Abstract

Neurodegenerative illnesses such as Parkinson and Alzheimer disease are an increasingly prevalent problem in aging societies, yet no therapies exist that retard or prevent neurodegeneration. Dominant missense mutations in leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) are the most common genetic cause of Parkinson disease (PD), but the mechanisms by which mutant forms of LRRK2 disrupt neuronal function and cause cell death remain poorly understood. We report that LRRK2 interacts with the death adaptor protein FADD, and that in primary neuronal culture LRRK2-mediated neurodegeneration is prevented by the functional inhibition of FADD or depletion of caspase-8, two key elements of the extrinsic cell death pathway. This pathway is activated by disease-triggering mutations, which enhance the LRRK2-FADD association and the consequent recruitment and activation of caspase-8. These results establish a direct molecular link between a mutant PD gene and the activation of programmed cell death signaling, and suggest that FADD/caspase-8 signaling contributes to LRRK2-induced neuronal death.

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, Apoptosis, Neuronal apoptosis, neuronal death, Neuron Death, caspase

Introduction

Parkinson disease (PD) is characterized by motor and cognitive dysfunction reflecting widespread neurodegeneration, particularly of midbrain dopaminergic neurons. PD most commonly presents as a sporadic illness, but over the past decade insights into the molecular mechanisms of PD-related neurodegeneration have emerged from the discovery of mutations underlying rare inherited forms of the disease (Cookson et al., 2005). Despite these advances, the key signaling events that cause neurodegeneration in PD remain poorly defined.

One set of signaling pathways that can elicit cell death in response to cellular insults such as an accumulation of misfolded proteins, or oxidative stress (both of which have been implicated in PD), are those of programmed cell death. The core of these pathways is composed of proteolytic caspases that, when activated, lead to a highly regulated process of cell death. Two broadly defined pathways can trigger programmed cell death: the intrinsic pathway, which is controlled by factors that are released by mitochondria and activate caspase-9, and the extrinsic pathway, which is typically initiated by cell surface “death receptors” such as TNF-R and Fas that lead to caspase-8 activation via the death adaptor protein FADD. While most studies have addressed the potential involvement of the intrinsic pathway in PD-related neurodegeneration, activated caspase-8 has been observed in postmortem PD brain tissue (Hartmann et al., 2001b), and modulation of the extrinsic pathway can reduce dopamine neuron loss in the MPTP mouse model of PD (Dauer and Przedborski, 2003; Hayley et al., 2004; McCoy et al., 2006). Moreover, extrinsic pathway signals are crucial mediators of inflammation, which is also postulated to mediate neurotoxicity in PD (Hirsch et al., 2005).

Dominantly-inherited missense mutations in leucine-rich-repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) are the most common genetic cause of PD, causing a clinical syndrome that is clinically and pathologically indistinguishable from sporadic PD. LRRK2 contains both GTPase and kinase signaling domains, as well as LRR and WD40 protein-protein interaction domains (Fig 1A). Many potentially pathogenic sequence alterations have been identified in LRRK2 (Goldwurm et al., 2005), but five missense mutations (Figure 1A) clearly segregate with PD in large family studies (Bonifati, 2007). Two of these mutations (R1441G, R1441C) are located in the GTPase domain (termed Ras of complex proteins, or “Roc” domain), a third (Y1699C) falls in a region between the GTPase and kinase domains (termed the C-terminal of Roc, or “COR” domain), and two other mutations (G2019S and I2020T) are in the kinase domain (Figure 1A). While these mutations may affect LRRK2 GTPase (Guo et al., 2007; Lewis et al., 2007; Li et al., 2007) and kinase (West et al., 2005; Greggio et al., 2006; Smith et al., 2006; West et al., 2007) activity, published studies differ as to whether other mutations in LRRK2 significantly alter its kinase function (West et al., 2005; Gloeckner et al., 2006; Greggio et al., 2006; MacLeod et al., 2006; Smith et al., 2006; West et al., 2007). LRRK2 induces apoptotic neuronal death (Iaccarino et al., 2007) that requires intact kinase function (Greggio et al., 2006; Smith et al., 2006), but physiologically relevant LRRK2 substrates or downstream effectors have yet to be identified.

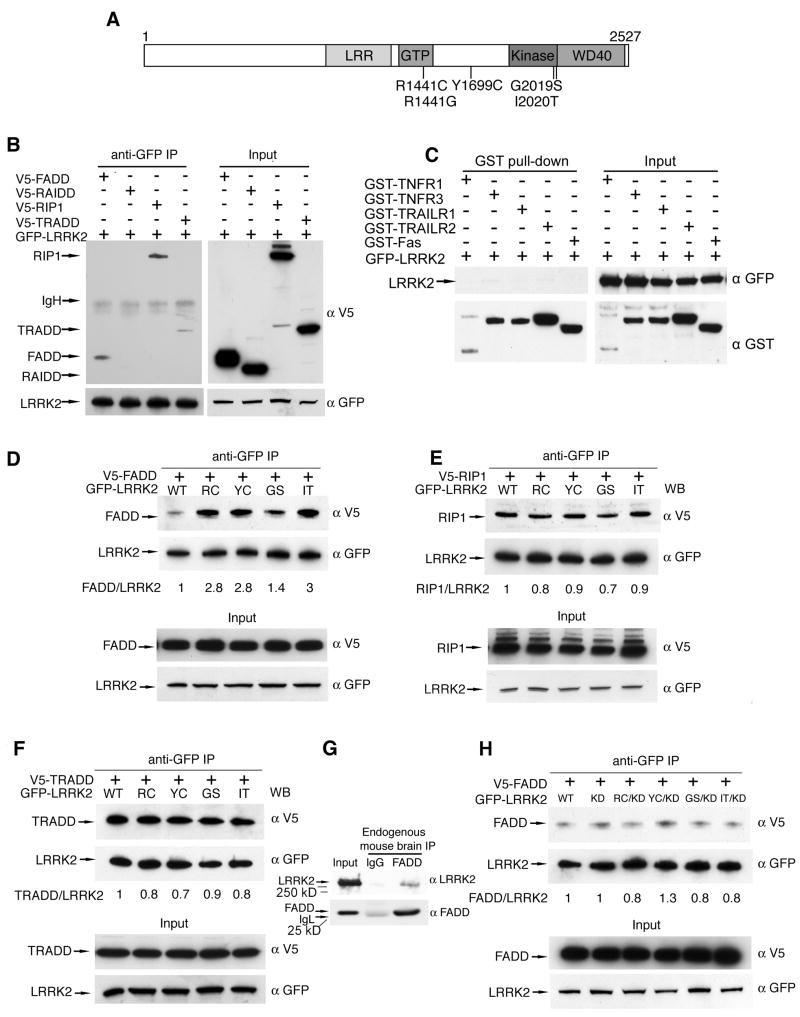

Figure 1. Parkinson disease mutations enhance the interaction between LRRK2 and FADD.

(A) Domain structure and Parkinson disease mutations of LRRK2. LRR = leucine-rich repeat; Roc = Ras of complex GTPase; COR = C-terminal of Roc. Five dominantly inherited PD-causing missense mutations are indicated.

(B) LRRK2 interacts with death adaptor proteins of the extrinsic pathway. 293T cells co-expressing GFP-LRRK2 and V5-tagged death adaptor proteins were subjected to anti-GFP immunoprecipitation followed by anti-GFP and anti-V5 immunoblotting

(C) LRRK2 does not associate with death receptors. 293T cells co-expressing GFP-LRRK2 with GST-tagged cytoplasmic domains of death receptors were subjected to GST pull-down followed by immunoblotting.

(D)Enhanced association of FADD with LRRK2 PD mutants. 293T cells were co-transfected with WT or PD mutant GFP-LRRK2 and V5-tagged FADD. Anti-GFP immunoprecipitates were analyzed by anti-V5 and anti-GFP immunoblots. Ratios indicate binding of FADD to LRRK2 relative to WT-LRRK2.

(E) PD mutations fail to enhance association of LRRK2 with RIP1. 293T cells were co-transfected with V5-tagged RIP1 and WT or PD mutant GFP-LRRK2 and assessed as in (D).

(F) PD mutations fail to enhance association of LRRK2 with TRADD. 293T cells were co-transfected with V5-tagged TRADD and WT or PD mutant GFP-LRRK2 and assessed as in (D).

(G)Endogenous LRRK2-FADD complex formation in mouse brain. Whole brain lysates from one-year old wild type mice were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-FADD (clone 7A2). Co-purified LRRK2 was determined with anti-LRRK2 immunoblotting.

(H)Blocking LRRK2 kinase function prevents the enhanced FADD association with LRRK2 disease mutants. 293T cells expressing V5-tagged FADD and GFP-tagged WT or kinase dead (KD) LRRK2 were immunoprecipitated and immunoblotted as in (D).

We demonstrate in vitro that LRRK2 interacts with the death adaptor protein FADD, and that this interaction recruits and activates caspase-8-dependent neuronal death. Moreover, the potential role of the extrinsic cell death pathway in PD is supported by findings in postmortem brain tissue of patients with LRRK2-associated Parkinson disease.

Materials and Methods

Cloning of Human LRRK2 cDNA

A human LRRK2 cDNA was amplified and fully sequenced from HEK cell cDNA and the translated amino acid sequence conformed to human LRRK2 AAI17181 in the NCBI database. All subsequent mutations were generated using site-directed mutagenesis and all mutant clones were resequenced to confirm their accuracy.

Plasmids

LRRK2 cDNA from HEK 293 cells was cloned in pcDNA-DEST53 (Invitrogen). Cytoplasmic domains of TNFR1, TNFR3, TRAIL-R1, TRAIL-R2 and Fas were cloned in pcDNA27, whereas FADD, TRADD, RIP1 and RAIDD cDNA were cloned in pcDNA3.1/nV5-DEST (Invitrogen). All subsequent mutants were generated using site directed mutagenesis and all mutant clones were re-sequenced to confirm their accuracy.

Cell Lines and Primary Neuronal Cultures

CAD cells were grown in DMEM/F12 (GIBCO) supplemented with 8% fetal bovine serum. 293T cells were grown in DMEM (GIBCO) with 10% serum. CAD cells were transfected with Lipofectamine/PLUS, whereas 293T cells were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 or Lipofectamine LTX (Invitrogen). Cultures of cortical neurons from E16 mice were maintained in Neurobasal medium containing B-27 supplements (GIBCO), and transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 four days after being plated. Primary neurons were transfected with LRRK2 expression constructs and pCMS-EGFP (Clontech) at 10:1 ratio. In co-transfection experiments, LRRK2 and FADD-DD or LZ-FADD-DD expression constructs were used at a ratio 2:1. Each experiment was performed on coverslips in triplicate, at least three times, and > 100 cells/coverslip were quantified. Apoptotic neurons were defined as cells having two or more condensed apoptotic nuclear bodies visualized using DAPI.

Antibodies

Mouse anti-GST clone GST-2 and anti-FLAG M2 were purchased from Sigma. Mouse anti-GFP was from Roche. Rabbit anti-GFP was from Abcam. Mouse anti-V5 was from Invitrogen. Mouse anti-FADD was from BD Transduction. Rat anti-FADD clone 7A2 was a gift from A. Strasser. Rabbit anti-mouse LRRK2 was a gift from Z. Yue (Li et al, 2007). Mouse anti-HA clone F-7 and rabbit anti-caspase-1 were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Mouse anti-caspase-8 clone 1C12 and rabbit anti-human caspase-9 were from Cell Signaling Technology. Mouse anti-caspase-8 clone C15 was from Alexis. Rabbit anti-caspase-8 and rabbit anti-caspase-9 were from MBL.

Immunofluorescent labeling

48 h after transfection, formaldehyde-fixed neurons on coverslips were blocked in PBS containing 0.25% Triton X-100 and 5% normal donkey serum for 30 min. Coverslips were then incubated overnight at 4°C in rabbit anti-GFP antibodies diluted in block solution. The next day coverslips were washed, incubated with FITC-conjugated secondary antibodies, and washed in PBS before mounting using Vectashield Mounting Media with DAPI (Vector Laboratories). Immunostained neurons were then subjected to quantification for apoptosis.

GST-pulldown and Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) Analysis

293T cells transfected with various expression constructs were Dounce homogenized in lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1–0.5% NP-40, 2 mM EGTA, 2 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 10 mM NaF, 25 mM β-glycerophosphate, pH 7.2, and protease inhibitors). After centrifugation and preclearing, lysates were incubated with glutathione affinity gel (Sigma) or rabbit anti-GFP antibody with protein-A agarose for 3 h to overnight. The immunocomplexes were washed five times with isotonic or hypertonic lysis buffer (250 mM NaCl) and released from beads by boiling in 1X Laemmli sample buffer for immunoblot analysis.

RNA interference (RNAi)

Penetratin1 (Pen1)-coupled siRNA were generated as described previously (Davidson et al., 2004). The target sequences used were as follows: caspase-8 GCACAGAGAGAAGAAUGAG; caspase-9 GGCACCCUGG-CUUCACUCU. Three days after plating, primary neurons were treated with 350 nM Pen1-siRNA for 24 h. Cells were transfected and 48 h later, assessed for apoptotic death as described above.

Results

The kinase domain of LRRK2 is most closely related to that of LRRK1, followed by the receptor interacting protein (RIP) family of serine/threonine kinases (Manning et al., 2002), crucial regulators of cell survival and death (Meylan and Tschopp, 2005; Festjens et al., 2007). RIP1, the best studied member of this family, transduces signals downstream of death receptors (e.g., TNFα, Fas ligand, TRAIL) of the extrinsic cell death pathway. This led us to explore whether LRRK2 might also participate in extrinsic cell death signaling.

We first assessed whether, like RIP1, LRRK2 can interact with death adaptor proteins of the extrinsic cell death pathway. Co-IP experiments demonstrated that LRRK2 interacts with FADD and TRADD, two key death adaptor proteins. FADD, TRADD and RIP1 all contain death domains (DD), and LRRK2 also co-purified with RIP1. However, LRRK2 did not bind the DD-containing protein RAIDD that is not implicated in extrinsic apoptotic signaling (Figure 1B), nor did it bind any of the DD-containing death receptors (TNF-R1, TNF-R3, Fas, TRAIL-R1, TRAIL-R2; Figure 1C). These data suggest that LRRK2 specifically interacts with a subset of DD-containing proteins that transduce extrinsic cell death signals.

To explore the potential disease relevance of these LRRK2-interacting proteins, we next tested whether their interaction with LRRK2 was altered by PD-linked mutations. We found that all mutations tested enhanced the interaction between LRRK2 and FADD (Figure 1C). In contrast, PD mutations had no effect on the association of LRRK2 with RIP1 or TRADD (Figure 1D & E). These findings led us to determine whether these proteins interact in brain tissue, and LRRK2 did co-purify with FADD in mouse brain lysates (Figure 1F). Blocking LRRK2 kinase function prevents the death of primary neurons transfected with PD mutant forms of LRRK2 (Greggio et al., 2006; Smith et al., 2006; data not shown), so we next explored whether blocking kinase function also alters FADD binding. Indeed, the kinase-deficient LRRK2 mutation (K1906R) normalized the enhanced FADD binding by caused by PD mutations (Figure 1G), consistent with a potential role for this death adaptor protein in LRRK2 neurotoxicity. These data led us to hypothesize that FADD may be recruited to LRRK2, leading to the formation of a complex similar to the death inducing signaling complex (DISC) formed by Fas, FADD and other signaling proteins.

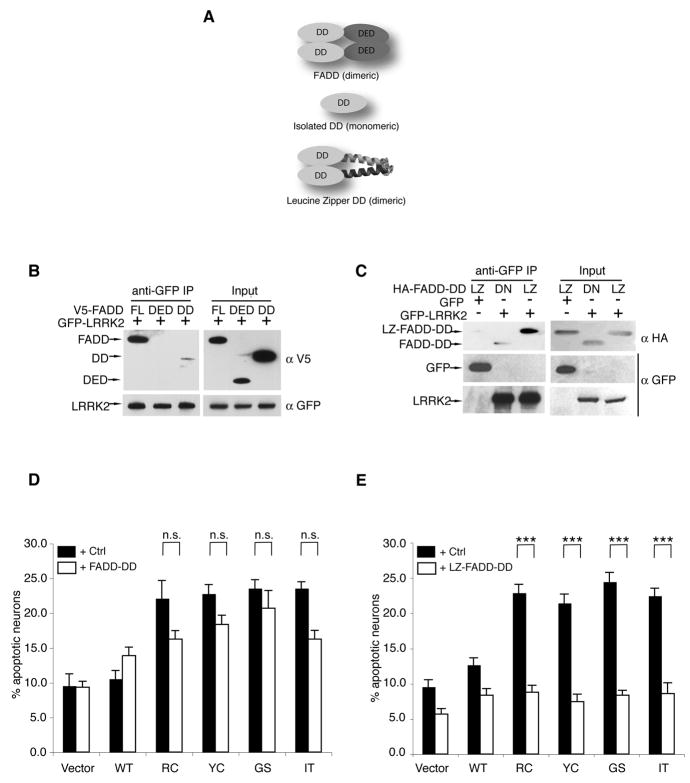

To further explore this notion, we characterized the interaction between LRRK2 and FADD. FADD transduces death signals by binding to ligand-activated Fas via its DD and recruiting and activating caspase-8 via its death-effector domain (DED; Figure 2A). FADD dimerizes upon binding to Fas, a crucial event that greatly enhances both the FADD-Fas interaction and caspase-8 activation. Similarly, in co-IP studies we found that FADD binds to LRRK2 via its DD, yet the interaction was weak, despite the high expression level of this isolated domain (Figure 2B). Mimicking the dimeric conformation of physiologically active FADD-DD by attaching a leucine-zipper domain (LZ; LZ-FADD-DD) restored its interaction with LRRK2 (Figure 2C). LZ-FADD-DD and the isolated FADD-DD are dominant negative inhibitors of FADD signaling because they lack the DED necessary to recruit caspase-8. Thus, we used these molecules to ask whether blocking FADD function affects LRRK2-induced neuronal death. The monomeric FADD-DD failed to significantly suppress the neuronal death caused by LRRK2 PD mutants, although there was a trend for death suppression (Figure 2D). In contrast, dimeric LZ-FADD-DD completely blocked LRRK2-mediated neurodegeneration (Figure 2E). Thus, the strength of FADD-LRRK2 interaction (Figure 2B & C) correlates with the ability of the dominant negative FADD mutant to block LRRK2-induced cell death (2D & E), further supporting a functional relationship between these proteins.

Figure 2. LRRK2-induced neuronal death requires FADD.

(A) A schematic depicts the domain structure of FADD, the isolated death domain (FADD-DD) and the leucine-zipper-DD (LZ-FADD-DD) in which the death domain is dimerized through the addition of a leucine zipper.

(B) FADD interacts with LRRK2 via its DD. GFP-LRRK2 was co-expressed with V5-tagged full-length FADD, FADD-DED, or FADD-DD in 293T cells and immunoprecipitated with anti-GFP. Co-purified FADD or FADD domains were detected by anti-V5 immunoblotting.

(C)LRRK2-FADD interaction is enhanced by dimerization of FADD-DD. The interaction between GFP-LRRK2 and monomeric (DD) or dimeric (LZ) FADD-DD was assessed by anti-HA following immunoprecipitation with anti-GFP in 293T cells.

(D)FADD-DD is a poor inhibitor of LRRK2 neurotoxicity. Mouse cortical neurons were transfected with LRRK2+lacZ (Ctrl) or LRRK2+FADD-DD. A GFP reporter was co-transfected in each case. Transfected neurons displaying apoptotic nuclear morphology were counted 48h following transfection using DAPI. Data are mean ± SEM from three individual experiments of triplicate coverslips (ns: non-significant, ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test).

(E) Dimeric FADD-DD effectively blocks LRRK2 neurotoxicity. Mouse cortical neurons expressing LRRK+lacZ (Ctrl) or LRRK2+LZ-FADD-DD were assessed as in (D) (*** p<0.001).

These data suggest that the LRRK2-FADD interaction may serve to recruit and activate caspase-8. In the absence of exogenous FADD, only a trace amount of caspase-8 co-purified with LRRK2 (Figure 3A). The expression of exogenous FADD significantly increased the amount of caspase-8 that co-purified with LRRK2, suggesting that LRRK2, FADD, and caspase-8 are components of a multiprotein complex (Figure 3A). To evaluate the function of caspase-8 in transducing the LRRK2-induced death signal, we reduced endogenous caspase-8 levels in neurons by RNA interference (RNAi). The efficiency and the specificity of this caspase-8 siRNA have been previously established in primary neuronal cultures (Davidson et al., 2004) and is effective against Fas-mediated neuronal death (Carol Troy, personal communication). Knocking down caspase-8 significantly reduced LRRK2-induced neurodegeneration (Figure 3B). In contrast, RNAi knockdown of caspase-9, which transduces signals in the intrinsic apoptotic pathway, did not significantly attenuate LRRK2-induced neuronal death (Figure 3C; this siRNA is effective against HNE-induced neuronal death; Carol Troy, personal communication).

Figure 3. LRRK2-induced neuronal death is caspase-8 dependent.

(A) FADD recruits caspase-8 to LRRK2. 293T cells were transfected with GFP-LRRK2, V5-FADD and caspase-8 inactive mutant (C360S) as indicated. GFP-LRRK2 was immunoprecipitated, and co-purified FADD and caspase-8 were detected by V5 and caspase-8 antibodies, respectively.

(B) Knockdown of caspase-8 blocks LRRK2-induced neurotoxicity. Mouse cortical neurons were incubated with penetratin1-linked scrambled control (Ctrl) or caspase-8 siRNA 24h prior to transfection with GFP-tagged WT or mutant LRRK2. Data are mean ± SEM from three individual experiments of triplicate coverslips (* p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001). A representative immunoblot of caspase-8 levels following treatment with penetratin1-linked siRNA is shown (inset).

(C)Knockdown of caspase-9 fails to prevent LRRK2-induced neuronal death. Caspase-9 RNAi, transfection, and neuronal death were performed and assessed as in (B).

(D)Caspase-8 is selectively activated in brain tissue from patients with LRRK2 PD. Striatal lysates were analyzed by caspase-8 (clone 1C12), caspase-9, and caspase-1 (clone A19) immunoblotting. Caspase-2 was undetectable using three commercial antibodies (not shown). The locations of the pro-caspase isoforms, and their corresponding cleavage products are indicated (* non-specific immunoreactive bands; # potential cleavage products with higher than expected mass: 37 and 35 kDa).

Our results suggest that caspase-8 activation may be a pathogenic event in PD patients with LRRK2 mutations. To further test this notion, we measured whether caspase-8 is activated in brain lysates from control subjects and PD patients with LRRK2 mutations. Caspase-8 is activated by homodimerization (Boatright et al., 2003), which also leads to autoproteolytic processing of the enzyme into multiple smaller species (43kD, 41kD, 18kD and 10kD; the 10kD fragment is not detected by the commercial antibodies 1C12 or C15). The presence of one or more of these cleavage products was found in all patients with LRRK2 mutations (Figure 3D). One of two patients tested with idiopathic disease (i.e., no LRRK2 mutation) also showed low level caspase-8 activation (data not shown); more cases will be required to determine the fraction of idiopathic PD that may show activation of the extrinsic pathway. Processing of caspase-8 can lead to decreased levels of the full-length enzyme (Yang et al., 1998), and we also found markedly decreased levels of pro-caspase-8 in the PD patients with LRRK2 mutations. In contrast, we did not observe a clear pattern of activation for the apical caspases that control the intrinsic pathway (caspase-9) or inflammation-related death signaling (caspase-1) (Figure 3D).

Discussion

Our findings link a PD-causing gene directly to the activation of a cell death signaling pathway, and we provide direct support for this notion with evidence from human postmortem tissue from PD patients bearing two different LRRK2 mutations. We demonstrate that PD-linked mutations enhance the interaction of LRRK2 with FADD, leading to the recruitment and activation of caspase-8. Our data also show that blocking LRRK2 kinase function eliminates the increased FADD binding caused by PD mutations, providing a potential mechanism for how this mutation blocks LRRK2-mediated neuronal death.

Multiple lines of evidence support the notion that apoptotic machinery contributes to neurodegeneration in PD. For example, apoptotic nuclei have been identified in DA neurons of the substantia nigra, and many reports have documented altered levels or activation of key apoptotic molecules in PD postmortem tissue (Vila and Przedborski, 2003). Nevertheless, a longstanding question about such data is whether they indicate a key role for cell death signaling pathways, or reflect a late downstream consequence of PD-related cellular demise. Our data suggest that, at least in patients with LRRK2 mutations, activation of the apoptotic cascade may be an important early event in disease pathogenesis. The significance of these findings is highlighted by the fact that LRRK2 is the most common genetic cause of PD, but future work is necessary to determine the relevance of our findings to idiopathic PD, where a role for LRRK2 is less clearly defined.

Two studies have implicated LRRK2 in the control of neurite morphology (MacLeod et al., 2006; Plowey et al., 2008) and, interestingly, many reports document the presence of cell death signaling molecules in neurites and synaptic terminals (Mattson et al., 1998; Chung et al., 2003; Cowan and Roskams, 2004; Carson et al., 2005). These studies indicate that caspase activation can occur locally within neuronal processes, leading to process degeneration. Particularly relevant to our findings is the study of Roskams and colleagues (Carson et al., 2005) who report that caspase-8 is activated in presynaptic terminals in response to a deafferentating lesion, and is subsequently retrogradely transported to the cell body where it eventually triggers apoptotic cell death. Moreover, a number of extrinsic pathway-related molecules are concentrated within neuronal processes, and this pathway can modulate neuronal process morphology and synaptic function (Meffert et al., 2003; Boulanger and Shatz, 2004; Ma et al., 2006; Stellwagen and Malenka, 2006; Heckscher et al., 2007). Thus, our data raise the possibility that FADD/caspase-8 signaling may contribute to the neuritic pathology associated with LRRK2, and that this process leads to retrograde signaling that ultimately culminates in cell body death. Indeed, such a scenario would be consistent with studies of human PD, suggest that the midbrain dopaminergic neuron degeneration begins in striatal terminal projections and is later followed by cell body death in the substantia nigra (Scherman et al., 1989; Fearnley and Lees, 1991; Lee et al., 2000).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the following people for their helpful comments on the manuscript: Serge Przedborski, Jonathan Javitch, Gilbert DiPaolo, Chris Henderson and members of the Dauer Lab. Thanks also to Kana Tsukamoto for outstanding technical assistance. We also thank Drs. Dennis Dickson and Zbigniew Wszolek of the Mayo Clinic (Jacksonville) for providing LRRK2-positive human brain tissue, Dr. Jean-Paul Vonsattel of the New York Brain Bank for providing control and idiopathic PD brain tissue, and Dr. Lorraine Clarke of Columbia University for genotyping idiopathic PD samples. The plasmid for caspase-8 was a kind gift of Dr. Junying Yuan; the plasmid for LZ-FADD-DD was a kind gift of Dr. Milton Werner; the plasmid for death receptor 3 was a kind gift of Dr. Shie-Liang Hsieh; the LRRK2 antibody was a kind gift of Dr. Zhenyu Yue; the anti-mouse FADD antibody was a kind gift of Dr. Andreas Strasser. This work was supported by NINDS grants K02 NS045798 and R01 NS061098, the Parkinson Disease Foundation and Anne and Bernard Spitzer Center for Cell and Genetic Therapy For Parkinson Disease.

References

- Boatright KM, Renatus M, Scott FL, Sperandio S, Shin H, Pedersen IM, Ricci JE, Edris WA, Sutherlin DP, Green DR, Salvesen GS. A unified model for apical caspase activation. Mol Cell. 2003;11:529–541. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifati V. LRRK2 low-penetrance mutations (Gly2019Ser) and risk alleles (Gly2385Arg)-linking familial and sporadic Parkinson disease. Neurochem Res. 2007;32:1700–1708. doi: 10.1007/s11064-007-9324-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulanger LM, Shatz CJ. Immune signalling in neural development, synaptic plasticity and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:521–531. doi: 10.1038/nrn1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson C, Saleh M, Fung FW, Nicholson DW, Roskams AJ. Axonal dynactin p150Glued transports caspase-8 to drive retrograde olfactory receptor neuron apoptosis. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6092–6104. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0707-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung CW, Hong YM, Song S, Woo HN, Choi YH, Rohn T, Jung YK. Atypical role of proximal caspase-8 in truncated Tau-induced neurite regression and neuronal cell death. Neurobiol Dis. 2003;14:557–566. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2003.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cookson MR, Xiromerisiou G, Singleton A. How genetics research in Parkinson disease is enhancing understanding of the common idiopathic forms of the disease. Curr Opin Neurol. 2005;18:706–711. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000186841.43505.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CM, Roskams AJ. Caspase-3 and caspase-9 mediate developmental apoptosis in the mouse olfactory system. J Comp Neurol. 2004;474:136–148. doi: 10.1002/cne.20120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauer W, Przedborski S. Parkinson disease: mechanisms and models. Neuron. 2003;39:889–909. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00568-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson TJ, Harel S, Arboleda VA, Prunell GF, Shelanski ML, Greene LA, Troy CM. Highly efficient small interfering RNA delivery to primary mammalian neurons induces MicroRNA-like effects before mRNA degradation. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10040–10046. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3643-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearnley JM, Lees AJ. Ageing and Parkinson’s disease: substantia nigra regional selectivity. Brain. 1991;114:2283–2301. doi: 10.1093/brain/114.5.2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festjens N, Vanden Berghe T, Cornelis S, Vandenabeele P. RIP1, a kinase on the crossroads of a cell’s decision to live or die. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:400–410. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloeckner CJ, Kinkl N, Schumacher A, Braun RJ, O’Neill E, Meitinger T, Kolch W, Prokisch H, Ueffing M. The Parkinson disease causing LRRK2 mutation I2020T is associated with increased kinase activity. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:223–232. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldwurm S, et al. The G6055A (G2019S) mutation in LRRK2 is frequent in both early and late onset Parkinson disease and originates from a common ancestor. J Med Genet. 2005;42:e65. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.035568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greggio E, Jain S, Kingsbury A, Bandopadhyay R, Lewis P, Kaganovich A, van der Brug MP, Beilina A, Blackinton J, Thomas KJ, Ahmad R, Miller DW, Kesavapany S, Singleton A, Lees A, Harvey RJ, Harvey K, Cookson MR. Kinase activity is required for the toxic effects of mutant LRRK2/dardarin. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;23:329–341. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L, Gandhi PN, Wang W, Petersen RB, Wilson-Delfosse AL, Chen SG. The Parkinson’s disease-associated protein, leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2), is an authentic GTPase that stimulates kinase activity. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:3658–3670. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann A, Troadec JD, Hunot S, Kikly K, Faucheux BA, Mouatt-Prigent A, Ruberg M, Agid Y, Hirsch EC. Caspase-8 is an effector in apoptotic death of dopaminergic neurons in Parkinson disease, but pathway inhibition results in neuronal necrosis. J Neurosci. 2001b;21:2247–2255. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-07-02247.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayley S, Crocker SJ, Smith PD, Shree T, Jackson-Lewis V, Przedborski S, Mount M, Slack R, Anisman H, Park DS. Regulation of dopaminergic loss by Fas in a 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine model of Parkinson disease. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2045–2053. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4564-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckscher ES, Fetter RD, Marek KW, Albin SD, Davis GW. NF-kappaB, IkappaB, and IRAK control glutamate receptor density at the Drosophila NMJ. Neuron. 2007;55:859–873. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch EC, Hunot S, Hartmann A. Neuroinflammatory processes in Parkinson disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2005;11(Suppl 1):S9–S15. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2004.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iaccarino C, Crosio C, Vitale C, Sanna G, Carrì MT, Barone P. Apoptotic mechanisms in mutant LRRK2-mediated cell death. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:1319–1326. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CS, Samii A, Sossi V, Ruth TJ, Schulzer M, Holden JE, Wudel J, Pal PK, de la Fuente-Fernandez R, Calne DB, Stoessl AJ. In vivo positron emission tomographic evidence for compensatory changes in presynaptic dopaminergic nerve terminals in Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2000;47:493–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis PA, Greggio E, Beilina A, Jain S, Baker A, Cookson MR. The R1441C mutation of LRRK2 disrupts GTP hydrolysis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;357:668–671. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Tan YC, Poulose S, Olanow CW, Huang XY, Yue Z. Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2)/PARK8 possesses GTPase activity that is altered in familial Parkinson disease R1441C/G mutants. J Neurochem. 2007;103:238–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04743.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Li J, Chiu I, Wang Y, Sloane JA, Lu J, Kosaras B, Sidman RL, Volpe JJ, Vartanian T. Toll-like receptor 8 functions as a negative regulator of neurite outgrowth and inducer of neuronal apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 2006;175:209–215. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200606016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod D, Dowman J, Hammond R, Leete T, Inoue K, Abeliovich A. The familial Parkinsonism gene LRRK2 regulates neurite process morphology. Neuron. 2006;52:587–593. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning G, Whyte DB, Martinez R, Hunter T, Sudarsanam S. The protein kinase complement of the human genome. Science. 2002;298:1912–1934. doi: 10.1126/science.1075762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson MP, Keller JN, Begley JG. Evidence for synaptic apoptosis. Exp Neurol. 1998;153:35–48. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1998.6863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy MK, Martinez TN, Ruhn KA, Szymkowski DE, Smith CG, Botterman BR, Tansey KE, Tansey MG. Blocking soluble tumor necrosis factor signaling with dominant-negative tumor necrosis factor inhibitor attenuates loss of dopaminergic neurons in models of Parkinson disease. J Neurosci. 2006;26:9365–9375. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1504-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meffert MK, Chang JM, Wiltgen BJ, Fanselow MS, Baltimore D. NF-kappa B functions in synaptic signaling and behavior. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:1072–1078. doi: 10.1038/nn1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meylan E, Tschopp J. The RIP kinases: crucial integrators of cellular stress. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30:151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plowey ED, Cherra SJ, 3rd, Liu YJ, Chu CT. Role of autophagy in G2019S-LRRK2-associated neurite shortening in differentiated SH-SY5Y cells. J Neurochem. 2008;105:1048–1056. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05217.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherman D, Desnos C, Darchen F, Pollak P, Javoy-Agid F, Agid Y. Striatal dopamine deficiency in Parkinson’s disease: role of aging. Ann Neurol. 1989;26:551–557. doi: 10.1002/ana.410260409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith WW, Pei Z, Jiang H, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Ross CA. Kinase activity of mutant LRRK2 mediates neuronal toxicity. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1231–1233. doi: 10.1038/nn1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stellwagen D, Malenka RC. Synaptic scaling mediated by glial TNF-alpha. Nature. 2006;440:1054–1059. doi: 10.1038/nature04671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vila M, Przedborski S. Targeting programmed cell death in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:365–375. doi: 10.1038/nrn1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West AB, Moore DJ, Biskup S, Bugayenko A, Smith WW, Ross CA, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Parkinson disease-associated mutations in leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 augment kinase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:16842–16847. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507360102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West AB, Moore DJ, Choi C, Andrabi SA, Li X, Dikeman D, Biskup S, Zhang Z, Lim KL, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Parkinson disease-associated mutations in LRRK2 link enhanced GTP-binding and kinase activities to neuronal toxicity. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:223–232. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Chang HY, Baltimore D. Autoproteolytic activation of pro-caspases by oligomerization. Mol Cell. 1998;1:319–325. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80032-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.