Abstract

Importance

Opioid use disorder (OUD) frequently begins in adolescence and young adulthood. Intervening early with pharmacotherapy is recommended by major professional organizations. No prior national studies have examined the extent to which adolescents and young adults (collectively, “youth”) with OUD receive pharmacotherapy.

Objective

To identify time trends and disparities in receipt of buprenorphine and naltrexone among youth with OUD in the US.

Design

Retrospective cohort.

Setting

Enrollment and complete health insurance claims of 9.7 million youth using de-identified data from Optum, a national commercial insurance database.

Participants

Youth aged 13–25 years who received a diagnosis of OUD between January 1, 2001 and June 30, 2014.

Exposures

Sex, age, race/ethnicity, neighborhood education and poverty levels, metropolitan area, census region, and year of diagnosis.

Main Outcome and Measures

Dispensing of a medication (buprenorphine or naltrexone) within 6 months of first receiving an OUD diagnosis. We identified time trends and used multivariable logistic regression to determine sociodemographic factors associated with medication receipt.

Results

Among 20,822 youth diagnosed with OUD (0.2% of the sample), 13,698 (65.8%) were male and 17,119 (82.4%) were non-Hispanic white. Mean age (SD) was 21.0 (2.5) years at first observed diagnosis. The diagnosis rate of OUD increased nearly 6-fold from 2001 to 2014. Overall, 5,580 (26.8%) youth were dispensed a medication within 6 months of diagnosis, with 4,976 (89.2%) of medication-treated youth receiving buprenorphine and 604 (10.8%) receiving naltrexone. Medication receipt increased more than 10-fold from 3.0% in 2002 (when buprenorphine was introduced) to 31.8% in 2009, but declined in subsequent years. In multivariable analyses, younger individuals were less likely to receive medications (adjusted probability for age 13–15 years, 1.4%; 16–17 years, 9.7%; 18–20 years, 22.0%; 21–25 years, 30.5%; p<0.001 for difference). Females (20.3%) were less likely than males (24.4%) to receive medications (p<0.001), as were non-Hispanic black (14.8%) and Hispanic (20.0%) youth compared to non-Hispanic white youth (23.1%; p<0.001).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this first national study of buprenorphine and naltrexone receipt among youth, dispensing increased over time. Nonetheless, only 1 in 4 commercially insured youth with OUD received pharmacotherapy, and disparities based on sex, age, and race/ethnicity were observed.

MeSH Keywords: buprenorphine, naltrexone, adolescent, young adult, opioid-related disorders

INTRODUCTION

Drug overdose deaths in the United States – the majority of which are caused by prescription opioids and heroin – have reached an unprecedented level, having tripled from 2000 to 2014 and surpassed annual mortality from motor vehicle crashes.1–6 Hospitalizations and emergency department visits for overdose,7,8 drug treatment admissions,9 and new hepatitis C infections10 related to opioids have risen dramatically over a similar timeframe. Risk for opioid use disorder (OUD) frequently begins in adolescence and young adulthood, with 7.8% of high school seniors reporting lifetime non-medical prescription opioid use.11 Two-thirds of individuals in treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD) report that their first use was before age 25, and one-third report that it was before age 18.9 Intervening early in the development of OUD is critical for preventing premature death and lifelong harm.12 However, only 1 in 12 adolescents and young adults (collectively, “youth”)13 who need care for any type of addiction receive treatment.14 Compounding this, black and Hispanic youth are even less likely than white youth to receive addiction treatment.15,16

Buprenorphine, a partial opioid agonist, and naltrexone, an opioid antagonist, prevent relapse and overdose among youth with OUD.17–21 The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved buprenorphine for adolescents ≥16 years in 2003. Oral naltrexone has been FDA-approved for individuals ≥18 years since 1984, and the FDA approved a long-acting injectable formulation in 2010. Unlike methadone, both buprenorphine and naltrexone can be offered in primary care and subspecialty settings in the US.22 However, there is a widespread shortage of physicians who have received the waiver certification required to prescribe buprenorphine, and of all physicians who are certified in the US, only 1% are pediatricians.23 Naltrexone does not require special prescriber certification and is not an opioid agonist (and thus may be viewed more favorably by some physicians);24 nonetheless, it has historically been less commonly prescribed to adults than buprenorphine.25 Despite the much earlier documented efficacy and FDA approval of buprenorphine and naltrexone, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) did not release a policy statement calling for the use of pharmacotherapy for youth with OUD until August 2016.26 The absence of such a statement may have delayed adoption of pharmacotherapy by pediatricians, even despite preexisting recommendations from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration24 and amidst a worsening youth opioid epidemic.7

We know of no large-scale studies to date that have examined what percentage of youth with OUD receive pharmacotherapy. Understanding which youth receive medications, which medication (buprenorphine or naltrexone) they receive, and how medication dispensing varies by sociodemographic characteristics is critical in order to inform the expansion of addiction treatment services, a national priority in the US.27,28 We identified trends and disparities in pharmacotherapy for youth during a time of escalating prevalence of OUD.

METHODS

Data Source

We used de-identified Optum data (OptumInsight, Eden Prairie, MN), which contain enrollment records and all inpatient, outpatient, emergency department, and pharmacy claims from a large US commercial health insurer with members in all 50 states and Washington, DC. All members in the dataset had prescription drug coverage. The Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Sample Selection

The primary analytic sample included all youth of age 13–25 years who received a diagnosis of OUD between January 1, 2001 and June 30, 2014 with ≥6 months of continuous enrollment following the date of diagnosis (allowing a final date of follow-up of December 31, 2014). We included young adults up to age 25 since they often still receive care from pediatric providers, are included in national definitions of “youth”,13 and provide a young adult comparison group for adolescents. Consistent with prior research,29 enrollees were defined as having received a diagnosis of OUD if a claim was filed with a primary or secondary International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) diagnosis code 304.0x (“Opioid type dependence”) or 304.7x (“Combinations of opioid type drug with any other drug dependence”) in ≥1 inpatient or emergency department claim or ≥2 outpatient claims. The date of OUD diagnosis was the date of the first qualifying claim.

Variables of Interest

Our primary outcome of interest was receipt of buprenorphine (formulated as buprenorphine or buprenorphine/naloxone) or naltrexone (in its oral short-acting or intramuscular extended-release formulation) within 6 months of the first observed OUD diagnosis. Although clinical practice guidelines recommend considering pharmacotherapy as soon as possible after OUD diagnosis,24,26 we examined a 6-month timeframe to allow for any delay in linking youth to treatment services. We identified pharmacy claims that included a National Drug Code for buprenorphine (excluding the transdermal buprenorphine patch marketed exclusively for pain control) or naltrexone (see Supplemental Table 1). Since intramuscular extended-release naltrexone is often administered in health care settings (rather than being prescribed), an individual was also considered to have received naltrexone if a claim contained Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System code J2315 (“Naltrexone, depot form”). Each individual was labeled with a unique identifier and was included in the analytic sample only once at the time of first observed diagnosis.

Covariates of interest included sex, age of OUD diagnosis, race/ethnicity, metropolitan area (i.e., metropolitan vs. non-metropolitan), neighborhood educational level, and neighborhood poverty level, using previously established cutoffs.30–32 To identify race/ethnicity, we used a combination of 2000 US Census32 neighborhood characteristics and surname analysis, a validated approach with high positive predictive value.33

Statistical Analyses

Using the entire sample of 13- to 25-year-olds with ≥6 months of continuous enrollment, we calculated annual diagnosis rates (i.e., number of first observed diagnoses of OUD in a year divided by total person-years contributed) according to age group (13–15 years, 16–17 years, 18–20 years, and 21–25 years).

For all subsequent analyses, we limited the sample to youth who had received an OUD diagnosis. We then identified the proportion of youth who received buprenorphine or naltrexone within 6 months of diagnosis. Among youth who received pharmacotherapy, we examined linear time trends in receipt of buprenorphine as compared to naltrexone, introducing splines with two knots defined a priori corresponding to the FDA approval of buprenorphine and buprenorphine/naltrexone in October 2002, and of intramuscular extended-release naltrexone in October 2010. We then identified differences between youth who received buprenorphine as compared to naltrexone. Where cell counts were <10, categories were excluded or collapsed together to protect confidentiality.

To compare characteristics of youth who did and did not receive pharmacotherapy, we used logistic regression to identify associations between study covariates and medication receipt. We subsequently generated a multivariable model including all study covariates given the known association of each covariate with access to addiction treatment;34–36 we additionally adjusted for year as an indicator variable to account for secular trends. Using this multivariable model and the margins command in Stata, we then calculated the adjusted probability of receiving pharmacotherapy.

To understand the effect of considering a different timeframe for receipt of pharmacotherapy after OUD diagnosis, we conducted sensitivity analyses in which the outcome of interest was receipt of a medication within 3 and 12 months (as compared to 6 months) of OUD diagnosis and requiring ≥3 and ≥12 months of continuous enrollment, respectively. We repeated the multivariable model for both timeframes. Analyses were conducted using Stata 13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Park, TX). All statistical tests were two-sided and considered significant at p<0.05.

RESULTS

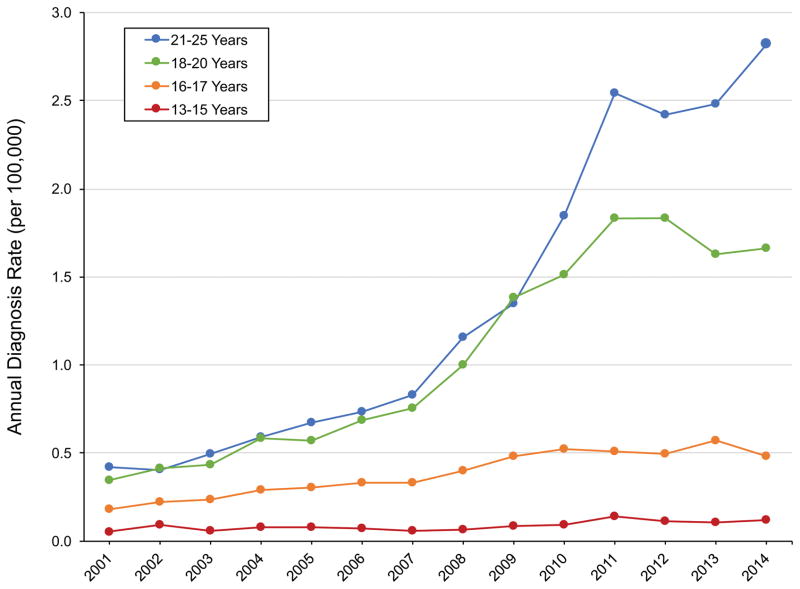

Between January 1, 2001 and June 30, 2014, there were 9,710,131 youth of age 13–25 years in the Optum data with ≥6 months of continuous enrollment, and of these youth, 20,822 (0.2%) met criteria for an OUD diagnosis. Median time observed prior to first OUD diagnosis was 20 months per individual (interquartile range [IQR], 7–45 months). Figure 1 shows the diagnosis rate by calendar year according to age. The overall diagnosis rate increased with each subsequent study year, rising nearly 6-fold from 0.26 per 100,000 person-years in 2001 to 1.51 per 100,000 person-years in 2014. This increase was driven primarily by increases in diagnoses among young adults ≥18 years, although diagnosis rates for all age categories increased over the study period.

Figure 1.

Trends in annual rate of new diagnoses of OUD among youth: Optum, January 1, 2001 to December 31, 2014 (n = 20,822).

Table 1 displays the characteristics of the sample. Among youth with OUD, 65.8% were male and mean age (SD) was 21.0 (2.5) years at the time of diagnosis; most youth with OUD came from a predominantly non-Hispanic white neighborhood (82.3%). Compared to the overall sample, youth with OUD were more likely to be male or from a non-Hispanic white neighborhood, metropolitan area, high education neighborhood, low poverty neighborhood, or the Northeast.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of overall sample of 9,710,131 youth of age 13–25 years according to diagnosis of opioid use disorder (OUD): Optum, January 1, 2001 to December 31, 2014.

| Characteristic | Youth without OUD (n = 9,689,309) Column % |

Youth with OUD (n = 20,822) Column % |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of diagnosis | |||

| 21–25 years | – | 53.1 | |

| 18–20 years | – | 34.5 | |

| 16–17 years | – | 9.2 | |

| 13–15 years | – | 3.2 | |

| Sex | <0.001 | ||

| Male | 49.8 | 65.8 | |

| Female | 50.2 | 34.2 | |

| Race/ethnicitya | <0.001 | ||

| White non-Hispanic | 68.2 | 82.3 | |

| Black non-Hispanic | 2.6 | 0.5 | |

| Hispanic | 10.1 | 5.6 | |

| Asian | 2.9 | 1.1 | |

| Mixed | 16.2 | 10.5 | |

| Metropolitan area | <0.001 | ||

| Metropolitan | 64.4 | 67.8 | |

| Non-metropolitan | 35.6 | 32.2 | |

| Neighborhood educational levelb | |||

| High | 58.5 | 67.4 | |

| High-middle | 21.9 | 19.9 | |

| Low-middle | 14.1 | 10.2 | |

| Low | 5.5 | 2.5 | |

| Neighborhood poverty levelc | <0.001 | ||

| Low | 44.1 | 54.1 | |

| Low-middle | 25.5 | 24.9 | |

| High-middle | 20.0 | 15.4 | |

| High | 10.4 | 5.6 | |

| Census region | <0.001 | ||

| South | 44.1 | 41.7 | |

| Midwest | 29.4 | 26.3 | |

| West | 16.4 | 17.4 | |

| Northeast | 10.1 | 14.6 |

Race/ethnicity data were derived from a combination of geocoded census-block group-level race from the 2000 US Census and surname analysis to identify Asian and Hispanic individuals; mixed neighborhoods are those that did not meet a 75% threshold for white, black, or Hispanic ethnicity33

Neighborhood educational level was based on geocoded census block group-level data from the 2000 US Census; High education level denotes neighborhoods with less than 15% of individuals with less than high school education; high-middle, 15% to 24.9%; low-middle, 25% to 39.9%; and low, 40% or more of individuals

Neighborhood poverty was based on geocoded census block group-level data from the 2000 US Census; Low denotes neighborhoods with less than 5% of individuals living below the poverty level; low-middle, 5% to 9.9%; high-middle, 10% to 19.9%; and high, 20% or more

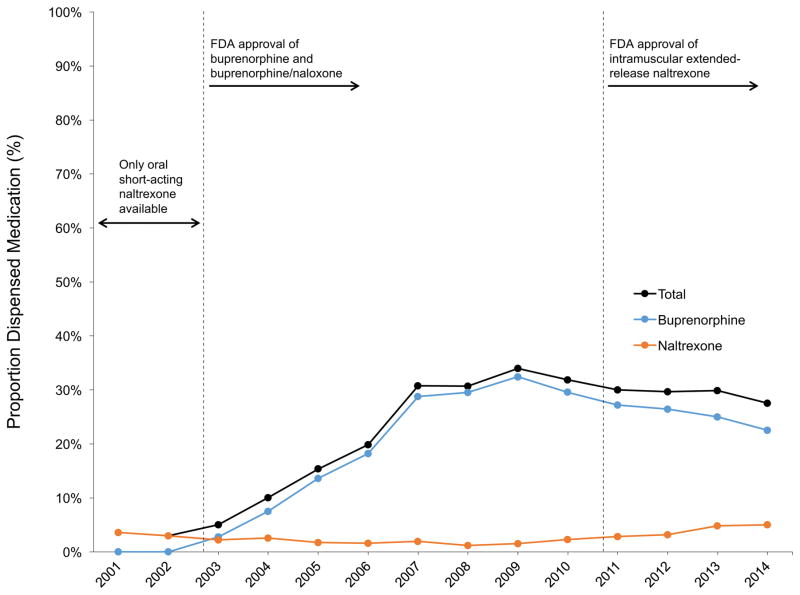

Overall, 5,580 (26.8%) youth with OUD received either buprenorphine or naltrexone within 6 months of their first observed diagnosis. Figure 2 shows the percentage of youth who received medications by year. Medication receipt increased more than 10-fold from 2002, the year with the lowest percentage of youth receiving pharmacotherapy (3.0%), to 2009, the year with the highest percentage (31.8%). For the most recent study year (2014), the percentage was 27.5%. Medication receipt increased overall during the study period (odds ratio [OR], 1.11 per year; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.10–1.12). In analyses handling year as a continuous predictor with splines corresponding to FDA approval of buprenorphine in 2002 and of intramuscular extended-release naltrexone in 2010, the odds of receiving buprenorphine relative to naltrexone increased from 2002 to 2010 (OR, 1.31 per year; 95% CI, 1.22–1.39), but then the odds of receiving naltrexone relative to buprenorphine increased from 2010 to 2014 (OR, 1.17 per year; 95% CI, 1.09–1.25).

Figure 2.

Trends in the proportion of youth dispensed buprenorphine or naltrexone within 6 months of opioid use disorder diagnosisa in relation to annual diagnosis rate and introduction of medications by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA): Optum, January 1, 2001 to December 31, 2014 (n = 20,822).

a. Youth prescribed both medications during the 6 months following OUD diagnosis are classified according to the first medication they received.

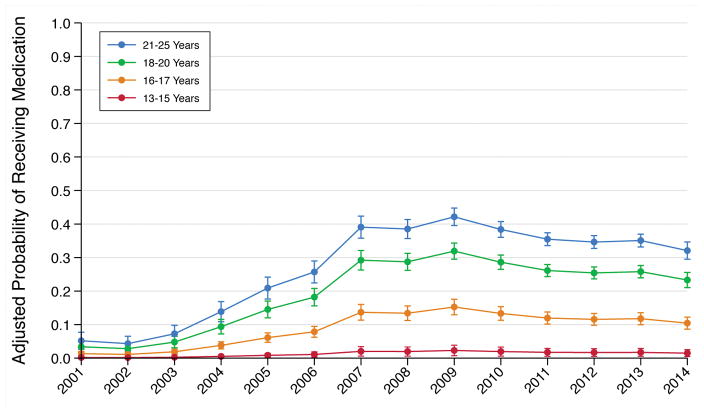

Table 2 displays the percentage of youth who received a medication according to sociodemographic characteristics. In the multivariable model, factors significantly associated with decreased odds of medication receipt included younger age, female sex, black non-Hispanic race or Hispanic ethnicity, and low-middle neighborhood poverty level. Figure 3 shows time trends in the adjusted probability of receiving a medication according to age group. Increases were greatest between 2003 and 2007, with larger increases observed among older youth compared to younger individuals.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic characteristics of 20,822 youth with opioid use disorder and odds ratios (OR) for receipt of a medication (buprenorphine or naltrexone) within 6 months of diagnosis: Optum, January 1, 2001 to December 31, 2014.

| Characteristica | Received Medication (n = 5,580),% | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjustedb Probability of Receiving Medication, % (95% CI) | Adjustedb OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of diagnosis | ||||

| 21–25 years (n = 11,050) | 33.0 | Reference | 30.5 (30.0 – 31.5) | Reference |

| 18–20 years (n = 7,186) | 24.0 | 0.64 (0.60 – 0.69) | 22.0 (21.0 – 23.0) | 0.64 (0.60 – 0.69) |

| 16–17 years (n = 1,925) | 10.0 | 0.23 (0.19 – 0.26) | 9.7 (8.4 – 11.1) | 0.25 (0.21 – 0.29) |

| 13–15 years (n = 661) | 1.5 | 0.03 (0.02 – 0.06) | 1.4 (0.4 – 2.3) | 0.03 (0.02 – 0.06) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male (n = 13,698) | 28.7 | Reference | 24.4 (23.5 – 25.3) | Reference |

| Female (n = 7,124) | 23.1 | 0.75 (0.70 – 0.80) | 20.3 (19.2 – 21.3) | 0.79 (0.73 – 0.84) |

| Race/ethnicityc | ||||

| White non-Hispanic (n = 17,119) | 27.1 | Reference | 23.1 (22.3 – 23.9) | Reference |

| Black non-Hispanic (n = 105) | 18.1 | 0.59 (0.36 – 0.98) | 14.8 (7.9 – 21.7) | 0.58 (0.33 – 0.99) |

| Hispanic (n = 1,165) | 23.4 | 0.82 (0.71 – 0.94) | 20.0 (17.6 – 22.3) | 0.83 (0.71 – 0.97) |

| Asian (n = 224) | 24.5 | 0.87 (0.64 – 1.19) | 19.6 (14.5 – 24.6) | 0.81 (0.59 – 1.12) |

| Mixed (n = 2,175) | 26.8 | 0.98 (0.89 – 1.09) | 23.9 (21.9 – 25.9) | 1.05 (0.93 – 1.17) |

| Metropolitan area | ||||

| Metropolitan (n = 13,651) | 26.5 | Reference | 22.9 (22.1 – 23.8) | Reference |

| Non-metropolitan (n = 6,473) | 27.2 | 1.04 (0.97 – 1.11) | 22.9 (21.8 – 24.1) | 1.00 (0.93 – 1.07) |

| Neighborhood educational leveld | ||||

| High (n = 14,023) | 26.8 | Reference | 22.7 (21.9 – 23.6) | Reference |

| High-middle (n = 4,148) | 27.6 | 1.04 (0.96 – 1.12) | 23.7 (22.3 – 25.2) | 1.06 (0.97 – 1.15) |

| Low-middle (n = 2,113) | 25.7 | 0.94 (0.85 – 1.05) | 23.1 (21.0 – 25.2) | 1.02 (0.90 – 1.16) |

| Low (n = 518) | 23.4 | 0.83 (0.68 – 1.02) | 20.7 (16.7 – 24.7) | 0.89 (0.69 – 1.14) |

| Neighborhood poverty levele | ||||

| Low (n = 11,225) | 27.6 | Reference | 23.7 (22.7 – 24.7) | Reference |

| Low-middle (n = 5,179) | 25.8 | 0.91 (0.85 – 0.98) | 21.9 (20.6 – 23.1) | 0.90 (0.83 – 0.98) |

| High-middle (n = 3,211) | 25.7 | 0.91 (0.83 – 0.99) | 22.0 (20.3 – 23.6) | 0.91 (0.81 – 1.01) |

| High (n = 1,157) | 26.5 | 0.95 (0.83 – 1.09) | 22.9 (19.9 – 25.9) | 0.96 (0.80 – 1.14) |

| Census region | ||||

| South (n = 8,688) | 27.0 | Reference | 22.8 (21.7 – 23.8) | Reference |

| Midwest (n = 5,469) | 26.8 | 0.99 (0.92 – 1.07) | 23.9 (22.6 – 25.1) | 1.06 (0.98 – 1.15) |

| West (n = 3,618) | 26.8 | 1.01 (0.92 – 1.10) | 22.9 (21.4 – 24.4) | 1.01 (0.91 – 1.11) |

| Northeast (n = 3,044) | 25.9 | 0.95 (0.86 – 1.04) | 21.9 (20.3 – 23.4) | 0.95 (0.86 – 1.05) |

Where counts do not add to total, data are missing

Adjusted for all other covariates listed in the table in addition to year that an individual was diagnosed with opioid use disorder (coded as an indicator variable)

Race/ethnicity data were derived from a combination of geocoded census-block group-level race from the 2000 US Census and surname analysis to identify Asian and Hispanic individuals; mixed neighborhoods are those that did not meet a 75% threshold for white, black, or Hispanic ethnicity

Neighborhood educational level was based on geocoded census block group-level data from the 2000 US Census; High education level denotes neighborhoods with less than 15% of individuals with less than high school education; high-middle, 15% to 24.9%; low-middle, 25% to 39.9%; and low, 40% or more of individuals33

Neighborhood poverty was based on geocoded census block group-level data from the 2000 US Census; Low denotes neighborhoods with less than 5% of individuals living below the poverty level; low-middle, 5% to 9.9%; high-middle, 10% to 19.9%; and high, 20% or more

Figure 3.

Proportion of youth with a claim containing an opioid use disorder diagnosis who were dispensed any medication (buprenorphine or naltrexone) according to age at first diagnosisa: Optum, January 1, 2001 to December 31, 2014 (n = 20,822).

a. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals for the estimate.

Table 3 compares characteristics of youth who received buprenorphine as compared to naltrexone. Youth were less likely to receive buprenorphine than naltrexone if they were younger or female. They were more likely to receive buprenorphine if they were from a non-metropolitan area; low-middle or low education neighborhood; low-middle, high-middle, or high poverty neighborhood; or from the Midwest.

Table 3.

Unadjusted odds ratios (OR) for receipt of buprenorphine relative to naltrexone among 5,580 youth with OUD who received a medication: Optum, January 1, 2001 to December 31, 2014.

| Characteristica | Received Buprenorphineb (n = 4,976), % | Received Naltrexoneb (n = 604), % | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of diagnosisc | |||

| 21–25 years (n = 3,650) | 90.3 | 9.7 | Reference |

| 18–20 years (n = 1,727) | 87.9 | 12.1 | 0.78 (0.65 – 0.94) |

| 16–17 years (n = 193) | 81.4 | 18.7 | 0.47 (0.32 – 0.68) |

| Sex | |||

| Male (n = 3,931) | 89.7 | 10.3 | Reference |

| Female (n = 1,649) | 87.8 | 12.2 | 0.82 (0.69 – 0.99) |

| Race/ethnicityd | |||

| White non-Hispanic (n = 4,644) | 89.1 | 10.9 | Reference |

| Other (n = 936) | 89.4 | 10.5 | 1.03 (0.82 – 1.30) |

| Metropolitan area | |||

| Metropolitan (n = 3,623) | 88.0 | 12.0 | Reference |

| Non-metropolitan (n = 1,764) | 91.4 | 8.6 | 1.44 (1.19 – 1.75) |

| Neighborhood educational levele | |||

| High (n = 3,764) | 88.3 | 11.7 | Reference |

| High-middle (n = 1,146) | 89.7 | 10.3 | 1.15 (0.93 – 1.43) |

| Low-middle/Low (n = 664) | 93.1 | 6.9 | 1.77 (1.29 – 2.43) |

| Neighborhood poverty levelf | |||

| Low (n = 3,106) | 87.7 | 12.3 | Reference |

| Low-middle (n = 1,335) | 89.9 | 10.1 | 1.25 (1.01 – 1.53) |

| High-middle (n = 827) | 92.3 | 7.7 | 1.67 (1.27 – 2.20) |

| High (n = 307) | 92.8 | 7.2 | 1.82 (1.16 – 2.84) |

| Census region | |||

| South (n = 2,342) | 88.6 | 11.4 | Reference |

| Midwest (n = 1,468) | 91.0 | 9.0 | 1.30 (1.04 – 1.62) |

| West (n = 981) | 88.4 | 11.6 | 0.97 (0.77 – 1.23) |

| Northeast (n = 789) | 88.3 | 11.7 | 0.97 (0.75 – 1.25) |

Where counts do not add to total, data are missing

Buprenorphine includes formulations of buprenorphine or buprenorphine/naloxone, and naltrexone includes both oral short-acting naltrexone and intramuscular extended-release naltrexone; if a participant received both medications within 6 months of their first OUD diagnosis, they are classified according to the first medication they received

13- to 15-year-olds excluded due to low cell counts

Race/ethnicity data collapsed due to low cell counts; derived from a combination of geocoded census-block group-level race from the 2000 US Census and surname analysis to identify Asian and Hispanic individuals; mixed neighborhoods are those that did not meet a 75% threshold for white, black, or Hispanic ethnicity33

Low-middle/Low categories combined due to low cell counts; neighborhood educational level was based on geocoded census block group-level data from the 2000 US Census; High education level denotes neighborhoods with less than 15% of individuals with less than high school education; high-middle, 15% to 24.9%; low-middle, 25% to 39.9%; and low, 40% or more of individuals

Neighborhood poverty was based on geocoded census block group-level data from the 2000 US Census; Low denotes neighborhoods with less than 5% of individuals living below the poverty level; low-middle, 5% to 9.9%; high-middle, 10% to 19.9%; and high, 20% or more

Sensitivity analyses examining medication receipt within 3 and 12 months are shown in Supplemental Tables 2 and 3, respectively. Although effect sizes across age, sex, and race/ethnicity strata using 3- and 12-month timeframes were similar to those for a 6-month timeframe, AORs were not significant for non-Hispanic black youth using a 3-month timeframe, or for non-Hispanic black youth and Hispanic youth using a 12-month timeframe.

DISCUSSION

In this large national study of buprenorphine and naltrexone dispensing among commercially insured youth with OUD, we found that only 1 in 4 youth received pharmacotherapy within 6 months of diagnosis during the 2001–2014 study period. From 2002 (when buprenorphine was introduced) to 2009, the percentage of youth receiving medication increased more than 10-fold but subsequently declined amidst escalating OUD diagnosis rates. Odds of receiving pharmacotherapy were lower with younger age, and were lower among females relative to males, and black and Hispanic youth relative to white youth. Overall, buprenorphine was dispensed 8 times more often than naltrexone. Naltrexone was more commonly dispensed to younger individuals and females, and to youth in metropolitan areas, higher education neighborhoods, and lower poverty neighborhoods.

Only a minority of youth with OUD received pharmacotherapy, thus revealing a potentially critical treatment gap. This finding reconfirms the 2016 Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health, which highlighted the large number of youth with untreated addiction,28 and also supports the recent policy statement from the AAP calling for expanded access to medications for youth with OUD.26 Notably, we observed a decrease in the percentage of youth receiving pharmacotherapy from 2009 onwards after a preceding rise. This decrease occurred amidst an escalating OUD diagnosis rate, as well as an increasing number of young adults nationwide receiving health insurance under an Affordable Care Act provision allowing coverage under a parent’s plan.37 Both of these forces likely resulted in an expansion in the number of youth in OUD care, which may not have been accompanied by improved access to medications. National data preceding the Affordable Care Act suggest that youth with commercial insurance are less likely to receive addiction treatment (with or without pharmacotherapy) than youth with public insurance.38 In the face of changing national health insurance policies, further studies are urgently needed to understand differences in diagnosis and treatment between commercially and publicly insured youth with OUD.

We found that adolescents <16 years were least likely to receive medications, a finding likely reflecting that buprenorphine, the most common medication dispensed, is only FDA-approved for individuals ≥16 years.17,21,22 We also observed only a small number of adolescents receiving naltrexone, even after the introduction of its long-acting injectable formulation in 2010. Although trials comparing the efficacy of buprenorphine and naltrexone are pending,39 our results suggest that buprenorphine is much more commonly used and further studies should characterize patient, caregiver and provider preferences regarding these medications in addition to treatment outcomes.

Even despite the demonstrated efficacy and FDA approval of buprenorphine for adolescents ≥16 years,17,20,21 we found that 16- and 17-year-olds were less likely than young adults ≥18 years to receive pharmacotherapy. It is well established that adolescents experience difficulty accessing addiction treatment.26,28 Availability of services for adolescents is limited; fewer than 1 in 3 specialty drug treatment programs in the US offers care to adolescents.40 Nationwide, there is a shortage of physicians with a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine outside metropolitan areas and compounding this, pediatricians who prescribe buprenorphine are exceedingly rare.34,41 Nonetheless, we did not observe lower odds of receiving medication outside metropolitan areas.23 In one recent national study, access to buprenorphine significantly improved in rural areas from 2002 to 2011.41 Our results build on these prior findings by highlighting that even though access to medications may be improving in many locations, use of pharmacotherapy among youth remains low overall. Ensuring access to medications among youth should remain a critical focus in order to ensure timely and equitable care regardless of location.

Our results suggest that the treatment gap for youth is greater for black and Hispanic youth as well as for females. Underlying reasons are unclear, and may relate to access to care, denial of care, or provider bias.15,16 Prior studies have shown that poorer access to substance use treatment among minorities is in part explained by disparities in health insurance coverage.35,42 However, our results indicate that even with coverage, black and Hispanic youth are less likely than white youth to receive medications for OUD. Data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health highlight that although receipt of past-year treatment between 2001 and 2008 among white adolescents with any type of substance use disorder was low (10.7%), it was significantly lower for black (6.9%) and Hispanic adolescents (8.5%).15 Even once in treatment, only half of black and Hispanic adolescents complete treatment, a significantly lower proportion than white adolescents.16 Similarly, data suggest females may experience greater barriers to addiction treatment and demonstrate poorer outcomes relative to males.43 It is critical that clinicians and policymakers working to expand access to pharmacotherapy for youth ensure services are disseminated in a way that addresses, rather than worsens, racial/ethnic and sex disparities.

Since the majority of youth with OUD do not receive medications in a timely manner, strategies to improve access to evidence-based treatment for adolescents are urgently needed. One strategy is to increase the number of pediatric addiction subspecialists.44 With the recent recognition of Addiction Medicine by the American Board of Medical Specialties, pediatricians and family physicians have new opportunities to pursue board certification and are well-poised to disseminate developmentally appropriate services for youth.45 However, since there are unlikely to be sufficient pediatric addiction subspecialists to address the large number of youth with OUD, an additional strategy is to implement pharmacotherapy in pediatric primary care.26,45 This approach is increasingly used to treat adults with OUD,46,47 and is recommended by the AAP.26

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, we could not assess the severity of individuals’ addiction. It is possible that older youth or other demographic groups had more severe OUD for which pharmacotherapy was more strongly indicated. Second, our approach likely underestimated the number of youth with OUD since we relied on billing diagnoses. The actual proportion of youth with OUD who receive pharmacotherapy may be even lower than reported here because many youth go undiagnosed or clinicians may be reluctant to code this sensitive diagnosis.48 Third, we were unable to assess receipt of methadone. Since provision of methadone to adolescents <18 years is highly restricted,49 we do not anticipate that many underage youth received methadone; some youth ≥18 years may have received methadone from publicly funded programs.16,50 Fourth, our sample included only commercially insured youth, and thus generalizability to populations without private health insurance is unclear. Recent data suggest that adults without health insurance are unlikely to receive pharmacotherapy for OUD, whereas adults with public health insurance may be as likely to receive pharmacotherapy as those with private insurance.51

CONCLUSIONS

We observed improvements in the percentage of youth receiving pharmacotherapy for OUD between 2001 and 2014, but noted an apparent decrease after 2009 amidst an escalating diagnosis rate and despite the FDA approval of long-acting injectable naltrexone in 2010. There remains substantial room for improvement in the provision of pharmacotherapy to youth with OUD. Both the AAP and the 2016 Surgeon General’s Report highlight that intervention early in the life course of youth addiction is critical for preventing progression to more severe disease,26,28 yet our data indicate that medications are underutilized for youth. Adolescents might especially be underserved in the current treatment environment, and females, as well as black and Hispanic youth appear less likely than their age-matched peers to receive medications. In the face of a worsening opioid crisis in the US, strategies to expand use of pharmacotherapy for adolescents and young adults are greatly needed, and special care is warranted to ensure equitable access for all affected youth to avoid exacerbating health disparities.

Supplementary Material

KEY POINTS.

Question

How often do youth with opioid use disorder receive buprenorphine or naltrexone, and how has this changed over time?

Findings

In this large national retrospective cohort of 20,822 youth of age 13–25 years with opioid use disorder, medication receipt increased from 2001 to 2014, but only 1 in 4 received buprenorphine or naltrexone. Younger individuals, females, and black and Hispanic youth were less likely to receive a medication.

Meaning

Amidst emerging recommendations calling for expanded access to pharmacotherapy for youth with opioid use disorder, medications may have been historically underutilized and disparities may exist by age, sex, and race/ethnicity.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms. Meg Powers and Mr. Matt Callahan for their contributions, as well as Dr. Jason Vassy for his review of the manuscript.

Role of Funding Source

Dr. Hadland was supported by the Loan Repayment Program Award L40 DA042434 (NIH/NIDA), the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine Substance Abuse Trainee Award (NIH/NIDA), and a National Research Service Award 1T32 HD075727 (NIH/NICHD). Drs. Wharam and Zhang were supported by Harvard Medical School/Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute Faculty Grant 405625-1.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributors

Drs. Hadland, Wharam, Schuster, and LaRochelle designed the study and wrote the protocol for analysis with additional input from Drs. Zhang and Samet. Dr. Zhang undertook data management and Dr. Hadland conducted statistical analyses with input from Drs. Wharam, Zang, and LaRochelle. Dr. Hadland conducted the literature review and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Warner M, Hedegaard H, Chen LH. Trends in Drug-Poisoning Deaths: United States, 1999–2012. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Health Statistics; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen LH, Hedegaard H, Warner M. Drug-poisoning Deaths Involving Opioid Analgesics: United States, 1999–2011. NCHS Data Brief. 2014;(166):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones CM, Mack KA, Paulozzi LJ. Pharmaceutical overdose deaths, United States, 2010. JAMA. 2013;309(7):657–659. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dart RC, Surratt HL, Cicero TJ, et al. Trends in opioid analgesic abuse and mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(3):241–248. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1406143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, Gladden RM. Increases in Drug and Opioid Overdose Deaths--United States, 2000–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;64(50–51):1378–1382. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6450a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, Gladden RM. Increases in Drug and Opioid Overdose Deaths - United States, 2000–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;64(50–51):1378–1382. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6450a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaither JR, Leventhal JM, Ryan SA, Camenga DR. National trends in hospitalizations for opioid poisonings among children and adolescents, 1997 to 2012. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(12):1195–1201. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. The DAWN Report: Highlights of the 2011 Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) Findings on Drug-Related Emergency Department Visits. Rockville, MD: 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS): 2003–2013. National Admissions to Substance Abuse Treatment Services. Rockville, MD: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zibbell JE, Iqbal K, Patel RC, et al. Increases in hepatitis C virus infection related to injection drug use among persons aged ≤30 years - Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia, 2006–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(17):453–458. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Miech RA, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2016: Overview, Key Findings on Adolescent Drug Use. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Committee on Substance Use and Prevention. Substance Use Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment. Pediatrics. 2016;138(1):e20161211–e20161211. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Among Youth. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han B, Hedden SL, Lipari R, Copello EAP, Kroutil LA. Receipt of Services for Behavioral Health Problems: Results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cummings JR, Wen H, Ko M, Druss BG. Race/ethnicity and geographic access to medicaid substance use disorder treatment facilities in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(2):190–196. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.3575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saloner B, Stoller KB, Barry CL. Medicaid Coverage for Methadone Maintenance and Use of Opioid Agonist Therapy in Specialty Addiction Treatment. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(6):676–679. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201500228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marsch LA, Bickel WK, Badger GJ, et al. Comparison of pharmacological treatments for opioid-dependent adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(10):1157–1164. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fudala PJ, Bridge TP, Herbert S, et al. Office-based treatment of opiate addiction with a sublingual-tablet formulation of buprenorphine and naloxone. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(10):949–958. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krupitsky E, Nunes EV, Ling W, Illeperuma A, Gastfriend DR, Silverman BL. Injectable extended-release naltrexone for opioid dependence: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9776):1506–1513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60358-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marsch LA, Moore SK, Borodovsky JT, et al. A randomized controlled trial of buprenorphine taper duration among opioid-dependent adolescents and young adults. Addiction. 2016;111(8):1406–1415. doi: 10.1111/add.13363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woody GE, Poole SA, Subramaniam G, et al. Extended vs short-term buprenorphine-naloxone for treatment of opioid-addicted youth: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2008;300(17):2003–2011. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kampman K, Jarvis M. American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) National Practice Guideline for the Use of Medications in the Treatment of Addiction Involving Opioid Use. J Addict Med. 2015;9(5):358–367. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenblatt RA, Andrilla CHA, Catlin M, Larson EH. Geographic and Specialty Distribution of US Physicians Trained to Treat Opioid Use Disorder. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(1):23–26. doi: 10.1370/afm.1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Guidelines for the Use of Buprenorphine in the Treatment of Opioid Addiction. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 40. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Expenditures for Mental Health Services and Substance Abuse Treatment 1986–2009. HHS Publication No. SMA-13-4740. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Committee on Substance Use and Prevention. Medication-assisted treatment of adolescents with opioid use disorders. Pediatrics. 2016;138(3):e20161893. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Office of National Drug Control Policy. 2015 National Drug Control Strategy. Washington, DC: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of the Surgeon General. Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. Washington, DC: 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stein BD, Gordon AJ, Sorbero M, Dick AW, Schuster J, Farmer C. The impact of buprenorphine on treatment of opioid dependence in a Medicaid population: recent service utilization trends in the use of buprenorphine and methadone. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;123(1–3):72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Rehkopf DH, Subramanian SV. Race/ethnicity, gender, and monitoring socioeconomic gradients in health: a comparison of area-based socioeconomic measures--the public health disparities geocoding project. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(10):1655–1671. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.10.1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.U.S. Census Bureau. Geographic Areas Reference Manual. Washington, DC, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 32.U.S. Census Bureau. 2000 Census of Population and Housing. Washington, DC: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fiscella K, Fremont AM. Use of geocoding and surname analysis to estimate race and ethnicity. Health Serv Res. 2006;41(4 Pt 1):1482–1500. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00551.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stein BD, Pacula RL, Gordon AJ, et al. Where Is duprenorphine dispensed to treat opioid use disorders? The role of private offices, opioid treatment programs, and substance abuse treatment facilities in urban and rural counties. Milbank Q. 2015;93(3):561–583. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saloner B, Carson N, Lê Cook B. Explaining racial/ethnic differences in adolescent substance abuse treatment completion in the United States: a decomposition analysis. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54(6):646–653. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cook BL, Alegría M. Racial-ethnic disparities in substance abuse treatment: the role of criminal history and socioeconomic status. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(11):1273–1281. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.11.pss6211_1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sommers BD, Kronick R. The Affordable Care Act and insurance coverage for young adults. JAMA. 2012;307(9):913–914. doi: 10.1001/jama.307.9.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Winstanley EL, Steinwachs DM, Stitzer ML, Fishman MJ. Adolescent Substance Abuse and Mental Health: Problem Co-Occurrence and Access to Services. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2012;21(4):310–322. doi: 10.1080/1067828X.2012.709453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee JD, Nunes EV, Mpa PN, et al. NIDA Clinical Trials Network CTN-0051, Extended-Release Naltrexone vs. Buprenorphine for Opioid Treatment (X:BOT): Study design and rationale. Contemp Clin Trials. 2016;50:253–264. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mericle AA, Arria AM, Meyers K, Cacciola J, Winters KC, Kirby K. National trends in adolescent substance use disorders and treatment availability: 2003–2010. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2015;24(5):255–263. doi: 10.1080/1067828X.2013.829008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dick AW, Pacula RL, Gordon AJ, et al. Growth In buprenorphine waivers for physicians increased potential access to opioid agonist treatment, 2002–11. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34(6):1028–1034. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alegria M, Carson NJ, Goncalves M, Keefe K. Disparities in treatment for substance use disorders and co-occurring disorders for ethnic/racial minority youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50(1):22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tuchman E. Women and Addiction: The Importance of Gender Issues in Substance Abuse Research. J Addict Dis. 2010;29(2):127–138. doi: 10.1080/10550881003684582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wood E, Samet JH, Volkow ND. Physician education in addiction medicine. JAMA. 2013;310(16):1673–1674. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.280377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hadland SE, Wood E, Levy S. How the paediatric workforce can address the opioid crisis. Lancet. 2016;388(10051):1260–1261. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31573-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alford DP, LaBelle CT, Kretsch N, et al. Collaborative care of opioid-addicted patients in primary care using buprenorphine: five-year experience. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(5):425–431. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.LaBelle CT, Han SC, Bergeron A, Samet JH. Office-based opioid treatment with buprenorphine (OBOT-B): Statewide implementation of the Massachusetts collaborative care model in community health centers. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;60:6–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2015.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Levy SJ, Kokotailo PK. Substance use screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment for pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):e1330–40. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jaffe JH, O’Keeffe C. From morphine clinics to buprenorphine: regulating opioid agonist treatment of addiction in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;70(2):S3–S11. doi: 10.1016/S0376-8716(03)00055-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jones CM, Campopiano M, Baldwin G, McCance-Katz E. National and state treatment need and capacity for opioid agonist medication-assisted treatment. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(8):e55–63. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Abraham AJ, Rieckmann T, Andrews CM, Jayawardhana J. Health insurance enrollment and availability of medications for substance use disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2016 Aug; doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201500470. appips201500470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.