Abstract

Importance

While poorer populations have more eye problems, it is not known if they face greater difficulty obtaining eye care appointments.

Objective

To compare rates of obtaining eye care appointments and appointment wait times for those with Medicaid and private insurance.

Design

In this prospective observational study, researchers telephoned a randomly selected sample of vision care providers in Michigan and Maryland stratified by neighborhood (urban vs. rural) and provider type (ophthalmologist vs. optometrist) to request the first available appointment. Appointments were sought for an adult needing a diabetic eye exam and a child requesting a routine eye exam for a failed vision screening. Researchers called each practice twice, approximately 2–7 days apart, once requesting an appointment for a patient with Medicaid, and the other for a patient with BlueCross BlueShield (BCBS), and asked if 1) the insurance was accepted, and if so, 2) when the earliest available appointment was.

Setting

Eye clinics throughout Maryland and Michigan.

Participants

Random sample of 330 ophthalmology and optometry practices.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Rate of successfully made appointments and mean wait time for the first available appointment.

Results

A total of 330 eye care providers were contacted. The sample consisted of ophthalmologists (50%) and optometrists (50%) located in Maryland (53%) and Michigan (47%). The rates of successfully obtaining appointments among callers said to have Medicaid and BCBS were 62% [56%,67%] and 79% [75%,84%] (p<0.001), respectively, for adults, and 45% [40%,51%] and 63% [57%,68%] (p<0.001), respectively, for children. Mean wait time did not vary significantly between BCBS and Medicaid for both adult and child. Factors associated with decreased odds of obtaining an appointment for adults and children included Medicaid insurance, appointment with an ophthalmologist and practice location in Maryland.

Conclusions and Relevance

Callers were less successful in trying to obtain eye care appointments with Medicaid than with BCBS, suggesting a disparity in access to eye care based on insurance status, though confounding factors may have also contributed to this finding. Improving access to eye care professionals for those with Medicaid may improve health outcomes and decrease healthcare spending in the long term.

Introduction

Poor eye health negatively impacts quality of life, school and work performance.1 However, vision care is not part of every Medicaid plan since coverage varies by state. Only 9 of the 50 states in the Unites States cover annual routine eye exams for those with Medicaid.2 Most states provide routine eye exams less frequently (once every 2–5 years) or only cover eye exams for diagnosed eye conditions or injuries.2 In Maryland and Michigan, a routine eye exam is covered once every 24 months by Medicaid2 whereas BlueCross BlueShild (BCBS) will pay for a routine exam annually3,4

Low-income and racial/ethnic minority populations access health services less frequently than higher-income and racial/ethnic majority populations. In a cross-sectional study based on data from the 2013 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) on adults with diabetes in the US, minority groups were found to have lower rates of HbA1c tests, eye exams, and flu vaccinations compared to whites.5 Similarly, an analysis of MEPS data from 2007 revealed that while 76.4% of those with private insurance had received eye care in the past year, only 17% of those with public insurance did so.6 Prior research found that implementation of adult vision insurance coverage is associated with a 10% increase in the proportion of Medicaid beneficiaries with appropriately corrected refractive error.7 However, only 20% of federally-funded community health centers, which are mandated in underserved communities, have an onsite eye care professional.8 Furthermore, only 28% of community health centers reported performing dilated eye exams for patients with diabetes. Barriers to providing eye care to poor populations include an inequitable distribution of eye care providers,9 equipment costs, and perceived financial disincentives (i.e. inadequate reimbursement).10 Medicaid patients also face difficulties obtaining appointments with doctors in other fields of medicine,10, 11 and may also be less able to obtain needed eye care appointments compared to other patients.

Although studies have shown that patients with Medicaid receive less eye care compared to those with private insurance, there are limited data on the causes of this discrepancy. The objective of this study was to determine if it is more difficult for patients with Medicaid to obtain eye care appointments. Understanding the degree of difficulty in making eye care appointments and wait times for Medicaid patients can guide policy makers seeking to improve eye care and health in the United States.

Methods

This was a prospective, multi-center study conducted from January 2017 to July 2017. This study conformed to the standards set forth by the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Johns Hopkins Medicine and University of Michigan Institutional Review Boards.

Study procedures

The list of ophthalmologists and optometrists in the state of Maryland was obtained from the state Department of Health website.12 For Michigan, this information was obtained from websites for BlueCross BlueShield (BCBS)13 and the Michigan Medicaid Health Plan14–25 The providers were divided by state (Maryland or Michigan), neighborhood type (urban or rural), and practice type (ophthalmologist or optometrists) into 8 groups: 1) Maryland urban ophthalmologists, 2) Maryland rural ophthalmologists, 3) Maryland urban optometrists, 4) Maryland rural optometrists, 5) Michigan urban ophthalmologists, 6) Michigan rural ophthalmologists, 7) Michigan urban optometrists, 8) Michigan rural optometrists. The designation of urban or rural county was based on a population threshold determined by the respective State Department. eTable 1 lists further details about the characteristics of counties that were included.26, 27

From these groups, a random sample of providers was selected using a random number generator in Excel (Microsoft Office, Version 2013). The required sample size was estimated as 252 providers using an ANOVA power analysis (G*Power 3.1.9.2, Universitat Kiel, Germany), with effect size=0.2, α=0.05, power=0.8. Thus, we aimed to select 35 providers from each group for a total of 280 providers. However, there were not enough providers in rural Maryland, so more providers were selected from urban Maryland to attain the target sample size.

Similar studies in primary care,28 orthopedics,29 endocrinology,30 and psychiatry31 have demonstrated significant differences in patient access by insurance type. While we have shown similar findings using administrative and claims data,32 we sought to confirm these findings through a more direct means. Using a similar methodology to prior studies in other fields of medicine,28–31 a trained researcher contacted each office to determine ease of access for patients with different insurance types.

Trained researchers made phone calls to each selected provider a total of two times, seeking to obtain an appointment for him/herself and his/her child following a standard script (eMethods 1) and having either Medicaid or BCBS insurance. During the phone call, researchers utilized a standardized online survey (Qualtrics Survey Software, Provo, UT, Qualtrics, LLC) (eMethods 2) to record responses to scripted questions. We collected data including: sex of provider; office location and phone number; number of attempts to reach the provider’s office; date of appointment (if successful); reason for inability to offer an appointment (if unsuccessful); and if provided an appointment with another provider in the practice, the reason for this. Any appointment made was cancelled within 2 business days. An attempt to reach each provider was made up to 3 times during regular business hours of 9AM–5PM on Monday–Friday. If the provider was unreachable after 3 attempts, no further attempts were made to contact the office and a substitute practice was randomly selected using the method described above. Data about the counties where practices were located, including the proportion of the population that identified as a racial/ethnic minority and median household income were obtained from the US Census Bureau.33 All practitioners who were contacted were eligible members of the Medicaid and BCBS insurance panels.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using Stata (Release 15, College Station, TX, StataCorp). The rate of successful appointments and the wait time for the appointment were used as markers of eye care accessibility. Chi-square analysis was performed for the rate of appointments successfully made by insurance type. Student’s t-test were used to investigate differences in appointment wait times based on insurance status (Medicaid vs. BCBS), provider type (ophthalmologist vs optometrist), state (Maryland vs. Michigan), neighborhood type (urban vs rural), and patient age (adult vs child). Multivariable logistic regression was performed to model the relationship between insurance type and the odds of obtaining an appointment, while adjusting for provider and practice characteristics. The following provider and practice characteristics were entered into the model: provider type (ophthalmologist vs optometrist); sex of provider; state; neighborhood type (urban vs rural); and for the county where practices were located, the median household income and the proportion of the population identifying as minority race/ethnicity.

Results

A total of 603 calls were made to 330 unique eye care providers, consisting of ophthalmologists (50%) and optometrists (50%) located in Maryland (53%) and Michigan (47%) (Table 1). The sampled providers were concentrated in specific locations throughout the state. In Maryland, 60% of the contacted providers were in these 5 counties: Montgomery (18%), Baltimore City (16%), Baltimore (14%), Anne Arundel (6%), and Howard (6%). In Michigan, the top 6 counties were Wayne (16%), Oakland (13%), Macomb (6%), Lapeer (4%), Washtenaw (3%), and Ingham (3%), comprising 45% of the providers called in the study. eTable 1 provides additional information on counties in MD and MI. Of the 603 providers, 452 (75%) were reachable at first attempt, 53 (9%) at second attempt, 13 (2%) at third attempt, and 21 (3%) were not reachable after 3 attempts; an additional 64 (11%) providers were not reachable because the listed phone number was incorrect and an alternative phone number could not be located.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Eye Care Practices Contacted

| Medicaid, n (%) | BCBS, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Maryland | 164 (54) | 158 (53) |

| Michigan | 140 (46) | 141 (47) |

| Urban | 211 (69) | 202 (68) |

| Rural | 93 (31) | 97 (32) |

| Ophthalmologist | 154 (51) | 149 (50) |

| Optometrist | 150 (49) | 150 (50) |

| Total | 304 | 299 |

Insurance Type

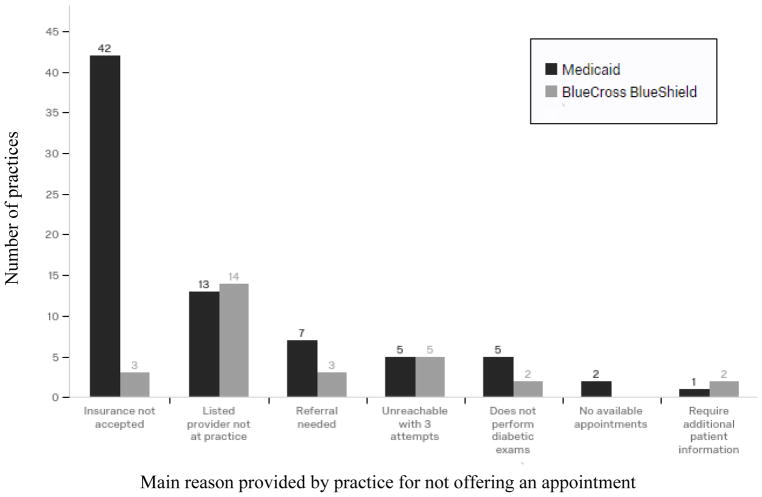

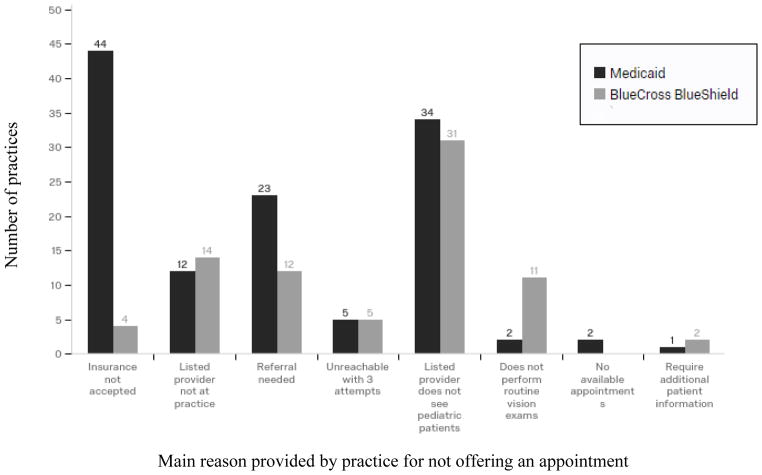

Of 304 Medicaid patients, 117 (38%) adults and 166 (55%) children were not offered appointments. Of 299 BCBS patients, 62 (21%) adults and 112 (37%) children were not offered appointments. Reasons for not providing appointments are shown in Figure 1 and 2.

Figure 1.

Reason practices did not offer an appointment for Adults

Figure 2.

Reason practices did not offer an appointment for Children

The rates of successfully obtaining appointments for Medicaid and BCBS insurance were 62% [56%, 67%] and 79% [75%, 84%] (p<0.001), respectively, for adults, and 45% [40%, 51%] and 63% [57%, 68%] (p<0.001), respectively, for children. For adults, the mean wait time until the appointment date was 16 [13, 19] (SD=21) and 15 [13, 18] (SD=21) days for Medicaid and BCBS patients, respectively; for children, the mean wait time was 14 [11, 17] (SD=18) and 13 [10, 16] (SD=18) days for Medicaid and BCBS patients, respectively (p>0.05 for both) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Success in Obtaining Eye Care Appointments by Patient, Provider Characteristics, Neighborhood Type, and State

| Adult | Child | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medicaid vs. BCBS | ||||

| Appointment Given | Medicaid (n=304) | BCBS (n=299) | Medicaid (n=304) | BCBS (n=299) |

| % yes [95% CI] | 62 [56, 67] | 79 [75, 84] | 45 [40, 51] | 63 [57, 68] |

| Δ% | 17 | 18 | ||

| P-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Mean Wait Times [95% CI], in days | 16 [13, 19] | 15 [13, 18] | 14 [11, 17] | 13 [10, 16] |

| P-value | 0.66 | 0.64 | ||

| Ophthalmologist vs. Optometrist | ||||

| Appointment Given | Ophthalmologist (n=303) | Optometrist (n=300) | Ophthalmologist (n=303) | Optometrist (n=300) |

| % yes [95% CI] | 64 [59, 70] | 76 [72, 81] | 32 [27, 38] | 76 [71, 81] |

| Δ% | 12 | 44 | ||

| P-value | 0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Mean Wait Times [95% CI], in days | 24 [20,27] | 9 [7, 11] | 23 [18, 27] | 10 [8, 11] |

| P-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Urban vs. Rural | ||||

| Appointment Given | Urban (n=413) | Rural (n=190) | Urban (n=413) | Rural (n=190) |

| % yes [95% CI] | 66 [62, 71] | 79 [73, 85] | 49 [44, 53] | 65 [58, 72] |

| Δ% | 13 | 16 | ||

| P-value | 0.002 | <0.01 | ||

| Mean Wait Times [95% CI], in days | 15 [12, 17] | 17 [14, 21] | 12 [10, 15] | 15 [12, 19] |

| P-value | 0.28 | 0.17 | ||

| Maryland vs. Michigan | ||||

| Appointment Given | Maryland (n=322) | Michigan (n=281) | Maryland (n=322) Michigan (n=281) | |

| % yes [95% CI] | 62 [57, 67] | 80 [75, 84] | 46 [40, 51] | 63 [58, 69] |

| Δ% | 18 | 17 | ||

| P-value | < 0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Mean Wait Times [95% CI], in days | 12 [10, 14] | 19 [16, 23] | 11 [9, 13] | 16 [13, 19] |

| P-value | <0.001 | 0.01 | ||

Provider Type

Overall, not accounting for insurance type, the rates of successfully obtaining appointments were 64% [59, 70] with ophthalmologists and 76% [72, 81] with optometrists (p=0.001) for adult patients. Among children, 32% [27, 38] successfully obtained appointments with ophthalmologists and 76% [71, 81] with optometrists (p<0.001).. The mean wait times for adults were 24 [20, 27] (SD=26) and 9 [7, 11] (SD=13) days (p<0.001) with ophthalmologists and optometrists, respectively. For children, mean wait times were and 23 [18,27] (SD=24) and 10 [8,11] (SD=13) days (p<0.001) with ophthalmologists and optometrists, respectively (Table 2).

Neighborhood Type

The rates of successfully obtaining appointments in urban and rural practices were 66% [62, 71] and 79% [73, 85] (p=0.002), respectively, for adults and 49% [44, 53] and 65% [58, 72] (p<0.001), respectively, for children. The mean wait times were not significantly different between urban and rural practices for adults or children (p>0.05) (Table 2).

State

The rates of successfully obtaining appointments in Maryland and Michigan were 62% [57, 67] and 80% [75, 84] (p<0.001), respectively, for adults and 46% [40, 51] and 63% [58, 69] (p<0.001), respectively, for children. The mean wait times were 12 [10, 14] (SD=14) and 19 [16, 23] (SD=25) days (p<0.001) in Maryland and Michigan, respectively, for adults; and 11 [9,13] (SD=12) and 16 [13, 19] (SD=22) days (p=0.01) for children (Table 2).

Factors Associated with Odds of an Appointment

Table 3 contains results of multivariable models presenting the adjusted odds of receiving an appointment for patients with Medicaid and BCBS insurance. Adult patients with Medicaid had significantly decreased odds of receiving an appointment compared to those with BCBS (OR=0.41, [0.28, 0.59], p<0.01), independent of other patient and provider characteristics. Adults also had increased odds of obtaining an appointment with an optometrist (OR=1.91, [1.31, 2.79], p<0.01) compared to an ophthalmologist, and if they were located in Michigan (OR=2.40 [1.49, 3.87], p<0.01) rather than Maryland. Other factors, including sex of the provider, urban or rural location, median household income and the proportion of minorities in the community were not significantly associated with receipt of an appointment when adjusting for insurance type.

Table 3.

Odds of Successfully Scheduling Appointment

| Variables | Odds Ratio | [95% Confidence Interval] | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| ADULTS | ||||

|

| ||||

| BCBS | Reference | |||

| Medicaid | 0.41 | 0.28 | 0.59 | <0.01 |

|

| ||||

| Ophthalmologist | Reference | |||

| Optometrist | 1.91 | 1.31 | 2.79 | <0.01 |

|

| ||||

| Female sex of provider | Reference | |||

| Male sex of provider | 1.21 | 0.81 | 1.82 | 0.36 |

|

| ||||

| Maryland | Reference | |||

| Michigan | 2.40 | 1.49 | 3.87 | <0.01 |

|

| ||||

| Rural | Reference | |||

| Urban | 0.66 | 0.40 | 1.09 | 0.11 |

|

| ||||

| Minority Populationa | ||||

| ≤50% | Reference | |||

| >50% | 1.13 | 0.67 | 1.90 | 0.66 |

|

| ||||

| Median Household Incomea | ||||

| $30,001 – 50,000 | Reference | |||

| $50,001 – 70,000 | 1.32 | 0.76 | 2.29 | 0.32 |

| $70,001 – 90,000 | 1.66 | 0.78 | 3.53 | 0.19 |

| $90,001 + | 1.05 | 0.58 | 1.88 | 0.88 |

|

| ||||

| CHILDREN | ||||

|

| ||||

| BCBS | Reference | |||

| Medicaid | 0.41 | 0.28 | 0.60 | <0.01 |

|

| ||||

| Ophthalmologist | Reference | 11.9 | ||

| Optometrist | 8.00 | 5.37 | <0.01 | |

|

| ||||

| Female sex of provider | Reference | |||

| Male sex of provider | 0.99 | 0.65 | 1.50 | 0.95 |

|

| ||||

| Maryland | Reference | |||

| Michigan | 1.68 | 1.04 | 2.73 | 0.035 |

|

| ||||

| Rural | Reference | |||

| Urban | 0.59 | 0.36 | 0.96 | 0.033 |

|

| ||||

| Minority Populationa | ||||

| ≤50% | Reference | |||

| >50% | 0.62 | 0.36 | 1.08 | 0.092 |

|

| ||||

| Median Household Incomea | ||||

| $30,001 – 50,000 | Reference | |||

| $50,001 – 70,000 | 0.99 | 0.57 | 1.70 | 0.96 |

| $70,001 – 90,000 | 0.83 | 0.38 | 1.81 | 0.65 |

| $90,001 + | 0.74 | 0.39 | 1.39 | 0.34 |

These data are for the counties in which practices were located

Child patients with Medicaid also had significantly decreased odds of receiving an appointment compared to those with BCBS (OR=0.41, [0.28, 0.60], p<0.01), independent of other patient and provider characteristics. Children also had increased odds of obtaining an appointment with an optometrist (OR=8.00, [5.37, 11.9], p<0.01) compared to an ophthalmologist and if they were located in Michigan (OR=1.68 [1.04, 2.73], p=0.035) rather than Maryland. Children had decreased odds of receiving an appointment with providers in an urban location (OR=0.59, [0.36, 0.96], p=0.033). Other factors, including sex of the provider, median household income and the proportion of minorities in the community were not significantly associated with receipt of an appointment when adjusting for insurance type.

Discussion

This study showed that adults and children with Medicaid were less successful in making eye care appointments than those with BCBS insurance. The most commonly provided reason for not offering appointments to patients with Medicaid was that the practice did not accept their insurance. However, there was no difference in wait times for appointments based on insurance type once an appointment was obtained.

In our analyses, the odds of receiving an appointment if an individual had Medicaid were approximately 60% lower for both adults and children, independent of provider type, practice location or community characteristics like urban or rural setting, median household income and the proportion of minorities in the county. One potential explanation for this may be differences in reimbursement rates by Medicaid and other insurers. The 2017 Medicaid reimbursement rates for a new patient eye exam (CPT code 92004) were just $77.46 in Maryland34 and $56.06 in Michigan,35 while Medicare and private insurers often reimburse more than two to three times this amount.36 Some practices may opt to not see patients with Medicaid due to the administrative burden associated with the Medicaid program.37 Furthermore, among vulnerable populations, social challenges like poor access to transportation, securing childcare, and being able to take time off of work may contribute to a greater frequency of missed appointments, a finding which has been demonstrated among patients with Medicaid.38 Since missed appointments may represent a greater financial burden than low reimbursement, this might cause some providers to limit the number of patients with Medicaid that they are willing to care for.

Wait times were longer with ophthalmologists and independent of their insurance type, patients were more likely to receive an appointment with an optometrist. The reasons for this may include that optometrists are more likely than general ophthalmologists to treat children; there are many times fewer ophthalmologists than optometrists in the United States; and ophthalmologists generally care for more complex patients and spend a portion of their time away from the clinic performing surgery. Additionally, the likelihood of obtaining an appointment varied by state, potentially reflecting variations in Medicaid programs between Maryland and Michigan, as well as the role of the state in promoting access to care for vulnerable populations.

The trends identified in our study reflect similar findings in other medical fields, including primary care28 and specialties like orthopedics,29 endocrinology,30 and psychiatry31 that have also demonstrated that patients with Medicaid are less successful in obtaining appointments. These studies had similar experimental designs to the present one, utilizing simulated patient callers with a specific common clinical complaint. However, not all of these studies accounted for geographic location or provider type, such as physician versus advanced practice provider (e.g., physician’s assistant or nurse practitioner).

It is well-known that lower socioeconomic status is associated with decreased healthcare utilization, including preventative disease screenings,39 and worse health outcomes.40,41 This disparity may be even starker for vision care, which is not mandated for adults in the Affordable Care Act (ACA). Similarly, dental care is also not required by the ACA for children or adults,42 and parents of publicly insured children were more likely to report that their child had a dental problem in the last year compared to parents of privately insured patients.43 Within the field of ophthalmology, studies have shown that patients with Medicaid have a low rate of annual diabetic eye exams44 and receive less glaucoma care than those with commercial health insurance.32 The present study further demonstrated that Medicaid patients have more difficulty obtaining eye care appointments, suggesting that this may be an additional contributor to disparities in eye health. Of note, over 20% of practices in rural areas of Maryland and Michigan did not provide an appointment to adults with Medicaid and individuals with Medicaid in these areas may have to travel long distances to obtain care given the small number of eye care providers in their areas.

There are some limitations to this study. Our study may not be generalizable to all locations in the United States. Since private insurance coverage varies by state and Medicaid is state administered, we cannot be certain that accessibility would be similar in other parts of the country. Phone calls were made between January and July and the appointment schedules at practices may vary throughout the year. Also, given that patients were simulated, we could not provide offices with specific details such as insurance plan numbers, which may have decreased the likelihood of obtaining an appointment. In addition, these data do not reflect other barriers that may exist such as language barriers, transportation, and work schedules, which may further contribute to the difficulty of obtaining an appointment. There also may be confounders that contributed to the likelihood of successfully obtaining an appointment. For example, certain types of practices or providers may be more likely to accept different Medicaid Managed Care Organizations, information that was not collected in this study. In some practices certain patients may need a referral in order to be seen, either from a primary care doctor or another eye care provider. Additionally, not all eye care providers care for the types of patients described in this study; specifically, many subspecialist ophthalmologists may not see patients for routine diabetic eye exams and/or failed vision screenings.

In conclusion, this study suggests that lower provider acceptance of Medicaid as an important barrier to obtaining eye care for patients with Medicaid. While unproven at this time, policy change to incentivize eye care providers to care for patients with Medicaid could help to improve access for this population. For example, an increase in Medicaid reimbursement for primary care services resulted in greater appointment availability for new Medicaid patients45 and the same might be true if Medicaid reimbursement for eye care were increased. Also, while not proven, other possible solutions to improve access to eye care include social workers or case managers at primary care offices to help coordinate appointments, and the design of an easy to use centralized resource with information about the insurance plans that providers accept. Future work should examine the effectiveness of these kinds of interventions to improve access to eye care and outcomes among patients with Medicaid.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

Question

Is there a difference in access to eye care appointments between patients with Medicaid and those with private health insurance?

Findings

In this prospective observational study, the proportion of callers who successful obtained eye care appointments for adults and children with Medicaid was less than for those with private health insurance, but there was no difference identified in appointment wait times when an appointment was made.

Meaning

Difficulty obtaining appointments may explain, in part, the lower rates of utilization of recommended eye care services among those with Medicaid.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the medical practices in MD and MI for participating in our study.

Funding/Support: This study was supported by grants from the Kellogg Foundation (JDS, JRE) Research to Prevent Blindness (JDS, JRE), the National Eye Institute (R01EY026641 to JDS and K23EY027848 to JRE).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Joshua R. Ehrlich, MD, MPH and David S. Friedman, MD, PhD, MPH had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Varadaraj, Friedman, Kourgialis

Acqusition, analysis, or interpretation of data: all authors

Drafting of manuscript: Lee, Varadaraj

Critical revision of manuscript: Varadaraj, Friedman, Stein, Ehrlich

Statistical analysis: Lee, Varadaraj

Study supervision: Friedman, Ehrlich

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. No other disclosures were reported.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

References

- 1.Improving the nation’s vision health: A coordinated public health approach. Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Making eye health a population health imperative: Vision for tomorrow. The National Academies Press; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Care First. [Accessed on January 17, 2018];Our Vision Plans. https://individual.carefirst.com/individuals-families/plans-coverage/vision/our-vision-plans.page.

- 4.Blue Cross Blue Shield Blue Care Network of Michigan. [Accessed on January 17, 2018];Dental and Vision Plans. https://www.bcbsm.com/index/plans/dental-insurance-michigan/2018/vision.html.

- 5.Canedo JR, Miller ST, Schlundt D, Fadden MK, Sanderson M. Racial/Ethnic disparities in diabetes quality of care: The role of healthcare access and socioeconomic status [published on January 11, 2017] J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. doi: 10.1007/s40615-016-0335-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galor A, Diane Zheng D, Arheart KL, Lam BL, McCollister KE, Ocasio MA, et al. Influence of socio-demographic characteristics on eye care expenditure: Data from the medical expenditure panel survey 2007. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2015;22(1):28–33. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2013.783081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lipton BL, Decker SL. The effect of medicaid adult vision coverage on the likelihood of appropriate correction of distance vision: Evidence from the national health and nutrition examination survey. Soc Sci Med. 2016;150:258–67. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.10.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shin P. Assessing the need for on-site eye care professionals in community health centers. Policy Brief George Wash Univ Cent Health Serv Res Policy. 2009:1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ehrlich, et al. Assessing Geographic Variation in Strabismus Diagnosis among Children Enrolled in Medicaid. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(9):2013–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blanchard J, Ogle K, Thomas O, Lung D, Asplin B, Lurie N. Access to appointments based on insurance status in Washington, D.C. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008;19(3):687–96. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim CY, Wiznia DH, Roth AS, Walls RJ, Pelker RR. Survey of patient insurance status on access to specialty foot and ankle care under the affordable care act. Foot Ankle Int. 2016;37(7):776–81. doi: 10.1177/1071100716642015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maryland Medical Programs. [Accessed November 1, 2016];Provider Directory. https://encrypt.emdhealthchoice.org/searchable/main.action.

- 13.Blue Cross Complete of Michigan LLC. [Accessed on June 29, 2017];Find a Doctor, Pharmacy, or Dentist. http://www.mibluecrosscomplete.com/find-doctor.html.

- 14.Upper Peninsula Health Plan. [Accessed on June 6, 2017];Provider and Pharmacy Directory. 2016 https://www.uphp.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/SNPProvPharmDirectory.pdf.

- 15.Priority Health Choice. [Accessed on June 14, 2017];Find A Doctor. http://priorityhealth.prismisp.com.

- 16.UnitedHealthcare Community Plan. [Accessed on June 28, 2017];Find a Doctor. http://www.americhoice.com/find_doctor/first.jsp?xplan=uhcmi&xtitle=Doctor.

- 17.Vision Service Plan. [Accessed on June 29, 2017];Find a Doctor by Location/Services. https://www.vsp.com/find-eye-doctors.html?id=guest&WT.ac=fad-guest.

- 18.Harbor Health. Find A Provider. https://providersearch.molinahealthcare.com/Provider/ProviderSearch?RedirectFrom=MolinaStaticWeb.

- 19.Harbor Health. [Accessed on June 9, 2017];Find A Provider. https://www.harborhealthplan.com/members/medicaid-directory.

- 20.Heritage Vision Plans. [Accessed on June 28, 2017];Midwest Provider Directory. http://www.heritagevisionplans.com/

- 21.McLaren Health Plan Medicaid. [Accessed on June 20, 2017];Provider Directory. http://www.mclarenhealthplan.org/uploads/public/documents/healthplan/documents/Provider%20Directory/MHP%20Directory.pdf.

- 22.Health Alliance Midwest Health Plan. [Accessed on June 20, 2017];Provider Directory. http://www.midwesthealthplan.com/MiHealthLink/FindAProvider.aspx?status=directory.

- 23.Total Health Care. [Accessed on June 8, 2017];Provider Directory Medicaid & Health Michigan Plan. https://thcmi.com/PDF/members/PDF/Directories/Medicaid-ProviderDirectory.pdf.

- 24.Health Alliance Plan of Michigan. [Accessed on June 9, 2017];Provider Lookup Online. http://www.providerlookuponline.com/HAP/po7/Search.aspx.

- 25.Aetna Better Health of Michigan. [Accessed on June 28, 2017];Provider type chart. https://www.aetnabetterhealth.com/Michigan/find-provider.

- 26.Maryland Counties by Population. [Accessed on January 17, 2018];Maryland Demographics. https://www.maryland-demographics.com.

- 27.Michigan Counties by Population. [Accessed on January 17, 2018];Michigan Demographics. https://www.michigan-demographics.com.

- 28.Coffman JM, Rhodes KV, Fix M, Bindman AB. Testing the Validity of Primary Care Physicians’ Self-Reported Acceptance of New Patients by Insurance Status. Health Serv Res. 2016;51(4):1515–32. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wiznia DH, Nwachuku E, Roth A, Kim CY, Save A, Anandasivam NS, Medvecky M, Pelker R. The Influence of Medical Insurance on Patient Access to Orthopaedic Surgery Sports Medicine Appointments Under the Affordable Care Act. Orthop J Sports Med. 2017;5(7):2325967117714140. doi: 10.1177/2325967117714140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wiznia DH, Ndon S, Kim CY, Zaki T, Leslie MP. The Effect of Insurance Type on Fragility Fracture Patient Access to Endocrinology Under the Affordable Care Act. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2017;8(1):23–29. doi: 10.1177/2151458516681635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wiznia DH, Maisano J, Kim CY, Zaki T, Lee HB, Leslie MP. The effect of insurance type on trauma patient access to psychiatric care under the Affordable Care Act. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2017;45:19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2016.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elam AR, Andrews C, Musch DC, Lee PP, Stein JD. Large Disparities in Receipt of Glaucoma Care between Enrollees in Medicaid and Those with Commercial Health Insurance. Ophthalmology. 2017;124(10):1442–1448. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.United States Census Bureau. [Accessed on January 16, 2018];QuickFacts. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table//PST045217.

- 34.Professional Services Fee Schedule. Department of Health and Mental Hygiene; Jan, 2017. [Accessed on January 23, 2018]. https://mmcp.health.maryland.gov. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vision Services Database. Michigan Department of Health and Human Services; Jan, 2017. [Accessed on January 23, 2018]. http://www.michigan.gov. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Physician Fee Schedule Search. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; [Accessed on January 26, 2018]. https://www.cms.gov/apps/physician-fee-schedule. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Long SK. Physicians May Need More Than Higher Reimbursements To Expand Medicaid Participation: Findings From Washington State. Health Affairs. 2013;32(9):1560–1567. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nguyen DL, DeJesus RS, Wieland ML. Missed Appointments in Resident Continuity Clinic: Patient Characteristics and Health Care Outcomes. Journal of Graduate Medical Education. 2011;3(3):350–355. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-10-00199.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim MJ, Lee H, Kim EH, Cho MH, Shin DW, Yun JM, Shin JH. Disparity in Health Screening and Health Utilization according to Economic Status. Cancer. 2017;123(20):4048–56. doi: 10.4082/kjfm.2017.38.4.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Griffith K, Evans L, Bor J. The Affordable Care Act Reduced Socioeconomic Disparities In Health Care Access. Health Affairs. 2017;36(8):1503–10. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rohlfing ML, Mays AC, Isom S, Waltonen JD. Insurance status as a predictor of mortality in patients undergoing head and neck cancer surgery. Laryngoscope. 2017 doi: 10.1002/lary.26713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.What Marketplace Plans Cover. [Accessed on October 7, 2017];Healthcare.gov. https://www.healthcare.gov/coverage/what-marketplace-plans-cover/

- 43.Shariff JA, Edelstein BL. Medicaid Meets Its Equal Access Requirement for Dental Care, But Oral Health Disparities Remain. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35(12):2259–2267. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hatef E, Vanderver BG, Fagan P, Albert M, Alexander M. Annual diabetic eye examinations in a managed care. Medicaid population. 2015;21(5):e297–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Polsky D, Richards M, Basseyn S, Wissoker D, Kenney GM, Zuckerman S, et al. Appointment Availability after Increases in Medicaid Payments for Primary Care. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372(6):537–545. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1413299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.