Abstract

There is preclinical and clinical evidence that vagus nerve stimulation modulates both pain and mood state. Mechanistic studies show brainstem circuitry involved in pain modulation by vagus nerve stimulation, but little is known about possible indirect descending effects of altered mood state on pain perception. This possibility is important, since previous studies have shown that mood state affects pain, particularly the affective dimension (pain unpleasantness). To date, human studies investigating the effects of vagus nerve stimulation on pain perception have not reliably measured psychological factors to determine their role in altered pain perception elicited by vagus nerve stimulation. Thus, it remains unclear how much of a role psychological factors play in vagal pain modulation. Here, we present a rationale for including psychological measures in future vagus nerve stimulation studies on pain.

Keywords: vagus nerve, pain, affect, tVNS

Introduction

Modulation of pain perception via vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) has been examined in humans and animals for several years using an invasive approach (iVNS; Randich et al., 1992; Yuan and Silberstein, 2016), and more recently, with non-invasive transcutaneous approaches (tVNS; Busch et al., 2013; Nesbitt et al., 2015). While a number of mechanistic studies in animals have uncovered portions of the mechanism of action underlying vagal-induced pain modulation (Randich et al., 1992; Nishikawa et al., 1999), the entirety of the mechanism in humans remains elusive. Optimal stimulation durations and parameters, and determining which pain modalities are most responsive have yet to be discerned.

Pain perception and modulation, outside of vagus nerve stimulation, is complex. The sensory (nociceptive) and affective components of pain can vary between and within individuals, and the latter psychological aspect of pain weighs heavily on the manner in which pain is perceived (Bushnell et al., 2013). Moreover, cognitive processes (e.g., attention) compared to emotions and mood states differentially modulate the intensity and unpleasantness of pain (Villemure et al., 2003; Loggia et al., 2008; Villemure and Bushnell, 2009). Despite evidence that VNS improves affect, as it is used therapeutically against depression, studies investigating vagal modulation of pain primarily focus on obtaining measures of pain threshold or the sensory (nociceptive) component of pain as measured by pain intensity ratings. Key psychological factors that affect pain such as mood state and attention are not reliably being measured. Thus, it remains unclear as to whether the effects of VNS on pain are, in part, due to modulation of not only the sensory component of pain perception, but also the psychological component.

Here, we discuss the effects of 1) VNS on pain perception, 2) psychological factors on pain perception, and 3) VNS on psychological factors. The known mechanisms of vagal pain modulation are summarized (4), and a proposed model of vagal pain modulation is presented (5) as an impetus for future studies to include psychological measures when examining the effects of VNS on pain perception.

1. The effects of VNS on pain perception

1.1. iVNS modulation of pain perception

Invasive vagus nerve stimulation (iVNS) is a current treatment option for patients with refractory epilepsy and depression. This method of treatment requires an implanted device that provides direct electrical stimulation to the left cervical vagus nerve. The pain relieving effects of vagus nerve stimulation in humans were first observed in patients receiving iVNS for either epilepsy or depression. Incidentally, patients suffering from concomitant migraine or cluster headache reported decreases in frequency and severity of attacks or complete relief after the iVNS implant (Kirchner et al., 2000; Sadler et al., 2002; Hord et al., 2003; Lenaerts et al., 2008), suggesting that iVNS could alter pain in not only animals, as had already been demonstrated, but also in humans. A summary of case reports on six patients who received an iVNS implant to specifically treat migraine and cluster headache concluded that iVNS might be an effective therapy for these conditions as improvement levels in four patients ranged from good to excellent (Mauskop 2005). Similar beneficial effects were observed in patients receiving iVNS for the treatment of chronic daily headache and depression (Cecchini et al., 2009). A more recent proof-of-concept trial found that iVNS may be effective in treating fibromyalgia, as seven of 14 patients progressively attained a minimal clinically important difference after 11 months of iVNS treatment. Furthermore, two of the seven patients no longer fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia. The patients also experienced a decrease in pain ratings to noxious heat stimuli before vs. after iVNS implantation and over the course of 11 months (Lange et al., 2011).

In epilepsy patients, Kirchner et al. (2000) reported a decrease in temporal summation of pain (wind-up) and tonic pressure pain, independent of the iVNS on/off cycle, after 8–14 weeks of iVNS compared to before implantation. One patient in this study suffering from chronic tension-type headache for more than 10 years experienced an 80% reduction of headache after the surgery. In a later study, Kirchner et al. (2006) successfully replicated their findings for tonic pressure pain and also observed a limited but significant inhibitory effect on neurogenic inflammation (axon reflex flare) produced by tonic mechanical pressure (pinching of the fingerfolds) after iVNS implantation. Conversely, Ness et al. (2000) reported significant decreases in thermal pain thresholds in epilepsy patients in response to individual optimal and suboptimal iVNS intensities compared to sham. The increased sensitivity to pain in response to the low intensity iVNS corroborated earlier reports in rats demonstrating that low intensity iVNS induces pro-nociceptive effects in response to heat, whereas high intensity iVNS induced analgesic effects (Ren et al., 1988). The differential parameter effects are discussed further in Section 4. That said, in a subsequent communication, Ness et al. (2001) provided thermal wind-up results similar to those observed in the Kirchner et al. (2000) study, thereby supporting a central pain inhibitory mechanism.

In one case, a patient receiving iVNS for chronic depression experienced complete relief from both depression and chronic back pain after 35 months of iVNS at an optimal setting, but reported an increase in pain intensity ratings in response to acute noxious thermal stimuli during the on phase of iVNS compared to the off phase (Borckardt et al., 2006). Similarly, depressed patients receiving iVNS with different combinations of parameter settings experienced reduced tolerance to painful heat (Borckardt et al., 2005). However, it is difficult to draw conclusions from this study given the few number of participants, the various device settings that potentially render it underpowered, the prevalence of comorbid chronic pain, and the short duration of iVNS stimulation at low intensities. Nevertheless, the measurable changes detected lend support towards vagal modulation of pain despite the undesirable direction. Interestingly, contrary to the experimental findings, two of the participants anecdotally reported relief of their preexisting pain conditions after iVNS implantation. In one of the cases, the patient with chronic low back pain reported he was no longer “bothered” by the pain after implantation. It remains unclear if the intensity of his back pain changed, but evidently the negative affective component of the pain was reduced.

Table 1 summarizes the studies described above. Eight of the 11 iVNS studies discussed here reported significant reductions in pain perception, which demonstrates a potential beneficial impact of iVNS on evoked pain and chronic pain conditions such as headache and low back pain. The studies have limitations such as small sample sizes and the existing pathology can be a confounding factor. Indeed, an inverse correlation between the severity of depression and pain tolerance in iVNS patients has been reported (Borckardt et al., 2005). Some of these limitations, such as the inclusion of proper controls and testing on healthy participants, can now be addressed with non-invasive VNS devices.

Table 1.

Summary of invasive vagus nerve stimulation (iVNS) studies.

| Author | Sample | Parameters | Main Outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain | Affect | |||

| Borckardt et al., 2005 | Depression n = 8 | Combination of: 20 Hz/30 Hz; 130μs/250μs/500μs pw at 0%, 50%, 100% of basline intensity (0–2.75 mA) | ↓ heat tolerance | Not reported |

| Borckardt et al., 2006 | Depression/low back pain n =1 | 10 Hz or 20 Hz, 250μs s or 500μs s pw 0–0.75 mA 30s on, 3–20 min off |

↓ low back pain ↑ experimental pain ratings ns pain thresholds |

↓ depression |

| Cecchini et al., 2009 | Migraine n = 4 | 30 Hz, 500ms pw 1–2.25 mA 30s on, 5min off |

↓ migraine | ↓ depression |

| Hord et al., 2003 | Migraine n = 4 | 30 Hz, 500ms pw ~1.0 mA 30s on, 5min off |

↓ migraine frequency/intensity | Not reported |

| Kirchner et al., 2000 | Epilepsy n = 10 Healthy n = 12 |

30 Hz, 500μs s pw initial: 0.7 ± 0.2 mA final: 1.4 ± 0.3 mA |

↓ wind-up, pressure pain in patients, comorbid migraine ns thermal, mechanical pain | Not reported |

| Kirchner et al., 2006 | Epilepsy n = 9 Healthy n = 9 |

for majority: 20 Hz, 500μs s pw 30s on, 30s off |

↓ tonic pressure pain in patients ↓ axon reflex flux |

Not reported |

| Lange et al., 2011 | Fibromyalgia n = 14 | 20 Hz, 250μs s pw, 1–2 mA 30s on, 5 min off |

↓ fibromyalgia symptoms ↓ heat pain sensitivity ↓ pain intensity |

Not reported |

| Lenaerts et al., 2008 | Migraine n = 10 | Not reported | ↓ migraine frequency | ↓ (ns) mood/anxiety |

| Mauskop 2005 | Migraine n = 6 | 250ms pw, 1.25–2.75mA 7–60s on, 0.2–5 min off, |

↓ migraine/frequency | ↓ prodromal depression |

| Ness et al., 2000 | Epilepsy n = 8 | 30 Hz, 0.5ms pw 1.0–2.75 mA 30s on, 3–5min off |

↓ heat pain thresholds | Not reported |

| Sadler et al., 2002 | Epilepsy/Migraine n = 1 | final: 20 Hz, 250μs s pw 0.25 mA 7s on, 12s off |

↓ migraine frequency | Not reported |

↓, decrease

↑, increase

ns, non-significant

pw, pulse width

1.2. Non-invasive VNS modulation of pain perception

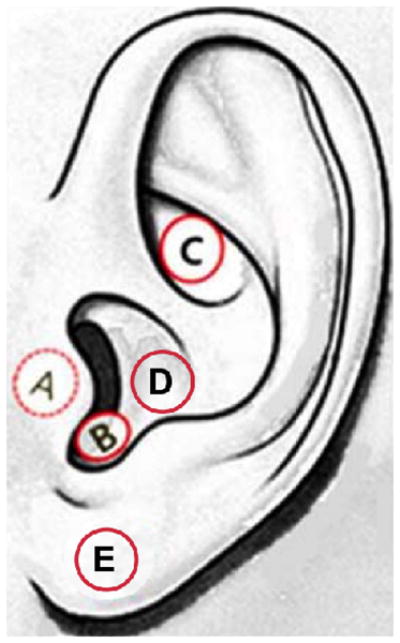

The recent development of transcutaneous (non-invasive) vagus nerve stimulation (tVNS) has made it feasible to test vagal stimulation on not only patients, but healthy participants as well. This non-invasive approach requires mild electrical stimulation of regions of the external surface of the ear that are innervated by the auricular branch of the vagus nerve (ABVN), namely, the posterior and inferior walls of the ear canal, the inner side of the tragus, the cavity of the concha, or the cymba conchae (Fay, 1927; Peuker and Filler, 2002). The cymba conchae region of the ear is the only region of the ear exclusively innervated by the ABVN (Peuker and Filler, 2002), and has been identified as the optimal location for auricular tVNS (Yakunina et al., 2016). Tract-tracing studies in animals and fMRI studies in humans provide evidence that the AVBN projects to the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS), the location of the first central relay of cervical vagal afferents in the medulla region of the brainstem (Nomura & Mizuno, 1984; Berthoud & Neuhuber, 2000; Frangos et al., 2015; Yakunina et al., 2016). Figure 1 depicts the various regions of the ear that have been stimulated in order to gain access to the ABVN; in some cases, the earlobe has been used as an active control.

Figure 1.

The left external ear indicating the regions where tVNS has been applied (A–D) and where control stimulation has been applied (E). A: inner side of the tragus, B: anterior, posterior and/or inferior walls of the ear canal, C: cymba conchae, D: cavum conchae, E: earlobe. (This figure is a modification of Figure 1c. found in Yakunina et al., 2016)

Although comparative studies have yet to be conducted, auricular tVNS is exhibiting similar beneficial effects on drug-resistant epilepsy and treatment-resistant depression as observed with iVNS (Stefan et al., 2012; Hein et al., 2013; Aihua et al., 2014; Bauer et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2016, Fang et al., 2016, Rong et al., 2016).

Auricular tVNS has also shown promising analgesic effects. Examination of the effects of auricular tVNS on various somatosensory modalities in healthy participants shows that, compared to sham, tVNS significantly decreased pain intensity ratings in response to tonic heat pain, decreased mechanical pain sensitivity, and increased mechanical and pressure pain thresholds (Busch et al., 2013). Warm, cold, and mechanical detection thresholds were unaffected, indicating that tVNS specifically modulates pain processes of somatosensation. Frøkjær et al. (2016) observed a significant increase in bone pain (tibia pressure) thresholds in healthy participants, but no effects were observed in muscle pain thresholds and conditioned pain modulation. In a pilot study on chronic pelvic pain patients, a significant reduction of evoked pain intensity and temporal summation of mechanical pain compared to baseline, and a trending reduction compared to control stimulation, was observed after one session of respiratory-gated tVNS. No effects on clinical pain or the affective component of pain (i.e., unpleasantness) were observed, but it is likely that multiple sessions of tVNS are required in order to ascertain meaningful results, particularly in chronic pain patients. Nevertheless, affect was modulated by tVNS as patients experienced a significant anxiolytic effect (Napadow et al., 2012).

Using tVNS stimulation parameters similar to those used during electroacupuncture (burst-stimulation with fluctuating frequencies between 2 Hz and 100 Hz, 0.2 ms pulse-width), Laqua et al. (2014) did not observe an overall effect on pain threshold (electrical stimulation to the finger) with tVNS compared to placebo. Compared to baseline, a significant increase in pain threshold was observed in fifteen participants, while six participants responded with a significant decrease in pain threshold. These effects were not observed with the placebo condition. Based on these findings, the authors concluded that tVNS produced an anti- and pro-nociceptive response, respectively. The variable response could be attributed to either, or a combination of, the fluctuating stimulation parameters, the intensity of the stimulation (although not reported), or the area of the ear being stimulated, i.e., the cavum conchae, which is innervated by not only the ABVN but also, and more so, by the greater auricular nerve (Peuker and Filler, 2002). It is also plausible that the mood state of the participants influenced their pain perception; however, mood was not reported in this study. The same group recently reported similar findings in an fMRI study using a similar paradigm but different stimulation parameters (continuous square-wave stimulation at 8 Hz, 0.2 ms pulse-width). Overall, no significant effects on heat pain thresholds were observed pre- vs. post-tVNS or placebo. However, subgroups with a significant increase or decrease in pain threshold in response to tVNS were once more found (Usichenko et al., 2016). The variable responses could, again, be due to the stimulation parameters, the region of ear stimulation, or the participants’ mood state. Nevertheless, the consistent diametrically opposite responses to vagus stimulation that occurred in both studies, and lack of non-responders, supports the notion that the vagus nerve alters pain perception.

Interestingly, a recent 3-month randomized controlled clinical trial investigating the treatment of chronic migraine with high (25 Hz) vs. low (1 Hz) frequency tVNS found an overall reduction in headache days per 28 days but found a significantly larger reduction with low frequency tVNS, which was the control stimulus (Straube et al., 2015). The greater response to the low frequency stimulation seemingly contradicts previous human and animal studies indicating that low frequency vagal stimulation facilitates pain. However, as the authors point out, analgesic effects in response to low frequency stimulation of other nerves (e.g., spinal or trigeminal) have been shown to induce long-term depression in the spinal system and craniofacial area (Ellrich et al., 2004; Yekta et al., 2006; Aymanns et al., 2009). In the latter case, the resulting suppression of activity in the spinal trigeminal nucleus (STN), a projection of the NTS, could reduce migraine pain. Functional brainstem imaging data shows that auricular tVNS at an equivalent high frequency (25 Hz) activated the STN (Frangos et al., 2015), while non-invasive VNS via the neck (described below), significantly reduced STN activity (Frangos and Komisaruk, 2017) using parameters that are effective against migraine but similar to auricular tVNS.

This more recent approach of tVNS that has also been shown to access central vagal projections (Ay et al., 2015; Frangos and Komisaruk, 2017) works via mild electrical stimulation of the external surface of the neck over the region of the cervical vagus nerve. Using this approach, multiple studies show significant improvement in cluster headache and migraine when used prophylactically and acutely. Reductions in attack frequency, headache days, and depression have been observed. In some cases, nearly half of the attacks were aborted approximately 10min after tVNS (Goadsby et al., 2014; Barbanti et al., 2015; Kinfe et al., 2015; Nesbitt el al., 2015).

In a non-invasive, physiological approach of stimulating the vagus nerve, Sedan et al. (2005) reported that gastric distention, induced by rapidly drinking 1500ml of water to activate vagal afferents, significantly increased heat pain thresholds and decreased sensitivity to tonic heat pain induced by laser. However, mechanical pain threshold and sensitivity to mechanical temporal summation were not significantly affected. Vaginocervical stimulation has also been shown to produce significant analgesic effects that are hypothesized to be mediated by the vagus nerve. These effects were observed in complete spinal cord injured women. The vagus nerve would provide the necessary afferent pathway, as it bypasses the spinal cord and projects directly to the brain (Komisaruk et al., 1997). A subsequent brain imaging study in spinal cord injured women provided evidence in support of this pathway, as vaginal stimulation activated the NTS (Komisaruk et al., 2004).

Overall, tVNS is showing promising results against experimental and chronic pain. Ten of the 12 tVNS studies discussed in Section 1.2, and summarized in Table 2, reported reduced pain, while the other two studies had subgroups experiencing both increased and decreased pain perception. The field is in its infancy and well-controlled longitudinal studies using comparable parameters to investigate the effects of VNS across all sensory modalities are still required. In order to better characterize the effects of VNS on pain, psychological measures must be included in future studies. Tables 1 and 2 convey the dearth of information available about the impact VNS has on the affective component of pain, despite the evidence that affect is modulated by VNS (Cimpianu et al., 2017), and that affect modulates pain (Bushnell et al., 2013). Reducing the affective component of a painful sensation by improving mood, for example, may be another mechanism by which vagus stimulation attenuates pain. The psychological factors that modulate pain are discussed below.

Table 2.

Summary of transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation (tVNS) studies.

| Author | Sample | Parameters | Main Outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain | Affect | |||

| Barbanti et al., 2015 | Migraine n = 50 | At attack onset: two 120s doses of electrical stimulation (parameters not reported), 3min interval, over 2 weeks | ↑ pain relief | Not reported |

| Busch et al., 2013 | Healthy n = 48 | 25 Hz, 0.25ms pw, 1.6 mA ± 1.5 mA 1 hr continuous |

↓ tonic heat pain intensity; mechanical/pressure pain thresholds, mechanical pain sensitivity ns wind-up; thermal detection/pain thresholds; mechanical detection threshold |

Not reported |

| Frøkjær et al., 2016 | Healthy n = 18 | 30 Hz, 250μs s pw 1.46mA ± 0.73mA (final) 1hr |

↑ bone pain threshold ns muscle pain threshold |

Not reported |

| Goadsby et al., 2014 | Migraine n = 30 | At moderate to severe pain: two 90s doses of electrical stimulation (parameters not reported), 15min interval, over 6 weeks | ↓ migraine pain | Not reported |

| Kinfe et al, 2015 | Migraine n = 20 | 1ms burst 5-kHz pulse at 25 Hz, 0 to 24 V for 2min = 1 dose. Prophylactic: 4 doses/day Acute: 2 doses |

↓ headache intensity/frequency ↓ migraine attacks ↑ pain relief |

↓ depression |

| * Komisaruk et al., 1997 | Complete spinal cord injury n = 16 Control n = 5 |

12min vaginocervical stimulation | ↑ pain detection threshold ↑ pain tolerance threshold |

Not reported |

| Laqua et al., 2014 | Healthy n = 22 | 2–100 Hz bursts, 0.2ms pw 30 min |

ns overall ↑ ↓ pain thresholds |

Not reported |

| Napadow et al., 2012 | Chronic pelvic pain n = 15 | 30 Hz, 450μs s pw 0.5s respiratory-gated stimulus 0.43 ± 0.25 mA |

↓ pain intensity, temporal summation ns clinical pain |

↓ anxiety ns pain unpleasantness |

| Nesbitt et al., 2015 | Cluster headache n = 19 | Five 5-kHz pulses at 25Hz for 2min = 1 dose. Prophylactic: up to 3 doses Up to 3 doses/attack |

↓ headache frequency | Not reported |

| * Sedan et al., 2005 | Healthy n = 31 | Ingested 1500 ml of water within 10–12 min | ↑ heat pain threshold ↓ tonic heat pain, laser painns mechanical pain threshold, temporal summation | Not reported |

| Straube et al., 2015 | Migraine n = 46 | 25 Hz or 1 Hz (control), 250μs s pw 30s on/30s off 4h/day, 3 mos |

↓ headache frequency (1Hz > 25Hz) ns headache intensity |

Not reported |

| Usichenko et al., 2016 | Healthy n = 20 | 8Hz, 200μs s pw mean: 7.6mA (range 5.0–11.5) |

ns overall ↑ ↓ heat thresholds |

Not reported |

Stimulation of the vagus nerve was performed non-electrically.

↓, decrease

↑, increase

ns, non-significant

pw, pulse width

2. The effects of psychological factors on pain perception

Robust evidence indicates that psychological factors such as mood, emotions, and attention modify pain perception (for review, refer to Bushnell et al., 2013). Successful experimental manipulations of mood through, e.g., films, music, images, and odors, have been shown to significantly affect pain perception such that positive mood inducing stimuli attenuate pain, while negative stimuli increase pain (Cogan et al., 1987; Zelman et al., 1991; Weisenberg et al., 1998; Meagher et al., 2001; Villemure et al., 2003). Anxiety-inducing stimuli have been shown to decrease pain threshold and induce hyperalgesia (Rhudy and Meagher, 2000; Ploghaus et al., 2001). Chronic pain patients are also detrimentally affected by negative emotional states and attitudes that fluctuate on a daily basis and exacerbate their pain symptoms (Haythornthwaite and Benrud-Larson, 2000; Schanberg et al., 2000).

Distinct psychological factors can modulate pain perception differentially. Pain perception can be divided into a sensory component that can be measured by the intensity of the stinging, burning, and aching sensations, and an affective component that can be measured by the unpleasantness of those sensations. Attentional modulation of pain has distinct effects on pain perception compared to mood. The role of attention in pain modulation preferentially affects perceived pain intensity, whereas mood, or affective state, preferentially modulates the unpleasantness of pain (Villemure et al., 2003; Loggia et al., 2008). Villemure and Bushnell (2009) elucidated the dissociable neural networks of attention and mood underlying the modulation of pain intensity and unpleasantness, respectively. Focusing on odorants during pain stimulation decreased pain intensity ratings along with the pain-induced activity in the anterior insula. The decreased pain intensity ratings correlated with entorhinal cortex and superior posterior parietal cortex activity, suggesting they may be key attention-related pain modulatory regions. The positive mood-inducing odors (independent of attention) decreased unpleasantness and pain-related activation within the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), thalamus, and primary (S1) and secondary (S2) somatosensory cortices. The decreased unpleasantness ratings correlated with the activity in the lateral inferior frontal cortex and the periaqueductal gray (PAG) area, which suggests they are emotion-related pain modulatory regions (Villemure and Bushnell 2009).

3. The effects of VNS on psychological factors

3.1 VNS and affect

The psychological effects of iVNS, particularly on depression, have been well examined, as iVNS is currently an FDA-approved therapy against treatment-resistant depression (Rush et al., 2000; Sackeim et al., 2007). Positive effects on other conditions such as panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder in response to iVNS have also been observed (George et al., 2008). Cimpianu et al. (2017) provide a systematic review of the effects of invasive and non-invasive VNS on psychiatric conditions. The review is predominantly composed of iVNS studies, and therefore, we will focus mainly on tVNS and affect.

Significant beneficial effects against depression, anxiety, and overall mood and well-being have been observed in healthy and chronic pain patients using auricular tVNS (Krause et al., 2007; Hein et al., 2013; Napadow et al., 2012) and tVNS via the neck (Kinfe et al., 2015). Functional brain imaging studies have reported tVNS induced changes in brainstem and limbic regions that may account for the observed positive effects (Kraus et al., 2007, 2013; Dietrich et al., 2008; Frangos et al., 2015; Frangos and Komisaruk, 2017; Yakunina et al., 2016). Of particular interest is the tVNS-induced activation of the locus coeruleus and raphe nuclei, which release norepinephrine and serotonin, respectively, and have significant modulatory roles in pain perception and psychological states and processes.

Auricular tVNS has recently been shown to significantly reduce depression and anxiety in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) after one month of use compared to sham. Reduction of the clinical symptoms significantly correlated with an increase in resting-state functional connectivity between the right amygdala and left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, two regions that have been previously implicated in MDD (Liu et al., 2016; Rong et al., 2016). Functional connectivity between the default mode network (DMN) and brain regions associated with emotion regulation (i.e., the insula and parahippocampus) have also reportedly decreased after one month of tVNS compared to sham stimulation in MDD patients. The change in depression severity significantly correlated with functional connectivity changes between the DMN and regions that are implicated in both pain modulation and emotion such as the anterior insula and ACC (Fang et al., 2016).

The behavioral and brain imaging studies above provide supporting evidence that tVNS improves affect and produces functional changes in brain regions where pain modulation and affect converge. Thus, it is possible that investigations of vagal pain modulation may not be capturing the preferential modulation of affect on pain unpleasantness, as the latter is not reliably reported on (Table 1 and 2).

3.2 VNS and cognition

Evidence of vagal effects on cognition are discussed below and lend support towards the inclusion of attentional measures (which preferentially modulate pain intensity) when investigating vagal pain modulation.

Given the invasive nature of iVNS, a limited number of studies exist solely on the effects of iVNS on cognitive functions. Improvements in motor speed, psychomotor function, verbal fluency, and executive functions such as logic reasoning and working memory have been observed in patients with depression receiving iVNS (Sackeim et al., 2001). Enhanced recognition memory in a verbal task was observed in epileptic patients with iVNS and a similar enhanced retention performance on an inhibitory-avoidance task had been previously observed in rats (Clark et al., 1995, 1999). Increased daytime alertness and vigilance has also been reported in epileptic patients with iVNS and seems to be frequency dependent such that low frequency iVNS produces the increased attentional effect, while high frequency stimulation induces somnolence (Malow et al., 2001; Galli et al., 2003; Rizzo et al., 2003; Serdaroglu et al., 2016).

The extent to which tVNS modulates cognitive functions aside from depression and anxiety is still emergent. In a study on healthy older individuals, acute tVNS compared to sham enhanced associative memory performances on a face-name task (Jacobs et al., 2015). tVNS has also been shown to accelerate fear extinction learning, however a return of fear was observed 24hrs later (Burger et al., 2016). Fear extinction effects in response to vagus stimulation had been previously observed in rats (Peña et al., 2014). In studies using tVNS to modulate the GABA and norepinephrine pathways, tVNS has been shown to increase reaction time and response selection during action cascading (Steenbergen et al., 2015) and to modulate inhibitory control processes during high working memory tasks compared to low working memory tasks (Beste et al., 2016). By contrast, Sellaro et al, (2015) found no effect of tVNS on a reaction time task. However, post-error slowing, which is partially mediated by the noradrenergic system, significantly increased with tVNS compared to sham.

Based on previous studies showing that cognitive processes such as attention preferentially modulates pain intensity such that increased attention to pain increases pain perception, it is possible that some of the pain facilitatory effects of VNS are a result of increased attention to the pain stimulus, a sensation which is inherently attention demanding (Miron et al., 1989). In addition, tVNS produces increased activity in brain regions associated with interoceptive processes such as the insula (Critchley et al., 2004; Kraus et al., 2007, 2013; Dietrich et al., 2008; Frangos et al., 2015; Frangos and Komisaruk, 2017), which may result in greater directed attention towards bodily sensations during the on periods of VNS, compared to the off, as seen in the findings of Borckardt et al. (2006). However, it is also important to point out that the analgesic effects reported by Kirchner et al. (2000) were independent of the on/off cycle of the vagal stimulator.

The trending positive effects of VNS on various cognitive processes, including attention, are further indication that psychological factors should be considered in studies investigating vagal pain modulation.

4. Mechanisms of vagal modulation of pain

Here, we present a summary of the animal literature and human brain imaging studies that elucidate portions of the mechanism of action of vagus nerve stimulation.

The pro- and anti-nociceptive effects of VNS were elucidated in early animal studies. A comprehensive review by Randich and Gebhart (1992) describes the complexity of cervical, thoracic, and cardiac vagal modulation of nociception and the differential effects that electrical stimulation parameters have on inhibition and facilitation of nociception. In the tail-flick reflex test on rats, low intensity stimulation (between 2.5 and 20 μA) produced a facilitatory effect, while high intensity stimulation (•30 μA A) produced inhibition of the reflex. Inhibition, but not facilitation, was found to be dependent on intensity, frequency (no less than 20 Hz), and pulse width (no less than 2ms) of the stimulation (Ren et al., 1988,1991). Unfortunately, optimal stimulation parameters observed in animal studies are not directly translatable to humans, which may account for the lack of consistency of stimulation parameters across human studies.

The anti-nociceptive effects of VNS seem to be primarily dependent on the NTS and its projections to the locus coeruleus and raphe nuclei, followed by the subsequent activation of the descending noradrenergic and serotonergic systems in the spinal cord, including spinal opioid receptors, all of which inhibit second order nociceptive neurons in the spinal cord (Basbaum and Fields, 1978; Randich and Aicher 1988; Ren et al., 1990). Nishikawa et al. (1999) later reported VNS-induced activation of an ascending pain inhibitory pathway from the PAG and raphe nuclei to the ventral posteromedial nucleus of the thalamus. In addition to norepinephrine, serotonin, and opioids, GABA has also been implicated as a possible mediator of VNS-induced analgesia, as it was present in the cerebral spinal fluid of epilepsy patients receiving iVNS (Ben-Menachem et al., 1995) and has been implicated in pain reduction with transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) treatments (Maeda et al., 2007; Johnson et al., 2011). Trigeminal nociception has been counteracted by both invasive and non-invasive VNS as measured by a reduction of formalin-induced Fos-expression in the STN with a reduction of pain-related behavior on the side of the facial nociceptive stimulus (Bohotin et al., 2003), and a reduction of STN extracellular glutamate induced by glyceryl trinitrate, a headache trigger (Oshinsky et al., 2014). Vagal stimulation may also reduce nociception by activating propriospinal neurons in cervical spinal segments 1–3 that project to, and inhibit, spinothalamic tract neurons below C3 (Zhang et al., 1996, 2003; Chandler et al., 2002). Access to propriospinal neurons may be possible via a small percentage of vagal afferent fibers from the nodose ganglion that project to the upper cervical spinal cord (McNeill et al., 1991).

Evidence of vagal access to the descending and ascending pain inhibitory pathways elucidated in animal studies is also supported by human tVNS functional MRI studies that report activation of the NTS, raphe nuclei, locus coeruleus, and periaqueductal gray, as well as other regions implicated in pain modulation such as the nucleus cuneiformis and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Dietrich et al., 2008; Frangos et al., 2015; Yakunina et al., 2016; Frangos and Komisaruk 2017). Imaging studies on iVNS and tVNS report activity within other vagal projection sites such as the insula, thalamus, amygdala, hippocampus, postcentral gyrus, nucleus accumbens, hypothalamus, and prefrontal cortex (Bohning et al., 2001; Ring et al., 2000; Van Laere et al., 2000; Vonck et al., 2000; Lomarev et al., 2002; Narayanan et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2003; Nahas et al., 2007; Dietrich et al., 2008; Kraus et al., 2007, 2013; Frangos et al., 2015; Frangos and Komisaruk, 2017). Many of these regions also respond to and modulate pain, e.g., the insula, somatosensory cortices, thalamus, and prefrontal cortex (Apkarian et al., 2005; Bushnell et al., 2013). Recently, pain responsive brain regions were reportedly modulated by tVNS (Usichenko et al., 2016). In response to painful thermal stimulation, the insula, thalamus, and ACC were activated, and when coupled with tVNS, the activity in the ACC decreased, while amygdala activity increased. Activity in the secondary somatosensory cortex (S2), posterior insula, ACC, and caudate nucleus was correlated with the heat stimulation, while only right anterior insula activity correlated with the heat stimulation during tVNS. The anterior insula has been implicated in modulating the perception of pain. Specifically, shifting attention away from pain decreases pain intensity and pain-evoked activity in the anterior insular cortex (Villemure and Bushnell, 2009).

Inflammatory conditions that produce or are induced by pain may also improve with VNS as descending vagal signals activate anti-inflammatory pathways that suppress secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNFα and IL-1 IL β, Borovikova et al., 2000), which could subsequently ameliorate associated pain. Yuan and Silberstein (2016) provide an up-to-date review on VNS and the anti-inflammatory response.

5. Proposed model of vagal pain modulation

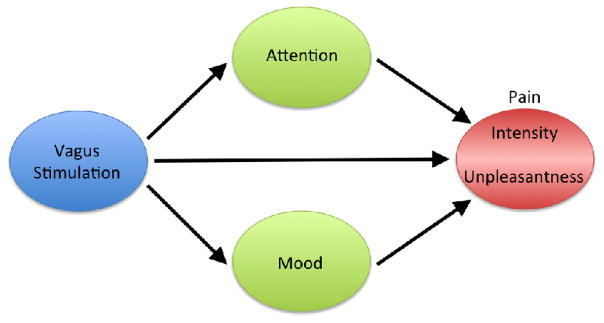

The studies discussed in Section 1 provide evidence that stimulation of vagal afferents produces significant, and in some cases, clinically significant analgesic effects in healthy participants and patient populations. Nevertheless, some discrepancies exist and further work is necessary in order to fully elucidate the mechanism by which VNS modulates pain perception in both favorable and unfavorable directions. To this end, we propose a new model that includes psychological variables that have previously been shown to modulate pain perception and that are also modulated by vagal stimulation. With few exceptions, investigators have focused on the effects of VNS on psychological factors or on pain. Future studies investigating vagal modulation of pain should include measures of psychological factors, such as mood and attention, as they significantly interact with the way pain is perceived. Figure 2 depicts the direct effects that VNS has on pain perception, as well as the psychological variables (i.e., attention and mood) that can differentially modulate the components of pain (i.e., intensity and unpleasantness). Inclusion of these factors may better characterize the role of the vagus nerve in the perception of pain, and may help resolve the discrepancies in the literature.

Figure 2.

Model of vagal pain modulation. Stimulation of the vagus nerve can modulate pain directly through the descending pain inhibitory system, through attentional modulation that can preferentially modulate pain intensity, and/or through induced mood changes that can preferentially modulate the unpleasantness associated with pain.

Additional factors to consider that may also result in discrepant findings are the duration, parameters, and location of VNS stimulation. It is worth noting that many of the VNS studies described above are testing acute effects of vagal stimulation, which may produce immediate significant changes in pain responsive brain regions but not necessarily behavioral responses, as observed in the study by Usichenko et al. (2016). Four-weeks of tVNS reduced clinical symptoms in MDD patients and produced resting-state functional connectivity changes in associated neural-networks (Fang et al., 2016). Thus, more longitudinal studies are required to gain a better understanding of the potential persisting affects of vagal stimulation.

While increased pain perception in response to VNS may be a function of stimulation parameters, it is also likely that possible increased attention, alertness, and vigilance in response to VNS may increase attention to evoked pain and thereby increase pain intensity. An occurrence of increased pain perception in response to VNS is, indeed, a response and evidence of vagal modulation of pain. Thus, participants with such reactions should not be deemed “unresponsive”, as that would, by definition, indicate that VNS neither increased nor decreased pain perception. Pro-nociceptive effects in response to vagal stimulation are intriguing phenomena that warrant further examination.

It is also possible that in a true case of unresponsiveness, as measured by pain threshold or pain intensity ratings, VNS may, indeed, be having an effect on a component of pain that is not being measured, i.e., the unpleasantness associated with pain, which can be independent of the perceived pain intensity. In other words, it is possible that in cases where VNS either increases or has no effect on pain (as measured by intensity), it may also be decreasing the unpleasantness associated with the pain, as noted in the anecdotal comments of one of the patients in a previous study (Borckhardt et al., 2005) who was no longer “bothered” by his existing pain. Furthermore, a decrease in pain unpleasantness in response to VNS may be attributed to improved affect, which evidently has not been reliably measured in studies investigating the effects of VNS on pain. To this effect, based on the findings reported in Usichenko et al. (2016), one could argue that tVNS may have possibly increased mood and decreased pain unpleasantness as the activity in the secondary somatosensory cortex, which is associated with coding the affective component of pain, i.e., unpleasantness, was no longer associated with the painful heat stimulation during tVNS.

In conclusion, the present studies discussed provide preliminary evidence in humans that stimulation of the vagus nerve alters the way pain is perceived and the findings corroborate early reports in animals. The present studies also provide evidence that the vagus nerve alters psychological processes that are known to modulate pain perception differentially. It remains unclear as to whether VNS-induced psychological effects partially mediate vagal pain modulation. However, evidence of vagal-induced analgesia and vagal-induced improvement in mood, together with the known psychological effects on pain perception strongly indicate a need for including psychological measures in future studies investigating the effects of vagus nerve stimulation on pain.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research program of the NIH, National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health.

Abbreviations

- ABVN

auricular branch of the vagus nerve

- ACC

anterior cingulate cortex

- DMN

default mode network

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- fMRI

functional magnetic resonance imaging

- GABA

gamma-aminobutyric acid

- IL

interleukin

- iVNS

invasive vagus nerve stimulation

- MDD

major depressive disorder

- NTS

nucleus tractus solitarius

- PAG

periaqueductal gray

- STN

spinal trigeminal nucleus

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- VNS

vagus nerve stimulation

- tVNS

transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Aihua L, Lu S, Liping L, Xiuru W, Hua L, Yuping W. A controlled trial of transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation for the treatment of pharmacoresistant epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2014;39:105–10. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Apkarian AV, Bushnell MC, Treede RD, Zubieta JK. Human brain mechanisms of pain perception and regulation in health and disease. Eur J Pain. 2005;9:463–484. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ay I, Nasser R, Simon B, Ay H. Transcutaneous cervical vagus nerve stimulation ameliorates acute ischemic injury in rats. Brain Stimul. 2015;9(2):166–73. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2015.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aymanns M, Yekta SS, Ellrich J. Homotopic long-term depression of trigeminal pain and blink reflex within one side of the human face. Clin Neurophysiol. 2009;120:2093–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2009.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barbanti P, Grazzi L, Egeo G, Padovan AM, Liebler E, Bussone G. Non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation for acute treatment of high-frequency and chronic migraine: an open-label study. J Headache Pain. 2015;16:61. doi: 10.1186/s10194-015-0542-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basbaum AI, Fields HL. Endogenous pain control mechanisms: Review and hypothesis. Ann Neurol. 1978;4:451–62. doi: 10.1002/ana.410040511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bauer S, Baier H, Baumgartner C, Bohlmann K, Fauser S, Graf W, et al. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation (tVNS) for treatment of drug-resistant epilepsy: a randomized, double-blind clinical trial (cMPsE02) Brain Stimul. 2016;9(3):356–63. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ben-Menachem E, Hamberger A, Hedner T, Hammond EJ, Uthman BM, Slater J, et al. Effects of vagus nerve stimulation on amino acids and other metabolites in the CSF of patients with partial seizures. Epilepsy Res. 1995;20:221–7. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(94)00083-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berthoud HR, Neuhuber WL. Functional and chemical anatomy of the afferent vagal system. Auton Neurosci. 2000;85:1–17. doi: 10.1016/S1566-0702(00)00215-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beste C, Steenbergen L, Sellaro R, Grigoriadou S, Zhang R, Chmielewski W, et al. Effects of Concomitant Stimulation of the GABAergic and Norepinephrine System on Inhibitory Control - A Study Using Transcutaneous Vagus Nerve Stimulation. Brain Stimul. 2016;9(6):811–8. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bohning DE, Lomarev MP, Denslow S, Nahas Z, Shastri A, George MS. Feasibility of vagus nerve stimulation-synchronized blood oxygenation level-dependent functional MRI. Invest Radiol. 2001;36(8):470–9. doi: 10.1097/00004424-200108000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bohotin C, Scholsem M, Multon S, Martin D, Bohotin V, Schoenen J. Vagus nerve stimulation in awake rats reduces formalin-induced nociceptive behavior and fos-immunoreactivity in trigeminal nucleus caudalis. Pain. 2003;101:3–12. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00301-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borckardt JJ, Kozel FA, Anderson B, Walker A, George MS. Vagus nerve stimulation affects pain perception in depressed adults. Pain Res Manag. 2005;10(1):9–14. doi: 10.1155/2005/256472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borckardt JJ, Anderson B, Andrew Kozel F, Nahas Z, Richard Smith A, Jackson Thomas K, Kose S, George MS. Acute and long-term VNS effects on pain perception in a case of treatment-resistant depression. Neurocase. 2006;12(4):216–20. doi: 10.1080/13554790600788094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borovikova LV, Ivanova S, Zhang M, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation attenuates the systemic inflammatory response to endotoxin. Nature. 2000;405:458–62. doi: 10.1038/35013070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burger AM, Verkuil B, Van Diest I, Van der Does W, Thayer JF, Brosschot JF. The effects of transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation on conditioned fear extinction in humans. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2016;132:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Busch V, Zeman F, Heckel A, Menne F, Ellrich J, Eichhammer P. The effect of transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation on pain perception - an experimental study. Brain Stimul. 2013;6:202–9. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bushnell MC, Ceko M, Low LA. Cognitive and emotional control of pain and its disruption in chronic pain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013 Jul;14(7):502–11. doi: 10.1038/nrn3516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cecchini AP, Mea E, Tullo V, Curone M, Franzini A, Broggi G, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation in drug-resistant daily chronic migraine with depression: preliminary data. Neurol Sci. 2009;30(Suppl 1):S101–4. doi: 10.1007/s10072-009-0073-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chandler MJ, Zhang J, Qin C, Foreman RD. Spinal inhibitory effects of cardiopulmonary afferent inputs in monkeys: neuronal processing in high cervical segments. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87:1290–302. doi: 10.1152/jn.00079.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cimpianu CL, Strube W, Falkai P, Palm U, Hasan A. Vagus nerve stimulation in psychiatry: a systematic review of the available evidence. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2017;124(1):145–158. doi: 10.1007/s00702-016-1642-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clark KB, Krahl SE, Smith DC, Jensen RA. Post-training unilateral vagal stimulation enhances retention performance in the rat. Neurobiol of Learn Mem. 1995;63:213–6. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1995.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clark KB, Naritoku DK, Smith DC, Browning RA, Jensen RA. Enhanced recognition memory following vagus nerve stimulation in human subjects. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:94–98. doi: 10.1038/4600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cogan R, Cogan D, Waltz W, McCue M. Effects of laughter and relaxation on discomfort thresholds. J Behav Med. 1987;10:139–44. doi: 10.1007/BF00846422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Critchley HD, Wiens S, Rotshtein P, Ohman A, Dolan RJ. Neural systems supporting interoceptive awareness. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7(2):189–95. doi: 10.1038/nn1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dietrich S, Smith J, Scherzinger C, Hofmann-Preiss K, Freitag T, Eisenkolb A, Ringler R. A novel transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation leads to brainstem and cerebral activations measured by functional MRI. Biomed Tech (Berl) 2008;53:104–11. doi: 10.1515/BMT.2008.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ellrich J, Schorr A. Low-frequency stimulation of trigeminal afferents induces long-term depression of human sensory processing. Brain Res. 2004;996:255–8. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.08.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fang J, Rong P, Hong Y, Fan Y, Liu J, Wang H, et al. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation modulates default mode network in major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(4):266–73. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fay T. Observations and results from intracranial section of glossopharyngeus and vagus nerves in man. J Neurol Psychopathol. 1927;8:110–23. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.s1-8.30.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frangos E, Ellrich J, Komisaruk BR. Non-invasive access to the vagus nerve central projections via electrical stimulation of the external ear: fMRI evidence in humans. Brain Stimul. 2015;8(3):624–36. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2014.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frangos E, Komisaruk BR. Access to vagal projections via cutaneous electrical stimulation of the neck: fMRI evidence in healthy humans. Brain Stimul. 2017;10(1):19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2016.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frøkjær JB, Bergmann S, Brock C, Madzak A, Farmer AD, Ellrich J, Drewes AM. Modulation of vagal tone enhances gastroduodenal motility and reduces somatic pain sensitivity. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;28(4):592–8. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Galli R, Bonanni E, Pizzanelli C, Maestri M, Lutzemberger L, Giorgi FS, et al. Daytime vigilance and quality of life in epileptic patients treated with vagus nerve stimulation. Epilepsy Behav. 2003;4(2):185–91. doi: 10.1016/s1525-5050(03)00003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.George MS, Ward HE, Jr, Ninan PT, Pollack M, Nahas Z, Anderson B, et al. A pilot study of vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) for treatment-resistant anxiety disorders. Brain Stimul. 2008;1(2):112–121. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goadsby PJ, Grosberg BM, Mauskop A, Cady R, Simmons KA. Effect of noninvasive vagus nerve stimulation on acute migraine: an open-label pilot study. Cephalalgia. 2014;34(12):986–93. doi: 10.1177/0333102414524494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haythornthwaite JA, Benrud-Larson LM. Psychological aspects of neuropathic pain. Clin J Pain. 2000;16:S101–S105. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200006001-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hein E, Nowak M, Kiess O, Biermann T, Beyerlein K, Kornhuber J, Kraus T. Auricular transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in depressed patients: a randomized controlled pilot study. J Neural Transm. 2013;120:821–7. doi: 10.1007/s00702-012-0908-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hord ED, Evans MS, Mueed S, Adamolekun B, Naritoku DK. The effect of vagus nerve stimulation on migraines. J Pain. 2003;4(9):530–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jacobs HI, Riphagen JM, Razat CM, Wiese S, Sack AT. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation boosts associative memory in older individuals. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36(5):1860–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson MI, Bjordal JM. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for the management of painful conditions: focus on neuropathic pain. Expert Rev Neurotherapeut. 2011;11:735–53. doi: 10.1586/ern.11.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kinfe TM, Pintea B, Muhammad S, Zaremba S, Roeske S, Simon BJ, Vatter H. Cervical non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation (nVNS) for preventive and acute treatment of episodic and chronic migraine and migraine-associated sleep disturbance: a prospective observational cohort study. J Headache Pain. 2015;16:101. doi: 10.1186/s10194-015-0582-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kirchner A, Birklein F, Stefan H, Handwerker HO. Left vagus nerve stimulation suppresses experimentally induced pain. Neurology. 2000;55:1167–71. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.8.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kirchner A, Stefan H, Bastian K, Birklein F. Vagus nerve stimulation suppresses pain but has limited effects on neurogenic inflammation in humans. Eur J Pain. 2006;10(5):449–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Komisaruk BR, Gerdes CA, Whipple B. “Complete” spinal cord injury does not block perceptual responses to genital self-stimulation in women. Arch Neurol. 1997;54:1513–20. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1997.00550240063014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Komisaruk BR, Whipple B, Crawford A, Liu WC, Kalnin A, Mosier K. Brain activation during vaginocervical self-stimulation and orgasm in women with complete spinal cord injury: fMRI evidence of mediation by the vagus nerves. Brain Res. 2004;1024:77–88. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kraus T, Hösl K, Kiess O, Schanze A, Kornhuber J, Forster C. BOLD fMRI deactivation of limbic and temporal brain structures and mood enhancing effect by transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation. J Neural Transm. 2007;114:1485–93. doi: 10.1007/s00702-007-0755-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kraus T, Kiess O, Hösl K, Terekhin P, Kornhuber J, Forster C. CNS BOLD fMRI effects of sham-controlled transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in the left outer auditory canal e a pilot study. Brain Stimul. 2013;6(5):798–804. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2013.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lange G, Janal MN, Maniker A, Fitzgibbons J, Fobler M, Cook D, Natelson BH. Safety and efficacy of vagus nerve stimulation in fibromyalgia: a phase I/II proof of concept trial. Pain Med. 2011;12(9):1406–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01203.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Laqua R, Leutzow B, Wendt M, Usichenko T. Transcutaneous vagal nerve stimulation may elicit anti- and pro-nociceptive effects under experimentally-induced pain - a crossover placebo-controlled investigation. Auton Neurosci. 2014;185:120–2. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2014.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lenaerts ME, oommen KJ, Couch JR, Skaggs V. Can vagus nerve stimulation help migraine? Cephalalgia. 2008;28(4):392–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu J, Fang J, Wang Z, Rong P, Hong Y, Fan Y, et al. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation modulates amygdala functional connectivity in patients with depression. J Affect Disord. 2016;205:319–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu WC, Mosier K, Kalnin AJ, Marks D. BOLD fMRI activation induced by vagus nerve stimulation in seizure patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:811–3. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.6.811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Loggia ML, Mogil JS, Bushnell MC. Experimentally induced mood changes preferentially affects pain unpleasantness. J Pain. 2008;9(9):784–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lomarev M, Denslow S, Nahas Z, Chae JH, George MS, Bohning DE. Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) synchronized BOLD fMRI suggests that VNS in depressed adults has frequency/dose dependent effects. J Psychiatr Res. 2002;36(4):219–27. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(02)00013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maeda Y, Lisi TL, Vance CG, Sluka KA. Release of GABA and activation of GABAA receptors in the spinal cord mediates the effects of TENS in rats. Brain Res. 2007;1136:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.11.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Malow BA, Edwards J, Marzec M, Sagher O, Ross D, Fromes G. Vagus nerve stimulation reduces daytime sleepiness in epilepsy patients. Neurology. 2001;57:879–84. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mauskop A. Vagus nerve stimulation relieves chronic refractory migraine and cluster headaches. Cephalalgia. 2005;25(2):82–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2005.00611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McNeill DL, Chandler MJ, Fu QG, Foreman RD. Projection of nodose ganglion cells to the upper cervical spinal cord in the rat. Brain Res Bull. 1991;27(2):151–5. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(91)90060-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Meagher MW, Arnau RC, Rhudy JL. Pain and emotion: effects of affective picture modulation. Psychosom Med. 2001;63:79–90. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200101000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Miron D, Duncan GH, Bushnell MC. Effects of attention on the intensity and unpleasantness of thermal pain. Pain. 1989;9(3):345–52. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(89)90048-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nahas Z, Teneback C, Chae JH, et al. Serial vagus nerve stimulation functional MRI in treatment-resistant depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32(8):1649–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Napadow V, Edwards RR, Cahalan CM, et al. Evoked pain analgesia in chronic pelvic pain patients using respiratory-gated auricular vagal afferent nerve stimulation. Pain Med. 2012;13:777–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2012.01385.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Narayanan JT, Watts R, Haddad N, Labar DR, Li PM, Filippi CG. Cerebral activation during vagus nerve stimulation: a functional MR study. Epilepsia. 2002;43(12):1509–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.16102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nesbitt A, Marin JCA, Tompkins E, Ruttledge M, Goadsby P. Initial use of a novel noninvasive vagus nerve stimulator for cluster headache treatment. Neurology. 2015;84(12):1249–53. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ness TJ, Fillingim RB, Randich A, Backensto EM, Faught E. Low intensity vagal nerve stimulation lowers human thermal pain thresholds. Pain. 2000;86:81–5. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00237-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ness TJ, Randich A, Fillingim R, Faught RE, Backensto EM. Comment on: Left vagus nerve stimulation suppresses experimentally induced pain. Neurology. 2001;56(7):985–6. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.7.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nishikawa Y, Koyama N, Yoshida Y, Yokota T. Activation of ascending antinociceptive system by vagal afferent input as revealed in the nucleus ventralis posteromedialis. Brain Res. 1999;833:108–11. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01521-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nomura S, Mizuno N. Central distribution of primary afferent fibers in the Arnold’s nerve (the auricular branch of the vagus nerve): a transganglionic HRP study in the cat. Brain Res. 1984;292:199–205. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90756-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Oshinsky ML, Murphy AL, Hekierski H, Jr, Cooper M, Simon BJ. Noninvasive vagus nerve stimulation as treatment for trigeminal allodynia. Pain. 2014;155(5):1037–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Peña DF, Childs JE, Willett S, Vital A, McIntyre CK, Kroener S. Vagus nerve stimulation enhances extinction of conditioned fear and modulates plasticity in the pathway from the ventromedial prefrontal cortex to the amygdala. Front Behav Neurosci. 2014;8:327. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Peuker ET, Filler TJ. The nerve supply of the human auricle. Clin Anat. 2002;15:35–7. doi: 10.1002/ca.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ploghaus A, Narain C, Beckmann CF, Clare S, Bantick S, Wise R, et al. Exacerabation of pain by anxiety is associated with activity in a hippocampal network. J Neurosci. 2001;21(24):9896–903. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-24-09896.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Randich A, Aicher A. Medullary substrates mediating antinociception produced by electrical stimulation of the vagus. Brain Res. 1988;445:68–76. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91075-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Randich A, Gebhart GF. Vagal afferent modulation of nociception. Brain Res Rev. 1992;17(2):77–99. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(92)90009-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ren K, Randich A, Gebhart GF. Effects of electrical stimulation of vagal afferents on spinothalamic tract cells in the rat. Pain. 1991;44(3):311–9. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(91)90102-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ren K, Randich A, Gebhart GF. Modulation of spinal nociceptive transmission from nuclei tractus solitarii: a relay for effects of vagal afferent stimulation. J Neurophysiol. 1990;63(5):971–86. doi: 10.1152/jn.1990.63.5.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ren K, Randich A, Gebhart GF. Vagal afferent modulation of a nociceptive reflex in rats: involvement of spinal opioid and monoamine receptors. Brain Res. 1988;446(2):285–94. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90887-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rhudy JL, Meagher MW. Fear and anxiety: divergent effects on human pain thresholds. Pain. 2000;84(1):65–75. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00183-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ring HA, White S, Costa DC, Pottinger R, Dick JP, Koeze T, et al. A SPECT study of the effect of vagal nerve stimulation on thalamic activity in patients with epilepsy. Seizure. 2000;9(6):380–4. doi: 10.1053/seiz.2000.0438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rizzo P, Beelke M, De Carli F, Canovaro P, Nobili L, Robert A, et al. Chronic vagus nerve stimulation improves alertness and reduces rapid eye movement sleep in patients affected by refractory epilepsy. Sleep. 2003;26(5):607–11. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.5.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rong P, Liu J, Wang L, Liu R, Fang J, Zhao J, et al. Effect of transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation on major depressive disorder: a nonrandomized controlled pilot study. J Affect Disord. 2016;195:172–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rush AJ, George MS, Sackeim HA, Marangell LB, Husain MM, Giller C, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) for treatment-resistant depressions: a multicenter study. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47:276–86. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00304-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sackeim HA, Brannan SK, Rush AJ, George MS, Marangell LB, Allen J. Durability of antidepressant response to vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007;10(6):817–26. doi: 10.1017/S1461145706007425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sackeim HA, Keilp JG, Rush AJ, George MS, Marangell LB, Dormer JS, et al. The effects of vagus nerve stimulation on cognitive performance in patients with treatment-resistant depression. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol. 2001;14(1):53–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sadler RM, Purdy RA, Rahey S. Vagal nerve stimulation aborts migraine in patient with intractable epilepsy. Cephalalgia. 2002;22(6):482–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2002.00387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schanberg LE, Sandstrom MJ, Starr K, Gil KM, Lefebvre JC, Keefe FJ, et al. The relationship of daily mood and stressful events to symptoms in juvenile rheumatic disease. Arthritis Care Res. 2000;13:33–41. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200002)13:1<33::aid-art6>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sedan O, Sprecher E, Yarnitsky D. Vagal stomach afferents inhibit somatic pain perception. Pain. 2005;113(3):354–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sellaro R, van Leusden JWR, Tona KD, Verkuil B, Nieuwenhuis S, Colzato LS. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation enhances post-error slowing. J Cogn Neurosci. 2015;27(11):2126–32. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Serdaroglu A, Arhan E, Kurt G, Erdem A, Hirfanoglu T, Aydin K, Bilir E. Long term effect of vagus nerve stimulation in pediatric intractable epilepsy: an extended follow-up. Childs Nerv Syst. 2016;32(4):641–6. doi: 10.1007/s00381-015-3004-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Steenbergen L, Sellaro R, Stock AK, Verkuil B, Beste C, Colzato LS. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation (tVNS) enhances response selection during action cascading processes. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;25(6):773–8. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2015.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Stefan H, Kreiselmeyer G, Kerling F, Kurzbuch K, Rauch C, Heers M, et al. Transcutaneous vagus nerve stimulation (t-VNS) in pharmacoresistant epilepsies: a proof of concept trial. Epilepsia. 2012;53:e115–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Straube A, Ellrich J, Eren O, Blum B, Ruscheweyh R. Treatment of chronic migraine with transcutaneous stimulation of the auricular branch of the vagal nerve (auricular t-VNS): a randomized, monocentric clinical trial. J Headache Pain. 2015;16:543. doi: 10.1186/s10194-015-0543-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Usichenko T, Laqua R, Leutzow B, Lotze M. Preliminary findings of cerebral responses on transcutaneous vagal nerve stimulation on experimental heat pain. Brain Imaging Behav. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s11682-015-9502-5. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Van Laere K, Vonck K, Boon P, Brans B, Vandekerckhove T, Dierckx R. Vagus nerve stimulation in refractory epilepsy: SPECT activation study. J Nucl Med. 2000;41(7):1145–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Villemure C, Bushnell MC. Mood Influences Supraspinal Pain Processing Separately from Attention. J Neurosci. 2009;29(3):705–15. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3822-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Villemure C, Slotnick BM, Bushnell MC. Effects of odors on pain perception: deciphering the roles of emotion and attention. Pain. 2003;106(1–2):101–8. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(03)00297-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Vonck K, Boon P, Van Laere K, D’Havé M, Vandekerckhove T, O’Connor S, et al. Acute single photon emission computed tomographic study of vagus nerve stimulation in refractory epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2000;41(5):601–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb00215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Weisenberg M, Raz T, Hener T. The influence of film-induced mood on pain perception. Pain. 1998;76:365–75. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yakunina N, Kim SS, Nam EC. Optimization of Transcutaneous Vagus Nerve Stimulation Using Functional MRI. Neuromodulation. 2016 doi: 10.1111/ner.12541. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yekta SS, Lamp S, Ellrich J. Heterosynaptic long-term depression of craniofacial nociception: divergent effects on pain perception and blink reflex in man. Exp Brain Res. 2006;170:414–22. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-0226-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Yuan H, Silberstein SD. Vagus nerve and vagus nerve stimulation, a comprehensive review: part III. Headache. 2016;56(3):479–90. doi: 10.1111/head.12649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zelman DC, Howland EW, Nichols SN, Cleeland CS. The effects of induced mood on laboratory pain. Pain. 1991;46:105–11. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(91)90040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zhang J, Chandler MJ, Foreman RD. Cardio-pulmonary sympathetic and vagal afferents excite C1–C2 propriospinal cells in rats. Brain Res. 2003;969:53–8. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02277-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zhang J, Chandler MJ, Foreman RD. Thoracic visceral inputs use upper cervical segments to inhibit lumbar spinal neurons in rats. Brain Res. 1996;709:337–42. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01441-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]