Abstract

Baseline hematocrit fraction (Hct) is a determinant for baseline cerebral blood flow (CBF) and between-subject variation of Hct thus causes variation in task-based BOLD fMRI signal changes. We first verified in healthy volunteers (n = 12) that Hct values can be derived reliably from venous blood T1 values by comparison with the conventional lab test. Together with CBF measured using phase contrast MRI, this noninvasive estimation of Hct, instead of using a population-averaged Hct value, enabled more individual determination of oxygen delivery (DO2), oxygen extraction fraction (OEF), and cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen (CMRO2). The inverse correlation of CBF and Hct explained about 80% of between-subject variation of CBF in this relatively uniform cohort of subjects, as expected based on the regulation of DO2 to maintain constant CMRO2. Furthermore, we compared the relationships of visual task-evoked BOLD response with Hct and CBF. We showed that Hct and CBF contributed 22–33% of variance in BOLD signal and removing the positive correlation with Hct and negative correlation with CBF allowed normalization of BOLD signal with 16–22% lower variability. The results of this study suggests that adjustment for Hct effects is useful for studies of MRI perfusion and BOLD fMRI.

Keywords: MRI, Hct, CBF, DO2, OEF, CMRO2, BOLD

Introduction

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) allows quantification of several baseline cerebral physiological parameters as well as the investigation of brain functional activity using blood-oxygenation-level-dependent (BOLD) signal changes. Understanding the physiological sources of between-subject variability is critical for the interpretation of these measures, especially for studies employing group comparison between healthy subjects and populations with various neurological or pathological conditions.

The hematocrit or proportion of whole blood that is red blood cells (Hct) governs an individual’s oxygen (O2) carrying capacity and together with arterial oxygenation fraction (Ya) and cerebral blood flow (CBF), determines the oxygen delivery (DO2) to tissue.

| [1] |

in which [Hbtot] is the total hemoglobin concentration in mM and [Hbtot] ∙ Ya is the arterial oxygen content in µmol/mL. This can be determined from erythrocyte hemoglobin content, Cery, which is the amount of the Hb monomer in a unit volume of fully oxygenated red blood cells. When taking a standardized mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration or MCHC of 33.86 g/dL and a molecular mass of 16,125 g/mol for the monomer, Cery equals 21.00 µmol Hb/mL or 21.00 µmol O2/mL blood cells (Chanarin, et al., 1984). The oxygen concentration in arterial blood can then be obtained by multiplying Cery with the Hct and Ya.

Baseline activity of neuronal and glial cells is proportional to the cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen (CMRO2). Due to the requirement of a constant oxygen delivery to maintain a constant CMRO2, any reduction in Hct leads to an increase in CBF and vice versa. This relationship has been well-confirmed with positron emission tomography (PET) and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), where this inverse correlation between Hct and cerebral blood flow (CBF) has been repeatedly observed, either by comparing between normal controls and patients with anemia or polycythemia (Brown, et al., 1985; Henriksen, et al., 2013; Herold, et al., 1986; Ibaraki, et al., 2010; Kuwabara, et al., 2002; Prohovnik, et al., 2009; Prohovnik, et al., 1989), or by examining within subjects before and after blood transfusion or hemodilution (Hino, et al., 1992; Hudak, et al., 1986; Massik, et al., 1987; Metry, et al., 1999; Vorstrup, et al., 1992). The requirement to maintain constant CMRO2 through regulated DO2 is described by the oxygen extraction fraction (OEF):

| [2] |

which is constant in healthy volunteers and generally stated in terms of a coupling between CMRO2 and CBF. OEF was reported to show less variations than CBF among anemic patients with sickle cell disease (Herold, et al., 1986) or chronic renal failure (Kuwabara, et al., 2002; Metry, et al., 1999).

In the MRI field, absolute CBF measurements using arterial spin labeling (ASL) techniques (Dai, et al., 2008; Detre, et al., 1992; Wong, et al., 1998) are being standardized (Alsop, et al., 2015). Methods for OEF estimation have been introduced based on MR susceptometry (Fan, et al., 2014; Fernandez-Seara, et al., 2006; Haacke, et al., 1997; Zhang, et al., 2015) and T2 relaxometry (Lu and Ge, 2008; Oja, et al., 1999; Qin, et al., 2011a; Wright, et al., 1991). Whole-brain CMRO2 quantification by combining obtained CBF and OEF values has been done (Jain, et al., 2010; Xu, et al., 2009; Zhang, et al., 2015). Measurement of individual Hct values should allow more accurate estimation of DO2 and CMRO2. Furthermore, knowledge of Hct can help improve determination of OEF when using Hct-dependent susceptibility (Fan, et al., 2014; Fernandez-Seara, et al., 2006; Zhang, et al., 2015) or T2─Yv calibration curves (Lu, et al., 2012; Qin, et al., 2011a).

The blood-oxygenation-level-dependent (BOLD) functional MRI (fMRI) signal reflects changes in cerebral blood volume (CBV), CBF and CMRO2 through complex biophysical mechanisms (Blockley, et al., 2013; Hua, et al., 2011; Kim and Ogawa, 2012; van Zijl, et al., 2012; van Zijl, et al., 1998). The main cause of the effect is a temporary uncoupling of CBF and CMRO2 (Blockley, et al., 2013; Hua, et al., 2011; Kim and Ogawa, 2012; van Zijl, et al., 2012; van Zijl, et al., 1998). Positive correlation between Hct and BOLD amplitude have been observed in hemodilution experiments on anesthetized rats (Lin, et al., 1998a; Lin, et al., 1998b) as well as in task-based fMRI studies on both healthy subjects (Gustard, et al., 2003; Levin, et al., 2001) and children with sickle cell anemia (Zou, et al., 2011). This is easy to understand, because increased Hct causes a lower baseline CBF and thus a proportionally larger increase in BOLD signal change. Part of the inter-individual variability of BOLD signal changes may therefore be due to between-subject variation of Hct. As such, incorporation of Hct measurement in MRI perfusion or functional protocols would allow adjustment for this global baseline factor. However, the conventional measure of Hct through laboratory analysis of a venous blood sample requires venipuncture, which may be painful and/or inconvenient for subjects in a research study.

Fortunately, the longitudinal relaxation time (T1) of blood has a clear dependence on Hct, which is larger than on oxygenation (Brooks and Dichiro, 1987; Bryant, et al., 1990; Grgac, et al., 2013; Li, et al., 2016a; Lu, et al., 2004; Silvennoinen, et al., 2003). Since blood T1 values are important for MRI-based CBF quantification, fast MR sequences have been developed to obtain venous T1 from large cerebral veins (Qin, et al., 2011b; Varela, et al., 2011; Wu, et al., 2010). Recently, we validated this technique with in vitro measurements and confirmed that blood T1 values closely correlated with individual Hct (Li, et al., 2016b). The aim of this study is to demonstrate and verify that the Hct values converted from blood T1 per subject can help improve MRI-based measurements of baseline DO2, OEF, and CMRO2, and account for the differences of CBF as well as BOLD effect among normal volunteers.

Methods

All MR experiments were conducted on a 3.0 Tesla MR System (Philips Healthcare, Best, The Netherlands) using a body coil for radiofrequency transmission and a 32-channel head coil for reception. Foam padding was used to stabilize the participant’s head to minimize motion. A total of 13 healthy adults (35 ± 7 years old, 6 females and 7 males) were enrolled in this study and blood was sampled intravenously for complete blood count (CBC) immediately before or after the MRI scans. Each participant provided written informed consent and the study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board.

MRI Experiments

The experiments and participants analyzed here were reported in a recent paper for measurement of arterial and venous blood T1 values (Li, et al., 2016b); additional scans for venous blood T2, global flow rates of the brain, and BOLD fMRI are reported in the current study.

The protocols for obtaining arterial and venous blood T1 values at ICA and IJV respectively have been described previously (Li, et al., 2016b). Acquiring the arterial T1 from ICA requires extra repositioning of the subjects to have their chest covered by the body coil for complete inversion of the inflowing arterial blood (Li, et al., 2016b). Conversely, venous blood T1 can be measured under the neuroimaging setup (centering at eye level). Thus despite having an additional influence from oxygenation, obtaining venous blood T1 is more straightforward for brain function studies. As an improvement to our earlier protocol for venous T1 measurement at the IJV (Qin, et al., 2011b), we replaced the segmented echo-planar imaging (EPI) acquisition with segmented turbo field echo (TFE) readout for better flow compensation (Li, et al., 2016b). The total acquisition time was 1 min.

To visualize the major neck vessels (ICA: internal carotid artery; VA: vertebral artery; IJV: internal jugular vein), a quick time-of-flight (TOF) angiogram was employed with parameters: TR / TE / flip angle (FA) = 26 ms / 5.8 ms / 20°, field of view (FOV) = 201 × 201 × 80 mm3, nominal voxel size = 0.8 × 1.0 × 2.0 mm3. A 60-mm saturation slab was positioned above the imaging slab to suppress the venous blood.

In order to acquire baseline whole-brain CBF, the blood flow rates at the bilateral ICA and VA were measured using phase-contrast (PC) MR angiography (MRA). PC MRA has been validated for quantitative flow measurements (Bakker, et al., 1999; Evans, et al., 1993; Zananiri, et al., 1991). Four runs of PC MRA were planned using a plane orientation perpendicular to the corresponding arteries as described previously (Liu, et al., 2013b): nominal voxel size = 0.5 × 0.5 × 5 mm3, FOV = 200 × 200 × 5 mm3, TR / TE / FA = 19 ms / 9 ms /15°, maximum velocity encoding = 60 cm/s and 40 cm/s for ICA and VA respectively, without cardiac triggering. Scan duration of each PC MRI scan was 20 sec.

Additionally, a T1-weighted magnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo (MPRAGE) scan was added for brain volume estimation: TR / TE / FA = 12 ms / 3.2 ms / 9°, TI = 1110 ms, FOV = 220 × 220 × 180 mm3, nominal voxel size of 1.1 mm isotropic, SENSE factor = 2 × 2, duration of 5 min.

To obtain global OEF information, venous T2 values were also measured at the IJV by employing a T2prep module with five separate effective echo times (eTE) of 20, 40, 80, 120 and 160 ms. All the RF pulses used in the T2prep module were nonselective, to minimize sensitivity to flow. Composite refocusing pulses (90°x180°y90°x) were applied with constant inter-echo spacing of 10 ms. The MR protocol followed an earlier study (Qin, et al., 2011a) and the acquisition parameters were identical to the ones used for blood T1 measurements, with 1 min acquisition time as well.

BOLD fMRI experiments used a radial yellow/blue-colored checker-board flashing at 8 Hz. The visual paradigm had 30 second stimulation followed by 30 second of fixation on a cross sign in the center of the screen, with four repetitions. An additional fixation period of 30 seconds was used at the beginning of the experiment. BOLD sequence parameters were: TR / TE / FA = 2000 ms / 30 ms / 70°, nominal voxel size 2.5 × 2.5 × 2.5 mm3, SENSE factor = 2.1, 35 slices, FOV = 200 × 180 × 104 mm3, with 136 dynamics.

Data Analysis

Matlab (MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA) was used for data processing. Venous T1 (T1,v) was quantified following the fitting procedure described in (Li, et al., 2016b). A linear fitting was performed between 1000 / T1,v and Hct(lab), the Hct values provided by the CBC lab. Based on this calibration of Hct values from T1,v, subsequent studies used T1,v to determine Hct, which we indicate as Hct(T1,v).

Analysis of PC MRI data followed methods used in previous studies (Liu, et al., 2013b). ROI of each of the four arteries was drawn manually on the magnitude image by tracing the boundaries of left and right ICAs and VAs. The velocity values calculated from the phase information within the mask were summed to yield the flux (in mL/min) of each artery. To account for brain size differences, the unit volume CBF (in mL/min/100g) was obtained by normalizing the flux (in mL/min) of all four arteries to the parenchyma mass (in 100g), which was estimated from the high resolution T1-weighted MPRAGE image using the software FSL (FMRIB software Library, Oxford University).

Assuming Ya = 0.98, OEF was calculated as OEF = 1 - Yv/Ya. Based on previously reported Hct-dependent T2,v─Yv calibration curves (Lu, et al., 2012), Yv was determined from T2,v using either assumed Hct = 0.42 or Hct(T1,v).

Oxygen delivery was determined from Eq. [1] using Cery = 21.00 µmol O2/mL, Ya = 0.98, and the Hct and CBF determined experimentally. CMRO2 was calculated from DO2 and OEF using Eq. [2]. The units of DO2 and CMRO2 were µmol O2/min/100g.

Analysis of BOLD fMRI data was conducted using the software Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM) (University College London, UK, version 5.0) and in-house MATLAB scripts. Dynamic BOLD fMRI time series were registered to the respective first volume to remove motion. Then all BOLD images were co-registered to the template of Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) with a resampled voxel size of 2 × 2 × 2 mm3. Finally, the BOLD images were smoothed using a Gaussian filter with a full-width half-maximum (FWHM) of 8 mm. General linear analysis between voxel time course and stimulus paradigm convolved with a SPM defined hemodynamic function was used to compute voxel wise t score comparing BOLD signal strength during visual stimulation with respect to that during epochs of visual fixation. Then T score was ranked from high to low. Visual activation was defined by the top 2000 voxels within the occipital lobe (an approximation of visual cortex volume) on an individual basis. Time courses were averaged across these voxels. Percentage change of BOLD signal (SBOLD) was given by linear regression of averaged time course with respect to the paradigm regressor.

Mean, standard deviation (STD), and coefficient of variation (CoV = STD / Mean) across subjects were calculated for different physiological and functional parameters. Baseline CBF was investigated for a linear relationship with Hct(T1,v) by linear regression, y = a ∙ × + b. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant. The coefficient of determination, R2, represents the percentage of the variance of one parameter explained by the variation of the other using a best-fit linear model. Adjusted R2 was also calculated as:

| [3] |

This is to take into account the sample size (n) and number of variables (model complexity, m), and to correct the potential over-fitting issue caused by adding more regressors (Yin and Fan, 2001). Although in this study we only performed linear regression with one variable (m = 1), the adjusted R2 is intended to facilitate comparison with studies using multiple regressors.

Regression analyses of BOLD signal change were performed separately for its linear relationships (y = a ∙ × + b) with Hct and CBF. R2, R2adj, and P values of the fitting were also calculated. Furthermore, covariate effects were removed by subtracting the fitted equation from the initial BOLD response to calculate the normalized BOLD response:

| [4] |

Eq. [4] eliminates the dependence on both the slope (a) and the intercept of the fitted covariate model (b) (Liau and Liu, 2009). It also preserves the mean of the BOLD signal changes for consistent comparison of CoV (Lu, et al., 2010). The residual correlation and the between-subject CoV of SBOLD,n after normalizing with different baseline parameters were evaluated.

Results

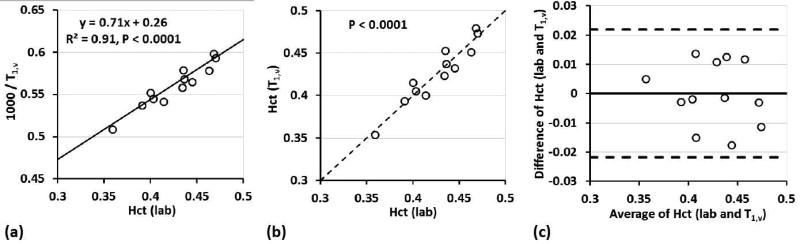

The Hct values from the CBC tests and the venous T1 values measured in vivo for all 13 subjects were previously reported (Li, et al., 2016b). Similar to the arterial blood T1 values reported in the same paper (Li, et al., 2016b), the venous T1 values correlated significantly with Hct (Fig. 1a) and the derived Hct values were calibrated as:

| [5] |

Linear regression (Fig. 1b) showed significant correlation (P < 0.0001) and Bland-Altman analysis (Fig. 1c) showed strong agreement between Hct(lab) and Hct(T1,v) (n = 12). We therefore from here on use only Hct(T1,v). Note that one subject was removed from this calibration as an outlier. The outlier detection was applied using the Grubbs criteria (Grubbs, 1950), which removes data with a difference more than 2 STD from the mean of the difference of Hct(lab) and Hct(T1,v). This outlier was rejected at the significance level of 0.05 (two sided).

Figure 1.

(a): Scatter plot of the inverse of MR measured venous blood T1 and pathology lab measured Hct, Hct(lab). The fitted linear equation is used to determine Hct from the individual T1 values. (b) Correlation plot of Hct(lab) and T1,v-converted Hct, Hct(T1,v). The dashed line is the unity line. (c) Agreement (Bland-Altman plot) between Hct(lab) and Hct(T1,v). The horizontal solid line represents the mean difference of all subjects. The top and bottom dashed lines indicate two times the standard deviation from the mean difference.

The group averaged Hct(T1,v) values along with the baseline hemodynamic and metabolic parameters are listed in Table 1. The CoV was 8.4% for Hct(T1,v) and 17.6% for CBF (Table 1). The CoV for DO2, OEF, and CMRO2 derived from Hct(T1,v) were 10.4%, 13.0%, and 11.2%, which were very close to the numbers using Hct(lab) and lower than the values using an assumed population-averaged Hct of 0.42: 17.6% (CBF effect only), 15.7%, and 12.4% (P < 0.05, t test on subsamples).

Table 1.

Summary of mean, standard deviation (STD) and coefficient of variance (CoV) of different parameters. Yv, DO2, OEF, and CMRO2 were calculated based on Hct = 0.42 and Hct(T1,v) respectively.

| T1,v (ms) |

T2,v (ms) |

Hct (lab) |

Hct (T1,v) |

Yv | CBF (mL /min /100g) |

DO2 (µmol/min/100g) |

OEF | CMRO2 (µmol/min/100g) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hct = 0.42 |

Hct (T1,v) |

Hct = 0.42 |

Hct (T1,v) |

Hct = 0.42 |

Hct (T1,v) |

Hct = 0.42 |

Hct (T1,v) |

||||||

| Mean | 1788 | 62.9 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 53.2 | 460.1 | 461.5 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 170.5 | 173.7 |

| STD | 83 | 11.8 | 0.034 | 0.036 | 0.058 | 0.048 | 9.4 | 81.1 | 47.8 | 0.059 | 0.049 | 21.1 | 19.5 |

| CoV | 4.6% | 18.7% | 8.0% | 8.4% | 9.6% | 8.0% | 17.6% | 17.6% | 10.4% | 15.7% | 13.0% | 12.4% | 11.2% |

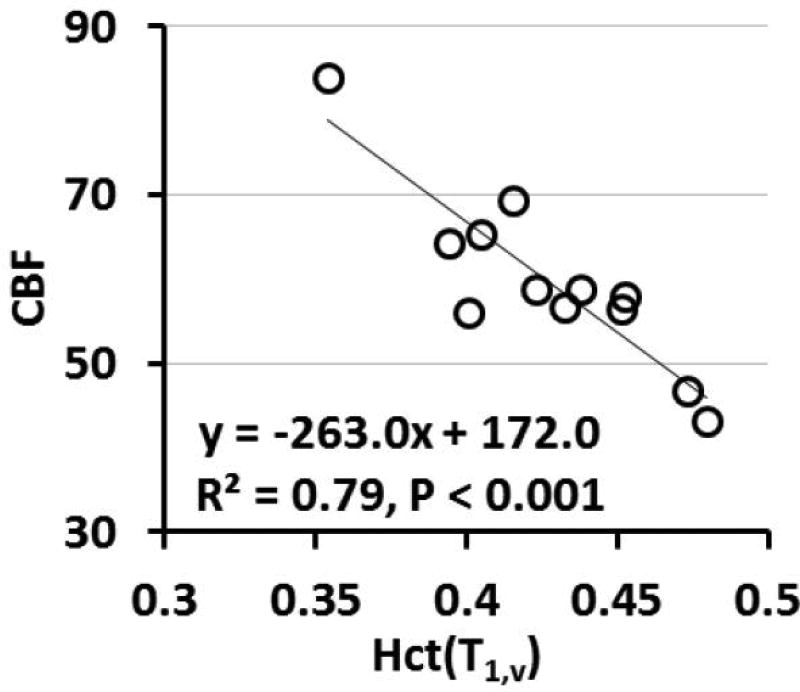

The significant inverse correlation of CBF with Hct(T1,v) (P < 0.001) is shown in Fig. 2. The calculated R2adj value indicates that 77% of the between-subject variation of CBF can be explained by Hct (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Scatter plots of baseline CBF with Hct(T1,v). The linear regression is illustrated with a solid line. CBF shows inverse correlation with Hct values significantly (P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Summary of the R2 and R2adj for regression analysis of CBF values on Hct and BOLD signal changes on Hct and CBF.

| CBF | SBOLD | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hct(T1,v) | Hct(T1,v) | CBF | |

| R2 | 0.79 | 0.29 | 0.39 |

| R2adj | 0.77 | 0.22 | 0.33 |

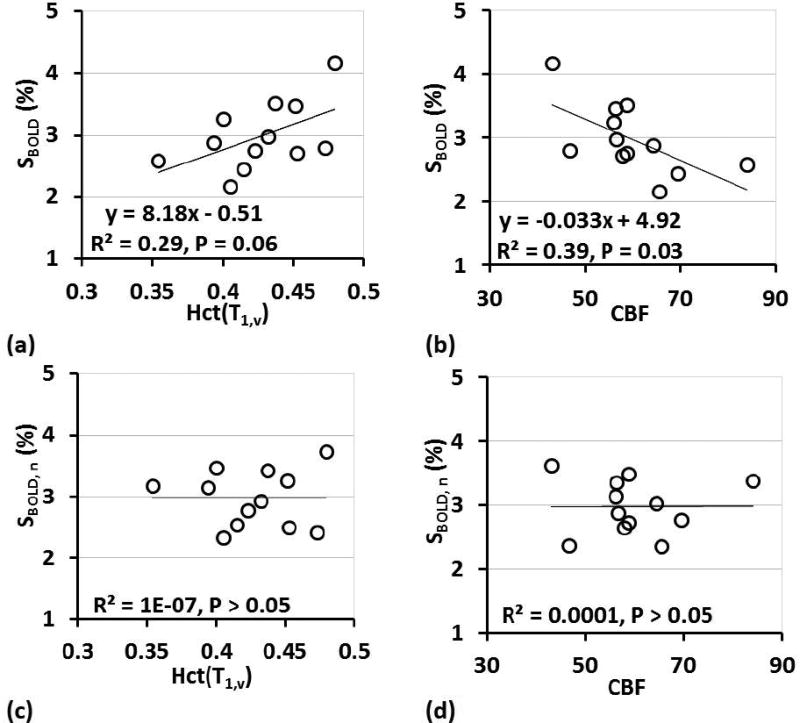

The BOLD signal response showed positive correlation with Hct(T1,v), along with negative correlation with CBF (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3a,b). Based on the R2adj values, Hct alone explained 22% of the between-subject variation of SBOLD, which was close to 33% for CBF (Table 2). After eliminating the effects of Hct and CBF respectively, the normalized BOLD responses, SBOLD,n, displayed no correlation with these parameters (Fig. 3c,d). The CoV of SBOLD was reduced by 16% and 22% (from 18.5% to 15.5% and 14.4%) after normalizing with Hct and CBF separately (Table 3).

Figure 3.

Scatter plots of BOLD signal change (SBOLD) with (a) Hct(T1,v) and (b) CBF. SBOLD were positively correlated with (a) Hct (P = 0.06) and negatively correlated with (b) CBF (P = 0.03). (c,d) Scatter plots of normalized BOLD signal change (SBOLD,n) after removing the variance explained by each effect (Eq. [4]).

Table 3.

CoV of the BOLD and residual BOLD signal after removing the variance explained by Hct and CBF respectively.

| SBOLD | SBOLD,n: Hct(T1,v) | SBOLD,n: CBF | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 2.98 | 2.97 | 2.98 |

| STD | 0.55 | 0.46 | 0.43 |

| CoV | 18.5% | 15.5% | 14.4% |

Discussion

In this study, we adopted a recently developed fast sequence to quantify blood T1 at IJV to estimate each individual’s Hct. We investigated the correlation of Hct with baseline CBF and their relationship with BOLD signal, which were all obtained from the same session on healthy volunteers in completely noninvasive fashion. This study highlights three roles Hct plays in baseline perfusion and hemodynamics functional responses: 1) using individual Hct and CBF enabled more precise estimation of DO2, OEF, and CMRO2; 2) Hct explained about 80% of the between-subject variation of CBF (Table 2, Fig. 2); 3) 22% of intersubject variability of BOLD response was associated with Hct (Table 2, Fig. 3a) and normalization of BOLD with Hct reduced its CoV by 16% (Table 3). The interrelations derived using blood T1-converted Hct information were consistent with those attained using lab test-based Hct values.

To prevent impairment of brain function, cerebral autoregulation relies on complex relationships between different hemodynamic and metabolic variables: CBF, CBV, DO2, OEF, and CMRO2 (Derdeyn, et al., 2002; Ito, et al., 2005). Monitoring these parameters concurrently facilitates comprehensive examination of both oxygen supply and oxygen metabolism. During the last decade, the MRI field has seen growing interest in developing noninvasive techniques for quantifying physiologic variables beyond CBF (Ewing and Lu, 2013; Wong, 2013). As observed in the present results, the between-subject CoV of DO2, OEF and CMRO2 were only 56–67% of CBF’s CoV (10–13% vs 18%, Table 1). This reduced intersubject variability of DO2, OEF and CMRO2 emphasizes their roles as more stable parameters in the presence of large physiological variation. Note that our measured CBF values have an inverse correlation with the measured OEF (data not shown), as expected based on Eqs. [1] and [2] and observed previously (Jain, et al., 2010; Liu, et al., 2013b; Peng, et al., 2014; Xu, et al., 2009). Thus CMRO2, as their product, is more constant across individuals, compared to these covarying parameters. Here we showed that by converting blood T1 to Hct, more precise estimation of these parameters per-subject was made both directly (DO2 and CMRO2) and indirectly (OEF, through using a Hct-dependent T2,v─Yv calibration model), compared to the typical practice of assuming the same Hct value for all subjects.

In this study, ~80% between-subject CoV of CBF was associated with Hct (Table 2, Fig. 2). To our best knowledge, this is the first MRI study on young healthy adults that confirmed previous understanding that between-subject variations of CBF can be partially explained by the variance in Hct (Brown, et al., 1985; Henriksen, et al., 2013; Herold, et al., 1986; Ibaraki, et al., 2010; Kuwabara, et al., 2002; Prohovnik, et al., 2009; Prohovnik, et al., 1989). Such a highly significant correlation between CBF and Hct was also found in an early report including subjects with both normal hematology and various blood disorders (Brown, et al., 1985). Our results indicate that, at least for the young healthy subjects recruited in this work, Hct is the primary determinant of the variability of CBF. Sex is often considered to be a covariate for CBF, which is largely due to the Hct difference between females and males (Henriksen, et al., 2013; Ibaraki, et al., 2010) (36% ~ 44% versus 41% ~ 50% (Chanarin, et al., 1984)).

CBF is known to be affected by many other factors, such as arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2), cardiac function, age, caffeine, smoking status, alcohol, psychiatric state, cardiovascular diseases, and pharmaceutical drugs (Giardino, et al., 2007; Henriksen, et al., 2013; Ibaraki, et al., 2010; Ito, et al., 2005; Lu, et al., 2011; van der Veen, et al., 2015). In a recent study examining factors affecting global CBF among a relatively healthy elderly group, 14% of between-subject CBF variation is explained by Hct, along with 17% by end-tidal PCO2 (PETCO2 ), 11% by Caffeine, and 10% by Homocysteine (Henriksen, et al., 2014). This much reduced effect of Hct to CBF variation is perhaps largely due to the difference of age (mean age [range] = 35 [27–51] years old vs 64 [50–75] years old) and sample size (n = 12 vs 38) between the two studies. It is expected that a range of additional factors other than Hct may contribute to CBF variability among an aged group compared to a younger population. For group-comparison studies, taking into account individual Hct could help disentangle the multiple covariates influencing the obtained CBF values.

Our inspection showed that the R2 values of the correlation between BOLD signal change for 8 Hz checkerboard visual activation and Hct(T1,v) and CBF were 0.29 and 0.39 (Table 2, Fig. 3a,b). Previous task-evoked functional studies reported R2 values for correlation between BOLD and Hct as 0.23 (Gustard, et al., 2003) and 0.28 (Levin, et al., 2001), and R2 values for correlation between BOLD and CBF as 0.17 (Lu, et al., 2008) and 0.46 (Liau and Liu, 2009). The high correlation between Hct and baseline CBF as discussed above elucidates the overlapping origin of these two regressors for BOLD response. These fitted correlation not only illustrate various sources of the variability for BOLD signal but also were useful for the normalization of the SBOLD to lower its CoV (Eq. [4], Table 3, Fig. 3c,d). The reduction of between-subject CoV of SBOLD,n is desired for enhancing the detection power in the group-level comparisons (Liau and Liu, 2009; Liu, et al., 2013a; Liu, et al., 2013c; Lu, et al., 2010).

A few notes of the methodology of this study need to be commented upon. First, the measured venous T1 values are dependent on both Hct and Yv (Brooks and Dichiro, 1987; Bryant, et al., 1990; Grgac, et al., 2013; Li, et al., 2016a; Lu, et al., 2004; Silvennoinen, et al., 2003). Except during ischemia, arterial T1 is only affected by Hct since Ya is close to 1, thus is in theory a better surrogate for Hct estimation. Comparing to measuring arterial T1 values, measuring venous T1 values is relatively straightforward. Our data suggested that venous T1 values are also largely modulated by Hct among normal volunteers and Hct values derived from T1,v show high correlation and agreement with lab measured Hct (Fig. 1). When Yv values of the populations under investigation have large variations, arterial blood T1 is suggested for more accurate Hct estimation using a previously developed conversion formula (Li, et al., 2016b). Note that several methods were developed to rapidly measure venous T1 in vivo, all of which used a Look-Locker scheme but with various acquisition modules: segmented balanced steady-state free precession, bSSFP (Wu, et al., 2010); single-shot EPI (Varela, et al., 2011); segmented EPI (Qin, et al., 2011b); and segmented TFE (Li, et al., 2016b). The reported average T1,v values for healthy females and males agree well: 1831/1746 ms (Li, et al., 2016b), 1779/1662 ms (Varela, et al., 2011), and 1827/1677 ms (Wu, et al., 2010). Based on our calibration formula Eq. [5], ±5% error of T1,v measurement would cause 9–10% under- or over-estimation of Hct, respectively. Thus the Hct method does not depend critically on the sequence used.

Second, this work obtained global CBF using PC MRA instead of regional CBF using ASL. Compared to ASL, PC MRA is a faster approach for estimating global flow rate with simpler methodology for both acquisition and analysis. In contrast, ASL can provide local perfusion values. It is expected that regional differences in the correlation between baseline CBF and Hct may exist, due to the relationship between CBF and local neuronal activity. ASL can be technically challenging and has low signal sensitivity. Additionally, ASL is sensitive to blood T1 (Alsop, et al., 2015) and CBF values could be underestimated using overestimated blood T1. A recent study in a large population reported significant correlation between these two methods (Dolui, et al., 2016). More variance in CBF values estimated with PC MRA was reported and may be related to inaccurate placement of a single imaging plane through all arteries of interest (Dolui, et al., 2016). Note that non-gated PC MRA scans were performed in our study for estimating global CBF values. Additionally, the dynamic variation of arterial lumen area over the cardiac cycle was not considered. Changes in lumen area of up to 27% have been reported between diastolic and systolic phases in common carotid arteries (Chow, et al., 2008). Nonetheless, the effect of cardiac pulsation might be canceled out by signal averaging during the 20 sec PC MRA scans. Earlier work from small groups of subjects did not find significant difference of averaged velocity from PC MRA with or without cardiac gating (Qin, et al., 2011b; Xu, et al., 2009).

Third, one limitation of our visual stimuli-evoked BOLD experiments is that no MR-compatible vision-correction lenses were provided for subjects with myopia, which resulted in additional subject-dependent variations into the BOLD signal (Lu, et al., 2010). This may have increased the inter-individual variation in BOLD signals reported in the present study.

Lastly, we did not separate the between-subject variations of each MRI outcome from the within-subject variations or measurement noise of the techniques used. This is usually determined by repeated measures on each subject. Recently we reported that the intra-session, inter-session and inter-subject CoV of obtained arterial blood T1 values were 1.1%, 2.1% and 5.6%, respectively (Li, et al., 2016b). A previous study using the same PC MRA protocol for CBF estimation showed its intra-session, inter-session and inter-subject CoV to be 2.8%, 7.4% and 17.4%, respectively (Liu, et al., 2013b). CoV of BOLD signal reproducibility for the visual task was 14% depending upon the extent of spatial smoothing applied (Raemaekers, et al., 2012).

Although Hct effects have been separately analyzed in various studies of CBF, DO2, OEF, CMRO2 and functional BOLD as aforementioned, this work sought to revisit and emphasize its importance in adopting a more multi-parametric and integral approach in MRI field. Since blood T1 itself is an important parameter for quantifying CBF using ASL (Alsop, et al., 2015) and CBV change using vascular space occupancy (VASO) techniques (Lu, et al., 2003), Hct measures from blood T1 values will prove to be an effective noninvasive approach assisting perfusion and functional MRI studies, at least for healthy volunteers. The calibrated Hct─T1,v relation (Eq. [5]) is not expected to be valid for patients with different hemoglobins (e.g. sickled blood or fetal blood). Recent advances in multi-wavelength pulse oximetry permit estimation of total hemoglobin or Hct using a percutaneous sensor (Barker and Badal, 2008; Lindner and Exadaktylos, 2013). The accuracy of this technique has been evaluated in different clinical settings and promising results have been demonstrated (Frasca, et al., 2011; Lindner and Exadaktylos, 2013). Our internal comparison with CBC lab test on both healthy volunteers and those with anemia found lack of accuracy for a subgroup (data not shown). Once further improved and validated, a handheld pulse oximeter would be an ideal point of care device for both Hct and Ya determination for a broad population.

Conclusion

We utilized a recently developed MR technique to quickly (1 min) and noninvasively (no blood draw) estimate Hct values in normal volunteers. This allowed more convenient and precise per-subject determination of physiological parameters that characterize oxygen delivery, extraction, and consumption in the brain. The close correlation of Hct with baseline CBF and task-based BOLD signal changes indicates that Hct may play an important role in explaining inter-individual variance of baseline CBF and thus BOLD signal responses. In addition, we showed that BOLD signal normalized with Hct had less variability than original BOLD signal. These findings are pertinent to a wide range of MRI based brain perfusion and function studies.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

Grant support from K25 HL121192 (QQ), Scholar Award of American Society of Hematology (QQ), and NIH P41 EB015909 (PvZ).

References

- Alsop DC, Detre JA, Golay X, Gunther M, Hendrikse J, Hernandez-Garcia L, Lu H, MacIntosh BJ, Parkes LM, Smits M, van Osch MJ, Wang DJ, Wong EC, Zaharchuk G. Recommended implementation of arterial spin-labeled perfusion MRI for clinical applications: A consensus of the ISMRM perfusion study group and the European consortium for ASL in dementia. Magn Reson Med. 2015;73:102–16. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker CJ, Hoogeveen RM, Viergever MA. Construction of a protocol for measuring blood flow by two-dimensional phase-contrast MRA. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging : JMRI. 1999;9:119–27. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2586(199901)9:1<119::aid-jmri16>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker SJ, Badal JJ. The measurement of dyshemoglobins and total hemoglobin by pulse oximetry. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2008;21:805–10. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e328316bb6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blockley NP, Griffeth VE, Simon AB, Buxton RB. A review of calibrated blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) methods for the measurement of task-induced changes in brain oxygen metabolism. NMR in biomedicine. 2013;26:987–1003. doi: 10.1002/nbm.2847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks RA, Dichiro G. Magnetic-Resonance-Imaging of Stationary Blood - a Review. Medical Physics. 1987;14:903–913. doi: 10.1118/1.595994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MM, Wade JP, Marshall J. Fundamental importance of arterial oxygen content in the regulation of cerebral blood flow in man. Brain : a journal of neurology. 1985;108(Pt 1):81–93. doi: 10.1093/brain/108.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant RG, Marill K, Blackmore C, Francis C. Magnetic-Relaxation in Blood and Blood-Clots. Magn Reson Med. 1990;13:133–144. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910130112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanarin I, Brozovic M, Tidmarsh E, Waters D. Blood and its disease. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Chow TY, Cheung JS, Wu Y, Guo H, Chan KC, Hui ES, Wu EX. Measurement of common carotid artery lumen dynamics during the cardiac cycle using magnetic resonance TrueFISP cine imaging. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging : JMRI. 2008;28:1527–32. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai W, Garcia D, de Bazelaire C, Alsop DC. Continuous flow-driven inversion for arterial spin labeling using pulsed radio frequency and gradient fields. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60:1488–97. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derdeyn CP, Videen TO, Yundt KD, Fritsch SM, Carpenter DA, Grubb RL, Powers WJ. Variability of cerebral blood volume and oxygen extraction: stages of cerebral haemodynamic impairment revisited. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2002;125:595–607. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detre JA, Leigh JS, Williams DS, Koretsky AP. Perfusion Imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1992;23:37–45. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910230106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolui S, Wang Z, Wang DJ, Mattay R, Finkel M, Elliott M, Desiderio L, Inglis B, Mueller B, Stafford RB, Launer LJ, Jacobs DR, Jr, Bryan RN, Detre JA. Comparison of non-invasive MRI measurements of cerebral blood flow in a large multisite cohort. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2016;36:1244–56. doi: 10.1177/0271678X16646124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans AJ, Iwai F, Grist TA, Sostman HD, Hedlund LW, Spritzer CE, Negro-Vilar R, Beam CA, Pelc NJ. Magnetic resonance imaging of blood flow with a phase subtraction technique. In vitro and in vivo validation. Investigative radiology. 1993;28:109–15. doi: 10.1097/00004424-199302000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing J, Lu H. MRI measures of cerebral physiology. NMR in biomedicine. 2013;26:885–6. doi: 10.1002/nbm.2998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan AP, Bilgic B, Gagnon L, Witzel T, Bhat H, Rosen BR, Adalsteinsson E. Quantitative oxygenation venography from MRI phase. Magn Reson Med. 2014;72:149–59. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Seara MA, Techawiboonwong A, Detre JA, Wehrli FW. MR susceptometry for measuring global brain oxygen extraction. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55:967–73. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasca D, Dahyot-Fizelier C, Catherine K, Levrat Q, Debaene B, Mimoz O. Accuracy of a continuous noninvasive hemoglobin monitor in intensive care unit patients. Critical care medicine. 2011;39:2277–82. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182227e2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giardino ND, Friedman SD, Dager SR. Anxiety, respiration, and cerebral blood flow: implications for functional brain imaging. Compr Psychiatry. 2007;48:103–12. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grgac K, van Zijl PC, Qin Q. Hematocrit and oxygenation dependence of blood (1)H(2)O T(1) at 7 Tesla. Magn Reson Med. 2013;70:1153–9. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubbs FE. Sample Criteria for Testing Outlying Observations. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 1950;21:27–58. [Google Scholar]

- Gustard S, Williams EJ, Hall LD, Pickard JD, Carpenter TA. Influence of baseline hematocrit on between-subject BOLD signal change using gradient echo and asymmetric spin echo EPI. Magn Reson Imaging. 2003;21:599–607. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(03)00083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haacke EM, Lai S, Reichenbach JR, Kuppusamy K, Hoogenraad FG, Takeichi H, Lin W. In vivo measurement of blood oxygen saturation using magnetic resonance imaging: a direct validation of the blood oxygen level-dependent concept in functional brain imaging. Hum Brain Mapp. 1997;5:341–6. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(1997)5:5<341::AID-HBM2>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen OM, Jensen LT, Krabbe K, Guldberg P, Teerlink T, Rostrup E. Resting brain perfusion and selected vascular risk factors in healthy elderly subjects. PloS one. 2014;9:e97363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen OM, Kruuse C, Olesen J, Jensen LT, Larsson HB, Birk S, Hansen JM, Wienecke T, Rostrup E. Sources of variability of resting cerebral blood flow in healthy subjects: a study using (1)(3)(3)Xe SPECT measurements. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:787–92. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herold S, Brozovic M, Gibbs J, Lammertsma AA, Leenders KL, Carr D, Fleming JS, Jones T. Measurement of regional cerebral blood flow, blood volume and oxygen metabolism in patients with sickle cell disease using positron emission tomography. Stroke. 1986;17:692–8. doi: 10.1161/01.str.17.4.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hino A, Ueda S, Mizukawa N, Imahori Y, Tenjin H. Effect of hemodilution on cerebral hemodynamics and oxygen metabolism. Stroke. 1992;23:423–6. doi: 10.1161/01.str.23.3.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua J, Stevens RD, Huang AJ, Pekar JJ, van Zijl PC. Physiological origin for the BOLD poststimulus undershoot in human brain: vascular compliance versus oxygen metabolism. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31:1599–611. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudak ML, Koehler RC, Rosenberg AA, Traystman RJ, Jones MD., Jr Effect of hematocrit on cerebral blood flow. The American journal of physiology. 1986;251:H63–70. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1986.251.1.H63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibaraki M, Shinohara Y, Nakamura K, Miura S, Kinoshita F, Kinoshita T. Interindividual variations of cerebral blood flow, oxygen delivery, and metabolism in relation to hemoglobin concentration measured by positron emission tomography in humans. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30:1296–305. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito H, Kanno I, Fukuda H. Human cerebral circulation: positron emission tomography studies. Ann Nucl Med. 2005;19:65–74. doi: 10.1007/BF03027383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain V, Langham MC, Wehrli FW. MRI estimation of global brain oxygen consumption rate. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30:1598–607. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SG, Ogawa S. Biophysical and physiological origins of blood oxygenation level-dependent fMRI signals. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:1188–206. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwabara Y, Sasaki M, Hirakata H, Koga H, Nakagawa M, Chen T, Kaneko K, Masuda K, Fujishima M. Cerebral blood flow and vasodilatory capacity in anemia secondary to chronic renal failure. Kidney Int. 2002;61:564–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin JM, Frederick Bde B, Ross MH, Fox JF, von Rosenberg HL, Kaufman MJ, Lange N, Mendelson JH, Cohen BM, Renshaw PF. Influence of baseline hematocrit and hemodilution on BOLD fMRI activation. Magn Reson Imaging. 2001;19:1055–62. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(01)00460-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Grgac K, Huang A, Yadav N, Qin Q, van Zijl PC. Quantitative theory for the longitudinal relaxation time of blood water. Magn Reson Med. 2016a;76:270–81. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Liu P, Lu H, Strouse JJ, van Zijl PC, Qin Q. Fast measurement of blood T1 in the human carotid artery at 3T: Accuracy, precision, and reproducibility. Magn Reson Med. 2016b doi: 10.1002/mrm.26325. Epub Ahead of Print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liau J, Liu TT. Inter-subject variability in hypercapnic normalization of the BOLD fMRI response. Neuroimage. 2009;45:420–30. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W, Paczynski RP, Celik A, Hsu CY, Powers WJ. Effects of acute normovolemic hemodilution on T2*-weighted images of rat brain. Magn Reson Med. 1998a;40:857–64. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910400611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W, Paczynski RP, Celik A, Hsu CY, Powers WJ. Experimental hypoxemic hypoxia: effects of variation in hematocrit on magnetic resonance T2*-weighted brain images. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1998b;18:1018–21. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199809000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindner G, Exadaktylos AK. How Noninvasive Haemoglobin Measurement with Pulse CO-Oximetry Can Change Your Practice: An Expert Review. Emerg Med Int. 2013;2013:701529. doi: 10.1155/2013/701529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P, Hebrank AC, Rodrigue KM, Kennedy KM, Park DC, Lu H. A comparison of physiologic modulators of fMRI signals. Hum Brain Mapp. 2013a;34:2078–88. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P, Xu F, Lu H. Test-retest reproducibility of a rapid method to measure brain oxygen metabolism. Magn Reson Med. 2013b;69:675–81. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu TT, Glover GH, Mueller BA, Greve DN, Brown GG. An introduction to normalization and calibration methods in functional MRI. Psychometrika. 2013c;78:308–21. doi: 10.1007/s11336-012-9309-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H, Clingman C, Golay X, van Zijl PCM. Determining the Longitudinal Relaxation Time (T1) of Blood at 3.0 Tesla. Magn Reson Med. 2004;52:679–682. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H, Golay X, Pekar JJ, van Zijl PCM. Functional magnetic resonance Imaging based on changes in vascular space occupancy. Magn Reson Med. 2003;50:263–274. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H, Xu F, Grgac K, Liu P, Qin Q, van Zijl P. Calibration and validation of TRUST MRI for the estimation of cerebral blood oxygenation. Magn Reson Med. 2012;67:42–49. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H, Xu F, Rodrigue KM, Kennedy KM, Cheng Y, Flicker B, Hebrank AC, Uh J, Park DC. Alterations in cerebral metabolic rate and blood supply across the adult lifespan. Cereb Cortex. 2011;21:1426–34. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H, Yezhuvath US, Xiao G. Improving fMRI sensitivity by normalization of basal physiologic state. Hum Brain Mapp. 2010;31:80–7. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu HZ, Ge YL. Quantitative evaluation of oxygenation in venous vessels using T2-Relaxation-Under-Spin-Tagging MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60:357–363. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu HZ, Zhao CG, Ge YL, Lewis-Amezcua K. Baseline blood oxygenation modulates response amplitude: Physiologic basis for intersubject variations in functional MRI signals. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60:364–372. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massik J, Tang YL, Hudak ML, Koehler RC, Traystman RJ, Jones MD., Jr Effect of hematocrit on cerebral blood flow with induced polycythemia. J Appl Physiol. 1987;62:1090–6. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1987.62.3.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metry G, Wikstrom B, Valind S, Sandhagen B, Linde T, Beshara S, Langstrom B, Danielson BG. Effect of normalization of hematocrit on brain circulation and metabolism in hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:854–63. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V104854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oja JME, Gillen JS, Kauppinen RA, Kraut M, van Zijl PCM. Determination of oxygen extraction ratios by magnetic resonance imaging. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 1999;19:1289–1295. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199912000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng SL, Dumas JA, Park DC, Liu P, Filbey FM, McAdams CJ, Pinkham AE, Adinoff B, Zhang R, Lu H. Age-related increase of resting metabolic rate in the human brain. Neuroimage. 2014;98:176–83. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.04.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prohovnik I, Hurlet-Jensen A, Adams R, De Vivo D, Pavlakis SG. Hemodynamic etiology of elevated flow velocity and stroke in sickle-cell disease. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:803–10. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prohovnik I, Pavlakis SG, Piomelli S, Bello J, Mohr JP, Hilal S, De Vivo DC. Cerebral hyperemia, stroke, and transfusion in sickle cell disease. Neurology. 1989;39:344–8. doi: 10.1212/wnl.39.3.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Q, Grgac K, van Zijl PC. Determination of whole-brain oxygen extraction fractions by fast measurement of blood T(2) in the jugular vein. Magn Reson Med. 2011a;65:471–9. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Q, Strouse JJ, van Zijl PC. Fast measurement of blood T(1) in the human jugular vein at 3 Tesla. Magn Reson Med. 2011b;65:1297–304. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raemaekers M, du Plessis S, Ramsey NF, Weusten JM, Vink M. Test-retest variability underlying fMRI measurements. Neuroimage. 2012;60:717–27. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvennoinen MJ, Kettunen MI, Kauppinen RA. Effects of hematocrit and oxygen saturation level on blood spin-lattice relaxation. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49:568–571. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Veen PH, Muller M, Vincken KL, Westerink J, Mali WP, van der Graaf Y, Geerlings MI, Group SS. Hemoglobin, hematocrit, and changes in cerebral blood flow: the Second Manifestations of ARTerial disease-Magnetic Resonance study. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36:1417–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Zijl PC, Hua J, Lu H. The BOLD post-stimulus undershoot, one of the most debated issues in fMRI. Neuroimage. 2012;62:1092–102. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Zijl PCM, Eleff SM, Ulatowski JA, Oja JME, Ulug AM, Traystman RJ, Kauppinen RA. Quantitative assessment of blood flow, blood volume and blood oxygenation effects in functional magnetic resonance imaging. Nature Medicine. 1998;4:159–167. doi: 10.1038/nm0298-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varela M, Hajnal JV, Petersen ET, Golay X, Merchant N, Larkman DJ. A method for rapid in vivo measurement of blood T1. NMR in biomedicine. 2011;24:80–8. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorstrup S, Lass P, Waldemar G, Brandi L, Schmidt JF, Johnsen A, Paulson OB. Increased cerebral blood flow in anemic patients on long-term hemodialytic treatment. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1992;12:745–9. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1992.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong EC. New developments in arterial spin labeling pulse sequences. NMR in biomedicine. 2013;26:887–91. doi: 10.1002/nbm.2954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong EC, Buxton RB, Frank LR. Quantitative imaging of perfusion using a single subtraction (QUIPSS and QUIPSS II) Magn Reson Med. 1998;39:702–8. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910390506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright GA, Hu BS, Macovski A. Estimating Oxygen-Saturation of Blood Invivo with Mr Imaging at 1.5t. Jmri-Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 1991;1:275–283. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880010303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu WC, Jain V, Li C, Giannetta M, Hurt H, Wehrli FW, Wang J. In Vivo Venous Blood T1 Measurement Using Inversion Recovery True-FISP in Children and Adults. Magn Reson Med. 2010;64:1140–1147. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F, Ge YL, Lu HZ. Noninvasive Quantification of Whole-Brain Cerebral Metabolic Rate of Oxygen (CMRO2) by MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2009;62:141–148. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin P, Fan X. Estimating R2 Shrinkage in Multiple Regression: A Comparison of Different Analytical Methods. The Journal of Experimental Education. 2001;69:203–224. [Google Scholar]

- Zananiri FV, Jackson PC, Goddard PR, Davies ER, Wells PN. An evaluation of the accuracy of flow measurements using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) Journal of medical engineering & technology. 1991;15:170–6. doi: 10.3109/03091909109023704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Liu T, Gupta A, Spincemaille P, Nguyen TD, Wang Y. Quantitative mapping of cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen (CMRO2 ) using quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM) Magn Reson Med. 2015;74:945–52. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou P, Helton KJ, Smeltzer M, Li CS, Conklin HM, Gajjar A, Wang WC, Ware RE, Ogg RJ. Hemodynamic responses to visual stimulation in children with sickle cell anemia. Brain Imaging Behav. 2011;5:295–306. doi: 10.1007/s11682-011-9133-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]