Abstract

Background

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) has been widely used to measure HIV effects on white matter (WM) microarchitecture. While many have reported reduced fractional anisotropy (FA) and increased mean diffusivity (MD) in HIV, quantitative inconsistencies across studies are large.

Purpose

To evaluate the consistency across studies of HIV effects on DTI measures and then examine DTI reliability in a longitudinal seropositive cohort.

Study Selection

The meta-analysis included 16 cross-sectional studies reporting FA and 12 studies reporting MD in the corpus callosum.

Data Analysis

Random effects meta-analysis was used to estimate study standardized mean differences (smd) and heterogeneity. DTI longitudinal reliability was estimated in seropositives studied before, and three and six months after, beginning treatment.

Data Synthesis

Meta-analysis revealed lower FA (smd −0.43; p<0.0001) and higher MD (smd 0.44; p<0.003) in seropositives. Nevertheless, between study heterogeneity accounted for 58% and 66% of the observed variance (p<0.01). In contrast, the longitudinal cohort FA was higher and MD lower in seropositives (both p<.0001) and FA and MD measures were highly stable over six months, with intra-class correlation coefficients all >0.96.

Limitation

Many studies pooled participants with varying treatments, ages and disease durations.

Conclusion

HIV effects on WM microstructure exhibited substantial variations that could result from acquisition, processing or cohort selection differences. When acquisition parameters and processing were carefully controlled, the resulting DTI measures did not show high temporal variation. HIV effects on WM microstructure may be age dependent. The high longitudinal reliability of DTI WM microstructure measures make them promising disease activity markers.

INTRODUCTION

The advent of combination anti-retroviral therapies (cART) for HIV has resulted in both increases in life expectancy and decreases in mortality1. While cART successfully controls HIV viremia and reconstitutes immune function2, the effects of persisting HIV infection and its treatments on brain structure and function are less clear. The incidence of HIV associated dementia declines following cART initiation3, and cART is sometimes associated with improved cognitive function4. Nevertheless, cognitive deficits can persist in treated HIV infection3, with some suggesting that the neuropsychological impairment pattern changes, rather than its prevalence5. Factors such as comorbidity burden, cognitive reserve, nadir T-helper (CD4) cell count and age, may also contribute to cognitive impairment6–9.

While CD4 cell count and viral load are generally used to diagnose infection and monitor treatment response, they do not necessarily reflect the direct and indirect brain effects of HIV infection. HIV enters the central nervous system (CNS) soon after infection10 and persists after treatment11. Before the cART era, CSF HIV RNA levels correlated with the severity of cognitive impairment12 and cART reduced CSF levels of HIV-1 RNA13. Nevertheless, with cART there is no strong association between cognitive impairment and concurrent CSF or peripheral viral load14 and several studies show that cognitive impairment may develop during viral suppression15–18.

Neuropsychological testing is often used to estimate HIV CNS effects, even though assessment is time intensive and possibly subject to practice effects19. Nevertheless, the HIV neuropsychological profile associated with cognitive impairment is debated5,9,20, suggesting that behavioral measures may not be optimal for measuring the ongoing CNS involvement.

The absence of measurable, consistent cognitive changes related to HIV disease activity motivates the search for objective biomarkers of the CNS effects of HIV infection. Histopathological evidence of HIV infection effects ranges from inflammation associated with gliosis and increased perivascular macrophages to degenerative pathology manifested as diffuse myelin pallor and axonal damage21,22. This evidence of white matter (WM) involvement has led to cross-sectional studies using diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) to study WM microarchitecture following HIV infection, with many finding decreased fractional anisotropy (FA)21,23–32 and increased mean diffusivity (MD)21,26,29,30,32,33 However, there have also been puzzling inconsistencies, with studies demonstrating results of opposite polarity, namely increased FA and decreased MD in the corpus callosum or other WM tracts30,31,33–35. To evaluate the utility of using WM microstructure measures for tracking the progression of HIV infection in the brain, it would be useful to have (1) consistency estimates of any serostatus effects across studies, and (2) temporal reliability estimates of these effects in individuals.

These issues prompted us to first do a meta-analysis of studies reporting callosal microstructure changes following HIV infection and then to examine the longitudinal stability of WM microstructural measures in seropositive participants prior to the initiation of cART and 3 and 6 months thereafter.

META-ANALYSIS MATERIALS AND METHODS

Meta-analysis of HIV effects in the corpus callosum

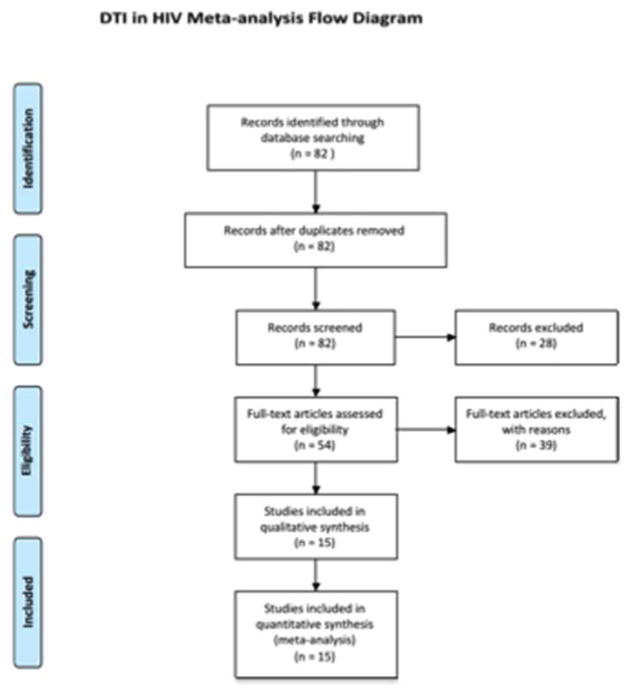

To summarize the literature on WM microstructure changes associated with HIV infection, we performed a computerized literature PubMed search on April 25, 2016, using the terms “("hiv"[MeSH Terms] OR "hiv") AND ("brain"[MeSH Terms] OR "brain"[All Fields]) AND ("diffusion tensor imaging"[MeSH Terms] OR ("diffusion"[All Fields] AND "tensor"[All Fields] AND "imaging"[All Fields]) OR "diffusion tensor imaging"[All Fields])”, yielding a total of 82 records. Of these, 28 studies were excluded because they: (1) studied participants not infected with HIV; (2) were performed in animal models; (3) were review papers; (4) were case reports; or (5) examined participants with perinatal HIV exposure who were not infected. Given the variability in the regions of interest (ROI) for which FA and MD were measured, we chose to focus on the corpus callosum, since it is the largest WM fiber tract in the brain and was the most frequent measurement target. Of the 54 eligible full text articles, a total of 16 cross sectional studies of HIV infected patients and controls that were completed between 2001 and 2016 were included in the meta-analysis, with 12 studies reporting both FA and MD values and 4 studies reporting only FA values. Because, three of the articles did not report complete FA and MD values, the results were obtained from the authors. The remaining studies were excluded because (1) numeric values for FA and MD were not reported for either seropositive or seronegative participants (authors of these papers were contacted in an effort to obtain the missing values); (2) only whole brain FA or MD were reported; (3) the studies examined the relationships of clinical variables, biomarkers or treatment on DTI measures without including a seronegative control group; (4) FA and MD were not measured in the corpus callosum; (5) prior published DTI data were used for fMRI connectivity analysis ROI selection, (6) a single case-control pair was reported; (7) the study focused on imaging measures other than diffusion parameters; or (8) the paper reported a new processing algorithm for DTI data (Figure 1). See Supplementary Material for excluded study references. Mean FA and MD values and their standard deviations were taken from the manuscript tables or the corresponding author was contacted if results were presented in a different form.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing selection of papers examining WM microstructure changes in HIV infection for meta-analysis 82

We used the R meta-analysis library meta36 to estimate the standardized mean difference (SMD) in FA or MD for each study and then calculated a weighted average of these estimates across studies. If multiple values for callosal subregions were reported in a study, we used their average in inverse-variance–weighted random-effects models estimating the mean effect and incorporating estimates of between-study variation in the weighting of each study. I2 was used to estimate study heterogeneity37,38. Study bias was explored by examining plots of sample size vs. effect size. Meta-regression was used to examine imaging protocol effects.

Meta-analysis of callosal regional variation in HIV serostatus effects

Eight of the selected studies reported FA, MD, axial diffusivity (AD) and radial diffusivity (RD) for callosal subregions, including the genu, body and splenium. As qualitative examination of the values revealed anatomical variation in diffusion measures, we carried out a separate repeated measures mixed effects regression analysis, examining regional and serostatus effects on callosal diffusion measures. If callosal microstructure exhibits regional variation, differential regional sampling across studies could result in high experimental error.

COMPARISON STUDY MATERIALS AND METHODS

To compare the meta-analysis serostatus effects to a new sample, and to characterize within-subject temporal variations in diffusion measures, we collected longitudinal DTI in seropositive participants prior to the initiation of cART and 3 and 6 months thereafter, comparing to a seronegative control group. After obtaining IRB approval and consent, a total of ten seropositive participants, 22–50 years of age, cART-naive but ready to begin antiretroviral therapy, were studied. Nine were followed longitudinally for six months. Participants who met DSM-IV criteria for substance dependence or abuse in the past six months, had other major psychiatric disorders, neurologic illnesses unrelated to HIV, MRI contraindications, cancer, hepatic disease, renal disease, cardiac disease or pulmonary disease, were excluded.

The serologic status of HIV participants was confirmed by positive HIV enzyme-linked immunoassay and Western blot or detection of plasma HIV RNA by PCR. Plasma viral load (VL), CD4+ and CD8 T cell counts were collected prior to initiation of cART and from 0.5 to 6.0 months after beginning therapy. Urine toxicology was collected prior to each imaging visit, testing for the presence of marijuana, cocaine, opiates, methamphetamines, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, and phencyclidine. Participants testing positive for any of these substances, with the exception of marijuana, were excluded.

For comparison, 12 seronegative participants 21–26 years of age were studied once. None of this group reported past or present symptoms of a major psychiatric or neurological disorder, head injury with loss of consciousness or were taking psychoactive medications.

To assess post-treatment cognitive and motor performance, participants were given a brief test battery for psychomotor function, dexterity, learning and memory skills, including the International HIV Dementia Scale39, Hopkins Verbal Learning Test40, HIV-Dementia Motor Scale41, Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale motor examination42 and Grooved Pegboard Test43.

Neuroimaging was performed using a 3.0 Tesla Verio MRI system (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) equipped with a 12-channel matrix head coil. We collected (1) a high-resolution, 3-dimensional, sagittal T1-weighted, magnetization-prepared rapid gradient echo scan (MPRAGE) scan (TR/TE/FA = 1600/2.5/9°, 256x256 matrix, 1 mm3 voxels; (2) a 2-dimensional multislice oblique axial T2-weighted fast spin echo (FSE) scan (TR/TE = 3000ms/85ms, 320x320 matrix, 5 mm3 voxels); and (3) DTI for WM microstructure assessment (2.0x2.0x2.2 mm voxels, TR/TE/FA = 14,700/95/90°, and 30 diffusion gradient directions with b values of 0 and 1000. Images were visually inspected at the time of scanning and a repeat scan performed if motion artifacts were observed.

DTI data were preprocessed with a script implementing gradient direction, head motion, and eddy-current correction using the FSL 5.0 Diffusion Toolbox (FDT)44 (http://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki/FDT). Quality assurance involved visual inspection of the individual images and elimination of corrupted images. After fitting a tensor model to the corrected diffusion data using FDT, FA, MD, RD and AD values were computed for all voxels.

The FA map for each subject was then aligned with an FA atlas FMRIB58_FA (www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/data/FMRIB58_FA) using the nonlinear registration tool FNIRT45. Next a mean FA image was created and thinned to create a mean FA skeleton representing the centers of all tracts common to the group. Then each subject's aligned FA data was then projected onto the mean skeleton. The skeleton creation steps are a part of the TBSS (Tract-Based Spatial Statistics46 procedure.

To increase the robustness of the measures and to facilitate the interpretation of the results, the different measures were averaged over the skeleton delimited by ROIs obtained from the ICBM-DTI-81 white-matter labels atlas47 previously aligned with the FNIRT procedure in the FMRIB58_FA common atlas, sampling the genu, body and splenium callosal subregions (Supplementary Figure 1).

META-ANALYSIS RESULTS

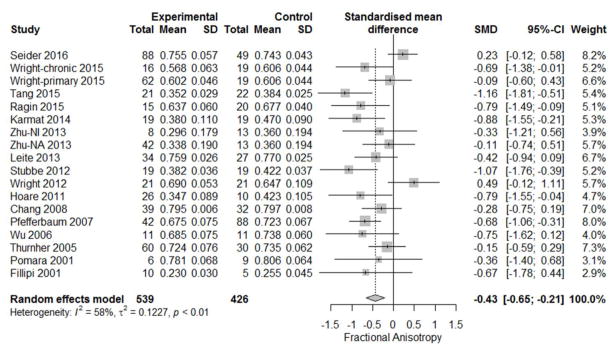

Meta-analysis of serostatus effects on callosal microstructure revealed a small reduction in FA (SMD=−0.43; CI −0.65 −0.21) related to serostatus (test of SMD=0: z=−3.82, p < 0.0001), study heterogeneity Q = 40.7; (d.f. = 17), p = 0.001 and I-squared (variation in SMD attributable to heterogeneity) = 58%. The Tau-squared estimate of between-study variance was 0.12. Eleven of the 16 studies had confidence intervals that included zero (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis results for HIV+ vs. HIV- comparisons of fractional anisotropy and mean diffusivity. (A) FA differences (SMD=−0.43; CI -0.65 −0.21; test of SMD=0: z=−3.82 p < 0.0001); (B) MD differences (SMD=+0.44; CI 0.15 0.72; test of SMD = 0: z = 3.00 p = 0.003)

Meta-analysis of MD revealed a significant increase (SMD=+0.44; CI 0.15 0.72) related to serostatus (test of SMD = 0: z = 3.00, p < 0.003), study heterogeneity Q = 38.4 (d.f. = 13), p = 0.0003 and I-squared = 66.0%. The estimate of between-study variance Tau-squared was 0.18 (Figure 2B). Therefore, meta-analysis of both FA and MD revealed a small, but statistically significant, change related to serostatus. Nevertheless, the observed high study heterogeneity suggests the existence of other unexplained experimental effects.

As both FA and MD serostatus group differences were associated with high between-study heterogeneity, it was possible that the observed group differences in WM microstructure resulted from variations in image acquisition parameters or biological variables. For image acquisition parameters reported by the constituent publications, mixed effects meta-regression revealed no significant effects on callosal FA and MD from variations in field strength (range 1.5–4 Tesla), voxel volume (range 1.5–20 mm3), and diffusion direction number (range 6–64). Mixed effects meta-regression also revealed no significant effects of the biological variables age (range 27–53) and CD4 count (range 211–678). In addition, there was no apparent trend in the DTI measures over the period spanned by the studies (2001–2016). Perhaps due to the relatively small sample of available studies, none of the variables examined appears to explain the high heterogeneity seen in the meta-analyses of FA or MD effects. Examination of funnel plots did not reveal asymmetries suggestive of bias.

To investigate the possibility that the high between-study heterogeneity arose from DTI processing variations, we coded studies according to whether the FSL/TBSS method was used, since it employs a unique step in which the FA maps are ‘skeletonized’ to reduce potential partial-volume effects. Meta-regression revealed a non-significant (p=0.08) trend for FSL/TBSS processing to be associated with higher FA values. Details of acquisition and processing for each study can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

Given some regional variation in measures, the observed between-study heterogeneity in callosal FA and MD group differences might also have resulted from sampling and combining diffusion measures from different callosal segments in different studies. To more closely examine callosal regional variations in FA and MD related to serostatus, we used repeated measures multilevel models with region and serostatus as fixed effects and study as a random effect in the 8 studies providing all 4 diffusion measures for 3 callosal subregions. For both FA and MD, we found significant regional effects, with the splenium having higher FA and lower MD than the body and splenium. Thus, the callosal region sampled appears to have a strong effect on group estimates of WM microstructure (Supplementary Results, Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Figures 1 and 2).

COMPARISON STUDY RESULTS

For comparison with the meta-analysis, we collected DTI data from seropositive and seronegative participants for cross-sectional and longitudinal examination of WM microstructure changes.

Nine of 10 seropositive participants in our sample successfully completed three imaging visits, and 12 seronegative controls completed one visit. Although the mean age for our seropositive subjects (30.7 ± 9.5) was greater than that of controls (23.3 ± 1.8), age variations over this range are not known to result in variation in diffusion measures48, a finding consonant with the negative age meta-regression results reported above. While we would expect that the slightly older age of our seropositive cohort could potentially decrease FA, this was not observed. Seropositive participants had fewer years of education (11.9 ± 2.0) than controls (17.2 ± 1.7). On entry into the study, six of the nine participants were seropositive during screening for sexually transmitted disease. The other three participants had signs and symptoms of clinical AIDS, with all three presenting with Pneumocystis pneumonia, and one additionally having herpes zoster and esophageal candidiasis.

Seropositive participants began cART immediately after their first visit. All nine seropositive participants were treated with at least 3 anti-retroviral medications, including nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor and a nucleoside analog that were taken in combination with non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors or an integrase inhibitor. The CNS penetration effectiveness (CPE) rank of each participant’s cART regimen was calculated based on a modified version of the CPE that includes rilpivirine (personal communication, S. Letendre, 1/14/15). Six participants were on regimens with a CPE rank of 6, and 3 participants had a CPE rank of 7, one of whom switched to a regimen with a rank of 6 after 4 months of therapy, and then to one with a rank of 8 after 5 months.

Laboratory testing included serial CD4+/CD8+ T cell counts and viral load, both assessed prior to initiation of cART, and from 0.5–6.0 months after the initiation of cART (Supplementary Table 3). Over 24 weeks of therapy, seropositive participants averaged CD4 cell count increases of 6.8 cells/week (p<.001), and accompanying decreases in log viral load (p<.001), with no change in CD8 cell counts (p=.64). These results are typical responses to cART.

Behavioral assessments revealed that, while none of our subjects met criteria for HIV dementia, a few exhibited mild to moderate degrees of impairment in verbal learning, with some subjects exhibiting mild degrees of impairment in motor function (Supplementary Table 4).

Although HIV infection can result in macroscopic changes in WM, visual inspection of the T1- and T2-weighted images revealed that our participants were generally free of these effects. One seropositive participant exhibited a mild degree of T2 prolongation in periatrial WM bilaterally. T1- and T2-weighted images were otherwise unrevealing, with no parenchymal lesions, ventriculomegaly or brain atrophy of the sort that were frequently reported prior to the widespread introduction of cART49,50.

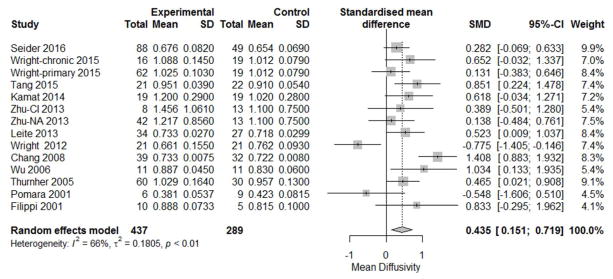

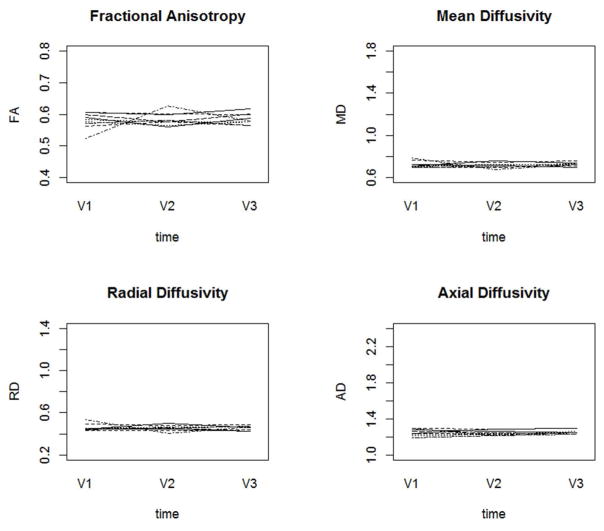

To examine the regional pattern of diffusion changes following HIV infection, but before treatment was begun, we compared the seropositive pre-treatment ROI values to the seronegative control values, using repeated measures multilevel models treating serostatus and hemisphere (left hemisphere, midline and right hemisphere) as fixed effects and subject and ROI as random effects. With FA as the dependent measure, the seropositive group had higher FA values (F(2,21.06) = 14.31, p = 0.0011). FA values were also higher in the midline than the hemispheres (F(2,707.98) = 10.92, p < 0.0001) (Figure 3A). With MD as the dependent measure, the seropositive group had lower MD (F(1,76.23) = 18.45, p < 0.0001). MD values were also higher in the midline compared to the hemispheres (F(2,81.52) = 31.31, p < 0.0001), with a significant serostatus by hemisphere interaction (F(2,81.52) = 3.31, p = 0.042) (Figure 3B). For RD, we found an effect of serostatus, with the seropositive group showing lower values (F(1,17.40) = 15.16, p < 0.0001) and an effect of hemisphere (F(2,87.58) = 11.37, p < 0.0001), with the midline having higher RD than the hemispheres. There was also a significant serostatus by hemisphere interaction (F(2,87.58) = 3.77, p = 0.027) (Figure 3C). For AD, we found an effect of serostatus (F(1,92.12) = 7.03, p = 0.0095), with the seropositive group exhibiting lower AD, and an effect of hemisphere (F(2,98.73) = 0.30, p < 0.0001), with the midline showing higher values than the hemispheres (Figure 3D). Thus, compared to seronegative controls, in the seropositive group we observed higher FA, lower MD, lower RD, and lower AD.

Figure 3.

Differences in FA, MD, RD and AD measures in the comparison group seronegative (CNTL) and seropositive (HIV) participants following HIV infection, but before treatment was started. Seropositive participants had higher FA, lower MD, lower RD and lower AD. Measurements from 28 white-matter ROIs were aggregated into left hemisphere (L), midline (MID) and right hemisphere (R) regions.

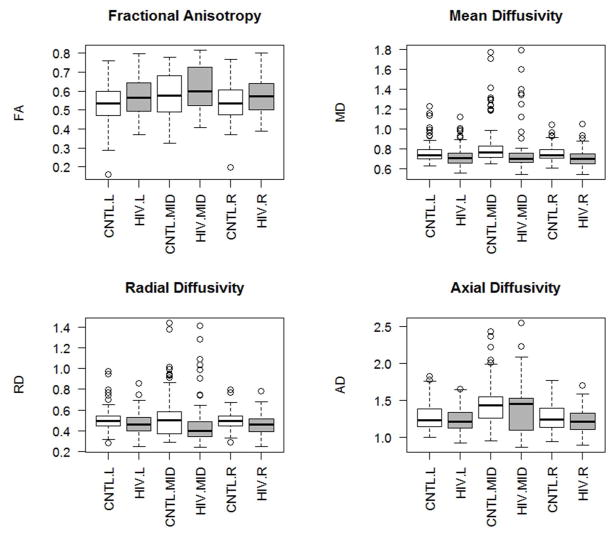

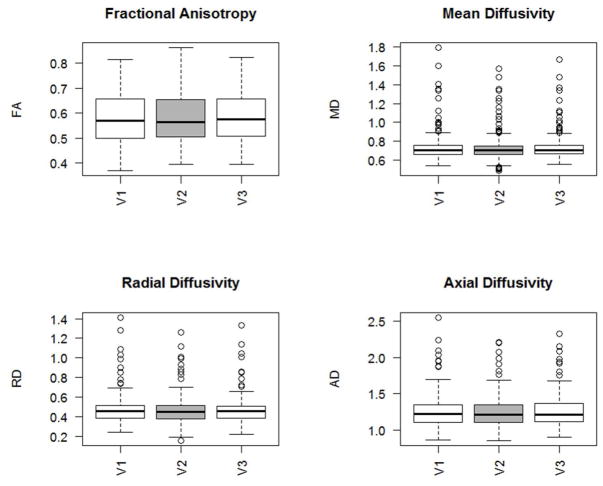

To examine the within subject reliability of FA, MD, RD and AD measures, we examined temporal variation in the four diffusion measures over 6 months using a two-way random effects ICC model. Averaging across all 28 WM sampling regions, we observed excellent internal consistency, with Cronbach's alpha scores for FA = 0.91, MD = 0.96, AD = 0.98, and RD = 0.96. Cronbach's alpha indicates the degree to which items measure a single unidimensional latent variable. ICC estimates were also high, with FA ICC = 0.97 (0.96–0.97 95%CI), MD = 0.96 (0.96–.97 95%CI), AD = 0.98 (0.98–.99 95%CI), and RD = 0.96 (0.95–.97 95%CI) (Figure 4A). In addition, examination of individual subject time plots of FA, MD, RD and AD revealed that all subjects exhibited consistent mean WM architecture estimates across time (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

A. FA, MD, RD and AD in seropositive participants following HIV infection, but before treatment was started. Measurements are aggregated across 28 white-matter ROIs83. Data were collected pre-treatment (V1), 3 months later (V2) and 6 months later (V3). B. Individual time plots of FA, MD, RD and AD in seropositive participants following HIV infection.

DISCUSSION

Summary of results

Meta-analysis of HIV effects on WM microstructure revealed relatively small changes in FA and MD related to serostatus and high between-study heterogeneity. Variation in image acquisition parameters across studies did not explain the high heterogeneity. More detailed examination of callosal WM microstructure measures revealed regional variations that could contribute to between-study differences if the same callosal regions were not sampled in each study. In our comparison study, HIV infection was associated with widespread changes in WM microstructure, with increases in FA and decreases in MD, RD and AD. Over a six month span these measures exhibited excellent reliability, suggesting that within-subject experimental variation does not contribute substantially to high between-study heterogeneity.

HIV effects on white matter microstructure

HIV infection affects cerebral WM through a range of mechanisms. Histopathological evidence includes inflammation associated with gliosis, increased numbers of perivascular macrophages and a type of degenerative pathology, manifested as myelin pallor22, that is thought to result from breakdown of the blood-brain barrier with resulting vasogenic edema51. WM metabolite alterations detected with MR spectroscopy parallel those seen in subcortical gray matter, including elevated Ch/Cr, elevated Mi/Cr, and decreased NAA/Cr ratios52, with these metabolite differences increasing with disease progression53. Macrostructural evidence of HIV infection includes cerebral WM volume loss54 and focal hyperintensities seen with T2-weighted imaging55.

DTI reveals changes associated with seropositivity, believed to reflect WM injury from both direct or indirect effects of infection21,23–25,27–30,32,33,56,57. While these studies have generally found elevated MD and reduced FA in the WM of seropositive participants relative to controls, results vary among the published accounts. These inconsistencies could arise from a number of sources, including pooling observations from both treated and untreated participants24–27,29–31,58,59, diffusion imaging protocol variations, study sample variations in duration of infection, age, premorbid and comorbid substance use, comorbid illness such as hepatitis, length and effectiveness of anti-retroviral therapy treatment, CNS medication penetration, CD4+ nadir, premorbid Intelligence, and ethnicity.

Meta-analysis of HIV effects on white matter microstructure

Meta-analysis of HIV DTI studies revealed wide variation in seropositivity effects on diffusion parameter estimates. If DTI is ever to be used as a diagnostic marker for HIV infection, high consistency in regional measurements will be required. In addition, there are growing concerns about the reproducibility and reliability of biomedical research60,61, prompting the National Institutes of Health to focus on initiatives to reduce the frequency and severity of irreproducibility61. There are many potential sources for the study heterogeneity effects we observed.

The specific choice of MRI acquisition parameters, with related SNR variation, might bias measurements of diffusion measures, particularly in higher magnetic fields62,63. Nevertheless, meta-regression of acquisition parameters across studies did not account for variation in diffusion measures, suggesting that the range of SNR values arising from variation in voxel volume, field strength and diffusion direction number, did not strongly influence FA and MD estimates. Keeping acquisition parameters constant in the comparison study, we observed high within-subject reproducibility across time.

While differences in DTI data processing techniques may contribute to diffusion measure heterogeneity63,64, many of the studies included in the meta-analysis did not report data processing details in sufficient detail to examine their specific effects using meta-regression or subgroup analysis. Nevertheless, we were able to compare the effects of using DTI processing methods that involved skeletonization of diffusion parameter maps to those that did not and observed a trend for FA values to be higher when FSL/TBSS style processing was used. The skeletonization step that is a unique aspect of TBSS results in voxel selections that are more likely to contain pure WM, thereby suffering less contamination from partial volume effects that might be expected to reduce the apparent directionality of diffusion. This preliminary finding will be explored in a subsequent subject-level meta-analysis of the effects of processing strategy on diffusion parameter estimates in HIV.

While HIV globally affects WM, regional variations in myelination, axon orientation, packing density and membrane permeability may affect regional measurements63. Meta-analysis of callosal diffusion measures revealed regional variability, with FA consistently highest in the splenium. Therefore, between-study variation in selection of subsequently aggregated sampling regions could result in higher between-study heterogeneity.

Differences in cohort characteristics, such as duration of infection, age, premorbid and comorbid substance use, comorbid illness such as hepatitis, length and effectiveness of treatment with anti-retroviral therapy, CNS penetration effectiveness of cART regimen, nadir CD4+, premorbid Intelligence, and ethnicity, may also contribute to lack of reproducibility. Many studies in our meta-analysis excluded subjects with current drug or alcohol use, but premorbid drug or alcohol use was often not addressed. Chronic alcoholism has been shown to reduce the corpus callosum FA65,66,29. Studies have also shown corpus callosum FA decreases following cocaine67, methamphetamine68 and opiate use69.

WM microstructure cross-sectional studies have shown that FA is lower and MD higher in older compared with younger adults70,71. More recently, annual decreases in FA and annual increases in MD, AD and RD have been shown in a longitudinal healthy cohort, with changes beginning in the fifth decade48. While we found no evidence for age effects in our meta-analysis, the maximum mean age in these studies was below the age when WM microstructural changes generally begin, highlighting the need to further explore age effects in older HIV patients.

Anti-retroviral treatments may be injurious to brain cellular elements. To our knowledge, there are no studies examining the effects of cART regimen CPE on WM microstructure. Nevertheless, in a study comparing simple motor task performance in seropositive participants on low and high CPE cART regimens, the fMRI response amplitude was significantly greater in the low-CPE group compared to the high-CPE or seronegative groups74, suggesting that treatment effects should be explored in future meta-analytic studies using subject level data.

Two studies in the meta-analysis included HIV infected participants with hepatitis27,35 and several studies did not list co-morbidities such as chronic liver or renal disease as exclusionary criteria. Hepatitis C co-infection is found in 25–30% of HIV infected individuals75 and has been associated with reduced FA and increased MD in WM, including the corpus callosum76.

Finally, 10 of the 16 studies enrolled patients with longer infection duration than the subjects enrolled in our comparison study. Although the relationship between HIV infection duration and DTI measures is rarely addressed, infection duration can be negatively associated with callosal FA77.

The effects of many of the study characteristics discussed above are difficult to explore using meta-regression, as aggregating individual subject variables can result in ecological bias in the resulting parameter estimates78. Although it was not possible to explore these biological effects using the tools of study-level meta-analysis, it is very likely that many of these variables contributed strongly to the high observed between-study heterogeneity, motivating further exploration of potential modulating effects of biological variables using datasets incorporating subject-level measures.

Comparison study results

Our study found globally reduced MD and elevated FA in the WM of HIV infected participants who were naive to anti-retroviral therapy. Other studies have reported increased FA values and decreased MD, AD, RD for multiple corpus callosum regions and the centrum semiovale in cART naive seropositive participants compared with seronegative controls30,34 Since cellular membranes hinder water diffusion79, activation of microglia, astrocytes and perivascular macrophages associated with early CNS HIV infection may have caused reduced MD and increased FA in our seropositive cohort80. As many of the studies in the meta-analysis included patients with longer infection duration than our subjects, the shorter infection duration in our sample might have resulted in different changes in diffusion parameters. Studies reporting higher FA in the seropositive group34,35 included participants with shorter disease durations. The earlier phases of HIV infection might be associated with more robust neuroinflammatory changes, causing diffusion restriction effects resulting in higher FA and lower MD. On examining the details of the studies that agreed with our findings, we noted that they studied younger samples, many of whom were untreated at the time of imaging, as in our pilot longitudinal study. There is evidence of an age by HIV serostatus interaction, evidenced by higher FA and lower MD in younger individuals and lower FA and higher MD in older individuals in the posterior limbs of the internal capsules, cerebral peduncles, and anterior corona radiata35. As most of the studies in the meta-analysis included samples with higher average ages, we believe that this age/serostatus interaction may explain the seeming contradictory results across studies. Unfortunately, we are unable to statistically confirm this explanation given the study-level data sources used for this meta-analysis. Nevertheless, the biological interactions among age, serostatus and WM microstructure is a topic that might be profitably explored in subsequent meta-analyses based on subject-level data.

WM microstructure measures were examined in our seropositive participants at three months and six months after the initiation of cART, demonstrating excellent reliability. We attribute these persistent alterations in WM microstructure, despite the initiation of cART, to the presence of continued activation of microglia and macrophages, as this form of continuing inflammation during cART has been documented histologically81.

Global temporal stability of DTI measures was observable at the single subject level, suggesting that the heterogeneity observed in the meta-analysis did not arise because of random temporal fluctuations in the measurement process. It is possible that use of more uniform imaging protocols and data processing pipelines across studies will improve between study reproducibility.

Conclusions

Meta-analysis of DTI results from studies examining the effects of HIV serostatus on WM microstructure revealed high between-study heterogeneity and relatively small changes in measures. Regional variation in callosal WM architecture could contribute to between-study differences if the same callosal regions are not combined for total callosal estimates. In a longitudinal comparison sample, we observed widespread changes related to seropositivity in WM microstructure, with increases in FA, and decreases in MD, RD and AD. Effects of HIV infection on WM microstructure may be age dependent, related to more prominent neuroinflammatory changes in younger patients. Examination of measures averaged over all brain WM structures over a six month span revealed excellent reliability, suggesting that within-subject variation does not substantially contribute to the observed between-study variability. Further work will be required to isolate the sources of variation in WM microstructure estimates in HIV seropositive groups.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by the Comprehensive NeuroAIDS Center (NIH grant P30MH0921777). We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Drs. Schiffito, Wright, Seider and Cohen for providing values not given in the original manuscripts.

Abbreviations

- MD

mean diffusivity

- cART

combination anti-retroviral therapy

- CNS

central nervous system

- ROI

region of interest

- SMD

standardized mean difference

- AD

axial diffusivity

- RD

radial diffusivity

- CPE

clinical penetration effectiveness

References

- 1.Lima VD, Hogg RS, Harrigan PR, et al. Continued improvement in survival among HIV-infected individuals with newer forms of highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS (London, England) 2007;21(6):685–692. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32802ef30c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hammer SM, Squires KE, Hughes MD, et al. A controlled trial of two nucleoside analogues plus indinavir in persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection and CD4 cell counts of 200 per cubic millimeter or less. New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;337(11):725–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709113371101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simioni S, Cavassini M, Annoni J-M, et al. Cognitive dysfunction in HIV patients despite long-standing suppression of viremia. AIDS (London, England) 2010;24(9):1243–1250. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283354a7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen RA, Boland R, Paul R, et al. Neurocognitive performance enhanced by highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected women. AIDS (London, England) 2001;15(3):341–345. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200102160-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cysique LA, Maruff P, Brew BJ. Prevalence and pattern of neuropsychological impairment in human immunodeficiency virus–infected/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) patients across pre-and post-highly active antiretroviral therapy eras: a combined study of two cohorts clinical report. Journal of neurovirology. 2004;10(6):350–357. doi: 10.1080/13550280490521078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giancola ML, Lorenzini P, Balestra P, et al. Neuroactive antiretroviral drugs do not influence neurocognitive performance in less advanced HIV-infected patients responding to highly active antiretroviral therapy. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2006;41(3):332–337. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000197077.64021.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tozzi V, Balestra P, Bellagamba R, et al. Persistence of neuropsychologic deficits despite long-term highly active antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV-related neurocognitive impairment: prevalence and risk factors. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2007;45(2):174–182. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318042e1ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maki PM, Rubin LH, Valcour V, et al. Cognitive function in women with HIV Findings from the Women's Interagency HIV Study. Neurology. 2015;84(3):231–240. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heaton RK, Franklin DR, Ellis RJ, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders before and during the era of combination antiretroviral therapy: differences in rates, nature, and predictors. Journal of neurovirology. 2011;17(1):3–16. doi: 10.1007/s13365-010-0006-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gray F, Scaravilli F, Everall I, et al. Neuropathology of early HIV – 1 infection. Brain pathology. 1996;6(1):1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1996.tb00775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jellinger K, Setinek U, Drlicek M, Bohm G, Steurer A, Lintner F. Neuropathology and general autopsy findings in AIDS during the last 15 years. Acta neuropathologica. 2000;100(2):213–220. doi: 10.1007/s004010000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan P, Brew BJ. HIV associated neurocognitive disorders in the modern antiviral treatment era: prevalence, characteristics, biomarkers, and effects of treatment. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2014;11(3):317–324. doi: 10.1007/s11904-014-0221-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marra CM, Zhao Y, Clifford DB, et al. Impact of combination antiretroviral therapy on cerebrospinal fluid HIV RNA and neurocognitive performance. AIDS (London, England) 2009;23(11):1359. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832c4152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vitiello B, Goodkin K, Ashtana D, et al. HIV-1 RNA concentration and cognitive performance in a cohort of HIV-positive people. AIDS (London, England) 2007;21(11):1415–1422. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328220e71a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robertson KR, Smurzynski M, Parsons TD, et al. The prevalence and incidence of neurocognitive impairment in the HAART era. AIDS (London, England) 2007;21(14):1915–1921. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32828e4e27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cysique LA, Brew BJ. Prevalence of non-confounded HIV-associated neurocognitive impairment in the context of plasma HIV RNA suppression. Journal of neurovirology. 2011;17(2):176–183. doi: 10.1007/s13365-011-0021-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cysique LA, Maruff P, Brew BJ. Variable benefit in neuropsychological function in HIV-infected HAART-treated patients. Neurology. 2006;66(9):1447–1450. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000210477.63851.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sevigny J, Albert S, McDermott M, et al. Evaluation of HIV RNA and markers of immune activation as predictors of HIV-associated dementia. Neurology. 2004;63(11):2084–2090. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000145763.68284.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grund B, Wright EJ, Brew BJ, et al. Improved neurocognitive test performance in both arms of the SMART study: impact of practice effect. Journal of neurovirology. 2013;19(4):383–392. doi: 10.1007/s13365-013-0190-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woods SP, Moore DJ, Weber E, Grant I. Cognitive neuropsychology of HIVassociated neurocognitive disorders. Neuropsychology review. 2009;19(2):152–168. doi: 10.1007/s11065-009-9102-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thurnher MM, Castillo M, Stadler A, Rieger A, Schmid B, Sundgren PC. Diffusion–tensor MR imaging of the brain in human immunodeficiency virus– positive patients. American journal of neuroradiology. 2005;26(9):2275– 2281. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Budka H. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-induced disease of the central nervous system: pathology and implications for pathogenesis. Acta neuropathologica. 1989;77(3):225–236. doi: 10.1007/BF00687573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leite SC, Correa DG, Doring TM, et al. Diffusion tensor MRI evaluation of the corona radiata, cingulate gyri, and corpus callosum in HIV patients. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2013;38(6):1488–1493. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ragin AB, Wu Y, Gao Y, et al. Brain alterations within the first 100 days of HIV infection. Annals of clinical and translational neurology. 2015;2(1):12–21. doi: 10.1002/acn3.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamat R, Brown GG, Bolden K, et al. Apathy is associated with white matter abnormalities in anterior, medial brain regions in persons with HIV infection. Journal of clinical and experimental neuropsychology. 2014;36(8):854–866. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2014.950636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu T, Zhong J, Hu R, et al. Patterns of white matter injury in HIV infection after partial immune reconstitution: a DTI tract-based spatial statistics study. Journal of neurovirology. 2013;19(1):10–23. doi: 10.1007/s13365-012-0135-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stubbe-Drger B, Deppe M, Mohammadi S, et al. Early microstructural white matter changes in patients with HIV: a diffusion tensor imaging study. BMC neurology. 2012;12(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-12-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoare J, Fouche J-P, Spottiswoode B, et al. White-matter damage in clade C HIV-positive subjects: a diffusion tensor imaging study. The Journal of neuropsychiatry and clinical neurosciences. 2011 doi: 10.1176/jnp.23.3.jnp308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pfefferbaum A, Rosenbloom MJ, Adalsteinsson E, Sullivan EV. Diffusion tensor imaging with quantitative fibre tracking in HIV infection and alcoholism comorbidity: synergistic white matter damage. Brain. 2007;130(1):48–64. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pomara N, Crandall DT, Choi SJ, Johnson G, Lim KO. White matter abnormalities in HIV-1 infection: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2001;106(1):15–24. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(00)00082-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Filippi CG, Uluğ AM, Ryan E, Ferrando SJ, van Gorp W. Diffusion tensor imaging of patients with HIV and normal-appearing white matter on MR images of the brain. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 2001;22(2):277–283. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wright PW, Vaida FF, Fernandez RJ, et al. Cerebral white matter integrity during primary HIV infection. AIDS (London, England) 2015;29(4):433–442. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang L, Wong V, Nakama H, et al. Greater than age-related changes in brain diffusion of HIV patients after 1 year. Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology. 2008;3(4):265–274. doi: 10.1007/s11481-008-9120-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wright P, Heaps J, Shimony JS, Thomas JB, Ances BM. The effects of HIV and combination antiretroviral therapy on white matter integrity. AIDS (London, England) 2012;26(12):1501. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283550bec. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seider TR, Gongvatana A, Woods AJ, et al. Age exacerbates HIV-associated white matter abnormalities. J Neurovirol. 2016;22(2):201–212. doi: 10.1007/s13365-015-0386-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwarzer G, Carpenter JR, Rucker G. Meta-analysis with R. Springer; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Bmj. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Higgins J, Thompson SG. Controlling the risk of spurious findings from meta – regression. Statistics in medicine. 2004;23(11):1663–1682. doi: 10.1002/sim.1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sacktor NC, Wong M, Nakasujja N, et al. The International HIV Dementia Scale: a new rapid screening test for HIV dementia. AIDS (London, England) 2005;19(13):1367–1374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brandt J. The Hopkins Verbal Learning Test: Development of a new memory test with six equivalent forms. The Clinical Neuropsychologist. 1991;5(2):125–142. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Robinson-Papp J, Byrd D, Mindt MR, Oden NL, Simpson DM, Morgello S. Motor function and human immunodeficiency virus–associated cognitive impairment in a highly active antiretroviral therapy–era cohort. Archives of neurology. 2008;65(8):1096–1101. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.8.1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fahn S, Elotion R UPDRS Program Members. Florham Park. Vol. 2. NJ: Macmillan Healthcare Information; 1987. Unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Trites R. Grooved pegboard test. Lafayette, Ind: Lafayette Instrument; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, et al. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. Neuroimage. 2004;23(Suppl 1):S208–219. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Andersson JL, Jenkinson M, Smith S. Non-linear registration, aka Spatial normalisation FMRIB technical report TR07JA2. FMRIB Analysis Group of the University of Oxford. 2007;2 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Johansen-Berg H, et al. Tract-based spatial statistics: voxelwise analysis of multi-subject diffusion data. Neuroimage. 2006;31(4):1487–1505. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mori S, Wakana S, Van Zijl PC, Nagae-Poetscher L. MRI atlas of human white matter. Elsevier; 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sexton CE, Walhovd KB, Storsve AB, et al. Accelerated changes in white matter microstructure during aging: a longitudinal diffusion tensor imaging study. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2014;34(46):15425–15436. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0203-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Broderick DF, Wippold FJ, 2nd, Clifford DB, Kido D, Wilson BS. White matter lesions and cerebral atrophy on MR images in patients with and without AIDS dementia complex. AJR American journal of roentgenology. 1993;161(1):177–181. doi: 10.2214/ajr.161.1.8517298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jarvik JG, Hesselink JR, Kennedy C, et al. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Magnetic resonance patterns of brain involvement with pathologic correlation. Arch Neurol. 1988;45(7):731–736. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1988.00520310037014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Power C, Kong PA, Crawford TO, et al. Cerebral white matter changes in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome dementia: alterations of the bloodbrain barrier. Annals of neurology. 1993;34(3):339–350. doi: 10.1002/ana.410340307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chang L, Ernst T, Leonido-Yee M, Walot I, Singer E. Cerebral metabolite abnormalities correlate with clinical severity of HIV-1 cognitive motor complex. Neurology. 1999;52(1):100–108. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mohamed MA, Barker PB, Skolasky RL, et al. Brain metabolism and cognitive impairment in HIV infection: a 3-T magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Magnetic resonance imaging. 2010;28(9):1251–1257. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cardenas VA, Meyerhoff DJ, Studholme C, et al. Evidence for ongoing brain injury in human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients treated with antiretroviral therapy. J Neurovirol. 2009;15(4):324–333. doi: 10.1080/13550280902973960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McArthur JC, Kumar AJ, Johnson DW, et al. Incidental white matter hyperintensities on magnetic resonance imaging in HIV-1 infection. Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 1990;3(3):252–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ragin AB, Wu Y, Storey P, Cohen BA, Edelman RR, Epstein LG. Diffusion tensor imaging of subcortical brain injury in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Journal of neurovirology. 2005;11(3):292–298. doi: 10.1080/13550280590953799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ragin A, Storey P, Cohen B, Edelman R, Epstein L. Disease burden in HIVassociated cognitive impairment A study of whole-brain imaging measures. Neurology. 2004;63(12):2293–2297. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000147477.44791.bd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang B, Liu Z, Liu J, Tang Z, Li H, Tian J. Gray and white matter alterations in early HIV-infected patients: Combined voxel-based morphometry and tractbased spatial statistics. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging : JMRI. 2015 doi: 10.1002/jmri.25100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tang VM, Lang DJ, Giesbrecht CJ, et al. White matter deficits assessed by diffusion tensor imaging and cognitive dysfunction in psychostimulant users with comorbid human immunodeficiency virus infection. BMC research notes. 2015;8:515. doi: 10.1186/s13104-015-1501-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McNutt M. Journals unite for reproducibility. Science (New York, NY) 2014;346(6210):679. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Collins FS, Tabak LA. Policy: NIH plans to enhance reproducibility. Nature. 2014;505(7485):612–613. doi: 10.1038/505612a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Papinutto ND, Maule F, Jovicich J. Reproducibility and biases in high field brain diffusion MRI: An evaluation of acquisition and analysis variables. Magnetic resonance imaging. 2013;31(6):827–839. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jones DK, Knosche TR, Turner R. White matter integrity, fiber count, and other fallacies: the do's and don'ts of diffusion MRI. Neuroimage. 2013;73:239–254. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.06.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vollmar C, O'Muircheartaigh J, Barker GJ, et al. Identical, but not the same: intra-site and inter-site reproducibility of fractional anisotropy measures on two 3.0T scanners. Neuroimage. 2010;51(4):1384–1394. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.03.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pfefferbaum A, Sullivan EV. Microstructural but not macrostructural disruption of white matter in women with chronic alcoholism. Neuroimage. 2002;15(3):708–718. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pfefferbaum A, Sullivan EV, Hedehus M, Adalsteinsson E, Lim KO, Moseley M. In vivo detection and functional correlates of white matter microstructural disruption in chronic alcoholism. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24(8):1214–1221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ma L, Hasan KM, Steinberg JL, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging in cocaine dependence: regional effects of cocaine on corpus callosum and effect of cocaine administration route. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2009;104(3):262–267. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tobias MC, O’Neill J, Hudkins M, Bartzokis G, Dean AC, London ED. Whitematter abnormalities in brain during early abstinence from methamphetamine abuse. Psychopharmacology. 2010;209(1):13–24. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1761-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bora E, Yucel M, Fornito A, et al. White matter microstructure in opiate addiction. Addiction biology. 2012;17(1):141–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2010.00266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pagani E, Agosta F, Rocca MA, Caputo D, Filippi M. Voxel-based analysis derived from fractional anisotropy images of white matter volume changes with aging. Neuroimage. 2008;41(3):657–667. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nusbaum AO, Tang CY, Buchsbaum MS, Wei TC, Atlas SW. Regional and global changes in cerebral diffusion with normal aging. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 2001;22(1):136–142. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Haasz J, Westlye ET, Fjar S, Espeseth T, Lundervold A, Lundervold AJ. General fluid-type intelligence is related to indices of white matter structure in middle-aged and old adults. Neuroimage. 2013;83:372–383. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Malpas CB, Genc S, Saling MM, Velakoulis D, Desmond PM, O'Brien TJ. MRI correlates of general intelligence in neurotypical adults. Journal of clinical neuroscience : official journal of the Neurosurgical Society of Australasia. 2016;24:128–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2015.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ances BM, Roc AC, Korczykowski M, Wolf RL, Kolson DL. Combination antiretroviral therapy modulates the blood oxygen level–dependent amplitude in human immunodeficiency virus–seropositive patients. Journal of neurovirology. 2008;14(5):418–424. doi: 10.1080/13550280802298112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Alter MJ. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and HIV co-infection. Journal of hepatology. 2006;44:S6–S9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bladowska J, Zimny A, Knysz B, et al. Evaluation of early cerebral metabolic, perfusion and microstructural changes in HCV-positive patients: a pilot study. Journal of hepatology. 2013;59(4):651–657. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Heaps-Woodruff JM, Wright PW, Ances BM, Clifford D, Paul RH. The impact of human immune deficiency virus and hepatitis C coinfection on white matter microstructural integrity. J Neurovirol. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s13365-015-0409-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Berlin JA, Santanna J, Schmid CH, Szczech LA, Feldman HI. Individual patientversus group-level data meta-regressions for the investigation of treatment effect modifiers: ecological bias rears its ugly head. Stat Med. 2002;21(3):371–387. doi: 10.1002/sim.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Alexander AL, Lee JE, Lazar M, Field AS. Diffusion tensor imaging of the brain. Neurotherapeutics. 2007;4(3):316–329. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hong S, Banks WA. Role of the immune system in HIV-associated neuroinflammation and neurocognitive implications. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2015;45:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Anthony IC, Ramage SN, Carnie FW, Simmonds P, Bell JE. Influence of HAART on HIV-related CNS disease and neuroinflammation. Journal of neuropathology and experimental neurology. 2005;64(6):529–536. doi: 10.1093/jnen/64.6.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS medicine. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Oishi K, Faria AV, van Zijl PC, Mori S. MRI atlas of human white matter. Academic Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.