Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the utility of cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) T1 mapping in early systemic sclerosis (SSc) and its association with skin score.

Methods

Twenty-four consecutive patients with early SSc referred for cardiovascular evaluation and 12 controls without SSc were evaluated. All patients underwent cine, T1 mapping, and late gadolinium enhanced (LGE) CMR imaging. T1 mapping indices were compared between SSc patients and controls (extracellular volume fraction [ECV], gadolinium partition coefficient [λ], pre-contrast T1, and post-contrast T1). The association between T1 mapping parameters and the modified Rodnan skin score (mRSS) was determined.

Results

There were no significant differences in cardiac structure/function between SSc patients and controls on cine imaging, and 8/24 (33%) SSc patients had evidence of LGE (i.e., focal myocardial fibrosis). Of the T1 mapping parameters (indices indicative of diffuse myocardial fibrosis), ECV differentiated SSc patients from controls the best, followed by λ, even when the eight SSc patients with LGE were excluded. ECV had a sensitivity and specificity of 75% and 75% for diffuse myocardial fibrosis (optimal abnormal cut-off value of >27% [area under ROC curve=0.85]). In the 16 patients without evidence of LGE, each of the 4 CMR T1 mapping parameters (ECV, λ, Pre-T1 and Post-T1) correlated with mRSS (R=0.51–0.65, P=0.007–0.043), indicating a correlation between SSc cardiac and skin fibrosis.

Conclusions

The four T1 mapping indices are significantly correlated with mRSS in patients with early SSc. Quantification of diffuse myocardial fibrosis using ECV should be considered as a marker for cardiac involvement in SSc clinical studies.

Keywords: Scleroderma, Systemic sclerosis, Cardiovascular magnetic resonance, Myocardial fibrosis, T1 mapping, Extracellular Volume Fraction, modified Rodnan skin score, Skin fibrosis

Background

At autopsy, myocardial fibrosis has been demonstrated in nearly half of SSc patients despite widely patent coronary arteries, and cardiac death is 5–15 times more common in SSc patients with myocardial fibrosis than those without(1). Currently, endomyocardial biopsy is the current gold standard for myocardial fibrosis detection in SSc, however this technique is impractical as a screening technique because it is invasive and subject to sampling error(2).

Standard cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging protocols typically include cine (series of MR images viewed in succession to assess cardiac motion) and late gadolinium enhanced (LGE) images. Because gadolinium-based contrast agents are extracellular agents, the volume of distribution of contrast is higher in areas of fibrosis relative to normal myocardium. LGE CMR capitalizes on this differential distribution of contrast to identify focal areas of macroscopic myocardial fibrosis, such as that seen in myocardial infarction (MI). LGE CMR quantification of MI size matches closely with histology(3) and has been shown to be more sensitive than single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) for identification of subendocardial MI(4). LGE CMR has also been shown to identify nonvascular distributions of myocardial fibrosis in patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathies(5) including those with SSc(6–9). However, LGE CMR is a T1-weighted imaging technique that relies on a relative increase in signal enhancement in areas of macroscopic fibrosis over a normal reference region(10). During acquisition, a parameter called the inversion time must be selected to “null” an area of normal myocardium (i.e., make the normal region black), which maximizes the signal difference between the bright fibrotic region and the dark normal region. But in the absence of a normal myocardial region, as often occurs in SSc patients, myocardium with diffuse interstitial fibrosis may be underestimated or even missed(11).

Cardiac magnetic resonance T1 mapping is a newer technique that allows quantification of diffuse myocardial fibrosis by measuring the T1 of myocardium before and after contrast. T1 (measured in milliseconds) is a measure of the time required for protons in a voxel to return to their ground state following excitation. Because gadolinium-based contrast agents have powerful T1 shortening properties, the change in T1 after contrast (Post-T1) reflects the local gadolinium contrast concentration, and hence the degree to which the extracellular space of the myocardium has been expanded by interstitial fibrosis, replacement fibrosis, necrosis, or infiltration (e.g., amyloidosis). T1 mapping has been used to quantify diffuse myocardial fibrosis in aortic stenosis(12), hypertrophic cardiomyopathy(13), systemic lupus erythematosus(14), nonischemic cardiomyopathy(15) and SSc(16–18). Several emerging T1 mapping-based methods for quantifying diffuse myocardial fibrosis include the detection of pre-contrast T1 (Pre-T1) prolongation(19), Post-T1 (PostT1) shortening(15, 19), increased myocardial gadolinium partition coefficient (λ)(20), and increased extracellular volume fraction (ECV)(12), are uniquely suited for assessing the characteristically diffuse pattern of myocardial fibrosis seen in SSc.

The modified Rodnan skin score (mRSS) is a validated, semi-quantitative scale for skin fibrosis extent and severity assessment(21). Cardiac disease in SSc has been shown to be associated with skin fibrosis(22, 23). More patients with diffuse versus limited SSc demonstrate heart disease attributable to SSc(24, 25). Moreover, incident cardiomyopathy, symptomatic pericarditis or an arrhythmia requiring treatment, developed in 15% of 953 SSc patients with diffuse skin disease during a mean follow-up of 10 years(26).

We hypothesized that SSc subjects with early disease will have more diffuse myocardial fibrosis quantified by CMR T1-mapping strategies (Pre-T1, Post-T1, λ and ECV) compared to controls without SSc-related cardiac disease, and that SSc patients with worse skin fibrosis as assessed by the mRSS will have greater diffuse myocardial fibrosis on CMR. We also sought to evaluate the accuracy of the various emerging CMR diffuse myocardial fibrosis quantification methods for the assessment of myocardial fibrosis in patients with SSc.

Methods

Study sample characteristics

The Northwestern University Institutional Review Board approved this retrospective study of SSc patients who were enrolled in a prospective registry. Participants who had been referred to a single cardiologist (S.J.S.) for evaluation of possible cardiac involvement based upon the presence of symptoms that could be attributed to cardiac disease or echocardiographic abnormalities, and who had undergone CMR imaging with Pre-T1 and Post-T1 mapping were studied. All patients provided written informed consent to permit electronic medical record, including CMR, review. Demographic and clinical data including presence of cardiac symptoms, comorbidities (arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia), smoking history, Raynaud and SSc disease duration, SSc subtype, presence of serum autoantibodies, heart rate at time of CMR were collected via chart review. Electrocardiogram (ECG), pulmonary function test (PFT) and electrocardiographic (echo) data were also collected. Control subjects had undergone negative CMR stress perfusion imaging at Northwestern Memorial Hospital for suspected coronary artery disease. Clinical records were queried to identify control patients based on the following criteria: no diagnosis of SSc or other myocardial infiltrative process, normal LV function on cine imaging, no ischemia on CMR perfusion, no scarring on LGE imaging, and no clinical cardiovascular events on > 1 year of follow up. Additionally, Pre-T1 and Post-T1 mapping must have been performed to allow ECV calculation.

Image acquisition

CMR was performed on a clinical 1.5-T scanner (MAGNETOM Avanto, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) with an 18-channel body coil. The CMR scan protocol for all patients included cine imaging, Pre-T1 mapping, Post-T1 mapping, and LGE imaging. Cine-CMR utilized a segmented retrospectively gated steady-state free-precession (SSFP) sequence. Late gadolinium enhancement images were acquired 15 – 30 minutes after Gd-CA administration (Gd-DTPA 0.2 mmol/kg) using a segmented inversion-recovery gradient echo pulse sequence with phase sensitive inversion recovery (PSIR) reconstruction. T1 mapping was performed using the classic modified look locker with inversion recovery sequence (MOLLI) as described by Messroghli(27) on a mid-ventricular short axis slice. This involved three adiabatic inversion pulses followed by 3, 3, and 5 acquisition heartbeats, respectively, and with 3 recovery heartbeats preceding the second and third inversion pulses to ensure complete T1 recovery. The MOLLI scans used single shot SSFP readout with TR/TE = 2.5/1.1 ms, FA = 35 degrees, FOV = 320 × 250 mm2, matrix = 192 × 120, slice thickness = 8 mm, BW = 1002 Hz/pixel, GRAPPA factor 2 acceleration, initial TI = 115 ms, TI increment for each subsequent inversion pulse = 80 ms.

Image analysis

Cine-CMR images were analyzed quantitatively using QMass MR 7.6 (Medis, Leiden, Netherlands) for left ventricular (LV) and right ventricular (RV) mass index, LV and RV end-diastolic volume index, LV and RV ejection fraction (EF), and LGE mass as a percentage of LV mass (LGE%).

Myocardial diffuse fibrosis was quantified by CMR using techniques that have been previously reported 1) Pre-T1, 2) Post-T1, 3) λ), and 4) ECV. Regions of interest were manually drawn on MOLLI images 1) in the LV blood pool, taking care to exclude papillary muscles, and 2) encompassing the entire myocardium, excluding areas of visible LGE and excluding 10% of the myocardial thickness on the endo- and epicardial surface to ensure exclusion of blood pool. The gadolinium partition coefficient was calculated as λ = ΔR1myocardium/ΔR1bloodpool, where R1 = 1/ T1 and ΔR1 is post-contrast – pre-contrast R1. Extracellular volume fraction was calculated as ECV = ΔR1myocardium/ΔR1bloodpool · (1 - hematocrit).

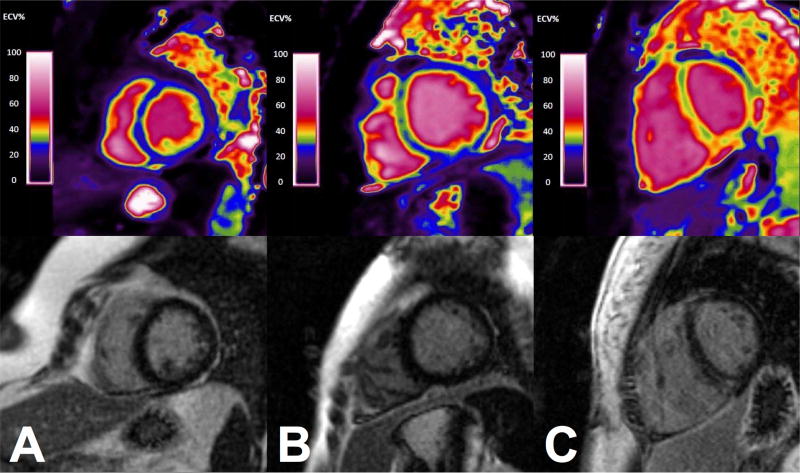

T1 and ECV maps

In selected patients, generation of ECV maps was performed to enable visualization of the spatial distribution of SSc cardiac involvement (Figure 3). T1 maps were generated by applying a novel motion correction algorithm(28), and performing pixel-wise non-linear curve fitting with a three-parameter model. The pre-contrast and post-contrast T1 maps were used to calculate ECV on a per-voxel basis to enable ECV visualization using a custom look-up table. ECV map generation was performed in Matlab (The Mathworks, Natick, MA).

Figure 3.

Extracellular volume maps (top row) and corresponding LGE images (bottom row) in A. control patient, B. an SSc patient without visible LGE, and C. an SSc patient with visible LGE.

Reproducibility

In a subset of the cohort, pre- and post-contrast MOLLI images were analyzed by two separate blinded observers (B.C.B., R.S.), and twice by a single blinded observer (B.C.B.) to assess interobserver and intraobserver reproducibility.

SSc disease severity

Two rheumatologists in the Northwestern Scleroderma Program (M.H. and J.V.) verified SSc diagnosis and type (diffuse or limited cutaneous) and performed mRSS)(29). Investigators who were responsible for analyzing CMR (including T1 mapping indices) were blinded to mRSS and all other clinical data on the SSc patients.

Echocardiography

Patients underwent comprehensive two-dimensional echocardiography with Doppler and tissue Doppler imaging according to published guidelines(30, 31)using a Philips ie33 or Sonos 7500 echocardiographic machine as previously described(32).

Statistics

Continuous data (presented as mean ± SD) were compared using unpaired, 2-tailed t-tests. P-values < 0.05 were considered significant. Pearson and Spearman (as appropriate) correlation and linear regression analyses were used to compare CMR fibrosis measurement values and echo variables to mRSS and pulmonary function test parameters. Because of a right-skewed distribution, mRSS was log-transformed for all linear regression and correlation analyses. CMR fibrosis measurement techniques were evaluated for the ability to distinguish SSc from controls using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, also known as the C-statistic(33). The C-statistic is used to assess the classification accuracy of a biomarker in a case-control study(34). Reproducibility was assessed using intraclass correlation coefficient and coefficient of variation. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata v12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Study population

The study sample consisted of 24 SSc patients (13 diffuse and 11 limited cutaneous) with early disease (mean SSc disease duration = 11 ± 10 months) and 12 healthy control participants (Table 1). The median (25th-75th percentile) mRSS was 9 (4.5, 20). A summary of symptomatology, ECG and echo abnormalities that necessitated a cardiology referral are presented in Table 1. Patients underwent CMR as part of comprehensive cardiac assessment. Heart rate at the time of CMR scan did not differ significantly between groups (control 64.7±9.1, SSc 73.0 ± 17.5 beats per minute, p=0.072).

Table 1.

Comparison of clinical characteristics in systemic sclerosis and control patients

| Characteristic | Control | Systemic sclerosis | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=12) | (N=24) | |||

| Age | 57 ± 9 | 52 ± 13 | 0.17 | |

| Women (n, %) | 5 (42%) | 20 (83%) | 0.02* | |

| Race (n, %) | ||||

| • White | 9 (75%) | 19 (79%) | >0.99* | |

| • Black | 1(8%) | 2 (8%) | >0.99* | |

| • Asian | 0 (0%) | 2 (8%) | 0.54* | |

| Ethnicity (n, % Hispanic) | 2 (17%) | 1 (4%) | 0.26* | |

| Raynaud disease duration (months) | — | 13 ± 11 | ||

| Systemic sclerosis disease duration (months)* | — | 11 ± 10 | ||

| Diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis (n, %) | — | 12 (52%) | ||

| Modified Rodnan skin score**/*** | — | 9 (4.5, 20) | ||

| Serum autoantibodies (n, %) | 18 (75%) | |||

| • Anticentromere | 6 (25%) | |||

| • Anti-RNA polymerase III | 6 (25%) | |||

| • Anti-topoisomerase I | 8 (33%) | |||

| Arterial hypertension (n, %) | 6 (50%) | 6 (25%) | 0.16* | |

| Diabetes mellitus (n, %) | 2 (17%) | 1 (4%) | 0.26* | |

| Hyperlipidemia (n, %) | 8 (67%) | 7 (29%) | 0.03 | |

| Cardiac Symptoms: | ||||

| • Fatigue | 4 (17%) | |||

| • Orthopnea | 1 (4%) | |||

| • Edema | 6 (25%) | |||

| • Chest Pain | 7 (29%) | |||

| • Shortness of breath | 14 (58%) | |||

| • Palpitations | 11 (46%) | |||

| • Dyspnea | 12 (50%) | |||

| • Lightheadedness | 1 (4%) | |||

| Current smoker (n, %) | 1 (8%) | 0 (0%) | 0.33* | |

| Brain natriuretic peptide, BNP (pg/mL)*** | — | 56.6 (31,156) | ||

| Electrocardiogram data: | ||||

| • Normal | 4 (16.7%) | |||

| • P wave abnormality | 6 (25%) | |||

| • T wave abnormality | 11 (45.8%) | |||

| • Bradycardia | 4 (16.7%) | |||

| • Tachycardia | 5 (20.8%) | |||

| • Left axis deviation | 6 (25%) | |||

| • Right-axis deviation | 2 (8.3%) | |||

| • Conduction abnormality | 1 (4.2%) | |||

| • Right bundle branch block | 5 (20.8%) | |||

| • Prior infarct | 4 (16.7%) | |||

| • Left ventricular hypertrophy | 3 (12.5%) | |||

| Echocardiography data: | ||||

| • EF (%) | 60 ± 9 | |||

| • LV mass index (g/m2) | 83.9 ± 27.2 | |||

| • LA volume index (ml/m2) | 27.0 ± 7.2 | |||

| • E/A ratio | 1.3 ± 0.4 | |||

| • e' velocity (cm/s) | 9.5 ± 3.0 | |||

| • PA systolic pressure (mmHg) | 36.8 ± 10.8 | |||

Continuous variables are reported as mean ± standard deviation unless otherwise specified.

Defined as duration between first non-Raynaud SSc symptom and cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging.

At time of CMR.

Reported as median (25th-75th percentile) because distribution right-skewed. EF= ejection fraction; LV=left ventricle; LA=left atrium; E/A= ratio or early to late (atrial) mitral inflow; e’= early diastolic relaxation velocity; PA=pulmonary artery.

We examined the correlation between echo variables (LV mass index= a measure of LV hypertrophy adjusted for body surface area) and LA volume index= a measure of left atrial size adjusted for body surface area) and CMR fibrosis indices as well as select PFT parameters (FVC and DLCO % predicted). There were no significant correlations between LV mass index and LA volume index and CMR fibrosis indices or mRSS (Supplementary Table 1). Next, we examined the correlation between CMR fibrosis indices and PFT parameters in all patients and after excluding patients with LGE (Supplementary Table 2). No significant correlations were observed.

Cine and LGE imaging

Quantitative CMR measures of LV and RV structure and function were similar between controls and SSc patients (Table 2). Late gadolinium enhancement was present in 8 out of 24 (33%) of the SSc patients (Fig. 1) and no controls. By standard cine and LGE imaging, the remaining 16 out of 24 (67%) SSc patients, and all of the controls, had normal CMR studies.

Table 2.

Comparison of cardiac structure and function in SSc and control patients

| Parameter | Control (N=12) |

Systemic sclerosis (N=24) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heart rate | |||

|

| |||

| LV mass index (g/m2) | 42.7 ± 6.2 | 43.9 ± 12.1 | 0.76 |

| LV end-diastolic volume index (ml/m2) | 75.1 ± 16.5 | 77.8 ± 23.7 | 0.72 |

| LV ejection fraction (%) | 57.5 ± 4.9 | 56.0 ± 12.1 | 0.68 |

| RV mass index (g/m2) | 16.6 ± 3.1 | 19.4 ± 5.6 | 0.12 |

| RV end-diastolic volume index (ml/m2) | 72.0 ± 18.6 | 81.5 ± 20.2 | 0.18 |

| RV ejection fraction (%) | 53.0 ± 4.4 | 48.1 ± 11.3 | 0.16 |

| Late Gadolinium Enhancement (% of LV) | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 1.6 ± 3.5 | 0.13 |

Values represent mean ± standard deviation; LV = left ventricular; RV = right ventricular

Figure 1.

Visible late gadolinium enhancement was seen in 8/24 SSc patients. A. Patient with a small area of myocardial fibrosis (LGE 2.6% of LV) in the epicardial region at the inferior right ventricular insertion point. B. Patient with a moderate area of mid-myocardial fibrosis (LGE 3.8% of LV) in the interventricular septum. C. Patient with extensive scarring (LGE 16.3% of LV) involving the inferior right ventricular insertion point, endocardial inferolateral left ventricular wall, and epicardial anterior left ventricular wall extending into the anteroseptum.

Diffuse fibrosis assessment

When SSc patients were compared to controls, significant differences were seen for Pre-T1, λ, and ECV, but not for Post T1. These differences remained significant for λ and ECV, even when the patients with visible LGE were excluded (Table 3).

Table 3.

CMR indices of diffuse myocardial fibrosis in patients with systemic sclerosis and controls.

| Controls (N = 12) |

All SSc (N = 24) |

p-value* | SSc Without LGE (N = 16) |

p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECV (%) | 24.1 ± 3.5 | 30.0 ± 4.2 | <0.001 | 29.5 ± 4.5 | 0.002 |

| Partition coefficient (λ) | 0.41 ± 0.05 | 0.47 ± 0.05 | <0.001 | 0.47 ± 0.05 | 0.003 |

| Pre-T1 (ms) | 951 ± 46 | 1005 ± 63 | 0.012 | 998 ± 61 | 0.033 |

| Post-T1 (ms) | 442 ± 27 | 433 ± 57 | 0.608 | 412 ± 44 | 0.048 |

Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation; SSc = systemic sclerosis; LGE = late gadolinium enhancement; ECV = extracellular volume fraction; λ = gadolinium partition coefficient; Pre-T1 = pre-contrast T1; Post=T1 = post-contrast T1.

p-values are for comparison to controls.

Scatter plots were used to assess the correlation between mRSS and diffuse myocardial fibrosis quantified by CMR using Pre-T1, Post-T1, λ, and ECV in patients without evidence of LGE (n=16; Figure 2). Significant correlation with log mRSS was seen for all indices.

Figure 2.

Correlation between cardiac magnetic resonance indices of diffuse myocardial fibrosis and systemic sclerosis disease severity quantified by the modified Rodnan skin score (mRSS).

C-statistics were used to compare the diagnostic performance of the different CMR measures of fibrosis in differentiating the hearts of SSc and control subjects. ECV had the highest C-statistic, followed by λ, Pre-T1, and finally Post-T1. The optimal cutoffs and sensitivity/specificity for each T1 mapping parameter are listed in Table 4. ECV > 27% had the best test characteristics for differentiating SSc from controls.

Table 4.

Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, optimal cutoff values, sensitivity, and specificity for the differentiation of systemic sclerosis from controls using cardiac magnetic resonance indices of diffuse myocardial fibrosis.

| Diffuse fibrosis imaging parameter |

C-statistic (95% CI) |

Optimal cutoff value |

Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extracellular volume fraction | 0.85 (0.73–0.98) | 27% | 75% | 75% |

| Partition coefficient (λ) | 0.81 (0.67–0.96) | 0.44 | 71% | 75% |

| Pre-T1 | 0.73 (0.55–0.90) | 977 ms | 67% | 67% |

| Post-T1 | 0.60 (0.41–0.79) | 429 ms | 54% | 75% |

ECV mapping enabled visual assessment of myocardial fibrosis that was sometimes disparate from LGE imaging (Fig. 3).

Reproducibility

In 13 CMR studies, intraobserver and interobserver reproducibility were high and coefficient of variation was < 2% for all T1 mapping parameters of diffuse myocardial fibrosis (Table 5).

Table 5.

Reproducibility of Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging T1 Mapping Parameters

| T1 mapping parameter |

Interobserver variability | Intraobserver variability | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICC (95% CI) | Coefficient of variation |

ICC (95% CI) | Coefficient of variation |

|

| Pre-T1 | 0.88 (0.79–0.97) | 0.8% | 0.88 (0.80–0.97) | 1.0% |

| Post-T1 | 0.99 (0.97–0.99) | 0.5% | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) | 0.6% |

| λ | 0.96 (0.94–0.99) | 1.2% | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) | 1.1% |

| ECV | 0.98 (0.96–0.99) | 1.3% | 0.98 (0.97–0.99) | 1.1% |

ICC = intraclass correlation; ECV = extracellular volume fraction; λ = partition coefficient; Pre-T1 = pre-contrast T1; Post-T1 = post-contrast T1

Discussion

In a detailed CMR study of SSc patients and controls that included cine, LGE and T1 mapping strategies (Pre-T1, Post-T1, λ and ECV), we found that three of the four CMR T1 mapping techniques (not PostT1) demonstrated significant differences in diffuse myocardial fibrosis between SSc patients and controls even in the setting of normal cine findings. In the 16 SSc patients lacking LGE, we found that all four CMR T1 mapping techniques demonstrated significant differences in diffuse myocardial fibrosis between SSc patients and controls. Of the T1 mapping parameters, ECV demonstrated the best test characteristics for differentiating the fibrotic hearts of SSc patients from control patients. Finally, mRSS correlated highly with diffuse myocardial fibrosis suggesting that extent of skin and myocardial fibrosis is related.

CMR LGE imaging enables accurate visualization of the presence and location of focal myocardial fibrosis due to myocardial infarction(35) and assessment of myocardial viability(36). The LGE technique maximizes the signal difference between focal fibrosis and normal tissue by “nulling” (making black) normal myocardium(10). Following injection, Gd-CA accumulates within infarcted myocardium to a greater degree than in normal myocardium(37) because of the larger extracellular volume of distribution to which these extracellular agents can gain access. Gadolinium shortens T1 relaxation time, so areas with increased Gd-CA accumulation will have a shorter T1 and appear bright on T1-weighted LGE images. In our study, only 33% (8/24) of SSc patients exhibited visible LGE. Similar to our results, Barison et al. reported that 23% (7/30) of SSc patients demonstrated LGE(18). In other studies LGE has been reported in 14% to 66% of patients with SSc,(6–9, 38) usually manifesting as a linear mid-wall or a patchy nodular pattern that does not follow a coronary distribution. The wide range of prevalence may be due to differences in SSc disease severity and duration between patient populations.

LGE imaging is not likely the optimal technique for SSc myocardial fibrosis assessment. Vascular lesions in SSc result in generalized microcirculatory impairment. Repeated bouts of ischemia lead to diffuse fibrosis of the myocardium(39). On autopsy, the majority of myocardial fibrosis in SSc patients is evident only on microscopic examination.(1) This type of diffuse myocardial fibrosis with a homogeneous distribution throughout the myocardium leads to more modest increases in ECV than dense scar from myocardial infarction. The effect may be that the entire myocardium will be nulled on LGE imaging, despite increased fibrosis content.

We assessed Pre-T1 and found it provides a fair assessment of diffuse myocardial fibrosis in SSc. This technique may be useful in patients with contraindications to Gd-CA, such as contrast allergy or severely impaired renal function. However, Pre-T1 had the lowest reproducibility of all the diffuse myocardial fibrosis measurement techniques, likely because lack of contrast often made contouring the myocardium difficult.

Post-T1 did not perform as well as Pre-T1, λ and ECV. Post-T1 is affected by factors other than myocardial fibrosis content: Gd-CA dose, timing of T1 mapping relative to contrast injection, and renal clearance. Prior studies measured post-contrast T1 10.7 ± 2.7 minutes(11), 15 minutes(15), 5, 10 and 15(18) minutes after a single bolus injection of Gd-CA. A prior study in SSc patients with no cardiovascular disease also found significant differences from controls in Pre-T1, λ, and ECV, but no difference in Post-T1(16). Because patients in our study underwent routine clinical scan rather than dedicated research scans, the timing of post-contrast T1 mapping was likely not as tightly regulated as in the previously published studies.

Inclusion of λ to measure the cardiac fibrosis burden addresses many of the shortcomings of Post-T1. In an equilibrium state, alterations in dose, timing, and clearance of gadolinium should affect the extracellular concentration of Gd-CA in the blood and myocardium equally. Because the change in R1 following Gd-CA injection is directly proportional to Gd-CA concentration, λ reflects the concentration of Gd-CA in the myocardium relative to the blood. We found that λ improved the assessment of diffuse myocardial fibrosis in SSc compared to Post-T1. One limitation of λ is that variations in hematocrit (between different patients and even within the same patient on serial scans) can affect λ values independent of diffuse myocardial fibrosis.

Hematocrit is taken into account in ECV calculations along with variations in Gd-CA dose, timing, and renal clearance. Furthermore, ECV has been shown to correlate with picrosirius red fibrosis quantification on histologic analysis of surgical cardiac biopsies in patients with aortic stenosis and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy(12). In patients undergoing cardiac transplantation, regional ECV correlated closely with histological collagen volume fraction(40). Furthermore, normal appearing myocardium has been shown to have a higher ECV in older patients and patients with myocardial infarction and impaired EF, consistent with diffuse fibrosis associated with age and changes in myocardium remote from an infarction(41). Our ROC analysis that identified optimal cutoffs for each diffuse myocardial fibrosis measurement parameter demonstrated that ECV had the highest sensitivity and specificity for myocardial fibrosis detection in SSc patients compared to control subjects. Because T1 mapping is not typically performed with full volumetric coverage (i.e., not performed over the entire left ventricular myocardium but rather in a single short-axis slice), we excluded regions of visible LGE from ECV measurements that may account for our findings.

Myocardial fibrosis is a common complication of SSc - approximately half of SSc patients have evidence of myocardial fibrosis despite normal epicardial coronary arteries(1). SSc patients with severe myocardial fibrosis more commonly suffer congestive heart failure, angina pectoris, ventricular arrhythmias, conduction abnormalities, cardiac death(1), and overall mortality(42). The pathogenesis of diffuse myocardial fibrosis in SSc is thought to involve early endothelial cell dysfunction and vascular damage, myopericardial inflammation and fibrosis(43). Measurement of ECV may enable noninvasive quantification of myocardial involvement in patients with SSc. Increased ECV has been shown to predict mortality and other subsequent adverse cardiac events in patients referred for CMR(44). The potential for ECV to predict events in SSc is also supported by the correlation of ECV to the mRSS, an established predictor of poor prognosis in SSc(45).

We found a positive correlation between mRSS and all four T1 mapping parameters suggesting that CMR with T1 mapping may be a useful method for assessing cardiac fibrosis in patients with SSc.

There were study limitations. The SSc patients were referred for cardiovascular evaluation and may have had a higher prevalence of, or more severe, cardiac involvement. Endomyocardial biopsy was not clinically indicated, so we cannot correlate CMR T1 mapping indices with histologic presence or extent of myocardial fibrosis. Furthermore, MOLLI was only performed on a single mid-short axis slice. The poor performance of Post-T1 was likely due to differences in Gd-CA dose and timing between our study and previously published studies evaluating Post-T1. However, incorporation of T1 mapping into clinical CMR scans would likely encounter similar difficulties. This highlights the importance of more robust techniques such as partition coefficient and ECV. This study is also limited by the small sample size, retrospective design, and lack of matching between SSc and control patients. However, our results demonstrate the feasibility of quantifiable CMR-derived imaging biomarkers to detect early stage-interstitial myocardial fibrosis. CMR has the potential to identify identification of higher risk SSc patients to permit earlier intervention and potentially improved outcomes.

Conclusions

The main findings of this study are: (1) diffuse myocardial fibrosis measured by CMR is higher in subjects with SSc compared to controls, despite similar appearance on cine and LGE imaging; (2) in SSc patients, diffuse fibrosis measured by CMR correlates with mRSS; and (3) ECV is the most accurate T1 mapping method for quantification of diffuse myocardial fibrosis by CMR. Future studies will be needed to define the utility of CMR T1 mapping for early detection of cardiac involvement or as a surrogate marker of disease severity in patients with SSc.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

National Institutes of Health NIAMS AR059763 and L30 AR054311 (MH), NIAMS P60 AR064464 (JL); Scleroderma Research Foundation (MH) provided funding for the study but played no role in the analyses.

List Of abbreviations

- CMR

cardiovascular magnetic resonance

- ECV

extracellular volume fraction

- Gd-CA

gadolinium based contrast agent

- ICC

intraclass correlation

- LGE

late gadolinium enhanced

- LGE%

LGE mass as a percent of left ventricular mass

- MOLLI

modified look locker with inversion recovery sequence

- mRSS

modified Rodnan skin score

- λ

gadolinium partition coefficient

- Post-T1

post-contrast T1

- Pre-T1

pre-contrast T1

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

- SSc

systemic sclerosis;

Footnotes

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Northwestern Institutional Review Board approved the study and all subjects provided informed consent. Scleroderma subjects were enrolled under the Northwestern Scleroderma Program Patient Registry (STU00002669) and control subjects were enrolled under the Diffuse Fibrosis by cMRI Without Cardiovascular Disease project (STU00067593).

Consent for publication

All authors consent to the publication of the manuscript.

Availability of data and material

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflict of interest

DL (research grant – Abbott Laboratories; advising, consulting –Gilead Sciences, Inc); MH (consulting – Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Inc, Sanofi Aventis Pharmaceuticals); JV (advising, consulting -Amira Pharmaceuticals); JCC (advising, consulting - Astellas Pharma, Inc., Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Lantheus Medical Imaging, Inc.)

RS, MMS, AA, BCB, AT, KK, JL, MC, KA and SJS declare no competing interests

Authors' contributions

DCL, MH and SJS conceived the study; KA, MC, AH and AT obtained NU Institutional Review Board approval, recruited participants, performed chart review for data retrieval and obtained CMR images for quantification; DCL, MH and SJS wrote and edited the manuscript; MH and JV evaluated patients with SSc; BCB quantified CMR; DCL, MMS, RS, AA, JCC developed and refined CMR protocol and analyzed CMR data; SJS, JL and KK performed statistical analyses. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Bulkley BH, Ridolfi RL, Salyer WR, Hutchins GM. Myocardial lesions of progressive systemic sclerosis. A cause of cardiac dysfunction. Circulation. 1976;53(3):483–90. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.53.3.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooper LT, Baughman KL, Feldman AM, Frustaci A, Jessup M, Kuhl U, et al. The role of endomyocardial biopsy in the management of cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and the European Society of Cardiology. Circulation. 2007;116(19):2216–33. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.186093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim RJ, Fieno DS, Parrish TB, Harris K, Chen EL, Simonetti O, et al. Relationship of MRI delayed contrast enhancement to irreversible injury, infarct age, and contractile function. Circulation. 1999;100(19):1992–2002. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.19.1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wagner A, Mahrholdt H, Holly TA, Elliott MD, Regenfus M, Parker M, et al. Contrast-enhanced MRI and routine single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) perfusion imaging for detection of subendocardial myocardial infarcts: an imaging study. Lancet. 2003;361(9355):374–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12389-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCrohon JA, Moon JC, Prasad SK, McKenna WJ, Lorenz CH, Coats AJ, et al. Differentiation of heart failure related to dilated cardiomyopathy and coronary artery disease using gadolinium-enhanced cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Circulation. 2003;108(1):54–9. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000078641.19365.4C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tzelepis GE, Kelekis NL, Plastiras SC, Mitseas P, Economopoulos N, Kampolis C, et al. Pattern and distribution of myocardial fibrosis in systemic sclerosis: a delayed enhanced magnetic resonance imaging study. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2007;56(11):3827–36. doi: 10.1002/art.22971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Cesare E, Battisti S, DiSibio A, Cipriani P, Giacomelli R, Liakouli V, et al. Early assessment of sub-clinical cardiac involvement in systemic sclerosis (SSc) using delayed enhancement cardiac magnetic resonance (CE-MRI) European journal of radiology. 2013;82(6):e268–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2013.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hachulla AL, Launay D, Gaxotte V, de Groote P, Lamblin N, Devos P, et al. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in systemic sclerosis: a cross-sectional observational study of 52 patients. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2009;68(12):1878–84. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.095836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dimitroulas T, Mavrogeni S, Kitas GD. Imaging modalities for the diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension in systemic sclerosis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2012;8(4):203–13. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simonetti OP, Kim RJ, Fieno DS, Hillenbrand HB, Wu E, Bundy JM, et al. An improved MR imaging technique for the visualization of myocardial infarction. Radiology. 2001;218(1):215–23. doi: 10.1148/radiology.218.1.r01ja50215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sibley CT, Noureldin RA, Gai N, Nacif MS, Liu S, Turkbey EB, et al. T1 Mapping in cardiomyopathy at cardiac MR: comparison with endomyocardial biopsy. Radiology. 2012;265(3):724–32. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12112721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flett AS, Hayward MP, Ashworth MT, Hansen MS, Taylor AM, Elliott PM, et al. Equilibrium contrast cardiovascular magnetic resonance for the measurement of diffuse myocardial fibrosis: preliminary validation in humans. Circulation. 2010;122(2):138–44. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.930636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fontana M, White SK, Banypersad SM, Sado DM, Maestrini V, Flett AS, et al. Comparison of T1 mapping techniques for ECV quantification. Histological validation and reproducibility of ShMOLLI versus multibreath-hold T1 quantification equilibrium contrast CMR. Journal of cardiovascular magnetic resonance: official journal of the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. 2012;14:88. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-14-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Puntmann VO, D'Cruz D, Smith Z, Pastor A, Choong P, Voigt T, et al. Native myocardial T1 mapping by cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in subclinical cardiomyopathy in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Circulation Cardiovascular imaging. 2013;6(2):295–301. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.112.000151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iles L, Pfluger H, Phrommintikul A, Cherayath J, Aksit P, Gupta SN, et al. Evaluation of diffuse myocardial fibrosis in heart failure with cardiac magnetic resonance contrast-enhanced T1 mapping. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(19):1574–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ntusi NA, Piechnik SK, Francis JM, Ferreira VM, Rai AB, Matthews PM, et al. Subclinical myocardial inflammation and diffuse fibrosis are common in systemic sclerosis--a clinical study using myocardial T1-mapping and extracellular volume quantification. Journal of cardiovascular magnetic resonance : official journal of the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. 2014;16:21. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-16-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thuny F, Lovric D, Schnell F, Bergerot C, Ernande L, Cottin V, et al. Quantification of myocardial extracellular volume fraction with cardiac MR imaging for early detection of left ventricle involvement in systemic sclerosis. Radiology. 2014;271(2):373–80. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13131280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barison A, Gargani L, De Marchi D, Aquaro GD, Guiducci S, Picano E, et al. Early myocardial and skeletal muscle interstitial remodelling in systemic sclerosis: insights from extracellular volume quantification using cardiovascular magnetic resonance. European heart journal cardiovascular Imaging. 2015;16(1):74–80. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jeu167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bull S, White SK, Piechnik SK, Flett AS, Ferreira VM, Loudon M, et al. Human non-contrast T1 values and correlation with histology in diffuse fibrosis. Heart. 2013 doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-303052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu S, Han J, Nacif MS, Jones J, Kawel N, Kellman P, et al. Diffuse myocardial fibrosis evaluation using cardiac magnetic resonance T1 mapping: sample size considerations for clinical trials. Journal of cardiovascular magnetic resonance : official journal of the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. 2012;14:90. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-14-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Foocharoen C, Thinkhamrop B, Mahakkanukrauh A, Suwannaroj S, Netwijitpan S, Sripavatakul K, et al. Inter- and Intra-Observer Reliability of Modified Rodnan Skin Score Assessment in Thai Systemic Sclerosis Patients: A Validation for Multicenter Scleroderma Cohort Study. J Med Assoc Thai. 2015;98(11):1082–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foocharoen C, Pussadhamma B, Mahakkanukrauh A, Suwannaroj S, Nanagara R. Asymptomatic cardiac involvement in Thai systemic sclerosis: prevalence and clinical correlations with non-cardiac manifestations (preliminary report) Rheumatology (Oxford) 2015;54(9):1616–21. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kev096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okutucu S, Karakulak UN, Aksoy H, Sabanoglu C, Hekimsoy V, Sahiner L, et al. Prolonged Tp-e interval and Tp-e/QT correlates well with modified Rodnan skin severity score in patients with systemic sclerosis. Cardiology journal. 2016;23(3):242–9. doi: 10.5603/CJ.a2016.0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferri C, Valentini G, Cozzi F, Sebastiani M, Michelassi C, La Montagna G, et al. Systemic sclerosis: demographic, clinical, and serologic features and survival in 1,012 Italian patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2002;81(2):139–53. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200203000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allanore Y, Meune C, Vonk MC, Airo P, Hachulla E, Caramaschi P, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with left ventricular dysfunction in the EULAR Scleroderma Trial and Research group (EUSTAR) database of patients with systemic sclerosis. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2010;69(1):218–21. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.103382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steen VD, Medsger TA., Jr Severe organ involvement in systemic sclerosis with diffuse scleroderma. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2000;43(11):2437–44. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200011)43:11<2437::AID-ANR10>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Messroghli DR, Radjenovic A, Kozerke S, Higgins DM, Sivananthan MU, Ridgway JP. Modified Look-Locker inversion recovery (MOLLI) for high-resolution T1 mapping of the heart. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 2004;52(1):141–6. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xue H, Shah S, Greiser A, Guetter C, Littmann A, Jolly MP, et al. Motion correction for myocardial T1 mapping using image registration with synthetic image estimation. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 2012;67(6):1644–55. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.LeRoy EC, Black C, Fleischmajer R, Jablonska S, Krieg T, Medsger TA, Jr, et al. Scleroderma (systemic sclerosis): classification, subsets and pathogenesis. The Journal of rheumatology. 1988;15(2):202–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Pellikka PA, et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18(12):1440–63. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nagueh SF, Appleton CP, Gillebert TC, Marino PN, Oh JK, Smiseth OA, et al. Recommendations for the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function by echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22(2):107–33. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2008.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hinchcliff M, Desai CS, Varga J, Shah SJ. Prevalence, prognosis, and factors associated with left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2012;30(2 Suppl 71):S30–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eng J. ROC analysis: web-based calculator for ROC curves. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University; [updated 2006 May 17; cited March 28, 2013]. Available from: http://www.jrocfit.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 34.Janes H, Pepe M. The optimal ratio of cases to controls for estimating the classification accuracy of a biomarker. Biostatistics. 2006;7(3):456–68. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxj018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu E, Judd RM, Vargas JD, Klocke FJ, Bonow RO, Kim RJ. Visualisation of presence, location, and transmural extent of healed Q-wave and non-Q-wave myocardial infarction. Lancet. 2001;357(9249):21–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03567-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim RJ, Wu E, Rafael A, Chen EL, Parker MA, Simonetti O, et al. The use of contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging to identify reversible myocardial dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(20):1445–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011163432003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rehwald WG, Fieno DS, Chen EL, Kim RJ, Judd RM. Myocardial magnetic resonance imaging contrast agent concentrations after reversible and irreversible ischemic injury. Circulation. 2002;105(2):224–9. doi: 10.1161/hc0202.102016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodriguez-Reyna TS, Morelos-Guzman M, Hernandez-Reyes P, Montero-Duarte K, Martinez-Reyes C, Reyes-Utrera C, et al. Assessment of myocardial fibrosis and microvascular damage in systemic sclerosis by magnetic resonance imaging and coronary angiotomography. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2015;54(4):647–54. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keu350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meune C, Vignaux O, Kahan A, Allanore Y. Heart involvement in systemic sclerosis: evolving concept and diagnostic methodologies. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2010;103(1):46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller CA, Naish JH, Bishop P, Coutts G, Clark D, Zhao S, et al. Comprehensive validation of cardiovascular magnetic resonance techniques for the assessment of myocardial extracellular volume. Circulation Cardiovascular imaging. 2013;6(3):373–83. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.112.000192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ugander M, Oki AJ, Hsu LY, Kellman P, Greiser A, Aletras AH, et al. Extracellular volume imaging by magnetic resonance imaging provides insights into overt and sub-clinical myocardial pathology. Eur Heart J. 2012 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ioannidis JP, Vlachoyiannopoulos PG, Haidich AB, Medsger TA, Jr, Lucas M, Michet CJ, et al. Mortality in systemic sclerosis: an international meta-analysis of individual patient data. The American journal of medicine. 2005;118(1):2–10. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mavrogeni SI, Bratis K, Karabela G, Spiliotis G, Wijk K, Hautemann D, et al. Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Imaging clarifies cardiac pathophysiology in early, asymptomatic diffuse systemic sclerosis. Inflammation & allergy drug targets. 2015;14(1):29–36. doi: 10.2174/1871528114666150916112551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wong TC, Piehler K, Meier CG, Testa SM, Klock AM, Aneizi AA, et al. Association between extracellular matrix expansion quantified by cardiovascular magnetic resonance and short-term mortality. Circulation. 2012;126(10):1206–16. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.089409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clements PJ, Lachenbruch PA, Ng SC, Simmons M, Sterz M, Furst DE. Skin score. A semiquantitative measure of cutaneous involvement that improves prediction of prognosis in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis and rheumatism. 1990;33(8):1256–63. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.