Abstract

Background:

Anemia at discharge in patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is associated with poor prognosis; it is unknown whether this differs in women and men or whether there is a threshold value at which these relationships change.

Hypothesis:

Women have a lower discharge hemoglobin at which outcomes worsen.

Methods:

We identified patients with AMI in the TRIUMPH registry between 2005 and 2008. In multivariable models, we evaluated the relationship between discharge hemoglobin and 12-month mortality and tested whether this relationship varied by gender. We then assessed whether the relationships with discharge hemoglobin values was non-linear using a restricted cubic spline term.

Results:

Of the 4,243 patients with AMI, 32.9% were female. The mean admission hemoglobin was 12.9 ± 1.9 g/dL in women and 14.5 ± 2.0 g/dL in men with mean discharge hemoglobin 11.4 ± 1.8 g/dL and 12.9 ± 1.9 g/dL, respectively. Lower discharge hemoglobin was independently associated with increased mortality (p< 0.05). In multivariable models, discharge hemoglobin decline was similarly associated with increased 12-month mortality in women and men (per 1 g/dL decrease hemoglobin, women HR 1.24, 95% CI 1.09–1.42, p<0.01; and men HR 1.25 95% CI 1.13–1.37, p <0.01; p for gender interaction 0.99). The relationship between discharge hemoglobin and 12-month mortality was linear (P for non-linear spline term = 0.12).

Conclusion:

Lower discharge hemoglobin levels were similarly associated with increased 12-month mortality in women and men. These relationships are linear without a clear threshold suggesting any decline in discharge hemoglobin is associated with poor outcomes.

Keywords: anemia, acute myocardial infarction, outcomes, gender

Introduction

Anemia following acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is associated with worse outcomes.(1–6) Women have lower hemoglobin levels than men, yet definitions of anemia after AMI are not always gender-specific.(1, 7, 8) Whether discharge hemoglobin levels following AMI, a potentially modifiable risk factor, are different between women and men and whether these measures are similarly related to poor outcomes by gender is not well known.

Current anemia definitions and transfusions practices commonly rely upon threshold definitions of anemia which have been primarily derived from population hemoglobin norms.(9, 10) Studies in cardiac patients which have evaluated the relationship between different population-derived hemoglobin level thresholds for transfusion and outcomes have had variable results.(11) Therefore, it is important to determine whether the relationship between discharge hemoglobin and poor outcomes is, in fact, non-linear in order to determine if an outcome driven threshold for anemia exists.

Accordingly, we compared the relationship between discharge hemoglobin levels during AMI hospitalization and subsequent 1-year outcomes among patients in the 24-center, prospective Translational Research Investigating Underlying disparities in acute Myocardial infarction Patients Health status (TRIUMPH) registry. Our primary outcome of interest was 12-month mortality following AMI hospitalization. We assessed whether discharge hemoglobin was similarly predictive of poor outcomes in women and men and whether these relationships were non-linear, or suggestive of a threshold value at which the relationship with poor outcomes abruptly changes.

Methods

Data were obtained from the prospectively collected TRIUMPH study database, which includes 4,340 patients admitted with AMI enrolled between April 11, 2005 and December 31, 2008 at 24 institutions across the United States. The design and methods of the TRIUMPH study have been reported previously.(12) In brief, patients were >18 years of age, with confirmed elevated cardiac biomarkers (troponin or creatinine kinase MB within 24 hours of admission), and supporting evidence of AMI (electrocardiographic ST-segment changes or prolonged ischemic signs/symptoms). Trained data collectors performed baseline chart abstraction to document medical history, processes of inpatient care, laboratory results, and treatment. Research staff obtained socio-demographic and clinical data by conducting standardized interviews during hospitalization and at 1, 6, and 12-months after discharge. All participants signed an informed consent approved by participating facilities and Institutional Review Board Approval was obtained at each participating center.

Study population

All patients enrolled in TRIUMPH were eligible for inclusion. Patients were excluded if they had incomplete hemoglobin data or they died during hospitalization.

Predictor variables

The primary predictor variable for all analyses was discharge hemoglobin. Discharge hemoglobin was defined as the last hemoglobin value (g/dL) obtained within 48 hours of discharge from the hospital.(2)

Other covariates considered in the multivariable models included: patient demographics (age, race, gender), co-existing conditions abstracted from patient charts (diabetes, chronic kidney disease, hypertension, lung disease, acute renal failure, cerebrovascular event, gastrointestinal bleed upon admission (prior to any intervention), congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, history of myocardial infarction, current smoker, prior coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG) or in-hospital CABG, in-hospital bleeding events (TIMI major and minor bleeding events)(13), medications (anti-platelet agents, beta blocker, ace inhibitor, IIb/IIIa inhibitor, anti-coagulant, statin), Killip class, hospital site, type of infarction (NSTEMI, STEMI, and receipt of cardiac catheterization or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

For the in-hospital bleeding events, data abstracters systematically reviewed the charts to record bleeding episodes using the Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) classification.(13) TIMI major bleeding was defined as intracranial hemorrhage or a hemoglobin decline from admission to discharge ≥ 5 g/dl in the setting of overt bleeding. TIMI minor bleeding was assigned if the drop in hemoglobin was 3 to 5 g/dl in the setting of observed bleeding. Any bleeding episode with a decline in hemoglobin < 3 g/dl was classified as TIMI minimal bleeding.

Study Outcome

Our primary outcome of interest was 12-month mortality following the index AMI hospitalization. Mortality was confirmed using the Social Security Administration Death Master File.

Statistical Analysis

Patient characteristics, hemoglobin measures, and bleeding events during hospitalization were compared between women and men using chi square tests for categorical variables and Students T-test for continuous variables.

In our primary analysis, we used multivariable proportional hazard models to assess the association of discharge hemoglobin with time to death from any cause within 12 months. The hierarchial models were adjusted for patient demographics, clinical characteristics and clinical site. To test whether associations varied according to patient gender an interaction term between gender and discharge hemoglobin was included in the models. Next, in order to determine whether the relationships found in the primary analysis between discharge hemoglobin level and outcomes were non-linear, restricted cubic spline terms were added to the fully adjusted models.

To see if associations between discharge hemoglobin and outcomes differ in those who were transfused, in a sensitivity analysis, we ran our fully adjusted models among patients who received a blood transfusion.

All analyses were performed using the SAS statistical package version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and evaluated at a significance level of 0.05.

Results

Among 4,340 patients in the TRIUMPH registry, 97 (2.2%) were excluded; of these 73 (1.6%) for missing hemoglobin values and 24 (0.6%) for death during hospitalization, leaving 4,243 patients in the final study population.

Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Of the 4,243 patients in the study population 1,396 (32.9%) were female. The mean age of patients was 59.0 years ±12.3 and the majority of patients were white (67.2%). The majority of patients presented with Non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) (57.0%) with 92.1% undergoing cardiac angiography, 65.2% PCI, and 9.3% having in-hospital CABG. Women were less likely to present with ST elevation myocardial infarction (36.3% vs 46.3%, p <0.001), receive cardiac catheterization (90.0% vs 93.2%, P <0.001), or undergo PCI (58.5% vs 68.5%, p <0.001) compared to men during the hospitalization.

Table 1:

Baseline Characteristics Overall and by Gender

| Baseline Characteristics |

Overall n = 4,243 (%) |

Women n= 1,396 (%) |

Men n=2,847 (%) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age* | 59.0 ± 12.3 | 61.5 ± 13.1 | 57.8 ± 11.7 | < 0.01 |

| Race | < 0.01 | |||

| (1) Caucasian | 2,842 (67.1) | 817 (58.7) | 2025 (71.4) | |

| (2) African American | 1,101 (26.0) | 492 (35.3) | 609 (21.5) | |

| (3) Other | 287 (6.8) | 84 (6.0) | 203 (7.2) | |

| Diabetes | 1307 (30.8) | 541 (38.8) | 766 (26.9) | < 0.01 |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 367 (8.6) | 135 (9.7) | 232 (8.1) | 0.10 |

| Dyslipidemia | 2,076 (48.9) | 698 (50.0) | 1378 (48.4) | 0.33 |

| Hypertension | 2,831 (66.7) | 1047 (75.0) | 1784 (62.7) | < 0.01 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 196 (4.6) | 80 (5.7) | 116 (4.1) | 0.02 |

| Prior Myocardial Infarction | 890 (21.0) | 293 (21.0) | 597 (21.0) | 0.99 |

| Prior PCI | 183 (4.3) | 59 (4.2) | 124 (4.4) | 0.85 |

| Prior CABG | 481 (11.3) | 137 (9.8) | 344 (12.1) | 0.03 |

| Smoking | 2,531 (59.7) | 721 (51.6) | 1810 (63.6) | < 0.01 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 316 (7.4) | 109 (7.8) | 207 (7.3) | 0.53 |

| Prior Cerebrovascular Event | 211 (5.0) | 84 (6.0) | 127 (4.5) | 0.03 |

| Anemia at arrival | 32 (0.8) | 16 (1.1) | 16 (0.6) | 0.04 |

| Myocardial Infarction Diagnosis | < 0.01 | |||

| (1) STEMI | 1,825 (43.0) | 507 (36.3) | 1318 (46.3) | |

| (2) NSTEMI | 2,418 (57.0) | 889 (63.7) | 1529 (53.7) | |

| Killip Class | < 0.01 | |||

| (1) I | 3,730 (88.9) | 1186 (86.1) | 2544 (90.3) | |

| (2) II | 380 (9.1) | 157 (11.4) | 223 (7.9) | |

| (3) III | 60 (1.4) | 22 (1.6) | 38 (1.3) | |

| (4) IV | 25 (0.6) | 12 (0.9) | 13 (0.5) | |

| Acute Medications on Arrival | ||||

| Aspirin | 4075 (96.0) | 1325 (94.9) | 2750 (96.6) | 0.01 |

| Beta Blocker | 3,477 (81.9) | 1136 (81.4) | 2341 (82.2) | 0.40 |

| Fibrinolytic | 241 (5.7) | 54 (3.9) | 187 (6.6) | < 0.01 |

| Anti-platelet | 2,878 (67.8) | 880 (63.0) | 1998 (70.2) | < 0.01 |

| Anti-coagulant | 3,830 (90.3) | 1233 (88.3) | 2597 (91.2) | <0.01 |

| Anti-thrombin | 186 (4.4) | 66 (4.7) | 120 (4.2) | 0.44 |

| IIb/IIIa Inhibitor | 2,618 (61.7) | 786 (56.3) | 1832 (64.3) | < 0.01 |

| In Hospital Treatment | ||||

| PCI | 2,767 (65.2) | 817 (58.5) | 1950 (68.5) | < 0.01 |

| Cardiac Angiography | 3,909 (92.1) | 1256 (90.0) | 2653 (93.2) | < 0.01 |

| CABG | 395 (9.3) | 112 (8.0) | 283 (9.9) | 0.04 |

| Adverse Events | ||||

| Cardiogenic Shock | 119 (2.8) | 38 (2.7) | 81 (2.8) | 0.82 |

| Cerebrovascular Event | 23 (0.5) | 9 (0.6) | 14 (0.5) | 0.52 |

| Myocardial Infarction | 21 (0.5) | 5 (0.4) | 16 (0.6) | 0.37 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 51 (1.2) | 20 (1.4) | 31 (1.1) | 0.33 |

| GI bleed | 16 (0.4) | 3 (0.2) | 13 (0.5) | 0.23 |

All values expressed in percentage, except for age in years (mean +/− standard deviation)

CABG = coronary artery bypass surgery; GI= gastrointestinal; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention

Hemoglobin measurements and bleeding events during hospitalization are shown in Table 2. The mean admission hemoglobin was 14.0 g/dL ± 2.1. The mean discharge hemoglobin was 12.4g/dL ± 2.0. Women had lower admission (12.9 g/dL ± 1.9 vs 14.5 ± 2.0, p<0.001) and discharge hemoglobin levels (11.4 ± 1.8 vs 12.9 ± 1.9, p<0.001) compared with men. Bleeding events (TIMI major, minor, or minimal) occurred in 9.9% of patients and 11.1% of all patients received a blood transfusion during their initial AMI hospitalization. Women had similar rates of bleeding events (9.2% vs 10.2% p=0.31) compared to men, but were more likely to receive a blood transfusion during their initial AMI hospitalization (14.4% vs 9.6% p <0.001). (Table 2) Patients with a discharge hemoglobin ≥ 11g/dL were more likely than patients with lower discharge hemoglobin to be discharged on dual anti-platelet therapy (p <0.01).

Table 2:

Hemoglobin Characteristics and Bleeding Events Overall and by Gender

| Hemoglobin Characteristic | Gender | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall n= 4,243 | Women n= 1,396 | Men n= 2,847 | P value | |

| Admission Hemoglobin | 14.0 ± 2.1 | 12.9 ± 1.9 | 14.5 ± 2.0 | < 0.01 |

| Discharge Hemoglobin | 12.4 ± 2.0 | 11.4 ± 1.8 | 12.9 ± 1.9 | < 0.01 |

| Blood Transfusion | 473 (11.1) | 201 (14.4) | 272 (9.6) | < 0.01 |

| Bleeding event | 420 (9.9) | 129 (9.2) | 291 (10.2) | 0.32 |

| In-hospital bleeding | 0.55 | |||

| (0) None | 3,823 (90.1) | 1267 (90.0) | 2556 (89.0) | |

| (1) Minimal | 175 (4.1) | 54 (3.9) | 121 (4.3) | |

| (2) TIMI Minor | 149 (3.5) | 49 (3.5) | 100 (3.5) | |

| (3) TIMI Major | 94 (2.2) | 25 (1.8) | 69 (2.4) | |

Hemoglobin values in g/dL

Hemoglobin values expressed as mean ± standard deviation, categorical values expressed as number (%)

Abbreviation: TIMI= Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction Classification

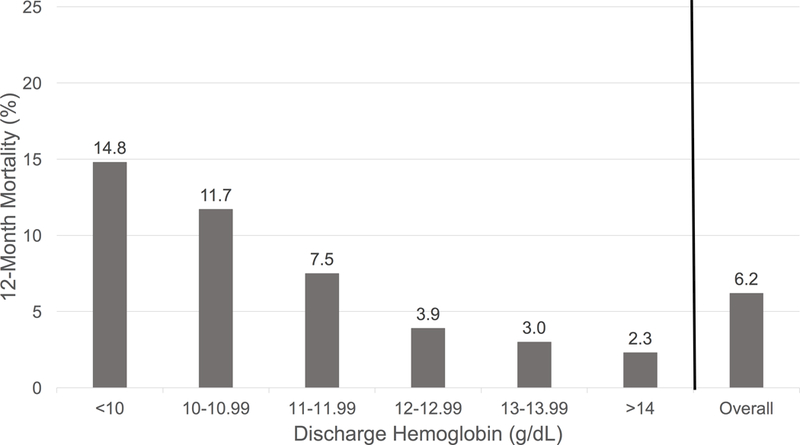

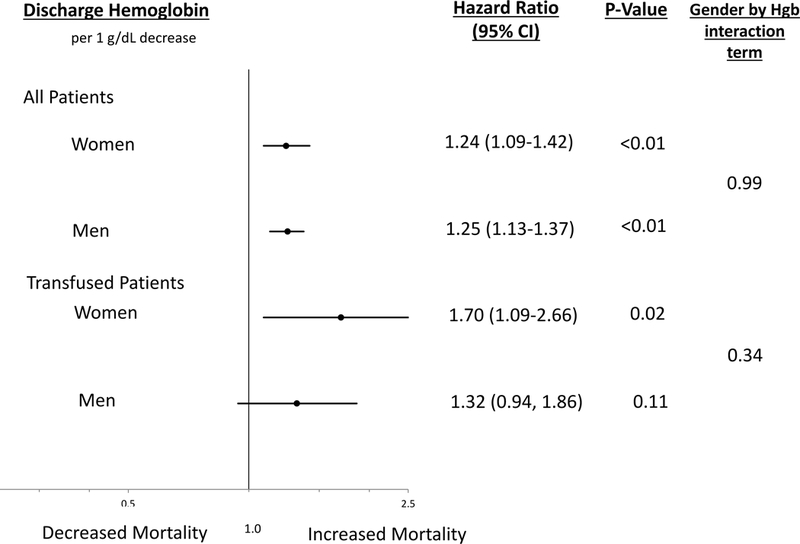

Among the 4,243 patients, 6.3% died within 12-months. (Figure 1) In unadjusted models, discharge hemoglobin was significantly associated with 12-month mortality (HR per 1g/dL decrease in discharge hemoglobin 1.41, 95% CI 1.32–1.51, p <0.01). In multivariable models adjusting for patient demographic and clinical characteristics, discharge hemoglobin remained significantly associated with 12-month mortality (HR per 1g/dL decrease in discharge hemoglobin 1.24, 95% CI 1.15–1.35, p <0.01). This relationship was similar in women and men (HR 1.24 per 1 g/dL decrease in discharge hemoglobin, 95% CI 1.09–1.42, p <0.01; and HR 1.25 CI 1.13–1.37, p<0.01; p=0.99 for gender by discharge hemoglobin interaction), respectively. (Figure 2)

Figure 1: Unadjusted 12-Month Mortality by Discharge Hemoglobin.

aIn final adjusted models, including restricted cubic spline terms p-value for non-linearity = 0.12

b74 (27.8%) had a hemoglobin ≤ 10 g/dL and 55.4% of these patients died of a cardiovascular cause. Cardiovascular death was the most common cause of death in patients with a discharge hemoglobin ≤ 10g/dl.

Figure 2: Adjusted Associations Between Discharge Hemoglobin with 12-Month Mortality in Women and Men.

aModels are adjusted for patient demographics (age, race,), co-existing conditions (diabetes, chronic kidney disease, hypertension, lung disease, renal failure, gastrointestinal bleed, history of heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, myocardial infarction, smoker, CABG), clinical characteristics (bleeding events, cardiac catheterization, percutaneous coronary intervention, CABG, killip class), and medication use (aspirin, anti-platelet, beta blocker, ace inhibitor, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, anti-coagulant, statin)

b 473 patients who had a blood transfusion were included in the sensitivity analysis.

CInteraction term is for gender*discharge hemoglobin

In analyses testing the nature of the relationship between discharge hemoglobin level and 12-month mortality, the association was linear (p= 0.12 for the non-linear spline term in the fully adjusted model) suggesting no clear inflection point, or threshold value of discharge hemoglobin where outcomes worsen.

In sensitivity analysis evaluating the subset of patients who received a transfusion, unadjusted models showed a significant association between discharge hemoglobin and 12-month mortality (per 1 g/dL decrease in discharge hemoglobin HR 1.30, 95% CI 1.04–1.62, p = 0.02). In multivariable models adjusting for patient demographic and clinical characteristics, discharge hemoglobin was similarly significantly associated with mortality in women and men (HR 1.70 per 1 g/dL decrease in discharge hemoglobin, 95% CI 1.09–2.66, p = 0.02; HR 1.32 95% CI 0.94–1.86, p = 0.11, respectively; p for gender by discharge hemoglobin interaction = 0.34. (Figure 2)

Discussion

In this population of patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction, discharge hemoglobin was associated with 12-month mortality. The relationship was similar in women and men. Importantly, the relationship between discharge hemoglobin and mortality was linear, or continuous, suggesting no clear threshold hemoglobin value at which the association with mortality abruptly changes in women or men.

Our study adds to the evidence of the importance of anemia during AMI hospitalization in several ways. First, our study confirms prior studies suggesting that lower discharge hemoglobin is associated with worse outcomes.(5, 14) Patients with lower discharge hemoglobin levels were less likely to be discharged on dual anti platelet therapy which likely contributes to higher mortality. Discharge hemoglobin is an ideal marker for prognosis as it is routinely measured in patients hospitalized with AMI and it is potentially modifiable. Notably, most patients in our cohort (84.6%) had some decline in their hemoglobin during AMI admission. Further, bleeding events following AMI are associated with poor outcomes.(15–17) Therefore, future research is needed to determine if efforts to improve discharge hemoglobin levels, such as, strategies to predict and minimize bleeding, will improve outcomes for all patients after AMI.

Second, our study enhances previous literature in its assessment of whether gender differences exist in the association between discharge hemoglobin and outcomes. Women are known to have higher rates of anemia associated with AMI, higher risk of bleeding with ACS, and an overall worse prognosis after AMI (1, 18–21). Similar to differences noted in prior studies, women were less likely to receive guideline indicated medications on arrival, particularly anti-platelet agents (aspirin 94.9% vs 96.6%, anti-platelet agents 63.0% vs 70.2%, anti-coagulants 88.3% vs 91.2%, and IIb/IIIa inhibitors 56.3% vs 64.3% in women and men respectively, all p <0.01) or undergo invasive procedures such as angiography, PCI, or CABG all factors which lower discharge hemoglobin(22, 23). Yet, to our knowledge, our study is the first to demonstrate that a lower hemoglobin value at discharge is equally associated with poor outcomes in women and men. Therefore, our findings support using discharge hemoglobin as a marker for poor prognosis in all patients after AMI.

Finally, our study is unique in that we tested whether the relationships between discharge hemoglobin and mortality was non-linear, or suggestive of a threshold value at which the association abruptly changes. Our tests for non-linearity were non-significant supporting a continuous relationship between decreasing levels of discharge hemoglobin with poor outcomes. Therefore, our study suggests that any fall in hemoglobin is associated with worse outcomes and challenges the clinical paradigm of using specific hemoglobin thresholds to define anemia of prognostic importance. Our study also suggests that hemoglobin thresholds may be triggering differences in interventions such as transfusion. For example, despite equal rates of bleeding events, women had nearly twice the rate of blood transfusions compared with men. We hypothesize this difference may be due to a higher likelihood of women presenting with lower hemoglobin levels or more frequently reaching a hemoglobin level below a clinical threshold value prompting transfusion. Given the uncertainty as to whether transfusions in AMI patients are beneficial, further studies are needed to understand whether efforts to increase discharge hemoglobin levels in AMI patients, including transfusion, improve long-term mortality.(2, 24, 25)

Several limitations should be considered when evaluating the findings of this study. First, although we controlled for many variables related to sources of potential blood loss including bleeding events and revascularization procedures, other sources of unmeasured hemoglobin decline likely exist which could affect discharge hemoglobin. Second, we were unable to assess the lowest hemoglobin value during admission as the registry only captures admission and discharge levels. However, discharge hemoglobin is routinely captured, reflects the level after interventions to optimize outcomes have been rendered, and has been shown to be a valuable prognostic marker. Finally, we only examined the relationship between discharge hemoglobin and mortality. Future studies examining the relationship with hemoglobin levels after discharge are needed to compare whether longitudinal trends in hemoglobin are similarly associated with outcomes.

In summary, following AMI, lower discharge hemoglobin levels, a potentially modifiable variable, were associated with increased 12-month mortality. Importantly, these relationships are similar in women and men. The relationship between discharge hemoglobin and mortality is continuous or linear, suggesting no threshold value where outcomes worsen. Future studies are needed to determine whether efforts to increase discharge hemoglobin levels improve outcomes for patients after AMI.

Acknowledgements/Funding Source

The TRIUMPH Registry was funded by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) (P50 HL077113). This analysis was funded in part by CV Outcomes, Inc., Kansas City, MO. Dr. Daugherty is supported by Award Number R01 HL133343 from the NHLBI. The views expressed in this manuscript represent those of the author(s), and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NHLBI.

Acknowledgements/Funding Source: The TRIUMPH Registry was funded by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) (P50 HL077113). This analysis was funded in part by CV Outcomes, Inc., Kansas City, MO. Dr. Daugherty is supported by Award Number R01 HL133343 from the NHLBI.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None

References

- 1.Nikolsky E, Mehran R, Aymong ED, Mintz GS, Lansky AJ , et al. : Impact of anemia on outcomes of patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions. The American Journal of Cardiology. 2004;94(8):1023–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salisbury AC, Alexander KP, Reid KJ, Masoudi FA, Rathore SS , et al. : Incidence, correlates, and outcomes of acute, hospital-acquired anemia in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3(4):337–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKechnie RS, Smith D, Montoye C, Kline-Rogers E, O’Donnell MJ , et al. : Prognostic implication of anemia on in-hospital outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. 2004;110(3):271–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsujita K, Nikolsky E, Lansky AJ, Dangas G, Fahy M , et al. : Impact of anemia on clinical outcomes of patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in relation to gender and adjunctive antithrombotic therapy (from the HORIZONS-AMI trial). Am J Cardiol. 2010;105(10):1385–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vaglio J, Safley DM, Rahman M, Kosiborod M, Jones P , et al. : Relation of anemia at discharge to survival after acute coronary syndromes. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96(4):496–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bassand J-P, Afzal R, Eikelboom J, Wallentin L, Peters R , et al. : Relationship between baseline haemoglobin and major bleeding complications in acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(1):50–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beutler E, Waalen J: The definition of anemia: what is the lower limit of normal of the blood hemoglobin concentration? Blood. 2006;107(5):1747–1750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blanc BFC, Hallberg L, et al. : Nutritional anaemias. Report of a WHO Scientific Group. WHO Tech Rep Ser. 1968;405:1–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carson JL, Carless PA, Hébert PC: OUtcomes using lower vs higher hemoglobin thresholds for red blood cell transfusion. JAMA. 2013;309(1):83–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klein HG, Flegel WA, Natanson C: Red blood cell transfusion: Precision vs imprecision medicine. JAMA. 2015:1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murphy GJ, Pike K, Rogers CA, Wordsworth S, Stokes EA , et al. : Liberal or Restrictive Transfusion after Cardiac Surgery. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(11):997–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arnold SV, Chan PS, Jones PG, Decker C, Buchanan DM , et al. : Translational Research Investigating Underlying Disparities in Acute Myocardial Infarction Patients’ Health Status (TRIUMPH): design and rationale of a prospective multicenter registry. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4(4):467–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chesebro JH, Knatterud G, Roberts R, Borer J, Cohen LS , et al. : Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) Trial, Phase I: A comparison between intravenous tissue plasminogen activator and intravenous streptokinase. Clinical findings through hospital discharge. Circulation. 1987;76(1):142–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aronson D, Suleiman M, Agmon Y, Suleiman A, Blich M , et al. : Changes in haemoglobin levels during hospital course and long-term outcome after acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2007;28(11):1289–1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ndrepepa G, Berger PB, Mehilli J, Seyfarth M, Neumann FJ , et al. : Periprocedural bleeding and 1-year outcome after percutaneous coronary interventions - Appropriateness of including bleeding as a component of a quadruple end point. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(7):690–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindsey JB, Marso SP, Pencina M, Stolker JM, Kennedy KF , et al. : Prognostic Impact of Periprocedural Bleeding and Myocardial Infarction After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Unselected Patients Results From the EVENT (Evaluation of Drug-Eluting Stents and Ischemic Events) Registry. JACC-Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2(11):1074–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eikelboom JW, Mehta SR, Anand SS, Xie CC, Fox KAA, Yusuf S: Adverse impact of bleeding on prognosis in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2006;114(8):774–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moscucci M, Fox KA, Cannon CP, Klein W, Lopez-Sendon J , et al. : Predictors of major bleeding in acute coronary syndromes: the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE). Eur Heart J. 2003;24(20):1815–1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiu JH, Bhatt DL, Ziada KM, Chew DP, Whitlow PL , et al. : Impact of female sex on outcome after percutaneous coronary intervention. Am Heart J. 2004;148(6):998–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reynolds HR, Farkouh ME, Lincoff AM, Hsu A, Swahn E , et al. : Impact of female sex on death and bleeding after fibrinolytic treatment of myocardial infarction in GUSTO V. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(19):2054–2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huynh T, Piazza N, DiBattiste PM, Snapinn SM, Wan Y , et al. : Analysis of bleeding complications associated with glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptors blockade in patients with high-risk acute coronary syndromes: insights from the PRISM-PLUS study. Int J Cardiol. 2005;100(1):73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blomkalns AL, Chen AY, Hochman JS, Peterson ED, Trynosky K , et al. : Gender disparities in the diagnosis and treatment of non–ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: Large-scale observations from the CRUSADE (Can Rapid Risk Stratification of Unstable Angina Patients Suppress Adverse Outcomes With Early Implementation of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guidelines) National Quality Improvement Initiative. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(6):832–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jneid H, Fonarow GC, Cannon CP, Hernandez AF, Palacios IF , et al. : Sex differences in medical care and early death after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2008;118(25):2803–2810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chatterjee S WJSALEMD: Association of blood transfusion wih increased mortality in mycardial infarction: A meta-analysis and diversity-adjusted study. Arch Intern Med. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salisbury AC, Reid KJ, Marso SP, Amin AP, Alexander KP , et al. : Blood Transfusion During Acute Myocardial InfarctionAssociation With Mortality and Variability Across Hospitals. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(8):811–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]