Abstract

The members of the Order Nidovirales share a similar genome organization with the nonstructural proteins encoded at the 5ʹ end and the structural genes at the 3ʹ end and express the 3ʹ genes from a nested set of 3′ co-terminal subgenomic messenger RNAs (sg mRNAs). Some but not all of the Nidoviruses, the sg mRNAs also have a common 5ʹ leader sequence acquired by a discontinuous transcription mechanism regulated by multiple 3ʹ transcription regulatory sequences (TRS) and the 5ʹ leader TRS. Initial studies detected a single major body TRS for each 3ʹ genes with a few alternative functional TRSs reported. The recent application of advanced techniques, such as next generation sequencing and ribosomal profiling, in studies of arteriviruses and coronaviruses has revealed an expanded sg mRNA transcriptome and coding capacity.

Keywords: nidovirus, coronavirus, arterivirus, transcription regulatory sequences, subgenomic mRNAs, next generation sequencing, discontinuous RNA synthesis, leader-body junction sequences

Subgenomic mRNA production by members of the Order Nidovirales

The order Nidovirales consists of enveloped, single-stranded positive-sense RNA viruses that are currently classified into four virus families, Coronaviridae, Arteriviridae, Mesoniviridae, and Roniviridae (Gorbalenya et al., 2006). (Zirkel et al., 2013). Due to the large number of new Nidoviruses recently identified by next generation sequencing (NGS) efforts, additional revisions to the Nidovirales taxonomy classification are currently being discussed. Among the four families, the Coronaviridae and Arteriviridae mainly infect mammalian hosts while the Mesoniviridae infect insects and the Roniviridae infect crustaceans. Although nidovirus genomes range in size from ~12 to ~30 kb, they share similarities in gene organization (two large, overlapping, nonstructural protein ORFs at the 5ʹ end and structural protein ORFs at the 3ʹ end) and produce a nested set of 3′ co-terminal subgenomic messenger RNAs (sg mRNA) in infected cells (Cong et al., 2017). Among the arteriviruses, simian hemorrhagic fever virus (SHFV) has the largest genome (15.7 kb) compared to those of equine arteritis virus (EAV), porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) and lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus (LDV) (Snijder et al., 2013).

In an early sucrose gradient sedimentation analysis of coronavirus murine hepatitis virus (MHV) viral RNA extracted from late harvest, sucrose gradient purified virus detected several smaller, polyadenylated RNA fragments in addition to the full length genomic RNA (Lai and Stohlman, 1978). These RNAs were initially thought to be genomic degradation products but subsequent studies identified them as members of a nested set of six 3′-coterminal, subgenomic mRNAs that also possessed a 5′ leader sequence, identical to the 5′ end of the genome (Lai et al., 1981). Equine arthritis virus (EAV), the prototype of the family Arteriviridae, was later found to also produce six sg mRNAs with co-terminal 3′ ends and a common 5′ leader sequence (de Vries et al., 1990b; van Berlo et al., 1982; van Berlo et al., 1986). A subsequent study showed that most coronavirions contain a single copy of genome RNA but that some also contain a sg mRNA, suggesting that sg mRNAs are inefficiently packaged (Zhao et al., 1993).

The synthesis of sg mRNAs during an infection is not exclusive to the Nidovirales. However, the use of a discontinuous transcription mechanism and the resulting 5′-3′ co-terminal nested sg mRNAs are unique features of the coronaviruses and arteriviruses (Miller and Koev, 2000). Two models were proposed to explain the acquisition of the 5′ leader sequence by coronavirus sg mRNAs. The initial model, termed “Leader-primed Transcription Model” (Lai, 1986) suggested that the discontinuous transcription step occurred during the synthesis of plus strand RNA with a single, full-length, minus strand anti-genome RNA serving as the template for synthesis of nascent genomic and sg mRNAs. It was hypothesized that short leader sequences synthesized from the 3′ end of the anti-genome by the viral RNA dependent RNA polymerase served as primers to initiate RNA synthesis at multiple complementary intergenic sequences (internal promoters) located within the 5′ region of the anti-genomic template. Elongation from these primers produced a set of 5′−3′ co-terminal sg mRNAs(Lai, 1986)

An alternate model later proposed by (Sawicki and Sawicki, 1990) suggested that the discontinuous transcription step occurred during the synthesis of minus strand RNA from the genome. The discovery of multiple subgenomic length minus strand RNAs as well as of multiple sg RNA replicative intermediates in cells infected with the coronavirus, porcine transmissible gastroenteritis virus (PTGV) or MHV provided compelling evidence supporting the “Discontinuous Minus Strand Synthesis Model” (Sawicki and Sawicki, 1990; Sethna et al., 1989). According to this model, full-length and subgenomic length minus strand RNAs are first synthesized from genomic RNA and then serve as templates for genomic and sg mRNA synthesis, respectively. Subgenomic replicative intermediate and replicative form viral RNAs were subsequently identified in cells infected with the arterivirus EAV indicating that the same mechanism of sg RNA production is also used by members of the family Arteriviridae (den Boon et al., 1996). Body transcription regulatory sequences (TRS) in the 3ʹ region of the genome RNA were subsequently identified at the termination sites for sg RNAs during minus strand RNA synthesis and were identified by amplifying and sequencing the junction regions consisting of a 3ʹ sequence fused to the 5ʹ leader for individual sg mRNAs. In the arterivirus EAV genome, the single 5′ leader TRS was shown to form a stem-loop structure with a 6 nt core sequence similar to the body TRS core sequences located on the loop and two 10–15 nt flanking sequences forming the stem (Van Den Born et al., 2004; van den Born et al., 2005). Whether the leader region of other arteriviruses form similar structures is not known. However, the leader TRS region of multiple coronavirus genomes has been shown to be located in the loop of a short stem (Masters and Perlman, 2013) and a cis-acting 5′ proximal enhancer element was reported to be located in the leader region of MHV (Wang and Zhang, 2000). The results of a study using a transfected in vitro synthesized sg mRNA indicated that long sg mRNAs which contain multiple TRSs could also function as templates for prematurely terminated minus strand RNAs (Wu and Brian, 2010).

The subsequent identification of multiple 5ʹ−3ʹ co-terminal sg mRNAs for additional coronavirus and arteriviruses led to the adoption of the view that all Nidoviruses utilize the same discontinuous minus strand transcription strategy to produce a nested set of 3′ co-terminal sg mRNAs with a common 5′ leader in infected cells. However, data from studies on equine torovirus (EToV) (previously called Berne virus) and gill-associated virus (GAV), showed that not all nidoviruses produce 3′ co-terminal sg mRNAs with a common 5′ leader (Pasternak et al., 2006). EToV, produces a 3′ nested set of four sg mRNAs, three of which (RNA 3, 4, and 5) do not possess a 5′ leader sequence while RNA 2, the shortest EToV sg mRNAs, has a short 5′ leader sequence (Smits et al., 2005; van Vliet et al., 2002). These findings suggest that EToV uses both discontinuous and non-discontinuous transcription mechanisms to produce its sg mRNAs. Recent studies on GAV, a crustacean virus in the family Roniviridae, identified two 3′ co-terminal sg mRNAs of different lengths that are initiated from the same intergenic sequence site. Neither of these sg mRNAs possesses a 5′ leader sequence (Cowley et al., 2002).

Identification of functional alternative TRSs for known structural proteins

TRSs for individual coronavirus and arterivirus sg mRNAs were initially identified by RT-PCR amplification and sequencing of leader-body junction regions of the sg mRNAs produced in infected cells. With this technique, typically a single major TRS was identified for each sg mRNA and it was assumed that the majority of the sg mRNA generation for each structural gene was regulated by the major TRS. However, two alternative body TRSs (also known as non-canonical TRSs) for GP3 were identified for EAV by amplification, cloning and sequencing of sg mRNA leader-body junctions (den Boon et al., 1996). A later EAV study not only confirmed the use of alternative TRSs for GP3, but also identified one alternative TRS for GP4 and one for GP5 (Pasternak et al., 2000). One alternative TRS was also identified for GP4 and one for N of the PRRSV strain VR2332 (Nelsen et al., 1999). A different alternative TRS for N was later identified in the PRRSV strain tw91(Lin et al., 2002). Mutation of the major TRS for GP4 in the EAV genome showed that the sg mRNAs produced from alternative TRSs although less abundant were still sufficient to generate infectious progeny virus but at a reduced titer, suggesting that alternative body TRSs can function as “back-ups” when the major TRS is not functional (Pasternak et al., 2000). Studies on coronaviruses have also shown alternative body TRSs can function to produce sg mRNAs when the major body TRS of a 3ʹ ORF is mutated (Ozdarendeli et al., 2001; Schelle et al., 2005; Zuniga et al., 2004).

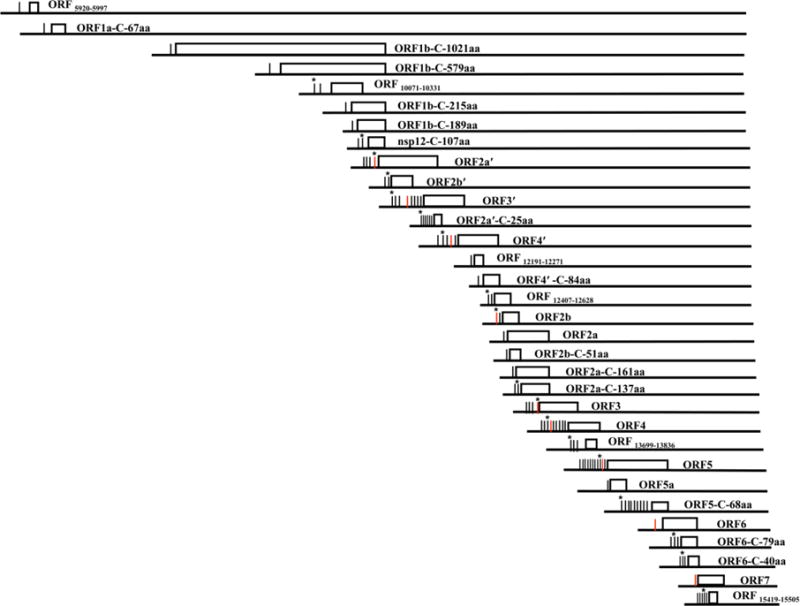

Although amplification, cloning and sequencing of sg mRNA leader-body junctions is an effective means of identifying TRSs for abundant sg mRNAs, it was less effective in identifying the TRSs for low abundant sg mRNAs due to the difficulty of detecting low abundant RT-PCR products after electrophoresis on gels or to the limited number of clones screened. Although only one alternative EAV TRS was identified for GP4 and one for GP5, when both the known major and alternative TRSs for GP4 or GP5 were mutated, the mutant virus produced was still infectious and able to spread to neighboring cells, suggesting the possible existence of additional unidentified functional alternative TRSs for each of these genes (Pasternak et al., 2000). Because NGS detects all sg mRNAs produced in RNA samples harvested from infected cells, including those at very low abundance, it can be used to identify all of the functional TRSs in a nidovirus genome and assess their relative abundances. The first NGS analysis of an arterivirus transcriptome identified a total of 96 functional body TRSs in the SHFV genome. Most of these were functional alternative TRSs for SHFV structural proteins, with 8 identified for GP4 and 10 for GP5. (Di et al., 2017)(Fig. 1). A mass spectrometry analysis showed that for the majority of the SHFV structural proteins, the relative protein level for each ORF correlated well with the combined sg mRNA abundance from the major TRS and all of the alternative TRSs. These results suggested that instead of just being “back-ups” for the major TRS, the alternative body TRSs are an integral part of the viral expression strategy and essential for the production of the optimal amount of each viral protein (Di et al., 2017). Because similar NGS analyses have not yet been performed for other arteriviruses it is currently not known whether the SHFV genome is unique in having a high number of alternative TRSs for some of its ORFs or whether this is also a characteristic feature of other arteriviruses.

Figure 1. Diagram of the SHFV transcriptome.

The ORFs are represented by white boxes. Functional TRSs identified are indicated by vertical lines to the left each ORF. Red vertical lines represent the nine major SHFV body TRSs published prior to the recent SHFV NGS study. For ORFs with multiple functional TRSs, an asterisk indicates the TRS that produces the highest abundance of sg mRNA for that ORF. (Published in Di et al. 2017. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114(42):E8895–E8904).

Identification of sg mRNAs for in-frame, C-terminal proteins

In addition to the alternative TRSs for PRRSV GP4 and N, a TRS located downstream of the AUG start codon for GP5 was identified for the PRRSV strain VR2332 genome (Nelsen et al., 1999) Compared to sg mRNA5, this TRS generated a shorter sg mRNA (sg mRNA5-1) that appears to encode an in-frame, C-terminal peptide of GP5 (de Vries et al., 2000). Although not characterized, a shorter sg mRNA band migrating between sg mRNA5 and sg mRNA6 was evident on multiple previously published EAV Northern blots (Pasternak et al., 2000; Pasternak et al., 2001; van Marle et al., 1999a). A sg mRNA band migrating between sg mRNA5 and sg mRNA6 was also detected on SHFV Northern blots (Di et al., 2017; Vatter et al., 2014). Amplification, cloning and sequencing of the leader-body junctions of these sg mRNAs revealed that this band was composed of seven different sg mRNAs of similar sizes that were generated from seven unique body TRSs located between TRS5 and TRS6. All seven of these sg mRNAs encode the same in-frame, C-terminal peptide of GP5 (Di et al., 2017)(Fig. 1). sg mRNAs encoding an in-frame, C-terminal peptide for the SHFV structural proteins, GP2ʹ, GP4ʹ, GP2 and M, were also identified in infected cells (Di et al., 2017)(Fig.1). Two previous studies on the coronaviruses, severe acute respiratory syndrome virus and infectious bronchitis virus, identified a novel sg mRNA encoding an in-frame, C-terminal peptide of the virion spike protein (Bentley et al., 2013; Hussain et al., 2005). Similarly, both a previous study and a recent NGS and ribosome profiling study of the coronavirus MHV detected translation initiation at an internal AUG within the coronavirus MHV ORF5 (Irigoyen et al., 2016; Thiel and Siddell, 1994). Although both coronaviruses and arteriviruses appear to produce C-terminal proteins, the functions of these in-frame, C-terminal peptides of various viral structural proteins are currently not known. Mutagenesis of the AUGs of the SHFV C-terminal peptides in an infectious clone provided preliminary evidence for the functional relevance of the GP5 and M C-terminal peptides. Both mutant viruses displayed a reduced viral yield and plaque size in cell culture (Di et al., 2017).

Identification of sg mRNAs for alternative frame proteins

Knowledge of the coding capacity of arteriviruses and coronaviruses has expanded over the years with the discovery of additional ORFs. Arteriviruses were initially thought to encode three minor structural proteins, glycoprotein 2 (GP2), GP3 and GP4 and three major structural proteins GP5, membrane protein (M) and nucleocapsid (N) (Snijder et al., 1999). An early Northern blot analysis of SHFV sg mRNA production in infected MA104 cells identified six strong sg mRNA bands. Based on their sizes, these sg mRNAs were predicted to encode the six known arterivirus minor and major structural proteins (Zeng et al., 1995). An extra set of minor structural protein ORFs for GP2′, GP3′ and GP4ʹ was later shown to be encoded in the 3ʹ region of the SHFV genome (Smith et al., 1997). A subsequent sg mRNA junction region amplification, cloning and sequencing study identified body TRSs for GP2ʹ and GP4ʹ but not for GP3ʹ and it was proposed that GP3ʹ was also expressed from the sg mRNA encoding GP2ʹ (Godeny et al., 1998). A recent reanalysis of SHFV sg mRNAs by Northern blotting using a more sensitive 5′ leader probe detected ten sg mRNA bands including a sg mRNA3ʹ for GP3ʹ (Vatter et al., 2014). Additional structural protein ORFs, E and ORF5a, were later discovered in the genomes of EAV and PRRSV that were predicted to be expressed bicistronically from the sg mRNAs for GP2 and GP5, respectively (Firth et al., 2011; Johnson et al., 2011; Snijder et al., 1999). Bicistronic expression of the GP2ʹ and Eʹ proteins and for the E and GP2 proteins of SHFV was initially proposed. However, separate sg mRNAs for both Eʹ and GP2 were later identified in the NGS study of SHFV transcriptome (Di et al., 2017). Comparison of the relative sg mRNA and protein abundances suggested that the majority of E′ is expressed from the 5′ ORF of multiple monocistronic E′ sg mRNAs. In contrast, the abundance of the GP2 moncistronic sg mRNAs was much lower than the abundance of this protein suggesting that the majority of GP2 is translated as a second ORF from the E sg mRNAs. Monocistronic sg mRNAs have also been identified for some coronavirus proteins, such as the mouse hepatitis virus (MHV) E protein, that were initially thought to be expressed only bicistronically (O’Connor and Brian, 2000; Zhang and Liu, 2000).

An additional alternative frame ORF overlapping ORF5 (GP5) was identified in a PRRSV genome and shown to express a protein designated ORF5a (Firth et al., 2011; Johnson et al., 2011). A separate sg mRNA encoding ORF5a as the 5ʹ proximal ORF was not identified in that study but the NGS study of the SHFV transcriptome identified the sg mRNA for ORF5a at very low abundance (Di et al., 2017). However, a recent MassSpec analysis of purified SHFV detected the 5a protein. An early study on PRRSV found that four US PRRSV isolates, including VR2385 and ISU79, produced an additional sg mRNA3-1 that encodes an alternative frame ORF (ORF3-1) that overlaps ORF3 (GP3) (Meng et al., 1996). Neither protein production nor function have yet been confirmed for this protein. A recent bioinformatic study suggested the existence of a small ORF7a protein encoded in the +2 reading frame inside ORF7 (N) of type I and type II PRRSV genomes (Olasz et al., 2016). The recent SHFV NGS study identified five functional body TRSs that each generated sg mRNAs encoding ORF15419–15505 in the +2 reading frame located inside SHFV ORF7 (N) (Fig. 1)(Di et al., 2017). The SHFV NGS study also identified sg mRNAs encoding five additional alternative frame ORFs (Fig. 1). The predicted sizes of the proteins that would be translated from these alternative frame ORFs are 86aa, 25aa, 28aa, 73aa, 26aa, and 45aa. The 86 aa protein expressed from the largest of these alternative frame ORFs (ORF10071–10331) was detected by mass spectrometry in infected MA104 extracts (Di et al., 2017). The expected low abundance of these proteins and the technical challenges of detection of small proteins from gels by MassSpec may be the reason that they were not detected. Studies on coronaviruses have also identified alternative frame proteins such as an alternative ORF located inside the N gene that encodes an accessary protein (Fischer et al., 1997; Liu et al., 2014; Meier et al., 2006). A recent analysis of coronavirus MHV protein ORF translation by ribosome profiling and NGS detected the translation of multiple previously unidentified small alternative frame ORFs (Irigoyen et al., 2016). These MHV alternative frame ORFs were initiated from non-canonical start codons such as CUG, suggesting an even larger coding potential for Nidovirus genomes. The authors proposed that some of these small alternative frame ORFs may function as regulators of the translation of downstream ORFs in the same sg mRNA (Irigoyen et al., 2016). It is possible that some of the SHFV small C-terminal ORFs and small alternative frame ORFs may also function as regulators of downstream ORFs. Alternatively, increasing evidence from multiple host species suggests that small, functional proteins, some as short as 11 aa, are translated from in frame or alternative frame ORFs in mRNAs and are involved in regulating a variety of cellular processes (Landry et al., 2015; Pueyo et al., 2016). Three 18–22 nt small noncoding viral RNAs (svRNAs) were recently identified in SARS-CoV infected cells that were derived from the nsp3 (svRNA-nsp3.1 and -nsp3.2) and N (svRNA-N) genomic regions of SARS-CoV (Morales et al., 2017). Although similar in size to miRNAs, the generation of these RNAs was found to be RNase III, cell type, and host species independent. The functional relevance of one of these RNAs was indicated by the reduction in lung pathology and pro-inflammatory cytokine expression when svRNA-N was inhibited with an antagomir.

Identification of sg mRNA production from the genomic 5ʹ nonstructural region

Although functional body TRSs were thought to be located only in the 3′ structural protein region of Nidovirus genomes, a previous study on the arterivirus LDV identified a functional body TRS in the ORF1b region by amplifying, cloning and sequencing the leader-body junctions. This TRS generated a long sg mRNA encoding an in-frame, C-terminal portion of ORF1b (200 aa) but translation of this truncated ORF1b polyprotein was not confirmed (Chen et al., 1993). A study on the coronavirus MHV identified three functional body TRSs in ORF1a region by amplifying, cloning and sequencing the leader-body junctions (La Monica et al., 1992). The recent SHFV NGS study identified two functional body TRSs in ORF1a and eight in ORF1b that generated ten long sg mRNAs. Among these sg mRNAs, six encode different lengths of in-frame, C-terminal portions of ORF1b with the shortest one encoding only the C-terminus of nsp12 and the longest one encoding the C-terminus of nsp9 plus full-length nsp10, nsp11 and nsp12 (Fig. 1) (Di et al., 2017). ORF1b has been reported to be translated at a much lower efficiency (15–20%) than ORF1a due to the requirement of a −1 frameshift near the end of ORF1a for ORF1a/1b translation to occur (den Boon et al., 1991; Snijder et al., 2013). Analysis of SHFV protein production by mass spectrometry detected 3 times more nsp12 and 1.2 times more nsp11 than nsp8, which is encoded at the 3′ end of the ORF1a, suggesting that the long sg mRNAs produced from the TRSs in the ORF1b region provide additional sources of nsp10, nsp11 and especially nsp12. However, the relative half-lives of the individual SHFV nonstructural proteins are not known and could also affect the relative abundances of these proteins. Previous studies on PRRSV also detected the production of atypical sg mRNAs (designated heteroclite sg mRNAs) in the ORF1a region. These sg mRNAs differ from typical sg mRNAs in having their 3ʹ genomic sequences fused to various sites within ORF1a, rather than to a common 5ʹ leader(Yuan et al., 2000; Yuan et al., 2004). However, production of these heteroclite sg mRNAs has not been reported for other arteriviruses.

Characteristics of sg mRNAs regulation

Northern blotting studies of nidovirus infected cell extracts suggested that although the relative abundances of the detected individual sg mRNAs differed, they were consistent during infection (Di et al., 2017). The recent SHFV NGS analysis allowed calculation of the relative abundance of each viral sg mRNA. The data indicated that the relative sg mRNA abundance produced from each identified body TRS, regardless of whether it is a major or alternative TRS, was consistent at early and later times after infection in both primary macrophages and MA104 cells, suggesting that sg mRNA production is primarily regulated by viral not cellular factors (Di et al., 2017).

Two previous PRRSV leader-body junction sequence analysis studies identified heterogeneous junction sequences (Lin et al., 2002; Meulenberg et al., 1993). The junction sequence of a sg mRNA is determined by the location within the particular body TRS where the polymerase disassociates and the location within the leader TRS where the nascent minus strand anneals. The SHFV NGS data indicated that about one-third of the total body TRSs identified, including both major and alternative TRSs, produced sg mRNAs with two or three heterogeneous junction sequences (Di et al., 2017). Heterogeneity in sg mRNA junction sequences produced from the same body TRS has also been detected for coronaviruses by either amplification, cloning and sequencing the junction sequences or by NGS (Irigoyen et al., 2016; Makino et al., 1988; Schaad and Baric, 1993). The observed heterogeneity in sg mRNA junction sequences suggests that the fusion position between leader and body TRSs can vary but the observation that the abundances of the sg mRNAs with each of the alternative junction sequences is consistent suggests that this variation is controlled by the characteristics of the viral elements regulating discontinuous transcription at these sites.

Possible modes of sg mRNA regulation

The means by which discontinuous RNA synthesis is regulated by Nidoviruses is not well understood. Previous studies on both coronaviruses and arteriviruses have suggested that shorter sg mRNAs generated from TRSs located closer to the 3ʹ end of the genome are usually in higher abundance (de Vries et al., 1990a; Krishnan et al., 1996; Pasternak et al., 2004). Studies of two closely located body TRSs showed that the downstream TRS could suppress the function of the upstream one (Joo and Makino, 1995; Pasternak et al., 2004). However, data from the SHFV NGS study clearly showed that there is not a linear correlation between the distance of a TRS from the 3ʹ end of the genome and the corresponding sg mRNA abundance. Instead, multiple genomic regions containing TRSs of high transcription activity were flanked by regions containing TRSs of low transcription activity (Di et al., 2017). Previous studies also observed that when mutations in a body TRS increased the duplex stability between the leader and body TRS sequences, the corresponding sg mRNA abundance usually increased with a few exceptions (Pasternak et al., 2001, 2003; Sola et al., 2005; Zuniga et al., 2004). However, some sequence motifs were found in the viral genomes with 100% homology to the leader TRS core sequence that were not utilized as TRSs, suggesting that duplex stability is necessary but not sufficient for regulating discontinuous RNA synthesis. The duplex stability between the leader TRS and each of the seven closely located functional body TRSs for SHFV ORF5C was calculated and found not to show a linear correlation with the corresponding sg mRNA abundance (Di et al., 2017). These findings support previous suggestions that the local RNA secondary structure of each body TRS, which may be dynamic, as well as long distance genomic RNA-RNA interactions play important roles in regulating discontinuous RNA synthesis (Mateos-Gomez et al., 2013; Moreno et al., 2008; Pasternak et al., 2000; Sola et al., 2005).

EAV nsp1 was shown to play an essential role in sg RNA generation but little is known about how protein-protein and protein-RNA interactions regulate sg RNA synthesis (Tijms et al., 2007). It was suggested that nsp1 interaction with a particular body TRSs could stall a viral polymerase complex copying minus RNA from the genome at that site and that nsp1 may also facilitate targeting and base pairing between the body TRS complementary sequence and the leader TRS. EAV nsp10 also plays an important role in sg RNA synthesis (van Marle et al., 1999b). The EAV nsp1 consists of the regions equivalent to nsp1α and nsp1β of other arteriviruses due to mutation of the nsp1α cleavage site. The zinc finger located in the nsp1α region was shown to be critical for sg RNA production. SHFV encodes an additional nsp1 protein (nsp1γ) but this protein is not predicted to contain a zinc finger and no evidence has yet been obtained to indicate that either nsp1β or nsp1γ is involved in regulating sg RNA production.

Conclusions

Following the initial discovery that coronaviruses produce a nested set of 3ʹ co-terminal sg mRNAs with a common 5ʹ leader sequence, the main emphasis of research focused on determining the mechanism by which these sg mRNAs were generated. Minus strand sg RNAs were shown to be generated from the genomic template by a discontinuous transcription mechanism. These sg RNAs then function as templates for sg mRNA synthesis. The amplification, cloning and sequencing of the leader-body junction sequences of the sg mRNAs produced typically identified a single major TRS for each 3ʹ gene which had sequence homology to the leader TRS. However, the detection of alternative regulatory sequences mediating discontinuous transcription (heteroclite sg mRNAs) and 3ʹ co-terminal sg mRNAs without a 5ʹ leader indicate the use of additional mechanism for the generation of sg mRNA by some nidoviruses. Recent studies employing NGS and ribosome profiling have provided a greatly expanded view of the transcriptomes and coding capacities of both an arterivirus and a coronavirus. The finding that arterivirus and coronavirus may encode a number of small previously unidentified proteins opens new avenues for investigation of the cell-virus interaction.

Highlights.

Nidoviruses express their 3′ genes from a nested set of 3′ co-terminal sg mRNAs.

The sg mRNAs of some but not all Nidoviruses have a common 5′ leader sequence.

Transcription regulatory sequences in the genome are sites of premature minus stand termination.

Multiple alternative transcriptional regulatory sequences were identified for some 3′ORFs.

Next generation sequencing and ribosomal profiling identified additional coding capacity.

Acknowledgments

Support for the work described was provided by Public Health Service research grants AI073824 to M. Brinton and by a Georgia State University Molecular Basis of Disease seed grant to H. Di. H. Di was also supported by a Georgia State University Molecular Basis of Disease fellowship.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bentley K, Keep SM, Armesto M, Britton P. Identification of a noncanonically transcribed subgenomic mRNA of infectious bronchitis virus and other gammacoronaviruses. Journal of virology. 2013;87:2128–2136. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02967-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Kuo L, Rowland RR, Even C, Faaberg KS, Plagemann PG. Sequences of 3′ end of genome and of 5′ end of open reading frame 1a of lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus and common junction motifs between 5′ leader and bodies of seven subgenomic mRNAs. The Journal of general virology. 1993;74(Pt 4):643–659. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-4-643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong Y, Verlhac P, Reggiori F. The Interaction between Nidovirales and Autophagy Components. Viruses. 2017;9 doi: 10.3390/v9070182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowley JA, Dimmock CM, Walker PJ. Gill-associated nidovirus of Penaeus monodon prawns transcribes 3′-coterminal subgenomic mRNAs that do not possess 5′-leader sequences. J Gen Virol. 2002;83:927–935. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-4-927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries AA, Chirnside ED, Bredenbeek PJ, Gravestein LA, Horzinek MC, Spaan WJ. All subgenomic mRNAs of equine arteritis virus contain a common leader sequence. Nucleic Acids Research. 1990a;18:3241–3247. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.11.3241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries AA, Chirnside ED, Bredenbeek PJ, Gravestein LA, Horzinek MC, Spaan WJ. All subgenomic mRNAs of equine arteritis virus contain a common leader sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990b;18:3241–3247. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.11.3241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries AA, Glaser AL, Raamsman MJ, de Haan CA, Sarnataro S, Godeke GJ, Rottier PJ. Genetic manipulation of equine arteritis virus using full-length cDNA clones: separation of overlapping genes and expression of a foreign epitope. Virology. 2000;270:84–97. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Boon JA, Kleijnen MF, Spaan WJ, Snijder EJ. Equine arteritis virus subgenomic mRNA synthesis: analysis of leader-body junctions and replicative-form RNAs. Journal of virology. 1996;70:4291–4298. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4291-4298.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Boon JA, Snijder EJ, Chirnside ED, de Vries AA, Horzinek MC, Spaan WJ. Equine arteritis virus is not a togavirus but belongs to the coronaviruslike superfamily. Journal of virology. 1991;65:2910–2920. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.6.2910-2920.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di H, Madden JC, Jr, Morantz EK, Tang HY, Graham RL, Baric RS, Brinton MA. Expanded subgenomic mRNA transcriptome and coding capacity of a nidovirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:E8895–e8904. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1706696114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firth AE, Zevenhoven-Dobbe JC, Wills NM, Go YY, Balasuriya UBR, Atkins JF, Snijder EJ, Posthuma CC. Discovery of a small arterivirus gene that overlaps the GP5 coding sequence and is important for virus production. The Journal of general virology. 2011;92:1097–1106. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.029264-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer F, Peng D, Hingley ST, Weiss SR, Masters PS. The internal open reading frame within the nucleocapsid gene of mouse hepatitis virus encodes a structural protein that is not essential for viral replication. Journal of virology. 1997;71:996–1003. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.996-1003.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godeny EK, de Vries AA, Wang XC, Smith SL, de Groot RJ. Identification of the leader-body junctions for the viral subgenomic mRNAs and organization of the simian hemorrhagic fever virus genome: evidence for gene duplication during arterivirus evolution. Journal of virology. 1998;72:862–867. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.862-867.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorbalenya AE, Enjuanes L, Ziebuhr J, Snijder EJ. Nidovirales: evolving the largest RNA virus genome. Virus research. 2006;117:17–37. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2006.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain S, Pan J, Chen Y, Yang Y, Xu J, Peng Y, Wu Y, Li Z, Zhu Y, Tien P, Guo D. Identification of novel subgenomic RNAs and noncanonical transcription initiation signals of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Journal of virology. 2005;79:5288–5295. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.9.5288-5295.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irigoyen N, Firth AE, Jones JD, Chung BY, Siddell SG, Brierley I. High-Resolution Analysis of Coronavirus Gene Expression by RNA Sequencing and Ribosome Profiling. PLoS pathogens. 2016;12:e1005473. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CR, Griggs TF, Gnanandarajah J, Murtaugh MP. Novel structural protein in porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus encoded by an alternative ORF5 present in all arteriviruses. The Journal of general virology. 2011;92:1107–1116. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.030213-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joo M, Makino S. The effect of two closely inserted transcription consensus sequences on coronavirus transcription. Journal of virology. 1995;69:272–280. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.1.272-280.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan R, Chang RY, Brian DA. Tandem placement of a coronavirus promoter results in enhanced mRNA synthesis from the downstream-most initiation site. Virology. 1996;218:400–405. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Monica N, Yokomori K, Lai MM. Coronavirus mRNA synthesis: identification of novel transcription initiation signals which are differentially regulated by different leader sequences. Virology. 1992;188:402–407. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90774-J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai MM. Coronavirus leader-RNA-primed transcription: an alternative mechanism to RNA splicing. BioEssays : news and reviews in molecular, cellular and developmental biology. 1986;5:257–260. doi: 10.1002/bies.950050606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai MM, Brayton PR, Armen RC, Patton CD, Pugh C, Stohlman SA. Mouse hepatitis virus A59: mRNA structure and genetic localization of the sequence divergence from hepatotropic strain MHV-3. Journal of virology. 1981;39:823–834. doi: 10.1128/jvi.39.3.823-834.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai MM, Stohlman SA. RNA of mouse hepatitis virus. Journal of virology. 1978;26:236–242. doi: 10.1128/jvi.26.2.236-242.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry CR, Zhong X, Nielly-Thibault L, Roucou X. Found in translation: functions and evolution of a recently discovered alternative proteome. Current opinion in structural biology. 2015;32:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2015.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin YC, Chang RY, Chueh LL. Leader-body junction sequence of the viral subgenomic mRNAs of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus isolated in Taiwan. J Vet Med Sci. 2002;64:961–965. doi: 10.1292/jvms.64.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu DX, Fung TS, Chong KK, Shukla A, Hilgenfeld R. Accessory proteins of SARS-CoV and other coronaviruses. Antiviral research. 2014;109:97–109. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino S, Soe LH, Shieh CK, Lai MM. Discontinuous transcription generates heterogeneity at the leader fusion sites of coronavirus mRNAs. Journal of virology. 1988;62:3870–3873. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.10.3870-3873.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Masters, P.a.P.,S. Fields Virology Sixth Edition. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mateos-Gomez PA, Morales L, Zuniga S, Enjuanes L, Sola I. Long-distance RNA-RNA interactions in the coronavirus genome form high-order structures promoting discontinuous RNA synthesis during transcription. Journal of virology. 2013;87:177–186. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01782-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier C, Aricescu AR, Assenberg R, Aplin RT, Gilbert RJ, Grimes JM, Stuart DI. The crystal structure of ORF-9b, a lipid binding protein from the SARS coronavirus. Structure. 2006;14:1157–1165. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng XJ, Paul PS, Morozov I, Halbur PG. A nested set of six or seven subgenomic mRNAs is formed in cells infected with different isolates of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. J Gen Virol. 1996;77(Pt 6):1265–1270. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-6-1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meulenberg JJ, de Meijer EJ, Moormann RJ. Subgenomic RNAs of Lelystad virus contain a conserved leader-body junction sequence. J Gen Virol. 1993;74(Pt 8):1697–1701. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-8-1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WA, Koev G. Synthesis of subgenomic RNAs by positive-strand RNA viruses. Virology. 2000;273:1–8. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales L, Oliveros JC, Fernandez-Delgado R, ten Oever BR, Enjuanes L, Sola I. SARS-CoV-Encoded Small RNAs Contribute to Infection-Associated Lung Pathology. Cell host & microbe. 2017;21:344–355. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno JL, Zuniga S, Enjuanes L, Sola I. Identification of a coronavirus transcription enhancer. Journal of virology. 2008;82:3882–3893. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02622-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelsen CJ, Murtaugh MP, Faaberg KS. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus comparison: divergent evolution on two continents. Journal of virology. 1999;73:270–280. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.270-280.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor JB, Brian DA. Downstream ribosomal entry for translation of coronavirus TGEV gene 3b. Virology. 2000;269:172–182. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olasz F, Denes B, Balint A, Magyar T, Belak S, Zadori Z. Immunological and biochemical characterisation of 7ap, a short protein translated from an alternative frame of ORF7 of PRRSV. Acta veterinaria Hungarica. 2016;64:273–287. doi: 10.1556/004.2016.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozdarendeli A, Ku S, Rochat S, Williams GD, Senanayake SD, Brian DA. Downstream sequences influence the choice between a naturally occurring noncanonical and closely positioned upstream canonical heptameric fusion motif during bovine coronavirus subgenomic mRNA synthesis. Journal of virology. 2001;75:7362–7374. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.16.7362-7374.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasternak AO, Gultyaev AP, Spaan WJ, Snijder EJ. Genetic manipulation of arterivirus alternative mRNA leader-body junction sites reveals tight regulation of structural protein expression. Journal of virology. 2000;74:11642–11653. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.24.11642-11653.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasternak AO, Spaan WJ, Snijder EJ. Regulation of relative abundance of arterivirus subgenomic mRNAs. Journal of virology. 2004;78:8102–8113. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.15.8102-8113.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasternak AO, Spaan WJ, Snijder EJ. Nidovirus transcription: how to make sense…? The Journal of general virology. 2006;87:1403–1421. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81611-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasternak AO, van den Born E, Spaan WJ, Snijder EJ. Sequence requirements for RNA strand transfer during nidovirus discontinuous subgenomic RNA synthesis. The EMBO journal. 2001;20:7220–7228. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.24.7220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasternak AO, van den Born E, Spaan WJ, Snijder EJ. The stability of the duplex between sense and antisense transcription-regulating sequences is a crucial factor in arterivirus subgenomic mRNA synthesis. Journal of virology. 2003;77:1175–1183. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.2.1175-1183.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pueyo JI, Magny EG, Couso JP. New Peptides Under the s(ORF)ace of the Genome. Trends in biochemical sciences. 2016;41:665–678. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2016.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawicki SG, Sawicki DL. Coronavirus transcription: subgenomic mouse hepatitis virus replicative intermediates function in RNA synthesis. Journal of virology. 1990;64:1050–1056. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.3.1050-1056.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaad MC, Baric RS. Evidence for new transcriptional units encoded at the 3′ end of the mouse hepatitis virus genome. Virology. 1993;196:190–198. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schelle B, Karl N, Ludewig B, Siddell SG, Thiel V. Selective replication of coronavirus genomes that express nucleocapsid protein. Journal of virology. 2005;79:6620–6630. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.11.6620-6630.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sethna PB, Hung SL, Brian DA. Coronavirus subgenomic minus-strand RNAs and the potential for mRNA replicons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:5626–5630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.14.5626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SL, Wang X, Godeny EK. Sequence of the 3′ end of the simian hemorrhagic fever virus genome. Gene. 1997;191:205–210. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(97)00061-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits SL, van Vliet AL, Segeren K, el Azzouzi H, van Essen M, de Groot RJ. Torovirus non-discontinuous transcription: mutational analysis of a subgenomic mRNA promoter. Journal of virology. 2005;79:8275–8281. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.13.8275-8281.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snijder EJ, Kikkert M, Fang Y. Arterivirus molecular biology and pathogenesis. The Journal of general virology. 2013;94:2141–2163. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.056341-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snijder EJ, van Tol H, Pedersen KW, Raamsman MJ, de Vries AA. Identification of a novel structural protein of arteriviruses. Journal of virology. 1999;73:6335–6345. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.8.6335-6345.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sola I, Moreno JL, Zuniga S, Alonso S, Enjuanes L. Role of nucleotides immediately flanking the transcription-regulating sequence core in coronavirus subgenomic mRNA synthesis. Journal of virology. 2005;79:2506–2516. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.4.2506-2516.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel V, Siddell SG. Internal ribosome entry in the coding region of murine hepatitis virus mRNA 5. J Gen Virol. 1994;75(Pt 11):3041–3046. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-11-3041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tijms MA, Nedialkova DD, Zevenhoven-Dobbe JC, Gorbalenya AE, Snijder EJ. Arterivirus subgenomic mRNA synthesis and virion biogenesis depend on the multifunctional nsp1 autoprotease. Journal of virology. 2007;81:10496–10505. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00683-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Berlo MF, Horzinek MC, van der Zeijst BA. Equine arteritis virus-infected cells contain six polyadenylated virus-specific RNAs. Virology. 1982;118:345–352. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(82)90354-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Berlo MF, Rottier PJ, Horzinek MC, van der Zeijst BA. Intracellular equine arteritis virus (EAV)-specific RNAs contain common sequences. Virology. 1986;152:492–496. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(86)90154-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Born E, Gultyaev AP, Snijder EJ. Secondary structure and function of the 5′-proximal region of the equine arteritis virus RNA genome. RNA (New York, NY) 2004;10:424–437. doi: 10.1261/rna.5174804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Born E, Posthuma CC, Gultyaev AP, Snijder EJ. Discontinuous subgenomic RNA synthesis in arteriviruses is guided by an RNA hairpin structure located in the genomic leader region. Journal of virology. 2005;79:6312–6324. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.10.6312-6324.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Marle G, Dobbe JC, Gultyaev AP, Luytjes W, Spaan WJ, Snijder EJ. Arterivirus discontinuous mRNA transcription is guided by base pairing between sense and antisense transcription-regulating sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999a;96:12056–12061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.12056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Marle G, van Dinten LC, Spaan WJ, Luytjes W, Snijder EJ. Characterization of an equine arteritis virus replicase mutant defective in subgenomic mRNA synthesis. Journal of virology. 1999b;73:5274–5281. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5274-5281.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Vliet AL, Smits SL, Rottier PJ, de Groot RJ. Discontinuous and non-discontinuous subgenomic RNA transcription in a nidovirus. The EMBO journal. 2002;21:6571–6580. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vatter HA, Di H, Donaldson EF, Baric RS, Brinton MA. Each of the eight simian hemorrhagic fever virus minor structural proteins is functionally important. Virology. 2014:462–463C. 351–362. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Zhang X. The leader RNA of coronavirus mouse hepatitis virus contains an enhancer-like element for subgenomic mRNA transcription. Journal of virology. 2000;74:10571–10580. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.22.10571-10580.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu HY, Brian DA. Subgenomic messenger RNA amplification in coronaviruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:12257–12262. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000378107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan S, Murtaugh MP, Faaberg KS. Heteroclite subgenomic RNAs are produced in porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus infection. Virology. 2000;275:158–169. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan S, Murtaugh MP, Schumann FA, Mickelson D, Faaberg KS. Characterization of heteroclite subgenomic RNAs associated with PRRSV infection. Virus research. 2004;105:75–87. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng L, Godeny EK, Methven SL, Brinton MA. Analysis of simian hemorrhagic fever virus (SHFV) subgenomic RNAs, junction sequences, and 5′ leader. Virology. 1995;207:543–548. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Liu R. Identification of a noncanonical signal for transcription of a novel subgenomic mRNA of mouse hepatitis virus: implication for the mechanism of coronavirus RNA transcription. Virology. 2000;278:75–85. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Shaw K, Cavanagh D. Presence of subgenomic mRNAs in virions of coronavirus IBV. Virology. 1993;196:172–178. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zirkel F, Roth H, Kurth A, Drosten C, Ziebuhr J, Junglen S. Identification and characterization of genetically divergent members of the newly established family Mesoniviridae. Journal of virology. 2013;87:6346–6358. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00416-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuniga S, Sola I, Alonso S, Enjuanes L. Sequence motifs involved in the regulation of discontinuous coronavirus subgenomic RNA synthesis. Journal of virology. 2004;78:980–994. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.2.980-994.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]