Abstract

Background/Objective

Patients discharged from hospitals to Skilled Nursing Facilities (SNFs) are at increased risk of transitioning to long term care nursing homes. We investigated how the risk of subsequent long term care residence varies across SNFs and the SNF characteristics associated with this risk.

Design

Population-based national cohort study with patients nested in both SNFs and hospitals in a cross-classified multilevel model.

Setting

6680 SNFs

Participants

Fee-for-service Medicare patients (n=552,414) discharged from a hospital to a SNF in 2013.

Measurements

Patient characteristics from Medicare data and the Minimum Data Set. SNF characteristics from Medicare and Nursing Home Compare. Outcome was stay of ≥90 days in a long term care nursing home within six months of SNF admission.

Results

Within six months of SNF admission, 10.4% of patients resided in long term care. After adjustments for patient characteristics, the SNF where a patient received care explained 7.9% of the variance in risk of long term care, while the prior hospital explained 1.0%. Patients in SNFs with excellent quality ratings had 22% lower odds of transitioning to long term care compared to those in SNFs with poor ratings (OR=0.78, 95% CI=0.74, 0.84). The variation among SNFs and the association with quality markers were increased in sensitivity analyses limited to patients least likely to require long term care. Results were essentially unchanged in a number of other sensitivity analyses designed to reduce potential confounding.

Conclusions and Relevance

Risk of subsequent long term care, an important and negatively viewed outcome for older patients, varies substantially across SNFs. Patients in higher quality SNFs have lower risk.

Keywords: Nursing home, Skilled Nursing Facility, Outcomes of Care, Post-Acute Care

Introduction

Skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) provide additional rehabilitation and recovery after hospital discharge and prior to return home. Concerns have been raised about the uneven quality of SNF services and the substantial differences in utilization across locales.1 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) provides overall ratings (one to five stars) for SNFs based on health inspections, quality measures, and hours of care provided.2

We previously reported that most new placements in long term care nursing homes were preceded by a hospitalization, followed by a SNF stay.3 The goal of SNF care is to provide post-acute services so that patients can return to the community.1,2 From that perspective, transfer to long term care represents a failure to achieve this goal. Residence in long term care is one of the most negatively viewed outcomes of community-dwelling older adults.4–8

The purpose of this study was to examine residence in long term care as an outcome of post-hospital SNF care. We assessed whether SNFs varied in their patients’ risk of transitioning to long term care. We also assessed whether SNF characteristics were associated with their patients’ risk of subsequent long term care, with a specific focus on CMS quality ratings. Because we were interested in teasing out the specific contribution of the SNF along the hospital to SNF to long term care pathway, we controlled for the contribution of individual patient characteristics and the hospital where the patient originally received care.

Methods

Source of Data

Data for analyses were from the following sources: 1) Medicare Part A Claims from 2012 to 2015 for 100% of US Medicare beneficiaries, 2) characteristics of SNF residents from the 2012 to 2015 Resident Assessment Instrument Minimum Data Set (MDS 3.0); 3) Skilled Nursing Home facility characteristics from Provider of Services Files; the Nursing Home Compare (NHC) Five-Star Quality Rating, Provider and Deficiency files; and the Online Survey, Certification and Reporting (OSCAR).9 A data use agreement (DUA) was obtained from CMS. The research was approved by the UTMB Institutional Review Board.

Study Cohort

The cohort selection process is outlined in Supplementary Figure S1. This resulted in a cohort of 552,414 patients discharged from a hospital to 6,680 SNFs in 2013 for which we had complete information on patient and SNF characteristics. We created a similar cohort from 2014 (n=558,159) to compare stability in the results over time. We also created cohorts for a number of sensitivity analyses that are described in the Supplementary Tables that present the results of those analyses.

SNF Characteristics

Whether the SNF also had long term care beds, ownership (non-profit, profit, public), bed size, and location (urban/rural) were obtained from the Provider of Service files. The occupancy rates of certified beds for each facility in 2013 were obtained from OSCAR data.9 The five star ratings and the individual components of those ratings were obtained from NHC Ratings files.

SNF Patient Characteristics

The association of SNF patient characteristics with risk of subsequent institutionalization in long term care was reported in a previous publication.10 These characteristics are included in this study to control for differences in case mix among SNFs, and include demographic characteristics, distance to the SNF from the patient’s home, income, Medicaid eligibility, information from the prior hospitalization, and the results of the initial assessment in the MDS on marital status, mood, cognitive and functional status, prognosis, hallucinations/delusions, use of catheters or ostomy, pressure ulcers, respirator, insulin injections, oxygen therapy, cancer treatment, tracheostomy care, intravenous medication, blood transfusion, dialysis, and hospice care (Supplementary Table S1).10–12

Study Outcomes

The outcome was residence in a long term care nursing home within six months after discharge from a hospital to a SNF, with a total stay in long term care of at least 90 days. We based our identification of long term care on a method developed by Intrator et al.,13 defining a long term care nursing home stay as any MDS episode outside the SNF stay identified in the MedPAR files. This method has 79% sensitivity and 88% positive predictive value in identifying long term care stays among SNF patients when validated against Medicaid data.14 In a sensitivity analysis, we restricted the outcome to a direct transfer from a SNF to a long term care bed, with no intervening hospitalizations, further SNF stays, etc. We did not use the CMS method to identify long term care because it is based only on length of stay (>100 days) and does not distinguish between SNF days and long term care days14.

Statistical Analyses

We constructed cross-classified multilevel models15 to disentangle the influence of hospital and SNF on long term care admission. The models are not hierarchical, and allow patients to be clustered within both hospitals and SNFs in a situation where a hospital discharges patients to many SNFs and a SNF receives patients from many hospitals. We added patient-level characteristics and the state where the SNF was located as fixed effects. We also added SNF characteristics to the model to assess their association with the outcome after adjustment for patient-level characteristics, the hospital, and state. We did not include bed size as a SNF characteristic because of the strong correlation with whether the SNF had long term care beds (r= 0.69), but we included it in a sensitivity analysis limited to patients in SNFs with long term care beds. We calculated intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) to estimate the degree of variation among hospitals and among SNFs in the odds of long term care admission.16 All analyses were performed with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

The 552,414 patients in the sample were discharged from 3,722 hospitals to 6,680 SNFs in 2013. Hospitals discharged patients to an average of 14.5 SNFs (median = 8; interquartile range = 3, 19). Conversely, SNFs received patients from an average of 8.1 hospitals (median = 7; interquartile range = 5, 10). The overall rate of patients who transitioned to long term care beds within 90 days of a hospital discharge to a SNF was 10.4%.

We have previously published analyses of patient characteristics associated with new institutionalization in long term care after hospital discharge to a SNF.10 Similar analyses for this cohort are presented in Supplementary Table S1. We then controlled for all the characteristics in Supplementary Table S1 as well as for the hospital where the patient originally received care and the state where the SNF was located in the analyses presented below.

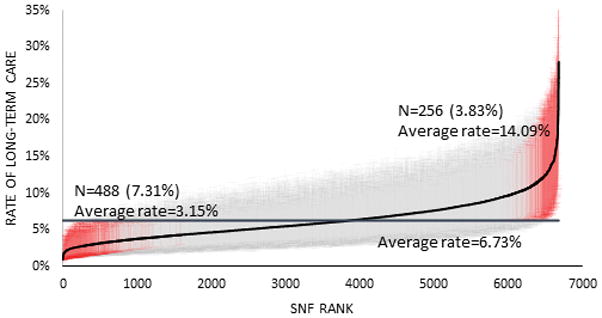

Figure 1 shows the variation among SNFs in the adjusted rates of their patients who transition to long term care. SNFs are ranked from lowest to highest long term care rates. Those SNFs with rates significantly higher or lower than the average adjusted rate are indicated in red. Of all SNFs, 256 (3.8%) had significantly higher rates, with a mean adjusted rate of 14.1%, and 488 SNFs (7.3%) had significantly lower rates, with a mean adjusted rate of 3.2%.

Figure 1.

Ranking of Skilled Nursing Facilities (SNFs) by the percent of their patients transitioning to long term care within six months of SNF admission, from a cross classification multilevel model including patient, hospital and SNF, and adjusted for patient characteristics and the state where the SNF was located, for patients admitted to SNFs in 2013. SNFs are ranked from the lowest to the highest long term care rates. The 95% confidence intervals are indicated with a vertical line. SNF adjusted rates that are significantly different from the mean adjusted rate are indicated as red.

We tested the stability of those adjusted rates over time by comparing long term care rates for SNFs in 2013 with their rates in 2014 (Supplementary Figure S2). These analyses were limited to the 6692 SNFs with ≥25 eligible patients in each year. The correlation between the two sets of rates was 0.67. We categorized the SNFs by quintile of adjusted long term care rates in each year (Table 1). Of the SNFs in the highest (first) quintile of long term care rates in 2013, 74.4% were in the first (49.0%) or second (25.3%) quintile in 2014. Similarly, of the SNFs in the lowest (fifth) quintile in 2013, 69.9% were in the fourth or fifth quintile in 2014. Of the 418 SNFs with significantly lower than average rates in 2013, the average long term care rate was 3.1% in 2013 and 4.2% in 2014. For the 206 SNFs with significantly higher than average long term care rates in 2013, the average rate was 14.1% in 2013 and 10.2% in 2014.

Table 1.

Comparison of 2013 and 2014 Skilled Nursing Facility (SNF) rates of patients’ subsequent institutionalization in long term care. Rates are from two cross classification multilevel models using data from 2013 or 2014 including patient, hospital and SNF, and adjusted for patient characteristics and SNF state. The rates are categorized by quintile, from lowest to highest risk of long term care, for each year. The numbers are the percent of SNFs in a specified quintile in 2013 that are also in the specified quintile in 2014.

| Quintile 2013 | Quintile 2014 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (lowest) | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 (highest) | |

| 1 (lowest) | 49.0% | 25.3% | 14.4% | 7.0% | 4.2% |

| 2 | 25.7% | 25.6% | 20.9% | 19.0% | 8.7% |

| 3 | 13.4% | 20.5% | 25.3% | 23.0% | 17.8% |

| 4 | 8.2% | 18.3% | 23.0% | 24.7% | 25.7% |

| 5 (highest) | 3.6% | 10.2% | 16.3% | 26.3% | 43.5% |

Table 2 presents the association of SNF characteristics with odds of a patient transitioning to long term care, generated from a cross-classified multilevel model that controls for patient characteristics, state, and the hospital where the patient received care prior to SNF admission. Two models are presented; the first includes the SNF five star rating and the second includes the three measures used to generate star ratings: inspections, quality measures, and staffing ratios. SNF characteristics associated with a higher risk of patients transitioning to long term care included co-location with long term care beds, higher occupancy rate, government ownership, and rural location.

Table 2.

The odds of SNF residents residing in a long term care nursing home six months after the SNF admission, by SNF characteristics, in 2013 Medicare data.

| SNF characteristics | N=6,680 SNFs |

Unadjusted % of patient in long term care nursing home within 6 months | Model 1* Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

Model 2* Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | ||||

| SNF/NF | 6,166 | 11.3 | 1.76 (1.64, 1.88) | 1.63 (1.51, 1.75) |

| SNF | 514 | 4.2 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Ownership | ||||

| Non-profit | 1,817 | 9.2 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Government | 224 | 14.7 | 1.38 (1.25, 1.51) | 1.36 (1.24, 1.50) |

| For profit | 4,639 | 10.7 | 0.90 (0.87, 0.94) | 0.88 (0.84, 0.91) |

| Occupancy rate | ||||

| Q1 (≤ 0.53) | 1,674 | 8.1 | 0.92 (0.88, 0.98) | 0.94 (0.87, 0.99) |

| Q2 (> 0.53; ≤ 0.65) | 1,685 | 9.8 | 0.92 (0.87, 0.96) | 0.92 (0.88, 0.97) |

| Q3 (> 0.65; ≤ 0.75) | 1,690 | 11.1 | 0.95 (0.90, 0.99) | 0.95 (0.91, 0.99) |

| Q4 (>0.75) | 1,631 | 12.7 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Location | ||||

| Urban | 5,260 | 9.7 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Rural | 1,420 | 14.0 | 1.20 (1.15, 1.26) | 1.20 (1.15, 1.26) |

| Overall rating | ||||

| Poor | 728 | 14.9 | 1.00 | |

| Below average | 1,244 | 12.9 | 0.91 (0.85, 0.96) | |

| Average | 1,329 | 11.1 | 0.88 (0.82, 0.93) | |

| Above Average | 1,917 | 10.0 | 0.85 (0.80, 0.90) | |

| Excellent | 1,415 | 7.9 | 0.78 (0.74, 0.84) | |

| Health inspection rating** | ||||

| Poor | 1,149 | 13.1 | 1.00 | |

| Below average | 1,494 | 11.2 | 0.91 (0.86, 0.96) | |

| Average | 1,599 | 10.6 | 0.89 (0.84, 0.94) | |

| Above Average | 1,666 | 9.6 | 0.89 (0.84, 0.94) | |

| Excellent | 725 | 7.7 | 0.84 (0.79, 0.90) | |

| Quality rating ** | ||||

| Poor | 337 | 10.4 | 1.00 | |

| Below average | 856 | 10.8 | 1.03 (0.94, 1.12) | |

| Average | 1,435 | 10.8 | 1.00 (0.92, 1.09) | |

| Above Average | 2,451 | 10.7 | 0.96 (0.89, 1.04) | |

| Excellent | 1,553 | 9.6 | 0.94 (0.87, 1.03) | |

| Staffing rating ** | ||||

| Poor | 656 | 15.3 | 1.00 | |

| Below average | 951 | 12.8 | 0.93 (0.87, 1.00) | |

| Average | 1,405 | 12.2 | 0.95 (0.89, 1.01) | |

| Above Average | 2,862 | 10.0 | 0.92 (0.87, 0.98) | |

| Excellent | 705 | 5.6 | 0.75 (0.69, 0.81) | |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; SNF, Skilled Nursing Facility

Model 1 and 2 both include all the patient characteristics included in Supplementary Table S1, along with the state where the SNF was located and the Elixhauser comorbidities and MDC-DRG, all entered individually.

Health Inspections rating are based on the number, scope, and severity of deficiencies identified from the last 3 years of onsite inspections, as well as substantiated findings from the most recent 36 months of complaint investigations.

The quality measure rating has information on 10 different physical and clinical measures for nursing home residents. The QMs offer information about how well nursing homes are caring for their residents’ physical and clinical needs.

Staffing – The staffing rating has information about the number of hours of care provided on average to each resident each day by nursing staff. This rating considers differences in the levels of residents’ care need in each nursing home.

There were clear stepwise relationships between odds of long term care and the quality ratings. Compared to SNFs with overall poor ratings, patients in SNFs with excellent ratings had 22% lower odds of transitioning to long term care (OR= 0.78; 95% CI: 0.74, 0.84). When the CMS ratings were separated into their three components, both staffing ratios and inspections were strongly related to long term rates, with quality measures less strongly related.

Table 3 shows the amount of variation in long term care rates attributable to the individual SNFs and to the hospital where the patient received care prior to SNF admission. The variances are expressed as ICCs generated from cross–classified multilevel models that allow for clustering of patients within SNFs and within hospitals in the same model. In the null model, 11.5% of the variance in odds of long term care was attributable to the SNF and 4.4% to the hospital. When all the patient characteristics (Supplementary Table S1) and SNF location were added, the percent of variance attributable to the SNF and hospital decreased to 7.9% and 1.0%, respectively. Adding SNF characteristics resulted in further reductions in variation at the SNF level to 6.8%. The C-statistics for the models are also given, and all are >0.85.

Table 3.

Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICCs) and C statistics for cross classification multilevel models presented in Table 2 and Figure 1.

| Model | ICC | C statistics |

|---|---|---|

| Null model | Variation among SNF: 11.5% Variation among hospitals: 4.40% |

- |

| Model with patient characteristics and SNF state | Variation among SNF: 7.90% Variation among hospitals: 0.96% |

0.86 |

| Model with patient characteristics, SNF state and SNF characteristics | Variation among SNF: 6.89% Variation among hospitals: 0.92% |

0.86 |

Abbreviations: SNF, Skilled Nursing Facility

We conducted several sensitivity analyses. In one, we restricted the cohort to post-surgical patients with normal cognition, no depression and no behavioral disorders. This represented 16% of the overall cohort and included the types of patients generally desired by SNFs and at low risk for long term care. 17 As shown in Supplementary Table S2, the association of SNF quality scores with risk of long term care was stronger, (OR=0.40 for SNFs with 5 vs. 1 Star) and the variation among SNFs was greater (ICC=14.1% vs. 7.9% in the main analysis). Other sensitivity analyses stratifying patients by Medicaid eligibility (Supplementary Table S3) or limiting the cohort to patients in SNFs that have long term care beds (Supplementary Table S4) yielded similar results to those in the main analyses.

We also repeated the analyses restricted to patients who were transferred directly from the initial SNF admission to a long term care bed without an intervening stay in another institution (hospital, SNF, etc.). As shown in Supplementary Figure S3 and Supplementary Table S5, the SNF quality scores are more strongly associated with transfer to long term care and the amount of variation attributable to SNFs was higher than in the main analyses. A final sensitivity analysis included all patients discharged to SNFs whether or not they survived six months. The results of the analysis were similar to the main analyses (Supplementary Table S6).

Discussion

Residence in long term care is an important health outcome and has been the topic of several systematic reviews.18–20 These reviews focused primarily on person-level characteristics. None of the systematic reviews reported information regarding the use of SNF or other post-acute care services. Also, many prior studies on risk of nursing home admission did not distinguish between short term SNF and long term care nursing homes stays when assessing risk of “nursing home” admission.

Older adults and their families are sometimes faced with difficult decisions about whether they can continue to live at home. Such decisions are often precipitated by a hospitalization, with accompanying deconditioning, followed by a SNF stay.3, 21 The loss of function may require the 24-hour care provided by a long term care nursing home. However, the variation in long term care rates among SNFs suggests that transfer to long term care also reflects practices specific to SNFs. SNFs vary in their ability to restore function in patients after hospitalization.21 As shown in Table 2, patients in higher quality SNFs were less likely to transition to long term care, possibly because of better functional recovery in those SNFs. When the five star SNF rating was deconstructed into its three components, we found that staffing ratios and inspections were most closely associated with the long term care rate. It is reasonable to believe that more nursing staff per patient would result in fuller recovery and lower risks of long term care. SNFs also vary in outcomes such as mortality and readmission rates, which are also associated with quality ratings, though more weakly than the association with long term care rates.22–24

Other SNF characteristics associated with higher long term care risk include having long term care beds in the same facility, lower occupancy rate and rural location. The first two reflect availability of open long term care beds. Higher rates in rural SNFs may reflect fewer available options to institutional long term care, such as home health services and day care.

The choice to transfer to long term care from SNF care may also have discretionary components, and may reflect local practice patterns and attitudes. As noted by Buntin et al.,21 “it may be too easy to keep SNF patients where they are and simply convert them from Medicare to a different payor.”

The issue of decision-making in post-acute care is important and has received inadequate attention, given the variations in practice. In a recent qualitative study, Burke and colleagues 25 asked hospital-based clinicians how they selected patients for SNF transfer. The clinicians admitted to lack of knowledge of SNF care practices, quality, or patient outcomes. There was felt to be no standardized process for selecting patients for discharge to SNFs.25 Patients and family members report feeling rushed to decide, often informed only on the day of discharge.26 SNF staff report poor communication from the hospital on patient needs, which may result in mismatching patients and facilities, increasing chances of a poor outcome.17

Medicaid spending on institutional versus community-based long term care services varies widely across states,27 as do long term care rates after hospitalization.10, 28 In the current analysis, we show that individual SNFs explain 7.9% of the variance in risk of subsequent new long term care nursing home residence after controlling for the state and hospital, as well as the functional, cognitive and emotional status of patients, and their medical diagnoses. The variation (ICC) was even greater, at 10.5%, when we limited the outcome to patients directly transferred from the initial SNF admission to long term care. This is presumably the situation over which the SNF would have the most control. This is an unusually high degree of variation in an outcome attributable to facilities.29 For example, 30-day readmission rates are an established quality marker, but the amount of variation in 30-day readmission rates explained by hospitals is less than 2%.30, 31

CMS recently introduced rate of discharge to the community as a quality measure relevant to multiple post-acute care settings.12 However, there is concern that the community discharge rate is inaccurate and subject to manipulation.32 In additional analyses, we assessed the correlation between a SNF’s community discharge rate and its long term care rate (r= -0.45) or rate of direct transfer to long term care (r= -0.42).

Our study has several limitations. We studied only Medicare fee-for service beneficiaries and persons 66 years and older. Medicare data may have limitations related to the completeness and accuracy of the information collected.33 While not specifically a limitation, we made the assumption that 90 days of long term residential care following discharge from a SNF is a negative outcome. We realize that, at the individual patient level, residential long term care may be the best option. It may be possible to make distinctions between preventable and non-preventable institutionalization, analogous to what has occurred with hospital readmission in acute care. In order to study long term care as an outcome of individual SNFs, we had to distinguish SNF patients from long term care nursing home residents. Our approach differs from the approach used by CMS to classify individuals in nursing homes as “short-stay” or “long-stay” for quality reporting. CMS considers individuals with lengths of stay greater than 100 days (SNF or long term care days) to be “long stays.” Also, some selection may occur in the hospital to SNF transition with more “desirable” patients who need short-term rehabilitation more likely to go to facilities with which the hospital has an established relationship.17, 34 Such selection could contribute to the association of long term care rates with quality scores. We addressed this issue by controlling for an extensive array of characteristics including demographics; functional status; comorbidities; the hospital and the reason for hospitalization; income; Medicaid eligibility; marital status; distance from patient’s residence to the SNF; bed size and occupancy rate of the SNF. We also repeated the analyses restricted to the 16% of patients that would generally be considered “desirable” by SNFs, that is, post-surgical patients with normal cognition, no depression and no behavioral disturbances. If selection biases exist, one might expect such a subgroup analyses to produce a weaker association between the risk of long term care and quality scores.35 In fact, the association between SNF quality scores and risk of long term care were considerably stronger in this subset of patients.

Conclusion

Our results indicate that patients’ risk of eventual placement in long term care nursing homes varies substantially among SNFs. Patients in higher quality SNFs have significantly lower risks of such placement. Further work on the SNF processes that explain this variation will contribute to the mandates of health care reform and guide efforts to help older adults successfully return to the community following hospitalization.

Supplementary Material

Percent of patients in a long term nursing home 6 months after discharge from a hospital to a SNF, by patient characteristics, with odds ratios from a cross classification multilevel analysis. This table shows the patient characteristics that are included in all the analytic models used in this paper. Also included in the models but not shown are 31 comorbidities.10

The odds of SNF residents (N=88,642) residing in a long term care nursing home six months after the SNF admission, by SNF characteristics, for surgical patients, excluding those with any behavioral problem (aggression and depression), hallucinations or delusions, or moderate or severe impaired cognition. *

The odds of SNF residents residing in a long term care nursing home six months after the SNF admission, by SNF characteristics, stratified by Medicaid eligibility of the patient.

The odds of SNF residents (N=481,909) residing in a long term care nursing home six months after the SNF admission, by SNF characteristics. The cohort was restricted to patients residing in SNF facilities that also have long term care beds.

The odds of SNF residents being directly transferred to a long term care nursing home within six months after the SNF admission, by SNF characteristics. The outcome in this analysis is direct transfer from a SNF bed to a long term care bed, without an intervening hospitalization, discharge home, or stay in another institution.

The odds of SNF residents (N=722,837) residing in a long term care nursing home six months after the SNF admission, by SNF characteristics. The cohort includes all patients admitted to SNFs. (The main analyses excluded patients who died within 6 months of SNF admission.)

Cohort Selection.

Adjusted long term care (LTC) rank for skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) in 2014, from a cross classification multilevel model adjusted by patient characteristics and SNF state. This is similar to the analysis in Figure 1, which used data from 2013.

Adjusted long term care (LTC) rank for skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) in 2013, from a cross classification multilevel model adjusted by patient characteristics and SNF state, for rate of patients directly transferred to long term care from the SNF.

Impact Statement.

We certify that this work is novel. It is the first to show that SNFs vary substantially in the risk of their patients transferring to long term care nursing home beds, and that patients in higher quality SNFs experience lower risk.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01-AG033134, P30-AG024832, R01-HD069443, R24-HD065702, and K05-CA134923), the National Institute of Disability and Rehabilitation Research (H033G140127), the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1R24HS022134), and the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (RP140020). Funders had no role in the study’s design, conduct, and reporting.

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors have none to disclose.

Sponsors’ Role

The sponsors had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collection, analysis or preparation of the paper.

Authors’ Role

Study concept and design: All authors. Acquisition of data: Goodwin. Analysis and interpretation of data: All authors. Preparation of the manuscript: Goodwin. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors. Statistical analysis: Li and Kuo. Obtained funding: Goodwin. Study supervision: Goodwin.

References

- 1.MEDPAC Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Skilled nursing facility services In: Report to the Congress. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission; Washington, DC: Mar, 2016. [Accessed July 7, 2017]. Available at: http://www.medpac.gov/documents/reports/mar16_entirereport.pdf?svrsn=0. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Medicare.gov. [Accessed September 12, 2017];Nursing Home Compare. Available at: www.Medicare.gov/nursinghomecompare.

- 3.Goodwin JS, Howrey B, Zhang DD, et al. Risk of continued institutionalization after hospitalization in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66:1321–1327. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tse MM. Nursing home placement: perspectives of community-dwelling older persons. J Clin Nurs. 2006;16:911–917. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krothe JS. Giving voice to elderly people: community-based long term care. Public Health Nurs. 1997;14:217–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.1997.tb00294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee DT, Woo J, Mackenzie AE. A review of older people’s experiences with residential care placement. J Adv Nurs. 2002;37:19–27. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prince D, Butler D. Clarity Final Report: Aging in Place in America. Nashville, TN: Prince Market Research; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schoenberg NE, Coward RT. Attitudes about entering a nursing home: comparisons of older rural and urban African-American women. J Ageing Stud. 1997;11:27–47. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed November 3. 2017];Online Survey, Certification and Reporting (OSCAR) 2013 Available at: https://www.ahcancal.org/research_data/oscar_data/Pages/WhatisOSCARData.aspx.

- 10.Middleton A, Li S, Kuo YF, et al. New Institutionalization in long term care after hospital discharge to skilled nursing facilities. J Am Geriat Soc. 2017 doi: 10.1111/jgs.15131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. [Accessed July 7, 2017];Assessments for the Resident Assessment Instrument (RAI). In Minimum data set, version 3.0 (MDS3.0) RAI Manual. 2015 Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/NursingHomeQualityInits/MDS30RAIManual.html.

- 12.MDS 3.0 Quality measures User’s Manual. (V 9.0, 08-15-2015) RTI International; [Accessed July 7, 2017]. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/NursingHomeQualityInits/Downloads/MDS-30-QM-Users-Manual-V90.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Intrator O, Hiris J, Berg K, et al. The residential history file: studying nursing home residents’ long-term care histories. Health Serv Res. 2010;46:120–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01194.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodwin JS, Li S, Zhou J, et al. Comparison of methods to identify long term care nursing home residence with administrative data. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:376. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2318-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rasbash J, Goldstein H. Efficient analysis of mixed hierarchical and cross-classified random structures using a multilevel model. J Educ Behav Stat. 1994;19:337–350. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koch GG. Intraclass correlation coefficient. In: Kotz S, Johnson NL, editors. Encyclopedia of Statistical Sciences. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1982. pp. 213–217. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shield R, Winblad U, McHugh J, Gadbois E, Tyler D. Choosing the best and scrambling for the rest: Hospital-nursing home relationships and admissions to post-acute care. J Appl Gerontol. 2018 Jan 1; doi: 10.1177/073346817752084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaugler JE, Duval S, Anderson KA, et al. Predicting nursing home admission in the U.S: A meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2007;7:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-7-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luppa M, Luck T, Weyerer S, et al. Prediction of institutionalization in the elderly: A systematic review. Age Ageing. 2010;39:31–38. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afp202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luppa M, Luck T, Weyerer S, et al. Gender differences in predictors of nursing home placement in the elderly: A systematic review. Inter Psychogeriatr. 2009;21:1015–1025. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209990238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buntin MB, Colla CH, Deb P, et al. Medicare spending and outcomes after postacute care for stroke and hip fracture. Med Care. 2010;48:776–784. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e359df. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pandolfi MM, Wang YY, Spenard A, et al. Associations between nursing home performance and hospital 30-day readmissions for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure and pneumonia at the healthcare community level in the United States. Int J Older People Nurs. 2017;12:e12154. doi: 10.1111/opn.12154. https://doi.org?10.1111/opn.12154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neuman MD, Wirtalla C, Werner RM. Skilled nursing facility quality indicators and hospital readmissions. JAMA. 2014;312:1542–1551. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.13513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Unroe KT, Greiner MA, Colon-Emeric C, Peterson ED, Curtis LH. Associations between published quality ratings of skilled nursing facilities and outcomes of Medicare beneficiaries with heart failure. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13:188.e1–188e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2011.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burke RE, Lawrence E, Ladebue A, et al. How hospital clinicians select patients for skilled nursing facilities. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017 Jul 6; doi: 10.1111/jgs.14954. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gadbouis EA, Tyler DA, Mor V. Selecting a skilled nursing facility for postacute care: Individual and family perspectives. JAGS. 2017;65:2459–2465. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eiken S, Sredl K, Burwell B, et al. [Accessed July 7, 2016];Medicaid Expenditure for Long-Term Services and Supports (LTSS) in FY 2014: Managed LTSS Reached 15 Percent of LTSS Spending. Available at: https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid-chip-program-information/by-topics/long-term-services-and-supports/downloads/ltss-expenditures-2014.pdf.

- 28.Middleton A, Zhou J, Ottenbacher KJ, et al. Hospital variation in rates of new institutionalizations within six months of discharge. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;66:1206–1213. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McGlynn EA, Adams JL. What makes a good quality measure? JAMA. 2014;312:1517–1518. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.12819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krumholz HM, Merrill AR, Schone EM, et al. Patterns of hospital performance acute myocardial infraction and heart failure 30-day mortality and readmission. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2:407–413. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.883256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh S, Lin YL, Kuo YF, et al. Variation in the risk of readmission among hospitals: the relative contribution of patient, hospital and inpatient provider characteristics. J Gen Int Med. 2014;29:572–578. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2723-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.MDS 3.0 Quality measures User’s Manual. (V 9.0, 08-15-2015) RTI International; [Accessed July 7, 2016]. [cited 2016 July 7]. Available from https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/NursingHomeQualityInits/Downloads/MDS-30-QM-Users-Manual-V90.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Walraven C, Austin P. Administrative database research has unique characteristics that can risk biased results. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65:126–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gilmore-Bykovskyi AL, Roberts TJ, King BJ, Kennelty KA, Kind A. Transitions from hospitals to skilled nursing facilities for persons with dementia: A challenging convergence of patient and system-level needs. Gerontologist. 2017;57:867–879. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wen SW, Hernandez R, Naylor CD. Pitfalls in nonrandomized outcomes studies. JAMA. 1995;274:1687–1961. doi: 10.1001/jama.274.21.1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Percent of patients in a long term nursing home 6 months after discharge from a hospital to a SNF, by patient characteristics, with odds ratios from a cross classification multilevel analysis. This table shows the patient characteristics that are included in all the analytic models used in this paper. Also included in the models but not shown are 31 comorbidities.10

The odds of SNF residents (N=88,642) residing in a long term care nursing home six months after the SNF admission, by SNF characteristics, for surgical patients, excluding those with any behavioral problem (aggression and depression), hallucinations or delusions, or moderate or severe impaired cognition. *

The odds of SNF residents residing in a long term care nursing home six months after the SNF admission, by SNF characteristics, stratified by Medicaid eligibility of the patient.

The odds of SNF residents (N=481,909) residing in a long term care nursing home six months after the SNF admission, by SNF characteristics. The cohort was restricted to patients residing in SNF facilities that also have long term care beds.

The odds of SNF residents being directly transferred to a long term care nursing home within six months after the SNF admission, by SNF characteristics. The outcome in this analysis is direct transfer from a SNF bed to a long term care bed, without an intervening hospitalization, discharge home, or stay in another institution.

The odds of SNF residents (N=722,837) residing in a long term care nursing home six months after the SNF admission, by SNF characteristics. The cohort includes all patients admitted to SNFs. (The main analyses excluded patients who died within 6 months of SNF admission.)

Cohort Selection.

Adjusted long term care (LTC) rank for skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) in 2014, from a cross classification multilevel model adjusted by patient characteristics and SNF state. This is similar to the analysis in Figure 1, which used data from 2013.

Adjusted long term care (LTC) rank for skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) in 2013, from a cross classification multilevel model adjusted by patient characteristics and SNF state, for rate of patients directly transferred to long term care from the SNF.