Abstract

Importance

Prognostication in advanced dementia is challenging but may influence care.

Objectives

To determine the accuracy of proxies’ prognostic estimates for nursing home (NH) residents with advanced dementia, identify factors associated with those estimates, and examine the association between their estimates and use of burdensome interventions.

Design

Data were combined from two studies which prospectively followed residents with advanced dementia and their proxies in Boston-area NHs for 12 months: 1. Study of Pathogen Resistance and Exposure to Antimicrobials in Dementia conducted from September 2009 to November 2012 (N=362 resident/proxy dyads; 35 facilities), and 2. Educational Video to Improve NH Care in End-stage* conducted from March 2013 to July 2017 (N=402 resident/proxy dyads; 62 facilities).

Setting

NHs around Boston.

Participants

764 NH residents with advanced dementia and their proxies.

Main Outcomes Measures

At quarterly telephone interviews, proxies stated whether they believed the resident would live, < 1 month, 1–6, 7–12, or > 12 months. Prognostic estimates were compared with resident survival. Resident and proxy characteristics associated with proxy prognostic estimates were determined. The association between prognostic estimates and whether residents experienced any of the following was determined: hospital transfers, parenteral therapy, tube-feeding, venipunctures, and bladder catheterizations.

Results

The residents’ mean age was 86.6 ± 7.3 (standard deviation), 82.6% were female, and 40.6% died over 12 months. Proxies estimated survival with moderate accuracy (c statistic, 0.67). When proxies perceived the resident would die within 6 months, they were more likely to report being asked (7.2%) versus not being asked (5.0%) about goals of care by NH providers (adjusted odds ratio (AOR), 1.94; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.50, 2.52). Residents were less likely to experience burdensome interventions when the proxy prognostic estimate was less (4.4%) versus greater than 6 months (49.6%) (AOR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.34, 0.62).

Conclusions

Proxies estimated the prognosis of NH residents with advanced dementia with moderate accuracy. Having been asked about their opinion about the goal of care was associated with the proxies’ perception that the resident had less than 6 months to live and that perception was associated with a lower likelihood the resident experienced burdensome interventions.

*Trial registration for EVINCE

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01774799

Introduction

Over 5 million Americans are afflicted with Alzheimer’s disease; a number projected to increase to 13.8 million by 2050.1 Alzheimer’s disease is the sixth most common cause of death in the United States.2 Patients with advanced dementia commonly experience burdensome interventions that may be of limited benefit and do not promote comfort.3–9

Prognostication influences end-of-life care. The U.S. Medicare Hospice benefit requires an estimated life expectancy of 6 months,10 although the prognostic accuracy of hospice guidelines for dementia patients may be little better than chance.11 Rigorously derived mortality risk scores for this population are only moderately accurate in predicting 6-month survival.11–14 Nonetheless, prior work suggests that the perception of prognosis is an important driver of end-of-life care.3, 15–17 Our group found that nursing home (NH) residents with advanced dementia whose proxies perceived they had less than 6 months to life, were less likely to get tube-fed, hospitalized, or receive parenteral therapy in their last 180 days of life.3 However, this retrospective analysis was limited to a small decedent cohort, and did not examine factors influencing prognostic perceptions. Proxies of patients with advanced cancer and critical illness report basing their prognostic perceptions on factors such as the need to remain hopeful, religious beliefs, and patient attributes (i.e., fortitude).18–20

To better understand proxies’ perceptions of prognosis and their role in the care of NH residents with advanced dementia, we combined data from two studies conducted by our group: the Study of Pathogen Resistance and Exposure to Antimicrobials in Dementia (SPREAD);9, 21 and the Educational Video to Improve Nursing home Care in End-stage dementia (EVINCE) trial.22 In both studies, proxies of NH residents with advanced dementia were prospectively asked every 3 months (up to 12 months) how long they felt the resident had to live. The objectives were to: 1. Determine the accuracy of proxies’ prognostic estimates, 2. Identify factors associated with their prognostic estimates, and 3. Examine the association between proxies’ perceived prognosis and the residents’ receipt of potentially burdensome interventions.

Methods

Data Sources

Data were leveraged from two studies with identically defined populations and data collection methods for the variables used in this report: 1. SPREAD: Study of Pathogen Resistance and Exposure to Antimicrobials in Dementia;9, 21 and 2. EVINCE: Educational Video to Improve Nursing home Care in End-stage dementia.22 SPREAD was a prospective cohort study conducted from September 2009 through November 2012 in which 362 NH residents with advanced dementia were followed in 35 Boston-area facilities for 12 months to describe infection management. EVINCE was a cluster randomized clinical trial conducted in 62 Boston-area facilities (intervention, N=31; control, N=31) conducted from March 2013 to July 2017. Proxies of NH residents with advanced dementia in intervention facilities (N=212) were exposed to advance care planning video while those in the control facilities (N=190) experienced usual care. Residents were followed for 12 months. Observational data from the intervention and control arms were combined for this report.

Hebrew SeniorLife Institutional Review Board approved the conduct of both studies. Proxies provided informed consent for the residents’ and their own participation.

Study Population

Recruitment procedures were the same in both studies. Resident eligibility criteria included: 1. Age ≥ 65, 2. dementia (any type), 3. Global Deterioration Scale (GDS) score of 7 (from nurse; range 1–7, higher scores indicate worse dementia),23 4. available English-speaking proxy, and 5. NH stay over 90 days. A GDS score of 7 is characterized by profound memory deficits (cannot recognize family), verbal ability of < 5 words, incontinence, and non-ambulatory status. Every 3 months, research assistants (RAs) asked nurses on each NH unit to identify eligible residents. Dementia diagnosis, age, and proxy availability were confirmed by chart review. Proxies were the residents’ formally or informally designated medical decision-makers.

Data Elements

All variables were collected and defined similarly in both studies, unless otherwise stated. Residents’ charts were abstracted and proxies were interviewed by RAs at baseline and quarterly thereafter for up to 12 months. If the resident died, the chart was reviewed within 14 days of death. Proxy interviews were conducted by telephone except for in-person baseline interviews in EVINCE.

This report focused on the following question asked at all proxy interviews: ‘In your opinion, how close do you feel [resident] is to the end of her/his life?’, with the following response options: 1. Less than 1 month, 2. 1 to 6 months, 3. 7 to 12 months, 4. Over 12 months, and 5. Don’t know or refused.

Two other outcomes were examined; death and use of burdensome interventions. RAs contacted nursing units bimonthly to determine if any residents had died, and if so the date of death. At each assessment, the following potentially burdensome interventions experienced by residents since the prior assessment were abstracted from their charts: hospital transfers (hospitalizations or emergency room visits), parenteral therapy for hydration or medication administration, new feeding tube insertion, venipunctures, and bladder catheterizations to work-up suspected urinary tract infections (only available in SPREAD). We selected these interventions as they are potential sources of discomfort in frail older persons,24 and generally do not reflect comfort-focused care.

Other variables were used to describe residents and proxies, and included as covariates.3, 15–20 Baseline resident data included: demographics (age, gender, and race (white versus other)), etiology of dementia (Alzheimer’s disease versus other), common comorbidities (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, and diabetes), Test for Severe Impairment (TSI) score obtained by direct resident examination (range 0–24, lower scores indicate greater cognitive impairment; dichotomized to equal to versus greater than 0),25 and functional status by nurse interview using the Bedford Alzheimer’s Nursing Severity-Subscale (BANS-S; range 7–28, higher scores indicate greater functional disability).26 At every assessment, it was determined whether the resident experienced any of the following new major illnesses since the prior assessment: hip fracture, stroke, myocardial infarction, major gastrointestinal bleed, pneumonia, and new diagnosis of cancer (other than localized skin cancer).

Baseline proxy data included: age, gender, years as proxy, and relationship to resident (child versus other). At all interviews, proxies were asked whether any NH provider had asked their opinion about the resident’s goal of care (yes/no).

Analysis

Analyses were conducted with SAS, version 9.4. Main results were generated for the combined cohorts and presented for each study separately in an Appendix. Means with standard deviations (SDs), and frequencies were used to describe continuous and categorical variables, respectively.

Cumulative incidence of death was displayed graphically and compared between SPREAD and EVINCE using survival analysis. For residents who died, survival time was calculated as the number of days between the date of baseline proxy interview and date of resident death. For all analyses examining survival as an outcome, residents who survived the follow-up period were censored at 12 months and those lost to follow-up were censored at the last known follow-up date.

Cox proportional hazards regression examined the accuracy of proxies’ prognostic estimates (independent variable) as ascertained from all interviews and analyzed as time-varying variables. A prognostic estimate over 12 months was the referent category. The model examined the association between the prognostic estimates at a particular interview date and the risk of the resident dying given that the resident had survived up until that point. Since response options did not include prognostic estimates between 6 and 7 months, actual survival times during that interval were rounded up or down. Robust standard errors accounted for clustering at the facility-level. Adjusted hazard ratios (AHRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed. A generalized version of the c statistic allowing for censored data was calculated as a measure of the model’s overall accuracy (range 0.5–1, higher scores indicate greater accuracy).27 A sensitivity analysis excluded proxies in the EVINCE intervention group, as the video could have influenced the accuracy of their prognostic estimates.

Logistic regression was used to identify resident and proxy characteristics (independent variables) associated with a proxy prognostic estimate of less than 6 months (outcome). The prognosis variable was dichotomized because the proportion of interviews at which proxies estimated prognosis to be less than 1 month and 1 to 6 month were too small to examine as separate categories. Interviews at which the proxy responded ‘don’t know’ or refused to answer were excluded. The analysis was conducted at the level of assessment intervals. Independent variables considered ‘a priori’ to be possibly associated with prognostication,3, 18–20 included; resident demographics (age (dichotomized at median), gender, white), dementia type, comorbidities, TSI, BANS-S, hospital transfer in prior 3 months, proxy demographics (age (dichotomized at median), gender), proxy relationship to resident, and goals of care discussions. Proxy prognostic estimates and other dynamic independent variables (e.g., hospital transfers) were ascertained from each assessment. Static variables (e.g., gender) were brought forward from baseline. Bivariable analyses examined the unadjusted associations between each independent variable and prognosis at a given assessment interval. Variables associated with the outcome at P < .10 in the unadjusted analyses were entered into a multivariable model. Generalized estimating equations (GEE) accounted for clustering among residents/dyad dyads. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs were computed.

Finally, logistic regression was used to examine the association between a proxy prognostic estimate of less than 6 months (main independent variable) and the use of any of the following burdensome interventions (outcome): hospital transfer, parenteral therapy, new feeding tube, venipuncture, and bladder catheterization. The analysis was conducted at the level of assessment intervals and excluded assessments with don’t know/refused responses to the prognosis question. Prognosis was derived from the interview conducted at the beginning of a given 3-month interval. The outcome was defined as whether the resident experienced a burdensome intervention during the 3-month interval following that interview. Covariates considered ‘a priori’ to be possibly associated with intervention use3, 15–17 included: resident demographics, dementia type, comorbidities, TSI, BANS-S, new major illness, proxy demographics, proxy relationship to resident, and goals of care discussions. Dynamic covariates were drawn from the assessment that best related the resident’s status during the interval. For example, occurrence of a major illness was ascertained from the chart review done at the end of the interval, which recorded events during the interval. Being asked about goals of care was drawn from the interview at the start of the interval. Static variables were brought forward from baseline. Bivariable followed by multivariate analyses were conducted as described above and GEE accounted for clustering among resident/proxy dyads. ORs with 95% CIs were computed.

Results

Resident and Proxy Characteristics

Baseline characteristics were comparable between the two studies (SPREAD, N=362 dyads; EVINCE, N=402 dyads) (Table 1). Resident characteristics of the combined cohort (N=764 dyads) included: mean age, 86.6 ± 7.3 (SD); female, 82.6%; and white, 89.7%. A total of 53.9% residents had TSI scores equal to 0, and their mean BANS-S score was 20.6 ± 2.8 (SD), indicating severe cognitive and functional impairment, respectively. Proxy characteristics were: mean age, 61.4 ± 10.6 (SD); female, 64.4%; years as proxy, 8.8 ± 6.3 (SD); and child of resident, 64.0%.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Nursing Home Residents with Advanced Dementia and their Proxies

| Characteristics | SPREAD and EVINCE combined (N=764)a |

SPREAD (N=362) | EVINCE (N=402) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resident | |||

| Age (years), mean ± standard deviation | 86.6 ± 7.3 | 86.5 ± 7.3 | 86.7 ± 7.4 |

| Age > 87 (median) | 362 (47.4) | 174 (48.1) | 188 (46.8) |

| Female, % | 631 (82.6) | 308 (85.1) | 323 (80.3) |

| White (vs other), % | 685 (89.7) | 335 (92.5) | 350 (87.1) |

| Alzheimer’s disease (vs other), % | 552 (72.3) | 269 (74.3) | 283 (70.4) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, % | 90 (11.8) | 42 (11.6) | 48 (11.9) |

| Congestive heart failure, % | 120 (15.7) | 63 (17.4) | 57 (14.2) |

| Diabetes, % | 146 (19.1) | 67 (18.5) | 79 (19.7) |

| TSI = 0 (vs greater than 0), %b | 412 (53.9) | 222 (61.3) | 190 (47.3) |

| BANS-S, mean ± standard deviationc | 20.6 ± 2.8 | 21.2 ± 2.7 | 20.1 ± 2.8 |

| BANS-S > 21 (median) | 328 (42.9) | 182 (50.3) | 146 (36.3) |

| Enrolled in hospice | 105 (13.7) | 31 (8.6) | 74 (18.4) |

| Died during 12 month follow-up, % | 310 (40.6) | 135 (37.3) | 175 (43.5) |

| Proxy | |||

| Age (years), mean ± standard deviationd | 61.4 ± 10.6 | 60.4 ± 10.3 | 62.3 ± 10.8 |

| Age > 61 (median) | 348 (45.6) | 153 (42.3) | 195 (48.5) |

| Female, % | 492 (64.4) | 226 (62.4) | 266 (66.2) |

| Years as proxy, mean ± standard deviationd | 8.8 ± 6.3 | 8.1 ± 5.7 | 9.4 ± 6.8 |

| Child of resident (vs other), % | 489 (64.0) | 233 (64.4) | 256 (63.7) |

| Prognostic estimates of resident survival, % | |||

| <1 month | 10 (1.3) | 3 (0.8) | 7 (1.7) |

| 1–6 months | 75 (9.8) | 29 (8.0) | 46 (11.4) |

| 7–12 months | 148 (19.4) | 59 (16.3) | 89 (22.1) |

| >12 months | 477 (62.4) | 240 (66.3) | 237 (59.0) |

| Don’t know or refused to answer | 54 (7.1) | 31 (8.6) | 23 (5.7) |

SPREAD = the Study of Pathogen Resistance and Exposure to Antimicrobials in Dementia; EVINCE = the Educational Video to Improve Nursing home Care in End-stage dementia.

TSI = Test for Severe Impairment, range 0–24, lower scores indicate greater cognitive impairment.

BANS-S = Bedford Alzheimer’s Nursing Severity-Subscale, range 7–28, higher scores indicate more functional disability.

Data missing for proxy age (N=10) and years as proxy (N=5).

Survival and Accuracy of Proxy Prognostic Estimates

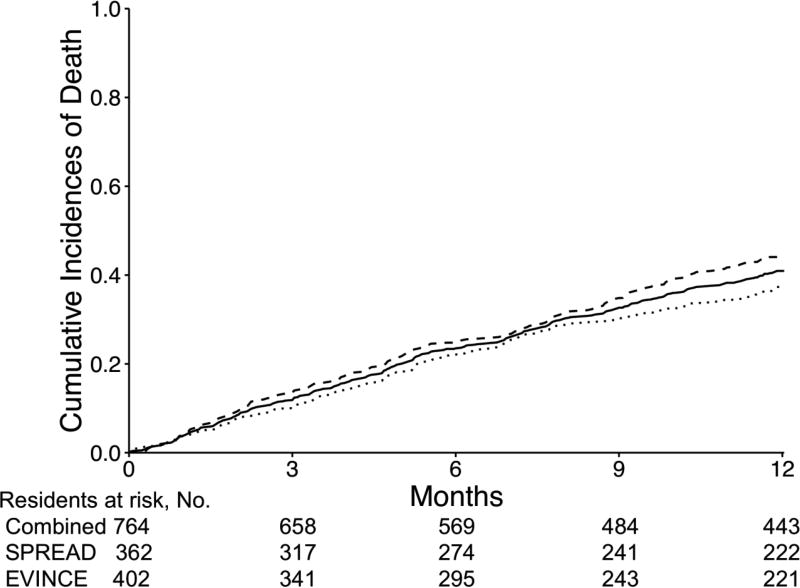

In the combined cohort, 310 (40.6%) residents died, and 11 were lost to follow-up. In SPREAD, 135 residents died (37.3%) and 5 were lost to follow-up. In EVINCE, 175 residents died (43.5%) and 6 were lost to follow-up. Six-month mortality rates were; combined cohort, N=195 (25.5%); SPREAD, N=88 (24.3%); and EVINCE, N=107 (26.6%). Figure 1 shows the cumulative incidences of death for the combined cohort, and each cohort separately which did not differ significantly (P = .08).

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidences of death among nursing home residents with advanced dementia in the Study of Pathogen Resistance and Exposure to Antimicrobials in Dementia study (N=362; dotted line) and the Educational Video to Improve Nursing Home Care in End-stage dementia study (N=402; dashed line), and two studies combined (N=764; solid line).

At baseline, proxies’ estimates of the resident prognosis were: less than 1 month, N=10 (1.3%); 1 to 6 months, N=75 (9.8%); 7 to 12 months, N=148 (19.4%); over 12 months, N=477 (62.4%); and don’t know/refused, N=54 (7.1%). At all proxy interviews (i.e., baseline and follow-up) (N=2649), proxy prognostic estimates were: less than 1 month, N=30 (1.1%); 1 to 6 months, N=279 (10.5%); 7 to 12 months, N=664 (25.1%); over 12 months, N=1553 (58.6%); and don’t know/refused, N=123 (4.6%). In the Cox model, the likelihood of dying was higher among residents whose proxies thought they had a shorter prognosis (referent, over 12 months): less than 1 month, AHR, 27.53; 95% CI, 15.81, 47.95; 1 to 6 months, AHR, 4.61; 95% CI, 3.12, 6.79; 7 to 12 months, AHR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.38, 2.64; and don’t know/refused, AHR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.40, 2.14. The model’s c statistic was 0.67. Results were similar when analyzed in the EVINCE cohort with the intervention arm excluded: less than 1 month, AHR, 28.77; 95% CI, 13.99, 59.18; 1 to 6 months, AHR, 4.89; 95% CI, 3.10, 7.71; 7 to 12 months, AHR, 2.05; 95% CI, 1.43, 2.94; and don’t know/refused, AHR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.39, 2.78. The c statistic was 0.67.

Factors Associated with Proxy Prognostication

The proportion of all interviews (N=2526) at which proxies stated the resident had less than 6 months was 12.2% (N=309). In unadjusted analyses, variables associated with a proxy prognostic estimate of less than 6 months at a P < .10 were: resident age > 87, female proxy, and being asked about goals of care (Table 2). In the multivariable model, only having been asked about goals of care (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.94; 95% CI, 1.50, 2.52) and female proxy (AOR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.09, 2.20) remained significantly associated with a prognostic estimate of less than 6 months.

Table 2.

Association Between Characteristics of Nursing Home Residents with Advanced Dementia and their Proxies and the Proxy’s Perception that the Resident had Less Than 6 Months to Livea

| Characteristic | Total No. (%) of Assessment Intervals with Characteristicb (N=2526) |

No. (%) of Assessment Intervals in Which Proxy Estimated Resident had < 6 Months to Live (N=309) |

Odds Ratioc for Proxy Perceived Prognosis (95% Confidence Interval) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With Characteristic Present |

With Characteristic Absent |

Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||

| Resident | |||||

| Age > 87 (median) | 1178 (46.6) | 164 (6.5) | 145 (5.7) | 1.34 (0.96, 1.88)d | |

| Female | 2110 (83.5) | 248 (9.8) | 61 (2.4) | 0.78 (0.50, 1.21) | |

| White | 2272 (89.9) | 279 (11.1) | 30 (1.2) | 1.05 (0.56, 1.96) | |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 1813 (71.8) | 216 (8.6) | 93 (3.7) | 0.90 (0.62, 1.31) | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 264 (10.5) | 43 (1.7) | 266 (10.5) | 1.46 (0.92, 2.32) | |

| Congestive heart failure | 387 (15.3) | 52 (2.1) | 257 (10.2) | 1.14 (0.71, 1.81) | |

| Diabetes | 454 (18.0) | 56 (2.2) | 253 (10.0) | 1.01 (0.66, 1.56) | |

| TSI = 0e | 1315 (52.1) | 165 (6.5) | 144 (5.7) | 1.06 (0.76, 1.49) | |

| BANS-S > 21 (median)f | 996 (39.4) | 129 (5.1) | 180 (7.1) | 1.12 (0.80, 1.56) | |

| Any hospital transfer in prior 3 monthsg | 100 (4.0) | 17 (0.7) | 292 (11.6) | 1.50 (0.86, 2.60) | |

| Proxy | |||||

| Age > 61 (median)h | 1186 (47.4) | 158 (6.3) | 149 (6.0) | 1.20 (0.86, 1.69) | |

| Female | 1613 (63.9) | 224 (8.9) | 85 (3.4) | 1.57 (1.10, 2.24)d | 1.55 (1.09, 2.20) |

| Child of resident | 1565 (62.0) | 200 (7.9) | 109 (4.3) | 1.15 (0.80, 1.65) | |

| Asked their opinion about goals of care by a nursing home provider | 1126 (44.6) | 183 (7.2) | 126 (5.0) | 1.96 (1.52, 2.54)d | 1.94 (1.50, 2.52) |

Proxies stated the resident had less than 6 months to live at 12.2% (N=309/2526) of interviews.

Analyses were at the level of assessment intervals. Resident chart reviews and proxy interviews were done at baseline and quarterly for up to 12 months. Static variables were brought forward from baseline. Proxy’s perception of prognosis and other dynamic variables (e.g., goals of care discussion, hospital transfers) were ascertained from each assessment period.

Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratio accounted for clustering among resident/proxy dyads using generalized estimating equations.

Variables that were significant at P < 0.10 in bivariable analyses and entered into the multivariable model.

TSI = Test for Severe Impairment, range 0–24, lower scores indicate greater cognitive impairment.

BANS-S = Bedford Alzheimer’s Nursing Severity-Subscale, range 7–28, higher scores indicate greater functional disability.

Hospital transfer included hospitalization or emergency room visit.

Age missing for 24 proxies.

Use of Burdensome Interventions

There were 2031 resident-assessment intervals available to examine the use of burdensome interventions over the follow-up period. The proportion of intervals during which residents experienced burdensome interventions were: hospital transfer, N=68 (3.3%); parenteral therapy, N=49 (2.4%); new feeding tube, N=3 (0.1%); venipuncture, N=1048 (51.6%); bladder catheterizations, N=157 (7.7%); and any intervention, N=1097 (54.0%). In unadjusted analyses, factors associated with a lower likelihood of any burdensome intervention use at P < 0.10 included: proxy prognosis of less than 6 months, resident age > 87, white resident, TSI equal to 0, BANS-S > 21, proxy age > 61, and child of resident (Table 3). Congestive heart failure, diabetes, and any new major illness were associated with a greater likelihood of receiving a burdensome intervention. After multivariate adjustment, a prognostic estimate of less than 6 months remained significantly associated with a lower likelihood of the resident receiving any burdensome interventions (AOR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.34, 0.62).

Table 3.

Association between Proxy Perception of Prognosis and Use of Burdensome Interventionsa among Nursing Home Residents with Advanced Dementia

| Characteristic | Total No. (%) of Assessment Intervals with Characteristicb (N=2031) |

No. (%) of Assessment Intervals in Which Resident had Any Burdensome Interventions (N=1097) |

Likelihood of a Burdensome Intervention Odds Ratioc (95% Confidence Interval) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With Characteristic Present |

With Characteristic Absent |

Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||

| Proxy Estimated Resident had < 6 Months to Live | 251 (12.4) | 89 (4.4) | 1008 (49.6) | 0.47 (0.35, 0.62)d | 0.46 (0.34, 0.62) |

| Resident Covariates | |||||

| Age > 87 (median) | 954 (47.0) | 490 (24.1) | 607 (29.9) | 0.81 (0.64, 1.02)d | 0.77 (0.61, 0.97) |

| Female | 1691 (83.3) | 917 (45.2) | 180 (8.9) | 1.13 (0.83, 1.52) | |

| White | 1837 (90.5) | 970 (47.8) | 127 (6.3) | 0.58 (0.40, 0.86)d | |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 1472 (72.5) | 781 (38.5) | 316 (15.6) | 0.89 (0.69, 1.14) | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 217 (10.7) | 120 (5.9) | 977 (48.1) | 1.00 (0.69, 1.44) | |

| Congestive heart failure | 318 (15.7) | 203 (10.0) | 894 (44.0) | 1.63 (1.19, 2.22)d | 1.63 (1.19, 2.24) |

| Diabetes | 357 (17.6) | 243 (12.0) | 854 (42.1) | 1.94 (1.41, 2.67)d | 1.91 (1.39, 2.63) |

| TSI = 0e | 1053 (51.9) | 501 (24.7) | 596 (29.4) | 0.57 (0.46, 0.72)d | 0.66 (0.52, 0.86) |

| BANS-S > 21 (median)f | 808 (39.8) | 373 (18.4) | 724 (35.7) | 0.58 (0.46, 0.74)d | 0.68 (0.53, 0.88) |

| Any new major illness in prior 3 monthsg | 109 (5.4) | 82 (4.0) | 1015 (50.0) | 2.59 (1.70, 3.96)d | 2.83 (1.84, 4.35) |

| Proxy Covariates | |||||

| Age > 61 (median)h | 941 (46.3) | 481 (23.7) | 606 (29.8) | 0.78 (0.62, 0.98)d | |

| Female | 1288 (63.4) | 671 (33.0) | 426 (21.0) | 0.86 (0.68, 1.08) | |

| Child of resident | 1268 (62.4) | 709 (34.9) | 388 (19.1) | 1.22 (0.97, 1.55)d | |

| Asked their opinion about goals of care by a nursing home provider | 953 (46.9) | 501 (24.7) | 596 (29.4) | 0.88 (0.74, 1.04) | |

Burdensome interventions included any of the following: hospital transfer (hospitalization or emergency room visits), parenteral therapy, new feeding tube insertion, venipuncture, and bladder catheterizations.

Analyses were at the level of assessment intervals. Resident chart reviews and proxy interviews were done at baseline and quarterly for up to 12 months. Proxy prognosis was taken from the interview done at the start of the interval. The use of burdensome interventions reflected the residents experience during the 3-month interval following that interview. Dynamic covariates were drawn from the assessment that best reflected the resident’s status during the interval of interest (e.g., any new major illness). Static variables were brought forward from baseline.

Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratio accounted for clustering among resident/proxy dyads using generalized estimating equations.

Variables that were significant at P < 0.10 in bivariable analyses and entered into the multivariable model.

TSI = Test for Severe Impairment, range 0–24, lower scores indicate greater cognitive impairment.

BANS-S = Bedford Alzheimer’s Nursing Severity-Subscale, range 7–28, higher scores indicate more disability.

Any new major illness included hip fracture, stroke, myocardial infarction, major gastrointestinal bleed, pneumonia, and/or new diagnosis of cancer (other than localized skin cancer).

Age missing for 18 proxies.

Discussion

In this report, proxies of NH residents with advanced dementia predicted how long the resident would live with moderate accuracy. Having been asked about their opinion about the goals of care was the factor most strongly associated with the proxies’ perception that the resident had less than 6 months to live. Residents were significantly less likely to experience burdensome interventions when their proxies perceived they would die within 6 months.

The accuracy of the proxy’s prognostic estimates was modest, but remarkably identical to the empirically derived Advanced Dementia Prognostic Tool (c statistic, 0.67), and better than hospice guidelines for dementia (c statistic of 0.55).11 Prognostic estimates of proxies of patients in intensive care units are reportedly somewhat more accurate (c statistic, 0.74),18 perhaps because it is easier to recognize impending death in the context of critical illness. We found a minority of proxies believed the resident would die within 6 months, and that they underestimated mortality; 40.6% of residents died over 12 months but at baseline only 30.5% of proxies perceived the resident would die in 12 months. An overly optimistic perception of prognosis is a consistent finding among proxies, patients, and clinicians in the context of other serious illnesses.15, 18, 28, 29

Having been asked their opinion about the goals of care by NH providers was most strongly associated with proxies’ perception that the resident had less than 6 months to live. Given that the question referred to a time period before the proxy interview, renders it less likely the association was due to proxies seeking out goals of care discussions as a consequence of believing the resident may die soon. While we did not ascertain the contents of these conversations, research from the critical care setting found that providers make prognostic statements of some nature in the vast majority of discussions about goals of care.30

This study supports and furthers research suggesting that patients whose proxies believe they are close to the end-of-life are more likely to opt for comfort-focused care,22 and receive fewer burdensome interventions.3, 15–17 A cross-sectional analyses of baseline EVINCE data found that proxies who perceived the resident had a life expectancy of less than 6 months, were significantly more likely to prefer a level of care that only included treatments to reduce suffering versus one that included potentially life-prolonging but uncomfortable interventions (AOR, 12.5; 95% CI, 4.04, 37.08). The interventions considered potentially burdensome in this report are not indicative of comfort-focused care. Even venipunctures and bladder catheterizations, which may be considered relatively benign, can be a source of discomfort in these very frail residents and generally are not undertaken when the goal of care is solely comfort.24

Several limitations of this report deserve comment. First, the study was limited to a primarily white cohort in Boston-area NHs, and thus findings may not be generalizable to other regions or populations. Second, proxies selected their prognostic estimates from categories of expected survival. Alternative approaches, such as estimating the probability of surviving a given time frame (probability approach), asking about life expectancy in a more open-ended fashion (temporal approach) or the ‘surprise question’, may yield different prognostic accuracies.29, 31, 32 Third, we could not assess the accuracy of the proxies’ reports about being asked about goals of care or which aspects of these discussions may have influenced their prognostic estimates. It is likely that factors not captured in the dataset impacted those perceptions,18–20 but require a qualitative approach to elucidate.

This report demonstrates that proxies are moderately accurate in estimating how long NH residents with advanced dementia will live. Regardless of accuracy, the proxy’s perception that the resident may die within 6 months was associated with the use of fewer burdensome interventions. Goals of care discussions with providers may be important for proxies to gain that perception. In advanced dementia, in which highly accurate prognostication can be elusive, an understanding of the terminal nature of this condition may be pertinent to promoting a comfort-focused approach to care.

Supplementary Material

KEY POINTS.

Question

How do proxies perceive the prognosis of nursing home residents with advanced dementia and how do their perceptions influence care?

Findings

In this prospective cohort study, proxies estimated the prognosis of advanced dementia residents (N=764 dyads) with moderate accuracy. Goals of care discussions were strongly associated with proxies perceiving a prognosis shorter than 6 months and residents whose proxies perceived such prognosis were significantly less likely to experience burdensome interventions.

Meaning

Proxies are reasonably good at estimating when residents with advanced dementia will die and their prognostic perceptions may influence the type of care the resident receives.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This research was supported by the following grants: NIH-NIA R01 AG032982, NIH-NIA R01 AG043440, and NIH-NIA K24AG033640 (Mitchell); the Swiss National Science Foundation P1ZHP3_171747, and the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences PC 22/14 (Loizeau).

Role of the Sponsors: The funding sources for this study played no role in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Drs. Mitchell and Shaffer had full access to all data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analyses.

Study concept and design: Mitchell, Loizeau, Shaffer

Acquisition of data: Mitchell, Volandes

Analyses and interpretation of data: Mitchell, Loizeau, Habtemariam, Hanson, Volandes, Shaffer

Drafting of manuscript: Mitchell, Loizeau

Critical revision of manuscript for important intellectual content: Mitchell, Loizeau, Habtemariam, Shaffer, Hanson, Volandes

Statistical analyses: Mitchell, Loizeau, Habtemariam, Shaffer

Administrative, technical or material support: Mitchell

Study supervision: Mitchell

Financial Disclosures: None

References

- 1.Hebert LE, Weuve J, Scherr PA, Evans DA. Alzheimer disease in the United States (2010–2050) estimated using the 2010 census. Neurology. 2013;80(19):1778–1783. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828726f5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Center for Health Statistics. [Accessed November 3, 2017];National vital statistics reports 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr65/nvsr65_04.pdf.

- 3.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, et al. The clinical course of advanced dementia. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(16):1529–1538. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morrison RS, Siu AL. Survival in end-stage dementia following acute illness. JAMA. 2000;284(1):47–52. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mitchell SL, Morris JN, Park PS, Fries BE. Terminal care for persons with advanced dementia in the nursing home and home care settings. J Palliat Med. 2004;7(6):808–816. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2004.7.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Roy J, Kabumoto G, Mor V. Clinical and organizational factors associated with feeding tube use among nursing home residents with advanced cognitive impairment. JAMA. 2003;290(1):73–80. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meier DE, Ahronheim JC, Morris J, Baskin-Lyons S, Morrison RS. High short-term mortality in hospitalized patients with advanced dementia: lack of benefit of tube feeding. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(4):594–599. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.4.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gozalo P, Teno JM, Mitchell SL, et al. End-of-life transitions among nursing home residents with cognitive Issues. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(13):1212–1221. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1100347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitchell SL, Shaffer ML, Loeb MB, et al. Infection management and multidrug-resistant organisms in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(10):1660–1667. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The National Hospice Organization. Medical guidelines for determining prognosis in selected non-cancer diseases. Hosp J. 1996;11(2):47–63. doi: 10.1080/0742-969x.1996.11882820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitchell SL, Miller SC, Teno JM, Kiely DK, Davis RB, Shaffer ML. Prediction of 6-month survival of nursing home residents with advanced dementia using ADEPT vs hospice eligibility guidelines. JAMA. 2010;304(17):1929–1935. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Hamel MB, Park PS, Morris JN, Fries BE. Estimating prognosis for nursing home residents with advanced dementia. JAMA. 2004;291(22):2734–2740. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.22.2734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitchell SL, Miller SC, Teno JM, Davis RB, Shaffer ML. The Advanced Dementia Prognostic Tool: a risk score to estimate survival in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40(5):639–651. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van der Steen JT, Mitchell SL, Frijters DH, Kruse RL, Ribbe MW. Prediction of 6-month mortality in nursing home residents with advanced dementia: validity of a risk score. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2007;8(7):464–468. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weeks JC, Cook EF, O’Day SJ, et al. Relationship between cancer patients’ predictions of prognosis and their treatment preferences. JAMA. 1998;279(21):1709–1714. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.21.1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van der Steen JT, Helton MR, Ribbe MW. Prognosis is important in decisionmaking in Dutch nursing home patients with dementia and pneumonia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24(9):933–936. doi: 10.1002/gps.2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cook D, Rocker G, Marshall J, et al. Withdrawal of mechanical ventilation in anticipation of death in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(12):1123–1132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.White DB, Ernecoff N, Buddadhumaruk P, et al. Prevalence of and factors related to discordance about prognosis between physicians and surrogate decision makers of critically ill patients. JAMA. 2016;315(19):2086–2094. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.5351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boyd EA, Lo B, Evans LR, et al. “It’s not just what the doctor tells me:” factors that influence surrogate decision-makers’ perceptions of prognosis. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(5):1270–1275. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181d8a217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chiarchiaro J, Buddadhumaruk P, Arnold RM, White DB. Quality of communication in the ICU and surrogate’s understanding of prognosis. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(3):542–548. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitchell SL, Shaffer ML, Kiely DK, Givens JL, D’Agata E. The study of pathogen resistance and antimicrobial use in dementia: study design and methodology. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2013;56(1):16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitchell SL, Palmer JA, Volandes AE, Hanson LC, Habtemariam D, Shaffer ML. Level of care preferences among nursing home residents with advanced dementia. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;54(3):340–345. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reisberg B, Ferris SH, de Leon MJ, Crook T. The Global Deterioration Scale for assessment of primary degenerative dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139(9):1136–1139. doi: 10.1176/ajp.139.9.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morrison RS, Ahronheim JC, Morrison GR, et al. Pain and discomfort associated with common hospital procedures and experiences. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1998;15(2):91–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Albert M, Cohen C. The Test for Severe Impairment: an instrument for the assessment of patients with severe cognitive dysfunction. J Am Geriatric Soc. 1992;40(5):449–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb02009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Volicer L, Hurley AC, Lathi DC, Kowall NW. Measurement of severity in advanced Alzheimer’s disease. J Gerontol. 1994;49(5):M223–M226. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.5.m223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. [Accessed November 3, 2017];Biomedical statistics and informatics: locally written SAS macros. http://www.mayo.edu/research/departments-divisions/department-health-sciences-research/division-biomedical-statistics-informatics/software/locally-written-sas-macros.

- 28.Fried TR, Bradley EH, O’Leary J. Changes in prognostic awareness among seriously ill older persons and their caregivers. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(1):61–69. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.White N, Reid F, Harris A, Harries P, Stone P. A systematic review of predictions of survival in palliative care: how accurate are clinicians and who are the experts? PLoS ONE. 2016;11(8):e0161407. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.White DB, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, Lo B, Curtis JR. Prognostication during physician-family discussions about limiting life support in intensive care units. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(2):442–448. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000254723.28270.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perez-Cruz PE, dos Santos R, Silva TB, et al. Longitudinal temporal and probabilistic prediction of survival in a cohort of patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;48(5):875–882. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.White N, Kupeli N, Vickerstaff V, Stone P. How accurate is the “surprise question” at identifying patients at the end of life? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2017;15(139):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12916-017-0907-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.