Abstract

Objective

Reduced blood flow and/or tissue oxygen tension conditions result from thrombotic and vascular diseases such as myocardial infarction, stroke, and peripheral vascular disease. It is largely assumed that while platelet activation is increased by an acute vascular event, chronic vascular inflammation, and/or ischemia, the platelet activation pathways and responses are not themselves changed by the disease process. We therefore sought to determine whether the platelet phenotype is altered by hypoxic and ischemic conditions.

Approach and Results

In a cohort of patients with metabolic and peripheral artery disease (PAD), platelet activity was enhanced and/or inhibition with oral anti-platelet agents was impaired compared to platelets from control subjects, suggesting a difference in platelet phenotype caused by disease. Isolated murine and human platelets exposed to reduced oxygen (hypoxia chamber, 5% O2) had increased expression of some proteins that augment platelet activation compared to platelets in normoxic conditions (21% O2). Using a murine model of critical limb ischemia (CLI), platelet activity was increased even two weeks post-surgery compared to sham surgery mice. This effect was partly inhibited in platelet specific Extracellular Regulated Protein Kinase 5 (ERK5) knockout mice.

Conclusions

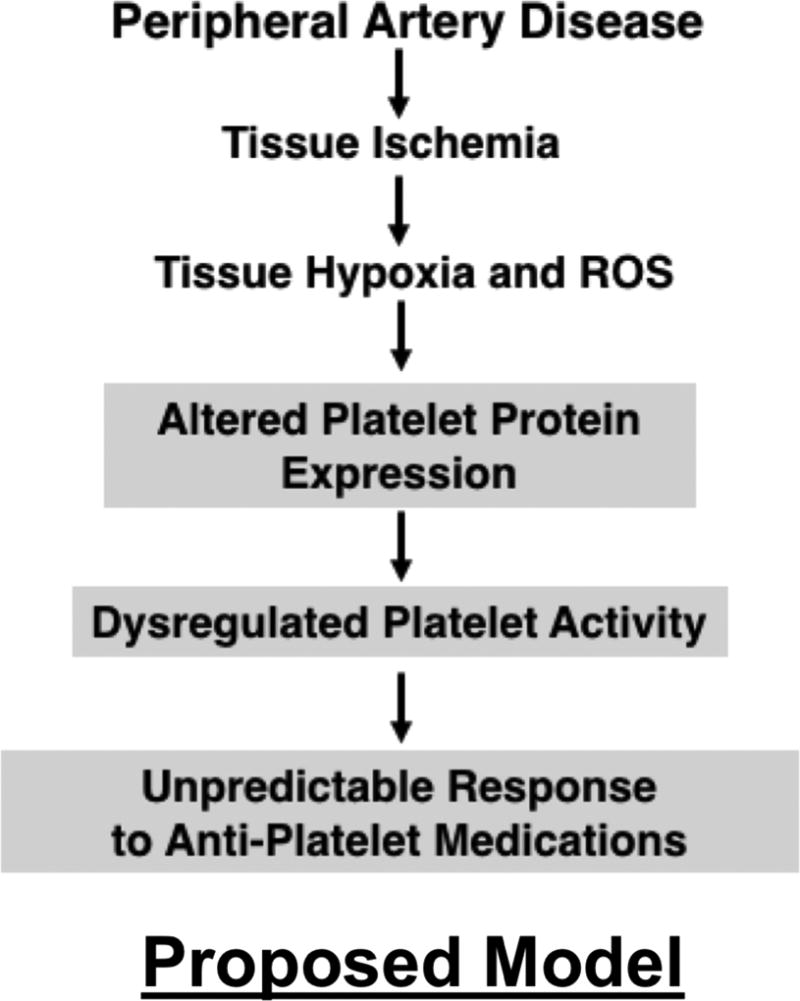

These findings suggest that ischemic disease changes the platelet phenotype and alters platelet agonist responses due to changes in the expression of signal transduction pathway proteins. Platelet phenotype and function should therefore be better characterized in ischemic and hypoxic diseases to understand the benefits and limitations of anti-platelet therapy.

Keywords: Ischemia, Hypoxia, Platelets, Peripheral Artery Disease

Introduction

Platelets are activated in ischemic diseases such as myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, and peripheral artery disease (PAD) 1–4. Anti-platelet agents, including aspirin and clopidogrel, are recommended as part of the disease treatment. The expected anti-thrombotic benefits of anti-platelet agents is not observed in all patients 5–7; some develop unexpected thrombosis 8, while others have bleeding complications 9, 10. Explanations for such treatment failure includes gene polymorphisms in enzymes responsible for anti-platelet drug metabolism or in their receptors, which was reported for the P2Y12 receptor antagonist clopidogrel 11–14. The rationale behind testing for differences in metabolism of anti-platelet agents on an individual basis is that the drug type and dose may be ‘personalized’, providing a more favorable clinical outcome 15. However, reports have indicated that a personalized genetic approach to anti-platelet therapy failed to alter clinical outcomes or the progression of ischemic disease 16, 17.

Pre-clinical platelet inhibitor studies typically utilize platelets isolated from normal volunteers 18. There are risks associated with oversimplifying preclinical platelet studies and extrapolating findings using healthy donor platelets to studies with platelets from a diseased population 19. A prudent research approach may include determining whether the signaling processes in platelets from diseased patients are similar to healthy persons. If platelets from a diseased population have different agonist signaling properties, the design and implementation of anti-platelet agents should be tailored to adjust for these changes. For example, Jurk et al. demonstrated that circulating platelets in patients following stroke are refractory to ex vivo stimulation, engendering an exhausted platelet phenotype 20, suggesting that centreal ischemic vascular disease may lead to the development ‘dysfunctional platelets’.

Using a murine MI model, we recently demonstrated that the circulating platelet phenotype is changed in the post-infarct environment, with a similar observation noted in patients in the peri-MI period 1, 21. We now report that platelet protein expression is altered both in vitro by exposure to hypoxia and in vivo in ischemic disease, demonstrating that the altered platelet phenotype is regulated at least in part at the platelet level. Using both a murine model of critical limb ischemia and platelets from patients with metabolic disease and advanced PAD, we have revealed that platelet post-receptor signaling is altered. These findings suggest a fundamental platelet phenotype switch in ischemic disease not accounted for by current therapeutics.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies and reagents

please refer to the supplemental data section for a full list of all reagents and antibodies used.

Subjects

healthy volunteers, patients with diabetes as indicated by blood hemoglobin A1c concentration > 6.5% with or without peripheral arterial disease (PAD) determined objectively by the ankle brachial index (ABI) were enrolled in this study. Patients with PAD were consented on the day of revascularization either by surgical bypass or by percutaneous intervention for critical limb ischemia. Venous blood was used to isolated PRP. Washed platelets were used for platelet stimulation studies using agonists against the P2Y12 receptor (2-methyl-ADP), PAR1 (TRAP-6), or the thromboxane receptor (U46619), with flow cytometry used to detected activated platelets by surface p-selectin expression as described previously by our group21. This study had the approval of the Research Subjects Review Board (RSRB) of the University of Rochester.

Mouse colony

All animal protocols were approved by the University Committee on Animal Resources (UCAR). Eight week old male wild-type C57BL6/J were used in this study unless indicated. To interrogate the role of platelet ERK5 in some studies, we used ERK5flox/PF4cre(+) (platelet-specific ERK5−/−) mice on a C57BL/6 background previously validated and shown to be deficient only in platelet ERK5. These platelet-specific ERK5−/− mice were matched with ERK5flox/flox mice as a control 1, 22.

Critical Limb Ischemia Model

Mice were anesthetized with 3% isoflurane. A skin incision was made with leg ligations made proximally and distally to the femoris profunda muscle, with 6.0 suture followed by left femoral artery dissection. The skin was closed using 4.0 coated vicryl in a subcuticular fashion. Mice were allowed to recover and returned to housing for up to 28 days. At various time points over this 28 days, mice will also be imaged under isoflurane using a laser Doppler imaging system. Please see the expanded methods in the supplemental data section.

Mouse hemostasis and thrombosis Models

The tail bleeding method was used to assess the time to hemostasis. The ferric chloride-induced platelet activation and mesenteric arterial occlusion model was used to assess thrombosis. Both are described by us previously1.

Mouse Pneumonectomy Model

we performed a left pneumonectomy as described 23 in order to create another model in which the mouse was hypoxic. Please see the expanded methods in the supplemental data section.

Quantification of blood vessels

A volume of two times 250 µL ice cold Matrigel ® which contained all the necessary growth factors to promote angiogenesis was drawn up into pre-chilled 1 mL syringes and injected into the ventral surface of the mouse subcutaneously around the hindlimb area using a 27 g needle. After 7 days, the mouse was sacrificed, and the solidified matrix was removed at which point blood vessels were apparent and so hemoglobin was extracted and quantified according to the instructions using a hemoglobin colorimetric assay (Cayman Chemicals). The other injected solidified matrix was removed and fixed with 10% formalin, then sectioned for H and E staining.

Human Platelet Isolation

For human platelet function studies and for biochemical analysis, venous blood was collected into citrate plasma tubes and mixed, then isolated according our protocol published previously21.

Mouse Platelet Isolation

mouse platelets were collected by 2–3 drops of retro-orbital blood into heparinized Tyrode’s as dscribed by us previously 1. Please see the expanded methods in the supplemental data section.

Biochemistry and protein studies

Cell lysis and cell protein extraction, SDS PAGE, and Western blotting were conducted using buffers and techniques as described previously 1. Please see the expanded methods in the supplemental data section.

Platelet proteomics

Whole blood was collected into citrate plasma tubes and thoroughly mixed. The sample was centrifuged at 1100 rpm for 15 minutes using a bench top centrifuge. The supernatant was then added in a 1:1 (vol/vol) mix of supernatant/Tyrodes solution with final concentration 10 µM prostaglandin I2 (PG I2, Cayman Chemical) and centrifuged at 2600 rpm for 5 minutes using a bench top centrifuge. In an attempt to reduce further contaminating plasma proteins, the supernatant was discarded, and the washed platelet pellet was carefully resuspended in 1 mL fresh Tyrodes solution with 10 µM prostaglandin I2 and centrifuged at 2600 rpm for 5 minutes using a bench top centrifuge. The final platelet pellet was then carefully resuspended in 1 mL fresh Tyrodes solution with 10 µM prostaglandin I2 and centrifuged at 2600 rpm for 5 minutes using a bench top centrifuge one final time. We used CD45 and CD41 antibodies to identify leukocytes and platelets, respectively, and then gated and quantified each individual population as a proportion of all cells, not only those double positive cells. This second QC study revealed even less leukocyte contaminants of PRP (0.12%). The resulting platelet pellet was then used for platelet protein extraction by reducing with 10 mM tris (2-carboxyethyl) phosphine (TCEP) for 1 h at 37 °C, and subsequently alkylated with 12 mM iodoacetamide for 1 hour at room temperature in the dark. Samples were then diluted 1:4 with deionized water and digested with sequencing grade modified trypsin at 1:50 enzyme-to-protein ratio. After 12 hours at 37 °C to promote digestion, another aliquot of the same amount of trypsin was added to the samples and further incubated at 37 °C overnight. The digested samples were then acidified, cleaned up (SCX and C18) and dried as described above. A LC-MS/MS based method for quantitative proteomics using the iTRAQ system reporter ion intensities as we have used previously to study the human platelet proteome and described elsewhere 24, 25.

Statistical Analyses

clinical variables that are dichotomous are presented as frequencies and those that are continuous as mean with standard error of the mean (SEM) unless otherwise stated. The distribution of each data set was interrogated for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test prior to comparison between groups. For non-Gaussian distributed data between two comparative groups, data are graphically represented as median and the Mann-Whitney U test was used to assess for a difference between groups. For three of more groups comparisons, the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn's post test was used. For Gaussian-distributed data between two comparative groups, the t-test was used to assess for a difference between groups. For three or more groups, one-way ANOVA then the Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test was used. Significance was accepted as a P value < 0.05. All data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA.

Results

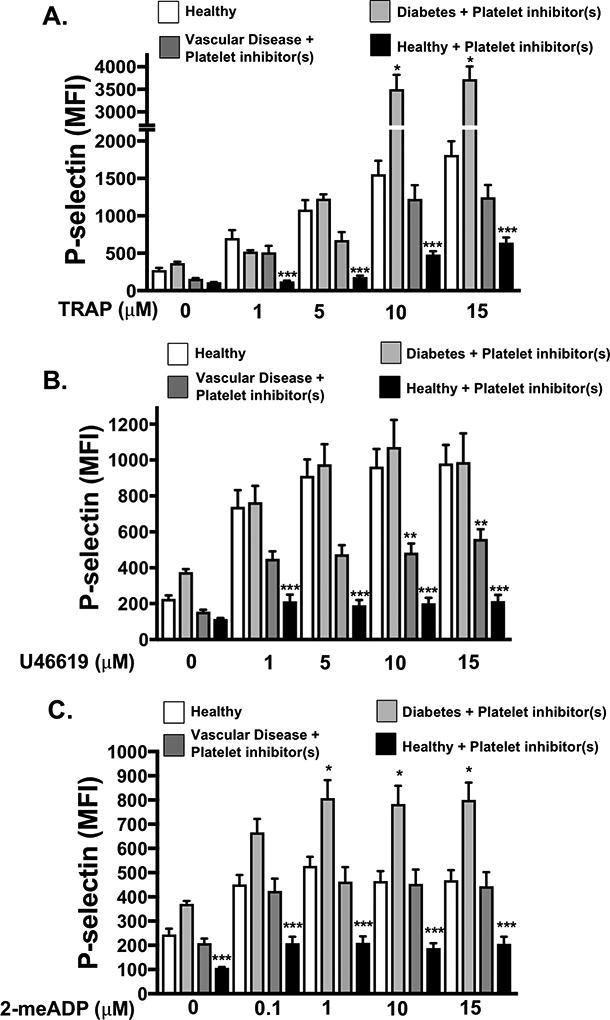

To test whether the platelet phenotype is altered in human vascular and metabolic disease, we isolated platelets from patients with several cardiovascular co-morbidities including peripheral artery disease (PAD), diabetes, and hypertension (referred to as patients with vascular and metabolic disease). We compared platelet function in 30 individuals: either patients or relatively healthy control subjects (Table, SI). We stimulated isolated platelets from healthy control subjects, heathy control subjects taking 81 mg aspirin daily, patients with vascular and metabolic comorbidities with PAD, and from patients with vascular and metabolic comorbidities without PAD (all patients were taking at least one anti-platelet agent). Control subjects taking 81 mg aspirin daily all showed suppression of platelet activity after surface receptor agonist stimulation compared to control subjects without aspirin therapy. However, platelet activation in response to PAR1 and thromboxane receptor stimulation (TRAP6 and U46619, respectively) was not inhibited in patients with vascular and metabolic comorbidities without PAD as we anticipated and, in fact, platelet function was enhanced in response to P2Y12 receptor stimulation (2-meADP) in spite of taking aspirin and clopidogrel. Platelet function in patients with vascular and metabolic comorbidities with PAD was not inhibited by anti-platelet agents in response to receptor agonists as we anticipated compared to control volunteers taking 81 mg aspirin daily (Fig. 1A–C). These data indicate that platelets from patients with metabolic and vascular disease have altered agonist sensitivity and apparent resistance to inhibition by anti-platelet agents compared to platelets from healthy subjects.

Fig 1. Patients with metabolic and vascular disease have dysregulated platelets.

A-C). Platelets from healthy patients (4) and healthy controls taking daily 81 mg aspirin (4) were compared to patients with metabolic and vascular comorbidities including diabetes and PAD taking platelet inhibitors (8), and patients with with diabetes without PAD taking both platelet aspirin and clopidogrel (4). Platelets were stimulated with A) a PAR1 agonist TRAP6, B) a thromboxane receptor agonist U46619 or C) a P2Y12 agonist 2-meADP for 15 mins and activation was assessed by FACS (P-selectin expression, mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05 Healthy vs. diabetes + platelet inhibitors. **P <0.05 Healthy vs. vascular disease + platelet inhibitor(s). *** P<0.05 Healthy vs. healthy + Aspirin, all by one-way ANOVA.

To demonstrate that these observations may in part be due to changes in the platelet themselves, platelet proteomic profiles were assessed by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. Protein expression data in patients with cardiovascular co-morbidities, including PAD, was grouped by function, showing platelet protein expression differences in processes involved in inflammation, RNA processing, protein folding and trafficking, vesicular transport, protease activity, and platelet adhesion (SII-SIII). Less than one half percent leukocyte contamination was seen in PRP isolates (SIV). These data indicate that changes in the platelet phenotype may contribute to anti-platelet drug resistance in patients with vascular and metabolic diseases.

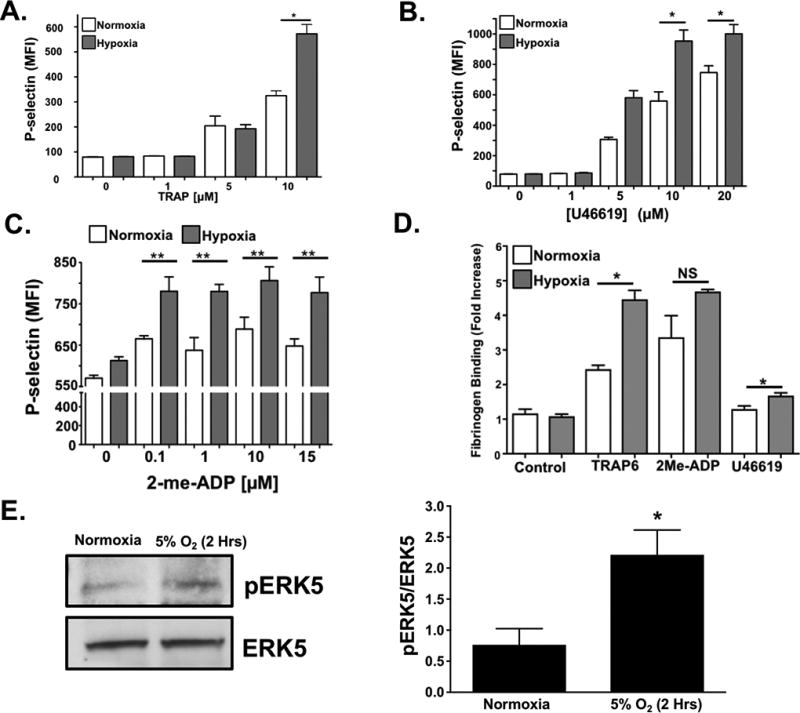

Our prior study demonstrated that platelet protein expression is altered by ischemic disease 1. We therefore considered whether changes in the platelet proteome may in part be due to low tissue oxygen conditions and/or reactive oxygen species generated in those conditions associated with ischemic vascular diseases. Platelets were isolated from healthy subjects and incubated under normoxic (21% O2) or hypoxic (5% O2) conditions for 2 hours prior to stimulation with TRAP6, U46619, or 2-me-ADP. Platelet activation in response to agonist stimulation was enhanced after 2 hours in a hypoxic environment using both surface P-selectin and fibrinogen binding (activated GPIIb/IIIa) as platelet activation markers (Fig. 2 A–D, 30 minute time point showed little change Fig. SV-SVI). We also show that activation o human platelet ERK5, which is a redox sensor, appears to be sustained after 2 hours in a hypoxic environment in vitro (Fig. 2E) These data imply that hypoxia may prime platelets toward an activated state.

Fig 2. Acute Hypoxia Augments Platelet Activation.

Human platelets were isolated and activation was assessed after 2 hrs of in vitro normoxia (21% O2) or hypoxia (5% O2). Platelets were stimulated with A) TRAP6, B) U46619, or C) 2-meADP for 15 mins and P-selectin expression was determined by FACS (mean ± SEM, n=4, *P < 0.05 or **P <0.01 normoxia vs. hypoxia at each agonist concentration by one-way ANOVA. D) Human platelets were isolated and activation was assessed following 2 hrs of normoxia or hypoxia. Platelets were then stimulated with TRAP6 (20 µM), U46619 (20 µM), or 2-me-ADP (10 µM) for 15 mins and activation assessed by FACS for GPIIb/IIIA activation (FITC-Fibrinogen binding, mean ± SEM, n=3, *p < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA, NS=not significant). E. Human platelet ERK5 is activated in normoxia or hypoxia (mean pERK5/ERK5 ± SEM, *p=0.02 by t-test, n=5 in each group).

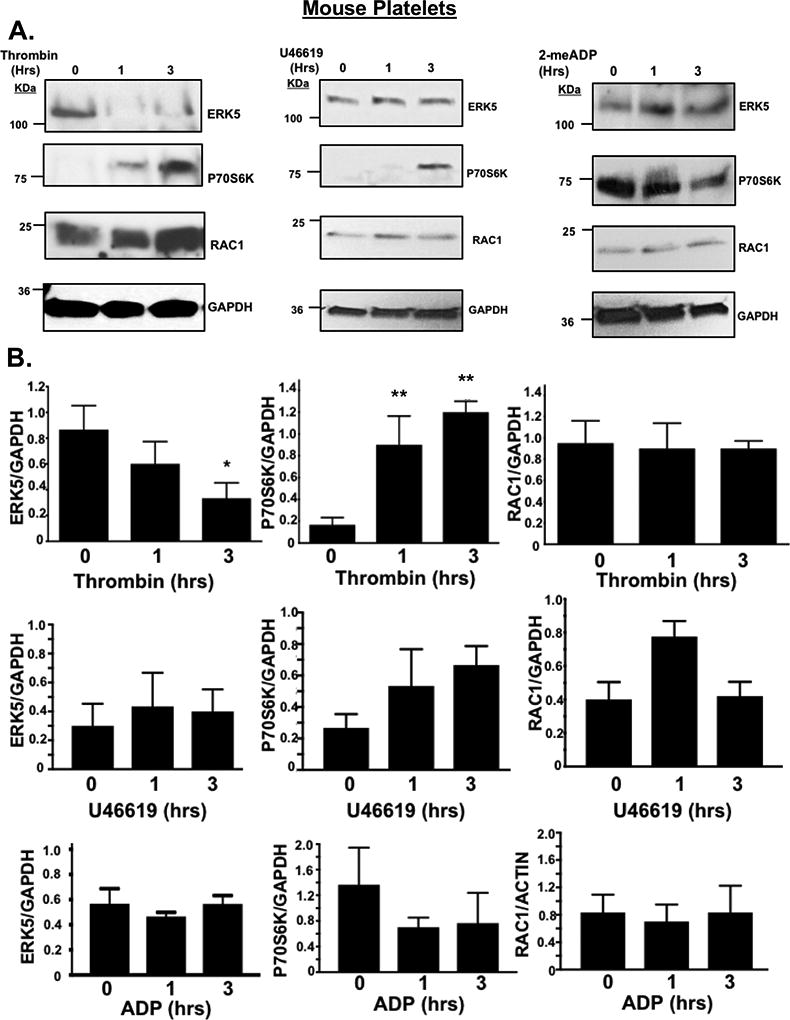

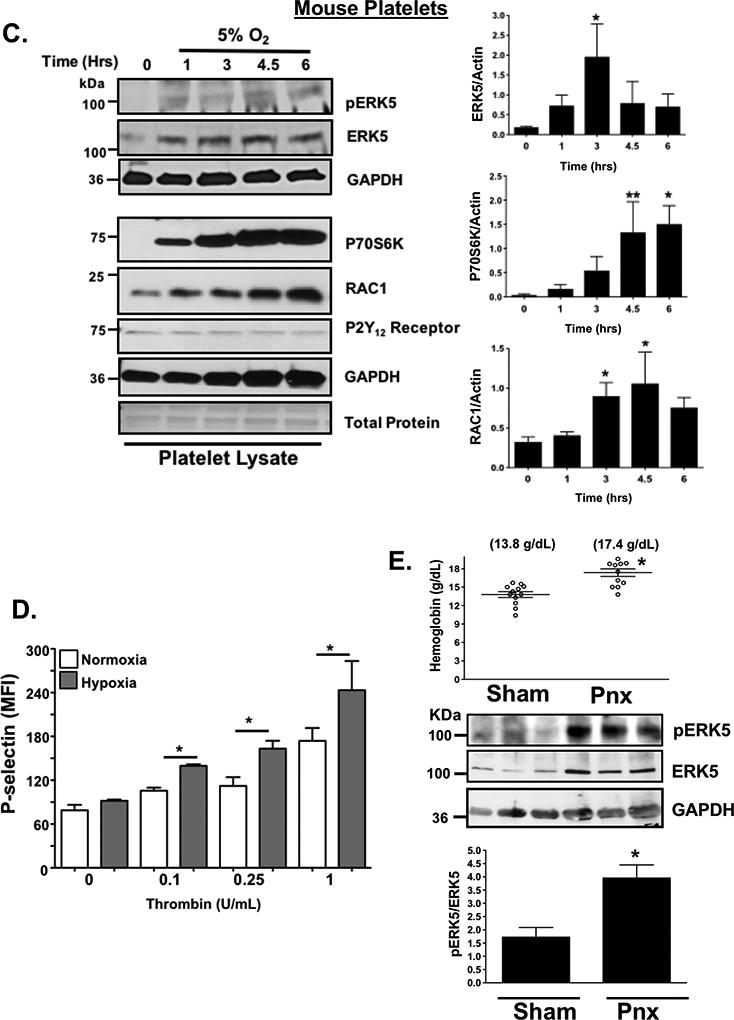

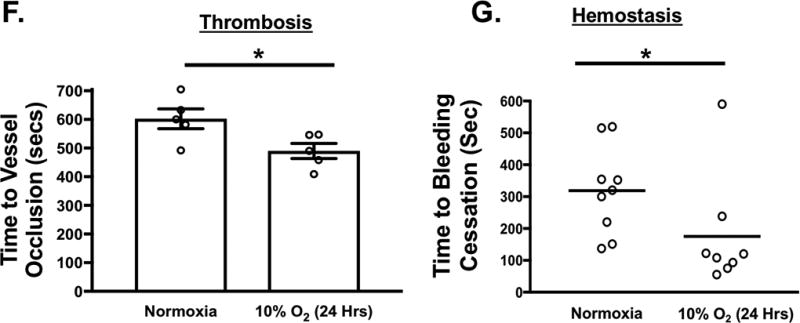

Our prior work using a mouse MI model demonstrated altered platelet protein expression in the post-MI environment, including ERK5, P70S6K, and RAC1 1. To assess whether platelet activation by agonists or hypoxia/ischemia alters the platelet phenotype independent of the megakaryocyte, we isolated mouse platelets and either agonist stimulated platelets or incubated platelets in normoxic (21% O2) or reduced (5% O2) oxygen tension environments in vitro. P70S6K expression was increased by thrombin, though other agonists such as U46619, and ADP did not demonstrate the same effect (Fig. 3 A–B). Hypoxia alone, however, significantly increased the expression of ERK5, P70S6K and RAC1 in a time-dependent manner in mouse platelets (Fig 3C). In vitro hypoxia also augmented thrombin-induced murine platelet activation (Fig. 3D). Mice with either sham operation or unilateral pneumonectomy develop a chronic hypoxic state after 3 weeks as indicated by increased blood hemoglobin concentration with a coincident increased in activation of platelet redox sensor ERK5 in vivo (Fig. 3E), and in vivo hypoxia enhanced thrombosis in a mouse mesenteric injury model (Fig. 3F), and shortened tail bleeding time (Fig. 3G). These data demonstrate that platelet function and protein expression are altered in hypoxia in a manner that may in part be due to platelet protein expression changes or changed in platelet ERK5 activation.

Fig 3. Murine platelet protein expression changes in vitro following agonist stimulation.

A-B) Platelets isolated from mice were stimulated with 0.2 U/mL thrombin, 10 µM U46619 or 10 µM 2-meADP for 1–3 hours. Protein expression was determined by A) immunoblot (IB) and B) quantified by densitometry (mean ± SEM *P= 0.12 vs. 0 for ERK5 (thrombin) and **P<0.05 vs. 0 for P70S6K (thrombin) by one-way ANOVA, n=3). C) Platelets isolated from mice were incubated for 0–6 hrs under hypoxic conditions (5% O2) and platelet protein expression was assessed by IB and quantified by densitometry (mean ± SEM * p< 0.05 or **P=0.058 vs. 0 by one-way ANOVA, n=4–6). D) Platelets were isolated from WT mice and activation was assessed following 6 hrs of normoxia or hypoxia and stimulated with thrombin for 15 mins. Activation was assessed by P-selectin expression (mean ± SEM, n=4, *< 0.05 by one-way ANOVA). E) Left pneumonectomy (Pnx) or sham surgery mice demonstrate hypoxia by a compensatory increase in circulating blood hemoglobin concentration, P=0.0002 by t-test between groups without a change in platelet count (559 ± 44 vs. 604 ± 43 between groups, P=0.48 by t-test, n=12 in each group). Isolated platelets show platelet ERK5 activation (mean pERK5/ERK5 ± SEM, *p=0.009 by t-test, n=4 in each group). F) Mesenteric artery thrombosis was assessed in mice after living for 24 hrs at ambient oxygen or in hypoxic conditions (10% O2, mean time to vessel occlusion ± SEM, n=5 in each group, * p=0.026 by one-way ANOVA for normoxia vs. 10% O2). G) Tail bleeding times as an index of hemostasis were calculated as the time in seconds for bleeding to stop after surgical amputation of the tail tip, median value, n=8–9, * P=0.021 by Mann-Whitney U test for normoxia vs. 10% O2).

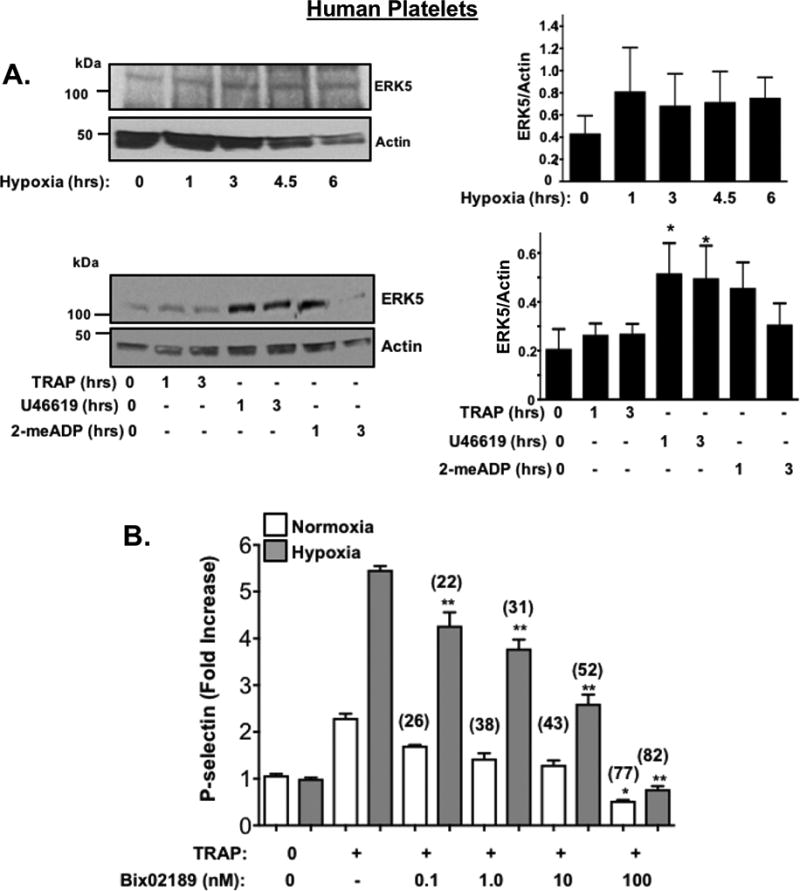

Receptor agonist and hypoxia induced changes in platelet protein expression were also determined using human platelets. We observed that human platelets also exhibited a similar though not identical agonist-specific protein expression change (Fig. 4A, SVII-VIII) while hypoxia induced less change in human platelet proteins compared to murine platelets (Fig. IX–X). These data are consistent with inhibitors of P70S6K and RAC1 having little impact on human platelet post-hypoxia activation (Fig. SXI-XII), but redox-sensitive ERK5, when pharmacologically inhibited following prolonged in vitro hypoxia, demonstrated a significant attenuation of human platelet activation following hypoxia which was not as profoundly obvious in platelets in a normoxic condition (Fig. SXIII, Fig 4B). Finally, human platelets show changes in agonist-induced activation in a hypoxic environment, possibly through additional mechanisms, including increased platelet surface receptor expression available for certain agonists following activation (Fig. SXIV). These experiments demonstrate that platelets alter the expression of key signaling proteins independent of the bone marrow-derived precursor megakaryocyte, particularly in response to hypoxic/ischemic stress. However, the downstream mediators of increased platelet activation may be fundamentally different between murine and human platelets.

Fig. 4. Human platelet protein expression changes in vitro following agonist stimulation.

A) Human platelets were incubated in hypoxic conditions in vitro (5% O2, Top) or stimulated with TRAP (10 µM), U46619 (20 µM) or 2-meADP (10 µM). Platelet protein expression was assessed for ERK5, then quantified by densitometry and reported as mean ± SEM * P<0.05 vs 0 by one-way ANOVA, n=4. B) Human platelets were placed in normoxic or hypoxic conditions for 2hrs in the presence or absence of an ERK5 inhibitor (Bix 02189, 0.1–100 nM) for the last 30 minutes. Platelets were then stimulated with TRAP (10 µM). An ERK5 inhibitor attenuated platelet activation more effectively in hypoxia (% Inhibition with ERK5 inhibitor vs. no ERK5 inhibitor indicated above each condition). * P= 0.040 vs. TRAP alone + normoxia or ** p<0.0001 vs. TRAP alone + hypoxia by one-way ANOVA, n=4).

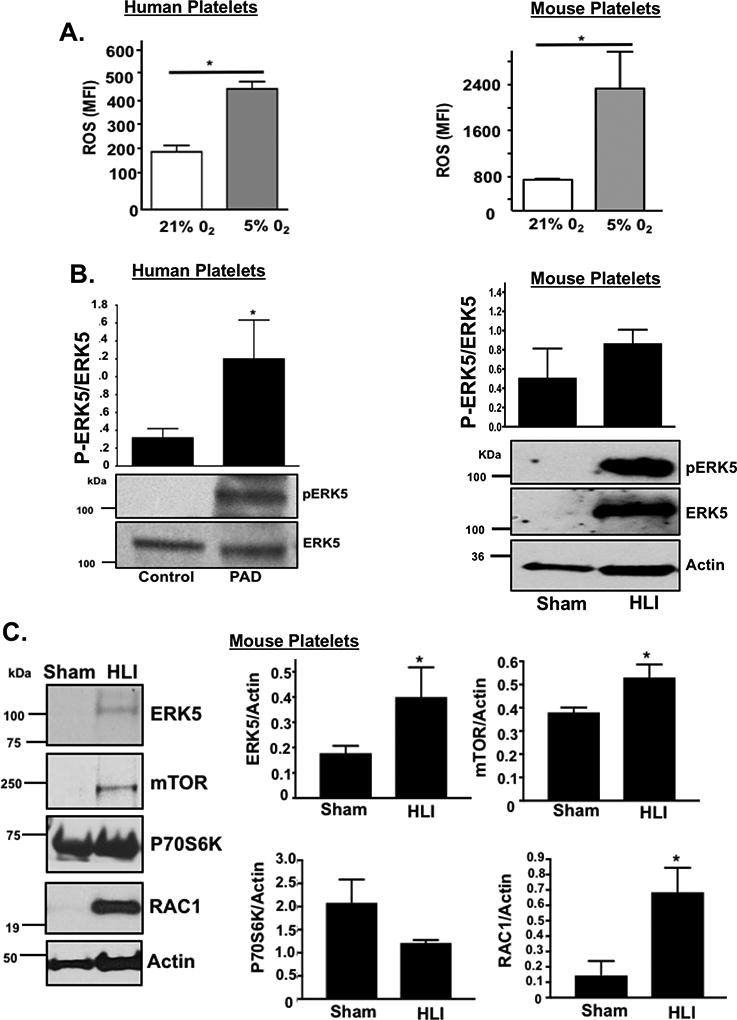

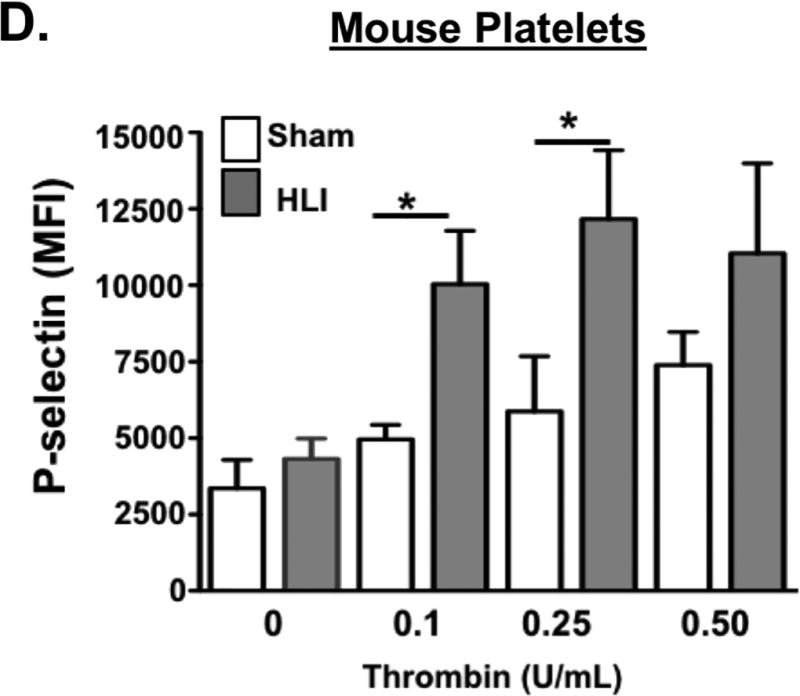

Platelet activation in response to some agonists in a hypoxic environment may be secondary to platelet activation of redox-sensitive protein kinases like ERK5 1, 22, 26. Murine and human platelets both increase endogenous ROS generation in a hypoxic environment (Fig 5A) though the basal and maximal quantity of ROS produced between species also difers. Furthermore, ERK5 activation (P-ERK5, but not total protein expression) was significantly greater in human platelets from patients with PAD (Fig. 5B). ERK5 and other platelet-activating proteins including RAC1 as well as proteins well-known to promote ribosome biogenesis and support translation such as mTOR, were all elevated in murine platelets in a hind limb ischemia (HLI) model (Fig. 5D). This change in murine platelet protein expression coincided with dysregulated platelet activation which was not observed in sham-operated mice, and coincident with lower extremity tissue remodelling and angiogenesis secondary to ischemic injury (Fig. 5D and SXV-XVII) .

Fig. 5. ERK5 promotes dysregulated platelet activity in critical limb ischemia.

A) Platelets isolated from WT mice (left) or healthy humans (right) were incubated for 2 hrs under normoxic conditions (21% O2) or after hypoxia exposure (5% O2) and then loaded with DCFDA to indicate ROS production, quantified by FACS analysis (mean ± S.D.) * p< 0.05 vs. 21% O2 by t-test, n=3 in each group. B) Platelets isolated from humans with PAD or from mice following 4 days of unilateral left leg femoral artery ligation (hind limb ischemia, HLI) or sham surgery were assessed for ERK5 activation using a phospho-specific antibody (p-ERK5). Actin was used as an additional loading control for ERK5 since ERK5 protein content was increased in mice with HLI. ERK5 activation was quantified by densitometry and reported as mean pERK5/ERK5 ± SEM * p=0.025 for control vs. PAD, N=3–4, and p=0.14 for sham vs. HLI mice by t-test, N=4. C) Platelets isolated from mice following 4 days of HLI or sham surgery were assessed for expression of proteins known to affect platelet activation. Protein expression was assessed by immunoblotting (IB), then quantified by densitometry and reported as mean ± SEM * p=0.046 vs. 0 (ERK5), p=0.034 vs. 0 (mTOR) and P=0.022 vs. 0 (RAC1) by t-test, n=3–4 in each group. D) WT mice were subjected to HLI or sham surgery and platelets isolated 7 days later were stimulated with thrombin for 15 mins and activation assessed by FACS (P-selectin expression, mean ± SEM, n=4 in each group by one-way ANOVA, * p < 0.05 between groups).

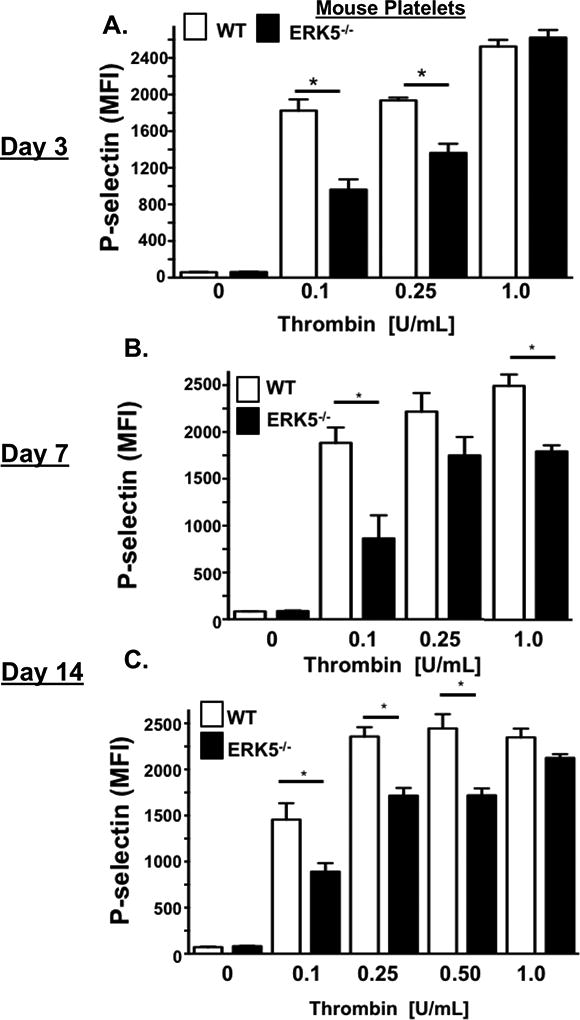

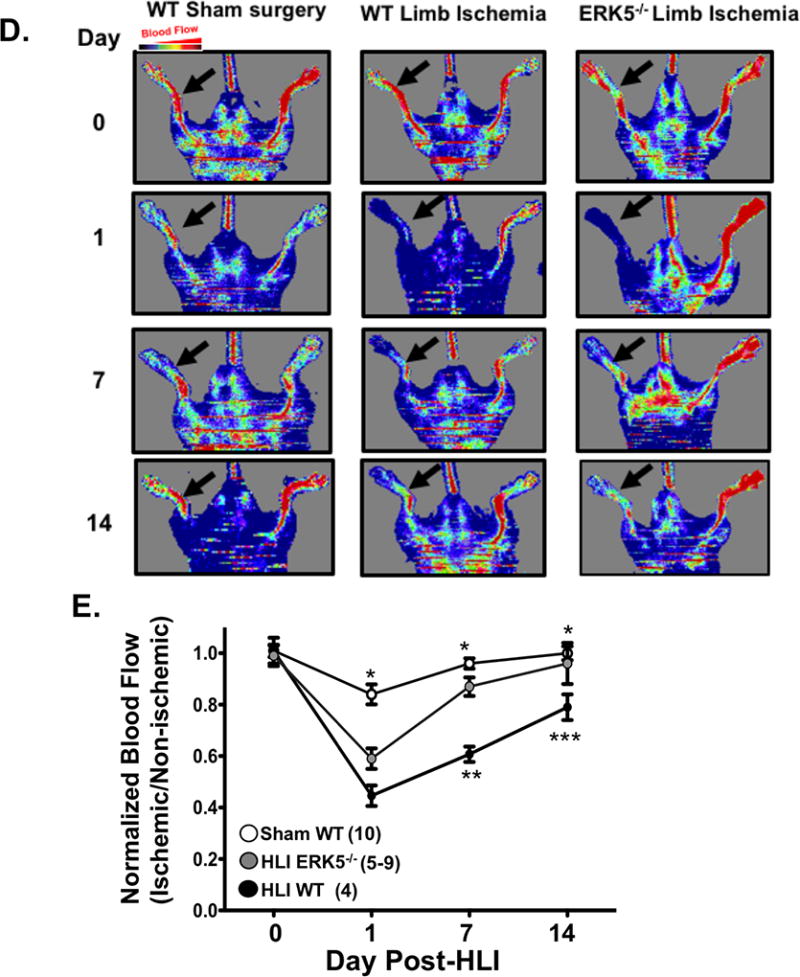

To evaluate a potential functional role for platelet ERK5 in platelet a phenotype alteration associated with ischemia, we performed HLI on WT mice and platelet specific ERK5−/− mice which was previously characterized and shows complete absence of ERK5 protein in isolated PRP which is obviously devoid of ERK5 contaminants from other cell types (SXVIII). Platelets were then isolated from mice on days 3, 7, and 14 post-HLI to assess activation. Platelets from platelet specific ERK5−/− mice had attenuated platelet activation at each of the time points compared to platelets from WT mice (Figure 6 A–C). Thermal laser Doppler imaging of the ischemic limb was also performed weekly to assess for reconstitution of blood flow as is often seen in human patients with advanced PAD. Platelet ERK5−/− mice showed a more rapid recovery of limb blood flow compared to WT mice (Figure 6D–E), with similar platelet counts throughout the ischemic period (Fig. SXIX). To determine whether ERK5−/− mice have improved angiogenesis in general, an in vivo Matrigel assay was used to quantify blood vessel growth in vivo in WT and platelet ERK5−/− mice. Vascular content was surprisngly similar in WT and platelet ERK5−/− mice (extracted hemoglobin concentration 1.53 ± 0.48 g/dL vs. 1.18 ± 0.15 g/dL) implying that the more rapid reconstitution of hind limb blood flow in platelet ERK5−/− mice is due to mechanisms other than enhanced angiogenesis, and potentially may include alterations in microvascular thrombosis. Together these data demonstrate that ischemic disease leads to a platelet phenotype that is more sensitive to agonist stimulation, and activation of platelet ERK5 may have a central role in this response (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6. Platelet ERK5 inhibition improved blood flow in critical limb ischemia.

A-C) WT or ERK5−/− platelets from mice A) 3 B) 7 or C) 14 days after HLI were isolated and stimulated with thrombin for 15 mins and activation assessed by FACS. WT platelets had more post-HLI activation compared to ERK5−/− (P-selectin expression, mean ± SEM, n=4, * P < 0.01between groups by one-way ANOVA). D-E) Thermal Doppler color imaging showed more rapid return of blood flow in ERK5−/− mouse limbs. D) Representative images, E) quantification (mean ratio in the ischemic:non-ischemic limb ± SEM *P <0.001 Sham WT vs WT HLI, ** P=0.013 WT HLI vs ERK5 −/− HLI, ***p=0.003 WT HLI vs. ERK5 −/− HLI all by one-way ANOVA. The group population size is indicated in parentheses.

Fig. 7. Proposed Model.

Discussion

These data demonstrate that in both humans and mouse models, metabolic and vascular disease alters the platelet phenotype. Human diseases and extreme experimental conditions of ischemia and hypoxia revealed differences in platelet surface receptor expression, agonist sensitivity, post-receptor signal transduction, and proteomic profiles which could alter the response of the platelet to environmental and pharmacologic stimuli. This may provide mechanistic insight into the unpredictable patient responses to anti-platelet agents in hypoxic and ischemic diseases 21, 27, 28. The expectation that the platelet phenotype in a diseased state closely resembles healthy conditions may be incorrect. Preclinical studies evaluating anti-platelet agents therefore ought to include both healthy donors and donors with metabolic and vascular disease since platelet antagonists presently available do not account for an evolving, disease-dependent platelet phenotype. The ‘platelet phenotypic switch’ observed in diseased conditions may in part explain unpredictable platelet responses previously ascribed to changes in anti-platelet drug metabolism or platelet receptor variants 17, 29, 30. Resistance to anti-platelet therapeutic agents has been described in diabetics, in MI, and in patients with PAD 31. Explanations for such ‘treatment failure’ may include metabolic co-morbidities which alter the inflammatory environment, the metabolism of anti-platelet agents, and interactions of anti-platelet agents with other drugs 32–36. Comparing differences in the platelet phenotype between clinical groups is challenging given the difficulty in exactly matching control human populations in a complex disease group such as PAD, where the clinical pathology leading to the vascular injury is multi-factorial.

A few studies showed that platelets from diseased populations may have altered surface receptor expression, implying a change in the mature platelet proteome 37–39. Our data offer some mechanistic explanations for these observations since we demonstrate an adaptive platelet phenotype in models of ischemia. This includes changes in platelet receptor agonist sensitivity and the expression and activation of post-receptor signal transduction proteins. While we in fact observe some important differences in human compared to murine responses to hypoxia, platelet ERK5 appears to be a common mediator of dysregulated platelet activation in both species.

In as little as a few hours, we found changes in the expression of platelet proteins in vitro in a hypoxic environment or after a few days in vivo following limb ischemia that coincide with enhanced sensitivity to multiple platelet surface receptor agonists. We also show that the platelet proteome in patients with advanced vascular disease is not the same as in relatively healthy subjects, with the former demonstrating more sigmaling proteins involved in protein synthesis, inflammation, and thrombosis (SII-III) These data extend prior observations in experimental models of extreme hypoxia in vitro and in models of venous thrombosis and sickle cell disease which all show increased platelet activation 40–42. The change in platelet function observed in just a few hours in vitro may be sufficient to tip the balance of platelet protein synthesis and degradation toward an activated phenotype 43, 44. Previous studies indicate that P70S6K and RAC1 are involved in platelet cytoskeletal rearrangement and activation 45–47. We previously showed that platelet ERK5 is a regulator of protein stability and platelet function in the inflammatory post-MI environment and that platelet specific ERK5−/− mice have attenuated platelet activation post-MI with reduced expression of P70S6K and RAC1 1. Our current study supports these prior observations by demonstrating markedly increased murine platelet P70S6K protein expression following in vitro hypoxia , independent of the megakaryocyte. Ribosomal protein S6 promotes protein translation efficiency may be especially important in ischemic disease 48, 49. There is also the tantalizing possibility that platelet mRNA stability is markedly altered in different diseases with consequences on the final platelet translatome and subsequent proteome. It is tempting to speculate P70S6K is an ERK5 downstream mediator of dysregulated platelet activity in murine platelets under hypoxic conditions. An important observation in our investigation is that human and murine platelets, while similar in may ways, do in fact show clear differences in their responses to environmental cues that drive post-receptor signaling pathways and translation efficiency in vitro. These observations serve as a gentle reminder to investigators that experimental models, even when conducted rigororusly, sometimes lack important features of human pathophysiology, which limits their ability to reveal a therapeutic solution for diseases.

Patients with vascular diseases such as PAD have more on-treatment thrombotic events compared to other thrombotic diseases 50, 51. A recent report indicates diabetic platelets have dysregulated P2Y12 receptor signaling which was independently replicated in the present study of isolated platelets from humans with metabolic and vascular co-morbidities including diabetes and advanced PAD 52. PAD is common in diabetic patients and two thirds of the patients in our study had diabetes. In support of other studies, despite taking daily platelet inhibitors, platelets from patients with PAD could be activated through several platelet receptor signaling pathways, and especially through the P2Y12 receptor. In the analogous murine HLI mode we show that platelets are markedly more activated by agonists compared to sham-operated animals and this phenotype is partly reversed in platelet ERK5−/− mice. We were quite surprised to observe that platelet ERK5−/− mice also showed enhanced blood flow in the weeks following HLI compared to WT mice. These findings imply ERK5 inhibition may decrease small vessel thrombotic burden in the early ischemic limb, promoting blood flow.

Our investigation has some limitations. While we show that patients with metabolic and vascular disease have a different platelet phenotype and appear to be somewhat resistant to anti-platelet medications, our control subjects had fewer comorbidities than those patients with diabetes and PAD, and there was an imbalance in representation of sex among some groups. These present as potential confounding variables in data interpretation. A better and more direct correlation of these human and mouse data will require a larger cohort, ideally compared with control subjects with exactly matched co-morbidities. However, these human disease-based data are only intended to highlight the basic conclusion of our study that the platelet phenotype is changed in vascular disease processes and that this may in part be due to changes in the platelet itself as well as in the vascular compartment.

In summary, the present study confirms that metabolic and ischemic stressors alter platelet signal transduction pathways and subsequent agonist responsiveness. This may in part be regualated at the level of the platelet itself, independent of the megakaryocyte. A concerted effort should be made to personalize anti-platelet therapy, not only with respect to race and sex, but also to the thrombotic disease in question.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Platelets regulate protein expresssion in response to environmental cues which changes their sensitivity to activation and threshold for inhibition by anti-platelet agents.

ERK5 is a mediator of ischemic platelet activation.

Platelet dysfunction is dependent on ERK5 in ischemic disease models.

Acknowledgments

Scott J. Cameron and Craig Morrell, performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote manuscript. Sara Ture, Rachel Schmidt, Amy Mohan, Daphne Pariser, Punit Shah, Lijun Chen, Hui Zhang, David J. Field, Kristina L. Modjeski, performed experiments and analyzed data. Doran S. Mix, Michael Stoner, and Sandra Toth were involved in study conception and assisted in acquiring platelets from human donors as well as analyzing clinical data.

Sources of Funding: NIH grants 5T32HL066988-1, NIH 2K08HL128856 and HL12020 to SJC, the Sable Heart Fund (Independent Order of Oddfellows) and the University of Rochester Department of Medicine Pilot Grant to SJC, NIH 5R01HL124018 and AHA 13EIA14250023 to CNM.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None of the authors have any relevant discosures.

References

- 1.Cameron SJ, Ture SK, Mickelsen D, Chakrabarti E, Modjeski KL, McNitt S, Seaberry M, Field DJ, Le NT, Abe J, Morrell CN. Platelet extracellular regulated protein kinase 5 is a redox switch and triggers maladaptive platelet responses and myocardial infarct expansion. Circulation. 2015;132:47–58. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.015656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aronow H, Hiatt WR. The burden of peripheral artery disease and the role of antiplatelet therapy. Postgrad Med. 2009;121:123–135. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2009.07.2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curzen N, Gurbel PA, Myat A, Bhatt DL, Redwood SR. What is the optimum adjunctive reperfusion strategy for primary percutaneous coronary intervention? Lancet. 2013;382:633–643. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61453-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cherian P, Hankey GJ, Eikelboom JW, Thom J, Baker RI, McQuillan A, Staton J, Yi Q. Endothelial and platelet activation in acute ischemic stroke and its etiological subtypes. Stroke. 2003;34:2132–2137. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000086466.32421.F4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Geffen JP, Kleinegris MC, Verdoold R, Baaten CC, Cosemans JM, Clemetson KJ, Ten Cate H, Roest M, de Laat B, Heemskerk JW. Normal platelet activation profile in patients with peripheral arterial disease on aspirin. Thromb Res. 2015;135:513–520. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2014.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petzold T, Thienel M, Konrad I, Schubert I, Regenauer R, Hoppe B, Lorenz M, Eckart A, Chandraratne S, Lennerz C, Kolb C, Braun D, Jamasbi J, Brandl R, Braun S, Siess W, Schulz C, Massberg S. Oral thrombin inhibitor aggravates platelet adhesion and aggregation during arterial thrombosis. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:367ra168. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad6712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ault KA, Cannon CP, Mitchell J, McCahan J, Tracy RP, Novotny WF, Reimann JD, Braunwald E. Platelet activation in patients after an acute coronary syndrome: Results from the timi-12 trial. Thrombolysis in myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:634–639. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00635-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park DW, Yun SC, Lee SW, Kim YH, Lee CW, Hong MK, Cheong SS, Kim JJ, Park SW, Park SJ. Stent thrombosis, clinical events, and influence of prolonged clopidogrel use after placement of drug-eluting stent data from an observational cohort study of drug-eluting versus bare-metal stents. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;1:494–503. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carrabba N, Parodi G, Marcucci R, Valenti R, Gori AM, Migliorini A, Comito V, Bellandi B, Abbate R, Gensini GF, Antoniucci D. Bleeding events and maintenance dose of prasugrel: Bless pilot study. Open Heart. 2016;3:e000460. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2016-000460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Committee CS. A randomised, blinded, trial of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events (caprie). Caprie steering committee. Lancet. 1996;348:1329–1339. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)09457-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tantry US, Jeong YH, Navarese EP, Kubica J, Gurbel PA. Influence of genetic polymorphisms on platelet function, response to antiplatelet drugs and clinical outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2013;11:447–462. doi: 10.1586/erc.13.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zoheir N, Abd Elhamid S, Abulata N, El Sobky M, Khafagy D, Mostafa A. P2y12 receptor gene polymorphism and antiplatelet effect of clopidogrel in patients with coronary artery disease after coronary stenting. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2013;24:525–531. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0b013e32835e98bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ulehlova J, Slavik L, Kucerova J, Krcova V, Vaclavik J, Indrak K. Genetic polymorphisms of platelet receptors in patients with acute myocardial infarction and resistance to antiplatelet therapy. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2014;18:599–604. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2014.0077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bierend A, Rau T, Maas R, Schwedhelm E, Boger RH. P2y12 polymorphisms and antiplatelet effects of aspirin in patients with coronary artery disease. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;65:540–547. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.03044.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sibbing D, Braun S, Morath T, Mehilli J, Vogt W, Schomig A, Kastrati A, von Beckerath N. Platelet reactivity after clopidogrel treatment assessed with point-of-care analysis and early drug-eluting stent thrombosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:849–856. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doll JA, Neely ML, Roe MT, Armstrong PW, White HD, Prabhakaran D, Winters KJ, Duvvuru S, Sundseth SS, Jakubowski JA, Gurbel PA, Bhatt DL, Ohman EM, Fox KA, Investigators TA. Impact of cyp2c19 metabolizer status on patients with acs treated with prasugrel versus clopidogrel. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:936–947. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siller-Matula JM, Trenk D, Schror K, Gawaz M, Kristensen SD, Storey RF, Huber K, Epa Response variability to p2y12 receptor inhibitors: Expectations and reality. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6:1111–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2013.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nicholson NS, Panzer-Knodle SG, Haas NF, Taite BB, Szalony JA, Page JD, Feigen LP, Lansky DM, Salyers AK. Assessment of platelet function assays. Am Heart J. 1998;135:S170–178. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(98)70245-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schultze AE, Walker DB, Turk JR, Tarrant JM, Brooks MB, Pettit SD. Current practices in preclinical drug development: Gaps in hemostasis testing to assess risk of thromboembolic injury. Toxicol Pathol. 2013;41:445–453. doi: 10.1177/0192623312460924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jurk K, Jahn UR, Van Aken H, Schriek C, Droste DW, Ritter MA, Bernd Ringelstein E, Kehrel BE. Platelets in patients with acute ischemic stroke are exhausted and refractory to thrombin, due to cleavage of the seven-transmembrane thrombin receptor (par-1) Thromb Haemost. 2004;91:334–344. doi: 10.1160/TH03-01-0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmidt RA, Morrell CN, Ling FS, Simlote P, Fernandez G, Rich DQ, Adler D, Gervase J, Cameron SJ. The platelet phenotype in patients with st-segment elevation myocardial infarction is different from non-st-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Transl Res. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2017.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang M, Cooley BC, Li W, Chen Y, Vasquez-Vivar J, Scoggins NO, Cameron SJ, Morrell CN, Silverstein RL. Platelet cd36 promotes thrombosis by activating redox sensor erk5 in hyperlipidemic conditions. Blood. 2017;129:2917–2927. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-11-750133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sakurai MK, Greene AK, Wilson J, Fauza D, Puder M. Pneumonectomy in the mouse: Technique and perioperative management. J Invest Surg. 2005;18:201–205. doi: 10.1080/08941930591004485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang H, Liu T, Zhang Z, Payne SH, Zhang B, McDermott JE, Zhou JY, Petyuk VA, Chen L, Ray D, Sun S, Yang F, Chen L, Wang J, Shah P, Cha SW, Aiyetan P, Woo S, Tian Y, Gritsenko MA, Clauss TR, Choi C, Monroe ME, Thomas S, Nie S, Wu C, Moore RJ, Yu KH, Tabb DL, Fenyo D, Bafna V, Wang Y, Rodriguez H, Boja ES, Hiltke T, Rivers RC, Sokoll L, Zhu H, Shih Ie M, Cope L, Pandey A, Zhang B, Snyder MP, Levine DA, Smith RD, Chan DW, Rodland KD, Investigators C. Integrated proteogenomic characterization of human high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Cell. 2016;166:755–765. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shah P, Yang W, Sun S, Pasay J, Faraday N, Zhang H. Platelet glycoproteins associated with aspirin-treatment upon platelet activation. Proteomics. 2016 doi: 10.1002/pmic.201600199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng Z, Gao W, Fan X, Chen X, Mei H, Liu J, Luo X, Hu Y. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 5 associates with casein kinase ii to regulate gpib-ix-mediated platelet activation via the pten/pi3k/akt pathway. J Thromb Haemost. 2017 doi: 10.1111/jth.13755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wisman PP, Teraa M, de Borst GJ, Verhaar MC, Roest M, Moll FL. Baseline platelet activation and reactivity in patients with critical limb ischemia. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0131356. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rajagopalan S, McKay I, Ford I, Bachoo P, Greaves M, Brittenden J. Platelet activation increases with the severity of peripheral arterial disease: Implications for clinical management. J Vasc Surg. 2007;46:485–490. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Edelstein LC, Simon LM, Lindsay CR, Kong X, Teruel-Montoya R, Tourdot BE, Chen ES, Ma L, Coughlin S, Nieman M, Holinstat M, Shaw CA, Bray PF. Common variants in the human platelet par4 thrombin receptor alter platelet function and differ by race. Blood. 2014;124:3450–3458. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-04-572479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kong X, Simon LM, Holinstat M, Shaw CA, Bray PF, Edelstein LC. Identification of a functional genetic variant driving racially dimorphic platelet gene expression of the thrombin receptor regulator, pctp. Thromb Haemost. 2017;117:962–970. doi: 10.1160/TH16-09-0692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cleator JH, Duvernay MT, Holinstat M, Colowick NE, Hudson WJ, Song Y, Harrell FE, Hamm HE. Racial differences in resistance to p2y12 receptor antagonists in type 2 diabetic subjects. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2014;351:33–43. doi: 10.1124/jpet.114.215616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hagihara K, Kazui M, Kurihara A, Yoshiike M, Honda K, Okazaki O, Farid NA, Ikeda T. A possible mechanism for the differences in efficiency and variability of active metabolite formation from thienopyridine antiplatelet agents, prasugrel and clopidogrel. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37:2145–2152. doi: 10.1124/dmd.109.028498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scott SA, Sangkuhl K, Gardner EE, Stein CM, Hulot JS, Johnson JA, Roden DM, Klein TE, Shuldiner AR, Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation C. Clinical pharmacogenetics implementation consortium guidelines for cytochrome p450-2c19 (cyp2c19) genotype and clopidogrel therapy. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;90:328–332. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hulot JS, Bura A, Villard E, Azizi M, Remones V, Goyenvalle C, Aiach M, Lechat P, Gaussem P. Cytochrome p450 2c19 loss-of-function polymorphism is a major determinant of clopidogrel responsiveness in healthy subjects. Blood. 2006;108:2244–2247. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-013052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bonello L, Tantry US, Marcucci R, Blindt R, Angiolillo DJ, Becker R, Bhatt DL, Cattaneo M, Collet JP, Cuisset T, Gachet C, Montalescot G, Jennings LK, Kereiakes D, Sibbing D, Trenk D, Van Werkum JW, Paganelli F, Price MJ, Waksman R, Gurbel PA Working Group on High On-Treatment Platelet R. Consensus and future directions on the definition of high on-treatment platelet reactivity to adenosine diphosphate. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:919–933. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Labuz-Roszak B, Pierzchala K, Tyrpien K. Resistance to acetylsalicylic acid in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus is associated with lipid disorders and history of current smoking. J Endocrinol Invest. 2014;37:331–338. doi: 10.1007/s40618-013-0012-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lanza GA, Aurigemma C, Fattorossi A, Scambia G, Crea F. Changes in platelet receptor expression and leukocyte-platelet aggregate formation following exercise in cardiac syndrome x. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:1623–1625. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Floyd CN, Goodman T, Becker S, Chen N, Mustafa A, Schofield E, Campbell J, Ward M, Sharma P, Ferro A. Increased platelet expression of glycoprotein iiia following aspirin treatment in aspirin-resistant but not aspirin-sensitive subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;78:320–328. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaywin P, McDonough M, Insel PA, Shattil SJ. Platelet function in essential thrombocythemia. Decreased epinephrine responsiveness associated with a deficiency of platelet alpha-adrenergic receptors. N Engl J Med. 1978;299:505–509. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197809072991002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brill A, Suidan GL, Wagner DD. Hypoxia, such as encountered at high altitude, promotes deep vein thrombosis in mice. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11:1773–1775. doi: 10.1111/jth.12310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nwankwo JO, Gremmel T, Gerrits AJ, Mithila FJ, Warburton RR, Hill NS, Lu Y, Richey LJ, Jakubowski JA, Frelinger AL, 3rd, Chishti AH. Calpain-1 regulates platelet function in a humanized mouse model of sickle cell disease. Thromb Res. 2017;160:58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2017.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rubenstein DA, Yin W. Hypergravity and hypobaric hypoxic conditions promote endothelial cell and platelet activation. High Alt Med Biol. 2014;15:396–405. doi: 10.1089/ham.2013.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gupta N, Li W, McIntyre TM. Deubiquitinases modulate platelet proteome ubiquitination, aggregation, and thrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:2657–2666. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Srikanthan S, Li W, Silverstein RL, McIntyre TM. Exosome poly-ubiquitin inhibits platelet activation, downregulates cd36 and inhibits pro-atherothombotic cellular functions. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12:1906–1917. doi: 10.1111/jth.12712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Akbar H, Duan X, Saleem S, Davis AK, Zheng Y. Rhoa and rac1 gtpases differentially regulate agonist-receptor mediated reactive oxygen species generation in platelets. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0163227. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carrizzo A, Forte M, Lembo M, Formisano L, Puca AA, Vecchione C. Rac-1 as a new therapeutic target in cerebro- and cardio-vascular diseases. Curr Drug Targets. 2014;15:1231–1246. doi: 10.2174/1389450115666141027110156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aslan JE, Tormoen GW, Loren CP, Pang J, McCarty OJ. S6k1 and mtor regulate rac1-driven platelet activation and aggregation. Blood. 2011;118:3129–3136. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-331579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xie R, Wang P, Ji X, Zhao H. Ischemic post-conditioning facilitates brain recovery after stroke by promoting akt/mtor activity in nude rats. J Neurochem. 2013;127:723–732. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Medeiros C, Frederico MJ, da Luz G, Pauli JR, Silva AS, Pinho RA, Velloso LA, Ropelle ER, De Souza CT. Exercise training reduces insulin resistance and upregulates the mtor/p70s6k pathway in cardiac muscle of diet-induced obesity rats. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226:666–674. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Snoep JD, Hovens MM, Eikenboom JC, van der Bom JG, Huisman MV. Association of laboratory-defined aspirin resistance with a higher risk of recurrent cardiovascular events: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1593–1599. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.15.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mueller MR, Salat A, Stangl P, Murabito M, Pulaki S, Boehm D, Koppensteiner R, Ergun E, Mittlboeck M, Schreiner W, Losert U, Wolner E. Variable platelet response to low-dose asa and the risk of limb deterioration in patients submitted to peripheral arterial angioplasty. Thromb Haemost. 1997;78:1003–1007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hu L, Chang L, Zhang Y, Zhai L, Zhang S, Qi Z, Yan H, Yan Y, Luo X, Zhang S, Wang Y, Kunapuli SP, Ye H, Ding Z. Platelets express activated p2y12 receptor in patients with diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2017;136:817–833. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.026995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.