Abstract

Recent studies have revealed an important role for the Staphylococcus aureus CidC enzyme in cell death during the stationary phase and in biofilm development, and have contributed to our understanding of the metabolic processes important in the induction of bacterial programmed cell death (PCD). To gain more insight into the characteristics of this enzyme, we performed an in-depth biochemical and biophysical analysis of its catalytic properties. In vitro experiments show that this flavoprotein catalyzes the oxidative decarboxylation of pyruvate to acetate and carbon dioxide. CidC efficiently reduces menadione, but not CoenzymeQ0, suggesting a specific role in the S. aureus respiratory chain. CidC exists as a monomer under neutral pH conditions but tends to aggregate and bind to artificial lipid membranes at acidic pH, resulting in enhanced enzymatic activity. Unlike its Escherichia coli counterpart, PoxB, CidC does not appear to be activated by other amphiphiles like Triton X-100 and Octyl β-D-glucopyranoside. In addition, only reduced CidC is protected from proteolytic cleavage by chymotrypsin, and, unlike its homologues in other bacteria, protease treatment does not increase CidC enzymatic activity. Finally, CidC exhibits maximal activity at pH 5.5 to 5.8 and negligible activity at pH 7 to 8. The results of this study are consistent with a model in which CidC functions as a pyruvate:menaquinone oxidoreductase whose activity is induced at the cellular membrane during cytoplasmic acidification, a process previously shown to be important for the induction of bacterial PCD.

Introduction

Studies of the Staphylococcus aureus cidABC and lrgAB operons have revealed a complex network of membrane-associated proteins and metabolic enzymes with a significant role in the regulation of bacterial viability1–3. The integral membrane proteins CidA and LrgA have been suggested to functionally resemble members of the Bcl-2 family of proteins that control apoptosis in eukaryotic organisms4, and mutations in cidA and lrgA are associated with cell death phenotypes5,6. It has been therefore proposed that the widely conserved cid and lrg operons control bacterial PCD7,8, which most dramatically manifests within the multicellular environment of the biofilm6,9.

The Cid/Lrg system has been shown to rely on the activities of two membrane proteins that function in a manner that is analogous to bacteriophage-encoded holins, known to be required for the control of cell death and lysis during the lytic cycle of a bacteriophage infection10. Similar to holins, the CidA and LrgA proteins are small, integral membrane proteins that form high molecular weight oligomers11. In addition, recent studies indicate that the gene products of the cidABC and lrgAB operons have opposing functions in the control of cell death and lysis3,12. These striking functional and biochemical properties of the Cid and Lrg proteins have laid the foundation for the model that they represent the progenitors of the regulatory control of apoptosis in more complex eukaryotic organisms13,14.

Our laboratory has recently demonstrated that cidC, which is the third gene of the cidABC operon and was reported to encode a pyruvate oxidase family protein15, also plays a major role in the control of bacterial PCD by potentiating cell death16. This process was shown to involve the CidC-mediated conversion of intracellular pyruvate to acetate, which leads to cytoplasmic acidification and respiratory inhibition. Pyruvate is an important intermediate in carbohydrate metabolism that is directly metabolized by many types of flavoenzymes in bacteria17–21. Two classes of thiamin diphosphate (TPP)- and flavin-dependent enzymes are differentiated by the Enzyme Commission (EC) according to their immediate electron acceptor: pyruvate oxidases or pyruvate:O2-oxidoreductases (EC 1.2.3.3) pass the electron directly to oxygen, while pyruvate:quinone oxidoreductases (EC 1.2.5.1) pass the electron to a quinone. The former enzyme requires phosphate and produces acetyl-phosphate, while the latter requires water and generates acetate with the full reactions shown in Equation 1.

| Equation 1 |

Well characterized examples of these enzymes include pyruvate:oxygen 2-oxidoreductases like Lactobacillus plantarum POX and Streptococcus pneumoniae SpxB, which consume oxygen and participate in cellular signaling via the generation of acetyl-phosphate22 and in cell death via the production of H2O223,24. Pyruvate:quinone oxidoreductases like Escherichia coli PoxB and Corynebacterium glutamicum PQO, on the other hand, directly transfer electrons from the cytoplasm into the membrane respiratory chain. The enzymatic properties and structures have been determined for both PoxB and PQO, and the results demonstrate that the activities of these enzymes are largely subject to substrate concentration and membrane binding status25,26. S. aureus CidC shares about 33% amino acid sequence identity with both PQO and PoxB, and previous in vivo studies suggest that CidC is responsible for the conversion of pyruvate to acetate15,16,27. The current study focuses on elucidating the basic biochemical and biophysical properties of CidC and suggests its activity as a pyruvate:quinone oxidoreductase, which uses menaquinone as a direct electron acceptor. In addition, these studies demonstrate that CidC has unique substrate-, cofactor-, and membrane-binding properties, which are different from previously characterized homologous enzymes. The findings shed light on how this enzyme plays a critical role during cytoplasmic acidification and how this is important for bacterial PCD.

Experimental Procedures

Materials

For protein purification, chromatographic columns and an AKTA Purifier 10 from GE Healthcare (Pittsburgh, PA), as well as rotors and an Allegra 25R centrifuge from Beckman Coulter (Indianapolis, IN) were employed. The Penta-His Antibody from Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA) was used for western blot detection. Glucose oxidase from Aspergillus niger (160 kDa) and human serum albumin (66.5 kDa) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The n-octyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (OG) detergent was from Anatrace (Maumee, OH). All other chemicals and reagents were from Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA).

Protein expression

The recombinant CidC protein (UniProt Q6PST7, with a C-terminal histidine tag) was expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) using a plasmid previously described15. Batches of 750 mL bacterial cultures were grown in 3 L baffled flasks using 2X TY media (16 g/L tryptone, 10 g/L yeast extract and 5 g/L sodium chloride supplemented with 0.1 mg/mL kanamycin) at 37°C while shaking at 200 RPM in an Excella E24 incubator (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). Bacterial growth was monitored by measuring light scattering at 600 nm (OD600) with a NanoDrop 2000c UV-Vis Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). Protein production was induced by the addition of 1 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside when the OD600 reached 3 and was carried out for 4 hours at 37°C when the OD600 reached approximately 6. Cells were collected by centrifugation at 5,000 RPM for 15 minutes at 4°C using a TS-5.1-500 rotor and were then stored at −20°C until further processing.

Protein purification

Frozen cells were thawed and resuspended in TS8 buffer (20 mM Tris, 500 mM NaCl, pH 8.0). Cell lysis was induced by the addition of 0.25 mg/mL lysozyme, 5 μg/mL nuclease, 1% w/w Triton X-100 and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride while stirring the cell suspension at 25°C for 30 minutes. Lysis was completed by sonication using four, 30-second pulses on ice via a 15 W Microtip on a Misonix Sonicator 3000 (Misonix Inc, Farmingdale, NY). Insoluble material was discarded by centrifugation at 7,500 RPM and 4°C for 30 minutes in TA-14 rotor. Protein purification was immediately performed using a two-step strategy. First, detergent-solubilized cells were loaded onto a 25 mL HisPrep FF affinity column in TS8 buffer. The column was then washed with 100 mL of TS8 buffer containing 20 mM imidazole and the His-tagged CidC was finally eluted with TS8 buffer containing 300 mM imidazole. The protein solution was immediately supplemented with 15% glycerol and stored in aliquots at −20°C until needed. Second, just before the experiments were performed, CidC was further purified by gel filtration using a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL column in 200 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). The enzyme concentration was estimated via UV-Vis 11,026/cm/M (at 450 nm, corresponding to FAD absorption), which provides a more accurate determination of the active portion of CidC sample. Protein purification and all experiments were conducted at 25°C.

Liposome preparation

Small phospholipid vesicles were formulated using a 7:3 w/w mixture of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-[phospho-rac-(1-glycerol)] (POPG) and 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC) lipids (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL). The lipids were weighted and thoroughly dissolved in sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 60 mM OG detergent by incubating for 15 minutes at 37°C until the solution was clear. Liposomes were then formed via 10X dilution of the above lipid-detergent solution into sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) while mixing vigorously, followed by detergent removal via overnight dialysis against sodium phophate buffer (pH 7.0) using Spectra/Por 6 dialysis membranes with a 10 kDa cutoff (Spectrum Laboratories, Rancho Dominguez, CA). The liposomes were finally extruded 11 times through 400 nm Whatman nuclepore track-etched membranes (GE Healthcare, Pittsburgh, PA) using a Mini-Extruder (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL) and used immediately.

Ferricyanide assay for CidC activity

2 μM CidC (with urea, Triton X-100, OG, citrate, or liposomes added as indicated) was first incubated with 20 mM pyruvate, 10 μM TPP and 1 mM Mg2+ in sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) for 20 minutes. 8 mM ferricyanide was then added and its reduction was immediately visible as it lost its color. Consequently, the CidC activity was measured as a decrease in absorption at 450 nm over time. The pH-dependent CidC activity was similarly tested in the presence of 200 mM sodium acetate over a pH range of 5.0 to 5.6 and 200 mM sodium phosphate buffer over a pH range of 5.6 to 8.0. The enzyme activity was identical at pH 5.6 in both sodium acetate and sodium phosphate. One unit (1U) of pyruvate oxidoreductase activity is defined as the amount of enzyme required to consume 1 μmole of pyruvate in one minute. The CidC specific activity was estimated accordingly within one minute of the ferricyanide addition, taking into account that (i) two equivalents of ferricyanide are reduced per equivalent of decarboxylated pyruvate, and (ii) the extinction coefficient of ferricyanide at 450 nm is 0.218 mM−1 cm−1.

Acetate quantification

The “Acetic Acid Test Kit” (R-Biopharm AG, Darmstadt, Germany) was used using the provided instructions to measure acetate concentrations. Protein samples of 2 μM CidC alone, or 2 μM CidC supplemented with either 0.05% Triton X-100 or 3 M urea were first incubated with 20 mM pyruvate, 10 μM TPP and 1 mM Mg2+ in sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) for 20 minutes. 8 mM sodium ferricyanide was then added and the acetate levels were measured in triplicate after 30 minutes when the reaction was completed. The urea-containing sample was used as a negative control, while a 5 mM acetate solution was used as a positive control.

H2O2 quantification

Peroxidase catalyzes the reaction of H2O2 with 4-aminoantipyrine and phenol to form 4-(p-benzoquinone-monoimino)-phenazone with a 510 nm absorbance proportional to the initial H2O2 concentration28–30. This reaction was calibrated for H2O2 quantification in the 1 to 10 mM range (R2=0.99). 20 mM pyruvate, 10 μM TPP, 1 mM Mg2+ were incubated with 2 μM CidC alone, or 2 μM CidC supplemented with either 0.05% Triton X-100 or 3M urea in sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) for 20 minutes, after which 35 mM phenol, 10 mM 4-aminoantipyrine and 1 μM horseradish peroxidase were added. The activity of glucose oxidase was used as a positive control since it converts glucose to gluconolactone and H2O2.

CidC quinone electron transport assay

These experiments were conducted similarly as the ferricyanide assay, except that the 8 mM ferricyanide was replaced with 250 μM MN0 and CoQ0 [the headgroups of either menaquinone or ubiquinone, respectively, from a dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) stock] and 80 μM cytochrome c. The cytochrome reduction was followed spectroscopically at 550 nm.

Kinetic analysis

CidC enzyme activity assays were conducted using the above electron acceptors with concentrations up to 20 mM under specified conditions (different pH values, and with or without liposomes). The reactions were spectroscopically monitored for up to two minutes and the initial reaction velocities were calculated using the data within the first 20 seconds. Km and kcat parameters were then calculated using the Michaelis-Menten equation.

The pH dependencies of values of kcat vs. pH were analyzed according to the rapid equilibrium diprotic model31, which is used if the difference in pKa values is less than 3.5 pH units. The following expressions were derived for kcat and kcat ⁄Km:

| (1) |

| (2) |

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

Samples were incubated with 5 nm Ni-NTA-Nanogold (Nanoprobes, Yaphank, NY) to label CidC for 30 minutes. 10 μL of the sample were then placed on thin carbon films on holey grids and allowed to absorb for two minutes, after which the grid was washed twice with 10 μL of deionized water and negatively stained with methylamine vanadate. Imaging was carried out with a Tecnai G2 transmission electron microscope (FEI) operated at 80 kV.

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC)

ITC was carried out on a MicroCal iTC200 (Malvern Instruments Ltd, Worcestershire, UK). 40 μl of 100 μM CidC in sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) was injected into 250 μl of 200 mM sodium phosphate (pH 6.0) buffer containing various ingredients as specified. A total of 20 injections (2 μL each, spaced by 5 minutes) were performed at room temperature. Data was analyzed using the Origin software (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA).

Tryptophan fluorescence titration

Purified CidC in sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) was diluted in either pH 6.0 or pH 7.0 sodium phosphate buffer to a final concentration of 850 μM in 1.3 mL. TPP was then added in 1.5 μL increments from a 100 μM stock in water and the solution was mixed for 30 seconds. At each increment the tryptophan fluorescence (280 nm excitation, 340 nm emission) was measured with a Spex Fluorlog 322 fluorescence spectrophotometer (Jobin Yvon, Edison, NJ) in a 1500 μL stirred quartz cuvette at 25°C. Data was processed using the Origin software (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA).

Protease treatment

2 μM CidC in 200 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0 or pH 7.0) containing either of 20 mM pyruvate, 10 μM TPP, or 1 mM Mg2+ was incubated for 30 minutes. 1 μM trypsin or chymotrypsin was then added and proteolytic cleavage was conducted for 30 minutes. The solution was immediately tested for activity using the ferricyanide assay or was immediately precipitated using methanol:chloroform (4:1 v/v) and studied by SDS-PAGE.

Results

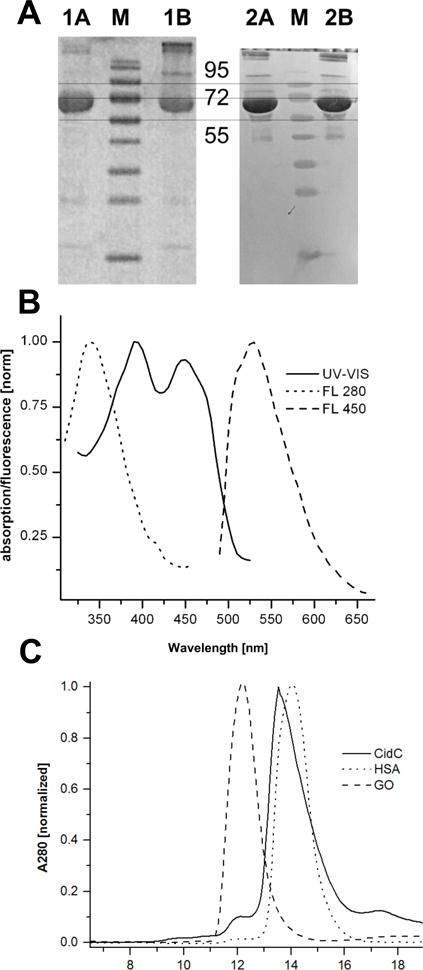

To study the S. aureus CidC enzyme, a previously established expression plasmid15 was used to generate milligram amounts of purified protein. Initial screening using western blot analysis of the C-terminal histidine tag of CidC showed that E. coli BL21(DE3) cells containing this plasmid produce large quantities of this enzyme (data not shown). A first-step affinity chromatography procedure employing Ni-NTA resin resulted in pure and stable protein in 200 mM phosphate buffer (pH 8) containing 500 mM NaCl and 300 mM Imidazole (Fig. 1A). As expected for flavoproteins, CidC exhibited characteristic UV-Vis absorption at 380 and 450 nm and fluorescence at 530 nm (with 450 nm excitation) as shown in Fig. 1B28,32. The intrinsic fluorescence of CidC was observed at 340 nm (with 280 nm excitation), also shown in Fig. 1B32. By measuring the A280 (the protein peak) and A450 (FADH2 peak), it was determined that at least 80% of CidC binds FAD, thus no attempt to supplement this flavoprotein with FAD was made in subsequent experiments. The CidC molecular weight (calculated average of 64,806 Da) was qualitatively confirmed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1A) and quantitatively by mass spectrometry to within a few Da (data not shown). The first five amino acids (Ala, Lys, Ile, Lys and Ala) were verified by N-terminal sequencing (data not shown) strongly confirming the identity of the purified protein (the first methionine was cleaved during expression in E. coli). The protein solution was mixed with 20% (v/v) glycerol and stored at −20°C until experiments were performed.

Figure 1. CidC purification and optical characterization.

(A) SDS-PAGE gel (left) and western blot (right) of purified CidC in the presence (lanes 1A, 2A) or absence (lanes 1B, 2B) of β-mercaptoethanol. Relevant bands in the marker lanes (M) are identified by their MW in kDa. (B) UV-Vis and fluorescence with excitation at 280 (FL 280) and 450 nm (FL 450) spectra of CidC at pH 7. (C) Purification of proteins: CidC, human serum albumin (HSA) and glucose oxidase (GO) were each separately purified. The asterisk denotes CidC dimers.

As demonstrated below, the recombinant CidC protein is only active between pH 5 and pH 6.5, however, it also precipitates rapidly under acidic pH. The addition of high concentrations of arginine and NaCl delays protein self-aggregation, but these additives were also found to inhibit the enzymatic activity of this protein. A NaCl-free and neutral solution is therefore required to maintain a stable CidC preparation. To achieve this, an additional purification step was implemented to lower the pH and NaCl content of the CidC preparation by performing gel filtration chromatography in 200 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7) without NaCl (Fig. 1C). The CidC sample can then be diluted or titrated into a more acidic buffer to perform activity assays. This protein formulation provided consistent results among different protein batches while also minimizing the effect of self-aggregation.

CidC interaction with phospholipid membranes

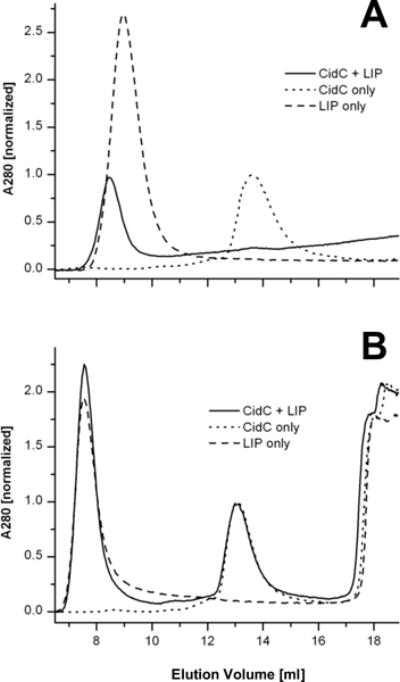

The E. coli pyruvate quinone oxidoreductase, PoxB, exists in a soluble and inactive form within the cytoplasm and becomes active upon binding to the cellular membrane25,33–36. To study the interaction of CidC with membranes, liposomes prepared with a simple mixture of POPG:POPC (7:3 w/w) were used to mimic the cytoplasmic membrane lipid composition of S. aureus37,38. Three samples containing (i) CidC, (ii) liposomes, and (iii) a CidC-liposome mixture were subjected to the same gel filtration procedure described above in 200 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6) (Fig. 2A). Due to their large dimensions, the liposomes elute in the void volume and also scatter light, which translated into an apparent absorption at 280 nm. The peak corresponding to the CidC monomer disappears completely when the CidC-liposome mixture is analyzed, suggesting that CidC co-elutes with the liposomes. The sum of the A280 signals generated by the liposomes and CidC alone is significantly larger than the signal obtained when the mixture is injected, suggesting that CidC not only binds to the membranes, but also aggregates with the liposomes into much larger assemblies that are trapped on the column and do not elute at all. To test this, the CidC membrane-binding experiment was repeated with 500 mM NaCl added to the running buffer as shown in Fig. 2B. Under these conditions, CidC elutes independently from the liposomes when the CidC-liposome mixture is injected. The experiment repeated in sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7) generates a similar result to the pH 6 buffer with 500 mM NaCl, indicating that CidC interacts with the liposomes to a much lower extent at pH 7 (data not shown).

Figure 2. CidC interaction with liposomes by gel filtration.

(A) CidC, liposomes (LIP), and their mixture were purified. The asterisk denotes a minute amount of monomeric CidC eluting from the CidC-LIP mixture. (B) As in (A), except that 500 mM NaCl was used during purification. The asterisk denotes the elution of small molecules (e.g. salts, residual detergents, etc.). The inclusion of high salt slightly changes the physical properties of the column, e.g. the void volume and monomeric CidC elution are shifted when compared to (A). Data was scaled relative to the protein A280 in all cases.

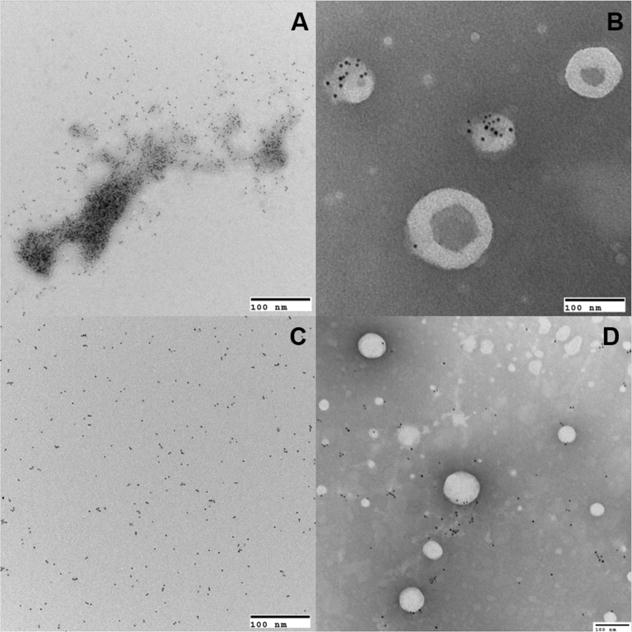

The interaction of CidC with membranes was further probed by TEM. As shown in figure 3C, purified nano-gold labeled CidC protein aggregates at pH 6 (Fig. 3A) but remains a monomer at pH 7 (Fig. 3C). When liposomes were added, CidC-liposome co-localization was observed only at pH 6 (Fig. 3B). Very large structures were also observed at pH 6 most likely representing CidC-liposome aggregates in agreement with the gel filtration data above (data not shown). When the cofactors TPP/Mg2+ were added to the sample, the same co-localization was observed, indicating that the presence of cofactors alone does not promote CidC localization to the membrane if the pH is not optimal. As expected, CidC does not co-localize with liposomes (or binds very weakly) in pH 7 buffer, as shown in Fig. 3D, also consistent with the results generated using gel-filtration chromatography. Combined, the data above demonstrates that CidC spontaneously binds to membranes in acidic pH and that this interaction is mostly electrostatic in nature.

Figure 3. TEM characterization of CidC.

TEM images showing CidC as labeled by 5 nm nanogold particles and liposomes by negative staining. CidC in 200 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 6 was either mixed without liposomes (A), or with liposomes (B), similarly, CidC in 200 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 7 was either mixed without liposomes (C), or with liposomes (D).

CidC converts pyruvate to acetate in vitro

Two possible enzymatic reactions are catalyzed by pyruvate oxidoreductases: one converts pyruvate to acetate and carbon dioxide, and the other to acetyl-phosphate and hydrogen peroxide. The reactions can be identified by detecting acetate and hydrogen peroxide, respectively, as the reaction end products. A note is made that this reaction requires a quinone, which was substituted with ferricyanide and that the acetyl-phosphate pathway requires phosphate and oxygen, which were present in the sodium phosphate buffer. Previous studies have shown that pyruvate:quinone oxidoreductases are minimally active in the absence of amphiphiles such as Triton X-100 detergent or phospholipids21,39,40. For this reason, Triton X-100 was incorporated in some of the assays to potentially activate CidC. Tests were initially performed at pH 6, which provides a good compromise between the pH optimal for CidC activity and self-aggregation; however, some pyruvate:quinone oxidoreductases exhibit a strong pH-dependent activity30. In order to ensure that CidC does not produce hydrogen peroxide at a different pH, a wide pH range was screened.

CidC was incubated for one hour with pyruvate, the TPP/Mg2+ cofactor, and the artificial electron acceptor ferricyanide in sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6) to allow for the complete enzymatic conversion of pyruvate by CidC. Initial tests showed that the reaction completes within several minutes under the conditions utilized and that longer incubation times do not change the enzymatic outcome. This solution was then tested for the presence of acetate and hydrogen peroxide. Acetate was quantitatively confirmed in the CidC enzymatic end products (Fig. S1A). Two equivalents of ferricyanide are reduced per equivalent of decarboxylated pyruvate by pyruvate oxidases39. In this case, 20 mM pyruvate and 8 mM ferricyanide were used, making ferricyanide the reaction-limiting reactant. If all of the pyruvate is converted to acetate, the final acetate concentration is expected to be half that of ferricyanide (or about 4 mM). An average value of 4.48 ± 0.01 mM acetate was indeed measured suggesting that CidC efficiently converted all pyruvate to acetate under these conditions. Inclusion of 1% w/v Triton X-100 did not significantly affect the reaction, while inclusion of 3 M urea severely limited the generation of acetate and stoichiometric substitution of CidC with lysozyme in this experiment resulted in no detectable acetate production. Hydrogen peroxide was absent from the end products of the CidC-catalyzed reaction (Fig. S1B), even when 1% w/v Triton X-100 was added to the reaction. The above CidC catalytic reaction was also conducted across a pH range of 5 to 8; however, hydrogen peroxide could not be detected in any of these assays.

Modulators of CidC enzymatic activity

Previous studies on E. coli PoxB and C. glutamicum PQO showed that these enzymes can be activated by amphiphiles, including both detergent and phospholipids, and are minimally active in their absence21,36,40,41. To test whether CidC exhibits similar properties, the effects of detergents and lipids on the CidC enzymatic activities were investigated. CidC was incubated with pyruvate, TPP/Mg2+ and several activity modulators. The enzymatic reactions were initiated by the addition of ferricyanide and monitored by following its reduction via the change of absorbance at 450 nm. Based on the calculated initial rates of enzymatic activity, Triton X-100, as well as the milder detergent, OG, did not alter enzyme activity even when added at high concentrations (Table 1). However, the presence of POPG:POPC (7:3 w/w) liposomes, which mimic the S. aureus membrane, induced a three-fold increase in the initial velocity (0.31 ± 0.03 mM/s). As expected, the presence of 3 M urea resulted in no ferricyanide reduction.

Table 1.

CidC activity modulators.

| Protein/Enzyme | Modulator | Concentration | Initial rate (mM/s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CidC (0.78 μM) | NA | NA | 0.14 ±0.03 |

| Triton X-100 | 1% (v/v) | 0.16 ± 0.03 | |

| Triton X-100 | 0.05% (v/v) | 0.16 ± 0.02 | |

| Urea | 3M (pre-incubate 10 min) | 0 | |

| OG | 5 mM | 0.15 ± 0.01 | |

| liposome | 0.5 mg/ml | 0.31 ± 0.03 | |

| NaCl | 50 mM | 0.13 ± 0.01 | |

| NaCl | 100 mM | 0.09 ± 0.01 | |

| NaCl | 250 mM | 0.04 ± 0.02 | |

| NaCl | 500 mM | 0.02 ± 0.01 | |

| Lyzozyme (0.78 μM) | NA | NA | 0 |

Since NaCl impaired CidC self-aggregation and interaction with membranes, its effect on CidC catalysis was also investigated. NaCl was able to inhibit CidC activity in a dose dependent manner (Table 1). At higher concentrations, the effect was much more pronounced, almost completely abolishing the enzymatic activity. The effect of NaCl is likely to be a function of the Cl− ion since Na+ was present in the buffer at 200 mM. The results of these experiments suggest that CidC activity is enhanced by interacting with phospholipid membranes, but not by non-ionic detergents, and that these interactions are likely to be electrostatic in nature.

CidC activity is strongly pH dependent

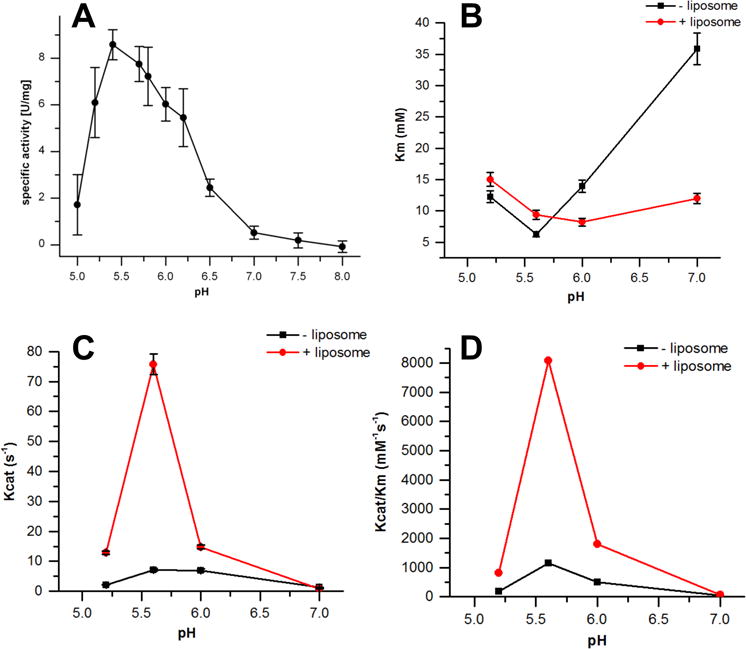

To investigate the pH optimum of CidC activity, the specific decarboxylation activity of CidC at different pH values was measured using ferricyanide as the electron acceptor, as shown in Fig 4A. It was found that CidC reaches the maximum catalytic activity from pH 5.4 to 5.8, and is minimally active at or above pH 7. It is worthy of note that this experiment was repeated using sodium acetate buffer from pH 5.4 to pH 5.6, confirming that CidC is not a phosphate dependent pyruvate oxidase like POX from L. plantarum.

Figure 4. pH-dependence of CidC activity.

The kinetic profile of CidC catalysis at different pHs as monitored by the ferricyanide assay. (A) The calculated CidC specific activity as a function of pH 5 to 8. (B) The calculated Km as a function of pH 5.2, 5.6, 6.0 and 7.0. (C) The calculated kcat as a function of pH 5.2, 5.6, 6.0 and 7.0. (D) The calculated kcat/Km as a function of pH 5.2, 5.6, 6.0 and 7.0.

The enzymatic kinetic parameters of CidC was also determined at four different pH values: 5.2, 5.6, 6, and 7, in the presence and absence of POPG:POPC (w/w 7:3) liposomes. As shown in Fig 4 (B, C, and D), CidC has the lowest Km, highest kcat and, thus, the highest catalytic efficiency kcat/Km (1144 ± 124 M−1s−1) for pyruvate at pH 5.6 in the absence of liposomes. When liposomes are added, the Km does not change substantially at acidic pH, but is lowered by three-fold at pH 7 (Fig. 4B). The kcat value also reaches its peak at pH 5.6 in the presence of liposomes (Fig. 4C), which is 10 times higher than that without liposomes, as is reflected in the kcat/Km value (Fig. 4D). These results demonstrate that under the optimum working pH range, interactions of CidC with liposomes greatly increases the turnover rate of this enzyme with pyruvate, but has a very limited effect on its binding affinity for CidC.

Moreover, the pH dependence of kcat (Fig. 4C) and kcat/Km (Fig. 4D) plots further generate the pKa values for enzyme-substrate complex and free enzyme, as shown in Supplementary data Table S1. The data was modeled using eq 1 and eq 2, where KHE and KH2E are the ionization constants for the free enzyme, KHES and KH2ES are the ionization constants of the ES complex (see Experimental Procedures section). The differences in the values observed can be attributed to CidC since there is no ionizable group in the substrate, pyruvate (pKa=2.5). Also, the range of pKHE and pKH2E values in the absence of liposomes (5.4-5.6) is relatively narrow compared to when liposomes are present (5.1-5.9), suggesting that binding to liposomes causes slight changes in the protonation profile of the CidC binding pocket that stimulates its activity.

CidC only binds its TPP/Mg2+ cofactor at acidic pH

To test the interaction of CidC with its cofactors, ITC experiments were performed. The interaction between CidC and TPP/Mg2+ was specifically characterized at pH 6, where CidC is active, and pH 7, where CidC is not active. CidC in sodium phosphate (pH 7) buffer (to minimize self-aggregation) was loaded into the ITC syringe and titrated into buffers containing TPP, and TPP/Mg2+. A strong exothermic interaction between CidC and TPP/Mg2+ was observed in pH 6 buffer, but was significantly lower in the absence of Mg2+ and at pH 7 (Fig. S2). The results of these studies suggest that the pH dependence of CidC is due to the differential binding of TPP/Mg2+, and that Mg2+ facilitates the binding of TPP, as is consistent with other studies42–44.

Limited by the self-aggregation of CidC in acidic pH, we could not measure the Kd and enthalpy of binding using ITC. Instead, we used a fluorescence-quenching assay to determine those parameters, as intrinsic fluorescence-based assays are more sensitive and require a lot less protein, thereby avoiding the rapid aggregation of CidC. Under the test conditions used here, CidC remained stable at pH 6 for the duration of the experiment. The tryptophan fluorescence of CidC was measured in the presence of various TPP/Mg2+ concentrations. The fluorescence-concentration relationship was fit into a double reciprocal plot, so as to determine the Kd (see Experimental Procedures). It was found that CidC has the highest binding affinity for TPP in the presence of Mg2+ at pH 6 (Kd = 0.3 μM); without Mg2+ the affinity was 10 times lower (Kd = 3 μM). However, the Kd was 26.2 μM for CidC and TPP + Mg2+ at pH 7, indicating a much lower binding affinity. Together, these results indicate that CidC binds TPP strongly at acidic pH and has a very low affinity for TPP at neutral pH. In addition, Mg2+ greatly enhances TPP binding at acidic pH conditions.

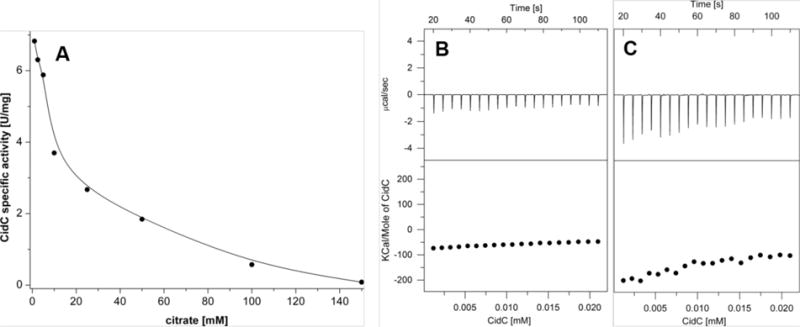

Citrate inhibits CidC activity

When testing the pH dependence of CidC activity, citrate-based buffers were initially found to have a concentration-dependent effect on CidC activity. Further analysis using the ferricyanide-based assay described above demonstrated that citrate inhibits CidC activity with an IC50 of 10 mM at pH 6.0 (Fig. 5A). ITC experiments similar to those presented above indicate that citrate directly binds to CidC at pH 6 in the absence of pyruvate and TPP/Mg2+. When CidC was titrated into sodium phosphate (pH 6) buffer supplemented with 10 mM pyruvate, an exothermic protein structural change of about −50 kCal/mole of CidC was observed (Fig. 5B). However, titration into sodium phosphate (pH 6) buffer supplemented with 10 mM citrate revealed a reaction with approximately −200 kCal/mole of CidC (in the first injections, Fig. 5C), most likely due to binding of citrate to CidC in addition to the pH-induced CidC conformational change, which is stronger than that of CidC binding to pyruvate.

Figure 5. Citrate inhibition of CidC.

(A) The CidC specific activity in the presence of citrate in pH 6 buffer was measured by the ferricyanide assay. (B-C) ITC experiments as in Fig. 8, except that CidC was titrated into (B)pyruvate, pH 6 buffer and (C) 10 mM citrate, pH 6 buffer.

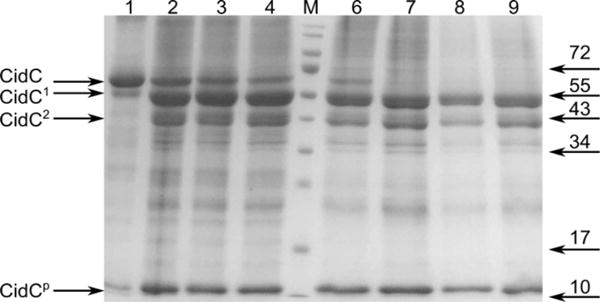

Truncated CidC maintains enzymatic activity

E. coli PoxB was shown to be activated after treatment with chymotrypsin25,36,45–47. The effects of both trypsin and chymotrypsin were therefore investigated here at both pH 6 when CidC is active and at pH 7 when CidC is mostly inactive. The results for trypsin are shown in Fig. 6 noting that identical results were obtained for chymotrypsin (data not shown). Similar to previous results for other pyruvate:quinone oxidoreductases, CidC was protected from proteolytic cleavage only if pyruvate and TPP/Mg2+ were all available to the enzyme, e.g. when the enzyme was fully reduced. However, the protection is very efficient only at pH 6 and is completely absent at pH 7. During the 30 minutes of cleavage at pH 6, only a minute fraction of CidC cleaved to a product labeled as CidC1, while at pH 7 most of the enzyme was converted to CidC1 and CidC2. CidC1 and CidC2 are only a few kDa and about 20 kDa smaller, respectively, than CidC and resemble the 58 and 51 kDa species obtained by proteolysis of the E. coli PoxB previously reported36. No further attempts were made to characterize these truncated proteins at the amino acid sequence level.

Figure 6. Proteolysis of CidC.

SDS-PAGE showing the CidC cleavage products after 30 minutes of incubation with trypsin at pH 6 (lanes 1-4) and pH 7 (lanes 6-9). Before proteolysis, CidC was incubated with (lanes 1, 6) pyruvate, TPP and Mg2+, (lanes 2, 7) TPP and Mg2+, (lanes 3, 8) pyruvate, (lanes 4, 9) Mg2+. CidC products are shown on the left with CidC1 and CidC2 being several kDa and, respectively, about 20 kDa smaller than CidC, while CidCp indicates small peptides. Several bands from the marker (lane M) are labeled on the right.

When either of (i) pyruvate, (ii) TPP/Mg2+, or (iii) Mg2+ were provided to CidC, trypsin was very effective in cleaving CidC at both pH 6 and 7 (Fig. 6). These results suggest that CidC is protected from trypsin only when it is active (at pH 6) and when both the pyruvate substrate and the TPP/Mg2+ cofactors are present, that is to say, the reducing form of CidC (with FADH2 and TPP) adopts a conformation which is protected from proteolysis. The activities of the CidC1 and CidC2 degradation products were also investigated using the ferricyanide assay and were found to be as active as their CidC parent at pH 6; as with the intact enzyme, no measurable activity of the truncated proteins could be detected at pH 7 (data not shown).

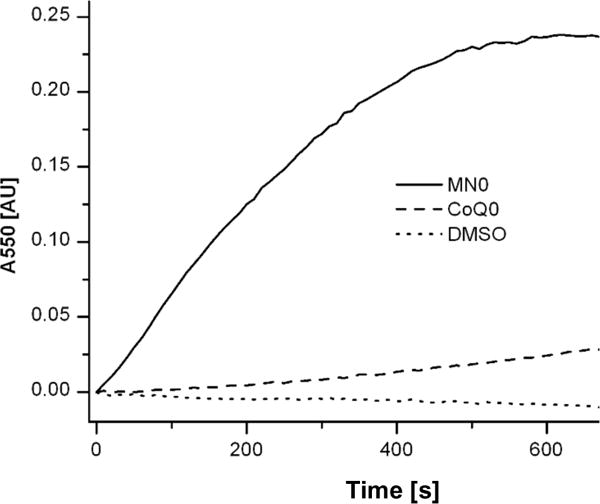

CidC couples to the respiratory chain via menaquinone

E. coli pyruvate:quinone oxidoreductase, PoxB, transfers electrons directly into the electron transport chain via ubiquinone48,49. Similarly, C. glutamicum pyruvate oxidase reduces menaquinone-9. Like other gram-positive bacteria, S. aureus only possesses menaquinone, so we speculated that CidC would be able to pass electrons to menaquinone. To test this, the most soluble forms of menaquinone and ubiquinone, menadione (MN0) and CoenzymeQ0 (CoQ0), respectively, were used as electron acceptors in this experiment. MN0 and CoQ0 have the exact same head groups compared with their counterparts, but vary only in the hydrophobic chains, which function as membrane anchors. In addition, cytochrome C was used as an artificial electron acceptor in this experiment, where its reduction can be monitored by following the change in absorbance at A550 over time. As shown in Fig. 7, efficient electron transfer was only observed with MN0 (cytochrome C was completely reduced within 10 minutes of the start of the reaction) while very little transfer was observed via CoQ0 or in the absence of any quinone. Kinetics studies demonstrated that CidC has the highest affinity (0.7 mM) and turnover rate (0.26 s−1) for pyruvate at pH 5.6 and 6.0 using MN0 as an electron receptor. In contrast, CoQ0 has a much lower affinity (2.54 mM) and lower turnover rate (0.05 s−1). Compared with the previous ferricyanide experiment, CidC has a much higher specificity, but a much lower turnover rate, for menadione due to the fact that there are multiple electron transfer steps happening in the menadione/cytochrome C assays and we are only measuring the overall turnover rate for these reactions. These results suggest that CidC can participate in the S. aureus respiratory chain via menaquinone.

Figure 7. Quinone reduction by CidC.

Electron transport by CidC to cytochrome c via MN0, CoQ0 or DMSO (control) was investigated. The oxidation state of cytochrome c was measured via A550 and is plotted as the change from its oxidized state.

Discussion

The extensively studied PoxB pyruvate:ubiquinone oxidoreductase from E. coli directly shuffles electrons from the cytoplasm to the membrane-bound mobile carrier ubiquinone of the electron transport chain where it converts pyruvate to acetate. PoxB is inactive within the cytoplasm where the C-terminus sterically hinders the active site from both the pyruvate substrate and the ubiquinone electron acceptor25,45,50,51. PoxB becomes active in vivo by binding to the membrane via this C-terminal domain, which undergoes a structural rearrangement exposing the active binding site to the solvent and activating the enzyme by two orders of magnitude (affecting both turnover and pyruvate affinity). This behavior can be reproduced in vitro by binding to artificial phospholipid membranes and detergent micelles, or by proteolytic cleavage of the C-terminus25. This current in vitro study reveals novel insights into the CidC protein from S. aureus, which differs from PoxB in some aspects. CidC is also a membrane-bound protein; however, it is only modestly activated by binding to artificial membranes or by proteolytic cleavage, which increases its activity by only a factor of about three. This behavior may be explained by a slightly different structure of CidC where the C-terminus may not inhibit solvent access to the active site in the membrane-free form of the protein. CidC is able to efficiently pass electrons to menaquinone, the quinone found within the S. aureus membranes, which lack ubiquinone, and thus could actively participate in the electron transport chain. CidC is active under conditions slightly more acidic than pH 6.5 and is largely inactive at pH 7 to 8, most likely due to its inability to bind the TPP cofactor at neutral pH. This is in contrast to POX, which retains about 50% and 20% of its activity at pH 7 and pH 8, respectively30. CidC, therefore, appears to be intrinsically “activated” only when the cytoplasm becomes sufficiently acidic, at which point it could further contribute to intracellular acidification by generating acetate. Thus, these findings are consistent with our previous finding that cytoplasmic acidification is important in the induction of bacterial PCD and the role of the CidC protein in this process16.

One of the major hurdles that we encountered in this study was the propensity of CidC to precipitate under its optimum working pH. We employed multiple approaches to overcome this, including the use of different buffer formulations (altered buffer, salt, mild detergent, amino acids…) to stabilize CidC at acidic pH. We also tried adding TPP and pyruvate to the CidC sample to determine if these molecules effected precipitation. Given that all of these conditions failed, we hypothesize that active CidC may require some significant conformational change that exposes a highly charged domain and leads to precipitation. Also, the fact that CidC precipitates at its optimum working pH (by itself, with TPP, pyruvate and membranes) might be due to the possibility that CidC has one or more binding partners (proteins) in vivo. Recent studies by Chaudhari et al. (2016)3,12 suggests that CidC may interact with the CidA and CidB proteins at the membrane. Thus, these results may indicate that CidC is normally present within one or more multi-protein complexes that serve to simultaneously regulate its activity and stabilize it.

Our laboratory has recently demonstrated the role of cidC and cytoplasmic acidification in bacterial cell death: stationary phase death was found to be dependent on CidC-generated acetate and, subsequently, extracellular acetic acid which, in the protonated and uncharged form, freely passes across the cytoplasmic membrane where it then disassociates and acidifies the cytoplasm16. As in eukaryotic cells undergoing apoptosis52,53, death in S. aureus under these conditions was shown to be associated with the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and diminished when the production of these reactive molecules was limited16. It was also demonstrated that the physiological features that accompany the metabolic activation of cell death are strikingly similar to the hallmarks of eukaryotic apoptosis, including ROS generation and DNA fragmentation. Although the cidC gene is co-expressed with cidA, previously shown to be involved in the control of PCD in S. aureus, there is currently limited information about the potential interactions between these proteins. Recently, we demonstrated that the association of CidC with the membrane, as well as CidC-induced acetate generation, is promoted by CidB. On the other hand, the presence of CidA inhibits the membrane localization of CidC12. The functions of these proteins in PCD may therefore be interdependent, and current investigations in our laboratory are exploring this possibility.

Another important finding of this study was that CidC converts pyruvate to acetate and is likely to transfer electrons directly to menaquinone during this process. These results are consistent with previous studies in our laboratory15 and indicate that CidC may be more accurately described as a pyruvate:menaquinone oxidoreductase, rather than a pyruvate oxidase as was previously presumed based on the close sequence alignment of these two classes of enzymes. Interestingly, pyruvate:oxygen 2-oxidoreductases have also been shown to be involved in cell death in the organisms that produce them. For example, the well-described death of Streptococcus pneumoniae in stationary phase has been shown to be dependent on the expression of the spxA gene encoding a pyruvate:oxygen 2-oxidoreductase, which generates hydrogen peroxide and induces cell death23. Thus, despite catalyzing distinct enzymatic reactions with different metabolic end-products, both enzymes appear to play major roles in the induction of bacterial cell death.

In summary, the results of the current study provide important new details of the CidC activity previously shown to be involved in the generation of acetate and the potentiation of PCD. This will be particularly important as we explore the possible interactions of CidC with CidA and/or CidB and will be critical as we dissect the molecular mechanisms underlying bacterial cell death.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank Dr. Luis A. Marky for help with the ITC experiments and Dr. Vinai C. Thomas for help with the acetate measurements and discussions of the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants P01-AI83211 (K.W.B) and R01-AI125589 (K.W.B.).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

X.Z. carried out the experiments; X.Z. and S.L. conceived the experiments; K.W.B., X.Z. and S.L. wrote the manuscript.

Supporting Information

Reaction products of and co-factors associated with the S. aureus pyruvate:menaquinone oxidoreductase enzyme

REFERENCES CITED

- 1.Yang SJ, Rice KC, Brown RJ, Patton TG, Liou LE, Park YH, Bayles KW. A LysR-type regulator, CidR, is required for induction of the Staphylococcus aureus cidABC operon. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:5893–5900. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.17.5893-5900.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rice KC, Nelson JB, Patton TG, Yang S, Bayles KW. Acetic acid induces expression of the Staphylococcus aureus cidABC and lrgAB murein hydrolase regulator operons. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:813–821. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.3.813-821.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Groicher KH, Firek BA, Fujimoto DF, Bayles KW. The Staphylococcus aureus lrgAB operon modulates murein hydrolase activity and penicillin tolerance. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1794–1801. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.7.1794-1801.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pang X, Moussa SH, Targy NM, Bose JL, George NM, Gries C, Lopez H, Zhang L, Bayles KW, Young R, Luo X. Active Bax and Bak are functional holins. Genes Dev. 2011;25:2278–2290. doi: 10.1101/gad.171645.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rice KC, Firek BA, Nelson JB, Patton TG, Bayles KW, Yang S. The Staphylococcus aureus cidAB Operon : Evaluation of Its Role in Regulation of Murein Hydrolase Activity and Penicillin Tolerance. 2003;185:2635–2643. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.8.2635-2643.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mann EE, Rice KC, Boles BR, Endres JL, Ranjit D, Chandramohan L, Tsang LH, Smeltzer MS, Horswill AR, Bayles KW. Modulation of eDNA release and degradation affects Staphylococcus aureus biofilm maturation. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5822. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rice KC, Bayles KW. Molecular control of bacterial death and lysis. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2008;72:85–109. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00030-07. table of contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bayles KW. Bacterial programmed cell death: making sense of a paradox. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;12:63–69. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rice KC, Mann EE, Endres JL, Weiss EC, Cassat JE, Smeltzer MS, Bayles KW. The cidA murein hydrolase regulator contributes to DNA release and biofilm development in Staphylococcus aureus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:8113–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610226104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang IN, Smith DL, Young R. Holins: the protein clocks of bacteriophage infections. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2000;54:799–825. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ranjit DK, Endres JL, Bayles KW. Staphylococcus aureus CidA and LrgA proteins exhibit holin-like properties. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:2468–2476. doi: 10.1128/JB.01545-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chaudhari SS, Thomas VC, Sadykov MR, Bose JL, Ahn DJ, Zimmerman MC, Bayles KW. The LysR-type transcriptional regulator, CidR, regulates stationary phase cell death in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol. 2016;101:942–953. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beltrame CO, Côrtes MF, Bonelli RR, de A Côrrea AB, Botelho AMN, Américo MA, Fracalanzza SEL, Figueiredo AMS. Inactivation of the Autolysis-Related Genes lrgB and yycI in Staphylococcus aureus Increases Cell Lysis-Dependent eDNA Release and Enhances Biofilm Development In Vitro and In Vivo. PLoS One (Msadek, T, Ed) 2015;10:e0138924. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang J, Bayles KW. Programmed cell death in plants: Lessons from bacteria? Trends Plant Sci. 2013;18:133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patton TG, Rice KC, Foster MK, Bayles KW. The Staphylococcus aureus cidC gene encodes a pyruvate oxidase that affects acetate metabolism and cell death in stationary phase. Mol Microbiol. 2005;56:1664–1674. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomas VC, Sadykov MR, Chaudhari SS, Jones J, Endres JL, Widhelm TJ, Ahn JS, Jawa RS, Zimmerman MC, Bayles KW. A central role for carbon-overflow pathways in the modulation of bacterial cell death. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004205. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knappe J, Blaschkowski HP, Grobner P, Schmitt T. Pyruvate Formate-Lyase of Escherichia coli : the Acetyl-Enzyme Intermediate. 1974;263:253–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1974.tb03894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arjunan P, Nemeria N, Brunskill A, Chandrasekhar K, Sax M, Yan Y, Jordan F, Guest JR, Furey W. Structure of the pyruvate dehydrogenase multienzyme complex E1 component from Escherichia coli at 1.85 A resolution. Biochemistry. 2002;41:5213–5221. doi: 10.1021/bi0118557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abdel-Hamid AM, Attwood MM, Guest JR. Pyruvate oxidase contributes to the aerobic growth efficiency of Escherichia coli. Microbiology. 2001;147:1483–1498. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-6-1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sedewitz B, Schleifer KH, Gotz F. Purification and Biochemical Characterization of Pyruvate Oxidase from Lactobacillus plantarum. 1984;160:273–278. doi: 10.1128/jb.160.1.273-278.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schreiner ME, Eikmanns BJ. Pyruvate:quinone oxidoreductase from Corynebacterium glutamicum: purification and biochemical characterization. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:862–871. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.3.862-871.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolfe AJ. The acetate switch. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2005;69:12–50. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.69.1.12-50.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Regev-Yochay G, Trzcinski K, Thompson CM, Lipsitch M, Malley R. SpxB is a suicide gene of Streptococcus pneumoniae and confers a selective advantage in an in vivo competitive colonization model. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:6532–6539. doi: 10.1128/JB.00813-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goffin P, Muscariello L, Lorquet F, Stukkens A, Prozzi D, Sacco M, Kleerebezem M, Hols P. Involvement of pyruvate oxidase activity and acetate production in the survival of Lactobacillus plantarum during the stationary phase of aerobic growth. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:7933–7940. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00659-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neumann P, Weidner A, Pech A, Stubbs MT, Tittmann K. Structural basis for membrane binding and catalytic activation of the peripheral membrane enzyme pyruvate oxidase from Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:17390–17395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805027105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muller YA, Schumacher G, Rudolph R, Schulz GE. The refined structures of a stabilized mutant and of wild-type pyruvate oxidase from Lactobacillus plantarum. J Mol Biol. 1994;237:315–335. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chaudhari SS, Thomas VC, Sadykov MR, Bose JL, Ahn DJ, Zimmerman MC, Bayles KW. The LysR-type transcriptional regulator, CidR, regulates stationary phase cell death in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol. 2016;101:942–953. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tittmann K, Golbik R, Ghisla S, Hübner G. Mechanism of elementary catalytic steps of pyruvate oxidase from Lactobacillus plantarum. Biochemistry. 2000;39:10747–54. doi: 10.1021/bi0004089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trinder P. Determination of blood glucose using an oxidase-peroxidase system with a non-carcinogenic chromogen. J Clin Pathol. 1969;22:158–161. doi: 10.1136/jcp.22.2.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sedewitz B, Schleifer KH, Gotz F. Purification and biochemical characterization of pyruvate oxidase from Lactobacillus plantarum. J Bacteriol. 1984;160:273–278. doi: 10.1128/jb.160.1.273-278.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brocklehurst K, Dixon HB. PH-dependence of the steady-state rate of a two-step enzymic reaction. Biochem J. 1976;155:61–70. doi: 10.1042/bj1550061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Risse B, Stempfer G, Rudolph R, Möllering H, Jaenicke R. Stability and reconstitution of pyruvate oxidase from Lactobacillus plantarum: dissection of the stabilizing effects of coenzyme binding and subunit interaction. Protein Sci. 1992;1:1699–1709. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560011218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang YY, Cronan JE. An Escherichia coli mutant deficient in pyruvate oxidase activity due to altered phospholipid activation of the enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81:4348–4352. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.14.4348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mather M, Blake R, Koland J, Schrock H, Russell P, O’Brien T, Hager LP, Gennis RB, O’Leary M. Escherichia coli pyruvate oxidase: interaction of a peripheral membrane protein with lipids. Biophys J. 1982;37:87–88. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(82)84613-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schrock HL, Gennis RB. High affinity lipid binding sites on the peripheral membrane enzyme pyruvate oxidase. Specific ligand effects on detergent binding. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:5990–5995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Russell P, Schrock HL, Gennis RB. Lipid activation and protease activation of pyruvate oxidase. Evidence suggesting a common site of interaction on the protein. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:7883–7887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Short SA, White DC. Metabolism of phosphatidylglycerol, lysylphosphatidylglycerol, and cardiolipin of Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1971;108:219–226. doi: 10.1128/jb.108.1.219-226.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kilelee E, Pokorny A, Yeaman MR, Bayer AS. Lysylphosphatidylglycerol attenuates membrane perturbation rather than surface association of the cationic antimicrobial peptide 6W-RP-1 in a model membrane system: implications for daptomycin resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:4476–4479. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00191-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blake R, Hager LP. Activation of pyruvate oxidase by monomeric and micellar amphiphiles. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:1963–1971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grabau C, Cronan JE. Molecular cloning of the gene (poxB) encoding the pyruvate oxidase of Escherichia coli, a lipid-activated enzyme. J Bacteriol. 1984;160:1088–1092. doi: 10.1128/jb.160.3.1088-1092.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grabau C, Cronan JE. In vivo function of Escherichia coli pyruvate oxidase specifically requires a functional lipid binding site. Biochemistry. 1986;25:3748–3751. doi: 10.1021/bi00361a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morey AV, Juni E. Studies on the nature of the binding of thiamine pyrophosphate to enzymes. J Biol Chem. 1968;243:3009–3019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kulshina N, Edwards TE, Ferré-D’Amaré AR. Thermodynamic analysis of ligand binding and ligand binding-induced tertiary structure formation by the thiamine pyrophosphate riboswitch. RNA. 2010;16:186–196. doi: 10.1261/rna.1847310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Muller YA, Schulz GE. Structure of the thiamine- and flavin-dependent enzyme pyruvate oxidase. Science. 1993;259:965–967. doi: 10.1126/science.8438155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Recny MA, Hager LP. Isolation and characterization of the protease-activated form of pyruvate oxidase. Evidence for a conformational change in the environment of the flavin prosthetic group. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:5189–5195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Recny MA, Grabau C, Cronan JE, Hager LP. Characterization of the α-peptide released upon protease activation of pyruvate oxidase. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:14287–14291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Russell P, Hager LP, Gennis RB. Characterization of the proteolytic activation of pyruvate oxidase. Control by specific ligands and by the flavin oxidation-reduction state. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:7877–7882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carter K, Gennis RB. Reconstitution of the ubiquinone-dependent pyruvate oxidase system of Escherichia coli with the cytochrome o terminal oxidase complex. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:10986–10990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koland JG, Miller MJ, Gennis RB. Reconstitution of the membrane-bound, ubiquinone-dependent pyruvate oxidase respiratory chain of Escherichia coli with the cytochrome d terminal oxidase. Biochemistry. 1984;23:445–453. doi: 10.1021/bi00298a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cunningham CC, Hager LP. Reactivation of the lipid-depleted pyruvate oxidase system from Escherichia coli with cell envelope neutral lipids. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:7139–7146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mather MW, Gennis RB. Spectroscopic studies of pyruvate oxidase flavoprotein from Escherichia coli trapped in the lipid-activated form by cross-linking. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:10395–10397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Simon HU, Haj-Yehia A, Levi-Schaffer F. Role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in apoptosis induction. Apoptosis. 2000;5:415–418. doi: 10.1023/a:1009616228304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Granot D, Levine A, Dor-Hefetz E. Sugar-induced apoptosis in yeast cells. FEMS Yeast Res. 2003;4:7–13. doi: 10.1016/S1567-1356(03)00154-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.