Virus replicate inside prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. Outside cells, they exist as independent particles (i.e. virions) generally composed of a protein shell (sometimes covered with a lipid bilayer) that contains their genetic material made of RNA or DNA. Virus genome replication and transcription are catalyzed by virally encoded polymerases. Although all these enzymes show some homology and share structural features and their catalytic mechanism, they also have important differences that reflect diverse virus replication strategies.

During the last few years we have witnessed significant developments in our knowledge on the structure and function of many viral polymerases. Much of this research has enabled developing effective pharmacological interventions for the treatment of viral infections responsible for diseases such as acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) or acute or chronic hepatitis. Examples are tenofovir, a reverse transcriptase inhibitor that blocks human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis B virus replication, or sofosbuvir, a recently approved nucleoside analogue that inhibits hepatitis C virus RNA polymerase.

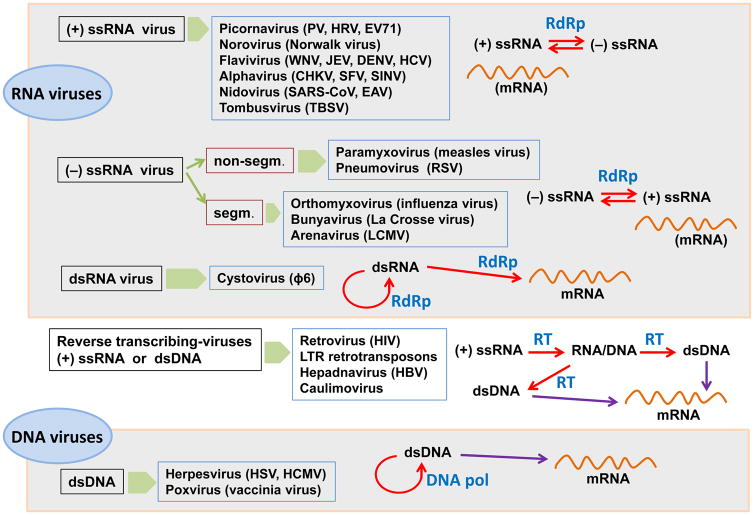

This Special Issue is a collection of review articles summarizing our current understanding on viral polymerases. We cover major virus families with different replication mechanisms (Fig. 1). A particular emphasis has been placed on polymerase structure/function relationship. However, while for some virus families polymerase structure and function has been extensively studied (e.g. poliovirus (Peersen, 2017), flavivirus (Gong, 2017), cystovirus (Alphonse and Ghose, 2017) and retrovirus (Menéndez-Arias et al., 2017)), there is an important lack of structural information in the case of alphavirus (Pietilä et al., 2017), nidovirus (Posthuma et al, 2017) or poxvirus (Czarnecki and Traktman, 2017).

Fig. 1.

Viral replication mechanisms and overview of virus genera whose polymerases are covered in this special issue. Viruses are clustered according to their genomes and replication strategies, as proposed by David Baltimore in 1971 (Baltimore, 1971). Abbreviations used are: CHKV, Chikungunya virus; DENV, dengue virus; DNA pol, DNA polymerase; dsDNA, double-stranded DNA; dsRNA, double-stranded RNA; EAV, equine arteritis virus; EV71, enterovirus 71; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCMV, human cytomegalovirus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HRV, human rhinovirus; HSV, herpes simplex virus; JEV, Japanese encephalitis virus; LCMV, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus; LTR, long terminal repeat; PV, poliovirus; RdRp, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus; RT, reverse transcriptase; SARS-CoV, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus; segm., segmented; SFV, Semliki Forest virus; SINV, Sindbis virus; ssRNA, single-stranded RNA; TBSV, tomato bushy stunt virus; WNV, West Nile virus

Positive-sense single-stranded RNA ((+) ssRNA) viruses are represented by polioviruses (Peersen, 2017), noroviruses (Deval et al., 2017), flaviviruses (Lu and Gong, 2017), alphaviruses (Pietilä et al., 2017), nidoviruses (Posthuma et al, 2017) and tombusviruses (Gunawardene et al., 2017). These viruses encode RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (RdRp) that share with eukaryotic DNA polymerases the characteristic fingers-palm-thumb subdomain arrangement. However, they show unique extensive interactions between the fingers and thumb subdomains that contribute to the formation of a well-defined template channel (Peersen, 2017; Lu and Gong, 2017). The poliovirus polymerase is the smallest viral polymerase and recent studies have been focused on how to modulate its fidelity of RNA synthesis, as a potential strategy to use in the development of attenuated vaccines (Peersen, 2017). Norovirus polymerases share a very similar structure, and it has received attention as a target of drugs currently in development. In their review, Deval et al., 2017 discuss on nucleoside analogues (e.g. ribavirin, favipiravir, 2′-C-methyl-cytidine) and nonnucleoside RdRp inhibitors (e.g. suramin) active in vitro against the human norovirus polymerase.

A comparative analysis of the polymerases of several flaviviruses is presented by Lu and Gong (2017). In these polymerases, the RdRp domain is fused to a methyltransferase domain, forming the so-called NS5 protein. Unlike poliovirus and norovirus RdRps, the flavivirus enzymes do not use a primer to initiate RNA synthesis. The mechanisms of de novo initiation of RNA synthesis and the dynamic interplay of methyltransferase and polymerase domains are major areas of interest in current research.

In contrast to RdRps described above, there is no structural information available for alphavirus and nidovirus polymerases. In alphaviruses (Pietilä et al., 2017), the polymerase nsP4 requires host factors to be active, while in nidoviruses, the size and complexity of the viral genome (up to 26–34 kb in coronaviruses) demand more sophisticated replication and transcription strategies that involve host and viral factors (Posthuma et al, 2017). Viral proteins such as nsp1 and a 3′→5′ exonuclease (nsp14) have been identified as important components of nidovirus replication complexes. Another example illustrating the importance of viral and host cofactors (including membrane factories) is provided by Gunawardene et al. (2017) that present advances in tombusvirus replication. The three-dimensional structure of the polymerase (p92) of this plant virus is not known, although some features might be inferred from its partial homology with the hepatitis C RdRp.

The genomes of negative-sense single-stranded RNA viruses ((−) ssRNA) can be either nonsegmented or segmented. Segmented genomes are found in influenza virus that contains eight viral RNA segments or in arenaviruses with two RNA molecules. The RNA polymerases of all these viruses are large enzymes that usually contain three domains (or different subunits), including the RdRp and a capping domain. Fearns and Plemper (2017) review current knowledge on the multifunctional complexes of paramyxo- and pneumovirus polymerases. In the absence of a crystal structure for those enzymes, the vesicular stomatitis virus RdRp (L protein) structure provides a useful framework for understanding structure-function relationships of paramyxo- and pneumovirus polymerases.

Progress in deciphering and understanding the structure of influenza virus polymerase is covered by Pflug et al. (2017). Recent work has provided novel insights in the “cap-snatching” mechanism and crystal structures will be helpful to design novel drugs acting against different targets within the influenza virus polymerase (i.e. cap-binding domain, or the endonuclease and RdRp activities). Favipiravir is a novel nucleoside analogue in clinical trials developed against influenza that is also active against other viral RNA polymerases (see review by Deval et al., 2017). Further insight in segmented (−) ssRNA viruses is given in Ferron et al. (2017) who discuss on the high-resolution structure of La Crosse virus (a bunyavirus) and its “cap-snatching” mechanism. Functional and structural similarities of the bunyavirus and arenavirus polymerases are described in detail in this review.

The polymerases of double-stranded RNA viruses (dsRNA) are represented by P2, the RdRp of the Pseudomonas phage Φ6 (Alphonse and Ghose, 2017). Cystoviruses such as Φ6 have segmented genomes and their virions contain the polymerase P2. This is because the genomic dsRNA cannot be used as mRNA for transcription and translation by host polymerases. The Φ6 polymerase shows significant homology with poliovirus and hepatitis C virus RdRps. Its crystal structure has been determined but a high-resolution elongation complex is not available. Studies on its conformational dynamics using optical tweezers are covered in this review, aimed at a better understanding of how nucleotide selectivity is controlled during RNA elongation.

Reverse transcriptases of retroviruses and pararetroviruses are covered in the article by Menéndez-Arias et al. (2017). This is a comprehensive review where the structure and function of reverse transcriptases from different virus families are compared. HIV reverse transcriptase has been widely studied for the last 30 years and not surprisingly, receives a lot of attention, focusing the discussion on its structure, biochemistry and inhibition, as major topics of research in the field. Animal and plant pararetroviruses are represented by hepadnaviruses and caulimoviruses, respectively. Interestingly, although the hepatitis B virus polymerase structure is not available, its similarity to HIV type 1 reverse transcriptase has guided successful drug discovery programs searching for effective drugs to treat hepatitis B.

The last group of viruses is represented by those having a genomic double-stranded DNA (dsDNA). Herpes simplex virus and human cytomegalovirus encode B family DNA polymerases (UL30 and UL54, respectively), whose structure and function is described in the review by Zarrouk et al. (2017). These are multifunctional enzymes with DNA polymerase, 3′→5′ exonucleotide proofreading and ribonuclease H activities, that act in complex with processivity factors. The crystal structure of the UL30 polymerase has been determined in its apoenzyme form, although valuable information has been also inferred from its extensive homology with the bacteriophage RB69 DNA polymerase. Studies on the vaccinia virus polymerase (a poxvirus representative) are covered in the last review of the special issue (Czarnecki and Traktman, 2017). As in herpesvirus, the vaccinia virus polymerase (E9) associates with a processivity factor that in this case is a heterodimer containing a protein A20 and uracyl DNA glycosylase. A crystal structure of a truncated heterodimer is available, but the structure of E9 has not been solved. The review by Czarnecki and Traktman (2017) provides a historical account of 40 years of research on poxvirus polymerases, including relevant aspects on how viral and host factors modulate their activity.

Finally, we would like to thank Luis Enjuanes for his enthusiastic support of this project, and all authors for their timely contributions to this special issue. We also thank reviewers for their constructive critiques that helped to improve all manuscripts. We hope that this volume will contribute towards a better understanding of viral polymerases, while encouraging research and promoting interest in their study among graduate students and young scientists.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Luis Menéndez-Arias, Centro de Biología Molecular “Severo Ochoa”, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, and Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, c/ Nicolás Cabrera, 1, Campus de Cantoblanco, 28049 Madrid, Spain.

Raul Andino, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of California at San Francisco, MBGH S572E, Box 2280, 600 16th Street, San Francisco, CA 94158, USA.

References

- Alphonse S, Ghose R. Cystoviral RNA-directed RNA polymerases: regulation of RNA synthesis on multiple time and length scales. Virus Res. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2017.01.006. this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltimore D. Expression of animal virus genomes. Bacteriol Rev. 1971;35:235–241. doi: 10.1128/br.35.3.235-241.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czarnecki MW, Traktman P. The vaccinia DNA polymerase and its processivity factor. Virus Res. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2017.01.027. this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deval J, Jin Z, Chuang Y-C, Kao CC. Structure(s), function(s), and inhibition of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of noroviruses. Virus Res. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2016.12.018. this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearns R, Plemper R. Polymerases of paramyxoviruses and pneumoviruses. Virus Res. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2017.01.008. this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferron F, Weber F, de la Torre JC, Reguera J. Transcription and replication mechanisms of Bunyaviridae and Arenaviridae L-proteins. Virus Res. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2017.01.018. this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunawardene C, Donaldson L, White KA. Tombusvirus polymerases: Structure and function. Virus Res. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2017.01.012. this issue. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu G, Gong P. A structural view of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerases from the Flavivirus genus. Virus Res. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2017.01.020. this issue. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menéndez-Arias L, Sebastián-Martín A, Álvarez M. Viral reverse transcriptases. Virus Res. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2016.12.019. this issue. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peersen OB. Picornaviral polymerase structure, function and fidelity modulation. Virus Res. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2017.01.026. this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pflug A, Lukarska M, Resa-Infante P, Reich S, Cusack S. Structural insights into RNA synthesis by the influenza virus transcription replication machine. Virus Res. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2017.01.013. this issue. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietilä M, Hellström K, Ahola T. Alphavirus polymerase and RNA replication. Virus Res. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2017.01.007. this issue. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posthuma CC, te Velthuis AJW, Snijder EJ. Nidovirus RNA polymerases: complex enzymes handling exceptional RNA genomes. Virus Res. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2017.01.023. this issue. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarrouk K, Piret J, Boivin G. Herpesvirus DNA polymerases: Structures, functions and inhibitors. Virus Res. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2017.01.019. this issue. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]