Abstract

Importance

Care planning is a critical function of palliative care teams, but the impact of advance care planning and goals of care discussions by palliative care teams has not been well characterized.

Objective

Describe the population of patients referred to inpatient palliative care consult teams for care planning, the needs identified by palliative care clinicians, the care planning activities that occur, and the results of these activities.

Design

Prospective cohort study conducted between January 1, 2013 and December 31, 2016.

Setting

Seventy-eight inpatient palliative care teams from diverse United States hospitals in the Palliative Care Quality Network, a national quality improvement collaborative.

Participants

Standardized data were submitted for 78,145 patients.

Exposure

Inpatient palliative care consultation.

Results

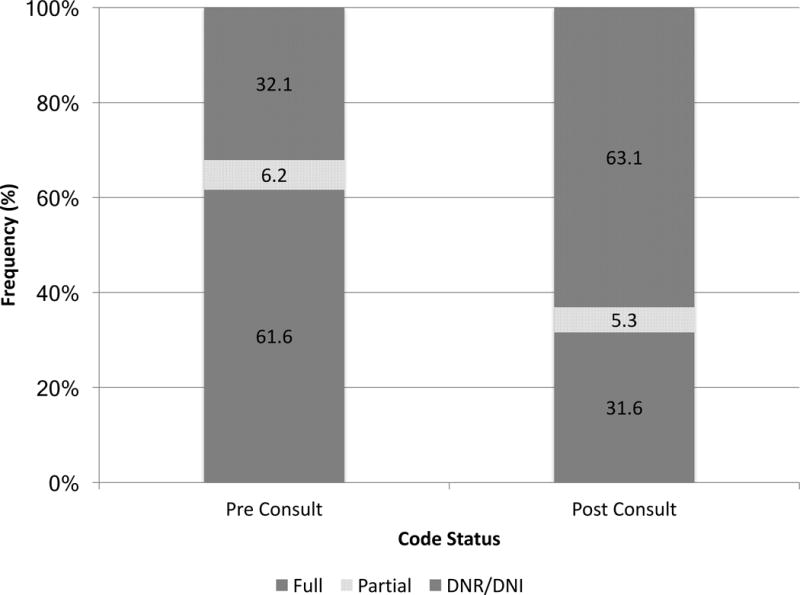

Overall, 71.9% (52,571/73,145) of patients referred to inpatient palliative care were referred for care planning (range between hospitals: 27.5%-99.4%). Patients referred for care planning were older (73.3 vs. 67.9 years; p<0.0001), less likely to have cancer (30.0% vs. 41.1%; p<0.0001), and were slightly more often Full Code at the time of referral (54.6% vs. 52.1%; p<0.0001). Palliative care teams identified care planning needs in 72.2% (52,825/73,145) of patients overall, including in 85.4% (42,467/49,713) of patients referred for care planning and in 57.5% (10,054/17,475) of patients referred for other reasons. Through care planning conversations, surrogates were identified for 94.8% of patients and 37.4% of patients elected to change their code status. Substantially more patients indicated that a status of Do Not Resuscitate/Do Not Intubate was consistent with their goals (32.1% pre-consult to 63.1% post-consult). However, an advance directive was completed for just 3.2% of patients and a Physicians Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment form was completed for 12.3% of patients seen by palliative care.

Conclusions and Relevance

Care planning was the most common reason for inpatient palliative care consultation and care planning needs were often found even when the consult was for other reasons. Surrogates were consistently identified and patients’ preferences regarding life-sustaining treatments were frequently updated. However a minority of patients completed legal forms to document their care preferences, highlighting an area in need of improvement.

Introduction

Advance care planning (ACP) is “a process that supports adults at any age or stage of health in understanding and sharing their personal values, life goals, and preferences regarding future medical care. The goal of advance care planning is to help ensure that people receive medical care that is consistent with their values, goals and preferences during serious and chronic illness.”1 Goals of care (GOC) discussions have a similar goal as ACP and overlap with it, but typically pertain to more proximal decisions.1–3 Advance care planning and GOC discussions often occur through a series of conversations over time. Specific wishes, such as preferences for life-sustaining treatments, can be documented in an advance directive (AD) or Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) form to direct future health care. When done effectively, ACP and GOC discussions have been shown to increase the percentage of patients who receive care consistent with their previously expressed wishes, improve patient and family satisfaction, and decrease anxiety and depression in bereaved family members.4–8

Advance care planning and GOC discussions are critical functions of palliative care (PC) teams. The National Consensus Project, which seeks to define and promote high-quality PC, has described care planning as a core competency for PC teams.9 National training programs focus on ACP as an essential skill for PC physicians.10 Further, the Joint Commission’s Advanced Certification Program for PC requires that PC clinicians document care plans for all patients they see.11 Despite these guidelines, the nature of the ACP and GOC discussions requested of and performed by inpatient PC teams has not yet been described in a diverse sample of PC teams in the United States. Using the Palliative Care Quality Network (PCQN) database, a registry of patient-level, standardized data collected by PC clinicians about inpatients referred for consultation, we sought to characterize the care planning performed by PC teams. Specifically, we examined which patient characteristics are associated with referral to PC for ACP or GOC discussions, ACP or GOC needs identified by PC clinicians, and the results of ACP or GOC conversations.

Methods

The Palliative Care Quality Network

The PCQN is a large, multisite collaborative of interdisciplinary PC teams that collect standardized data about their patients and practice in order to benchmark processes of care and outcomes, identify best practices, and drive quality improvement.12 As of December 31, 2016, there were 78 PC teams entering patient-level data into the PCQN database from a diverse group of academic and community hospitals in eleven states in the United States.

Dataset

The 23-item PCQN core dataset includes patient demographics, actions taken by PC teams, and clinical outcomes. Demographic information includes patient age, gender, primary diagnosis, and Palliative Performance Scale score.13 Process measures include date of the PC referral, reason(s) for the PC consult (e.g. ACP/GOC, pain management, comfort care), PC disciplines involved in the consult (e.g. physician, social worker, nurse, chaplain), PC needs screened for (e.g. ACP/GOC, pain, other symptoms, psychosocial and spiritual needs) and results of the screen, PC needs intervened upon by the PC team (the PCQN defines a PC intervention as a concerted effort to address a particular need, which does not necessarily lead to resolution of the need), number of family meetings conducted, whether code status was clarified (meaning that it was specifically discussed with the patient or surrogate and either confirmed or changed), completion of ACP forms such as an AD or POLST form, and services arranged upon hospital discharge (e.g. hospice, home-based PC). Patient-level outcomes are also documented including daily symptom scores for pain, dyspnea, nausea, and anxiety, code status, and survival to hospital discharge. There are additional optional data elements that teams can choose to collect, including whether a surrogate decision maker was documented and code status at discharge. The majority of optional data elements have been added since the introduction of the core dataset in response to needs identified by teams in the PCQN; they are not collected by all teams. A full list of the PCQN data elements is available at www.pcqn.org.

Of note, ACP and GOC were combined into “ACP/GOC” in PCQN data elements in recognition that these two processes are often performed concurrently for seriously ill inpatients and are difficult for clinicians to consistently distinguish.1–3 For readability we have used the term “ACP” or “care planning” rather than “ACP/GOC” through the majority of this manuscript, but recognize that some of these conversations would be more accurately and specifically described as GOC conversations particularly when they address very proximal decisions.

For the purposes of the PCQN, a PC consultation is defined as the series of PC visits that occur for a single patient during a single hospitalization. Clinicians are encouraged to enter data for all 23 of the core data elements for every patient they see during the consultation. However, as the PCQN database is primarily used for quality improvement and data are collected by clinicians in the course of usual patient care, not all data elements are completed for every patient. There is no effort to obtain missing data.

The data for this study were extracted on February 2nd, 2017 and include the PC consultation records of patients who received consultation requests between January 1st, 2013 and December 31st, 2016. This study was reviewed and approved by the UCSF Institutional Review Board (#16-18596).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics (frequencies, means, standard deviation [SD], and range) were used to examine the distribution of measures, as appropriate. We used chi-square (χ2) analysis to test for bivariate associations between categorical variables and analysis of variance (ANOVA) to examine the association between patient characteristics, PC team activities, and outcomes of care as well as whether a patient was referred to PC for ACP/GOC. From these analyses, independent variables that were significant at p≤0.10 were included in a multivariate logistic regression model to identify predictors associated with patients being referred to PC for ACP/GOC. The categorical variable of ‘PC teams’ was included as a fixed–effect to adjust for any potential variation between the teams. To analyze change in code status during PC consult, a McNemar–Bowker test was performed. An alpha of ≤0.05 was used to determine statistical significance. There was no adjustment or imputation for missing data; we only performed analyses for patients for whom data was available for each specific data element, resulting in variations in n values for each analysis. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Mac (version 23) was used to conduct all analyses.

Results

Referrals for advance care planning

There were 73,145 PC consultations by 78 PC teams during our study period. Advance care planning was the most common reason for PC consultation (71.9%, 52,571/73,145). However, the percent of referrals for ACP varied between teams (range between teams: 27.5% - 99.4%). Of patients referred for ACP, 54.0% (28,414/52,571) were referred only for that reason. The other 46.0% of patients (n=24,157) who were referred to PC for ACP were also referred for additional reasons such as referral to hospice (37.4%, n=9026), pain management (30.2%, n=7296), other symptom management (28.8%, n=6950), transition to comfort care (12.5%, n=3017), and withdrawal of interventions (8.0%, n=1923). Palliative care consultation requests occurred on average 4.7 days (95%CI: 4.3, 5.1) after hospital admission. We found no differences (F=1.5, p=0.2) in the hospital length of stay (LOS) prior to the PC consultation request for patients referred for ACP (4.6 days, 95%CI: 4.5, 4.7) or for other reasons (4.8 days, 95%CI: 4.4, 5.2).

Univariate analyses revealed that patients referred to PC for ACP were older than those referred for other reasons (73.3 years v. 67.9 years, p<0.0001), had lower palliative performance scale scores (34.2 v. 37.2, p<0.0001), were less likely to have cancer (30.0% v. 41.1%, p<0.0001), and were slightly more likely to have a clinical order of Full Code at the time of PC consultation request (54.6% v. 52.1%, p<0.0001) (Table 1). Patients referred for ACP were also more likely to have a POLST form in the medical record at the time of referral to PC (12.4% vs. 9.7%, p<0.001), but no more likely to have an advance directive at the time of referral (22.7% v. 21.2%, p=0.06).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics associated with referral to PC for ACP

| Characteristic | Referral for ACP/GOC* | Referral for other reason(s) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age: (years) | N= 52,524 | N= 19,426 | F | |

| Mean (95%CI) | 73.3 (73.2, 73.4) | 67.9 (67.9, 68.2) | 1546.0 | <0.0001 |

| Sex: % (n) | N= 52,543 | N= 19,449 | X2 | |

| Female | 50.6 (26,576) | 53.7 (10,440) | 54.6 | <0.0001 |

| Male | 49.4 (25,967) | 46.3 (9,009) | ||

| Palliative Performance Scale score: | N= 46,658 | N= 15,922 | F | |

| Mean (95%CI) | 34.2 (34.1, 34.4) | 37.2 (36.9, 37.6) | 293.1 | <0.0001 |

| Primary diagnosis: % (n) | N= 51,499 | N= 18,593 | X2 | |

| Cancer | 30.0 (15,472) | 41.1 (7,645) | 878.0 | <0.0001 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 14.2 (7,333) | 9.4 (1,743) | ||

| Pulmonary disease | 11.9 (6,115) | 9.4 (1,748) | ||

| Neurologic disease | 10.2 (5,313) | 9.3 (1,730) | ||

| Other | 33.5 (17,266) | 30.8 (5,727) | ||

| Level of care at time of PC referral: % (n) | N= 52,330 | N= 19,272 | 1207.0 | <0.0001 |

| Medical/surgical unit | 38.5 (20,140) | 44.4 (8,566) | ||

| Critical care unit | 25.4 (13,266) | 19.6 (3,778) | ||

| Telemetry/step-down unit | 27.3 (14,311) | 20.3 (3,916) | ||

| Other | 8.8 (4,613) | 15.6 (3,012) | ||

| Code status at time of PC referral: % (n) | N= 51,263 | N= 18,095 | 85.2 | <0.0001 |

| Full code | 54.6 (28,001) | 52.1 (9,429) | ||

| Partial code | 6.5 (3,338) | 5.4 (980) | ||

| DNR/DNI | 38.9 (19,924) | 42.5 (7,686) | ||

| AD at time of PC referral: % (n) | N= 50,962 | N= 18,460 | ||

| 22.7 (11,574) | 21.2 (3,921) | 16.9 | <0.0001 | |

| POLST at the time of PC referral: % (n) | N= 49,692 | N= 18,093 | ||

| 12.4 (6,137) | 9.7 (1,747) | 93.7 | <0.0001 | |

| Hospital LOS prior to consult request: | N= 52,185 | N= 19,104 | F | <0.0001 |

| Mean days (95%CI) | 4.5 (4.3, 4.6) | 4.7 (4.3, 5.1) | 2.1 |

Patients in ACP/GOC group may have additional reasons for PC consult identified by the referring team.

After adjusting for all characteristics that were significantly associated with referral for ACP in the univariate analyses, and accounting for differences between PC teams, multivariate logistic regression showed that men were more likely to be referred for ACP (OR 1.12, 95%CI: 1.07, 1.16; Table 2), as were patients with cardiovascular (OR 1.33, 95%CI: 1.23, 1.43) or pulmonary disease (OR 1.22, 95%CI: 1.13, 1.31), and those in telemetry/step down (OR 1.63, 95%CI: 1.55, 1.73) or intensive care units (OR 1.54, 95%CI: 1.45, 1.63). Patient with a code status of DNR/DNI were less likely to be referred to PC for ACP (OR 0.6, 95%CI: 0.57, 0.63).

Table 2.

Logistic regression identifying characteristics associated with referral to PC for ACP/GOC

| Characteristic | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.02 (1.01, 1.02) | <0.0001 |

| Sex: | ||

| Female | 1.0 | |

| Male | 1.12 (1.07, 1.16) | <0.0001 |

| Palliative Performance Scale score | 0.99 (0.99, 0.99) | <0.0001 |

| Primary diagnosis: | ||

| Cancer | 1.0 | |

| Cardiovascular disease | 1.33 (1.23, 1.43) | <0.0001 |

| Pulmonary disease | 1.22 (1.13, 1.31) | <0.0001 |

| Neurologic disease | 1.00 (0.93, 1.08) | 0.98 |

| Other | 1.15 (1.09, 1.21) | <0.0001 |

| Level of care at time of referral: | ||

| Medical/surgical unit | 1.0 | |

| Critical care unit | 1.54 (1.45, 1.63) | <0.0001 |

| Telemetry/step-down unit | 1.63 (1.55, 1.73) | <0.0001 |

| Other | 0.78 (0.73, 0.84) | <0.0001 |

| Code status: | ||

| Full code | 1.0 | |

| Partial code | 0.95 (0.87, 1.04) | 0.30 |

| DNR/DNI | 0.60 (0.57, 0.63) | <0.0001 |

| PC team | Data not included | <0.0001 |

Needs identified by palliative care teams

During the consultation, PC teams identified ACP needs in 72.2% (52,825/73,145) of patients overall, which included 85.4% (42,467/49,713) of the patients who were referred for ACP and 57.5% (10,054/17,475) of the patients who were not referred for ACP. Palliative care teams addressed ACP needs in 94.2% (39,981/42,458) of patients who were referred for ACP. Even among patients referred to PC for reasons other than ACP, the large majority had their ACP needs addressed by the PC team when they were found (91.7%, 9220/10,053).

Forty percent of the patients referred for ACP (with or without additional reasons) reported having pain (40.2%, 20,131/50,062) and other symptoms (46.2%, 23,134/50,062) when assessed by the PC team. Psychosocial and spiritual needs were also common regardless of the reason for PC referral (50.6%, 24,046/49,524 and 27.0%, 13,238/49,055, respectively). In the majority of cases where additional needs were identified, PC clinicians addressed these needs even though the consult was requested for ACP (pain was addressed in 88.4% of the cases where it was identified, 17,796/20,126; other symptoms 89.5%, 20,703/23,131; psychosocial needs 92.6%, 23,181/25,047; and spiritual needs 90.2%, 14,926/16,539).

Advance care planning activities and results

Palliative care consults for ACP involved doctors (52.2%, 25,802/49,408), social workers (39.8%, 19,672/49,408), chaplains (32.8%, 16,210/49,408), and registered nurses (37.0%, 18,305/49,408). Patients were followed by the PC team for an average of 5.5 days (median= 3.0; range between teams: 3.3 – 9.8) and PC teams had an average of 1.4 family meetings (median=1.0; range between teams: 0.3 – 4.1) throughout the course of the consultation. Based on data from the subset of 57 teams that collected data for the optional data element of surrogate decision maker documented, surrogates were identified for 94.8% of patients (10,571/11,149; range between teams: 71.1% – 100%).

We found a significant change in the distribution of patients’ code status orders from the time of referral to PC to the conclusion of the PC consultations (Figure 1). Of patients for whom the optional data element of code status at the conclusion of the PC consult was documented, we found that 37.4% of patients changed their code status in the course of the PC consult. It was more common for patients who were initially Full Code to change their code status to express a preference for less aggressive treatment (51.5%, n=6933), but 4.2% of patients (n=292) who were initially DNR/DNI changed their code status to express a preference for more aggressive treatment. Even among patients who had completed an AD or POLST form prior to the PC referral, indicating that they had previously engaged in ACP, many patients changed their code status during the course of the PC consult (34.9% of patients who had previous completed an AD and 27.1% of patients who had previously completed a POLST form changed their code status).

Figure 1. Change in code status during PC consultation.

McNemar – Bowker test: p< 0.0001; N= 21,827

Despite the fact that patients’ surrogate decision maker and code status were frequently clarified, an AD was completed for just 3.2% of patients (2160/67,955; range between teams: 0% – 27.3%) and a POLST form was completed for 12.3% of patients (8359/67,955, range between teams: 0% – 50.7%). Even among patients who expressed a preference to limit life-sustaining treatments (e.g. DNR/DNI or Partial Code status), survived until hospital discharge, and were followed by the PC team until the end of the hospitalization, AD and POLST forms were infrequently completed (for 4.3%, 467/10,987 and 29.0%, 3184/10,987 of patients, respectively). Among patients discharged to an extended care facility, where POLST forms are required in many states, a POLST was completed for 18.4% (2103/11,405) of patients overall and for 31.0% (852/2749) of patients who had a preference to limit life-sustaining treatments at the time of hospital discharge.

All aspects of ACP were more common among patients referred to PC for ACP, but PC teams also commonly engaged in ACP with patients who were referred for other reasons (Table 3). There was no significant difference in the hospital length of stay between patients who had ACP addressed by the PC team (10.0 days, 95%CI: 9.8, 10.2) and those who did not (9.7 days, 95%CI: 9.4, 10.2, p=0.13).

Table 3.

ACP/GOC activities and outcomes of PC consults

| Activities and Outcomes | Referral for ACP/GOC* | Referral for other reason(s) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surrogate decision maker: % (n) | N= 11,149 | N= 3,264 | X2 | |

| Addressed, identified | 94.8 (10,571) | 93.1 (3,038) | 40.7 | <0.0001 |

| Addressed, none identified | 3.1 (348) | 2.9 (94) | ||

| Not addressed | 2.1 (230) | 4.0 (132) | ||

| Number of family meetings: Mean (95% CI) | N= 47,824 | N= 15,705 | F | |

| 1.4 (1.38, 1.41) | 1.19 (1.2, 1.2) | 242.8 | <0.0001 | |

| Code status clarified: % (n) | N= 49,067 | N= 16,994 | X2 | |

| 54.4 (26,707) | 35.9 (6,106) | 1728.0 | <0.0001 | |

| AD completed during PC consult: % (n) | N= 49,711 | N= 17,268 | ||

| 3.6 (1,777) | 2.2 (376) | 80.4 | <0.0001 | |

| POLST completed during PC consult: % (n) | N= 49,711 | N= 17,268 | ||

| 14.5 (7,212) | 6.3 (1,092) | 790.4 | <0.0001 | |

| In-hospital death: % (n) | N= 51,208 | N= 18,374 | ||

| 21.6 (11,074) | 24.9 (4,569) | 81.5 | <0.0001 | |

| Discharge location**: % (n) | ||||

| Home | N= 39,520 | N= 13,505 | ||

| Long-term acute care hospital | 44.4 (17,549) | 55.5 (7,491) | 645.9 | <0.0001 |

| Extended care facility | 3.2 (1,248) | 2.1 (2,167) | ||

| Hospital inpatient (PC team signed-off prior to hospital discharge) | 24.5 (9,684) | 16.0 (2,167) | ||

| Other | 13.8 (5,460) | 14.1 (1903) | ||

| Services arranged at discharge**: % (n) | N= 35,127 | N= 11,786 | 33.1 | <0.0001 |

| Hospice | 37.8 (13,262) | 34.8 (4,101) | ||

| N= 35,089 | N= 11,764 | 674.3 | <0.0001 | |

| Clinic-based PC | 3.1 (1,087) | 8.9 (1,048) | ||

| N= 35,084 | N= 11,762 | 13.7 | <0.0001 | |

| Home-based PC | 4.6 (1,608) | 3.8 (444) | ||

| N= 35,099 | N= 11,775 | 31.7 | <0.0001 | |

| Home healthcare | 15.4 (5,389) | 17.5 (2,066) | ||

| N= 35,089 | N= 11,774 | 21.2 | <0.0001 | |

| Other | 7.1 (2,505) | 5.9 (695) | ||

| N= 35,137 | N= 11,789 | 27.7 | <0.0001 | |

| No services | 34.8 (12,224) | 32.1 (3,788) |

Patients in ACP/GOC group may have additional reasons for PC consult identified by the referring team.

Among patients discharged from the hospital alive

Discussion

Palliative care teams at 78 diverse United States hospitals prospectively collected data that describes the ACP and GOC discussions that occur during inpatient PC consultations. These findings highlight strengths and gaps in care that can be used by PC clinicians for benchmarking and quality improvement. They also enable non-PC clinicians and healthcare administrators understand the value of PC and identify issues amenable to system-level solutions.

Assistance with ACP and GOC discussions was requested in nearly three-quarters of PC consultations overall and was the most common reason for PC consultation. Older and sicker patients were more likely to be referred for ACP or GOC. Palliative care teams engaged in care planning with the majority of patients they saw, frequently clarifying both surrogate decision maker and code status. In nearly one-third of patients, PC teams identified a preference to limit life-sustaining interventions (e.g. code status of DNR/DNI) that had not been previously documented. A change in code status was common even among patients who had previously completed an AD or POLST form, illustrating the importance of continuing care planning conversations over time as clinical context and patients’ priorities change. These conversations are critical work that can promote care that is consistent with patients’ values while improving resource utilization by helping patients avoid unwanted interventions at the end of life.

Over half of the patients who were referred to PC for reasons other than ACP/GOC were also found to have a need for care planning when seen by the PC team. This finding highlights the dynamic nature of patients’ needs and the different information yielded by PC assessments compared to those of primary teams. Further, even patients who had engaged in prior ACP, as evidenced by an AD or POLST on the chart at the time of referral to PC, frequently had a need for further care planning when evaluated by the PC team, demonstrating the need for planning to occur in a longitudinal and iterative fashion with reconsideration when clinical status changes. Care planning is not complete simply because a form has been signed.

The large number of additional issues - including pain and other symptoms as well as psychosocial and spiritual needs - that were identified in patients referred for ACP or GOC shows the complexity of seriously ill patients. Palliative care teams intervened on the majority of these issues, regardless of the reason for PC referral, which highlights the importance of the interdisciplinary composition of PC teams and comprehensive screening for PC needs during each consultation. The reason for referral to PC is not sufficient information to limit the scope of a consult.

There remains substantial room for improvement, however. Despite the fact that PC teams commonly clarified preferences for surrogate decision maker and code status, few patients left the hospital with a completed AD or POLST form. It may not be reasonable to expect inpatient PC teams to complete ADs routinely given that the legal requirements of ADs in many states make them difficult to complete during short hospitalizations, ADs are within the purview of many other professionals, and ADs may not be impactful for all seriously ill inpatients.14 However, completion of POLST forms (and analogous documents depending on the state) for patients who wish to limit life-sustaining treatments is a reasonable expectation of PC teams and can have important clinical impact.15 We found substantial variation in rate of POLST completion across teams in the PCQN (0% – 50.7%), suggesting that better performance is achievable. In recognition of this quality gap, we are currently undertaking a multisite quality improvement project within the PCQN to increase POLST completion. Through direct observation and deeper qualitative analyses to understand the processes of care of high-performing teams, we are seeking identify strategies that can be adopted widely to improve care. We are tracking and reporting comparative data for all teams in the network to motivate change.

We would like to highlight several limitations of our study. It is important to note that all PCQN data is collected by PC clinicians in the course of usual patient care. This approach has the advantage that data is prospectively collected and directly reflects the work done by clinicians, rather than their documentation practices. However, because data are collected by busy clinicians, the PCQN dataset was kept concise in order for it to be feasible. We therefore do not have detailed information, for instance about patients’ comorbidities, clinical circumstances, and the specific ACP or GOC needs identified, which limits the granularity of our findings. We were also unable to fully characterize the care planning that occurred, including what percentage were ACP versus GOC conversations. The PCQN strove to include data elements that are unambiguous whenever possible (e.g. code status, whether a POLST form was completed) and developed a data dictionary to define and standardize each data element (e.g. an ACP/GOC “intervention” is defined as a concerted effort to address an ACP/GOC need, which doesn’t necessarily lead to resolution of the need), but still it is difficult to ensure that the data elements were interpreted identically by all clinicians who collected data. The PCQN dataset does not include any information about patients’ or families’ opinions of their needs or the care they received, though this data is important and reflects future work for the PCQN. An important goal of care planning is for patients to receive care consistent with their values and preferences, but this concordance is challenging to measure and we are not currently able to report this outcome. We also do not collect information about the needs or clinical outcomes of patients who were not seen by PC consult teams. Finally, given the large sample size, we are aware that statistically significant results are not necessarily clinically meaningful; we tried to be careful to highlight only clinically meaningful findings.

In summary, our data show that ACP and GOC needs are prevalent in patients referred to PC and assistance with care planning is the most common reason for inpatient PC consultation. Palliative care clinicians frequently address care planning with patients and families, identify surrogate decision makers, and clarify care preferences to promote patient autonomy and reduce unwanted care. Care planning, though time consuming, does not result in longer hospital length of stay. However, the fact that few patients have their care preferences legally documented by the time of hospital discharge highlights a significant opportunity to improve care. Further direct observation and study of better performing teams is planned to identify best practices in care planning that can be disseminated across the PCQN and the field.

Key Points.

Question

What are the characteristics of patients referred to inpatient palliative care (PC) consult teams for advance care planning (ACP) or goals of care (GOC) discussions, what ACP/GOC needs are identified, which ACP/GOC activities occur, and what are the outcomes?

Findings

ACP/GOC was the most common reason for inpatient PC consultation and ACP/GOC needs were frequently identified even when the consultation request was for other reasons. During PC consultation, surrogates were identified and patients’ preferences regarding life-sustaining treatments were updated. However, only a minority of patients completed legal forms to document their preferences.

Meaning

Inpatient PC consultation meets a common and important need, but there remains opportunity for improvement.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the foundations that have generously supported the PCQN including the California HealthCare Foundation, the UniHealth Foundation, the Archstone Foundation, the Kettering Family Foundation, the James Irvine Foundation, and the Stupski Foundation. We would also like to thank the PCQN advisory board and particularly the members of the PCQN, who inspire us with their commitment to working together to understand and improve care for seriously ill patients and their families.

References

- 1.Sudore RL, Lum HD, You JJ, et al. Defining Advance Care Planning for Adults: A Consensus Definition From a Multidisciplinary Delphi Panel. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.12.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sinuff T, Dodek P, You JJ, et al. Improving End-of-Life Communication and Decision Making: The Development of a Conceptual Framework and Quality Indicators. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49(6):1070–1080. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sudore RL, Fried TR. Redefining the “planning” in advance care planning: preparing for end-of-life decision making. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(4):256–261. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-153-4-201008170-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernacki RE, Block SD, American College of Physicians High Value Care Task, F Communication about serious illness care goals: a review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA internal medicine. 2014;174(12):1994–2003. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leung JM, Udris EM, Uman J, Au DH. The effect of end-of-life discussions on perceived quality of care and health status among patients with COPD. Chest. 2012;142(1):128–133. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davison SN, Simpson C. Hope and advance care planning in patients with end stage renal disease: qualitative interview study. BMJ. 2006;333(7574):886. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38965.626250.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Houben CH, Spruit MA, Groenen MT, Wouters EF, Janssen DJ. Efficacy of advance care planning: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2014;15(7):477–489. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bischoff KE, Sudore R, Miao Y, Boscardin WJ, Smith AK. Advance care planning and the quality of end-of-life care in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(2):209–214. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care. 3rd. Pittsburg, PA: National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Myers J, Krueger P, Webster F, et al. Development and Validation of a Set of Palliative Medicine Entrustable Professional Activities: Findings from a Mixed Methods Study. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(8):682–690. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2014.0392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Joint Commission. Palliative Care Certification Manual 2014. Oakbrook Terrace, Illinois: Joint Commission Resources; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pantilat SZ, Marks AK, Bischoff KE, Bragg AR, O’Riordan DL. The Palliative Care Quality Network: Improving the Quality of Caring. J Palliat Med. 2017 doi: 10.1089/jpm.2016.0514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson F, Downing GM, Hill J, Casorso L, Lerch N. Palliative performance scale (PPS): a new tool. J Palliat Care. 1996;12(1):5–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fagerlin A, Schneider CE. Enough. The failure of the living will. Hastings Cent Rep. 2004;34(2):30–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hickman SE, Keevern E, Hammes BJ. Use of the physician orders for life-sustaining treatment program in the clinical setting: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(2):341–350. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]