Abstract

Untreated depression remains one of the largest public health concerns. However, barriers such as unavailability of mental health providers and high cost of services limit the number of people able to benefit from traditional treatments. Though unsupported Internet interventions have proven effective at bypassing many of these barriers given their reach and scalability, attrition from interventions has been an ongoing concern. Microinterventions, or ultra-brief online tools meant to produce a rapid improvement in mood, may offer a way to provide the benefits of unsupported Internet interventions quickly, before attrition might occur. This study examined the immediate and lasting effects of three microinterventions (Breathing Exercises, Thought Records, and a Pleasant Activities Selector) on mood and distress. Participants (N=122) were randomized into three groups, each group completing two of the three microinterventions. Participants were asked to rate their mood and level of distress before and after completing the microintervention. Depression and perceived stress were assessed at baseline and at four weekly follow-ups. Although lasting effects were not found, a significant within-group reduction in distress and improvement in mood were observed immediately following the completion of the microintervention. This study demonstrates the potential benefits of microinterventions to individuals for their immediate needs vis-à-vis mood and distress.

Keywords: Internet intervention, depression, stress, clinical trial

1. INTRODUCTION

Most depressed individuals lack access to appropriate services for depression treatment (WHO Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse, 2012a). Rates of untreated depression range from 50% in the United States to over 75% in many parts of the world (Kessler et al., 2003; WHO Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse, 2012b). There is a multitude of reasons for such substantial undertreatment of depression, and some of the most frequently cited barriers to seeking mental health services for depression include unavailability of mental health providers, stigma surrounding mental health, and cost of services (Barney, Griffiths, Jorm, & Christensen, 2006; Diamant et al., 2004; Gulliver, Griffiths, & Christensen, 2010).

Internet interventions can offer individuals access to mental health resources by bypassing many of the common barriers. In particular, Internet interventions are advantageous because they can reach large numbers of people (Eells, Barrett, Wright, & Thase, 2014; Twomey & O’Reilly, 2017), which is especially true for unsupported Internet interventions given their scalability potential. Muñoz (2016) has suggested a set of four categories of behavioral interventions: traditional (without using digital tools), traditional augmented by digital tools, guided behavioral interventions, and self-help, automated, “unsupported” interventions. This study focuses on the fourth category. An “unsupported” Internet intervention thus refers to an Internet intervention that is fully automated and does not use a provider, therapist, or any other form of human contact as part of the intervention (Leykin, Muñoz, Contreras, & Latham, 2014). Although human contact may increase efficacy (Andersson & Cuijpers, 2009), it also places a limit on scalability and reach, as it necessarily increases costs and logistical difficulties. Randomized control trials have confirmed the effectiveness of both supported and unsupported Internet-based interventions for the reduction of depression and other mental and physical health concerns (Andersson & Cuijpers, 2009; Andrews, Cuijpers, Craske, McEvoy, & Titov, 2010; Buntrock et al., 2016; Christensen, Griffiths, & Jorm, 2004; Cuijpers et al., 2009).

Like face-to-face treatments, Internet interventions often suffer from poor adherence and high attrition. The modal number of face-to-face therapy sessions is one, as was found for depressed individuals in a community clinic (Connolly Gibbons et al., 2011), and Internet interventions participants often log in only once or twice before dropping out permanently. This phenomenon is seen in both supported and unsupported Internet interventions (Eysenbach, 2005; Van Ballegooijen, Cuijpers, & Van Straten, 2014), however, rates of attrition are particularly high for unsupported Internet interventions compared to supported interventions (Cavanagh, 2010; Christensen, Griffiths, Groves, & Korten, 2006). Attrition may be partially mitigated by including human support, however, as mentioned above, support would also hinder the potential reach and scalability (Mohr, Cuijpers, & Lehman, 2011).

Many participants drop out of Internet Interventions early (Christensen, Griffiths, Groves, & Korten, 2006; Leykin, Muñoz, Contreras, & Latham, 2014), leaving researchers to speculate as to the reasons why. It is possible that a sizable proportion of participants may only have a limited amount of time that they might be willing to spend on such interventions, or they may be reluctant to complete a long intervention for other reasons. Thus, microinterventions – interventions that can be completed in a few minutes, either in a single or a repeated administration, may respond to the needs of those individuals. Indeed, the brevity of microinterventions is likely more closely in line with the expectations of consumers of digital information, who may routinely interact with fast-paced, user-driven, interactive web content, and for whom web experience may be associated with speed, rather than delay. The very few early trials of brief internet interventions have shown promise (Ayers, Fitzgerald, & Thompson, 2015; Bunge, Williamson, Cano, Leykin, & Muñoz, 2016; Lokman et al., 2017), however, more research is needed to better understand the efficacy and the outcomes of microinterventions.

The purpose of our study was to pilot a microintervention website, to gather data on the use of the website as well as preliminary data on immediate and lasting effects of the three microinterventions that comprised the site. The three microinterventions within our site were based on tools commonly used as part of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). Tools from CBT were used due to the substantial findings of the effectiveness of self-guided Internet-based CBT (iCBT) in the reduction of depression (Karyotaki, Riper, Twisk, et al., 2017). In addition, the highly structured nature of CBT interventions lend themselves well to unsupported interventions (Schröder, Berger, Westermann, Klein, & Moritz, 2016). We examined the rates of utilization, as well as the short-term and lasting improvements in mood and stress levels.

2. METHODS

2.1. Participants

Participants were 122 individuals from a cohort of participants who had previously (whether recently or several months prior) screened positive or at risk for major depression via an online depression screener (Leykin, Muñoz, & Contreras, 2012). That online depression screener was used to help determine participant eligibility; participants in the current study also completed the PHQ-9 (Spitzer, Kroenke, & Williams, 1999) at the start of the study to determine their current depression levels. Participants were at least 18 years of age, and able to read and understand English.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9; Spitzer, Kroenke, & Williams, 1999)

PHQ-9 is a widely used measure for screening for the presence of major depressive episodes according to the DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994), as well as to assess the severity of symptoms. It has been shown to have outstanding psychometric properties (Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001). For the purposes of this study, the duration of symptoms assessed by the PHQ-9 was shortened to 1 week. The potential PHQ-9 scores range from 0 to 27, with scores of 5–9 indicating mild depression, 10–14 – moderate depression, 15–19 -- moderately severe depression, and 20–27 -- severe depression, based on the official manual. Scores of 10 and over are suggestive of a presence of a major depressive episode (Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001). Norms for this measure can be found in the original publication by the PHQ-9 authors (Spitzer, Kroenke, & Williams, 1999).

2.2.2. Perceived Stress Scale-10 (PSS; Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983)

PSS is a 10-item self-report measure assessing current perceived stress, and is likely the most widely used and well-validated perceived stress measure (Cohen et al., 1983). For the purposes of this study, the duration of symptoms assessed by the PSS was shortened to 1 week. Scores on the PSS range from 0 to 40, with higher scores being indicative of more stress. Scores falling between 0 and 13 are considered low stress, scores falling between 14 and 26 are considered moderate stress, and scores 27 to 40 are considered high stress. Further information regarding norms for this measure can be found in the authors’ original publication (Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983).

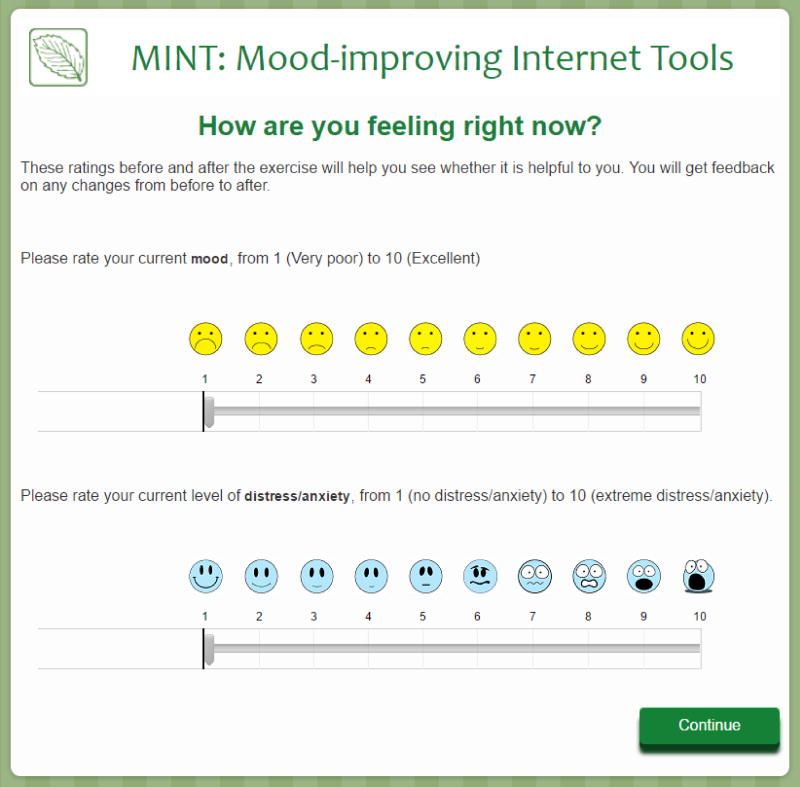

2.2.3. Mood Rating

Participants indicated their current mood using a visual analog “slider”-type scale, from 1 (very poor) to 10 (excellent). In addition to using numbers, a “smiley-face” icon was used on all 10 points of the scale to indicate a progression of mood from very poor (extreme frown face) to excellent (extreme happy face) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mood and distress/anxiety rating scales

2.2.4. Distress/Anxiety Rating

Participants rated their current distress/anxiety, also via a slider, on a scale from 1 (no distress/anxiety, also indicated by a happy face) to 10 (extreme distress/anxiety, also indicated by a panic face). The scale was based on a subjective units of distress scale (SUDS) rating that would be seen in a traditional therapy setting.

Demographic variables (age, gender) were ported from the referring study (Leykin et al., 2012). Age was not normally distributed (the sample was predominantly young); to facilitate analyses, age was recategorized into three common age categories: young adults (18 to 35 years old), middle-age adults (36 to 55 years old), and older adults (56 years old and over).

2.3. Microinterventions

The microinterventions were selected based on the following criteria: simple to explain and easy to use; commonly used as part of psychotherapy; takes less than a couple of minutes to use; existing theoretical and empirical basis for mood improvement following intervention use. Considering that the website was meant for repeated use (e.g., participants could return to it as many times as they wished), an additional criterion was variability between uses, to reduce participant boredom and increase the likelihood of future utilization. The following microinterventions were developed:

2.3.1. Pleasant Activity Selector

Pleasant activities is a common part of behavioral therapy for depression (Dimijian et al., 2011; Zeiss, Lewinsohn, & Muñoz, 1979) Behavioral theory states that completing pleasant activities improves mood, which creates positive reinforcement to become more active and engaged (Hopko, Lejuez, Ruggiero, & Eifert, 2003). Participants were asked to select the categories of activities they would like to do (e.g., “With others”, “Free”, “In nature”, “In the city”); multiple categories could be selected. The website then displayed the possible activities that fit the desired filters. Participants were asked to select which activities from the displayed list they planned to do, and were offered to have the list of chosen activities emailed to them. The microintervention only consisted of selecting a pleasant activity, not necessarily completing it (though participants were obviously could and encouraged to do so). However, some research suggests that the act of selecting and scheduling activities may improve mood (Cuijpers, Van Straten, & Warmerdam, 2006; Riebe, Yu-Fan, Unutzer, & Vannoy, 2012). Participants who returned to the site to use the Pleasant Activity Selector again were reminded of the activities they last selected, and were asked whether they had done them. The immediate mood and distress ratings were completed by participants before beginning the microintervention and after selecting (rather than completing) Pleasant Activities.

2.3.2. Thought Record

An automatic thought record is one of the key tools of the practitioners of cognitive therapy for depression (A. T. Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979; J. Beck, 1995). The thought record helps patients log and evaluate maladaptive thoughts, and replace these thoughts with ones that are more realistic and adaptive, which improves mood. Participants were led through the steps of developing a thought record. Participants who returned to the site to complete another Thought Record were asked whether they preferred minimal instructions instead of full guidance, to streamline the process. Participants could email the completed thought record to themselves. Participants had access to a log of their past five entries. Immediate mood and distress ratings were completed by participants before beginning the microintervention and after filling out the thought record.

2.3.3. Breathing Exercise

Breathing exercise is a commonly recommended practice to reduce stress, and there is some evidence that it can be an effective tool against anxiety disorders (McPherson & McGraw, 2013) and depression in certain populations (Chan, Cheung, Tsui, Sze, & Shi, 2011; Chan et al., 2012). The breathing exercise prompted participants to take long, slow, deep breaths accompanied by an animation (e.g., an inflating/deflating bubble); one of five available animations was randomly selected for each visit to increase variability of the tool, and the speed of the visualization could be adjusted by participants. Participants were encouraged to concentrate on the visualization to reduce interference of intrusive thoughts. Before beginning the microintervention and immediately following the completion of the breathing exercise, participant mood and distress ratings were collected.

2.4. Procedures

Participants received an email inviting them to take part in this study. Interested participants clicked on the link embedded in the email that redirected them to the site where they were shown the informed consent document. Consenting participants created a password to access the site in the future. Participants were randomized to receive 2 of the 3 microinterventions, and completed the PHQ-9 and the PSS. Randomizing to pairs of intervention is preferable to being randomized to either a single microintervention or to being given access to all three microinterventions, for several reasons. First, it would allow participants to choose an intervention based on their preference, which would also help researchers understand participants preferences. Additionally, having access to two interventions (as opposed to one) might promote greater interest. Further, it could make it possible to understand the relative efficacy of microinterventions (as opposed to having no randomization).

The homepage of the study contained the description of the microinterventions to which participants have been randomized, and buttons to enter the interventions. After selecting a microintervention, participants were prompted to enter their “pre-intervention” mood and anxiety/distress via Mood Rating and the Distress/Anxiety Rating. Participants then completed the tool of their choice, and logged their “post-intervention” mood and distress/anxiety. If any changes in mood or distress were observed from before to after tool use, positive or negative, participants were given feedback on those changes. At 1, 2, 3, and 4 weeks after the date of consent, participants were sent an email containing a link to the site, inviting them to complete the PHQ-9 and the PSS during their subsequent visit.

Participants in the study were not compensated financially or otherwise. The Institutional Review Board of the University of California, San Francisco approved all study procedures.

2.5. Data analysis

To test whether randomized conditions (intervention pairs) produced different rates of change over time, two HLM models were constructed, with either the PSS score or the PHQ-9 score as the dependent variable, and the interaction of the randomized condition (as a three-level variable) and the time variable as the main predictor, controlling for age and gender (as these were previously found to predict adherence, Christensen, Griffiths, & Farrer, 2009; Karyotaki et al., 2015) and with main effects of time and randomized conditions. HLM permits the analysis of all available data by allowing for observations in longitudinal data to be randomly missing without casewise deletion, permitting the analysis of all available data; however, with too much missing data, the outcomes are difficult to interpret. For HLM analyses, unstructured covariance structure was specified, which allows for possible correlations between random terms (slope and intercept).

To test whether individual uses of each microintervention resulted in within-group improvement of rating of mood and distress/anxiety, repeated measures ANCOVAs were used, with either mood or distress rating as the repeated dependent variable, time as the main predictor, and controlling for age and gender. Further, to compare whether different tools resulted in different improvements, two additional repeated measures ANCOVAs were constructed, adding the microintervention X time interaction as the main predictor.

3. RESULTS

The 122 participants in our study came from 35 different countries. The countries which had the most participants were the United Kingdom (20%), the United States (14%), and India (14%). The mean age of participants was 32.4 years (SD = 13.2), and 71.3% of the participants were female.

3.1. Utilization patterns

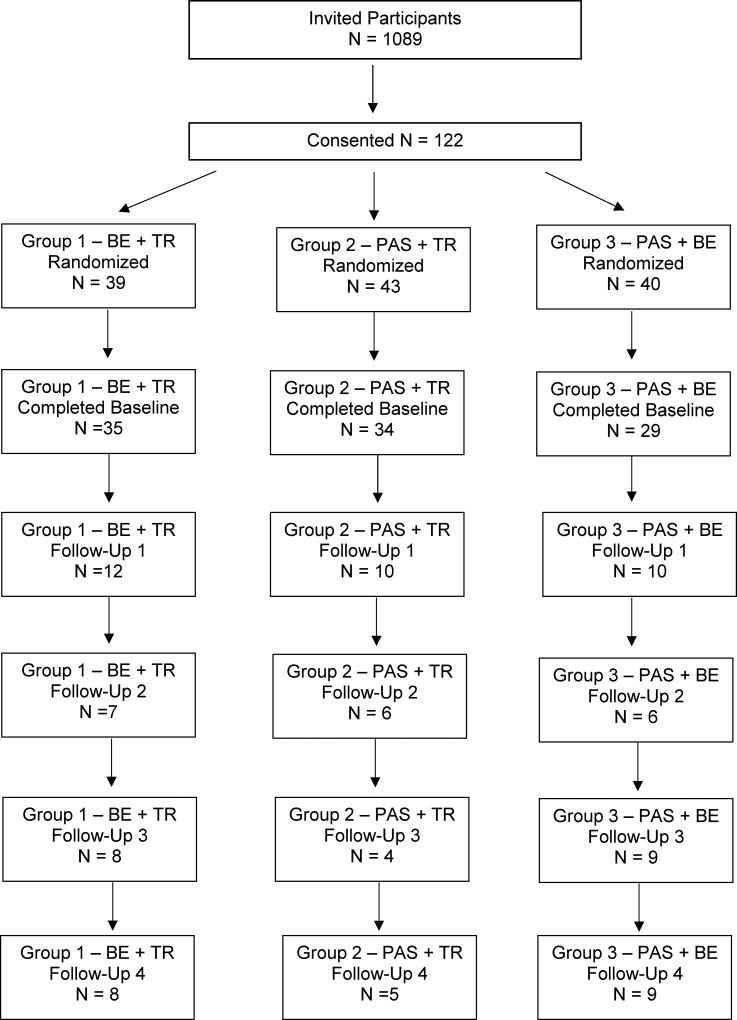

The number of log-ins to the MINT website were examined to determine adherence and attrition. Slightly less than half (42%) of participants only logged into the intervention once, 31% of participants logged into the intervention twice, while 20% of participants logged into the intervention three to five times. Only 7% of participants logged into the intervention six or more (up to 9) times. No significant difference was found in the number of log-ins to MINT based on the condition to which the participant was randomized (Wald Chi-Square (2) = 1.48, p = .48). Regarding interest in specific microinterventions, no pronounced differences were noted: Thought Record and Breathing Exercise were selected approximately equally (m = 1.5 (1.2), range: 0–5 times; and m = 1.5 (1.4), range: 0–5 times, respectively), and Pleasant Activities Selector was chosen slightly less often (m = 1.3 (1.4), range: 0–7 times). The dropout rate in this study was very high (Figure 2). Of the 122 who consented to participate, 98 (80.3%) completed baseline assessment (PHQ-9 and PSS), 26.2% completed Follow-up 1, 16.4% completed Follow-up 2, 17.2% completed Follow-up 3, and 18.9% completed Follow-up 4. At least one follow-up was available for 38.5% participants (n=47).

Figure 2.

CONSORT diagram

3.2. Intervention effects – lasting effects

The scores on the PHQ-9 and on the PSS are presented in Table 1. HLM models revealed that no randomized condition was superior to another, either in improving symptoms of depression (PHQ-9 scores) over time, F(2, 71) = .97, p = .39, or improving perceived stress (PSS scores) over time (F(2, 35) = .15, p = .86. Likewise, it did not appear that the website overall was successful in reducing depression symptoms over time, F(1, 79) =.01, p = .93. Perceived stress appeared to reduce slightly, but not significantly, F(1, 36) = 2.86, p = .099. However, given the considerable dropout in this study (Figure 1), these results are difficult to interpret. The high level of attrition in this study is further discussed below.

Table 1.

Baseline and Follow-up Scores on the PHQ-9 and PSS for All Groups (Mean and SD)

| Group 1 (BE +TR) | Group 2 (PAS +TR) | Group 3 (PAS + BE) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHQ-9 | PSS | PHQ-9 | PSS | PHQ-9 | PSS | |

| BL | 14.17 (6.8) | 25.05 (5.31) | 13.62 (6.35) | 25.23 (5.51) | 11.95 (6.85) | 23.86 (5.75) |

| FU1 | 13.81 (7.49) | 26.00 (4.89) | 11.50 (5.64) | 20.70 (6.89) | 11.22 (6.01) | 24.77 (5.28) |

| FU2 | 13.85 (8.71) | 23.57 (5.59) | 10.50 (6.15) | 24.00 (4.14) | 7.17 (1.94) | 21.50 (4.50) |

| FU3 | 12.87 (9.37) | 27.00 (6.48) | 10.50 (4.51) | 20.00 (7.87) | 11.44 (8.57) | 22.78 (5.38) |

| FU4 | 11.13 (7.06) | 24.13 (5.59) | 14.00 (3.16) | 24.40 (4.78) | 10.56 (5.98) | 23.33 (4.98) |

Note: BL: Baseline; FU1-4: Follow-ups 1 through 4; BE Breathing Exercise; PAS: Pleasant Activity Selector; TR: Thought Record.

3.3. Intervention effects – immediate effects

Immediate effects were assessed by comparing pre- and post-use Mood and Distress/Anxiety Ratings, for every instance of use of a microintervention. Unlike the analyses described above, which were dependent on participants returning for follow-up and were thereby affected by follow-up attrition, immediate effects were evaluated at the time of completion of a microintervention itself, and were thus unaffected by follow-up attrition. Participants initiated a use of a microintervention 297 times. Pre-microintervention mood and pre-microintervention distress/anxiety ratings were completed 293 times (99% completion rate). Post-microintervention mood and post-microintervention distress/anxiety ratings were completed 246 times (83% completion rate). Both pre- and post-microintervention ratings were available for mood for 82% of initiations, and for distress/anxiety – for 83% of initiations. The scores on the mood and distress/anxiety ratings are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Before and after mood and distress/anxiety ratings for each microintervention, across all instances of microintervention use (Mean and SD)

| Mood pre- microintervention |

Mood post- microintervention |

Distress / Anxiety pre- microintervention |

Distress / Anxiety post- microintervention |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breathing Exercise | 5.19 (1.78) | 5.76 (1.73) | 4.98 (1.88) | 4.33 (1.60) |

| Thought Record | 4.86 (2.06) | 5.44 (2.11) | 5.51 (2.13) | 4.96 (2.13) |

| Pleasant Activities Selector | 5.23 (1.83) | 5.63 (1.79) | 5.14 (1.94) | 4.76 (1.84) |

Repeated measures ANCOVAs suggested that all microinterventions improved mood and reduced distress. Breathing Exercise reduced both distress/anxiety from pretest to posttest (F(1, 85) = 41.033, p <.0001, partial eta-squared = .326) as well as improved mood from pretest to posttest (F(1, 87) = 18.334, p <.0001, partial eta-squared=.174). The Thought Record likewise reduced distress/anxiety (F(1, 71) = 12.289, p <.001, partial eta-squared = .148) and improved mood (F(1, 67) = 6.698, p <.012, partial eta-squared =.091) from pretest to posttest, though the effect sizes appeared to be smaller than for the Breathing Exercise. Finally, the Pleasant Activities Selector also improved distress/anxiety (F( 1, 78) = 11.784, p <.001, partial eta-squared = .131), but its effect on mood did not quite cross the significance threshold (F(1, 77) = 3.734, p =.057, partial eta-squared =.046).

Comparing the immediate effects of our three microinterventions by examining the time-by-microintervention interaction in the repeated measures ANCOVA model, no differences were found between the three microinterventions for improvements in mood (F( 2, 237) = .45, p = .64). However, differences between microinterventions were noted in the reductions of distress (F( 2, 240) = 3.98, p = .02), with Breathing Exercise producing the largest change.

4. DISCUSSION

The goals of the study were to examine the utilization of unsupported Internet microinterventions website, and to understand its efficacy in regards to improving mood and distress/anxiety immediately and improving symptoms of depression and perceived stress at follow-up. The results of the study were mixed. Although there were indications of immediate gains in mood and reduction in distress/anxiety, no lasting improvements were observed at follow-up in depressive symptoms measured by the PHQ-9 or perceived stress measured by PSS.

The adherence to and engagement with internet interventions is an ongoing concern (Cavanagh, 2010), and the utilization patterns of this site were largely similar to those reported in other studies of unsupported interventions, such as the open enrollment trial of MoodGYM (Christensen et al., 2006). However, unlike these full-scale interventions, which deliver a variety of content that participants can explore, our website delivered the same two tools that could be used in a minute or so to each randomized participant at each visit. Though these microinterventions were designed to be somewhat variable for each visit (e.g., different animations for breathing exercises, for instance), the content did not change. The fact that over half of participants visited the website more than once and over a quarter of the participants – three or more times, is therefore encouraging. Future versions of this site could perhaps incorporate more variety of content and additional microinterventions to increase participants’ engagement. However, the rates of follow-up for this study were very low. In one condition, for instance, only five out of the 43 initially randomized participants completed fourth week follow-up assessment, and the other conditions were not markedly superior vis-à-vis follow-up rates (Figure 2). This attrition may have influenced our ability to detect any changes in depression symptoms and perceived stress levels from baseline. High rates of attrition are unfortunately commonplace in the Internet interventions literature and are particularly salient for unsupported Internet interventions (Eysenbach, 2005; Cavanagh, 2010; Christensen et al., 2006). Aside from attrition, our lack of positive results in terms of lasting effects may also suggest that microinterventions (at least those tested) may lack the therapeutic potency to bring about lasting change. This finding would be consistent with previous literature (Bunge et al., 2016). It is possible that due to their brevity, microinterventions do not sufficiently activate the underlying psychological mechanisms that are theorized to produce meaningful change in mood as thoroughly as more in-depth interventions, digital or otherwise.

Microinterventions, however, might be a useful tool for immediate or very short-term mood management strategy. Indeed, our immediate outcomes suggest that microinterventions could potentially be helpful in producing immediate reduction in distress/anxiety and improvement in mood. Being able to improve mood or reduce distress in the moment, even if this improvement is not long-lasting, may provide evidence to individuals that improving mood or reducing anxiety or distress is feasible. Though all of the microinterventions showed decreased distress and improved mood, the Breathing Exercise produced the largest effect, followed by the Thought Record, and then the Pleasant Activity Selector. That Breathing Exercise was particularly effective is not surprising, considering that its purpose is to produce immediate results, and specifically on distress and anxiety, where Breathing Exercise appeared to have the largest effect. Similarly, though research suggests that both planning and scheduling pleasant activities (Cuijpers, Van Straten, & Warmerdam, 2006; Riebe, Yu-Fan, Unutzer, & Vannoy, 2012) and engaging in doing them (Dimidjian et al., 2006) can improve mood, much of the research on behavioral activation suggests that the act of completing pleasant activities is especially therapeutically potent. The fact that some reductions in distress and improvements in mood were evident from merely selecting a pleasant activity, as our microintervention was designed to help the user to do, suggest that some of the effect might come from the increased hopefulness and positive anticipation from thinking of a future pleasant activity or planning or scheduling an activity.

There are several limitations that should be acknowledged. Participants were recruited from a previous screening study that enrolled participants looking for depression information online (Leykin et al., 2012); though this population represents the intended audience of this intervention, the results may not generalize to other recruitment strategies. A control condition was not included, which prevents us from making strong causal influences about the effects of microinterventions; it is possible that the results may be explained by spontaneous improvement in mood and reduction of distress/anxiety, by repeated measurement effects, by social desirability, or other factors. As discussed above, high attrition rates in our studies precluded a conclusive determination regarding the longer-term effectiveness of our intervention.

The current study contributes to the emerging literature on microinterventions (Ahmedani, Crotty, Abdulhak, & Ondersma, 2015; Ayers et al., 2015; Bunge et al., 2016; Lokman et al., 2017), and offers encouraging data to support continued research on such interventions. Internet microinterventions may offer quick, effective means of quickly improving mood and reducing distress. However, such effects may not be robust enough to produce lasting changes in symptoms of depression or stress. Unsupported Internet intervention delivery provides scalability and “non-consumability” (Muñoz et al., 2016); reducing the size of such tools to the format of microinterventions creates easy-to-use and effective tools that may improve the acceptability and broaden the applicability of Internet interventions.

Highlights.

Three unsupported interactive microinterventions (Breathing Exercises, Thought Records, and a Pleasant Activities Selector) were evaluated.

122 participants were randomized into pairs of microinterventions.

Significant within-group improvement in mood and distress were observed immediately following the completion of microinterventions.

Lasting effects (4 weeks) on depression symptoms and level perceived stress were not observed.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by UCSF Academic Senate Resource Allocation Program grant (Leykin, P.I.) and by NIMH grant 5K08MH091501 (Leykin, P.I.). Funding sources had no involvement in study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, writing the report or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

We would like to express our thanks to Nancy E. Adler, PhD, and the Center for Health and Community for their support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interests

None

References

- Ahmedani BK, Crotty N, Abdulhak MM, Ondersma SJ. Pilot feasibility study of a brief, tailored mobile health intervention for depression among patients with chronic pain. Behav Med. 2015;41(1):25–32. doi: 10.1080/08964289.2013.867827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G, Cuijpers P. Internet-based and other computerized psychological treatments for adult depression: a meta-analysis. Cogn Behav Ther. 2009;38(4):196–205. doi: 10.1080/16506070903318960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G, Cuijpers P, Craske MG, McEvoy P, Titov N. Computer therapy for the anxiety and depressive disorders is effective, acceptable and practical health care: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2010;5(10):e13196. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayers S, Fitzgerald G, Thompson S. Brief Online Self-help Exercises for Postnatal Women to Improve Mood: A Pilot Study. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19(11):2375–2383. doi: 10.1007/s10995-015-1755-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barney LJ, Griffiths KM, Jorm AF, Christensen H. Stigma about depression and its impact on help-seeking intentions. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;40(1):51–54. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery G. Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Beck J. Cognitive Therapy: Basics and Beyond. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bunge EL, Williamson RE, Cano M, Leykin Y, Muñoz RF. Mood management effects of brief unsupported Internet interventions. Internet Interventions. 2016;5:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buntrock C, Ebert DD, Lehr D, Smit F, Riper H, Berking M, Cuijpers P. Effect of a Web-Based Guided Self-help Intervention for Prevention of Major Depression in Adults With Subthreshold Depression: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;315(17):1854–1863. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.4326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh K. Turn on, tune in and (don’t) drop out: Engagement, adherence, attrition, and alliance with Internet-based interventions. In: Bennett-Levy J, Richards DA, editors. Oxford Guide to Low Intensity CBT Interventions. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2010. pp. 229–233. [Google Scholar]

- Chan AS, Cheung MC, Tsui WJ, Sze SL, Shi D. Dejian mind-body intervention on depressive mood of community-dwelling adults: a randomized controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2011;2011:473961. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan AS, Wong QY, Sze SL, Kwong PP, Han YM, Cheung MC. A Chinese Chan-based mind-body intervention for patients with depression. J Affect Disord. 2012;142(1–3):283–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen H. Adherence in internet interventions for anxiety and depression: Systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2009;11(2):e13. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen H, Griffiths K, Groves C, Korten A. Free range users and one hit wonders: community users of an Internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy program. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006;40(1):59–62. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen H, Griffiths KM, Jorm AF. Delivering interventions for depression by using the Internet: randomised controlled trial. British Medical Journal. 2004;328(7434):265. doi: 10.1136/bmj.37945.566632.EE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of health and social behavior. 1983;24(4):385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly Gibbons MB, Rothbard A, Farris KD, Wiltsey Stirman S, Thompson SM, Scott K, Crits-Christoph P. Changes in psychotherapy utilization among consumers of services for major depressive disorder in the community mental health system. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38(6):495–503. doi: 10.1007/s10488-011-0336-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P, Marks IM, van Straten A, Cavanagh K, Gega L, Andersson G. Computer-aided psychotherapy for anxiety disorders: a meta-analytic review. Cogn Behav Ther. 2009;38(2):66–82. doi: 10.1080/16506070802694776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijipers P, Van Straten A, Warmerdam L. Behavioral activation treatments for depression: A meta analysis. Clinical Pychology Review. 2007;27(3):18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamant AL, Hays RD, Morales LS, Ford W, Calmes D, Asch S, Gelberg L. Delays and unmet need for health care among adult primary care patients in a restructured urban public health system. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(5):783–789. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.5.783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimidjian S, Barrera M, Martell C, Muñoz RF, Lewinsohn PM. The origins and current status of behavioral activation treatments for depression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2011;7:1–38. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032210-104535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimidjian S, Hollon SD, Dobson KS, Schmaling KB, Kohlenberg RJ, Addis ME, Jacobson NS. Randomized trial of behavioral activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant medication in the acute treatment of adults with major depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74(4):658–670. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.4.658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eells TD, Barrett MS, Wright JH, Thase M. Computer-assisted cognitive-behavior therapy for depression. Psychotherapy (Chic) 2014;51(2):191–197. doi: 10.1037/a0032406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenbach G. The law of attrition. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2005;7(1):e11. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7.1.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulliver A, Griffiths KM, Christensen H. Percieved barriers and facilitatos to mental health help-seeking in young people: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10(113) doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopko DR, Lejuez CW, Ruggiero KJ, Eifert GH. Contemorary behavioral activation treatments for depression: Procedures, principles, and progress. Clinical Psychology Review. 2003;23:699–717. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(03)00070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karyotaki E, Kleiboer A, Smit F, Turner DT, Mira Pastor A, Andersson G, Berger T, Botella C, Breton JM, Carlbring P, Christensen H, de Graaf E, Griffiths K, Donker T, Farrer L, Huibers M, Lenndin J, Mackinnon A, Meyer B, Moritz S, Riper H, Spek V, Vernmark K, Cuijpers P. Predictors of treatment dropout in self-guided web-based interventions for depression: An individual patient data meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine. 2015;17:1–10. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715000665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karyotaki E, Riper H, Twisk J, Hoogendoorn A, Kleiboer A, Mira A, Mackinnon A, Meyer B, Botella C, Littlewood E, Andersson G, Christensen H, Klein JP, Schröder J, Bretón-López J, Scheider J, Griffiths K, Farrer L, Huibers MJH, Phillips R, Gilbody S, Moritz S, Berger T, Pop V, Spek V, Cuijpers P. Efficacy of Self-guided Internet-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in the Treatment of Depressive Symptoms: A Meta-analysis of Individual Participant Data. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(4):351–359. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leykin Y, Muñoz RF, Contreras O. Are consumers of Internet health information “cyberchondriacs”? Characteristics of 24,965 users of a depression screening site. Depression and Anxiety. 2012;29:71–77. doi: 10.1002/da.20848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leykin Y, Muñoz RF, Contreras O, Latham MD. Results from a trial of an unsupported Internet intervention for depressive symptoms. Internet Interv. 2014;1(4):175–181. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lokman S, Leone SS, Sommers-Spijkerman M, van der Poel A, Smit F, Boon B. Complaint-Directed Mini-Interventions for Depressive Complaints: A Randomized Controlled Trial of Unguided Web-Based Self-Help Interventions. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(1):e4. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson F, McGraw L. Treating generalized anxiety disorder using complementary and alternative medicine. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine. 2013;19(5):45–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr DC, Cuijpers P, Lehman K. Supportive accountability: a model for providing human support to enhance adherence to eHealth interventions. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(1):e30. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz RF. The Efficiency Model of Support and the Creation of Digital Apothecaries. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2016;24(1):46–49. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz RF, Bunge EL, Chen K, Schueller SM, Bravin JI, Shaughnessy EA, Pérez-Stable EJ. Massive Open Online Interventions: A Novel Model for Delivering Behavioral-Health Services Worldwide. Clinical Psychological Science. 2016;4(2):194–205. [Google Scholar]

- Riebe G, Fan MY, Unutser J, Vannoy S. Activity scheduling as a core component of effective care management for late-life depression. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2012;27(12):1298–1304. doi: 10.1002/gps.3784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder J, Berger T, Westermann S, Klein JP, Moritz S. Internet interventions for depression: new developments. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 2016;18(2):203–212. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2016.18.2/jschroeder. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282(18):1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twomey C, O’Reilly G. Effectiveness of a freely available computerised cognitive behavioural therapy programme (MoodGYM) for depression: Meta-analysis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2017;51(3):260–269. doi: 10.1177/0004867416656258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Vallegooijen W, Cuijpers P, Van Straten A, Karyotaki E, Anderson G, Smit J, Riper H. Adherence to internet-based and face-to-face cognitive behavioural therapy for depression: A meta-anlaysis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(7):e100674. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse. Depression: A global public health concern In Depression: A Global Crisis. Occoquan, VA: World Federation for Mental Health; 2012a. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse. Fact Sheet: Depression around the world In Depression: A Global Crisis. Occoquan, VA: World Federation for Mental Health; 2012b. [Google Scholar]

- Zeiss AM, Lewinsohn PM, Muñoz RF. Nonspecific improvement effects in depression using interpersonal skills training, pleasant activities schedules, or cognitive training. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1979;47:427–439. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.47.3.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]