Abstract

Importance

Suicide is a leading cause of deaths in the U.S. Although the emergency department (ED) is an opportune setting for initiating suicide prevention efforts, ED-initiated suicide prevention interventions remain underdeveloped.

Objective

To determine if an ED-initiated intervention reduces subsequent suicidal behavior.

Design

This multicenter study was composed of three sequential phases: 1) Treatment as Usual (TAU) (August 2010–December 2011), 2) Universal Screening (Screening) (September 2011–December 2012, and 3) Universal Screening + Intervention (Intervention)(July 2012-November 2013.

Setting

Eight EDs in the United States

Participants

Adults with a recent suicidal attempt or ideation were enrolled.

Intervention

Universal Screening consisted of universal suicide risk screening. The Intervention phase consisted of universal screening plus an intervention which included secondary suicide risk screening by the ED physician, discharge resources, and post-ED telephone calls focused on reducing suicide risk.

Main Outcomes

The primary outcome was suicide attempts (non-fatal and fatal) over the 52-week follow-up. The proportion and total number of attempts were analyzed.

Results

1,376 participants (56% female, median age 36 years) were recruited. 288 participants (21%) made at least one suicide attempt. There were 548 total suicide attempts among participants. There were no significant differences in risk reduction between the TAU and Screening phases (23% vs. 22%). However, when compared to the TAU Phase, subjects in the Intervention phase showed a 5 % absolute reduction in suicide attempt risk (23% vs. 18%) with a relative risk reduction of 20%. Participants in the Intervention Phase had 30% fewer total suicide attempts than participants in the TAU Phase.

Negative binomial regression analysis indicated that the participants in the Intervention Phase had significantly fewer total suicide attempts than participants in the TAU Phase (IRR, 0.72, 95%CI 0.52–1.00, P=0.05), but no differences between the TAU and Screening phases (IRR, 1, 95%CI 0.71–1.41, P=0.99).

Conclusions

Among at-risk patients in the ED, a combination of brief interventions administered both during and after the ED visit decreased post-ED suicidal behavior.

Keywords: suicide intervention, screening, mental health, emergency department

BACKGROUND

Suicidal behavior is a significant public health issue. In 2015, there were 44,193 deaths by suicide in the United States 1. Suicide accounts for 1.2% of all deaths and is the tenth leading cause of death in the United States 1. Attempted suicide is an even more common event, with over 1,000,000 people per year attempting suicide 1.

Despite its significance, few intervention trials have targeted and/or reduced suicidal behavior. Some psychotherapies have been found to reduce rates of suicide attempts2-4, although there are concerns about publication bias 5. Additionally, these interventions require substantial training and are lengthy and costly to administer. Briefer, less intensive interventions (e.g. follow-up letters, reminder postcards) have had mixed results6. New interventions specifically developed to prevent suicidal behavior are clearly needed.

Since emergency departments (EDs) treat many patients who are at risk for suicidal behavior, they are particularly important locations for suicide prevention. More than 4% of all ED visits, are attributable to psychiatric conditions7, and there are approximately 420,000 visits every year for intentional self-harm8. These high-risk individuals are susceptible to suicide attempts after the ED visit9. Also, a significant proportion of those who die by suicide received care in an ED in the period prior to death10-12

To address these ongoing public health issues, we conducted a multicenter study of adult ED patients who screened positive for suicidal attempts or ideation. In this paper, we focus on the hypothesis that a multi-faceted intervention delivered during and after the ED visit would decrease subsequent suicidal behaviors as compared to usual care.

METHODS

Study Design and Settings

This paper is part of the Emergency Department Safety Assessment and Follow-up Evaluation study (ED-SAFE). ED-SAFE was designed to examine the impact of universal screening and an intervention on individuals at-risk for suicide in the ED setting. Description of the methods13 and impact of screening on risk detection14 have been reported previously. Participants with suicidal ideation or recent attempt were recruited from eight EDs across seven states, ranging from small community hospitals to large academic centers. To increase generalizability, no participating ED had psychiatric services located within or adjacent to the ED. ED-SAFE consisted of three sequential phases at each site: Phase 1) Treatment as Usual (TAU), Phase 2) Universal Screening (Screening), and Phase 3) Universal Screening + Intervention (Intervention).

For all phases, following the index ED visit, enrolled participants were followed for one year using telephone assessments and medical chart reviews. Trained blinded interviewers at a centralized call center conducted outcome assessments at 6, 12, 24, 36, and 52 weeks. If suicide risk was detected, the participant was immediately connected to the Boy’s Town Suicide Prevention Hotline15. Additionally, using a standardized form, trained chart abstractors at each site conducted chart reviews 6 and 12 months after enrollment.

In the TAU phase, participants were treated according to the usual and customary care at each site, serving as the control for the subsequent study phases. In the Screening phase, sites implemented clinical protocols with universal suicide risk screening (the Patient Safety Screener14) for all ED patients. In the Intervention phase, in addition to universal screening, all sites implemented a three component intervention: 1) a secondary suicide risk screener designed for ED physicians to evaluate suicide risk following an initial positive screen, 2) provision of a self-administered safety plan and information to patients by nursing staff, and 3) a series of telephone calls to the participant, with the optional involvement of their significant other, for 52 weeks following the index ED visit.13 The structure and content of these calls were based on the Coping Long Term with Active Suicide Program (CLASP) protocol,13 16 an adjunctive intervention designed to reduce suicide risk which is composed of a unique combination of case management, individual psychotherapy and significant other (SO) involvement. The CLASP provider’s primary role was more of a treatment “advisor” than “therapist.” CLASP-ED consisted of up to seven brief (10–20 minute) telephone calls to the participant and up to four calls to a SO identified by the participant (if available) (Table S1). The calls focused on identifying suicide risk factors, clarifying values and goals, safety and future planning, facilitating treatment engagement/adherence, and facilitating patient-significant other problem solving. Multiple attempts were made to complete each scheduled call and voice mails left. If a call could not be completed, the advisor sent a personalized letter expressing concern for the patient and inviting them to call.

CLASP-ED calls were centralized at Butler Hospital (Providence, RI) and administered by 10 “advisors” (6 PhD psychologists, 3 psychology fellows and 1 masters-level counselor). All advisors were trained to criteria by the developers of CLASP and received weekly supervision.

Institutional review boards at each site approved the study; all participants gave informed consent. The National Institute of Mental Health Data and Safety Monitoring Board conducted overall study oversight and monitoring13.

Participants

Adults presenting to one of the EDs with a suicidal attempt or ideation within the week prior to the ED visit were eligible for inclusion. ED patients with any level of self-harm behavior or ideation were identified via “real time” medical record review and approached for eligibility screening. The patient was enrolled if he/she confirmed either a suicide attempt or active suicidal ideation within the past week and agreed to study requirements. Exclusion criteria included: 1) medically or cognitively unable to participate in study procedures, 2) dwelling in a non-community setting, 3) state custody or pending legal action, 4) without permanent residence or reliable telephone service, 5) insurmountable language barrier.

Outcomes

Outcomes were assessed by a combination of telephone interviews using the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale17 (C-SSRS) and chart review over the 52 week follow-up. The occurrence and timing of each outcome variable was assessed using data collected from all possible sources. Research team members reviewed data from all sources to reconcile discrepancies and to eliminate overlap in identified events.

Consistent with other suicide prevention trials, the primary outcome variable was suicide attempts (both non-fatal and fatal) based on C-SSRS definitions. We analyzed both the proportion of patients who made a suicide attempt and the total number of suicide attempts occurring during the 52-week follow-up.

We also analyzed a broader “suicide composite” based on occurrence of any of five types of suicidal behavior: death by suicide, suicide attempt, interrupted or aborted attempts, and suicide preparatory acts.17

The time-to-event for each participant was defined as the period from the index ED visit to when the outcome occurred within the 52 week follow-up period. Participants who did not have an outcome were censored at time of withdrawal (suicide attempt) or their last follow-up interview (suicide composite).

Statistical Analysis

The sample-size calculation was based on an assumed rate of the primary outcome over the 52 week period in the TAU phase of 20%18,19. Thus, enrollment of 1,440 patients has a power of 80% (at a two-sided alpha level of 0.05) to detect an absolute risk reduction of 7 percentage points (or a relative risk reduction of 35%) in the Intervention phase, allowing for an expected 20% loss to follow-up over the 52-week follow-up period.

Continuous variables were reported as medians and interquartile ranges, and categorical variables as proportions. Kruskal-Wallis, chi-square, and Fisher’s exact tests were used to analyze between-phase baseline differences.

Analyses included all enrolled participants, with no exclusions (intention-to-treat). To test for potential differences in the proportion of patients making a suicide attempt, we first calculated absolute risk reduction, relative risk reduction, and number needed to treat. We then conducted survival analyses with Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test. To test for differences in the total number of suicide attempts, and since our outcomes were overly-dispersed, we conducted negative binomial regression.

These primary analyses were followed by several additional analyses. First, since our study was a sequential design, we were aware of the potential of patient-level confounding across study phases exists. Therefore, consistent with our a priori data analytic plans, in order to control for potential differences between study phases, we conducted both Cox proportional hazards and negative binomial models adjusting for potential confounders that were selected based on clinical knowledge and demonstrated predictive relationship with suicide outcomes as well as dummy variables for participating site. (See Table 1). We detected no violation of the proportionality of hazards assumption using log cumulative hazards plots, Schoenfeld residual plots, and time-dependent variables20(P=0.27).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Participants at Baseline, according to the Study Phase

| Phase 1 | Phase 2 | Phase 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment as Usual | Universal Screening | Universal Screening + Intervention | |

| Characteristics | (n=497) | (n=377) | (n=502) |

| Demographics | |||

| Age (y), median (IQR)+ | 37 (26–46) | 36 (28–48) | 36 (24–47) |

| Female+ | 278 (56) | 210 (56) | 281 (56) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 340 (68) | 242 (64) | 346 (69) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 72 (15) | 60 (16) | 73 (15) |

| Hispanic | 63 (13) | 50 (13) | 58 (12) |

| Other | 22 (4) | 25 (7) | 25 (5) |

| Not married | 407 (82) | 295 (78) | 415 (83) |

| Lives alone*+ | 151 (30) | 86 (23) | 124 (25) |

| Served in the military+ | 38 (8) | 20 (5) | 27 (5) |

| Education (High school graduate or lower) | 251 (51) | 192 (51) | 260 (52) |

| Unemployed | 304 (67) | 247 (71) | 289 (64) |

| Coexisting medical disorder+ | 350 (70) | 274 (73) | 328 (65) |

| Heart disease | 29 (6) | 29 (8) | 33 (7) |

| Cancer | 10 (2) | 12 (3) | 19 (4) |

| HIV infection | 10 (2) | 7 (2) | 8 (2) |

| Diabetes | 58 (12) | 40 (11) | 60 (12) |

| Stroke | 3 (1) | 5 (1) | 11 (2) |

| Chronic pain | 130 (66) | 261 (69) | 307 (61) |

| Coexisting psychiatric disorder+ | 432 (87) | 334 (89) | 436 (87) |

| Depression | 409 (82) | 315 (84) | 406 (81) |

| Bipolar disorder | 202 (41) | 175 (46) | 194 (39) |

| Anxiety | 296 (60) | 236 (63) | 285 (57) |

| Schizophrenia* | 62 (12) | 38 (10) | 49 (10) |

| Lifetime suicide-related history+ | |||

| History of suicide attempt | 351 (71) | 268 (71) | 368 (73) |

| History of aborted attempt | 296 (60) | 241 (64) | 301 (60) |

| History of interrupted attempt* | 272 (55) | 238 (63) | 285 (57) |

| History of non-suicidal self-injury | 222 (45) | 186 (49) | 230 (46) |

| Severity of suicide ideation (Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale 16), median (IQR)+ | 0 (0–5) | 2 (0–5) | 0 (0–5) |

| Healthcare utilization | |||

| ED visit for psychiatric problems within the past 6-months+ | 168 (34) | 125 (33) | 150 (30) |

| Hospitalization for psychiatric problems within past 6-months+ | 110 (22) | 88 (23) | 110 (22) |

| Suicide attempt within past week+ | 183 (37) | 114 (30) | 162 (32) |

| Substance Use | |||

| Current alcohol misuse+ 19 | 181 (36) | 117 (31) | 173 (34) |

| Current drug use+ | 245 (49) | 182 (48) | 237 (47) |

| Psychological distress (Global Severity Index score 20), median (IQR)+ | 14 (9–18) | 15 (10–19) | 14 (8–18) |

| Quality of life (SF-6D score 21), median (IQR)+ | 17 (15–18) | 16 (15–18) | 17 (15–18) |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; ED emergency department.

Data were expressed as numbers (percentages), unless otherwise indicated.

P < .05

Variable included in covariate analyses

We also conducted a pair of additional analyses to examine secular effects, including seasonality and site experience with the intervention. In the first, we controlled for calendar month to address possible seasonality effects. In another, we adjusted for the effect of the relative length of time a site was engaged in a particular study phase (ranging from −0.5 for the first patient in a given phase to +0.5 for the last patient in a phase) to control for effects of experience and comfort with the study procedures. All analyses were performed with SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) or STATA version 14.1 (Stata Corp College Station, TX). All P-values were two-tailed, with P<0.05 considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

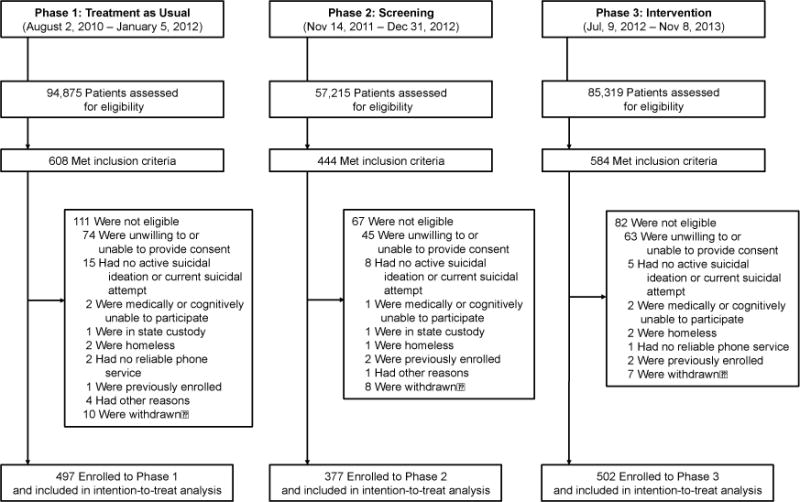

Of 1,636 patients who met the study inclusion criteria, we enrolled 1,376 participants; 497 in the TAU phase, 377 in the Screening phase, and 502 in the Intervention phase (Figure 1). The median age was 37 years (IQR, 26–47); 56% were female and 67% Non-Hispanic white. 72% of the sample had a history of previous suicide attempts and 33% had made an attempt in the week prior to ED visit. 87% of the sample had a psychiatric disorder and 69% also had a coexisting medical disorder. See Table 1 for other demographic and clinical characteristics.

Figure 1.

Of 1,376 enrolled participants, 1,089 patients (79%) had at least one completed telephone interview through 52 weeks; chart reviews were completed on 100% of participants.

Interventions

Secondary Suicide Screener

Chart review indicated that 449 (89%) of participants had received a suicide risk assessment from their physician, but only 17 (4%) had documentation of the ED-SAFE standardized secondary screener was used.

Safety Plan

Among those participants who completed the initial CLASP call, 114 (37%) reported having received a written safety plan in the ED.

CLASP

Among 502 participants in the Intervention phase, 305 participants (61%) completed at least 1 CLASP telephone call. Of those participants who completed at least one call, the median number of completed calls was 6 (IQR 2–7). 100 participants (20%) had a SO who completed at least one call. SOs completed a median of 4 calls (IQR 3–4).

Outcomes

Suicide Attempts

Overall, of 1,376 participants, 288 (21%) made at least one suicide attempt during the 12-month period. In the TAU Phase, 114 of 497 participants (23%) made a suicide attempt, as compared with 81 of 377 participants (22%) in the Screening Phase, and 93 of 502 participants (18%) in the Intervention Phase. Five attempts were fatal, with fatalities observed in TAU (n=2) and Intervention (n=3).

Of participants who reported an attempt, 164 (57%) made one attempt during the follow-up period; 53 (18%) made two attempts and 67 (23%) made three or more. When combined, there were 548 total suicide attempts among participants: 224 in the TAU Phase (0.45 per participant), 167 in the Screening Phase (0.44 per participant) and 157 in the Intervention Phase (.31 per participant).

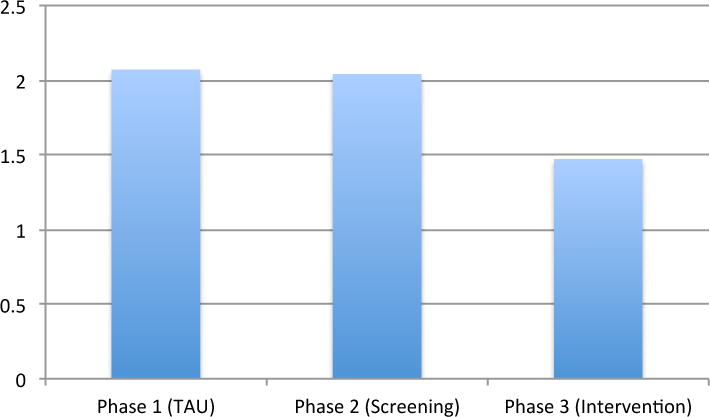

Primary Analyses

There were no meaningful differences in risk reduction between the TAU and Screening phases (Table 2). In contrast, when compared to the TAU Phase, participants in the Intervention Phase showed small but meaningful reductions in suicide risk (Table 2), with a relative risk reduction of 20% and the number needed to treat of 22. Participants in the Intervention Phase had 30% fewer total suicide attempts than participants in the TAU or Screening Phases (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Risk Reduction

| Suicidal Behavior | Absolute Risk Reduction | Relative Risk | Relative Risk Reduction | Number Needed to Treat | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment as Usual (TAU) vs. Screening Only (SO) | |||||

| Suicide Attempts | TAU - 23% (114/497) SO – 22% (81/377) | 0.1 (−.04 - .07) | .94 (.73–1.2) | −.06 (−.20 - .27) | 69 |

| Suicide Composite | TAU - 49% (243/497) SO – 50% (187/377) | .00 (−.07 - .06) | 1.0 (.89 –1.17) | −.02 (−.16 – 11) | 141 |

| Treatment as Usual (TAU) vs. Intervention (INT) | |||||

| Suicide Attempts | TAU – 23% (114/497) INT – 18% (93/502) | .05 (.00–.10 | .80 (.63–1.02 | .20 (02–.38 | 22 |

| Suicide Composite | TAU – 49% (243/497) INT – 41% (208/502) | .08 (.01–.14) | .85 (.74–.97) | .15 (.03–.26) | 13 |

95% Confidence Intervals in parentheses

Figure 2.

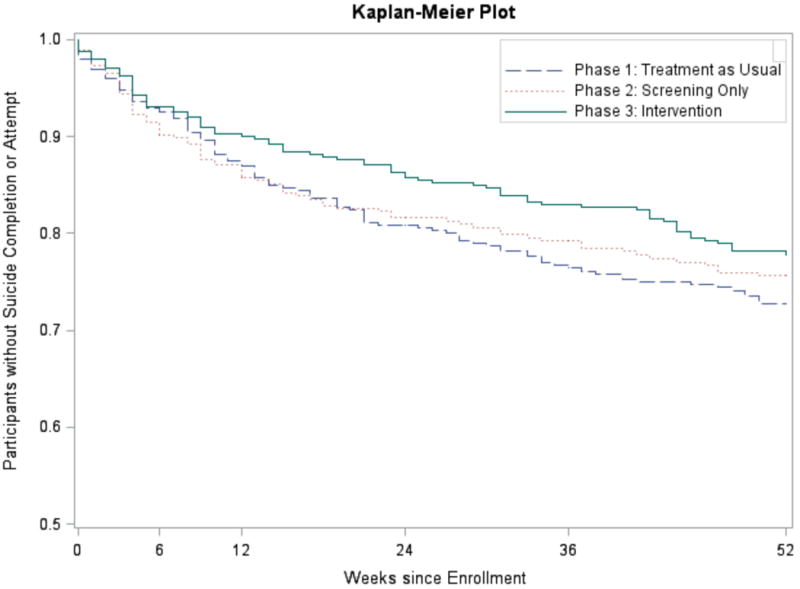

The survival curves for suicide attempts can be seen in Figure 3. Log rank tests indicated no significant differences between TAU and Screening phases (P=0.56). Comparisons of TAU and Intervention were associated with P-value of 0.08. Negative binomial regression analysis indicated that the participants in the Intervention Phase had significantly fewer total suicide attempts than participants in the TAU Phase (IRR, 0.72, 95%CI 0.52–1.00, P=0.05), but no differences between the TAU and Screening phases (IRR, 1, 95%CI 0.71–1.41, P=0.99). There were no significant site effects or site by treatment interactions.

Figure 3.

Secondary Analyses

Results from the multivariable Cox proportional hazards model indicated that compared with participants in the TAU phase, those in Screening phase had no significant difference in the proportion of participants making a suicide attempts (P=0.48) (Table S2). However, when compared with participants in the TAU phase, participants in the Intervention phase had a significant reduction in risk of suicide attempts (HR, 0.73; 95%CI, 0.55–0.97; P=0.03). Multivariable negative binomial regression analysis also indicated that participants in the Intervention phase had fewer total suicide attempts than those in the TAU phase (IRR, 0.75, 95%CI, 0.57–0.98,P =0.04) (Table S3).

There were no significant effects for either of the secular trend analyses (all Ps>0.10). Adding calendar month to the Cox models did not yield significant seasonal effects, nor change the results of these models. Similarly, there was no evidence of trends within each phase. (Tables S4, S5).

Suicide Composite

637 (46%) had one or more of the behaviors comprising the suicide composite. In the TAU Phase, 243 participants (49%) had a suicide composite outcome, as compared with 187 (50%) in the Screening Phase and 208 (41%) in the Intervention Phase. Results of analyses of the suicide composite largely mirrored those of the suicide attempt variable. We found no significant differences in the suicide composite between TAU and Screening phases. By contrast, survival (P=0.03), multivariate Cox (HR 0.78; 95%CI 0.64–0.94; P=0.01) and negative binomial (IRR-.78,95%CI, 0.65–0.93,P=0.01) analyses indicated participants in the Intervention Phase had significantly lower risk of overall suicidal behavior than those in the TAU Phase (Figure S1, Tables S6, S7).

DISCUSSION

This study is the largest suicide intervention trial ever conducted in the United States. Over 1300 participants with significant suicide risk from 8 EDs received either TAU, Universal Screening or Universal Screening plus an Intervention consisting of an expanded suicide screening and provision of a self-administered safety plan in the ED followed by a telephone-based intervention delivered during 52 weeks. The results indicated that the provision of Universal Screening, while successful in identifying more cases14, did not significantly impact subsequent suicidal behavior compared to that experienced by participants in the TAU Phase. By contrast, those participants who received the Intervention had lower rates of suicide attempts and behaviors and fewer total suicide attempts over a 52-week period. These results are consistent with other studies demonstrating the utility of contact following discharge from EDs 21,22.

The number needed to treat to prevent future suicidal behavior ranged between 13 and 22. This level of risk reduction compares favorably to other interventions to prevent major health issues, including: a) statins to prevent heart attack (NNT = 104),23 b) antiplatelet therapy for acute ischemic stroke (NNT= 143),24 and c) vaccines to prevent influenza in the elderly (NNT = 20)25.

Since our Intervention Phase had three components, we cannot identify their respective contributions to the observed reduction in suicidal behavior. Indeed, the implementation/compliance with all components of the intervention was less than optimal, with some participants not receiving portions of the intervention, either due to lack of implementation (standardized secondary screener, safety plan) or patient non-compliance (CLASP calls). In this report, we used conservative intent-to-treat analyses that included all participants regardless of their compliance. However, it should be noted that all participants in the Intervention Phase received substantial outreach via telephone messages and letters from CLASP advisors. It is possible that these “non-specific” expressions of concern and caring may have had a beneficial effect26,27 in the absence of completed telephone calls.

Although the procedures of this study did improve suicide risk detection rates14, we found no evidence that universal screening alone improved outcomes after the ED visit. However, the patients recruited for inclusion in the longitudinal follow-up of this study had all been identified clinically as having suicide risk and represent only a small subset of actual “screen positive” patients among the entire ED population. Potential advantages of universal screening may be seen with larger, population-based studies.

We also note that, for research and ethical reasons, participants in all phases, including TAU, received assessment calls to assess suicide risk, followed by potential referral to a suicide hotline. It is possible that these safety procedures decreased subsequent suicidal behavior across all phases. We believe that this insurmountable challenge of suicide prevention research may have reduced the potential differences between the TAU and Intervention phases.

Potential Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, we used sequential design instead of a randomized control trial. While our design allowed investigation of system-based interventions that would have been impossible with a traditional randomized controlled trial, it is possible that time or other non-study systemic changes may have produced differences in participant samples or other unknown factors across phases. While we controlled statistically for potential differences in samples and time by using multiple covariates and analyses of seasonality and experience with study procedures (Tables S1, S2, S3), other factors may have influenced outcomes. However, there were no major changes in treatment of suicidal individuals during the time of our study, both at the sites and nationwide, and national suicide rates remained constant or even increased over the study period1. Second, consistent with virtually every other suicide intervention trial, we did not have sufficient power to detect differences in actual deaths by suicide. While suicide attempts are an important public health issue,29 much larger trials will be necessary to adequately study the effect of interventions on suicide deaths.

Conclusions

In this multicenter study of ED patients with elevated suicide risk, we found that a multi-faceted intervention (composed of brief in-ED interventions and a series of telephone calls post-ED) produced a small but meaningful reduction (5%) in the proportion of participants who attempted suicide over the 12-month period. Moreover, the intervention led to a 30% reduction in the overall number of suicide attempts.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

Question

To determine if an ED-initiated intervention reduces subsequent suicidal behavior among a sample of high-risk ED patients.

Findings

When compared to treatment as usual, an intervention consisting of secondary suicide risk screening by the ED physician, discharge resources, and post-ED telephone calls focused on reducing suicide risk resulted in a 5% absolute decrease in the proportion of patients subsequently attempting suicide and a 30% decrease in total number of suicide attempts over a 52 week follow-up period.

Meaning

For ED patients at risk for suicide, a multi-faceted intervention can reduce future suicidal behavior.

Acknowledgments

On behalf of the ED-SAFE Investigators (Collaborators), including:

Marian E. Betz, MD, MPH, University of Colorado Hospital, Aurora, CO

Jeffrey M. Caterino, MD, The Ohio State University Medical Center, Columbus, OH

Brandon Gaudiano, PhD, Butler Hospital and Brown University, Providence, RI

Talmage Holmes, PhD, MPH, University of Arkansas Medical Center, Little Rock, AR

Maura Kennedy, MD, MPH, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA

Frank LoVecchio, DO, MPH, Maricopa Medical Center, Phoenix, AZ

Lisa A. Uebelacker, PhD, Memorial Hospital of Rhode Island, Providence, RI

Lauren Weinstock, PhD, Butler Hospital and Brown University, Providence, RI

Wesley Zeger, DO, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE

Role of the Sponsor: The project described was supported by Award Number U01MH088278 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The National Institute of Mental Health had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Abbreviations

- ED

Emergency department

- ED-SAFE

Emergency Department Safety Assessment and Follow-up Evaluation

- CLASP

Coping Long Term with Active Suicide Program

Footnotes

Access to Data and Data Analysis. Richard Jones, ScD., Kohei Hasegawa, MD, MPH had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Trial Registration: Emergency Department Safety Assessment and Follow-up Evaluation (ED-SAFE) ClinicalTrials.gov: (NCT01150994)

https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01150994?term=ED-SAFE&rank=1

References

- 1.Drapeau CW, McIntosh JL. Official final data. Washington, DC: American Association of Suicidology; 2016. Suicidology ftAAo U.S.A. Suicide 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown GK, Ten Have T, Henriques GR, Xie SX, Hollander JE, Beck AT. Cognitive therapy for the prevention of suicide attempts: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;294:563–70. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.5.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linehan MM, Comtois KA, Murray AM, et al. Two-year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy vs therapy by experts for suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 2006;63:757–66. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rudd MD, Bryan C, Wertenberger E, et al. Brief Cognitive-behavioral therapy effects on post-treatment suicide attempts in a military sample: Results of a randomized clinical trial with 2-year follow-up. Amer J Psychiatr. 2015 doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14070843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tarrier N, Taylor K, Gooding P. Cognitive-behavioral interventions to reduce suicide behavior: a systematic review and meta analysis. Behavior Modification. 2008;32:77–108. doi: 10.1177/0145445507304728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milner A, Carter G, Pirkis J, Robinson J, Spittal M. Letters, green cards, telephone calls and postcards: systematic and meta-analytic review of brief contact interventions for reducing self-harm, suicide attempts and suicide. Brit J Psychiatr. 2015;206:184–90. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.147819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Owens P, Mutter R, Stocks C. Mental health and substance abuse-related emergency department visists among adults 2007. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ting S, Sullivan A, Boudreaux E, Miller IW, Camargo C. Trends in US emergency department visists for attempted suicide and self-inflicted injury, 1993–2008. Gen Hosp Psychiatr. 2012;34:557–65. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olfson M, Marcus SC, Bridge J. Focusing suicide prevention on periods of high risk. JAMA. 2014 Feb; doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmedani B, Simon G, Stewart C, et al. Health care contacts in the year before suicide death. J Gen Int Med,Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2014;29(6):870–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2767-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gairin I, House A, Owens D. Attendance at the accident and emergency department in the year before suicide: a retrospective study. Brit J Psychiatr. 2003;183:28–33. doi: 10.1192/bjp.183.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DaCruz D, Pearson A, Saini P, et al. Emergency department contact prior to suicide in mental health patients. Emer Med J Emergency Medicine Journal. 2011;28:467–71. doi: 10.1136/emj.2009.081869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boudreaux E, Miller IW, Goldstein A, et al. The Emergency Department Safety Assessment and Follow-up Evaluation (ED-SAFE): Method and design considerations. Cont Clin Trial,Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2013;36:14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boudreaux E, Camargo C, Arias S, et al. Improving Suicide Risk Screening and Detection in the Emergency Department. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50:445–53. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arias S, Sullivan A, Miller I, Camargo C, Boudreaux E. Implementation and use of a crisis hotline during the treatment as usual and universal screening phases of a suicide intervention study. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;45:147–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller I, Gaudiano B, Weinstock L. The Coping Long Term with Active Suicide Program: Description and Pilot Results. Suicide and Life Tthreat Beh. 2016;46:752–761. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatr. 2011;168:1266–77. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hawton K, Townsend E, Arensman E, et al. Psychosocial versus pharmacological treatments for deliberate self harm. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000:CD001764. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Owens D, Horrocks J, House A. Fatal and non-fatal repetition of self-harm: Systematic review. Brit J Psychiatr. 2002;181:193–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.181.3.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hess K. Graphical methods for assessing ciolations in teh proportional hazards assumption in Cox regression. Stat Med. 1995;15:1707–23. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780141510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fleischmann A, Bertolote J, Wasserman D, DeLeo D, Bolhari J, Botega N. Effectiveness of brief intervention and contact for suicide attempters: a randomized controlled trial in five countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2008;86:703–9. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.046995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vaiva G, Vaiva G, Ducrocq F, et al. Effect of telephone contact on further suicide attempts in patients discharged from an emergency department: randomised controlled study. Brit Med J. 2006;332:1241–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7552.1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ray K, Seshasai S, Erqou S, et al. Statins and all-cause mortality in high-risk primary prevention: a meta analysis of 11 randomized controlled trials involving 65,229 participants. Arch Int Med. 2010;170:1024–31. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sandercock P, Counsell C, Tseng M. Antiplatelet therapy for acute ischaeic stroke. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000029.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Demicheli V, Rivetti D, Deeks J, Jeffferson T. Vaccines for preventing influenza in health adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2000 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carter G, Clover K, Whyte I, Dawson A, D’Este C. Postcards frm the EDge: 24 month outcomes of a randomized conrolled trial for hospital-treated self-poisoning. Brit J Psychiatr. 2007;191:548–53. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.038406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Motto JA, Bostrom AG. A randomized controlled trial of postcrisis suicide prevention. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:828–33. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.6.828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Control NCfIPa. 10 Leading Cause of Death in the United States - 2013. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wortzel H, Gutierrez PM, Homaifar B, Breshears R, Harwood J. Surrogate endpoints in suicide research. Suicide Life Threat Beh. 2010;40:500–5. doi: 10.1521/suli.2010.40.5.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.