Abstract

Undergraduates (n = 274) participated in a week-long daily-life experience-sampling study of mind-wandering after being assessed for executive-control abilities (working memory capacity [WMC], attention-restraint ability, attention-constraint ability, propensity for task-unrelated thoughts [TUTs]) and personality traits. Electronic devices probed subjects 8 times/day about their current thoughts and context. WMC and attention abilities predicted laboratory TUTs, but they only predicted daily-life mind-wandering as a function of subjects’ momentary attempts to concentrate. This pattern replicates prior daily-life findings but conflicts with laboratory findings. Personality factors also yielded divergent lab-life associations: Only neuroticism predicted laboratory TUTs but only openness predicted daily-life mind-wandering (both predicted daily-life mind-wandering content). Cognitive and personality factors also predicted dimensions of everyday thought other than mind-wandering, such as subjective controllability. Mind-wandering in people’s daily environments has different correlates (and perhaps causes) than TUTs during controlled and artificial laboratory tasks. Thus, mind-wandering theories based solely on lab phenomena may be incomplete.

Keywords: mind-wandering, executive control, experience sampling, personality

“…before experimenting, isn’t it appropriate to know as exactly as possible on what one is going to experiment?”

(Sartre, 1936, p. 127).

Mind-wandering is a subjective, typically spontaneous experience, yet psychologists and neuroscientists conduct most mind-wandering research under directed, controlled laboratory conditions. Subjects undertake a task that is periodically interrupted by thought probes asking them to report whether their immediately preceding thoughts were on- or off-task. This empirical strategy helps illuminate how mind-wandering affects performance or individual differences in theoretically important laboratory tasks (e.g., McVay & Kane, 2012a; 2012b). But is it suitable for exploring the nature of mind-wandering as it typically unfolds in human experience? Whereas the laboratory seems like a neutral and controlled context to researchers, it is a uniquely strange place to participants and may ironically create idiosyncratic irregularities in their behavior and experiences (Rubin, 1989). This study expands on prior findings to show that — regarding individual differences — the laboratory biases our perspective on mind-wandering.

In a 2007 study of “feral cognition,” Kane and colleagues used daily-life experience-sampling methods (ESM) to determine whether cognitive abilities predicted undergraduates’ subjective experiences in the moment. They found that variation in working memory capacity (WMC; measured by three tasks) didn’t correlate with overall mind-wandering rates, but it interacted with the demands of the environment. Only when students reported trying hard to concentrate, or when their activity felt cognitively demanding, did those with higher WMC mind-wander less than those with lower WMC. Kane et al. (2007) therefore argued that executive mechanisms regulate everyday thought and distraction only in demanding contexts. WMC did not moderate other contextual influences on mind-wandering; for example, subjects with higher versus lower WMC didn’t vary in mind-wandering as a function of how much they liked their activities, how boring or stressful they were, or how happy they felt.

Subsequent evidence for executive-control failures contributing to mind-wandering came from laboratory findings that lower WMC subjects report more task-unrelated thoughts (TUTs) than do higher WMC subjects (e.g., Kane et al., 2016; McVay & Kane, 2012b; Robison, Gath, & Unsworth, 2017; Unsworth & McMillan, 2014). Also, poorer-performing subjects on simpler executive-control tasks (e.g., go/no-go, Stroop) report more TUTs than do better performers (Kane et al.; McVay & Kane; Robison et al.; Unsworth, 2015; Unsworth & McMillan). WMC also predicts TUTs best, and perhaps only, in more demanding tasks (e.g., Levinson, Smallwood, & Davidson, 2012; McVay & Kane, 2012a; Rummel & Boywitt, 2014). So far, so good — laboratory and daily-life findings agree. However, two contradictions arise: (a) WMC doesn’t always predict TUTs in demanding tasks (e.g., Krawietz, Tamplin, & Radvansky, 2012); (b) in laboratory experiments requiring concentration ratings after each probe, as in Kane et al. (2007), WMC did not moderate the concentration–mind-wandering association (Smeekens & Kane, 2016).

WMC’s relation to mind-wandering appears complex and may differ between laboratory and everyday settings. Or perhaps the daily-life results were unreliable? Kane et al. (2007) influenced theorizing about executive contributions to mind-wandering, so it requires replication and extension. Because ESM studies are challenging and expensive, however, they elicit few replication attempts (but see Marcusson-Clavertz, Cardeña, & Terhune, 2016).1 The present study expanded the original’s sample size, more broadly measured WMC, and assessed conscious experiences beyond mind-wandering (e.g., thought controllability). Moreover, given theoretical claims regarding WMC’s executive-attentional basis, we expanded our assessment to include attention-restraint ability (via inhibitory-control tasks), attention-constraint ability (via flanker-interference tasks), and laboratory TUT propensity (via task-embedded thought probes), to test whether other executive constructs also interact with prevailing cognitive demands in predicting mind-wandering.

Although executive-control abilities predict mind-wandering, and executive failures may precipitate TUTs, mind-wandering theories disagree about executive influences relative to other trait and contextual variables (e.g., McMillan, Kaufman, & Singer, 2013; McVay & Kane, 2010; Mooneyham & Schooler, 2013; Smallwood & Andrews-Hanna, 2013). Personality traits are likely contributors to mind-wandering variation, as they influence a host of experiential constructs (e.g., Mehl, Gosling, & Pennebaker, 2006; Ozer & Benet-Martínez, 2006). Surprisingly, though, few thought-sampling studies have investigated personality. Instead, researchers have primarily correlated personality scales with retrospective daydreaming questionnaires (McMillan et al.), which are vulnerable to memory and reporting biases. Considering the “big five” factors of personality, only neuroticism (Jackson, Weinstein, & Balota, 2013; Robison et al., 2017), conscientiousness (Jackson & Balota, 2012; Jackson et al., 2013), and openness to experience (Smeekens & Kane, 2016) have been assessed as predictors of probed laboratory TUT rates.

These few studies suggest that laboratory TUTs correlate positively with neuroticism (Jackson et al., 2013; Robison et al., 2017), negatively with conscientiousness (Jackson & Balota, 2012; but see Jackson et al.), but not with openness (Smeekens & Kane, 2016). The neuroticism and conscientiousness findings fit well with theory and seem generalizable to everyday life (at least, for conscientiousness, to activities requiring motivation). The null association between TUTs and openness, however, seems counterintuitive because openness is partially defined as reflecting a rich fantasy life (McCrae & Sutin, 2009). Indeed, openness correlates with retrospective questionnaires of “positive-constructive” daydreaming (McMillan et al., 2013). Perhaps these discrepant results indicate that high-openness people engage in frequent everyday mind-wandering when circumstances allow, but they can concentrate when necessary, such as during artificial laboratory tasks.

These selective personality correlations, and the divergent lab–life effects of concentration on WMC’s mind-wandering association, suggest potentially important differences in mind-wandering experiences across environments, consistent with the “context regulation” perspective offered by Smallwood and Andrews-Hanna (2013). Because mind-wandering’s costs and benefits vary by context, so will its regulation; researchers should therefore examine mind-wandering across a range of laboratory contexts. Our study goes still further, uniquely contrasting the relations of cognitive and personality constructs to mind-wandering propensity between laboratory and extra-lab, daily-life settings.

Method

Below we report how we determined our sample size and all data exclusions, manipulations, and measures in the study (Simmons, Nelson, & Simonsohn, 2012).

Subjects

Undergraduates at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, a comprehensive state university (and Minority Serving Institution for African-American students), were invited to participate in an ESM assessment after completing the second or third session of a laboratory study (Kane et al., 2016). Our data-collection stopping rule was to test subjects in the laboratory study until at least 400 completed three laboratory sessions and at least 200 of these had usable data from the present study. Five hundred forty-five subjects completed the first lab session, 492 completed two sessions, and 472 completed three; 276 subjects enrolled in the ESM study reported here. Our target sample size 0f 200 was based on Monte Carlo simulations (Muthén & Muthén, 2002) that estimated power to detect significant level 1 and level 2 main effects and cross-level interactions (with five latent-variable predictors at level 2). We simulated power for several sample sizes (100, 200, 300) and for small, medium, and large effects. Our proposed sample size, which we exceeded by 37%, was sufficiently powered (> .85) for medium effects.

We collected usable ESM data from 274 subjects (188 female, 81 male, 5 not identified), ages 18–35 years (M = 18.74, SD = 1.79, reporting N = 273) after dropping two subjects’ data (see below). Self-reported race in the sample (reporting N = 271) was 42% White, 44% African American, 3% Asian, 0% Native American/Alaskan Native, 0% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, 6% Multiracial, 6% Other; self-reported ethnicity, which was asked separately (reporting N = 272), was 8% Latino/Hispanic.

Laboratory Cognitive Measures

For extended descriptions of tasks and their scoring, see Kane et al. (2016).

WMC

In six tasks, subjects briefly maintained items in memory while engaging in additional mental processes. Four complex span tasks presented short sequences of items for immediate serial recall; each memory item was preceded by an unrelated processing task requiring a yes/no response. Operation Span required subjects to recall 3–7 letters interleaved with compound equations to verify as correct or incorrect; Reading Span required subjects to recall 2–6 words interleaved with sentences to verify as meaningful or nonsensical; Symmetry Span required subjects to recall 2–5 red cells within a 4 × 4 matrix interleaved with black-and-white grid patterns to verify as vertically symmetrical or asymmetrical; Rotation Span required subjects to recall 2–5 large- and small-arrow orientations (radiating from fixation) interleaved with rotated letters to verify as normal or mirror-reversed. The other two tasks were Running Span and Updating Counters. Running Span required subjects to recall the last N letters from a sequence. The value of N (from 3–7) was cued on each trial, and the total length of each list was unpredictably N, N+1, or N+2 letters. Updating Counters required subjects to encode the digit presented in each of 3–5 horizontally arranged boxes on each trial. After an updating phase in which 2–6 of those digit values were unpredictably updated between −7 and +7, subjects recalled the final value for each box as it was cued in random order. For all tasks, higher scores reflected more items correctly recalled.

Attention restraint

Five restraint tasks asked subjects to override a dominant response in favor of a novel one. Two antisaccade tasks presented a flashing cue to the left or right, and subjects had to orient their attention to the opposite side to identify a brief, masked target presented there; Antisaccade Letters presented letter targets (B, P, or R) and Antisaccade Arrows presented arrows pointing up, down, left, or right. The dependent measure from both antisaccade tasks was error rate. The Sustained Attention to Response Task (SART) was a go/no-go task requiring subjects to press a key for animal names (89% of 675 trials) and withhold responding for vegetable names (11% of trials); the dependent measures from the SART were d’ and RT intraindividual standard deviation. Number Stroop presented a row of 2–4 digits on each trial and subjects reported via key-press the tally of digits while ignoring their identity; 20% of trials presented incongruent arrays (e.g., 44; 3333). The dependent measure was RT for incongruent trials. Spatial Stroop required subjects to report via key-press the relative position of a direction word (UP, DOWN, RIGHT, LEFT) to an asterisk, with both the word and asterisk presented to the left or right, or above or below, fixation; 33% of trials presented words that were incongruent for both absolute and relative location (e.g., DOWN presented above the asterisk and both presented above fixation) and 33% were congruent for both (e.g., DOWN presented below the asterisk and both below fixation). The dependent measure was the residual of incongruent trial accuracy regressed on congruent trial accuracy.

Attention constraint

Five flanker tasks presented a target for identification amid visual distractors that were target-compatible, incompatible, or neutral. In two tasks, Arrow Flanker and Letter Flanker, targets were flanked horizontally by 4 and 6 distractors, respectively; Arrow Flanker presented right- or left-pointing target arrows amid right-, left-, or (neutral) upward-pointing flankers, and Letter Flanker presented normal- or backward-facing target Fs amid normal- or backward-facing Fs or (neutral) Es and tilted Ts at 90° and 270°. For both Arrow and Letter flanker, the dependent variable was the residual of incompatible-trial RT regressed on neutral- and compatible-trial RT. Conditional Accuracy Flanker presented a target H or S flanked horizontally by 4 H’s, S’s, or (neutral) B’s; the first trial block imposed a 600 ms response deadline for each trial and the second a 500 ms deadline (both with deadline feedback). The dependent measure was the residual of incompatible-trial accuracy regressed on neutral- and compatible-trial accuracy. Masked Flanker presented a target letter flanked above, below, to the left, and to the right with other letters or with (neutral) colons (“:”) prior to being masked after 50 or 70 ms; the dependent variable was the residual of incompatible-trial accuracy regressed on neutral- and compatible-trial accuracy. Circle Flanker presented a target X or N, flanked by two letter (H, K, M, V, Y, Z) or (neutral) colon distractors, along the circumference of an imaginary circle; the dependent measure was the residual of incompatible-trial RT regressed on neutral-trial RT.

TUTs

Thought probes appeared unpredictably within 5 tasks (45 probes in SART, 20 in Number Stroop, 20 in Arrow Flanker, 12 in Letter Flanker, and 15 in an otherwise-unanalyzed 2-back task). At each probe, subjects chose among the eight presented options that most closely matched the content of their immediately preceding thoughts. Choices 3–8 reflected TUTs (“everyday things,” “current state of being,” “personal worries,” “daydreams,” “external environment,” “other”) and so the mind-wandering dependent measure from each task was the proportion of probes on which subjects reported a TUT.

Non-analyzed measures

As part of the larger project, laboratory subjects also completed schizotypy questionnaires and divergent thinking tasks (see Kane et al., 2016). Associations between these measures and daily-life experiences will be reported elsewhere.

Cognitive construct scores

We derived individual subject scores for WMC, attention restraint, attention constraint, and TUT rate constructs by saving factor scores from a confirmatory factor analysis on all laboratory measures (including schizotypy questionnaires) on the complete laboratory subject sample (see Kane et al., 2016). As reported in Kane et al., all indicators loaded significantly onto their respective factors and TUT rates showed good internal reliabilities within tasks (coefficient alphas = .78 – .93) and they also demonstrated reliability by correlating across tasks (rs = .32 – .68). We used the four cognitive factor scores from the ESM-completing subjects as the predictors in ESM analyses. Higher WMC scores reflected better performance, whereas higher restraint and constraint scores reflected more performance failures and higher TUT rates reflected more off-task thought.

Personality Measures

During the initial information session for the ESM study (see below), subjects completed a computerized version of the NEO-FFI-3 (McCrae & Costa, 2010), a 60-item inventory for assessing the Five-Factor Model of personality (Openness to experience, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, Neuroticism; 12 items per factor). Each item used a 5-point Likert scale, labeled “Strongly Disagree,” “Disagree,” “Neutral,” “Agree,” and “Strongly Agree.” (Subjects then completed two additional self-report scales that are not analyzed here.) Personality data were missing for three subjects, leaving N = 271 for all personality-related analyses.

ESM Method

Palm personal digital assistants (Palm Zire, Sunnyvale, CA) running ESP software (Barrett & Barrett, n.d.) presented all questionnaires and collected responses via a stylus interface. Each questionnaire was cued by a beep. Subjects were randomly signaled 8 times per day for 7 days (plus part of the day that included the training session) during each of eight 90 min blocks from noon to midnight. Subjects had up to 5 min to begin responding and up to 5 min to complete each questionnaire.

Each questionnaire (see Table 1 for items) first asked subjects whether they were mind-wandering at the beep (“yes” = 1; “no” = 2); if mind-wandering, subjects then rated their off-task thought qualities along 5 dimensions. These questions were asked first because they addressed potentially fleeting conscious states. Regardless of mind-wandering status, the questionnaire then asked several questions about subjects’ efforts to concentrate and their subjective thought qualities (again, asked before other context questions to minimize forgetting). Finally, subjects then answered several questions about their current activity and emotional context (most with a 7-point Likert scale).

Table 1.

Experience sampling questionnaire items

1. At the time of the beep, my mind had wandered to something other than what I was doing

|

| 7. At the beep, I was trying to concentrate on what I was doing [concentrate] |

| 8. Right now my thoughts are pleasant [pleasant] |

| 9. Right now my thoughts are strange or unusual [strange] |

| 10. Right now my thoughts are clear [clear] |

| 11. Right now I can hardly control my thoughts [hardly control] |

| 12. Right now I have no thoughts or emotions [no thoughts] |

| 13. Right now my thoughts are racing [racing] |

| 14. Right now my thoughts are suspicious [suspicious] |

| 15. Right now I feel someone or something is controlling my thoughts or actions [controlled] |

| 16. I feel happy right now [happy] |

| 17. I feel confused right now [confused] |

| 18. I feel irritable right now [irritable] |

| 19. I feel safe right now [safe] |

| 20. I feel anxious right now [anxious] |

| 21. I feel tired right now [tired] |

| 22. I feel sad right now [sad] |

| 23. Right now my sight or hearing seems strange or unusual [perception strange] |

| 24. I like what I’m doing right now [like activity] |

| 25. What I’m doing right now takes a lot of effort [effortful activity] |

| 26. What I’m doing right now is boring [boring activity] |

| 27. I am successful at this activity right now [successful activity] |

28. I am alone right now [not alone]

|

| 34. My current situation is stressful [stressful situation] |

| 35. My current situation is positive [positive situation] |

Note. Items 1 and 28 required a “yes” (coded as 1) or “no” (coded as 2) response; All other items were answered on a scale from 1–7 (1 = not at all, 4 = moderately, 7 = very much). Items 2–6 were skipped if the item 1 response was “no;” presentation of items 29–33 depended on response to item 28. Bracketed, italicized labels will be used in subsequent Tables for each item. Italicized items 29–33 are not analyzed here.

At the ESM information session, subjects provided informed consent and the experimenter explained the ESM questionnaire (including what we meant by mind-wandering, with examples; see full instruction script at https://osf.io/p6rak/), instructed subjects how to use the PDAs, and described the study requirements (including 3 brief lab visits to download data and report technical problems). Of note, we took pains to instruct subjects to use each beep as a cue to take immediate stock of their thoughts so that they could accurately answer the ESM questions. For example, early in the instruction script we said: “As you know, your thoughts can drift and change very quickly, so it’s very important that when you hear the beep, you immediately take stock of what you were actually thinking about.” Later in the script we said: “So, just to review, we’ll be asking you throughout the week to respond, at the beep, to questions about what you were thinking and doing just before the beep interrupted you. Because your thoughts can change quickly, please use the beep as a signal to pay attention to, and remember, what exactly you were thinking about just before the palm pilot beeped” (emphasis in the original). Subjects then completed the NEO-FFI-3. We gave subjects written instructions and laboratory contact information to take with them, and ESM signal blocks began immediately following the information session. Subjects earned $50 for completing the study and were entered into a gift-card lottery if they attended all download appointments and completed ≥ 70% of the ESM questionnaires.

ESM Data Analyses and Screening

ESM data have a hierarchical structure, with questionnaire responses (level 1) nested within subjects (level 2). Our primary analyses therefore used multilevel modeling with robust standard errors (MLR estimator) conducted with Mplus 7.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 2012). Level 1 predictors (e.g., concentration ratings at each beep) were group-mean centered. Level 2 predictors (e.g., WMC factor scores) were grand-mean centered for cognitive constructs and standardized for personality factors. Cross-level interactions tested whether within-person associations between level 1 variables (e.g., the relation between concentrating and mind-wandering) were moderated by a between-person, level 2 variable (e.g., WMC). We analyzed mind-wandering as a categorical outcome, coded as 1 (mind-wandering) versus 2 (on-task). All reported coefficients from multilevel analyses are unstandardized and thus their magnitudes are not comparable.

Survey researchers acknowledge that subjects sometimes respond carelessly or randomly, and so a common strategy is to embed “catch” items into self-report questionnaires to identify problematic data and subjects (e.g., Maniachi & Rogge, 2014). In daily-life ESM studies, however, researchers seek to minimize the burden on subjects and rarely include non-critical items in their questionnaires. To screen our data for potentially problematic responding (see Sperry & Kwapil, in press), we calculated the variance for items 7–27 in every completed survey; all of these items presented a 1–7 Likert scale and they appeared on every questionnaire. Low variance across these items likely reflected carelessly or inattentively selecting (nearly) the same numerical response for each item, particularly because several items implied opposite responses and so should have produced divergent ratings (e.g., having pleasant vs. suspicious thoughts; feeling sad vs. happy; feeling safe vs. anxious; liking one’s activity vs. finding it boring). We then dropped all individual questionnaires with variance scores more than 1.96 SDs below the mean, thereby treating 223 questionnaires (2.1%) as missing data. Furthermore, all data from two subjects were removed for having 56% and 39% of their questionnaires, respectively, dropped for low variance, leaving us with 274 subjects in the dataset. (We decided to conduct these questionnaire-variance analyses after observing our raw level-1 data; however, this decision preceded our conducting the level-1 and level-2 analyses.)

Results

Data used for all analyses, as well as sample analysis scripts and output, are available via the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/p6rak/). For our primary analyses that were constrained by prior findings, we set a conventional .05 alpha level: Our cognitive replication analyses assessed: (a) the cross-level interaction of WMC moderating the effect of concentration on daily-life mind-wandering (Kane et al., 2007); (b) the cross-level interaction of WMC moderating the effect of activity effort demands on daily-life mind-wandering (Kane et al., 2007); and (c) the prediction of daily-life mind-wandering rate by laboratory TUT rate (McVay, Kane, & Kwapil, 2009). Our a priori personality analyses assessed: (a) the prediction of daily-life mind-wandering rate by conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness; and (b) the prediction of fantasy-daydreaming content of daily-life mind-wandering by openness, worry content by neuroticism, and goal-related content by conscientiousness. Because we report many additional analyses, we otherwise adopt an alpha of .005.

On average, subjects completed 38.4 (SD = 11.6, range = 12–71) usable ESM questionnaires. Completion rate did not correlate with the cognitive measures of WMC, r(272) = .06, p = .361, attention restraint, r(272) = −.09, p = .140, or attention constraint, r(272)= −.07, p > .250, but it did with laboratory TUT rate, r(272) = −.20, p = .001: subjects with higher lab TUT rates completed fewer questionnaires. Completion rate did not correlate with personality factors: openness, r(269)= −.08, p = .196; conscientiousness, r(269) = .16, p = .008; extraversion, r(269) = −.13, p = .029; agreeableness, r(269) = .02, p > .250; neuroticism, r(269) = −.03, p > .250 (although effect sizes for conscientiousness and extraversion were arguably as expected).

Associations Among Cognitive and Personality Predictor Variables

Table 2 presents correlations among our predictor variables. Consistent with the latent-variable findings from the full laboratory sample (Kane et al., 2016) and with prior studies (McVay & Kane, 2012b; Unsworth & McMillan, 2014), laboratory TUT rates were modestly correlated with WMC and more strongly correlated with attention restraint and constraint failures. Also replicating prior laboratory findings, TUTs were positively correlated with neuroticism (Robeson et al., 2016) but uncorrelated with openness (Smeekens & Kane, 2016). No other personality factors significantly predicted lab TUTs; note that the inconsistently demonstrated conscientiousness-TUT correlation (Jackson & Balota, 2012, vs. Jackson et al., 2013) was not significant here by our conservative threshold, but would have been by a more liberal and typical one, r(269) = −.13, p = .040.

Table 2.

Correlations among the cognitive and personality predictor variables from the laboratory.

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Lab TUTs | -- | ||||||||

| 2. WMC | −.20* | -- | |||||||

| 3. Restraint | .47* | −.72* | -- | ||||||

| 4. Constraint | .49* | −.51* | .75* | -- | |||||

| 5. Openness | −.03 | .18* | −.09 | −.15 | -- | ||||

| 6. Conscientiousness | −.13 | −.01 | −.01 | .02 | .00 | -- | |||

| 7. Extraversion | .04 | −.07 | .02 | .04 | .14 | .27* | -- | ||

| 8. Agreeableness | −.05 | .04 | −.11 | −.08 | .07 | .20* | .27* | -- | |

| 9. Neuroticism | .18* | −.04 | .18* | .13 | .06 | −.35* | −.32* | −.21* | -- |

Note. * and bolded text = significant correlations (p < .005); N = 274 for cognitive-variable pairs and N = 271 for all pairs involving personality variables. TUTs = task-unrelated thought rate in the lab; WMC = working memory capacity; Restraint = attention-restraint failure; Constraint = attention-constraint failure.

Overall Rate and Content of Daily-Life Mind-wandering

Matching our prior findings that undergraduates’ thoughts are off-task 30% of the time (Kane et al., 2007; McVay et al., 2009; see also Franklin et al., 2013; Marcusson-Clavertz et al., 2016; Song & Wang, 2012), subjects reported mind-wandering at M = 32% (SD = 17%) of beeps, with a range of 2–97%. These results reinforce that mind-wandering is generally a common occurrence that nonetheless varies greatly in frequency among young adults, perhaps due to cognitive and personality differences. When subjects reported mind-wandering, they indicated being “tuned out” (i.e., mind-wandering with some awareness) 60.4% of the time (vs. 39.6% of the time “zoned out,” without awareness), and their mean (±SE) ratings for mind-wandering content (on a 1–7 scale) were daydreams/fantasy (3.79±.08), worries/problems (M = 3.20±.07), stuff to do (4.39±.07), and visual/auditory surroundings (3.63±.07). Off-task thoughts thus tended to happen with awareness and to focus on everyday plans and goals.

Contextual Predictors of Daily-Life Mind-wandering

When tested individually, many of the contextual variables significantly predicted mind-wandering in the moment (see Table 3): Subjects tended to be more mentally on-task when they tried harder to concentrate, when they engaged in preferred activities, and when they were happier and their situations were generally more positive. Subjects tended to mind-wander more when experiencing more negative affect (feeling anxious, sad, irritable, and confused), when they felt more tired, and when their activities were more boring. Mind-wandering was statistically unaffected by whether subjects were alone or with others, or felt more of less safe in their context, or were engaging in more or less effortful activities. When all of the contextual variables were entered into a single model, however, only three met our conservative significance criterion for predicting mind-wandering above and beyond the others: Subjects were more on-task when they tried harder to concentrate and they were more off-task when they felt more anxious and when their activity was more boring.

Table 3.

Contextual predictors of on-task thought (higher score) versus mind-wandering (lower score), with each predictor tested individually and all predictors modeled together.

| Tested Individually

|

Modeled Together

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b [95% CI] | Z | p | b [95% CI] | Z | p | |

|

|

|

|||||

| Concentrate | .44 [.39, .48] | 18.06 | <.001* | .45 [.40, .50] | 18.08 | <.001* |

| Happy | .09 [.06, .12] | 5.55 | <.001* | −.01 [−.05, .03] | −0.62 | >.250 |

| Confused | −.08 [−.11, −.05] | −4.65 | <.001* | −.05 [−.09, −.00] | −2.15 | .031 |

| Irritable | −.05 [−.08, −.02] | −3.05 | .002* | .03 [−.01, .07] | 1.57 | .116 |

| Safe | .05 [.01, .09] | 2.33 | .020 | −.03 [−.07, .02] | −1.15 | .249 |

| Anxious | −.08 [−.12, −.05] | −5.33 | <.001* | −.08 [−.11, −.04] | −4.16 | <.001* |

| Tired | −.06 [−.09, −.04] | −4.84 | <.001* | −.04 [−.06, −.01] | −2.38 | .017 |

| Sad | −.08 [−.12, −.05] | −4.95 | <.001* | −.01 [−.06, .04] | −0.36 | >.250 |

| Perception strange | −.08 [−.13, −.03] | −3.07 | .002* | −.02 [−.08, .04] | −0.73 | >.250 |

| Like activity | .12 [.10, .15] | 8.76 | <.001* | .04 [.01, .08] | 2.46 | .014 |

| Effortful activity | .03 [−.00, .06] | 1.90 | .058 | −.04 [−.07, −.01] | −2.66 | .008 |

| Boring activity | −.12 [−.15, −.10] | −9.13 | <.001* | −.07 [−.11, −.04] | −4.51 | <.001* |

| Successful activity | .05 [.02, .08] | 3.26 | .001* | −.03 [−.07, .00] | −1.82 | .069 |

| Not Alone | .03 [−.08, .13] | 0.50 | >.250 | .09 [−.02, .20] | 1.64 | .101 |

| Stressful situation | −.04 [−.07, −.01] | −2.82 | .005 | −.00 [−.04, .04] | −0.05 | >.250 |

| Positive situation | .10 [.07, .13] | 6.31 | <.001* | .02 [−.02, .06] | 1.06 | >.250 |

Note: Significant effects (p < .005) are marked by bolded text and an asterisk. b = unstandardized coefficient; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval.

Executive-Control Ability, Daily-Life Mind-Wandering Rate, and Context

Before exploring individual differences in daily-life mind-wandering, we must consider the reliability of our assessment, particularly because thought content was substantially influenced by the prevailing context. In fact, mind-wandering rates were statistically reliable. We estimated reliability for the mind-wandering ESM item in a many-facet Rasch model framework (Eckes, 2011) using FACETS 3.71.4 (Linacre, 2014). This class of mixed Rasch models can estimate reliability for single items assessed repeatedly, even when the item is categorical and subjects differ in number of responses. Rasch reliability — the true lower bound of reliability (Linacre, 1997) — was .77, indicating a good ability to discriminate among people’s propensities to mind-wandering in daily life.

McVay et al. (2009) found that laboratory TUT rates predicted daily-life mind-wandering overall, whereas Kane et al. (2007) found that WMC predicted mind-wandering only as a function of the cognitive demands of the context — that is, with lower WMC subjects mind-wandering more than higher WMC subjects as they tried harder to concentrate and their activities were more challenging or effortful than usual. Here, laboratory TUT rate did not significantly (alpha = .05) predict mind-wandering in daily life, b = −.18 [95% CI −.37, −.02], Z = −1.81, p = .070, although this nearly significant effect was in the same direction as in McVay et al., with more TUTs in the lab associated with more mind-wandering (less on-task thinking) in daily life. Given our larger sample here (n = 274 vs. 72), with only a marginal effect, we must conclude that any relation between laboratory and overall daily-life mind-wandering propensities is not robust. None of the other cognitive constructs predicted overall mind-wandering rates in daily life, despite their significantly predicting TUT rates in the lab (WMC: b = .01 [−.17, .19], Z = 0.14, p > .250; attention restraint: b = −.07 [−.21, .08], Z = −0.87, p > .250; attention constraint: b = −.27 [−.60, .06], Z = −1.62, p = .106).

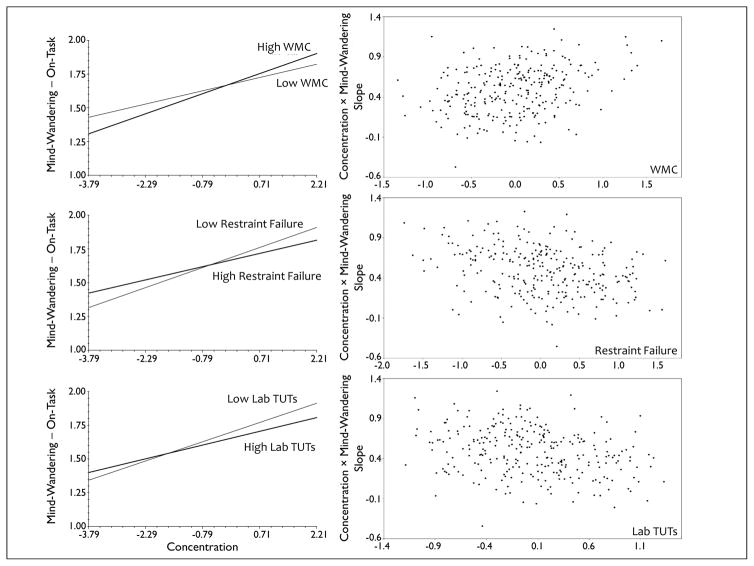

Consistent with a central daily-life finding from Kane et al. (2007), however, and contrasting with the laboratory findings from Smeekens and Kane (2016), WMC significantly moderated the association between self-reported concentration efforts and mind-wandering (see Table 4). Figure 1 illustrates that the form of this cross-level interaction also replicated. As subjects reported trying harder than usual to concentrate, those with higher WMC were more mentally on-task than were subjects with lower WMC; moreover, as subjects reported trying less than usual to concentrate, those with higher WMC mind-wandered more than did those with lower WMC. Viewed another way, the steeper slope for higher WMC students suggests that their conscious experiences were more responsive to their concentration efforts than were those of lower WMC — higher WMC students exerted better control over their thoughts. In contrast to a second major finding from Kane et al. (2007), though, Table 4 also indicates that WMC did not moderate the association between the subjective effort required by students’ activities and mind-wandering; here, as subjects’ activities were judged to be more effortful, we did not replicate the Kane et al. finding that lower WMC subjects mind-wandered more than did higher WMC subjects. Note also that this lack of a WMC–mind-wandering association under high effort (see also Marcusson et al., 2016) seems to conflict with lab findings that WMC predicts TUTs only in more demanding tasks (e.g., Levinson et al., 2012; McVay & Kane, 2012a).

Table 4.

Cross-level interactions of level-1 cognitive predictors of on-task thought versus mind-wandering with level-2 cognitive constructs from the laboratory (each tested individually).

| WMC

|

Restraint

|

Constraint

|

Lab TUTs

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b [95%CI] | Z | p | b [95% CI] | Z | p | b [95% CI] | Z | p | b [95% CI] | Z | p | |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Mind-wandering ×: | ||||||||||||

| Concentrate | .17 [.07, .27] | 3.39 | .001* | −.14 [−.21, −.07] | −3.77 | <.001* | −.20 [−.36, −.05] | −2.59 | .010 | −.14 [−.24, −.05] | −3.00 | .003* |

| Effortful Activity | .03 [−.04, .09] | 0.88 | >.250 | −.02 [−.07, .03] | −0.70 | >.250 | .06 [−.04, .16] | 1.14 | >.250 | .02 [−.04, .08] | 0.69 | >.250 |

| Happy | −.00 [−.07, .06] | −0.12 | >.250 | .00 [−.05, .05] | 0.06 | >.250 | −.02 [−.12, .09] | −0.35 | >.250 | .05 [−.02, .11] | 1.45 | .148 |

| Confused | .01 [−.05, .08] | 0.37 | >.250 | .00 [−.05, .05] | 0.12 | >.250 | .05 [−.05, .15] | 0.97 | >.250 | −.04 [−.10, .02] | −1.25 | .212 |

| Irritable | .04 [−.02, .09] | 1.28 | .202 | −.00 [−.05, .04] | −0.16 | >.250 | .07 [−.02, .17] | 1.53 | .126 | −.03 [−.09, .03] | −1.12 | >.250 |

| Safe | −.06 [−.13, .01] | −1.62 | .106 | .04 [−.02, .10] | 1.36 | .173 | −.01 [−.14, .12] | −0.15 | >.250 | .01 [−.06, .08] | 0.23 | >.250 |

| Anxious | .03 [−.03, .09] | 1.05 | >.250 | −.01 [−.06, .03] | −0.51 | >.250 | .01 [−.08, .11] | 0.24 | >.250 | −.05 [−.12, .01] | −1.67 | .095 |

| Tired | .00 [−.05, .05] | 0.08 | >.250 | .02 [−.02, .05] | 0.76 | >.250 | .03 [−.06, .11] | 0.66 | >.250 | −.01 [−.05, .04] | −0.27 | >.250 |

| Sad | −.01 [−.08, .06] | −0.33 | >.250 | .04 [−.02, .09] | 1.25 | .210 | .11 [.00, .23] | 1.95 | .051 | −.02 [−.09, .05] | −0.60 | >.250 |

| Perception Strange | −.05 [−.14, .04] | −1.16 | .244 | .06 [−.02, .14] | 1.44 | .149 | .24 [.07, .41] | 2.74 | .006 | .03 [−.08, .13] | 0.50 | >.250 |

| Like Activity | −.01 [−.07, .05] | −0.33 | >.250 | −.02 [−.07, .02] | −1.11 | >.250 | −.03 [−.13, .06] | −0.71 | >.250 | −.04 [−.09, .02] | −1.34 | .179 |

| Boring Activity | .02 [−.03, .06] | 0.67 | >.250 | −.00 [−.04, .03] | −0.07 | >.250 | −.02 [−.10, .06] | −0.53 | >.250 | .00 [−.04, .05] | 0.15 | >.250 |

| Successful Activity | −.03 [−.08, .03] | −0.87 | >.250 | −.03 [−.07, .01] | −1.43 | .153 | −.04 [−.13, .05] | −0.87 | >.250 | −.04 [−.11, .02] | −1.33 | .183 |

| Not Alone | −.10 [−.31, .12] | −0.89 | >.250 | −.01 [−.18, .17] | −0.07 | >.250 | −.21 [−.57, .16] | −1.12 | >.250 | .08 [−.11, .27] | 0.81 | >.250 |

| Stressful Situation | .01 [−.04, .07] | 0.42 | >.250 | .01 [−.04, .06] | 0.44 | >.250 | .08 [−.02, .18] | 1.66 | .097 | −.00 [−.06, .06] | −0.04 | >.250 |

| Positive Situation | .03 [−.04, .10] | 0.93 | >.250 | −.05 [−.09, .00] | −1.89 | .059 | −.08 [−.17, .02] | −1.58 | .113 | .02 [−.04, .08] | 0.74 | >.250 |

Note: Significant effects (p < .005) are marked by asterisks and bolded text. b = unstandardized coefficient; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval.

Figure 1.

The relation of daily-life mind wandering with self-reported concentration across levels of executive-control abilities (working memory capacity [WMC], attention restraint failures, laboratory rates of task-unrelated thoughts [TUTs]). For panels on the left, lines depict the means of the within-person slopes for subjects in the top and bottom quartiles of WMC, attention restraint failure, and laboratory TUT rate scores; values on the x-axis represent group-centered ratings for concentration (“I had been trying to concentrate on what I was doing.”); values on the y-axis represent the mind-wandering dependent variable, scored on each questionnaire as either a 1 (for mind wandering) or 2 (for on-task thoughts) and so lower values indicate more mind wandering. For panels on the right, each dot represents an individual subject; values on the x-axis represent grand mean centered scores for WMC, attention restraint failures, and laboratory TUT rates; values on the y-axis represent the slope of the effect of concentration rating on thought content (steeper positive slopes indicate stronger positive associations between momentary concentration on on-task thinking).

Although the cross-level interaction involving activity effort did not replicate, the cross-level interaction involving concentration was significant not only for WMC, as noted above, but also for attention restraint and laboratory TUT rate (alpha = .005). Table 4 and Figure 1 indicate that, as with higher WMC, subjects with less attention restraint failure and fewer laboratory TUTs also were more effectively on-task as they reported trying harder than usual to concentrate on their ongoing activity than were subjects with more attention restraint failures and more laboratory TUTs. Similarly, the higher ability subjects tended to mind-wander more than the lower ability subjects on occasions when they tried to concentrate less than usual. It is all the more impressive that this cross-level interaction pattern replicated across our cognitive individual-differences variables because laboratory TUT rates correlated only modestly with WMC. These constructs were not simply redundant, but they should share some executive-control-related variance.

Indeed, we tested the hypothesis that general executive-control processes drive the associations between cognitive abilities and the self-regulation of daily-life mind-wandering, in two ways. The first was analogous to simultaneous multiple regression, which assesses whether predictors account for variance in an outcome above and beyond the other predictors in the model. Specifically, we entered all three significant cognitive predictors into the concentration–mind-wandering cross-level-interaction model, to see whether any executive construct would moderate the interaction independently of the others. They did not (WMC: b = .12 [95% CI −.04, .28], Z = 1.50, p = .133; attention restraint: b = −.03 [−.15, .10], Z = −0.46, p > .250; laboratory TUTs: b = −.10 [−.21, .01], Z = −1.77, p = .077; these conclusions also held when the constraint factor was added to the model). Second, we used structural equation modeling to model the predictor variables as reflecting both general (shared) executive variance and domain-specific variance. Specifically, we saved factor scores from an additional (“bifactor”) structural model from Kane et al. (2016), which represented the variance shared by all WMC, restraint, constraint, and TUT measures as a general executive factor. It also modeled the variance common to the WMC tasks but not shared with the other tasks as a WMC-residual (specific) factor, and the variance common to the TUT measures but not shared with the other tasks as a TUT-residual (specific) factor. Here, the general executive factor again moderated the effect of concentration on daily-life mind-wandering, b = −.14 [−.22, −.07], Z = −3.82, p < .001, whereas the WMC-residual factor and the TUT-residual factor did not (WMC-residual: b = .05 [−.05, .14], Z = 0.98, p > .250; TUT-residual: b = −.10 [−.21, .01], Z = −1.83, p = .068). Both analyses reinforce that the shared executive variance among WMC, attention restraint, and laboratory TUT propensity drove their interactions with concentration efforts to predict daily-life mind-wandering

As in Kane et al. (2007), cognitive ability constructs did not moderate the influences of other contextual predictors of mind-wandering, such as the association between boring activities and mind-wandering, or anxious feelings and mind-wandering (see Table 4). That is, lower-WMC subjects didn’t simply report more mind-wandering than higher-WMC subjects when they were relatively bored, or relatively anxious, or doing relatively undesirable activities. These findings indicate, again, that the effects of cognitive ability on mind-wandering are limited to contexts in which subjects attempt to bring their control abilities to bear on regulating thought via concentration, and are not merely the result of common folk theories about when people should or should not experience mind-wandering in everyday life. Moreover, WMC doesn’t moderate this same concentration–mind-wandering association in the laboratory (Smeekens & Kane, 2016), as it did here and in Kane et al. (2007), and so it does not appear to reflect a WMC-related bias or belief about TUTs and concentration.

Executive-Control Ability and Daily-Life Thought Qualities

Whether or not subjects were currently mind-wandering, they always answered eight questions about their thoughts, addressing subjective controllability or content. Table 5 indicates that, overall, on-task thoughts were significantly more pleasant and clear than off-task thoughts, and significantly less strange, suspicious, racing, and uncontrollable. Mind-wandering experiences, then, were relatively negative in our sample, consistent with Killingsworth and Gilbert (2010; see also Kane et al., 2007; McVay et al., 2009).

Table 5.

Thought quality outcomes by on-task thought versus mind-wandering in the moment.

| b [95% CI] | Z | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pleasant | .18 [.11, .26] | 4.81 | <.001* |

| Strange | −.22 [−.29, −.16] | −6.77 | <.001* |

| Clear | .38 [.30, .45] | 9.93 | <.001* |

| Hardly Control | −.23 [−.31, −.16] | −6.14 | <.001* |

| No Thoughts | .03 [−.05, .10] | 0.70 | >.250 |

| Racing | −.21 [−.29, −.13] | −5.12 | <.001* |

| Suspicious | −.11 [−.17, −.06] | −4.08 | <.001* |

| Controlled | −.07 [−.12, −.02] | −2.62 | .009 |

Note. Significant effects (p < .005) are marked by an asterisk and bolded text. b = unstandardized coefficient; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval. Positive coefficients reflect experiences more likely when on-task and negative coefficients reflect experiences more likely when mind-wandering.

On those occasions when subjects reported mind-wandering, the content of their off-task thought was not generally associated with the executive-attention constructs we measured (see Table 6). Thus, subjects of higher versus lower cognitive ability were no more or less likely to zone out without awareness, to daydream, to worry, to think about their unfulfilled goals and plans, or to be distracted by their immediate environment. (We thus failed to replicate an exploratory finding from McVay et al., 2009, that subjects with higher lab TUT rates reported more worrying content in daily-life mind-wandering than did those with lower lab TUT rates).

Table 6.

Daily-life thought quality outcomes predicted by cognitive constructs from the laboratory (each tested individually).

| WMC

|

Restraint

|

Constraint

|

Lab TUTs

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b [95% CI] | Z | p | b [95% CI] | Z | p | b [95% CI] | Z | p | b [95% CI] | Z | p | |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Mind-wandering Qualities: | ||||||||||||

| ZO > TO | −.14 [−.35, .08] | −1.23 | .219 | .19 [.01, .37] | 2.04 | .042 | .31 [−.05, .68] | 1.69 | .092 | .23 [−.01, .46] | 1.89 | .058 |

| Daydream | −.22 [−.53, .09] | −1.41 | .159 | .21 [−.04, .45] | 1.63 | .103 | .07 [−.44, .57] | 0.26 | >.250 | .36 [.09, .62] | 2.63 | .009 |

| Worries | −.17 [−.44, .10] | −1.25 | .212 | .22 [.03, .41] | 2.31 | .021 | .44 [.05, .84] | 2.21 | .027 | .20 [−.05, .44] | 1.55 | .121 |

| To-Do | −.22 [−.44, .00] | −1.93 | .053 | .13 [−.05, .31] | 1.41 | .159 | .43 [.03, .84] | 2.08 | .037 | .17 [−.08, .42] | 1.34 | .182 |

| Surroundings | .08 [−.17, .33] | 0.61 | >.250 | .02 [−.17, .21] | 0.20 | >.250 | −.11 [−.56, .34] | −0.48 | >.250 | .01 [−.24, .25] | 0.06 | >.250 |

| Other Thought Qualities: | ||||||||||||

| Pleasant | −.02 [−.22, .17] | −0.24 | >.250 | −.04 [−.20, .11] | −0.52 | >.250 | .02 [−.30, .34] | 0.14 | >.250 | −.11 [−.31, .10] | −0.99 | >.250 |

| Strange | −.08 [−.26, .09] | −0.92 | >.250 | .16 [.05, .26] | 2.88 | .004* | .17 [−.03, .38] | 1.65 | .099 | .17 [.04, .31] | 2.48 | .013 |

| Clear | −.03 [−.26, .20] | −0.27 | >.250 | −.18 [−.35, −.01] | −2.06 | .039 | −.20 [−.56, .17] | −1.06 | >.250 | −.24 [−.45, −.02] | −2.13 | .033 |

| Hardly Control | −.32 [−.55, −.09] | −2.68 | .007 | .34 [.18, .50] | 4.09 | <.001* | .47 [.12, .81] | 2.65 | .008 | .42 [.17, .67] | 3.30 | .001* |

| No Thoughts | −.29 [−.50, −.08] | −2.69 | .007 | .21 [.06, .35] | 2.73 | .006 | .35 [−.00, .71] | 1.95 | .051 | .26 [.03, .48] | 2.24 | .025 |

| Racing | −.07 [−.33, .19] | −0.55 | >.250 | .17 [−.01, .34] | 1.90 | .058 | .27 [−.11, .65] | 1.38 | .169 | .42 [.18, .65] | 3.42 | .001* |

| Suspicious | −.07 [−.25, .11] | −0.77 | >.250 | .12 [.00, .25] | 1.99 | .047 | .13 [−.12, .37] | 0.99 | >.250 | .20 [.06, .35] | 2.72 | .007 |

| Controlled | −.09 [−.23, .06] | −1.14 | >.250 | .15 [.05, .24] | 2.97 | .003* | .18 [−.00, .36] | 1.93 | .054 | .11 [−.02, .25] | 1.68 | .093 |

Significant effects (p < .005) are marked by asterisks and bolded text. b = unstandardized coefficient; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval.

In contrast, several cognitive constructs predicted other subjective qualities of thought, regardless of their being on-task or off-task in the moment — most notably regarding the self-regulation of thought (see Table 6). Attention restraint failure and lab TUT rate significantly predicted subjective ratings of the controllability of their thoughts in the moment (Right now I can hardly control my thoughts); these effects were nearly significant also for WMC and constraint failures (ps = .007 and .008, respectively), and are consistent with the steeper slopes between concentration attempts and on-/off-task thinking for higher ability subjects than for lower ability subjects (depicted in Figure 1). Subjects with higher laboratory TUT rates also endorsed more strongly that their current thoughts were racing, and subjects with more attention restraint failure more often reported that their thoughts felt controlled by someone or something else. Regarding qualities of thought content, subjects with more restraint failure in the lab reported stranger thoughts in everyday life.

Personality Traits, Mind-Wandering Rate, and Mind-Wandering Content

As a preliminary validity check for our personality questionnaire measures, we assessed whether they correlated with ESM daily-life indicators that one would theoretically expect (see supplementary Table S1). Indeed, subjects higher in openness to experience reported engaging in less boring activities in the moment than did those lower in openness; subjects higher in neuroticism reported feeling less happy, feeling more confused, irritable, anxious, tired, and sad, and they described their activities and contexts as more boring, more stressful, less liked, and less positive; subjects higher in conscientiousness reported being more successful in their current activity; subjects higher in agreeableness reported feeling more happy and described their situation as more positive; subjects higher in extraversion felt more happy (but also more confused) in the moment.

Returning to our primary questions, Table 7 indicates that, among the personality factors tested simultaneously, only openness to experience significantly (with alpha = .05) predicted overall daily-life mind-wandering rate, with higher openness reflecting more mind wandering. Recall that openness was unassociated with laboratory TUT rate, both here and in Smeekens and Kane (2016). Moreover, although neuroticism correlated positively with lab TUTs (see also Jackson et al., 2013; Robison et al., 2017), neither neuroticism nor conscientiousness (see Jackson & Balota, 2011) predicted everyday mind-wandering, even in analyses where each of these was the only predictor in the model (for neuroticism, Z < 1, p > .250; for conscientiousness, Z = 1.36, p = .175).

Table 7.

Five-factor personality trait predictors of on-task thought (higher score) versus mind-wandering (lower score), and of mind-wandering content (rated on a 1–5 scale), with all personality predictors standardized and modeled simultaneously.

| b [95% CI] | Z | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mind-Wandering Rate | |||

| Openness | −.13 [−.24, −.03] | −2.49 | .013* |

| Conscientiousness | .06 [−.04, .16] | 1.21 | .225 |

| Extraversion | .01 [−.10, .12] | 0.18 | >.250 |

| Agreeableness | −.03 [−.13, .07] | −0.55 | >.250 |

| Neuroticism | −.02 [−.15, .11] | −0.30 | >.250 |

| Daydream-Fantasy Content | |||

| Openness | .18 [.04, .32] | 2.47 | .014* |

| Conscientiousness | −.00 [−.15, .14] | −0.03 | >.250 |

| Extraversion | −.04 [−.19, .11] | −0.53 | >.250 |

| Agreeableness | −.16 [−.31, −.01] | −2.08 | .037 |

| Neuroticism | .16 [−.03, .35] | 1.63 | .102 |

| Worries-Problems Content | |||

| Openness | −.12 [−.25, .01] | −1.86 | .063 |

| Conscientiousness | −.03 [−.17, .11] | −0.42 | >.250 |

| Extraversion | .09 [−.05, .23] | 1.26 | .209 |

| Agreeableness | .05 [−.09, .19] | 0.67 | >.250 |

| Neuroticism | .33 [.19, .47] | 4.58 | <.001* |

| Stuff-To-Do Content | |||

| Openness | −.07 [−.20, .07] | −0.98 | >.250 |

| Conscientiousness | .04 [−.10, .18] | 0.54 | >.250 |

| Extraversion | .19 [.03, .35] | 2.32 | .020 |

| Agreeableness | −.01 [−.15, .13] | −0.13 | >.250 |

| Neuroticism | .02 [−.11, .16] | 0.32 | >.250 |

| External Surroundings Content | |||

| Openness | .09 [−.05, .24] | 1.22 | .222 |

| Conscientiousness | −.03 [−.17, .10] | −0.50 | >.250 |

| Extraversion | −.03 [−.18, .12] | −0.42 | >.250 |

| Agreeableness | −.12 [−.24, .01] | −1.85 | .064 |

| Neuroticism | −.09 [−.26, .09] | −0.99 | >.250 |

Significant effects (alpha = .005 or .05; see text) are marked by asterisks and bolded text. b = unstandardized coefficient; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval.

As predicted (see Table 7), on occasions when subjects reported mind-wandering, those who were higher in openness endorsed more fantastical-daydream content than did those lower in openness, whereas those higher in neuroticism endorsed more worry-based content than did those lower in neuroticism. (Our expectation that high conscientiousness would predict thinking more about unfulfilled tasks and goals while mind-wandering was not confirmed, even when it was the only predictor modeled, Z = 1.21, p = .226). Personality did not otherwise influence subjects’ experiences of mind-wandering (see supplemental Table S2). That is, the fact that off-task thoughts were generally reported as less pleasant and clear, and more out of control, strange, racing, and suspicious (see prior discussion of Table 5) did not change significantly with personality. So, for example, subjects high in openness did not differentially experience mind-wandering as especially more pleasant than on-task thought, despite their more frequently engaging in fantasy; nor did subjects high in neuroticism experience mind-wandering as especially less pleasant than on-task thought, despite their more frequently engaging in worry.

Personality and Contextual Predictors of Mind-Wandering and Related Experiences

In contrast to the executive-ability constructs, none of the personality factors moderated the influence of in-the-moment concentration on mind-wandering, or of any other theoretically coherent contextual influences, such as momentary happiness, irritability, anxiety, sadness, activity effort, or stressful situations (see supplemental Table S3). So, for example, openness predicted daily-life mind-wandering regardless of how relaxed subjects felt at the time. Neuroticism similarly failed to predict mind wandering regardless of how irritable or anxious subjects felt. Conscientiousness did not predict mind wandering even when people reported engaging in effortful activities.

Our final analyses tested for the influences of personality on other subjective qualities of thought in the moment (collapsed across occasions of on-task and off-task thinking, as with the cognitive-predictor analyses; see Table 8). With alpha = .005, almost all of the significant effects were driven by neuroticism, agreeableness, and extraversion. Subjects who were higher in neuroticism reported less pleasant and clear thoughts, and more racing thoughts, than did those lower in neuroticism. More highly agreeable subjects endorsed more pleasant thoughts and less strange, suspicious, and externally controlled thoughts than did less agreeable subjects. Subjects who were higher in extraversion reported more racing, strange, and suspicious thoughts than did those lower in extraversion.

Table 8.

Daily-life thought quality outcomes predicted by the personality constructs (standardized and tested simultaneously).

| b [95% CI] | Z | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pleasant | |||

| Openness | −.00 [−.10, .10] | −0.05 | >.250 |

| Conscientiousness | .13 [.02, .24] | 2.38 | .017 |

| Extraversion | .12 [.01, .24] | 2.08 | .037 |

| Agreeableness | .16 [.05, .27] | 2.95 | .003* |

| Neuroticism | −.17 [−.27, −.06] | −3.18 | .001* |

| Strange | |||

| Openness | −.03 [−.10, .05] | −0.73 | >.250 |

| Conscientiousness | −.09 [−.17, −.02] | −2.32 | .020 |

| Extraversion | .12 [.05, .19] | 3.18 | .001* |

| Agreeableness | −.13 [−.22, −.05] | −3.03 | .002* |

| Neuroticism | .08 [.01, .15] | 2.10 | .036 |

| Clear | |||

| Openness | −.00 [−.11, .11] | −0.03 | >.250 |

| Conscientiousness | .19 [.06, .33] | 2.83 | .005 |

| Extraversion | −.04 [−.16, .08] | −0.68 | >.250 |

| Agreeableness | .01 [−.12, .13] | 0.13 | >.250 |

| Neuroticism | −.21 [−.33, −.09] | −3.47 | .001* |

| Hardly Control | |||

| Openness | −.02 [−.13, .09] | −0.38 | >.250 |

| Conscientiousness | −.10 [−.24, .04] | −1.44 | .149 |

| Extraversion | .11 [−.02, .24] | 1.62 | .105 |

| Agreeableness | −.05 [−.20, .09] | −0.69 | >.250 |

| Neuroticism | .17 [.04, .29] | 2.63 | .009 |

| No Thoughts | |||

| Openness | −.12 [−.23, −.01] | −2.07 | .038 |

| Conscientiousness | −.06 [−.17, .05] | −1.04 | >.250 |

| Extraversion | −.03 [−.16, .11] | −0.42 | >.250 |

| Agreeableness | −.07 [−.19, .06] | −0.99 | >.250 |

| Neuroticism | .01 [−.11, .13] | 0.13 | >.250 |

| Racing | |||

| Openness | −.02 [−.15, .12] | −0.25 | >.250 |

| Conscientiousness | −.10 [−.26, .06] | −1.25 | .210 |

| Extraversion | .23 [.09, .37] | 3.27 | .001* |

| Agreeableness | −.05 [−.19, .09] | −0.66 | >.250 |

| Neuroticism | .27 [.11, .42] | 3.41 | .001* |

| Suspicious | |||

| Openness | −.07 [−.15, .01] | −1.74 | .082 |

| Conscientiousness | −.09 [−.17, −.01] | −2.31 | .021 |

| Extraversion | .11 [.04, .19] | 3.09 | .002* |

| Agreeableness | −.12 [−.20, −.04] | −3.00 | .003* |

| Neuroticism | .09 [.01, .16] | 2.25 | .025 |

| Controlled | |||

| Openness | −.04 [−.11, .04] | −0.99 | >.250 |

| Conscientiousness | −.01 [−.08, .06] | −0.19 | >.250 |

| Extraversion | .08 [.01, .15] | 2.13 | .034 |

| Agreeableness | −.13 [−.21, −.05] | −3.29 | .001* |

| Neuroticism | .07 [−.02, .16] | 1.47 | .143 |

Note. Significant effects (p < .005) are marked by asterisks and bolded text. b = unstandardized coefficient; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval.

Discussion

We found not only robust individual differences in daily-life mind-wandering (Kane et al., 2007) that were predicted by cognitive abilities and personality factors, but also suggestive discrepancies between laboratory and daily-life results. Modest but replicable findings in one domain did not arise in the other. To understand individual differences in mind-wandering, then, context matters (Smallwood & Andrews-Hanna, 2013).

Cognitive Individual Differences in Lab Versus Life

Whereas prototypical executive constructs — WMC, attention restraint, attention constraint — correlated with laboratory mind-wandering, they did not outside; indeed, even laboratory TUT rate didn’t significantly predict daily-life mind-wandering (being only marginally significant in the expected direction). Executive abilities, instead, predicted mind-wandering only as a function of subjects’ concentration attempts, replicating and extending Kane et al. (2007): When subjects tried harder to concentrate, those with better executive abilities mind-wandered less than those with worse abilities; when not trying to concentrate, those with better executive abilities mind-wandered more than those with worse abilities. Such contingencies on concentration were not observed, for WMC’s association with mind-wandering, in three laboratory experiments (Smeekens & Kane, 2016). Moreover, the laboratory finding that WMC negatively predicts mind-wandering in challenging but not easy tasks (e.g., McVay & Kane, 2012a; Rummel & Boywitt, 2014) was absent in daily life: subjective effort demanded by activities didn’t moderate the executive constructs’ associations with mind-wandering (contradicting Kane et al.; replicating Marcusson-Clavertz et al., 2016).

Thus, executive abilities that substantially influence laboratory mind-wandering play more circumscribed roles in everyday life, and some variables’ effects on executive associations with laboratory mind-wandering (i.e., task difficulty vs. concentration) may have opposite effects in daily life. In the lab, task difficulty drives executive contributions to reducing TUTs. In everyday life, executive processes serve people’s attempts to concentrate on ongoing activities, regardless of (subjective) difficulty.

The lab–life discrepancy regarding “difficulty” may reflect that subjective feelings of effort (assessed ecologically) don’t map directly to determinants of performance (manipulated in laboratories). Perhaps experiments effect subtle cognitive changes that are either not present or not subjectively detectable in everyday contexts, but which objectively influence mind-wandering by selectively engaging or disengaging critical executive mechanisms (see McVay & Kane, 2012a). After all, many subjectively challenging tasks don’t elicit WMC-related variation in performance because they don’t tap into executive processes of attention restraint or constraint (e.g., Kane, Poole, Tuholski, & Engle, 2006; Smeekens & Kane, 2016). The laboratory may thus be telling us what’s possible about the executive–mind-wandering association, but their implications may be negligible for most everyday conscious experiences.

The ecological “concentration” results may not be replicated in the laboratory due to an inherently restricted range of activities: Lab tasks may not be engaging, important, and challenging enough to elicit maximal concentration efforts from many subjects (compare to action videogames, animated political discussions, or attempts to woo a crush, for example), nor effortless and routine enough to elicit minimal concentration (compare to watching TV, showering, or mowing a lawn). Recreating daily life’s diversity of activities — regarding not just difficulty but also motivated engagement — may be unrealistic even within the most creatively designed and task-inclusive lab setting, especially because adults sometimes choose their daily-life contexts.

Personality Individual Differences In Lab Versus Life

Personality variables elicited similar lab–life dissociations. Supporting prior findings (Jackson et al., 2013; Robison et al., 2017), neuroticism predicted laboratory TUT rates, with higher neuroticism yielding more off-task thought, and openness did not predict laboratory TUTs (Smeekens & Kane, 2016). In daily life, however, we found the reverse: openness predicted mind-wandering, with higher openness reflective of more mind-wandering, but neuroticism did not. Why?

If openness reflects tendencies toward playful and creative fantasy — consistent with the association we found between openness and daydreamy thought content — then more open subjects should engage in more mind-wandering than less open subjects when everyday life provides opportunity (McMillan et al., 2013). But assuming their penchant for daydreaming isn’t pathological, more open subjects shouldn’t have any more difficulty than less open subjects in focusing attention when they must, as in the lab. This idea jibes with correlations between openness and retrospective-questionnaire assessments of positive-constructive daydreaming (e.g., “I find my daydreams are worthwhile and interesting to me;” “I imagine solving all my problems in my daydreams”) but not everyday distractibility (e.g., “At times it is hard for me to keep my mind from wandering;” “My imagination goes around and around in the same circle”; Singer, 1975; Zhiyan & Singer, 1996–97).

Why should neuroticism predict laboratory but not daily-life mind-wandering? Highly neurotic adults may find the laboratory particularly anxiety-arousing for its novelty and its association with evaluation; testing contexts may thus elicit negative self-reflections about competence and ability, or threat of experimenter judgment. These evaluative cues may be especially effective TUT triggers for less emotionally stable students. We had expected neuroticism to similarly predict daily-life mind-wandering — highly neurotic subjects might worry or ruminate excessively (Perkins, Arnone, Smallwood, & Mobbs, 2015). Our findings, however, corroborate arguments that what distinguishes positive and negative outcomes of repetitive thinking in anxiety and depression is not its quantity, but rather its affective valence, its context, and its generality (i.e., level of construal; Watkins, 2008); perhaps this is due, in part, to people avoiding such environments in daily life. Thus, neuroticism may not so much increase propensity for mind-wandering overall — or even in response to negative affect — but it may only increase particularly negative flavors of mind-wandering when it occurs. Indeed, neuroticism specifically predicted worried mind-wandering content in daily life.

The present study went beyond examining mind-wandering content, moreover, to also investigate thought qualities transcending task-relatedness. Executive abilities tended to predict subjective controllability of thought, with poorer executive-task performance associated with less controllable (and, to some extent, more racing and externally controlled) thoughts. Personality also correlated with thought qualities in predictable ways, such as more agreeable subjects reporting more pleasant thoughts and more extraverted subjects reporting more racing thoughts. Students high in neuroticism, particularly, reported less controllable and clear thinking, despite not experiencing more mind-wandering.

These cognitive and personality findings suggest that scientists interested in the causes, contents, and consequences of spontaneous thought might benefit from expanding their investigations beyond overt mind-wandering episodes to additional qualities of subjective cognitive experience. Moreover, we must remember that laboratories are not neutral environments that affect everyone — and everyone’s conscious experiences — equally. Although divergent findings between laboratory and daily-life predictors of mind-wandering might not affect theories about TUT contributions to particular laboratory tasks (e.g., McVay & Kane, 2009, 2012a), they suggest that general mind-wandering theories based largely or completely on laboratory findings do not capture all of mind-wandering’s causes or correlates as it actually occurs in everyday experience.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Award R15MH093771 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) supported this research. The content is the authors’ responsibility and does not necessarily represent official views of NIMH.

Footnotes

Marcusson-Clavertz and colleagues’ (2016) ESM study found that one WMC measure only predicted mind-wandering for subjects with “guilty” daydreaming styles. WMC didn’t interact with cognitive demand (the “concentration required by activity”) to predict mind-wandering, not replicating Kane et al. (2007).

Author Contributions

M. J. Kane, P. J. Silvia, and T. R. Kwapil developed the ESM study concept. All authors contributed to the ESM study design. ESM study testing, data collection, and data management were performed by G. M. Gross, C. A. Chun, B. A. Smeekens, and M. E. Meier; M. J. Kane and T. R. Kwapil performed the ESM data analysis with input from P. J. Silvia; M. J. Kane drafted the manuscript and M. E. Meier, P. J. Silvia, and T. R. Kwapil provided critical revisions. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Contributor Information

Michael J. Kane, University of North Carolina at Greensboro

Georgina M. Gross, University of North Carolina at Greensboro

Charlotte A. Chun, University of North Carolina at Greensboro

Bridget A. Smeekens, University of North Carolina at Greensboro

Matt E. Meier, Western Carolina University

Paul J. Silvia, University of North Carolina at Greensboro

Thomas R. Kwapil, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

References

- Costa PT, McCrae RR. NEOTM Five-Factor Inventory-3 (NEOTM-FFI-3) Lutz, FL: PAR; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Eckes T. Introduction to many-facet Rasch measurement: Analyzing and evaluating rater-mediated assessments. Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Peter Lang; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin MS, Mrazek MD, Anderson CL, Smallwood J, Kingstone A, Schooler JW. The silver lining of a mind in the clouds: Interesting musings are associated with positive mood while mind-wandering. Frontiers in Psychology. 2013;4(583) doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intel Corporation. iESP [Computer software] 2004 Retrieved from http://seattleweb.intel-research.net/projects/ESM/iESP.html.

- Jackson JD, Balota DA. Mind-wandering in younger and older adults: converging evidence from the Sustained Attention to Response Task and reading for comprehension. Psychology and Aging. 2012;27:106–119. doi: 10.1037/a0023933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JD, Weinstein Y, Balota DA. Can mind-wandering be timeless? Atemporal focus and aging in mind-wandering paradigms. Frontiers in Psychology. 2013;4 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00742. (article 742) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane MJ, Brown LE, McVay JC, Silvia PJ, Myin-Germeys I, Kwapil TR. For whom the mind wanders, and when: An experience-sampling study of working memory and executive control in daily life. Psychological Science. 2007;18:614–621. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane MJ, Meier ME, Smeekens BA, Gross GM, Chun CA, Silvia PJ, Kwapil TR. Individual differences in the executive control of attention, memory, and thought, and their associations with schizotypy. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2016;145:1017–1048. doi: 10.1037/xge0000184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane MJ, Poole BJ, Tuholski SW, Engle RW. Working memory capacity and the top-down control of visual search: Exploring the boundaries of “executive attention”. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2006;32:749–777. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.32.4.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killingsworth MA, Gilbert DT. A wandering mind is an unhappy mind. Science. 2010 Nov 12;330:932. doi: 10.1126/science.1192439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krawietz SA, Tamplin AK, Radvansky GA. Aging and mind wandering during text comprehension. Psychology and Aging. 2012;27:951–958. doi: 10.1037/a0028831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson DB, Smallwood J, Davidson RJ. The persistence of thought: Evidence for a role of working memory in the maintenance of task-unrelated thinking. Psychological Science. 2012;23:375–380. doi: 10.1177/0956797611431465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linacre JM. KR-20/Cronbach Alpha or Rasch person reliability: Which tells the “truth”? Rasch Measurement Transactions. 1997;11:580–581. [Google Scholar]

- Linacre JM. FACETS 3.71.4 [Computer software] Chicago, IL: Winsteps; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Maniaci MR, Rogge RD. Caring about carelessness: Participant inattention and its effects on research. Journal of Research in Personality. 2014;48:61–83. [Google Scholar]

- Marcusson-Clavertz D, Cardeña E, Terhune DB. Daydreaming style moderates the relation between working memory and mind wandering: Integrating two hypotheses. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2016;42:451–464. doi: 10.1037/xlm0000180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Sutin AR. Openness to experience. In: Leary MR, Hoyle RH, editors. Handbook of individual differences in social behavior. New York: Guilford; 2009. pp. 257–273. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan RL, Kaufman SB, Singer JL. Ode to positive-constructive daydreaming. Frontiers in Psychology. 2013:4. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00626. article 626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McVay JC, Kane MJ. Conducting the train of thought: Working memory capacity, goal neglect, and mind wandering in an executive-control task. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2009;35:196–204. doi: 10.1037/a0014104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McVay JC, Kane MJ. Does mind wandering reflect executive function or executive failure? Comment on Smallwood and Schooler (2005) and Watkins (2008) Psychological Bulletin. 2010a;136:188–197. doi: 10.1037/a0018298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McVay JC, Kane MJ. Drifting from slow to “D’oh!”: Working memory capacity and mind wandering predict extreme reaction times and executive control errors. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2012a;38:525–549. doi: 10.1037/a0025896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McVay JC, Kane MJ. Why does working memory capacity predict variation in reading comprehension? On the influence of mind wandering and executive attention. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2012b;141:302–320. doi: 10.1037/a0025250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McVay JC, Kane MJ, Kwapil TR. Tracking the train of thought from the laboratory into everyday life: An experience-sampling study of mind-wandering across controlled and ecological contexts. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2009;16:857–863. doi: 10.3758/PBR.16.5.857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehl MR, Gosling SD, Pennebaker JW. Personality in its natural habitat: Manifestations of implicit folk theories of personality in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;90:862–877. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooneyham BW, Schooler JW. The costs and benefits of mind-wandering: A review. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2013;67:11–18. doi: 10.1037/a0031569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. How to use a Monte Carlo study to decide on sample size and determine power. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9:599–620. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus: Statistical analysis with latent variables, User’s guide. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ozer DJ, Benet-Martínez V. Personality and the prediction of consequential outcomes. Annual Review of Psychology. 2006;57:401–421. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins AM, Arnone D, Smallwood J, Mobbs D. Thinking too much: Self-generated thought as the engine of neuroticism. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2015;19:492–498. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robison MK, Gath KI, Unsworth N. The neurotic wandering mind: An individual differences investigation of neuroticism, mindwandering, and executive control. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2017;70:649–663. doi: 10.1080/17470218.2016.1145706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DC. Issues of regularity and control: Confessions of a regularity freak. In: Poon LW, Rubin DC, Wilson BA, editors. Everyday cognition in adulthood and late life. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1989. pp. 84–103. [Google Scholar]

- Rummel J, Boywitt CD. Controlling the stream of thought: Working memory capacity predicts adjustment of mind-wandering to situational demands. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2014;21:1309–1315. doi: 10.3758/s13423-013-0580-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartre J-P. In: The imagination. Williford K, Rudrauf D, translators. New York: Routledge; 1936/2012. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons JP, Nelson LD, Simonsohn U. A 21 word solution. Dialogue: The Official Newsletter of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology. 2012;26:4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Smallwood J, Andrews-Hanna J. Not all minds that wander are lost: The importance of a balanced perspective on the mind-wandering state. Frontiers in Psychology. 2013;4:441. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeekens BA, Kane MJ. Working memory capacity, mind wandering, and creative cognition: An individual-differences investigation in to the benefits of controlled versus spontaneous thought. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts. doi: 10.1037/aca0000046. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X, Wang X. Mind wandering in Chinese daily lives – An experience sampling study. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e44423. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperry SH, Kwapil TR. What can daily life assessment tell us about the bipolar spectrum? Psychiatry Research. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.02.045. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unsworth N. Consistency of attentional control as an important cognitive trait: A latent-variable analysis. Intelligence. 2015;49:110–128. [Google Scholar]