Abstract

Platinum drugs are the frontline therapy in many carcinomas, including high-grade serous ovarian cancers. Clinically, high-grade serous carcinomas have an apparent complete response to carboplatin, but tumors invariably recur and response to platinum drugs diminishes over time. Standard of care prohibits re-administration of platinum drugs to these patients who are labeled as having platinum-resistant disease. In this stage patients are treated with non-platinum agents and outcomes are often poor. In vivo and in vitro data presented here demonstrate that this clinical dogma should be challenged. Platinum drugs can be an effective therapy even for platinum-resistant carcinomas as long as they are combined with an agent that specifically targets mechanisms of platinum resistance exploited by the therapy-resistant tumor subpopulations. High levels of cellular inhibitor of apoptosis proteins cIAP1 and 2 (cIAP) were detected in up to 50% of high-grade serous and non-high-grade serous platinum-resistant carcinomas. cIAP proteins can induce platinum resistance and they are effectively degraded with the drug birinapant. In platinum-resistant tumors with ≥22.4 ng of cIAP per 20 μg of tumor lysate, the combination of birinapant with carboplatin was effective in eliminating the cancer. Our findings provide a new personalized therapeutic option for patients with platinum-resistant carcinomas. The efficacy of birinapant in combination with carboplatin should be tested in high-grade serous carcinoma patients in a clinical trial.

INTRODUCTION

Platinum drugs were discovered in 1965 by Barnett Rosenberg,1 and were fast-tracked through the NIH for the treatment of cancers. Platinum agents demonstrated unprecedented efficacy in a number of malignancies, and continue to be used clinically in therapy of many epithelial cancers. Platinum drugs are widely used in the treatment of metastatic ovarian, colorectal, lung, cervical, and bladder carcinomas (reviewed in refs 2 and 3). While the initial response to platinum agents is often favorable, resistance is commonly encountered (reviewed in refs 2 and 3). At this point, options are limited and clinical outcomes are often grim.

High-grade serous carcinomas (HGSCs) of the ovary, fallopian tube, and endometrium are platinum-sensitive carcinomas, as >80% of patients with advanced disease have a therapeutic response to these drugs.4 Given the efficacy of carboplatin, it was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration as the frontline therapy for HGSC patients. But despite this initial favorable response, 85% of patients relapse within 16 months from the start of treatment.5 In clinical practice, HGSCs are defined as platinum resistant when they relapse within 6 months of platinum therapy (reviewed in ref. 6). On the other hand, if the disease relapses more than 6 months from the time of last platinum exposure, the patient is classified as having platinum-sensitive disease (reviewed in ref. 6). This clinical classification is arbitrary, with crucial implications for the patient. Women with platinum-resistant disease are not retreated with carboplatin (reviewed in ref. 6). Instead second-line agents (i.e., bevacizumab, topotecan, etoposide, pemetrexed, or doxorubicin) are administered, with poor survival outcomes of mere months.7–11

We have previously shown that high levels of cIAP proteins (cIAP1 and 2) in the CA125 negative cancer-initiating cells of chemo-naive primary patient HGSC specimens induces platinum resistance.12 But this therapeutic challenge could be overcome when birinapant, a SMAC mimetic that efficiently degrades cIAP proteins,13 was combined with carboplatin.12 The combination of birinapant and carboplatin could improve disease-free interval in mice bearing human HGSC tumors.12 However, several biologic questions remain unanswered. (a) Could the combination of birinapant and carboplatin improve overall survival (OS) in preclinical HGSC disease models by eradicating platinum-resistant cells? (b) Could this combination therapy effectively target platinum-resistant non-HGSC carcinomas as well? (c) What is the frequency of HGSC and non-HGSC carcinomas sensitive to birinapant and carboplatin combination therapy? (d) Can levels of cIAP, the birinapant target, be predictive of a favorable response to this combination treatment?

Here, we demonstrate that platinum-resistant carcinomas can be successfully eradicated with carboplatin. Success of this approach hinges on coupling platinum therapy with a pharmacologic agent such as birinapant, tailored to target mechanisms of platinum resistance specifically utilized by the therapy-resistant populations of a tumor. High levels of cIAP protein were found in up to 50% of platinum-resistant carcinomas and these tumors were sensitive to birinapant and carboplatin co-therapy. Our findings suggest that existing standards of care for treating platinum-resistant disease should be re-examined and could be personalized with the addition of a platinum-sensitizing agent tailored to the patient′s tumor. Data here suggest that levels of cIAP protein in the platinum-resistant tumor cells may serve as a guide for selecting the patients that could benefit from birinapant and carboplatin co-therapy.

RESULTS

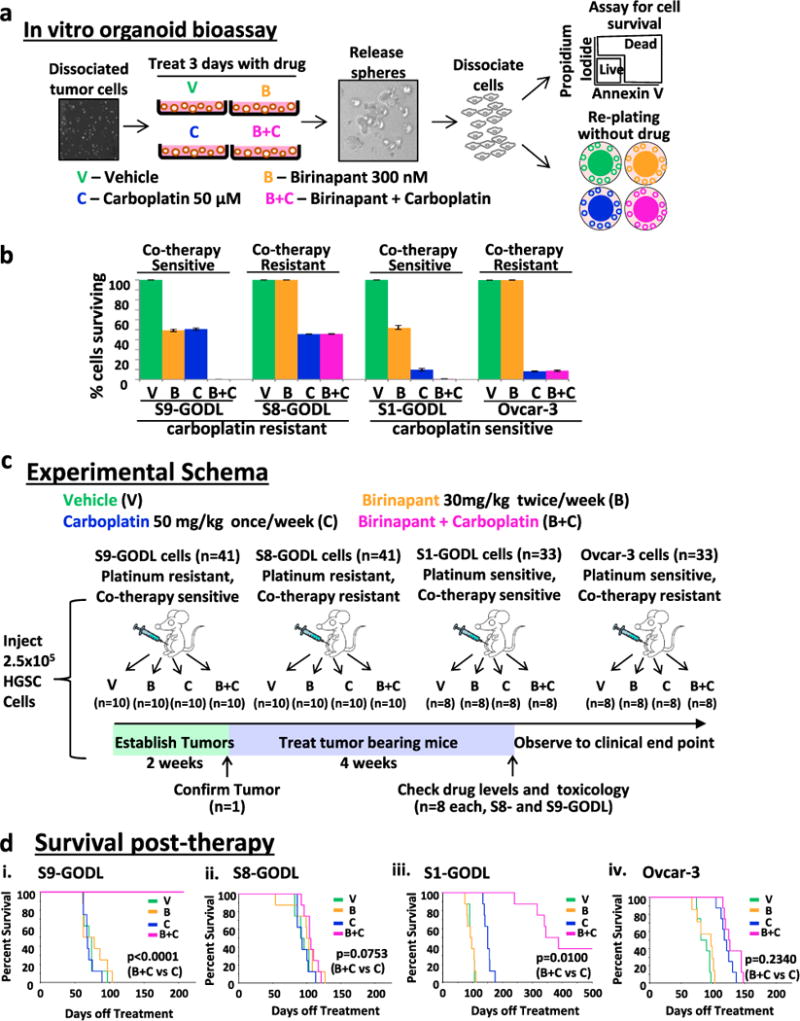

Platinum-resistant tumor cells could be eradicated in vivo when carboplatin was combined with birinapant

To determine if the combination of birinapant and carboplatin (co-therapy) could improve OS in physiologic models of platinum-resistant HGSC, two cell lines (S8-GODL and S9-GODL, established from platinum-resistant primary patient HGSCs) were utilized. In past studies, a minor platinum-resistant population was detected even in platinum-sensitive HGSCs.12 Therefore, the platinum-sensitive cell lines S1-GODL and Ovcar-3 were analyzed alongside the platinum-resistant lines. The response of all four cell lines to birinapant and carboplatin was first examined using an in vitro organoid bioassay (Fig. 1a, b). This bioassay utilized two independent tests to determine response to co-therapy: assessment of (a) cell survival using flow cytometry (Fig. S1A) and (b) organoid formation from cells surviving therapy (Fig. S1B). Based on this assay, S9-GODL cells were predicted to be sensitive to co-therapy (Fig. 1b), while S8-GODL cells were predicted to be co-therapy resistant (Fig. 1b). As previously demonstrated,12 S1-GODL and Ovcar-3 cells were co-therapy sensitive and resistant, respectively (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

OS of mice bearing bioassay positive platinum-resistant or sensitive human HGSCs improved with birinapant and carboplatin co-administration. a. Organoids treated with drug for 72 h were released, dissociated, and analyzed for survival by flow cytometry and passaging. Sensitivity to co-therapy was defined as ≤1% survival and no growth after passaging. b Graph showing the percentage of cells that survived treatment. Co-therapy sensitive lines S9-GODL and S1-GODL were eliminated, while co-therapy resistant lines S8-GODL and Ovcar-3 survived co-therapy. Results are mean ± SD, n = 3 replicates/cell line. c Experimental schema to assess the in vivo efficacy of birinapant and carboplatin co-therapy. Mice bearing IP human HGSCs were randomized to receive a 4-week course of vehicle, birinapant, carboplatin, or the combination of birinapant and carboplatin (n = minimum 8/arm). Mice were euthanized when they met NIH-defined endpoint criteria. d OS increased in mice bearing S9-GODL and S1-GODL tumors. (i) Co-therapy significantly increased OS in mice bearing platinum-resistant S9-GODL HGSC tumors (p < 0.0001, co-therapy vs. carboplatin). (ii) Co-therapy did not impact survival of mice bearing platinum-resistant S8-GODL tumors (p = 0.0753, co-therapy vs. carboplatin). (iii) Mice bearing platinum-sensitive S1-GODL tumors had increased OS with co-therapy (p = 0.01, co-therapy vs. carboplatin). (iv) Co-therapy did not improve OS in mice bearing Ovcar-3 tumors (p = 0.2340, co-therapy vs. carboplatin)

Survival assays were performed on mice bearing intraperitoneal (IP) tumors established from one of the four individual HGSC cell lines (Fig. 1c). Tumor take was confirmed in one mouse from each cohort (Fig. S1C). Remaining mice were randomized into treatment arms to receive a 4-week course of vehicle, birinapant (30 mg/kg IP 2×/week), carboplatin (50 mg/kg IP 1×/week), or co-therapy (Fig. 1c). Carboplatin and birinapant could be detected in serum using this dosing strategy (Fig. S1D). Survival analysis was performed on these mice, which were only euthanized upon meeting NIH-defined endpoint criteria.14

In mice bearing platinum-resistant S9-GODL tumors OS was significantly improved in the arm receiving co-therapy compared with arms receiving vehicle, birinapant, or carboplatin monotherapy (p ≤ 0.0002, Fig. 1d(i), Tables S1 and S2). Median survival of mice in this cohort receiving co-therapy more than doubled compared with carboplatin treatment alone (Fig. 1d(i), Table S1 and S2). In contrast, co-therapy provided no survival benefit compared with vehicle or any other treatment in mice bearing S8-GODL tumors (p ≥ 0.08, Fig. 1d(ii), Tables S1 and S2). The in vivo response of S9-GODL and S8-GODL tumor cells to co-therapy was in agreement with results seen in the in vitro organoid bioassay (Fig. 1b). Monotherapy with birinapant or carboplatin did not increase OS of mice bearing S9-GODL or S8-GODL platinum-resistant HGSC tumors compared with vehicle (p= 0.80, p= 0.91 and p = 0.25, p = 0.92, respectively, Fig. 1d(i–ii), Tables S1 and S2).

Co-therapy doubled median survival of mice bearing platinum-sensitive S1-GODL tumors compared with carboplatin (p= 0.01, Fig. 1d(iii), Tables S1 and S2), but was ineffective in mice bearing platinum-sensitive Ovcar-3 tumors (p = 0.2340, Fig. 1d(iv), Tables S1 and S2). Similarly, S1-GODL tumor cells were co-therapy sensitive, while Ovcar-3 tumor cells were co-therapy resistant based on results in the in vitro organoid bioassay (Fig. 1b). Birinapant monotherapy had no impact on OS in these two cohorts (p = 0.96, p = 0.50, respectively, Fig. 1d(iii–iv), Tables S1 and S2), while carboplatin monotherapy improved OS compared with vehicle (p = 0.0734, p = 0.0068, respectively, Fig. 1d(iii–iv), Tables S1 and S2).

Given the clear in vivo efficacy of co-therapy in a subset of HGSC tumors, blood and organs from co-therapy-treated mice were carefully analyzed for any signs of toxicity. Examination of blood immediately after co-therapy in a cohort of mice (n = 4/treatment group) did not reveal any additional hematologic, liver, or kidney toxicity compared with carboplatin alone (Fig. S2A). To assess for any potential long-term organ damage due to co-therapy, organs from euthanatized mice were examined by an expert pathologist. As all S9-GODL tumor-bearing mice treated with co-therapy were alive, here we examined organs from euthanized S1-GODL mice that had a longer follow-up time. There was no sign of toxicity in the co-therapy-treated mice based on this analysis (Fig. S2B).

Necropsy of four S1-GODL co-therapy-treated mice euthanized due to non-HGSC-related causes revealed no evidence of carcinoma (Fig. S3A–C). Disease with an acquired resistant phenotype to birinapant was found in one S1-GODL co-therapy-treated mouse (Fig. S4). Unlike the S1-GODL parental line, tumor cells from the abdominal wash of this mouse survived co-therapy in the in vitro organoid bioassay (Fig. S4A(i)). cIAP2 was not degraded in these tumor cells despite birinapant administration (Fig. S4A(ii)), while knockdown of cIAP2 sensitized them to co-therapy (Fig. S4B(i, ii)). Findings suggest that the inability of birinapant to degrade cIAP2 is causing this acquired resistant phenotype possibly due to loss of Traf2, required for efficient degradation of cIAP213 (Fig. S4A(ii)). Tumor cells from this mouse also had a diminished response to carboplatin likely due to the expansion of the CA125 negative platinum-resistant population (Fig. S4C).

Survival assays in mice bearing S9-GODL tumors derived from a platinum-resistant carcinoma demonstrate that platinum-resistant cancers can be effectively treated with carboplatin as long as a platinum-sensitizing agent tailored to the tumor is co-administered. Survival assays in mice bearing platinum-sensitive tumors provide further proof that eradication of even the minor population of platinum-resistant cells found in these carcinomas12 is required for achieving long-term remissions. The in vivo response of each of the four tumors to co-therapy was accurately predicted using our in vitro organoid bioassay. To estimate the frequency of tumors that would be sensitive to this combination therapy, the efficacy of co-therapy was investigated in a cohort of primary clinical HGSC samples and non-HGSC carcinoma cell lines.

Birinapant overcomes platinum resistance in approximately 50% of carcinomas tested

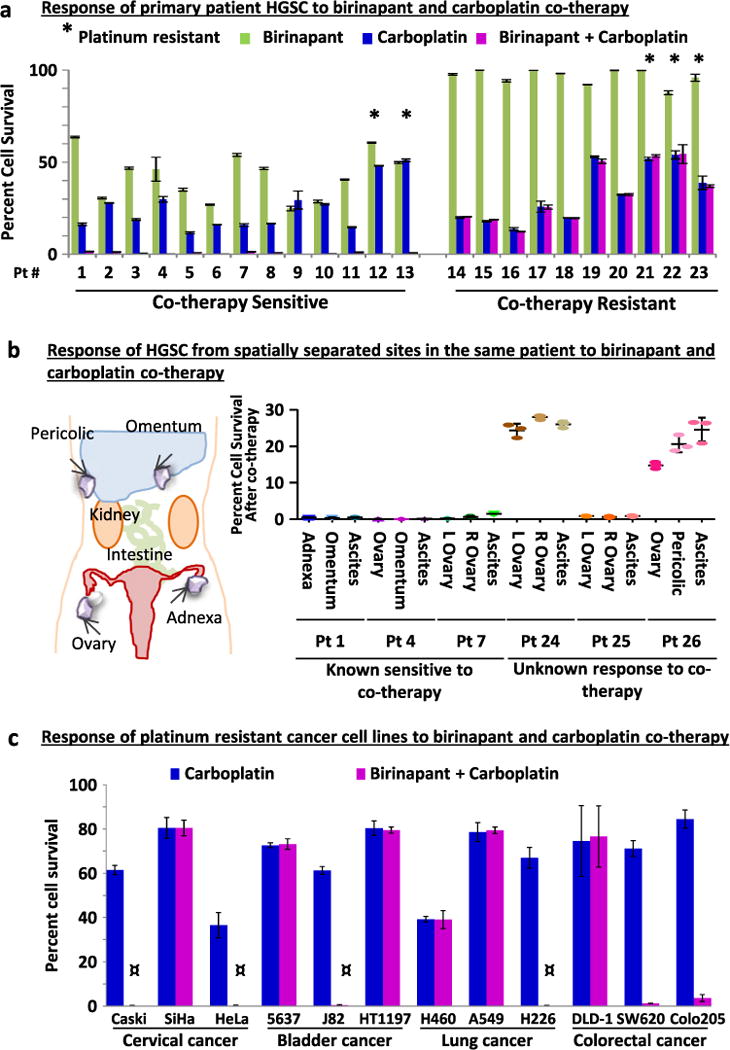

Dramatic response to birinapant and carboplatin co-therapy was observed in vivo, where HGSC tumor cells were completely eliminated. However, this therapeutic response was only seen in tumors established from two of the four cell lines tested. To estimate the frequency of a therapeutic response to birinapant and carboplatin co-therapy, its efficacy was tested in a cohort of 23 primary patient HGSC samples (15 chemo-naive, 1 recurrent platinum-sensitive, 5 platinum resistant and 2 neoadjuvant treated) (Fig. 2a, Table S3). Here, the in vitro organoid bioassay was utilized (Fig. 1a). In 13/23 clinical samples tested, no surviving cells were detected by flow cytometry and cells did not grow when passaged after treatment (Fig. 2a, Fig. S5A), indicating that these tumors were co-therapy sensitive. In contrast, 10/23 clinical samples were co-therapy resistant evidenced by survival of >1% of cells by flow cytometry and robust growth upon passaging (Fig. 2a, Fig. S5A). Vehicle or monotherapy did not eliminate any HGSCs (Fig. 2a, Fig. S5A). Based on these two measures, approximately 50% of primary patient HGSC samples were co-therapy sensitive.

Fig. 2.

Half of HGSC and non-HGSC carcinomas tested were sensitive to carboplatin and birinapant co-therapy. a Assessment of cell survival after drug treatment in the in vitro organoid bioassay (n = 3 replicates/specimen) revealed that in a cohort of 23 randomly selected primary patient HGSC specimens 13 were sensitive to co-therapy, while 10 were resistant. Single asterisk denotes samples clinically defined as platinum resistant. b Analysis of matched tumor specimens (three replicates/specimen) collected from spatially separated sites in the same patient (n = 6 patients) demonstrated that sensitivity to birinapant and carboplatin co-therapy was shared in multi-site HGSCs. c The response of platinum-resistant cell lines from cervical, bladder, lung, or colorectal cancers (n = 3 each) to co-therapy was examined in the in vitro organoid bioassay (n = 3 replicates/cell line). Half of the cell lines tested (CaSki, HeLa, J82, H226, SW620, and Colo2O5) were effectively targeted with co-therapy. In four of these cell lines (denoted by the symbol) no surviving cells could be detected by flow cytometry. In all six co-therapy sensitive lines, no growth was detected upon re-plating without drug. Results are mean ± SD

HGSC is a metastatic disease; tumor cells can spread from the site of origin throughout the peritoneal cavity. Recent whole genome sequencing studies of matching tumors from different sites in the same patient suggest divergence of the genomic profile in multi-site disease.15, 16 This raises the possibility that tumors from spatially separated sites in the same patient would have different responses to co-therapy. To examine this possibility, three patients were identified who had multi-site tumor specimens bio-banked. One tumor from each patient had previously been tested in the in vitro organoid bioassay and was found to be co-therapy sensitive (patients 1, 4, and 7; Fig. 2a). Disease from two additional sites from each of these patients was then tested in parallel with the originally examined tumor sample and similarly found to be co-therapy sensitive (Fig. 2b). Next, the sensitivity of multi-site disease was examined in tumors from three additional patients (patients 24, 25, and 26; Table S3). The response of these tumors to co-therapy was unknown as none of these specimens were previously tested. Here, we found that when one site of disease was co-therapy resistant, all sites of disease from the same patient did not respond to co-therapy (Fig. 2b). Similarly, if one site of disease was co-therapy sensitive, this sensitivity was shared in tumors from other sites harvested from the same patient (Fig. 2b). Collectively these results suggest that response to co-therapy is conserved despite the metastatic nature of HGSCs. This conserved response to co-therapy in multi-site disease is likely a consequence of low mutation frequency of cIAP genes (Fig. S5B).

Platinum resistance is a clinical challenge encountered in many carcinomas and cellular mechanisms causing platinum resistance can be shared in tumors irrespective of their site of origin.3, 17 Given that the addition of birinapant to carboplatin could overcome platinum resistance in approximately 50% of HGSCs tested, we next examined whether combination therapy could also effectively target other platinum-resistant carcinomas. The in vitro organoid bioassay was utilized to test the efficacy of co-therapy in platinum-resistant cell lines originating from the cervix,18 bladder,19 lung,20–22 and colon20 (n = 3 each tumor type, Table S4). Here, 6 of 12 cell lines tested were eliminated upon treatment with birinapant and carboplatin (Fig. 2c). A favorable response to co-therapy was not exclusive to any disease site tested (Fig. 2c), suggesting that this combination approach can be effective in a wide variety of carcinomas.

While half of the carcinomas tested thus far could be eliminated with co-therapy, the other half was found to be co-therapy resistant. cIAP proteins are the target for birinapant; therefore, cIAP levels were measured and compared in carcinomas classified as co-therapy sensitive or resistant.

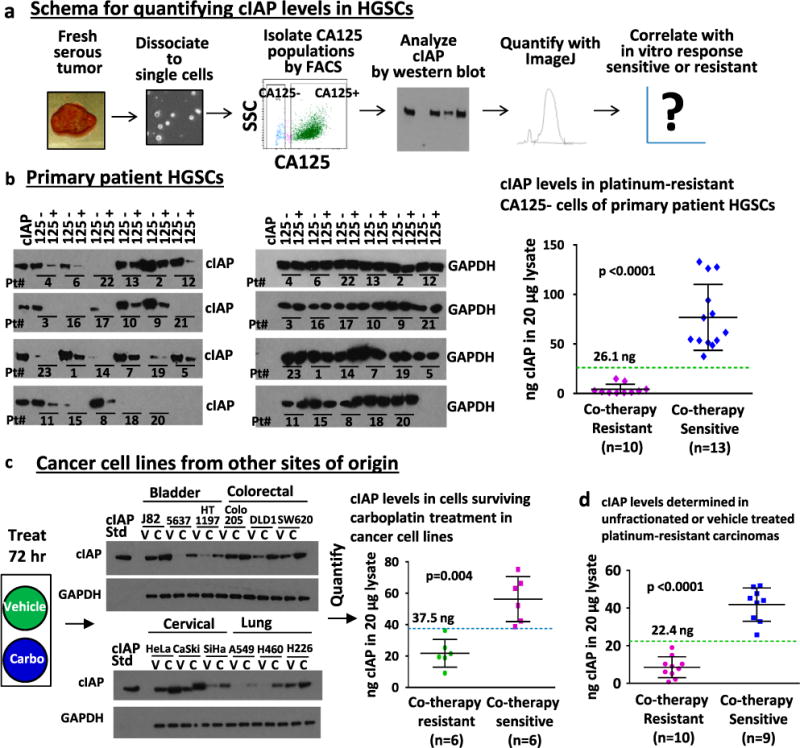

Levels of cIAP protein in platinum-resistant cells were predictive of response to carboplatin and birinapant co-therapy

Given that HGSC cells lacking detectable expression of cell surface CA125 (CA125 negative) were platinum resistant and the cells sensitized to carboplatin with the addition of birinapant,12 cIAP levels were first investigated in this population. The 23 primary patient HGSCs and four HGSC cell lines were fractionated based on CA125 expression. On average a two-fold higher percentage of CA125 negative cells were found in platinum-resistant and neoadjuvant-treated compared with chemo-naive and recurrent platinum-sensitive HGSCs (Fig. S6A). Equal microgram amounts of protein lysate were analyzed by western blot (Fig. 3a, b, Fig. S6B–D). For each specimen, levels of cIAP in CA125 negative cells (which are enriched for platinum-resistant populations) were correlated with response to co-therapy. A threshold midpoint of 26.1 ng of cIAP (threshold range 14.8–37.4 ng cIAP) in 20 μg of CA125 negative cell lysate segregated co-therapy sensitive vs. resistant primary HGSCs with 100% accuracy (p < 0.0001, Fig. 3b). Levels of cIAP in CA125 negative cells of co-therapy sensitive S9-GODL and S1-GODL cell lines were above this threshold midpoint, while levels of cIAP in co-therapy resistant Ovcar-3 and S8-GODL cell lines were below this threshold midpoint (Fig. S6E). Signaling mechanisms that may be responsible for heightened expression of cIAP in CA125 negative cells remain to be elucidated.

Fig. 3.

Analysis of cIAP levels by western blot effectively segregated co-therapy sensitive vs. resistant HGSCs. a Schema for analysis of cIAP levels in HGSCs by semi-quantitative western blot and its correlation with co-therapy response. b cIAP protein levels were measured in 20 μg of lysate from the CA125 negative and positive HGSC populations and compared with a 40 ng standard of cIAP1 and 2 (20 ng each) included on each blot. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a loading control. Levels of cIAP expression, quantified for each sample using ImageJ, were plotted against in vitro response to co-therapy. The expression of cIAP in the CA125 negative cells was significantly higher in co-therapy sensitive (>26.1 ng in 20 μg lysate) compared with co-therapy resistant (<26.1 ng in 20 μg lysate) HGSCs (p < 0.0001). c Levels of cIAP expression were determined in platinum-resistant non-HGSC carcinoma cell lines. Cells were treated for 72 h with vehicle (as control) or carboplatin (to enrich for platinum-resistant cells). Significantly higher cIAP expression was observed after carboplatin treatment in co-therapy sensitive compared with co-therapy resistant cell lines (threshold midpoint 37.5 ng cIAP in 20 μg cell lysate, threshold range 36.3–38.7 ng cIAP, p = 0.004). d Analysis of all platinum-resistant samples (HGSC and non-HGSC) demonstrates that cIAP levels in unfractionated or vehicle-treated tumor cells can segregate co-therapy sensitive (n = 9) vs. co-therapy resistant (n = 10) carcinomas in clinically defined platinum-resistant disease (threshold midpoint 22.4 ng cIAP in 20 μg cell lysate, threshold range 19.1–25.8 ng cIAP, 100% accuracy, p < 0.0001)

Elevated expression of IAPs has been linked to therapy resistance in non-HGSC carcinomas (reviewed in refs 23 and 24). Our analysis of platinum-resistant bladder, cervix, colon, and lung cancer cell lines demonstrated that a subset of these tumors could also be effectively targeted with co-therapy. Therefore, we next measured levels of cIAP protein in these cell lines. Unlike the HGSCs, we could not physically isolate the platinum-resistant populations based on cell surface markers; here, we utilized drug selection with carboplatin to enrich for the platinum-resistant population. Carboplatin or vehicle-treated cells were lysed and analyzed for cIAP expression. In cells surviving carboplatin therapy, a threshold midpoint of 37.5 ng of cIAP (threshold range 36.3–38.7 ng cIAP) in 20 μg cell lysate could segregate co-therapy sensitive vs. resistant carcinomas with 100% accuracy (p= 0.004, Fig. 3c).

While measurement of cIAP in isolated platinum-resistant cells could be required in chemo-naive samples composed of a small fraction of platinum-resistant and large fraction of platinum-sensitive cells, we hypothesized that this additional fractionation step may not be necessary in platinum-resistant carcinomas where the tumor is dominated by the platinum-resistant population. To test this hypothesis, cIAP levels were measured in bulk populations of platinum-resistant tumors (unfractionated HGSCs and vehicle-treated non-HGSC cell lines). In these specimens, a threshold midpoint of 22.4 ng cIAP (threshold range 19.1–25.8 ng cIAP) in 20 μg cell lysate segregated co-therapy sensitive vs. resistant specimens with 100% accuracy (p< 0.0001, Fig. 3d, Fig. S6F). This approach was not as successful if chemo-naive and platinum-sensitive specimens were included, likely because they have a lower proportion of platinum-resistant cells. With the inclusion of these specimens a cIAP level of 22.4 ng could still optimally segregate co-therapy sensitive vs. resistant samples (p < 0.0001) but the overall accuracy was compromised to 89.7% (Fig. S6F–G).

Performance of western blot requires snap freezing of tumor tissue and special processing to avoid protein degradation. An alternative method used in clinical practice to score expression of target proteins is immunohistochemistry (IHC). We hypothesized that the percentage of cIAP positive cells measured by IHC could be predictive of response to co-therapy specifically in platinum-resistant samples, where the vast majority of tumor cells are platinum resistant. Histologic sections of the five platinum-resistant primary HGSC samples and paraffin-embedded cell pellets from the 14 platinum-resistant cells lines were immunostained and scored for cIAP expression (Fig. S7A–C). A threshold midpoint of 26.2% and threshold range of 13.5%–38.9% cIAP positive cells (number cIAP positive cells/number total cells in immunofluorescent-stained slides) could accurately segregate co-therapy sensitive vs. resistant samples (p< 0.0001, Fig. S8A–C).

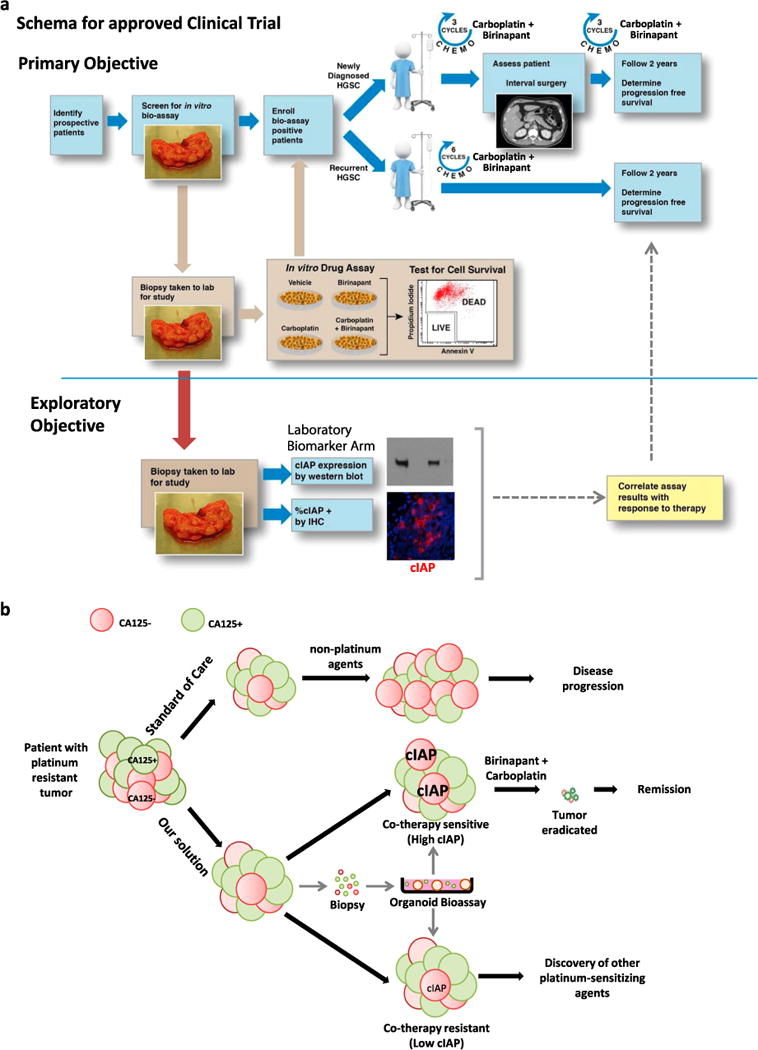

Together, results suggest that evasion of carboplatin-induced apoptosis through cIAP activity is a mechanism of platinum resistance in a subset of carcinomas commonly treated with platinum drugs. Based on these promising preclinical findings, the clinical efficacy of carboplatin and birinapant co-therapy should be investigated. We propose to test the therapeutic efficacy of birinapant and carboplatin co-therapy in women diagnosed with HGSC in a clinical trial (Fig. 4a). Given the predictive value of the in vitro organoid bioassay in identifying tumors responsive to co-therapy in vivo, we propose that only patients whose tumors are found to be co-therapy sensitive in this bioassay (bioassay positive patients) would be enrolled in the trial (Fig. 4a). As an exploratory objective of the trial, the validity of western blot and IHC biomarker assays described in this manuscript should be investigated (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4.

Proposed strategy for overcoming platinum resistance in tumors of patients diagnosed with HGSC. a Schematic for a proposed clinical trial. We propose a proof of concept study aimed at determining the efficacy of birinapant and carboplatin co-therapy in improving survival of women with HGSC. Eligible subjects would be women with newly diagnosed or recurrent HGSC with co-therapy sensitive tumors based on the in vitro organoid bioassay. Patients would be treated with six cycles of carboplatin and concurrently receive the apoptosis-enhancing drug birinapant. Progression free and OS would be assessed and compared with historic controls. The validity of two biomarker assays, western blot and IHC, aimed at measuring levels and percentage of cIAP positive cells would be correlated with response to co-therapy. b Patients with platinum-resistant HGSCs are not re-treated with carboplatin in accordance with existing standards of care. At this point second-line chemotherapy agents are administered but clinical outcomes are often poor. We suggest a different approach that involves treating platinum-resistant HGSCs with carboplatin in combination with a pharmacologic agent (such as birinapant in tumors with high cIAP expression) that overcomes innate mechanisms of platinum resistance in CA125 negative platinum-resistant cells

While platinum drugs are currently not administered to patients with platinum-resistant disease, our study provides compelling evidence that this clinical practice should be re-examined (Fig. 4b). By combining carboplatin with birinapant, long-term remissions were achieved in physiologic disease models (Fig. 4b), a response that could be predicted using the in vitro organoid bioassay.

DISCUSSION

The inevitable challenge and poor outcomes faced in treating patients with platinum-resistant disease has been the driving force behind many decades of research and the life-long mission of numerous investigators (reviewed in refs 2, 3, and 17). A glaring example of this clinical challenge is encountered in therapy of HGSCs where tumors are often responsive to platinum drugs initially but invariably relapse with a platinum-resistant phenotype. Several strategies have been explored to restore platinum sensitivity in HGSCs and some have been tested in clinical trials. Addition of the nucleoside analog gemcitabine to platinum drugs is one such strategy based on synergism of these two drugs in vitro when treating platinum-resistant ovarian cancer cells.25, 26 But when this combination therapy was tested in clinic, overall response rates were low.27 Copper chelating agents enhanced platinum uptake and hence platinum sensitivity of ovarian cancer cell lines.28, 29 The efficacy of one such agent, trientine, was tested in combination with carboplatin in a pilot trial of platinum-resistant ovarian cancer patients. This treatment regimen only achieved partial remission in one of five cases in this trial.30 The DNA methyltransferase inhibitor decitabine was coupled with platinum therapy as it might reactivate genes that may induce platinum sensitivity.31, 32 When used in a clinical trial, this combination showed reduced efficacy compared with platinum alone.33 While these trials were based on extensive preclinical work, their limited success may be due to failure in targeting mechanisms of resistance specifically utilized in the platinum-resistant population of tumor cells.

We hypothesize that many platinum responsive carcinomas are composed of platinum-sensitive and platinum-resistant cells. We have proven this hypothesis in our studies of HGSC tumors12 and in this manuscript further demonstrate that a shift in the balance of platinum-sensitive vs. platinum-resistant populations may be responsible for the emergence of platinum-resistant HGSCs. Work by others, demonstrating that serum CA125 levels may not be predictive of disease progression in patients with platinum-resistant HGSCs,34 supports this finding. Regardless of the clinical classification of the tumor as platinum sensitive or resistant, we think that success in overcoming platinum resistance may be achieved by pinpointing mechanisms of resistance specifically utilized by the platinum-resistant populations. Any therapy combined with platinum drugs must disarm mechanisms of platinum resistance in these cells to provide long-term efficacy. Biomarker assays that can effectively identify the specific mechanism of resistance exploited by the platinum-resistant population will be critical, as the efficacy of combination therapies (platinum plus a drug that overcomes platinum resistance) should be tested in patients with bioassay/biomarker positive tumors. We had previously found that a mechanism inducing platinum resistance in HGSCs is evasion of apoptosis mediated by high levels of cIAP in CA125 negative cells. Degradation of cIAP proteins specifically in the CA125 negative population with the drug birinapant sensitized these cells to carboplatin-induced cell death.12 Here, we find that high levels of cIAP protein detected in tumor populations enriched for platinum-resistant cells is predictive of this therapeutic response in HGSCs and other carcinomas.

Birinapant and carboplatin co-therapy was effective in eliminating 50% of carcinomas tested. To investigate the efficacy of this therapeutic strategy in clinical trials, a means of selecting patients who would benefit the most from co-therapy is required. The in vitro organoid bioassay accurately predicted response to co-therapy for each HGSC cell line tested in vivo. The advantage of the bioassay is its ability to detect response to drug treatment at a cellular level. This assay requires living cells and access to flow cytometry equipment, making it clinically feasible only in centers with specialized expertise. We therefore explored the utility of two additional biomarker assays by performing western blots and IHC measuring levels and percentage of cIAP positive cells in tumors scored as co-therapy sensitive or resistant based on their analysis in the in vitro organoid bioassay. Here, a clear correlation was seen between expression of cIAP protein (the target for birinapant) and response to co-therapy as long as this measurement was performed in tumor cells enriched for the platinum-resistant population.

Historically, IAPs have been recognized as potentially important cancer therapeutic targets (reviewed in refs. 23 and 35). Targeting of IAPs has been achieved with the synthesis of compounds that mimic the action of SMAC (second mitochondrial activator of caspases), a natural regulator of IAP proteins (reviewed in ref. 35). In the vast majority of clinical trials the efficacy of SMAC mimetics is tested in combination with chemotherapy or other targeted therapies.23 The ability of birinapant monotherapy to target platinum-resistant disease was tested in a phase II clinical trial, but this study was terminated due to lack of efficacy.36 In vivo and in vitro preclinical data presented here support that birinapant will not be effective as a monotherapy in treatment of carcinomas (Fig. 1d and Fig. S5A). A clinical trial testing the efficacy of a different IAP inhibitor, Debio 1143 (AT-406) in combination with platinum is planned to launch in biomarker-unselected patients with ovarian cancers. Unlike birinapant, which can target both cIAP1 and 2,13 Debio 1143 primarily targets cIAP1 but may not be as efficient in degrading cIAP2.37, 38 Our previous work suggests that degradation of both cIAP1 and 2 is necessary for sensitizing platinum-resistant HGSC cells to carboplatin therapy,12 and here we provide evidence that the inability to degrade cIAP2 induces co-therapy resistance (Fig. S4A, B). To translate our preclinical findings, we propose testing the efficacy of birinapant and carboplatin combination therapy (proven safe in Phase I trials39)in patients with HGSCs predicted to benefit from co-therapy based on analysis of their tumor in our in vitro organoid bioassay.

Platinum drugs once revolutionized the world of chemotherapy and are now part of the current standard of care for many tumor types, including HGSC, non-small cell lung,40 colorectal,41 bladder,42 and cervical cancers.43 But the clinical challenge of platinum resistance remains unsolved. The precision medicine approach of overcoming platinum resistance described here may provide a solution to this problem when tested in clinical trials based on the fact that (a) birinapant targets a mechanism of platinum resistance found specifically in the carboplatin-resistant tumor subpopulations and (b) we propose testing the efficacy of this combination therapy in the 50% of patients with tumors predicted to respond to this co-therapy. Extensive preclinical work presented in this manuscript suggests that our proposed therapeutic approach could be efficacious in platinum resistant as well as sensitive disease. Clinical success of such an approach would eliminate the need for arbitrarily classifying tumors as platinum sensitive or resistant. Instead all carcinomas could be treated with a platinum drug that eliminates the platinum-sensitive cell population in combination with a tailored sensitizing agent (such as birinapant) that enables efficient targeting and elimination of the platinum-resistant tumor cells.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Antibodies, primers, and detailed descriptions of methods are in SI Materials and Methods.

Reagents

Birinapant was from ChemieTek and carboplatin from R&D Systems.

Animals

NSG female mice (Jackson Laboratory) were housed according to University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Division of Laboratory Animal Medicine guidelines. Animal experiments were approved by the UCLA Animal Research Committee.

Cell lines

S1-GODL,12 S8-GODL, and S9-GODL cells were established in the G.O. Discovery Laboratory. S8-GODL and S9-GODL cells were classified as platinum resistant given they were each derived from an independent platinum resistant clinical sample. Ovcar-3, A549, H226, H460, CaSki, HeLa, SiHa, 5637, J82, HT1197, DLD1, Colo205, and SW620 cells were from ATCC. All cell lines were used within 10 passages.

Survival assays

Mice were injected IP with 2.5 × 105 HGSC cells. Tumor-bearing mice were randomized into treatment arms (n = 8–10/arm) of vehicle, birinapant (30 mg/kg IP in 12.5% captisol 2×/week), carboplatin (50 mg/kg IP in PBS 1×/week), or co-therapy for 4 weeks. After therapy, mice were observed until they reached NIH-defined end-point criteria.14

Clinical samples

Clinical samples (Table S3) were collected from consented patients in accordance with UCLA Internal Review Board guidelines (IRB 10-000727).

In vitro organoid bioassay

Cell lines or dissociated tumors were plated in an in vitro organoid bioassay as previously described,12 then treated with vehicle, birinapant (300 nM), carboplatin (50 μM), or birinapant and carboplatin (co-therapy). Cell survival was analyzed after 72 h by flow cytometry,12 then treated cells were re-plated in an organoid assay without drug.

Western blot

Western blot was performed as previously described.12 Quantification of cIAP expression was accomplished using ImageJ. To quantitatively compare cIAP expression in multiple specimens, levels of cIAP in 20 μg of tumor cell lysate were normalized using GAPDH (obtained from the same exposure time as matched cIAP sample) and then compared with a 40 ng pan-cIAP standard (defined as 20 ng each of cIAP1 and cIAP2).

Statistical analysis

Survival curves were computed using the Kaplan-Meier methods, and adjusted p-values were computed using the log-rank test. Means were compared using analysis of variance. Non-parametric receiver operator characteristic analysis was used to compute threshold and accuracy statistics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Jeffrey Gornbein DrPH (biostatistician), the UCLA Tissue Procurement Core Laboratory (TPCL), and the UCLA Broad Stem Cell Research Center FACS Core. This work was supported mainly by an American Cancer Society Research Scholar Grant RSG-14-217-01-TBG to S.M. and funds from the Phase One Foundation, the Ovarian Cancer Circle Inspired by Robin Babbini, a STOP cancer Miller Family seed grant and a STOP cancer Margot Lansing Memarial seed grant. S.M. is also funded in part by an NIH/NCI R01CA183877 grant and a CDU/UCLA NIH/NIMHD #U54 MD007598 grant.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

D.M.J. and V.L.: conception and design, development of methodology, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, writing of manuscript; R.F.: acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, writing of manuscript; M.N. and L.B.: acquisition of data; G.L.: analysis and interpretation of data; K.F. and L.H.: development of methodology, acquisition of data; S.M. conception and design, development and methodology, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, writing of manuscript, study supervision, final approval of manuscript.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

References

- 1.Rosenberg B, Vancamp L, Krigas T. Inhibition of cell division in Escherichia coli by electrolysis products from a platinum electrode. Nature. 1965;205:698–699. doi: 10.1038/205698a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galluzzi L, et al. Molecular mechanisms of cisplatin resistance. Oncogene. 2012;31:1869–1883. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dilruba S, Kalayda GV. Platinum-based drugs: past, present and future. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2016;77:1103–1124. doi: 10.1007/s00280-016-2976-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.du Bois A, et al. A randomized clinical trial of cisplatin/paclitaxel versus carboplatin/paclitaxel as first-line treatment of ovarian cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1320–1329. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berek JS, Crum C, Friedlander M. Cancer of the ovary, fallopian tube, and peritoneum. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2012;119:S118–S129. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(12)60025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis A, Tinker AV, Friedlander M. “Platinum resistant” ovarian cancer: what is it, who to treat and how to measure benefit? Gynecol Oncol. 2014;133:624–631. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pujade-Lauraine E, et al. Bevacizumab combined with chemotherapy for platinum-resistant recurrent ovarian cancer: the AURELIA open-label randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1302–1308. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.4489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.ten Bokkel Huinink W, et al. Topotecan versus paclitaxel for the treatment of recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2183–2193. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.6.2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller DS, et al. Phase II evaluation of pemetrexed in the treatment of recurrent or persistent platinum-resistant ovarian or primary peritoneal carcinoma: a study of the gynecologic oncology group. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2686–2691. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.2963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Israel VP, et al. Phase II study of liposomal doxorubicin in advanced gynecologic cancers. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;78:143–147. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.5819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoskins PJ, Swenerton KD. Oral etoposide is active against platinum-resistant epithelial ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:60–63. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janzen DM, et al. An apoptosis-enhancing drug overcomes platinum resistance in a tumour-initiating subpopulation of ovarian cancer. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7956. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 13.Benetatos CA, et al. Birinapant (TL32711), a bivalent SMAC mimetic, targets TRAF2-associated cIAPs, abrogates TNF-induced NF-kappaB activation, and is active in patient-derived xenograft models. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13:867–879. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.NIH Office of Animal Care and Use. Guidelines for endpoints in animal study proposals. 2016 https://oacu.oir.nih.gov/sites/default/files/uploads/arac-guidelines/asp_endpoints.pdf.

- 15.McPherson A, et al. Divergent modes of clonal spread and intraperitoneal mixing in high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Nat Genet. 2016;48:758–767. doi: 10.1038/ng.3573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwarz RF, et al. Spatial and temporal heterogeneity in high-grade serous ovarian cancer: a phylogenetic analysis. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001789. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelland L. The resurgence of platinum-based cancer chemotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:573–584. doi: 10.1038/nrc2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar A, Chinta JP, Ajay AK, Bhat MK, Rao CP. Synthesis, characterization, plasmid cleavage and cytotoxicity of cancer cells by a copper(II) complex of anthracenyl-terpyridine. Dalton Transac. 2011;40:10865–10872. doi: 10.1039/c1dt10201j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Powles T, et al. A comparison of the platinum analogues in bladder cancer cell lines. Urol Int. 2007;79:67–72. doi: 10.1159/000102917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rixe O, et al. Oxaliplatin, tetraplatin, cisplatin, and carboplatin: spectrum of activity in drug-resistant cell lines and in the cell lines of the national cancer institute′s anticancer drug screen panel. Biochem Pharmacol. 1996;52:1855–1865. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)81490-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu J, et al. Early combined treatment with carboplatin and the MMP inhibitor, prinomastat, prolongs survival and reduces systemic metastasis in an aggressive orthotopic lung cancer model. Lung Cancer. 2003;42:335–344. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(03)00355-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen J, Emara N, Solomides C, Parekh H, Simpkins H. Resistance to platinum-based chemotherapy in lung cancer cell lines. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2010;66:1103–1111. doi: 10.1007/s00280-010-1268-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fulda S. Promises and challenges of SMAC mimetics as cancer therapeutics. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:5030–5036. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong RS. Apoptosis in cancer: from pathogenesis to treatment. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2011;30:87. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-30-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Moorsel CJ, et al. Mechanisms of synergism between cisplatin and gemcitabine in ovarian and non-small-cell lung cancer cell lines. Br J Cancer. 1999;80:981–990. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bergman AM, Ruiz van Haperen VW, Veerman G, Kuiper CM, Peters GJ. Synergistic interaction between cisplatin and gemcitabine in vitro. Clin Cancer Res. 1996;2:521–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brewer CA, Blessing JA, Nagourney RA, Morgan M, Hanjani P. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine in platinum-refractory ovarian or primary peritoneal cancer: a phase II study of the gynecologic oncology group. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;103:446–450. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ishida S, McCormick F, Smith-McCune K, Hanahan D. Enhancing tumor-specific uptake of the anticancer drug cisplatin with a copper chelator. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:574–583. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liang ZD, et al. Mechanistic basis for overcoming platinum resistance using copper chelating agents. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11:2483–2494. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fu S, Naing A, Fu C, Kuo MT, Kurzrock R. Overcoming platinum resistance through the use of a copper-loweringagent. Mol CancerTher. 2012;11:1221–1225. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Plumb JA, Strathdee G, Sludden J, Kaye SB, Brown R. Reversal of drug resistance in human tumor xenografts by 2′-deoxy-5-azacytidine-induced demethylation of the hMLH1 gene promoter. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6039–6044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown R, et al. hMLH1 expression and cellular responses of ovarian tumour cells to treatment with cytotoxic anticancer agents. Oncogene. 1997;15:45–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Glasspool RM, et al. A randomised, phase II trial of the DNA-hypomethylating agent 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (decitabine) in combination with carboplatin vs carboplatin alone in patients with recurrent, partially platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:1923–1929. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lindemann K, et al. Poor concordance between CA-125 and RECIST at the time of disease progression in patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer: analysis of the AURELIA trial. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1505–1510. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fulda S, Vucic D. Targeting IAP proteins for therapeutic intervention in cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;11:109–124. doi: 10.1038/nrd3627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Noonan AM, et al. Pharmacodynamic markers and clinical results from the phase 2 study of the SMAC mimetic birinapant in women with relapsed platinum-resistant or -refractory epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer. 2016;122:588–597. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Langdon CG, et al. SMAC mimetic Debio 1143 synergizes with taxanes, topoisomerase inhibitors and bromodomain inhibitors to impede growth of lung adenocarcinoma cells. Oncotarget. 2015;6:37410–37425. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cai Q, et al. A potent and orally active antagonist (SM-406/AT-406) of multiple inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAPs) in clinical development for cancer treatment. J Med Chem. 2011;54:2714–2726. doi: 10.1021/jm101505d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amarvadi P, et al. A phase I study of birinapant (TL32711) combined with multiple chemotherapies evaluating tolerability and clinical activity for solid tumor patients. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2504. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eagan RT, et al. Platinum-based polychemotherapy versus dianhydrogalactitol in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Treat Rep. 1977;61:1339–1345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Andre T, et al. Oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2343–2351. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Massari F, et al. Emerging concepts on drug resistance in bladder cancer: implications for future strategies. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2015;96:81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thigpen T, Shingleton H, Homesley H, Lagasse L, Blessing J. Cis-platinum in treatment of advanced or recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix: a phase II study of the gynecologic oncology group. Cancer. 1981;48:899–903. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810815)48:4<899::aid-cncr2820480406>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.