Abstract

Objectives

To assess the effect of two health systems approaches to distribute HIV self-tests on the number of female sex workers’ client and non-client sexual partners in a randomized controlled trial of HIV self-testing among female sex workers (FSW) in Zambia.

Design

Cluster randomized controlled trial.

Methods

Peer educators recruited 965 participants. Peer educator-participant groups were randomized 1:1:1 to one of three arms: 1) delivery of HIV self-tests directly from a peer educator, 2) free facility-based delivery of HIV-self tests in exchange for coupons, or 3) referral to standard HIV testing (standard of care). Participants in all three arms completed four peer educator intervention sessions, which included counseling and condom distribution. Participants were asked the average number of client partners they had per night at baseline, one and four months, and the number of non-client partners they had in the past 12 months (at baseline) and in the past month (at one month and four months).

Results

At four months, participants reported significantly fewer clients per night in the delivery arm (mean difference −0.78 clients, 95% CI −1.28 to −0.28, P=0.002) and the coupon arm (−0.71, 95% CI −1.21 to −0.21, P=0.005) compared to standard-of-care. Similarly, they reported fewer non-client partners in the delivery (−3.19, 95% CI −5.18 to −1.21, P=0.002) and in the coupon arm (−1.84, 95% CI −3.81 to 0.14, P=0.07) arm compared to standard-of-care.

Conclusions

Expansion of HIV self-testing may have positive spillover effects on HIV prevention efforts among FSW in Zambia.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02827240

INTRODUCTION

HIV self-testing is a promising strategy to improve HIV testing coverage among diverse populations globally.[1,2] Although HIV self-testing may overcome some traditional barriers to HIV testing, such as stigma or logistical challenges, there may be unintended consequences associated with the use of the test, and these unintended consequences may depend on the strategy for HIV self-testing delivery. Changes in sexual behaviors have been considered following HIV prevention interventions including pre-exposure prophylaxis[3,4], male circumcision[5], and vaccination.[6] Among men who have sex with men (MSM), access to HIV self-testing has resulted in increased awareness of HIV risk that may lead to reduced sexual risk-taking.[7,8]

The relationship between HIV self-testing and sexual behaviors is likely complex. We previously demonstrated that HIV self-testing among female sex workers (FSW) in Zambia did not lead to an increase in HIV testing coverage or status knowledge when compared to referral to existing HIV testing services.[9] Even in the absence of a direct effect of HIV self-testing on status knowledge (which could plausibly lead to sexual behavior change), access to HIV self-testing technology may lead to changes in sexual behaviors. For example, access to HIV self-testing may increase sense of control, as the technology allows freedom of choice of when, where, and with whom to use the test.[10] Furthermore, awareness of and experience with the HIV self-test itself may change perceptions of risk of HIV acquisition, which could lead to changes in sexual behaviors.[11] For example, individuals with access to an HIV self-test may alter their choice of partners if they know they can test themselves or their partner regularly with the self-test.[12] For FSW specifically, access to an HIV self-test may also lead to changes in the price for a sex act. FSW may use the test for themselves or for their clients to generate or demonstrate HIV status information, which could influence the price negotiations. In turn, price differences may lead to changes in income, which could affect the need to sell sex or remain in relationships to sustain a livelihood. Given the potential for these effects, understanding how HIV self-testing influences sexual behaviors is important for HIV self-testing implementation programs, particularly among FSW.

Development of effective HIV testing interventions is particularly important among FSW, given their disproportionate burden of HIV[13] and that engagement in the HIV care cascade remains below UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets.[14–16] Here, we report results of a pre-specified secondary analysis of the Zambian Peer Educators for HIV Self-Testing (ZEST) study, a three-arm randomized controlled trial of HIV self-testing distribution systems among FSW in Zambia, assessing the overall impact of the HIV self-testing interventions on the number of sex partners.

METHODS

Participants and Procedures

The ZEST study was a three-arm cluster randomized trial comparing two HIV self-test distribution systems to standard HIV testing for improving HIV testing among FSW (clinicaltrials.gov NCT02827240). Complete methods for the study have been previously reported.[17] Participants were recruited by trained peer educators in three Zambian transit towns (Livingstone, Chirundu, and Kapiri Mposhi). Participants were eligible if they were at least 18 years of age, reported exchanging sex for money or goods at least once in the previous month, self-reported that they were not living with HIV and had not recently (<3 months) tested for HIV or that they did not know their HIV status, and were permanent residents of their town of enrollment. Each peer educator recruited an average of six participants.

Randomization

The randomization unit was the peer educator plus the participants that she recruited. Peer educator-participant groups were randomized after all participants in the group were enrolled and had completed their baseline assessment. Groups were randomized 1:1:1 to one of three study arms: 1) distribution of the HIV self-test from the peer educator to her participants (direct delivery), 2) distribution of a coupon from the peer educator to her participants, which could be used to collect an HIV self-test free of charge from one of several distribution points in the town (coupon), or 3) referral to existing HIV testing options in the town of recruitment by the peer educator (standard of care). The randomization list was generated in R (Version 3.3.1, The R Foundation for Statistical Computing) in random blocks of 3, 6, and 9 and stratified by town of recruitment. Study assignments for each peer educator were placed in an opaque envelope that was opened by the peer educator and a study staff member, neither of whom knew the assignment beforehand.

Intervention

In all study arms, peer educators discussed HIV risk reduction strategies, distributed condoms, and referred participants to existing facilities for HIV testing at each peer educator visit. In the direct delivery arm, peer educators distributed two OraQuick ADVANCE Rapid HIV-1/2 Antibody self-tests (OraSure Technologies, Bethlehem, PA), one at the first peer educator visit (Week 0) and a second three months later at the final peer educator visit (Week 10). In the coupon distribution arm, peer educators distributed two coupons, at Week 0 and 10, which participants could use to collect a an HIV self-test at a participating health clinic or pharmacy. Staff at the health clinics and pharmacies participating in the study received a brief training on the use of the HIV self-test. There were no other changes in the health facilities or pharmacies with regards to staffing, operating hours, or location. All participants had access to a 24-hour hotline that they could call if they needed help with HIV testing (including using the test and interpreting the test results), experienced an adverse event such as intimate partner violence, or needed another form of assistance. HIV self-testing was unobserved, as the study was designed to mimic a real-world situation where participants could test at the time and place of their choosing. As such, we did not measure reactions to learning HIV status, although severe adverse psychosocial events were screened for at each study visit.

Peer Educator Visits

Participants completed four peer educator intervention visits at Weeks 0, 2, 6, and 10. Study assessments occurred at baseline (prior to randomization and the first peer educator visit), at one month and at four months after the first (Week 0) peer educator visit. Each peer educator visit was conducted following a standardized script. To mimic a real-world peer educator intervention, no study staff were present during peer educator visits. The first peer educator visit in all arms a group visit; subsequent visits were one-on-one. All peer educator visits in all arms consisted of HIV risk reduction counseling, information on where to go for HIV testing, and provision of condoms. In the interventions, peer educators additionally provided a brief training on use of HIV self-tests and distributed either HIV self-test kits or coupons.

Measures

All assessments were completed via computer-assisted personal interviews at three study assessments at the time of enrollment, and at months 1 and 3 following the first peer educator visit. Prior to randomization, participants completed a baseline questionnaire, which covered several domains, including sociodemographic characteristics (age, literacy, educational attainment, mobile phone ownership, monthly income) and sex work history (including the age at which they first started working in sex work, how often condoms were available to them while working and how much they cost, and how much they normally charged for vaginal sex). Having a primary partner was defined as a stable, non-commercial partner such as a husband or boyfriend.

Sexual behaviors with clients and non-client partners were measured at baseline, one, and four months. To measure sexual behaviors with clients, participants were asked on average how many client sexual partners they had per night. At baseline, participants were asked how many non-client partners they had had in the previous 12 months. At one month and four months, participants were asked how many non-client partners they had had in the previous month. At one and four months, participants were asked when their last HIV test was, and the result of this last test.

Statistical Methods

All analyses were intention-to-treat. Pre-specified outcomes included average number of client and non-client partners at one month and four months. We used a mixed-effects generalized linear model with a Gaussian distribution to estimate the mean difference in number of partners (client and non-client) at each time point by study arm. Each model included a fixed effect for randomization arm, study site, and baseline (e.g., baseline average number of partners) and a random effect for peer educator group. Per our pre-specified analysis plan, all analyses were carried out as complete case analyses. All tests were two-sided with no adjustments for multiple comparisons. All analyses were conducted in Stata 14.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

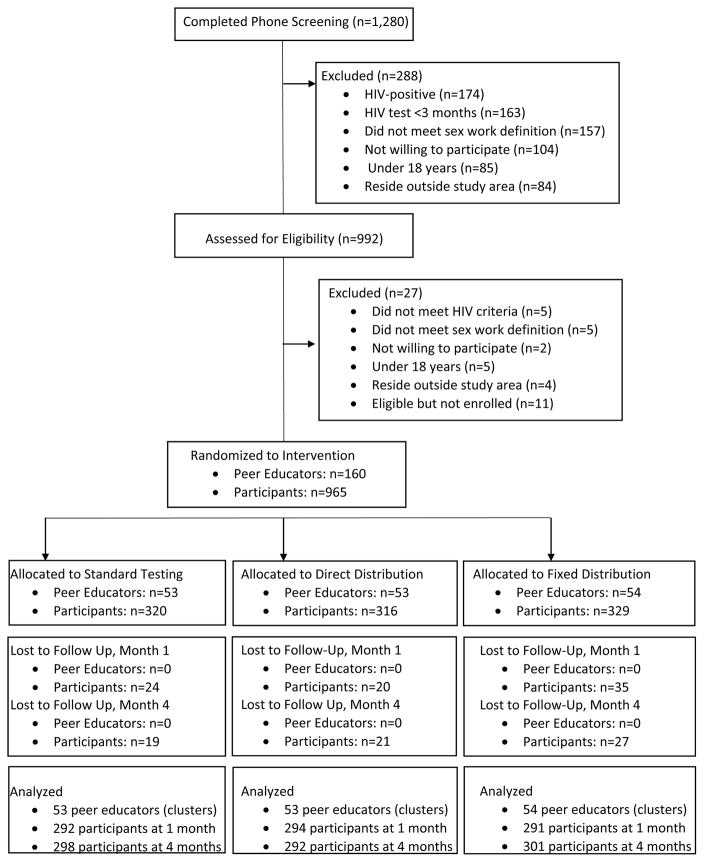

From September to October 2016, 1,280 potential participants were screen and 965 were eligible and enrolled in the study (Figure 1). A mean of 6 participants in 160 peer educator groups were randomized to one of the three study arms. Baseline characteristics were similar between the three groups (Table 1). Participants were a median of 25 years of age (interquartile range [IQR] 21 to 30) and participants had been engaging in sex work for a median of 5 years (IQR 3 to 10 years). Few participants had regular access to free condoms while working. Missing sexual behaviors data were uncommon. At one month, 877/885 (99.1%) of participants who were retained in the study had complete data related to sexual partners. At four months, 891/898 (99.2%) had complete sexual partners data. At one month, 89.3% of participants reported testing for HIV in the previous month, and 79.6% of participants at four months reported testing in the previous month.[9] By four months, only a single participant reported that they had never tested for HIV. At one month, 144 (16.5%) of participants reported that their most recent HIV test was positive, which increased to 235 (26.4%) at four months.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram of screened, randomized, and analyzed participants.

Table 1.

Baseline descriptive characteristics by randomization arm

| Standard Testing (N=320) | Direct HIVST Delivery (N=322) | HIVST Coupon Distribution (N=323) | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age (median, IQR) | 25 (22 to 31) | 25 (21 to 30) | 25 (21 to 30) |

|

| |||

| Site | |||

| Livingstone | 156 (48.8%) | 162 (51.3%) | 162 (49.2%) |

| Kapiri | 87 (27.2%) | 76 (24.1%) | 82 (24.9%) |

| Chirundu | 77 (24.1%) | 78 (24.7%) | 85 (25.8%) |

|

| |||

| Have a primary partner | 203 (63.6%) | 171 (54.1%) | 202 (61.0%) |

|

| |||

| Can read and write | 226 (70.9%) | 243 (77.1%) | 253 (77.9%) |

|

| |||

| Education | |||

| No formal education | 53 (16.6%) | 30 (9.5%) | 25 (7.5%) |

| Primary/Junior | 129 (40.3%) | 152 (48.1%) | 169 (51.5%) |

| Secondary | 131 (40.9%) | 128 (40.5%) | 130 (39.6%) |

| Vocational | 6 (1.9%) | 6 (1.9%) | 1 (0.3%) |

| Tertiary | 1 (0.3%) | 0 | 3 (0.9%) |

|

| |||

| Mobile phone ownership | 271 (84.7%) | 265 (83.9%) | 284 (86.3%) |

|

| |||

| Monthly income | |||

| No income | 81 (25.8%) | 58 (18.7%) | 63 (19.4%) |

| <250 kwacha1 | 40 (12.7%) | 32 (10.3%) | 51 (15.7%) |

| 251–500 kwacha1 | 75 (23.9%) | 86 (27.7%) | 74 (22.8%) |

| 501–1000 kwacha1 | 74 (23.6%) | 82 (26.4%) | 90 (27.8%) |

| 1001–1500 kwacha1 | 17 (5.4%) | 30 (9.7%) | 26 (8.0%) |

| >1500 kwacha1 | 27 (8.6%) | 23 (7.4%) | 20 (6.2%) |

|

| |||

| Years in sex work (median, IQR) | 5 (3 to 10) | 5 (3 to 10) | 5 (3 to 8) |

|

| |||

| Condom availability while working | |||

| Never | 4 (1.3%) | 5 (1.6%) | 8 (2.4%) |

| Seldom/Sometimes | 225 (70.5%) | 217 (68.9%) | 206 (62.6%) |

| Often/Always | 90 (28.2%) | 93 (29.5%) | 115 (35.0%) |

|

| |||

| Condoms available for free while working often/always | 45 (14.4%) | 47 (15.0%) | 53 (16.4%) |

|

| |||

| Number of clients on an average night (mean, SD) | 5.3 (7.5) | 4.6 (8.8) | 4.2 (5.7) |

|

| |||

| Inconsistent condom use with clients | 231 (75.2%) | 236 (78.7%) | 228 (71.0%) |

|

| |||

| Number of non-client partners in the past 12 months (mean, SD) | 17.2 (34.7) | 18.8 (54.3) | 19.5 (64.4) |

|

| |||

| Inconsistent condom use with non-clients | 229 (74.8%) | 209 (69.4%) | 216 (69.5%) |

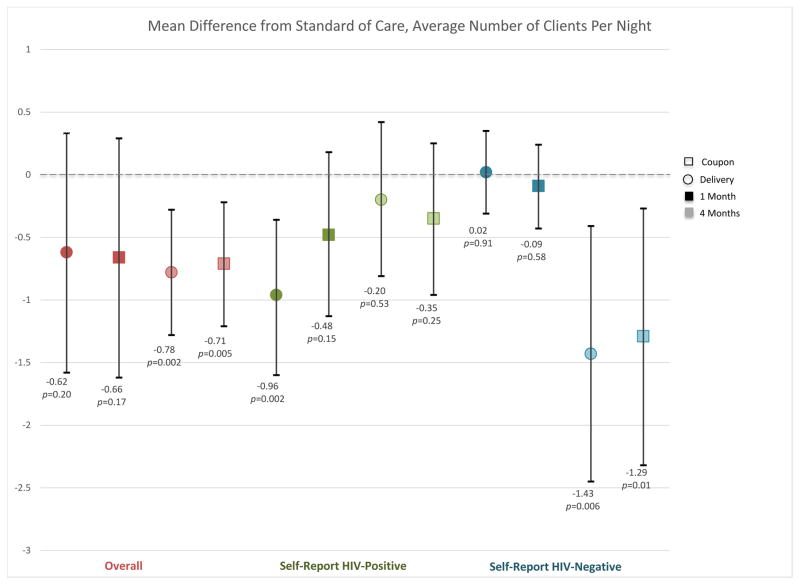

At baseline, the mean number of clients on an average night were reported to be 5.3 (SD 7.5) in the standard testing arm, 4.6 (SD 8.8) in the direct delivery arm, and 4.2 (SD 5.7) in the coupon distribution arm. The number of clients decreased over time in all arms from baseline to one and to four months (Table 2; Figure 2A). Although there was no difference across arms in mean number of clients at one month compared to the standard of care arm, at four months participants reported significantly fewer clients per night in the direct delivery (mean difference −0.78 compared to standard of care, 95% CI −1.28 to −0.28, P=0.002) and coupon (mean difference −0.71 compared to standard of care, 95% CI −1.21 to −0.21, P=0.005). This difference was primarily driven by individuals who reported a negative HIV test at four months. There was no difference in the number of clients among participants who reported testing positive for HIV at four months, but participants in the direct delivery arm who reported a positive HIV test at one month reported significantly fewer clients per night at one month compared to the standard of care arm (mean difference −0.96, 95% CI −1.6 to −0.36, P=0.002).

Table 2.

Average number of clients at each time point by randomization arm

| Average Number of Clients Per Night (SD) | Average Number of Non-Client Partners, Last Month (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| One Month | ||

| Standard | 4.6 (8.9) | 7.8 (21.3) |

| Direct Delivery | 3.9 (2.2) | 3.8 (9.7) |

| Coupon | 3.8 (2.7) | 4.6 (9.1) |

|

| ||

| Four Months | ||

| Standard | 4.3 (3.9) | 6.5 (13.6) |

| Direct Delivery | 3.5 (1.7) | 2.8 (5.0) |

| Coupon | 3.6 (1.6) | 4.2 (7.2) |

|

| ||

| Self-Reported HIV-Positive | ||

|

| ||

| One Month | ||

| Standard | 4.6 (2.5) | 9.9 (16.4) |

| Direct Delivery | 3.5 (1.3) | 2.2 (4.0) |

| Coupon | 3.9 (1.9) | 2.8 (3.0) |

|

| ||

| Four Months | ||

| Standard | 4.1 (1.8) | 8.6 (17.4) |

| Direct Delivery | 3.7 (2.1) | 2.6 (4.2) |

| Coupon | 3.7 (1.6) | 4.1 (6.8) |

|

| ||

| Self-Reported HIV-Negative | ||

|

| ||

| One Month | ||

| Standard | 4.0 (2.7) | 6.3 (22.5) |

| Direct Delivery | 3.9 (1.6) | 3.3 (4.6) |

| Coupon | 3.7 (1.5) | 3.6 (5.0) |

|

| ||

| Four Months | ||

| Standard | 4.4 (4.6) | 5.8 (12.0) |

| Direct Delivery | 3.4 (1.5) | 2.8 (5.2) |

| Coupon | 3.5 (1.4) | 4.0 (7.1) |

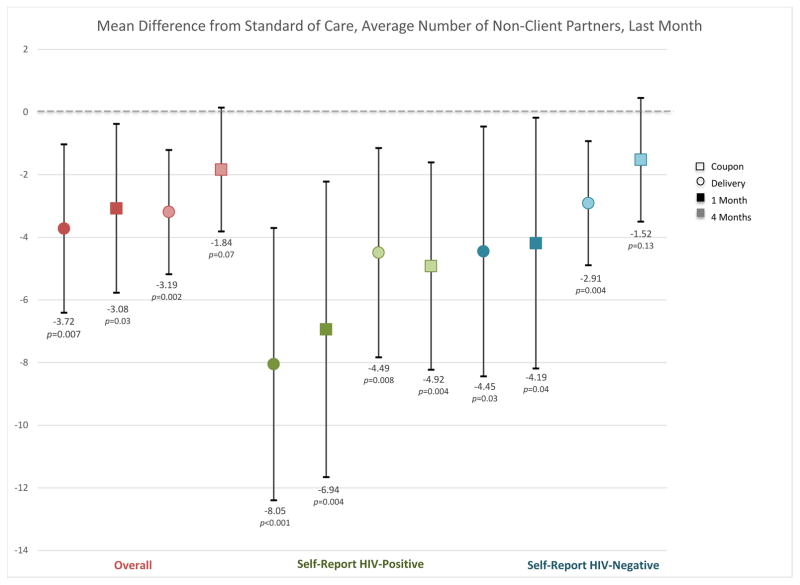

Figure 2.

Mean difference in number of client (2A) and non-client (2B) partners at each time point in the direct delivery (circle) and coupon (square) arms, overall (red) and by self-reported HIV status (negative=green; positive=blue). Darker shading indicates one-month time point and lighter shading indicates the four-month time point. Red indicates the overall effect, green among individuals self-reporting an HIV positive status at their last HIV test, and blue an HIV negative status at their last HIV test. Black bars indicate 95% confidence intervals for the difference from the standard-of-care arm. For each category, the first two point estimates indicate the one month effects (darker shading) and the second two indicate the four month effects (lighter shading).

At baseline, participants reported a mean of 17.2 (SD 34.7) non-client sexual partners over the previous year in the standard arm, 18.8 (SD 54.3) in the direct delivery arm, and 19.5 (SD 64.4) in the coupon distribution arm. In the direct delivery arm, participants reported significantly fewer non-client partners over the previous 30 days at one month (mean difference −3.72, 95% CI −6.41 to −1.03, P=0.007) and at four months (mean difference −3.19, 95% CI −5.18 to −1.21, P=0.002; Figure 2B) compared to the standard of care arm. In the coupon arm, the number of non-client partners decreased at one month compared to the standard of care arm (mean difference −3.08, 95% CI −5.77 to −0.38, P=0.03) but not at four months (mean difference −1.84, 95% CI −3.81 to 0.14, P=0.07; Figure 2B). Both participants who reported testing negative and positive for HIV at each time point reported fewer non-client partners in the past month in the direct delivery and coupon distribution arms compared to the standard arm. Participants reporting that they were HIV-positive at their most recent test reported a larger decrease in the number of partners in the direct delivery and coupon distribution arms relative to the standard arm than those who tested HIV-negative (Figure 2B).

DISCUSSION

In this study of HIV self-testing among FSW in Zambia, access to an HIV self-test led to a significant decrease in the overall number of client and non-client sexual partners. This may have occurred via several mechanisms, independent of acquisition of knowledge of one’s own HIV status. Because HIV self-testing is a user-controlled intervention, and individuals can use it to test in the time and place of their choosing, it may increase perception of control over an individual’s situation. Increasing a sense of agency or empowerment through HIV self-testing may result in participants changing the number of sexual partners.[18]

Women frequently enter sex work because of financial pressures[19], and there are financial incentives for having multiple client partners. Women may have gained demonstrable proof of negative HIV status by self-testing and as a result were able to charge higher prices per sex act than without such proof. In turn, the higher prices per sex act could reduce the number of clients, if FSW have a target income[20], which is plausible. Given that effects were stronger and more consistent among non-client partners, the observed change in sexual partners may not be exclusively driven by economic concerns, although non-client partners often offer housing or other monetary assistance. Women may have reduced their number of partners because they were afraid of partners seeing the test and they had no place to store it. While no serious adverse events related to learning HIV status were reported, we cannot rule out that some women may have had strong emotional reactions to learning their status that influenced behavior or psychosocial well-being leading to fewer sex partners.

Most participants tested for HIV in the previous month, and there was no difference in past-month HIV testing at either time point by arm.[9] While the reduction in the number of client sexual partners at four months was primarily driven by participants who reported that their most recent HIV test was negative, the number of non-client sexual partners for participants reporting both negative and positive test results decreased. For individuals testing HIV-negative, HIV self-testing may enhance HIV prevention efforts both by being another option for frequent re-testing and also by effecting positive change on sexual behaviors. The reduction in client sexual partners may reflect a desire for FSWs to maintain HIV-negative status. For those testing HIV-positive, HIV self-testing may enhance positive prevention leading to a reduction in the number of partners. The reduction in the number of non-client sexual partners among those testing HIV-positive might reflect a desire to avoid transmitting HIV to primary or other non-client partners. However, our results are unlikely to be primarily driven by learning HIV status.

A concern with HIV self-testing is sexual risk-taking behavior could increase following a negative test.[1,21,22] In the present study, we found no evidence that a negative test would lead to increases in sexual risk behavior. On the contrary, participants reporting a negative test reported fewer clients and non-client partners overall. Previous studies of sexual behavior changes following HIV self-testing have overwhelmingly been in MSM in developed-country settings.[1,7,8,23,24] These studies generally demonstrate that HIV self-testing increases awareness of risk and thus leads to reduced sexual risk. However, behavioral patterns following HIV self-testing may differ dramatically for FSW in settings such as Zambia. A qualitative study among FSW in Kenya who distributed HIV self-tests to partners demonstrated that HIV self-testing affected informed sexual decision making with both client and non-client partners.[12] Among primary partners, HIV self-testing allowed women to know that both they and their primary partner were HIV-negative and they would thus not need to use condoms. Among clients, knowledge of a client’s positive HIV status led participants to discontinue relationships with that client.[12] In the present study, participants did not distribute HIV self-tests to their partners, and thus the intervention only led to awareness of the participant’s own HIV status. In combination with evidence from previous studies, the results of this study do not provide evidence that HIV self-testing increases sexual risk behavior. Rather our findings indicate that HIV self-testing may substantially reduce sexual risk-taking and HIV acquisition.

The results of this study must be considered in the context of some limitations. Participants in all arms received a peer educator intervention, which may have masked some effects on sexual behaviors. However, the intervention was randomized and all participants received an identical peer educator intervention. We did not collect data on potential mechanisms driving the reduction in partners seen in this study. The precise mechanisms for the effects are unknown. Qualitative and quantitative research is needed to elucidate which of the several plausible pathways from HIV self-testing to the number of sex partners transmit the effects shown in this study. Such mechanistic insights will be useful in designing future HIV self-testing initiatives and accompanying interventions. Finally, all outcome measures relied on self-report, including sexual behaviors and results of the most recent HIV test. Social desirability bias may have led participants to underreport risky sexual behaviors or positive HIV tests results. However, such bias is unlikely to occur differentially across arms of this randomized trial. As such, we anticipate that any effect of social desirability would bias results towards the null, so that our findings are conservative in estimating sex partner reductions due to the HIV self-testing interventions.

We found no evidence of increases in sexual risk-taking behavior following HIV self-testing in this randomized controlled trial among FSW in Zambia. On the contrary, FSW in HIV self-testing arms of the study reported significantly fewer client and non-client partners. In this setting in Zambia, sexual behavior changes among FSW following HIV self-testing does not appear to be a concern, and thus should not limit expansion of HIV self-testing programs. There may be positive spillover benefits of HIV self-testing related to reduced HIV risk-taking behaviors among FSW.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the research assistants who collected data for this study, the members of the Scientific Oversight Committee, the peer educators, and the participants who dedicated their time to this study.

Funding. The Zambian Peer Educators for HIV Self-Testing (ZEST) study was funded by the International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie). CEO was supported in part by the National Institute on Drug Abuse T32-DA013911 and the National Institute of Mental Health R25-MH083620. KFO was supported in part by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease T32-AI007535. TB was funded by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation through the Alexander von Humboldt Professorship endowed by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research. He was also supported by the Wellcome Trust, the European Commission, the Clinton Health Access Initiative and NICHD of NIH [R01-HD084233], NIAID of NIH [R01-AI124389 and R01-AI112339] and FIC of NIH [D43-TW009775]. OraQuick HIV self-tests were obtained from the manufacturer at cost. The study sponsor was not involved in study design, collection, management, analysis or interpretation of the data, of writing reports or in the decision to submit the report for publication.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest. None to report.

References

- 1.Stevens DR, Vrana CJ, Dlin RE, Korte JE. A Global Review of HIV Self-testing: Themes and Implications. AIDS Behav. 2017:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1707-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krause J, Subklew-Sehume F, Kenyon C, Colebunders R. Acceptability of HIV self-testing: a systematic literature review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1–1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oldenburg CE, Nunn AS, Montgomery M, Almonte A, Mena L, Patel RR, et al. Behavioral Changes Following Uptake of HIV Pre-exposure Prophylaxis Among Men Who Have Sex with Men in a Clinical Setting. AIDS Behav. 2017:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1701-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marcus JL, Glidden DV, Mayer KH, Liu AY, Buchbinder SP, Amico KR, et al. No Evidence of Sexual Risk Compensation in the iPrEx Trial of Daily Oral HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e81997. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Westercamp N, Agot K, Jaoko W, Bailey RC. Risk Compensation Following Male Circumcision: Results from a Two-Year Prospective Cohort Study of Recently Circumcised and Uncircumcised Men in Nyanza Province, Kenya. AIDS Behav. 2014;18:1764–1775. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0846-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Young AM, Halgin DS, DiClemente RJ, Sterk CE, Havens JR. Will HIV Vaccination Reshape HIV Risk Behavior Networks? A Social Network Analysis of Drug Users’ Anticipated Risk Compensation. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e101047–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balán IC, Carballo-Dieguez A, Frasca T, Dolezal C, Ibitoye M. The Impact of Rapid HIV Home Test Use with Sexual Partners on Subsequent Sexual Behavior Among Men Who have Sex with Men. AIDS Behav. 2013;18:254–262. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0497-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frasca T, Balan I, Ibitoye M, Valladares J, Dolezal C, Carballo-Dieguez A. Attitude and Behavior Changes Among Gay and Bisexual Men After Use of Rapid Home HIV Tests to Screen Sexual Partners. AIDS Behav. 2013;18:950–957. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0630-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chanda MM, Ortblad KF, Mwale M, Chongo S, Kanchele C, Kamungoma N, et al. HIV self-testing among female sex workers in Zambia: A cluster randomized controlled trial. PLoS Medicine. 2017;14:e1002442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mathenjwa T, Maharaj P. “Female condoms give women greater control”: A qualitative assessment of the experiences of commercial sex workers in Swaziland. The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care. 2012;17:383–392. doi: 10.3109/13625187.2012.694147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jain AK, Saggurti N, Mahapatra B, Sebastian MP, Modugu HR, Halli SS, et al. Relationship between reported prior condom use and current self-perceived risk of acquiring HIV among mobile female sex workers in southern India. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:S5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-S6-S5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maman S, Murray KR, Napierala-Mavedzenge S, Oluoch L, Sijenje F, Agot K, et al. A qualitative study of secondary distribution of HIV self-test kits by female sex workers in Kenya. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0174629–15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baral S, Beyrer C, Muessig K, Poteat T, Wirtz AL, Decker MR, et al. Burden of HIV among female sex workers in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2012;12:538–549. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.UNAIDS. 90-90-90: An ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta S, Granich R. National HIV Care Continua for Key Populations. Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (JIAPAC) 2017;16:125–132. doi: 10.1177/2325957416686195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cowan FM, Davey C, Fearon E, Mushati P, Mushati, Dirawo J, et al. The HIV Care Cascade Among Female Sex Workers in Zimbabwe: Results of a Population-Based Survey From the Sisters Antiretroviral Therapy Programme for Prevention of HIV, an Integrated Response (SAPPH-IRe) Trial. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2017;74:375–382. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oldenburg CE, Ortblad KF, Chanda M, Mwanda K, Nicodemus W, Sikaundi R, et al. Zambian Peer Educators for HIV Self-Testing (ZEST) Study: Rationale and design of a cluster randomized trial of HIV self-testing among female sex workers in Zambia. BMJ Open. 2017;20:e014780. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robinson JL, Narasimhan M, Amin A, Morse S, Beres LK, Yeh PT, et al. Interventions to address unequal gender and power relations and improve self-efficacy and empowerment for sexual and reproductive health decision-making for women living with HIV: A systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0180699. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swendeman D, Fehrenbacher AE, Ali S, George S, Mindry D, Collins M, et al. “Whatever I Have, I Have Made by Coming into this Profession”: The Intersection of Resources, Agency, and Achievements in Pathways to Sex Work in Kolkata, India. Arch Sex Behav. 2015;44:1011–1023. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0404-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evans RG. The Economics of Health and Medical Care. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK; 1974. Supplier-Induced Demand: Some Empirical Evidence and Implications; pp. 162–173. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wright AA, Katz IT. Home testing for HIV. N Engl J Med. 2006;345:437–440. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walensky RP, Paltiel AD. Rapid HIV testing at home: does it solve a problem or create one? Annals of Internal Medicine. 2006;145:459–462. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-6-200609190-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martinez O, Carballo-Dieguez A, Ibitoye M, Frasca T, Brown W, Balan I. Anticipated and Actual Reactions to Receiving HIV Positive Results Through Self-Testing Among Gay and Bisexual Men. AIDS Behav. 2014;18:2485–2495. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0790-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carballo-Dieguez A, Frasca T, Balan I, Ibitoye M, Dolezal C. Use of a Rapid HIV Home Test Prevents HIV Exposure in a High Risk Sample of Men Who Have Sex With Men. AIDS Behav. 2012;16:1753–1760. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0274-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]