Abstract

Objective

To describe disease course, histopathology, and outcomes for infants with atypical presentations of alveolar capillary dysplasia with misalignment of the pulmonary veins (ACDMPV) who underwent bilateral lung transplantation.

Study design

We reviewed clinical history, diagnostic studies, explant histology, genetic results, and post-transplant course for 6 infants with atypical ACDMPV who underwent bilateral lung transplantation at St. Louis Children’s Hospital. We compared their histology with infants with classic ACDMPV and compared their outcomes with infants transplanted for other indications.

Results

In contrast to neonates with classic ACDPMV who present with severe hypoxemia and refractory pulmonary hypertension within hours of birth, none of the infants with atypical ACDMPV presented with progressive neonatal respiratory failure. Three infants had mild neonatal respiratory distress and received nasal cannula oxygen. Three other infants had no respiratory symptoms at birth and presented with hypoxemia and pulmonary hypertension at 2–3 months of age. Bilateral lung transplantation was performed at 4–20 months. Unlike in classic ACDMPV, histopathologic findings were not uniformly distributed and were not diffuse. Three subjects had apparent non-mosaic genetic defects involving FOXF1. Two infants had extra-pulmonary anomalies (posterior urethral valves, inguinal hernia). Three transplanted children are alive at 5–16 years, similar to outcomes for infants transplanted for other indications. Lung explants from infants with atypical ACDMPV demonstrated diagnostic but nonuniform histopathologic findings.

Conclusions

One and 5-year survival rates for infants with atypical ACDM are similar to infants transplanted for other indications. Given the clinical and histopathologic spectra, ACDMPV should be considered in infants with hypoxemia and pulmonary hypertension, even beyond the newborn period.

Keywords: Diffuse developmental lung disorder

Alveolar capillary dysplasia with misalignment of the pulmonary veins (ACDMPV, OMIM 265380) is a rare developmental lung disorder with nearly uniform mortality in the first month of life.1, 2 Neonates with classic ACDMPV are typically born at term and present with progressive, hypoxemic respiratory failure and severe, refractory pulmonary hypertension within the first few hours after birth. Extra-pulmonary anomalies are common and typically involve the gastrointestinal, cardiac, and/or genitourinary systems.3 Although there are a few case reports of infants with atypical presentations of ACDMPV beyond the newborn period or with less fulminant neonatal disease,4–9 (Table I; available at www.jpeds.com) the clinical, histopathologic, and genetic factors that contribute to delayed or less severe presentations are not well characterized.

Table 1.

Published Reports of Infants with Delayed Presentation of ACD/MPV

| Age at presen- tation |

EGA wks |

Sex | Family history |

Neonatal Symptoms |

Additional Anomalies |

Pulmonary Hypertension Medications |

Histology | FOXF1 Sequencing |

Outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 weeks | Term | Female | Male sibling with ACD/MPV | Cyanosis at respiratory distress, episodes of tachypnea and lethargy, discharged home at 10 days | None | Norepinephrine, intrapulmonary prostaglandin E1, | Capillaries of alveolar septa did not reach alveolar epithelium, muscularization of peripheral arterial branches, misalignment of the pulmonary veins, dilated lymphatics | NR | Death at 5 weeks | (1) |

| 4 weeks | NR | NR | NR | None | None | iNO, prostatcylin | Alveolar capillary dysplasia | NR | Death during hospital course | (2) |

| 7 weeks | Term | Female | NR | None | Aganglionosis of colon | Dopamine, milrinone, iNO | Malalignment of pulmonary veins, paucity of alveolar capillaries, prominent muscularization of arterioles, thickening of alveolar septa, widened interstitium | NR | Death at 4 months | (3) |

| 7 months | Term | Female | NR | Cyanotic episode after birth, received 0.1L/min oxygen for 13 days, mild pulmonary hypertension on echocardiogram | Small ventricular septal defect | Dopamine, milrinone, iNO | Small pulmonary lobules, few normally positioned capillaries, muscularized small arterioles, misalignment of the pulmonary veins, patchy lymphatic dilation | NR | Death at 7–8 months | (4) |

| 3 months | Term | Male | Negative | None | Muscular ventricular septal defect, small atrial septal defect | Milrinone, iNO, pulse methylprednisolone, IVIG, sildenafil, prostacyclin, bosentan, supplemental oxygen | MPV, thick alveolar walls with pool alveolar capillary development, several normal alveolar walls | c.899Tdel p.L300Rfs*79 de novo |

Alive at 38 months per manuscript, alive at 62 months* | (5) |

EGA= estimated gestational age, iNO= inhaled nitric oxide, NR= not reported

Personal communication: Dr. Satoru Kumaki 1/2017

Abdallah HI, Karmazin N, Marks LA. Late presentation of misalignment of lung vessels with alveolar capillary dysplasia. Critical care medicine. 1993;21(4):628–30.

Michalsky MP, Arca MJ, Groenman F, Hammond S, Tibboel D, Caniano DA. Alveolar capillary dysplasia: a logical approach to a fatal disease. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2005;40(7):1100–5.

Shankar V, Haque A, Johnson J, Pietsch J. Late presentation of alveolar capillary dysplasia in an infant. Pediatric critical care medicine : a journal of the Society of Critical Care Medicine and the World Federation of Pediatric Intensive and Critical Care Societies. 2006;7(2):177–9.

Ahmed S, Ackerman V, Faught P, Langston C. Profound hypoxemia and pulmonary hypertension in a 7-month-old infant: late presentation of alveolar capillary dysplasia. Pediatric critical care medicine : a journal of the Society of Critical Care Medicine and the World Federation of Pediatric Intensive and Critical Care Societies. 2008;9(6):e43–6.

Ito Y, Akimoto T, Cho K, Yamada M, Tanino M, Dobata T, et al. A late presenter and long-term survivor of alveolar capillary dysplasia with misalignment of the pulmonary veins. European journal of pediatrics. 2015;174(8):1123–6.

The diagnosis of ACDMPV is made by histologic examination of lung tissue.10 Due to the high neonatal mortality rate, many infants are diagnosed at autopsy although a steady increase in diagnosis by lung biopsy has recently been observed.3 The histopathologic features diagnostic of ACDMPV include deficient capillarization of the alveoli (decreased numbers of capillaries with displacement from alveolar epithelium), malposition of pulmonary veins adjacent to small pulmonary arteries within the same bronchovascular bundle (BVB), and medial hypertrophy of small pulmonary arteries and arterioles. Lobular maldevelopment with deficient alveolarization and lymphangiectasis are also commonly observed.1, 11–13 Although it has been speculated that infants with delayed or less fulminant (atypical) presentations may have non-uniform distribution of disease that does not involve the entire lung, less abnormal density and placement of capillaries, or more normal lobular development,5, 14, 15 limited information regarding the lung histopathology of these infants is available and often from only a single biopsy site.

Although outcomes after bilateral lung transplant in infants with end-stage lung disease due to genetic disorders of surfactant metabolism, interstitial lung disease (ILD), and pulmonary vascular disease have been reported,16 the long-term outcomes of patients transplanted after atypical presentation of ACDMPV presentation have not been reported. Here we report clinical data and histologic characterization from the largest series of infants with atypical presentations of ACDMPV who underwent lung transplantation.

Methods

Through a search of the St. Louis Children’s Hospital/Washington University School of Medicine Pediatric Lung Transplantation database, we identified 6 infants with atypical presentations of ACDMPV admitted over an 18 year period (1998–2016) who underwent bilateral lung transplantation. We obtained informed consent from parents of all infants and children and this study was approved by the Human Research Protection Office at Washington University. We reviewed clinical history, results from echocardiogram, cardiac catheterization, and chest computed tomography (CT), explant histology, and post-transplant course. We used Sanger sequencing to identify mutations in FOXF1 as previously described.17 We analyzed genomic copy number variants using array comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) with custom-designed 16q24.1 region-specific 3_720 K microarrays (Roche NimbleGen, Madison, WI).17

A pediatric pathologist with expertise in childhood interstitial lung disease and the diagnostic features of ACDMPV reviewed all explants. At least 2 sections from each lobe of the explant were reviewed for each subject (median number of sections per explant was 22 (range 12–27)). Explant histology was compared with autopsy histology from 3 infants with classic ACDMPV and genetic defects of FOXF1 (2 with missense point mutations and 1 with a copy number variant (CNV) deletion upstream of FOXF1). ACDMPV histologic criteria were characterized for each explant.15, 18 Microscopic observations of alveolar capillaries were made on fields of congested, non-collapsed lung, in which architecture and capillaries were well visualized. Findings of deficient capillarization of alveoli were described as “diffuse” (present throughout all fields, with difficulty in identifying normal capillarization in most fields), “mixed” (mixture of both normal and deficient capillarization throughout lung), and “focal” (predominantly normal, with focal areas of deficient capillarization). Findings of pulmonary vein malposition adjacent to small arteries were described as “extensive” (readily identified throughout the lung, with malposition in the majority of BVBs), “patchy” (identified throughout the lung, but in fewer than half of BVBs), and “focal” (present, but in minority of BVBs and not readily identified). Assessment of malposition of pulmonary veins did not include BVBs with tangential orientation in which a vein could not be excluded. Findings of medial hypertrophy of small arteries and arterioles were graded “mild,” “moderate,” or “severe,” ranging from mild medial thickening to occlusive lesions. Lobular maldevelopment with deficient alveolarization was noted based on the presence of enlarged alveoli with apparent decrease in numbers of alveoli and was described as “present,” “suggestive,” (areas suggestive of deficient alveolarization), or “not suggestive.” Lymphangiectasis was characterized as primarily involving the interlobular septae or involving both the interlobular septae and the BVBs.

Infant #1 (Table 2)

Table 2.

Clinical Characteristics of Infants with Atypical Presentation of ACDMPV

| Patient | EGA (wks) |

Neonatal Symptoms |

Age at Presentation |

Cardiac Anomalies |

Additional Anomalies |

CT imaging | Cardiac Catheterization |

Pulmonary Hypertension Medications |

ECMO | Support at Time of Lung Transplant |

Age

at Transplant (months) |

Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Term | Transient tachypnea at birth, discharged home on room air | 3 months (109 days) | None | Inguinal hernia | Not available | Not performed | Prostacyclin, inhaled NO (iNO) | Prior to transplant | Mechanical Ventilation | 4 | Second transplant at 4 years; died at 5 years |

| 2 | Term | Respiratory distress, pulmonary hypertension | Birth | Patent foramen ovale | Posterior urethral valves | Ground glass opacities, enlarged pulmonary vessels | Suprasystemic right ventricular (RV) pressure, responsive to iNO | Nifedipine, iNO | No | NO and O2 via nasal cannula | 20 | Second transplanted at 4 years; alive at 16 years |

| 3 | 36 | None | 2 months (71 days) | Patent foramen ovale | None | Diffuse interstitial lung disease, associated cystic areas | Not performed | Milrinone, methylprednisolone, iNO | No | Mechanical Ventilation | 5 | Alive at 14 years |

| 4 | 34 | Poor feeding, abdominal distension at 3 days | 2 months (67 days) | Secundum atrial septal defect | None | Ground glass opacities, interstitial septal thickening | Suprasystemic RV pressure, responsive to iNO | Sildenafil, milrinone, iNO | No | Mechanical Ventilation | 5 | Died at 9 years |

| 5 | 34 | Apnea at 3 weeks | 3 months (92 days) | Patent foramen ovale | None | Ground glass opacities | Not performed | Sildenafil Prednisolone, iNO | At transplant | ECMO | 9 | Alive at 5 years |

| 6 | Term | Transient tachypnea, discharged home on O2 for 21 days | 7 months (212 days) | Patent ductus arteriosus | None | Ground glass opacities with septal thickening | Near systemic RV pressure, responsive to iNO | Sildenafil, methylprednisolone, iNO | Prior to transplant | Positive pressure ventilation via RAM cannula | 15 | Died at 18 months |

Boston US, Fehr J, Gazit AZ, Eghtesady P. Paracorporeal lung assist device: an innovative surgical strategy for bridging to lung transplant in an infant with severe pulmonary hypertension caused by alveolar capillary dysplasia. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2013; 146: e42–43.

Szafranski P, Dharmadhikari AV, Wambach JA, Towe CT, White FV, Grady RM, Eghtesady P, Cole FS, Deutsch G, Sen P, Stankiewicz P. Two deletions overlapping a distant FOXF1 enhancer unravel the role of lncRNA LINC01081 in etiology of alveolar capillary dysplasia with misalignment of pulmonary veins. American journal of medical genetics Part A 2014; 164A: 2013–2019.

A term male infant developed tachypnea at birth, was treated with oxygen, and then discharged home on room air. He was also noted to have an inguinal hernia at birth. During the first few months of life, he experienced several episodes of pulmonary congestion attributed to upper respiratory tract infections before presenting on day of life (DOL) 109 with respiratory distress and severe pulmonary hypertension that required mechanical ventilation, vasopressor support, pulmonary vasodilators, and veno-arterial extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) for 8 days. He remained mechanically ventilated until bilateral lung transplant on DOL 139. He did well post-transplant for several years before developing bronchiolitis obliterans that led to a second transplant at 5 years of age. Two months after his second transplant, he developed progressive renal failure and died.

Infant #2

A term male infant developed neonatal respiratory distress and was treated with supplemental oxygen and continuous positive airway pressure on DOL 2. An echocardiogram demonstrated pulmonary hypertension. He was also noted to have non-obstructive posterior urethral valves. Due to persistent oxygen requirement at 1 month of age, he underwent open lung biopsy which was diagnostic for ACDMPV. At 2 months of age, a cardiac catheterization demonstrated suprasystemic right heart pressures that were mildly responsive to inhaled nitric oxide. He was discharged home on nasal cannula oxygen (0.5 liters per minute (LPM)) and nitric oxide (0.5 LPM, estimated 5 parts per million). His oxygen and nitric oxide requirements gradually increased, and his pulmonary hypertension worsened prompting bilateral lung transplantation at 21 months. He did well until 4 years when he required a second transplant for chronic lung allograft dysfunction due to rejection. He is alive at 16 years of age with bronchiolitis obliterans. Most recent (15 years) spirometry revealed forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) of 31% predicted, forced vital capacity (FVC) of 40% predicted, and FEV1/FVC of 68% indicating airflow obstruction (no response in FEV1 to bronchodilator therapy). Total lung capacity (TLC) was 2.29L (60% predicted) and residual volume (RV) was 0.99 (111% predicted) with RV/TLC of 43% indicating air trapping. Diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO) was 67% predicted.

Infant #3

A female infant born at 36 weeks’ gestation had no neonatal respiratory symptoms or congenital anomalies, but had a male sibling who died after lung transplantation for ACDMPV. She presented on DOL 71 with respiratory distress, cyanosis, and pulmonary hypertension by echocardiogram and was treated with mechanical ventilation, vasopressor support, and pulmonary vasodilators. She required mechanical ventilation until transplant on DOL 159 and is alive with normal lung function at 14 years of age. Most recent (age 14 years) spirometry was essentially normal (FEV1 90% predicted, FVC 86% predicted, and FEV1/FVC 90%). TLC was 4.66L (110% predicted) and RV was 1.71L (154% predicted) with RV/TLC ratio of 37%, suggestive of mild air trapping. DLCO was normal.

Infant #4

A late preterm female infant born at 34 weeks’ gestation developed abdominal distension and intestinal dysmotility on DOL 3 which resolved during a 17 day NICU hospitalization. She did not have respiratory symptoms and remained on room air throughout her NICU course. Echocardiogram on DOL 20 showed no evidence of pulmonary hypertension. On DOL 67, she presented with severe respiratory distress, shock, and cardiopulmonary arrest and was resuscitated with intubation, mechanical ventilation, oxygen, and nitric oxide. A cardiac catheterization demonstrated suprasystemic right heart pressures that were mildly responsive to inhaled nitric oxide. An open lung biopsy was diagnostic for ACDMPV. She remained mechanically ventilated and underwent bilateral lung transplantation on DOL 159. She developed bronchiolitis obliterans and died at 9 years of age.

Infant #5 (previously reported)19

A late preterm female infant born at 34 weeks’ gestation was healthy at birth without respiratory symptoms. On DOL 24 she was briefly hospitalized for apnea that was attributed to gastroesophageal reflux which did not recur. On DOL 92, she was hospitalized for dehydration secondary to diarrhea and was found to be hypoxemic. Echocardiogram demonstrated pulmonary hypertension. She was treated with supplemental oxygen via nasal cannula and sildenafil until DOL 273 when an open lung biopsy was diagnostic for ACDMPV. Following the biopsy, she required veno-arterial ECMO before transitioning to support from a paracorporeal lung assist device.19 She underwent bilateral lung transplant on DOL 286 and is alive at 6 years of age. Most recent (6 years) spirometry was normal (FEV1 96% predicted, FVC 105% predicted, and FEV1/FVC 83%). TLC was 1.90L (94% predicted), RV was 0.51L (69% predicted) and RV/TLC was 27%. DLCO was normal.

Infant #617

This term female infant had transient tachypnea of the newborn with possible pneumonia.17 An echocardiogram revealed a patent ductus arteriosus without evidence of pulmonary hypertension. She was discharged from the NICU on supplemental oxygen on DOL 17 which was continued until DOL 21. Over the next 5 months, she had poor weight gain and persistent retractions. She presented with respiratory distress and hypoxemia on DOL 212 during travel at high altitude. Cardiac catheterization demonstrated near systemic right heart pressures that were responsive to inhaled nitric oxide. Open lung biopsy was diagnostic of ACDMPV. She was gradually weaned off supplemental oxygen and nitric oxide and was discharged on DOL 249 on sildenafil and furosemide. On DOL 423, she developed an upper respiratory tract infection with coronavirus and progressive hypoxemic respiratory failure and required veno-venous ECMO. She improved, was extubated, and received non-invasive positive pressure ventilation until bilateral lung transplant on DOL 464. During the 3 months after transplant, she had recurrent episodes of respiratory failure of unclear etiology and died at 18 months of age.

FOXF1 Sequencing and Assessment of Copy Number Variants

We obtained DNA from peripheral blood from 5 subjects (Subjects #2–6). DNA was not available for Subject 1. Two subjects had apparent non-mosaic missense variants in FOXF1 (c.146C>A: p.P49Q (subject 2) and c.377C>T: p.P126L (Subject 4))3 (Table 3). Both variants are novel and not present in the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC) database (exac.broadinstitute.org)20 and are predicted to be deleterious by in silico algorithms including SIFT, Polyphen, LRT, Mutation Taster, GERP++, and PhyloP in ANNOVAR (annovar.openbioinformatics.org)21 and CADD (cadd.gs.washington.edu/).22 Subject 6 had an apparent non-mosaic a 1.5Mb CNV deletion mapping 306kb upstream to FOXF1 that removed 26kb of the proximal portion of the FOXF1 enhancer region.17 Parental DNA sequencing for subjects 2 and 6 revealed that both the c.146C>A point mutation and the 1.5Mb CNV deletion arose de novo. No point mutations or CNV deletions involving FOXF1 were identified in subject 3 who had a sibling with ACDMPV, nor in Subject 5.

Table 3. Histology of Lung Explants for Infants with Atypical Presentations of ACDMPV.

Histologic assessment focused on areas of congested, non-collapsed lung, in which architecture and capillaries were well visualized.

| Infant | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deficient capillarization of alveoli | Mixed | Focal | Focal | Focal | Mixed | Mixed |

| Malposition of pulmonary veins | Patchy | Focal | Focal | Focal | Patchy | Patchy |

| Medial hypertrophy of small arteries and arterioles | Moderate to marked | Moderate | Moderate to marked | Moderate to marked | Moderate to marked | Moderate to marked |

| Lobular maldevelopment | Suggestive | Suggestive | Present | Present | Suggestive | Suggestive |

| Lymphangiectas is | Interlobular and bronchovascular bundles | Interlobular and bronchovascular bundles | Interlobular | Interlobular | Interlobular | Interlobular and bronchovascular bundles |

| FOXF1 Sequencing | DNA not available | P49Q (1) | No point mutations or deletions identified | P126L (1) | No point mutations or deletions identified | 1.5Mb deletion upstream of FOXF1 (2) |

Sen P, Yang Y, Navarro C, Silva I, Szafranski P, Kolodziejska KE, et al. Novel FOXF1 mutations in sporadic and familial cases of alveolar capillary dysplasia with misaligned pulmonary veins imply a role for its DNA binding domain. Human mutation. 2013;34(6):801–11.

Szafranski P, Dharmadhikari AV, Wambach JA, Towe CT, White FV, Grady RM, et al. Two deletions overlapping a distant FOXF1 enhancer unravel the role of lncRNA LINC01081 in etiology of alveolar capillary dysplasia with misalignment of pulmonary veins. American journal of medical genetics Part A. 2014;164A(8):2013–9.

Explant Histology

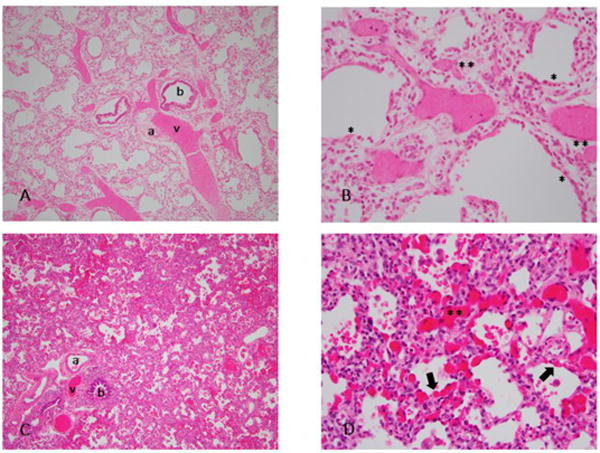

All 6 lung explants demonstrated the histologic features diagnostic of ACDMPV (Table 3, Figure). The main findings of deficient capillarization and malpositioned pulmonary veins were focal or patchy as compared with infants with classic ACDMPV (Table 4). All explants demonstrated moderate to marked medial wall thickening of the small pulmonary arteries and arterioles consistent with the clinical histories of pulmonary hypertension. Lymphangiectasis was present in all explant specimens, including subjects #2 and #6 who were not mechanically ventilated at the time of transplant. Although lobular maldevelopment with deficient alveolarization was diffuse and readily observed in all infants with classic ACDMPV, the explanted lung of infants with atypical ACDMPV were more heterogeneous. Two of the explants (subjects #3 and #4) had focal areas with definite deficient alveolarization as well as other areas suggestive of maldevelopment. The other 4 atypical ACDMPV explants had focal areas suggestive of deficient alveolarization. Findings consistent with secondary remodeling were also present in the explanted lungs. There were no obvious differences in explant histopathology among infants with or without FOXF1 point mutations or CNV deletions.

Figure 1. A–D: Histology from infants with classic and atypical presentations of ACDMPV.

Hematoxylin and eosin stained sections of lung with low (10×) and high (40×) power views of classic ACDMPV (A,B) and atypical ACDMPV (C,D). Congested areas were selected for better visualization of the capillaries. A: Malposition of veins adjacent to small arteries within bronchovascular bundles (BVBs) and lobular maldevelopment with decreased alveolarization. B: Almost complete absence of capillary loops adjacent to alveolar epithelium (*), with fewer and displaced capillaries in septae (**). C: Malposition of veins adjacent to small arteries in BVBs. Compared to histology of classic ACDMPV, decreased alveolarization is not readily apparent. D: Areas of both normal capillarization with capillaries adjacent to alveolar epithelium (arrow), and deficient capillarization with displaced capillaries in septae (**). v=vein, a=artery, b=bronchus

Table 4. Histology from Autopsies of Infants with Classic Presentation of ACDMPV.

Histologic assessment focused on areas of congested, non-collapsed lung, in which architecture and capillaries were well visualized.

| Infant | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Presentation | Birth | Birth | 1 day |

| Age at Death | 15 days | 9 days | 8 days |

| Deficient capillarization of alveoli | Extensive | Extensive | Extensive |

| Malposition of pulmonary veins | Extensive | Extensive | Extensive |

| Medial hypertrophy of small arteries and arterioles | Mild | Mild | Mild |

| Lobular maldevelopment | Definite | Definite | Definite |

| Lymphangiectasis | Diffuse, interlobular | Diffuse, interlobular | Diffuse, interlobular |

Discussion

Delayed presentations of ACDMPV after the neonatal period 4–9 or with prolonged survival8, 9, 23, 24 suggest biologically and developmentally diverse mechanisms contribute to disease presentation. In contrast to the classic neonatal presentation of ACDMPV, only 3 subjects (#1, 2, 6) had respiratory symptoms in the newborn period. Two infants (#1, #6) were treated with nasal cannula oxygen which was discontinued by 3 weeks of life, and then presented with fulminant symptoms at 3 months and 7 months, respectively. The third infant (subject #2) had a persistent oxygen requirement and echocardiographic evidence of pulmonary hypertension which prompted diagnostic lung biopsy at 1 month of age. Although this infant had the earliest presentation, biopsy, and diagnosis, he underwent lung transplant at the oldest age (633 days) and required the least respiratory support at the time of transplant (supplemental nasal cannula oxygen and nitric oxide). His explant histology demonstrated focal findings which may have contributed to his comparatively indolent course. The remaining 3 subjects had no significant respiratory symptoms within the first 2–3 months of life, including the infant with a family history of ACDMPV (Subject #3). Because of the wide variability and timing of presentations, atypical ACDMPV should remain in the differential diagnosis of any infant with hypoxemia and idiopathic pulmonary hypertension.

The histopathologic characteristics of capillary dysplasia and misaligned pulmonary veins ranged from focal to patchy in the explanted lungs but did not correlate with the age of fulminant presentation or the presence of FOXF1 point mutations or CNV deletion. Although our study is limited in that explant histology may be confounded by differences in pre-transplant treatment (mechanical ventilation, prolonged oxygen exposure) and chronologic age, the non-uniformity of histopathologic characteristics suggests that disruption of lung development in this disease is location-specific and may be influenced by the local cellular and growth factor milieu. It is important to note that all 6 explants had areas of lung with normal capillary loops, a finding which illustrates the challenge of making a diagnosis of ACDMPV on a single specimen lung biopsy for patients with atypical presentations. As point mutations or CNV deletions that involve FOXF1 are present in approximately 80–90% of infants with classic ACDMPV 10 and 3 of 5 infants tested in our series, diagnostic sequencing of FOXF1 may preclude the need for lung biopsy.25 Failure to identify FOXF1 point mutations or CNV deletions in 2 of the 5 subjects tested suggests that other genes may contribute to or modify the ACDMPV phenotype.10

All 6 infants in our series had clinical and histologic evidence for significant pulmonary hypertension. Medial wall hypertrophy, while present, was less pronounced among the 3 infants with classic ACDMPV (Table 4). It is unclear whether this difference reflects a primary process related to endothelial cell proliferation or is secondary to therapies or chronic/prolonged disruption of the pulmonary vascular bed. For 5 atypical ACDMPV infants, the severity of their pulmonary hypertension contributed to the eventual need for intensive medical and mechanical respiratory support prior to transplant. Presumably, their pulmonary hypertension resulted from anatomically fixed, decreased number of pulmonary capillaries within the alveolar epithelium, misaligned pulmonary veins, and abnormal lobular development. Although neonates with classic ACDMPV typically have transient but non-sustained responses to pulmonary vasodilators,1 3 atypical ACDMPV infants (#2, 4, 6) demonstrated reduction in pulmonary resistance with inhaled nitric oxide administration during cardiac catheterization and successful treatment of all 6 infants with pulmonary vasodilators suggests pharmacologically reversible components of pulmonary hypertension. However, our study was not specifically designed to determine the effects of these therapies thereby limiting this finding. The utility of these medications among infants with atypical ACDMPV compared with classic ACDMPV may in part reflect the heterogeneous nature of their disease or the diversity of the underlying biologic or developmental mechanisms.

Five infants in our series had chest CT scans which demonstrated findings of ILD with ground glass opacities and septal thickening. In contrast to infants with atypical ACDMPV, infants with idiopathic primary pulmonary hypertension typically are not hypoxemic without a significant intracardiac shunt and usually do not have abnormalities of the pulmonary parenchyma on chest CT.26 Infants with biallelic loss of function mutations in surfactant proteins (SFTPB, ABCA3) typically present with severe neonatal respiratory distress syndrome and have chest radiograph findings consistent with surfactant deficiency.27 Infants with dominant point mutations in SFTPC or missense variants in ABCA3 can present beyond the newborn period with childhood interstitial lung disease (chILD) and pulmonary hypertension, which when present, is associated with increased mortality.28 The presentation of pulmonary veno-occlusive disease (PVOD) and pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis (PCH) with hypoxemia, pulmonary hypertension, and abnormal CT scan results (patchy centrilobular pattern of ground glass opacities, pavement appearance to lobules) can make differentiation from ACDMPV potentially difficult. Due to the wide variability and timing of presentations, atypical ACDMPV should remain in the differential diagnosis of any infant with hypoxemia and idiopathic pulmonary hypertension including those with chest CT findings of ILD; clinical testing of FOFX1 in these patients may be diagnostic.

Although lung transplant is a recognized therapy for children with end-stage lung disease,29 successful transplant for ACDMPV is limited to two case reports.17, 19 In a large international registry, median survival of all children after lung transplant is 5.3 years, with infants’ having a slightly better median survival of 6.4 years.30 The mortality and outcomes of the patients transplanted for ACDMPV in our series are comparable with infants and children transplanted for genetic disorders of surfactant metabolism at our institution.31 Prospective studies such as those being performed through the childhood interstitial lung disease research network (chILDRN) are needed to identify genetic, therapeutic, or environmental factors that contribute to delayed presentation or prolonged survival without transplant.32

Acknowledgments

We thank the families for their participation in these research studies and the referring physicians. We thank the Exome Aggregation Consortium and the groups that provided exome variant data for comparison; a full list of contributing groups can be found at http://exac.broadinstitute.org/about)

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (T32 HL007873 [C.T.], K08 HL105891 [J.W.], K12 HL120002 [F.C.], R01 HL065174 [F.C.], R21/R33 HL120760 [F.C.]), R01 HL137203 and HL101975 (P.St.), American Lung Association (J.W.), American Thoracic Society (J.W.), Children’s Discovery Institute (F.C. and J.W.), and National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD 2016) (P.Sz.)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bishop NB, Stankiewicz P, Steinhorn RH. Alveolar capillary dysplasia. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2011;184:172–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201010-1697CI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Janney CG, Askin FB, Kuhn C., 3rd Congenital alveolar capillary dysplasia–an unusual cause of respiratory distress in the newborn. American journal of clinical pathology. 1981;76:722–7. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/76.5.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sen P, Yang Y, Navarro C, Silva I, Szafranski P, Kolodziejska KE, Dharmadhikari AV, Mostafa H, Kozakewich H, Kearney D, Cahill JB, Whitt M, Bilic M, Margraf L, Charles A, Goldblatt J, Gibson K, Lantz PE, Garvin AJ, Petty J, Kiblawi Z, Zuppan C, McConkie-Rosell A, McDonald MT, Peterson-Carmichael SL, Gaede JT, Shivanna B, Schady D, Friedlich PS, Hays SR, Palafoll IV, Siebers-Renelt U, Bohring A, Finn LS, Siebert JR, Galambos C, Nguyen L, Riley M, Chassaing N, Vigouroux A, Rocha G, Fernandes S, Brumbaugh J, Roberts K, Ho-Ming L, Lo IF, Lam S, Gerychova R, Jezova M, Valaskova I, Fellmann F, Afshar K, Giannoni E, Muhlethaler V, Liang J, Beckmann JS, Lioy J, Deshmukh H, Srinivasan L, Swarr DT, Sloman M, Shaw-Smith C, van Loon RL, Hagman C, Sznajer Y, Barrea C, Galant C, Detaille T, Wambach JA, Cole FS, Hamvas A, Prince LS, Diderich KE, Brooks AS, Verdijk RM, Ravindranathan H, Sugo E, Mowat D, Baker ML, Langston C, Welty S, Stankiewicz P. Novel FOXF1 mutations in sporadic and familial cases of alveolar capillary dysplasia with misaligned pulmonary veins imply a role for its DNA binding domain. Human mutation. 2013;34:801–11. doi: 10.1002/humu.22313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmed S, Ackerman V, Faught P, Langston C. Profound hypoxemia and pulmonary hypertension in a 7-month-old infant: late presentation of alveolar capillary dysplasia. Pediatric critical care medicine : a journal of the Society of Critical Care Medicine and the World Federation of Pediatric Intensive and Critical. Care Societies. 2008;9:e43–6. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31818e383e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Michalsky MP, Arca MJ, Groenman F, Hammond S, Tibboel D, Caniano DA. Alveolar capillary dysplasia: a logical approach to a fatal disease. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:1100–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.03.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shankar V, Haque A, Johnson J, Pietsch J. Late presentation of alveolar capillary dysplasia in an infant. Pediatric critical care medicine : a journal of the Society of Critical Care Medicine and the World Federation of Pediatric Intensive and Critical. Care Societies. 2006;7:177–9. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000202570.58016.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdallah HI, Karmazin N, Marks LA. Late presentation of misalignment of lung vessels with alveolar capillary dysplasia. Crit Care Med. 1993;21:628–30. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199304000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kodama Y, Tao K, Ishida F, Kawakami T, Tsuchiya K, Ishida K, Takemura T, Nakazawa A, Matsuoka K, Yoda H. Long survival of congenital alveolar capillary dysplasia patient with NO inhalation and epoprostenol: effect of sildenafil, beraprost and bosentan. Pediatr Int. 2012;54:923–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2012.03712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ito Y, Akimoto T, Cho K, Yamada M, Tanino M, Dobata T, Kitaichi M, Kumaki S, Kinugawa Y. A late presenter and long-term survivor of alveolar capillary dysplasia with misalignment of the pulmonary veins. Eur J Pediatr. 2015;174:1123–6. doi: 10.1007/s00431-015-2543-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Szafranski P, Gambin T, Dharmadhikari AV, Akdemir KC, Jhangiani SN, Schuette J, Godiwala N, Yatsenko SA, Sebastian J, Madan-Khetarpal S, Surti U, Abellar RG, Bateman DA, Wilson AL, Markham MH, Slamon J, Santos-Simarro F, Palomares M, Nevado J, Lapunzina P, Chung BH, Wong WL, Chu YW, Mok GT, Kerem E, Reiter J, Ambalavanan N, Anderson SA, Kelly DR, Shieh J, Rosenthal TC, Scheible K, Steiner L, Iqbal MA, McKinnon ML, Hamilton SJ, Schlade-Bartusiak K, English D, Hendson G, Roeder ER, DeNapoli TS, Littlejohn RO, Wolff DJ, Wagner CL, Yeung A, Francis D, Fiorino EK, Edelman M, Fox J, Hayes DA, Janssens S, De Baere E, Menten B, Loccufier A, Vanwalleghem L, Moerman P, Sznajer Y, Lay AS, Kussmann JL, Chawla J, Payton DJ, Phillips GE, Brosens E, Tibboel D, de Klein A, Maystadt I, Fisher R, Sebire N, Male A, Chopra M, Pinner J, Malcolm G, Peters G, Arbuckle S, Lees M, Mead Z, Quarrell O, Sayers R, Owens M, Shaw-Smith C, Lioy J, McKay E, de Leeuw N, Feenstra I, Spruijt L, Elmslie F, Thiruchelvam T, Bacino CA, Langston C, Lupski JR, Sen P, Popek E, Stankiewicz P. Pathogenetics of alveolar capillary dysplasia with misalignment of pulmonary veins. Human genetics. 2016;135:569–86. doi: 10.1007/s00439-016-1655-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sen P, Thakur N, Stockton DW, Langston C, Bejjani BA. Expanding the phenotype of alveolar capillary dysplasia (ACD) The Journal of pediatrics. 2004;145:646–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.06.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Langston C. Misalignment of pulmonary veins and alveolar capillary dysplasia. Pediatric pathology / affiliated with the International Paediatric Pathology Association. 1991;11:163–70. doi: 10.3109/15513819109064753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deutsch GH, Young LR, Deterding RR, Fan LL, Dell SD, Bean JA, Brody AS, Nogee LM, Trapnell BC, Langston C, Pathology Cooperative G. Albright EA, Askin FB, Baker P, Chou PM, Cool CM, Coventry SC, Cutz E, Davis MM, Dishop MK, Galambos C, Patterson K, Travis WD, Wert SE, White FV, Ch ILDRC-o Diffuse lung disease in young children: application of a novel classification scheme. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2007;176:1120–8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200703-393OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lally KP, Breaux CW., Jr A second course of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in the neonate–is there a benefit? Surgery. 1995;117:175–8. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(05)80082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Melly L, Sebire NJ, Malone M, Nicholson AG. Capillary apposition and density in the diagnosis of alveolar capillary dysplasia. Histopathology. 2008;53:450–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2008.03134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan MS, Heinle JS, Samayoa AX, Adachi I, Schecter MG, Mallory GB, Morales DL. Is lung transplantation survival better in infants? Analysis of over 80 infants. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation : the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 2013;32:44–9. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2012.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szafranski P, Dharmadhikari AV, Wambach JA, Towe CT, White FV, Grady RM, Eghtesady P, Cole FS, Deutsch G, Sen P, Stankiewicz P. Two deletions overlapping a distant FOXF1 enhancer unravel the role of lncRNA LINC01081 in etiology of alveolar capillary dysplasia with misalignment of pulmonary veins. American journal of medical genetics Part A. 2014;164A:2013–9. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Langston C, Dishop MK. Diffuse lung disease in infancy: a proposed classification applied to 259 diagnostic biopsies. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2009;12:421–37. doi: 10.2350/08-11-0559.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boston US, Fehr J, Gazit AZ, Eghtesady P. Paracorporeal lung assist device: an innovative surgical strategy for bridging to lung transplant in an infant with severe pulmonary hypertension caused by alveolar capillary dysplasia. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;146:e42–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV, Samocha KE, Banks E, Fennell T, O’Donnell-Luria AH, Ware JS, Hill AJ, Cummings BB, Tukiainen T, Birnbaum DP, Kosmicki JA, Duncan LE, Estrada K, Zhao F, Zou J, Pierce-Hoffman E, Berghout J, Cooper DN, Deflaux N, DePristo M, Do R, Flannick J, Fromer M, Gauthier L, Goldstein J, Gupta N, Howrigan D, Kiezun A, Kurki MI, Moonshine AL, Natarajan P, Orozco L, Peloso GM, Poplin R, Rivas MA, Ruano-Rubio V, Rose SA, Ruderfer DM, Shakir K, Stenson PD, Stevens C, Thomas BP, Tiao G, Tusie-Luna MT, Weisburd B, Won HH, Yu D, Altshuler DM, Ardissino D, Boehnke M, Danesh J, Donnelly S, Elosua R, Florez JC, Gabriel SB, Getz G, Glatt SJ, Hultman CM, Kathiresan S, Laakso M, McCarroll S, McCarthy MI, McGovern D, McPherson R, Neale BM, Palotie A, Purcell SM, Saleheen D, Scharf JM, Sklar P, Sullivan PF, Tuomilehto J, Tsuang MT, Watkins HC, Wilson JG, Daly MJ, MacArthur DG, Exome Aggregation C Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature. 2016;536:285–91. doi: 10.1038/nature19057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kircher M, Witten DM, Jain P, O’Roak BJ, Cooper GM, Shendure J. A general framework for estimating the relative pathogenicity of human genetic variants. Nat Genet. 2014;46:310–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.2892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Licht C, Schickendantz S, Sreeram N, Arnold G, Rossi R, Vierzig A, Mennicken U, Roth B. Prolonged survival in alveolar capillary dysplasia syndrome. Eur J Pediatr. 2004;163:181–2. doi: 10.1007/s00431-003-1385-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shehata BM, Abramowsky CR. Alveolar capillary dysplasia in an infant with trisomy 21. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2005;8:696–700. doi: 10.1007/s10024-005-2137-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurland G, Deterding RR, Hagood JS, Young LR, Brody AS, Castile RG, Dell S, Fan LL, Hamvas A, Hilman BC, Langston C, Nogee LM, Redding GJ, American Thoracic Society Committee on Childhood Interstitial Lung D, the ch ILDRN An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline: classification, evaluation, and management of childhood interstitial lung disease in infancy. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2013;188:376–94. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201305-0923ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abman SH, Hansmann G, Archer SL, Ivy DD, Adatia I, Chung WK, Hanna BD, Rosenzweig EB, Raj JU, Cornfield D, Stenmark KR, Steinhorn R, Thebaud B, Fineman JR, Kuehne T, Feinstein JA, Friedberg MK, Earing M, Barst RJ, Keller RL, Kinsella JP, Mullen M, Deterding R, Kulik T, Mallory G, Humpl T, Wessel DL, American Heart Association Council on Cardiopulmonary CCP, Resuscitation, Council on Clinical C, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Y, Council on Cardiovascular R, Intervention, Council on Cardiovascular S, Anesthesia, the American Thoracic S Pediatric Pulmonary Hypertension: Guidelines From the American Heart Association and American Thoracic Society. Circulation. 2015;132:2037–99. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wambach JA, Casey AM, Fishman MP, Wegner DJ, Wert SE, Cole FS, Hamvas A, Nogee LM. Genotype-phenotype correlations for infants and children with ABCA3 deficiency. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2014;189:1538–43. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201402-0342OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fan LL, Dishop MK, Galambos C, Askin FB, White FV, Langston C, Liptzin DR, Kroehl ME, Deutsch GH, Young LR, Kurland G, Hagood J, Dell S, Trapnell BC, Deterding RR, Children’s I, Diffuse Lung Disease Research N Diffuse Lung Disease in Biopsied Children 2 to 18 Years of Age. Application of the chILD Classification Scheme. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12:1498–505. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201501-064OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palomar LM, Nogee LM, Sweet SC, Huddleston CB, Cole FS, Hamvas A. Long-term outcomes after infant lung transplantation for surfactant protein B deficiency related to other causes of respiratory failure. The Journal of pediatrics. 2006;149:548–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldfarb SB, Benden C, Edwards LB, Kucheryavaya AY, Dipchand AI, Levvey BJ, Lund LH, Meiser B, Rossano JW, Yusen RD, Stehlik J. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Eighteenth Official Pediatric Lung and Heart-Lung Transplantation Report–2015; Focus Theme: Early Graft Failure. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation : the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 2015;34:1255–63. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eldridge WB, Zhang Q, Faro A, Sweet SC, Eghtesady P, Hamvas A, Cole FS, Wambach JA. Outcomes of Lung Transplantation for Infants and Children with Genetic Disorders of Surfactant Metabolism. The Journal of pediatrics. 2017;184:157–64 e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Young LR, Trapnell BC, Mandl KD, Swarr DT, Wambach JA, Blaisdell CJ. Accelerating Scientific Advancement for Pediatric Rare Lung Disease Research. Report from a National Institutes of Health-NHLBI Workshop, September 3 and 4, 2015. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13:385–93. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201605-402OT. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]