9 as well as in mutations in the CACNA1c and CACNB2b genes6 encoding the α1 and β2b subunits of the L-type calcium channel, respectively. Mutations in SCN5A, SCN1B and GPD1-L all reduced peak sodium channel current (INa), whereas mutations in CACNA1c and CACNB2b lead to a decrease in L-type calcium channel current. More recently, a mutation in the KCNE3 gene resulting in increased Ito current has been associated with BrS10. Although a direct link to Ito has only recently been established, Ito has long been thought to be central to the pathogenesis of BrS1. The presence of a prominent Ito predisposes the myocardium to the development of a BrS phenotype by amplifying phase 1 of the action potential (AP), thus leading to augmentation of the notched appearance of the AP, most notably in the right ventricular epicardium. Ito is larger in the right ventricle (RV) than in the left (LV)11, accounting for the appearance of ST segment elevation in the right precordial leads. Furthermore, BrS is more prevalent in males than in females, due at least in part to the presence of a more prominent Ito in RV of males12.

The present study examines the characteristics of a novel and unique Ito activator, NS5806, in isolated canine ventricular myocytes and wedge preparations. NS5806 is shown to recapitulate the electrocardiographic and arrhythmic manifestations of BrS, providing further evidence in support of its pivotal role in the genesis of the disease. Our findings also suggest that a genetic defect leading to a prominent gain of function of Ito could explain variants of BrS in which ST-segment elevation or J-waves are evident in both right and left ECG leads.

Methods

NS5806

NS5806 was synthesized at NeuroSearch A/S, Ballerup, Denmark by reaction of 6-cyano-2,4-dibromoaniline with sodium azide to form the respective 2,4-dibromo-6-tetrazolylaniline, which was condensed with 3,5-bis-trifluoromethyl-phenylisocyanate to provide the target 1-[2,4-dibromo-6-(1H-tetrazol-5-yl)-phenyl]-3-(3,5-bis-trifluoromethyl-phenyl)-urea (NS5806). NS5806 was dissolved in DMSO (20 mM stock).

Experimental animals

This investigation conforms to the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institutes of Health (NIH publication No 85–23, Revised 1996). Adult mongrel dogs of either sex were anticoagulated with heparin and anesthetized with pentobarbital (30–35mg/kg, i.v.). Their hearts were rapidly removed and placed in a 4°C cardioplegic solution (in mM): NaCl 129, KCl 12, NaH2PO4 0.9, NaHCO3 20, CaCl2 1.8, MgSO4 0.5, glucose 5.5.

Isolation of adult canine cardiomyocytes

Myocytes from the midmyocardial (mid) region were prepared from canine hearts using techniques previously described13; 14. A wedge consisting of the left ventricular free wall supplied by a descending branch of the circumflex artery was excised, cannulated and perfused with nominally Ca2+-free solution (mM): NaCl 129, KCl 5.4, MgSO4 2.0, NaH2PO4 0.9, glucose 5.5, NaHCO3 20, bubbled with 95% O2/5% CO2 containing 0.1% BSA for a period of about 5 minutes. The wedge preparation was then subjected to enzyme digestion with the nominally Ca2+-free solution supplemented with 0.5 mg/ml collagenase (Type II, Worthington), 0.1 mg/ml protease (Type XIV, Sigma) and 1 mg/ml BSA for 8–12 minutes. After perfusion, thin slices of tissue from the mid region (about 5–7 mm from the epicardial surface) were shaved from the wedge using a dermatome. The tissue slices were then placed in separate beakers minced and incubated in fresh buffer containing 0.5 mg/ml collagenase, 1 mg/ml BSA and agitated. The supernatant was filtered, centrifuged at 200 rpm for 2 minutes and the myocyte containing pellet was stored in 0.5 mM Ca2+ HEPES buffer at room temperature.

Voltage Clamp Recordings

Voltage-clamp and current-clamp recordings were made using a MultiClamp 700A amplifier and MultiClamp Commander (Axon Instruments). Patch pipettes were fabricated from borosilicate glass capillaries (1.5 mm O.D., Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) using a gravity puller (Model PP-830, Narishige, Tokyo, Japan) and the pipette resistance ranged from 1–3 MΩ. Cell capacitance was measured by applying -5 mV voltage steps. Electronic compensation of series resistance to 60–70% was applied to minimize voltage errors. All analog signals (cell current and voltage) were acquired at 10–50 kHz, filtered at 4–6 kHz, digitized with a Digidata 1322 converter (Axon Instruments) and stored using pClamp9 software.

Ito recordings were performed as previously described15. Initially the ventricular cells were superfused with a HEPES buffer of the following composition (mM): NaCl 126, KCl 5.4, MgCl2 1.0, CaCl2 2.0, HEPES 10, glucose 11, pH 7.4. The patch pipette solution had the following composition (mM): K-aspartate 90, KCl 30, glucose 5.5, MgCl2 1.0, EGTA 5, MgATP 5, HEPES 5, NaCl 10, pH 7.2. The APs were recorded in this solution. For Ito, IK1 and IKr measurements the HEPES buffer was supplemented with 300 μM cadmium to block ICa and for IKr measurements 100 nM HMR1556 was present to block IKs. For ICaL measurements, 5 mM TEA was added to the pipette solution to block potassium currents and cadmium was not added to the HEPES buffer.

Sodium currents were recorded as previously described16 in a low Na+ extracellular solution (mM): CaCl2 0.5, Glucose 10, MgCl2 1.5, Choline-Cl 120, NaCl 5, HEPES 10, KCl 4, Na acetate 2.8, CoCl2 1, BaCl2 0.1, pH = 7.4. The pipette solution consisted of: MgCl2 1, NaCl 15, KCl 5, CsF 120, HEPES 10, EGTA 10, Na2ATP 4, pH 7.2. All experiments were performed at 37° C except for the sodium current recordings which were performed at room temperature.

Wedge preparations of the free wall from right and left ventricles

Transmural wedges were dissected from the base of the right (RV, 2 × 1.5 × 0.9 cm) and left ventricles (LV, 3 × 2 × 1.5 cm). The preparations were initially arterially perfused with cardioplegic solution. Subsequently, the wedge preparations were placed in a tissue bath and perfused with Tyrode’s solution (mM): NaCl 129, KCl 4, NaH2PO4 0.9, NaHCO3 20, CaCl2 1.8, MgSO4 0.5, glucose 5.5, pH7.4 and bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 (37 ± 0.5°C). The perfusate was delivered at a constant flow at 8–11 ml/min depending on the size of the wedge and the pressure was monitored throughout the experiment (Table 1). Pacing stimuli was delivered to the endocardial surface at 2 x the diastolic threshold of excitation (DTE). In all experiments recordings were made at a basic cycle length (BCL) of 300, 500, 800 and 2000. Unless otherwise indicated recordings at 2000 ms BCL are shown. The DTE was not affected by NS5806 (Table 1). Recordings were obtained after > 1 hour after mounting for control and 30 min after application of NS5806. A transmural pseudo-ECG (ECG) was recorded using two Ag/AgCl half cells placed at ~1 cm from the epicardial (+) and endocardial (−) surfaces of the preparation. Intracellular recordings were obtained simultaneously from the subendocardium (endo, approx. 2–3 mm from the endocardial surface) and from the subepicardium (epi, approx 0–3 mm from the epicardial surface) using floating glass microelectrodes. ECG and AP signals were amplified and/or digitized and analyzed using Spike 2 for Windows (Cambridge Electronic Design [CED], Cambridge, UK).

Table 1.

Basic parameters measured in canine ventricular wedge preparations. All parameters were measured at a BCL of 2000 ms. The conduction time was calculated as time between the mid-point of phase 0 in epicardium and endocardium. The diastolic threshold of excitation (DTE) was determined by increasing the injected current until capture. The refractory period (ERP) was measured by delivering premature stimuli at progressively shorter S1–S2 intervals after every 10th basic beat applied at a BCL of 2000 ms and at 1.5 x DTE. The flow was kept constant between 8–11 ml/min and the pressure was measured.

| NS5806 (μM) | LV Transmural Conduction time (ms) | RV Transmural Conduction time (ms) | ERP RV and LV (ms) | DTE RV and LV (mA) | Pressure (dia) RV (mmHg) | Pressure (sys) RV (mmHg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 15.0±1.6, n=8 | 13.7±2.0, n=8 | 196.7±6.5, n=12 | 0.81±0.08, n=12 | 49.1±10.9, n=6 | 58.2±12.1, n=6 |

| 5 | 15.3±1.6, n=7 | 12.1±2.8, n=6 | 198.9±8.41, n=9 | 0.96±0.13, n=9 | 45.7±14.5, n=3 | 53.5±15.9, n=3 |

| 10 | 13.0±1.6, n=5 | 14.5±1.6, n=7 | 218.3±11.9, n=6 | 0.84±0.12, n=7 | 62.8±14.8, n=6 | 70.4±15.7, n=6 |

| 15 | 22.1±2.2, n=5 | 14.0±3.7, n=4 | - | - | - | - |

|

| ||||||

| * At 15 μM | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | |

Statistical Analysis

Results are presented as Mean ± SEM throughout the publication. Statistical comparisons were made using One way ANOVA and Dunnet’s post test, unless otherwise indicated.

Results

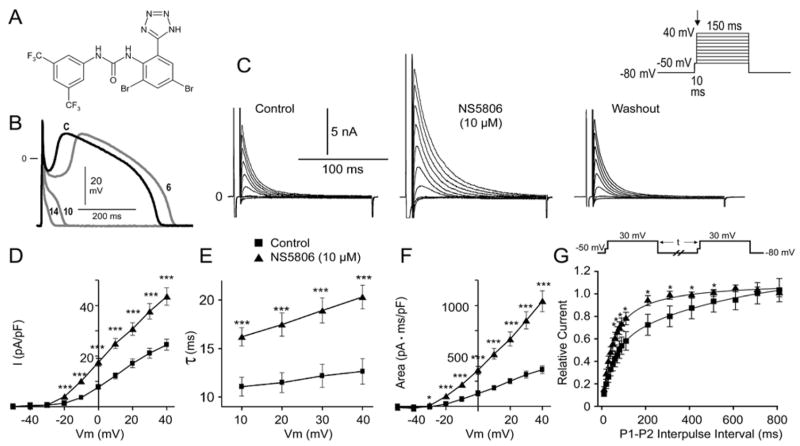

The molecular structure of NS5806 is shown in Fig. 1A. Figs. 1B–F illustrate the effect of NS5806 on APs and Ito recorded from myocytes isolated from the mid region of the canine left ventricle. At a cycle length of 1 s, the AP recorded under control conditions exhibited a prominent phase 1 repolarization resulting in a spike-and-dome morphology. Application of 10 μM NS5806 increased phase 1 leading to loss of the AP dome when phase 1 reached potentials more negative than the threshold for activation of the L-type calcium current, ICaL, (Fig. 1B). Loss of the dome was accompanied by a significant abbreviation of the APD90, from 372±29.4 ms to 51.3±18.7 ms (n=5, p<0.05). NS5806 (10 μM) reduced the maximal upstroke velocity of phase 0 (Vmax) by 9.8±3.4 % (from 407.2±34.4 to 367.0±32.7 V/s, n=5, p<0.05); the amplitude of phase 0 was unaffected (121.6±1.1 mV in control vs.120.3±0.25 mV with NS5806, n=5). The concentration of NS5806 was based on preliminary experiments in CHO-K1 cells expressing Kv4.3 and KChiP2, were we found an EC50 value of 7 μM.

Figure 1.

A) Chemical structure of the diphenylurea 1-(3,5-Bis-trifluoromethyl-phenyl)-3-[2,4-dibromo-6-(1H-tetrazol-5-yl)-phenyl]-urea compound, NS5806. B) Action potentials recorded from a canine left ventricular (LV) midmyocardial myocyte before (black) and at 6, 10 and 14 s after 10 μM NS5806 (grey). Basic cycle length (BCL) = 1 s. Representative of n=5. C) Representative Ito currents recorded from isolated LV midmyocardial myocytes in the absence and presence of 10 μM NS5806, n=7. D) Current-voltage (I–V) relation of peak Ito before and after 10 μM NS5806. E) Time constant of decay of Ito before and after 10 μM NS5806. F) Graph showing area under the curve, reflecting the total charge carried by Ito. G) Ito recovery from inactivation using a two pulse protocol. Statistical significance was evaluated by paired t-test.

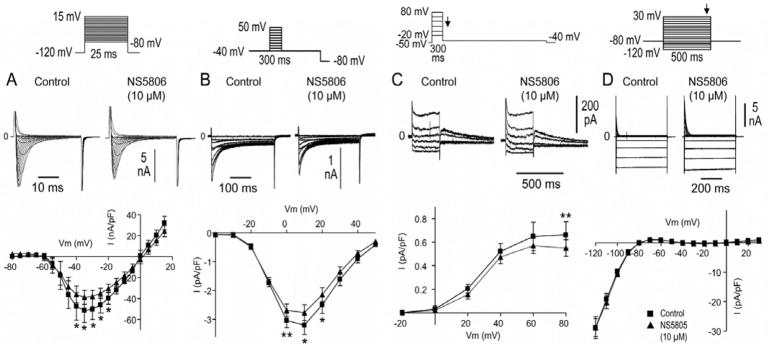

The effect on the phase 1 repolarization suggested that Ito currents were increased by NS5806. As a test of this hypothesis, we recorded Ito in midmyocardial cells using whole-cell patch-clamp techniques (Fig. 1C–G). NS5806 (10 μM) significantly increased the magnitude of Ito at all potentials greater than −30 mV (Fig. 1D). Inactivation was significantly slowed, as reflected by an increase in time constant (τ, from 12.6±3.2 ms to 20.3±2.9 ms at +40 mV, n=7 p<0.05; Fig. 1E). The increased Ito peak-current amplitude together with the slowed inactivation resulted in a near 3-fold increase in total charge as reflected by an increase in area under the curve from 363.9±40.0 to 1042.0±103.5 pA ms/pF at +40 mV (n=7, p<0.05; Fig. 1F). The effects of the drug were fully reversed upon washout. Furthermore, the recovery from inactivation of the Ito current was faster in the presence of NS5806 (10 μM) as shown in Fig. 1G. We also examined the effect of NS5806 on other currents known to contribute to the development of the BrS phenotype. NS5806 (10 μM) caused a minor reduction in both INa and ICaL as shown in Figs. 2A and B. As it has recently been suggested that the fast component of the delayed rectifier current, IKr, can contribute to BrS in humans17 and an IKr agonist that modulates ERG channels resulting in Ito-like currents has been reported18 we assessed the effect of NS5806 on IKr in isolated endocardial myocytes. Endocardial cells were chosen to minimize the impact of the Ito currents. We found that NS5806 (10 μM) caused a minor reduction in IKr as shown in Fig. 2C. We found no effect of NS5806 on IK1 currents (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

Effect of NS5806 on INa and ICaL currents recorded for isolated canine left ventricular (LV) midmyocardial cells and on IKr in endocardial LV myocytes. A) Representative INa traces and average I–V relation recorded before and after 10 μM NS5806 (n=4). B) ICaL currents were elicited by the shown protocol preceded by 5 pre-pulses (from −80 mV to +20 mV for 200 ms) to ensure constant load of the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Representative ICaL traces and average I-V relations recorded before and after 10 μM NS5806 (n=6). C) Representative IKr currents and IKr tail currents measured at −35 mV as a function of voltage at the preceding voltage-step before and after application of 10 μM NS5806 (n=7). D) Representative IK1 recordings in midmyocardial cells (n=8) and the current-voltage relationship at the end of the step protocol before and after application of 10 μM NS5806. Statistical significance was evaluated by paired t-test.

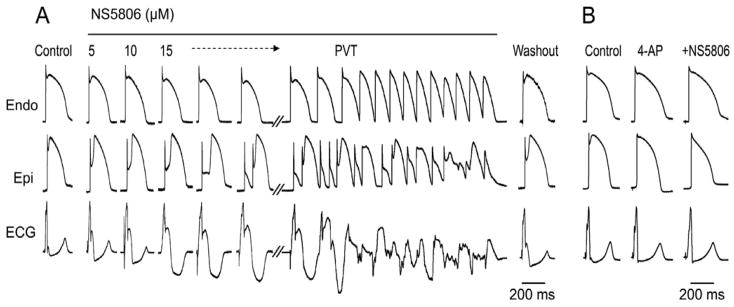

We next assessed the effect of increased Ito on the development of a BrS phenotype using canine ventricular wedge preparations. Fig. 3A shows a representative example of the effect of NS5806 (5–15 μM) in a RV wedge preparation. Increasing the concentration of NS5806 caused a progressive increase the epicardial phase 1 magnitude, whereas the APs of endocardial cells were largely unaffected. The increase in the epicardial notch magnitude was accompanied by an accentuation of the J-wave, or an apparent ST-segment elevation, on the ECG. The attending delay in epicardial repolarization led to reversal of the direction of repolarization and a progressive inversion of the T-wave corresponding to the type 1 BrS ECG. At a concentration of 15 μM, NS5806 increased phase 1 causing loss of the AP dome at some epicardial sites. The spike-and-dome AP morphology was maintained at other epicardial sites resulting in an epicardial dispersion of repolarization (EDR). Conduction of the AP dome from sites at which it was maintained to sites at which it was lost caused local re-excitation via a phase 2 reentry mechanism, leading to the development of closely coupled extrasystoles. The loss of the dome in the epicardium also created a transmural dispersion of repolarization (TDR) and refractoriness. The combination of EDR and TDR created a vulnerable window within the RV preparation that when captured by a closely coupled extrasystole induced self-terminating runs of rapid PVT. These runs of PVT often deteriorated to ventricular fibrillation. Washout of the drug terminated the arrhythmia and restored AP towards control. We next investigated the effect of NS5806 in the presence of the Ito inhibitor, 4-aminopyrodine (4-AP) as shown in Fig. 3B. Application of 4-AP (2 mM) abolished the epicardial notch and in the continued presence of 4-AP, NS5806 (10 μM) failed to enhance the epicardial notch and the J-wave on the ECG. In the presence of 4-AP and NS5806, there appeared to be some change in phase 2, which may be due to an effect on ICaL (Fig. 2B). The arrhythmias could also be terminated by introducing (4-AP) (2 mM) in the continued presence of 15 μM NS5806 (n=4, data not shown).

Figure 3.

Effect of NS5806 to induce the electrocardiographic and arrhythmic manifestation of Brugada syndrome in a canine right ventricular wedge preparation paced from the endocardial surface at a BCL of 2 s. A) Endo-and epicardium action potentials and ECG were recorded before and after 5, 10 and 15 μM NS5806, as well as after 30 min of washout. 15 μM NS5806 induce polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (PVT). Representative of n=4. B) 2 mM 4-aminopyrodine (4-AP) blocked Ito and prevented 10 μM NS5806 from increasing the epicardial notch in a left ventricular wedge. Representative of n=4.

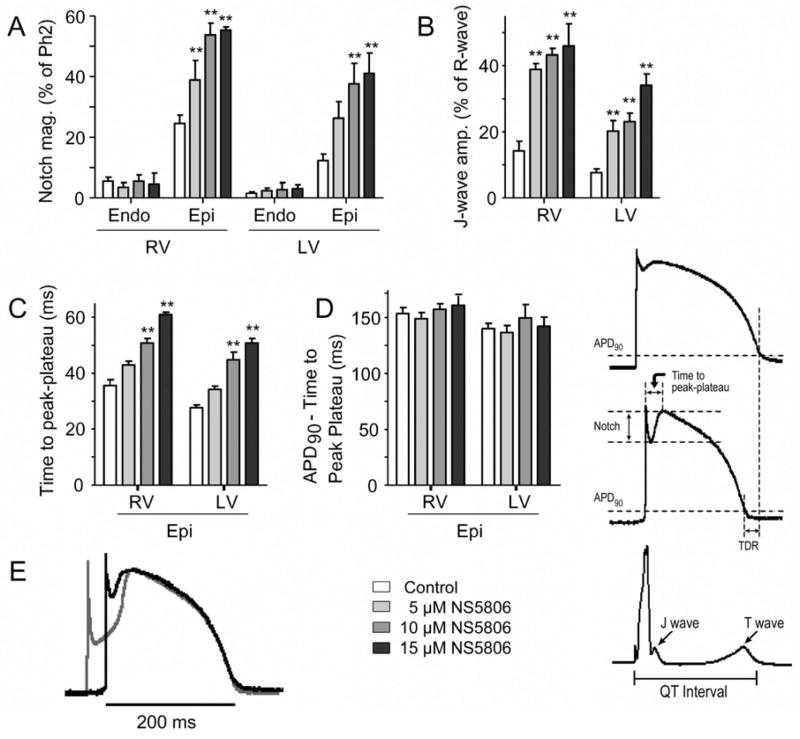

The effects of NS5806 on notch magnitude and J-wave amplitude on both left (LV) and right ventricular (RV) wedges are summarized in Figs. 4A and B. In both RV and LV preparations there was a concentration-dependent increase in the size of the epicardial notch, whereas the endocardium was largely unaffected. In addition to the effect on the notch, the time from onset of the epicardial AP to the peak of phase 2 (the time to peak-plateau), was significantly augmented by increasing concentrations of NS5806 (Fig. 4C) whereas the repolarization time (APD90 minus the time to peak-plateau) remained constant (Fig. 4D). Superimposed traces recorded from the epicardium in the absence and presence of NS5806 illustrate that the drug effect was mainly on notch magnitude and time to peak-plateau whereas the time and morphology of the repolarization phase were largely unaltered (Fig. 4E).

Figure 4.

Effect of NS5806 on action potential (AP) parameters recorded from canine right (RV) and left (LV) wedge preparations paced at a BCL of 2 s. Composite data of the effect of NS5806 (0–15 μM) on: A) AP notch magnitude as % of the phase 2 amplitude. B) J-wave amplitude as % of R-wave amplitude. C) Time to peak-plateau in epicardial APs D) Repolarization time measured as action potential duration (APD90) minus time to peak-plateau. E) Superimposed LV epicardial APs recorded in control (black trace) and after 15 μM NS5806 (grey trace). The APs were superimposed at the time of peak of phase 2. n=5–8.

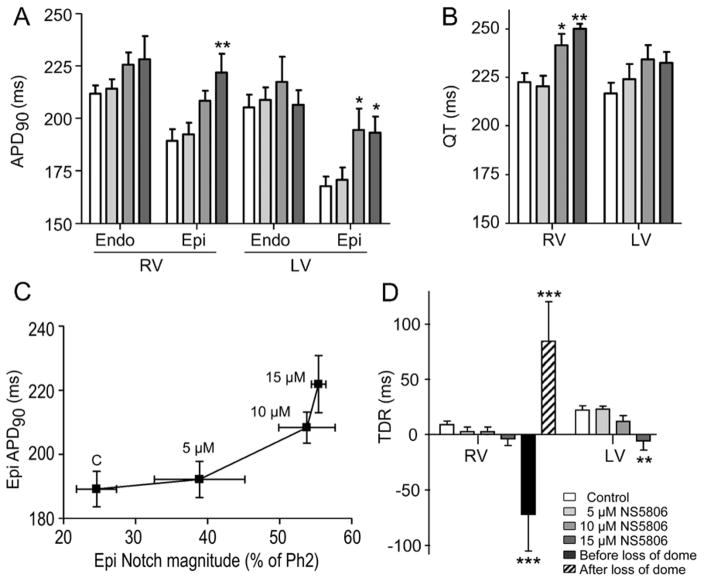

NS5806 prolonged epicardial APD90 and QT interval in both LV and RV preparations (Figs. 5A and B). Fig. 5C shows the inter-dependence of APD90 and notch amplitude in epicardium following exposure to increasing concentrations of NS5806. The prolongation of the APD90 was significant only in epicardium, where repolarization was delayed more than in endocardium. Fig. 5D presents a plot of TDR under the various conditions tested. TDR was greatest just before and after loss of the epicardial AP dome. The effective refractory period increased in proportion to the increase in APD90 (Table 1).

Figure 5.

Effect of NS5806 (0 to 15 μM) on action potential duration (APD90), QT interval, and transmural dispersion of repolarization (TDR) in canine right (RV) and left (LV) ventricular wedge preparations. BCL = 2 s. A) APD90; B) QT interval; C) Epicardial ADP90 plotted as a function of epicardial notch magnitude. D) TDR calculated as the time interval between repolarization of the endocardial and epicardial action potentials measured at 90%. For the RV preparations, TDR was measured just before and after the dome was lost in the presence of 15 μM NS5806. n=5–8.

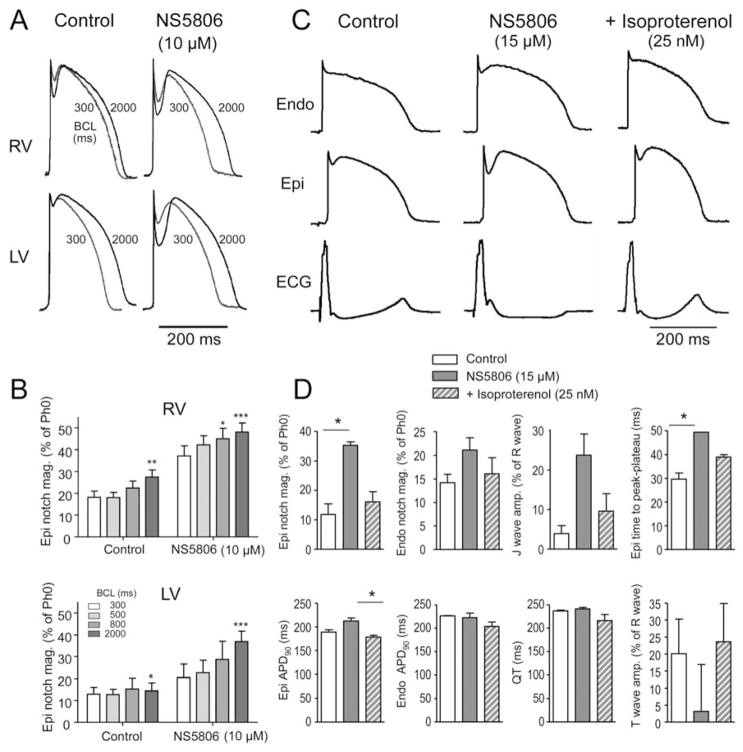

The arrhythmias associated with BrS often occur at rest while at higher heart rates, there is a normalization of the ECG. In agreement with these observations, we found the epicardial notch magnitude was higher at slow rates, most pronounced in the RV wedges (Figs. 6A and 6B). The smaller epicardial notch magnitude at 300 and 500 ms BCL pacing is due to some inactivation of Ito (Fig. 1G). Application of NS5806 sped up the recovery of the Ito currents (Fig. 1G) resulting in a relatively larger epicardial notch magnitudes at faster pacing in both RV and LV wedges. The BrS phenotype is also modulated by autonomic influences on the heart. The syndrome can be unmasked by vagal stimulation whereas sympathetic stimulation is effective in preventing the ECG and arrhythmic manifestations of BrS19. In another series of experiments, we examined the effect of sympathetic agonists. Fig. 6C shows representative recordings of APs from LV ventricular wedge preparations recorded under control conditions, after NS5806 (15 μM), and after NS5806 (15 μM) + isoproterenol (iso, 25 nM). Fig. 6D illustrates composite data from 3 experiments. Iso reversed the effects of NS5806 towards control values.

Figure 6.

The effect of NS5806 (10 μM) at different pacing rates on the epicardial notch magnitude. A) Representative APs recorded at increasing BCL from 300 to 2000 ms from canine right (RV) and left (LV) ventricular wedge preparations. B) The epicardial notch magnitude is plotted as % of phase 0 amplitude. (n=4–6). C) Effect of isoproterenol (25 nM) to reverse the effect of NS5806 (15 μM) in a left ventricular wedge preparation. Representative of n=3. D) Mean data showing effect of NS5806 and NS5806+iso on various electrophysiological parameters. Results were compared by Friedman test and Dunns post test.

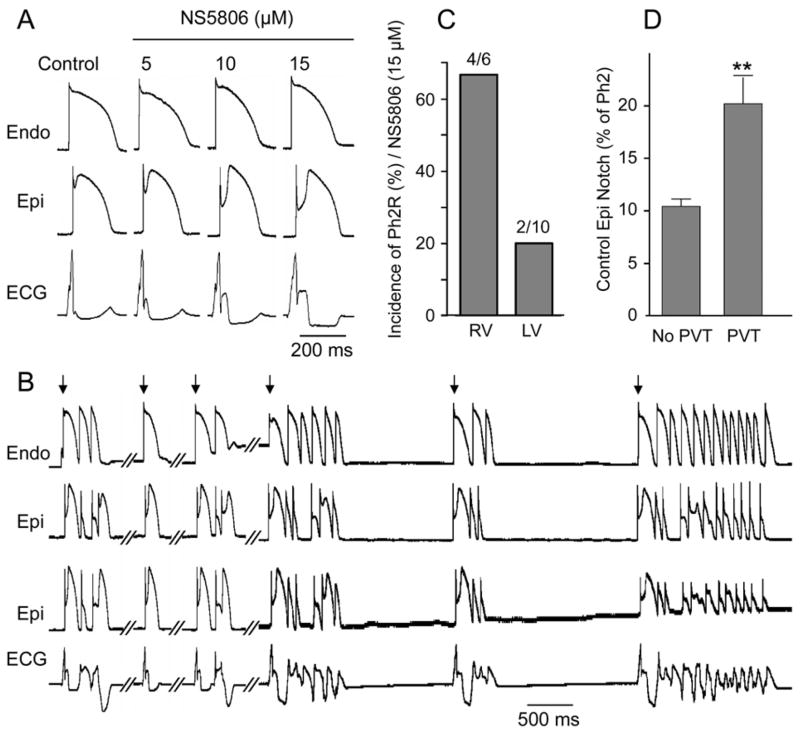

While sodium and calcium channel blockers are capable of inducing BrS only in RV wedge preparations, the Ito activator was able to induce the phenotype in wedges from both the RV and LV of the canine heart. Fig. 7 shows representative recordings from a LV wedge exposed to increasing concentrations of NS5806. As with RV wedge preparations, the size of the epicardial notch was progressively more accentuated with a parallel increase in the amplitude of the J wave. At a concentration of 15 μM NS5806 induced PVT (Fig. 7B). Two epicardial AP recordings were recorded simultaneously to demonstrate the heterogeneity in the tissue. Although PVTs were inducible in preparations from both RV and LV, the RV was more sensitive, most likely due to the higher intrinsic levels of Ito. At a concentration of 15 μM, NS5806 induced BrS in 4 out of 6 RV wedge preparations compared to 2 out of 10 LV wedge preparations (Fig. 7C). The depth of the epicardial notch under control condition was an important determinant of whether or not arrhythmias would develop (Fig. 7D).

Figure 7.

Effect of NS5806 to induce the electrocardiographic and arrhythmic manifestation of Brugada syndrome in a canine left ventricular (LV) wedge preparation paced at a BCL of 2 s. A) Representative recordings of APs and corresponding ECG before and after NS5806 (0–15 μM). B) The same preparation following 35 min exposure to 15 μM NS5806 showing development of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (PVT). The arrows indicate paced beats. C) Incidence of PVT in the presence of 15 μM NS5806 in right ventricular wedges (RV) vs. LV wedge preparations. D) Size of the epicardial notch in control in preparations exhibiting PVT (n= 6) vs. preparations without PVT (n=5), Results from RV and LV wedge preparations are pooled.

Discussion

In this study, we introduce and characterize the first known Ito activator and use it to generate a new experimental model of BrS. The Ito activator NS5806 is shown to increase peak Ito amplitude and to delay inactivation in isolated cardiomyocytes resulting in an accentuated phase 1 repolarization accompanied by loss of the AP dome in mid- and epicardial cells.

A link between mutations in genes responsible for the Ito current and the development of BrS was recently reported by Delpón and coworkers, where a mutation in the KCNE3 gene was found to be associated with the development of BrS10. KCNE3 normally interacts with Kv4.3 to suppress Ito20 and the mutation in KCNE3 was shown to result in a gain of function in Ito10. The results of our study using the Ito activator are consistent with the clinical observations that an enhancement of Ito can lead to the development of BrS.

It is well established that mutations leading to a decrease in INa or ICaL can also cause BrS in humans6–9. Previously developed experimental models of BrS, consistent with these genotypes, involved the use of sodium and calcium channel blockers such as terfenadine and verapamil in right ventricular wedge preparations21–23. Other experimental models of BrS involved the use of IK-ATP activators such as pinacidil12. The new experimental model, involving the use of an Ito activator, recapitulates all of the electrographic and arrhythmic manifestation of BrS, thus providing evidence in support of a pivotal role for Ito in the genesis of the disease.

BrS is a right ventricular disease in which ST segment elevation is usually limitedto the right precordial leads. The right ventricular manifestations of the disease are thought to be due to the prominence of Ito in right vs. left ventricular epicardium12. Less commonly encountered is a variant of BrS in which ST segment elevation is present in the left or inferior leads or throughout the precordium3–5; 24–26. A single BrS patient carrying a SCN5A mutation exhibiting ST elevation in the right and in the inferior leads has previously been described5, however the ST elevation in the inferior leads were only found in 1 out of 4 family members and other gene candidates were not studied. Our results demonstrate for the first time the ability to induce BrS phenotype in left ventricular tissues. NS5806 was able to induce the phenotype in wedges from both RV and LV of the canine heart, suggesting that augmentation of Ito could induce the BrS phenotype in any region of the heart. This suggest that a genetic defect leading to a prominent gain of function of Ito could explain variants of BrS in which ST segment elevation or J-waves are evident in right, left or inferior ECG leads.

Arrhythmias associated with BrS are often triggered by vagal influence and bradycardia1. We found that in both RV and LV, the effect of NS5806 to amplify the epicardial notch magnitude was bradycardia-dependent (Figs. 6A–B). Furthermore, theeffect of sympathetic influences to reverse the effects of the Ito activator to induce the BrS phenotype (Figs. 6C–D), is consistent with the ameliorative effects of β-adrenergic agonists in the clinic where isoproterenol has been shown to be effective in normalizing the ST-elevation and in controlling electrical storm in BrS patients27; 28. This effect is due to the positive chronotropic effect and increased calcium current secondary to increased intracellular cAMP rather than inhibition of Ito.

Our new experimental model of BrS also recapitulates the clinical finding that a slight increase in QT interval is observed in the right precordial leads in association with ST segment elevation in some BrS patients6. Our model shows that the prolongation of APD90 in the epicardium is caused by an increase in time-to-peak plateau following exposure to increasing concentrations of NS5806 (Fig. 5).

In summary, our experimental model recapitulates the electrocardiographic manifestations of BrS and should prove useful in further assessment of the cellular mechanisms underlying the development of arrhythmias associated with BrS and particularly valuable in the identification of pharmacological agents useful in the approach to therapy.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Carlsberg Foundation [2006010173 to K.C.]; the American Health Assistance Foundation [J.M.C.]; the Danish National Research Foundation [S.P.O.]; the National Institutes of Health [HL 47678 to CA] and the Masons of New York State and Florida.

The authors wish to thank Judy Hefferon and Arthur Iodice for valuable technical assistance.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest. Rie S Hansen and Morten Grunnet are employees of NeuroSearch. Søren-Peter Olesen is consultant to the company.

References

- 1.Antzelevitch C. Brugada syndrome. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2006;29:1130–1159. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2006.00507.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brugada P, Brugada J. Right bundle branch block, persistent ST segment elevation and sudden cardiac death: a distinct clinical and electrocardiographic syndrome. A multicenter report. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;20:1391–1396. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90253-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horigome H, Shigeta O, Kuga K, Isobe T, Sakakibara Y, Yamaguchi I, et al. Ventricular fibrillation during anesthesia in association with J waves in the left precordial leads in a child with coarctation of the aorta. J Electrocardiol. 2003;36:339–343. doi: 10.1016/s0022-0736(03)00079-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogawa M, Kumagai K, Yamanouchi Y, Saku K. Spontaneous onset of ventricular fibrillation in Brugada syndrome with J wave and ST-segment elevation in the inferior leads. Heart Rhythm. 2005;2:97–99. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Potet F, Mabo P, Le CG, Probst V, Schott JJ, Airaud F, et al. Novel brugada SCN5A mutation leading to ST segment elevation in the inferior or the right precordial leads. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2003;14:200–203. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2003.02382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antzelevitch C, Pollevick GD, Cordeiro JM, Casis O, Sanguinetti MC, Aizawa Y, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the cardiac calcium channel underlie a new clinical entity characterized by ST-segment elevation, short QT intervals, and sudden cardiac death. Circulation. 2007;115:442–449. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.668392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Q, Kirsch GE, Zhang D, Brugada R, Brugada J, Brugada P, et al. Genetic basis and molecular mechanism for idiopathic ventricular fibrillation. Nature. 1998;392:293–296. doi: 10.1038/32675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watanabe H, Koopmann TT, Le SS, Yang T, Ingram CR, Schott JJ, et al. Sodium channel beta1 subunit mutations associated with Brugada syndrome and cardiac conduction disease in humans. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2260–2268. doi: 10.1172/JCI33891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.London B, Michalec M, Mehdi H, Zhu X, Kerchner L, Sanyal S, et al. Mutation in glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase 1 like gene (GPD1-L) decreases cardiac Na+ current and causes inherited arrhythmias. Circulation. 2007;116:2260–2268. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.703330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delpón E, Cordeiro JM, Núñez L, Bloch-Thomsen PE, Guerchicoff A, Pollevick GD, et al. Functional effects of KCNE3 mutation and its role in the development of Brugada syndrome. Circ Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2008;1:209–218. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.107.748103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Diego JM, Sun ZQ, Antzelevitch C. I(to) and action potential notch are smaller in left vs. right canine ventricular epicardium. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:H548–H561. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.2.H548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Diego JM, Cordeiro JM, Goodrow RJ, Fish JM, Zygmunt AC, Perez GJ, et al. Ionic and cellular basis for the predominance of the Brugada syndrome phenotype in males. Circulation. 2002;106:2004–2011. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000032002.22105.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cordeiro JM, Greene L, Heilmann C, Antzelevitch D, Antzelevitch C. Transmural heterogeneity of calcium activity and mechanical function in the canine left ventricle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H1471–H1479. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00748.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cordeiro JM, Malone JE, Di Diego JM, Scornik FS, Aistrup GL, Antzelevitch C, et al. Cellular and subcellular alternans in the canine left ventricle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H3506–H3516. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00757.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dumaine R, Cordeiro JM. Comparison of K+ currents in cardiac Purkinje cells isolated from rabbit and dog. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;42:378–389. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cordeiro JM, Mazza M, Goodrow R, Ulahannan N, Antzelevitch C, Di Diego JM. Functionally Distinct Sodium Channels in Ventricular Epicardial and Endocardial Cells Contribute to a Greater Sensitivity of Epicardium to Electrical Depression. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H154–62. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01327.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verkerk AO, Wilders R, Schulze-Bahr E, Beekman L, Bhuiyan ZA, Bertrand J, et al. Role of sequence variations in the human ether-a-go-go-related gene (HERG, KCNH2) in the Brugada syndrome. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;68:441–453. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordon E, Lozinskaya IM, Lin Z, Semus SF, Blaney FE, Willette RN, et al. PD-307243 Causes Instantaneous Current Through Human Ether-a-go-go-Related Gene (hERG) Potassium Channels. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;73:639–51. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.041152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Antzelevitch C, Fish JM. Therapy for the Brugada syndrome. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2006:305–330. doi: 10.1007/3-540-29715-4_12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lundby A, Olesen SP. KCNE3 is an inhibitory subunit of the Kv4.3 potassium channel. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;346:958–967. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fish JM, Antzelevitch C. Role of sodium and calcium channel block in unmasking the Brugada syndrome. Heart Rhythm. 2004;1:210–217. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2004.03.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yan GX, Antzelevitch C. Cellular basis for the Brugada syndrome and other mechanisms of arrhythmogenesis associated with ST-segment elevation. Circulation. 1999;100:1660–1666. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.15.1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aiba T, Shimizu W, Hidaka I, Uemura K, Noda T, Zheng C, et al. Cellular basis for trigger and maintenance of ventricular fibrillation in the Brugada syndrome model: high-resolution optical mapping study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:2074–2085. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.12.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalla H, Yan GX, Marinchak R. Ventricular fibrillation in a patient with prominent J (Osborn) waves and ST segment elevation in the inferior electrocardiographic leads: a Brugada syndrome variant? J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2000;11:95–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2000.tb00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ogawa R, Kishi R, Mihara K, Takahashi H, Takagi A, Matsumoto N, et al. Population pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic analysis of a class IC antiarrhythmic, pilsicainide, in patients with cardiac arrhythmias. J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;46:59–68. doi: 10.1177/0091270005283281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ozeke O, Aras D, Celenk MK, Deveci B, Yildiz A, Topaloglu S, et al. Exercise-induced ventricular tachycardia associated with J point ST-segment elevation in inferior leads in a patient without apparent heart disease: a variant form of Brugada syndrome? J Electrocardiol. 2006;39:409–412. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suzuki H, Torigoe K, Numata O, Yazaki S. Infant case with a malignant form of Brugada syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2000;11:1277–1280. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2000.01277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanaka H, Kinoshita O, Uchikawa S, Kasai H, Nakamura M, Izawa A, et al. Successful prevention of recurrent ventricular fibrillation by intravenous isoproterenol in a patient with Brugada syndrome. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2001;24:1293–1294. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2001.01293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]