Abstract

Background:

New cervical cancers continue to be diagnosed, despite the success of Pap tests. In an effort to identify pitfalls limiting the diagnosis of adenocarcinoma, we reviewed the cytologic characteristics of endocervical adenocarcinomas in our population.

Methods:

ThinPrep® slides from 45 women with concurrent histologically confirmed cervical adenocarcinomas were retrospectively and semiquantitatively reviewed for 25 key cytologic traits. The original sign-out diagnosis, available clinical findings and high-risk human papillomavirus (HR HPV) results were also noted.

Results:

Abundant tumor cellularity, nuclear size 3–6 x normal, abundant 3-dimensional tumor cell groups, round cell shape, and cytoplasmic neutrophils characterized the 23 cases correctly identified as adenocarcinomas. Key reasons for undercalls included low tumor cellularity and low-grade columnar morphology. These also tended to correlate with low-grade or unusual adenocarcinoma variants on histology. Overall, 73% of the adenocarcinoma cases had a concurrent positive HR HPV test.

Conclusions:

Most endocervical adenocarcinomas can be accurately diagnosed in cases with classical features, but some cases continue to be problematic when evaluated based on cytologic features alone. Reflex HPV testing may help increase Pap test sensitivity for challenging cases with atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance. Occasional cases with negative HR HPV test results remain of concern.

Keywords: uterine cervical neoplasia, adenocarcinoma, cancer screening, cytodiagnosis, Papanicolaou test

Precis:

Retrospective review of 45 Pap tests from histologically-confirmed endocervical adenocarcinomas revealed that most cases can be recognized based on classical cytological criteria, while underdiagnosed cases tend to have low cellularity and columnar-shaped nuclei. Reflex HPV may be useful in increasing sensitivity for endocervical adenocarcinoma on Pap tests.

Introduction:

Despite the success of the Pap smear screening and the promise of HPV vaccination, approximately 12,990 new cervical cancers were identified in the United States in 2016.1 In an effort to improve our ability to recognize malignant cases in routine screening, we previously reported our experience with Pap test interpretation of a large population of women referred for workup of abnormal cervical cytology including women with cervical carcinoma2 and found that suboptimal (i.e., qualified adequacy and unsatisfactory) interpretations are increased in women with cancers compared with less significant diagnoses. This was particularly true for women with squamous cancers. We also found that Pap tests from women with adenocarcinomas were less likely to be recognized as malignant compared to those with squamous cancers, although most were recognized with some degree of abnormality.

Subsequently, we compared the cellular patterns of squamous cancers and adenocarcinomas3 and found that tumor diathesis was more pronounced in squamous cancers, which, with ThinPrep® Paps, was accompanied by differences in tumor cellularity. Specifically, the prominent tumor diathesis associated with squamous cancers was accompanied by fewer cells overall and fewer tumor cells. Conversely, adenocarcinoma cases had less diathesis and a larger population of normal-appearing endocervical cells.

Inasmuch as rates of cervical adenocarcinoma diagnoses appear to be increasing relative to squamous cancers4,5, these findings led us to focus on the cytological characteristics of adenocarcinomas in our patient population in an effort to identify features that may be associated with under-diagnosis of this lesion.

Methods:

The ThinPrep® Pap tests were originally collected from 45 women with a concurrent histologic diagnosis of cervical adenocarcinoma as part of the Study to Understand Cervical Cancer Early Endpoints and Determinants (SUCCEED) 6,7,8 and the NCI-OUHSC Biopsy Studies.9 Each woman provided informed consent and the studies were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center and the National Cancer Institute. The 3015 study participants were women aged 18–85 years referred for follow-up of abnormal Pap tests or a diagnosis of cancer between 2002–2010. Women who had previous surgical treatment for cervical neoplasia, human immunodeficiency virus infection or were pregnant were excluded. At the time of study entry, participants provided informed consent and underwent ThinPrep® Pap test (Hologic Inc., Marlborough, Mass.) and colposcopy, with further treatment according to routine patient care guidelines. The ThinPrep® Pap tests were originally evaluated in a routine fashion by staff cytotechnologists and study cytopathologists at the University of Oklahoma Medical Center laboratories according to the 2001 Bethesda guidelines.10 An aliquot of each cytologic sample underwent HPV genotyping for 37 HPV genotypes using the Linear Array HPV Genotyping Test (Roche Molecular Diagnostics, Pleasanton, CA) as previously described.8 HPV16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66 and 68 were considered to be carcinogenic (HR). Adenocarcinoma cases interpreted as primary from the endometrium at hysterectomy were excluded from this study.

The 45 adenocarcinoma cases described here were extracted from our previous descriptions of this population2,3. The de-identified ThinPrep® slides were retrospectively reviewed for key cytologic elements (see below) without knowledge of the original cytologic interpretation. For each case, each element was assessed semiquantitatively: 0): Little or none; 1+) some; 2+) many/much; 3+) abundant.

We conducted chi-square tests to evaluate distributions of categorical variables. All statistical tests were 2-sided and considered to be significant at p < 0.05.

Results:

The key clinical characteristics of the adenocarcinoma patients included in this study are shown in Table 1. It is noteworthy that 73.3% of the cases were positive for high risk (HR) HPV genotypes. The cytologic features analyzed retrospectively in review of these slides are listed in Table 2.

Table 1:

Key clinicopathologic features of 45 cases of cervical adenocarcinoma

| TRAIT | NUMBER (%) |

|---|---|

| AGE (YEARS) ≤30 31−40 41−50 51−60 ≥61 |

6 (13.3) 14 (31.1) 12 (26.7) 9 (20.0) 4 (8.9) |

| STAGE 1A 1B1 1B2 2 3 4 Not Done |

2 (4.4) 25 (55.6) 5 (11.1) 7 (15.5) 1 ( 2.2) 2 ( 4.4) 3 ( 6.7) |

| FIGO GRADE 1 2 3 Not Done |

10 (22.2) 14 (31.1) 15 (33.3) 6 (13.3) |

| HPV STATUS High Risk Low Risk Negative Not Done |

33 (73.3) 1 ( 2.2) 10 (22.2) 1 ( 2.2) |

| ORIGINAL IMPRESSION ADENOCARCINOMA SQUAMOUS CARCINOMA AGC HSIL ASC-H ASCUS NEGATIVE UNSATISFACTORY |

24 (53.3) 0 (−) 11 (24.4) 4 ( 8.9) 1 ( 2.2) 2 ( 4.4) 2 ( 4.4) 1 ( 2.2) |

| ADEQUACY ADEQUATE UNSATISFACTORY |

44 (97.8) 1 ( 2.2) |

| LIMITING FACTORS BLOODY HYPOCELLULAR UNSATISFACTORY NO T-ZONE INFLAMMATION NONE |

4 ( 8.9) 1 ( 2.2) 6 (13.3) 1 ( 2.2) 34 (75.5) |

HPV – human papillomavirus; HSIL – high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; ASC-H – atypical squamous cells – cannot exclude a high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; AGC – atypical glandular cells; ASC-US – atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance

Table 2.

: Relative distribution of cytologic features in 45 cases of cervical adenocarcinoma

| TRAIT | Score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0−± | 1+ | 2+ | 3+ | |

| Few / none | Some | Many | Abundant | |

| Overall Tumor Cells | 0 (−) | 15 (33.3) | 12 (26.7) | 18 (40.0) |

| Normal endocervicals | 14 (31.1) | 21 (46.7) | 10 (22.2) | 0 (−) |

| BACKGROUND | ||||

| Blood | 14 (31.1) | 15 (35.6) | 12 (26.7) | 3 (6.7) |

| RBC’S | 13 (28.9) | 14 (31.1) | 15 (33.3) | 3 (6.7) |

| Diathesis | 5 (11.1) | 13 (28.9) | 9 (20.0) | 18 (40.0) |

| Inflammation | 4 (8.9) | 14 (31.1) | 19 (42.2) | 8 (17.8) |

| Histiocytes | 31 (68.9) | 12 (26.7) | 2 (4.4) | 0 (−) |

| Psammoma bodies | 45 (100) | 0 (−) | 0 (−) | 0 (−) |

| TUMOR CELL PATTERN | ||||

| 3-D Groups | 2 (4.4) | 11 (24.4) | 19 (42.2) | 13 (28.9) |

| Single Atypical Cells | 10 (22.2) | 26 (57.8) | 9 (20.0) | 0 (−) |

| TUMOR CELL MORPHOLOGY | ||||

| Columnar | 16 (35.6) | 11 (24.4) | 12 (26.7) | 6 (13.3) |

| Round/Oval | 2 (22.2) | 20 (44.4) | 14 (31.1) | 9 (20.0) |

| Frayed edges | 10 (22.2) | 18 (40.0) | 13 (28.9) | 4 (8.9) |

| Loss of polarity | 3 (6.7) | 18 (40.0) | 17 (37.8) | 7 (15.6) |

| Abundant cytoplasm | 7 (15.6) | 21 (46.7) | 14 (31.1) | 3 (6.7) |

| Cytoplasmic mucin | 34 (75.6) | 9 (20.0) | 2 (4.4) | 0 (−) |

| Polys in cytoplasm | 25 (55.6) | 15 (33.3) | 4 (8.9) | 1 (2.2) |

| NUCLEAR SIZE | ||||

| Nearly normal | 19 (42.2) | 19 (42.2) | 5 (11.1) | 2 (4.4) |

| 4–6X normal | 2 (4.4) | 9 (20.0) | 22 (48.9) | 12 (26.7) |

| >6x normal | 9 (20.0) | 21 (46.7) | 9 (20.0) | 6 (13.3) |

| Mitotic figures | 23 (51.1) | 16 (35.6) | 6 (13.3) | 0 (−) |

| NUCLEOLI | ||||

| Large single | 15 (33.3) | 14 (31.1) | 11 (24.4) | 5 (11.1) |

| Multiple | 22 (48.9) | 18 (40.0) | 5 (11.1) | 0 (−) |

| Small, definite | 4 (8.9) | 13 (28.9) | 16 (35.6) | 12 (26.7) |

| Inconspicuous | 24 (53.3) | 17 (37.8) | 4 (8.9) | 0 (−) |

The relative distribution of the various cellular characteristics found in these cases of cervical adenocarcinoma are shown in Table 2. In aggregate, the characteristics most frequently recognized in this population of cervical adenocarcinomas include: abundant cells including tumor cells, abundant 3-dimensional tumor cell groups, nuclear size 3–6x normal, tumor diathesis and small, definite nucleoli. Conversely, psammoma bodies and histiocytes were rarely noted. The remaining traits were variably present in this group of cases.

While all cases in this study were histologically confirmed adenocarcinomas coincident with the Pap test, there were various interpretations at the time of original cytology sign-out. These included 23 cases correctly diagnosed as adenocarcinoma (CA); 15 cases as HSIL, AGC or AIS (HG), and 6 cases diagnosed as LSIL, ASC, ASC-H or NILM (<HG). The latter cases were interpreted as undercalls for the purposes of this study. One case was unsatisfactory due to hypocellularity.

In an effort to identify factors that facilitated or hampered identification of adenocarcinoma, we compared the various cytologic characteristics in cases with the various diagnostic interpretations. The key findings in these comparisons are found in Table 3.

Table 3:

Key cytologic traits differentiating adenocarcinoma interpretations from cases with lesser diagnoses

| Carcinoma (N=23) |

Less than carcinoma (N=15) |

Less than high grade (N=6) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trait | Number* (%) | Number* (%) | p-value | Number* (%) | p-value |

| Overall tumor cellularity | 19 (82.6%) | 8 (53.3%) | 0.052 | 3 (50.0%) | 0.04 |

| Cohesive 3D cell groups | 19 (82.6%) | 10 (66.6%) | 0.26 | 3 (50.0%) | 0.04 |

| Round/oval cell shape | 17 (73.9%) | 4 (26.6%) | 0.01 | 1 (16.7%) | 0.005 |

| Groups with frayed edges | 11 (47.8%) | 6 (40.0%) | 0.64 | 0 (−) | 0.02 |

| Columnar shape | 5 (21.7%) | 8 (53.3%) | 0.04 | 4 (66.7%) | 0.01 |

| Normal appearing endocervicals | 2 ( 8.7%) | 6 (40.0%) | 0.02 | 2 (33.3%) | 0.18 |

Number= Sum of the number of cases with the indicated trait showing “many” and “abundant” cells

Cases correctly identified as adenocarcinoma:

When comparing the findings in the 23 cases that were correctly identified as adenocarcinoma at the time of original sign-out compared with those of lesser diagnoses most of the cases (19/23, 82.6%) correctly interpreted as cancer had “many” or “abundant” tumor cells compared with those given lesser diagnoses (p=0.02).

Similarly, most of the cases correctly interpreted as adenocarcinoma (17/23, 73.9%) had “many” or “abundant” tumor cells with a round/oval appearance, possibly indicating a higher grade compared with 6/22 (27.3%) with lesser diagnoses (p=0.002).

The key cytologic features that were dominant in those 23 cases that were correctly identified as adenocarcinoma at the time of original sign-out compared with those of lesser diagnoses included overall greater tumor cellularity (19/23, 82.6%), cohesive 3-dimensional cell groups (19/23, 73.9%) and round-oval tumor cell shape (17/23, 73.9%) (Table 3). In contrast, the cases correctly interpreted as cancer had fewer normal-appearing endocervical cells and fewer tumor cells with a columnar configuration (Table 3). Overall, 19 (82.6%) of these cases harbored HR HPV genotypes.

Cases interpreted as less than HSIL:

Six cases were originally interpreted as less than high grade and are considered to be undercalls for the purpose of this study. The comparison results between these cases and the cancer cases are shown in Table 3. The features most clearly distinguishing the cases interpreted as adenocarcinoma from these cases were increased tumor cellularity, increased presence of cohesive, three-dimensional cell groups, round-oval tumor cell shape and cell groups with frayed edges. The cases with lesser diagnoses were notable for having fewer tumor cells and for having columnar-shaped tumor cells.

An additional case interpreted as unsatisfactory for cytologic diagnosis due to insufficient cellularity was not included in the above comparison. Four of seven (57%) of these cases were positive for HR HPV DNA, although 2 cases were unusual histologic types that do not appear to be HPV associated (Table 4).

Table 4.

Characteristics of cases with undercalled ThinPrep®Pap tests

| No | Patient | Pap Diagnosis | Histology | Grade | Size (cm) | HPV | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 36 Y/O WF G0 | Unsatisfactory | Clear cell adenocarcinoma, Stage 1B1 | NA | 1.0 | NEG | Excess blood and very low cellularity. Several large cell groups present (>30 cells) in bloody rim were all monomorphic- a clue that this was not a normal cell population. |

| 2 | 35 Y/O WF G3 | NILM | Cervical adenocarcinoma, usual type, Stage 1B1 | 1 | 1.0 | 16,18 | Very scant tumor cells; small lesion; tightly cohesive cell groups with overlapping nuclei |

| 3 | 57 Y/O WF | NILM | Cervical adenocarcinoma, usual type, Stage 1B1 | 2 | 1.4 | 16 | The most prominent part of this case is the light diathesis in the background. Rare large groups of glandular cells with rim of ghost rbc. |

| 4 | 67 Y/O WF | ASC with obscuring inflammation | Poorly differentiated carcinoma, concerning for carcinosarcoma | 3 | 3.0 | NEG | Only rare epithelial cells present with a rim of mostly neutrophils. The epithelial cells do not show definite malignant features. Some laboratories could call unsatisfactory. |

| 5 | 54 Y/O | ASC-US | Cervical adenocarcinoma, usual type, Stage 1B1 | 1 | 1.0 | 16 | Sheets of atrophic squamous cells are distractors; Some large 3-D groups of small glandular cells with tight overlapping nuclei; little atypia. Rare apoptotic cells present |

| 6 | 35 Y/O | ASC-H | Cervical adenocarcinoma, usual type, Stage 1B1 | 1 | 1.2 | 18 | Many of the tumor cells have bland chromatin and multiple small nucleoli; Oval cytoplasm; some with tails; Although many tumor cells are enlarged; others are overlap with normal size nuclei; Prominent neutrophils in background. Several cell groups have definite mucin globules with signet ring features. Diathesis inconspicuous in this case although a few aggregates of ghost rbcs are present. |

| 7 | 35 Y/O | ASC-H | Mixed cervical adenocarcinoma, usual type and small cell neuroendocrine, Stage 4B | 1 | Not done | 16 | At low power the background looks clean. But at higher power, aggregates of ghost rbcs can be seen. Very rare, small, highly cohesive cell groups are present that can be easily overlooked. Small coagulum of fibrin, PMNs and occasional small epithelial cells are unusual. |

HPV - Human papillomavirus; Y/O - year old; WF - white female; NA - not applicable; NILM - negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy; rbc - red blood cell; ASC-US - atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance; ASC-H - atypical squamous cells cannot exclude a high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion

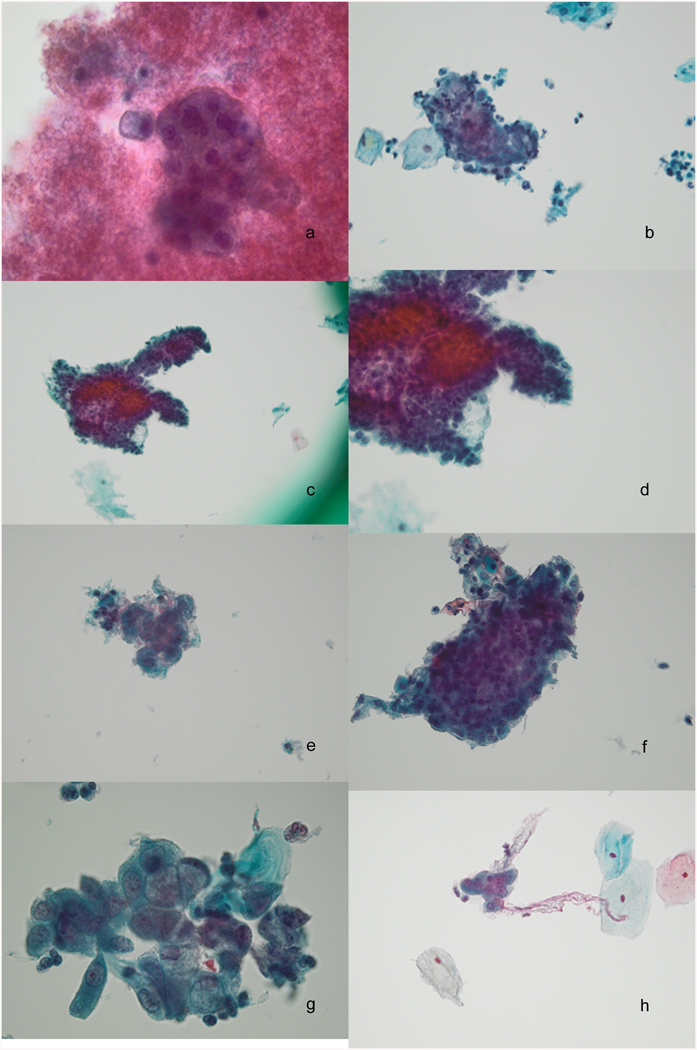

We re-reviewed the ThinPrep® slides from these seven cases after this analysis in an effort to understand the reasons for the undercalls and the summaries are shown in Table 4 with representative images in Figure 1. Overall, there were two major reasons for the undercalls 1) few tumor cells and 2) low tumor grade with bland appearing tumor cells. Both problems were present in some of these cases.

Figure 1.

Images from cases with undercalled Pap tests [case numbers correspond to table 4]. a, Case 1, Dense bloody diathesis obscures a large monomorphic cell group in a hypocellular specimen, 60x; b, Case 2, A tightly cohesive group with overlapping nuclei such that nuclear detail is obscured, 40x; c and d, Case 3, light diathesis with a rare large highly cohesive group of glandular cells with obscured cellular detail, 20x and 40x; e, Case 4, Rare small epithelial group with neutrophils in a sparsely cellular sample, 40x; f, Case 5, Rare large 3-D group of crowded but minimally atypical glandular cells with abundant atrophic squamous sheets, 40x; g, Case 6, This pattern with enlarged nuclei and prominent intracytoplasmic mucin was rare in this sample, 60x; h, Case 7, Very scant small cohesive cell groups with a clean background are easy to overlook, 40x.

The pattern of hypocellularity in malignant ThinPrep® Pap tests with dense rings of diathesis demarcating an empty central portion has been well described.11, 12 We highlighted this as a particular problem for squamous cell cancer cases.3 We found this to be a lesser problem for ThinPrep® slides from adenocarcinoma cases, but one case in this group of undercalls, a clear cell carcinoma, had this pattern (Fig 1a). In addition, other cases showed an unremarkable pattern of overall cellularity but had few recognizable tumor cells suggesting sampling issues. In these cases, the number and characteristics of the tumor cells were insufficient to trigger the recognition of a significant lesion.

In some cases, small groups of tightly cohesive tumor cells were found (Fig 1b) but these were smaller than the large groups typically seen in adenocarcinoma. In addition, it was difficult to evaluate the nuclear features for the cells in these groups due to crowding. Only Case 6 (Fig 1g) had a rare group that could have raised concern for possible adenocarcinoma; however, this was only recognized on re-review.

The second problem relates primarily to well differentiated tumors of usual endocervical type in which the cytologic characteristics of the tumor cells overlap with benign reactive changes. Recognition of these cases was also hampered by varying degrees of acute inflammation. In addition, nuclear criteria were bland with minimally enlarged nuclei, bland uniform chromatin pattern and small nucleoli. Typically the under-called cases in our population had a combination of few tumor cells and small tumor cell groups as well as bland cytologic features. These cases also had subtle patterns of amorphous debris and ghost red cells that helped obscure the cellular detail in the dense cell groups. While this latter finding can raise the index of suspicion and cause the cytologist to look for more diagnostic criteria in the slide, this pattern can be seen in benign cases and cannot alone be relied upon to identify a high risk glandular lesion.

Overall, the cytologic characteristics of these undercalled cases were insufficient to warrant a diagnosis of adenocarcinoma even on re-review.

Discussion:

Previous studies analyzing atypical glandular cells in Pap tests, including liquid-based Pap tests, have reported difficulties in accurate interpretation both in detection and in accurate categorization. These difficulties involved discrimination of glandular lesions from squamous lesions13 and from benign glandular mimics.14–19 Our previous studies with cytologic diagnosis of cervical cancers have reported greater difficulty in recognizing adenocarcinomas compared with squamous cancers. 2,3

This study was undertaken in an effort to increase our ability to recognize the salient features of cervical adenocarcinoma and its precursors on cytologic screening and to identify possible reasons for undercalls. The key cytologic criteria that allowed recognition of adenocarcinoma in this study reflect published criteria including abundant large atypical tumor cell groups with atypical single cells. Notably, tumor diathesis was generally present but, as we have previously reported, to a lesser extent than for squamous cancers.2 When we reevaluated the cases that we considered to be under-called, the difficulties generally related to hypocellularity (particularly of tumor cells, even if overall cellularity was satisfactory) and well differentiated adenocarcinomas with columnar cells and minimal atypia. While the current cytologic criteria for adenocarcinoma20 were recognized in most of the cases in this study, we reluctantly conclude that some cases continue to be problematic upon re-evaluation using cytologic features alone.

There have been a variety of reports describing criteria for distinguishing benign glandular mimics including reactive inflammatory changes, microcystic glandular hyperplasia, and ciliated metaplasia from glandular neoplasia.14,17–19. Lee et al 14 described a case series in which glandular lesions were both overcalled and undercalled on cytologic criteria alone and a subsequent report17 documented a high level of interobserver disagreement for cases interpreted as AGC. Schoolland et al 21 reported significant sampling and diagnostic errors in 36 smears from 24 women with cervical adenocarcinoma. Ruba et al 22 described sampling and interpretive errors for the cytologic diagnosis of adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) and concluded that diagnostic errors were associated with the presence of only few, poorly preserved abnormal cells and to an overly conservative approach to the assessment of abnormal glandular groups/cells. In comparing the screening histories of women with cervical cancer, Pak et al23 found that women with adenocarcinoma had been screened more regularly and were more likely to have negative Paps than those with squamous cancers. Thus, while adenocarcinoma and AIS can be accurately diagnosed in a large number of cases with classical features of malignancy, a variable number of cases can be missed due to sampling and interpretative errors when evaluated by cytology alone.

Because of the variation in histologic cell types and the variety of cytologic patterns of cervical adenocarcinoma, it occurred to us that sensitivity could be improved with an adjunct test such as HPV which is more objective. Recent large international studies of cervical adenocarcinomas report approximately 62%24 of cervical adenocarcinomas harbor HR HPV DNA including 71.8% 25 of adenocarcinomas of usual type. A pooled analysis of HPV screening trials suggested that HPV screening versus cytology screening can lead to a stronger relative reduction of adenocarcinomas compared to squamous cell cancers.26

When Bethesda 2001 introduced HPV testing into cervical cancer screening as a reflex test, it was aimed to efficiently triage the large number of ASC cases but did not include AGC.27 Current guidelines for the follow-up of AGC call for referral to colposcopy. 28 As a result, some cytologists may use a higher threshold for AGC compared with ASC. Earlier studies have shown that AGC is associated with a high rate of high grade lesions, particularly HSIL.14 This may in part be influenced by conservative interpretation of AGC to prevent unnecessary colposcopy visits and LEEPs.

The results of our study cause us to question whether use of HPV testing for AGC should be reconsidered. Inasmuch as HPV testing is widely used for ASC reflex and as a co-test for women over 30, reflex HR HPV testing for AGC could increase our sensitivity for cervical glandular neoplasia with minimal cost and inconvenience. Four European countries have included AGC as an indication for triage to HPV testing in some European countries.29 Based upon the earlier literature 15,17,18 and our own experience, this high threshold for AGC may allow pre-cancer and small, well-differentiated lesions to be under-interpreted as reactive changes in an effort to avoid unnecessary colposcopies for reactive lesions.

Reflex HPV testing for AGC could be added to the follow-up algorithm as an initial step to distinguish high risk HPV-associated cervical lesions from benign mimics and endometrial lesions. The threshold for AGC could thus be lowered as well if the concern for unnecessary colposcopies is removed. Additional safeguards can continue to be included for HPV negative cases to detect endometrial lesions. Previous authors have reported the utility of HPV testing in AGC cases with favorable results 16,30,31. Ronnett et al16 found that the combination of cytology interpretation and HPV testing was associated with a high rate of detection of significant glandular lesions. In our sample, 33/45 (73%) of cytologic samples of cervical adenocarcinomas were HR HPV positive. Thus, detection of adenocarcinoma and precursors in screening test can reasonably be expected to be improved by HPV testing of AGC Pap tests. Kinney at al 32 have reported adenocarcinoma cases in their co-testing experience that were detected by a positive HPV test when cytology was negative. In addition, the accuracy and reproducibility of colposcopy as the gold standard for lesion detection has been questioned 33. However, it should also be noted that a small number of cervical adenocarcinomas may not be detected by HR HPV testing. Indeed, two cases in our problematic case list were cancers of unusual type that were not associated with HR HPV. This can be due to falsely negative HPV DNA tests but also due to the presence of HPV negative cancers including special types such as clear cell or serous cancers. Detection of these cases will continue to rely on astute cytologic evaluation and clinical parameters.

In summary, while the majority of cervical adenocarcinomas can be detected by classical cytologic criteria, recognition of some cases was hampered by subtle tumor diathesis, few tumor cells and very bland cytologic features in well-differentiated tumors. We propose that reflex HR HPV testing for AGC, as for ASC, can help to increase sensitivity for low grade adenocarcinomas of usual type including precursor lesions, although guidelines for identification of HPV negative cervical cancers and endometrial cancers should remain.

Acknowledgments

Funding support:

Funding for the Study to Understand Cervical Cancer Early Endpoints and Determinants (SUCCEED) was provided through the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics. [Contract N02-CP-31102, Walker (PI)]

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures:

Dr. Schiffman has received assays at no cost from Roche Molecular Systems and from Becton Dickinson for studies of human papillomavirus testing and cytology as part of cervical screening.

References:

- 1.SEER Cancer Stat Facts: Cervix Uteri Cancer National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/cervix.html, Accessed February/22/2017 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhao L, Wentzensen N, Zhang RR, et al. Factors associated with reduced accuracy in Papanicolaou tests for patients with invasive cervical cancer. Cancer Cytopathol. 2014;122:694–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conrad R, Wentzensen N, Zhang RR, et al. Distribution of cell types differs in Papanicolaou tests of squamous cell carcinomas and adenocarcinomas. J Am Soc Cytopathol. 2017; 6:10–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adegoke O, Kulasingam S, Virnig B. Cervical cancer trends in the United States: a 35-year population-based analysis. J Womens Health 2012; 21:1031–1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang SS, Sherman ME, Hildesheim A, et al. Cervical adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma incidence trends among White women and Black women in the United States for 1976–2000. Cancer 2004; 100:1035–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang SS, Zuna RE, Wentzensen N, et al. Human papillomavirus cofactors by disease progression and human papillomavirus types in the study to understand cervical cancer early endpoints and determinants. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009; 18:113–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wentzensen N, Schiffman M, Dunn ST et al. Grading the severity of cervical neoplasia based on combined histopathology, cytopathology, and HPV genotype distribution among 1,700 women referred to colposcopy in Oklahoma. Int J Cancer 2009;124:964–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wentzensen N, Schiffman M, Dunn ST et al. Multiple HPV genotype infections in cervical cancer progression in the Study to Understand Cervical Cancer Early Endpoints and Determinants (SUCCEED). Int J Cancer, 2009. 125:2151–2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wentzensen N, Walker JL, Gold MA et al. Multiple biopsies improve detection of cervical cancer precursors at colposcopy. J Clinical Oncol. 2015; 33:83–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Solomon D, Nayar R, ed. The Bethesda System for Reporting Cervical Cytology: Definitions, Criteria, and Explanatory Notes 2nd edition NY: Springer, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark SB, Dawson AE. Invasive squamous cell carcinoma in ThinPrep specimens. Diagnostic clues in cellular patterns. Diagn Cytopathol. 2002;26:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bentz JS, Rowe LR, Gopez EV, Marshall CJ. The unsatisfactory ThinPrep Pap test: missed opportunity for disease detection? Am J Clin Pathol. 2002; 117:457–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ozkan F, Ramzy I, Mody DR. Glandular lesions of the cervix on Thin-Layer Pap tests: validity of cytologic criteria used in identifying significant lesions. Acta Cytol. 2004; 48: 372–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee KR, Manna EA, St. John T: Atypical glandular cells: Accuracy of cytologic diagnosis. Diagn Cytopathol 1995;13: 202–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raab SS, Isacson C, Layfield LJ, Lenel JC, Slagel DD, Thomas PA. Atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance: cytologic criteria to separate clinically significant from benign lesions. Am J Clin Pathol, 1995;104: 574–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ronnett BM, Manos MM, Ransley JE, et al. Atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance (AGUS): cytopathologic features, histopathologic results, and Human papillomavirus DNA detection. Human Pathol. 1999;30: 816–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee KR, Darragh TM, Joste NE, Krane JF, Sherman ME, Hurley LB, Allred EM, Manos MM. Atypical glandular cells of undetermined significance (AGUS).Interobserver reproducibility in cervical smears and corresponding thin-layer preparations. Am J Clin Pathol 2002: 117:96–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wood MD, Horst JA, Bibbo M. Weeding atypical glandular look-alikes from the true atypical lesions in liquid-based pap tests: a review. Diagn Cytopathol 2007; 35:12–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krane JF, Granter SR, Trask CE, Hogan CL, Lee KR. Papanicolaou smear sensitivity for the detection of adenocarcinoma of the cervix: a study of 49 cases. Cancer Cytopathol. 2001;93:8–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nayar R, Wilbur D, ed. The Bethesda System for Reporting Cervical Cytology: Definitions, Criteria, and Explanatory Notes 3rd edition NY: Springer, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schoolland M, Allpress S, Sterrett GF. Adenocarcinoma of the cervix: sensitivity of diagnosis by cervical smear and cytologic patterns and pitfalls in 24 cases. Cancer Cytopathol. 2002;96: 5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruba S, Schoolland M, Allpress S, Sterrett G. Adenocarcinoma in situ of the uterine cervix: Screening and diagnostic errors in Papanicoulau smears. Cancer Cytopathol: 2004; 102: 280–2877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pak SC, Martens M, Bekkers R, Crandon AJ, Land R, Nicklin JL, Perrin LC, Obermair A et al. Pap smear screening history of women with squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the cervix. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;47: 504–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Sanjose S, Quint WGV, Alemany L et al. Human papillomavirus genotype attribution in invasive cervical cancer: a retrospective cross-sectional worldwide study. Lancet Oncol 2010; 11:1048–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pirog EC, Lloveras B, Molijn A et al. HPV prevalence and genotypes in different histological subtypes of cervical adenocarcinoma, a worldwide analysis of 760 cases. Mod Pathol. 2014; 27:1559–1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ronco G, Dillner J, Elfström KM, et al. : International HPV screening working group. Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: follow-up of four European randomised controlled trials. Lancet 2014; 383:524–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wright TC, Cox JT, Massad LS, Twiggs LB, Wilkinson EJ; ASCCP-Sponsored Consensus Conference. 2001 Consensus Guidelines for the management of women with cervical cytological abnormalities. JAMA. 2002; 287:2120–2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Massad LS, Einstein MH, Huh WK et al. 2012. ASCCP Consensus Guidelines Conference. 2012 updated consensus guidelines for the management of abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. Obstet Gynecol 2013; 121:829–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leeson SC, Alibegashvili T, Arbyn M et al. HPV testing and vaccination in Europe. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2014; 18: 61–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patadji S, Li Z, Pradhan D, Zhao C: Significance of high-risk HPV detection in women with atypical glandular cells on Pap testing: Analysis of 1867 cases from an academic institution. Cancer Cytopathol 2017; 125:205–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao C, Li Z, Austin RM. Cervical screening test results associated with 265 histopathologic diagnoses of cervical glandular neoplasia. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;140:47–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kinney W, Fetterman B, Cox JT, Lorey T, Flanagan T, Castle PE. Characteristics of 44 cervical cancers diagnosed following Pap-negative, high risk HPV-positive screening in routine clinical practice. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;121:309–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jeronimo J, Schiffman M. Colposcopy at a crossroads. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:349–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]