Abstract

Background

Local drug delivery has transformed medicine, yet it remains unclear how drug efficacy depends on physicochemical properties and delivery kinetics. Most therapies seek to prolong release, yet, recent studies demonstrate sustained clinical benefit following local bolus endovascular delivery.

Objectives

The purpose of the current study was to examine the interplay between drug dose, diffusion and binding in determining tissue penetration and effect.

Methods

We introduce a quantitative framework that balances dose, saturable binding and diffusion and measured the specific binding parameters of drugs to target tissues.

Results

Model reduction techniques augmented by numerical simulations revealed that the impact of saturable binding on drug transport and retention is determined by the magnitude of a binding potential, Bp, the ratio of the binding capacity to the product of the equilibrium dissociation constant and accessible tissue volume fraction. At low Bp (<1) drugs are predominantly free and transport scales linearly with concentration. At high Bp (>40) drug transport exhibits a threshold dependence on applied surface concentration.

Conclusions

In this paradigm, drugs and antibodies with large Bp penetrate faster and deeper into tissues when presented at high concentrations. A threshold dependence of tissue transport on the applied surface concentration of paclitaxel and rapamycin may explain the threshold dose dependence of the in vivo biological efficacy of these drugs.

Keywords: transport, reaction diffusion, Damkohler number, finite element method, antibodies, drug eluting stents

INTRODUCTION

Pharmacologic treatments of solid tumors and vascular pathologies such as intimal hyperplasia must overcome a twofold challenge, one of pharmacology and the other of pharmacokinetics. That is, not only must the drug possess an appropriate pharmacology, but it must also penetrate the tissue at adequate concentrations and reside in the vicinity of its target cells for a sufficient duration. Drug pharmacokinetics depend on the physicochemical properties of the drug but also on the mode of its delivery as this determines the delivered dose, its kinetics and the impact of metabolism. Indeed, local drug delivery has transformed vascular medicine and oncology. The release of paclitaxel and rapamycin from endovascular stents in amounts which would not have effect if administered systemically virtually eliminates intimal hyperplasia and clinical restenosis (Grube et al., 2003, Moses et al., 2003). The local infusion of anti-neoplastic drugs has similarly significant effects (Goldberg et al., 2002). Yet, in both applications efficacy is binary, toxicity is dose related and local delivery is not efficacious for all drugs. There appears to be a threshold that must be exceeded to induce effect, below which no response is observed and after which only toxicity rises (Takimoto et al., 2003). Clinical effect has been postulated to require relative drug insolubility to enable sustained release and enhance tissue retention through hydrophobic interaction (Acharya et al., 2006, Creel et al., 2000, Lovich et al., 2001). Toxicity is presumed to occur as the amount of retained drug mounts and induces non-specific effects on the tissue.

As the evolution of controlled release technology allows for a range of kinetic profiles, concentrations, and drug properties (Acharya et al., 2006, Kamath et al., 2006, Finkelstein et al., 2003, Serruys et al., 2005) the question arises whether sustained release or tissue loading is more critical, and whether these are independent elements. The resurgent use of balloon catheters (Scheller et al., 2004) and intra-arterial injection (Scheller et al., 2003) to deliver large boluses of drugs is an example of the progression of such thought. Early evidence supports a clinical effect for bolus delivery of paclitaxel in treating arterial restenosis (Scheller et al., 2006). We now ask whether the change in concentration that accompanies more rapid delivery modalities simply scales tissue loading and penetration or whether a more complex tissue kinetic is observed.

We show that the equilibrium interaction of locally administered drugs and arterial tissue is concentration dependent and consistent with saturable bimolecular binding. But we also demonstrate that the arterial equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd) that defines molecular interaction cannot alone define tissue-drug interaction. Heparin, paclitaxel and rapamycin all share a similar Kd, and yet they demonstrate significantly different tissue distribution after local delivery (Levin et al., 2004, Creel et al., 2000, Lovich et al., 2001). To examine issues related to the concentration gradients that local delivery can induce and the spectrum of binding properties for different drugs, we created an integrated mathematical construct with consideration of binding site density and drug diffusion within arteries. Previous model systems have introduced elements that described binding for high affinity receptors or low ligand concentrations (Singh et al., 1994, Graff et al., 2003, Sakharov et al., 2002). We now address the cases of low affinity compounds and high local concentrations. By balancing the constitutive affinity properties of a receptor for its ligand with ligand diffusivity and receptor and ligand concentrations, we can begin to consider how tissue loading and penetration scale with dose and delivery kinetics. All of these elements can be included in a single dimensionless parameter, Bp, the ratio of the maximum binding capacity BM to the product of Kd and the fraction of accessible tissue volume. This equilibrium constant (Baxter et al., 1991) is also known as the binding potential (Mintun et al., 1984) and has previously only been used to characterize binding at low concentrations. We show that the magnitude of Bp critically determines the concentration dependence of the dynamics of drug penetration into the tissue and correspondingly, of the spatio-temporal propagation of biologic effects.

The combination of modeling and empiric data provides a mechanistic underpinning for the unusual dose responses seen in local therapies (Takimoto et al., 2003, Gershlick et al., 2004, Serruys et al., 2005) and a rational framework by which to choose drugs, release platforms and release kinetics for specific tissue effects. It may be possible to now formally evaluate emerging therapies like drug release from endovascular balloons, the apparent divergence in dose response for toxicity and efficacy for endovascular stent-eluted rapamycin and paclitaxel, or the impact of lesion complexity and tissue state on drug effect (Rogers et al., 2006). Classic diffusion alone cannot provide this insight nor do empiric models explain these findings. Use of a combined parameter like Bp can indeed explain threshold dependence on the applied dose and delivery kinetics. Optimal dose need no longer be considered as solely determined by pharmacologic considerations, but by the minimal concentration that ensures adequate tissue penetration as well. Such a paradigm can then readily incorporate alterations in tissue with disease and/or concomitant systemic pharmacotherapy wherein binding sites are disrupted or their affinity altered.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

MODELING AND SIMULATIONS

Arterial drug uptake from a well mixed solution of luminal drug is modeled as a one dimensional transport problem with constant concentration boundary and initial conditions

| (1a) |

| (1b) |

| (2) |

Here B and C, are respectively, the local concentrations of bound and free drug in the tissue, Cbulk is the concentration of bulk drug in the uptake medium, ε is the fraction of accessible tissue volume, t, the time after initial exposure to drug, x the distance from the lumen and L the thickness of the artery wall. The local concentration of arterial drug is determined by the balance between saturable binding (Graff et al., 2003, Lovich et al., 1996a)

| (3) |

and diffusion (with diffusion coefficient D) (Graff et al., 2003, Singh et al., 1994, Lovich et al., 1996a)

| (4) |

Here, kf, is the association rate constant, kr, the dissociation rate constant, and BM is the concentration of tissue binding sites. Eqs 1–4 were solved numerically using the chemical engineering module in the finite element package COMSOL with parameter values that correspond to drug transport in arteries (Supplemental Data, L=1000μm). The computational domain was meshed using 240 Lagrange quadratic elements. The resulting system of algebraic equations was integrated using a fifth order backward differencing scheme with variable time stepping and tight tolerances (relative tolerance of 10−10 and absolute tolerance of 10−12). Drug loading per unit area was evaluated as the spatial integral of B+C.

Model reduction

The degree to which diffusion limits ligand-receptor binding can be assessed by defining a Damköhler number Da, as the ratio of the rates of binding and diffusion

| (5) |

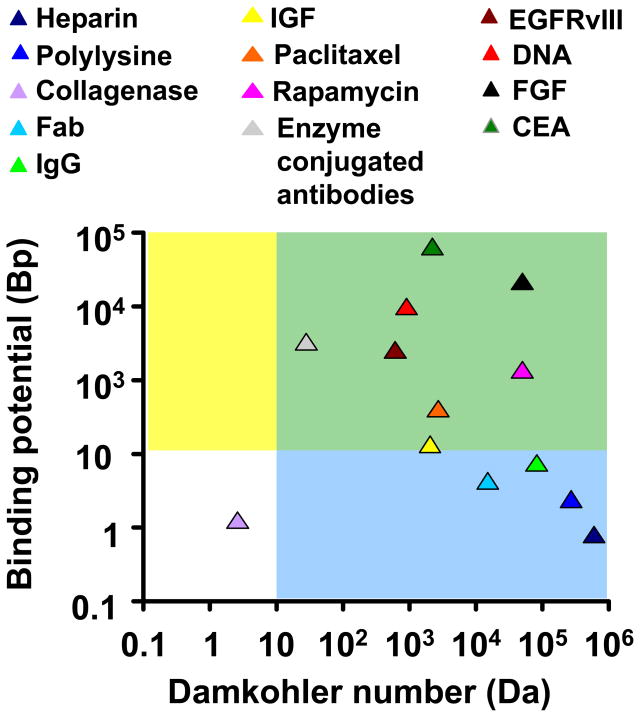

A small Damköhler number implies that diffusion is the faster process such that ligand-receptor binding is the (slow) rate limiting process that determines tissue loading kinetics. Small Damköhler numbers typically arise in highly porous gels (Tzafriri et al., 2002) or when the diffusive path in the tissue is very small. On the contrary, the arterial dynamics of heparin, paclitaxel and rapamycin are all characterized by large Damköhler numbers (Fig 1) implying that binding is diffusion-limited (Lovich et al., 1996a, Singh et al., 1994) and that the concentrations of bound and free drug coexist in a quasi-equilibrium such that

Figure 1.

Classification of drug-tissue pairs (Supplemental Data) according to the magnitudes of the Damkohler number and the binding potential. Our analysis of equilibrium drug retention will focus on large binding potentials (Bp>10, yellow and green regions). Analysis of drug transport will further presume that transport is diffusion limited (Da>10, green regions). These assumptions will be validated for paclitaxel and rapamycin and can be seen to include a range of antibodies and growth factors.

| (6) |

where the equilibrium dissociation constant is determined by the ratio of dissociation and association rate constants, Kd = kr/kf. The total local concentration of drug in the tissue, T, is then a function of the local concentration of free drug

| (7) |

and satisfies a diffusion equation

| (8) |

with a concentration dependent effective diffusion coefficient of the form

| (9) |

Here C(T) is the concentration of free drug in the tissue as determined by Eq. 7

| (10) |

and B signifies the dimensionless ratio of equilibrium binding parameters

| (11) |

While the Damköhler number is large for many ligand transport scenarios (Fig 1), the magnitude of Bp varies significantly with drug and tissue type (Fig 1). In particular, the arterial Bp of paclitaxel and rapamycin is much larger than that of heparin - the impact of such variations is at the focus of the current study.

EXPERIMENTAL

Unlabeled and radiolabeled rapamycin were generously donated by J&J/Cordis, radiolabeled Paclitaxel was obtained from Vitrax and unlabeled Paclitaxel was from LC Laboratories. Fresh calf internal carotid arteries were cleaned of excess fascia, opened longitudinally, cut into segments (40 to 60 mg), and placed in centrifuge tubes with 1.0 mL of drug solution at room temperature. To assay for the binding specificity, the concentration of unlabeled drug was varied over 3-log orders while holding the concentration of radiolabeled drug constant (10nM [3H]paclitaxel or 10μM [14C]rapamycin). Segments were allowed to equilibrate for 60 hours and were then processed for liquid scintillation counting. The drug count of each tissue sample was normalized by tissue mass to determine the concentration of radiolabeled drug in the tissue (T). Tissue partition coefficient (κ) was defined as the tissue concentration of labeled drug (T) at equilibrium normalized by the total bulk concentration at equilibrium (Cbulk)

Net tissue binding capacity (BM) and equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd) were then estimated by varying the bulk concentration of drug and fitting the experimental partition coefficient values to relationship implied by bimolecular binding of small hydrophobic drugs that have access to the entire tissue volume (e.g. Eq. 7 with ε=1)

Curve fitting was performed using GraphPad Prism 3.0. Note that Eq. 7 cannot be used directly for estimating the equilibrium binding parameters in an experimental protocol such as ours that correlates between tissue-associated labeled drug and total bulk drug, rather than labeled bulk drug as is standard.

RESULTS

BOLUS ENDOVASCULAR DRUG DELIVERY CAN SATURATE ARTERIAL BINDING SITES

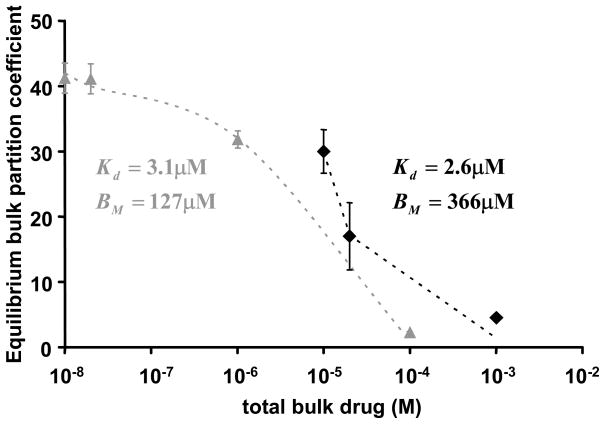

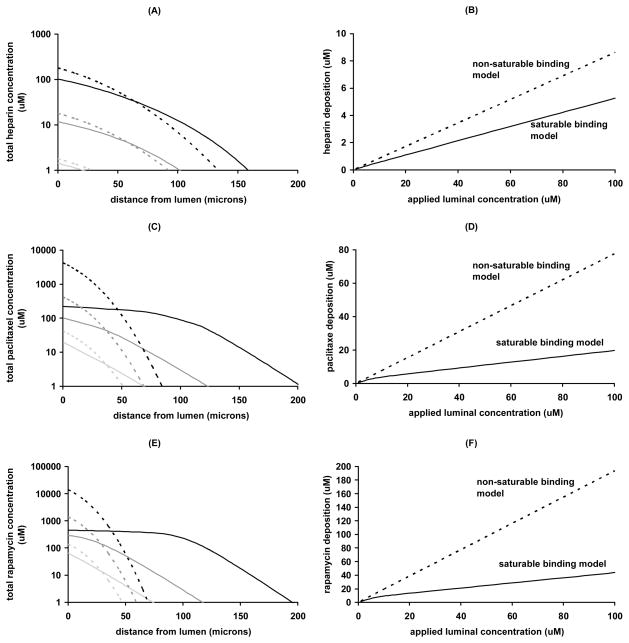

Concerns over the long term complications with drug eluting stents have spurned the development of novel bolus endovascular delivery modalities that deliver large dose over short times (Scheller et al., 2004, Scheller et al., 2003). In particular, clinical studies have shown that short (1 min) endovascular exposures to paclitaxel coated balloon catheters can inhibit in stent restenosis in a range of arterial beds for more than six months (Scheller et al., 2006, Tepe et al., 2008). Though promising, in the absence of a clear mechanistic underpinning these results remain intriguing and are difficult to translate to other drugs. Such delivery is best approximated as a bolus infusion. We previously measured the equilibrium loading of paclitaxel (Creel et al., 2000) in calf carotid arteries and concluded that it was proportional to the equilibrium bulk concentrations. Those experiments employed 100% radiolabeled paclitaxel and were limited to concentrations up to 0.23μM, falling short of the typical concentrations employed in bolus endovascular delivery (Scheller et al., 2003). To circumvent the safety limitations set by the intensity of the radioactive label we now measured the equilibrium arterial loading of paclitaxel and rapamycin using mixtures of labeled and unlabeled drug (Fig 2). The equilibrium partition coefficient of both drugs decreased as the total bulk concentration increased, consistent with saturable binding. Analysis of the equilibrium partitioning curves yielded estimates of the net arterial dissociation constant and binding capacities (Fig 2). Notably, the net dissociation constants of both drugs are in the micromolar range, similar to heparin (Lovich et al., 1996b). By contrast, the net arterial binding capacities for paclitaxel and rapamycin (Fig 2) are more than ten-fold higher than for heparin (Lovich et al., 1996b). When these estimates are used to simulate bolus endovascular delivery, significant differences emerge between heparin and paclitaxel with regard to the impact of binding on the dynamics of drug distribution (Fig 3). Whereas a model of non-saturable binding, that assumes a proportionality between the local concentrations of free and total drug (Hwang et al., 2001), adequately predicts the distribution of heparin (Fig 3A,B), this is not the case for paclitaxel or rapamycin. The full model (Eq. 1–4) which correctly accounts for saturable binding predicts deeper and more uniform penetration of paclitaxel (Fig 3C) and rapamycin (Fig 3E) and therefore lower net arterial loads (Figs 3D,F).

Figure 2.

Experimental validation of saturable binding to arteries. The equilibrium net arterial partition coefficient of paclitaxel (gray triangles) or rapamycin (black diamonds) was measured as described in Methods. Bimolecular binding fit the experimental results (dashes) and provided estimates of the equilibrium binding parameters of paclitaxel (R2=0.997) and rapamycin (R2=0.970).

Figure 3.

Concentration dependence of bolus endovascular delivery. Simulated transmural drug concentrations (A,C,E) and average arterial deposition (B,D,F) at the end of 3min bolus endovascular delivery of heparin (A,B), paclitaxel (C,D) or rapamycin (E,F). Predictions of the saturable binding model (lines) and non-saturable binding model (dashes) were contrasted over three decades of luminal concentration: 1μM (light gray) 10μM (gray) or 100μM (black). Deviations between the two models scale with the applied luminal concentration and are particularly pronounced for paclitaxel and rapamycin. Interestingly, the non-saturable binding model significantly underestimates the depth of paclitaxel (C) and rapamycin (E) penetration into the artery while overestimating their total arterial deposition (D and F).

Typically, differences in drug penetration due to binding interactions have been attributed to differences in binding dissociation constants (Fujimori et al., 1990, Adams et al., 2001). Yet, the net arterial dissociation constants of heparin, paclitaxel and rapamycin are all in the micromolar range (Supplemental Data). Rather, our finding that net arterial binding capacities for paclitaxel and rapamycin are more than ten-fold higher than for heparin (Supplemental Data) suggests that binding capacity may also significantly impact drug distribution. Subsequent analysis corroborates this hypothesis and elucidates the prediction of a marked concentration dependence of arterial paclitaxel distribution upon bolus delivery.

FRACTIONAL DRUG RETENTION

The success of endovascular drug delivery appears to be predicated upon the arterial residence time of the drug (Riessen et al., 1994). Since free drug diffuses and washes away upon removal of the drug source, we first asked what determines the fraction of tissue-bound drug?

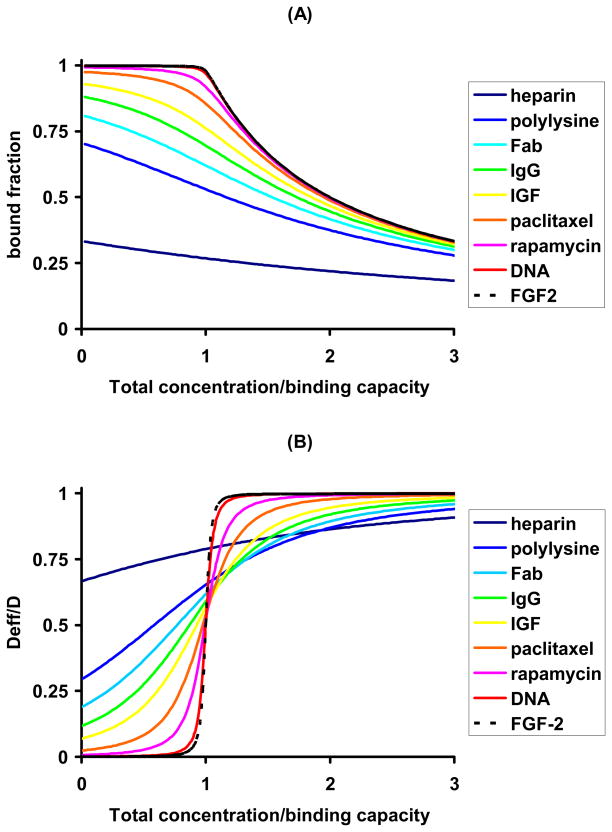

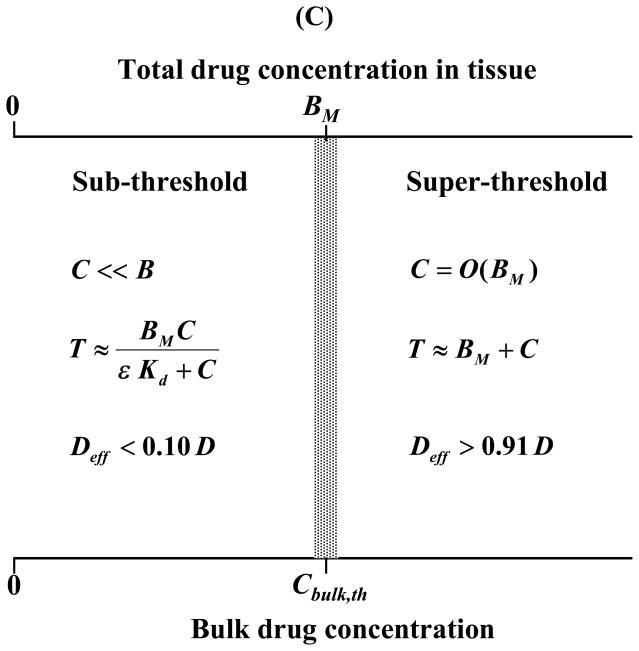

To examine this we plotted the fraction of bound drug (B/T) for a range of drugs and tissues (Fig 1) as a function of the total concentration of drug in the tissue (T). Evaluating the fraction of bound drug as 1−C/T, with C provided by Eq 10, and scaling the total concentration of drug to the maximal potential concentration of retained drug, BM, we found that the magnitude of Bp dictates a hierarchy of fractional drug retention curves (Fig 4A). Drugs with low Bp such as heparin are predominantly free regardless of the applied concentration and its duration. At larger Bp drug is predominantly bound at states of excess binding sites and the fraction of bound drug decreases appreciably only as the total concentration exceeds the binding capacity. The degree of drug retention and the sharpness of the transition between states of excess binding site and excess drug both scale with Bp. A detailed analysis of Eq. 10 (Appendix A) illustrates that an appreciable pool of free drug exists in the tissue only above the threshold bulk concentration

Figure 4.

Drug retention and mobility are determined by the magnitude of Bp. The fraction of bound drug (A) and the effective mobility (B) are plotted as a function of the total local drug content relative to the number of binding sites for a range of drugs and tissues (Supplemental Data). Drugs are color coded according to their Bp with cold colors (e.g. blue) designating small Bp values. Scaling analysis of the equilibrium concentration of free drug and the effective diffusivity (Appendix A) provides an estimate of the threshold bulk concentration for binding saturation and drug diffusion (C).

| (12) |

Such a well defined threshold exists only at large Bp (Fig 4A), such that Cbulk,th is at once much larger than the binding dissociation Kd and much smaller than the binding capacity BM.

EFFECTIVE DRUG DIFFUSIVITY

As only free drug is mobile the magnitude of Bp also dictates a hierarchy of effective diffusivity curves (Fig 4B). At one extreme are molecules like FGF-2 and antibody fragments with huge binding potentials (>1000, Supplemental Data) whose mobility at the excess-ligand regime (C>BM) is three orders of magnitude larger than their mobility in the unsaturated binding regime (C<Kd). At the other extreme, of weakly retained drugs (Bp<1) we find heparin (Bp=0.8, Supplemental Data) whose effective arterial diffusivity increases by no more than 30% with total concentration. Paclitaxel and rapamycin, and certain growth factors and antibodies, display an intermediate concentration dependence that becomes more pronounced with increasing Bp (Fig 4B). Rigorous analysis of these trends (Appendix A) reveals that diffusivity is essentially unhindered (Deff>0.9D) at supersaturating concentrations, drops by 50% at parity between total drug concentration and binding capacity, and is less than 10% of the free diffusivity and strongly concentration dependent at subsaturating concentrations(Fig 4C). These predictions are borne out by paclitaxel (Bp =40.7), but not by compounds with lower Bp such as heparin (Fig 4B).

The results of the last two sections illustrate the profound effects of Bp on drug retention and transport and begin to explain the differential retention and distribution of heparin, paclitaxel and rapamycin. Based on their Bp paclitaxel and rapamycin are classified as strongly retained drugs with markedly concentration dependent arterial transport. In contrast, heparin is classified as a weakly retained drug whose arterial transport is insensitive to applied luminal concentration.

ARTERIAL PENETRATION OF STRONGLY RETAINED DRUGS

To further elucidate the concentration dependence of endovascular drug delivery we analyzed the effective diffusion equation (Eq. 8) subject to uniform initial conditions

| (13) |

and applied luminal concentration

| (14) |

At short times, before an appreciable amount of drug reaches the far surface of the tissue it is valid to approximate the artery as a semi-infinite medium (Crank, 1975) for which it is possible to derive insightful analytical solutions in the limit of large Bp.

Sub-threshold bulk concentrations (receptor excess)

At total surface concentrations below the binding capacity the effective diffusion coefficient is nonlinear and approximated by (Appendix A).

The kinetics of tissue loading per unit area are then (Appendix B)

| (15) |

where the parameter β is evaluated numerically as the root of the following equation

| (16) |

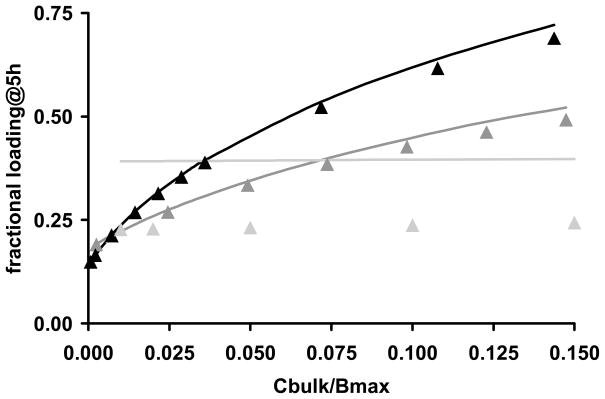

Numerical simulations (Fig 5) illustrate that Eq. 15 closely approximates the arterial loading kinetics of paclitaxel (Bp=40.7, Cbulk,th=0.16BM) and rapamycin (Bp=139, Cbulk,th=0.08BM) but underestimates the uptake of heparin (Bp=0.8, Cbulk,th=1.4BM). At 5h super-threshold bulk concentrations of paclitaxel and rapamycin fully penetrate the artery, and the sub-threshold approximation (Eq. 15) underestimates drug loading.

Figure 5.

Tissue loading in the unsaturated binding regime. Tissue associated rapamycin (black), paclitaxel (dark gray) or heparin (light gray) at 5h is normalized to the equilibrium drug content and plotted versus the normalized concentration of bulk drug. Numerical results (lines) are contrasted with the sub-threshold approximation (Eqs. 15, solid triangles).

The dependence of tissue loading on bulk concentration can be rendered explicit in the boundary cases of the sub-threshold regime. Low bulk concentrations compared to the equilibrium dissociation constant (Cbulk <Kd/3) provide for (Appendix B)

| (17) |

The latter result is the specialization of the celebrated non-saturable binding result(Crank, 1975) in the limit of strong retention (Bp ≫ 1)

| (18) |

The non-saturable binding result provides an excellent approximation for heparin in the concentration range Cbulk ≤0.15BM, but not for strongly retained drugs such as paclitaxel and rapamycin wherein the condition Kd≪BM restricts the validity of the non-saturable regime to very low apparent concentrations (not shown).

Near threshold bulk concentrations (Eq. 12), provide for (Appendix B)

| (19) |

The latter result consistently overestimates the numerical predictions for paclitaxel and rapamycin at low bulk concentrations but becomes quantitative as the bulk concentration approaches Cbulk,th (not shown).

Super-threshold bulk concentrations (drug excess)

The effective diffusion coefficient of strongly retained drugs approaches the free diffusivity D at saturating concentrations and drops to negligible values for non-saturating concentrations (Figs 4B,C). This can be idealized as a step discontinuity

| (20) |

Correspondingly, the luminal boundary condition (Eq. 14) simplifies to

| (21) |

The limit of a discontinuous diffusion coefficient (Eq. 20) can be solved analytically for short times, prior to full penetration of the matrix as (Crank, 1975)

| (22) |

where

| (23) |

is the location of the discontinuity front and k is the root of the transcendental equation

| (24) |

The cumulative amount of drug in the tissue (per unit area) is then

| (25) |

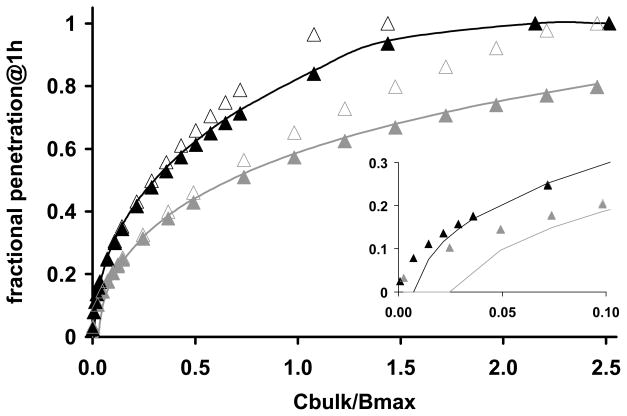

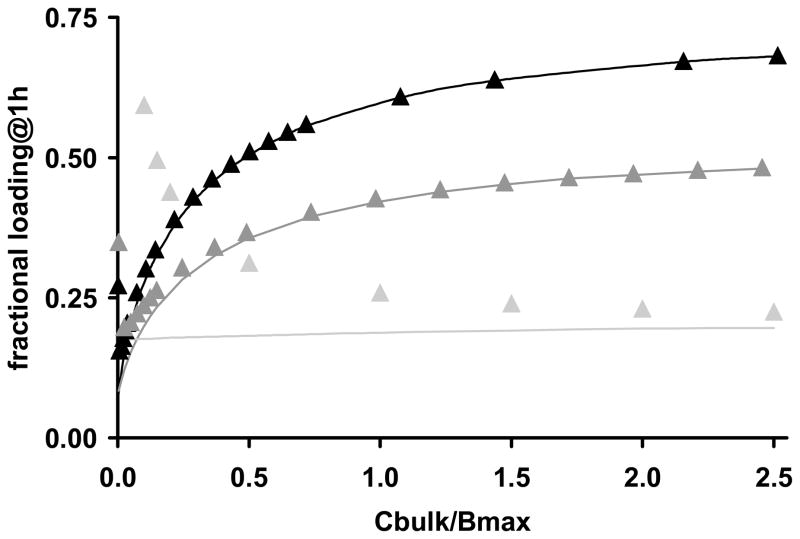

Numerical simulations (Fig 6) illustrate that Eqs. 23–24 accurately predict the location of the binding saturation front for paclitaxel (Bp=40.7) and rapamycin (Bp=139.2) at super threshold bulk concentrations, but over-predict penetration at lower bulk concentrations. Correspondingly, Eq. 25 accurately predicts the loading kinetics of paclitaxel and rapamycin at super threshold bulk concentrations, but over-predicts tissue loading at sub-threshold concentrations (Fig 7). These trends become even more apparent for heparin, as its threshold concentration Cbulk,th falls in the middle of the concentration range examined in Fig 7 (Cbulk,th=1.4BM). The adequate approximation of super-threshold heparin loading by Eq. 25 reflects the latter’s correct asymptotic convergence to the loading kinetics of freely diffusible drugs(Crank, 1975) , Cbulk ≫ Cbulk, th.

Figure 6.

Concentration dependence of drug penetration and effect. The depth at which arterial binding sites become half saturated at the end of 1h of incubation in paclitaxel (dark gray) or rapamycin (black) is plotted versus normalized bulk concentration. Numerical solutions (lines) are contrasted with S/L (solid triangles, Eqs. 23–24) or (empty triangles, Eqs. 23 and 26). Eqs. 23–24 predict the location of the binding penetration front in all but sub-saturating bulk concentrations (insert).

Figure 7.

Tissue loading in the saturable binding regime. The predicted concentration dependence of drug uptake from bulk solutions of rapamycin (black), paclitaxel (dark gray) or heparin (light gray). Tissue associated drug at 1h is normalized to the corresponding equilibrium uptake and plotted versus the normalized concentration of bulk drug. Numerically simulated loadings (lines) are contrasted with the super-threshold approximations (Eq. 25, solid triangles).

At near threshold bulk concentrations, ,

| (26) |

and Eq. 19 is recovered (Paul et al., 1976), implying a seamless overlap of the sub- and super-threshold approximations. Together, the sub- and super- threshold approximations describe the loading kinetics of strongly retained drugs at any bulk concentration. Numerical examples illustrate that Eq. 26 accurately predicts the location of the binding saturation front for intermediate bulk concentrations, Cbulk, th< Cbulk < 0.5BM, but increasingly over-estimates penetration as the bulk concentrations increases (Fig 6). Similarly, Eq. 19 accurately predicts mass uptake for intermediate bulk concentrations, Cbulk, th< Cbulk < 0.5BM, but under-estimates drug loading at super-threshold bulk concentrations (not shown).

DISCUSSION

As binding affinity is synonymous with binding strength, it is widely held that affinity also provides a measure of the impact of binding on a compound’s transport and equilibrium properties. However, differences in binding affinity cannot alone explain the significant differences in the vascular retention and transport of e.g. heparin compared to paclitaxel and rapamycin. Similarly, IgG and the EGFRvIII specific single chain antibody fragment bind to solid tumors with similar binding affinities (Supplemental Data), yet the transport of the former is only slightly affected by such binding (Baxter et al., 1991), whereas the latter is dominated by it (Kuan et al., 2000, Graff et al., 2003). In estimating the impact of binding on drug transport and retention, molecular affinity must be scaled with the binding capacity. Such scaling is inherent to Bp, which is the product of the binding capacity and the apparent affinity constant (Eq. 11). The larger Bp, the sharper the transition between states of receptor excess and ligand excess (Fig 4A). Correspondingly, strongly retained drugs are characterized by large Bp (>10) and effective diffusion coefficients that exhibit a switch-like dependence on total drug concentration (Fig 4B).

In the extreme of large Bp (>40) the concentration dependence of the effective diffusivity facilitates the derivation of approximate analytical solutions that provide a complete description of the uptake of strongly retained drugs across the range of possible bulk concentrations (Figs 4–6). This is noteworthy, as Bp >40 for paclitaxel and rapamycin and a range of important cytokines and antibodies (Fig 1 and Supplemental Data). Above and beyond these detailed quantitative predictions, our analysis elucidates the dependence of ligand transport on the constitutive binding properties of the tissue for the ligand, and the degree to which ligand concentration can modulate the shape of ligand gradients in the tissue (Fig 3). In particular, our analysis predicts that the saturation of specific binding sites by strongly retained compounds can be accelerated significantly by ramping up the bulk concentration well beyond Kd, but that this effect plateaus above the threshold concentration for drug mobility . Drug distribution and effect can then be modulated by altering the applied drug load or conversely by manipulating the threshold concentration. For example, the threshold concentration would be lower for drug analogs with larger binding affinities (1/Kd) as these saturate tissue binding sites more readily. Alternatively, the threshold concentration at which drug mobility is significantly impeded by binding should rise for drugs that access a larger tissue volume fraction (e.g. larger ε). This is particularly relevant for hydrophilic antibodies as these are restricted to interstitial space and progressively access smaller volume fractions as their molecular weight increases (Krol et al., 1999, Yuan et al., 2001).

Optimization of binding specificity

Directing therapy to potentially overexpressed receptors is a popular means of selective molecular targeting to specific cells and tissues (Wickham, 2003). Affinity maturation, wherein Kd is minimized, maximizes target selectivity. Previous analyses only described diffusion and binding for high affinity receptors or low ligand concentrations (Singh et al., 1994, Graff et al., 2003, Sakharov et al., 2002) and thus it remains unclear how minimization of the dissociation constant affects molecular penetration into the tissues (Kuan et al., 2000, Adams et al., 2001, Graff et al., 2003). By elucidating the dependence of the penetration depth on the magnitudes of the Bp across the gamut of bulk drug concentration (Fig 6) our analysis clarifies this issue. In the binding regime where Kd ≫ Cbulk drug transport is governed by a constant effective diffusion coefficient D/(1+BP) (Eq. 23). Thus, drug profiles decay over a typical diffusion length scale that varies inversely with the . Bp is inversely related to Kd and as the latter is reduced, not only is target selectivity increased, but penetration depth also drops proportionately. Behavior in the saturated binding regime (Cbulk ≫ Kd) is more intricate and less dependent upon Kd. In this domain drug penetration is less sensitive to variations in the magnitude of the equilibrium dissociation constant (Fig 6), and only dependent on the binding capacity for drugs with large Bp.

Thus, drug penetration drops with the dissociation constant (Fig 6 insert) only for low bulk drug concentrations and not for high. However concentration levels are relative. The bulk concentration at which the effective diffusion coefficient is equal to half its maxima, Cbulk,th is itself a function of the equilibrium dissociation constant and decreases as the latter is minimized (Eq. 12). These findings provide notes of caution and opportunity. As there is a finite resolution to the detection of radio and fluorescently labeled drugs, these compounds are often used at the highest concentration levels. Drug penetration under these conditions is least sensitive to dissociation and apparent results may be biased to overestimate penetration and underestimate the change in penetration with time and modulation of the physicochemical properties like the dissociation constant. The opportunity arises in the manipulation of drug binding in molecular analogues. Minor modifications of the chemical structure of sirolimus, for example, create analogues with retained biological activity but markedly altered interaction with mTOR and FK506 binding protein (Bartorelli et al., 2003, Garcia-Touchard et al., 2006). It may be possible to affect the penetration and binding of analogues of the parent compound in a directed and predicted fashion.

Local delivery can optimize the efficacy of strongly retained drugs

Our prediction that the penetration of strongly retained drugs is markedly dependent on the prescribed surface concentration implies that biological effect may become dominated by drug gradients in the target tissue. In particular, the threshold concentration dependence of the effective diffusivities of paclitaxel and rapamycin (Fig 4B) and the resulting concentration dependence of binding site occupancy inside the tissue (Fig 6) may explain the threshold dose response of paclitaxel in local endovascular delivery (Serruys et al., 2005, Gershlick et al., 2004) and with systemic chemotherapy of solid tumors (Takimoto et al., 2003). Though the latter may be more problematic than the former. The advantages of dose dependent penetration may be largely counterbalanced by dose dependent toxicity, especially with the lack of targeting specificity in systemic delivery. It may be that the full benefits of dose dependent penetration can only be achieved with targeted local drug delivery. Indeed, a marked concentration dependence of paclitaxel penetration into arteries (Fig 3C) may explain the successful inhibition of restenosis up to 12 days after short exposures (3min) of injured arteries to extremely high doses of paclitaxel (Scheller et al., 2003) (100–220μM) that significantly exceed its predicted threshold concentration (Cbulk,th =20μM). The even higher Bp of rapamycin and larger threshold concentration (Cbulk,th =31μM) make it a good candidate for this mode of bolus delivery (Fig 3E).

In contradistinction to balloon catheters that deliver high drug loads over short durations, stents provide a platform for local delivery long after initial intervention and implantation. First generation drug eluting stents were designed to deliver their loads in a sustained fashion, with the aim of prolonging drug residence time and providing drug throughout the various stages of the restenotic response (Drachman et al., 2000). Yet the clinical efficacy of drug eluting stents is not solely predicated on elution rates from the stent (Tanabe et al., 2004) and bolus delivery of paclitaxel from coated balloons also provides sustained inhibition of restenosis (Scheller et al., 2006, Tepe et al., 2008). Thus, the question arises as to whether other elements such as tissue absorption and retention could contribute to prolonging exposure regardless of release? Our results shed light on these issues as they demonstrate that the rate of absorption and the ultimate retention of drugs such as paclitaxel and rapamycin can exhibit a threshold dependence on the delivered dose. Our analysis is of particular significance to second generation drug eluting stents can deliver higher drug doses with minimal washout to attain significant tissue distributions (Bartorelli et al., 2003). Such devices typically deliver drugs by a diffusion controlled mechanism wherein the cumulative drug release can be parameterized as M = Mrel (t/trel)1/2 (Acharya et al., 2006, Kamath et al., 2006, Serruys et al., 2005). Our analysis predicts that the arterial penetration kinetics of strongly retained drugs (Bp>40) following diffusion controlled release will exhibit a threshold dependence on the dose intensity parameter (Appendix B). Penetration increases dramatically as the dose intensity is increased up to a threshold that is set by the arterial transport parameters of the drug

Thus, in the absence of significant washout effects, there exists a balance between the absorbed dose and the duration of elution. Drug accumulation is determined by the tissue binding capacity, the binding potential and drug diffusivity, and until a threshold is reached increasing the eluted dose leads to increasing drug absorption, penetration and occupancy of tissue binding sites. When this threshold is exceeded, for example with large bolus delivery the enhancement of penetration and occupancy is lost. Luminal washout further complicates the analysis as it introduces a distinction between the eluted and delivered doses. In the absence of arterial binding, fractional drug absorption following elution is solely determined by a balance between the rates of elution and arterial diffusion (Balakrishnan et al., 2007). Our results now imply that arterial binding should also be factored into this balance and that the fraction of absorbed dose can exhibit a threshold dependence on the eluted dose. Thus, stent elution of subthreshold doses of paclitaxel or rapamycin will result in the absorption of a significant fraction of the eluted drug as tissue absorbed drug is predominantly bound and therefore retained. Increasing the eluted dose above the absorption threshold will only result in a transient enhancement of the arterial load, as such enhancement establishes a pool of free drug near the lumen that quickly washes away. Our estimates (Supplemental Data) imply that the dose intensity thresholds of paclitaxel and rapamycin are both on the order of 3μg/cm2/h1/2. It is therefore noteworthy that the dose intensity provided by the Taxus stent can reach as much as 20.3μg/cm2/h1/2 (Kamath et al., 2006), significantly exceeding the threshold absorption dose intensity of this drug and implying significant washout..

Generalizations and limitations

Our mathematical model of arterial drug distribution makes certain simplifying assumptions that are not generally true. Although perivascular permeability is low (Hwang et al., 2001), our assumption that the far end is impermeable (Eq. 1b) is not generally valid. Nevertheless, the steepness of the spatial drug gradients prior to tissue breakthrough (Crank, 1975, Dowd et al., 1999) ensures that during this phase drug transport is insensitive to perivascular boundary conditions. At longer times, drug clearance at the far end may invalidate our quantitative predictions.

Our model of drug binding to fixed saturable sites is adequate for modeling the arterial distribution of small hydrophobic drugs such as paclitaxel and rapamycin, but does not account for two processes which arise in antibody and cytokine transport in tissues, receptor endocytosis and binding to (low affinity) non-saturable sites in the tissue. When the assumption of purely saturable binding is relaxed, the effects of nonspecific binding can be read from our results by simply redefining the binding capacity and total concentration as BM → BM/(1 + ε−1Kns) and TM → T/(1 + ε−1Kns) where 1 + Kns is the partition coefficient of non-specific binding (see Appendix C). Whereas paclitaxel and rapamycin both bind to intracellular pharmacologic targets, many antibodies and cytokines bind to specific receptors on the cell surface and are endocytosed as these receptors internalize by nonspecific or ligand induced mechanisms. While beyond the scope of the current work, the same methodology of model reduction and analytical approximations can elucidate the transport of strongly retained drugs that undergo endocytosis. A detailed analysis is forthcoming, but it is already clear that nonspecific endocytosis (with rate constant kt) results in the addition of a sink term in the effective diffusion equation (Eq. 7). The definition of the effective diffusion coefficient (Eq. 9) remains essentially the same in the face of endocytosis, with the simple proviso that the equilibrium dissociation constant is replaced by an apparent dissociation constant that depends on the endocytosis rate constant as Kd,app=(kr+kt)/kf (Tzafriri et al., 2007). Thus, our analysis of the concentration dependence of the effective diffusion coefficient remains valid for endocytosing compounds, as does our prediction that retention scales as the ratio of the binding capacity to the apparent dissociation constant Kd,app=(kr+kt)/kf (Tzafriri et al., 2007), and that local delivery of strongly retained compounds (BM≫Kd,app) should significantly enhance their penetration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Mark Lovich and Prof. Luismar Porto for their critical review of the manuscript. This work was supported in part by the Hertz Foundation, grants from the NIH (R01 GM 49039) and a generous gift of [14C] Rapamycin and funds for materials provided by Johnson and Johnson/Cordis.

APPENDIX A: EQUILIBRIUM DRUG RETENTION

Drug retention is an equilibrium property of a drug-tissue pair and is directly related to the fraction of free equilibrium drug. The stronger the retention the smaller the pool of equilibrium free drug. To analyze the potential binding scenarios it is informative to rewrite the equilibrium free concentration (Eq. 10) as

| (A1) |

where we defined the auxiliary variable

| (A2) |

Eq. A2 diverges for saturating drug concentrations such that T = BM + Kd, reducing Eq. 10 to . In fact, it can be shown that this result remains valid near the singularity in r

| (A3) |

On the contrary, when r is small, the fraction of free drug is determined by the ratio of the drug load to the sum of the equilibrium binding parameters

| (A4) |

| (A5) |

The error associated with results A4–A5 is less than 10% for r<0.40.

STRONGLY RETAINED DRUGS

Results A4–A5 are both invalid for drug concentrations that are sufficiently close to the singularity of r(T), in which case Eq. A3 should be used. Noting that

we can estimate the half width of the singularity zone relative to the binding capacity as

| (A6) |

Thus, the larger the binding potential BP is the sharper the transition between the non-saturated and supersaturated binding regimes. At non-saturating drug concentrations T< (1−δ)BM the drug is predominantly bound (Eq. A4)

| (A7) |

| (A8) |

In contrast, at super-saturating total drug concentrations, T > (1 + δ)BM, a significant fraction of the drug is free (Eq. A5)

| (A9) |

| (A10) |

At the threshold region itself, (1−δ)BM < T< (1 + δ)BM, the concentration of free drug is only a function of the equilibrium binding parameters (Eq. A3) and

| (A11) |

Noting the proportionality of equilibrium concentrations of free drug in the tissue and the bulk medium (Eq. 1a) we infer the existence of a threshold bulk concentration

| (A12) |

When the bulk concentration is below this threshold value drug is predominantly bound (retained). At bulk concentrations above this threshold, a significant fraction of drug is free, representing a significant potential for drug washout in vivo. Importantly, the threshold bulk concentration for drug washout is large compared to the binding dissociation constant.

EFFECTIVE DRUG DIFFUSIVITY

The dependence of the effective diffusivity upon Bp can be rigorously quantified by substituting the appropriate approximations for the free fraction into the definition of the effective diffusivity (Eq. 9). At parity between total drug concentration and binding capacity (Eq. A12) the effective diffusivity is equal to half its maximal value

| (A13a) |

At lower tissue concentrations (Eq. A7) drug mobility is less than 10% of the free mobility and strongly concentration dependent

| (A13b) |

At supersaturating tissue concentrations (Eq. A9) diffusivity is almost unimpeded by binding

| (A13c) |

Taken together, the analysis in this appendix implies that drug transport and retention are strongly concentration dependent and inversely correlated. Drug transport is most significantly retarded at low concentrations such that retention is maximal, and increases dramatically above a well defined threshold concentration. Substituting Eqs. A13b and A13c into the effective diffusion equation we were able to derive analytical approximations for the early loading kinetics of strongly retained drugs across the gamut of bulk drug concentrations, below and above the threshold.

APPENDIX B: TRANSPORT OF STRONGLY RETAINED DRUGS

I. Prescribed sub-threshold surface concentrations

Spatial Distribution

Fujita (Fujita, 1952) modeled solvent transport into a polymer matrix as a diffusion process with a concentration dependent diffusion coefficient of the form

| (B1) |

Here T is the concentration of the solute in the polymer, T0 is the bulk solute concentration in the uptake medium, D(0) is the asymptotic value of solute diffusivity in the limit of low concentrations and α is an empiric parameter that scales the concentration dependence of D (0<α<1). Fujita’s similarity solution for solute uptake into a semi-infinite polymer slab can be cast as (Fujita, 1952)

| (B2) |

where β and θ are determined by transcendental equations and can be evaluated sequentially. First β is evaluated from

| (B3) |

Subsequently, θ is evaluated by solving the transcendental equation

| (B4) |

Thus, whereas a one to one correspondence exists between α and β, each α value is associated with a family of θ(x/t1/2). Fujita used his similarity solution to simulate spatio-temporal solvent profiles in the semi-infinite medium and also to show that the classical diffusion solution is recovered on the limit that α → 0. Adaptation of Fujita’s results to the problem of effective diffusivity at sub-threshold bulk concentrations is achieved by setting

| (B5) |

Mass uptake

Since θ is an implicit function of the spatial coordinate it is not possible to evaluate mass uptake kinetics directly from the concentration profile (Eq. B2). This limitation can be overcome by using the flux balance relationship at the bath/tissue interface

| (B6) |

As Fujita’s solution is a function of the similarity variable

it is informative to use the chain rule to rewrite the right hand side of Eq. B6 as

| (B7) |

Using Fujita’s results (Fujita, 1952) we evaluated ∂T/∂α|α=0 without recourse to Eq. B2 as

| (B8) |

| (B9) |

and

| (B10) |

Equation 15 in the main text is then obtained by invoking the correspondence α = T0/BM (Eq. B5).

The dependence of mass uptake on bulk concentration can be rendered explicit in the boundary cases of the sub-threshold regime. Low bulk concentrations compared to the equilibrium dissociation constant (Cbulk <Kd/3) provide for (Fujita, 1952)

| (B11) |

and

| (B12) |

As the bulk concentration increases beyond the linear binding regime and approaches the threshold concentration (Eq. A12)

| (B13) |

and

| (B14) |

II. Prescribed surface flux

Problem statement

Our detailed analysis of drug transport under prescribed surface concentrations is very informative, and allowed us to consider idealized in vitro and in vivo scenarios wherein the bulk or luminal concentration is prescribed over some time interval. Here we illustrate the relevance of these detailed results for the case wherein the prescribed quantity is the surface flux, rather than the surface concentration. For concreteness we focus our discussion to diffusion controlled process wherein the applied flux is of the form

| (B15) |

These idealized fluxes model relevant local delivery modalities and are amenable to analytical study.

Correspondence

Our analysis of diffusion controlled uptake under prescribed surface concentration illustrated that mass uptake per unit area increases as the square root of time

| (B16) |

The effects of specific binding were manifest as a concentration dependence of the prefactor Q. Using the results and nomenclature of the main text (Eqs. 15, 19 and 25)

| (B17) |

For one sided uptake from a bulk solution at x=0, the following mass balance relationship holds between bulk tissue uptake per unit area (Eq. B16) and the surface flux

| (B18) |

The latter result provides a direct and unique correspondence between the kinetics of mass uptake and distribution under prescribed surface concentration and prescribed surface flux (Carslaw et al., 1959). Given a prescribed surface concentration Cbulk, an equivalent surface flux F (t) = Q/t1/2 can be identified using Eq. B17. This correspondence is unique and invertible as Eq. B17 implies a monotonic relationship between Q and Cbulk.

APPENDIX C: INCLUSION OF NONSPECIFIC BINDING

To include the effects of nonspecific binding we introduce a rate law for nonsaturable binding

| (C1) |

Eqs. 1–3 remain unaltered but Eq. 4 now includes a non-specific binding sink term

| (C2) |

and the total concentration of drug generalizes to

| (C3) |

Equilibrium binding fraction

Mass balance at equilibrium now implies that

| (C4) |

Dividing (C4) through by the nonspecific partition coefficient, 1+ Kns, and solving for the concentration of free drug in the tissue we find

| (C5) |

where we introduced the simplifying notations

| (C6a) |

| (C6b) |

Thus, the sole effect of nonspecific binding is a renormalization of the specific binding capacity and the total drug concentration as in C6a,b. When Kns >1 a significant fraction of drug is bound nonspecifically, reducing the fraction of specifically bound drug. The relative importance of specific binding is then determined by the renormalized binding potential βM/(εKd) = BP/(1 + ε−1 Kns), which may be significantly smaller than BP. For systems such that βM/(εKd) ≫ 1 the fraction of free drug changes rapidly for total drug concentrations in the vicinity of BM (T/BM = Θ/βM ≈1). The normalized width of the region of rapid transition scales as (compare to Eq. A6)

| (C7) |

If the bulk drug concentration is not very high, T < (1−δns)BM, then a negligible fraction of the drug inside the tissue is free

| (C8) |

and most of it is specifically bound

| (C9) |

Otherwise, if the bulk drug concentration is higher than the binding capacity, Tns > (1 + δ)BM, then the concentration of free drug is in great excess of the specific dissociation constant

| (C10) |

such that all the specific binding sites are occupied

| (C11) |

In fact, the specific binding sites are already saturated at intermediate drug loads (1 − δns) BM < T< (1+δns) BM as such loads imply that

| (C12) |

Kinetic implications at high Damköhler numbers

When the pools of free, nonspecifically bound and specifically bound drug are all in a state of dynamic equilibrium, the total concentration of drug can be related to the free concentration of drug as in Eq C4. We can then define an effective diffusion coefficient as

| (C13) |

At subthreshold bulk concentrations and

| (C14) |

At suprathreshold concentrations

| (C15) |

Once again, these results are analogous to the case of purely saturable binding and can therefore be readily appreciated. When Kns ≪ 1 only a small fraction of the drug is bound nonspecifically and the model analyzed in the main text provides a good approximation. When Kns >1, a significant fraction of drug may be bound nonspecifically. The relative importance of saturable binding versus nonspecific binding is then determined by the renormalized binding potential βM/(εKd) = BP/(1 + ε−1Kns). In particular, large BP/(1 + ε−1 Kns) values imply that binding is predominantly saturable and the effects of nonspecific binding are quantitative, rather than qualitative, and correspond to a rescaling of the effective diffusivity as in Eqs. (C13)–(C15).

References

- Acharya G, Park K. Mechanisms of controlled drug release from drug-eluting stents. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2006;58:387–401. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams GP, Schier R, McCall AM, Simmons HH, Horak EM, Alpaugh RK, Marks JD, Weiner LM. High affinity restricts the localization and tumor penetration of single-chain fv antibody molecules. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4750–4755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan B, Dooley JF, Kopia G, Edelman ER. Intravascular drug release kinetics dictate arterial drug deposition, retention, and distribution. J Control Release. 2007;123:100–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartorelli AL, Trabattoni D, Fabbiocchi F, Montorsi P, de Martini S, Calligaris G, Teruzzi G, Galli S, Ravagnani P. Synergy of passive coating and targeted drug delivery: the tacrolimus-eluting Janus CarboStent. J Interv Cardiol. 2003;16:499–505. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8183.2003.01050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter LT, Jain RK. Transport of fluid and macromolecules in tumors. III. Role of binding and metabolism. Microvasc Res. 1991;41:5–23. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(91)90003-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carslaw HS, Jaeger JC. Conduction of heat in solids. Clarendon Press; Oxford: 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Crank J. The Mathematics of Diffusion. Oxford: University Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Creel CJ, Lovich MA, Edelman ER. Arterial paclitaxel distribution and deposition. Circ Res. 2000;86:879–884. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.8.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowd CJ, Cooney CL, Nugent MA. Heparan sulfate mediates bFGF transport through basement membrane by diffusion with rapid reversible binding. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:5236–5244. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.8.5236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drachman DE, Edelman ER, Seifert P, Groothuis AR, Bornstein DA, Kamath KR, Palasis M, Yang D, Nott SH, Rogers C. Neointimal thickening after stent delivery of paclitaxel: change in composition and arrest of growth over six months. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:2325–2332. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)01020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein A, McClean D, Kar S, Takizawa K, Varghese K, Baek N, Park K, Fishbein MC, Makkar R, Litvack F, Eigler NL. Local drug delivery via a coronary stent with programmable release pharmacokinetics. Circulation. 2003;107:777–784. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000050367.65079.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimori K, Covell DG, Fletcher JE, Weinstein JN. A modeling analysis of monoclonal antibody percolation through tumors: a binding-site barrier. J Nucl Med. 1990;31:1191–1198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita H. The exact pattern of concentration-dependent diffusion in semi-infinite medium, part II. Textile Research Journal. 1952;22:823–827. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Touchard A, Burke SE, Toner JL, Cromack K, Schwartz RS. Zotarolimus-eluting stents reduce experimental coronary artery neointimal hyperplasia after 4 weeks. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:988–993. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershlick A, De Scheerder I, Chevalier B, Stephens-Lloyd A, Camenzind E, Vrints C, Reifart N, Missault L, Goy JJ, Brinker JA, Raizner AE, Urban P, Heldman AW. Inhibition of restenosis with a paclitaxel-eluting, polymer-free coronary stent: the European evaLUation of pacliTaxel Eluting Stent (ELUTES) trial. Circulation. 2004;109:487–493. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000109694.58299.A0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg EP, Hadba AR, Almond BA, Marotta JS. Intratumoral cancer chemotherapy and immunotherapy: opportunities for nonsystemic preoperative drug delivery. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2002;54:159–180. doi: 10.1211/0022357021778268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graff CP, Wittrup KD. Theoretical analysis of antibody targeting of tumor spheroids: importance of dosage for penetration, and affinity for retention. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1288–1296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grube E, Silber S, Hauptmann KE, Mueller R, Buellesfeld L, Gerckens U, Russell ME. TAXUS I: six- and twelve-month results from a randomized, double-blind trial on a slow-release paclitaxel-eluting stent for de novo coronary lesions. Circulation. 2003;107:38–42. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000047700.58683.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang CW, Wu D, Edelman ER. Physiological transport forces govern drug distribution for stent-based delivery. Circulation. 2001;104:600–605. doi: 10.1161/hc3101.092214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath KR, Barry JJ, Miller KM. The Taxus drug-eluting stent: a new paradigm in controlled drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2006;58:412–436. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krol A, Maresca J, Dewhirst MW, Yuan F. Available volume fraction of macromolecules in the extravascular space of a fibrosarcoma: implications for drug delivery. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4136–4141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuan CT, Wikstrand CJ, Archer G, Beers R, Pastan I, Zalutsky MR, Bigner DD. Increased binding affinity enhances targeting of glioma xenografts by EGFRvIII-specific scFv. Int J Cancer. 2000;88:962–969. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20001215)88:6<962::aid-ijc20>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin AD, Vukmirovic N, Hwang CW, Edelman ER. Specific binding to intracellular proteins determines arterial transport properties for rapamycin and paclitaxel. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:9463–9467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400918101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovich MA, Creel C, Hong K, Hwang CW, Edelman ER. Carrier proteins determine local pharmacokinetics and arterial distribution of paclitaxel. J Pharm Sci. 2001;90:1324–1335. doi: 10.1002/jps.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovich MA, Edelman ER. Computational simulations of local vascular heparin deposition and distribution. Am J Physiol. 1996a;271:H2014–2024. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.271.5.H2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovich MA, Edelman ER. Tissue average binding and equilibrium distribution: an example with heparin in arterial tissues. Biophys J. 1996b;70:1553–1559. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79719-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintun MA, Raichle ME, Kilbourn MR, Wooten GF, Welch MJ. A quantitative model for the in vivo assessment of drug binding sites with positron emission tomography. Ann Neurol. 1984;15:217–227. doi: 10.1002/ana.410150302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses JW, Leon MB, Popma JJ, Fitzgerald PJ, Holmes DR, O’Shaughnessy C, Caputo RP, Kereiakes DJ, Williams DO, Teirstein PS, Jaeger JL, Kuntz RE. Sirolimus-eluting stents versus standard stents in patients with stenosis in a native coronary artery. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1315–1323. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul DR, Mcspadden SK. Diffusional Release of a Solute from a Polymer Matrix. Journal of Membrane Science. 1976;1:33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Riessen R, Isner JM. Prospects for site-specific delivery of pharmacologic and molecular therapies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;23:1234–1244. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90616-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers C, Edelman ER. Pushing drug-eluting stents into uncharted territory: simpler than you think--more complex than you imagine. Circulation. 2006;113:2262–2265. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.623470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakharov DV, Kalachev LV, Rijken DC. Numerical simulation of local pharmacokinetics of a drug after intravascular delivery with an eluting stent. J Drug Target. 2002;10:507–513. doi: 10.1080/1061186021000038382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheller B, Hehrlein C, Bocksch W, Rutsch W, Haghi D, Dietz U, Bohm M, Speck U. Treatment of coronary in-stent restenosis with a paclitaxel-coated balloon catheter. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2113–2124. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheller B, Speck U, Abramjuk C, Bernhardt U, Bohm M, Nickenig G. Paclitaxel balloon coating, a novel method for prevention and therapy of restenosis. Circulation. 2004;110:810–814. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000138929.71660.E0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheller B, Speck U, Schmitt A, Bohm M, Nickenig G. Addition of paclitaxel to contrast media prevents restenosis after coronary stent implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1415–1420. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)01056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serruys PW, Sianos G, Abizaid A, Aoki J, den Heijer P, Bonnier H, Smits P, McClean D, Verheye S, Belardi J, Condado J, Pieper M, Gambone L, Bressers M, Symons J, Sousa E, Litvack F. The effect of variable dose and release kinetics on neointimal hyperplasia using a novel paclitaxel-eluting stent platform: the Paclitaxel In-Stent Controlled Elution Study (PISCES) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.03.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh M, Lumpkin JA, Rosenblatt J. Mathematical-Modeling of Drug-Release from Hydrogel Matrices Via a Diffusion Coupled with Desorption Mechanism. Journal of Controlled Release. 1994;32:17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Takimoto CH, Rowinsky EK. Dose-intense paclitaxel: deja vu all over again? J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2810–2814. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe K, Serruys PW, Degertekin M, Guagliumi G, Grube E, Chan C, Munzel T, Belardi J, Ruzyllo W, Bilodeau L, Kelbaek H, Ormiston J, Dawkins K, Roy L, Strauss BH, Disco C, Koglin J, Russell ME, Colombo A. Chronic arterial responses to polymer-controlled paclitaxel-eluting stents: comparison with bare metal stents by serial intravascular ultrasound analyses: data from the randomized TAXUS-II trial. Circulation. 2004;109:196–200. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000109137.51122.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepe G, Zeller T, Albrecht T, Heller S, Schwarzwalder U, Beregi JP, Claussen CD, Oldenburg A, Scheller B, Speck U. Local delivery of paclitaxel to inhibit restenosis during angioplasty of the leg. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:689–699. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzafriri AR, Bercovier M, Parnas H. Reaction diffusion model of the enzymatic erosion of insoluble fibrillar matrices. Biophys J. 2002;83:776–793. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75208-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzafriri AR, Edelman ER. Endosomal receptor kinetics determine the stability of intracellular growth factor signalling complexes. Biochem J. 2007;402:537–549. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham TJ. Ligand-directed targeting of genes to the site of disease. Nat Med. 2003;9:135–139. doi: 10.1038/nm0103-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan F, Krol A, Tong S. Available space and extracellular transport of macromolecules: effects of pore size and connectedness. Ann Biomed Eng. 2001;29:1150–1158. doi: 10.1114/1.1424915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.