Abstract

Background and Purpose

Recent work from our group suggests human neural stem cell derived extracellular vesicle (NSC EV) treatment improves both tissue and sensorimotor function in a preclinical thromboembolic (TE) mouse model of stroke. In this study, NSC EVs were evaluated in a pig ischemic stroke model, where clinically relevant endpoints were utilized to assess recovery in a more translational large animal model.

Methods

Ischemic stroke was induced by permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO), and either NSC EV or PBS treatments were administered intravenously (IV) at 2, 14, and 24 hours post-MCAO. NSC EV effects on tissue level recovery were evaluated via magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at 1 and 84 days post-MCAO. Effects on functional recovery were also assessed through longitudinal behavior and gait analysis testing.

Results

NSC EV treatment was neuroprotective and led to significant improvements at the tissue and functional levels in stroked pigs. NSC EV treatment eliminated intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) in ischemic lesions in NSC EV pigs (0/7) versus control pigs (7/8). NSC EV treated pigs exhibited a significant decrease in cerebral lesion volume and decreased brain swelling relative to control pigs 1 day post-MCAO. NSC EVs significantly reduced edema in treated pigs relative to control pigs, as assessed by improved diffusivity through Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (ADC) maps. NSC EVs preserved white matter (WM) integrity with increased corpus callosum fractional anisotropy (FA) values 84 days post-MCAO. Behavior and mobility improvements paralleled structural changes, as NSC EV treated pigs exhibited improved outcomes including increased exploratory behavior and faster restoration of spatiotemporal gait parameters.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated for the first time in a large animal model novel NSC EVs significantly improved neural tissue preservation and functional levels post-MCAO, suggesting NSC EVs may be a paradigm changing stroke therapeutic.

Indexing terms: ischemic stroke, extracellular vesicles, magnetic resonance imaging, porcine, gait analysis, open field

Subject terms: Basic, Translational, and Preclinical Research

Introduction

Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved therapies for stroke (tissue plasminogen activator and endovascular thrombectomy) are currently only available to a small subpopulation of stroke victims1, 2. Following a litany of failed treatments, assessment by the Stem Cell Emerging Paradigm in Stroke (STEPS) consortium meetings identified major needs including 1) a regenerative therapy, and 2) testing in translational animal models more reflective of human pathology3, 4. Similarly, the Stroke Therapy Academic Industry Roundtable (STAIR) encouraged 1) testing in higher-order gyrencephalic species, 2) evaluating clinically relevant routes of administration, and 3) longitudinal behavior assessment5, 6. These recommendations prompted our therapeutic evaluation of intravenously (IV) administered human neural stem cell extrecellular vesicles (NSC EVs) in a translational pig ischemic stroke model.

One of the most promising emerging therapeutics capable of addressing the need for a neuroprotective and/or regenerative therapy are extracellular vesicles (EVs) sourced from stem cells cultures7. EVs are heterogeneous populations of both 50–1,000 nm plasma membrane shed microvesicles, and 40–150 nm exosomes derived from the endocytic pathway. These EVs are enriched in transmembrane proteins, bioactive lipids, and miRNAs, and are produced by virtually all cell types8, 9. Recently, the therapeutic potential of these cell signaling vesicles has been explored from several cell sources and for varied applications10. The vast majority of previously reported neural injury studies evaluating stem cell derived EVs have utilized mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) derived EVs11–13. However, in vivo biodistribution of EVs is highly dependent on cell source, suggesting EVs will display specific biodistribution patterns in vivo reflecting their parent cell line14. We compared the neuroprotective and regenerative properties of NSC EVs versus isogenically derived MSC EVs in a mouse thromboembolic (TE) stroke model. MSC EV treatments trended towards decreasing stroke lesion volume whereas NSC EVs signifincantly decreased lesion size, preserved motor function, and improved episodic memory15. These findings collectively warrant further rigorous testing of NSC EVs in a secondary pig ischemic stroke model.

Following the STEPs and STAIR committees’ recommendations, NSC EV therapeutic benefits should be extensively tested using clinically relevant routes of administration, treatment regimen, and endpoints in a large animal model of ischemic stroke. The porcine permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) model possesses several advantages including brain anatomy and physiology comparable to humans16–18. Both human and porcine brains are gyrencephalic and are composed of >60% white matter (WM), while rodent brains are lissencephalic and are composed of <10% WM19–22. These similar attributes in cytoarchitecture are critically important as WM is highly vulnerable to pathological processes that follow ischemic stroke22. Since pigs are of similar body size to humans and their brains are only 7.5 times smaller than human brains, compared to the 650 times smaller rodent brain, pigs are a more direct assessment of dosing in a preclinical model18. These similarities in brain composition, cytoarchitecture, and size collectively support the use of a pig ischemic stroke model to better predict outcomes between preclinical rodent models and human clinical trials.

The objectives of this study were to evaluate the therapeutic potential of NSC EVs through magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at 1 and 84 days post-MCAO, and to longitudinally assess changes in motor function via gait analysis and open field testing. In this study we present for the first time, evidence NSC EVs promote extensive tissue and functional level recovery in a large animal preclinical stroke model.

Materials and Methods

Data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Study Design

The overarching aim of these studies were to evaluate NSC EV efficacy as a potential acute stroke therapy in a preclinical, biologically relevant porcine MCAO model of ischemic stroke. Endpoints were selected to evaluate tissue and functional level changes in response to treatment. We employed a split plot experimental design, where all treatment groups were conducted within one day to control for and reduce experimental variation. The sample size for this study was determined by a power calculation based on our previously published work using the pig MCAO model with lesion volume changes by MRI imaging being the primary endpoint23. The power analysis was calculated using a two-tailed ANOVA test, α=0.05, and an 80% power of detection, effect size of 1.19 and a standard deviation of 44.63. Initially, 14 pigs were randomly assigned to the treated and control groups. However, due to high mortality rates within the control group, 2 additional pigs were added to the control group for a total 9 pigs in the control group and 7 pigs in the treated group (physiological data, and mortality information included in online-only data supplement Table I and II, respectively). While a greater percentage of NSC EV pigs survived relative to control pigs, there were no statistically significant survival rate differences between treatment groups (online-only data supplement Fig. I). Ischemic stroke was induced by a blinded surgeon and EVs were delivered as single use aliquots by investigators. To control for potential day effects, one treated and one control pig were assigned to each surgical day except for one surgical day in which the two additional control pig surgeries were performed. Due to the timing of the first treatment, it was not possible to show proof of identical lesion sizes prior to NSC EV administration or account for progression rate of lesions. However, a one-way ANOVA and post-hoc Tukey-Kramer pair-wise test comparing the lesion volumes of pigs within each treatment group between the first and second half of the study resulted in no significant difference (treated p= 0.9994, non-treated p= 0.7804). This consistency in lesion volumes suggests there was no significant difference in time dependent variables including the effect of surgical procedures over the course of the study. All endpoints and functional measurements were prospectively planned and underwent unblinded analysis. Predefined exclusion criteria from all endpoints included instances of infection in the injury site, self-inflicted injuries that required euthanasia, inability to thermoregulate, uncontrolled seizure activity, and/or respiratory distress. 1 control pig was excluded from MRI collection due to post-operative complications and premature death (online-only data supplement Table II). Data collection from 1 treated pig was retrospectively excluded from all assessments due to a Trueperella (Arcanobacterium) pyogenes abscess and was determined to be the result of the surgery by pathologists and veterinarians. No outliers were removed from the data.

Results

NSC EV manufacture consistently produced biologically active and reproducible vesicles

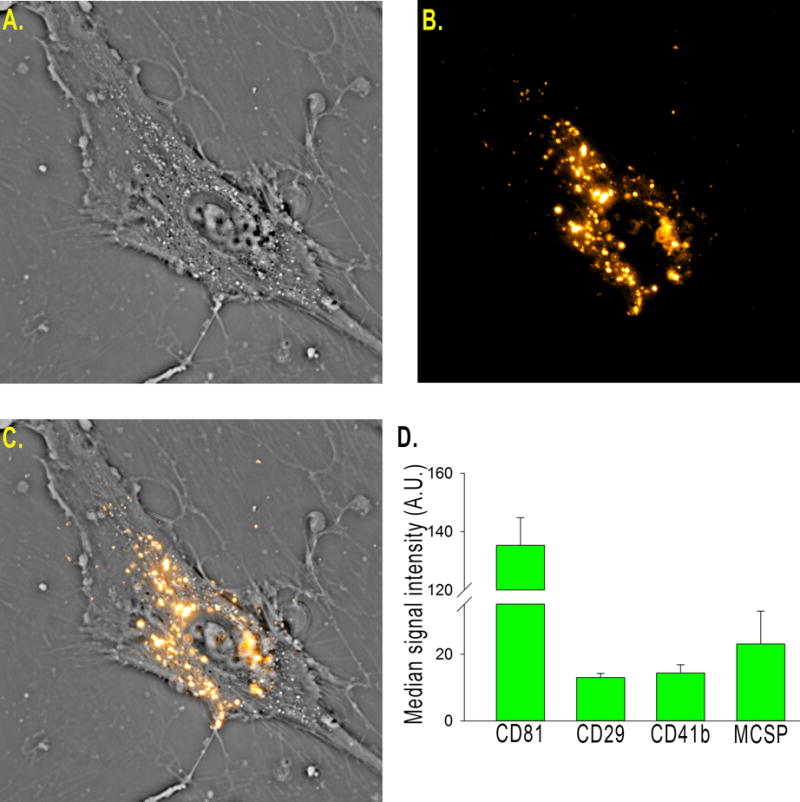

EVs were harvested from NSC basal culture medium according to standard production protocol and with reproducible size profile with over 90% of EVs under 200 nm in diameter as determined by Nanosight (online-only data supplement methods)15. To determine cellular uptake of NSC EVs, a critical component of EV function, uptake of DiI labeled NSC EVs was evaluated using an interferometric technique known as spatial light interference microscopy (SLIM)24. Time lapse imaging (18 hour time point shown) indicated NSC EVs were taken up by cells and were visualized while being transported within the cell (Fig. 1A–C, online-only data supplement Movie SI). NSC EVs may ultimately exert their efficacy through uptake by various cell types when in circulation. NSC EVs were analyzed using a commercially available MACSPlex exosome kit and displayed a consistent EV marker profile (Fig. 1D). Along with the recently published physical size evaluation this data supported a consistent profile and bioactivity of NSC EVs derived from separate purifications15.

Figure 1. NSC EV manufacture produces biologically active, consistent vesicles.

DiI labeled vesicles (B) were added into the culture medium of human umbilical MSCs (A) and imaged over 24 hours (A–C). Vesicles are taken up by the cells (C) and can be seen being actively transported within the cell. Flow cytometry is routinely used for batch analysis of NSC EVs (using the commercially available MACSPlex kit) and indicates NSC EVs have a consistent marker profile (D).

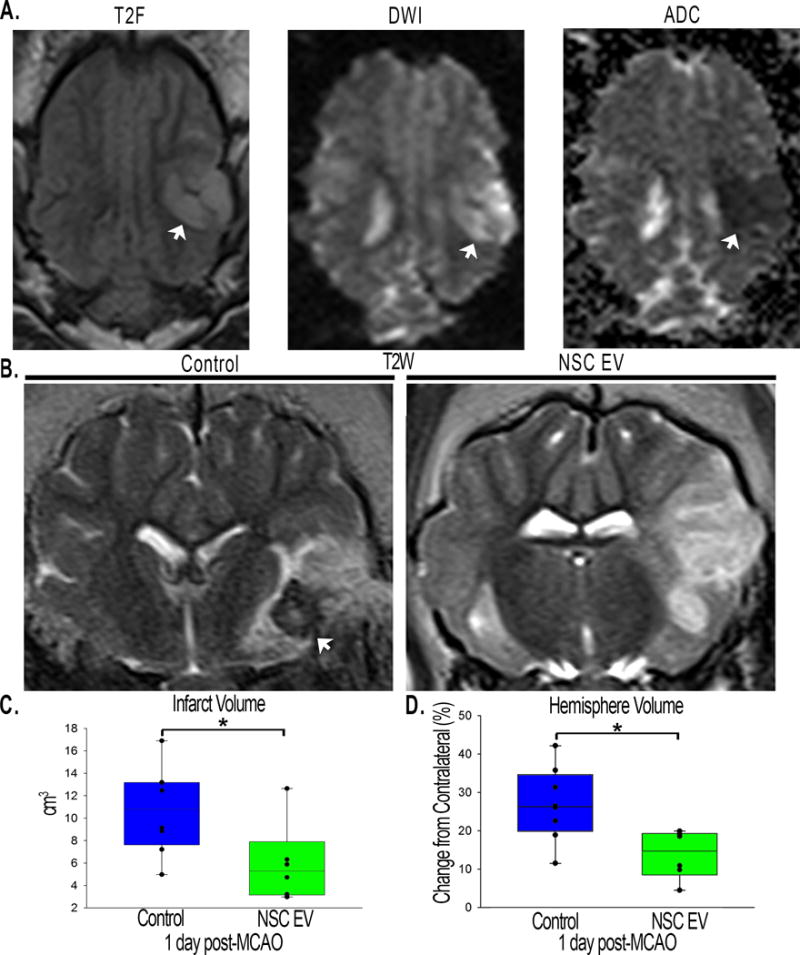

NSC EVs decreased lesion volume and mitigated cerebral swelling 1 day post-MCAO

To confirm ischemic stroke 1 day post-MCAO, MRI T2 Weighted Fluid Attenuated Inversion Recovery (T2FLAIR), and Diffusion Weighted Imaging (DWI) sequences were assessed and exhibited territorial hyperintense lesions characteristic of an edematous injury (Fig. 2A, white arrows). Hypointense lesions observed on corresponding Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (ADC) maps confirmed areas of restricted diffusion indicative of cytotoxic edema (Fig. 2A, white arrows), thus confirming permanent cauterization of the middle cerebral artery (MCA) resulted in ischemic stroke. T2 Weighted (T2W) sequences at 1 day post-MCAO revealed characteristic hyperintense lesions indicative of acute ischemic stroke (Fig. 2B). To account for the space-occupying effect of brain edema, edema-corrected lesion volume (LVc) was calculated utilizing T2W and corresponding ADC maps revealing a significant (p<0.05) decrease in LVc in NSC EV treated pigs when compared to controls (6.0±1.4 vs. 10.7±1.4 cm3 respectively, Fig. 2C). T2W based results also indicated significantly (p≤0.01) decreased swelling of the affected ipsilateral hemisphere resulting in a less pronounced midline shift in NSC EV treated pigs relative to control pigs 1 day post-MCAO (113.7±2.6 vs. 126.8±3.4 % respectively, Fig. 2B, D). Despite these acute changes, there were no significant differences in lesion volume or brain atrophy between treatment groups 84 days post-MCAO (online-only data supplement Fig. III). The occurrence of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) was also substantially reduced in NSC EV treated pigs relative to controls (0/7 and 7/8 pigs, respectively, Fig. 2B, white arrows, online-only data supplement Fig. II).

Figure 2. NSC EV treatment decreases intracranial hemorrhage, lesion volume, and hemispheric swelling 1 day post-MCAO.

T2W and DWI sequences revealed territorial hyperintense lesions characteristic of an edematous injury (A, white arrows). Hypointense lesions observed on corresponding ADC maps confirmed areas of restricted diffusion indicative of cytotoxic edema (A, white arrow). These resulting hallmarks demonstrated permanent cauterization of the ventral aspect of the MCA resulted in bona fide, repeatable ischemic stroke in all pigs. NSC EV treated pigs exhibited a reduced incidence of ICH (B, white arrows). NSC EV treated pigs also demonstrated a significant (p<0.05) decrease in LVc when compared to control pigs at 1 day post-MCAO (6.0±1.4 vs. 10.7±1.4 cm3 respectively; C) and a significantly (p<0.01) lower percent increase in hemisphere volume resulting in a less pronounced midline shift relative to control pigs at 1 day post-MCAO (113.77±2.571 vs. 126.83±3.41 % respectively; D). * indicates significant difference between treatment groups.

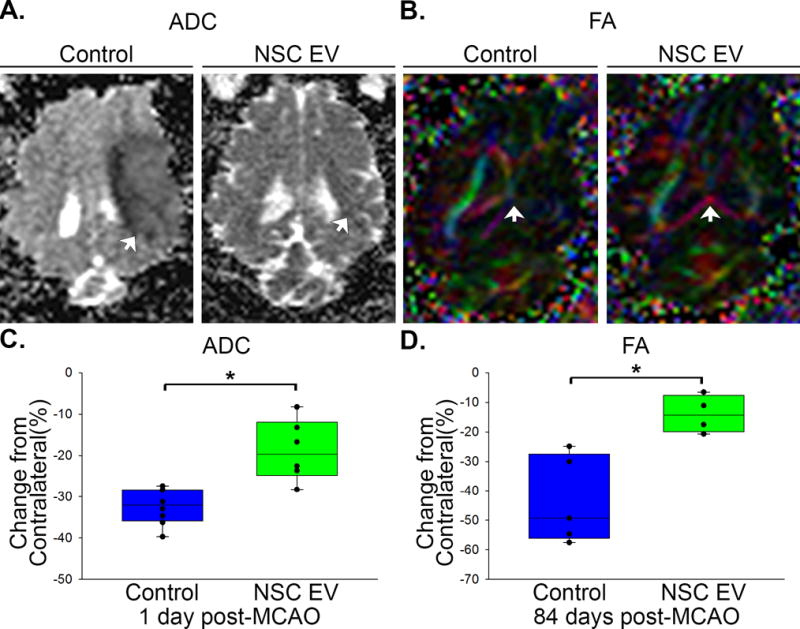

NSC EVs promoted increased diffusivity and white matter integrity 1 and 84 days post-MCAO

Cerebral diffusivity was evaluated utilizing DWI sequences and derived ADC maps. Signal void, consistent with restricted diffusion and indicative of cytotoxic edema was quantified (Fig. 3A, white arrows). Mean ADC values in the affected ipsilateral hemisphere were compared to the contralateral hemisphere with calculated percent changes closer to zero being more similar to normal tissue. NSC EV treated pigs exhibited a significantly (p<0.01) reduced percent change in ADC values when compared to control pigs 1 day post-MCAO (−18.7±2.6 vs. −32.3±1.5 % respectively; Fig. 3C). To assess long-term changes in WM integrity, the corpus callosum was examined 84 days post-MCAO. Changes in FA in the affected ipsilateral hemisphere were again compared to the contralateral hemisphere. FA maps depicted a decrease in the corpus callosum of the ipsilateral hemisphere of control pigs 84 days post-MCAO (Fig. 3B, white arrow), while NSC EV treated pigs exhibited a significantly (p<0.01) lower percent decrease in FA values (−13.9±3.2% vs. −43.3±6.7 %, respectively; Fig. 3D). Collectively, MRI results offered compelling evidence NSC EV treatment provided neuroprotection and promoted tissue level recovery by decreasing cerebral lesion volume, swelling, incidence of ICH, and preserving diffusivity and WM integrity.

Figure 3. NSC EV treatment promotes increased diffusivity of ischemic lesions and preserved white matter integrity of the corpus callosum.

ADC maps derived from DWI sequences revealed signal void indicative of restricted diffusion and cytotoxic edema. NSC EV treated pigs exhibited a significantly (p<0.01) lower percent decrease in ADC values relative to control pigs 1 day post-MCAO (−18.72±2.55 vs. −32.35±1.54 % respectively; A, C, white arrows) suggesting improved diffusivity in ischemic lesions. Color-coded FA maps depicted territorial changes in the corpus callosum 84 days post-MCAO. NSC EV treated pigs exhibited a significantly (p<0.01) lower percent decrease in FA values (−13.94±3.18 vs. −43.29±6.65 % respectively; B, D, white arrows) when compared to control pigs, suggesting preserved white matter integrity. * indicates significant difference between treatment groups.

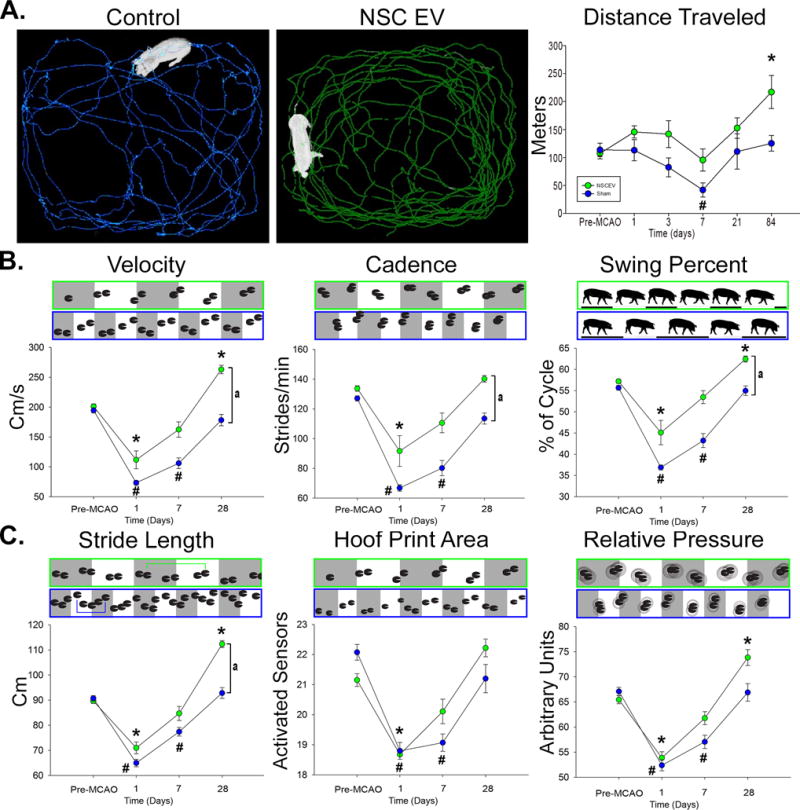

NSC EVs resulted in increased motor activity and exploratory behavior

Exploratory behavior and motor activity pre- and post-MCAO were assessed by open field testing. NSC EV treated pigs did not significantly decrease their distance traveled, while control pigs were less active, compared to pre-MCAO time points (113.6±12.0 vs. 42.0±12.7 m; p<0.01; Fig. 4A). Interestingly, longitudinal analysis at 84 days post-MCAO revealed NSC EV treated pigs exhibited a significant increase in distance traveled compared to their pre-MCAO time points (107.3±9.9 vs. 217.0±29.6 m; p<0.05), however this trend was not observed in control pigs. Together, these findings suggest NSC EVs preserved normal exploratory behaviors and motor activity post-MCAO.

Figure 4. NSC EV treatment results in increased motor activity and improved recovery of spatiotemporal gait parameters.

Ethovision™ XT tracking software was utilized during open field testing to automatically assess differences in distance traveled between treatment groups; representative 10 minute movement tracings shown for control (A, blue) and NSC EV treated (A, green) pigs. Control pigs experienced a significant decrease in distance traveled at 7 days post-MCAO while treated pigs did not. Both groups increased distance traveled over 28 days, however treated pigs traveled significantly further than their pre-MCAO distance while control pigs did not. At 1 day post-MCAO, NSC EV treated and control pigs exhibited significant decreases in temporal gait parameters including velocity, cadence, and swing percent pigs (B). By 7 days post-MCAO, NSC EV treated pigs recovered these parameters while control pigs did not recover until 28 days. At 28 days the NSC EV treated pigs performed significantly better in velocity, cadence, and swing percent than control pigs. Differences in spatial gait parameters were also noted between NSC EV treated and control pigs in terms of stride length, hoof print area, and relative pressure (C). By 7 days post-MCAO, NSC EV treated pigs had recovered from deficits in stride length, hoof print area, and relative pressure, whereas control pigs remained impaired. In addition, NSC EV treated pigs performed significantly better in terms of stride length when compared to control pigs at the same time point. *, # indicates significant (p<0.01) difference between pre- and post-MCAO timepoints. a indicates significant (p<0.01) difference between treatment groups.

NSC EV treatment led to faster and improved recovery of spatiotemporal gait parameters

In addition to exploratory activity, there were several key differences in measured temporal gait parameters between treatment groups. Velocity (distance traveled/second), cadence (strides/minute), and swing percent of cycle (percentage of one full gait cycle in which the contralateral hind limb was in the noncontact phase) significantly decreased 1 day post-MCAO for both NSC EV treated and control pigs. However, by 7 days post-MCAO, NSC EV treated pigs recovered when compared to pre-MCAO performance (Fig. 4B). In contrast, control pigs’ deficits in velocity, cadence and swing percent of cycle persisted through 7 days post-MCAO. By 28 days post-MCAO, NSC EV treated pigs exhibited a significant increase in temporal gait parameters relative to control pigs, thus demonstrating substantial improvement.

Similar functional outcomes in spatial gait parameters were also observed. Stride length (distance between consecutive hoof prints of the contralateral forelimb), hoof print area (measured by the number of activated sensors of the contralateral forelimb), and total scaled pressure (the sum of peak pressure values recorded from each activated sensor by a hoof during contact) decreased similarly in both groups 1 day post-MCAO (Fig. 4C). However, NSC EV treated pigs recovered by 7 days post-MCAO while control pigs remained significantly impaired at the same time points for these spatial parameters, indicating faster recovery.

Discussion

This pivotal study presents the first experimental evidence IV administration of NSC EVs improved tissue and functional level outcomes in a translational porcine ischemic stroke model while adhering to the STEPS and STAIR committee recommendations for developing and testing novel stroke therapeutics3–6, 25, 26. NSC EV intervention led to significant decreases in lesion volume, which has never been observed before in EV-related neural injury studies and has been considered a key biomarker for recovery12, 13, 27, 28. Although EVs were harvested from human NSC EVs, no overt negative immune responses were detected in the porcine model. These data support our recently published data in a thromboembolic mouse model where the injury response to stroke was dampened while augmenting a reparative systemic response favoring macrophage polarization toward anti-inflammatory M2 cells, increasing Treg cells, and decreasing proinflammatory TH17 cells15. In addition, NSC EV therapy led to preserved diffusivity and sustained WM integrity, which strongly correlates with improvements in executive function, cognitive decline, and sensorimotor deterioration, as well as decreased hemispheric swelling and ICH incidence, which are intimately associated with stroke patient morbidity22, 29–33.

Significant decreases in hemispheric swelling and decreased incidence of ICH indicated NSC EV treatment not only preserved cellular integrity in the ischemic site, but also preserved the integrity of microvessels and associated capillary beds 1 day post-MCAO. A recent study of MSC EVs post-MCAO reported increased vascular remodeling in the ischemic boundary zone of rats12. The NSC EV marker profile (Fig. 1D) indicated consistent presence of integrins, including integrin beta-1 (CD29) and integrin alpha 2b (CD41b). Integrin beta-1 is known to mediate cell-to-cell and cell-to-matrix interactions, and regulate cell migration34, 35. Similarly, integrin alpha-2b is a receptor known to bind a variety of ligands leading to rapid platlet aggregation as well as positive regulation of leukocyte migration and megakaryocyte differentiation36, 37. In addition, blockade of integrin alpha-2b (CD41) increases ICH incidence and mortality after transient MCAO in a dose-dependent manner38. By altering the processes of coagulation and vascular function, IV administered NSC EVs may protect the integrity of the blood brain barrier through inherent intercellular signaling components. While the exact molecular mechanism of action is currently unknown, whether dependent on one or multiple EV components or direct action at the systemic level or on the brain directly, this data, in addition to our published rodent study, supports that NSC EVs are biologically active and elicit a positive neuroprotective response in vivo in both rodent and large animal preclinical stroke models15.

A frequently used predictive indicator of patient prognosis is acute lesion volume due to the high correlation between neurological deficits and long-term functional outcomes39–42. Although multiple MSC EV related rodent models of stroke have observed improvements in tissue and functional recovery, the extent of neural protection seen with NSC EV treatment is unprecedented. Previous rodent stroke studies assessing the efficacy of MSC EVs showed no changes in lesion volume12, 13, 27, 28. In comparison, our recently published data indicated a ~35% reduction in lesion volume in the mouse TE-stroke model. Comparatively, our data in the porcine model possessed a significant 44% decrease in lesion volume at 1 day post-MCAO, suggesting NSC EVs are potentially more protective and thus more therapeutically relevant than MSC EVs.

Restoring motor function in stroke patients is critical for improvement in quality of life and is a robust measure of therapeutic potential43–47. Most stroke patients exhibit hemiparesis with correlative asymmetries, decreased velocity, stride length, and other spatiotemporal parameters, therefore it was vital to determine whether these cellular benefits resulted in functional benefits at the organismal level48, 49. To date, no exosome efficacy study has performed a comprehensive assessment of changes in gait function post-stroke. Previous studies have relied on gross measurements (foot fault tests, rotorod), which do not account for fine motor changes in gait as do relative pressure, swing percent, and stride length11, 12. In this study, we found significant changes and decreased recovery time in these and other translational parameters that are critical readouts for human patients. The pig is also likely a more representative model of human gait changes post-stroke when compared to rodents, despite being a quadruped, as weight (pigs in this study were between 72 and 104 kg), limb, and body length are more comparable to humans and are more similarly affected by biomechanical forces generated during normal movement.

In this study, we have demonstrated NSC EVs are a potent biological treatment that positively impact both molecular and functional outcomes post-stroke, while abiding by STEP and STAIR committee recommendations for rigorously developing and testing therapeutics. NSC EVs in our porcine ischemic stroke model exhibited a multifactorial effect leading to decreased lesion volume, hemispheric swelling, and ICH, while also promoting diffusivity, WM integrity, and functional performance in a large animal model with similar cerebral architecture and WM composition to humans. As an effective treatment in both rodent and porcine stroke models, NSC EVs possess inherent biological characteristics suitable for translation into human stroke therapeutics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Simon R. Platt, DVM, who performed the pig permanent occlusion surgeries, as well as Caroline Jackson, Justin Sharma, Austin Passaro, and Viviana Martinez who were involved with various aspects of the EV manufacturing process, pig gait/behavioral testing, and figure preparation. We would also like to thank Tracey Stice for project management guidance. We would also like to thank Julie Nelson at the UGA CTEGD Flow Cytometry Core and Phi Optics for use of the SLIM system.

Funding: This work was supported by ArunA Biomedical, Inc., NINDS grant R43NS103596, NINDS grant R01NS093314, Science and Technology Center Emergent Behaviors of Integrated Cellular Systems (EBICS) Grant No. CBET-0939511, and the Georgia Research Alliance.

Footnotes

Disclosures: R.L.W. and S.L.S. have submitted a patent filing on the NSC EVs, and this technology is licensed from the UGA Research Foundation by ArunA Biomedical, Inc. All authors affiliated with Aruna Biomedical, Inc. own equity in the company.

References

- 1.Cheng NT, Kim AS. Intravenous thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke within 3 hours versus between 3 and 4.5 hours of symptom onset. The Neurohospitalist. 2015;5:101–109. doi: 10.1177/1941874415583116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyle K, Joundi RA, Aviv RI. An historical and contemporary review of endovascular therapy for acute ischemic stroke. Neurovascular Imaging. 2017;3:1. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stem Cell Therapies as an Emerging Paradigm in Stroke P. Stem cell therapies as an emerging paradigm in stroke (steps): Bridging basic and clinical science for cellular and neurogenic factor therapy in treating stroke. Stroke. 2009;40:510–515. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.526863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Savitz SI, Chopp M, Deans R, Carmichael T, Phinney D, Wechsler L, et al. Stem cell therapy as an emerging paradigm for stroke (steps) ii. Stroke. 2011;42:825–829. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.601914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher M, Feuerstein G, Howells DW, Hurn PD, Kent TA, Savitz SI, et al. Update of the stroke therapy academic industry roundtable preclinical recommendations. Stroke. 2009;40:2244–2250. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.541128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saver JL, Albers GW, Dunn B, Johnston KC, Fisher M, Consortium SV Stroke therapy academic industry roundtable (stair) recommendations for extended window acute stroke therapy trials. Stroke. 2009;40:2594–2600. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.552554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lener T, Gimona M, Aigner L, Börger V, Buzas E, Camussi G, et al. Applying extracellular vesicles based therapeutics in clinical trials – an isev position paper. Journal of Extracellular Vesicles. 2015;4:30087. doi: 10.3402/jev.v4.30087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Basso M, Bonetto V. Extracellular vesicles and a novel form of communication in the brain. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 2016;10:127. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2016.00127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raposo G, Stoorvogel W. Extracellular vesicles: Exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2013;200:373. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201211138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.György B, Hung ME, Breakefield XO, Leonard JN. Therapeutic applications of extracellular vesicles: Clinical promise and open questions. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology. 2015;55:439–464. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010814-124630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doeppner TR, Herz J, Gorgens A, Schlechter J, Ludwig AK, Radtke S, et al. Extracellular vesicles improve post-stroke neuroregeneration and prevent postischemic immunosuppression. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2015;4:1131–1143. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2015-0078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xin H, Li Y, Cui Y, Yang JJ, Zhang ZG, Chopp M. Systemic administration of exosomes released from mesenchymal stromal cells promote functional recovery and neurovascular plasticity after stroke in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:1711–1715. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Y, Chopp M, Zhang ZG, Katakowski M, Xin H, Qu C, et al. Systemic administration of cell-free exosomes generated by human bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells cultured under 2d and 3d conditions improves functional recovery in rats after traumatic brain injury. Neurochem Int. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiklander OPB, Nordin JZ, O’Loughlin A, Gustafsson Y, Corso G, Mäger I, et al. Extracellular vesicle in vivo biodistribution is determined by cell source, route of administration and targeting. J extracell vesicles. 2015 doi: 10.3402/jev.v4.26316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Webb RL, Kaiser EE, Scoville SL, Thompson TA, Fatima S, Pandya C, et al. Human neural stem cell extracellular vesicles improve tissue and functional recovery in the murine thromboembolic stroke model. Translational Stroke Research. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s12975-017-0599-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Platt SR, Holmes SP, Howerth EW, Duberstein KJJ, Dove CR, Kinder HA, et al. Development and characterization of a yucatan miniature biomedical pig permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion stroke model. Experimental & Translational Stroke Medicine. 2014;6:5. doi: 10.1186/2040-7378-6-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duberstein KJ, Platt SR, Holmes SP, Dove CR, Howerth EW, Kent M, et al. Gait analysis in a pre- and post-ischemic stroke biomedical pig model. Physiology & Behavior. 2014;125:8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lind NM, Moustgaard A, Jelsing J, Vajta G, Cumming P, Hansen AK. The use of pigs in neuroscience: Modeling brain disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2007;31:728–751. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakamura M, Imai H, Konno K, Kubota C, Seki K, Puentes S, et al. Experimental investigation of encephalomyosynangiosis using gyrencephalic brain of the miniature pig: Histopathological evaluation of dynamic reconstruction of vessels for functional anastomosis. Laboratory investigation. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2009;3:488–495. doi: 10.3171/2008.6.PEDS0834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuluz JW, Prado R, He D, Zhao W, Dietrich WD, Watson B. New pediatric model of ischemic stroke in infant piglets by photothrombosis: Acute changes in cerebral blood flow, microvasculature, and early histopathology. Stroke. 2007;38:1932–1937. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.475244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanaka Y, Imai H, Konno K, Miyagishima T, Kubota C, Puentes S, et al. Experimental model of lacunar infarction in the gyrencephalic brain of the miniature pig: Neurological assessment and histological, immunohistochemical, and physiological evaluation of dynamic corticospinal tract deformation. Stroke. 2008;39:205–212. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.489906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baltan S, Besancon EF, Mbow B, Ye Z, Hamner MA, Ransom BR. White matter vulnerability to ischemic injury increases with age because of enhanced excitotoxicity. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2008;28:1479–1489. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5137-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baker EW, Platt SR, Lau VW, Grace HE, Holmes SP, Wang L, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neural stem cell therapy enhances recovery in an ischemic stroke pig model. Scientific Reports. 2017;7:10075. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10406-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mir M, Kim T, Majumder A, Xiang M, Wang R, Liu SC, et al. Label-free characterization of emerging human neuronal networks. 2014;4:4434. doi: 10.1038/srep04434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fisher M, Stroke Therapy Academic Industry R Recommendations for advancing development of acute stroke therapies: Stroke therapy academic industry roundtable 3. Stroke. 2003;34:1539–1546. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000072983.64326.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Albers GW, Goldstein LB, Hess DC, Wechsler LR, Furie KL, Gorelick PB, et al. Stroke treatment academic industry roundtable (stair) recommendations for maximizing the use of intravenous thrombolytics and expanding treatment options with intra-arterial and neuroprotective therapies. Stroke. 2011;42:2645–2650. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.618850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Otero-Ortega L, Laso-Garcia F, Gomez-de Frutos MD, Rodriguez-Frutos B, Pascual-Guerra J, Fuentes B, et al. White matter repair after extracellular vesicles administration in an experimental animal model of subcortical stroke. Sci Rep. 2017;7:44433. doi: 10.1038/srep44433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y, Chopp M, Meng Y, Katakowski M, Xin H, Mahmood A, et al. Effect of exosomes derived from multipluripotent mesenchymal stromal cells on functional recovery and neurovascular plasticity in rats after traumatic brain injury. Journal of neurosurgery. 2015;122:856–867. doi: 10.3171/2014.11.JNS14770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lovblad KO, Baird AE, Schlaug G, Benfield A, Siewert B, Voetsch B, et al. Ischemic lesion volumes in acute stroke by diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging correlate with clinical outcome. Ann Neurol. 1997;42:164–170. doi: 10.1002/ana.410420206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schellinger PD, Jansen O, Fiebach JB, Hacke W, Sartor K. A standardized mri stroke protocol: Comparison with ct in hyperacute intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 1999;30:765–768. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.4.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahmad AS, Satriotomo I, Fazal J, Nadeau SE, Dore S. Considerations for the optimization of induced white matter injury preclinical models. Front Neurol. 2015;6:172. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2015.00172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jokinen H, Gouw AA, Madureira S, Ylikoski R, van Straaten EC, van der Flier WM, et al. Incident lacunes influence cognitive decline: The ladis study. Neurology. 2011;76:1872–1878. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821d752f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Srikanth V, Beare R, Blizzard L, Phan T, Stapleton J, Chen J, et al. Cerebral white matter lesions, gait, and the risk of incident falls: A prospective population-based study. Stroke. 2009;40:175–180. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.524355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li J, Ballif BA, Powelka AM, Dai J, Gygi SP, Hsu VW. Phosphorylation of acap1 by akt regulates the stimulation-dependent recycling of integrin β1 to control cell migration. Developmental Cell. 2005;9:663–673. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bax DV, Bernard SE, Lomas A, Morgan A, Humphries J, Shuttleworth CA, et al. Cell adhesion to fibrillin-1 molecules and microfibrils is mediated by α5β1 and αvβ3 integrins. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:34605–34616. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303159200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ma YQ, Qin J, Plow EF. Platelet integrin αiibβ3: Activation mechanisms. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2007;5:1345–1352. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Webb DJ, Parsons JT, Horwitz AF. Adhesion assembly, disassembly and turnover in migrating cells – over and over and over again. Nature Cell Biology. 2002;4:E97. doi: 10.1038/ncb0402-e97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kleinschnitz C, Pozgajova M, Pham M, Bendszus M, Nieswandt B, Stoll G. Targeting platelets in acute experimental stroke: Impact of glycoprotein ib, vi, and iib/iiia blockade on infarct size, functional outcome, and intracranial bleeding. Circulation. 2007;115:2323–2330. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.691279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Borsody M, Warner Gargano J, Reeves M, Jacobs B, Group MI-SS Infarction involving the insula and risk of mortality after stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;27:564–571. doi: 10.1159/000214220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huisa BN, Neil WP, Schrader R, Maya M, Pereira B, Bruce NT, et al. Clinical use of computed tomographic perfusion for the diagnosis and prediction of lesion growth in acute ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;23:114–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2012.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schiemanck SK, Kwakkel G, Post MW, Prevo AJ. Predictive value of ischemic lesion volume assessed with magnetic resonance imaging for neurological deficits and functional outcome poststroke: A critical review of the literature. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2006;20:492–502. doi: 10.1177/1545968306289298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tong DC, Yenari MA, Albers GW, O’Brien M, Marks MP, Moseley ME. Correlation of perfusion- and diffusion-weighted mri with nihss score in acute (<6.5 hour) ischemic stroke. Neurology. 1998;50:864–870. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.4.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nascimento LR, de Oliveira CQ, Ada L, Michaelsen SM, Teixeira-Salmela LF. Walking training with cueing of cadence improves walking speed and stride length after stroke more than walking training alone: A systematic review. J Physiother. 2015;61:10–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2014.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hak L, Houdijk H, van der Wurff P, Prins MR, Beek PJ, van Dieen JH. Stride frequency and length adjustment in post-stroke individuals: Influence on the margins of stability. J Rehabil Med. 2015;47:126–132. doi: 10.2340/16501977-1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peterson CL, Hall AL, Kautz SA, Neptune RR. Pre-swing deficits in forward propulsion, swing initiation and power generation by individual muscles during hemiparetic walking. J Biomech. 2010;43:2348–2355. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nolan KJ, Yarossi M, McLaughlin P. Changes in center of pressure displacement with the use of a foot drop stimulator in individuals with stroke. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2015;30:755–761. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2015.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.De Nunzio A, Zucchella C, Spicciato F, Tortola P, Vecchione C, Pierelli F, et al. Biofeedback rehabilitation of posture and weightbearing distribution in stroke: A center of foot pressure analysis. Funct Neurol. 2014;29:127–134. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ng YS, Stein J, Ning M, Black-Schaffer RM. Comparison of clinical characteristics and functional outcomes of ischemic stroke in different vascular territories. Stroke. 2007;38:2309–2314. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.475483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Patterson KK, Parafianowicz I, Danells CJ, Closson V, Verrier MC, Staines WR, et al. Gait asymmetry in community-ambulating stroke survivors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89:304–310. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.08.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.