Abstract

We replicated and extended Shoda, Mischel, and Peake’s (1990) famous “marshmallow” study, which showed strong bivariate correlations between a child’s ability to delay gratification just before entering school and both adolescent achievement and socioemotional behaviors. Concentrating on children whose mothers had not completed college, we found that an additional minute waited at age 4 predicted a gain of approximately 1/10th of a SD in age-15 achievement. But this bivariate correlation was only half the size of those reported in the original studies, and was reduced by two-thirds in the presence of controls for family background, early cognitive ability, and the home environment. Most of the variation in adolescent achievement came from being able to wait at least 20 seconds. Associations between delay time and age-15 measures of behavioral outcomes were much smaller and rarely statistically significant.

Keywords: gratification delay, marshmallow test, achievement, behavioral problems, longitudinal analysis, early childhood

In a series of studies based on children who attended a preschool on the Stanford University campus, Mischel, Shoda, and colleagues showed that under certain conditions, a child’s success in delaying the gratification of eating marshmallows or a similar treat was related to later cognitive and social development, health, and even brain structure (Mischel et al., 2010; Shoda, Mischel, Peake, 1990; Tsukayama et al., 2009). Although only part of a larger research program investigating how children develop self-control, Mischel and Shoda’s delay time/later outcome correlations and the preschooler videos accompanying them have become some of the most memorable findings from developmental research. Gratification delay is now viewed by many to be a fundamental “noncognitive” skill which, if developed early, can provide a lifetime of benefits (see Mischel et al., 2010 for review).

Since the publication of Mischel and Shoda’s seminal studies (e.g., Mischel, Shoda, Peake, 1988; Mischel, Shoda, Rodriguez, 1989; Shoda et al., 1990), other researchers have examined the processes underlying the ability to delay gratification. Some have modified the Marshmallow Test to illuminate the factors that affect a child’s ability to delay gratification (e.g., Imuta, Hayne & Scarf, 2014; Kidd, Palmeri, & Aslin, 2013; Michaelson & Munakata, 2016; Rodriguez, Mischel, & Shoda, 1989; Shimoni, Asbe, Eyal, & Berger, 2016); others have investigated the cognitive and socio-emotional correlates of gratification delay (e.g., Bembenutty & Karabenick, 2004; Duckworth, Tsukayama, & Kirby, 2013; Romer, Duckworth, Sznitman, & Park, 2010). These studies have added to a growing body of literature on self-control suggesting that gratification delay may constitute a critical early capacity. For example, Moffitt and Caspi demonstrated that self-control – typically understood to be an umbrella construct that includes gratification delay, but also impulsivity, conscientiousness, self-regulation and executive function – averaged across early and middle childhood predicted outcomes across a host of adult domains (Moffitt et al., 2011). Duckworth and colleagues (2013) showed that the relation between early gratification delay and later outcomes was partially mediated by a composite measure of self -control, which has further fueled interventions designed to promote skills that fall under the “self-control” umbrella (e.g., Diamond & Lee, 2011). However, despite the proliferation of work on gratification delay, and the related construct of self -control, Mischel and Shoda’s longitudinal studies still stand as the foundational examinations of the long-run correlates of the ability to delay gratification in early childhood.

Revisiting these studies reveals several limiting factors that warrant further investigation. First, Mischel and Shoda’s reported longitudinal associations were based on very small and highly selective samples of children from the Stanford University community (n’s= 35–89; Mischel et al., 1988; Mischel et al., 1989; Shoda et al., 1990). Although Mischel’s original work included over 600 preschool-aged children (Shoda et al., 1990), follow-up investigations focused on much smaller samples (e.g., for their investigation of SAT and behavioral outcomes, Shoda and colleagues were able to contact only 185 of the original 653 children). Moreover, these children originally underwent variations of the gratification-delay assessment; Mischel experimented with trials in which the treat was obscured from a child’s vision, and some of the children were supplied with coping strategies to help them delay longer. They found positive associations between gratification delay and later outcomes only for children participating in trials in which no strategy was coached and the treat was clearly visible – a circumstance they called the “diagnostic condition.”

For the 35 to 48 children who were tested in the “diagnostic condition” and for whom adolescent follow-up data were available, Shoda and colleagues (1990) observed large correlations between delay time and SAT scores (r(35) = .57 for math; r(35) = .42 for verbal) and between delay time and parent-reported behaviors (e.g., “[my child] is attentive and able to concentrate,” r(48) = .39). These bivariate correlations were not adjusted for potential confounding factors that could affect both early delay ability and later outcomes. Because these findings have been cited as motivation both for interventions designed to boost gratification delay specifically (e.g., Kumst & Scarf, 2015; Murray, Theakston, & Wells, 2015; Rybanska et al., 2017) and for interventions seeking to promote self-control more generally (e.g., Diamond & Lee, 2011; Flook, Goldberg, Pinger, & Davidson, 2014; Rueda et al., 2012), it is important to consider possible confounding factors that might lead bivariate correlations to be a poor projection of likely intervention effects.

In the current study, we pursued a conceptual replication of Mischel and Shoda’s original longitudinal work. Specifically, we examined associations between performance on a modified version of the Marshmallow Test and later outcomes in a larger and more diverse sample of children, and we employed empirical methods that adjusted for confounding factors inherent in Mischel and Shoda’s bivariate correlations. Several considerations motivated our effort. First, replication is a staple of sound science (Campbell, 1986; Duncan, Engel, Claessens, & Dowsett, 2014). Second, Mischel and Shoda’s highly selective sample of children limits the generalizability of their results. Finally, if researchers are to extend Mischel and Shoda’s work to develop interventions, a more sophisticated examination of the long-run correlates of early gratification delay is needed. Interventions that successfully boost early delay ability might have no effect on later life outcomes if associations between gratification delay and later outcomes are driven by factors unlikely to be altered by child-focused programs (e.g., SES, home parenting environment).

Current Study

We used data from the NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development to explore associations between preschoolers’ ability to delay gratification and age-15 academic and behavioral outcomes. We focused most of our analysis on a sample of children born to mothers who had not completed college for two reasons. First, it allowed us to investigate whether Mischel and Shoda’s longitudinal findings extend to populations of greater interest to researchers and policymakers concerned with developing interventions (e.g., Mischel, 2014a). Second, empirical concerns over the extent of truncation in our key gratification delay measure in the college-educated sample limited our ability to assess reliably the correlation between gratification delay and later abilities. Because of these differences, we consider our study to be a conceptual, rather than traditional, replication of Mischel and Shoda’s seminal work (Robbins, 1978).

Method

More complete information regarding study data and measures can be found in the online supplementary material. Here, we provide a brief overview of key study components.

Data

Data for the current study were drawn from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development (SECCYD), a widely used dataset in developmental psychology (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2002). Participants were recruited at birth from ten U.S. sites across the country, providing a geographically diverse although not nationally representative, sample of children and mothers. Participants have been followed across childhood and adolescence, with the last full round of data collection occurring when children were 15 years old.

The current study relies on data collected when children were 54 months of age, and our outcome variables were measured during the grade-1 and age-15 assessments. Our analysis sample was limited to children who had a valid measure of age-54-months delay of gratification, as well as non-missing achievement and behavioral data at age 15 (n=918). For conceptual and analytic reasons (detailed below), we then split our sample based on mother’s education, and we focused much of our analyses on children whose mothers did not report having completed college when the child was one month old (n= 552 – a sample that is ten times larger than the sample size in the Shoda et al., (1990) study).

In Table 1, we present selected demographic characteristics for children included in our analytic sample, split by whether the child’s mother received a bachelor’s degree. For purposes of comparison, we also present the same set of characteristics for a nationally-representative sample of kindergarteners collected 2 to 3 years after our sample’s 54-month wave of data collection (nationally representative data were drawn from the publically-available Early Childhood Longitudinal Survey- Kindergarten Cohort, 1998–1999; more information regarding this dataset can be found in the online supplementary information).

Table 1.

Demographic Comparisons Between the Analytic Samples and a Nationally-Representative Sample of Kindergarten Children (ECLS-K: 1998)

| NICHD SECCYD | ECLSK: 1998 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Children of Non- Degreed Mothers | Children of Degreed Mothers | Nationally Representative Sample | |

| Male | 0.49 | 0.46 | 0.51 |

| Black | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.16 |

| Hispanic | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.19 |

| White | 0.73 | 0.91 | 0.57 |

| Mother’s Age at Child Birth (years) | 26.84 (5.61) |

31.67 (4.01) |

27.28 (6.61) |

| Mother’s Education | |||

| Did Not Complete High School | 0.14 | 0 | 0.14 |

| Graduated from High School | 0.32 | 0 | 0.29 |

| Some College | 0.54 | 0 | 0.33 |

| Bachelor’s Degree or Higher | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.23 |

| Income to Needs Ratio | |||

| Income/ Needs < = 1 | 0.18 | 0 | 0.17 |

| Income/ Needs > 1 & <= 2 | 0.27 | 0.05 | 0.26 |

| Income/ Needs > 2 & <= 3 | 0.25 | 0.19 | 0.16 |

| Income/ Needs > 3 & <= 4 | 0.15 | 0.21 | 0.16 |

| Income/ Needs > 4 | 0.15 | 0.55 | 0.24 |

| Mother Unemployed | 0.29 | 0.23 | 0.32 |

| Number of Children in Home | 2.32 (1.03) |

2.16 (0.83) |

2.49 (1.16) |

| Mother Married | 0.67 | 0.93 | 0.70 |

|

| |||

| Observations | 552 | 366 | 21,242 |

Note. Mean values are presented with standard deviations in parentheses. The ECLS-K estimates were derived from data made publically available by NCES (see online supplementary information file and nces.gov/ecls/). All ECLS-K measures shown were collected during the fall of kindergarten (i.e., 1998), and SECCYD measures were collected during the 54-month interview (i.e., preschool; 1995–1996), except for “mother’s education” and “mother’s age at child’s birth,” which were both collected at the 1-month interview. The ECLS-K variables were weighted using the C1CW0 weight to generate nationally representative estimates.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the children of college completing mothers were largely White (91%), with 55% of them reporting family income that was at least 4 times above the poverty line (i.e., “income to needs” ratio over 4.0), and none of them reporting income at or below the poverty line (i.e., “income to needs” ratio at or below 1.0). The subsample of children with mothers without a college degree were more comparable to the nationally representative sample. In both samples, about 16% of children were Black, mother’s age at birth was approximately 27 years, 14% of mothers did not complete high school, and between 17% and 18% of families were living at or below the poverty line. However, Hispanic children were still underrepresented in this sample, underscoring the fact that although diverse, our data were not nationally representative.

Measures

Delay of gratification

A variant of Mischel’s (1974) self-imposed waiting task (i.e., the “Marshmallow Test”) was administered to children when they were 54 months of age. An interviewer would present children with an appealing edible treat based on the child’s own stated preferences (e.g., marshmallows, M&Ms, animal crackers, etc.). Children were then told that they would engage in a game in which the interviewer would leave the child alone in a room with the treat. If the child waited for 7 minutes, the interviewer would return and the child could eat the treat and receive an additional portion as a reward for waiting. Children who chose not to wait could ring a bell to signal the experimenter to return early, and they would then only receive the amount of candy originally presented. The measure of delay of gratification is then recorded as the number of seconds the child waited, with 7 minutes being the ceiling.

The measure of gratification delay used here differed from the one employed by Mischel (1974) in several noteworthy ways. First, the 7-minute cap was much shorter than Mischel’s maximum assessment length; the children in Mischel’s sample were asked to wait between 15 and 20 minutes, depending on the study, before the assessment ended. In our sample, approximately 55% of children hit the 7-minute ceiling on the measure, presenting a potential analytic challenge to our models. However, we found that the ceiling was much more problematic for higher- than lower -SES children. Children whose mothers obtained college degrees hit the ceiling at a rate of 68%, compared with 45% for children whose mothers did not complete college (p < .001; see Table 2).

Table 2.

Descriptive Characteristics of Key Analysis Variables

| Children of Non- Degreed Mothers | Children of Degreed Mothers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| M (SD) |

M (SD) |

β | P-Value of Difference | |

| Delay of Gratification (minutes waited) | 3.99 (3.08) |

5.38 (2.62) |

0.45 | .001* |

| Delay of Gratification (categories) | ||||

| 7 minutes | 0.45 | 0.68 | 0.21 | .001* |

| 2 to 7 minutes | 0.16 | 0.12 | −0.02 | .324 |

| 0.333 to 2 minutes | 0.16 | 0.10 | −0.06 | .012* |

| < 0.333 minutes | 0.23 | 0.10 | −0.13 | .001* |

| Outcome Measures- Grade 1 | ||||

| Achievement Composite | 108.42 (13.71) |

117.29 (13.47) |

0.63 | .001* |

| Behavior Composite | 49.15 (8.43) |

47.40 (7.87) |

−0.18 | .008* |

| Outcome Measures- Age 15 | ||||

| Achievement Composite | 101.23 (11.63) |

112.72 (13.19) |

0.82 | .001* |

| Behavior Composite | 47.12 (9.37) |

44.50 (8.66) |

−0.27 | .001* |

|

| ||||

| Observations | 552 | 366 | ||

Note. Mean values are presented in each cell, and standard deviations are in parentheses. For the delay of gratification categories (e.g., “< 0.333 minutes”) the proportion of students falling within each category is presented. The sample is split based on mother’s education, and p-values were derived from a series of regressions in which each characteristic was regressed on a dummy for “whether mother graduated from college” and a series of site fixed effects. Values shown in the “β” column represent effect sizes measuring the standardized differences between the two groups.

p< .05

We adopt several approaches to dealing with this truncation problem, principally exploring possible non-linearities in the “time waited”/outcome associations by dividing the distribution of waiting times into discrete intervals. We also focused much of our analyses on the children of mothers who did not complete college, as far fewer of the children in this sample hit the ceiling on the minutes waited measure and, as explained above, this group of children complements the sample of children included in the Mischel and Shoda studies. But because the subsample of children with college-educated mothers allows for a more direct replication of Mischel and Shoda’s famous work (e.g., Shoda et al., 1990), we also present results for them, bearing in mind the limitations imposed by the substantial delay truncation.

Finally, it should also be noted that children in the NICHD study were given only the version of the task that Shoda and colleagues (1990) called the “diagnostic condition” (i.e., the children were not offered strategies and were able to see the treat as they waited).

Academic achievement

Academic achievement was measured using the Woodcock-Johnson Psycho-Educational Battery Revised (WJ-R) test (Woodcock, McGrew, & Mather, 2001), a commonly used measure of cognitive ability and achievement (e.g., Watts, Duncan, Davis-Kean, & Siegler, 2014). For math achievement at grade 1 and age 15, we used the Applied Problems subtest, which measured children’s mathematical problem solving. At grade 1, reading achievement was measured using the Letter Word Identification task, a measure of word recognition and vocabulary, and at age 15, reading ability was measured using the Passage Comprehension test. The Passage Comprehension test asked students to read various pieces of text silently and then answer questions about their content.

For all the WJ-R tests, we used the standard scores, which were normed to have a mean of 100 and SD of 15 in each respective wave. We took the average of the grade-1 math and reading measures and the age-15 math and reading measures, respectively, to create composite measures of academic achievement.

Behavioral problems

Following Shoda et al. (1990), we relied primarily on mothers’ reports of child behavior. Mother-reported internalizing and externalizing behavioral problems were assessed using the Child Behavioral Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991) at age 54 months, first grade, and age 15. The CBCL is a widely used measure of behavioral problems, and it included approximately 100 items rated on 3-point scales that captured aspects of internalizing (i.e., depressive) and externalizing (i.e., anti-social) behavior. As with academic achievement, at grade 1 and age 15 we averaged together the externalizing and internalizing measures to create a behavioral composite score that, before standardization, ranged from 32 to 83, with higher scores indicating higher levels of behavioral problems. We also tested models that used a host of alternative behavioral measures taken from youth reports and direct assessments at age 15; these measures and models are described in the online supplementary material.

Additional covariates

All covariates included in our models are listed in Table 3, and we grouped the covariates into two distinct sets of control variables: “Child Demographic and Home Controls” and “Concurrent 54-Month Controls.”

Table 3.

Control Variable Descriptive Characteristics

|

|

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children of Non-Degreed Mothers | Children of Degreed Mothers | |||||||

|

|

|

|||||||

| Waited 7 Minutes | β | P-Value of Difference | Waited 7 Minutes | β | P-Value of Difference | |||

|

|

|

|||||||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | |||||

|

|

|

|||||||

| Panel 1: Child Demographic and Home Controls | ||||||||

| Child Background | ||||||||

| Male | 0.47 | 0.51 | −0.04 | .338 | 0.45 | 0.50 | −0.05 | .409 |

| White | 0.82 | 0.64 | 0.18 | .001* | 0.94 | 0.85 | 0.10 | .007* |

| Black | 0.07 | 0.24 | −0.15 | .001* | 0.00 | 0.05 | −0.05 | .024* |

| Hispanic | 0.06 | 0.07 | −0.01 | .545 | 0.03 | 0.03 | −0.00 | .962 |

| Other | 0.04 | 0.05 | −0.01 | .530 | 0.03 | 0.07 | −0.05 | .058 |

| Child’s Age at Delay Measure (mos.) | 56.11 (1.11) |

56.01 (1.14) |

0.13 | .105 | 55.99 (1.13) |

55.99 (1.15) |

0.07 | .519 |

| Birth Weight (g) | 3490.23 (478.56) |

3449.02 (540.26) |

0.09 | .320 | 3516.63 (520.52) |

3572.53 (527.17) |

−0.13 | .268 |

| Bracken Standard Score (36 mos.) | 9.06 (2.56) |

7.67 (2.86) |

0.47 | .001* | 10.67 (2.20) |

10.14 (2.35) |

0.19 | .043* |

| Bayley (24 mos.) | 93.89 (12.40) |

85.91 (14.40) |

0.53 | .001* | 100.88 (11.78) |

95.21 (14.10) |

0.41 | .001* |

| Child Temperament (6 mos.) | 3.18 (0.42) |

3.25 (0.38) |

−0.17 | .053 | 3.13 (0.37) |

3.09 (0.43) |

0.07 | .531 |

| Log of Family Income (1 mo - 54 mos.) | 0.89 (0.61) |

0.57 (0.73) |

0.38 | .001* | 1.54 (0.51) |

1.42 (0.56) |

0.14 | .057 |

| Mother’s Age at Birth (years) | 27.75 (5.66) |

26.07 (5.46) |

0.29 | .001* | 31.58 (4.05) |

31.87 (3.91) |

−0.06 | .438 |

| Mother’s Education (years) | 13.00 (1.41) |

12.68 (1.50) |

0.12 | .017* | 17.02 (1.31) |

16.82 (1.26) |

0.07 | .234 |

| Mother’s PPVT | 96.43 (13.38) |

90.47 (17.03) |

0.30 | .001* | 114.10 (15.62) |

105.63 (16.51) |

0.44 | .001* |

| H.O.M.E. Score (36 mos.) | ||||||||

| Learning Materials | 7.20 (2.36) |

5.86 (2.51) |

0.53 | .001* | 8.64 (1.59) |

8.41 (2.20) |

0.12 | .168 |

| Language Stimulation | 6.13 (1.04) |

5.67 (1.24) |

0.46 | .001* | 6.38 (0.84) |

6.17 (1.13) |

0.21 | .046* |

| Physical Environment | 6.16 (1.04) |

5.64 (1.54) |

0.40 | .001* | 6.35 (0.83) |

6.33 (0.91) |

0.07 | .372 |

| Responsivity | 5.67 (1.28) |

5.17 (1.52) |

0.31 | .001* | 6.09 (0.99) |

5.81 (1.30) |

0.21 | .033* |

| Academic Stimulation | 3.43 (1.21) |

2.97 (1.29) |

0.38 | .001* | 3.74 (0.97) |

3.57 (1.29) |

0.17 | .112 |

| Modeling | 3.13 (1.10) |

2.82 (1.14) |

0.29 | .001* | 3.64 (0.93) |

3.51 (1.04) |

0.11 | .285 |

| Variety | 6.80 (1.34) |

6.14 (1.50) |

0.45 | .001* | 7.54 (1.17) |

7.29 (1.36) |

0.17 | .088 |

| Acceptance | 3.39 (0.85) |

3.22 (1.04) |

0.18 | .038* | 3.70 (0.59) |

3.57 (0.82) |

0.13 | .162 |

| Responsivity- Empirical Scale | 5.54 (0.91) |

5.14 (1.29) |

0.37 | .001* | 5.77 (0.52) |

5.55 (0.91) |

0.21 | .026* |

| Panel 2: Concurrent 54-Month Controls | ||||||||

| 54 mos. WJ-R Scores | ||||||||

| Letter-Word Id. | 99.03 (11.98) |

93.22 (12.63) |

0.42 | .001* | 105.93 (12.19) |

102.31 (11.94) |

0.26 | .011* |

| Applied Problems | 104.80 (12.88) |

95.67 (15.72) |

0.57 | .001* | 112.36 (12.13) |

106.06 (12.31) |

0.40 | .001* |

| Picture Vocabulary | 100.54 (13.07) |

93.74 (13.80) |

0.43 | .001* | 109.11 (13.45) |

103.47 (13.58) |

0.36 | .001* |

| Memory for Sentences | 93.21 (15.59) |

85.43 (17.67) |

0.43 | .001* | 100.99 (18.73) |

92.34 (17.45) |

0.49 | .001* |

| Incomplete Words | 98.08 (12.91) |

92.72 (13.52) |

0.41 | .001* | 102.18 (11.69) |

98.05 (11.98) |

0.35 | .001* |

| 54 mos. Child Behavioral Checklist | ||||||||

| Internalizing | 47.36 (9.11) |

47.94 (8.51) |

−0.06 | .477 | 46.55 (8.84) |

46.81 (8.17) |

−0.01 | .988 |

| Externalizing | 51.14 (9.34) |

53.09 (9.84) |

−0.21 | .020* | 50.44 (9.11) |

50.99 (8.53) |

−0.06 | .604 |

|

| ||||||||

| Observations | 251 | 301 | 250 | 116 | ||||

Note. Mean values are presented in each cell, and standard deviations are in parentheses. The p-value column compares children who successfully completed the task and waited 7 minutes to students who did not, and the “β” column presents effect sizes measuring the standardized differences between the two groups. P-values were generated from a series of bivariate regressions in which each variable was regressed on a dummy indicating whether the child completed the marshmallow test, and series of site dummy variables was also included to adjust for site differences. P-values below .001 have been rounded to .001.

p< .05

Child demographic and home controls

Child demographic characteristics (i.e., gender and race), birth weight, mother’s age at the child’s birth, and mother’s level of education were collected at the one month interview via interview with study mothers. Family income was collected from study mothers at the one-, six-, 15-, 24-, 36- and 54-month interviews. We took the average of all non-missing income data over this span, and then log-transformed average family income to restrict the influence of outliers. Mother’s Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT) score was assessed in a lab visit when the focal child was 36 months old. The PPVT is a commonly used measure of intelligence.

We also included early indicators of child cognitive functioning, as measured at age 24 months by the Bayley Mental Development Index (MDI; Bayley, 1991) and at age 36 months by the Bracken Basic Concept Scale (BBCS; Bracken, 1984). The MDI measured children’s sensory-perceptual abilities, as well as their memory, problem solving, and verbal communication skills. The BBCS was an early measure of school readiness skills, and it required students to identify basic letters and numbers.

Child temperament was measured at age 6 months using the Early Infant Temperament Questionnaire (Medoff-Cooper, Carey, & McDevitt, 1993), a 38-item survey to which mothers responded. This questionnaire asked mothers to rate their child on a six point Likert-scale with items focused on the child’s mood, adaptability, and intensity. We took the average score across these items as our measurement of temperament, with higher scores indicating more agreeable dispositions.

Finally, the set of controls measured prior to age 54-months also included indicators of the quality of the home environment, as measured by an observational assessment called the Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment (HOME) inventory (Caldwell & Bradley 1984). The HOME was assessed when the focal child was approximately 36 months old, and it was designed to capture aspects of the home environment known to support positive cognitive, emotional, and behavioral functioning. We used 9 subscales of the HOME in our models: the first eight subscales are commonly used with the HOME measure (Learning Materials, Language Stimulation, Physical Environment, Responsivity, Academic Stimulation, Modeling, Variety, and Acceptance), and the 9thsubscale, called “Responsivity - Empirical Scale,” was derived by NICHD SECCYD study from factor analyses of the HOME items. This final scale was distinct from the traditional “Responsivity” scale, as it included items from the “Language Stimulation” scale that also measured mother responsivity and sensitivity to the child.

Concurrent 54-month controls

For models that included controls for concurrent cognitive and behavioral skills, we also included subscales taken from the age 54-month WJ-R test. As our measure of early reading, we included the Letter-Word Identification task, which tested children’s ability to sound out simple words, and the Applied Problems test at age 54-months was our measure of early math skills. For preschool children, the Applied Problems test requires children to count and solve simple addition problems. We also used the Memory for Sentences and Incomplete Words subtests as measures of cognitive ability. The Incomplete Words test measured auditory closure and processing, and children listened to an audio recording where words missing a phenome were listed off. They were then asked to name the complete word. Finally, the Picture Vocabulary test was a measure of verbal comprehension and crystallized intelligence. In this task, children were asked to name pictured objects. All of these tasks have been widely used as measures of children’s early cognitive skills and their measurement properties have been widely reported (e.g., Watts et al., 2014).

Finally, we also included the mother’s report of children’s externalizing and internalizing problems from the Child Behavioral Checklist at age 54 months. Much like the measure used for age-15 behavioral problems, the 54-month survey included a battery of items designed to assess children’s anti-social and disruptive behavior (i.e., externalizing) and depressive symptoms (i.e., internalizing).

Analysis

Our primary goal was to estimate the association between early gratification delay and long-run measures of academic achievement and behavioral functioning. Like the work of Shoda and colleagues (1990), our data did not include a measure of gratification delay in which between-child differences were generated from some exogenous intervention, so we do not claim that the associations we estimate reflect causal impacts. Instead, our goal was to assess how much bias might be contained in longitudinal bivariate correlations between gratification delay and later outcomes as a result of failure to control for characteristics of children and their environments. Regression-adjusted correlations should provide better guidance regarding whether interventions boosting gratification delay might also improve later achievement and behavior.

To accomplish our analytic goals, we modeled later academic achievement and behavior (measured at both grade 1 and age 15) as a function of an age-54-months measure of gratification delay. We then tested models that added controls for background characteristics and measures of the home environment (see Panel 1 of Table 3) before moving to models that also included measures of cognitive and behavioral skills assessed at age 54 months (see Panel 2 of Table 3).

These two approaches reflect different assumptions regarding how variation in gratification delay ability might arise. Models with controls measured between birth and age 36 months still allow for variation in age -54-months gratification delay caused by the differential development of general cognitive or behavioral skills (e.g., executive function, self-control, etc.) between 36 and 54 months. Put another way, these models contain controls only for factors that even ambitious preschool child-focused interventions are unlikely to alter (e.g., birthweight, temperament at 6 months of age, early home environment).

In contrast, the models with “concurrent 54 months” covariates control for variation in a range of cognitive capacities and behavioral problems developed by age 54 months. They help to isolate the possible effects of an intervention that targets only the narrow set of skills involved with gratification delay (e.g., a program that merely provided children with strategies to help them delay longer; see Mischel, 2014b, p.40), but not concurrent general cognitive ability or socioemotional behaviors.

Although it is impossible to know exactly how individual differences in gratification delay emerge (e.g., changes in parenting, development of cognitive skills), by controlling for factors unlikely to be altered by interventions (e.g., ethnicity, parental background), we can purge our estimates of bias due to observable characteristics that are correlated with gratification delay and later outcomes. If remaining unobserved factors also contribute to gratification delay and later outcomes (e.g., changes in parenting), and if these unobserved factors are unlikely to be altered by a particular intervention, then bias in our estimates may still remain. Yet, our estimates should serve as an improvement over the unadjusted correlations reported previously (e.g., Shoda et al., 1990).

In all models shown, continuous variables were standardized so that coefficients can be read as effect sizes, and all models with control variables included a set of dummy variables for each site to adjust for any between-site differences. In order to account for missing data on control variables, we used SEM with Full Information Maximum Likelihood in Stata 15.0 to estimate all analytic models. Finally, we report all estimated p-values to the thousandth decimal place (with p-valued below .001 displayed as “< .001”), and we describe any estimate corresponding to a p-value less than 0.05 as “statistically significant.” Though we recognize the arbitrariness of focusing only on results with a p-value less than .05, we selected this alpha level because it was the minimum threshold for statistical significance used in the studies we attempted to replicate and extend (i.e., Mischel et al., 1988; Mischel et al., 1989; Shoda et al., 1990). Consequently, any differences in conclusions reached between our studies and the previous literature should be attributed to design and sample differences rather than alpha level choices.

Results

Descriptive Findings

Table 2 provides descriptive results for key analysis variables, including the 54-months delay of gratification measure, split by mother’s education level. In the sample of children with non-degreed mothers, children waited an average of 3.99 minutes (SD= 3.08) before ending the task. We also present the proportion of children falling within certain ranges on the measure, with the “7 minute” category representing children who successfully completed the trial. In the lower-SES sample, 45% of children waited the maximum of 7 minutes, and 23% waited less than 20 seconds (i.e., 0.33 minutes). In the higher-SES sample, only 10% of children waited less than 20 seconds, and the average time waited was 5.38 minutes [statistically significantly longer than the lower-SES group (p < .001)].

Because the 7-minute ceiling presented a potential analytic challenge for both samples, we estimated models that substituted the four dummy categories shown in Table 2 for the continuous “minutes waited” variable as a way to assess nonlinearities in the relationship between delay time and academic and socioemotional outcomes. Importantly, these models also provide information on how much our analysis might be compromised by the seven-minute truncation.

Table 3 presents descriptive information for the various control measures used in the analysis, and means are presented separately for children that did and did not complete the delay task. In both the higher- and lower-SES samples, performance on the gratification delay task was highly correlated with differences on most observable characteristics considered. For example, for children from non-degreed mothers, those who completed the gratification delay task were from higher income families (p < .001) than non-completers, had mothers with higher PPVT scores (p < .001), and had higher scores on dimensions of the H.O.M.E. observational assessment (p ranged from .04 to < .001). Null or smaller differences were generally observed for the children of degreed mothers, perhaps owing to the lack of heterogeneity in this subsample.

Regression Results

Results for children of non-degreed mothers

Table 4 presents coefficients and standard errors from models that estimate the association between 54-months gratification delay and our first-grade and age-15 achievement and behavioral composites for the sample of children from non-degreed mothers. Panel 1 of Table 4 displays results for a standardized continuous measure of gratification delay (i.e., the number of minutes waited during the Marshmallow Test). As Column 1 reflects, the bivariate association between minutes waited and academic achievement was 0.28 (SE = 0.04, p < .001), considerably less than the .57 correlation Shoda and colleagues found for SAT math scores and the .42 correlation they found for verbal scores. These linear results suggest that children’s grade-1 achievement would improve by approximately 1/10th of a SD for every additional minute waited at age 4. When the controls measured prior to age 54 months (i.e., second column of Table 3) were added to the model, the standardized association fell to 0.10 (SE = 0.03, p = .002), and when concurrent 54-months controls were added (i.e., third column of Table 1), the association fell to a statistically non-significant 0.05 (SE = 0.03, p = .114).

Table 4.

Associations Between Age 54-month Gratification Delay and Later Measures of Academic Achievement and Behavior for Children of Mothers Without College Degrees

| Achievement Composite | Behavior Composite | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| First Grade | Age 15 | First Grade | Age 15 | |||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| PANEL 1 | ||||||||||||

| Delay minutes (continuous) | 0.279* (0.038) |

0.102* (0.033) |

0.047 (0.030) |

0.236* (0.037) |

0.081* (0.034) |

0.050 (0.032) |

−0.060 (0.043) |

−0.015 (0.044) |

0.023 (0.044) |

−0.062 (0.046) |

−0.026 (0.047) |

0.003 (0.042) |

| PANEL 2 | ||||||||||||

| Delay minutes (categorical) | ||||||||||||

| <0.333 minutes | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| 0.333– 2 minutes | 0.298* (0.126) |

0.189 (0.105) |

0.127 (0.093) |

0.353* (0.122) |

0.230* (0.103) |

0.178 (0.098) |

0.055 (0.144) |

0.090 (0.138) |

0.079 (0.105) |

−0.140 (0.152) |

−0.071 (0.148) |

−0.106 (0.132) |

| 2 to 7 minutes | 0.424* (0.126) |

0.206 (0.104) |

0.041 (0.093) |

0.457* (0.123) |

0.300* (0.103) |

0.235* (0.099) |

−0.088 (0.144) |

−0.020 (0.137) |

0.039 (0.106) |

−0.182 (0.151) |

−0.109 (0.145) |

−0.053 (0.131) |

| 7 minutes | 0.720* (0.098) |

0.284* (0.086) |

0.141 (0.078) |

0.646* (0.098) |

0.234* (0.088) |

0.150 (0.084) |

−0.121 (0.112) |

−0.007 (0.114) |

0.072 (0.087) |

−0.193 (0.120) |

−0.095 (0.123) |

−0.048 (0.111) |

| p-value of test of equality of all categories | .001* | .012* | .247 | .001* | .015* | .093 | .477 | .866 | .837 | .428 | .861 | .885 |

| p-value of test of equality of 2nd, 3rd and 4th categories | .001* | .563 | .475 | .015* | .752 | .630 | .382 | .700 | .923 | .927 | .969 | .882 |

| Child demographic and H.O.M.E. controls | - | Inc. | Inc. | - | Inc. | Inc. | - | Inc. | Inc. | - | Inc. | Inc. |

| Concurrent 54-month controls | - | - | Inc. | - | - | Inc. | - | - | Inc. | - | - | Inc. |

Note. n= 552. Standard errors are in parentheses. Continuous variables were standardized, so coefficients can be interpreted as effect sizes. Estimates shown in the first column of each set (i.e., columns 1, 4, 7, and 10) only contained the measure of delay of gratification and a given outcome measure. Estimates shown in the second column of each set (i.e., columns 2, 5, 8, and 11) added child demographic characteristics, H.O.M.E. scores, and site dummy variables. Estimates shown in the third column of each set (i.e., columns 3, 6, 9, and 12) added other behavioral and cognitive measures also measured at age 54 months. P-values were generated from post-hoc Chi-square tests in order to assess whether respective sets of variables were different from one another. P-values below 0.001 have been rounded to 0.001.

p< .05

Columns 4 through 6 show analogous models for the age-15 measure of achievement. The magnitudes of the age-15 correlations were remarkably similar to the first-grade correlations. The age-15 achievement correlation in the absence of other controls was of moderate size and statistically significant (β= 0.24, SE= 0.04, p < .001), but fell substantially when controls for earlier characteristics were added (β= 0.08, SE= 0.03, p = .016) and became non-significant when 54-months controls were added (β= 0.05, SE= 0.03, p = .140). Given that Shoda and colleagues found almost as strong correlations with later behavior as with later achievement, we were surprised to find virtually no relationship – even in the absence of controls – between gratification delay and the composite score of mother-reported internalizing and externalizing at either grade 1 or age 15 (right half of Table 4).

Children who waited less than 20 seconds (i.e., the lowest category) served as the comparison group for our models that represented delay times in a set of dummy variables (see Table 2 for the proportion of students in each category). As shown in Panel 2 of Table 4, models of outcomes at both grade 1 and age 15 that lack control variables show a strong gradient between gratification delay and later achievement . Relative to children who waited less than 20 seconds, children who waited between 20 seconds and 2 minutes scored about 1/3 of a SD higher on the achievement measure at grade 1 and age 15, and this difference grew to nearly 3/4thof a SD for the group that waited the entire 7 minutes. The “p-value of test of equality of 2nd, 3rd, and 4thcategories” entry in the first column shows that the coefficients produced by the three groups of children who waited longer than 20 seconds differed significantly from one another (p < .001), as did coefficient differences across all four categorical variables(the p-value for which is shown in the “p-value of test of equality of all categories” row).

At both grade 1 and age 15, when controls for early child and family characteristics were added to the model (Column 2 for grade 1; Column 5 for age 15), the coefficients estimated for all three delay-time groups fell by roughly 50%. Surprisingly, the addition of the background controls also flattened out the gradient of the prediction across the gratification delay distribution. Relative to the <20 second reference group, achievement differences for children who waited more than 20 seconds, but not the full 7 minutes, were strikingly similar to the difference for children who waited the full 7 minutes. At age 15, the threshold nature of the relationship was most apparent; the coefficients produced by the three groups that waited longer than 20 seconds all fell between 0.23 and 0.30, and were not close to being statistically significantly different from one another (p = .752).

When concurrent 54-months controls were added, coefficients fell even further. At age 15, only the coefficient produced by the group describing children who waited 2 to 7 minutes retained statistical significance (β= 0.24, SE = 0.10, p = .018), though once again the set of coefficients on the included categories of delay time did not differ from one another (p = .630). As with the models shown in the right half of Panel 1, we found no statistically significant relationships between gratification delay and the first-grade and age-15 behavioral composites.

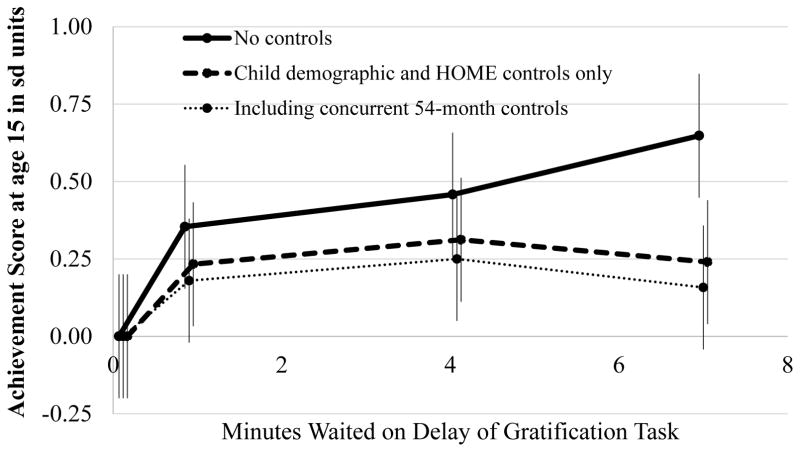

In our focal case of age-15 achievement, the return for delaying gratification appeared to be driven by differences between children who managed to wait at least 20 seconds and those who did not. Figure 1 illustrates this threshold effect with three lines showing the coefficients produced by our gratification-delay categories in the age-15 achievement models. The solid line shows coefficients drawn from the no-control model (i.e., Column 4 of Panel 2), the dashed line shows coefficients from the model with early controls (i.e., Column 5 of Panel 2), and the dotted line shows coefficients produced by models with the 54-months controls (i.e., Column 6 of Panel 2).

Figure 1. Predicted Achievement Scores by Minutes of Delay for Children of Mothers With No College Degree.

Note. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. For each of the 4 discrete groups described in the note of Table 2, we graphed the deviation in achievement composite scores from the reference group (delay <20 seconds) against the within-group average amount of time waited on the x-axis. The average wait times for the “No Controls” and “Child Demographic and HOME Controls Only” groups are displaced by ±.025 to distinguish the sets of error bars. The “High Delay” group’s coefficients are plotted at 7 minutes, although the 7-minute truncation prevents us from knowing what the mean value of minutes waited would have been for this group in the absence of the 7-minute limit.

The uncontrolled line has a steep initial jump, followed by a more gradual increase for wait times longer than 20 seconds. Both “with controls” lines decrease after four minutes. Using 7 minutes to anchor the “more than 7 minutes” group is probably an underestimate, but it is clear from the downward trajectory that no assumptions about the distribution of wait times above 7 minutes would produce a strong positive slope for the last segment of the line. Thus, in the case of children with mothers who lack college degrees, the truncation of delay time at seven minutes does not affect the conclusion that children with the highest delay times show similar achievement levels at age 15 as other children who are able to delay for at least 20 seconds.

Results for children from mothers with college degrees

In Table 5, we present key results for children of mothers with college degrees. As with the results in Table 4, we again present results for the continuous measure of gratification delay (Panel 1) and the categorical measures split along parts of the gratification delay distribution (Panel 2). For the continuous measure, we again found evidence of positive unadjusted associations between gratification delay and later achievement at both first grade (β = 0.18, SE = 0.06, p = .001) and age 15 (β= 0.17, SE = 0.06, p = .007), and the categorical results suggested that much of this association was somewhat linear through the distribution. For the age 15 models, these relations became statistically indistinguishable from 0 once controls were added, and the point estimate for the “> 7 minute” was surprisingly small and negative (β = −0.04, SE = 0.15, p = .816). As with the models shown in Table 4, we again found no evidence of associations between gratification delay and the behavioral measures at first grade or age 15 in the high -SES sample.

Table 5.

Associations Between Age 54 Gratification Delay and Later Measures of Academic Achievement and Behavior for Children of Mothers with College Degrees

| Achievement Composite | Behavior Composite | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| First Grade | Age 15 | First Grade | Age 15 | |||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| PANEL 1 | ||||||||||||

| Delay minutes (continuous) | 0.178* (0.056) |

0.120* (0.053) |

0.048 (0.045) |

0.167* (0.062) |

0.062 (0.059) |

0.007 (0.054) |

−0.049 (0.057) |

−0.059 (0.061) |

−0.050 (0.046) |

0.031 (0.059) |

0.038 (0.063) |

0.043 (0.055) |

| PANEL 2 | ||||||||||||

| Delay minutes (categorical) | ||||||||||||

| <0.333 minutes | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| 0.333– 2 minutes | 0.327 (0.220) |

0.039 (0.198) |

0.148 (0.168) |

0.079 (0.245) |

−0.131 (0.216) |

−0.085 (0.197) |

−0.069 (0.227) |

−0.088 (0.228) |

−0.184 (0.173) |

−0.065 (0.231) |

0.027 (0.232) |

−0.083 (0.200) |

| 2 to 7 minutes | 0.397 (0.206) |

0.147 (0.184) |

0.134 (0.155) |

0.216 (0.227) |

0.028 (0.199) |

−0.032 (0.182) |

−0.277 (0.210) |

−0.240 (0.209) |

−0.265 (0.157) |

−0.318 (0.218) |

−0.217 (0.216) |

−0.227 (0.185) |

| 7 minutes | 0.562* (0.166) |

0.301 (0.154) |

0.193 (0.131) |

0.404* (0.183) |

0.077 (0.166) |

−0.036 (0.152) |

−0.194 (0.168) |

−0.208 (0.174) |

−0.214 (0.131) |

−0.007 (0.174) |

0.068 (0.180) |

0.052 (0.155) |

| p-value of test of equality of all categories | .005* | .100 | .521 | .059 | .674 | .979 | .515 | .584 | .350 | .267 | .367 | .227 |

| p-value of test of equality of 2nd, 3rd and 4th categories | .238 | .153 | .843 | .149 | .477 | .948 | .629 | .753 | .867 | .147 | .206 | .115 |

| Child demographic and H.O.M.E. controls | - | Inc. | Inc. | - | Inc. | Inc. | - | Inc. | Inc. | - | Inc. | Inc. |

| Concurrent 54-month controls | - | - | Inc. | - | - | Inc. | - | - | Inc. | - | - | Inc. |

Despite statistically non-significant results, point estimates were sometimes positive and substantial (e.g., the “2 to 7 minutes” group coefficient shown in Column 1; β= 0.40, SE = 0.21, p = .054) but the standard errors were nearly double those estimated for children of non-degreed mothers (Table 4). This is due in part to the somewhat smaller sample size for the high-SES sample but also to the lack of variation in the gratification delay measure for this sample. Thus, although we found even less evidence of associations between gratification delay and measures of later achievement when considering only the children of mothers with college degrees, it is difficult to draw strong conclusions from these models given the imprecise nature of their coefficient estimates.

Additional results and sensitivity checks

Heterogeneity

Because we found little evidence supporting associations between early delay ability and later outcomes for the higher-SES sample, we next tested whether the different pattern of results observed between the higher- and lower-SES samples constituted a statistically significant difference. In Table 6, we present models that included interaction terms between the various measures of gratification delay (i.e., the continuous and categorical measures) and the indicator for whether the subject’s mother completed college. None of the interactions tested were statistically significant, and our series of “joint F-tests” indicated that the set of interactions for the categorical measures of gratification delay did not statistically significantly contribute to any of the models (p-values ranged from .342 to .968). However, as with the models that were run solely on the sample of children with college educated mothers, standard errors were quite large for the interaction terms, indicating a substantial level of statistical imprecision. Unfortunately, the wide confidence intervals on many of the interaction terms render it impossible to provide a definitive answer to whether the relation between early delay ability and later achievement differs by SES.

Table 6.

Associations Between Age 54 month Gratification Delay and Later Measures of Academic Achievement with Interactions Between Gratification Delay and SES

| Achievement Composite | Behavior Composite | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| First Grade | Age 15 | First Grade | Age 15 | |||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| PANEL 1 | ||||||||||||

| Delay minutes (continuous) | 0.279* (0.038) |

0.115* (0.035) |

0.050 (0.030) |

0.236* (0.040) |

0.083* (0.037) |

0.040 (0.034) |

−0.059 (0.042) |

−0.019 (0.043) |

0.012 (0.033) |

−0.062 (0.044) |

−0.023 (0.046) |

0.009 (0.040) |

| High-SES Indicator | 0.509* (0.064) |

0.050 (0.068) |

0.032 (0.059) |

0.747* (0.067) |

0.270* (0.071) |

0.266* (0.066) |

−0.187* (0.070) |

0.026 (0.084) |

0.031 (0.064) |

−0.286* (0.074) |

−0.119 (0.088) |

−0.127 (0.077) |

| Interaction | −0.101 (0.067) |

−0.043 (0.058) |

−0.035 (0.050) |

−0.069 (0.069) |

−0.007 (0.061) |

−0.018 (0.057) |

0.010 (0.073) |

−0.038 (0.071) |

−0.058 (0.054) |

0.094 (0.076) |

0.040 (0.075) |

0.017 (0.066) |

| PANEL 2 | ||||||||||||

| Delay minutes (categorical) | ||||||||||||

| <0.333 minutes | ref. | ref. | ref. | ref. | ref. | ref. | ref. | ref. | ref. | ref. | ref. | ref. |

| 0.333– 2 minutes | 0.298* (0.127) |

0.182 (0.110) |

0.109 (0.096) |

0.353* (0.131) |

0.202 (0.115) |

0.151 (0.107) |

0.055 (0.140) |

0.060 (0.137) |

0.050 (0.104) |

−0.140 (0.148) |

−0.082 (0.145) |

−0.097 (0.127) |

| 2 to 7 minutes | 0.424* (0.127) |

0.215 (0.110) |

0.053 (0.097) |

0.457* (0.132) |

0.288* (0.115) |

0.199 (0.108) |

−0.088 (0.140) |

−0.046 (0.137) |

0.006 (0.105) |

−0.182 (0.146) |

−0.103 (0.143) |

−0.024 (0.126) |

| 7 minutes | 0.721* (0.099) |

0.308* (0.090) |

0.147 (0.079) |

0.646* (0.105) |

0.222* (0.097) |

0.121 (0.091) |

−0.121 (0.109) |

−0.025 (0.112) |

0.034 (0.086) |

−0.193 (0.116) |

−0.087 (0.120) |

−0.028 (0.106) |

| High-SES Indicator | 0.585* (0.174) |

0.154 (0.156) |

0.041 (0.136) |

0.951* (0.178) |

0.428* (0.163) |

0.417* (0.151) |

−0.097 (0.187) |

0.163 (0.190) |

0.191 (0.144) |

−0.375 (0.195) |

−0.185 (0.199) |

−0.138 (0.174) |

| Interactions | ||||||||||||

| High SES * < 0.333 min. | 0.029 (0.252) |

−0.164 (0.218) |

0.032 (0.190) |

−0.274 (0.259) |

−0.337 (0.226) |

−0.266 (0.210) |

−0.124 (0.275) |

−0.127 (0.269) |

−0.160 (0.205) |

0.075 (0.284) |

0.119 (0.276) |

0.035 (0.243) |

| High SES * 2 to 7 min | −0.027 (0.240) |

−0.138 (0.206) |

0.010 (0.179) |

−0.241 (0.246) |

−0.293 (0.213) |

−0.258 (0.198) |

−0.188 (0.260) |

−0.185 (0.252) |

−0.199 (0.192) |

−0.136 (0.272) |

−0.090 (0.261) |

−0.156 (0.229) |

| High SES * 7 min | −0.159 (0.192) |

−0.119 (0.165) |

−0.033 (0.144) |

−0.242 (0.197) |

−0.119 (0.173) |

−0.134 (0.161) |

−0.073 (0.207) |

−0.167 (0.201) |

−0.203 (0.153) |

0.186 (0.217) |

0.115 (0.212) |

0.049 (0.186) |

| P-value from interaction term joint F-test | .668 | .870 | .968 | .640 | .342 | .507 | .899 | .859 | .610 | .450 | .753 | .720 |

| Child demographic and H.O.M.E. controls | Inc. | Inc. | Inc. | Inc. | Inc. | Inc. | Inc. | Inc. | ||||

| Concurrent 54-month controls | Inc. | Inc. | Inc. | Inc. | ||||||||

Note. n= 918. Standard errors are in parentheses. The “joint F-test” evaluated whether the set of interaction terms jointly contribute to the model. In other words, it tested whether the set of interactions were statistically significantly different from “0.”

p< .05

Measurement considerations

In Table 7, we present correlations between the Marshmallow Test and all analysis variables for the full sample of children considered in our analyses (n = 918; see the supplementary file for correlation matrices for both the low-SES and high-SES samples, respectively). In Table 7, we also included the 54-month measure of the Continuous Performance Task (CPT), which is a commonly used indicator of attention and impulsivity, and we included the Duckworth et al. (2013) parent- and teacher-report index of 54-month self-control (see the supplementary file for measurement details). We included these additional measures to further investigate how the Marshmallow Test might relate to theoretically relevant constructs (see Diamond & Lee, 2011). Surprisingly, the Marshmallow Test had the strongest correlation with the Applied Problems subtest of the WJ-R (r(916) = 0.37, p < .001), and correlations with measures of attention, impulsivity and self-control were lower in magnitude (ranging from 0.22 to 0.30, p < .001). Although these correlational results were far from conclusive, they suggest that the Marshmallow Test should not be thought of as a mere behavioral proxy for self-control, as the measure clearly relates strongly to basic measures of cognitive capacity.

Table 7.

Correlations Between All Analysis Variables

| PANEL 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gratification Delay (54) | ||||||||||

| 1 Continuous | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 2 <0.333 min. | −0.69 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 3 0.333– 2 min. | −0.47 | −0.18 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 4 2 to 7 min. | −0.07 | −0.19 | −0.16 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 5 7 min. | 0.90 | −0.51 | −0.43 | −0.45 | 1.00 | |||||

| Related Measures | ||||||||||

| 6 Self-control (54) | 0.24 | −0.15 | −0.15 | −0.03 | 0.24 | 1.00 | ||||

| 7 Attention (54) | 0.22 | −0.18 | −0.07 | −0.08 | 0.24 | 0.15 | 1.00 | |||

| 8 Impulsivity (54) | −0.30 | 0.26 | 0.06 | 0.05 | −0.28 | −0.28 | −0.26 | 1.00 | ||

| Outcome Measures | ||||||||||

| 9 Achievement (G1) | 0.31 | −0.26 | −0.08 | −0.03 | 0.28 | 0.33 | 0.30 | −0.27 | 1.00 | |

| 10 Achievement (15) | 0.30 | −0.25 | −0.09 | −0.02 | 0.27 | 0.32 | 0.20 | −0.23 | 0.64 | 1.00 |

| 11 Behavior (G1) | −0.08 | 0.06 | 0.05 | −0.02 | −0.07 | −0.30 | −0.08 | 0.05 | −0.09 | −0.11 |

| 12 Behavior (15) | −0.06 | 0.08 | 0.01 | −0.04 | −0.04 | −0.23 | −0.06 | 0.06 | −0.11 | −0.13 |

| Demographic Controls | ||||||||||

| 13 Male | −0.05 | 0.06 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.05 | −0.20 | −0.01 | 0.23 | −0.01 | 0.05 |

| 14 Black | −0.25 | 0.21 | 0.07 | 0.05 | −0.24 | −0.16 | −0.12 | 0.20 | −0.29 | −0.33 |

| 15 Hispanic | −0.03 | −0.00 | 0.06 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.04 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.05 | −0.03 |

| 16 Other | −0.04 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.04 | −0.05 | −0.00 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| 17 Age | 0.03 | −0.04 | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.06 | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.05 |

| 18 Log of Income | 0.30 | −0.26 | −0.08 | −0.03 | 0.27 | 0.26 | 0.19 | −0.19 | 0.37 | 0.40 |

| 19 Mother’s Age | 0.20 | −0.18 | −0.05 | −0.00 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.12 | −0.14 | 0.22 | 0.32 |

| 20 Mother’s Ed (yrs) | 0.25 | −0.19 | −0.09 | −0.04 | 0.24 | 0.27 | 0.16 | −0.20 | 0.35 | 0.42 |

| 21 Mother PPVT | 0.28 | −0.22 | −0.09 | −0.08 | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.12 | −0.18 | 0.35 | 0.48 |

| 22 Site 1 | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.06 | −0.06 | −0.06 | 0.06 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.14 |

| 23 Site 2 | 0.00 | −0.06 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.06 | 0.10 |

| 24 Site 3 | 0.07 | −0.05 | −0.03 | −0.02 | 0.07 | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.09 | −0.04 | −0.08 |

| 25 Site 4 | −0.00 | 0.02 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.00 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.09 | −0.02 | 0.05 |

| 26 Site 5 | −0.06 | 0.02 | 0.06 | −0.00 | −0.06 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.01 | −0.02 | −0.05 |

| 27 Site 6 | 0.03 | −0.01 | −0.04 | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.04 | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.09 |

| 28 Site 7 | −0.05 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.04 | −0.02 | −0.10 | 0.12 | −0.05 | 0.02 |

| 29 Site 8 | 0.06 | 0.00 | −0.05 | −0.09 | 0.09 | 0.10 | −0.00 | −0.08 | −0.01 | 0.05 |

| 30 Site 9 | −0.04 | −0.00 | 0.04 | 0.04 | −0.06 | −0.07 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.02 |

| 31 Birthweight (g’s) | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.06 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.01 | 0.11 | 0.10 |

| 32 Bracken | 0.28 | −0.22 | −0.10 | −0.04 | 0.26 | 0.32 | 0.26 | −0.29 | 0.54 | 0.50 |

| 33 Bayley | 0.34 | −0.27 | −0.08 | −0.06 | 0.31 | 0.29 | 0.24 | −0.24 | 0.42 | 0.39 |

| 34 Temperament | −0.08 | 0.11 | 0.00 | −0.02 | −0.06 | −0.14 | −0.04 | 0.08 | −0.11 | −0.12 |

| H.O.M.E. Controls | ||||||||||

| 35 Learn. Mater. | 0.29 | −0.23 | −0.11 | −0.02 | 0.27 | 0.31 | 0.15 | −0.23 | 0.38 | 0.40 |

| 36 Lang. Stim. | 0.21 | −0.18 | −0.05 | −0.04 | 0.20 | 0.17 | 0.08 | −0.14 | 0.25 | 0.21 |

| 37 Phys. Env. | 0.20 | −0.13 | −0.13 | 0.02 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.13 | −0.12 | 0.23 | 0.21 |

| 38 Responsivity | 0.19 | −0.13 | −0.08 | −0.05 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.14 | −0.12 | 0.19 | 0.17 |

| 39 Academ. Stim. | 0.21 | −0.17 | −0.06 | −0.01 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.05 | −0.15 | 0.23 | 0.20 |

| 40 Modeling | 0.17 | −0.11 | −0.06 | −0.05 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.10 | −0.07 | 0.23 | 0.25 |

| 41 Variety | 0.25 | −0.15 | −0.14 | −0.04 | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.12 | −0.21 | 0.28 | 0.29 |

| 42 Acceptance | 0.12 | −0.07 | −0.07 | −0.04 | 0.13 | 0.21 | 0.13 | −0.17 | 0.16 | 0.19 |

| 43 Respons. Emp. | 0.20 | −0.14 | −0.08 | −0.05 | 0.20 | 0.16 | 0.12 | −0.10 | 0.20 | 0.16 |

| 54-month Controls | ||||||||||

| 44 Letter Word (54) | 0.28 | −0.22 | −0.09 | −0.03 | 0.25 | 0.29 | 0.25 | −0.24 | 0.60 | 0.49 |

| 45 App. Prob. (54) | 0.37 | −0.28 | −0.16 | −0.01 | 0.33 | 0.35 | 0.32 | −0.32 | 0.62 | 0.56 |

| 46 Pic. Vocab. (54) | 0.28 | −0.21 | −0.08 | −0.09 | 0.28 | 0.25 | 0.22 | −0.18 | 0.42 | 0.50 |

| 47 Mem. Sent. (54) | 0.29 | −0.25 | −0.09 | −0.02 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 0.22 | −0.21 | 0.42 | 0.43 |

| 48 Inc. Words (54) | 0.23 | −0.17 | −0.08 | −0.06 | 0.22 | 0.15 | 0.19 | −0.17 | 0.39 | 0.34 |

| 49 Internalizing (54) | −0.04 | 0.04 | 0.02 | −0.00 | −0.04 | −0.17 | −0.05 | 0.08 | −0.07 | −0.08 |

| 50 Externalizing (54) | −0.10 | 0.07 | 0.07 | −0.02 | −0.09 | −0.39 | −0.07 | 0.09 | −0.10 | −0.12 |

|

| ||||||||||

| PANEL 2 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 11 Behavior (G1) | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 12 Behavior (15) | 0.55 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Demographic Controls | ||||||||||

| 13 Male | −0.00 | −0.04 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 14 Black | 0.06 | 0.00 | −0.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 15 Hispanic | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.03 | −0.08 | 1.00 | |||||

| 16 Other | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.03 | −0.07 | −0.05 | 1.00 | ||||

| 17 Age | 0.03 | 0.04 | −0.00 | 0.03 | 0.01 | −0.04 | 1.00 | |||

| 18 Log of Income | −0.16 | −0.17 | −0.02 | −0.36 | −0.08 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 1.00 | ||

| 19 Mother’s Age | −0.18 | −0.21 | −0.04 | −0.28 | −0.10 | −0.04 | −0.04 | 0.54 | 1.00 | |

| 20 Mother’s Ed (yrs) | −0.13 | −0.17 | −0.04 | −0.22 | −0.11 | −0.03 | −0.00 | 0.61 | 0.52 | 1.00 |

| 21 Mother PPVT | −0.10 | −0.07 | −0.01 | −0.37 | −0.11 | −0.09 | −0.03 | 0.49 | 0.46 | 0.57 |

| 22 Site 1 | 0.09 | 0.07 | −0.00 | 0.11 | −0.07 | −0.07 | −0.03 | −0.09 | −0.09 | −0.06 |

| 23 Site 2 | −0.06 | −0.07 | 0.00 | −0.11 | 0.23 | −0.01 | −0.18 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.02 |

| 24 Site 3 | 0.04 | 0.02 | −0.02 | −0.02 | 0.08 | −0.03 | 0.10 | −0.07 | −0.05 | 0.02 |

| 25 Site 4 | −0.07 | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.05 | −0.04 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.07 | −0.04 |

| 26 Site 5 | −0.02 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.13 | −0.06 | −0.02 | 0.22 | −0.05 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| 27 Site 6 | −0.07 | −0.08 | −0.02 | 0.11 | −0.06 | −0.01 | −0.10 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.13 |

| 28 Site 7 | −0.02 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.14 | −0.09 | −0.07 | −0.08 |

| 29 Site 8 | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.00 | −0.05 | 0.00 | 0.11 | −0.19 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| 30 Site 9 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.01 | −0.05 | −0.06 | −0.05 | 0.04 | −0.06 | −0.08 | −0.12 |

| 31 Birthweight (g’s) | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.12 | −0.14 | 0.04 | −0.07 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.07 |

| 32 Bracken | −0.09 | −0.10 | −0.15 | −0.32 | −0.07 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.45 | 0.32 | 0.42 |

| 33 Bayley | −0.08 | −0.13 | −0.17 | −0.32 | −0.08 | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.40 | 0.23 | 0.36 |

| 34 Temperament | 0.12 | 0.15 | −0.04 | 0.17 | −0.01 | 0.05 | −0.01 | −0.19 | −0.19 | −0.13 |

| H.O.M.E. Controls | ||||||||||

| 35 Learn. Mater. | −0.10 | −0.11 | −0.05 | −0.39 | −0.12 | −0.08 | 0.03 | 0.49 | 0.35 | 0.48 |

| 36 Lang. Stim. | −0.01 | −0.06 | −0.03 | −0.11 | −0.12 | −0.11 | 0.01 | 0.27 | 0.12 | 0.24 |

| 37 Phys. Env. | −0.09 | −0.08 | 0.01 | −0.24 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.28 | 0.18 | 0.23 |

| 38 Responsivity | −0.09 | −0.07 | −0.02 | −0.22 | −0.06 | −0.07 | −0.09 | 0.32 | 0.26 | 0.28 |

| 39 Academ. Stim. | 0.00 | −0.01 | −0.03 | −0.17 | −0.09 | −0.04 | 0.01 | 0.24 | 0.12 | 0.25 |

| 40 Modeling | −0.07 | −0.04 | −0.05 | −0.15 | −0.06 | −0.06 | −0.05 | 0.31 | 0.23 | 0.33 |

| 41 Variety | −0.10 | −0.07 | −0.03 | −0.27 | −0.09 | −0.05 | 0.01 | 0.41 | 0.27 | 0.39 |

| 42 Acceptance | −0.16 | −0.14 | −0.05 | −0.10 | −0.01 | 0.00 | −0.04 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.24 |

| 43 Respons. Emp. | −0.06 | −0.05 | −0.02 | −0.18 | −0.06 | −0.04 | −0.06 | 0.31 | 0.20 | 0.26 |

| 54-month Controls | ||||||||||

| 44 Letter Word (54) | −0.07 | −0.07 | −0.10 | −0.20 | −0.08 | 0.05 | −0.01 | 0.38 | 0.19 | 0.38 |

| 45 App. Prob. (54) | −0.04 | −0.12 | −0.10 | −0.32 | −0.07 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.42 | 0.28 | 0.40 |

| 46 Pic. Vocab. (54) | −0.09 | −0.04 | 0.10 | −0.33 | −0.10 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.42 | 0.32 | 0.40 |

| 47 Mem. Sent. (54) | −0.11 | −0.09 | −0.04 | −0.18 | −0.11 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.29 | 0.21 | 0.28 |

| 48 Inc. Words (54) | −0.05 | −0.12 | −0.00 | −0.18 | −0.10 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.24 | 0.18 | 0.24 |

| 49 Internalizing (54) | 0.53 | 0.38 | 0.03 | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.09 | −0.06 | −0.09 | −0.10 |

| 50 Externalizing (54) | 0.63 | 0.47 | −0.08 | 0.05 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.12 | −0.13 | −0.13 |

|

| ||||||||||

| PANEL 3 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 21 Mother PPVT | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 22 Site 1 | −0.10 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 23 Site 2 | 0.04 | −0.10 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 24 Site 3 | −0.02 | −0.10 | −0.11 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 25 Site 4 | −0.02 | −0.10 | −0.11 | −0.11 | 1.00 | |||||

| 26 Site 5 | −0.01 | −0.11 | −0.11 | −0.11 | −0.11 | 1.00 | ||||

| 27 Site 6 | 0.10 | −0.10 | −0.10 | −0.11 | −0.10 | −0.11 | 1.00 | |||

| 28 Site 7 | −0.01 | −0.11 | −0.11 | −0.11 | −0.11 | −0.12 | −0.11 | 1.00 | ||

| 29 Site 8 | 0.14 | −0.11 | −0.11 | −0.11 | −0.11 | −0.12 | −0.11 | −0.12 | 1.00 | |

| 30 Site 9 | −0.11 | −0.11 | −0.11 | −0.11 | −0.11 | −0.12 | −0.11 | −0.12 | −0.12 | 1.00 |

| 31 Birthweight (g’s) | 0.13 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.06 | 0.04 | −0.02 | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| 32 Bracken | 0.40 | −0.05 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.05 | −0.14 | 0.05 | −0.03 |

| 33 Bayley | 0.34 | −0.05 | 0.10 | −0.02 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.18 | −0.06 | −0.01 |

| 34 Temperament | −0.19 | 0.06 | −0.08 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| H.O.M.E. Controls | ||||||||||

| 35 Learn. Mater. | 0.47 | −0.06 | −0.09 | −0.01 | −0.04 | −0.01 | 0.08 | −0.04 | 0.00 | 0.05 |

| 36 Lang. Stim. | 0.24 | 0.06 | −0.16 | −0.15 | −0.20 | 0.02 | 0.18 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.09 |

| 37 Phys. Env. | 0.19 | −0.07 | −0.06 | −0.05 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.02 | −0.25 | −0.05 | 0.19 |

| 38 Responsivity | 0.27 | −0.11 | −0.01 | −0.06 | −0.02 | −0.11 | 0.30 | −0.30 | 0.12 | 0.06 |

| 39 Academ. Stim. | 0.24 | −0.01 | −0.18 | −0.06 | −0.07 | 0.04 | 0.12 | −0.11 | 0.05 | 0.09 |

| 40 Modeling | 0.29 | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.09 | −0.08 | −0.00 | 0.15 | −0.08 | 0.03 | −0.06 |

| 41 Variety | 0.37 | 0.02 | −0.14 | −0.06 | −0.04 | −0.03 | 0.16 | −0.09 | 0.07 | 0.08 |

| 42 Acceptance | 0.20 | −0.10 | −0.00 | −0.06 | 0.01 | −0.04 | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.04 | −0.14 |

| 43 Respons. Emp. | 0.25 | 0.04 | −0.03 | −0.07 | −0.03 | −0.15 | 0.17 | −0.12 | 0.08 | 0.02 |

| 54-month Controls | ||||||||||

| 44 Letter Word (54) | 0.34 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.10 | −0.08 | 0.03 | −0.05 |

| 45 App. Prob. (54) | 0.43 | −0.08 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.07 | −0.02 | 0.09 | −0.08 | 0.04 | −0.03 |

| 46 Pic. Vocab. (54) | 0.48 | −0.12 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.07 | −0.01 | 0.05 | −0.04 | 0.10 | −0.03 |

| 47 Mem. Sent. (54) | 0.30 | −0.08 | −0.06 | −0.06 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.06 | −0.05 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| 48 Inc. Words (54) | 0.27 | −0.07 | −0.06 | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.00 | −0.05 | 0.13 |

| 49 Internalizing (54) | −0.10 | 0.01 | −0.04 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.05 | −0.05 | 0.01 | −0.02 | −0.03 |

| 50 Externalizing (54) | −0.11 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.06 | 0.01 |

|

| ||||||||||

| PANEL 4 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 39 | 40 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 31 Birthweight (g’s) | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 32 Bracken | 0.08 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 33 Bayley | 0.06 | 0.52 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 34 Temperament | −0.04 | −0.15 | −0.12 | 1.00 | ||||||

| H.O.M.E. Controls | ||||||||||

| 35 Learn. Mater. | 0.07 | 0.47 | 0.43 | −0.12 | 1.00 | |||||

| 36 Lang. Stim. | 0.10 | 0.28 | 0.23 | −0.04 | 0.51 | 1.00 | ||||

| 37 Phys. Env. | 0.01 | 0.25 | 0.24 | −0.08 | 0.41 | 0.28 | 1.00 | |||

| 38 Responsivity | 0.08 | 0.31 | 0.25 | −0.11 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.26 | 1.00 | ||

| 39 Academ. Stim. | 0.08 | 0.33 | 0.26 | −0.02 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.31 | 0.33 | 1.00 | |

| 40 Modeling | 0.07 | 0.24 | 0.24 | −0.10 | 0.37 | 0.31 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 1.00 |

| 41 Variety | 0.04 | 0.36 | 0.37 | −0.09 | 0.56 | 0.41 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.43 | 0.35 |

| 42 Acceptance | 0.05 | 0.22 | 0.19 | −0.05 | 0.28 | 0.20 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.14 | 0.32 |

| 43 Respons. Emp. | 0.04 | 0.24 | 0.19 | −0.12 | 0.35 | 0.48 | 0.26 | 0.77 | 0.29 | 0.27 |

| 54-month Controls | ||||||||||

| 44 Letter Word (54) | 0.07 | 0.61 | 0.40 | −0.08 | 0.40 | 0.29 | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.34 | 0.23 |

| 45 App. Prob. (54) | 0.09 | 0.57 | 0.56 | −0.13 | 0.43 | 0.24 | 0.27 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.18 |

| 46 Pic. Vocab. (54) | 0.12 | 0.46 | 0.44 | −0.12 | 0.43 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.21 |

| 47 Mem. Sent. (54) | 0.08 | 0.39 | 0.43 | −0.08 | 0.31 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.22 | 0.14 |

| 48 Inc. Words (54) | 0.09 | 0.30 | 0.36 | −0.10 | 0.30 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.16 | 0.22 | 0.14 |

| 49 Internalizing (54) | 0.04 | −0.03 | −0.03 | 0.14 | −0.07 | −0.04 | −0.02 | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.04 |

| 50 Externalizing (54) | 0.04 | −0.11 | −0.05 | 0.12 | −0.12 | −0.06 | −0.09 | −0.10 | −0.07 | −0.11 |

|

| ||||||||||

| PANEL 5 | 41 | 42 | 43 | 44 | 45 | 46 | 47 | 48 | 49 | 50 |

|

| ||||||||||

| 41 Variety | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 42 Acceptance | 0.23 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 43 Respons. Emp. | 0.28 | 0.23 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 54-month Controls | ||||||||||

| 44 Letter Word (54) | 0.32 | 0.19 | 0.21 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 45 App. Prob. (54) | 0.31 | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.58 | 1.00 | |||||

| 46 Pic. Vocab. (54) | 0.38 | 0.16 | 0.22 | 0.46 | 0.52 | 1.00 | ||||

| 47 Mem. Sent. (54) | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.42 | 0.47 | 0.46 | 1.00 | |||

| 48 Inc. Words (54) | 0.27 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.36 | 0.45 | 0.37 | 0.49 | 1.00 | ||

| 49 Internalizing (54) | −0.07 | −0.07 | −0.06 | −0.01 | −0.04 | −0.08 | −0.06 | −0.04 | 1.00 | |

| 50 Externalizing (54) | −0.11 | −0.14 | −0.11 | −0.04 | −0.05 | −0.09 | −0.10 | −0.05 | 0.58 | 1.00 |

Note. n=918. All non-missing cases for each pairwise correlation were included. Tables 2 and 3 include the full variable names and labels. The supplementary material presents correlations for all variables shown separately by mother’s education. The “G1” abbreviation stands for “grade 1,” “15” stands for “age 15,” and “54” stands for 54 months.

In the supplementary file, we further assessed to what extent self -control and attention could account for the associations between gratification delay and later achievement. In Table S3, we included the 54-months measures of attention and impulse control taken from the CPT in the Table 4 models and found that inclusion of the CPT measures accounted for only 21–27% of the effect for the “> 7 minute group”. In Table S4, we ran a parallel analysis using the Duckworth et al. (2013) index of self-control, and again we found that coefficients were hardly reduced when the self-control index was included. The small change in the coefficient for the gratification delay measure between models that did and did not include indicators of attention, impulsivity and self-control raises further questions regarding what constructs are measured by the Marshmallow Test.

Alternative outcome measures

Returning to our focal sample of children with mothers who had not completed college, we were surprised to see the lack of significant associations between our gratification-delay measure and the behavioral measures at first grade and age 15. We also tested models that used alternative indicators of behavior assessed at age 15, including measures of risky behavior from youth self-reports and assessments of impulse control. Surprisingly, we still found virtually no associations between gratification delay and behavior across any of these alternative measures (Tables S5 through S7 in the supplementary material). Furthermore, because we relied on aggregated measures of achievement and behavior, we also tested separate models for math, reading, externalizing behaviors, and internalizing behaviors (Table S8). Results indicated that the achievement associations were similar for both the math and reading measures, and we still found no statistically significant effects on either measure of problem behaviors.

Discussion

We attempted to extend the famous findings of Mischel and Shoda (Mischel et al., 1988; Mischel et al., 1989; Shoda et al., 1990) by examining associations between early gratification delay and adolescent outcomes in a more diverse sample of children and with more sophisticated statistical models. As with the earlier studies, we found statistically significant, although smaller, bivariate associations between early delay ability and later achievement. But we also found that these associations were highly sensitive to the inclusion of controls. Moreover, we failed to find even bivariate associations between age-54-months delay and a host of age-15 behavioral outcomes, which was remarkable given the stability in self -control measures found in other studies (e.g., Moffitt et al., 2011).

It surprised us that for the children of non-degreed mothers, most of the achievement boost for early delay ability was gained by waiting a mere 20 seconds. Shoda et al. (1990) argued that the relationship between gratification delay and academic achievement might be driven by the ability to generate useful metacognitive strategies that will influence self-regulation throughout one’s life. Such strategies are unlikely to have played much of a role in a child’s ability to wait for only 20 seconds. Instead, our findings suggest that impulse control may be a key mechanism, although post-hoc inclusion of an explicit measure of impulse control explained some but certainly not most of the gratification delay effect.

These results provide further questions regarding what the Marshmallow Test might measure, and how it relates to the umbrella construct of self-control. We observed that gratification delay was strongly correlated with concurrent measures of cognitive ability, and controlling for a composite measure of self-control explained only about 25% of our reported effects on achievement. These results suggest that the Marshmallow Test may capture something rather distinct from self-control. Indeed, Duckworth and colleagues (2013) also investigated the relations between gratification delay, self-control and intelligence using the data employed here, and found that both self-control and intelligence mediated the relation between early delay ability and later outcomes. Our results further suggest that simply viewing gratification delay as a component of self-control may oversimplify how gratification delay operates in young children.

When considering how our results might inform intervention development, recall that models with controls for concurrent measures of cognitive skills and behavior reduced the association between gratification delay and age-15 achievement to nearly 0. This implies that an intervention that altered a child’s ability to delay, but failed to change more general cognitive and behavioral capacities, would likely have limited effects on later outcomes. If intervention developers hope to generate program impacts that replicate the long-term Marshmallow Test findings, targeting the broader cognitive and behavioral abilities related to gratification delay might prove more fruitful.

Indeed, Mischel and Shoda’s original results (Shoda et al., 1990) supported similar conclusions. Recall that they reported long-run correlations between gratification delay and later outcomes only for children who were not provided with strategies for delaying longer. That the prediction was strong only in trials that relied on natural variation in children’s ability to delay suggests that unobserved factors underlying children’s delay ability may have driven the long-run correlations. Our results support this interpretation.

Our study is not without weaknesses. The 7-minute ceiling was limiting, although our non-linear models indicated that it was unlikely to affect conclusions drawn for the lower-SES sample. For the higher-SES sample, the 7-minute ceiling prevented a direct replication of Mischel and Shoda’s original work (e.g., Shoda et al., 1990), as a substantial majority of higher-SES children hit the ceiling. The lack of precision in our higher-SES results was unfortunate, though it should be noted that point estimates in fully-controlled models were often very small. At the very least, these results further suggest that bivariate associations between gratification delay and later outcomes probably contain substantial bias, even for more privileged children.