Abstract

PURPOSE

Adenoid cystic carcinomas (ACC) represent a heterogeneous group of chemotherapy-refractory tumors, with a subset demonstrating an aggressive phenotype. We investigated the molecular underpinnings of this phenotype and assessed the Notch1 pathway as a potential therapeutic target.

METHODS

We genotyped 102 ACCs with available pathologic and clinical data. Notch1 activation was assessed by immunohistochemistry for Notch1 intracellular domain (NICD). Luciferase reporter assays were used to confirm Notch1 target gene expression in vitro. The Notch1 inhibitor brontictuzumab was tested in ACC patient-derived xenografts (PDXs) and an ACC patient enrolled in a phase I study.

RESULTS

NOTCH1 mutations occurred predominantly (14/15 cases) in the negative regulatory region (NRR) and PEST domains, the same two “hot-spots” seen in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemias, and led to pathway activation in vitro. NOTCH1 mutant tumors demonstrated significantly higher levels of Notch1 pathway activation than wild-type based on NICD staining (P=0·004). NOTCH1 mutations define a distinct, aggressive ACC subgroup with a significantly higher likelihood of solid subtype (P=0·0009), advanced disease stage at diagnosis (P=0·02), higher rate of liver and bone metastasis (P≤0·02), and shorter relapse-free (median 13 vs. 34 months, P=0·01) and overall survival (median 30 vs. 122 months, P=0·001) when compared to NOTCH1 wild-type. Significant tumor growth inhibition with brontictuzumab was observed exclusively in the ACC PDX model harboring a NOTCH1 activating mutation. Furthermore, an index NOTCH1 mutant ACC patient had a partial response to brontictuzumab.

CONCLUSION

NOTCH1 mutations define a distinct disease phenotype characterized by solid histology, liver and bones metastasis, poor prognosis, and potential responsiveness to Notch1 inhibitors. Clinical studies targeting Notch1 in a genotyped defined ACC subgroup are warranted.

INTRODUCTION

Adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC) is a common malignant salivary gland tumor with a recurrence rate following curative intent treatment of 40–50% 1,2. ACC is overall chemotherapy-refractory and there is no standard of care treatment for patients with recurrent/metastatic disease 3.

Whole-exome sequencing (WES) of ACC samples has shed light on the genetic landscape of this disease and provides evidence for Notch pathway alterations in 11–29% of cases 4–6. The Notch pathway is involved in cancer relevant functions, including maintenance of stem cells, cell fate specification, proliferation, and angiogenesis 7. There are four NOTCH genes that encode transmembrane receptors (NOTCH 1-4) and five membrane-bound ligands: Delta-like ligands (DLL) 1,3-4; and Jagged (JAG) 1–2. Notch signaling is usually initiated by receptor-ligand interaction, which leads to consecutive receptor cleavages, the second by the gamma-secretase complex that frees the Notch intracellular domain (NICD) to enter the nucleus, displace co-repressors such as SPEN 4, and form a transcriptional activation complex with the DNA-binding factor RBPJ and co-activators of the mastermind-like family 8. The generation and stability of NICD is regulated by the ubiquitin ligase complexes containing FBXW7 9.

Deregulation of the Notch1 pathway occurs in multiple cancers, although its specific roles and potential value as a therapeutic target varies. NOTCH1 mutations are oncogenic drivers in 50% of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemias (T-ALL) 10. T-ALL activating mutations concentrate in two “hot spot” regions: in-frame mutations in exons 25–28 that disrupt the negative regulatory region (NRR) and lead to ligand-independent Notch1 activation; and stop-codon or nonsense mutations in exon 34 that result in deletion of C-terminal degron domain (PEST) and NICD stabilization. Notch signaling can also be activated in T-ALL through translocations, duplication insertions in the vicinity of exon 28, or FBXW7 mutations 11,12. Notch1 can act as a tumor suppressor in other malignancies, such as oral squamous cell carcinoma, where loss-of-function NOTCH1 mutations occur in the epidermal growth factor–like domain 13–15.

In this study, we describe that NOTCH1 mutations in ACC occur predominately in the T-ALL hot spots, are activating, and define a subgroup of patients with solid subtype, advanced disease stage, distinct pattern of metastasis, and worse prognosis. We also report in an index patient that the acquisition of mutations leading to further Notch1 pathway activation probably occur as the tumor progresses. Furthermore, Notch1 inhibitor demonstrated antitumor activity in a NOTCH1 mutant ACC xenograft and in a NOTCH1 mutant patient, demonstrating that Notch1 is a potential therapeutic target in a subgroup of ACC.

METHODS

Patient selection

The patient population consisted of 102 ACC cases: 70 patients with primary tumor available for WES (47 cases in addition to the 24 previously published 4); and 32 patients who had their tumor genotyped from 01/01/2013 until 03/31/2015 at the request of the treating oncologist using target-sequencing platforms. Patient samples were obtained either by an IRB-approved waiver of informed consent (for deceased patients), or by informed consent (front-door consent). Pathologic and clinical data were retrospectively obtained from electronic medical records according to the IRB-approved protocol PA14-0375. Data acquisition was locked on 12/07/2015. At the date of analysis, 46 patients were alive (33 with disease and 13 without disease), and 56 were deceased (44 with disease, five without disease, and seven with unknown disease status).

Genomic Analysis

WES was performed using DNA obtained from fresh-frozen samples, as previously described 4. Target exome sequencing or analysis of hotspots mutations in cancer-related genes was done using next-generation sequencing as described in Supplementary Appendix.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

The rabbit monoclonal cleaved-Notch1 antibody (Val1744) (D3B8, #4147, Cell Signaling) was used for NICD IHC staining as previously described 16. Details are available in Supplementary Appendix.

Luciferase reporter assay

Luciferase reporter assay was performed utilizing 293T cells. NOTCH1 mutations identified in a patient were constructed by site-directed mutagenesis. For details, see Supplementary Appendix.

Patient Derived Xenograft (PDX) drug screening

The antitumor activity of brontictuzumab was tested in previously established and genotyped ACC PDX 17 as detailed in Supplementary Appendix.

Statistical analysis

Fisher’s exact test was applied to describe the association between NOTCH1 mutation or NICD expression and clinicopathological characteristics. An analysis evaluating the association between NOTCH1 mutational status and specific sites of disease recurrence was undertaken among patients with local or distant recurrence. Relapse-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method. RFS was defined as the time from diagnosis to relapse or death, whichever occurred first. Observation for RFS was censored at the date of last contact for patients last known to be alive without relapse. OS was defined as the time from diagnosis to death from any cause. Survivors or patients who lost follow-up were censored at the last contact date. Univariate and multivariable analyses Cox proportional hazards model were applied to identify important prognostic factors for OS and RFS. All P values were two-sided. P<0·05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

NOTCH1 mutations in ACC occur in “hot-spots” and are associated with pathway activation

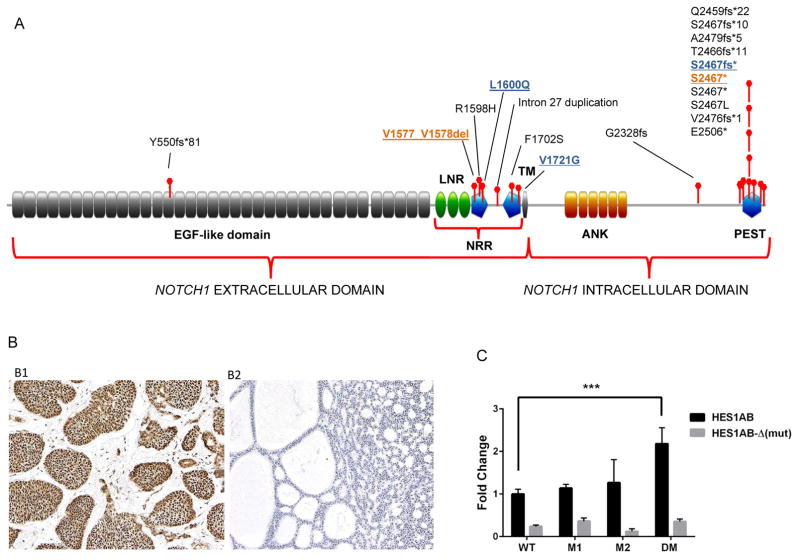

Expanding on our prior work sequencing 24 ACC 4, genomic profiling was conducted in 102 tumors, including WES in an additional 46 samples and 32 samples for which we had targeted sequencing information for gene panel that included NOTCH1. Eighteen NOTCH1 mutations were identified in 15 tumors, with two patients harboring more than one NOTCH1 mutation. Seventeen of these mutations in 14 patients (14/102, 13·7%) occurred in the T-ALL “hot-spots”, suggesting they are gain-of-function (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

(A) NOTCH1 mutations in ACC patients occurred predominantly in the same NRR and PEST domain “hot spots” as those observed in T-ALL and are predictive to be activating. NRR: Negative Regulatory Region; LNR: Lin12/NOTCH repeats; TM: transmembrane domain; ANK: ankyrin repeat domain; PEST: Pro-Glu-Ser-Thr rich domain; (B) Notch1 intracellular domain (NICD) immunostaining in ACC. B1: Positive uniform nuclear expression of NICD in solid form of ACC, and B2: ACC negative for NICD expression; (C) In vitro reporter assay assessing Notch1 pathway activation induced by individual mutations and the combination of both mutations observed in an index patient. M1 = NOTCH1 S2467fs* mutation, M2 = NOTCH1 L1600Q, and DM = NOTCH1 S2467fs* and L1600Q co-mutations. 293T cells were co-transfected with NOTCH1 wild-type or NOTCH1 mutant constructs and HES1AB-responsive luciferase reporter, HES1AB-Δ luciferase mutant form or Renilla luciferase control. Firefly/Renilla luciferase activity was measured in cell lysates after 48 hours. The DM led to a statistically significant 2.2-fold increase in reporter activity compared with wild-type NOTCH1 (***P<0·0001).

To evaluate whether these mutations were activating, we assessed the association between NOTCH1 mutations and NICD IHC staining (Figure 1B), an established marker for Notch1 pathway activation 16. Tumor tissues from 72 patients were available for NICD staining. There was a statistically significant association between NOTCH1 mutations and NICD positivity. All 10 tumors (100%) with NOTCH1 mutations predicted to be activating were NICD positive, while 30 of 61 NOTCH1 wild-type tumors (49%) stained positive (P=0·004); the only tumor with a NOTCH1 mutation predicted to be inactivating (Y550fs*51) was NICD negative.

Double NOTCH1 mutations lead to increased pathway activation

To further characterize the functional role of the NOTCH1 mutations observed in an index patient, we conducted in vitro analysis of pathway activation using a luciferase reporter assay bearing the promoter of HES1, a Notch1 transcriptional target. 293T cells were co-transfected with a HES1-responsive luciferase reporter vector and constructs carrying an initially observed NOTCH1 mutation S2467fs*, the acquired mutation L1600Q, and the L1600Q/S2467fs* co-mutations. As expected, the cells co-transfected with the co-mutations increased luciferase activity irrespective of the presence of the ligand (Figure 1C) to a greater extent than either mutation alone or wild-type NOTCH1, supporting that the NOTCH1 mutations were transcriptionally activating. While we detect an increase in pathway activation with each individual NOTCH1 mutation, these results were not statistically significant when compared to NOTCH1 wild type, probably due to limitations of the transient co-transfection assay.

Mutations in other NOTCH-related genes

Mutations were also observed in other genes known to impact the Notch pathway. Mutations in SPEN were observed in six patients, including three concurrent with NOTCH1. Two patients had NOTCH2 mutations; one of them with a SPEN co-mutation. Interestingly, co-mutations in NOTCH1 and NOTCH4, NOTCH1 and JAG1, and NOTCH1 and FBXW7 were also identified (Supplemental Table1). Additionally, one patient had a mutation in RBPJ, the main transcriptional effector of Notch signaling. In total, 20 patients (20%) had mutations in known Notch pathway-related genes, predicted to activate the pathway.

Population characteristics

The overall patient characteristics are described in Table 1. The median age at diagnosis was 52-years-old, and the main primary tumor site was the minor salivary glands. MYB/MYBL1 rearrangement or overexpression was identified in 74% and 77% of the available samples respectively. The majority of patients presented with disease stage I-III and was treated with surgery followed by adjuvant radiotherapy with or without concurrent cisplatin. Eighty percent of patients relapsed, with lung being the most common site of recurrence. Metastasis to atypical sites such as brain, peritoneum, and subcutaneous tissue occurred in 23 patients. Fifty-eight percent of patients with recurrent disease received systemic therapy.

Table 1.

Baseline patients and tumor characteristics

| Characteristic | N or Median | % or Range |

|---|---|---|

| AGE | 52 | 19–75 |

| SEX | ||

| Male | 63 | 62 |

| Female | 39 | 38 |

| DISEASE SITE | ||

| Minor salivary glands | 52 | 51 |

| Major salivary glands | 30 | 29 |

| Trachea | 11 | 11 |

| Other sites | 9 | 9 |

| HISTOLOGICAL SUBTYPE | ||

| Tubular | 7 | 7 |

| Cribriform | 35 | 34 |

| Solid | 36 | 35 |

| Unknown | 24 | 24 |

| MYB/MYBL1 GENE REARRANGEMENT | ||

| Positive | 46 | 45 |

| Negative | 16 | 16 |

| Unknown | 40 | 39 |

| MYB/MYBL1 PROTEIN EXPRESSION | ||

| High | 54 | 53 |

| Low | 16 | 16 |

| Unknown | 32 | 31 |

| T STAGE | ||

| T1/T2 | 16 | 16 |

| T3 | 34 | 33 |

| T4 | 41 | 40 |

| Unknown | 11 | 11 |

| PERINEURAL INVASION | ||

| Yes | 75 | 74 |

| No | 6 | 6 |

| Unknown | 21 | 20 |

| DISEASE STAGE AT DIAGNOSIS | ||

| I/II/III | 42 | 41 |

| IVA/B | 36 | 35 |

| IVC | 16 | 16 |

| Unknown | 8 | 8 |

| TREATMENT MODALITY TO THE PRIMARY TUMOR | ||

| Surgery | 94 | 92 |

| Concurrent chemoradiation | 6 | 6 |

| No treatment | 2 | 2 |

| ADJUVANT RADIATION THERAPY (+/− CT) | 81 | 79 |

| DISEASE RECURRENCE | 82 | 80 |

| RECURRENCE SITE (Among 82 recurrent patients) | ||

| Local | 25 | 30 |

| Lung | 55 | 67 |

| Pleura | 16 | 20 |

| Bone | 36 | 44 |

| Liver | 15 | 18 |

| Others | 23 | 28 |

| SYSTEMIC THERAPY | 48 | 58 |

CT: chemotherapy

NOTCH1 mutations define a distinct biological phenotype

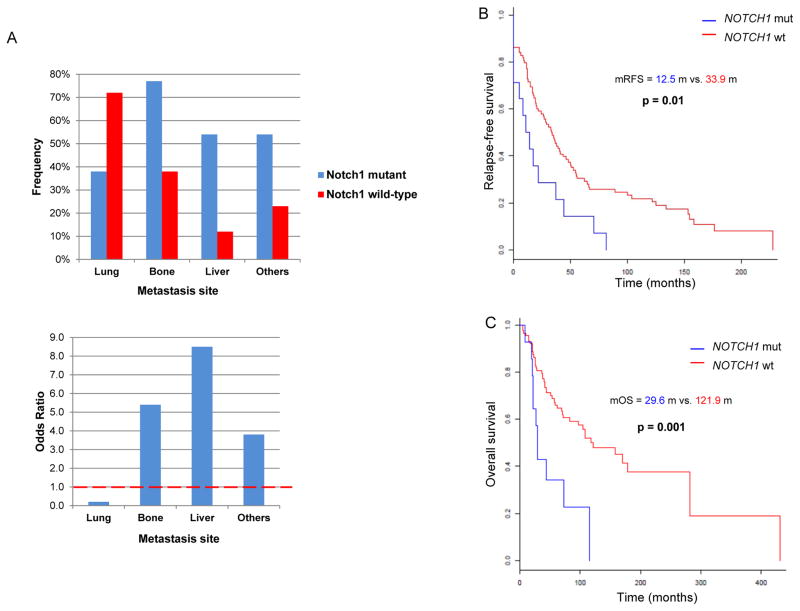

The correlation between clinic-pathologic characteristics and NOTCH1 mutational status is described in Table 2. Compared to those with NOTCH1 wild-type, mutant patients were more likely to have solid histology (P=0·0009), present with advanced disease stage (P=0·02), or both (solid subtype and stage IV vs. others, P=0·01). In spite of lung being the most common site of metastasis among patients with recurrent ACC, NOTCH1 mutants were less likely to develop lung metastasis (Odds Ratio [OR]=0·24, P=0·02) but had a far higher likelihood of developing metastasis in the liver (OR=8·5, P=0·002), bone (OR=5·4, P=0·01), and atypical sites (OR=3·8, P=0·04) (Figure 2A). Similar results were obtained when we included the 20 patients with mutations expected to activate the Notch pathway (Supplemental Table 4). We also performed correlation analysis between NICD positive (40) versus negative (32) tumors. NICD positive tumors were more likely to have solid histology (P=0·02) and liver metastasis (P=0·02).

Table 2.

Correlation between clinic-pathologic characteristics and NOTCH1 mutational status in 102 patients with 14 and 88 patients with and without NOTCH1 mutations.

| NOTCH1 mut | NOTCH1 wt | OR | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DISEASE STAGE AT DIAGNOSIS | ||||

| I/II/III | 2/14 (14%) | 40 /88 (45%) | 0.02* | |

| IVA/B | 8/14 (57%) | 28/88 (32%) | ||

| IVC | 4/14 (29%) | 12/88 (14%) | ||

| Unknown | 0 (0%) | 8/88 (9%) | ||

| HISTOLOGICAL SUBTYPE | ||||

| Tubular/cribriform | 1/14 (7%) | 41/88 (47%) | 0.0009** | |

| Solid | 11/14 (79%) | 25/88 (28%) | ||

| Unknown | 2/14 (14%) | 22/88 (25%) | ||

| DISEASE SITE | ||||

| Minor salivary glands | 8/14 (57%) | 44/88 (50%) | 0.33 | |

| Major salivary glands | 2/14 (14%) | 28/88 (32%) | ||

| Others | 4/14 (29%) | 16/88 (18%) | ||

| DISEASE RECURRENCE | 13/14 (93%) | 69/88 (78%) | 0.3 | |

| SITE OF RECURRENCE (Among 82 recurrent patients) | ||||

| Local | 7/13 (54%) | 18/69 (26%) | 3.3 | 0.06 |

| Lung | 5/13 (38%) | 50/69 (72%) | 0.24 | 0.02 |

| Pleura | 1/13 (8%) | 15/69 (22%) | 0.3 | 0.44 |

| Bone | 10/13 (77%) | 26/69 (38%) | 5.4 | 0.01 |

| Liver | 7/13 (54%) | 8/69 (12%) | 8.5 | 0.002 |

| Others | 7/13 (54%) | 16/69 (23%) | 3.8 | 0.04 |

Mut: mutant; wt: wild-type; OR: Odds ratio based on the conditional maximum likelihood estimate; P-value is based on the two-sided Fisher’s exact test.

: compared NOTCH1 mut status between stage IV vs. I-III.

: compared NOTCH1 mut status between solid vs. others.

Figure 2.

(A) Odd Ratio (OR) of metastasis to specific organs in NOTCH1 mutants versus wild type; (B) Kaplan-Meier estimates of recurrence-free survival (RFS) of NOTCH1 mutants versus wild-type; (C) Kaplan-Meier estimates of overall survival (OS) of NOTCH1 mutants versus wild-type.

NOTCH1 mutation is prognostic in ACC but not an independent prognostic factor in the presence of histological subtype and stage

The median RFS and OS in the overall population were 30 and 108 months respectively. Median RFS was 12·5 versus 33·9 months for NOTCH1 mutant versus wild-type (P=0·01) (Figure 2B). OS was significantly shorter in the NOTCH1 mutants with a median of 29·6 versus 121.9 months for NOTCH1 wild-type (P=0·001) (Figure 2C). MYB/MYBL1 rearrangement and/or overexpression did not influence RFS or OS irrespective of NOTCH1 mutational status (Supplemental Figure1). The NICD positive group showed a shorter RFS compared with NICD negative (14·6 vs. 39 months, P=0·03), however, OS did not significantly differ between NICD positive and negative (44 vs. 108 months, P=0·2).

Univariate and multivariable Cox models for OS and RFS (Supplemental Tables 2, 3) were performed. For OS, significant predictor variables by the univariate analysis were: age, histology, disease stage, and NOTCH1 mutational status. Histological subtype was the only significant predictor for OS in the multivariable analysis. For RFS, histology, disease stage, and NOTCH1 mutational status were significant predictors by the univariate analysis. Both histological subtype and stage remained significant in the multivariable analysis. The results held when the non-significant predictors were removed from the model and were similar when mutation in genes predicted to activate the Notch-pathway were considered (Supplemental Tables 5 and 6). Hence, NOTCH1 mutation was not an independent prognostic factor when histology and stage were considered. The highly significant association between NOTCH1 mutation and solid histology (P=0.0009), advanced disease stage (P=0.02), or both (0.01), together with additional factors such as tumor heterogeneity could account for dilution of the prognostic significance of NOTCH1 mutations in the multivariable analysis.

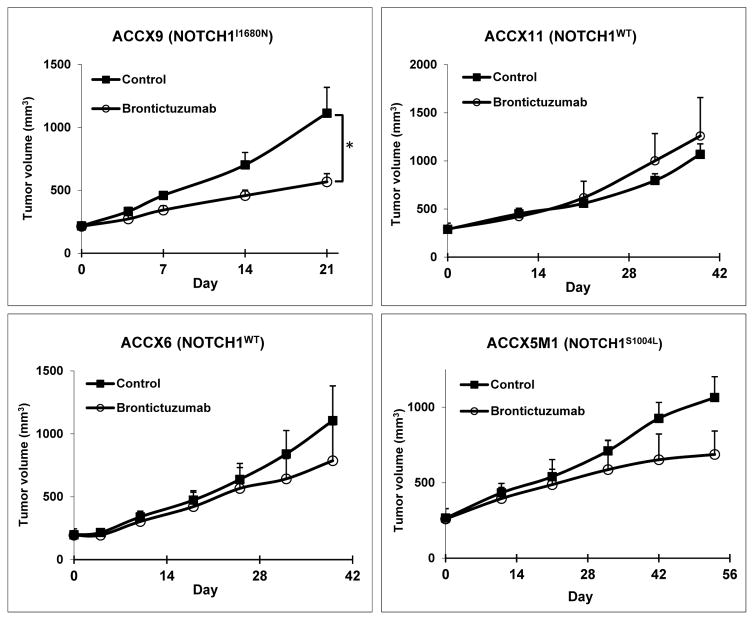

Notch1 inhibitor demonstrates activity in NOTCH1 mutant PDX

The PDX models ACCX9, ACCX11, ACCX5M1, and ACC6 were screened against brontictuzumab, a humanized IgG2 antibody that inhibits Notch1 signaling. ACCX9 harbors a HD NOTCH1 I1680N activating mutation, ACCX5M1 harbors a NOTCH1 S1004L inactivating mutation in the EGF-repeat domain, ACCX11 has a tandem duplication 3′ of NOTCH1, and ACCX6 is NOTCH1 wild-type. All four models have MYB rearrangements. NICD IHC staining was positive in the ACCX9 and ACCX11 models (Supplemental Figure 2). Brontictuzumab significantly inhibited tumor growth in ACCX9 (P<0·05), but not in the models lacking activating NOTCH1 mutations (Figure 3), providing support for Notch1 as a therapeutic target in this NOTCH1 mutated PDX.

Figure 3.

The Notch1 inhibitor brontictuzumab lead to significant tumor growth inhibition exclusively in the ACCX9 patient-derived xenograft (PDX) model harboring a NOTCH1 activating mutation (I1680N). Mice were treated with brontictuzumab by intraperitoneal injection at 40 mg/kg once every two weeks for two total doses and mean tumor volume was assessed. Error bars indicate standard error of measurement (SEM). *P<0·05.

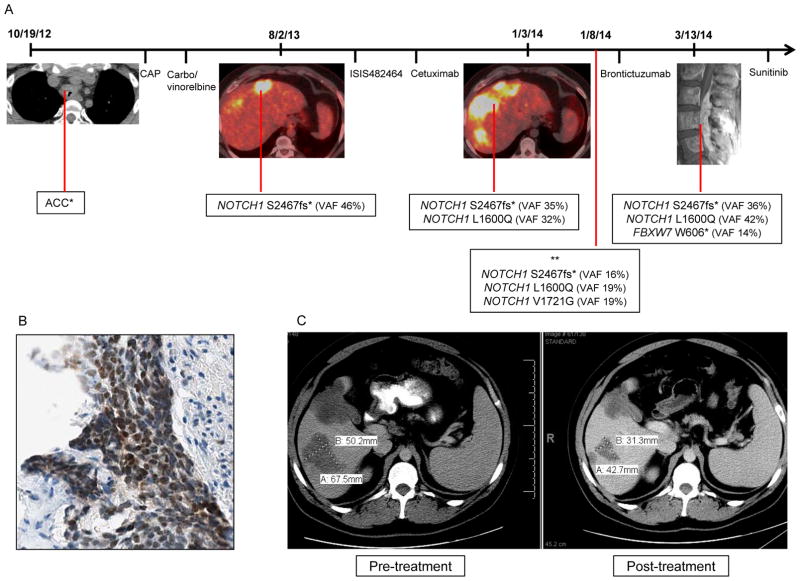

Notch1 inhibitor led to partial response (PR) in a NOTCH1 mutant ACC patient

The patient was a 28-year-old male who presented with a tracheal ACC metastatic to mediastinal nodes, bone, and liver. He received palliative radiotherapy to the tracheal mass and osseous metastases, followed by two lines of chemotherapy. He had evidence of rapid disease progression and underwent biopsy and genotyping of a liver metastasis that revealed a NOTCH1 PEST domain mutation (S2467fs). He was then treated with third and fourth line targeted-therapy. After further disease progression, a liver lesion biopsy revealed the original NOTCH1 mutation and an additional mutation in the HD (L1600Q) (Figure 4A). All mutations were confirmed to be somatic and had similar variant allele frequency (VAF). As predicted, the co-occurrence of these mutations conferred greater ligand-independent NOTCH1 activation in vitro (Figure 1C). Notch1 pathway activation was also confirmed by NICD immunostaining (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

(A)Tumor progression in an index ACC patient was associated with the sequential identification of multiple mutations in the Notch1 pathway. The peripheral blood sample showed wild-type sequence at all NOTCH1 amplicons/codons covered by the assay. *no tumor available for genotyping; ** genotyped performed in cell-free DNA. CAP: cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin and cisplatin; Carbo: carboplatin; VAF: variant allele frequency; ISIS482464: STAT3 inhibitor administered under a phase I clinical trial protocol; (B) Tumor from index patient with NOTCH1 mutant ACC was strongly positive for Notch1 intracellular domain (NICD) by immunohistochemistry; (C) NOTCH1 mutant ACC patient achieved a partial response with a 38% reduction in the target lesion upon treatment with two doses of the anti-Notch1 monoclonal antibody brontictuzumab.

The patient was treated with brontictuzumab and achieved a PR after two doses (Figure 4C), which was accompanied by marked reduction in bone pain and LDH levels. The patient unfortunately experienced a further rise in transaminases after cycle two thought to be drug-related, which led to brontictuzumab discontinuation and disease progression shortly thereafter. Liver toxicity was rarely observed in patients treated with the same drug 18. Sequencing of a new paraspinal metastasis confirmed the presence of the two NOTCH1 mutations and an additional mutation in FBXW7 (W606*). A third NOTCH1 mutation in the NRR (V1721G) was identified retrospectively in cell-free DNA. The patient received sunitinib with rapid disease progression. He eventually succumbed as a consequence of disease.

DISCUSSION

Recently, sequencing of ACC samples revealed genomic alterations in the Notch1 pathway in a subset of patients 4,5. In this study, we expanded our ACC WES efforts to include 46 cases to the 24 previously published 4, which makes this the largest ACC genotyped series. In addition, we analyzed 32 patients who had their tumor tested for NOTCH1 mutations in at least exons 26–27, 34.

Our results show that the majority of NOTCH1 mutations in ACC (91%) are predicted to be activating. They occur mostly in the T-ALL “hot-spots” and stain positive for NICD. As described in T-ALL 12, a patient with juxtamembrane expansion mutation was identified. Further, mutations in the HD and PEST domains co-occurred in two patients, including the reported case. The double NOTCH1 mutations (S2467fs*/L1600Q) led to ligand-independent expression of the NOTCH1 target gene HES1. The scarce tissue precluded us from establishing if the NOTCH1 co-mutations in the index patient occurred in cis, limiting the extrapolation of the luciferase assay results to the clinical setting.

While our data indicates that NOTCH1 mutations are associated with Notch1 pathway activation, it also suggests that pathway activation can occur by alternative routes. Canonical Notch signaling relies on nuclear translocation of NICD, and IHC NICD staining has been extensively validated in genotyped tumors 16. Our work demonstrates that NICD staining was very sensitive (100%) in its ability to identity patients with NOTCH1 activating mutations, however, it lacks specificity, as 49% of NOTCH1 wild-type tumors were NICD positive. The specific drivers of Notch1 pathway activation independent of mutations are undetermined. The majority of ACC overexpress Notch1 and its ligands and receptor-ligand interaction is a known mechanism of pathway activation 19. Mutations in genes such as SPEN, FBWX7, or RBPJ can also activate the Notch1 pathway. Genes encoding chromatin-state regulators are frequently mutated in ACC, and epigenetic mechanisms may also have a role in Notch1 pathway activation 4,5,19,20.

Using detailed histopathologic and clinical information of 102 patients, we demonstrated that NOTCH1 mutation defines a distinct ACC phenotype. While the majority of ACC patients have a protracted clinical course, NOTCH1 mutants have an aggressive disease with distinct pattern of metastasis, and worse prognosis. The association between NOTCH1 mutation and the more dedifferentiated solid subtype, a poor prognostic factor in ACC 21, suggests that Notch1 drives this histologic pro-metastatic phenotype. Furthermore, the tendency of NOTCH1 mutants to metastasize to liver and bone is intriguing. Dysregulation of Notch signaling can cause developmental disorders characterized by defective bile duct formation, heart disease, and skeletal defects 22. The Notch pathway also plays a role in liver regeneration, osteoblastic maturation, and bone maintenance 23,24. Expression of JAG1 and DLL4 are seen in the normal liver, while JAG1 is overexpressed on bone-marrow stromal cells 25,26. We hypothesize that the expression of Notch1 ligands in these organs provides a permissive environment for growth; however, the mechanisms associated with the preferential homing of NOTCH1 mutant ACC to liver and bone are currently unknown.

The potential oncogenic and pro-metastatic role of NOTCH1 mutations in ACC suggests that the pathway may be a therapeutic target. To test this directly, we used the Notch1-specific monoclonal antibody brontictuzumab, and found that it significantly inhibited tumor growth exclusively in the ACCX9 NOTCH1 mutant model. The therapeutic potential of targeting Notch is also supported by a preclinical study in which a gamma-secretase inhibitor (GSI) led to tumor growth inhibition of the ACCX9 PDX 27. The lack of tumor growth inhibition in the NICD positive ACCX11 model suggest that the mechanism by which the Notch1 pathway is activated may be important in predicting response from specific NOTCH1 inhibitors.

Validating the preclinical findings, we report an index case with NOTCH1 mutant ACC who achieved a PR after two doses of brontictuzumab administered under a clinical trial. This patient had at least two NOTCH1 mutations prior to starting treatment, with a third mutation detected in cell-free DNA, probably reflecting this patient’s tumor heterogeneity. In spite of not being possible to determine if the NOTCH1 and/or FBXW7 mutations were present throughout the disease course or were acquired as the tumor progressed, the appearance of a detectable FBXW7 mutation in a new clinically evident mass is consistent with clonal evolution of the patients’ disease. The acquisition of additional mutations and progressive NOTCH1 oncogene addiction contributing to the clinical evolution of the disease has been described in T-ALL and chronic lymphocytic leukemia 10,28. Furthermore, in T-ALL, FBXW7 mutations are mostly identified in relapsed patients and predicted resistance to gamma-secretase inhibitors 11,29. Ultimately, irrespective of the timing in which the NOTCH1 and FBXW7 mutations occurred during the disease course, the presence of multiple alterations promoting Notch1 signaling supports its central role as an oncogenic driver in this cancer.

Pre-clinical studies in T-ALL lines demonstrated that GSI induces growth suppression particularly in “NOTCH1 double-mutants”, however, the gastrointestinal toxicity associated with pan-Notch inhibitors has limited its clinical applicability 10. While a biomarker predictive of response to Notch1 inhibitors remains to be determined, our findings suggest that mutations in Notch1 pathway genes and NICD staining may be used to select patients for clinical trials with potentially less toxic specific Notch1 inhibitors 30.

CONCLUSION

Our analysis integrating genomic, pathological, and clinical outcomes data in ACC demonstrates that NOTCH1 mutations are activating and define a subgroup of patients with an aggressive disease phenotype and distinct pattern of metastatic spread. Notch1 inhibition with a specific antibody demonstrated antitumor activity in preclinical models, and an encouraging PR in a NOTCH1 mutant patient. Further studies investigating the activity of Notch1 inhibitors in biomarker-selected ACC patients are warranted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Research Support: Ryan W. Smith Endowed Fund for Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma, Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma Research Foundation (ACCRF), NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant (P30 CA016672), and NIH Office of Rare Diseases Research Grant (U01DE019765).

The authors would like to thank Kenna R. Shaw PhD, Mark J Routbort MD PhD, and the Sheikh Khalifa Bin Zayed Al Nahyan Institute for Personalized Cancer Therapy (IPCT), University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center for assistance with genomic profiling; all clinical investigators that participated in the clinical trial protocol NCT01778439; and Emily Roarty PhD for editorial assistance.

Footnotes

This study has been presented as a poster in the 2015 ASCO Annual Meeting.

References

- 1.Fordice J, Kershaw C, El-Naggar A, et al. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck: predictors of morbidity and mortality. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;125:149–52. doi: 10.1001/archotol.125.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spiro RH. Distant metastasis in adenoid cystic carcinoma of salivary origin. Am J Surg. 1997;174:495–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(97)00153-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laurie SA, Ho AL, Fury MG, et al. Systemic therapy in the management of metastatic or locally recurrent adenoid cystic carcinoma of the salivary glands: a systematic review. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:815–24. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70245-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stephens PJ, Davies HR, Mitani Y, et al. Whole exome sequencing of adenoid cystic carcinoma. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:2965–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI67201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ho AS, Kannan K, Roy DM, et al. The mutational landscape of adenoid cystic carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2013;45:791–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.2643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ross JS, Wang K, Rand JV, et al. Comprehensive genomic profiling of relapsed and metastatic adenoid cystic carcinomas by next-generation sequencing reveals potential new routes to targeted therapies. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:235–8. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grego-Bessa J, Diez J, Timmerman L, et al. Notch and epithelial-mesenchyme transition in development and tumor progression: another turn of the screw. Cell Cycle. 2004;3:718–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lobry C, Oh P, Aifantis I. Oncogenic and tumor suppressor functions of Notch in cancer: it’s NOTCH what you think. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1931–5. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lai EC. Protein degradation: four E3s for the notch pathway. Curr Biol. 2002;12:R74–8. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00679-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weng AP, Ferrando AA, Lee W, et al. Activating mutations of NOTCH1 in human T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Science. 2004;306:269–71. doi: 10.1126/science.1102160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Neil J, Grim J, Strack P, et al. FBW7 mutations in leukemic cells mediate NOTCH pathway activation and resistance to gamma-secretase inhibitors. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1813–24. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sulis ML, Williams O, Palomero T, et al. NOTCH1 extracellular juxtamembrane expansion mutations in T-ALL. Blood. 2008;112:733–40. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-130096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weng AP, Aster JC. Multiple niches for Notch in cancer: context is everything. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2004;14:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agrawal N, Frederick MJ, Pickering CR, et al. Exome Sequencing of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Reveals Inactivating Mutations in NOTCH1. Science. 2011 doi: 10.1126/science.1206923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pickering CR, Zhang J, Yoo SY, et al. Integrative genomic characterization of oral squamous cell carcinoma identifies frequent somatic drivers. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:770–81. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kluk MJ, Ashworth T, Wang H, et al. Gauging NOTCH1 Activation in Cancer Using Immunohistochemistry. PLoS One. 2013;8:e67306. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moskaluk CA, Baras AS, Mancuso SA, et al. Development and characterization of xenograft model systems for adenoid cystic carcinoma. Lab Invest. 2011;91:1480–90. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2011.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munster P, Eckhardt S, Patnaik A, et al. Safety and preliminary efficacy results of a first-in-human phase I study of the novel cancer stem cell (CSC) targeting antibody brontictuzumab (OMP-52M51, anti-Notch1) administered intravenously to patients with certain advanced solid tumors, AACR-NCI-EORTC International Conference on Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapeutics. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015 Suppl 2. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bell D, Hanna EY, Miele L, et al. Expression and significance of notch signaling pathway in salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2014;18:10–3. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frierson HF, Jr, Moskaluk CA. Mutation signature of adenoid cystic carcinoma: evidence for transcriptional and epigenetic reprogramming. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:2783–5. doi: 10.1172/JCI69070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Weert S, van der Waal I, Witte BI, et al. Histopathological grading of adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck: analysis of currently used grading systems and proposal for a simplified grading scheme. Oral Oncol. 2015;51:71–6. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zanotti S, Canalis E. Notch and the skeleton. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:886–96. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01285-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morell CM, Strazzabosco M. Notch signaling and new therapeutic options in liver disease. J Hepatol. 2014;60:885–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weber JM, Calvi LM. Notch signaling and the bone marrow hematopoietic stem cell niche. Bone. 2010;46:281–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nijjar SS, Wallace L, Crosby HA, et al. Altered Notch ligand expression in human liver disease: further evidence for a role of the Notch signaling pathway in hepatic neovascularization and biliary ductular defects. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:1695–703. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61116-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li L, Milner LA, Deng Y, et al. The human homolog of rat Jagged1 expressed by marrow stroma inhibits differentiation of 32D cells through interaction with Notch1. Immunity. 1998;8:43–55. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80457-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stoeck A, Lejnine S, Truong A, et al. Discovery of biomarkers predictive of GSI response in triple-negative breast cancer and adenoid cystic carcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2014;4:1154–67. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Puente XS, Pinyol M, Quesada V, et al. Whole-genome sequencing identifies recurrent mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Nature. 2011;475:101–5. doi: 10.1038/nature10113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thompson BJ, Buonamici S, Sulis ML, et al. The SCFFBW7 ubiquitin ligase complex as a tumor suppressor in T cell leukemia. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1825–35. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu Y, Cain-Hom C, Choy L, et al. Therapeutic antibody targeting of individual Notch receptors. Nature. 2010;464:1052–7. doi: 10.1038/nature08878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.