Abstract

Rift Valley fever (RVF) is a mosquito-borne zoonotic disease endemic to Africa which affects both ruminants and humans. RVF causes serious damage to the livestock industry and is also a threat to public health. The Rift Valley fever virus has a segmented negative-stranded RNA genome consisting of Large (L)-, Medium (M)-, and Small (S)-segments. The live-attenuated MP-12 vaccine is immunogenic in livestock and humans, and is conditionally licensed for veterinary use in the U.S. The MP-12 strain encodes 23 mutations (nine amino acid substitutions) and is attenuated through a combination of mutations in the L-, M-, and S-segments. Among them, the M-U795C, M-A3564G, and L-G3104A mutations contribute to viral attenuation through the L- and M-segments. The M-U795C, M-A3564G, L-U533C, and L-G3750A mutations are also independently responsible for temperature-sensitive (ts) phenotype. We hypothesized that a serial passage of the MP-12 vaccine in culture cells causes reversions of the MP-12 genome. The MP-12 vaccine and recombinant rMP12-ΔNSs16/198 were serially passaged 25 times. Droplet digital PCR analysis revealed that the reversion occurred at L-G3750A during passages of MP-12 in Vero or MRC-5 cells. The reversion also occurred at M-A3564G and L-U533C of rMP12-ΔNSs16/198 in Vero cells. Reversion mutations were not found in MP-12 or the variant, rMP12-TOSNSs, in the brains of mice with encephalitis. This study characterized genetic stability of the MP-12 vaccine and the potential risk of reversion mutation at the L-G3750A ts mutation after excessive viral passages in culture cells.

Keywords: Rift Valley fever virus, MP-12 vaccine, attenuation mutations, droplet digital PCR, reverse genetics

Introduction

Rift Valley fever virus (RVFV) is a high consequence zoonotic pathogen that is classified as a Category A priority pathogen by the National Institute of Health (NIH), and an overlap select agent by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Service and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA)1–3. Rift Valley fever (RVF) is endemic to sub-Saharan Africa, but has spread into Egypt, Madagascar, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen4–6. RVFV is transmitted by mosquitoes, and causes high rates of abortion and fetal malformation in pregnant ruminants7,8. Transmission of RVFV to humans occurs through exposure to the bodily fluids of infected animals, or from the bite of an infected mosquito8. The majority of RVF patients have self-limiting febrile illness or are asymptomatic, and the estimated mortality rate is less than 3.0%9. In contrast, higher mortality rates have been reported among hospitalized RVF patients with severe clinical manifestations, such as hemorrhage, jaundice, neurological disorders, or blindness10,11. Vaccination is an effective measure by which to prevent RVFV spread, both in endemic and non-endemic countries. In the U.S., a formalin-inactivated RVF vaccine (TSI-GSD-200) and the live-attenuated MP-12 vaccine are Investigational New Drugs, and have been tested in human clinical trials12–15. The MP-12 vaccine received a conditional license for veterinary use from the USDA since 2013, and the master-seed stock has been generated by Zoetis, Inc.16. Vaccine lots of the MP-12 vaccine must be prepared on a large scale in case of RVF outbreak16; therefore, an understanding of the genetic stability of the MP-12 vaccine during serial viral passages in culture cells is important.

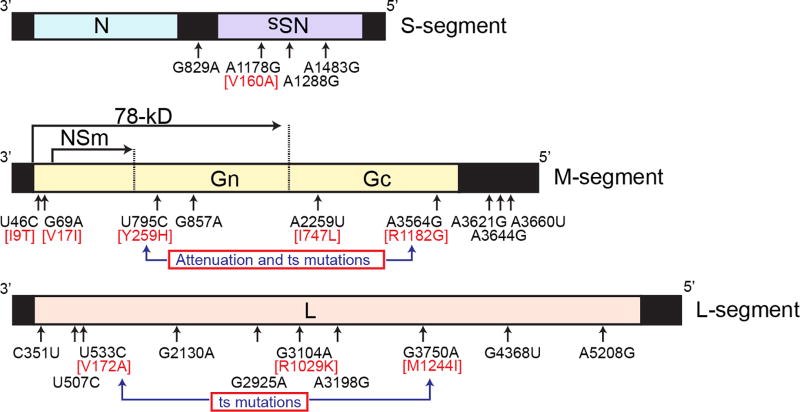

RVFV belongs to the genus Phlebovirus in the family Bunyaviridae, and its negative-stranded RNA genome is comprised of Large (L)-, Medium (M)-, and Small (S)-segments17. The S-segment is ambisense; a negative-sense S-segment RNA encodes nucleoprotein (N protein) mRNA and a positive-sense S-segment RNA encodes nonstructural protein (NSs protein) mRNA. The M-segment encodes 78kD, NSm, Gn, and Gc proteins in a single open-reading frame (ORF), and these proteins are co-translationally cleaved from precursor proteins18,19. The L-segment encodes an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (L protein). The MP-12 strain encodes 23 unique genetic mutations (Fig. 1): four mutations in the untranslated region (UTR), 10 silent mutations, and nine amino acid substitutions. The MP-12 vaccine is attenuated through a combination of mutations in the L-, M-, and S-segments20. Mutations Gn-U795C (Y259H) and Gc-A3564G (R1182G) independently contribute to the partial attenuation of MP-12 strain through the M-segment, and a combination of mutations Gn-U795C (Y259H), Gc-A3564G (R1182G), and L-G3104A (R1029K) is sufficient to abolish the virulence of ZH501 strain in mice. Temperature-sensitive (ts) mutations were also identified for the MP-12 strain21. MP-12 replication was restricted at 38°C and above in Vero and MRC-5 cells. The L-, M-, and S-segments independently contribute to the ts phenotype of MP-12, and two mutations in the M-segment (Gn-U795C [Y259H] and Gc-A3564G [R1182G]) and two mutations in the L-segment (L-U533C [V172A] and L-G3750A [M1244I]) are independently responsible for the ts phenotype (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Schematics of MP-12 vaccine mutations.

The genomic RNA of Small (S)-, Medium (M)-, and Large (L)-segments are shown. Mutations of the MP-12 vaccine compared to the parental ZH548 strain are indicated by arrows, and amino acid substitutions are shown in red. Reported attenuation mutations in the M-segment and temperature-sensitive (ts) mutations in the M- and L-segments are also shown.

The genetic stability of the MP-12 vaccine has been previously evaluated. Through a high throughput sequencing approach, MP-12 vaccine Lot-7-2-88 has been shown to not contain detectable genetic subpopulations encoding the parental ZH548 strain sequence at its 23 mutation sites, which are unique to the MP-12 strain22. MP-12 isolates from human plasma or buffy coats after vaccination have also been genetically characterized15. Ten mutations were identified in seven isolates, but none of them were reversion mutations to the parental ZH548 strain. To date, there is no evidence of reversion in the MP-12 vaccine lot or human isolates.

Considering the plasticity of the RNA virus genome, due to an error-prone RNA polymerase, the MP-12 vaccine could revert to the parental RVFV sequence during multiple cycles of viral replications. For example, MP-12 RNA synthesis is decreased at 37°C due to the L-G3750A (M1244I) ts mutation21. If a reversion mutation occurs by chance, the viral genetic subpopulation could be replaced due to the above-mentioned disadvantage in viral RNA synthesis. To address this possibility, the MP-12 vaccine Lot-7-2-88 was serially passaged in MRC-5 cells or Vero cells. Reversion mutations at five selected mutation sites (Gn-U795C [Y259H], Gc-A3564G [R1182G], L-U533C [V172A], L-G3104A [R1029K], and G3750A [M1244I]) were quantitatively analyzed by droplet digital PCR (ddPCR). We also hypothesized that the mutant rMP12-ΔNSs16/198, which lacks functional NSs, is genetically less stable than parental MP-12 in Vero cells. RVFV NSs causes the cessation of cellular general transcription, including the interferon (IFN)-β gene, and promotes posttranslational degradation of dsRNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR) and transcription factor (TF) IIH23. Without NSs expression, host selection pressure would be expected to increase due to the presence of endogenous active PKR or active host transcription. We also determined if replication of the MP-12 strain causes reversion at any of those five mutation sites in mice, using viral RNA extracted from brains of mice suffering viral encephalitis after infection with MP-12 or a recombinant MP-12 strain encoding the Toscana virus (TOSV) NSs gene in the place of the MP-12 NSs gene (rMP12-TOSNSs)24.

Results

Reversion mutations in MP-12 and rMP12-ΔNSs16/198 during viral passages in culture cells

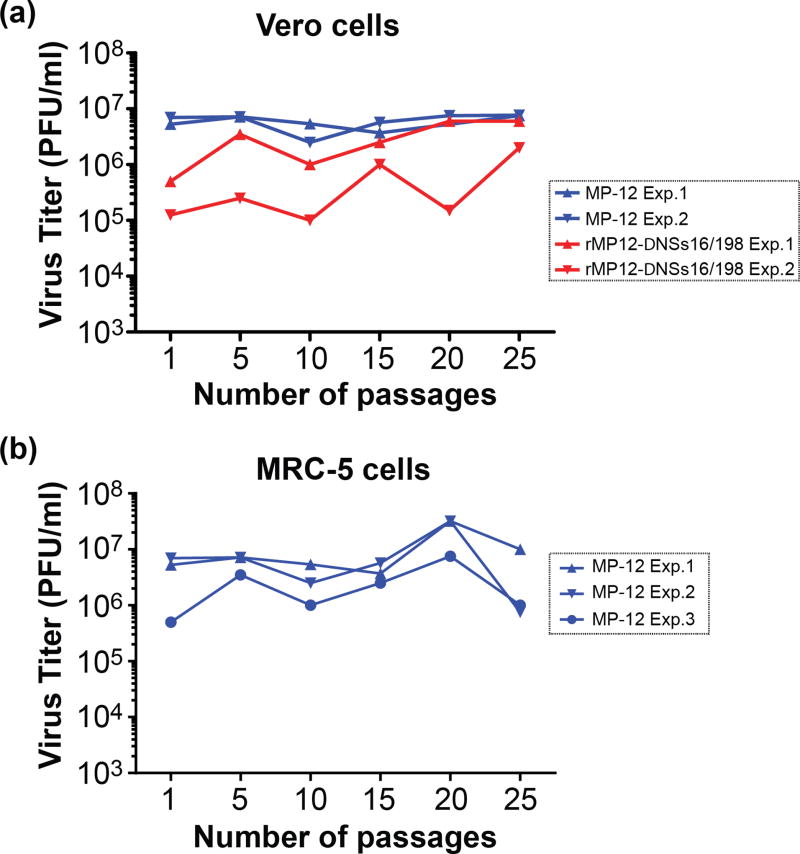

The MP-12 vaccine Lot-7-2-88 was serially passaged 25 times in Vero cells. The deletion of the RVFV S-segment is known to occur during serial passages in BHK-21 cells (0.1 MOI)25, and high MOI passage of virus may also lead to the generation of defective interfering (DI) particles26. To minimize the generation of RVFV-encoding gene truncation, the MP-12 passage experiment was therefore designed not to exceed an MOI of 0.01 (Fig. 2). Back titration of culture supernatants at 1, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 passages estimated the MOI of each passage to be 0.00002 to 0.002. Similarly, the MP-12 vaccine Lot-7-2-88 was also serially passaged 25 times in MRC-5 cells.

Fig. 2. Virus titers during serial virus passages.

(a) Vero cells were infected with either MP-12 vaccine Lot-7-2-88 or rMP12-ΔNSs16/198 at MOI of 0.01 (two separate passage experiments under the same conditions: Exp-1 and 2). At 3 dpi, culture supernatants were collected, and 0.1 µl was used for the next passage in Vero cells (5×105 cells). Virus titers in culture supernatants at 3 dpi of passages 1, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 are shown in a graph. (b) Similarly, MRC-5 cells were infected with MP-12 vaccine Lot-7-2-88 (three separate passage experiments under the same conditions: Exp-1, 2, and 3), and virus titers were measured at passages 1, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25.

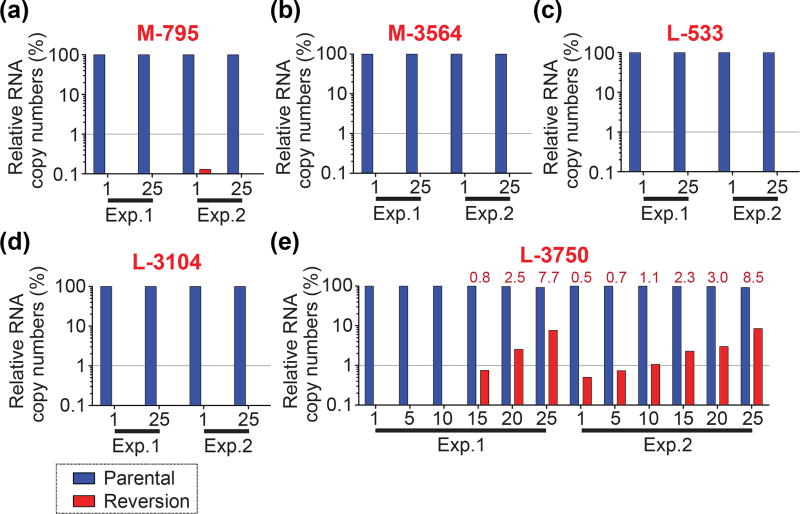

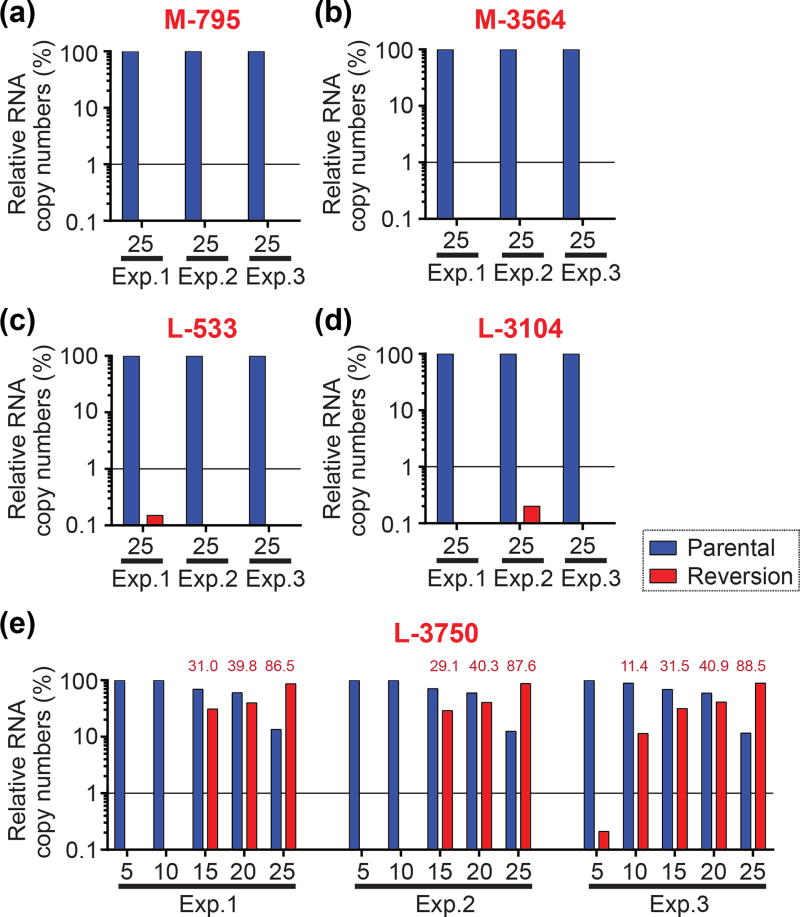

Five MP-12 mutations – M-795, M-3564, L-533, L-3104, and L-3750 – were analyzed for reversion due to their critical contribution to the attenuated or ts phenotypes20,21. The ddPCR analyses demonstrated that only one of the analyzed mutations showed reversion mutations exceeding 0.2% of the population during passaging (Fig. 3). As shown by the bars labelled in red in Fig. 3E, a genetic subpopulation encoding a reversion at L-3750 emerged at passage 15 in Exp-1 (0.8%) and at passage 1 in Exp-2 (0.5%), and gradually increased to 8% by passage 25 (Exp-1 and 2). In MRC-5 cells, the MP-12 vaccine also demonstrated no increases in genetic subpopulations encoding reversions in M-795, M-3564, L-533, or L-3104 exceeding 0.2% (Fig. 4); however, as shown by the bars labelled in red in Fig. 4E, a reversion at L-3750 occurred at passage 15 (31% of population in Exp-1; 29%, Exp-2) or passage 10 (11%, Exp-3), and the reversion population became dominant at passage 25 (87 – 89%). Taken together, these results demonstrated that L-3750 can be reverted during passages in Vero or MRC-5 cells, and the domination of the L-3750 reversion mutant occurs faster in MRC-5 cells than in Vero cells.

Fig. 3. Detection of reversion mutants of the MP-12 vaccine during viral passages in Vero cells.

The MP-12 vaccine was passaged 25 times in Vero cells at MOI of 0.01 or less at three days post infection. Virus RNA was purified from culture supernatants and analyzed for the presence of reversion mutations using Taqman probes (shown in Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 2). (a) M-segment nt. 795: HEX-795-C and FAM-795-T, (b) M-segment nt. 3564: HEX-3564-G and FAM-3564-A, (c) L-segment nt. 533: HEX-533-C and FAM-533-T, (d) L-segment nt. 3104: HEX-3104-A and FAM-3104-G, and (e) L-segment nt. 3750: HEX-3750-A and FAM-3750-G. Two independent studies are shown (Exp-1 and 2). Relative percentages of RNA copy numbers for parental and reversion mutants are shown in blue and red bars, respectively. The bar labels in red represent the percentages of reversion mutants.

Fig. 4. Detection of reversion mutants of the MP-12 vaccine during viral passages in MRC-5 cells.

The MP-12 vaccine was passaged 25 times in MRC-5 cells at MOI of 0.01 or less at three days post infection. Virus RNA was purified from culture supernatants and analyzed for the presence of reversion mutations using Taqman probes (shown in Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 2). (a) M-segment nt. 795: HEX-795-C and FAM-795-T, (b) M-segment nt. 3564: HEX-3564-G and FAM-3564-A, (c) L-segment nt. 533: HEX-533-C and FAM-533-T, (d) L-segment nt. 3104: HEX-3104-A and FAM-3104-G, and (e) L-segment nt. 3750: HEX-3750-A and FAM-3750-G. Three independent studies are shown (Exp-1, 2, and 3). Relative percentages of RNA copy numbers for parental and reversion mutants are shown in blue and red bars, respectively. The bar labels in red represent the percentages of reversion mutants.

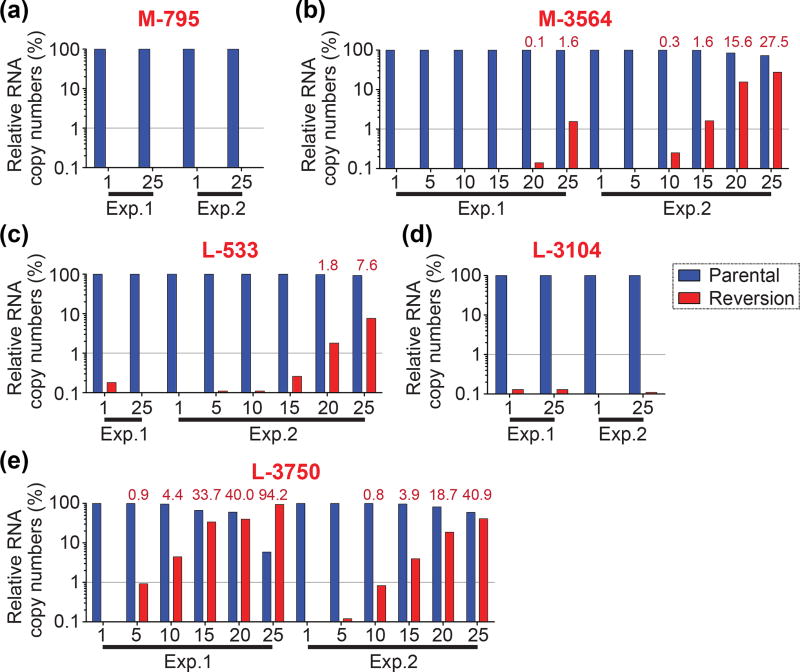

RVFV lacking a functional NSs can replicate efficiently in type-I IFN-incompetent cells, such as Vero or BHK-21 cells27–30, but less efficiently in type-I IFN-competent cells, such as MRC-5 cells29,30. In this study, RVFV lacking a functional NSs (rMP12-ΔNSs16/198) was passaged 25 times in Vero cells to investigate its genetic stability (Fig. 2). The ddPCR analysis revealed no reversion mutations at M-795 or L-3104 (Fig. 5A and D); however, as shown by the bars labelled in red in Fig. 5B, C, and E, reversions at M-3564 (2% of population, Exp-1 p25; 28%, Exp-2 p25), L-533 (8%, Exp-2 p25), and L-3750 (94%, Exp-1 p25; 41%, Exp-2 p25) were detected during 25 passages. To check the accuracy of ddPCR, the reversions of rMP12-ΔNSs16/198 (Exp-1) at M-3564 and L-3750 were further validated by MiSeq deep sequencing using PCR fragments (Exp-1, passage 25 sample). This analysis demonstrated the reversion of M-3564 in 5.7% of the population and L-3750 in 82.7%, which was consistent with our ddPCR results (Table 1). Conversely, variants encoding reversion mutations were not detectable at M-795 and L-3104. Thus, our results confirmed that replication of rMP12-ΔNSs16/198 leads to the reversion mutation at M-3564, L-533, and L-3750.

Fig. 5. Detection of reversion mutants of rMP12-ΔNSs16/198 during passages in Vero cells.

Recombinant MP-12 encoding a 69% in-frame truncation of NSs open reading frame (rMP12-ΔNSs16/198) was passaged 25 times in Vero cells at MOI of 0.01 or less at three days post infection. The presence of reversion mutations are shown. (a) M-segment nt. 795: HEX-795-C and FAM-795-T, (b) M-segment nt. 3564: HEX-3564-G and FAM-3564-A, (c) L-segment nt. 533: HEX-533-C and FAM-533-T, (d) L-segment nt. 3104: HEX-3104-A and FAM-3104-G, and (e) L-segment nt. 3750: HEX-3750-A and FAM-3750-G. Two independent studies are shown (Exp-1 and 2). Relative percentages of RNA copy numbers for parental and reversion mutants are shown in blue and red bars, respectively. The bar labels in red represent the percentages of reversion mutants.

Table 1.

Illumina MiSeq amplicon sequencing1 for rMP12-ΔNSs16/198 (Vero cells, Exp-1, p25)

| Segment | PCR fragment2 | Location | nt. mutation |

aa. mutation |

Variant reads |

Total coverage |

% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | nt.705-1165 | 719 | U to A | S to R | 28992 | 267685 | 10.8 |

| 877 | A to U | Q to L | 202505 | 601576 | 33.7 | ||

| 1163 | C to U | - | 159382 | 910283 | 17.5 | ||

| 1165 | A to G | K to R | 344469 | 866107 | 39.8 | ||

| nt.3369-3815 | 3412 | C to U | T to I | 10400 | 863570 | 1.2 | |

| 3555 | U to C | Y to H | 39842 | 2246190 | 1.8 | ||

| 35643 | G to A | G to R | 124721 | 2182917 | 5.7 | ||

| 3684 | C to U | - | 96600 | 2129301 | 4.5 | ||

| 3733 | A to G | - | 39842 | 2246190 | 1.3 | ||

| L | nt.2850-3295 | 3240 | C to A | - | 47726 | 2514812 | 1.9 |

| nt.3733-4170 | 37503 | A to G | I to M | 438643 | 530118 | 82.7 | |

| 3814 | U to C | - | 944868 | 995347 | 94.9 | ||

| 3816 | A to C | - | 944042 | 995263 | 94.9 | ||

| 4142 | A to C | I to T | 5485 | 416681 | 1.3 |

The PCR fragments were amplified from viral RNA extracted from culture supernatants of rMP12-ΔNSs16/198 (Exp-1) at passage 25. The threshold of variant detection was set as 1%. nt., nucleotide; aa., amino acid.

Nucleotide positions of PCR fragments in the antiviral-sense M- or L-segment. Primer regions are excluded.

Reversion mutations to parental ZH548 strain.

In order to analyze overall mutations of passaged viruses, plaque clones of MP-12 (Vero cell passage 25, Exp-1) and rMP12-ΔNSs16/198 (Vero cell passage 25, Exp-1) were isolated, and the full-length genome sequence of each of four plaques was determined. Differences between these sequences and the original strains were then identified (Supplementary Table 1). All four clones of rMP12-ΔNSs16/198 encoded a reversion mutation at L-3750, and an additional 14 mutations were identified in the L-, M-, and S-segments. Among them, the M-A877U (three of four clones) and M-A1165G (two of four clones) mutations were also identified by deep sequencing, as 33.7% and 39.8% of the population, respectively (Table 1). MP-12 plaque clones did not encode reversion mutations, yet 18 mutations were identified among four clones. None of the mutations found in MP-12 or rMP12-ΔNSs16/198 were identical to those previously found in MP-12 plaque isolates from human vaccinees15.

Analysis of reversion mutations in vivo in a mouse encephalitis model

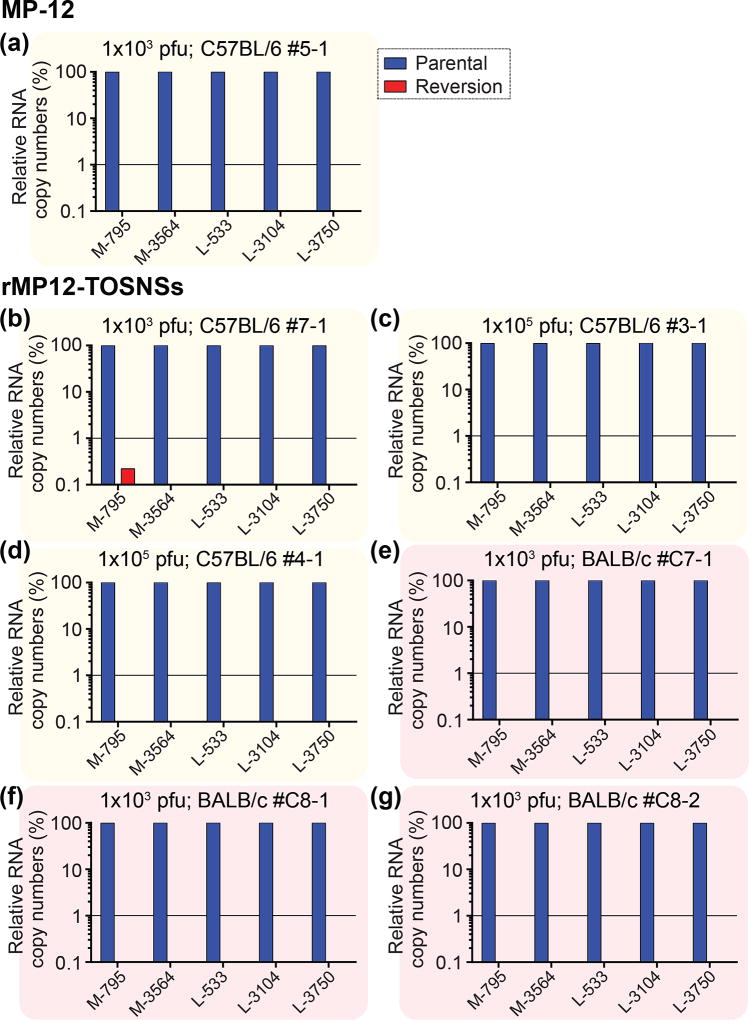

Although our study indicated that L-3750 has a risk of reversion during extensive viral passages in cell culture, reversions of MP-12 mutations have not been found in MP-12 isolates from vaccinees15. We have previously shown that subcutaneous vaccination of mice with the MP-12 vaccine rarely causes viral encephalitis31,32, whereas MP-12 encoding TOSV NSs in place of MP-12 NSs (rMP12-TOSNSs) causes viral encephalitis in up to 40% of mice at 10 to 18 dpi24. To evaluate the occurrence of reversion mutations of MP-12 and rMP12-TOSNSs during viral replication in vivo, total RNAs were extracted from the brains of mice with viral encephalitis caused by MP-12 (n = 1) or rMP12-TOSNSs (n = 6)24, and ddPCR analysis was conducted to detect reversion mutations. None of the seven brain samples, however, showed reversion mutations at M-795, M-3564, L-533, L-3104, or L-3750 (Fig. 6). Our results indicate that the replication of MP-12 or rMP12-TOSNSs in vivo for more than 10 days does not allow the emergence of reversion mutants.

Fig. 6. Detection of reversion mutations in MP-12 and rMP12-TOSNSs in brains of mice.

The ddPCR to detect reversion mutants at M-795, M-3564, L-533, L-3104, and L-3750 was performed using total RNA samples from mouse brains reported by Indran et al.24. BALB/c (e – g) or C57BL/6 mice (a – d) were inoculated with either MP-12 (a) or rMP12-TOSNSs (b – g) at either 1×103 or 1×105 pfu (i.p.). Relative percentages of RNA copy numbers for parental and reversion mutants are shown in blue and red bars, respectively.

Discussion

Live-attenuated vaccines have played historical roles in dramatically decreasing human and animal diseases of major public health importance33–35. In contrast to the benefit of strong immunogenicity, it is often difficult to explain the mechanism of attenuation due to empirical attenuation approaches36. As a result, reversion to wild-type virulence has been a concern for massive vaccination at the cost of disease control37. Reversion occurs through in several ways, including recombination between vaccine strains and pathogenic strains38–41, back-mutations of attenuation mutations42,43, or compensation mutations44 in the genome. The homologous recombination of negative-strand RNA viruses is relatively rare45, whereas attenuated viral phenotypes can be altered during replication. Re-adaptation of the cold-adapted 2009 pandemic H1N1 live-attenuated FluMist vaccine at 37°C resulted in reversion of a ts phenotype and virulence by acquisition of compensation mutations, without back-mutations of responsive ts mutations46.

RVFV is a three-segmented negative-stranded RNA virus belonging to the family Bunyaviridae. Few veterinary vaccines (e.g., Smithburn and Clone 13 vaccines) have been licensed for the use in Africa47,48. RVFV, including the above-mentioned vaccine strains, is classified as a select agent in the U.S., whereas a live-attenuated MP-12 strain is exempted from the select agent rules2,49. The safety and immunogenicity of the MP-12 vaccine has been demonstrated in sheep and cattle, and thus, this vaccine is conditionally licensed for veterinary use in the U.S.16,50–56. The MP-12 vaccine has also been evaluated in human volunteers for the safety and immunogenicity14,15. The MP-12 vaccine Lot 7-2-88 does not contain any detectable viral subpopulations encoding reversion mutations22. Furthermore, vaccination using the MP-12 vaccine lot did not cause detectable reversion mutation in human vaccinees15. Thus, reversion to virulence appears not to be a major concern for the MP-12 vaccine as long as it is produced from an appropriate Seed Lot system. Although reversion mutants have never been an issue for MP-12 vaccine, thus far, no previous study has accurately demonstrated changes in viral genetic subpopulations of the MP-12 vaccine strain during viral replications. With an increased population of reversion mutants in viral subpopulations, a vaccine may have an increased risk of adverse effects in vaccinees.

Attenuation of the MP-12 vaccine occurs due to a combination of several mutations in the L-, M-, and S-segments, and the mutations in the L- and M-segment play a major role in attenuation of MP-1220,57. Although a combination of each mutation is important, some mutations independently show attenuation and/or ts phenotype, including M-U795C (Y259H), M-A3564G (R1182G), L-U533C (V172A), and L-G3750A (M1244I)20,21. A previous study showed that the RVFV ZH548 strain causes a truncation of the NSs gene during serial passages in either BHK-21 cells or Aag2 cells, even at a MOI of 0.125. To prevent the emergence of gene truncation or DI RNA formation, serial passage was performed at very low MOI in the current study. The back titration of samples measured the MOI range as being between 0.00002 and 0.002 (101 to 104 viruses per input) during the passage. Under these experimental conditions, the sampling of limited amounts of viruses at each passage randomly selected specific viral populations. It is unlikely that mutants would become a dominant population unless the parental virus is not adapted to the cell line58. This study clearly demonstrated that the MP-12 vaccine increases viral populations encoding the back-mutation L-A3750G (I1244M) during serial viral passages in Vero or MRC-5 cells, which is a reversion mutation to ZH548. Emergence of the I1244M mutation in two or three independent experiments indicates that this mutation has an advantage in viral replication over the parental genotype. In fact, the L-M1244I mutation is responsible for the ts phenotype of the L-segment, and decreases viral RNA synthesis, but not viral titer, at 37°C21. Thus, it is plausible that a temperature of 37°C was a limiting factor for the RNA replication of the parental genotype, and thus the selection of the reversion mutant at L-M1244I occurred.

Reversion mutants can occur through the introduction of mutation by an error-prone RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, followed by subsequent selection of genotype during viral replication. The rMP12-ΔNSs16/198 was generated from cloned cDNA using reverse genetics. A possible source of reversion mutation was therefore the error-prone RVFV L protein. The mutation rates of negative-strand RNA viruses range from 10−4 to 10−6 per nucleotide per cell infection36,59. Since the total length of the MP-12 genome is 11,979 nt, only 0.01 to 1 mutations are expected to be introduced per a single-step virus life cycle. At a very low MOI, input virus is required to repeatedly infect neighboring cells, which can increase the possibility of the introduction of new mutations. On the other hand, the serial passages may not have allowed subsequent selection of specific reversion mutants in culture cells, unless the mutations can change viral phenotype.

RVFV NSs protein is a major virulence factor for RVF, and inhibits host antiviral responses via various mechanisms, including the cessation of cellular transcription and the degradation of dsRNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR)60–66. Thus, pathogenic RVFV strains have been attenuated through the deletion of NSs gene for the development of live-attenuated RVF vaccines29,67–69. The rMP12-ΔNSs16/198 strain (formerly named rMP12-C13type) encodes an in-frame 69% truncation in the NSs gene in the MP-12 strain backbone, causing viral replication to be limited in type-I IFN competent cells30. Type-I IFN-deficient Vero cells are an animal cell line established for vaccine production, and are also suitable for the growth of the rMP12-ΔNSs16/198 strain27,70,71. We investigated whether or not a lack of the NSs gene affects the selection of a viral genetic subpopulation during replication in Vero cells. With a lack of functional NSs, the rMP12-ΔNSs16/198 demonstrated emergence of reversion mutants not only at M1244I, but also at M-A3564G and L-U533C. A lack of NSs protein expression could therefore result in a change in selection threshold for reversion mutants, due to the cellular antiviral activities, which are not inhibited by NSs proteins; e.g., active cellular transcription and the expression of endogenous PKR.

Reversion mutations were further analyzed using an in vivo model. A recombinant MP-12 strain encoding the TOSV NSs gene (rMP12-TOSNSs) causes viral encephalitis in up to 40% of infected mice, whereas the neuroinvasion of parental MP-12 strain is less frequent24. Robust replication of MP-12 and rMP12-TOSNSs occurred in the brain at 10 dpi or later; although the mechanism of neuroinvasion has not been elucidated, it was initially assumed that pathogenic reversion mutants of the MP-12 strain selectively invade the central nervous system in mice. The expression of TOSV NSs proteins in the place of MP-12 NSs proteins may also affect the threshold of the mutant selection process. Contrary to the hypothesis, viral RNA from the brains of mice did not contain detectable reversion mutations, indicating that neuroinvasion by the MP-12 or rMP12-TOSNSs strain is an intrinsic to the nature of the parental genotype, and is independent of reversion mutations in the L- and M-segments. It should be noted that susceptibility to RVFV differs largely among host species and ages; the neuroinvasion of MP-12 strain is not known to occur in humans or ruminants7,72.

An individual reversion mutation does not immediately generate a pathogenic mutant of the MP-12 strain, because residual mutations alternatively attenuate the virus20. For example, the MP-12 strain encoding reversion mutations of both M-H259Y and M-G1182R in the M-segment was still largely attenuated in mice. Two of MP-12 L-segment mutations (L-V172A and L-M1244I) are ts mutations, and each inhibits viral RNA synthesis in a temperature-dependent manner21. The threshold of restriction temperature for MP-12 virus replication was 38°C. The attenuation of L-segment mutations, however, cannot be accurately evaluated using a mouse model, because none of recombinant ZH501 strains, encoding one of the MP-12 L-segment mutations were attenuated in mice20. Although the normal temperature of mice appears not to restrict the replication of the MP-12 strain, normal body temperatures of ruminants are higher than those of mice73,74. It is therefore possible that the attenuation of MP-12 strain is supported by ts mutations in ruminants, but not in mice. Previous studies have shown that the MP-12 strain has residual virulence in ewes, cows, and alpacas50,75–77. Virological and genetic analyses of viral isolates (e.g., compensation mutations) from affected tissues in ruminants may aid in elucidating the mechanism of residual virulence in the MP-12 strain.

The genetic stability of live-attenuated vaccine should be carefully analyzed if massive vaccination will be conducted in livestock animals or humans. Overall, our study showed that the MP-12 vaccine has outstanding genetic stability in Vero and MRC-5 cells within limited viral replication cycles. Nonetheless, reversion mutations at L-V172A, L-M1244I, and M-R1182G were confirmed during serial passage of viruses. Thus, in further vaccine safety analyses of the MP-12 vaccine strain, attention should be paid to the virulence associated with mutant genotypes generated in vitro and in vivo.

Methods

Media, Cells, and Viruses

Viruses were passaged in Vero cells (ATCC CCL-81) and MRC-5 cells (ATCC CCL-171); VeroE6 cells (ATCC CRL-1586) were used for virus titration. Cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified minimum essential medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 µg/ml). To rescue recombinant MP-12, BHK/T7-9 cells stably expressing T7 RNA polymerase were used30,78; these cells were maintained in MEM-alpha containing 10% FBS, penicillin/streptomycin, and 600 µg/ml of hygromycin B. All cells used in this study were verified to be mycoplasma free (UTMB Tissue Culture Core Facility), and the identity of MRC-5 cells was authenticated by Short Tandem Repeat analysis (UTMB Molecular Genomics Core Facility). The MP-12 vaccine Lot 7-2-88 was obtained from Dr. John C. Morrill at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston (UTMB), and used for virus serial passage experiments. Recombinant MP-12 (rMP-12) encoding an in-frame 69% truncation of NSs similar to that of the Clone 13 strain (rMP12-ΔNSs16/198, other name: rMP12-C13type)29 has been previously described30. The rMP-12 strain encoding TOSV NSs in the place of MP-12 NSs (rMP12-TOSNSs) has been described previously24,79. Rescued viruses were amplified once in VeroE6 cells after recovery in BHK/T7-9 cells, titrated by plaque assay, and then used for subsequent experiments.

Serial passages of MP-12 and rMP12-ΔNSs16/198

Vero cells were infected with MP-12 vaccine Lot 7-2-88 or rMP12-ΔNSs16/198 at 0.01 MOI (two separate passage experiments under the same conditions: Exp-1 and Exp-2). Culture supernatants were then collected at 3 days post infection (dpi), and 0.1 µl of supernatant was blindly passaged to fresh Vero cells in a 12-well plate (5×105 cells per well). When passage 25 was achieved, culture supernatants were back-titrated at 1, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 passages, and the MOI of each passage was determined to be 0.00002 to 0.002 (Fig. 2). The same passage experiment was repeated in MRC-5 cells using MP-12 vaccine Lot 7-2-88 (three separate passage experiments under the same conditions: Exp-1, Exp-2, and Exp-3) (Fig. 2). The rMP12-ΔNSs16/198 was not tested in MRC-5 cells, because this virus lacks the expression of functional NSs proteins and does not efficiently replicate in type-I IFN-competent MRC-5 cells30.

Droplet digital PCR analysis

To measure the RNA copy numbers of parental MP-12 and the mutant genotypes in viral M- and L-segment RNA, droplet digital PCR was performed using the BioRad QX100 droplet generator and reader, as described previously80. Two Taqman probes were designed per mutation (Supplementary Fig. 1). The specificity and sensitivity of detecting mutant genotypes was evaluated in each probe set using in vitro synthesized M- or L-segment RNA from parental and mutant genotypes (Supplementary Fig. 2). To extract viral RNA, 250 µl of clarified culture supernatants were digested with 25 U Benzonase (EMD Millipore) at 37°C for 30 min, to minimize the contamination of free viral RNA derived from dead cells. The enzyme-treated culture supernatant (250 µl) was mixed with 750 µl Trizol LS (Life Technologies), and spike RNA (in vitro synthesized chloramphenicol acetyltransferase RNA, 3 µg) was added. The spike RNA was included because the quantity of viral RNA in a 250 µl sample was too low to be measured accurately. Viral RNA was then extracted using Direct-zol RNA MiniPrep Kit (Zymo Research), according to manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration of extracted RNA (spike RNA) was measured via Qubit Fluorometer (Life Technologies) and first-strand complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using iScript (BioRad), which has RNase H activity that can digest template RNA upon cDNA synthesis and therefore better reflects the ratio of cDNA copy number per RNA template. PCR reactions were prepared as follows: 250 nM of each Taqman probe, 900 nM of each primer, ddPCR Supermix for Probes (BioRad), cDNA, and water (up to 25 µl). PCR cycling parameters were: initial denaturation (95°C for 10 min), followed by 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec, 60°C for 1 min, and a final denaturation step of 98°C for 10 min. The number of droplets with positive and negative signals was measured using a BioRad QX100 droplet reader. Finally, data analysis was performed using QuantaSoft Version 1.4 (BioRad). The droplet reader was able to count up to 20,000 droplets and the input of cDNA was optimized to visualize two genotype populations by ddPCR.

Deep sequencing of PCR fragments and variant analysis

To validate the accuracy of the ddPCR results, deep sequencing using an Illumina MiSeq Desktop Sequencer was performed (Applied Biological Materials Inc). For this purpose, the 25th passage sample of rMP12-ΔNSs16/198 (Exp-1) was used for analysis of four sites. Two sites possessed reversion mutations that were detectable by ddPCR (M-A3564G or L-G3750A), and the other two sites possessed reversion mutations that were not detectable by ddPCR (M-U795C and L-G3104A). One ng of PCR fragments flanking either M-U795C (nt. 705 – 1165), M-A3564G (nt. 3360 – 3815), L-G3104A (nt. 2850 – 3295), or L-G3750A (nt. 3733 – 4170) were fragmented with the Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit, and sequenced in a paired-end run of 250 base pairs using the MiSeq Reagent Kit v2 (500 cycles). Resulting FASTAQ files were imported to the CLC Genomics Workbench 7.0.4. as paired reads, and failed files were excluded. Probabilistic variant detection was performed to detect 1% minimum variant frequency found in both pairs, with a minimum central quality of 20 and a minimum neighborhood quality of 15, within five nucleotides.

Analysis of viral RNA from brains of mice

For the analysis of genetic changes in the MP-12 strain in vivo, total RNAs were extracted from brain tissue samples stored in TRIzol, which were collected from four-week-old female BALB/c mice or C57BL/6 mice intraperitoneally vaccinated with MP-12 (n = 10 each) or rMP12-TOSNSs (n = 10 each) (1×103 pfu or 1×105 pfu) in a previous experiment24. In that previous experiment, encephalitis was confirmed by following mice during a 56-day observation period. During that time, encephalitis was found in 10% of mice vaccinated with 1×103 pfu of MP-12, at 11 dpi in BALB/c mice (sample not available) and at 14 dpi in C57BL/6 mice (mouse #5-1). No mice, regardless of strain, developed encephalitis when vaccinated with 1×105 pfu of MP-12. When vaccinated with 1×103 pfu of rMP12-TOSNSs, 30% of BALB/c mice (11 dpi: mouse #C7-1, 11 dpi: mouse #C8-1, 15 dpi: mouse #C8-2) and 10% of C57BL/6 mice (12 dpi: mouse #7-1) developed encephalitis. Finally, vaccination with 1×105 pfu of rMP12-TOSNSs caused no encephalitis in BALB/c mice, but 30% of C57BL/6 mice developed encephalitis (10 dpi: mouse #3-1, 12 dpi: mouse #4-1)24.

Ethics statement

All experiments using recombinant RVFV were performed with the approval of the Notification of Use by the Institutional Biosafety Committee at UTMB. Mouse experiments were performed in facilities accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC), in accordance with the Animal Welfare Act, NIH guidelines, and US federal law. Animal protocols were approved by the UTMB Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), Protocol number 0904027.

Data Availability

The raw sequencing data by MiSeq was deposited in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database (accession number: SRP103530). The S-segment sequence of rMP12-ΔNSs16/198 was deposited in the Genbank (accession number: KY926697). The M- and L-segment sequences of rMP12-ΔNSs16/198 were identical to that of MP-12 strain (Genbank accession numbers: DQ380208 and DQ375404)5.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. C.J. Peters and J.C. Morrill at The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston (UTMB) for their helpful information and materials to study the MP-12 vaccine. This study was supported by NIH R01 AI087643-01A1 (T.I.) and funding from the Sealy Center for Vaccine Development at the UTMB. We would like to thank Dr. Raymond Miller (Bio-Rad) for his technical support to set up the ddPCR experiment.

Funding

This study was supported by NIH R01 AI087643-01A1 (T.I.) and funding from the Sealy Center for Vaccine Development at the UTMB.

Footnotes

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Author Contributions

N.L. and T.I. (guarantor) designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the data, wrote the paper, and approved of the completed version of manuscript.

References

- 1.Dar O, Hogarth S, McIntyre S. Tempering the risk: Rift Valley fever and bioterrorism. Trop Med Int Health. 2013;18:1036–1041. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jonsson CB, Cole KS, Roy CJ, Perlin DS, Byrne G. Challenges and Practices in Building and Implementing Biosafety and Biosecurity Programs to Enable Basic and Translational Research with Select Agents. J Bioterror Biodef. 2013;(Suppl 3):12634. doi: 10.4172/2157-2526.S3-015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shurtleff AC, et al. The impact of regulations, safety considerations and physical limitations on research progress at maximum biocontainment. Viruses. 2012;4:3932–3951. doi: 10.3390/v4123932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grobbelaar AA, et al. Molecular epidemiology of Rift Valley fever virus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:2270–2276. doi: 10.3201/eid1712.111035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bird BH, Khristova ML, Rollin PE, Ksiazek TG, Nichol ST. Complete genome analysis of 33 ecologically and biologically diverse Rift Valley fever virus strains reveals widespread virus movement and low genetic diversity due to recent common ancestry. J Virol. 2007;81:2805–2816. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02095-06. doi:JVI.0209506 [pii]10.1128/JVI.02095-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carroll SA, et al. Genetic evidence for Rift Valley fever outbreaks in Madagascar resulting from virus introductions from the East African mainland rather than enzootic maintenance. J Virol. 2011;85:6162–6167. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00335-11. doi:JVI.00335-11 [pii]10.1128/JVI.00335-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swanepoel R, Coetzer JAW. Rift Valley fever. In: Coetzer JAW, Tustin RC, editors. Infectious diseases of livestock with special reference to southern Africa. 2. Vol. 2004. Cape Town, South Africa: Oxford University Press; 2004. pp. 1037–1070. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pepin M, Bouloy M, Bird BH, Kemp A, Paweska J. Rift Valley fever virus (Bunyaviridae: Phlebovirus): an update on pathogenesis, molecular epidemiology, vectors, diagnostics and prevention. Vet Res. 2010;41:61. doi: 10.1051/vetres/2010033. doi:10.1051/vetres/2010033 v100009 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meegan JM. The Rift Valley fever epizootic in Egypt 1977–78. 1. Description of the epizzotic and virological studies. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1979;73:618–623. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(79)90004-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Madani TA, et al. Rift Valley fever epidemic in Saudi Arabia: epidemiological, clinical, and laboratory characteristics. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:1084–1092. doi: 10.1086/378747. doi:CID31451 [pii]10.1086/378747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nguku PM, et al. An investigation of a major outbreak of Rift Valley fever in Kenya: 2006–2007. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83:5–13. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0288. doi:83/2_Suppl/05 [pii]10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pittman PR, et al. Immunogenicity of an inactivated Rift Valley fever vaccine in humans: a 12-year experience. Vaccine. 1999;18:181–189. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00218-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rusnak JM, Gibbs P, Boudreau E, Clizbe DP, Pittman P. Immunogenicity and safety of an inactivated Rift Valley fever vaccine in a 19-year study. Vaccine. 2011;29:3222–3229. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.02.037. doi:S0264-410X(11)00250-7 [pii]10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pittman PR, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a mutagenized, live attenuated Rift Valley fever vaccine, MP-12, in a Phase 1 dose escalation and route comparison study in humans. Vaccine. 2016;34:424–429. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pittman PR, et al. Rift Valley fever MP-12 vaccine Phase 2 clinical trial: Safety, immunogenicity, and genetic characterization of virus isolates. Vaccine. 2016;34:523–530. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.11.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller MM, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy, potential for vector transmission, and duration of immunity of MP-12, an attenuated Rift Valley fever virus vaccine candidate, in sheep. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2015;22:930–937. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00114-15. doi:CVI.00114-15 [pii]10.1128/CVI.00114-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmaljohn C, Nichol ST. Bunyaviridae. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Roizman B, Straus SE, editors. Fields Virology. 5. Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 2007. pp. 1741–1789. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerrard SR, Nichol ST. Synthesis, proteolytic processing and complex formation of N-terminally nested precursor proteins of the Rift Valley fever virus glycoproteins. Virology. 2007;357:124–133. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.08.002. doi:S0042-6822(06)00546-0 [pii]10.1016/j.virol.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phoenix I, Lokugamage N, Nishiyama S, Ikegami T. Mutational Analysis of the Rift Valley Fever Virus Glycoprotein Precursor Proteins for Gn Protein Expression. Viruses. 2016;8 doi: 10.3390/v8060151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ikegami T, et al. Rift Valley Fever Virus MP-12 Vaccine Is Fully Attenuated by a Combination of Partial Attenuations in the S, M, and L Segments. J Virol. 2015;89:7262–7276. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00135-15. doi:JVI.00135-15 [pii]10.1128/JVI.00135-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishiyama S, Lokugamage N, Ikegami T. The L-, M- and S-segments of Rift Valley fever virus MP-12 vaccine independently contribute to a temperature-sensitive phenotype. J Virol. 2016;90:3735–37644. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02241-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lokugamage N, Freiberg AN, Morrill JC, Ikegami T. Genetic Subpopulations of Rift Valley Fever ZH548, MP-12 and Recombinant MP-12 Strains. J Virol. 2012;86:13566–13575. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02081-12. doi:JVI.02081-12 [pii]10.1128/JVI.02081-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ikegami T, et al. Dual functions of Rift Valley fever virus NSs protein: inhibition of host mRNA transcription and post-transcriptional downregulation of protein kinase PKR. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1171(Suppl 1):E75–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05054.x. doi:NYAS5054 [pii]10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05054.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Indran SV, et al. Rift Valley fever virus MP-12 vaccine encoding Toscana virus NSs retains neuroinvasiveness in mice. J Gen Virol. 2013;94:1441–1450. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.051250-0. doi:vir.0.051250-0 [pii]10.1099/vir.0.051250-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moutailler S, et al. Host alternation is necessary to maintain the genome stability of rift valley fever virus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e1156. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001156. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001156 PNTD-D-10-00113 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garcia-Arriaza J, Manrubia SC, Toja M, Domingo E, Escarmis C. Evolutionary transition toward defective RNAs that are infectious by complementation. J Virol. 2004;78:11678–11685. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.21.11678-11685.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mosca JD, Pitha PM. Transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation of exogenous human beta interferon gene in simian cells defective in interferon synthesis. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:2279–2283. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.6.2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Habjan M, Penski N, Spiegel M, Weber F. T7 RNA polymerase-dependent and -independent systems for cDNA-based rescue of Rift Valley fever virus. J Gen Virol. 2008;89:2157–2166. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.2008/002097-0. doi:89/9/2157 [pii]10.1099/vir.0.2008/002097-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muller R, et al. Characterization of clone 13, a naturally attenuated avirulent isolate of Rift Valley fever virus, which is altered in the small segment. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995;53:405–411. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1995.53.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ikegami T, Won S, Peters CJ, Makino S. Rescue of infectious rift valley fever virus entirely from cDNA, analysis of virus lacking the NSs gene, and expression of a foreign gene. J Virol. 2006;80:2933–2940. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.6.2933-2940.2006. doi:80/6/2933 [pii]10.1128/JVI.80.6.2933-2940.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lihoradova O, et al. The dominant-negative inhibition of double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase PKR increases the efficacy of Rift Valley fever virus MP-12 vaccine. J Virol. 2012;86:7650–7661. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00778-12. doi:JVI.00778-12 [pii]10.1128/JVI.00778-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lihoradova OA, et al. Characterization of Rift Valley Fever Virus MP-12 Strain Encoding NSs of Punta Toro Virus or Sandfly Fever Sicilian Virus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2181. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002181. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002181 PNTD-D-12-01435 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Minor PD. Live attenuated vaccines: Historical successes and current challenges. Virology. 2015;479–480:379–392. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Plotkin S. History of vaccination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:12283–12287. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400472111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McVey S, Shi J. Vaccines in veterinary medicine: a brief review of history and technology. The Veterinary clinics of North America. Small animal practice. 2010;40:381–392. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lauring AS, Frydman J, Andino R. The role of mutational robustness in RNA virus evolution. Nature reviews. Microbiology. 2013;11:327–336. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hanley KA. The double-edged sword: How evolution can make or break a live-attenuated virus vaccine. Evolution (N Y) 2011;4:635–643. doi: 10.1007/s12052-011-0365-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee SW, et al. Attenuated vaccines can recombine to form virulent field viruses. Science. 2012;337:188. doi: 10.1126/science.1217134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang Y, et al. Characterization of a rare natural intertypic type 2/type 3 penta-recombinant vaccine-derived poliovirus isolated from a child with acute flaccid paralysis. J Gen Virol. 2010;91:421–429. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.014258-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mochizuki M, Ohshima T, Une Y, Yachi A. Recombination between vaccine and field strains of canine parvovirus is revealed by isolation of virus in canine and feline cell cultures. J Vet Med Sci. 2008;70:1305–1314. doi: 10.1292/jvms.70.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.He CQ, Ma LY, Wang D, Li GR, Ding NZ. Homologous recombination is apparent in infectious bursal disease virus. Virology. 2009;384:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Victoria JG, et al. Viral nucleic acids in live-attenuated vaccines: detection of minority variants and an adventitious virus. J Virol. 2010;84:6033–6040. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02690-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kew OM, Sutter RW, de Gourville EM, Dowdle WR, Pallansch MA. Vaccine-derived polioviruses and the endgame strategy for global polio eradication. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2005;59:587–635. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Valsamakis A, Auwaerter PG, Rima BK, Kaneshima H, Griffin DE. Altered virulence of vaccine strains of measles virus after prolonged replication in human tissue. J Virol. 1999;73:8791–8797. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8791-8797.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Han GZ, Worobey M. Homologous recombination in negative sense RNA viruses. Viruses. 2011;3:1358–1373. doi: 10.3390/v3081358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou B, et al. Reversion of Cold-Adapted Live Attenuated Influenza Vaccine into a Pathogenic Virus. J Virol. 2016;90:8454–8463. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00163-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alhaj M. Safety and Efficacy Profile of Commercial Veterinary Vaccines against Rift Valley Fever: A Review Study. Journal of immunology research. 2016;2016:7346294. doi: 10.1155/2016/7346294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.WHO. The use of veterinary vaccines for prevention and control of Rift Valley fever: memorandum from a WHO/FAO meeting. Bull World Health Organ. 1983;61:261–268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Caplen H, Peters CJ, Bishop DH. Mutagen-directed attenuation of Rift Valley fever virus as a method for vaccine development. J Gen Virol. 1985;66(Pt 10):2271–2277. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-66-10-2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morrill JC, et al. Further evaluation of a mutagen-attenuated Rift Valley fever vaccine in sheep. Vaccine. 1991;9:35–41. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(91)90314-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morrill JC, et al. Pathogenicity and immunogenicity of a mutagen-attenuated Rift Valley fever virus immunogen in pregnant ewes. Am J Vet Res. 1987;48:1042–1047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morrill JC, Mebus CA, Peters CJ. Safety of a mutagen-attenuated Rift Valley fever virus vaccine in fetal and neonatal bovids. Am J Vet Res. 1997;58:1110–1114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morrill JC, Mebus CA, Peters CJ. Safety and efficacy of a mutagen-attenuated Rift Valley fever virus vaccine in cattle. Am J Vet Res. 1997;58:1104–1109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morrill JC, Peters CJ. Pathogenicity and neurovirulence of a mutagen-attenuated Rift Valley fever vaccine in rhesus monkeys. Vaccine. 2003;21:2994–3002. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(03)00131-2. doi:S0264410X03001312 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hubbard KA, Baskerville A, Stephenson JR. Ability of a mutagenized virus variant to protect young lambs from Rift Valley fever. Am J Vet Res. 1991;52:50–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hill RE, Jr, et al. Regulatory considerations for emergency use of non-USDA licensed vaccines in the United States. Dev Biol (Basel) 2003;114:31–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Billecocq A, et al. RNA polymerase I-mediated expression of viral RNA for the rescue of infectious virulent and avirulent Rift Valley fever viruses. Virology. 2008;378:377–384. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.05.033. doi:S0042-6822(08)00382-6 [pii]10.1016/j.virol.2008.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Woo HJ, Reifman J. Quantitative modeling of virus evolutionary dynamics and adaptation in serial passages using empirically inferred fitness landscapes. J Virol. 2014;88:1039–1050. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02958-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sanjuan R, Nebot MR, Chirico N, Mansky LM, Belshaw R. Viral mutation rates. J Virol. 2010;84:9733–9748. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00694-10. doi:JVI.00694-10 [pii]10.1128/JVI.00694-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ly HJ, Ikegami T. Rift Valley fever virus NSs protein functions and the similarity to other bunyavirus NSs proteins. Virol J. 2016;13:118. doi: 10.1186/s12985-016-0573-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bouloy M, et al. Genetic evidence for an interferon-antagonistic function of rift valley fever virus nonstructural protein NSs. J Virol. 2001;75:1371–1377. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.3.1371-1377.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ikegami T, et al. Rift Valley fever virus NSs protein promotes post-transcriptional downregulation of protein kinase PKR and inhibits eIF2alpha phosphorylation. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000287. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Habjan M, et al. NSs protein of rift valley fever virus induces the specific degradation of the double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase. J Virol. 2009;83:4365–4375. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02148-08. doi:JVI.02148-08 [pii]10.1128/JVI.02148-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Billecocq A, et al. NSs protein of Rift Valley fever virus blocks interferon production by inhibiting host gene transcription. J Virol. 2004;78:9798–9806. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.18.9798-9806.2004. doi:10.1128/JVI.78.18.9798-9806.2004 78/18/9798 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Le May N, et al. TFIIH transcription factor, a target for the Rift Valley hemorrhagic fever virus. Cell. 2004;116:541–550. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00132-1. doi:S0092867404001321 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Le May N, et al. A SAP30 complex inhibits IFN-beta expression in Rift Valley fever virus infected cells. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e13. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040013. doi:07-PLPA-RA-0344 [pii]10.1371/journal.ppat.0040013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.FAO. The last hurdles towards Rift Valley Fever control. Report on the Ad hoc workshop on the current state of Rift Valley fever vaccine and diagnostics development -Rome; 5–7 March 2014; FAO Animal Production and Health Report No. 9; Rome, Italy. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bird BH, et al. Rift Valley Fever Virus Vaccine Lacking the NSs and NSm Genes Is Safe, Nonteratogenic, and Confers Protection from Viremia, Pyrexia, and Abortion following Challenge in Adult and Pregnant Sheep. J Virol. 2011;85:12901–12909. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06046-11. doi:JVI.06046-11 [pii]10.1128/JVI.06046-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kortekaas J, et al. Comparative efficacy of two next-generation Rift Valley fever vaccines. Vaccine. 2014;32:4901–4908. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.07.037. doi:S0264-410X(14)00978-5 [pii]10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Genzel Y. Designing cell lines for viral vaccine production: Where do we stand? Biotechnol J. 2015;10:728–740. doi: 10.1002/biot.201400388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Diaz MO, et al. Homozygous deletion of the alpha- and beta 1-interferon genes in human leukemia and derived cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:5259–5263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Findlay GM. Rift Valley fever on enzootic hepatitis. Trans. Roy. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1931;25:229–262. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Talan M. Body temperature of C57BL/6J mice with age. Exp Gerontol. 1984;19:25–29. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(84)90028-7. doi:0531-5565(84)90028-7 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Robertshaw D. Temperature regulation and thermal environment. In: Reece WO, editor. Duke's Physiology of Domestic Animals. 12. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wilson WC, et al. Evaluation of lamb and calf responses to Rift Valley fever MP-12 vaccination. Vet Microbiol. 2014;172:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.04.007. doi:S0378-1135(14)00207-7 [pii]10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rissmann M, et al. Vaccination of alpacas against Rift Valley fever virus: Safety, immunogenicity and pathogenicity of MP-12 vaccine. Vaccine. 2017;35:655–662. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hunter P, Erasmus BJ, Vorster JH. Teratogenicity of a mutagenised Rift Valley fever virus (MVP 12) in sheep. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 2002;69:95–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ito N, et al. Improved recovery of rabies virus from cloned cDNA using a vaccinia virus-free reverse genetics system. Microbiol Immunol. 2003;47:613–617. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2003.tb03424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kalveram B, Ikegami T. Toscana Virus NSs Protein Promotes Degradation of Double-Stranded RNA-Dependent Protein Kinase. J. Virol. 2013;87:3710–3718. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02506-12. doi:JVI.02506-12 [pii]10.1128/JVI.02506-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ly HJ, Lokugamage N, Ikegami T. Application of Droplet Digital PCR to Validate Rift Valley Fever Vaccines. In: Thomas S, editor. Vaccine Design Methods and Protocols Vol. 1 Vaccine for Human Diseases. Humana Press, Springer; New York: 2016. pp. 207–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw sequencing data by MiSeq was deposited in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database (accession number: SRP103530). The S-segment sequence of rMP12-ΔNSs16/198 was deposited in the Genbank (accession number: KY926697). The M- and L-segment sequences of rMP12-ΔNSs16/198 were identical to that of MP-12 strain (Genbank accession numbers: DQ380208 and DQ375404)5.