Abstract

We developed a robust automated algorithm called statistical detection of changes (SDC) for detecting morphological changes of multiple sclerosis lesions between two T2w FLAIR brain images. Results from 30 patients show that SDC achieved significantly higher sensitivity and specificity (0.964, 95% CI=0.823–0.994; 0.691, CI=0.612–0.761) than that obtained using the lesion prediction algorithm (0.614, CI=0.410–0.784; 0.281, CI=0.228–0.314), while resulting in a 49% reduction in human review time (p=0.007).

INTRODUCTION

Multiple sclerosis (MS) patients undergo regular MRIs to monitor disease activity and therapeutic response1. Volumetric brain MRI protocols with 1 mm3 isotropic resolution have become increasingly common for imaging MS patients, but result in hundreds of images, making detection of new lesions or changes in lesion morphology very time-consuming for radiologists. One approach to overcoming this problem is to extract lesion masks using a lesion segmentation algorithm2, which are subtracted to yield a lesion change mask. Alternatively, lesion change can be detected on the subtraction of two images either by humans3 or with the help of an algorithm relying on the subtraction signal and lesion geometry4. While image subtraction can substantially improve lesion contrast, separating lesion change from background noise requires consideration of the statistical properties of the signal and noise.

Here we propose a rapid and robust algorithm for statistical detection of changes (SDC) in WM lesions. We describe a specific SDC implementation using the Neyman-Pearson detector in statistics to optimally detect lesion change according to the MRI signal to noise property.

METHODS

SDC lesion detection algorithm

Given two MR images I1 and I2 of the same brain acquired at two time-points, the voxel subtraction signal d = I2 − I1 (Fig.1) is assumed to follow a Gaussian distribution N(μ, σ2) with mean μ and standard deviation σ, where σ can be estimated from the set of non-lesion WM voxels on the subtraction image. Most of these voxels belong to the intersection of the two WM masks obtained by brain segmentation tools (such as FSL5) from T1w structural images. These masks typically exclude large lesions that are hypointense on T1w images and therefore consist mainly of non-lesion voxels (Supplemental Fig.S1).

Figure 1.

Schematic of the proposed SDC lesion change detection algorithm on the T2w FLAIR subtraction image. One unchanged lesion (yellow arrow) and one new lesion (red arrow) are correctly identified by SDC. The algorithm automatically generates red boxes which encompass the detected areas of change on the 2nd FLAIR image to help the human reader quickly identify lesion changes.

The MRI signal to noise property can be used to formulate an optimal SDC of lesions as a composite statistical test between two hypotheses of the following likelihood functions:

H0 (voxel is “unchanged”): p(d | H0) = N(0,σ2)

H1 (voxel is “changed”): p(d | H1) = N(μ,σ2), μ ≠ 0

In this work, the SDC test statistic was computed over a 3-voxel connected neighborhood based on the currently accepted minimum MS lesion size requirement of 3 mm (3 voxels in 1 mm3 isotropic images)6 and on the assumption that the subtraction signals within this small neighborhood are similar. Denoting the subtraction signals at the i-th voxel and its neighbor voxels as di1, …, di3 and assuming μ > 0 (positive change), the test statistic ti can be computed from the log-likelihood ratio test7 and compared with a threshold γ to make a decision:

| [1] |

Here γ was chosen to control the false positive rate PFP = P(ti > γ | H0) According to the Neyman-Pearson lemma, this test provides the best detection power for a given PFP regardless of the unknown mean μ (uniformly most powerful detector)7.

To increase the sensitivity of lesion detection, the test statistic is maximized over all possible neighborhoods surrounding the voxel:

| [2] |

where Vi denotes a 3-voxel connected neighborhood system of the i-th voxel (Fig.S2). Intuitively, this test statistic encodes in probabilistic terms the expectation that a bright voxel on the subtraction image is more likely to be identified as “changed” if at least two of its neighboring voxels also have high signals.

MRI experiment

This was a retrospective study of thirty MS patients with two consecutive brain MRIs (mean scan interval 267±104 days, range 15–410 days) performed on Siemens 3T scanners (MAGNETOM Skyra, VE11A software). The imaging protocol consisted of MPRAGE T1w sequence for brain structure (TR/TE/TI = 2300/2.3/900 ms, 1 mm3 isotropic) and T2w FLAIR sequence for lesion detection (TR/TE/TI = 7600/446/2450 ms, 1 mm3 isotropic). After skull removal and bias field correction, FLAIR images were co-registered into the halfway space using the FLIRT algorithm5 to ensure that the degree of blurring introduced by co-registration was similar between images, as this improves subtraction. To account for changes in image contrast or dynamic range (e.g., due to different receiver gain settings or slight changes in imaging parameters), image intensity normalization was performed prior to subtraction. The robust intensity range (2% and 98% percentiles, denoted as m and M, respectively) was computed for each image. The image intensity of the second image I2 was then scaled linearly to match that of the first image I1 as follows: I2,scaled = αI2 + β, where α = (M1-m1)/(M2-m2) and β = ((M1-αM2)+ (m1-αm2))/2. In addition, brain GM, WM and CSF masks were obtained from T1w image using FAST segmentation algorithm5. The SDC test statistic (Eqs.1&2) was then computed and thresholded to generate a change mask (Fig.1). The false positive rate PFP was set to 0.0001, which means that on average 50 out of approximately 500,000 WM voxels may be incorrectly labeled as “changed”. To reduce the number of false positives, additional constraints were imposed on lesion size (≥3 voxels), location (lesions located within 2 voxels of the CSF border had to be part of a larger lesion that extended outside this border), and intensity on the second FLAIR image (>2 standard deviations above the mean normal appearing WM intensity, i.e., WM voxels that do not appear bright on FLAIR were excluded).

For comparison, the lesion prediction algorithm or LPA, part of the LST toolbox (http://www.applied-statistics.de)8, was used to compute the lesion masks from FLAIR images. This algorithm consists of a binary classifier in the form of a logistic regression model trained on the data of 53 MS patients8. The lesion masks were then subtracted to obtain the change mask without any human revision. Similar to SDC, lesion changes less than 3 voxels were excluded.

Statistical analysis

A neuroradiologist with 6 years of experience reviewed the two FLAIR and the subtraction images with the help of computer-generated color boxes that encompassed the detected lesion changes (Fig.2). These were labeled as “true positive” or “false positive”. The reader also reviewed the images outside of these boxes to count the number of missed (“false negative”) lesions and unchanged (“true negative”) lesions. Lesion changes detected by SDC and LPA were presented in randomized order (both by subject and by detection algorithm) to the reader who was blinded to the algorithm. The image review time was recorded for each subject and algorithm. A two-tailed paired sample t-test was used to compare the mean review time per subject of SDC and LPA. The sensitivity and specificity of each method were calculated using the generalized estimating equation (GEE) logistic regression which accounts for the correlation among the measurements within the same subject9.

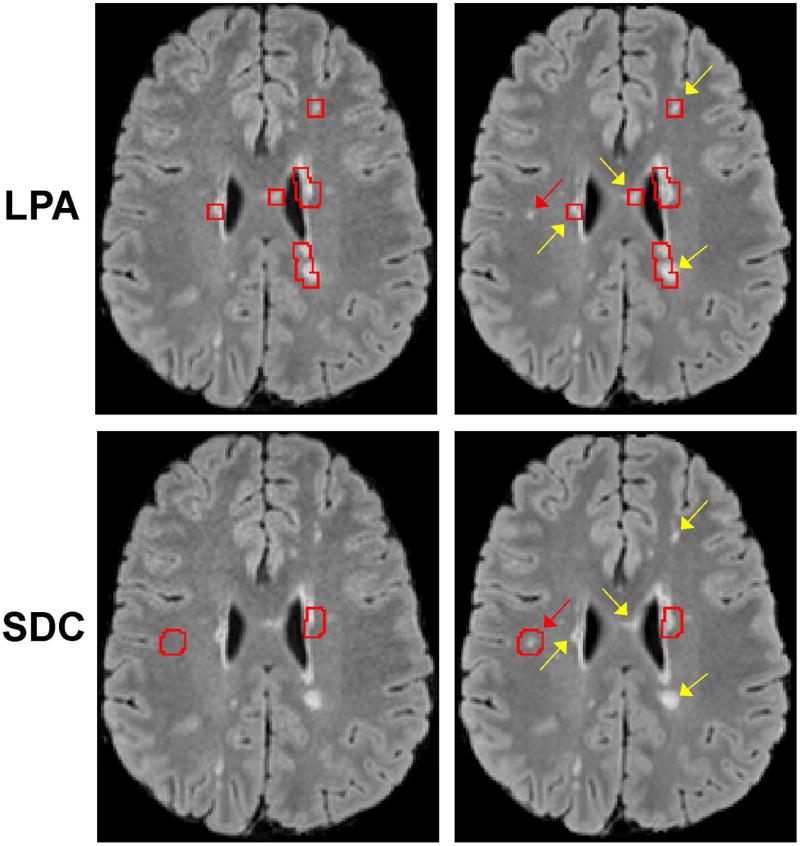

Figure 2.

Comparison of lesion changes identified by LPA and SDC (indicated by the red boxes generated by the algorithms and superimposed on the two source FLAIR images). Each column shows images acquired at a different time point. LPA identifies more false positives (yellow arrows), yet misses a new small lesion (red arrow). SDC correctly classifies positive lesion changes in concordance with the human expert.

RESULTS

Figure 2 shows an example of lesion detection, in which LPA generated more false positives than SDC and missed a small new lesion (also see supplemental Fig.S3). In 30 subjects, SDC detected 344 lesion changes, or an average of 11±7 per subject (range 4–33), while LPA detected 1506 changes or an average of 50±38 per subject (range 5–152). This led to a 49% reduction in human review time per case (116±44 sec, range 50–182 sec, by SDC vs. 229±122 sec, range 76–447 sec, by LPA, p=0.007). Despite fewer detected changes and decreased review time, SDC missed only 2 new lesions as compared to 34 missed lesions by LPA. The false positive rate was 0.241 and 0.735 for SDC and LPA, respectively. With the neuroradiologist’s reading used as the reference standard, SDC achieved both higher sensitivity (0.964, 95% CI=0.823–0.994 by SDC vs. 0.614, CI=0.410–0.784 by LPA) and higher specificity (0.691, CI 0.612–0.761 by SDC vs. 0.281, CI=0.228–0.314 by LPA). Since the 95% CI for SDC does not overlap with that for LPA with regards to both sensitivity and specificity, we concluded that the difference between the two diagnostic methods is statistically significant. Table 1 summarizes the diagnostic accuracy of each algorithm for lesion change detection.

Table 1.

Summary of diagnostic accuracy of SDC and LPA algorithms for detecting positive lesion change (lesion growth) between two FLAIR images with side-by-side image review by a human reader as reference standard.

| True lesion status by human reader | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| change | no change | ||

| Predicted lesion status by SDC | change | 83 | 261 |

| no change | 2 | 824 | |

| True lesion status by human reader | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| change | no change | ||

| Predicted lesion status by LPA | change | 52 | 1454 |

| no change | 34 | 524 | |

DISCUSSION

Our data show that the proposed SDC algorithm based on the optimal Neyman-Pearson detector is a computer-assisted tool that can improve the MS lesion detection rate and decrease image analysis time, thereby reducing reader’s fatigue. The improved robustness of SDC can be attributed to its probabilistic approach which utilizes the statistical properties of the FLAIR subtraction signal within a connected voxel neighborhood to derive an optimal detection threshold for change detection. Although only positive change (lesion growth) was considered, detecting negative change (lesion shrinkage) can be carried out by swapping the order of the FLAIR images. The algorithm was designed to be highly sensitive (0.964 sensitivity) to serve as a screening tool for new lesions while providing a reasonable specificity (only 1 out of 3 unchanged lesions was misclassified, as compared to 3 out of 4 for LPA). We also considered the longitudinal pipeline implemented in LST toolbox8 and found that it has much lower sensitivity (0.386, 95% CI=0.269–0.518) although higher specificity (0.994, CI=0.985–0.999) compared to the LPA mask subtraction method and therefore is less suited for diagnostic purposes. This initial feasibility study has several limitations. We have focused on WM lesions to circumvent the limited contrast of cortical or deep GM lesions on FLAIR. Further studies using pulse sequences tailored for GM lesion detection (e.g., double IR at 7T) are warranted to evaluate SDC for this lesion cohort. Since the majority of subjects (18/30) were imaged at approximately one-year interval, it was not possible to assess statistically whether the accuracy of SDC and LPA varies with follow-up intervals. Comparison with other algorithms and further evaluation on the impact of image interpretation in larger patient imaging datasets are also needed, particularly in those with abrupt anatomical changes between scans which can make image alignment difficult. In conclusion, the SDC lesion change detection algorithm has higher sensitivity/specificity than the LPA algorithm.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by research grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 NS090464) and the National MS Society (RG-1602-07671).

References

- 1.Wattjes MP, Rovira A, Miller D, et al. Evidence-based guidelines: MAGNIMS consensus guidelines on the use of MRI in multiple sclerosis--establishing disease prognosis and monitoring patients. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11:597–606. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carass A, Roy S, Jog A, et al. Longitudinal multiple sclerosis lesion segmentation: Resource and challenge. NeuroImage. 2017;148:77–102. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.12.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Heerden J, Rawlinson D, Zhang AM, et al. Improving Multiple Sclerosis Plaque Detection Using a Semiautomated Assistive Approach. AJNR American journal of neuroradiology. 2015;36:1465–1471. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Battaglini M, Rossi F, Grove RA, et al. Automated identification of brain new lesions in multiple sclerosis using subtraction images. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging : JMRI. 2014;39:1543–1549. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, et al. FSL. NeuroImage. 2012;62:782–790. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Filippi M, Rocca MA, Ciccarelli O, et al. MRI criteria for the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: MAGNIMS consensus guidelines. The Lancet Neurology. 2016;15:292–303. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00393-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kay SM. Fundamentals of Statistical Signal Processing, Volume II: Detection Theory. Prentice Hall; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmidt P. PhD thesis. Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München; 2017. Bayesian inference for structured additive regression models for large-scale problems with applications to medical imaging. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fleiss JL, Levin B, Paik MC. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. Wiley; 2003. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.